ABSTRACT

This study aimed to compare the content of the Norwegian Kvello AF for child welfare investigations with similar frameworks from Sweden (BBIC) and Denmark (ICS). The comparison was based on detailed descriptions of each framework, retrieved from authorized websites, textbooks, manuals, course material, and, for the Kvello AF, also personal communication with the author. An ecological triangle model similar to the British AF was chosen as a guideline for the comparison, as all three frameworks referred to bio-ecological developmental theory. The content of the frameworks was thus compared along dimensions and categories related to 1) the child’s needs and development, 2) the parents’ capacity, and 3) environmental factors. The main finding was that the Kvello AF included many of the same elements for gathering information as the other frameworks, but there were some important differences. The Kvello AF seemed to have a narrower perspective on the children’s needs and welfare than the other frameworks, implying a stronger focus on the child–parent interaction and a less focus on environmental factors and the child’s functioning outside the family.

Introduction

The Child Welfare Services are quite often being criticized for either intervening too early or too strongly in less serious cases or for intervening too late or too weak in cases that are more serious. This critique reflects some of the main challenges in child welfare decision-making, where it is impossible to be quite sure, whether the decision is based on sufficient information or if it is the best decision for the child and/or the parents (Backe-Hansen Citation2004; Fluke et al. Citation2014; Kojan and Christiansen Citation2016). Several recent reports in Norway have documented shortcomings and unwanted variation in the decision-making processes, related to the initial assessments of notifications (Lurie Citation2015) and the further investigation of the cases (Vis et al. Citation2014). Several inspections by the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision (Helsetilsynet Citation2012, Citation2017) and the Office of the Auditor General of Norway (Riksrevisjonen Citation2015) have addressed other shortcomings. The critique focused on two main findings; (i) the information gathering was carried out unsystematically, and (ii) the child was rarely spoken to during the investigation. The inspections concluded that this had led to instances where notifications about serious concerns of abuse or neglect had not been assessed properly and that cases had been prematurely closed.

Many countries in different parts of the world have implemented national assessment

frameworks or some kind of standardized templates for gathering necessary and important

information about a child’s needs and the situation in order to increase the quality of decision-making in the child welfare services. In Norway and many other countries, there has been an ongoing debate about the standardization of practices within child welfare services. According to Ulset, Almklov, and Røyrvik (Citation2017) several child welfare workers have critical objections to assessment frameworks. The objections are commonly related to professional discretion or to the fear that the frameworks rely too much on templates and checklists. Another objection that has been raised is a concern that the approach to children and families becomes more mechanical and problem-oriented, which can cause child welfare work to become more superficial (Ulset, Almklov, and Røyrvik Citation2017). However, a recent literature review concluded that the use of assessment frameworks in Great Britain (AF), Sweden (BBIC), and Denmark (ICS) contributed to more thorough assessments, in that more aspects connected to the child’s

situation and the parents’ care capacity were documented (Vis, Lauritzen, and Fossum Citation2016). The same review noted that British studies had demonstrated that the use of the assessment framework led to improved investigations of environmental factors. On the other hand, the use of assessment frameworks was not reported as leading to better decisions. Hence, it is important not to limit the discussion to a pro or con debate about assessment frameworks. In spite of some obvious advantages found in the referred literature review, a standardized framework may also lead to different cases being assessed equally, which is not necessarily a benefit. A framework for assessment in child welfare services must therefore be flexible. Optimally, such a framework should provide structure for the investigation process, but not compromise the possibility for professional judgement and discretion (Samsonsen Citation2016).

Unlike many other countries, Norway has not yet implemented a national or common assessment framework for child welfare investigations (Samsonsen Citation2016). A survey among managers of Norwegian child welfare services (Vis et al. Citation2014) found that approximately one-fifth of the services did not use any framework for child welfare investigations, approximately one third used locally developed frameworks and more than half of the services used a privately developed framework called the Kvello assessment framework (Kvello AF). The Kvello AF was introduced in 2007 (Kvello Citation2007) and was revised in 2015 (Kvello Citation2015).

Against the background of the reports mentioned above, and with the general aim to increase the quality of decision-making in the child welfare services, the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs commissioned an extensive research project, including one sub-study aimed at evaluating the Kvello AF. The Directorate especially wanted a comparison between the Kvello AF and other international assessment frameworks, for which the frameworks in Sweden (BBIC) and Denmark (ICS) were chosen. The aim of the study was to compare the contents of the Kvello AF with the BBIC and the ICS and to discuss how the different frameworks attended to important aspects of children’s needs and welfare.

The article will start by elaborating on the theoretical assumptions and perspectives used in the three frameworks. We will summarize the core elements of the Kvello AF, the BBIC, and the ICS, focusing on their dimensions and areas for information gathering. Based on these descriptions we will carry out a systematic comparison of the areas for information gathering in the different frameworks, focusing on similarities and differences. Finally, we will discuss how the frameworks attend to important aspects of children’s needs and welfare.

Method

The descriptions of the assessment frameworks are based on documents available from authorized websites, textbooks, manuals, course material, and for the Kvello AF, information also obtained through personal communication with the author (). As all three frameworks refer to bio-ecological developmental theory, an ecological triangle model like the British AF (United Kingdom Department of Health Citation2000) was chosen as a guideline for the comparison. The content of the frameworks was thus compared along dimensions and categories related to 1) the child’s needs and development, 2) the parents’ capacity, and 3) environmental factors. The more concrete categories were chosen to include core information areas from all three frameworks. One researcher from Denmark and one from Sweden, who had knowledge of the respective frameworks, and two impartial Norwegian researchers and the owner of the Kvello AF framework reviewed our descriptions.

Table 1. Overview of material and documentation that was used for comparison.

Theoretical perspectives

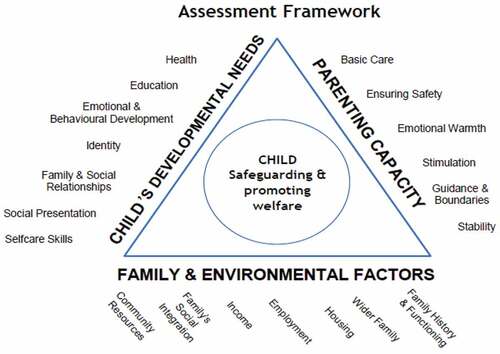

As mentioned above, all three frameworks are based on ecological perspectives and theories of children’s needs and development, and they all refer to the bio-ecological developmental model of Uri Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation2005). In brief, Bronfenbrenner’s model describes five interacting systems that have an impact on a child’s life and wellbeing. The microsystem involves the child’s family, friends, neighbours, etc.; the mesosystem involves the contact between different microsystems; the exosystem, which the child does not have direct contact with, such as their parents’ jobs, resources in the community, etc.; and the macrosystem, which refers to society as a whole with its values, norms, cultures, laws, and so on. Another system, the chronosystem, was added to the model in later versions, and involves the importance of the time dimension in understanding developmental processes. This includes both the child’s experiences and the parents’ childhood experiences. When transferred to an assessment framework, the bio-ecological perspective is often illustrated as a triangle model, where the child’s development can be seen as the result/synthesis of a continuous interplay between factors related to the child itself, the parents’ capacity to care, and family and environmental conditions. The British assessment framework is shown as a , as an example of this triangular model (United Kingdom Department of Health Citation2000).

The Kvello AF

The Norwegian Kvello AF totally consists of 10 separate dimensions, including 16 successive sections, with integrated text boxes for user guidance. This means that unlike the BBIC/ICS frameworks, the Kvello AF is not organized as a triangle model. The framework is incorporated in the Familia journal system, which is used for the electronic record-keeping of client data (an earlier version is integrated into the Acos journal system). The current description will focus on the dimensions for information gathering and is based on the user guidelines integrated with each section, and sections from the textbook Children at risk (Kvello Citation2015). It must be emphasized that dimensions related to interventions and measures are not included in this article. The relevant dimensions for information gathering in the Kvello AF are 1) Overview/background information, 2) The child, 3) The parents, 4) Interaction, and 5) Family relationships. Each of the dimensions is divided into several main areas and sub-categories, which are described in .

Table 2. Dimensions and main areas in the Kvello AF.

Relevant information on the children’s development is divided into three age groups in the Kvello AF, 0–3 years, 4–12 years, and 12–23 years (in Norway children can get assistance from the Child Welfare Services until the age of 24), with more specific lists of questions related to each. Different approaches and instruments for information gathering are suggested. A list of 32 risk factors and 10 protective factors based on evidence of having an impact on children’s development is also attached to the assessment framework. The factors should be ticked off if they are relevant, and preferably this should be done together with the family. Specific guidelines are listed for assessing ‘welfare cases’ versus ‘abuse and neglect cases’. The framework also includes a scoring system related to each area of information as a helpful tool in assessing the seriousness of a child’s situation.

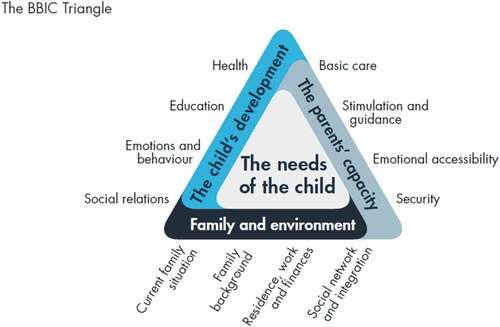

The BBIC triangle

The Swedish assessment framework, ‘The BBIC triangle’, was developed in the late 1990s, and implemented from 2006 onwards. The BBIC is based on the British AF (United Kingdom Department of Health Citation2000) but has been adapted to suit Swedish legislation and practice. The BBIC consists not only of an assessment framework for information gathering, but a complete model for investigation, planning and following up children and families in the child welfare services. The model has been revised and modified several times, most recently in 2015, on which the current description is based (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2015a). Today all of the 290 municipalities are holding a licence to use the BBIC framework, however using the system is not mandatory. We will not present the whole model in this article however but focus on the elements of the assessment framework used for information gathering.

The framework (see ) illustrates that a child’s needs can be understood as an interplay between the child’s development, the parents’ capacity and family and environment factors. The needs of the child are placed at the centre, and the three sides/dimensions are the focuses for further investigation. The dimensions are operationalized into four main areas, which are further divided into sub-areas (in total 37). Each of the sub-areas is supplied with information on important risk or protective factors connected to the child’s development and lists of helpful questions for the information gathering and the follow-up.

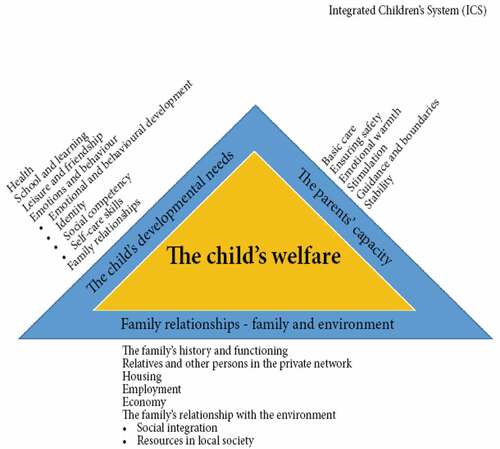

The ICS triangle

The Danish assessment framework ‘Integrated Children’s System’ (ICS) was also developed from the British AF, with a licence for use in Denmark. The implementation of the framework started with six pilot municipalities in 2007 and was integrated into an electronic IT system (DUBU digitalizing children and youth at risk) in 2011. In 2019 a great majority of the Danish municipalities were using the ICS framework, however big municipalities like Copenhagen and Aarhus, have opted not to use it. We do not know the reason for this or what systems the rest of the municipalities are using, but it is important to note that the framework is not mandatory to use, but rather recommended by the authorities. The current description of ICS is based on the version of the framework used in 2017 (Socialstyrelsen Citation2014).

A revised and simplified version of the ICS framework, together with a new version of DUBU, was implemented from 2018/2019. The revision of the ICS mainly applied to the labelling and the structure of main and sub-topics in the model, while the underlying supporting material remained the same. We, therefore, consider the conclusions with respect to differences in the content between the Nordic models to remain valid also for the revised Danish ICS framework.

shows that the ICS is much like the Swedish framework, but with slightly different wordings and in the number of main/sub-areas. For example, the centre of the triangle is called ‘the child’s welfare’ in the Danish framework. The three sides, which in ICS are called ‘domains’, focus on 1) the child’s developmental needs, 2) the parents’ competency, and 3) family relationships – family and environment. The domains are operationalized into 17 dimensions and further supplied by six main areas. It should be noted that an additional 15 sub-areas are described in the textbook, but not illustrated in the framework.

The revision of the ICS in 2014 included an extensive research-based overview of risk and protective factors, for use in assessments in a child welfare investigation. The factors are divided into eight age groups and focus on the three domains of the triangle. For example, 116 factors are listed as relevant for the age group 6–9 years, based on the child’s developmental needs. Seventy-two factors are linked to the parents’ competency domain and 57 factors are linked to the family and environment domain. The factors are formulated as statements, which act as guidance for child welfare workers when assessing a child’s situation.

Comparing the content of the Kvello AF with BBIC and ICS

The focus for comparing the Kvello AF with the Swedish and the Danish frameworks is the categories and areas/sub-areas for information gathering. The Kvello AF has a different structure and composition to those of the other frameworks, which has caused some challenges in the comparison. We have approached this issue by setting up a revised model, based on the categories from BBIC and ICS, and then distributed the categories of the Kvello AF in these. The overall dimensions and categories of the revised triangle model are presented in , :

Table 3. The revised triangle model for comparing the three Nordic frameworks.

Table 4. Comparison of categories and sub-areas on the child’s development.

In a further comparison of the frameworks, we will explore the three sides of the triangle one at a time, together with the respective categories and areas/sub-areas included in the different frameworks.

Comparing information on the ‘Child’s development’

The ‘Child’s development’ dimension consists of the following categories: physical and mental health, school and learning, emotions and behaviour and social relationships (). Relevant categories and areas/sub-areas for the Kvello AF are chosen from the dimensions of ‘the Child’, ‘Interaction’ and ‘Family relations’.

In the ‘Health’ category, all frameworks include detailed information about a child’s mental and physical health conditions, history and development. BBIC and ICS also describe the child’s use of health services, underlining the importance of regular contact with preventive services, such as following up health and dentist checks, and contact with health services for special needs. The Kvello AF also includes a specific category for ‘the child’s perspectives and wishes’. This category is not specified in BBIC/ICS. However, there is an expectation that including the child’s perspective should be an underlying principle in all parts of the assessment, i.e. also with respect to parents’ capacity and family and environmental conditions.

The ‘School and learning’ category includes much of the same information for BBIC and ICS. The Kvello AF does not, however, have a ‘school and learning’ section. Some of the information that is gathered in BBIC and ICS, i.e. the child’s functioning, in general, is covered in a different section of the Kvello AF, but the child’s functioning specifically in a school or kindergarten setting is lacking.

All frameworks emphasize gathering information on the ‘Emotions and behaviour’ category. In the Kvello AF, several sub-areas from the general category of competence, functioning and adaptability are relevant. The Kvello AF also emphasizes the interaction between the child and parents as a main dimension for the investigation and the child’s emotional involvement with their parents as a central area for information gathering. Interaction is not a focus area in BBIC/ICS, but ICS includes an attachment, which is a related topic.

The ‘Social relationships’ category is included in all frameworks, but with certain differences in specifications. While BBIC and ICS describe several types of relationships inside and outside the family and related to adults and children, the Kvello AF has a more narrow focus on different aspects of the interaction within the family. All frameworks include information on the child’s leisure activities.

Summing up the comparison: Compared to BBIS/ICS, the Kvello AF seems to be less focused on preventive health services and following up children via regular health controls, less focused on the school as an arena for children’s development, functioning and wellbeing, more focused on the interaction between children and parents, and less focused on children’s social relationships outside the family. Kvello AF also has a specific category for gathering information about children’s perspectives and wishes.

Comparing information on the ‘Parents’ capacity’

The ‘Parents’ capacity’ dimension consists of the following categories: ‘basic care and everyday routines’, ‘stimulation, guidance and boundaries’, ‘emotional accessibility and ability to understand the child’ and ‘ensuring safety and the ability to protect the child’. Relevant categories and areas/sub-areas in the Kvello AF are selected from the ‘Parents’, ‘Interaction’ and ‘Family relations’ dimensions (see ).

Table 5. Comparison of categories and sub-areas on the parents’ capacity.

The ‘Basic care and everyday routines’ category contains much of the same information for all frameworks. BBIC/ICS emphasizes basic care issues, such as nutrition, sleep, healthcare hygiene, clothing, etc., while this is not a specific topic in the Kvello AF. All frameworks point out the importance of the child’s role and responsibility in the family but in somewhat different ways. BBIC/ICS stress stimulation of the child to manage/cope with age-relevant issues, while the Kvello AF has a stronger focus on detecting whether the child has a parental role in the family. All frameworks describe ‘Stimulation, guidance and boundaries’ as central parent competencies. The Kvello AF describes these issues as part of the child–parent interaction, while BBIS/ICS does not describe interaction as a specific area for gathering information.

When it comes to ‘Emotional accessibility and understanding the child’, the Kvello AF underlines the importance of the parents’ sensitivity and ability to reflect upon the parent role (mentalization). The key methods for exploring these issues are studying the interaction between the child and the parents and interviewing the parents using recommended instruments. BBIC and ICS describe this category somewhat differently, by focusing on the parents’ ability to meet the child with warmth and regulating emotions. The ‘Ensuring safety’ category contains approximately the same information for all frameworks. BBIC and ICS seem to list sub-areas in a more specific way than the Kvello AF, while the Kvello AF has added information gathering on potential criminal/illegal conditions within the family.

In summary, there are small differences in this dimension, but the Kvello AF has less emphasis on basic care issues in the child’s everyday life. On the other hand, mentalization and child–parent interaction are emphasized in the Kvello AF but are not explicitly part of the BBIC and ICS frameworks.

Comparing information on ‘Family and environment’

The ‘Family and environment’ dimension consists of the following categories: ‘current family situation and parental problems’, ‘family history and functioning’, ‘housing, employment and economy’, and ‘the family’s social network and relationships’ (see ). The relevant categories and areas/sub-areas in the Kvello AF are mainly selected from the dimensions of ‘Background’, ‘the Parents’ and ‘Family relations’.

Table 6. Comparison of categories and sub-areas on family and environment.

In the ‘Current family situation and parental problems’ category, all the frameworks describe the family composition and/or persons involved in the investigation, and the parents’ health and problems/behaviour. BBIC also includes siblings’ health and behaviour, which is not stressed in the other frameworks. The ‘Family’s history and functioning’ are described in all frameworks, focusing on the parents’ childhood experiences. ‘Housing, employment and economy’ are described in BBIC/ICS, while the Kvello AF does not mention employment as a specific area for information gathering. Information on economics however will usually include employment. The ‘Family’s social network and relationships’ are also included in all frameworks, but it is important to note that the Kvello AF does not focus on the family’s social network and integration into local society as specific areas for information gathering, but rather as part of the parents’ functioning.

Summing up: The three frameworks cover much of the same information for all categories, however, the Kvello AF does not include a specific section for gathering information on the family’s social network and relationships outside the family.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the content of the Norwegian Kvello AF for child welfare investigations with similar frameworks from Sweden (BBIC) and Denmark (ICS) and to discuss how the different frameworks addressed important aspects of children’s needs and welfare. This perspective was chosen as a foundation for our discussion below as a bio-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner Citation2005) is a recommended and recognized way of understanding a child’s development and needs (Vis, Lauritzen, and Fossum Citation2016), and because all three frameworks refer to its principles. To structure the discussion, we have used the triangle model, consisting of the three dimensions; the ‘Child’s development’, the ‘Parents’ capacity’ and the ‘Family and environment’.

A bio-ecological perspective on a child’s needs and welfare implies that different aspects of the child’s life have to be considered. The triangle model represents a framework or guidance to ensure that information related to the child, the parents, and the family and environment will be collected, which can be seen as a basis for further assessments and considerations. It is not the specific aspects or factors that are important for the child’s development and wellbeing, however, but the interactive and reciprocal processes between them. In general terms, one can say that BBIC/ICS addresses the three core areas of information on a child’s life by using the triangle model, while the Kvello AF is more focused on the two areas concerning the child and the interaction between the child and the parents. These differences were described in the more detailed comparison between the frameworks and showed that the Kvello AF seems to have a more narrow perspective than the other frameworks in several ways.

The overall findings indicated that the Kvello AF, the BBIC, and the ICS frameworks contain many of the same sub-areas for information gathering. This is true for all three main dimensions, although there are several nuances and differences in the detail in which the information areas are formulated and what concepts are being used. The differences can be difficult to interpret, however, because different concepts might have nearly the same meaning. An example is the meaning of the general concept ‘social relationship’ compared with more specific concepts, such as ‘relationship to family members’, ‘relationship to parents and siblings’, relationship to adults and children outside the family”, etc.. Theoretically, ‘social relationship’ can include all the sub-areas mentioned above. This means that it is not necessarily valid to compare the more specific concepts used in the frameworks. In addition, all three frameworks include a set of more concrete guidelines and user manuals, which further elaborate many of the categories.

It, therefore, seems reasonable to focus on the structure and the main dimensions of the frameworks to point out the most distinct differences between them. As we have already noted, the Kvello AF has a very different structure compared to the BBIC/ICS. These consist of slightly different triangle models, which include the three core dimensions of a bio-ecological model, while the Kvello AF consists of another set of dimensions, which differs from the triangle model in several ways. By accepting that the core dimensions of the triangle models meet the basic criteria of a bio-ecological perspective, the question then is to what extent does the Kvello AF meet these criteria? In brief, the Kvello AF focuses on the child, the parents, the child–parent interaction and family relations. The most distinct differences from the triangle models are the lack of focus on environmental factors and the specific focus on interactional factors within the family. The importance of interaction is in line with a bio-ecological perspective, however, and narrowing the interaction to the child–parent relationship might well result in a reduced focus on the child’s life and interaction outside the family.

Information related to the child’s development has shown that compared to the BBIC/ICS, the Kvello AF has less focus on preventive health services and on the school as an arena for development, functioning and wellbeing. Relationships outside the family are also less in focus. From a bio-ecological perspective, this may indicate that important areas of the child’s health and everyday life might be downplayed or overseen. Considering the child’s perspective, a more specific requirement to describe the child’s views, such as in the Kvello framework may increase the likelihood that there is a conversation with the child where this is part of the agenda. However, there is no guarantee that this translates into a greater emphasis on the child’s perspectives and wishes throughout the assessment.

Information related to the parents’ capacity indicated the same direction, with less emphasis on basic care issues and everyday routines. On the other hand, focusing on parents’ mentalization and child–parent interaction is important in understanding the developmental processes, which are less focused on BBIC/ICS. As mentioned before, the Kvello AF also places less focus on environmental factors, such as the family’s social network and integration into local society, which may indicate a reduced perspective on a child’s life and wellbeing.On a final note, we should add that how and when differences in assessment frameworks translate into different social work practices in the Scandinavian countries, is an interesting topic that we cannot answer in this study. There are surely many other factors, such as differences in legislation, organization of services, the level and content of social workers education, differences in demographical characteristics and thresholds for intervention that also play a part in this.

Conclusion

The comparison of the Kvello AF with the BBIC and the ICS has revealed in several ways that the Kvello AF seems to have a narrower perspective on children’s needs and welfare than the other models. The interactive family perspective is strong, while a more holistic ecological perspective is less visible. It is necessary to gather information on different levels and arenas, inside and outside the family, everyday life and specific life events, as well as on resources and deficiencies, in order to attend to important dimensions and processes of a child’s life and development. Norway, Sweden and Denmark have chosen different paths towards employing a more structured framework for child protection assessments. Sweden and Denmark have more comprehensive frameworks compared to Norway. In Sweden, there seems to be a more universal implementation, where all municipalities now hold a licence to use BBIC, compared to Denmark where the two major cities have opted out of ICS and to Norway where implementation and use of the Kvello AF are rather coincidental.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Backe-Hansen, E. 2004. God Nok Omsorg. Riktige Beslutninger I Barnevernet (Good Enough Care. Right Decisions in the Child Welfare Services). Oslo: Kommuneforlaget.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks: CA: SAGE.

- Fluke, J. D., D. J. Baumann, L. I. Dagleish, and H. D. Kern. 2014. “Decisions to Protect Children: A Decision Making Ecology.” In Handbook on Child Maltreatment, edited by J. E. Korbin and R. D. Krugman, 463–476. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Helsetilsynet. 2012. “Oppsummering av landsomfattende tilsyn i 2011 med kommunalt barnevern – undersøkelse og evaluering. [Summary of National Supervision of Municipal Child Protection Services – Investigations and Evaluations].” Report. Oslo: Helsetilsynet (The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision).

- Helsetilsynet. 2017. “Bekymring i skuffen – oppsummering av landsomfattende tilsyn i 2015 og 2016 med barnevernets arbeid med meldinger og tilbakemelding til den som har meldt [Concerns in the File Drawer – Summary of National Supervision in 2015 and 2016 regarding Child Protection Services Handling of Referrals and Responses to the Referrer.].” Report. Oslo: Helsetilsynet (The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision).

- https://socialstyrelsen.dk/tvaergaende-omrader/sagsbehandling-born-og-unge/ics/materialer-og-redskaber.

- https://www.acos.no

- https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/stod-i-arbetet/barn-och-unga/barn-och-unga-i-socialtjansten/barns-behov-i-centrum/material/.

- https://www.visma.no

- Kojan, B. H., and Ø. Christiansen, Eds. 2016. Beslutninger I Barnevernet (Child Welfare Decision-making). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kvello, Ø. 2007. Utredning av atferdsvansker, omsorgssvikt og mishandling [Assessment of Behavioural Problems, Child Abuse and Neglect]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Kvello, Ø. 2010. Barn i risiko [Children at Risk]. 1 ed. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Kvello, Ø. 2015. Barn i risiko [Children at Risk]. 2 ed. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Lurie, J. 2015. “Barnevernets arbeid med bekymringsmeldinger i trøndelag [The Child Welfare Services Work with Incoming Reports in Trøndelag].” Report. Trondheim: NTNU, Regionalt kunnskapssenter for barn og unge - Psykisk helse og barnevern.

- Oldrup & Høyen-Sørensen. 2014. “De aldersoppdelte fokusområder i ICS – kvalifisering afden socialfaglige metode [The Age Specific Focus Areas in ICS – Methods and Documentation].”

- Riksrevisjonen. 2015. “Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av saksbehandling i fylkesnemnda for barnevern og sosiale saker [The Office of the Auditor General of Norway: Inspection on Case Proceedings in the County Board for Child Welfare and Social Services]. (Dokument 3:10).” Report. Oslo: Office of the Auditor General of Norway.

- Samsonsen, V. 2016. “Assessment in Child Protection; A Comparative Study Norway – England.” PhD Thesis, University of Stavanger, Faculty of Social Science.

- Socialstyrelsen. 2011. Integrated Children’s System (ICS) – Afrapportering av begrebsprosjekt. (Report from the terms and definitions project).

- Socialstyrelsen. 2014. Barnets velfærd i centrum – ICS håndbog. [Child Welfare in Focus – ICS Handbook]. Odense: Socialstyrelsen.

- Socialstyrelsen. 2015a. Grundbok i BBIC. Barns behov i centrum. [BBIC Fundamentals. Children’s Needs in Focus]. Falun: Socialstyrelsen.

- Socialstyrelsen. 2015b. Metodstöd För BBIC [BBIC Handbook]. Falun: Socialstyrelsen.

- Socialstyrelsen. 2016. Informasjonsspecifikasjon för BBIC 2.0 [BBIC specifications 2.0].

- Ulset, G., P. G. Almklov, and J. O. D. Røyrvik 2017. “Ukritisk malbruk i barnevernet? [Uncritical Use of Assessment Frameworks?]” Debate article retrieved from Gemini.no

- United Kingdom Department of Health. 2000. Framework for Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families. London: Stationary Office.

- Vis, S. A., A. Storvold, D. T. Skilbred, Ø. Christiansen, and A. Andersen. 2014. “Statusrapport om barnevernets undersøkelsesarbeid [Status Report on Child Welfare Investigations].” Tromsø: UIT Norges Arktiske Universitet.

- Vis, S. A., C. Lauritzen, and S. Fossum. 2016. “Barnevernets undersøkelsesarbeid - fra bekymring til beslutning. oppsummering av hovedtrekkene i forskningslitteraturen [Child Welfare Investigations - from Worries to Desicion-making. A Litterature Review].” Tromsø: UiT -Arctic University of Norway.

- Visma. 2016. Kvello AF Version 8.3.