ABSTRACT

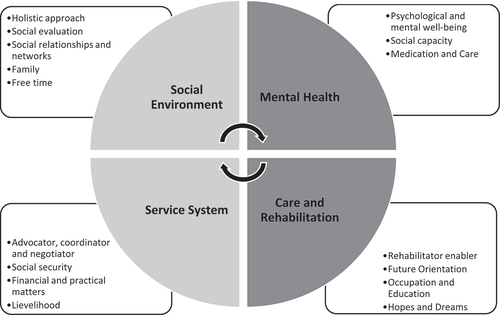

Psychosocial social work is usually defined as a holistic approach and therefore it is unclear how it should be structured in psychiatric outpatient care. This study aimed to clarify the framework of psychosocial social work as a part of interdisciplinary collaboration and care need assessment. The research data were gathered from two different sources: three focus group interviews in adolescent psychiatry and two video-recorded care consultations and reflection discussions in adult psychiatry. A total of seven doctors, five nurses and five social workers and one client participated in the study. This study examined how psychosocial social work is described by different occupational groups, and how psychosocial social work appears in psychiatric outpatient care as a part of the client’s care needs assessment and reflection discussions by an interdisciplinary team (IDT). The data-driven content analysis was used in analysing the data. In this study, psychosocial social work comprises four perspectives: Social Environment, Mental Health, Service System and Care and Rehabilitation. Perspectives affect an assessment in which the social worker plays an important role as a part of interdisciplinary collaboration. The perspectives describe and set a structure for a professional framework for psychosocial social work in psychiatry. According to this study, psychosocial social work involves forming a comprehensive understanding of the client’s psychological and mental well-being and the impact these have on social performance. It also includes the core perspectives of social work in assessing the client’s social environment and the need for comprehensive support and referring clients to relevant services.

Introduction

The term ‘psychosocial’ refers to experiences formed by an interaction between the individual’s psychological capabilities and the social environment (Adams, Dominelli, and Payne Citation2009). Social work in health care is commonly described as psychosocial social work (see, e.g. Gunningham and Booth Citation2008; Segal Citation2014) and is based on human holism (see, e.g. Venkat and Abraham Citation2014). According to previous studies, a psychosocial work orientation can be considered a basic trend in social work orientation and a part of the social work paradigm. Psychosocial orientation is described as an orientation that combines therapeutic and psychological work, taking into account the psychological, biological and social needs of a person (see, e.g. Adams, Dominelli, and Payne Citation2009; Woods and Robinson Citation1996). According to Granfelt (Citation1993), a psychosocial orientation in social work emphasizes certain characteristics, such as a therapeutic work approach, a commitment to working with marginalized people, and an aim to structure psychological understanding and knowledge base in the process. Bower (Citation2005) describes the social work carried out at outpatient clinics as a kind of psychosocial expert work that emphasizes understanding the client’s internal and external situation through psychoanalytic and psychosocial theory.

In health care teams, social workers provide psychosocial assessments and interventions, complete comprehensive risk assessments, psychotherapy as well as other types of counselling, make referrals to community resources, support medical provider interventions, conduct health promotion activities, engage in systems navigation and care coordination, providing ongoing case management, improving relationships between the medical provider and the patient, assist in team building and, at times, support the education and training of other healthcare providers (Ashcroft et al. Citation2018; Horevitz and Manoleas Citation2013; McGregor, Mercer, and Harris Citation2018; Sverker et al. Citation2017).

Indeed, the psychosocial expertise of social work in mental health services consists of various psychosocial work practices such as evaluation, development of work with clients and interface work (Adams, Dominelli, and Payne Citation2009; Horevitz and Manoleas Citation2013) and interventions (Wodarski John and Feit Marvin Citation2009), whose aim is to strengthen the patient’s overall functional capacity. In mental health services, an evaluation of the client’s overall situation carried out by social workers is used to assess the patient’s need for services Muralidhar et al. (Citation2012); Korpela (Citation2014); Corcoran and Walsh (Citation2016) and implementation of services.

In health care, the psychosocial approach is part of the work of all occupational groups involved in interdisciplinary collaboration. Several studies have looked at interdisciplinary teamwork from an investigatory perspective, examining the roles and tasks of different professions and the collaboration between them. Dugan Day (Citation2012) studied pain management provided by an IDT (an interdisciplinary team) and found that the primary focus and treatment recommendations in IDT meetings were medical, even though the team members individually recognized the psychosocial components of pain and pain management. Wittenberg-Lyles (Citation2005) studied the process of introducing psychosocial information to interdisciplinary meetings and found that this was rarely accomplished and primarily used to provide explanations for medical issues. Studies have also found that IDT meetings tend to be led by physicians, medical staff are most vocal during team meetings, and social work and spiritual care staff scarcely contribute (Atwal and Caldwell Citation2005; Dugan Day Citation2012; Wittenberg-Lyles Citation2005). The relationships of power and responsibility between different professions and the key role of cooperation have also been widely recognized (see e.g. Bronstein Citation2003; Frost Citation2005).

From the point of view of psychiatric social work, the psychosocial concept aimed at combining social science and psychological knowledge is relevant, but also involves various kinds of tensions and deficiencies (Leinonen Citation2020). In an interdisciplinary collaboration, the social worker is responsible for ensuring the patient’s social well-being and taking it into account when assessing the client’s need for care (e.g. Frost Citation2005; Gagle et al. Citation2017). Interdisciplinary communities can have a consensus, democracy or hierarchy or a combination of these depending on the circumstances (Judith, Pollard, and Sellman Citation2014) and this also affects how psychosocial social work is structured and appear as part of interdisciplinary collaboration (Arajärvi et al. Citation2021).

As mentioned above, psychosocial social work is usually described in a wide-ranging, holistic approach and therefore it is not quite clear how psychosocial social work should be structured in outpatient care in psychiatry. In this study, psychosocial work is a cross-cutting concept that combines a psychological and mental approach to other social work tasks and roles, such as assessing the client’s social environment and supporting rehabilitation. The purpose of this study is to clarify the framework of psychosocial social work as a part of interdisciplinary collaboration and care need assessment in psychiatric outpatient care. The care need assessment is an important form of interdisciplinary collaboration in psychiatry.

The research questions in this study are as follows:

How psychosocial social work is described in psychiatric outpatient care as a part of an interdisciplinary collaboration?

How does psychosocial social work appear in psychiatric outpatient care as a part of the care needs assessment and reflection discussions by an interdisciplinary team?

Materials and methods

Study design

The study data were gathered from two outpatient care providers: The focus group interviews of professionals (a social worker, nurses and doctors) were carried out in adolescent psychiatry in 2018 and the video-recorded care consultations in adult psychiatry in 2016. The data sets were collected from different organizations and in different years, but time was not a relevant factor for the analysis.

Both of the data sets concern psychiatric outpatient care context and the same occupational groups with the same job titles. Moreover, the client in care consultation, a young adult, had a therapeutic relationship in adolescent psychiatry before moving into adult psychiatry services. This link between these two data sets was the reason we use these two different sets of data in this study. We also wanted to deepen our understanding of how psychosocial social work is structured in a real psychiatric assessment situation (with a client).

The client in care consultant meetings was a young adult who had several mental symptoms, such as anxiety and delusions. The client had previous contact with an adolescent psychiatric clinic and was currently in the process of transitioning to adult psychiatric outpatient care. All the professionals involved in the activities had a long working history in the field of psychiatry. The data were anonymized for this study, ensuring that they included no personally identifiable information.

Methodologically, this study is based on social constructionism. The methodological background of social constructionism lies in producing a shared social reality through language by affording social meaning to things (Flick Citation2022; Gergen Citation2009). In this qualitative research, the focus is on perspectives, experiences and meanings related to human beings.

The principal investigator has a background in practising social work in psychiatry and conducting research in the fields of hospice care and interdisciplinary collaboration. The other three investigators have a background in studying interdisciplinary collaboration, interprofessional interaction and interprofessional education from the viewpoint of social work practice and education.

Data collection

The focus group interviews of professionals (social workers, nurses and doctors) were conducted in the outpatient care services of adolescent psychiatry. The interview data included three 60-minute focus group interviews per occupational group. The purpose of the focus group interviews was to find out how different professionals describe psychosocial social work and how psychosocial social work is constructed in adolescent psychiatric outpatient care as a part of the interdisciplinary collaboration.

Six doctors (psychiatrists), four nurses and four social workers participated in the focus group interviews. The interviews were organized in 2018 for outpatient care workers per occupational group in adolescent psychiatry. In the interviews, professional groups were asked to describe the role and tasks of psychosocial social work and its implementation in outpatient care. At the same time, the professionals identified tasks that are not part of psychosocial social work. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. Focus group interviews are often organized for groups with similar experiences (Liamputtong Citation2011). Focus group interviews (see Neergaard and Leitch Citation2015) were chosen as one of the data collection methods because they enabled us to focus our analysis on the experiences of different occupational groups in social work. The professionals participating in the focus group interviews in 2018 did not participate in the video material recording in adult psychiatry in 2016.

The video material was recorded in 2016 during three interprofessional client meetings in adult psychiatric outpatient care. The client, a doctor (psychiatrist), a social worker, and a nurse (psychotherapist), which formed the IDT, participated in the first two meetings. In this study, we focused on the first and second sessions between the client and the IDT and the two reflective discussions after the client’s appointments, as the social worker was present in these. The IDT’s reflection discussions were held immediately after the client meetings. All the care consultation meetings were participated by the same client, social worker, doctor and nurse. The same IDT also participated in the examined reflective discussions without the client.

The data from the care consultations consists of two 45-minute live video recordings of discussions on the assessment of clients’ treatment needs and two 60-minute live video recordings of reflective feedback discussions after the care needs assessments carried out by an IDT in adult psychiatry. The video recordings had already been transcribed into textual data for this study. The video recordings were collected and transcribed in a research project led by one of the authors of this article. The video recordings added value to our analysis as they enabled us to advance and deepen our description of psychosocial social work with a real-life care need assessment situation.

Data analysis

We used data-driven content analysis as the method of analysing the data. The data-driven content analysis enables encoding and forming categories describing the examined phenomenon (e.g. Stemler Citation2001). In this study, we first analysed the focus group interviews carried out in adolescent psychiatry to form a view of how psychosocial social work is structured and then advance our analysis and understanding with data from adult psychiatry. Subsequently, we underlined any expressions of psychosocial social work described by the different occupational groups in the focus group interview material and paid attention to what kinds of similarities and differences we could find. We then encoded the concepts of psychosocial social work that played a key role and were frequently found in the data ().

Table 1. Psychosocial social work description as a part of interdisciplinary collaboration.

Subsequently, we moved on to examining the video recordings concerning the dialogue between the client and the IDT and the reflection discussions by the IDT in adult psychiatry. In the video recordings, we drew attention to how the psychosocial social work position appears and is constructed in the assessment of the client’s needs for care and in the reflection discussions by the IDT. We encoded any quotes by the client and the IDT that described psychosocial social work practices, such as determining the state of the client’s finances ().

Table 2. Psychosocial social work practice and interdisciplinary collaboration in a client’s care needs assessment.

We compared the findings (codes) on the focus group interviews and video recordings with each other and formed entities out of any similar descriptions and interpretations found in both sets of data and arranged these into categories (see ). We found no relevant differences in psychosocial social work between the two outpatient clinics. Subsequently, we formed a deeper understanding of how psychosocial social work is constructed and how it appears in the concrete care needs assessment situation with the client. Based on the categories formed on both data sets, we finally formed the perspectives describing the psychosocial social work framework (see ). Social constructionism (see e.g. Flick Citation2022; Gergen Citation2009) served as a frame of reference for the research material and analysis, as our aim was to structure the psychosocial social work through the social interaction situations between the various occupational groups and the client. From this point of view, the psychosocial social world is seen as a subjective construction created by an interdisciplinary team and occupational groups through the use of language and interactions.

Methodological discussion

In the case of video recordings and reflection discussions, the extent of the material should be examined critically, as this study concerned the description of a single client process. However, as a rule, qualitative research does not aim to be universal, but rather to deepen understanding of a given topic (see e.g. Flick Citation2022). Also, the coordination of the two sets of research data created a particular challenge to the research design, as the data were slightly different. However, both data sets concerned psychiatric outpatient care and the same occupational groups with the same job title. Moreover, the client in care consultation, a young adult, had a therapeutic relationship in adolescent psychiatry before moving into adult psychiatry services. Thanks to these mutual factors, a decision was made to utilize the data from two different organizations and outpatient clinics.

Together, adult and adolescent psychiatry represent the two parts of psychiatric outpatient care in this study. Although research data were collected from both adolescent and adult psychiatry, we found no relevant differences in the psychosocial social work between the two different outpatient clinics. Combining these two data sets enabled us to describe and analyse the psychosocial framework of social work in greater depth because we had the possibility to also examine a real client assessment situation. Without the video material, the analysis would have only relied on the descriptions of the professional groups.

Ethical considerations

Before data collection, ethical permission for the research process, including the video recordings, was obtained from the Council of Research Ethics of the local university hospital district. The focus group interview data were collected and transcribed by the principal investigator in the local hospital district in 2018. This study complied with Finland’s national ethical principles of research (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity 2019), emphasizing the voluntary and anonymous nature of research and principles pertaining to confidentiality. All participants were informed of all phases of the study and gave their permission to the use of the research data. With respect to both ethical considerations and the sensitivity related to the research setting, special attention was paid to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality when informing the participants about the study. The data were anonymized for this study to ensure that they contained no personally identifiable information.

Results

According to this study, psychosocial social work in psychiatry outpatient care comprises four perspectives affecting the assessment in which the social worker plays an important role as a part of the interdisciplinary collaboration. The perspectives are: 1) Social Environment, 2) Mental Health, 3) Service System and 4) Care and Rehabilitation, see . The perspectives describe and structure a professional framework for psychosocial social work in psychiatry. In psychiatry, psychosocial social work involves forming an understanding of the client’s psychological and mental well-being and the impact these have on the client’s social performance as well as the core elements of social work in assessing the client’s social environment and need for comprehensive support and referring clients to relevant services. The Social Environment and Service System perspectives emphasize core social work tasks and role and social factors as a part of an interdisciplinary psychiatric assessment of the client’s need for psychiatric care. According to these perspectives, the social worker usually plays a strong role as part of the interdisciplinary collaboration and guides the care needs assessment discussion that other professionals participate in. Meanwhile, based on the Mental Health and Care and Rehabilitation perspectives, the interdisciplinary team collaborates more to build a shared understanding of the client’s functional capacity, while the doctor usually guides the assessment discussion. At the same time, these perspectives (Mental Health and Care and Rehabilitation) bring psychosocial social work closer to the structures, interdisciplinary collaboration and a care need assessment of psychiatric care, see .

Social environment perspective in psychosocial social work

In the focus group interview of social workers employed in adolescent psychiatry, assessing the client’s social environment as a part of the care process emerged as one of the most important perspectives of social workers in psychiatry. Social workers approach this process from the perspective of holistic and social factors. The social workers pointed out that investigating and assessing the client’s overall social situation can provide a comprehensive view of the client’s current life situation, social relationships, networks and family and growth environment when the expertise of the social worker is combined with the information provided by the client. Based on the analysis, the nurses and doctors felt that the social worker provided a broader, environmental perspective to the assessment of the client’s care and rehabilitation needs.

´The social worker assesses the client´s social circumstances more broadly and ensures that the services needed by the client form a functional whole’

´The social worker brings her extended perspective to the discussion and looks at the young person’s situation in relation to their family, network and society, which helps the rest of the team understand the client’s situation ´

The care needs assessment in adult psychiatry advanced our analysis of the social environment perspective of psychosocial social work. Based on the analysis, in the care needs assessment in adult psychiatry, the IDT constructed an overall picture of the client’s needs for support. The discussion on the care needs began by addressing the client’s wishes for care and then proceeded to talk about the client’s family relationships and networks. In the meetings, the client raised the issue that they felt annoyed when their parents, especially their mother, were constantly phoning the client to ask them about their well-being and whereabouts. The client appreciated the care provided by their parents but also aimed to distance themselves from their parents.

´It would be easier if everyone would just let it go. It is irritating that everyone worries about me and it makes me feel guilty. My mother calls me all the time and if I don’t answer her right away, she panics.´

´What kind of a change do you hope for?´

´I don’t know´

´Although it irritates you, your mother probably thinks differently and is very worried about you. It would be good if your parents could visit here too´

´That would probably be good´

´You said your mother was worried about you. What’s mom worried about?´

´About everything´

‘Your siblings also asked you why you stayed at home with them, and you knew how to tell them about your situation´

During the treatment needs assessment by the IDT, the social worker addressed the client’s family relationships, leisure time and friendships in the discussion as well as the client’s contacts with the authorities. By doing that, the social worker contributed to forming an overall picture of the client’s current social environment with the IDT. The way in which the social worker spoke about the client’s social relations with the client was very practice-oriented.

´I’m tired of keeping in touch with my friends and I can suddenly stop responding to messages I’m not interested in them. Sometimes I try to have interest in my friend´s situation, but I often have nothing to say to them’.

´It is understandable that you don’t have the strength to chat with your friends and relate to their situations´

´I have my own things in mind and it is difficult to focus on other things´

´It sounds like you don’t have room for other things because you have so much to deal with your own issues.´

‘You have a lot of things on your mind and now it’s worth moving forward with small steps. Do you have any other contacts?’

It seemed that while the client had friends and networks around them, they wanted to sort out their own issues first before focusing on these relationships. In the reflection discussion, the doctor highlighted a discrepancy between the client’s symptoms and actions. The client described their condition as poor, but they were nonetheless able to engage in activities and meet up with friends, even though they occasionally found this stressful. Discussing the client’s social relationships and leisure time activities with the client helped the IDT form an understanding of the variation in the client’s functional capacity and management of everyday life. The Social Environment created an important view for the IDT about the client’s social relationships and networks in a real care need assessment situation.

´Last time the client described their OCD symptoms and what kind of harm those symptoms cause and how they can spend hours staring in the mirror. Now, they described how they can meet people and visit places´

´It describes variation in their performance.´

´They have been given several different diagnoses.´

In the reflection discussions in adult psychiatry, the doctors pointed out that the social worker plays an important role in investigating which networks and contacts the client already has, for example, to avoid overlapping support networks and services provided in psychiatric care. The doctors emphasized the importance of timely psychiatric care in relation to the support provided by networks. In the focus group interviews, the doctors also pointed out that an assessment of the social environment by a social worker is important for finding out what kinds of support services the client has already had an understanding of what kind of support has and has not been useful, and how the client’s social network, such as family, supports the client’s rehabilitation.

Mental health perspective in psychosocial social work

The analysis of the focus group interviews shows that, in addition to social work, all the other occupational groups emphasized the need to understand what psychiatric care involves and the skills required to assess the client’s need for rehabilitation in relation to the severity of their condition. This understanding brings the psychosocial social work profession closer to the structures of psychiatric care, ensuring that it will not be isolated from psychiatric care as a whole.

‘I think that a social worker working in psychiatry must know what psychiatry is and must understand the severity of conditions, their overall prognoses and information related to care and treatment’.

‘While we also contribute to caring, we do it with a social work orientation, meaning that we can’t take over the tasks of a nurse and any medications are prescribed by a doctor’.

Although the social worker had a specific role, especially in bringing social factors into the discussion, she also actively participated in the conversation concerning the client’s mental well-being and condition in the client’s care needs assessment in adult psychiatry. The social worker was interested in the client’s mental symptoms and participated actively in the medical discussion, which requires an understanding of psychiatric care, which was also found in the adolescent psychiatry material. The medical discussion was clearly an area where the IDT worked together to build a shared understanding of the client’s functional capacity.

´ How many hours have you been sleeping lately?´

´Sometimes five hours´

´How do you describe your condition on a scale of zero to ten, where zero is very depressed and ten is very hyperactive?´

´I feel more hyperactive´

´What score would you give to your condition?´

´Maybe six´

In the assessment, the client pointed out that they were afraid of sleeping alone at their home and that occasionally experienced sensory or auditory hallucinations. The client also reported difficulty remembering everything they had done. In the data analysis, the social worker participated actively in the discussion concerning the client’s coping with everyday life, for example their living conditions and mental well-being. The social worker shifted the focus of the discussion from medical issues towards questions concerning everyday challenges.

´I think it is because I used to live with my parents and now I live alone´

´Is this the first time you’ve been living alone?’

´Yes´

´Well then it is understandable. Can you describe what sorts of things you find difficult living alone?

´I feel anguish and it is hard for me to fall asleep´

´Are you afraid?´

‘Yes´

´What kinds of things are you afraid of?´

I do not know. I have nightmares and feel somehow paranoid. Every time I hear some sound, I get scared.

´Are you afraid that there is someone in the room?´

´Yes’

´Have you seen someone in the room?´

While the IDT described its roles as part of the interdisciplinary collaboration in the reflection discussions, the team also defined the expectations of other professional groups from their perspectives. The way in which the collaboration was implemented as well as health care demands and previous experiences affected the professionals’ expectations of the other professionals’ roles. They pointed out that, for instance, an IDT determines in which situations a social worker or a doctor must assess the client’s needs for care:

‘When these things have been assessed, such as whether a social worker is needed, or vocational rehabilitation needs must be assessed, or the client’s financial matters are quite messy’

´The team will assess the need for social work, because I cannot participate in all treatment discussions. It depends on what it says in the referral´

In the reflection discussion, the doctor highlighted the need for an interdisciplinary discussion in assessing the client’s needs for care. The doctor noted that sometimes the assessment is left to the doctor and the social worker, and the nurse may not participate in the discussion, even though the nurse is seeing the client currently or will do so in the future. By contrast, the nurse rather perceived her role as one of an observer. While doctors are accustomed to playing a leading role in interprofessional health care teams and their medical orientation can dominate discussions (Dryden and Mytton Citation1999, Glaser and Suter Citation2016; Rydenfält, Borell, and Gudbjörg Citation2019), this was not the case in our study, quite the contrary. In a focus group interview carried out in adolescent psychiatry, the doctor pointed out that, in psychiatry, a social worker plays a dual role and it is significant that social work is linked to the client’s psychiatric assessment as a need for care. This was also evident in the data concerning care need assessment in adult psychiatry, where the social worker was also actively involved in the medical discussion.

‘In psychiatry, a social worker plays a dual role, must understand mental health problems, but the training of a social worker provides a means of understanding mental health in a broader context’

The analysis of focus group interviews shows that it is not always easy to draw a line between nursing care and social work in psychiatry. The doctors also pointed out that social workers should clarify and systematize the methods by which they assess the client’s functioning and needs for comprehensive support to integrate these processes more clearly into the assessment of the client’s need for comprehensive care (see e.g. Gagle et al. Citation2017; Reese and Raymer Citation2004) and the rehabilitation process. Meanwhile, the nurses pointed out that the job description of a social worker appears occasionally unclear, as social workers tend to take on too much responsibility in caring for the client.

Service system perspective in psychosocial social work

In the focus group interviews carried out in adolescent psychiatry, the professionals’ description of social work put emphasis on expertise in the area’s service system, coordination of networks and knowledge of social security. Based on the analysis, social workers are expected to have wide-ranging knowledge of the service network and the relationship between services and their potential for improving the client’s social functioning. The interviews with the doctors and nurses highlighted the need for social work, especially when clients need support with their subsistence, housing and studying. A social worker was also often considered to act as an advocate for the client, ensuring that the client receives the services and support they need.

´As social workers, our work involves assessing what kind of network the client needs, at what stage and what is possible, so the work involves a lot of negotiation in relation to the client, their network and the care team. A social worker often acts as an interpreter in both directions, meaning that the social worker has an overall view of the client´s situation, needs and service system, and provides information about this to others in the care team, and this needs to be taken into account when planning care and rehabilitation.´

‘An increasing number of our clients are over 17 years old and they need support related to studying, earning a living and housing issues and require the special skills of a social worker’.

‘The social worker should play the role of an advocate for the client and be on the client’s side and address needs in the care team as an advocate for the client and their family. This would ensure that the family and client are heard in a client-driven rather than organization-driven manner’.

Knowledge of the service system was also emphasized in the assessment discussions on the need for care in adult psychiatry and increased our understanding of how the evaluation of the service system manifests in the client’s situation. In the video recordings, the social worker approached the discussion on the client’s care needs from the point of view of the social service system and social security. Among other things, the client reported in the discussion that they had difficulties living alone. Information provided by the service system was important for the professionals to consider in connection with making plans related to the client’s care needs.

´It is possible to get support for living alone. There is a service that provides support at your home once a week´

´Okay´

´It could be one possibility´

´What kind of help would you need?´

´I don’t know, perhaps it would be good to get my finances in order´

The client reported that they had unpaid hospital bills. In addition, the client was not fully aware of their rights related to income support. The role of the social worker was emphasized in this context and was clearly another core perspective of psychosocial social work. The client was used to coping on their own and without benefits. During the discussion, the IDT respected the client’s autonomy and personal strengths.

‘Have you applied for income support?´

´No, because I don´t know how. I have always had a certain sum of money in my account, it took long to discover that I don´t have that kind of money anymore.´

‘It seems that you are used to living independently. It is definitely worth applying for support and you have been entitled to income support all this time”.

‘Have you been able to pay this month’s rent?´

´Yes´

´What about medicine. Have you been able to buy medicines?´

The social worker assumed a strong role in clarifying issues related to a basic livelihood for the client. The social worker booked a separate appointment for the client with the purpose of helping them handle financial matters. While the social worker offered to support the client in working out their financial matters, the social worker also encouraged the client to take care of their financial matters independently.

In the reflection discussions by the IDT, the social worker pointed out that her role in assessing the need for interdisciplinary care involves examining, managing and coordinating the practical aspects and service needs of the client’s life. Understanding the service and social security system was clearly a core area of the social worker. The nurse, for her part, was more focused on her role as a background person, believing that the therapeutic relationship between her and the client was based on confidentiality. Meanwhile, the doctor was trying to keep to his role as a physician.

Yes, I have at least tried to keep in mind my role as a physician. I check for medication and sick leave issues and then consider the diagnostics. After a patient first arrives here, I try and think about what these symptoms could indicate

According to our client situation analysis, the professionals’ focus was on their own professional roles. However, adhering to roles did not mean that the professionals would not engage in dialogue on issues outside their respective professional roles. As a result, professional roles are also not permanent in interactive situations, but, instead, adapt to a given situation and context. This was partly evident in a focus group interview, where professionals described the role of social work as dependent on the objectives and core tasks of the outpatient clinic, as well as on the conditions and opportunities created for interdisciplinary cooperation.

Care and rehabilitation perspective in psychosocial social work

In the focus group interviews, social workers pointed out that the care of a client cannot be successful without assessing and taking into account the social factors that underlie the person’s symptoms. The nurses also pointed out that social work should enable the client to receive care by addressing underlying social stress factors, such as challenges related to school attendance. At the same time, social work was also considered to enable promoting the rehabilitation of a client in adolescent psychiatry, such as going to school or working within the limits of the client’s functional capacity.

We recognize that those problems are diverse so that it’s not just depression but behind a depression diagnosis there can be all these different things and then you’re treating it based on symptoms even when there is still a whole mess of things there that still exists even if the symptom is treated. Those problems are not only psychiatric but often social

‘You could use a social worker to complement the overall care, such as in considering what other support client needs to make their daily life run smoothly, as we can’t solve everything here at the psychiatric outpatient clinic, and the support that you provide in everyday life is really important for the success of care’

All the professionals seemed to try and understand the client’s experiences and feelings in the care needs assessment in adult psychiatry. Consequently, they at the same time changed their position from an observer to the experienced self (see e.g. Rober Citation2005). The social work highlighted in the focus group interview was also apparent in the care need assessment discussion in adult psychiatry, in which the social worker sought to explore the client’s possibilities for studying and working. In the care need assessment discussion by IDT, the social worker’s approach to client care and rehabilitation was respectful of the client’s views and wishes. The client wished to train as a teacher. In the discussion, the social worker supported the client’s wishes while at the same time ensuring that the goals set were realistic and could be achieved by the client.

´Let’s consider issues related to the near future and even more distant ones concerning your dreams. You would like to become a special needs teacher, and we were thinking about how that could be achieved. The first thing you said was that you wanted to leave your current job and start an internship in a kindergarten.´

´Yes´

´What do you think about your current work ability?´

´I cannot work´

“What do you think about your work ability in the near future?´

´I don’t know.´

´What kinds of obstacles do you have to overcome for the job?´

I can not do anything. I would not get my things organized and I would not get anything done at work´

´What do you think would happen if you went to work tomorrow?´

´I would probably get furious and cry and throw burgers at customers ´

‘Has such a thing happened?´

In the assessment discussion, one of the doctor’s tasks involved assessing the client’s work ability and writing a sick leave certificate if required. The social worker engaged in a versatile dialogue with the client about their current job responsibilities and challenges related to work, such as the effects of shift work on their coping at work. The social worker felt that there was no reason for the client to start active vocational training at this stage, but rather that the client should gather some strength, attend therapy and apply for studies at a later time.

´If we go back to discuss the sick leave, I was wondering if you did not have to go to work until September, there are still a few months before that, it is probably too early to evaluate the need for a sick leave.´

´It would be good for them to gather some strength and to attend therapy.´

Yes´

´I could meet you again during July and we could reassess the need for sick leave because it seems that your condition is a little better than before.´

The role of the social worker and the doctor in the interprofessional discussion was emphasized in the parts of discussions that particularly concerned the client’s current ability to work and function. Together with the client, the social worker and the doctor formed joint knowledge about the client’s ability to work. The nurse also took part in the discussion, but her role was rather one of listening and compliance. In the reflection discussion analysis, the doctor initially disagreed with the social worker about the client’s work ability. The doctor was unwilling to write a certificate for sick leave for the client, even though the social worker insisted on this as she believed that the client was not yet able to work. Eventually, the assessment of work ability was postponed.

´You disagreed with me a little and thought it would be wise to continue the sick leave. I disagreed first.´

‘Yes, or I thought that it would be wiser to assess it later and if they are still unable to work then, it is a good idea to continue the sick leave´

The reflective discussions revealed that the opinions concerning the client’s situation may differ in the IDT, affecting both the collaboration and how the support provided for the client is defined.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study are broadly consistent with other studies on psychosocial social work in mental health services. According to previous studies, the assessment of a client’s overall situation in mental health services is one of the most important practices of psychosocial work in social work (Corcoran and Walsh Citation2016; Gagle et al. Citation2017; Muralidhar, V, and Varambal-Ly Citation2012). In this study, the social environment element is a part of the care need assessment in the context of psychiatry, requiring social workers to also have an understanding of the client’s psychological and mental well-being. Based on these research findings, a social worker brings social environment and service system perspectives to the care need assessment of the client’s need for care, which other professionals perceived as an important part of interdisciplinary collaboration and assessment of the client’s needs for psychiatric care.

Psychosocial social work is considered to be linked to the client’s challenges in the social environment, which the professionals aimed to address through the opportunities brought by social security and the service system. In this context, the social worker was considered to serve as an expert in the service system and as an advocate for the client. At the same time, the social worker is also expected to understand the impact of mental illnesses on the client’s social environment and functioning (see Allison et al. Citation2016) and to promote measures that support the client’s rehabilitation and care. According to previous studies, the relationship between mental health and social factors is determined by their dual nature: social problems increase the likelihood of mental health problems, while psychological problems reduce social inclusion and coping in day-to-day life (Bailey Citation2002; Barners, Carpenter, and Claire Citation2000; Hill et al. Citation2011; Pevalin and Goldberg Citation2003). This view was confirmed in our study on the importance of psychosocial social work in psychiatry, where social work plays a kind of dual role, bringing social environment and service system perspectives to the psychiatric discussion. Previous studies have shown that the social factors (in this study social environment and service system) that contribute to mental health difficulties can reveal underlying themes of powerlessness, injustice, abuse or ‘social defeat’ (Gilbert and Allen Citation1998; Tew Citation2011), which makes it important to pay attention to the client’s social factors as a part of psychiatric discussion and rehabilitation.

According to this study, when a client comes to an assessment of care needs for the first time, the focus appears to be on the professional roles of the doctor and social worker. In contrast to a few previous studies (e.g. Dugan Day Citation2012; Kekoni and Mönkkönen Citation2021; Wittenberg-Lyles Citation2005), the social worker played a fairly strong role in the discussion on the client’s care needs also concerning their mental well-being. As a result, the present study did not reveal strong power relations between professions as found in many international studies (Atwal and Caldwell Citation2005; Dugan Day Citation2012; Neergaard and Leitch Citation2015; Wittenberg-Lyles Citation2005). By contrast, certain unclear professional perspectives were observed in connection to a discussion concerning the client’s work ability and the necessity of sick leave. This is also evident in the reflective discussions in which the doctor pointed out that she, unlike the social worker, would not have granted sick leave to the client. Similarly, in the focus group interviews, the nurses argued that social workers tend to take on too much responsibility in caring for the client. We believe that situations like these and the dialogue between professionals and the client help to understand the roles of other professionals, promoting joint knowledge formation (see e.g. Haridimos Citation2009).

Various studies have emphasized the importance of identifying the roles of professionals in different fields as a whole from the perspective of interdisciplinary collaboration. However, a common understanding of the client’s situation is built when the views of professionals meet and are joined in an equal dialogue (see, e.g. Arajärvi et al. Citation2019; Edwards Citation2011; Frank Citation2012; Haridimos Citation2009; Heritage and Maynard Citation2006; Juhila et al. Citation2021). Also, according to previous studies, social workers are also deeply involved in providing care management and evidence-supported behavioural health interventions (Zerden et al. Citation2018). It is important to form a shared understanding of both the client’s situation and the roles of the interdisciplinary collaboration to enable psychosocial social work in outpatient work as defined, responding to the client’s needs and utilizing interdisciplinary competence.

In this study, social work was shown to play a rather strong role as part of interdisciplinary collaboration and assessment of a client’s care needs. However, the analysis also showed challenges raised by the professional groups. Healthcare professionals in specialized psychiatric care typically use well-structured methods, including in determining a client’s diagnosis. In psychosocial social work, such methods are used less and this partly leads to an expectation for social work to also employ more structured and systematic approaches that take a clearer stance on the client’s psychosocial functioning from a social point of view (see e.g. Gagle et al. Citation2017). On the other hand, social work is not characterized by the use of instruments or carefully validated tools similar to those used in medicine, which is partly explained by the different knowledge bases of the two disciplines. We find that this study could be used as an example in the health and social services reforms which involve discussions on the positioning and role of social work as a part of interdisciplinary collaboration in social and health care services.

In social work education, it would be important to take mental health aspects into account as a part of the content of education programs. Mental health issues are not only present in the social work carried out in connection with health care but also in fields such as social work related to child welfare services. Interdisciplinary courses involving professionals such as doctors should also be included in the studies in social work in an effort to foster mutual understanding between the professions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, R., L. Dominelli, and M. Payne. 2009. Critical Practice in Social Work. E-book. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-36586-5.

- Allison, W.-L., J. L. M. McLoyd, M. H. Doyle, and S. J. Gehlert. 2016. “Leadership, Literacy, and Translational Expertise in Genomics: Challenges and Opportunities for Social Work.” Health and Social Work 41 (3): 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw022.

- Arajärvi, M., L. Leena, T. Kekoni, A.-E. Hovatta, N. Tusa, and K. Salokangas. 2019. “Moniammatillisen vuorovaikutuksen tarkastelua.” In Moniammatillinen yhteistyö. Vaikuttava vuorovaikutus sosiaali- ja terveysalalla, edited by K. T. Teoksessa, M. K, and A. Pehkonen, 47–88. Tallinna: Gaudeamus.

- Arajärvi, M., K. Mönkkönen, T. Kekoni, and T. Toikko. 2021. “Sosiaalityön psykososiaalisen asiantuntijuuden hyödyntämiseen vaikuttavat tekijät nuorisopsykiatrian avohoidossa.” Sosiaalilääketieteellinen Aikakauslehti 58 (1): 46–60. https://doi.org/10.23990/sa.86075.

- Ashcroft, R., C. McMillan, W. Ambrose-Miller, R. McKee, and J. B. Brown. 2018. “The Emerging Role of Social Work in Primary Health Care: A Survey of Social Workers in Ontario Family Health Teams.” Health & Social Work 43 (2): 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hly003.

- Atwal, A., and K. Caldwell. 2005. “Do All Health and Social Care Professionals Interact Equally: A Study of Interactions in Multidisciplinary Teams in the United Kingdom.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 19 (3): 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00338.x.

- Bailey, D. 2002. “Mental Health.” In Critical Practice in Social Work, edited by R. Adams, L. Dominelli, and M. Payne, 325–335. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Barners, D., J. Carpenter, and D. Claire. 2000. “Interprofessional Education for Community Mental Health: Attitudes to Community Care and Professional Stereotypes.” Social Work Education 19 (6): 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470020002308.

- Bower, M. 2005. “Psychoanalytic Theory for Social Work Practice.” In Psychoanalytic Theory for Social Work Practice. Thinking Under Fire, edited by M. Bower, 3–14. London and New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203341155_chapter_1.

- Bronstein, L. R. 2003. “A Model for Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” Social Work 48 (3): 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.3.297.

- Corcoran, J., and J. Walsh. 2016. Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis in Social Work Practice. Third ed. Oxford: University Press.

- Dryden, W., and J. Mytton. 1999. Four Approaches to Counselling and Psychotherapy. London. New York: Routledge.

- Dugan Day, M. 2012. “Interdisciplinary Hospice Team Processes and Multidimensional Pain: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Social Work in End-Of-Life & Palliative Care 8 (1): 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2011.650673.

- Edwards, A. 2011. “Building Common Knowledge at the Boundaries Between Professional Practices: Relational Agency and Relational Expertise in Systems of Distributed Expertise.” International Journal of Educational Research 50 (1): 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.007.

- Flick, U. 2022. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: SAGE.

- Frank, W. A. 2012. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. A. Holstein and J. F. Gubrium, 33–52. Sage Publication Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335117.n3.

- Frost, N. 2005. Professionalism, Partnership and Joined-Up Thinking: A Research Review of Front-Line Working with Children and Families. Dartington UK: Research in Practice.

- Gagle, J. G., P. Osteen, P. Sacco, and J. J. Frey. 2017. “Psychosocial Assessment by Hospice Social Workers: A Content Review of Instruments from a National Sample.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 53 (1): 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.016.

- Gergen, K. 2009. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gilbert, P., and S. Allen. 1998. “The Role of Defeat and Entrapment (Arrested Flight) in Depression.” National Library of Medicine 28 (3): 585–5 98. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798006710.

- Glaser, B., and E. Suter. 2016. “Interprofessional Collaboration and Integration as Experienced by Social Workers in Health Care.” Social Work in Health Care 5 (55): 395–408. doi:10.1080/00981389.2015.1116483.

- Granfelt, R. 1993. “Psykososiaalinen orientaatio sosiaalityössä.” In Monisärmäinen sosiaalityö, edited by R. G. H. Jokiranta, S. Karvinen, A.-L. Matthies, and A. Pohjola, 177–229. Jyväskylä: Gummerus kirjapaino Oy, s.

- Gunningham, J. M., and R. A. Booth. 2008. “Practice with Children and Their Families: A Specialty of Clinical Social Work.” Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal 25 (5): 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-008-0133-1.

- Haridimos, T. 2009. “A Dialogical Approach to the Creation of New Knowledge in Organizations.” Organization Science 20 (6): 941–957. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0435.

- Heritage, J., and D. Maynard. 2006. “Problems and Prospects in the Study of Physician-Patient Interaction: 30 Years of Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 32 (1): 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.082905.093959.

- Hill, J., C. Holcombe, L. Clark, M. R. Boothby, A. Hincks, J. Fisher, and P. Salmon. 2011. “Predictors of Onset of Depression and Anxiety in the Year After Diagnosis of Breast Cancer.” Psychological Medicine 41 (7): 1429–1436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001868.

- Horevitz, E., and P. Manoleas. 2013. “Professional Competencies and Training Needs of Professional Social Workers in Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care.” Social Work in Health Care 52 (8): 752–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.791362.

- Judith, T., K. C. Pollard, and D. Sellman. 2014. Interprofessional Working in Health and Social Care. Professional Perspectives. Second ed. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-39342-4.

- Juhila, K., T. Dall, C. Hall, and J. Koprowska. 2021. “Interprofessional Collaboration and Service User Participation.” In Analysing Meetings in Social Welfare, UK: Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447356639.001.0001.

- Kekoni, T., and K. Mönkkönen. 2021. “Constructing Shared Understanding in Interprofessional Client Sessions.” Nordic Social Work Research 4 (11): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2021.1947877.

- Korpela, R. 2014. Terveyssosiaalityön asiantuntijuus ja kehittäminen. Teoksessa Anna Metteri, Satu Ylinen & Heli Valo-kivi (toim.) Terveys ja sosiaalityö, 118–141. Juva: Bookwell.

- Leinonen, L. 2020. Sosiaalityön ja terapian rajapinnoilla: Sosiaalityön terapeuttinen orientaatio ja ammatillinen itseymmärrys psykiatrisessa erikoissairaanhoidossa. Available online at: https://erepo.uef.fi/handle/123456789/23321.

- Liamputtong, P. 2011. Focus Group Methodology and Principles. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957657.

- McGregor, J., S. W. Mercer, and F. M. Harris. 2018. “Health Benefits of Primary Care Social Work for Adults with Complex Health and Social Needs: A Systematic Review.” Health and Social Care 26 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12337.

- Muralidhar, A. S., D. V, and S. Varambal-Ly. 2012. “Clinical Social Work Perspective on Case Management in Mental Health. In-Depth Psychosocial Analysis and Intervention in a Single Case.” Rajagiri Journal of Social Development 4 (1): 71–80.

- Neergaard, H., and C. Leitch. 2015. Handbook of Qualitative Research Techniques and Analysis on Entrepreneurship. UK: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849809870.

- Pevalin, D. J., and D. P. Goldberg. 2003. “Social Precursors to Onset and Recovery from Episodes of Common Mental illness”.” Psychological Medicine 33 (2): 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006864.

- Reese, D. J., and M. Raymer. 2004. “Relationships Between Social Work Involvement and Hospice Outcomes: Results of the National Hospice Social Work Survey”.” Social Work 49 (3): 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/49.3.415.

- Rober, P. 2005. “The Therapist’s Self in Dialogical Family Therapy: Some Ideas About Not-Knowing and Therapist’s Inner Conversation.” Family Proscess 44 (4): 477–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00073.x.

- Rydenfält, C., J. Borell, and E. Gudbjörg. 2019. “What Do Doctors Mean When They Talk About Teamwork? Possible Implications for Interprofessional Care.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 33 (6): 714–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538943.

- Segal, S. 2014. “Social Work Health and Mental Health: Practice, Research and Programs.” https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315808956.

- Stemler, S. 2001. “Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation: An Overview of Content Analysis.” Yale University 7 (17): 1–6.

- Sverker, A., G. Östlund, M. Börjeson, M. Hägerström, and C. Gåfvels. 2017. “The Importance of Social Work in Healthcare for Individuals with Rheumatoid Arthritis.” Quality in Primary Care 25 (3): 138–147.

- Tew, J. 2011. Social Approaches to Mental Distress. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-92463-9.

- Venkat, P., and P. F. Abraham 2014. “A Strength Approach to Mental Health.” In A. Francis, eds. Social Work in Mental Health: Contexts and Theories for Practice, 126–143. India, USA, Great Britain and Singapore: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9789351507864.n8.

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E. 2005. “Information Sharing in Interdisciplinary Team Meetings: An Evaluation of Hospice Goals.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (10): 1377–1391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305282857.

- Wodarski John, S., and D. Feit Marvin. 2009. Evidenced Based Interventions in Social Work: Practitioner’s Manual. USA: Charles C Thomas.

- Woods, M. E., and H. Robinson. 1996. Psychosocial Theory and Social Work Treatment. in Social Work Treatment: Interlocking Theoretical Approaches. 4th, Edited by Francis J. Turner, 555–580. New York: Free Press

- Zerden, L. D. S., B. M. Lombardi, M. W. Fraser, A. Jones, and Y. G. Rico. 2018. “Social Work: Integral to Interprofessional Education and Integrated Practice.” Journal if Interprofessional Education & Practice 10 (2018): 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2017.12.011.