ABSTRACT

This paper explores community empowerment in tourism development in Nigeria through an analysis of the perceptions of key stakeholders. Community empowerment is essential to ensure local community members benefit from tourism development. The study uses a qualitative approach to evaluate the degree of local community participation and empowerment in tourism in South-West Nigeria. Findings suggest that when community members have a sense of their political agency, they feel empowered psychologically. Community empowerment was found to be experienced differently by different stakeholders within the communities—some were more positive than others. The variability of experience suggests the potential for some cross—institutional/project learning. Local Government Tourism Committees (LGTCs) can facilitate empowerment at the community level—should be supported, and their role cultivated, to address the dearth of meaningful community empowerment. This in turn will require Nigerian governance structures to be willing to devolve a degree of power and authority over decisions to these bodies and the communities they serve.

Introduction

Community participation can empower local people and help tourism development (Novelli, Citation2015; Okazaki, Citation2008). Through community participation, communities can make known their needs and aspirations regarding how they want tourism to develop (Bello et al., Citation2016; Timothy, Citation2007). However, this can be realised only when the system of tourism governance supports this. A thread in the literature on community participation proposes that participation in development must go further than involvement, towards empowerment (Bello et al., Citation2016; Boley & McGehee, Citation2014; Novelli, Citation2015; Scheyvens, Citation1999, Citation2002). Whereas participation can mean mere involvement—often passive, as outsiders may control the process, involving tokenism—empowerment is deeper and allows for active engagement of local communities, the latter having a degree of power to take the initiative themselves. The highest levels of Arnstein’s (Citation1969) Pretty’s (Citation1995) and Tosun’s (Citation1999) community participation frameworks in different ways indicate a progression from involvement to empowerment. Empowerment represents a higher level of community participation where residents have control over the planning process (Boley et al., Citation2017; Boley & McGehee, Citation2014).

Involving local communities in the planning process is also crucial to tourism development itself (Bramwell & Sharman, Citation2000; Scheyvens, Citation2002; Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2010; Tosun, Citation2000). This is especially the case if one takes a holistic conception of “development” to include the role of culture and democratic agency in quality of life (Marcus, Citation2003; Sen, Citation1999). Understanding how communities are empowered and the perception of other stakeholders is crucial.

Previous studies have investigated different perspectives on empowerment. For example, women’s empowerment (Abou-Shouk et al., Citation2021; Arroyo et al., Citation2019; Boley et al., Citation2017; Hutchings et al., Citation2020; Movono & Dahles, Citation2017); residents’ empowerment (Boley & McGehee, Citation2014; Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020; Maruyama et al., Citation2016; Strzelecka et al., Citation2017). Muganda et al. (Citation2013) explored the preconceived views of local communities in Barabarani Village, Arusha, Tanzania regarding their roles in tourism development. The study found that the local communities want to be involved in decision-making.

This research seeks to explore stakeholders’ perceptions of community empowerment in tourism development in Nigeria using a qualitative approach, drawing on stakeholder responses. The research also recognises that the government and other stakeholders in tourism development play a crucial role in facilitating and cultivating empowerment (Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Sofield, Citation2003), and hence understanding stakeholders’ perceptions becomes crucial. Further, Aghazamani and Hunt (Citation2017) highlight the need for research that considers all stakeholders involved in tourism empowerment discussions. This paper, therefore, examines empowerment processes in tourism development in four local communities in Nigeria using three key dimensions of empowerment—political, socio-economic and psychological—drawn from Scheyvens’ framework (Citation1999, Citation2002). It analyses the voices and perceptions of stakeholders, including the local community members themselves, regarding how they participate and the extent to which they feel empowered in tourism development.

Community participation takes place in the context of wider political structures and culture. In particular, a “local community” in Nigeria exists within states, regions and the federal tiers of government. The Local Government Tourism Committees (LGTC) are the third level of governance in the existing tourism institutional arrangement, and they are subject to the control of the State Tourism Boards (NTDMP, Citation2006, pp. 171–172). Hence, it is at the level of the LGTC that empowerment can take place, as that is the focus of governance at the local level. Similar arrangements are typical of many other African countries. The paper focuses on attitudes to participation as experienced by stakeholders, at the local level. However, the issues identified are issues for governance and government in Nigeria as a whole.

Literature review

The literature review first looks at community participation, and then the research’s key concept, empowerment. Whilst sometimes used almost interchangeably, we note that the former tends to emphasise the formal process of involving members of a defined, local community in tourism development, whereas the latter focuses on how communities experience participation and its impacts, both empirically (e.g. jobs) and perceptually (e.g. community pride). Aghazamani and Hunt’s (Citation2017) thematic analysis of peer-reviewed articles provided a definition of empowerment in the context of tourism. This is used here to ensure consistency in both the application and understanding of the term. Their research defined empowerment as “a multidimensional, context-dependent, and dynamic process that provides humans, individually or collectively, with greater agency, freedom, and capacity to improve their quality of life as a function of engagement with the phenomenon of tourism” (p. 333).

The primary research focuses on stakeholders’ own experiences of participation, emphasising empowerment as described above. However, these responses inevitably make reference to community participation, and it is here that policy can shape a culture of good governance and hence cultivate empowerment. Note that our conclusion emphasises the need for policymakers to cultivate the role of the LGTCs precisely to address the lack of empowerment so evident in the findings.

Community participation in tourism planning

Community participation is considered to be a situation whereby the community members who live in a particular area or locality directly participate in tourism decision-making and as a result, benefit from such interaction. Research in tourism planning has long highlighted the need to involve the local community in the planning process (Murphy, Citation1985; Scheyvens, Citation1999; Tosun, Citation1999, Citation2000). A seminal work on community participation in tourism planning by Murphy (Citation1985) popularised local community participation in tourism development. He argued that inadequate consultation with the people at the local community level has undoubtedly contributed to unsustainable tourism planning. Often, it is the local people who are left out of decision-making relating to tourism planning (Mowforth & Munt, Citation2016).

From the review of the literature on participation in development practice, some scholars such as Arnstein (Citation1969), Pretty (Citation1995) and (Tosun, Citation1999, Citation2006) provide important typologies and analyses of participation. Here, some forms of participation are passive rather than active with regard to control over development, and therefore may neglect potential benefits arising from a more active approach (Tosun, Citation2006). An early work by Arnstein (Citation1969) classifies citizen participation into three categories and eight sub-categories using a ladder to illustrate and clarify the term. At the lower end is non-participation, which is often used as a substitution for real participation. It involves a degree of tokenism where citizens can state their views, but without the power to ensure those views are used in decision-making. This is still prevalent in developing countries where participation is formally used to comply with international standards whilst rarely put into practice on the ground (Timothy, Citation2007; Timothy & Tosun, Citation2003; Tosun, Citation2000, Citation2006). At the higher end of the ladder is a degree of citizen control, where local communities are empowered and are actively involved in decision-making. In a later publication, Pretty (Citation1995) categorises the levels of participation into seven scales. These include manipulative or passive, consultation, contributing resources, functional, interactive, and self-mobilisation. While the first five modes of participation are regarded as commonplace by Butcher (Citation2007), it is at the two final levels of participation—“interactive” and involving “self-mobilisation”—that the local people can participate actively in decision-making processes. This is indicative of empowerment.

Adeyemo and Bada (Citation2016) conclude that tourism decision-making in Nigeria is decidedly top-down, and the form of participation often experienced by local communities is passive. Other authors argue that tourism planning in Africa suffers as a result, and that local community involvement should therefore be prioritised (Adebayo & Butcher, Citation2021; Dei, Citation2000; Muganda et al., Citation2013; Telfer & Sharpley, Citation2008), not least because it is a component of sustainable tourism development (Scheyvens, Citation2002; Strzelecka & Wicks, Citation2010; Tosun, Citation2000). It is also claimed that local community involvement is fundamental to creating an understanding between the government and the community on how to use local resources sustainably and appropriately (Bello et al., Citation2016; Jamal & Stronza, Citation2009). However, some research suggests that tourism is being developed in many communities without the participation of residents (Reid et al., Citation2000; Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2014). Indeed Adeyemo and Bada (Citation2016), and Muganda et al. (Citation2013), found that local community members want to be actively involved in decisions on tourism development so that their needs and concerns can be incorporated into such plans. This can enable communities to protect their values, norms, and interests, and also to increase equity and transparency regardless of their level of illiteracy. The importance of meaningful involvement from residents who may lack formal literacy or education has long been emphasised in development thinking, principally by Chambers (Citation1983), on the basis of equity (Burgos & Mertens, Citation2017; Ezeuduji, Citation2015).

The phrase local participation is often repeated and for some has become a meaningless mantra. For Butcher (Citation2010, p. 204), “what the mantra of local participation does is to portray political agency as a local phenomenon affecting local people, premised upon their local environment”. Here, Butcher claims that rather than being empowering, local participation can limit community agency spatially and politically to what is deemed local. Nonetheless, Scheyvens (Citation2002) neo-populist view advocates that the voices of the people who are most affected by tourism should be heard and that local communities ought to be central to any tourism planning and management. The neo-populist idea on community participation stresses community control, i.e. community agency is seen to be at the forefront of development formulation, and not “big” government or “big” business (Butcher, Citation2007). Community agency entails building relationships that enhance the capacity of local people to act for themselves (Matarrita-Cascante et al., Citation2010). George et al. (Citation2009) highlight that the local people who are close to where tourism development takes place should be part of tourism policy formulation and development since it affects their lives, and that such policies should not be made from afar. Authors (Adu-ampong, Citation2017; Kimbu & Ngoasong, Citation2013; Tiberghien, Citation2019) stress the importance of decision-making processes in tourism that integrates stakeholders across different levels of governance. It is essential that the local people be consulted from the point of vision creation and not by merely asking them to react to policy drafts that they were not involved in planning. This Tosun (Citation1999) refers to as non-participation, representing a higher degree of tokenism and potentially manipulation.

Community participation allows for cooperation and collaboration and encourages principles such as efficiency, trust, equity, integration, harmony, balance, and ecological and cultural integrity (Bello et al., Citation2016; Garrod, Citation2003; Tosun & Timothy, Citation2003). However, ensuring that all stakeholders’ views are heeded to and given equal consideration is difficult since the perspectives and the primary concern of the powerful groups often prevails (Bramwell, Citation2004; Ezeuduji, Citation2015). This is primarily a question of governance and political culture, and this has long been a fraught issue in Nigeria. Yet it is one that a sector such as tourism, involving local cultural and natural resources directly, should prioritise.

The recognition of participatory approaches to planning is also linked to getting local knowledge and perspective in tourism development. Local community involvement is important not only as a democratic norm, but also instrumentally, as they alone possess the local knowledge needed to support tourism development in any given destination (Bramwell, Citation2004; Garrod, Citation2003; Sebele, Citation2010; Sutawa, Citation2012; Tosun & Jenkins, Citation1998). Through collaborative processes, valuable information about local people’s practical awareness and local knowledge could be drawn from in order to align tourism development with local community priorities and aspirations (Bramwell, Citation2004; Sutawa, Citation2012).

Empowerment through community participation

Empowerment, whilst a general term open to much interpretation, rejects the unbalanced top-down decision-making and planning approach and recommends the bottom-up approaches where the poor are active participants in development (Calvès, Citation2009). Empowered communities have a meaningful degree of control over tourism development, rather than the government and the private sector alone having this (Butcher, Citation2007; Mikkelsen, Citation2005; Sofield, Citation2003; Tosun, Citation2005; Willis, Citation2011). In an important sense, if participation is the form taken by community involvement, empowerment is its content, the expressed agency of the community.

Participation can take the form of allowing locals to benefit from tourism economically (Bello et al., Citation2016; Dieke, Citation2000; Timothy, Citation1999; Timothy & Tosun, Citation2003), socially (Timothy & Tosun, Citation2003), building awareness and educating residents (Dieke, Citation2000; Timothy, Citation1999, Citation2007; Timothy & Tosun, Citation2003), engaging women to play a role in the tourism sector and allowing the masses access to entrepreneurial tourism opportunities (Dieke, Citation2000). A goal of community participation in tourism planning is to empower the people so that they can effectively participate in both decision-making and the sharing of tourism benefits (Bello et al., Citation2016). Tosun (Citation2005) points out that for a participatory development strategy to be sustained, the government needs to pro-actively encourage empowerment.

In discussions of empowerment, the degree to which the local communities should be self-reliant for it to be said that it has occurred is uncertain. Almost inevitably there will be involvement of investors, businesses or government beyond the community level (Sofield, Citation2003). Because of the lack of capacity for the “poor” to help themselves, even when local communities are empowered, they will still need some assistance from the government regarding skills and resources so that the project does not fail (Sofield, Citation2003). Also, given the prevailing cultural, political and socio-economic conditions in developing countries (Ezeuduji, Citation2015; Sène-Harper & Séye, Citation2019; Tosun, Citation2005) the government's role as an initiator is important in community participation and in developing tourism projects (Novelli, Citation2015; Tosun, Citation2005). This is because, the government sets the regulations or ground rules within which tourism operates (Ezeuduji, Citation2015; Scheyvens, Citation2011). Notwithstanding these qualifications, community empowerment in tourism occurs when local stakeholders have a substantial degree of control over, or lead, tourism development projects linked to their heritage (Butler & Hinch, Citation2007; Novelli, Citation2015). Dolezal and Novelli (Citation2020) argue that some common issues in community participation in less developed countries include lack of skills, knowledge, favourable public policy, difficulty in defining participation due to the existing socio-cultural and political structures that do not easily align with democratic ideas.

On the latter point Adeyemo and Bada (Citation2016) and Telfer and Sharpley (Citation2008), argue that tourism planning and development generally occur through a top-down approach in developing countries, including Nigeria. Community-based tourism does not always reflect bottom-up development (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020). Specifically in the context of sub-Saharan Africa there are socio-cultural and political characteristics which shape governance processes, including for tourism (Ezeuduji, Citation2015; Jenkins, Citation2015; Tosun, Citation2005). Yet many of the frameworks for assessing community empowerment have been developed and refined in the developed countries. These may not be easily adaptable to the context of the developing countries.

Scheyvens (Citation1999) model remains a significant contribution to the empowerment discussion in tourism development. The framework’s four empowerment dimensions are: political; economic; social, and; psychological. Though this framework was developed for ecotourism, it can be applied to other forms of tourism development and will be drawn upon in the analysis section. This study looks at Scheyvens’ “economic” and “social” forms of empowerment as socio-economic empowerment in addition to political and psychological empowerment.

For Scheyvens, “political empowerment” is concerned with the community management of the process of tourism development (Scheyvens, Citation2003). It happens when the voices and concerns of the community guide the development of tourism projects from the feasibility phase to its implementation (Scheyvens, Citation1999). The local tourism committee and village development committee—commonly in existence in Nigeria—could be a pathway for such local interests to be represented (Scheyvens, Citation2003). The destination community needs to have a forum where they can participate in decision-making or raise concerns over tourism development as it affects them most (Dei, Citation2000; Timothy, Citation2007). However, arguably true empowerment happens when they initiate tourism development programmes (Timothy, Citation2007, Citation1999), and when the marginalised interest groups such as the poor and young people can contribute meaningfully to the planning processes (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020; Garrod, Citation2003). For example, in Tanzania, political structures were introduced both within and between the communities to manage tourism development projects and enhance empowerment in this way (van der Duim et al., Citation2006).

“Socio-economic empowerment” is evident through formal or informal employment (Scheyvens, Citation1999), and business opportunities in the local community through tourism (Dei, Citation2000; Marina Novelli & Gebhardt, Citation2007; Scheyvens, Citation1999; Scheyvens, Citation2003). This form of empowerment holds that economic benefits should be regular, be a reliable source of income (Scheyvens, Citation1999), empower women and the youth (Scheyvens, Citation1999), and should spread evenly within the community (Scheyvens, Citation1999; Timothy, Citation1999). This suggests that socio-economic empowerment is evident when the entire community benefits from tourism development and not just a few individuals. Also, this form of empowerment is evident when profits from tourism activities are utilised for developing social projects, such as health clinics, water supply facilities or in the local community (Scheyvens, Citation1999). This research combined economic and social empowerment as they often overlap in the way they are experienced at the local level in Nigeria.

According to Scheyvens (Citation1999), “psychological empowerment” occurs when the local community believe in their abilities, are hopeful about the future of tourism development, exhibit pride in their local traditions, culture and are self-reliant. Psychological empowerment is also associated with the confidence of the community members to participate effectively and equitably in tourism planning and development (Scheyvens, Citation1999). Further, when aspects of local community traditions are preserved, this can have positive implications for well-being and self-esteem (Boley & McGehee, Citation2014; Scheyvens, Citation2003). This form of empowerment can be in evidence when, for example, communities are encouraged to develop crafting skills (Timothy, Citation2007).

Psychological empowerment indicates positive ability within a community to take collective action to create social and political change (Christens, Citation2012; Timothy, Citation2007). Conversely, Scheyvens (Citation1999, Citation2002) argues that when communities experience the opposite in any of these dimensions, they are disempowered in tourism development. They are effectively alienated from tourism developments occurring in their midst.

Research methodology

For Tribe (Citation2001) the advantage of interpretivism in tourism research is that it enables the researcher to understand the perspective of the different actors, which in this case are the “voices” of the different stakeholders. Hence the research adopts a qualitative approach, using semi-structured interviews with a sample of stakeholders. The interviews were conducted in the South-Western part of Nigeria, between August and October 2017. Each interview lasted between twenty-five minutes and 2 h. In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer starts typically with some set questions across all interviews, but allows for improvisation as new questions may emerge during the interview conversations (Myers, Citation2013). This allows the interviewee to be open and say all that they know or consider essential on a topic (Myers, Citation2013).

The twenty-three stakeholders interviewed comprised local community members, academics, and public and private sector agencies. These stakeholder groups are central to tourism development in South-West Nigeria. The interviewees were selected through purposive and snowballing sampling (Myers, Citation2013), based on their position or roles and the knowledge or experience that they have about tourism development in Nigeria (see ). The researcher started the data gathering process with purposive sampling and then built on this by asking the stakeholders to recommend other key informants within their network. For the community interviews, the researcher identified four local communities in South-West Nigeria where tourism development projects are taking place and approached them directly because of their relevance to the research.

Table 1. Stakeholders surveyed in the Nigerian tourism sector.

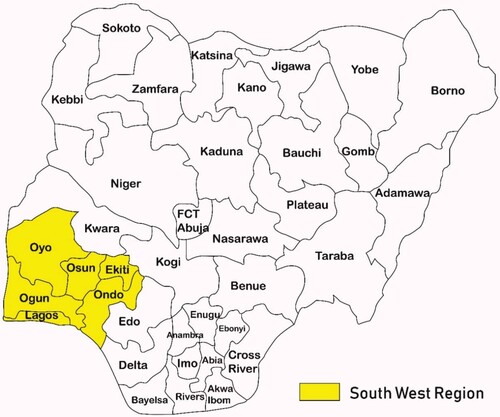

South-West Nigeria is one of the six geopolitical zones in the country. The region constitutes six states: Lagos, Oyo, Ogun, Osun, Ondo and Ekiti states (known as the homeland of the “Yoruba” people). South-West Nigeria is an area of about 191,843 square kilometres and lies between longitude 30° and 7°E and latitude 4° and 9°N (Oni & Odekunle, Citation2016). The Yoruba region is one of three dominant ethnic groups in Nigeria, along with the Hausas and Igbos that dominate the northern and eastern regions respectively. The Yoruba people can boost rich indigenous culture including, festivals, shrines, historical sites, streams, mountains, national parks and game reserves that are used for tourism development. See for the Map of South-West region of Nigeria. Four of the six South-West states—Osun, Ekiti Ogun, and Ondo—were selected for this research. Subsequently one community from within each state was chosen: Erin Ijesha, Ikogosi, Olumo and Idanre (see ). All the community representatives interviewed were male, which itself shows an element of gender imbalance in terms of women’s empowerment in tourism development. All the tourism projects and attractions in those states are located in rural communities, in keeping with the research focus.

Table 2. Summary of the four communities studied.

The twenty-three face-to-face interviews were tape-recorded with participants’ permission, and transcribed verbatim. This data was used for analysis in addition to the fieldwork notes. The dataset was input into NVIVO 11.3, a qualitative data analysis software, to help organise it for easy coding, sorting, synthesising and theorising as suggested by Saldana (Citation2016). NVIVO was used to organise and store data to aid data analysis in Nigeria. identifying phrases, sentences and groups of sentences—in the context of a more general narrative elucidated by the participant—against a number of themes. These themes comprise “political”, “socio-economic” and “psychological” aspects of empowerment, as per Scheyvens (Citation1999, Citation2002) categorisation. Exemplary quotes were chosen purposively from the database on the basis of their capacity to represent sentiments exhibited more broadly, and across a range of stakeholders.

Findings and discussion

This next section presents the findings in three subsections corresponding to Scheyvens’ categorisation of empowerment outlined in the literature review: political; socio-economic; and psychological empowerment. These are discussed with reference to Nigeria.

Political empowerment

Political empowerment occurs when local community members are enabled to determine their own development goals and concerns for tourism development. In the context of Nigeria, whilst the government consults with the Kings and Chiefs of the communities to tell them their plans on tourism development projects, they do not necessarily involve them in the decision making process. An instance which one participant described is that:

[…] In most cases, that decision would have been taken without really carrying the local communities inhabiting such places along […]. Government would have decided before now meeting the local people to tell them that this is what we want to do, these are the plans we have for you and so on. (A2, Academic)

These quotes revealed the perception that it is only pre-determined decisions that the government take to the local communities, to seek their permission. This view, therefore, echoes the point made by (Tosun, Citation1999) that in developing countries tourism development is often driven by the central government's priorities and not by the needs of the local people, who are left with no choice but to live with projects determined for them. This form of participation experienced is top-down and passive, where the community leaders only endorse the decisions taken by external bodies and participate in its implementation but not necessarily in the sharing of benefits (Tosun, Citation1999; Yang et al., Citation2008). Real community participation and empowerment encourages participatory decision-making that is active and allows the community to have power rather than being characterised by tokenism or manipulation.

One interviewee raised an instance where the local tourism committee existed but was then eliminated when another government came into power. This quote from participant C4b reveals that such committees do not exist within the local community set up:

I remember once they set up a committee because of my insistence that we have to have a committee at a local level. The local government came for a funfair to set up the committee, but it died a natural death because of lack of continuity. […] Never, no empowerment! Because if the government has accepted the idea of the committee […] the empowerment will come from training local tourist guides, employing people and training them to standardise the kind of tourism service within the community. But no empowerment of sort. (C4b, Community)

With regard to another community representative in Abeokuta, this participant stated that the government invited them to make contributions to decision-making, but that they are limited as they can only contribute along the line of the area that they want their input on: whenever they call us, we can only contribute to whatever they want our contributions on (C3, Community). Despite this community representative believing they at least have a voice in some aspects of decision-making, this is very limited political empowerment as they cannot influence initiatives beyond those determined by the government (Timothy, Citation2007).

Another community representative makes a slightly different point along the same lines: that the government consults when problematic issues arise in the development process: […] that’s part of what brought me in, for example if the resort is facing any problem they contact us, or any indigenous decision that has to do with traditional they contact the community. (C2, Community)

As indicated in the extract, the community is being called upon by the government only when the development of the tourism resource is confronted with a problem, either caused by the community or other issues relating to tradition, and the government feels they are the only people who can help resolve it. This places the representatives of the community in an invidious position, being called upon to smooth over problems possibly arising from the lack of participation in the first place.

Conversely, two of the communities, Ikogosi and Abeokuta, have experienced some forms of political empowerment to influence decisions in tourism development. For Ikogosi this is as a result of having members of the community as management staff within the attraction. Also, for Abeokuta they have experienced some form of political empowerment through the Community Development Association (CDA). These sentiments are expressed in these quotes:

Some of us are in the management level, so whatever that has to do with the members] were very furious they came [the government, and] agreed, so until it was changed so some of them [the community members] were later committed to the management level of the resort […]. (C2, Community)

They will call them to the meeting and tell them whatever necessary thing they want to do over there. They will make their own contributions and by the grace of Almighty Allah our governments have always attended to and make use of our contributions. (C3, Community)

So, they are just like the image builder of the state, they are the ones who promote the state through those attractions, that is why I said it is something that we cannot do without, we cannot push them aside and say we want to promote tourism, it’s not possible. They must be actively involved for you to bring out the best in tourism. (S3, State)

Socio-economic empowerment

Socio-economic empowerment or benefit is evident through formal or informal employment or business opportunities in the local community or other development projects as a result of tourism development (Scheyvens, Citation1999). Tourism development is based on resources in the local communities and such projects may limit their access to resources which they would ordinarily have access to (Scheyvens, Citation2003). Where this occurs, and the local people do not get significant benefit through such development, they can be said to have been disempowered (Scheyvens, Citation2003). Tourism resources in Nigeria are located in local communities (Mustapha, Citation2001), and often tourism development limits the access of local communities to their resources. In the Ikogosi community for example, as a result of tourism development, the community residents have limited access to the attraction site.

The socio-economic empowerment of local communities that host tourism resources is vital for a developing nation like Nigeria. The community representatives interviewed indicated a high level of dissatisfaction concerning the economic empowerment experienced by their communities. Such sentiment found expression in extracts such as these from the community representatives interviewed: Nothing! Only two or three people they employed, some of our youths, as security guards, ticket officers and gate controllers. (C1, Community). Another community member said:

There is no empowerment except those people who are selling pure water [commercially packaged water in plastic bags] and the hawkers, who are hawking biscuits at the front of the hill. We don’t even have craft people selling there. For example, if everything is in place where we want to develop the way we thought of it, it should be a place where we have craft men selling their wears and clothes batiks and so on but there is nothing like that. Because the place was made that way; it was not made in a way that people should be able to sell their things. There is nothing there really for the community so far. (C4b, Community)

It is worthy of mention that in the case of participant C4b’s Idanre community, where they had an idea of how their community members could be empowered, they did not get the necessary support from the government. As a result, their idea could not be implemented. Mowforth and Munt (Citation2016) explain that as vital as it is for the local community to have ideas for tourism development, it is equally imperative that the community gets the assistance of the national government concerning acquiring skills and resources to coordinate their plans.

One participant questioned the economic empowerment experienced by local communities as insufficient. She expressed that view that it should be deeper: Some believe getting some host community jobs is community participation […] and they won’t even get them jobs that are of importance, probably maybe a porter, which they think is doing them a favour. (F1, Federal).

This quote revealed a sort of patronage epitomised by the phrase “doing them a favour”, where the government give menial jobs that yield little money to the local communities as a reward for allowing the government to develop their resources for tourism. Indeed, (Mbaiwa, Citation2005) has criticised the practice of employing local communities in low-level jobs to this end and Butcher (Citation2007) has pointed to the instrumental character of such patronage as simply to gain compliance and no more.

Benefits from local cultural festivals should be one clear avenue whereby local people can be empowered economically through a celebration of their culture. Notwithstanding wider debates about the staging of culture for financial benefit, participants expressed disappointment. One academic participant commenting on the Osun-Osogbo festival, stated:

OK, you can imagine the festival that is just concluded in Osogbo, people from Abuja, from Lagos, from Kaduna came, and you know they spent their money. These local people, what did they do, they were just looking like this and nothing gets to them. (A3, Academic)

Psychological empowerment

The psychological aspect of empowerment has become a considerable area of debate for over two decades (Christens, Citation2012). For example, local community wellbeing, self-esteem, self-confidence and happiness are all now a routine part of regular discussions of development (Christens, Citation2012). Hence, psychological empowerment should be a part of discussions of tourism development in local communities.

According to Scheyvens (Citation2003), psychological empowerment occurs communities receive outside recognition for the unique cultural resources and values that they have in their community; thereby enhancing their self-esteem. The importance of recognition of identity has been emphasised by Sociologist Axel Honneth (Citation2001). He considers

struggles for recognition in which the dimension of esteem is central as attempts to end social patterns of denigration in order to make possible new forms of distinctive identity. […] Esteem is accorded on the basis of individual's contribution to a shared project. (xvii)

Psychological empowerment happens when the local community members believe in their own agency, and are hopeful about the future of tourism development (Scheyvens, Citation1999). Community agency entails building relationships that enhance the capacity of local people to act for themselves (Matarrita-Cascante et al., Citation2010). This form of empowerment could also translate into other tangible forms of empowerment, or lead them to take actions such as seeking education or training in tourism and seeing outcomes in the form of earnings from tourism (Scheyvens, Citation1999, Citation2002). When the community members in localities where tourism development takes place have a feeling of disillusionment, dissatisfaction and confusion, they are not psychologically empowered (Scheyvens, Citation2003). All three are consistent features across the interviews conducted with non-government stakeholders. Exemplary quotes of this form of empowerment are discussed below.

In one community, the representative expressed a general unhappiness with development amongst community members: We feel bad! Because they don’t involve us. If we were involved, it would have been developed (C1, Community). The case of the Erin-Ijesha community, Osun State, presented excellent evidence and was drawn upon by other stakeholders.

In agreement, an academic stakeholder commenting on the Erin-Ijesha community, stated that in her experience, the community members feel uninterested and alienated from tourism development in their community because they do not think it is beneficial to them:

the first point of annoyance or grievance that people have is that this thing has not contributed anything to them, they've not benefited anything from it. So, once they don’t see it as a positive factor or force in their life, they don’t want to be associated with it. (A5, Academic)

In another community, Idanre, the government is entirely in charge, and the community is not involved at all. Again, community members feel alienated and unhappy. Participant C4b expressed this view:

Of course they [the government] were doing it the way they wanted. And the society was totally cut off from the processes of [tourism] development because they made it totally a government affair, and they made the whole thing very difficult, and the people are not very happy about it. (C4b, Community)

Well, what I feel is on the positive side, because probably as I told you the last time you came, the community people are familiar with nearly all the currencies of the world because people come from all over the world and in terms of Ghana Cedis, Gambian Dalasi, Dollars, Pounds […] among the neighbouring town [my community] is the most social in terms of […] having inflows of people. It is the most visited town in [our] State. (C2, Community)

As revealed by the participants, a significant source of grievance from the community is that they do not benefit from tourism development. This affirms and answers a critical question that the researcher’s previous work identified on the reason why local communities do not support tourism development in their communities (Adebayo, Citation2017). The discussion above suggests that in most of the communities studied, they lacked psychological empowerment, while one community experienced a positive psychological empowerment.

The research identified that there is a shared understanding of the need for community members to participate in tourism development in Nigeria. However, this participation in most cases has not led to empowerment of the communities investigated. There are usually challenges of implementing community-based tourism principles in communities dominated by hierarchical structures based on different understandings of democracy (Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020). While some communities have experienced some forms of empowerment, the case is different for some other communities as illustrated in .

Table 3. Summary of indications of empowerment in the planning process.

Communities experienced different forms of participation and empowerment. While communities 2 and 3 seem to be enjoying some forms of participation and empowerment through tourism development projects. There appears to be very little effort being made in initiating such participation and empowerment in communities 1 and 4. Interviewees from the private sector and some government officials themselves expressed the view that there is little or no empowerment in tourism development in the local communities, this is because the Local Government Tourism Committees are not adequately supported by higher tiers of government to fully function. The current practice limited empowerment of the communities in decision-making was questioned and illustrated by one community representative, C4, who feels that what is happening in tourism development now does not paint an ideal picture:

[…] I cannot just go to your house now and start to decide for you. I have to involve you if there is something to be done. You cannot just come to my house and tell me this is what I want to do in your house, except you tell me first, [then] the thing will move [work]. (C4, Community).

Conclusions

This paper has explored stakeholder perceptions of community empowerment in tourism development in Nigeria, using the three key dimensions of political, socio-economic and psychological empowerment framework. One of the main reasons for analysing community participation and the empowerment of communities is that tourism development should promote local community development. This can be possible when the local communities participate in the tourism planning and development processes that allow them to say what their aspirations and needs are concerning development projects. The concept of empowerment is essential to examine the extent to which often marginalised local communities’ benefit from tourism. It is through community participation and empowerment that local communities can realise benefits from tourism resources in their community.

The most striking finding is that it is that local people are being left out of the decision making relating to tourism planning. This is far from unusual, but nonetheless important. Developing a process that allows the local community to participate in every aspect of tourism planning would be a step towards creating a mechanism to mitigate negative impacts and to develop an approach to tourism that can satisfy at least some of the needs of the community. The findings revealed that communities that host attraction sites are being excluded from key decision-making processes.

The research indicates that there is a desire on the part of many stakeholders to be involved and to be empowered. The LGTC institutional structure at the local level that should enable their opinions or voices to influence tourism development has not been established in the communities, irrespective of formal, written policy. Relatedly, this aspiration on the part of those who possess the local knowledge can prospectively help tourists’ experience, the tourism product and tourism development, which makes it imperative for them to be involved in such processes.

Further the different local communities had different experiences of community empowerment/participation to influence decisions in tourism development. For example, for one community, this is as a result of having members of the community as management staff within the attraction. For another community, they were involved and able to contribute through the Community Development Association (CDA). In some communities, participation was limited to endorsing decisions made by outsiders, whereas others had a more positive, if limited, experience of empowerment. This suggests the possibility of some cross-institutional learning and sharing of “best practice”. These are governance questions beyond tourism per se, but nonetheless ones in which tourism can play a role in developing a more progressive governance.

Having a sense of agency to determine goals for tourism development politically, empowers communities psychologically. Psychological empowerment can aid communities to take collective action to create social and political change (Christens, Citation2012; Timothy, Citation2007). The neo-populist idea of community participation stresses community control, i.e. community agency is seen to be at the forefront of development formulation, and not “big” government “big” business (Butcher, Citation2007). Local communities need to be adequately empowered through all the dimensions to enhance sustainable tourism development. Hence, the LGTC need to be strengthened and given the capacity to function in practice. The Nigeria Tourism Development Plan has made formal provision for this; however, it is yet to be implemented to the latter in practice. Additionally, the federal and the state government level need to coordinate the effort to involve the community members in the tourism development planning process. The research findings suggest that there is a desire to improve the situation amongst a range of stakeholders. Equally, it suggests that although formal mechanisms for community participation exists, principally in the form of the LGTCs, without a willingness to devolve authority, cultivate trust and empower local stakeholders, that desire remains frustrated.

Psychological empowerment was difficult to measure, however, participants comments on feelings whether positive or negative was used as a benchmark for this form of empowerment. Future research can use tools in psychology to assess levels of empowerment. In addition, there is a need for more research on women’s empowerment in tourism development in Nigeria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abou-Shouk, M. A., Mannaa, M. T., & Elbaz, A. M. (2021). Women’s empowerment and tourism development: A cross-country study. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100782

- Adebayo, A. D. (2017). Sustainable tourism and cultural landscape management: The case of Idanre hill, ondo state. Nigeria. Tourism Today, 16, 43–55.

- Adebayo, A. D., & Butcher, J. (2021). Constraints and drivers of community participation and empowerment in tourism planning and development in Nigeria. Tourism Review International, 25(2-3), 209–227.

- Adeyemo, A., & Bada, A. O. (2016). Assessing local community participation in tourism planning and development in Erin-Ijesha waterfall Osun state, Nigeria. International Journal of Social Studies, 2(12), 52–66.

- Adu-ampong, E. A. (2017). Divided we stand: Institutional collaboration in tourism planning and development in the central region of Ghana. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.915795

- Aghazamani, Y., & Hunt, C. A. (2017). Empowerment in tourism: A review of peer- reviewed literature. Tourism Review International, 21(4), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427217X15094520591321

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Arroyo, C. G., Barbieri, C., Sotomayor, S., & Knollenberg, W. (2019). Cultivating women’s empowerment through agritourism: Evidence from andean communities. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113058

- Bello, F. G., Carr, N., & Lovelock, B. (2016). Community participation framework for protected area-based tourism planning. Tourism Planning and Development, 13(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1136838

- Boley, B. B., Ayscue, E., Maruyama, N., & Woosnam, K. M. (2017). Gender and empowerment: Assessing discrepancies using the resident empowerment through tourism scale. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177065

- Boley, B. B., & McGehee, N. G. (2014). Measuring empowerment: Developing and validating the resident empowerment through tourism scale (RETS). Tourism Management, 45, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.04.003

- Bramwell, B. (2004). Partnerships, participation, and social science research in tourism planning. In A. A. Lew, C. M. Hall, & A. Williams (Eds.), A companion to tourism (pp. 541–554). Blackwell Publishing.

- Bramwell, B., & Sharman, A. (2000). Approaches to sustainable tourism planning and community participation. The case of the Hope valley. In G. Richards, & D. Hall (Eds.), The community a sustainable concept in tourism (pp. 17–35)..

- Burgos, A., & Mertens, F. (2017). Participatory management of community-based tourism: A network perspective. Community Development, 48(4), 546–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2017.1344996

- Butcher, J. (2007). Ecotourism and community participation ecotourism, NGOs and development. Routledge.

- Butcher, J. (2010). The mantra of “community participation” in context. Tourism Recreation Research, 35(2), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2010.11081634

- Butler, R., & Hinch, T. (2007). Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080553962

- Calvès, A. (2009). Empowerment: The history of a key concept in contemporary development discourse. Revue Tiers Monde, 200(4), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.3917/rtm.200.0735

- Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. Routledge.

- Choi, H. C., & Murray, I. (2010). Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903524852

- Christens, B. D. (2012). Targeting empowerment in community development: A community psychology approach to enhancing local power and well-being. Community Development Journal, 47(4), 538–554. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss031

- Dei, L. A. (2000). Community participation in tourism in Africa. In P. U. C. Dieke (Ed.), The political economy of tourism development in Africa (pp. 285–298). Cognizant Communication Corporation.

- Dieke, P. U. C. (2000). Tourism and Africa’s long term development dynamic. In P. U. C. Dieke (Ed.), The political economy of tourism development in Africa (pp. 301–312). Cognizant Communication Corporation.

- Dolezal, C., & Novelli, M. (2020). Power in community-based tourism: Empowerment and partnership in Bali. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(10), 2352–2370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1838527

- Ezeuduji, I. O. (2015). Building capabilities for sub-saharan Africa’s rural tourism services performance. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 21(sup-2), 68–75.

- Garrod, B. (2003). Local participation in the planning and management of ecotourism: A revised model approach. Journal of Ecotourism, 2(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040308668132

- George, W., Mair, H., & Reid, D. G. (2009). Rural tourism development: Localism and cultural change. Channel View Publication.

- Honneth, A. (2001). The struggle for recognition. The MIT Press.

- Hutchings, K., Moyle, C. l., Chai, A., Garofano, N., & Moore, S. (2020). Segregation of women in tourism employment in the APEC region. Tourism Management Perspectives, 34, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100655

- Jamal, T., & Stronza, A. (2009). Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802495741

- Jenkins, C. L. (2015). Tourism policy and planning for developing countries: Some critical issues. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1045363

- Kimbu, A. N., & Ngoasong, M. Z. (2013). Centralised decentralisation of tourism development: A network perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 40(1), 235–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.09.005

- Marcus, P. (2003). Rethinking development geographies. Routledge.

- Maruyama, N. U., Woosnam, K. M., & Boley, B. B. (2016). Comparing levels of resident empowerment among two culturally diverse resident populations in Oizumi, Gunma, Japan. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(10), 1442–1460. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1122015

- Matarrita-Cascante, D., Brennan, M. A., & Luloff, A. E. (2010). Community agency and sustainable tourism development: The case of La Fortuna, Costa Rica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(6), 735–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653526

- Mbaiwa, J. E. (2005). Enclave tourism and its socio-economic impacts in the Okavango delta, Botswana. Tourism Management, 26(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.11.005

- Mikkelsen, B. (2005). Methods for development work and research a new guide for practitioners (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Movono, A., & Dahles, H. (2017). Female empowerment and tourism: A focus on businesses in a Fijian village. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(6), 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1308397

- Mowforth, M., & Munt, I. (2016). Tourism and sustainability: Development, globalisation and new tourism in the third world (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Muganda, M., Sirima, A., & Ezra, P. M.. (2013). The role of local communities in tourism development: Grassroots perspectives from Tanzania. Journal of Human Ecology, 41(1), 53–66.

- Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. Methuen.

- Mustapha, A. (2001). The survival ethics and the development of tourism in Nigeria. In K. B. Ghimire (Ed.), The native tourists mass tourism within developing countries (pp. 172–197). Earthscan Publications limited.

- Myers, M. D. (2013). Qualitative research in business management (2nd ed). Sage.

- Novelli, M. (2015). Tourism and development in sub-saharan Africa: Current issues and local realities. Routledge.

- Novelli, M., & Gebhardt, K. (2007). Community based tourism In Namibia: “Reality show” or “window dressing”? Current Issues in Tourism, 10(5), 443–479. https://doi.org/10.2167/cit332.0

- NTDMP. (2006). Nigeria tourism development master plan institutional capacity strengthening to the tourism sector in Nigeria (Issue January).

- Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

- Oni, F. G. O., & Odekunle, T. O. (2016). An assessment of climate change impacts on maize (Zea Mays) yield in south-western Nigeria. International Journal of Applied and Natural Sciences, 5(3), 109–114.

- Pretty, J. N. (1995). Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Development, 23(8), 1247–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00046-F

- Reid, D. G., Mair, H., & Taylor, J. (2000). Community participation in rural tourism development. World Leisure Journal, 42(2), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2000.9674183

- Saldana, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers - Johnny Saldana - Google books. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00069-7

- Scheyvens, R. (2002). Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Prentice Hall.

- Scheyvens, R. (2003). Local involvement in managing tourism. In S. Singh, D. J. Timothy, & R. K. Dowling (Eds.), Tourism in destination communities (pp. 229–252). CABI.

- Scheyvens, R. (2011). The challenge of sustainable tourism development in the Maldives: Understanding the social and political dimensions of sustainability. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 52(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2011.01447.x

- Sebele, L. S. (2010). Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino sanctuary trust, central district, Botswana. Tourism Management, 31(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Tourman.2009.01.005

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Sène-Harper, A., & Séye, M. (2019). Community-based tourism around national parks in Senegal: The implications of colonial legacies in current management policies. Tourism Planning and Development, 16(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1563804

- Sofield, T. (2003). Empowerment for sustainable tourism development. Pergamon.

- Stone, M. T., & Nyaupane, G. (2014). Rethinking community in community-based natural resource management. Community Development, 45(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2013.844192

- Strzelecka, M., Boley, B. B., & Strzelecka, C. (2017). Empowerment and resident support for tourism in rural central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The case of Pomerania, Poland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4), 554–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1224891

- Strzelecka, M., & Wicks, B. (2010). Engaging residents in planning for sustainable rural- nature tourism in post-communist Poland. Community Development, 41(3), 370–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330903359614

- Sutawa, G. K. (2012). Issues on bali tourism development and community empowerment to support sustainable tourism development. Procedia Economics and Finance, 4, 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(12)00356-5

- Telfer, D. J., & Sharpley, R. (2008). Tourism and development in the developing world. Routledge.

- Tiberghien, G. (2019). Managing the planning and development of authentic eco-cultural tourism in Kazakhstan. Tourism Planning and Development, 16(5), 494–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1501733

- Timothy, D. J. (1999). Participatory planning a view of tourism in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00104-2

- Timothy, D. J. (2007). Empowerment and stakeholder participation in tourism destination communities. In A. Church, & T. Coles (Eds.), Tourism, power and space (pp. 199–216). Routledge.

- Timothy, D. J., & Tosun, C. (2003). Appropriate planning for tourism in destination communities: Participation, incremental growth and collaboration. In S. Singh, D. J. Timothy, & R. K. Dowling (Eds.), Tourism in destination communities (pp. 181–204). CABI.

- Tosun, C. (1999). Towards a typology of community participation in the tourism development process. Anatolia, 10(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.1999.9686975

- Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- Tosun, C. (2005). Stages in the emergence of a participatory tourism development approach ing the developing world. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 36(3), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.06.003

- Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27(3), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- Tosun, C., & Jenkins, C. L. (1998). The evolution of tourism planning in third world countries: A critique. Progress In Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1603(199806)4:2<101::AID-PTH100 > 3.0.CO;2-Z

- Tosun, C., & Timothy, D. J. (2003). Arguments for community participation in tourism development. Journal of Tourism Studies, 14(2), 2–11.

- Tribe, J. (2001). Research paradigms and the tourism curriculum. Journal of Travel Research, 39(4), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750103900411

- van der Duim, R., Peters, K., & Akama, J. (2006). Cultural tourism in african communities: A comparison between cultural Manyattas in Kenya and the cultural tourism project in Tanzania. In M. K. Smith, & M. Robson (Eds.), Cultural tourism in a changing world: Politics, participation and (re)presentation (pp. 89–103). Channel View Publications.

- Willis, K. (2011). Theories and practices of development. In Routledge perspectives on development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00219_1.x

- Yang, L., Wall, G., & Wall Ãã, G. (2008). The evolution and status of tourism planning: Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 5(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530802252818