ABSTRACT

This qualitative study explores how psychiatric care is negotiated together with multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds and the client as a dialogical process. The purpose of this article is to study the dialogical process of building shared understanding in interprofessional client sessions in a psychiatric clinic.

The data was collected from Finnish interprofessional psychiatric services teams. The research material collected consists of three video-recorded interprofessional client sessions. The data was analysed using narrative content analysis. The findings reveal that question-driven discussion reduces the dialogical space but, on the other hand, is needed to build shared understanding. Dialogical moments including confrontations could give room for multivoicedness in the interprofessional process. The assessment and the treatment plan for the client, i.e. the goals of the client process, were created session by session and jointly by all members of the interprofessional team.

Introduction

The role of interprofessional communication has become increasingly important in the present information-, service- and expertise-oriented society. Due to increasing political and economic pressure, growing emphasis is being placed on achieving better efficiency in the social and health sector. Extensive structural changes and the ability to work jointly across sector boundaries are being increasingly required of the social and health services. As a result, approaches to professional knowledge creation are changing from linear, bilateral transaction and collaboration to dynamic, networked, multi-collaborate innovation ecosystems (European Comission Citation2016). Interprofessional skills have recently been in agenda in social work, as well.

Many studies have shown that productive cooperation between professionals requires trust, reciprocity, mutual aims and benefits, specific roles, common language, and open attitudes (Payne Citation2000, Citation2005; Thomas, Pollard, and Selman Citation2014; Bayne-Smith et al. Citation2014; Bronstein Citation2003; Frost, Robinson and Anning Citation2005). When carried out effectively, such cooperation has the effect of strengthening the service user´s sense of agency. However, studies have also shown that interprofessional teamwork entails a number of problems, such as competition between professionals and the danger of professionals continuing to work in their own silos, so that knowledge is created separately without encouraging an expanded and holistic view. Professionals often work exclusively with the client, resulting in different professionals simultaneously acting out different ‘scripts’ with the client, causing professional client work to be disconnected. Insufficient understanding of the role of other professions can also negatively affect interprofessional collaboration. (Bayne-Smith et al. Citation2014; Glaser and Suter Citation2015; Best and Williams Citation2018; Rydenfält, Borell, and Erlingsdottir Citation2018.) The meaning of interaction and collaboration and how these are actually realized in interprofessional collaboration is, however, less clearly understood. The dialogical aspect of communication may be the key to better understanding of interprofessional client work (McNamee and Gergen. Citation1999; Rober Citation2005; Seikkula Citation2012; Linell Citation2007; Frank Citation2012).

Dialogical theory is a general framework for understanding human action, cognition, communication and language. It represents a counter approach to monologist and individualistic ways of analysing social interaction and human behaviour (Markova and Foppa Citation1990; Linell Citation2007). The purpose of this article is to study the dialogical process of building shared understanding in interprofessional client sessions in a psychiatric clinic.

The data was collected from Finnish interprofessional psychiatric services teams. The research material consists of three video-recorded interprofessional client sessions, and three reflective discussions with workers involved in the process. We analysed three interprofessional meetings of one client in a psychiatric clinic. The client was a young woman who had suffered various mental symptoms for several years. She had had earlier contact with a youth psychiatric clinic and the treatment had continued at an adult outpatient clinic.

We ask: How is shared understanding and collaboration constructed in an interprofessional client session? More specifically we are asking: What kind of dialogical elements can be identified in the interprofessional discussion?

Dialogue as a theoretical framework

During the last decade considerable attention has been given to the dialogical aspect of workplace communication, management, and consultation processes (Yankelovich Citation2001; Isaacs Citation1999; Tsoukas Citation2009). The term dialogy originates from the words ‘dia’, meaning between, and ‘logos’, referring to logical reasoning. When combined, they describe the essence of dialogue or joint understanding of the world. As a metaphor, dialogical interaction may be compared linguistically to generative dancing where both dancers know the steps (Cook and Brown Citation1999). In its broadest sense, the term dialogue refers to conversation, discussion or debate, while being in dialogue or dialoguing with someone tends to infer being on a similar wavelength or having a level of emotional connection.

The theoretical background of dialogue has been researched in the original work of Bakhtin and Emerson (Citation1993) and Lev S. Vygotsky (Citation1986) and developed further by Kenneth Gergen (Citation2009), John Shotter (Citation1995), Markova and Foppa (Citation1990). Dialogue theory has been applied in professional practice, especially in family therapy, by Arnkil and Seikkula (Citation2015), and the intersubjectivity of human cognition and social interaction is recognized by all social scientists.

Shotter and Katz (Citation1999) refer to the concept of ‘living moments’ when describing dialogical moments in discussion. People bodily respond to each other’s utterances and voicings and relate themselves to each other and to their surroundings. Hence, words have meaning only when living human beings make use of them, in communication with another human being. Although language has been a key focus of social constructionism, non-verbal communication plays an even stronger role in creating trust between a worker and a client. (see Goffman Citation1955). Trust is created as interlocutors modify their verbal as well as non-verbal acts through dialogical interaction.

Interaction and the relationships involved in client work should not be seen as fixed and permanent, but as relationships that involve movement on different levels. Seikkula, Laitila, and Rober (Citation2012) have analysed family therapy sessions from the dialogical point of view. They categorize different forms of dominance exercised in the context of a therapy meeting as quantitative dominance (number of replies), semantic dominance (steering the dialogue) or interactive dominance (offering new aspects). Forms of dominance may be changed in the same meeting.

In interprofessional client session dialogue requires a specific level or kind of trust. Trust is a basic fact of social life and is something that we can influence positively. Carl J. Couch (Citation1986) defined a theory of cooperative action based on five elements of interaction. Mönkkönen (Citation2002, Mönkkönen and Puusa Citation2015) has reinterpreted and refined this theory in the context of client work and reformulated Coach’s elements as five hierarchical forms of interaction: presence in the situation (informal), social influence (one-sided power), game (juxtaposition), cooperation (common target), and collaboration (reciprocity, trust). Through these forms the trust building process in a client relationship can also be understood. In the first form, presence in the situation, people acknowledge the presence of others but have little to no contact with each other. In the second form interaction is unidirectional when one participant has power over a group or another individual in an interaction. In the third form of interaction, called game, rivalry between people or teams is apparent. The fourth form of interaction, cooperation, differs from the previous ones due to its inclusion of a shared focus and targets, which are achieved through mutual contracts between professionals and the client. This cannot yet be classed as collaboration because trust and common innovations are still lacking (Engeström Citation1992; Isaacs Citation1999; Tsoukas Citation2009; Yankelovich Citation2001; Rydenfält, Borell, and Erlingsdottir Citation2018). Collaboration is associated with confidence, which diminishes the need for control. Discussion is also more future-oriented, with a common target shared by the professionals and the client. We describe this level of interaction as a dialogical moment, which we see as an important aspect when analysing interaction in the institutional context with its own particular institutional features. Furthermore, Shotter and Katz (Citation1999) stress that in a clinical context the aim should be to understand rather than to explain. This understanding is an active and creative collaborative process, not merely one in which meanings are conveyed by the client and received by the therapist A reflective, sensitive and curious position of professionals reduce expert power and strengthen the client’s position in the conversation especially when the client has earlier had conflicting relationship with social and health professionals. (Rober Citation2005; Seikkula, Laitila, and Rober Citation2012; Agget, Swainson, and Tapsell Citation2015).

Interprofessional understanding from the dialogical perspective

From the dialogical point of view, discussion is always a product of dialogue between speaker and listener, because every utterance invites a response, and an anticipated response of the addressee affects the utterances of the speaker. Moreover, an assessment is not only the doctor’s or social worker’s job, but often a larger interprofessional team is involved in the client’s situation (Maynard Citation1989; Frank Citation2012; Heritage and Maynard Citation2006). Arnkil and Seikkula (Citation2015) also state that an assessment is typically achieved in joint meetings where the experts and the client co-construct shared understanding together. This view is strongly influenced by Bakhtin’s idea of not-knowing and that ‘truth’ is created via communication and social interaction processes with others (McNamee and Gergen. Citation1999; Rober Citation2005; Anderson and Goolishian Citation2005; Author 1. (Citation2002). With a genuine curiosity and through dialogue, the client´s subjective reality will become visible, shared, and tested together.

Joint knowledge creation is an important aspect of collaborative dialogue. Tsoukas (Citation2009) outlined the knowledge creation process and stresses the effectiveness of communication. According to him, when multiple agents interact in open-ended ways, common knowledge and shared views are constructed through the following process: first identifying distinctive differences, then building new combinations and, finally, giving new meanings to old understanding that, during the process, has become new understanding of the situation handled. Even though Tsoukas’s notion of effectiveness relates to the business context, his ideas are also very relevant to social and health care practices. Many studies have highlighted how professionals dominate the definition of the client’s situation. Such meetings are often used only to transfer information to the patient, not to share information. At worst, the patient or client is relegated by the experts to the role of passive recipient (Vuokila-Oikkonen et al. Citation2002). Professionals often act as if they operate in silos, developing their own language, frameworks and values (Thomas, Pollard, and Selman Citation2014; Glaser and Suter Citation2015; Best and Williams Citation2018). This often leads the client and his or her family to consider such interprofessional meetings as irrelevant or inconvenient.

We understand dialogue from two points of view. Firstly, it can be understood as a means of communication, a way to build shared understanding with each other. Secondly, it can be seen as a mean of building collaboration (author 1). Our research question is: how is shared understanding and collaboration constructed in an interprofessional client session? More specifically we are asking: What kind of dialogical elements can be identified in the interprofessional discussion?

Research methodology, data collection and analysis

Our methodological and therefore epistemological choices are premised on social constructionism, which emphasizes the idea that the social world is a subjective construction created by individuals who, through the use of language and interactions, are able to create and sustain a social world of shared meanings (Gergen Citation2009; Flick Citation2015).

Obtaining multimodal data from the real client sessions along with the client feedback immediately after each session was challenging to achieve. In that sense and considering our opportunity to follow and participate intensively in a single client process over a period of three months, our data can be considered exceptional. The data was constructed in 2016 in three interprofessional client meetings including the client, a doctor, a social worker and a psychiatric therapist in psychiatric services. The client’s mother was also present in the last of the meetings. Data was collected by video recording the interprofessional client meetings. The psychiatric meetings between the client and the professionals are hereinafter also referred to as sessions. Participants in the first and second sessions included the client, a doctor, a social worker and a nurse. Participants in the third session included the client, her mother, a doctor and a nurse. The video and audio recordings were transcribed into textual data. The data collection was evaluated continuously during the research process.

The whole data consists of six hours of video (41 pages of transcribed data). The time between each session was two months. Participants in the discussions included an interviewer (I), the client (C), the client’s mother (M) (one session), a doctor (D), a social worker (S) and a psychiatric nurse (P). All professionals had a long working history in the psychiatric field. In this study we focus more on the interdisciplinary discussion aspect of the interprofessional client process rather than the client perspective.

The data was analysed using narrative content analysis from the perspective of dialogical interaction in the client sessions (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998). We chose a narrative approach based on the notion that through free argumentation the participants work their way towards common understanding (Polkinghorne Citation1988; Hänninen Citation2004).

We analysed both the video-recorded data and the transcribed texts. The Atlas.ti software was used as support for the analysis. The data was analysed according to narrative content analysis method as a whole, looking for essential comprehensive meanings related to dialogical interaction (Polkinghorne Citation1988; Hänninen Citation2004). Our narrative content analysis proceeded with watching carefully through all videotaped multi-professional meetings (3pcs) and observing how the interaction was built: who was in voice, who spoke to each other, where the participants looked at and what their body language told us about being in the situation (Agget, Swainson and Tapsell 215). Subsequently, we continued our analysis on the basis of transcriptions, specifying the questions on how the dialogue occurs between the attendants at any stage of the process. In narrative content analysis, it is possible to count phrases, narratives, etc., in order to analyse the content of the research data also from the structural point of view (Kuusela and Hirvonen Citation2017). However, we used phrase counting only to support our qualitative analysis. Instead of counting phrases we were interested in dialogical elements taking repeatedly place in the interaction.

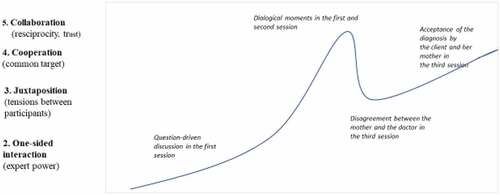

As a result of the narrative content analysis, we identified three narrative categories in interprofessional discussion which together form the common process of building shared understanding. These narrative categories of interprofessional, dialogical process are question-driven discussion, dialogical moments and confrontation. They were repeatedly present in our data, and on bases of them the interprofessional, shared understanding was created. In order to weave together our empirical findings and theory of dialogical interaction, we examined our findings on different levels of interaction (author 1). These are: 1. Presence in the situation (shared situation), 2. One-sided interaction (expert power), 3. Juxtaposition (tension between participants), 4. Cooperation (common target), and 5. Collaboration (reciprocity, trust).

Ethical consideration was given throughout the data collection and analysis process. We received ethical permission for the research process from the Council of Research Ethics of the local university hospital district. Informed consent was received from each participant. With respect to both ethical considerations and the sensitivity related to the research setting, special attention was given to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality when informing the participants about the study.

This research complied with Finland’s national ethical principles of research (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity Citation2019), emphasizing the voluntary and anonymous nature of research and principles pertaining confidentiality. All the research participants were asked for their informed consent on participating in the study at every research phase. In the following section we describe how interaction is constructed in the three interprofessional meetings.

Findings

Question-driven discussion reduces the dialogical space

The first meeting we videotaped was client’s first visit at that clinic and she also met the professionals for the first time. The purpose of the process was to conduct an interprofessional assessment of the client’s situation and support needs. The client had previously been treated at a youth psychiatric clinic, but no diagnosis had been made during that treatment.

In the first session the doctor was interested in changes in the client´s mood and asked numerous questions about how the client’s symptoms have changed compared to earlier stages in her life. Afterwards, in the reflective discussion the doctor stated that the session represented a normal or standard pre-treatment evaluation. A lot of questions are asked in order to obtain a picture of the symptoms and life situation of the client. However, we think the bigger and richer picture could be outlined by creating space for freer discussion. Here is an example of question-driven discussion in which the psychiatric nurse and social worker are stating questions and the client is answering:

What do you think, what are the reasons why would you start to visit here? Why did you come here?

The mood thing.

And the mood thing is … ?

Well there are these symptoms … my moods keep changing and it’s difficult to be … And when I feel bad it’s very difficult … I don’t know … .

Yes.

When you have a bad mood is that the most difficult thing for you, or does it vary … ?

Maybe both. When I’m feeling bad it is really difficult, but it’s not easy when I’m feeling over-chirpy either.

How long have you suffered these symptoms?

Maybe since the autumn

When we noticed the strong role of questions in the discussion, we took a closer look to structural features such as number of questions and replies, tone of voice and nonverbal elements of discussion. First session the client was asked 131 questions, in the second session 118, and in the third session 33 questions. The doctor asked majority of the questions, with the other professionals asking fewer questions, but all of the professionals invited the client to tell as openly as possible about her condition and her everyday life. The doctor played a very dominant role in this discussion and questions in discussion strengthened a normative position of the doctor in their discussion (Heritage Citation1987.)

The questions were mostly closed questions (have you, do you, when, how much, etc.) and the answers were quite short. Such questioning resembles the diagnostic speech of the physician, in which the patient’s symptoms are described (see Glaser and Suter Citation2015). The same kind of discussion occurred also when the client’s work and financial situation were addressed, where the key questioner was the social worker. In contrast, open questions (what do you think, what kind of, how does this sound, etc.) drew the client into open dialogue.

Despite the largely question-driven discussion, the client was subtly given space by the professionals to tell how she feels about her condition, which she described, for example, as ‘normal, the way I have always been’. The discussion was limited to the client herself, other actors such as family members or other external support were not mentioned by the doctor, social worker or nurse. The professionals’ gaze was directed at the client, while the client sat with her head bent slightly downward. In the reflective discussion, the professionals considered the client’s posture to be due to the tension of the meeting. In the second session the client continuously fiddled with her dress and her gaze was directed downward most of the time; however, she glanced at the professionals when she was talking to them. In the third session, in which client´s mother was in attendance, the client appeared less nervous but continued to look downwards. On the other hand, in all three sessions the client listened carefully to the discussion of the professionals, answered their questions and explained her own views fluently. During the discussion, the client smiled and appeared to acknowledge that she was being heard and understood, although she seldom raised her eyes and looked directly at the professionals.

Question-driven discussion can be driven in part by the hierarchical position of the doctor. Doctors are accustomed to having a leading role in interprofessional health care teams and their medical orientation can be dominant, thus naturally affecting the nature of interaction within the team (Dryden and Mytton Citation1999; Glaser and Suter Citation2015; Rydenfält, Borell, and Erlingsdottir Citation2018). From the dialogical point of view it was obvious that when symptom descriptions were reduced, there was more space for other questions related to the client’s life.

Dialogical moments

As a result of our narrative content analysis, we also identified a category in the sessions that we named ‘dialogical moments’ (Shotter and Katz Citation1999; Helin Citation2011). By that we mean moments where shared feelings are appearing in the discussion and every part of the discussion seems to be strong part of the dialogy. One such moment was when the client was telling about her night-time fears. On the bases of our narrative analysis, dialogical elements were apparent in this moment because each of the professionals seemed to be ‘touched’ by the client´s story. This elicited feeling of warmth and understanding during that moment and, in the opinion of the researchers, highlighted the client-oriented approach of the interprofessional meeting. In this dialogical moment, the professionals warmly and thoughtfully shared their feelings with the client. When the client explained the illusion, she was experiencing of a dark figure appearing next to her bed at night, the doctor replied, ‘That’s a really scary experience’ and the social worker and psychiatric nurse also nodded, seemingly sharing the feelings experienced by the client. A dialogical moment thus emerged even though the client’s story was elicited by questioning by the professionals, as shown in the following (CI1):

What kind of things you are scared of?

I don’t really know. I have terrible nightmares … . and … I’m somehow … paranoid. Whenever there’s some sort of creak and … I get afraid and …

Are you afraid that there’s someone in the room?

Yeah, yeah … I am.

Have you ever seen anyone in the room?

Yeah! … I have.

Okay. What did you see?

I see a sort of black figure.

Yeah.

It’s quite a new thing. Or maybe it was … a couple of months ago when I saw it for the first time. I was sleeping … and … then I woke up … and I saw it next to my bed. Actually … I woke up hearing footsteps … I heard it walking … heard steps, like someone was walking in a wooden house … . I heard the steps and … .it opened the door … I opened my eyes and … saw it was standing next to my bed.

Was it a human figure or not?

Yeah, I don’t know if it was a man or a woman, I closed my eyes.

Was it a ghost?

Yeah, I would call it a ghost. (…)

When did you see it the last time?

About two weeks ago, maybe

Okay … That’s a really scary experience.

In the quote above the professionals are engaged jointly with the client’s story and the professional position of the participants is not easy to identify. In this quote, questions took on a different meaning than in the first quote presented earlier, because this part of discussion was facilitated by the open attitude of all parties. In dialogical theories this has been seen as not-knowing approach to interact (Anderson and Goolishian Citation2005; Seikkula Citation2012). Closed questions are also important during the client´s storytelling when aiming at obtaining a deeper understanding of the client’s experience (see Holger and Locher Citation2012). Nevertheless, the client’s story carried the conversation and was emotionally shared by the other attendees.

In the first client session, the client herself created the content of the discussion. In the second discussion, the professionals provided more space for the client’s experience and the joint reflecting of the matter. The professionals played a smaller role in the knowledge creation process and participated mostly by asking the client questions, thus generating a question-driven discussion. The questions asked by the professionals were more specific than in the first session in order to create a more specific picture of the client’s condition and symptoms. This information was gained by asking questions about and discussing concrete events in the client’s life. For example, when talking about the client’s eating disorder and self-image, the doctor asked the client: ‘What do you see when you look in the mirror?’ This question moved the discussion towards the client’s personal experience. A dialogical moment of the discussion appears also when the client explains her deeper emotions to the professionals, and they are encountering those feelings very softly and sympathetic.

What do you see when you look in the mirror?

I don’t want to say because it sounds so bad.

You don’t want to say?

Yeah.

Why does it sound so bad?

Everyone says it sounds bad and no one believes it when I say I see a fat girl … Everyone says ‘but you must know you’re not fat’. That’s why I never say it to anyone.

Mhh.

It looks to you like there’s a fat girl [in the mirror]?

Yeah.

By asking ‘what do you see in the mirror? A therapist opened the door to the client’s feelings more closely. Social relationships and life conditions in general were discussed more in the second session than in the first session. For example, the client’s financial matters and employment history were discussed and a personal meeting with the social worker was scheduled to seek support in these areas. Social worker changed the focus of the discussion from medication to social situation (see semantic dominance Seikkula, Laitila, and Rober Citation2012). In that part of discussion, reciprocity was seen also between professionals, not only towards a client. Professionals seemingly tried to understand client’s experiences, and consequently they at the same time changed their position from an observer to the experienced self (Rober Citation2005).

Confrontations gives room for multivoicedness

In the third session the doctor was seemingly the most active member of the group of professionals. The third session also differed from the previous sessions as the client’s mother was present as an active partner in discussion. Situation was controversial between a doctor and mother, and doctor had to defend diagnosis she made. The third narrative category in our narrative content analysis is named ‘confrontation’. By that we mean that the dialogue (especially in the third discussion) was also constructed by confrontation between the attendees. In dialogical discussion the parties can also present controversial opinions and common understanding is created by accepting those perspectives to the part of the discussion, listening to them and finally combining different views together.

About Lisa’s diagnosis … may be … we are a bit confused on it … that such a diagnosis was now given for her … hmm … during the six-week period in a juvenile psychiatric clinic … we were told that Lisa´s symptoms are referring more to depression.

However … all the data I collected on Lisa and what you (mother) have told about her, that her hyperactive periods last longer than three hours … sometimes even longer than 1,5 weeks … hmm … Lisa, your symptoms started at very young age and have been. multifacial … you have had hallucination. These are not typical symptoms of depression.

In this narrative, the mother brought up different voices. The client’s mother used term ‘we’ when presenting her views, thus indicating that she was speaking on behalf of both herself and her daughter (see Frank Citation2012). She spoke the voice of client’s father by describing how these two behave in the same way. He also brought up the voice of a doctor in the past, highlighting previous findings from his daughter’s diagnosis. The mother was seemingly worried about the diagnosis offered and, for example, raised the concern that her daughter’s educational plans could be jeopardized by such a diagnosis. The client herself nodded in support and occasionally added to her mother’s statements.

Juhila, Günther, and Raitakari (Citation2015) analysed interprofessional client sessions by analysing the identity categories produced in a meeting and how the client’s care plan is jointly made. According to their findings, the discourse of linear time was dominant in the professionals’ interaction, but the client can challenge this by, for example, raising momentary concerns. In our data, linear discourse was particularly evident at the last meeting, where the diagnosis opened up a discussion about the client´s future. Mother, in particular, opened this perspective.

The client did not participate in the discussion as actively as her mother, although the mother and client together produced so-called ‘normalization speech’ regarding the symptoms and life situation of the client versus the ‘professional’ or ‘sickness speech’ of the doctor when talking about the official diagnosis. A client described her symptoms as ‘strong imaginary world’ and mother contributed ‘can say that I have had exactly the same as a child’.

The client and her mother expressed misgivings regarding the given diagnosis, especially when the client´s future was discussed. When the doctor described the diagnosis as typical symptoms of the mother responded by normalizing her daughter’s symptoms (e.g. by saying ‘she is exactly like her father’). Understandably, the mother did not want her daughter to be diagnosed as ‘mentally ill’ and was worried about the impact such a diagnosis might have on her daughter’s future. As Billig et al. (Citation1988) have argued, in interaction arguments do not move in a linear manner but are dilemmatic with many voices. Common sense provides the individual with the seeds for contrary themes, which can conflict in dilemmatic situations. Both mother and daughter disputed the given diagnosis, but on the other hand they brought up symptoms for which the girl needed support.

A controversial situation contributed, by Bahtin´s word, polyphony of dialogue. Although the doctor had to justify his view to the mother, he was very calm. Such challenging situations require sensitivity and an ability to give space for cooperation. Obviously, client’s need for support and the doctor’s open attitude to criticism moved the discussion forward to the level of cooperation. The other professionals supported the doctor’s views but otherwise played no significant role in the discussion. At the end of the session the client and her mother gave their silent approval of the diagnosis and the diagnosis was confirmed by all of the participants at the end of the meeting.

The social worker had a strong role in clarifying issues related to a basic livelihood for the client (Arajärvi et al. Citation2021). In the meeting she diverted the debate from medical issues to social issues. For example, she asked the client about her relations to her friends, and how she could manage to maintain them. This discussion of the episode was very considerate and dialogical. The social worker and therapist did not try to offer ‘superficial advice but rather they shared the client’s experience.

´I’m tired of keeping in touch with my friends and I can suddenly stop responding to messages I’m not interested in. Sometimes I try to be interested in my friend´s situation, but I often have nothing to say to them.”

´It is understandable that you don’t have the strength to chat with your friends and orientate to their situations´

´I have my own things in my mind, and it is difficult to focus on other things´

´It sounds like you don’t have any room for other things, because you have so much to deal with your own issues´

Joint professional working increases client’s security (Rober Citation2005; Frank Citation2012; Mönkkönen, Silen-Lipponen, Kekoni and Saaranen. Citation2021).

Moving positions of interaction

To combine our empirical findings and theory of dialogical interaction we examined our findings -three narrative categories presented above- on different levels of interaction (author 1 XXXX) which are: 1. Presence in the situation (shared situation), 2. One-sided interaction (expert power), 3. Juxtaposition (tension between participants), 4. Cooperation (common target), and 5. Collaboration (reciprocity, trust).

In summary, we present in . moving postions of interaction in interprofessional client sessions. The first level appears when the client consents to be present in the interprofessional meeting. Institutional trust relates to trust by persons, families, communities, societal institutions within the public domain and formal institutions (Harré Citation1999). In our case, it means that the client has accepted interprofessional support and has agreed to attend the meeting with the interprofessional team. At the beginning of the process, one-directional interaction was manifested as question-driven discussion. Communication was asymmetrical and elements of expert power were clearly evident (see Heritage and Maynard Citation2006; Seikkula, Laitila, and Rober Citation2012), although the discussion was in many ways very professional and atmosphere was open-minded and respectful between the parties. The third level of interaction was located in our data in the confrontation between the doctor and the client’s mother (when negotiating the diagnosis). A sort of game or juxtaposition was evident in the negotiation of the diagnosis, with the client and her mother disagreeing with the professionals (Author 1, (Citation2002). At the end of the third meeting the interaction proceeded to the fourth level with acceptance of the diagnosis by the client, her mother and the professionals, and by planning the treatment further together.

In the studied case, dialogue occurred specifically in situations where all of the professionals were ‘touched’ by the story of the client, which we earlier considered as ‘dialogical moments’ due to the establishment of trust and commitment among the participants. One-way interaction can move towards dialogic interaction when professionals use open questions and allow space for the client’s own story to be told. Discussion between the client and the professionals occasionally reached the level of collaboration in the first and second meeting, although it changed later to juxtaposition in the third meeting in which the client’s mother was also present. Our results show that different levels and positions of interaction are not permanent, especially in institutional relationships, and that various forms of interaction may exist during an interprofessional client process. When an interprofessional team works as it should, the team merges, even though each team member brings their own expertise in support of the client. Connections to evidence-based practice (EBP) can also be seen in the studied client process. EBP is a process ‘in which practitioners integrate the best research evidence available with their practice expertise, and with client attributes, values, preferences and circumstances’ (Rubin Citation2008, 7). In its wide understanding, when EBP is understood as a process, EBP also takes into account the local context and the client’s clinical state and circumstances, preferences and actions and, as the result of the process, the intervention is chosen in collaboration with the client (Gambrill Citation1999, Citation2003). The role of the social worker in EBP is seen, who critically appraises the effectiveness and suitability of the interventions for the client. In the studied client process, the social worker as well as other professionals can be seen as reflective professionals, who together with the client (and her mother) negotiate and evaluate the understanding and best possible support and service to the client.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore how shared understanding is built in an interprofessional client process. We showed that shared understanding is built on in a trust-building process, that we name question-driven discussion, dialogical moments, and confrontation taking place between attendees of the meeting.

We explored the structural features of the discussion, such as number of questions and replies, tone of voice and nonverbal elements. The sessions included a large number of questions by the professionals. However, although the discussion was question-driven, we consider that customer-oriented work was at the same time attained. Many resource-centred therapy methods, such as the solution-based and motivational interview, emphasize this approach (Dryden and Mytton Citation1999) and professionals in the psychiatric field are very familiar with this orientation. These approaches have also brought up an importance of emphasizing the way to use client’s own words, not professional assumptions or ‘symptom speech’. Many professionals also work actively to soften asymmetry between a professional and a client. It is nevertheless valid to ask whether such discussion reduces the authenticity of interaction and the sense of client autonomy. From the dialogical point of view, one-directional discussion is located on the level of social influence, because question-driven discussion does not create space for dialogue (Author 1, (Citation2002). In social work, a balance between these positions should be find. In dialogical relationship and trust and the client´s perspective will become visible, shared, and tested together.

In the present case, other services were barely mentioned in the discussion and a more holistic picture of the client´s social support was therefore left unevaluated (Payne Citation2005). In social work, interprofessional and cross-sector work is indispensable as clients’ needs are often very complex. It is also important to learn how different actors approach the client´s situation and how common understanding is created in different organizations and by different actors. Interprofessional teamwork is a collective knowledge creation process and, for the client, it can be a dilemmatic part of their life.

The main goal of interprofessional care is to create new and broad understanding of the client’s life jointly with the client and each of the professionals involved in the client’s care in order to best meet the client’s needs (Best and Williams Citation2018; Blakey Citation2014; Rydenfält, Borell, and Erlingsdottir Citation2018). According to Seikkula (Citation2012), traditional evidence-based medicine and psychology are based on the idea that the expert chooses the proper treatment after an accurate diagnosis, without constructing common understanding of the situation together with the client.

The dialogical approach is not a specific method, but more a way of thinking, or even broader, a way of life and a philosophical idea (Shotter and Katz Citation1999; Seikkula Citation2012). Similarly, interprofessional teamwork is not just a method of client work, but rather a dialogical orientation to client work. Interprofessional work does not merely mean that more people are able to participate in decision making, but that new actors bring their different backgrounds and ideas to the table. (Yankelovich Citation2001). Dialogical practice is seen as a collaborative approach which emphasizes a transparent meaning and decision-making process based on an acceptance a polyphony of multiple voices. (Seikkula, Laitila, and Rober Citation2012; Rober Citation2005). In dialogical practice, the client is the most important actor, while the professionals critically reflect on their own approaches (Payne Citation2005; Banks Citation2012). Each professional has their own role in the discussion, but professional expertise merges into one entity towards a common goal. In addition, the discussion may vary between different levels of interaction during a single meeting or client process (Author 1, (Citation2002; Author et al. 2014, Seikkula et al. Citation2012). Various interactional elements can promote the effectiveness of interprofessional work and can offer good support to the client. Structural features create the basis for good discussion where all participants can be active in constructing knowledge. From the structural and narrative point of view we can examine the client´s contribution to the discussion, how each participant’s expertise is utilized, and what kind of story of the client’s life situation is jointly constructed.

In the studied case, dialogue occurred in situations that we call ‘dialogical moments’ where all of the professionals were ‘touched’ by the client´s story. The relation between trust and dialogical orientation can be seen as symbiotic, which helps multi-voicedness in a knowledge creation process (Kuusela and Hirvonen Citation2017). Dialogue also embodies in one way or another the outside world and the perspectives of the people in the speaker’s life. According to Frank (Citation2012) for example narratives of illness contain a number of different voices, such as the voice of medical professionals with their explanations or the voice of family members or friends with their wishes and assumptions. Each professional can also speak with the voice of the client, the voice of the organization, or their own voice. In interprofessional discussion it is important to gather all of these perspectives together in order to promote the wellbeing of the client. Also, Bakhtin (Citation1993) saw different voices as an important part of our inner dialogue, with whom a person is speaking, and to whom words are addressed. According to Bakhtin, understanding is not a passive process (listening), but merely a creative, active process. This mean that a client does not expect listener but is rather oriented towards a responsive and creative understanding in order to expand his/her choices, ideas and possibilities with therapists. (Rober Citation2005; Leiman Citation2011).

There are some limitations in relation to the results of the study. The data was constructed in only one client case, even though it consisted of several meetings and many hours of videotaped material. The results could have been different if the clients were different or the professionals were different. On the other hand, in qualitative research this is a fact that is understood but does not affect the relevancy of the results: it is as important to have a deep understanding of one case than wide understanding of many cases. Also, the data was collected in Finland, and is connected to national health care system. In our understanding, the elements of interprofessional interaction can still be applied in more general sense. The study design could have been a case study. However, we considered that the qualitative study is typically focused on a certain case. In addition, our research was focused on one period of the process of a particular treatment and we could not look in the customer process as a whole (Flick Citation2015).

Dialogue in interprofessional work can be seen as a continuous social process in which the traditional professional position can be re-framed as shared work. Interpersonal skills are of key importance here, as problems are handled and situated in relationship with people and communities (Lähteinen et al. Citation2017). In our case, collaborative construction of the diagnosis was an example of this. Drawing on Frost, Robinson, and Anning (Citation2005) description of social work, we can view a dialogic expert as a joined-up professional with an agenda that ‘seeks to liaise, to mediate, and to negotiate between professions and between the professions and the children and their families’. Greater interprofessional understanding also has a positive influence on professional identity development. Professionals expand their identity as a professional and begin to take on board the wider situation of the client when collaborating with other health care professionals. A client gets also coordinated services when collaboration between professional is achieved. (Bayne-Smith et al. Citation2014; Glaser and Suter Citation2015). In future, regular evaluation of the function of interprofessional teams, as well as training in interprofessional approaches and developing joint work between professionals in social and health care will be key to service development. Our research contributes to this debate.

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Anssi Savolainen, Kaisa Martikainen and Aini Pehkonen for data collection is acknowledged editable/document.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agget, P., M. Swainson, and D. Tapsell. 2015. “Seeking Permission: An Interviewing Stance for Finding Connection with Hard to Reach Families.” Journal of Family Therapy 37 (2): 190–209. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00558.x.

- Anderson, H., and H. Goolishian. 2005. “Not-knowing Approach to Therapy.” In Therapy as Social Construction, edited by S. McNamee and K. Gergen, 8–25. London: Sage.

- Arajärvi, M., K. Mönkkönen, T. Kekoni, and T. Toikko. 2021. “Sosiaalityön psykososiaalisen asiantuntijuuden hyödyntämiseen vaikuttavat tekijät nuorisopsykiatrian avohoidossa.” The Utilization of Psychosocial Expertise in Social Work as Part of Multidisciplinary Collaboration in Adolescent Psychiatry Outpatient Care.” Sosiaalilääketieteellinen Aikakauslehti – (Journal of Social Medicine) 58: 46–60.

- Arnkil, T., and J. Seikkula. 2015. “Developing Dialogicity in Relational Practices: Reflecting on Experiences from Open Dialogues.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 36 (1): 142–154. doi:10.1002/anzf.1099.

- Bakhtin, M., and C. Emerson. 1993. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Theory and History of Literature. Translated and edited by Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Banks, S. 2012. Ethics and Values in Social Work. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Bayne-Smith, M., T. Mizrahi, Y. Korazim-Körösy, and C. Yossi. 2014. “Professional Identity and Participation in Interprofessional Community Collaboration.” Issues in Interdisciplinary Studies, (32): 103–133.

- Best, S., and S. Williams. 2018. “Professional Identity in Interprofessional Teams: Findings from Scoping Review.” Journal of Interprofessional Care. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1536040.

- Billig, M., S. Condor, D. Edwards, M. Gane, D. Middleton, and A. Radley. 1988. Ideological Dilemmas: A Social Psychology of Everyday Thinking. Thousand Oaks CA: SAGE.

- Blakey, J. 2014. “We’re All in This Together: Moving toward an Interdisciplinary Model of Practice between Child Protection and Substance Abuse Treatment Professionals.” Journal of Public Child Welfare 8 (5): 491–513. doi:10.1080/15548732.2014.948583.

- Bronstein, L. R. 2003. “A Model for Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” Social Work 48 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1093/sw/48.3.297.

- Cook, S. D. N., and S. Brown. 1999. “Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance between Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing.” Organization Science 10 (4): 381–400. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.4.381.

- Couch, C. J. 1986. “Elementary Forms of Social Activity.” In Studies in the Symbolic Interaction Research Annual, edited by S. Saxton and M. Katovick, 113–139. London: JAI Press. The Iowa School, Supplement 2 (Part 2).

- Dryden, W., and J. Mytton. 1999. Four Approaches to Counselling and Psychotherapy. London, New York: Routledge.

- Engeström, Y. 1992. Interactive Expertise: Studies in Distributed Working Intelligence, 83. University of Helsinki. Department of Education. Research Bulletin. Washington, D.C.

- Finnish, National Board on Research Integrity. 2019. Responsible conduct of research and procedures of handling allegations of misconduct of Finland, Retrieved, March 2020. Https://www.tenk.fi/en

- European Comission. 2016. “Open Innovation. Open Science. Open to World – A Vision for Europe. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation.” Unit A1. B-1049 Brussels.

- Flick, U. 2015. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London, England: SAGE.

- Frank, W. A. 2012. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. A. Holstein and J. F. Gubrium, 33–52. London: Sage Publication . doi:10.4135/9781506335117.n3.

- Frost, N., M. Robinson, and A. Anning. 2005. “Social Workers in Multidisciplinary Teams: Issues and Dilemmas for Professional Practice.” Child and Family Social Work 10: 187–196. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00370.x.

- Gambrill, E. 1999. “Evidence-based Practice: An Alternative to Authority-based Practice.” Families in Society 80 (4). Social Science Premium Collection. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.1214.

- Gambrill, E. 2003. “Evidence-based Practice: Sea Change or the Emperor’s New Clothes?” Journal of Social Work Education 39: 3–23. doi:10.1080/10437797.2003.10779115.

- Gergen, K. 2009. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Glaser, B., and E. Suter. 2015. “Interprofessional Collaboration and Integration as Experienced by Social Workers in Health Care.” Social Work in Health Care 55 (5): 395–408. doi:10.1080/00981389.2015.1116483.

- Goffman, E. 1955. Interaction Ritual. Essays on Face-to-Face Behaviour. London: Penguin Books.

- Hänninen, V. 2004. “A Model of Narrative Circulation.” Narrative Inquiry 14 (1): 69–85. doi:10.1075/ni.14.1.04han.

- Harré, R. 1999. “Trust and Its Surrogates: Psychological Foundations of Political Process.” In Democracy and Trust, edited by M. E. Warren, 249–272. Cambrodge: Cambridge University Press.

- Helin, J. 2011. “Living Moments in Family Meetings: A Process Study in the Family Business Context; Jönköping International Business School.” JIBS Dissertation Series No. 070. Sweden.

- Heritage, J. 1987. “Ethnomethodology.” In Social Theory Today, edited by A. Giddens and J. Turner, 224–272. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heritage, J., and D. Maynard. 2006. “Problems and Prospects in the Study of Physician-patient Interaction: 30 Years of Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 32 (1): 351–374. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.32.082905.093959.

- Holger, L., and M. A. Locher. 2012. Advice in Discourse. Amsterdam: Philadelphia Jon Benjams Publisching Company.

- Isaacs, W. 1999. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life. New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group.

- Juhila, K., K. Günther, and K. Raitakari. 2015. “Negotiating Mental Health Rehabilitation Plans: Joint Future Talk and Clashing Time Talk in Professional Client Interaction.” Time and Society 24 (1): 5–26. doi10.1177/0961463X14523925.

- Kaarina M. Dialogisuus kommunikaationa ja suhteena. Vastaaminen, vastuu ja valta sosiaalialan asiakassuhteen vuorovaikutuksessa. (Dialogical as a means of communication and relationships. The significance of response, power and responsibility in client work. Academic dissertation of Social Psychology. Kuopio, Finland. University of Kuopio.2002

- Kuusela, P., and P. Hirvonen. 2017. “Strategy Discussions and Dialogicality: MultiVoicedness and the We-Mode of Action in Management Board Meeting.” Journal of Constructivist Psychology 31 (4): 420–439. doi:10.1080/10720537.2017.1326328.

- Lähteinen, S., S. Raitakari, K. K. Hänninen, A. Kekoni, T. Krok, and P. Skaffari. 2017. “Social Work Education in Finland: Courses for Competency.” SOSNET Publicans 8. Accessed 15 Sep 2020. http://www.sosnet.fi/loader.aspx?id=a10e5eeb-3e9f-47dc-9cae-6576b58a4a6e.

- Leiman, M. 2011. “Mikhail Bakhtin’s Contribution to Psychotherapy Research.” Culture and Psychology 17 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1177/1354067X11418543.

- Lieblich, A., R. Tuval-Mashiach, and T. Zilber. 1998. Narrative Research. Reading, Analysis and Interpretation. Thousand Oaks, London; New Delhi: Sage Publication.

- Linell, P. 2007. “Dialogicality in Languages, Minds and Brains: Is There a Convergence between Dialogism and Neuro-biology?” Language Sciences 29 (5): 605–620. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2007.01.001.

- Markova, I., and K. Foppa, eds. 1990. The Dynamics of Dialogue. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Maynard, D. 1989. “Notes on the Delivery and Reception of Diagnostic News regarding Mental Disabilities.” In Book Directions in the Study of Social Order, 55–67. New York: Irvington.

- McNamee, S., and K. Gergen. 1999. Relational Responsibility. Resources for Sustainable Dialogue. London: Sage Publication.

- Mönkkönen, K. and Puusa, A. 2015. From Disunited to Joint Action: The Dialogue reflecting the Construction of Organizational Identity after Merger. Sage Open, 1–13. DOI/1.1177/2158244015599429 sgo.sagepub.com

- Mönkkönen, K., Silen-Lipponen, M., Kekoni, T., Saarannen, T. 2021. Interprofessional understunding of etchical dilemmas: Learning experiences of simulation learning in social welfare and health care education. The Journal of Social Work Values and Etchics, 18 (2). (Publishing)

- Payne, M. 2000. Teamwork in Multiprofessional Care. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Payne, M. 2005. Modern Social Work Theory. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Rober, P. 2005. “The Therapist´s Self in Dialogical Family Therapy: Some Ideas about Not-knowing and the Therapist´s Inner Conversation.” Family Process 44 (4): 477–495. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00073.x.

- Rubin, A. 2008. Practitioner’s Guide to Using Research for Evidence-based Practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Rydenfält, C., J. Borell, and G. Erlingsdottir. 2018. “What Do Doctors Mean When They Talk about Teamwork? Possible Implications for Interprofessional Care.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 33 (6): 714–723. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.

- Seikkula, J. 2012. “Open Dialogues with Good and Poor Outcomes for Psychotic Crises: Examples from Families with Violence.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 28 (3): 263–274. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2002.tb01183.x.

- Seikkula, J., A. Laitila, and P. Rober. 2012. “Making Sense of Multi-actor Dialogues in Family Therapy and Network Meetings.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 38 (4): 667–687. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00238.x.

- Shotter, J. 1995. “Dialogical Psychology.” In Rethinking Psychology, edited by J. Smith, R. Harré, and L. Van Langenhove, 161–178. London: Sage. book.

- Shotter, J., and A. M. Katz. 1999. “Living Moments in Dialogical Exchanges.” Human Systems 9 (2): 81–93.

- Thomas, J., K. Pollard, and D. Selman. 2014. Interprofessional Working in Health and Social Care. Professional Perspectives. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tsoukas, H. 2009. “A Dialogical Approach to the Creation of New Knowledge in Organizations.” Organization Science 6 (20): 941–957. doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0435.

- Vuokila-Oikkonen, P., S. Janhonen, O. Saarento, and M. Harri. 2002. “Storytelling of Co-operative Team Meetings in Acute Psychiatric Care.” Journal of Advanced Care 40 (2): 189–198. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02361.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1986. Thought and Language. New York: Wiley.

- Yankelovich, D. 2001. The Magic of Dialogue: Transforming Conflict into Cooperation. USA: Touch Stone.