ABSTRACT

The association between work and integration is rarely questioned in Norwegian discourses on immigration and integration. Globalization, migration, and social problems continue to challenge social work practice, creating tensions in the welfare state. The aim of this integrative review is to clarify major themes, provide a synthesis of current understandings, and consider the implications for social work practice. Twenty-eight articles from the Norwegian welfare context were obtained through systematic searches in four databases and a search-engine. Thematic analysis resulted in the following findings: (1) Employment and outcome for immigrants in the Norwegian labour market, (2) Immigrant women – participation and equality, (3) Discrimination in Norwegian working life, and (4) Challenges ahead and possible solutions. Findings show that Norway is an egalitarian society with high social mobility, but immigrants, despite early entry to work, had a noticeably less stable attachment to the labour market than native Norwegians. Discrimination was identified and affected immigrants as well as their descendants. Immigrant women’s participation in the workforce was perceived as the way to reduce differences. Still, gender mainstreaming and freedom of choice appeared to depend upon immigrant women’s embracing the dual earner norm. Current policies seem unable to provide immigrants with qualifications needed to perform equally to native Norwegians. Throughout the dataset, there were suggestions for ways policies could be changed to permit higher employment rates for immigrants, thereby improving integration.

Introduction

Continued waves of migration expose vulnerable people to precarious living conditions, cementing a gap between immigrants and natives worldwide (International Organization for Migration Citation2018; United Nations Citation2017; World Health Organization Citation2019). Discourses on immigration and integration continue to see immigration as a problem that needs solving (Hagelund Citation2020; Lucassen Citation2018). Despite compelling and consistent support for the idea of integration of immigrants in receiving countries, the self-same countries implemented barriers designed to prevent or significantly reduce immigration from the global south (International Organization for Migration Citation2018). Norway narrowed possibilities for immigrants to enter and gain residency in a draft solution to the Storting in 2015, known as the asylum agreement (Prop. Nr 90 L Citation2015 – 2016. Throughout Europe, the political justification for actions designed to reduce immigration included: protecting national interests; ensuring economic sustainability; and ensuring the (primarily economic) ability to include newcomers (Holmes and Castañeda Citation2016; Rheindorf and Wodak Citation2018).

Immigration and integration are important issues at the midst of the discussion regarding the welfare states’ sustainability (Midtbøen Citation2017). In Norwegian official reports on the welfare state and immigration (e.g. NOU Citation2011, 7; NOU Citation2017:2), the labour market is emphasized as instrumental in immigrants’ integration into society. Hence it is crucial to gain knowledge on work and integration to improve social works practice. The main purpose of this study is to explore the association between work and integration by reviewing previous research in the Norwegian welfare context. When I use the term association, I aim to demonstrate how work and integration interact, connect, and relate. The aim is to clarify major themes and provide a synthesis of current understanding of the association between work and integration.

Work with immigrants and integration are important fields in social work (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Nadan Citation2017; Käkelä, Citation2020; Potocky and Naseh Citation2019; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). Solidarity with marginalized groups, fighting against poverty and working towards social justice and social change are central to professional social work (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Potocky and Naseh Citation2019). According to Marthinsen (Citation2011, Citation2014) social work struggles to combine its own ethical principles with the bureaucratizing of welfare states (standardization, efficiency) and demands for evidence-based practice. Globalization, migration, and social problems continue to add to the tension between practice in the welfare state and ethical principles (Jönsson Citation2014). The current study will promote how social works perspectives and practice can provide significant contribution.

This paper concerns refugees, asylum seekers, immigrants, and migrants. I use the terms immigrants and descendants. In this paper, immigrants are defined as individuals born abroad with two, foreign-born parents and four foreign-born grandparents (Statistics Norway Citation2019b). Integration is defined as the degree to which immigrants have the knowledge and capacity to build a successful, fulfilling life in the host society (Harder et al. Citation2018). Work is defined as gainful employment.

Background

Nordic welfare regimes are characterized as social democratic models, defined by universalism and decommodification (Esping-Andersen Citation1990; Sandvin, Vike, and Anvik Citation2020). In the Norwegian welfare state, a reasonable level of welfare for all citizens, independent from labour market and economic status, rests on broad taxation (Sandvin, Vike, and Anvik Citation2020). Consequently, work is particularly important for the sustainability of the welfare state (Sandvin, Vike, and Anvik Citation2020).

Norway, Sweden, and Denmark provide immigrants with support organized in introductory programmes. Increased convergence, legislation, and choices of instruments are noticeable (Hernes Citation2018; Breidahl Citation2017; Borevi; Jensen and Mouritsen Citation2017). Still, enforced politics differ (Hernes Citation2018; Breidahl Citation2017; Borevi; Jensen and Mouritsen Citation2017). Norway and Sweden provide generous benefits while Denmark has a more restrictive integration policy (Hernes Citation2018; Breidahl Citation2017; Borevi; Jensen and Mouritsen Citation2017).

The Scandinavian countries have had trouble integrating immigrants from the global South into the labour market because immigrants’ skills match the requirements in the labour market poorly (Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2011). Compared to Denmark and Sweden, Norway does better in terms of employment levels for immigrants with lower education (Hernes et al. Citation2019). Sweden and Norway have the best trajectories for immigrants with secondary and tertiary education and Denmark has better estimated employment rates for all groups during the first years (Hernes et al. Citation2019).

The Norwegian Introduction Programme for Newly Arrived Immigrants [NIP], offers language-training and civic knowledge as well as job training (Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2011). Statistics revealed significantly lower employment rates for immigrants, 67.1%, compared to ethnic Norwegians, 78.5% (Statistics Norway Citation2019a). The percentage of immigrants in the Norwegian population is 18.2%, and 51.6% of the immigrants in the Norwegian population are non-European (Statistics Norway Citation2019a). Since the nineties, there have been increased demands for both immigrants and native Norwegians on benefits to be involved in the labour market (Kavli, Hagelund, and Bråthen Citation2007). This shift has become apparent in integration efforts, possibly most obviously in NIP (Djuve Citation2014). According to Djuve and Kavli (Citation2007), integration policy shows a gradual move towards the obligation of immigrants to participate in society and working life. The underlying assumption that qualifications are the core remedy for lack of participation in working life has made its way into the politics of integration (Djuve Citation2014; Djuve and Kavli Citation2007; Kavli, Hagelund, and Bråthen Citation2007). Halvorsen (Citation2012) claims that workfare policies, aimed at integration fail to help the most vulnerable immigrants into employment, thus bringing the workfare focus on gainful employment into question. Kildal (Citation2012) suggests that negative incentives are directed towards those in greatest need of assistance.

Integration

Integration is subject to multiple definitions (Brochmann Citation2010; Brochmann, Hagelund, and Borevi Citation2010; Djuve and Tronstad Citation2011.; Garcés-Mascareñas and Penninx Citation2016; Harder et al. Citation2018; Oliver and Gidley Citation2015). Djuve (Citation2014) suggested that the apparent consensus on the need for integration disguises substantial disagreement about what integration really is, who is responsible for realizing it and what measures could and should be used to accomplish it. The perception of work as a central aspect in human life is shared across cultural and national borders (Shenoy-Packer and Gabor Citation2016). According to Shenoy-Packer and Gabor (Citation2016) the meaning of work for immigrants is an area overlooked in research.

Research on work and integration generally perceives integration to be synonymous with integration in the labour market (Garcés-Mascareñas and Penninx Citation2016; Harder et al. Citation2018; Oliver and Gidley Citation2015). Several scholars propose, however, that association with the labour market is only part of integration (e.g. Craig Citation2015; Ott, Citation2013). Age, country of origin, socio-economic background, quality of living conditions, discrimination, context, and policy all matter and are all relevant for facilitating and achieving integration (Craig Citation2015). Obstacles, such as growing discrimination and racism, an exaggerated focus on rapid – rather than lasting – transition into the labour market, as well as a tendency to view integration as an activity with an endpoint can impede integration (Craig Citation2015).

According to Lewis et al. (Citation2014) immigrants originating from the global south have substantially less favourable options in the labour market in the global north. Immigrants from Europe also experienced far worse working conditions than native workers and suffered discrimination and lower outcomes in the labour market (Johnston, Khattab, and Manley Citation2015). An evaluation of active labour market programmes (ALMPs) concluded that wage subsidies were the only measure fit to be recommended to European policymakers (Butschek and Walter Citation2014). Nevertheless, immigrants considered work important for integration (Matejskova Citation2013).

Cultural competence and dialogism

Social work faces growing diversity and consequences of migration such as trauma and displacement, daily (Käkelä Citation2020). Cultural competence emerged ‘ … as a consequence of and response to challenges social workers experience when working with people with minority ethnic backgrounds’ (Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019, 2). This perspective is prominent yet contested in social work practice (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Käkelä Citation2020; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019).

Käkelä (Citation2020) revealed that social workers considered knowledge of culture insufficient. Structural parameters constrained social works’ ability to address inequalities, differences and disadvantages experienced by immigrants (Käkelä Citation2020). Garran and Rozas (Citation2013) advocated that cultural competence would benefit from including intersectionality. They proposed focus on power and privilege to ensure an enhanced view on cultural competence (Garran and Rozas Citation2013). Nadan (Citation2017) called for ‘critical, reflective and socially committed practitioners’ (p 81). Furthermore, Nadan (Citation2017) encouraged critical reflectivity to challenge assumptions, attitudes, and images of ‘the other’. According to Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker (Citation2019), in Norway (and Scandinavia) the cultural competence discourse in social work lacked a critical perspective on culturalization. Social work’s understanding of work with immigrants must recognize the importance of class, gender, ethnicity, and power relations (Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). Consequently, intersectionality should be at the forefront (Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). Cultural competence should acknowledge power relations, inequality, and disadvantages explicitly (Käkelä Citation2020; Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019).

Dialogism offers an alternative framing of problems, interaction and understanding in traditionally asymmetrical fields such as social work (Irving and Young Citation2002). According to Bakhtin (Citation1981), to seek harmony and consensus is irrational, and utterly pointless. Within a dialogic framework, differences are not a threat but an opportunity to increase ones understanding (Bakhtin Citation1984). Irving and Young (Citation2002) propose that dialogism can provide an alternative frame for working with diversity in social work.

On this backdrop, the research question guiding this review is: What knowledge on the association between work and integration is described in previous research about the Norwegian welfare context?

Method

To respond to the research question, I used a systematic integrative review [IR] methodology. This systematic integrative review aimed for a holistic understanding of work and integration. IR was chosen as it allowed inclusion of both empirical and theoretical data, as well as different methodologies (Whittemore and Knafl Citation2005). Contemporary knowledge from existing literature was summarized and a synthesis of ongoing understandings was produced to identify knowledge gaps (Whittemore and Knafl Citation2005). A systematic and rigorous approach ensured robust and reliable summaries of the topic (Whittemore and Knafl Citation2005).

Search strategy, criteria, and approach

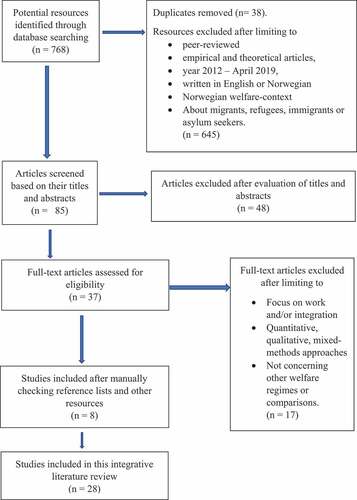

To ensure accurate results from relevant databases, a systematic and explicit literature search strategy was developed and carried out (). A comprehensive computer search in the four databases Scopus, Academic Search Premier, Soc Index and Idunn, as well as the search engine Oria was conducted ().

Table 1. Keywords in computer search.

Explicit predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were outlined to provide a consistent approach to the review of the literature (see ). Articles concerning other welfare regimes or comparisons, articles discussing work in relation to objectives other than integration were excluded to ensure a persistent focus throughout the IR. Furthermore, articles not concerning migrants, immigrants, asylum-seekers, or refugees were excluded.

Quality appraisal/assessment of studies included in the review

An appraisal of the studies was conducted, following the guidelines for evaluating quantitative and qualitative research methods advocated by Gray and Grove (Citation2017). A synthesis of the articles’ bibliographical details, scope of investigation, method, data collection, sample, and research methods as well as findings was generated (). 67.9% of the studies (1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 25, 26) were quantitative. Studies 2, 3, 8, 15, 18, 22, 24, 27 and 28 were qualitative.

Table 2. Overview of the articles included in the integrative review.

Other than in papers 18 and 22, ethical considerations were not stated. Several papers (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 18, 19, 20, 24, 26) discussed limitations. Topics were related to sample, methodological biases, possibility of biased replies and unobserved characteristics. Papers 1, 5, 7, 19, 23 and 25 conducted checks of robustness and sensitivity. Recommendations or implications for policy were stated in several papers (3, 5, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 25, 27). None of the included studies problematized the association between work and integration.

Analytical approach

A reflexive thematic analysis in line with Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2019) was carried out, following six steps.

Step 1. Familiarization with the data. The content of all papers was read thoroughly and summarized.

Step 2. Generating initial codes. Whilst familiarizing myself with the data, I noted initial codes, keeping the topic of the review in mind.

Step 3. Searching for themes. The codes were separated with colours and subsequently grouped together. An exhaustive list of codes was developed into themes.

Step 4. Reviewing themes. I used a sheet of paper to draw up the thematic map, to visually depict connections. The illustration provided an opportunity to evaluate the themes, check whether initial codes were included and possibly identity insufficiencies. This analytical step required repeated assessments of the data. Themes and sub-themes were reviewed and refined to give a comprehensive and accurate illustration of the data. Themes were checked against the complete dataset, to assess whether major themes were missing from the coding and to assess eligibility regarding themes and the overall story.

Step 5. Defining and naming themes. The themes that were identified are (1) Employment and outcome for immigrants in the Norwegian labour market, (2) Immigrant women – participation and equality, (3) Discrimination in Norwegian working life, and (4) Possible solutions and challenges ahead.

Step 6. Producing the report.

Limitations

There are limitations to this integrative review. By using the combination work AND integration I may have excluded some studies. Inclusion of studies comparing Norway and other countries could have captured additional themes. Nevertheless, by using specific keywords I identified a variety of articles.

The empirical data included in this review rests on uneven samples: differing groups of immigrants, young immigrants, and descendants. Differing samples may, in fact, add to the strength of the results as they incorporate a variety of groups.

A lack of information about personal preferences and choices decontextualized the experiences of immigrants. The aim of this paper, however, is to consider the association between integration and work in the Norwegian welfare context, rather than subjective experiences. Individual experiences and context ought to be researched to corroborate or challenge the results of this study.

Epistemological position and the author’s training as a social worker may have influenced the research. Reflexivity, epistemological as well as personal, guided the work to counteract bias. Despite its limitations, I believe that this paper adds to the knowledge on work and integration and is particularly relevant for social work practice.

Results

Employment and outcome for immigrants in the Norwegian labour market

Throughout the dataset, access to the labour market was identified as a major obstacle (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018: Eide et al. Citation2017; Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2018; Godøy Citation2017; Kavli and Nicolaisen Citation2016; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Non-European immigrants more frequently had trouble securing a stable connection with the labour market than European immigrants (Barth, Bratsberg, and Raaum Citation2012; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018; Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2018; Godøy Citation2017). Individual characteristics as well as their country of origin and host country affected the outcome and adaption to the Norwegian labour market (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018; Kavli Citation2015; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018). Non-European immigrants seemed to have less job mobility and tended to stay in low-paying segments of the labour market (Barth, Bratsberg, and Raaum Citation2012; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2018; Friberg and Midtbøen, Citation2018; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018).

The initial positive and rapidly growing access to the labour market and inclusion in the workforce was followed by fading attachment, accompanied by rising social security dependency (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017). Even though immigrants managed to secure their first job, there was a comprehensive exclusion from the labour market resulting in shorter careers and less favourable outcomes (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). Scarring effects from job loss negatively affected immigrants’ attachment to the labour market, and even affected work integration in the long run (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2018).

Immigrant women – participation and equality

Immigrant women’s participation in working life was recognized as the solution to poverty and socio-economic differences (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Kavli Citation2015; Kavli and Nicolaisen Citation2016; Røysum Citation2016). Their participation in the workforce was perceived as a pre-requisite for gender equality as well as essential to uphold the egalitarian welfare-state (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Røysum Citation2016). However, immigrant women were at the same time perceived as a problem because of an insecure attachment to working life that appeared to elevate their risk of exiting the labour market (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Kavli and Nicolaisen Citation2016; Røysum Citation2016).

Native Norwegian women’s preferences were interpreted as freedom of choice whereas gender inequality and suppressive cultural traditions were assumed to motivate immigrant women’s lack of participation in the workforce (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Røysum Citation2016). A focus on individual responsibility downplayed the barriers which prevent immigrant women participating in the workforce, suggesting lacking will to work as the main reason for low participation (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Røysum Citation2016).

Discrimination in Norwegian working life

Discrimination was noticeable in Norwegian working life (Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Birkelund et al. Citation2019; Fangen and Paasche Citation2013; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Explorations of ethnic discrimination revealed a stable and consistent occurrence (Birkelund et al. Citation2019; Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Midtbøen Citation2016).

Ethnic discrimination had a documented scarring effect of unemployment (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Legal status and country of origin were significant indicators for (level of) discrimination (Barth, Bratsberg, and Raaum Citation2012; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014; Friberg and Midtbøen, Citation2018; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018).

Descendants experienced discrimination when transitioning into the labour market (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Hermansen Citation2013; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Although fluent in Norwegian, and with educational qualifications equal to those of native Norwegians, descendants were judged by stereotypes originating from their parents’ generation (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Birkelund et al. Citation2014b; Hermansen Citation2013; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016).

Education counteracted discrimination by increased probability of gained employment (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014; Hermansen Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Midtbøen Citation2014). There was still a systematic and unreasonable bias in favour of applicants with typical Norwegian names, and a systematic discrimination against applicants with ‘foreign’ names (Birkelund et al. Citation2019, Citation2014b).

Possible solutions and challenges ahead

Current measures seemed unable to strengthen immigrants’ insecure attachment to the labour market (Annfelt and Gullikstad Citation2013; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019; Drange and Telle Citation2015; Eide et al. Citation2017; Godøy Citation2017; Hermansen Citation2017a; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018; Midtbøen Citation2016; Røysum Citation2016). A different set of measures would be required to secure employment, counteract early immigrant job loss, and secure a stable and lengthy relationship with the workforce (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019; Eide et al. Citation2017).

Knowledge of the importance of education as a facilitator for employment did not result in enhanced focus on formal education (Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019; Hermansen Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2017a; Midtbøen Citation2014)

Various approaches and solutions designed to facilitate access to the labour market were launched. Providing assisted jobs with more flexible combinations of work and social security or long-term wage subsidies were suggested as possible solutions (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). Furthermore, more intensive investment in human capital (Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019; Hermansen Citation2017a), and opportunities to demonstrate skills as well as opportunities to gain access through social networks (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a).

A need to change the initiatives or measures to secure a different outcome seemed to be a prevailing conclusion (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). However, promotion of measures that combined early entry into the labour market with positive outcomes in the long run appeared to be a challenge in the association between work and integration (Eide et al. Citation2017; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019).

Discussion

Integration looms large on the political agenda. This integrative review aimed to clarify major themes in this field, provide a synthesis of current understandings, and consider implications for social work practice. The findings in this study showed that immigrants from high-income countries had similar adaption to working life as native Norwegians did (Barth, Bratsberg and Raaum, Citation2012; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). Hence, this discussion particularly focuses on immigrants from countries outside Europe. The research question ‘What knowledge on the association between work and integration is described in previous research about the Norwegian welfare context?’ guided the discussion.

Compelling support for the perception that integration is best achieved through work was prevalent in the findings. It could therefore appear that integration can only be achieved through work (Halvorsen Citation2012; Kildal Citation2012). Halvorsen (Citation2012) and Kildal (Citation2012) both insisted that this idea was too narrow. According to the findings, immigrants and their descendants faced major hurdles when entering the labour market (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018: Eide et al. Citation2017; Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2018; Godøy Citation2017; Kavli and Nicolaisen Citation2016; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Immigrants were more prone to expulsion from the labour market, resulting in an increasing gap between immigrants and natives (Barth, Bratsberg, and Raaum Citation2012). Short careers, accompanied by transitions into social security dependency, contributed to a comprehensive exclusion from the labour market (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). Interpreting these findings within a cultural competence framework might conclude that the immigrants’ otherness left them vulnerable to exclusion (e.g. Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018), downsizing (e.g. Barth, Bratsberg, and Raaum Citation2012) or discrimination (e.g. Fangen and Paasche Citation2013; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Cultural competence could also focus on structural disadvantages, lacking privileges and accumulated power within the structural framework (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Käkelä Citation2020; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). The framing and interpretation of the findings must reach beyond individuals to capture built-in disadvantages, inequality and lacking privileges experienced by immigrants.

NIP aimed to ensure that immigrants gain adequate qualifications to move successfully into the labour market (Djuve and Kavli Citation2007, Citation2019; Kavli, Hagelund, and Bråthen Citation2007). However, not all immigrants were entitled to participate in the introductory schemes, nor did participation guarantee employment (Halvorsen Citation2012; Kildal Citation2012). My findings raised the question whether prioritizing early access into the workforce conflicts with the aim of forming stable and lasting attachment to the labour market. This needs further exploration. Recent adjustments in policy focused more on sanctions and behavioural control, and less on evaluating programmes which were supposed to ensure swift and stable transitions into the labour market (Djuve and Kavli Citation2019). According to Djuve and Kavli (Citation2019), new measures and initiatives established to promote integration emphasized the need for immigrants to be active in the integration process. Thus, shifting the responsibility for success to individual immigrants. I suggest that the assumption that behavioural measures would initiate positive outcomes rests on a hypothesis that immigrants were making too little effort. This assumption depended on mistrust towards immigrants’ will to integrate. A dialogic approach could redirect how differences are framed and instead focus on understanding and incorporating different perspectives.

The findings suggested a need to change current measures to reach a stable employment rate closer to that of native Norwegians (e.g. Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018; Djuve and Kavli Citation2019; Røysum Citation2016). Education and acquisition of human capital were recognized as important facilitators for successful entry into the labour market, as well as ways to counteract discrimination and gain occupational attainment (Birkelund, Heggebø, and Rogstad Citation2017; Birkelund et al. Citation2014b; Hermansen Citation2016, Citation2017a; Midtbøen Citation2014). An important political move to support integration and counteract bias in recruitment might therefore be to facilitate immigrants’ access to more education (Birkelund et al. Citation2014a). Knowledge about the importance of formal education (Birkelund et al. Citation2014a; Hermansen Citation2013, Citation2017a) has not yet resulted in policy changes (Djuve and Kavli Citation2019).

Common ideas about the association between integration and work have so far failed to secure lasting inclusion in the labour market for many immigrants. My findings did not support the idea that stronger emphasis on workfare, accompanied by economic incentives was sufficient to ensure integration into the labour market. Accepting that integration includes fulfilment (Harder et al. Citation2018), the association between work and integration transcends the narrow perception of integration as work and must be widened. As the problem of integration is framed in a discourse of otherness, intersectional differences as well as structural disadvantages are downplayed. I propose that a stronger focus on cultural competence, acknowledging intersectionality, could advance a wider perspective by recognizing that immigrants encounter difficulties beyond their ‘otherness’.

Conclusions and implications for social work practice

This review showed that immigrants and their descendants faced human and structural barriers when transitioning into the labour market (Badwi, Ablo, and Overå Citation2018; Birkelund et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018: Eide et al. Citation2017; Friberg and Midtbøen Citation2018; Godøy Citation2017; Kavli and Nicolaisen Citation2016; Larsen, Rogne, and Birkelund Citation2018; Midtbøen Citation2014, Citation2016). Such barriers challenge social works’ foundation – solidarity with marginalized groups, fighting against poverty and working towards social justice and social change. It might serve as an example of what Jönsson (Citation2014) refers to as the tension between practice in the welfare state and ethical principles in social work.

Social work practitioners have first-hand knowledge of immigrants’ struggles (Käkelä Citation2020). The profession is practice-oriented and can nuance the prevailing image of immigrants as a problem by pertaining a suitable framework (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). Coming from a social work background myself, my position is that immigrants’ subjective experiences must be included. This can be achieved by facilitating approaches and methods that regard diversity and pluralism as assets rather than problems (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Irving and Young Citation2002; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019). Social works ethical principles (e.g. social justice, human rights) require a professional practice rooted in cultural competence. Structural issues must be acknowledged by social work(ers) while striving for critical reflection to challenge assumptions, images, and attitudes of ‘the other’ (Garran and Rozas Citation2013; Nadan Citation2017; Rugkåsa and Ylvisaker Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Annfelt, T., and B. Gullikstad. 2013. “Kjønnslikestilling I Inkluderingens Tjeneste?” Tidsskrift for kjønnsforskning 37 (3–4): 309–328. doi:10.18261/1891-1781-2013-03-04-06.

- Badwi, R., A. D. Ablo, and R. Overå. 2018. “The Importance and Limitations of Social Networks and Social Identities for Labour Market Integration: The Case of Ghanaian Immigrants in Bergen, Norway.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 72 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1080/00291951.2017.1406402.

- Bakhtin, M. 1981. The Dialogic Imaginaton. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Barth, E., B. Bratsberg, and O. Raaum. 2012. “Immigrant Wage Profiles within and between Establishments.” Labour Economics 19 (4): 541–556. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.009.

- Birkelund, G. E., T. W. Chan, E. Ugreninov, A. H. Midtbøen, J. Rogstad. 2019. “Do Terrorist Attacks Affect Ethnic Discrimination in the Labour Market? Evidence from Two Randomized Field Experiments.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (1): 241–260. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12344.

- Birkelund, G. E., K. Heggebø, and J. Rogstad. 2017. “Additive or Multiplicative Disadvantage? the Scarring Effects of Unemployment for Ethnic Minorities.” European Sociological Review 33 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1093/esr/jcw030.

- Birkelund, G. E., M. Lillehagen, V. P. Ekre, E. Ugreninov. 2014a. “Fra utdanning til sysselsetting - En forløpsanalyse av indiske og pakistanske etterkommere i Norge.” Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning 55 (4): 386–414. https://www.idunn.no/tfs/2014/04/fra_utdanning_til_sysselsetting__en_forloepsanalyse_av_indi

- Birkelund, G. E., J. Rogstad, K. Heggebø, T. M. Aspøy, H. F. Bjelland. 2014b. “Diskriminering i arbeidslivet - Resultater fra randomiserte felteksperiment i Oslo, Stavanger, Bergen og Trondheim.” Sosiologisk tidsskrift 22 (4): 352–382. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283509647_Diskriminering_i_arbeidslivet_-_Resultater_fra_randomiserte_felteksperiment_i_Oslo_Stavanger_Bergen_og_Trondheim

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. 2014. “Immigrants, Labour Market Performance and Social Insurance.” The Economic Journal 124 (580): F644–F683. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12182.

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. 2016. “Flyktninger på det norske arbeidsmarkedet.” Søkelys på arbeidslivet 32 (3): 185–207. doi:10.18261/.1504-7989-2016-03-01.

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. (2017). “Immigrant Labor Market Integration Across Admission Classes.” Nordic Economic Policy Review: 17–54.

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. 2018. “Job Loss and Immigrant Labour Market Performance.” Economica 85 (337): 124–151. doi:10.1111/ecca.12244.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Breidahl, K. N. 2017. “Scandinavian Exceptionalism? Civic Integration and Labour Market Activation for Newly Arrived Immigrants.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (2). doi:10.1186/s40878-016-0045-8.

- Brochmann, G. 2010. “Innvandring og det flerkulturelle Norge.” In Det norske samfunn. 6thed., edited by I. Frønes and K. L, 435–456. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Brochmann, G., and A. Hagelund. 2011. “Migrants in the Scandinavian Welfare State: The Emergence of a Social Policy Problem.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 1 (1): 13–24. doi:10.2478/v10202-011-0003-3.

- Brochmann, G., A. Hagelund, and K. Borevi. 2010. Velferdens grenser: Innvandringspolitikk og velferdsstat i Skandinavia 1945-2010. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Butschek, S., and T. Walter. 2014. “What Active Labour Market Programmes Work for Immigrants in Europe? A meta-analysis of the Evaluation Literature.” IZA Journal of Migration 3 (48). doi:10.1186/s40176-014-0023-6.

- Craig, G. (2015) Migration and Integration: A Local and Experiential Perspective. IRIS Working Paper Series, NO. 7/2014. Birmingham: Institute for Research into Superdiversity

- Djuve, A. B. 2014. Integrering av innvandrere i Norge, 27. Vol. 2014. Tøyen: Fafo.

- Djuve, A. B., and H. C. Kavli. 2007. “Integreringspolitikk i endring.” In Hamskifte. Den norske modellen i endring, edited by J. E. Dølvik, Fløtten , T, Hernes, G, Hippe, J.M., 195–218. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Djuve, A. B., and H. C. Kavli. 2019. “Refugee Integration Policy the Norwegian Way – Why Good Ideas Fail and Bad Ideas Prevail.” Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 25 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1177/1024258918807135.

- Djuve, A. B., and K. R. Tronstad. 2011. Innvandrere i praksis. Om likeverdig tjenestetilbud i NAV. 2011:7. Tøyen: Fafo. Fafo 2011:7

- Drange, N., and K. Telle. 2015. “Promoting Integration of Immigrants: Effects of Free Childcare on Child Enrollment and Parental Employment.” Labour Economics 34: 26–38. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.006.

- Eide, H. M. K., A. Homme, M.-A. Karlsen, K. Lundberg. 2017. “Omsorgssektoren som integreringsarena.” Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning 20 (4): 332–348. doi:10.18261/.2464-3076-2017-04-06.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fangen, K., and E. Paasche. 2013. “Young Adults of Ethnic Minority Background on the Norwegian Labour Market: The Interactional co-construction of Exclusion by Employers and Customers.” Ethnicities 13 (5): 607–624. doi:10.1177/1468796812467957.

- Friberg, J. H., and A. H. Midtbøen. 2018. “Ethnicity as Skill: Immigrant Employment Hierarchies in Norwegian low-wage Labour Markets.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (9): 1463–1478. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1388160.

- Garcés-Mascareñas, B., and R. Penninx. 2016. “Introduction: Integration as a Three-Way Process Approach?” In Integration Processes and Policies in Europe. IMISCOE Research Series, edited by B. Garcés-Mascareñas and R. Penninx, 1–9. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Garran, A. M., and L. W. Rozas. 2013. “Cultural Competence Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work 22 (2): 97–111. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.785337.

- Godøy, A. 2017. “Local Labor Markets and Earnings of Refugee Immigrants.” Empirical Economics 52 (1): 31–58. doi:10.1007/s00181-016-1067-7.

- Gray, J. R., and S. K. Grove. 2017. “Critical Appraisal of Nursing Studies.” In Burns and Grove’s the Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence, edited by J. R. Gray, S. K. Grove, and S. Sutherland, 670–709. 8th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Hagelund, A. 2020. “After the Refugee Crisis: Public Discourse and Policy Change in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.” Comparative Migration Studies 8 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s40878-019-0169-8.

- Halvorsen, K. 2012. “Lønnsarbeidet - vår tids sekulære religion.” In Arbeidslinja. Arbeidsmotivasjonen Og Velferdsstaten, edited by S. Stjernø and E. Øverbye, 188–198. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Harder, N., Figueroa, L., Gillum, R. M., Hangartner, D., Laitin, D.D. (2018) Multidimensional Measure of Immigrant Integration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1808793115.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2013. “Occupational Attainment among Children of Immigrants in Norway: Bottlenecks into Employment - Equal Access to Advantaged Positions?” European Sociological Review 29 (3): 517–534. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr094.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2016. “Moving up or Falling Behind? Intergenerational Socioeconomic Transmission among Children of Immigrants in Norway.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 675–689. doi:10.1093/esr/jcw024.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2017a. “Age at Arrival and Life Chances among Childhood Immigrants.” Demography 54 (1): 201–229. doi:10.1007/s13524-016-0535-1.

- Hermansen, A. S. 2017b. “Et egalitært og velferdsstatlig integreringsparadoks?” Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift 1 (1): 15–34. doi:10.18261/.2535-2512-2017-01-02.

- Hernes, V. 2018. “Cross-national Convergence in Times of Crisis? Integration Policies Before, during and after the Refugee Crisis.” West European Politics 41 (6): 1305–1329. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1429748.

- Hernes, V., Arendt, J.N, Joona, P.A., Tronstad, K.R. 2019. “Nordic Integration and Settlement Policies for Refugees: A Comparative Analysis of Labour Market Integration Outcomes.” TemaNord, Vol. 529. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.10.6027/TN2019-529

- Holmes, S. M., and H. Castañeda. 2016. “Representing the “European Refugee Crisis” in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death.” American Ethnologist 43 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1111/amet.12259.

- International Organization for Migration. 2018. World Migration Report 2018. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Irving, A., and T. Young. 2002. “Paradigm for Pluralism: Mikhail Bakhtin and Social Work Practice.” Social Work 47 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1093/sw/47.1.19.

- Jensen, K., and P. Mouritsen. 2017. “The Civic Turn of Immigrant Integration Policies in the Scandinavian Welfare States.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (9). doi:10.1186/s40878-017-0052-4.

- Johnston, R., N. Khattab, and D. Manley. 2015. “East versus West? Over-qualification and Earnings among the UK’s European Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (2): 196–218. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.935308.

- Jönsson, J. H. 2014. “Local Reactions to Global Problems: Undocumented Immigrants and Social Work.” The British Journal of Social Work 44 (suppl_1,1): i35–i52. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu042.

- Käkelä, E. 2020. “Narratives of Power and Powerlessness: Cultural Competence in Social Work with Asylum Seekers and Refugees.” European Journal of Social Work 23 (3): 425–436. doi:10.1080/13691457.2019.1693337.

- Kavli, H. C. 2015. “Adapting to the Dual Earner Family Norm? the Case of Immigrants and Immigrant Descendants in Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (5): 835–856. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.975190.

- Kavli, H. C., A. Hagelund, and M. Bråthen. 2007. Med rett til å lære og plikt til å delta: En evaluering av introduksjonsordningen for nyankomne flyktninger og innvandrere, 34. Tøyn: Fafo.

- Kavli, H. C., and H. Nicolaisen. 2016. “Integrert Eller Marginalisert? Innvandrede Kvinner I Norsk Arbeidsliv.” Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning 57 (4): 339–371. doi:10.18261/.1504-291X-2016-04-01.

- Kildal, N. 2012. “Fra arbeidsetos til insentiver og velferdskontrakter.” In Arbeidslinja. Arbeidsmotivasjonen Og Velferdsstaten, edited by S. Stjernø and E. Øverbye, 177–187. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Knutsen, H., K. Fangen, O. Žabko . 2019. “Integration and Exclusion at Work: Latvian and Swedish Agency Nurses in Norway.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 20 (3): 769–786. doi:10.1007/s12134-019-00660-5.

- Larsen, E. N., A. F. Rogne, and G. E. Birkelund. 2018. “Perfect for the Job? Overqualification of Immigrants and Their Descendants in the Norwegian Labor Market.” Social Inclusion 6 (3): 78–103. doi:10.17645/si.v6i3.1451.

- Lewis, H., P. Dwyer, S. Hodkinson, L. Waite. 2014. “Hyper-precarious Lives: Migrants, Work and Forced Labour in the Global North.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (5): 580–600. doi:10.1177/0309132514548303.

- Lucassen, L. 2018. “Peeling an Onion: The “Refugee Crisis” from a Historical Perspective.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (3): 383–410. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1355975.

- Marthinsen, E. 2011. “Social Work Practice and Social Science History.” Social Work and Social Sciences Review 15 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1921/095352211X604291.

- Marthinsen, E. 2014. “Social Work at Odds with Politics, Values and Science.” In Social Change and Social Work: The Changing Societal Conditions of Social Work in Time and Place, edited by T. Harrikari, P. L. Rauhala, and E. Virokannas, 31–47. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing limited.

- Matejskova, T. 2013. ““But One Needs to Work!”: Neoliberal Citizenship, Work-Based Immigrant Integration, and Post-Socialist Subjectivities in Berlin-Marzahn.” Antipode 45 (4): 984–1004. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01050.x.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2014. “The Invisible Second Generation? Statistical Discrimination and Immigrant Stereotypes in Employment Processes in Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (10): 1657–1675. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2013.847784.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2016. “Discrimination of the Second Generation: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Norway.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 17 (1): 253–272. doi:10.1007/s12134-014-0406-9.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2017. “Innvandringshistorie som faghistorie: Kontroverser i norsk migrasjonsforskning.” Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 2 (34): 130–149. doi:10.18261/.1891-1781-2017-02-03.

- Nadan, Y. 2017. “Rethinking ‘Cultural Competence’ in International Social Work.” International Social Work 60 (1): 74–83. 2017:2. doi:10.1177/0020872814539986NOU.

- NOU. 2011. 7 Velferd og migrasjon. Den norske modellens framtid. Oslo: Barne-, likestillings - og inkluderingsdepartementet.

- NOU2017:2: Integrasjon og tillit - Langsiktige konsekvenser av høy innvandring.Oslo: Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet

- Oliver, C., and B. Gidley (2015) Integration of Migrants in Europe. Available at: https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/OSIFE15-Report.pdf.

- Ott, E. 2013. The Labour Market Integration of Resettled Refugees. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Potocky, M., and M. Naseh. 2019. Best Practices for Social Work with Refugees and Immigrants. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Prop. Nr 90 L (2015 – 2016) Endringer i utlendingsloven mv (innstramminger 2) (bill)

- Rheindorf, M., and R. Wodak. 2018. “Borders, Fences, and Limits—Protecting Austria from Refugees: Metadiscursive Negotiation of Meaning in the Current Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1–2): 15–38. doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1302032.

- Røysum, A. 2016. “Arbeidsmoral forkledd som likestilling?” Søkelys på arbeidslivet 33 (1–2): 142–161. doi:10.18261/.1504-7989-2016-01-02-08.

- Rugkåsa, M., and S. Ylvisaker. 2019. “From Culturalization to Complexity – A Critical View on the Cultural Competence Discourse in Social Work.” Nordic Social Work Research. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2019.1690558.

- Sandvin, J. T., H. Vike, and C. H. Anvik. 2020. “Den norske og nordiske velferdsmodellen – Kjennetegn og utfordringer.” Velferdstjenestenes vilkår: Nasjonal politikk og lokale erfaringer , edited by, I. C. H. Anvik, J. T. Sandvin, J. P. Breimo, and Ø. Henrisken, 28-41. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. doi:10.18261/9788215034713-2020-3.

- Shenoy-Packer, S., and G. E, eds. 2016. Immigrant Workers and Meanings of Work: Communicating Life and Career Transitions. New York: Peter Lang.

- Statistics Norway. (2019a). “Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre.” Available at: https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef/aar/2019-03-05 (accessed 28 February 2020).

- Statistics Norway. (2019b). “Sysselsetting blant innvandrere.” accessed 21 February 2020. https://www.ssb.no/arbeid-og-lonn/statistikker/innvregsys/aar/2019-03-05

- United Nations (2017) Making Migration Work for All; Report of the Secretary-General. United Nations. Available at: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/sg_report_en.pdf.

- Whittemore, R., and K. Knafl. 2005. “The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 52 (5): 546–553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

- World Health Organization. 2019. Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants: Draft Global Action Plan, 2019 - 2023. Geneva: WHO.