ABSTRACT

Several systematic reviews have suggested the linkages between social support and mental health or the use of mental health services in general. There is a need to develop the knowledge on different associations between social support, social work and mental health recovery, and the various features of social support. Inequality in health is a rising problem. Broader integration of social support-orientation in services and policy can play an important role in reducing health inequalities and enhance recovery. In this article we aim to scope existing literature regarding (a) the associations between social support, mental health and recovery, and (b) describe features of community mental health services that incorporate social support. Further, we discuss facilitators and barriers for social work and social support. Advanced searches were conducted in five relevant databases: Social Science Premium Collection, CINAHL, SweMed+, Idunn, and PsychInfo Ovid, and we did a qualitative synthesis of the included papers. Twenty-nine papers met the inclusion criteria in this scope and are organized into two major themes: a) Associations between mental health and social support, and b) Key features of social support-oriented community mental health services.

Introduction

This scope review maps out the literature on the association between social support and mental health by focusing on recovery from mental health problems, and the features of social support and community mental health services. The scope begins with the notion that social support plays a substantial role in attaining and maintaining good mental health, in the prevention of and recovery from mental health problems (Topor et al. Citation2011; UN Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2018) and have a potential in reducing inequalities in health (Stoltenberg Citation2015).

Social support is often conceptualized in the following categories: (a) emotional, (b) instrumental, (c) informational, and (d) appraisal (Langford et al. Citation1997; Sarason et al. Citation1987). Emotional support refers to having someone to talk to, having close relationships with family and friends, and feeling loved and cared for. Instrumental support refers to having someone to trust and count on in difficult life circumstances and dealing with the demands of daily living such as getting to appointments, shopping, cleaning, help with money matters, paying bills, and so forth (Baiden, Den Dunnen, and Fallon Citation2017; Sarason et al. Citation1987).

Several systematic reviews of the literature have suggested linkages between social support and mental health or mental health service use in general (Beauregard, Marchand, and Blanc Citation2011; Leigh-Hunt et al. Citation2017; Terry and Townley Citation2019; Tol et al. Citation2011; Wang et al. Citation2018) and in specific population groups (McDonald Citation2018; Tough, Siegrist, and Fekete Citation2017). Findings in previous studies suggest that social support, which may be provided by a variety of individuals and services, plays an important role in promoting community integration and social networks for individuals with serious mental health challenges (Salehi et al. Citation2019; Terry et al. Citation2019). There is no review in the literature that addresses the relationship between social support and mental health in the context of identifying the state of the knowledge, with a specific focus of understanding the variations of social support. Further, we found a need for a scope review providing a more comprehensive understanding in the development of social support-oriented mental health services in facilitation of mental health recovery.

Aims

This study objects to explore the role of social support in the development of, experience of, and recovery from mental health problems. The main aims of this article are to map and explore existing literature regarding (a) the associations between social support, mental health and recovery, and (b) explore the key features of community mental health services that integrate social support in practice. We also aim to address the increasing inequality in health and propose that social support-orientation plays an important role when meeting this rising problem.

Recovery and recovery capital

The recovery tradition in mental health is deeply rooted in service user movements and professionals that have emphasized psychosocial aspects of working with and recovering from severe mental health challenges (Bengt Karlsson and Borg Citation2017). This orientation marked early that it wanted to go beyond the biopsychosocial model (Davidson and Strauss Citation1995). However, it also faces extensive critique, especially considering its way of defining what recovery practice actually is, where some argue that within this tradition the attention now is directed more towards excessive individual orientation (Bengt Karlsson and Borg Citation2017; Price-Robertson, Obradovic, and Morgan Citation2017). Consequently, one can here lose focus of the very nature of recovery as relational. Nevertheless, we can say that this tradition relates to a broader range than, for example, how the psychiatric tradition works with the different layers of social support. The recovery tradition created new perspectives that unfold in the field from the scale of building recovery communities to its influence in social policy in the wholesome work to support the individual recovery process. Recovery does not necessarily imply becoming symptom free. Instead, it involves reclaiming control over one’s life and negotiating a valued and satisfying ‘place in the world’ and finding personal strategies for managing any ongoing distress experiences (Anthony Citation1993). Conceived in this way, recovery is both a personal and a social process – in which resolution of internal distress takes place alongside social reengagement in ways that may be mutually reinforcing (Jacob Citation2015; Tew Citation2013; Topor et al. Citation2011). The terms recovery and mental health recovery will be used as an understanding of this concept during this article.

Another term of importance related to social support and mental health recovery is recovery capital. Tew (Citation2013) proposes that recovery capital includes four different types: (1) economic capital (2) social and relational capital (3) identity capital and (4) personal (or mental) capital. Social support-oriented services can and should work with the recovery capital at these different levels.

Social inequalities in mental health – a Nordic paradox and global problem

Mental health services are constantly evolving and trying to incorporate that social factors are crucial when understanding and solving mental health problems. These services often work with people that lives in scarcity, e.g. poor economy and deprived living conditions. However, the current levels and types of services seem insufficient in incorporating the social perspectives in mental health care and often offers inadequate help (Cottam Citation2018; Giacco et al. Citation2017; Bengt Karlsson and Borg Citation2017; Topor et al. Citation2011).

Social inequality in health is a rising problem at a global scale (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2020) and is a significant component to include when exploring social support and mental health recovery (Sælør et al. Citation2019). Inequalities in mortality have even been rising ever since the 1960s in Norway, a country often referred to as one of the world’s most equal countries (Dahl and van der Wel Citation2016). In Norway inequalities in health are therefore addressed as a rising problem and concern (Dahl and van der Wel Citation2016; Stoltenberg Citation2015). In Nordic countries such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden there have been concrete political strategies to reduce this problem (Dahl and van der Wel Citation2016). A white paper on public health in Norway describes the problem and specifically points out social inequality in mental health as a mounting problem that requires strategies for solutions, e.g. increased social support-orientation (Ministry of Health and Care Services Citation2014-2015). Inequality in health is sometimes debated as a paradox in the Nordic welfare states, because despite social inequality (in general) in Nordic countries is lower compared to other countries on a global scale, inequalities in health are mounting (Dahl and van der Wel Citation2016). At the same time the inequality related to income is steadily increasing in Norway, and is greater than the statistics is showing, something newly reported by Statistics Norway (Aaberge, Modalsli, and Vestad Citation2020). In a (mental) health-perspective this is an argument to work with varieties of support and features of social support in a more systematic and broad matter, so that services can integrate and be inspired by social support-orientations from different practices. This comes with the assumption that increased social support, and active social policy that facilitates social support and economic equality, are important dimensions in battling increased inequality in health and facilitate mental health recovery (Sælør et al. Citation2019; Stoltenberg Citation2015)

Method

Colquhoun et al. (Citation2014) has defined a scoping review as ‘a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question, aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge’ (p. 1292). Where a strict systematic review typically focuses on well-defined questions and accurate study designs that will often be identified in advance, a scoping study tends to address broader topics that can include a greater variety of study designs (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005).

This scoping review applied the following steps in its process by drawing on Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005): (a) identifying the research aims/questions, (b) identifying relevant studies and scientific work, (c) study selection, (d) charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. We also added a broader discussion. The scope process began in February 2018 and we had an updated search January 2020. We did not register the study in Prospero, since this is a scope review without direct health-related outcomes.

The search process

The starting point was to formulate the aim of this scope review, followed by advanced search in five relevant databases, namely Social Science Premium Collection, CINAHL, SweMed+, Idunn, and PsychInfo Ovid. The rationale for the use of these databases is that they capture articles both in the English language and Nordic languages and interdisciplinary research. The search was conducted with the support of a health librarian at one of the affiliated universities. The main terms, combinations, and variations in the search strategy used in all databases were as follows: ‘Community Mental health services,’ ‘Mental health services,’ ‘Social support,’ ‘Mental health recovery,’ ‘Community mental health work,’ ‘Psychosocial interventions,’ and ‘Social Work, psychiatric.’ We included Medical Subject Headings (MESH) in some databases where it was an option to ensure a broad scope and better rigour in our search process, and we used relevant synonyms. The search was limited to the period from January 2000 to January 2020. We limited our search to the mentioned period because of the large body of literature and decided to focus on peer-reviewed articles.

Inclusion criteria applied: Full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals, studies published in English and Nordic languages, qualitative and quantitative studies, and relevant papers in the research network.

Exclusion criteria: Personal viewpoints. The full-text articles excluded with reasons consisted of articles that had poor study design or personal viewpoints that did not supplement the already elected articles.

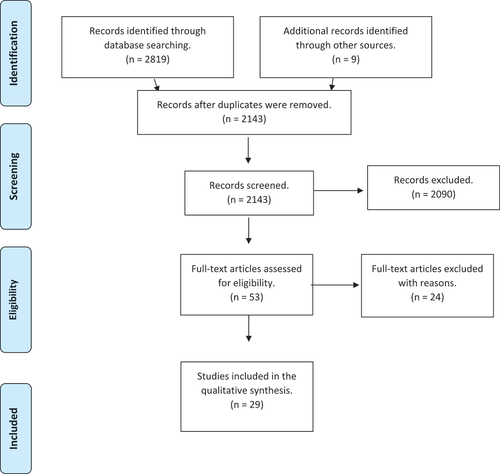

There were 2,819 hits in all five databases after limiting the focus to peer-reviewed articles. After importing all the studies to EndNote, Author 1 removed all the duplicates, and then sorted and screened out the most relevant studies for closer abstract-reading. A large number of articles identified in the search were considered inappropriate or inapplicable mostly because their foci did not fit our research aims. This resulted in a total of 53 full-text articles from the search results in the databases that were considered to align with the research aim and still ensure a good scope. The final step in the review and selection by reading the full texts was to select those articles that were relevant to the aim of this scoping review, and to exclude the ones with poor study design or personal viewpoints that did not contribute with relevant empirical material. This review process involved the construction of a classification table that presented the relevance and the quality of the study design, which all authors contributed. This resulted in a set of 29 articles as the base for the review, as shown in .

Systematizing the findings

The 29 articles were reviewed carefully for their relevance, with focus on research design. We applied the qualitative thematic synthesis to systematize the findings in these papers and to extract major themes addressing the research aims. The thematic synthesis was organized into two major topical themes: (a) association between mental health and social support, and (b) features of social support-based community mental health services. This allowed the differentiation between the literature on the complexities of the association between mental health and social support on the one hand, and the social support-oriented approaches in mental health care on the other. Of the total, 13 papers were oriented to the first topic (a) and 16 were oriented to the second topic (b).

Findings

presents information on the 29 papers that are included in this scope by chronicling the research questions or hypotheses, the study participants, the major findings, the research design, and the internal and external validity. The findings are sorted out in relation to the two foci/aims of the review and our qualitative synthesis.

Table 1. Selection and description of studies (N = 29) for the scope. almost all studies except two (Malaysia and China) were conducted in western countries.Findings sorted in to sections a) associations between mental health and social support and b) features of social support oriented services.

The articles we reviewed in our scope have various research designs, research contexts, and population samples. Of the entire selection of 29 studies, nine have a qualitative orientation, 13 have a quantitative orientation, and three are literature reviews (one explores social support and religion, the second seeks to clarify which form of social support actually uses meta-synthesis strategies, and the third maps social participation interventions in mental health work). Two papers are conceptual framework studies. One has a mixed-method evaluation design, and one a naturalistic case study design. Most studies were carried out in western countries except two (Malaysia and China). Details are presented in .

The understanding, integration, and concept of social support employed in each of the reviewed papers are varied. Twenty papers use the term social support as a keyword, while the other papers have different terms as keywords that are related to social support such as social interaction, social networks, social predictors, supported housing, peer support, and so on. Some papers clarify and define social support, while others do not. The most common way to conceptualize social support is by connecting it to the categories that are referred to in the introduction; social support is an advocative interpersonal process characterized by at least one party gaining social benefits (Finfgeld‐Connett Citation2005).

The mental health characteristics of the participants studied in this review were segregated into three main groups: (a) severe/long-term mental health problems, (b) milder/moderate mental health problems, and (c) context-specific mental health problems (for example among recent immigrants, caregivers etc.), with the dominant focus on severe long-term mental health problems.

Associations between mental health and social support

In this section, we identify two different sub-themes as the major points: (a) social support associated with mental health status (or well-being), and (b) social support in relation to the experiences of people with severe mental health problems. Both themes, although somewhat related, are different ways in which social support has an impact on mental health. The first refers to the idea that people with low social support (in terms of social network, social participation, social capital, and feelings associated with the lack of social support such as loneliness) may be more likely to experience mental health problems as social support acts as a protective element in people’s lives. The second refers to the idea that people with mental health problems can go through different paths of recovery or ‘getting well’ because they each have different levels of social resources (social support) available to them to give them the boost and support they need.

Social support, mental health status, and social support preferences

People with adequate social support are less likely to use mental health services but are more likely to get support to search for help whenever they need it, as opposed to those who have inadequate social support altogether (Andrea, Siegel, and Teo Citation2016). Social support is associated with mental health status, as low social support is found to be associated with the risk of developing mental health and/or addiction problems or the worsening of an already existing mental health problem (Baiden, Den Dunnen, and Fallon Citation2017; Stockdale et al. Citation2007). The association between mental health and social support was also evident in high-risk population groups such as among immigrants in Canada (Puyat Citation2013), or people living in socially isolated neighbourhoods (Stockdale et al. Citation2007). Being immigrants may be a risk factor for developing mental health problems with the added effect of low social support, which may be more prevalent among recent immigrants found in studies in Canada (Puyat Citation2013). This is transferable to other countries depending on the social context, culture, welfare system, and environment. The combined effect of being a recent immigrant and having low social support seems to be associated with a greater risk of developing mental health disorders (Puyat Citation2013). In comparison with individuals who have moderate levels of social support, individuals with low social support have greater odds of experiencing mental health disorders and this association appeared the strongest among recent immigrants.

Further, Baiden, Den Dunnen, and Fallon (Citation2017) found that close to one in five Canadians (19.6%) had mental healthcare needs, of which 68% had their needs fully met and 32% had unmet needs. Social support was the strongest factor associated with unmet needs.

Bjornestad et al. (Citation2017) explored the effect of friendship after the first episode of psychosis in a Norwegian context. A baseline sample of 178 individuals experiencing the first episode of psychosis were followed up for over 2 years regarding their social functioning and clinical status. The researchers longitudinally followed up on those who had recovered to those who had not. The results showed that the frequency of social interactions with friends was a significant positive predictor of clinical recovery over a period of 2 years. The study concluded that interactions with friends is a malleable factor that can be targeted for early intervention, and seems to have an overall stronger impact on recovery and functional social support effects than interactions with family.

The role of religion and spirituality seems to have received less scientific scrutiny. Smolak et al. (Citation2013) conducted a review that focused on 43 original research studies by studying people with schizophrenia and investigating the role of religion in their recovery. Of these, 12 studies were conducted in the US, 18 were conducted in other countries. Religion seems to have indirect effects by influencing people with mental health problems to seek religious or spiritual help as a form of social support (Smolak et al. Citation2013). On the other hand, people’s religious beliefs seem to influence the type of social support that they may be most willing to offer to people with mental health problems such as schizophrenia (Smolak et al. Citation2013; Wesselmann et al. Citation2015).

Social support in relation to the experiences of people with severe mental health problems

Social support affects the experiences of people with mental health problems in various ways. At the baseline, the strength and quality of the social support, the social network, and social relationships tend to be lower for people with mental health problems. People with severe mental health problems tend to have fewer social relationships than others, and are more likely to experience social exclusion (Baiden, Den Dunnen, and Fallon Citation2017; Forrester-Jones et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, the social network seems to be the most important support system that impacts the general well-being of people with mental health problems (Kogstad, Mönness, and Sörensen Citation2013). The type of social support that people with long-term mental health problems sought varied according to the types of accommodation, thus suggesting that where people live can also affect their accessibility of the social support they need (Forrester-Jones et al. Citation2012). There is a positive statistical correlation between one’s social network and well-being. While the social network component is a dominant factor, another significant factor is the ‘income situation,’ that leads to discrimination between those who are engaged in some kind of work or study and those that are not, and social networks emerge as the most important support system related to recovery (Kogstad, Mönness, and Sörensen Citation2013). Caregivers ability to give social support is an important aspect when exploring social support.

A study from China found that caregivers of people with severe depression had an increased risk of developing depression. The caregivers with higher levels of social capital had lower risk of developing depression, and this study suggest increased focus on building social network for caregivers and patients (Sun et al. Citation2019).

Both traditional social support and distal support such as establishing casual ties with community members were found to be associated with the recovery process (Townley, Miller, and Kloos Citation2013). It appears that distal support can predict both recovery and community integration after accounting for the influence of traditional social support networks (Townley, Miller, and Kloos Citation2013). Traditional social support had larger standardized beta weights and accounted for the greatest variance in both community integration and recovery. However, distal support still explained a significant amount of unique variance. Having enough traditional social support is perhaps more influential in the community integration and recovery process (Townley, Miller, and Kloos Citation2013).

As mentioned, social support in the form of interactions with friends has a solid positive impact on the recovery of people with psychosis, as was seen when they were examined longitudinally (Bjornestad et al. Citation2017), and increased social support was positively associated with the quality of life in people with schizophrenia (Munikanan et al. Citation2017). The respondents in the study conducted by Munikanan et al. (Citation2017), who had all experienced schizophrenia, reported that at higher levels of quality of life, they had all different types of social support available (Munikanan et al. Citation2017).

There are important relationships among the different types of accommodation in which people experiencing severe/long-term mental health problems live, their ages, their social networks, and the types of social support that they give and receive (Forrester-Jones et al. Citation2012). It is important to embrace this knowledge and to create services in ways that can facilitate social support, friendship, and enhance the quality of life for those experiencing severe mental health problems. This builds a bridge to the next theme.

Features of social support-based community mental health services

For this section, we extracted two sub-themes, namely (a) social support as the direct strategy within community mental health services (peer support, recovery communities, and clubhouse developments) and (b) social support through indirect strategies such as housing support, income support, etc., which end up enhancing social support (assessing the indirect routes that boost social support). There is a difference in needs among different individuals and groups, and it is important to address this difference. Some experience severe mental health problems, while some face milder or moderate mental health problems. Despite different types of circumstances and mental health problems, combating loneliness and excessive individualization of mental health problems stand out as crucial dimensions – thereby offering an alternative or crucial supplement to ‘traditional’ psychiatric treatment. The effect of social support, while also acknowledging that people experience a variety of mental health problems, seems to be much the same: it enhances recovery and the quality of life, and it is not diagnosis specific.

Social support as direct strategies

There is strong evidence to conclude that people who have long-term mental health problems have lesser social capital and social resources that can boost their social support (Webber and Fendt-Newlin Citation2017; Webber et al. Citation2015). This is an important reason for incorporating social support-oriented strategies in mental health work. A review (Webber and Fendt-Newlin Citation2017) exploring social participation interventions drew upon 19 interventions from 14 countries, 6 of which were evaluated using a randomized controlled trial. The categories of social support were grouped into individual social skills training; group skills training; supported community engagement; group-based community activities; employment interventions; and peer-support interventions. Social network gains appeared the strongest among the supported community engagement interventions, and social interventions seemed to have had a great impact on recovery (Webber and Fendt-Newlin Citation2017).

Clubhouse features are central to promoting interpersonal closeness in mental health work. Other types of mental health programmes can integrate many of the nine features that were listed by Prince et al. (Citation2018), in order to combat the social isolation that can lead to a relapse or other adverse consequences. Clubhouses promote closeness through (1) work, (2) repeated interactions among members, (3) a non-judgemental environment, (4) evening and weekend activities, (5) social skills enhancement, (6) power equalization among staff and members, (7) sharing of similar experiences, (8) flexibly structured activities, (9) and staff outreach after absence. All these features can be described as closeness factors.

Results from a longitudinal survey conducted in Norway indicated that improving social support – with a special emphasis on providing opportunities for nurturance – might provide important opportunities for increasing the sense of coherence among people with a variety of mental health problems (Langeland and Wahl Citation2009). To be helpful to others may be important for our self-esteem, sense of purpose, and well-being. The study suggests that mental health professionals should encourage service users to use their abilities to be providers of nurturance in their relationships and their social environment. Mutuality seems like a key factor in boosting the quality of the social support experienced, and the services can facilitate the quality and development of social support.

Almost all participants in a study conducted in the US lauded recovery communities as a significant contributor to positive change in various psychosocial domains (Whitley et al. Citation2008). Another study from the US explored caring for a garden, and found that gardening programmes were capable of facilitating recovery from mental health problems and the development of interpersonal relationships (Smidl, Mitchell, and Creighton Citation2017). The results suggest that building and caring for a garden facilitates recovery from mental health problems and can create a recovery community. As indicated in other studies (Prince et al. Citation2018; Webber and Fendt-Newlin Citation2017) listing social support-oriented features, this study also suggested that the connections among people that such activities create have an important impact on the recovery process. Craft activities can also be a direct strategy to connect people and to enhance recovery. Craft as an activity can facilitate stability and routines, skills and ability, and peer support (Horghagen, Fostvedt, and Alsaker Citation2014)

Peer support has an important impact on building strong relationships and facilitating recovery from mental health problems (Gidugu et al. Citation2015; B. Karlsson et al. Citation2017). Practical support, role modelling, mentoring, and providing social opportunities alongside emotional support by normalizing relationships with others with similar experiences stand out as the most critical and effective aspects of a peer-support specialist’s roles (Gidugu et al. Citation2015).

Supportive and social relations were created and shaped in a football and mental health project in England (McKeown, Roy, and Spandler Citation2015). Mental health service users with a variety of mental health problems (the majority of whom were working class men) experienced being connected with others and having a meaningful individual and collective agenda. In more transformative terms, the mix of mutual support demonstrated in the initiative and project is of growing interest in the value of more relational and collectivized models of care (McKeown, Roy, and Spandler Citation2015). It seems like collaborative football groups can act as a conduit for recovery from mental health disorders (Lamont et al. Citation2017).

A study from the Netherlands (de Jong et al. Citation2016) explored the effects of family group conferencing in public mental health contexts and found that the resilience of clients, client systems, and neighbourhoods as perceived by several respondent groups increased after the conferences. The perceived living conditions of the main participants also improved and the same applied for the quality and quantity of social support (de Jong et al. Citation2016).

Social support through indirect effect within strategies

Reducing relative poverty seems to enable people that struggle with mental health problems to regain access to and actually make use of different public and private arenas for social exchange (Ljungqvist et al. Citation2016). Help with money matters (e.g. direct money transfers) can boost social participation, social support and recovery, according to this study.

Understanding whether and how individualized housing support programmes improve community participation is important in addressing social exclusion, loneliness, stigma, and discrimination, and poor economic participation among people experiencing long-term mental health problems. The HASI Stage One evaluation (Australia) found that the role of support programmes in facilitating social and community participation can be instrumental in increasing meaningful activities among clients. This support was possible because of permanent social housing and active mental health case management (Muir et al. Citation2010). A study from the UK suggested that embracing a more comprehensive understanding of the contexts of housing and neighbourhoods can address housing problems and promote recovery from mental health problems (Kloos and Shah Citation2009). Supportive housing programmes can also be described as a broader strategy to enable access to services and support, and to maintain housing (Owczarzak et al. Citation2013).

Shifting the focus of clinicians away from deficits in the social functioning of people with psychosis to identifying assets and shared interests among them is important. This encourages social engagement and improves recovery (Webber et al. Citation2015). One can call this both a direct (workers connecting people) and indirect (workers evolving consciousness on the effects or opportunities) strategy to boost social support. Webber et al. (Citation2015) collected data from a range of social network enhancement activities in six diverse contexts in England. The exposure of a service-user to new ideas appeared to be a key element in the process of identifying opportunities for connecting people and improving social networks.

These findings ensure that there are both direct and indirect routes to boost social support, and that mental health practice should focus more on both ways and means to offer better treatment.

Discussion

In our discussion, we focus mainly on social support examined at different levels, and the need for the incorporation of a larger amount of social approaches and social work in mental health practice. We also attempt to highlight some of the barriers on the path of incorporating social support and social work in mental health services, based on the review of literature and additional knowledge gathered. We point out gaps in research and identify areas for further research.

How do we understand and examine social support?

This scope started out with an understanding of social support as a crucial element in recovery from mental health problems. As findings from section (a) demonstrate, we can find a variety of associations between mental health, recovery, and social support. The association between friendship and recovery from mental health problems, and beliefs/religion and understanding of mental health problems are especially strong. It is also found that social support is one of the most important aspects when a service-user reports having unmet needs. Overall, this section invites us to better understand that mental health work can evolve by focusing on relational and contextual approaches, something that gets more and more attention in evolving mental health services and communities (Giacco et al. Citation2017), but still seems difficult to integrate. It also enforces the understanding of social support as crucial for recovery from mental health problems and in building recovery capital.

As we can see from the findings in section (b), there are many good examples of local practices that help building supportive environments for people experiencing mental health problems. It can be initiatives in the form of clubhouses, recovery communities, football groups, peer-support initiatives, gardening programmes, etc. It seems like there is significant potential to integrate social support in mental health services in a more determined manner (McKeown, Roy, and Spandler Citation2015). Key aspects of social support-oriented services are related to both direct and indirect strategies of social support. Help with housing and economy are examples of indirect strategies that can boost social support. On the other hand, facilitating interpersonal relationships through activities is a key direct strategy in boosting social support. Creating arenas to build friendships, social capital and to facilitate social integration are crucial to the enhancement of the potential of mental health work and social support (Topor et al. Citation2011). These strategies create an opportunity for both emotional and practical social support, as well as direct and indirect social support. To enhance recovery capital at different levels, we know that psychosocial factors that facilitate social support and reintegration into society are crucial for vulnerable groups that struggle with severe mental health problems and/or substance-related disorders (Johannessen, Nordfjærn, and Geirdal Citation2019).

With this in mind, social support is often understood and conceptualized as an advocative interpersonal process characterized by at least one party gaining social benefits (Finfgeld‐Connett Citation2005). However, as the literature also demonstrates, it is equally important to enhance the quality of support as well as to enable the possibility to both receive and to give (Langeland and Wahl Citation2009).

Furthermore, we suggest that there are four levels in which social support should be examined in relation to mental health.

What reduces and what facilitates community integration?

First, what aspects or characteristics in social support are more significantly associated with mental health concerns? The lack of social support, context-specific mental health concerns, and severe mental health problems are connected, and this seems to reduce community integration and intensify both symptoms and suffering (Baiden, Den Dunnen, and Fallon Citation2017; Puyat Citation2013). These are challenges that are often much the same in the fields of addiction and substance abuse (Andvig, Bjørlykhaug, and Hummelvoll Citation2019). The quality of social support has a great impact on mental health concerns and problems. It appears that how to work more with facilitating mutual social support is a key factor (Langeland and Wahl Citation2009).

Second, the association between social support and mental health as co-existing phenomena deserves emphasis. We have a large body of knowledge that traces back to the association between the two, and it is a paradox that services do not work more in depth with peoples social life (Andvig, Bjørlykhaug, and Hummelvoll Citation2019). It is important to examine the obstacles in the path of doing so, with great detail, to work more effectively with reducing social health inequalities.

Third, the association between social support and people’s experiences of recovery capital and mental health care deserves to be examined. It appears that both the types of social support and relationships have a great impact on recovery. What kind of relationships and types of support are most important? We know that friendship has great potential in facilitating recovery from mental health problems (Bjornestad et al. Citation2017), but distal support also plays an important role (Townley, Miller, and Kloos Citation2013). How does one facilitate friendship and enforce distal ties in times of a mental health crisis? This should be examined in detail.

Fourth, social support-oriented strategies need attention in framing and implementing community mental healthcare services. The examination of services offering features that integrate social support and facilitate potential friendship, and mutual support, are a crucial area to study. It would also be of importance to explore the links between increased income/instrumental support and levels of social support and recovery even further.

Barriers in integrating features of social support in mental health

What are the most crucial barriers and why do we not work more with people’s social life in the field of mental health, when we have all this knowledge? The state of the field is perhaps a key factor in understanding why. The power structures in the field of mental health are important factors that need to be addressed. The UN has addressed the need for a revolution in mental health in the following:

“The promotion and protection of human rights in mental health is reliant upon a redistribution of power in the clinical, research and public policy settings. Decision-making power in mental health is concentrated in the hands of biomedical gatekeepers, in particular biological psychiatry backed by the pharmaceutical industry. That undermines modern principles of holistic care, governance for mental health, innovative and independent interdisciplinary research and the formulation of rights-based priorities in mental health policy.” (UN Citation2017) P. 6.

Life circumstances and socio-economic conditions have been given very little attention in the literature because the biomedical and individual models still have the greatest influence when it comes to understanding mental health (UN Citation2017). Mental health service users still experience barriers in seeking help, as well as stigma and discrimination that can often be related to structures and conditions in health care (Staiger et al. Citation2017). Social determinants of mental health need greater attention both in terms of conceptual understanding and in actual treatment (Allen, Balfour, Bell, & Marmot, Citation2014). Too much of a focus on individual faults often casts shadows on the problems in the structure; for instance, shame of seeking social assistance can be a problem (Gubrium and Lødemel Citation2014), and has been explored both in a Nordic and global context. Therefore, an important area of focus is the creation of features in which natural interpersonal relationships and support can play key roles. This, alongside an active social policy, might be even more important related to the ongoing pandemic, a situation that underlines our social interdependence (Saltzman, Hansel, and Bordnick Citation2020)

Meeting the nordic and global problems in mental health

Connected to mental health struggle there are often several social problems that needs attention. It can be difficult to enhance hope if one’s living conditions are hard (sometimes extreme) and social support-oriented features are not available. Hope is, obviously, an important dimension in recovery from mental health problems, and people struggling often depend on support from others to be their carriers of hope, and that services can see the mix of challenges in their life circumstances (Sælør et al. Citation2014; Sælør, Stian, and Klevan Citation2020). It is also difficult for caregivers to maintain good health in a system that does not provide sufficient social support. Why we see an increasing inequality in health, and especially mental health, is a crucial question.

Attempts at meeting future challenges in public mental health and mental health services need to consider the changing technological, economic, social, and political contexts (Giacco et al. Citation2017), and strategies for reducing inequalities in mental health need more contextual interventions. Some individuals and groups are more vulnerable than others when it comes to the potential of social connectedness, for instance immigrants and especially recent immigrants as showed in studies from Canada (Puyat Citation2013). The same circumstances prevail for people who experience long-term and severe mental health problems (Webber and Fendt-Newlin Citation2017). To reduce inequalities in mental health care and to improve recovery from mental health problems, ambitious social support-oriented policies are necessary to create a more holistic approach in mental health work. It would also be a mistake to understand our potential barriers for social connectedness and social support, without actually trying to understand how the structures in our time are affecting our ability to take care of each other and to combat the rising inequality at a global scale (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2020).

Conclusions

This current review has mapped and explored essential literature related to a) various associations between mental health and social support, and b) features of social support-based community mental health services. The literature suggests that the association between mental health and social support are multifarious, and that social support is crucial for the prevention of mental health problems and the maintenance of good mental health, as well as the facilitation of recovery from mental health problems in the context of both moderate and severe mental health problems. Direct strategies can be recovery-oriented communities, clubhouses that foster interpersonal relationships, and non-traditional mental health programmes such as football and gardening programmes, etc. Indirect social interventions such as help with money matters, direct financial support, and housing support, are also features that can boost social support and enhance recovery. These strategies shows even more important during crisis such as the pandemic.

We discussed why different levels of social support should be examined. The review suggests that mental health services should focus more on the various features of social support while developing services. Despite the multifarious associations, the concept of social support seems quite rigid, and it is natural to suggest that this review does not capture all the diversity in the literature because we tend to conceptualize social support in a certain manner. Nonetheless, detailed research exploring what facilitates and hinders integrating social support features in the services, the quality of social support, especially from the perspectives of both service users and service workers, is necessary.

Limitations

The potential of missing out on important studies and literature will always be a concern. We could have relied on an even larger number of databases to gain a broader perspective. The search strategy can also be a limitation, considering the fact that different search strategies can have different impacts, and we may have missed out on some important terms in our attempt to engage with a broader scope of research (e.g., cultural components, first nation people and communities). Selection bias can always occur, although author one and two (with support from a librarian) contributed and collaborated very closely in the search and selection process. This may have had an influence on the result.

Authors information

The study was conducted as a part of the first authors PhD project “Social support and Mental Health – service users, professionals and volunteers experiences with conditions that facilitates and conditions that hinders social support” at the University of South-Eastern Norway and OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University

Authors’ contribution

The first two authors designed the search with support from the mentioned librarian, and author 3 and 4 contributed with essential critical reviews and comments in the whole writing process

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the academic librarian, Anne Skjæret Stenhammer, who contributed in the process of developing search strategy, recommended relevant databases, and supported the searching process with valuable knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaberge, R., J. Modalsli, and O. Vestad. 2020. Ulikheten - Betydelig Større En Statistikken Viser. Retrieved from https: //www.ssb.no/inntekt-og-forbruk/artikler-og-publikasjoner/ulikheten-betydelig-storre-enn-statistikken-viser.

- Allen, J., R. Balfour, R. Bell, and M. Marmot. 2014. “Social Determinants of Mental Health.” International Review of Psychiatry 26(4): 392–407. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/09540261.2014.928270?needAccess=true.

- Andrea, S. B., S. A. Siegel, and A. R. Teo. 2016. “Social Support and Health Service Use in Depressed Adults: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.” General Hospital Psychiatry. 39; 73–79. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5560028/pdf/nihms894208.pdf.

- Andvig, E., K. I. Bjørlykhaug, and J. K. Hummelvoll. 2019. “Victims of Debt after Imprisonment: Experiences of Norwegians with Substance Use Challenges.” Scandinavian Psychologist 6 (e1).

- Anthony, W. 1993. “Recovery from Mental Illness: The Guiding Vision of the Mental Health Service System in the 1990s.” Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16 (4): 11. doi:10.1037/h0095655.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Baiden, P., W. Den Dunnen, and B. Fallon. 2017. “Examining the Independent Effect of Social Support on Unmet Mental Healthcare Needs among Canadians: Findings from a Population-Based Study.” Social Indicators Research 130 (3): 1229–1246. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-1224-y.

- Beauregard, N., A. Marchand, and M.-E. Blanc. 2011. “What Do We Know about the Non-work Determinants of Workers’ Mental Health? A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 439. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-439.

- Bjornestad, J., W. Velden Hegelstad, I. Joa, L. Davidson, T. K. Larsen, I. Melle, … K. Bronnick. 2017. “With a Little Help from My Friends” Social Predictors of Clinical Recovery in First-episode Psychosis.” Psychiatry Research. 255; 209–214. Retrieved fromhttps://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178116314822?via%3Dihub.

- Colquhoun, H. L., D. Levac, K. O’Brien, S. Straus, A. Tricco, L. Perrier, … D. Moher. 2014. “Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67(12): 1291–1294. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435614002108?via%3Dihub.

- Cottam, H. 2018. Radical Help: How We Can Remake the Relationships between Us and Revolutionise the Welfare State. UK: Virago Books.

- Dahl, E., and K. A. van der Wel. 2016. “Nordic Health Inequalities: Patterns, Trends, and Policies.” Chap. 3 in Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives, edited by K. E. Smith, C. Bambra, and S. E. Hill. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, L., and J. S. Strauss. 1995. “Beyond the Biopsychosocial Model: Integrating Disorder, Health, and Recovery.” Psychiatry 58 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1080/00332747.1995.11024710.

- de Jong, G., G. Schout, E. Meijer, C. L. Mulder, and T. Abma. 2016. “Enabling Social Support and Resilience: Outcomes of Family Group Conferencing in Public Mental Health Care.” European Journal of Social Work 19 (5): 731–748. doi:10.1080/13691457.2015.1081585.

- Finfgeld‐Connett, D. 2005. “Clarification of Social Support.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 37 (1): 4–9. Retrieved from https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00004.x.

- Forrester-Jones, R., J. Carpenter, P. Coolen-Schrijner, P. Cambridge, A. Tate, A. Hallam, … D. Wooff. 2012. “Good Friends are Hard to Find? The Social Networks of People with Mental Illness 12 Years after Deinstitutionalisation.” Journal of Mental Health 21 (1): 4–14. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/09638237.2011.608743?needAccess=true.

- Giacco, D., M. Amering, V. Bird, T. Craig, G. Ducci, J. Gallinat, … S. Johnson. 2017. “Scenarios for the Future of Mental Health Care: A Social Perspective.” The Lancet Psychiatry 4 (3): 257–260. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30219-X.

- Gidugu, V., E. S. Rogers, S. Harrington, M. Maru, G. Johnson, J. Cohee, and J. Hinkel. 2015. “Individual Peer Support: A Qualitative Study of Mechanisms of Its Effectiveness.” Community Mental Health Journal 51(4): 445–452. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10597-014-9801-0.pdf.

- Gubrium, E., and I. Lødemel. 2014. “‘Not Good Enough’: Social Assistance and Shaming in Norway.” Chap. 5 in The Shame of It: Global Perspectives on Anti-poverty Policies, edited by E. Gubrium, S. Pellissery, and I. Lødemel, 85–110. Vol. 5. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.i

- Horghagen, S., B. Fostvedt, and S. Alsaker. 2014. “Craft Activities in Groups at Meeting Places: Supporting Mental Health Users‘ Everyday Occupations.” Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 21(2): 145–152. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/11038128.2013.866691?needAccess=true.

- Jacob, K. S. 2015. “Recovery Model of Mental Illness: A Complementary Approach to Psychiatric Care.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 37 (2): 117. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.155605.

- Johannessen, D. A., T. Nordfjærn, and A. Ø. Geirdal. 2019. “Change in Psychosocial Factors Connected to Coping after Inpatient Treatment for Substance Use Disorder: A Systematic Review.” Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 14(1): 16. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6499970/pdf/13011_2019_Article_210.pdf.

- Karlsson, B., and M. Borg. 2017. Recovery: Tradisjoner, Fornyelser Og Praksiser. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Karlsson, B., M. Borg, E. Ogundipe, T. L. Sjåfjell, and K. I. Bjørlykhaug. 2017. “Aspects of Collaboration and Relationships between Peer Support Workers and Service Users in Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services – A Qualitative Study.” Nordic Journal of Health Research 13 (2). doi:10.7557/14.4214.

- Kloos, B., and S. Shah. 2009. “A Social Ecological Approach to Investigating Relationships between Housing and Adaptive Functioning for Persons with Serious Mental Illness.” American Journal of Community Psychology 44(3–4): 316–326. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1007/s10464-009-9277–1.

- Kogstad, R. E., E. Mönness, and T. Sörensen. 2013. “Social Networks for Mental Health Clients: Resources and Solution.” Community Mental Health Journal 49(1): 95–100. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10597-012-9491-4.pdf.

- Lamont, E., J. Harris, G. McDonald, T. Kerin, and G. L. Dickens. 2017. “Qualitative Investigation of the Role of Collaborative Football and Walking Football Groups in Mental Health Recovery.” Mental Health and Physical Activity 12: 116–123. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2017.03.003.

- Langeland, E., and A. K. Wahl. 2009. “The Impact of Social Support on Mental Health Service Users’ Sense of Coherence: A Longitudinal Panel Survey.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 46(6): 830–837. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020748909000030?via%3Dihub.

- Langford, C. P. H., J. Bowsher, J. P. Maloney, and P. P. Lillis. 1997. “Social Support: A Conceptual Analysis.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 25 (1): 95–100. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x.

- Leigh-Hunt, N., D. Bagguley, K. Bash, V. Turner, S. Turnbull, N. Valtorta, and W. Caan. 2017. “An Overview of Systematic Reviews on the Public Health Consequences of Social Isolation and Loneliness.” Public Health. 152; 157–171. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033350617302731?via%3Dihub.

- Ljungqvist, I., A. Topor, H. Forssell, I. Svensson, and L. Davidson. 2016. “Money and Mental Illness: A Study of the Relationship between Poverty and Serious Psychological Problems.” Community Mental Health Journal52(7): 842–850. Retrieved fromhttps://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10597-015-9950-9.pdf.

- McDonald, K. 2018. “Social Support and Mental Health in LGBTQ Adolescents: A Review of the Literature.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39(1): 16–29. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283?needAccess=true.

- McKeown, M., A. Roy, and H. Spandler. 2015. “‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’: Supportive Social Relations in a Football and Mental Health Project.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 24 (4): 360–369. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/inm.12122.

- Ministry of Health and Care Services. 2014–2015. Public Health Message: Mastery and Oppurtunities. Report No. 19 to the Norwegian Storting. Oslo.

- Muir, K., K. R. Fisher, D. Abello, and A. Dadich. 2010. “‘I Didn’t like Just Sittin’around All Day’: Facilitating Social and Community Participation among People with Mental Illness and High Levels of Psychiatric Disability.” Journal of Social Policy 39 (3): 375–391. doi:10.1017/S0047279410000073.

- Munikanan, T., M. Midin, T. I. M. Daud, R. A. Rahim, A. K. A. Bakar, N. R. N. Jaafar, … N. Baharuddin. 2017. “Association of Social Support and Quality of Life among People with Schizophrenia Receiving Community Psychiatric Service: A Cross-sectional Study.” Comprehensive Psychiatry. 75; 94–102. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010440X16305132?via%3Dihub.

- Owczarzak, J., J. Dickson-Gomez, M. Convey, and M. Weeks. 2013. “What Is “Support” in Supportive Housing: Client and Service Providers’ Perspectives.” Human Organization 72(3): 254. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4251799/pdf/nihms602538.pdf.

- Price-Robertson, R., A. Obradovic, and B. Morgan. 2017. “Relational Recovery: Beyond Individualism in the Recovery Approach.” Advances in Mental Health 15 (2): 108–120. doi:10.1080/18387357.2016.1243014.

- Prince, J. D., O. Mora, J. Ansbrow, A. Benedict, J. DiCostanzo, and A. D. Schonebaum. 2018. “Nine Ways that Clubhouses Foster Interpersonal Connection for Persons with Severe Mental Illness: Lessons for Other Types of Programs.” Social Work in Mental Health 16 (3): 321–336. doi:10.1080/15332985.2017.1395781.

- Puyat, J. H. 2013. “Is the Influence of Social Support on Mental Health the Same for Immigrants and Non-immigrants?” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 15(3): 598–605. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10903-012-9658-7.pdf.

- Sælør, K. T., B. Stian, and T. Klevan. 2020. “Big Words and Small Things.” Journal of Recovery in Mental Health 3 (1): 23–38.

- Sælør, K. T., K. I. Bjørlykhaug, R. M. Bank, and T. Johnson. 2019. “Møter I Mørket.” Tidsskrift for Velferdsforskning 22 (2): 110–125. doi:10.18261/.2464-3076-2019-02-02.

- Sælør, K. T., O. Ness, H. Holgersen, and L. Davidson. 2014. “Hope and Recovery: A Scoping Review.” Advances in Dual Diagnosis 7 (2): 63–72. doi:10.1108/ADD-10-2013-0024.

- Salehi, A., C. Ehrlich, E. Kendall, and A. Sav. 2019. “Bonding and Bridging Social Capital in the Recovery of Severe Mental Illness: A Synthesis of Qualitative Research.” Journal of Mental Health 28 (3): 331–339. doi:10.1080/09638237.2018.1466033.

- Saltzman, L. Y., T. C. Hansel, and P. S. Bordnick. 2020. Loneliness, Isolation, and Social Support Factors in post-COVID-19 Mental Health.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12 (1): 55–57.

- Sarason, B. R., E. N. Shearin, G. R. Pierce, and I. G. Sarason. 1987. “Interrelations of Social Support Measures: Theoretical and Practical Implications.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52 (4): 813.

- Smidl, S., D. M. Mitchell, and C. L. Creighton. 2017. “Outcomes of a Therapeutic Gardening Program in a Mental Health Recovery Center.” Occupational Therapy in Mental Health 33 (4): 374–385. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2017.1314207.

- Smolak, A., R. Gearing, D. Alonzo, S. Baldwin, S. Harmon, and K. McHugh. 2013. “Social Support and Religion: Mental Health Service Use and Treatment of Schizophrenia.” Community Mental Health Journal 49(4): 444–450. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs10597-012-9536-8.pdf.

- Staiger, T., T. Waldmann, N. Rüsch, and S. Krumm. 2017. “Barriers and Facilitators of Help-seeking among Unemployed Persons with Mental Health Problems: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Health Services Research 17(1): 39. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5240360/pdf/12913_2017_Article_1997.pdf.

- Stockdale, S. E., K. B. Wells, L. Tang, T. R. Belin, L. Zhang, and C. D. Sherbourne. 2007. “The Importance of Social Context: Neighborhood Stressors, Stress-buffering Mechanisms, and Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Disorders.” Social Science & Medicine 65 (9): 1867–1881. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.045.

- Stoltenberg, C. 2015. “Folkehelserapporten 2014.” Helsetilstanden I Norge. 8280826351; Retrieved fromhttps://www.fhi.no/publ/2014/folkehelserapporten-2014-helsetilst/

- Sun, X., J. Ge, H. Meng, Z. Chen, and D. Liu. 2019. “The Influence of Social Support and Care Burden on Depression among Caregivers of Patients with Severe Mental Illness in Rural Areas of Sichuan, China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (11): 1961. doi:10.3390/ijerph16111961.

- Terry, R., and G. Townley. 2019. “Exploring the Role of Social Support in Promoting Community Integration: An Integrated Literature Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 64 (3–4): 509–527. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12336.

- Terry, R., G. Townley, E. Brusilovskiy, and M. S. Salzer. 2019. “The Influence of Sense of Community on the Relationship between Community Participation and Mental Health for Individuals with Serious Mental Illnesses.” Journal of Community Psychology 47(1): 163–175. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/jcop.22115.

- Tew, J. 2013. “Recovery Capital: What Enables a Sustainable Recovery from Mental Health Difficulties?” European Journal of Social Work 16 (3): 360–374. doi:10.1080/13691457.2012.687713.

- Tol, W. A., C. Barbui, A. Galappatti, D. Silove, T. S. Betancourt, R. Souza, … M. Van Ommeren. 2011. “Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Humanitarian Settings: Linking Practice and Research.” The Lancet 378(9802): 1581–1591. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3985411/pdf/nihms-568164.pdf.

- Topor, A., M. Borg, S. Di Girolamo, and L. Davidson. 2011. “Not Just an Individual Journey: Social Aspects of Recovery.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 57 (1): 90–99. doi:10.1177/0020764009345062.

- Tough, H., J. Siegrist, and C. Fekete. 2017. “Social Relationships, Mental Health and Wellbeing in Physical Disability: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 17(1): 414. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5422915/pdf/12889_2017_Article_4308.pdf.

- Townley, G., H. Miller, and B. Kloos. 2013. “A Little Goes A Long Way: The Impact of Distal Social Support on Community Integration and Recovery of Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities.” American Journal of Community Psychology 52(1–2): 84–96. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1007/s10464-013-9578–2.

- UN. 2017. Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health. In: Retrieved from the United Nations Human Rights Office.

- UN. 2020. Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health: Report of the Special Rapporteur, C44/48. Geneva: United Nations, General Assembly HR.

- Wang, J., F. Mann, B. Lloyd-Evans, R. Ma, and S. Johnson. 2018. “Associations between Loneliness and Perceived Social Support and Outcomes of Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review.” BMC Psychiatry 18(1): 156. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5975705/pdf/12888_2018_Article_1736.pdf.

- Webber, M., H. Reidy, D. Ansari, M. Stevens, and D. Morris. 2015. “Enhancing Social Networks: A Qualitative Study of Health and Social Care Practice in UK Mental Health Services.” Health & Social Care in the Community 23 (2): 180–189. doi:10.1111/hsc.12135.

- Webber, M., and M. Fendt-Newlin. 2017. “A Review of Social Participation Interventions for People with Mental Health Problems.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52(4): 369–380. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5380688/pdf/127_2017_Article_1372.pdf.

- Wesselmann, E., M. Day, W. Graziano, and E. Doherty. 2015. “Religious Beliefs about Mental Illness Influence Social Support Preferences.” Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 43(3): 165–174.

- Whitley, R., M. Harris, R. D. Fallot, and R. W. Berley. 2008. “The Active Ingredients of Intentional Recovery Communities: Focus Group Evaluation.” Journal of Mental Health 17 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1080/09638230701498424.

- Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2020. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress. restore sanity and improve everyone’s well-being: Penguin Books.