ABSTRACT

Despite high levels of mental disorders among young people living in residential youth care (RYC) institutions, only a small percentage of these children receive help from mental health services. The aim of the present study is to explore the usefulness of an inter-agency collaboration model from the perspective of service providers, and to investigate factors that promote and hinder effective inter-agency collaboration around early identification and follow up of mental problems and disorders among youth in residential care. A purposive sample of 16 professionals in three RYC institutions and related child and adolescent mental health services and child welfare services that were involved in piloting the collaboration model was recruited. Semi-structured individual and group interviews were conducted, and a thematic analysis was conducted to identify key themes. The results suggest that the collaboration model promoted increased awareness on mental health issues and a greater systematic inter-agency collaborative effort in assessing and following up the mental health of children and adolescents in RYC institutions. However, there were major challenges related to central elements of the collaboration model; the conduction of the multidisciplinary meeting within the deadline of three weeks, and participation of child welfare services-providers at the multidisciplinary meeting. Further dissemination of the collaboration model merits further consideration of the choice of screening assessment battery due to the lack of participation from teachers and parents, the time limit of three weeks and measures to increase participation from the municipal child welfare services.

Introduction

Young people living in residential youth care (RYC) institutions have a high risk of developing mental health problems and disorders (Janssens and Deboutte Citation2010; Schmid et al. Citation2008; Bronsard et al. Citation2016; Jozefiak et al. Citation2016; Besier, Fegert, and Goldbeck Citation2009; Greger et al. Citation2015). A recent Norwegian study on mental health among adolescents (N = 400) aged 12–20 years old and living in residential youth care was carried out in 2010–2015 (Jozefiak et al. Citation2016). The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (Angold and Costello Citation2000) to assess psychiatric disorders according to the DSM‐IV‐TR (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). The results indicated that 76.2% of the adolescents fulfilled the criteria for at least one DSM‐IV diagnosis within the past 3 months. Only 25.1% of the adolescents reported having received help from the child and adolescent mental health services in the same timeframe (Jozefiak et al. Citation2016). This indicates a large disparity between healthcare needs and access. The large disparity between healthcare needs of youth in residential youth care institutions and access to specialized help is also reported in studies conducted in Germany (Besier, Fegert, and Goldbeck Citation2009), Spain (González-García et al. Citation2017), and the US (Burns et al. Citation2004).

Screening of mental health among youth in residential care institutions

To reduce the discrepancy between the need for and receipt of mental health services for children in residential youth care institutions, mental health screening using validated measuring instruments (i.e. questionnaires) has been suggested (Jozefiak et al. Citation2016; Janssens and Deboutte Citation2009; González-García et al. Citation2017; Martín et al. Citation2020; Whyte and Campbell Citation2008). Research indicates that young people are generally more accepting of self-administered questionnaire-assessments of mental health, rather than assessments relying completely on verbal disclosure (Bradford and Rickwood Citation2012). A study by McNamara and Neve (Citation2009) reported that many social workers were sceptical towards using standardized screening instruments to identifying the child’s problems, unless the screening instruments also mapped the child’s strengths. The authors highlight the importance of implementation of screening instruments to take place in close cooperation between authorities, practitioners, and researchers.

A recent study by Martín et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the importance of using a multi-informant (i.e. youth self-report, parent/social worker, and teacher report) approach to detect behavioural and emotional disorders in residential child care. They found that social workers tended to score more highly in externalizing scales, whereas the young people reported more internalizing problems. The value in multi-informant assessments lies in capturing the unique perspectives of each informant providing a report (Achenbach Citation2006). Still, there remains a missing link between the information gathered during a mental health screening and the subsequent follow-up and treatment of the children (Salbach-Andrae, Lenz, and Lehmkuhl Citation2009; Janssens and Deboutte Citation2009). Policymakers and researchers have therefore emphasized that systematic collaborative efforts to detect (and subsequently treat) mental health problems between the child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services are needed (Jozefiak et al. Citation2016; He et al. Citation2015; The Norwegian Directorate for Children Youth and Family Affairs/The Norwegian Directorate of Health Citation2015). There are indications that inter-agency collaboration between child welfare services (CWS) and child and adolescent mental health services improves early identification of mental health problems, as well as improved access to help (Bai, Wells, and Hillemeier Citation2009; Darlington and Feeney Citation2008; Timonen-Kallio Citation2019). Nevertheless, effective inter-agency collaboration has been reported to be difficult to achieve (Darlington and Feeney Citation2008; Stanley et al. Citation2003), also in Norway (Lehmann and Kayed Citation2018; Jozefiak et al. Citation2016; Lauritzen, Vis, and Fossum Citation2017; Pedersen Citation2019).

Barriers for inter-agency collaboration between the child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services

Barriers for effective inter-agency collaboration are reported at individual, group and organizational level. Insufficient knowledge about the role and responsibilities of the professionals in the other services, absence of a culture of collaboration, lack of effective collaboration structures and guidelines for collaboration and different organizational priorities have been found to be barriers for the initiation and continuation of inter-agency collaboration (Darlington, Feeney, and Rixon Citation2005; Johnson et al. Citation2003; Timonen-Kallio Citation2019; Chuang and Wells Citation2010). Communication is one of the most central aspects of effective collaboration (Johnson et al. Citation2003; Timonen-Kallio Citation2019). However, differences in conceptual frameworks, knowledge bases, and discourses in the child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services may lead to difficulties in communication and joint decision-making, as well as different understandings of the children’s need for mental health services. Furthermore, confidentiality policies and practices may vary across services, and these differences might hinder communication (Hall Citation2005; Timonen-Kallio Citation2019; Cooper, Evans, and Pybis Citation2016). Timonen-Kallio (Citation2019) investigated and compared interprofessional collaboration between residential child care (RRC) and mental care (MC) practitioners in six European countries. The study indicated that the barriers for collaboration and coordination between systems between RCC and MC sectors were relatively similar across Europe.

In the USA, Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) and Department of Mental Health (DMH) developed a collaborative model detailing steps for systematic screening, assessment, referral, and continuum of care for mental health needs of DCFS-involved children. He et al. (Citation2015) reported that this systematic inter-agency collaboration facilitated the mental health screening of a large cohort of child welfare services involved children, which in turn contributed to improved detection of need and referral for services. The establishment of collaborative resource teams allowed tracking of the screening and referral process between agencies and ensured the identification of mental health needs among child welfare services involved children and referral to appropriate mental health services (He et al. Citation2015). Despite the obvious need for working together, international research literature is scarce on interventions and inter-agency collaboration between child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services (Timonen-Kallio Citation2019; Whittaker et al. Citation2016).

Models for inter-agency collaboration for early identification and assessment of healthcare needs among children living in residential youth care institutions

In 2017, the Norwegian official report ‘Summary and recommendations from work on healthcare for children placed in alternate care by the child protection services’ (Directorate for Health/Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs Citation2016) was released. The aim of the report was to improve access to mental health services for children placed in alternate care and enhance the collaboration between child and adolescent mental health services and child welfare services. Several specific recommendations were given for the future organization of services and legislative changes. One of the recommendations was that inter-agency cooperation for early identification and assessment of healthcare needs when children are moved out of home should be strengthened. The recommendation calls for further development of methods and models to secure early identification and thorough assessment of service needs in cooperation between child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services. Hence, to improve early identification of mental health problems among children in residential youth care institutions, the Norwegian Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, therefore, developed an inter-agency collaboration model that was tested in a pilot project involving three residential youth care institutions and associated child and mental health outpatient clinic and municipal child welfare services in central Norway. The overall aim of the present study is to explore the usefulness of the collaboration model from the perspective of service providers, and to investigate factors that promote and hinder effective inter-agency collaboration around early identification and follow up of mental problems and disorders among youth in residential care.

Methods

The current study is a qualitative retrospective evaluation of the inter-agency collaboration model that was tested out in the abovementioned pilot project. The research project was assigned to the research team after competition with other providers. The research team was not involved in the design and development of the collaboration model and was not involved in neither the design nor execution of the pilot project. The study, from which we report in the article, was conducted as a contract research project for the Norwegian Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs as our client, where we in retrospect assessed the model in use. A qualitative approach was chosen to explore perceptions about the model from participants’ own viewpoint (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2020).

Setting

The Norwegian Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat)

The Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat) is an agency under the Ministry of Children, Equality and Social Inclusion. Bufetat is divided into five underlying regional organizations and an overall executive body, called the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufdir). Bufetat is responsible for matters relating to state-funded child welfare services, including residential youth care institutions (Bufdir Citation2020).

Municipal child welfare services

The Norwegian Child Welfare Services are the public agency responsible for child protection in Norway. They consist of services in each municipality, which are supervised and aided by various governmental bodies at the state as well as the county level. All municipalities or inter-municipalities must have a Child Welfare Service that performs the day-to-day tasks required by the Child Welfare Act. The Service is responsible for: Child welfare cases and performing investigations [Child Welfare Act § 4–3]; Home-based assistance; Child Welfare Emergency Unit; Out-of-home placements (including residential youth care institutions); Monitoring out-of-home placements; and Approval of foster homes (Bufdir Citation2020).

The child and adolescent mental health services

The child and adolescent mental health services are placed under the Norwegian Directorate of Health and organized in state-owned health trusts, and a referral is needed for the screening, assessment, and treatment of mental health problems. Outpatient therapy is the most usual form of treatment (Norwegian Directorate of Health Citation2020).

Residential youth care institutions

In Norway, there are four types of state-run residential care institutions: 1) youth care institutions, 2) institutions for youth with serious behavioural problems, 3) emergency placement- and assessment institutions, and 4) substance abuse placements. The state-run residential care institutions are almost exclusively for youth age 13–18 years. Most Norwegian residential youth care institutions are small units with three to five residents, where most of the adolescents are attending school and participating in leisure activities. The present study involved three residential youth care institutions located in central Norway. The institutions were open care institutions (unlocked), which is the normal practice in Norway (Bengtsson and Böcker Citation2009).

The collaboration model

The purpose of the collaboration model was to develop and test/pilot new collaboration forms and routines involving three residential youth care institutions and their respective local child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinics and child welfare services, to ensure that recently entered children and young people receive the necessary healthcare their mental health difficulties.

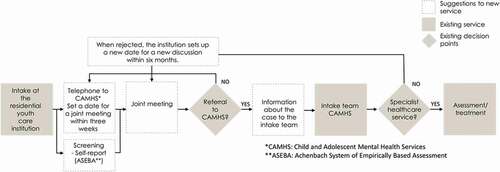

The collaboration model is presented in . At the intake at the residential youth care institutions, the residential youth care institutions employees are responsible for screening the child or adolescent by using the relevant questionnaire from The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). The Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat) in Norway has recommended that ASEBA should be used as a screening instrument in the context of open care institutions (Bufetat Citation2018). ASEBA is one of the most frequently used instruments to assess child psychopathology and shows good psychometric properties (Kornør and Jozefiak Citation2012; Heyerdahl, Kvernmo, and Wichstrøm Citation2004; Hanssen-Bauer et al. Citation2010; Baams, Wilson, and Russell Citation2019; Martín et al. Citation2020). ASEBA consists of questionnaires to be administered by the parents (Child Behaviour Checklist, CBCL), teacher (Teacher’s Report Form, TRF) and children (Youth Self Report, YSR), aged 11 years and older. The results from ASEBA are to be sent to the child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinic locally, and a multidisciplinary meeting should be arranged within three weeks from the placement date (independent of the scores on ASEBA). The participants of the multidisciplinary meeting should include representatives from the residential youth care institution, child and adolescent mental health services and the child welfare services. A template for carrying out the multidisciplinary meeting was developed and used in the pilot project. At the end of the meeting, recommendation of further referral or not to the child and adolescent mental health services should be made. If it is considered that the referral is not necessary, one should make a new assessment/follow-up within 6 months.

The pilot project – testing the collaboration model

Three residential youth care institutions and associated child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinics and municipal child welfare services were involved in piloting the collaboration model. When piloting the collaboration model, documentation forms, developed by the working group, was used to register the collaboration- and decision-making processes. The documentation forms included registration of relevant dates (e.g. intake, multidisciplinary meeting) and conclusion from the multidisciplinary meeting (referral or not). The institutions were responsible for completing the forms, which were systematically reviewed by the research team to provide an overview of the cases involved in the collaboration model. A total of 21 children and adolescents (6 to 18 years) were involved in the pilot project. There were 11 adolescents who had completed the ASEBA (Youth self-report). In the documentation sheets, reasons were listed why the adolescent had not filled out the ASEBA. In nine of 21 cases ASEBA was not completed because the child/adolescent was already in treatment at the child and adolescent mental health services; hence, mental health screening and assessment of mental health status was already done. Consequently, a multidisciplinary meeting was not conducted in these cases. None of the cases had registered information about completion of the Teacher report form (TRF) or the Child behaviour checklist (CBCL) in the documentation form due to lack of registration from the employees and the fact that often did not receive this from teachers and parents.

The evaluation of the collaboration model

A qualitative approach was used to collect rich data (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2015) and understand the diversity and complexity associated with piloting the collaboration model. Qualitative methodology is useful for exploring barriers and facilitators to implementation (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey Citation2020). Semi-structured interviews were chosen to allow unrestricted focus on the research question with freedom to explore emerging issues with participants (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2015). Where possible, group interviews were conducted. Unlike individual interviews, group interviews obtain information through a dynamic interaction between participants (and interviewee). This is information that often remains unspoken through other data collection techniques such as individual interviews (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2015). For pragmatic reasons, some individual interviews were also carried out.

Recruitment and sample

The sample was established by the use of a purposive sampling strategy, which sees to recruit information-rich cases that yields insights and in-depth understanding (Patton Citation2014). Individuals that were involved in the development and piloting the collaboration model was recruited, since we wanted informants who had first-hand experience about working according to the collaboration model. The recruitment process was predominantly done by the first author (JK). The first contact was established with the managers of the respective services by telephone. Next, the managers received written information about the research project and invitation to participate by email. This information was forwarded to relevant informants. The mangers identified and established contact with employees who had first-hand experience with the pilot project, and they distributed contact information for those individuals who were positive to participate in the research team.

In total, 16 individuals participated in the interviews (). Initially, a group interview was conducted with five representatives from the working group (i.e. the group of individuals that were actively involved in the development of the collaboration model); two representatives from the residential youth care institutions, one representative from the Child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinic and three representatives from The Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat) in Norway. The purpose was to obtain background knowledge about the collaboration model (i.e. previous challenges in inter-sectorial collaboration, why the model was developed, and the process of developing the model), as well as to get detailed knowledge about the new forms of collaboration, routines and the expected benefits of the collaboration model.

Table 1. Number (N) of participants and interviews in the study.

At the first youth institution, one group-interview was conducted with two social workers and one individual interview with the manager. From the second youth institution, the manager was interviewed, and from the third youth institution, a group interview was conducted with the manager and one social worker. Furthermore, a group interview was conducted with one informant from each of the three different child and adolescent mental health outpatient clinics that were involved in the pilot project. Individual interviews were conducted with social workers from the child welfare service in two different municipalities. All informants received oral and written information about the research project, and informed consent was signed by all participants.

Data collection

We developed a thematic interview guide addressing three main topics: 1) Overall experiences with the collaboration model, 2) Inter-Agency collaboration (e.g. roles, responsibility and information-flow), and 3) Experiences – the usefulness of the model (e.g. improved assessment/screening and follow-up of the adolescents). Interviews were conducted by two researchers from the research team (JK and LM) during February to April 2017. The interviews were conducted in person in a meeting room at the informants’ work-place. The interviews lasted from one to one and half hour and was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The presentation of quotations from interviews have been slightly modified from oral expressions to written language in order to promote their comprehensibility. When preparing the manuscript, the quotations were translated from Norwegian to English by the research team.

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted to identify key themes. In the analyses of the qualitative interviews, we have drawn inspiration from thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Joffe, Citation2012). After a thorough reading of the interviews, the researchers went through the data material again and coded the most important topics and what was most clearly expressed, while we searched for themes and categories. In this phase, we also looked specifically at the themes that were relevant to elucidate the issues in the project, and thus the issues functioned as a kind of thematic/analytical framework. After this coding, we went through the material again and looked at the relationship between the interviews. In this phase, we also merged categories that we saw to be overlapping. Defining and naming categories and findings was done at the same time as the writing process, and then also with special attention to the issues that were outlined before the project. In addition, new themes and perspectives have emerged.

Ethical considerations

The study has been independently reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, reference number (52,789), and the research has been carried out in accordance with ethical principles in line with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The interviews were conducted with the understanding and written consent of each subject and according to the above-mentioned principles. The informants were informed about how the material would be used.

Results

In the analysis we identified four main themes that seemed to affect the service providers’ experiences with the collaboration model, including factors that promoted and hampered effective inter-agency collaboration around early identification of mental problems and disorders among youth in residential care: 1) Faster access to the child and adolescent mental health services if needed – the role of the deadline; 2) Increased inter-agency commitment and communication; 3) The use of ASEBA – increased awareness of mental health issues and the multi-informant perspective and 4) Introduction of the multidisciplinary meeting.

Faster access to the child and adolescent mental health services if needed – the role of the deadline

One of the most notable changes because of the new collaboration model, highlighted by most of the informants, is that all young people who arrive in one of the three care institutions are guaranteed a screening and multidisciplinary assessment of their mental health. One residential youth care institution employee expressed;

“What I think is the difference, it is that we notify [their respective child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinic] immediately, and we’ll have a meeting, so we know that it [potential mental problems or disorders] will be identified.”

Most of the service providers perceived that the model contributed to expedite access to child and adolescent mental health services for the adolescents if they had mental problems or disorders. The deadline of three weeks – from intake to the multidisciplinary meeting, was mentioned by most informants as a crucial factor that promoted collaboration and interaction, even though the deadline in many cases was not met. All the service providers from the child and adolescent mental health services and the institutions believed that a pressure (i.e. the deadline) on all involved service providers – ”got things done”. One of the residential youth care institution employee expressed:

The advantage [of the model/pilot project] is that we get a psychiatric assessment of the adolescents early in their stay, so we can initiate early efforts if necessary. So, if the screening indicates that we have an adolescent with major problems, a referral to the CAMHS outpatient clinic will be done right away. And, in such cases, we experience that there is a short waiting time. They get treatment quickly.

Overall, the informants from the municipal child welfare services were also positive towards the deadline. However, several informants from the child and adolescent mental health services and the residential youth care institutions emphasized that it could often be a challenge to set a date for the multidisciplinary meeting with the employees of the child welfare services within the three weeks’ deadline. One of the employees at a residential youth care institution said that in the context of acute-placements, the three weeks deadline could be too short, and that they had experienced problems establishing contact with the child welfare services – in such cases. An informant from the residential youth care institution explained that they had used the deadline more as a guidance:

If this [new practice] should continue, I think the deadline of three weeks is too short. Because, the adolescents need to settle in a little bit, before they evaluate themselves. We have used the deadline as a guideline/guidance, because it has not always been possible to comply with deadline.

Increased inter-agency commitment and communication

Overall, the service providers expressed positive experiences with the collaboration model. The model was relatively simple and not very different from previous practice, so there had been little need for training. Some of the service providers pointed out that one strength of the collaboration model is that roles and responsibilities are well clarified. Furthermore, the introduction of a fixed contact person in child and adolescent mental health services was accentuated as positive by the employees at the institutions. Many service providers argued that the advantage of closer contact through a fixed contact person was bidirectional:

We have a contact person at the child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinic, and it’s very useful that we only have one person to relate to (Residential youth care institution).

In my opinion, one of the benefits with this collaboration model is … . It is easy to get in touch with each other, they know your face, have knowledge about the collaboration, and this sort of influence our awareness (child and adolescent mental health services).

All informants from the child and adolescent mental health services expressed the advantages for them to be more familiar with the institutions. Such an arrangement also increased the possibility of further cooperation on other matters (e.g. acute cases or counselling). Most of the service providers emphasized the positive aspects related to communication between the institutions and child and adolescent mental health services, there were some informants who thought that the communication became more open. One informant from the child welfare services – explained:

The child and adolescent mental health services have kept the cards a little tight, we think. It has somehow been a separate field [Child and adolescent psychiatry], and we haven’t gotten as much feedback on what has happened. It is more open now.

3.3The use of ASEBA – increased awareness of mental health issues and the multi-informant perspective

All the service providers expressed positive attitudes towards the screening of mental health. The introduction and use of the ASEBA-instrument for screening mental health problems among adolescents at the residential youth care institutions were considered as a central and positive feature of the collaboration model by most of the informants. While it can be somewhat challenging to fill out the ASEBA forms, and employees could be insecure about the meaning of the answers, the informants still believed that the completion of the questionnaire was positive. They argued that filling out the questionnaire leads to more attention to mental health issues in general and increased awareness on the specific themes/questions addressed in the questionnaire (Youth self-report (YSR)):

I think it’s noticeable that we’re getting into position faster today than we did before (…). You’ll get into the problem faster. Before, we spent a little longer figuring everything out … and mental health problems among some youth would not be identified. When conducting the screening early in the process, we get more focused and aware of mental health issues.

Some of the residential youth care institutions staff expressed that they had used results from the YSR (ASEBA) as a tool for conversations with the adolescents.

Sometimes we get a very superficial impression of the youth when they come. They are nice and seem resourceful and we draw our conclusions. But through the screening, we realized that there are some thoughts that needs to be followed-up.

The service providers valued the use of multi-informant-perspective of ASEBA in that different perspectives (youth, parents/caregivers and school) on the adolescent mental health are presented. Some of the residential youth care institutions employees said that they had experienced a big difference between how they considered a youth and what the youth report in the self-report, and the subsequent score. Another informant also found that their image of the youth became more nuanced after comparing their own experiences with how the youth considered themselves. However, in the pilot project, there were challenges related to ensure the completion of more than one perspective. For instance, the employees at the institutions expressed that it was difficult for them to answer the questions in the Child behaviour checklist (CBCL) before the multidisciplinary meeting, as they barely knew the adolescent at this point of time. At the institution for children under 12 years of age, there were no use of the YSR, only the CBCL, as the children were too young to complete the YSR. The informants explained that they had made it a routine that two employees independently completed the CBCL, as advised from the child and adolescent mental health services. One informant from one of the institutions expressed:

It is difficult [completing the ASEBA/CBCL (“parent”-report)], but you must use what you have experienced until now. After two weeks, you don’t really know the child.

At the two other institutions, most of the adolescents completed the YSR, except those who were already in specialized treatment, before intake at the residential youth care institutions. In such cases, the completion of ASEBA and subsequent multidisciplinary meeting were not conducted. The residential youth care institutions staff highlighted the importance of giving the adolescents thorough information about the purpose of the mental health screening and about the possibilities of help from the child and adolescent mental health services if needed.

The informants from the residential youth care institutions had the impression that the youth completed the YSR seriously. Some adolescents, however, might think there were a lot of questions and some get a little bored and might get a little sloppier at the end. In cases where residential youth care institutions employees experienced the adolescents to be sloppy with the questionnaire, or were unmotivated, it could happen that they sat down with the youth and ‘guided them a little bit’.

The informants explained that relatively few Teacher report-form (TRF) were completed by the teachers. The staff at the RYC institutions explained that they prioritized the completion of the YSR and the CBCL. The responsibility for collecting TRF data seemed less clarified. In some cases, the adolescents had changed schools, which also made the collection of TRF more complicated.

The introduction of the multidisciplinary meeting

The basis for deciding if the child/adolescent should be referred to child and adolescent mental health services includes a review of the results of ASEBA and an (interdisciplinary) discussion in a multidisciplinary team meeting. Most of the service providers underlined that it is necessary that ASEBA is complemented by the service providers’ knowledge of the adolescent and the case to get the ‘full picture’ of the youth. In the interviews, it emerged that the multidisciplinary meeting usually involves participation from two residential youth care institution employees and one or two employees from the child and adolescent mental health services. In rarer cases, a social worker from the municipal the child welfare services participated as well. The lack of time resources and the overburdening of the municipal the child welfare services were expressed by the informants as the main reasons for the absence of the municipal the child welfare services in the meetings. The informants emphasized the need for the municipal the child welfare services to participate at the multidisciplinary meeting as they represent an important source of information about the child/adolescent. One informant from the child and adolescent mental health services explained:

I think they’ve [municipal the child welfare services] joined the meeting only a few times. And when the meeting has been held shortly after intake, it has been a little difficult because they [the employees at the institution] don’t known the adolescent well enough. So, we’d consider several aspects of mental health that is not observed very well.

The informants explain that the social worker in the child welfare services might represent a more comprehensive knowledge of the child and their background. In certain cases, it is possible that the documentation basis may be less extensive than desired (e.g. unaccompanied minor refugees). Overall, the informants did nevertheless perceive the multidisciplinary meeting as an adequate basis for discussing potential referral to the child and adolescent mental health services, and there appears to be a large degree of consensus on the decisions made in these meetings.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore the usefulness of a collaboration model that was designed to ensure screening of child and adolescent mental health at the intake in residential youth care institutions, and subsequently referral to child and adolescent mental health services if needed. To our knowledge, there are no existing studies evaluating models for inter-agency collaboration for early identification and follow-up of mental health problems in residential youth care in Norway. The current study adds to the existing literature by investigating the perspectives of employees in residential youth care institutions, municipal child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services. The results indicate that the model contribute towards increased attention to mental health issues and improved and faster access to specialized help if needed. The service providers generally expressed positive experiences with the collaboration model, and they perceived that the model contributed to improved inter-agency collaboration, as well as enabling a systematic screening of all newly entered adolescents and a routine for subsequent treatment or follow-up if needed.

The results from the present study suggest that the collaboration model, including the use of systematic screening of mental health with a standardized screening instrument was well perceived and accepted by the service providers. This contrast the finding of McNamara and Neve (Citation2009) that reported that many Australian and Italian social workers were sceptical towards using standardized screening instruments. In Norway, the ‘Kvello-template’, a mapping template that systematizes collected information in child welfare cases and forms the basis for further child care work, is implemented in municipal child welfare services in Norway. Although there is disagreement both among scientists and practitioners about the importance of standardized screening tools as a source of knowledge for the investigation of children (Backe-Hansen Citation2009; Munro Citation2011; Kjær Citation2017; Lauritzen et al. Citation2017), it is possible that ‘Kvello’ framework might influence the service providers’ attitudes towards screening, thus making them more positive than in other comparable countries. This conflicting finding could also be a result of the limited sample size in the current study. More research is needed to disentangle such effects.

The basis for assessing the mental health status of the newly entered residents at the residential youth care institution included the use of ASEBA and a multidisciplinary discussion at the joint meeting and was considered by the informants in the present study as valuable and adequate. However, there were challenges related to the full utilization of multi-informant perspective of ASEBA, in particular teacher and parent reports (TRF, CBCL). Although the ASEBA is recommended as a screening assessment battery by the Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat) in Norway, the adequacy might be questioned. The lack of multi-informant assessment brings about some uncertainty about how well adolescents in need of psychiatric treatment will be identified. Nevertheless, the limitations related to multi-informant assessment highlight the importance of the ASEBA being supplemented with other information, as also indicated in previous studies (He et al. Citation2015; Janssens and Deboutte Citation2009; Salbach-Andrae, Lenz, and Lehmkuhl Citation2009). The presence of representatives of all service providers (i.e. municipal CWS, child and adolescent mental health services and residential youth care institutions) at the multidisciplinary meeting seems to be a critical element of the collaboration model as the various service providers represent different knowledge and perspectives on the adolescents’ mental health and subsequent need of help. However, it is worth noting that the adolescents were not included in the development of the collaboration model, nor in the multidisciplinary meeting, and there were few reflections among the informants in the present study about that theme. Further development of similar models could benefit from involvement of the youth.

The deadline for having the multidisciplinary meeting was highlighted as a facilitating factor for inter-agency collaboration in the present study. However, there were some challenges related to keeping the deadline of three weeks and the participation from the municipal CWS at the multidisciplinary meetings. This means that there could be a huge time gap between the completion of ASEBA and the multidisciplinary meeting. Consequently, even if ASEBA is completed early on, the lack of interpretation and discussion of the results could delay the referral to the child and adolescent mental health services. The lack of participation of the municipal the child welfare services was mainly related to limited time resources and high case load. These are well-known factors that inhibit inter-agency collaboration (Darlington and Feeney Citation2008; Chuang and Wells Citation2010). In Norway, many professionals in the municipalities face large geographical dispersion. To improve the participation of the municipal the child welfare services, it is likely that the use of videoconference could be beneficial to ensure that the perspectives from the municipal CWS will be included at the multidisciplinary meetings to a larger degree. Furthermore, it is possible that the absence of representatives from the municipal the child welfare services in the development of the collaboration model might have resulted in less organizational alignment from the child welfare services’ side, and consequently less participation in the meetings. If further dissemination of the model, the municipal the child welfare services should be involved to a larger degree.

In line with previous studies on inter-agency collaboration (Darlington, Feeney, and Rixon Citation2005; Johnson et al. Citation2003; Timonen-Kallio Citation2019; Chuang and Wells Citation2010), the present study indicates that the creation of joint routines and clarification of roles and responsibility were important factors that promoted inter-agency collaboration and communication. In the current study, the informants expressed that the introduction of a fixed contact person was a positive feature of the model that promoted communication between the institutions. The discussions in the multidisciplinary meetings seemed to contribute towards a more common understanding of the children’s need for mental health services as well as reduction of potential differences in conceptual frameworks, knowledge bases, and discourses in the child welfare services and child and adolescent mental health services. This concurs with Bai, Wells, and Hillemeier (Citation2009), who point out that more ties with mental health providers may help child welfare agencies improve children’s mental health service access and outcomes.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The current study has several limitations. A major limitation of the current study was the retrospective nature of data collection and the potential recall bias of respondents who were asked about their experiences with working according to the collaboration model in retrospect (Hassan Citation2006). However, the interviews were carried out within a relatively short time span after the pilot project was finished (i.e. up to approximately 6 months after) which reduce the risk of recall bias somewhat.

The sample size is small, limiting the transferability of the results, although the findings are consistent with other studies that used larger samples (He et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, it is possible that the youth institutions involved in the pilot project had a somewhat positive collaboration with their respective child and adolescent mental health services outpatient clinic before the pilot project. This factor might have contributed to the perceived success of the pilot test of the collaboration model. If further dissemination of the collaboration model, the collaboration model should be tested where the collaboration between the child and adolescent mental health services and the child welfare services also has been scarce and/or problematic. This study does not explore the causal chain between inter-agency collaboration and changes in adolescents’ mental health status and access to treatment. Still, the results indicate that more adolescents will receive a thorough assessment of their mental health and expedite the access to the child and adolescent mental health services if needed.

Implications for practice and research

Though other studies have outlined the concerns of high prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in residential youth care institutions and subsequent need of help, there is few existing studies of models or interventions designed to meet their needs. The current study adds to the existing literature by exploring one such model. Since help-seeking behaviour of adolescents is relatively rare, and many adolescents’ mental problems or disorders are not immediately noticeable at the intake in residential youth care institutions, a model of mental health screening and routines for follow-up seems promising to ensure early identification of mental disorders and to give a proper treatment, follow up and to prevent persistent difficulties. Furthermore, multi-informant assessment (i.e. adolescent self-report, teacher-report, parent/social worker) combined with the perspectives from different service providers could support the clinician to design appropriate interventions to address potential behavioural problems and/or mental disorders. While not definitive, this study does provide some useful insights that can inform future, more rigorous research in this area. The retrospective analyses are beneficial before planning larger-scale prospective studies. Further investigation using a larger, longer term, randomized controlled study design, with more detailed monitoring to clarify the mechanisms by which the collaboration model may produce improvements in inter-agency collaboration and whether such improvements can be maintained in the longer term is needed.

Conclusion

The results suggest that the collaboration model promoted increased awareness on mental health issues and a greater systematic inter-agency collaborative effort in assessing and following up the mental health of children and adolescents in residential youth care institutions. There is a closer contact between providers in the institutions and in the child and adolescent mental health services, and the collaboration is perceived as more binding. The use of a deadline for assessment of mental health status, a relatively brief time after intake (e.g. three weeks) and expedite access to the child and adolescent mental health services if necessary. However, there were major challenges related to central elements of the collaboration model, the conduction of the multidisciplinary meeting within the deadline of three weeks, and participation of child welfare services-providers at the multidisciplinary meeting. Further dissemination of the collaboration model merits further consideration of the choice of screening assessment battery due to the lack of participation from teachers and parents, the time limit of three weeks, and measures to increase participation from the municipal the child welfare services at the multidisciplinary meeting. The child welfare services and adolescents should be represented in further development of the collaboration model.

Declarations interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JK, LM and MÅ designed the study. JK and LM carried out the data collection and conducted the analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, and the final version is approved by all authors.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Bufetat region central Norway, Gunn Helen Wikan and Asgeir Sonstad, for the good cooperation. The authors will also express gratitude to the staff at the residential youth care institutions, child and adolescent mental health services, the employees in municipal child welfare services who shared their experiences.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achenbach, T. M. 2006. ““As Others See Us: Clinical and Research Implications of Cross-informant Correlations for Psychopathology.” Review Of.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 15 (2): 94–98. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00414.x.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington: American Psychiatric Pub.

- Angold, A., and E. J. Costello. 2000. ““The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA).” Review Of.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 39 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015.

- Baams, L., B. D. M. Wilson, and S. T. Russell. 2019. ““LGBTQ Youth in Unstable Housing and Foster Care.” Review Of.” Pediatrics 143: 3. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4211.

- Backe-Hansen, E. 2009. “Hva Innebærer Et Kunnskapsbasert Barnevern?” Fontene Forskning 2 (9): 4–16.

- Bai, Y., R. Wells, and M. M. Hillemeier. 2009. “‘Coordination between Child Welfare Agencies and Mental Health Providers, Children’s Service Use, and Outcomes.’ Review Of.” Child Abuse & Neglect 33 (6): 372–381. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.004.

- Bengtsson, T. T., and T. Böcker. 2009. Institutionsanbringelse Af Unge I Norden. (Residential Care Placements for Young People in the Nordic Countries). Copenhagen: SFI-Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd.

- Besier, T., J. M. Fegert, and L. Goldbeck. 2009. ““Evaluation of Psychiatric Liaison-services for Adolescents in Residential Group Homes.” Review Of.” European Psychiatry 24 (7): 483–489. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.02.006.

- Bradford, S., and D. Rickwood. 2012. “Psychosocial Assessments for Young People: A Systematic Review Examining Acceptability, Disclosure and Engagement, and Predictive Utility.” Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 3: 111–125. Review of. doi:10.2147/ahmt.s38442.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101.

- Bronsard, G., M. Alessandrini, G. Fond, A. Loundou, P. Auquier, S. Tordjman, and L. Boyer. 2016. “The Prevalence of Mental Disorders among Children and Adolescents in the Child Welfare System: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Medicine 95 (7): e2622. Review of. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002622.

- Bufdir. 2020. “The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs.” Accessed 21 August. https://bufdir.no/en/English_start_page/

- Bufetat. 2018. “Veileder Til Standardisert Forløp: Trygge Og Virkningsfulle Tiltak for Barn Og Familier (Norwegian).” https://bufdir.no/Bibliotek/Dokumentside/?docId=BUF00004791

- Burns, B. J., S. D. Phillips, H. R. Wagner, R. P. Barth, D. J. Kolko, Y. Campbell, and J. Landsverk. 2004. “Mental Health Need and Access to Mental Health Services by Youths Involved with Child Welfare: A National Survey.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 43 (8): 960–970. Review of. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65.

- Chuang, E., and R. Wells. 2010. “The Role of Inter-agency Collaboration in Facilitating Receipt of Behavioral Health Services for Youth Involved with Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice.” Children and Youth Services Review 32 (12): 1814–1822. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.002.

- Cooper, M., Y. Evans, and J. Pybis. 2016. “Interagency Collaboration in Children and Young People’s Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Outcomes, Facilitating Factors and Inhibiting Factors.” Child: Care, Health and Development 42 (3): 325–342. Review of. doi:10.1111/cch.12322.

- Darlington, Y., and J. A. Feeney. 2008. “Collaboration between Mental Health and Child Protection Services: Professionals’ Perceptions of Best Practice.” Children and Youth Services Review 30 (2): 187–198. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.005.

- Darlington, Y., J. A. Feeney, and K. Rixon. 2005. “Interagency Collaboration between Child Protection and Mental Health Services: Practices, Attitudes and Barriers.” Child Abuse & Neglect 29 (10): 1085–1098. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.005.

- Directorate for Health/Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs. 2016. Oppsummering Og Anbefalinger Fra Arbeidet Med Helsehjelp Til Barn I Barnevernet [Summary and Reccomendations from the Work on Health Services for Children in Care]. Oslo: Barne-, ungdoms- og familiedirektoratet og Helsedirektoratet.

- González-García, C., A. Bravo, I. Arruabarrena, E. Martín, I. Santos, and J. F. Del Valle. 2017. “Emotional and Behavioral Problems of Children in Residential Care: Screening Detection and Referrals to Mental Health Services.” Children and Youth Services Review 73: 100–106. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.011.

- Greger, H. K., A. K. Myhre, S. Lydersen, and T. Jozefiak. 2015. “Previous Maltreatment and Present Mental Health in a High-risk Adolescent Population.” Child Abuse & Neglect 45: 122–134. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.003.

- Hall, P. 2005. “Interprofessional Teamwork: Professional Cultures as Barriers.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 19 (sup1): 188–196. Review of. doi:10.1080/13561820500081745.

- Hanssen-Bauer, K., Ø. Langsrud, S. Kvernmo, and S. Heyerdahl. 2010. “Clinician-rated Mental Health in Outpatient Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: Associations with Parent, Teacher and Adolescent Ratings.” Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 4 (1): 29. Review of. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-4-29.

- Hassan, E. 2006. “Recall Bias Can Be a Threat to Retrospective and Prospective Research Designs.” The Internet Journal of Epidemiology 3 (2): 339–412. Review of.

- He, A. S., C. S. Lim, G. Lecklitner, A. Olson, and D. E. Traube. 2015. “Interagency Collaboration and Identifying Mental Health Needs in Child Welfare: Findings from Los Angeles County.” Children and Youth Services Review 53: 39–43. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.013.

- Hennink, M., I. Hutter, and A. Bailey. 2020. Qualitative Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Limited.

- Heyerdahl, S., S. Kvernmo, and L. Wichstrøm. 2004. “Self-reported Behavioural/emotional Problems in Norwegian Adolescents from Multiethnic Areas.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 13 (2): 64–72. Review of. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-0359-1.

- Janssens, A., and D. Deboutte. 2009. “Screening for Psychopathology in Child Welfare: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Compared with the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA).” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 18 (11): 691–700. Review of. doi:10.1007/s00787-009-0030-y.

- Janssens, A., & Deboutte, D. (2010). “Psychopathology Among Children and Adolescents in Child Welfare: A Comparison Across Different Types of Placement in Flanders, Belgium.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 64(4): 353–359.

- Joffe, H. (2012). “Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy 1.

- Johnson, L. J., D. Zorn, B. K. Yung Tam, M. Lamontagne, and S. A. Johnson. 2003. “Stakeholders’ Views of Factors that Impact Successful Interagency Collaboration.” Exceptional Children 69 (2): 195–209. Review of. doi:10.1177/001440290306900205.

- Jozefiak, T., N. S. Kayed, T. Rimehaug, A. K. Wormdal, A. M. Brubakk, and L. Wichstrøm. 2016. “Prevalence and Comorbidity of Mental Disorders among Adolescents Living in Residential Youth Care.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 25: 33–47. Review of. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0700-x.

- Kjær, B. A. K. 2017. “Fra Profesjonelt Skjønn Til Strukturerte Maler I Barnevernundersøkelser.” Tidsskrift for Familierett, Arverett Og Barnevernrettslige Spørsmål 15 (4): 305–328. doi:10.18261/issn.0809-9553-2017-04-0.

- Kornør, H., and T. Jozefiak. 2012. “Måleegenskaper Ved Den Norske Versjonen Av Child Behavior Checklist–versjon 2-3, 4-18, 1½-5 Og 6-18 (CBCL).” PsykTestBarn 1: 3.

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2015. Det Kvalitative Forskningsintervju 3. Utgave Ed. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Lauritzen, C., S. A. Vis, K. J. S. Havnen, and S. Fossum. 2017. “Barnevernets Undersøkelsesarbeid - Evaluering Av Kvellomalen.” In Delrapport 2. Tromsø: RKBU Nord.

- Lauritzen, C., S. A. Vis, and S. Fossum. 2017. ““Samhandling Mellom Barnevern Og Psykisk Helsevern for Barn Og Unge–utfordringer Og Muligheter.” [Intersectoral Collaboration between Child Welfare Services and Mental Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Norway – Mapping Current Challenges].” Scandinavian Psychologist 4: e14. doi:10.15714/scandpsychol.4.e14.

- Lehmann, S., and N. S. Kayed. 2018. “Children Placed in Alternate Care in Norway: A Review of Mental Health Needs and Current Official Measures to Meet Them.” International Journal of Social Welfare 27 (4): 364–371. Review of. doi:10.1111/ijsw.12323.

- Martín, E., C. González-García, J. F. Del Valle, and A. Bravo. 2020. “Detection of Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Residential Child Care: Using a Multi-informant Approach.” Children and Youth Services Review 108: 104588. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104588.

- McNamara, P., and E. Neve. 2009. “Engaging Italian and Australian Social Workers in Evaluation.” International Social Work 52 (1): 22–35. Review of. doi:10.1177/0020872808097749.

- Munro, E. 2011. The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report, a Child-centred System. Vol. 8062. UK: The Stationery Office.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. 2020. “Mental Health Care in Norway for Young People.” Helsenorge.no. Accessed 21 August. https://helsenorge.no/SiteCollectionDocuments/Mental%20Health%20Care%20in%20Norway%20for%20Youth.pdf

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. USA: Sage publications.

- Pedersen, L.-M. L. 2019. “Interprofessional Collaboration in the Norwegian Welfare Context: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 1–10. Review of. doi:10.1080/13561820.2019.1693353.

- Salbach-Andrae, H., K. Lenz, and U. Lehmkuhl. 2009. “Patterns of Agreement among Parent, Teacher and Youth Ratings in a Referred Sample.” European Psychiatry 24 (5): 345–351. Review of. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.07.008.

- Schmid, M., L. Goldbeck, J. Nuetzel, and J. M. Fegert. 2008. “Prevalence of Mental Disorders among Adolescents in German Youth Welfare Institutions.” Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-2.

- Stanley, N., B. A. Penhale CQSW MSc, M. R. C. Riordan SMBBS, B. A. Barbour PhD, and L. L. B. Holden CQSW MPhil. 2003. “Working on the Interface: Identifying Professional Responses to Families with Mental Health and Child‐care Needs.” Health & Social Care in the Community 11 (3): 208–218. Review of. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00428.x.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Children Youth and Family Affairs/The Norwegian Directorate of Health. 2015. “Samarbeid Mellom Barneverntjenester Og Psykiske Helsetjenester Til Barnets Beste (Collaboration between Child Welfare Services and Mental Health Services for Best Interests of the Child)”. https://bufdir.no/bibliotek/Dokumentside/?docId=BUF00003212#:~:text=Samarbeid%20mellom%20barneverntjenester%20og%20psykiske%20helsetjenester%20er%20viktig,familier%20f%C3%A5r%20de%20tjenestene%20de%20har%20behov%20for

- Timonen-Kallio, E. 2019. ““Interprofessional Collaboration between Residential Child Care and Mental Care Practitioners: A Cross-country Study in Six European Countries.” Review Of.” European Journal of Social Work 22 (6): 947–960. doi:10.1080/13691457.2018.1441135.

- Whittaker, J. K., L. Holmes, J. F. Del Valle, F. Ainsworth, T. Andreassen, J. Anglin, C. Bellonci, D. Berridge, A. Bravo, and C. Canali. 2016. “Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Youth: A Consensus Statement of the International Work Group on Therapeutic Residential Care.” Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 33 (2): 89–106. Review of. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2016.1215755.

- Whyte, S., and A. Campbell. 2008. “The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Useful Screening Tool to Identify Mental Health Strengths and Needs in Looked after Children and Inform Care Plans at Looked after Children Reviews?.” Child Care in Practice 14 (2): 193–206. Review of. doi:10.1080/13575270701868868.