ABSTRACT

The building of sustainable innovation capabilities in Africa requires an innovation system capable of producing, disseminating and using new knowledge. This paper assesses the process of constructing the National Innovation System (NIS) in Rwanda. It is posited that consensus on and acceptance of the concept of NIS among stakeholders is crucial in the early process of constructing an efficient and dynamic innovation system. Primary empirical data are presented for the case of Rwanda and analyzed in a regional context. The study shows that the NIS concept is generally being integrated and utilized in the process of building sustainable innovation capabilities in Rwanda. In particular, Rwanda exhibits promising progress in the process of establishing and reinforcing infrastructures and institutions as well as policies to promote innovation. However, there are still challenges associated with low research capacity, low level of interactions among stakeholders, limited financial resources as well as lack of coordination framework, all of which contribute to hampering the building up of sustainable innovation capabilities.

1. Introduction

When the notion of National Innovation Systems (NIS) was offered some 30 years ago, it provided what would become a powerful conceptual tool for analyzing the complex interactive relationships between actors, institutions and companies that determine a country’s innovative performance. Pioneering works by Christopher Freeman (Citation1995), Richard Nelson (Citation1993) and Bengt-Åke Lundvall (Citation1992) laid the foundation for dissecting the knowledge generation system and for exposing the inner workings of how new technology and information effectively flows within that system.

Since then, the NIS under scrutiny can mostly be found in the advanced economies of the North and, to a lesser extent, in newly industrializing countries. Less empirical attention has been paid to countries with more rudimentary or even embryonic national innovation systems and the construction phase of national innovation systems. Can well-functioning innovation systems in such countries be built on demand as specified in national policies or are they a result of organic trajectories and path dependencies in the sense that they follow the economic progress of an economy and not the other way around? Can developing countries with fragmented innovation systems leapfrog the stages of classical development theory and design effective innovation systems in support of national goals? And, if so, what are the basic requirements in terms of institutions, actors and policy?

Classical development theory tends to regard the institutional set-up and functioning of advanced economies not only as a goal for late coming economies but also as a blueprint to be followed. In the early construction phase of NIS, it might be more prudent, as pointed out by Lundvall (Citation2012), to not focus so much on what is missing but rather on what actually exists. Such a pragmatic approach demands empirical data not only on institutional set-ups and on inventory of policy measures but also on interactive learning capabilities as well as perceptions on NIS by the principal actors. It is our contention that a general consensus on and acceptance of the concept of NIS among Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) stakeholders is essential in the early process of constructing an efficient and dynamic national system of innovation, in that it establishes a common conceptual foundation and provides different stakeholders with a means to better align institutional responsibilities to overall developmental goals as well as to counteract policy inconsistencies.

This paper analyzes the ongoing process of constructing a National Innovation System in Rwanda in a regional context. More specifically, the paper examines how the concept of NIS has been received by the STI community and how well it has been integrated into the capacity building process for sustainable innovation. Moreover, it identifies the prevailing perceptions of the STI stakeholders in Rwanda on what are the major challenges and obstacles in making science, technology and innovation an effective force for socio-economic development. In doing so, the paper contributes to the growing field of research exploring and contextualizing the NIS concept in a developing countries’ setting.

In the following section, the underlying theoretical framework is discussed, with an emphasis on learning as an interactive process in the developing world. The research design is presented in Section 3, followed in Section 4 by an analysis of efforts made in the construction of NIS in an East African regional context. Section 5 examines the case of Rwanda and presents the results of a survey of STI personnel in that country. The insights and prospects for the Rwandan NIS construction process are discussed in the concluding section.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Complex and interactive frameworks: connecting innovation and development

The surprisingly long-lived linear model of innovation was historically seen as driven by science pushes or market pulls. In the science push model, in vogue in the 1950s and 1960s, basic research was at the core of shaping technological innovations to be sent out to the market (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000; Manley Citation2002; Godin Citation2017). However, turning scientific knowledge into economic growth requires evolutionary processes and interactive approaches allowing for multiple dimensions; in addition to economic aspects, social and environmental dimensions are among the critical ones. Such integrated approaches call for systemic mechanisms and operations (Lundvall Citation2010; Vertova Citation2014). The innovation system approach is one of the frameworks that can be responsive in this regard. However, it requires building both capacity and capabilities where human and institutional resources are considered crucial starting points. In addition, both industrial and absorptive capabilities are seen as main factors for an innovation system to prosper (Etzkowitz and Dzisah Citation2008; Chaminade, Lundvall, and Haneef Citation2018). The building of such capacities and capabilities requires a proper understanding of the frameworks as well as appropriate facilitation from varying perspectives.

A number of frameworks aiming at the facilitation of the use of knowledge have been established and tested in different contexts. Several frameworks consider learning and interactions as main processes and where institutions and knowledge are major components (Fagerberg, Bengt-Åke, and Srholec Citation2018; Leydesdorff et al. Citation2019). Key frameworks and concepts include networks, value chains, clusters, development blocks, complexes, innovation milieu, complex products and systems, competence blocs and innovation systems. These were developed for the sake of understanding the complexity of interactive learning processes occurring in the innovation process (Manley Citation2002). For the construction and success of any of these frameworks, it is important to take into account the emergence process, the inputs and available resources as well as the operational environment. The latter can be related to the social structures, institutional framework, economic structures, capacity and capabilities building structures (Alkemade, Kleinschmidt, and Hekkert Citation2007; Djeflat Citation2015). The interactions among the structures and facilitation processes are important for resources and human capital circulation in order to promote the use of knowledge for development (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000).

In most developing countries, particularly African countries, institutional structures were inherited or replicated from their colonial rulers. An example of this replication can be some university structures and curricula in British and Belgian colonies (Havas Citation2002; Etzkowitz and Dzisah Citation2008). This replication might affect the construction process of a contextualized system with structures that are responsive to local context issues and enabling the flow of resources among the actors. Endogenous capabilities are hard to build with research and education systems that do not fit into the specific context, and yet the education system is among the drivers of innovation propensity in any innovation system (Freeman Citation1995; Sawyerr Citation2004). The African emerging innovation systems, thus, are interested in building endogenous capabilities to establish stable and performing innovation systems (Scerri Citation2016). The construction of individual countries’ innovation system in the context of emerging economies is likely to be linked to regional issues such as geographical location, higher education system, R&D performance and level of technological development (Jacobsson and Bergek Citation2006; Coenen Citation2006).

Depending on regional and local contexts, an innovation system can take different forms from the suggested initial concept referred to above. However, the adaptation and contextualization of the IS in a certain context require a proper understanding of the concept and exploitation of supporting instruments in terms of policy and institutional frameworks. The geopolitical patterns are key in the shaping of NIS in this case and it might be wise to position a NIS in its regional context for better understanding its construction process, as it is likely to be influenced by regional plans and transboundary operations (Leydesdorff et al. Citation2019; Fagerberg, Bengt-Åke, and Srholec Citation2018; Coenen 2006)

2.2. National innovation system: an emerging model in developing countries

The concept of National Innovation Systems can be considered as a tool for analyzing industrial development and economic growth, but also as an approach to understanding the diversity and complexity of the contribution of knowledge and learning into economic growth (Lundvall Citation1992; Högselius Citation2005). The variations in the forms and nature that NIS can take depending on specific contexts are still a contentious issue. Lundvall (Citation2007) made further steps in explaining the context-dependency of NIS by clarifying that the NIS concept, as designed for developed countries, cannot easily be replicated in developing countries because of differences in the level of knowledge production and economic structures.

With the context-dependency of NIS, Lundvall (Citation2007) has further highlighted the need for understanding the NIS concept for developing countries and for focusing more on system construction and promotion in light of the realities and special contexts present in developing countries. He argues that it is rare to find firms organized and engaged in innovation processes at the earlier stage in developing countries, and interactions between firms and knowledge infrastructure are still limited. This reflects the need to understand local contexts for industrial development and R&D performance to produce, transfer, access and exploit knowledge for socio-economic development in different contexts, particularly developing countries.

The emergence of NIS in developing countries should not only consider internal capabilities but also the regional context that influences the institutional and policy performances (Scerri Citation2016). In the same vein of context specificity in developing countries, some observers have suggested the crafting of new concepts instead of adopting a NIS framework that is built on the idea of high organizational capacity and competence; conditions which are not yet in place (Lall and Pietrobelli Citation2003). However, the introduction of alternative concepts for developing countries would not make sense as argued by Lundvall (Citation2007); it may be better to use alternative approaches in studying NIS in developing countries that fully consider the specific local contexts.

Freeman (Citation1995), referring to Friedrich List’s analysis of Germany in the 1800s, proposes that the understanding of higher education and research systems and their readiness to contribute to industrial development is a fruitful way to analyze developing countries’ NIS. This can be a good starting point as organizational structures in developing countries are still not sufficiently mature to allow a smooth flow of knowledge and interactive learning processes between firms and universities. This limitation is due to the fact that most of the firms and knowledge institutions are at their embryonic stage, and knowledge production is still focused on basic research rather than applied/industrial research resulting in technical innovations to be used by industries (Etzkowitz and Dzisah Citation2008). In the context of the East African region, efforts toward building regional systems/frameworks have been initiated and are likely to contribute to shaping local interactions among knowledge producers and knowledge users. This highlights the need for considering the regional context in exploiting individual country’s innovation system construction.

3. Research design

3.1. Regional comparison

This study focuses on Rwandan efforts to build a national innovation system. Further, it employs a regional and comparative perspective by contrasting the development in Rwanda with two other countries from the East African Community,Footnote1 Kenya and Tanzania. The selection of these two countries is based on the cluster classification elaborated by the African Capacity Building Foundation where countries are classified based on their capacities in science, technology and innovation (ACBF Citation2017). All countries in the Community, except South Sudan for which no classification is provided, are classified as either high or medium in scales ranging from low to very high. The three countries are classified as having either medium (Kenya and Tanzania) or high (Rwanda) STI capacity. Thus, even though the East-African region consists of countries with quite different socio-economic realities, the three countries reflect fairly well the general level of STI capacity in the region.

Country profiles for the three countries on STI capacity and performance were constructed through a structured review of key policy documents and performance reports. The main data sources used include the African Innovation Outlook of 2014, the UNESCO Science report of 2016, the African Capacity Building Foundation report of 2017, as well as countries’ reports from national offices in charge of STI. The collected data were used to build and compare macro-level country profiles for Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania.

3.2. Rwanda case study

The regional macro-level comparison provides a backdrop for the in-depth case study of Rwanda. Empirical data were collected through a survey of STI personnel in Rwanda where the opinions of representatives of different stakeholders were solicited in semi-structured interviews. Categories of institutions included government institutions (ministries, public research agencies and policymaking agencies), academic and research institutions, private sector and research funding bodies. The criteria for selecting the institutions were that they have a mandate either to perform research or to regulate research in some form. The criteria for selecting the representatives of the institutions to interview were that they either were senior researchers and/or responsible for research management at the institutions and/or involved in setting institutional or national policies for STI.

The interviews were conducted using an interview guide with semi-structured questions. A draft of the interview guide was first tested in a pilot study and subsequently revised (Annex I). The interviews were conducted during the period of December 2017 to February 2018. 24 persons () were interviewed, and each interview lasted for 30 min to 1 h. The interview guide had an introductory section with the purpose of the study and request for consent. Prior to each interview, interviewees granted their consent and interviews were conducted in the form of a conversation guided by 15 questions. These questions were focusing on stakeholders’ understanding of innovation, perception on collaboration among stakeholders, funding, capacity building and policy and legal framework in support to innovation. Interview notes were taken during the discussion for further transcription, organization and analysis.

Table 1. Data acquisition and analysis.

For analyzing the text, a checklist of parameters was established and keywords from the text were matched to parameters in the checklist. The parameters on the checklist included innovation categories (based on Oslo Manual, OECD Citation2018), NIS functions (based on Lundvall Citation2010 and Edquist and Hommen Citation2008) and key socio-economic sectors for innovation. In addition to these parameters, themes that reflect the perceptions on the construction process on NIS were extracted from the text and synthesized into a comprehensive text.

4. STI and NIS integration progress: regional efforts

The importance of STI for development in developing countries got its attention late compared to developed countries. Already in the 1960s, the first African countries mentioned STI consideration in their plans and programmes, but it was not among the priorities. At that time, the dominant paradigm of the modernization theory held that the capacities of the main knowledge producing institutions (universities and research institutes) in Africa were either insufficiently developed or too disconnected from society to be able to act as plausible sources of new technology (Arocena, Göransson, and Sutz Citation2014). It is not until the new millennium that the importance of STI has more concretely been addressed from an African perspective. The Lagos Plan of Action of 1980 served as a point of departure for the Lagos Consolidated Plan of Action of the early 2000s, which emphasized the promotion of STI as a driver for the envisaged socio-economic transformation for African countries. Efforts started to be invested in promoting the higher education system and building research capacity. Commitments were made in this attempt to promote STI, chief among them, to increase the R&D investment for African countries to 1% of GDP (Mugabe and Ambali Citation2005).

In addition to the increase of R&D investment, institutional development was prioritized as a means for better coordinating STI activities and to ensure collaboration among countries and individual institutions in Africa and globally through the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD Citation2014). Regional Economic Communities (East Africa, West Africa, Southern Africa, North Africa and Central Africa) initiated other efforts. Particularly in the East African Region, the East African Science and Technology Commission (EASTECO) and the Inter-University Council for East African (IUCEA) were key regional organs that were put in place to coordinate and harmonize standards and facilitation for higher education and research as well as innovation in the region (African Union Commission Citation2014; UNESCO Citation2015). Different funding schemes to operationalize these organs were established as a means to support research and innovation in the East African region. Bio-Innovate-Africa programme is among the key initiatives, as well as the funding for African Centers of Excellence (ACE) by the World Bank through IUCEA and individual countries’ governments in East and Southern Africa (IUCEA Citation2015; ICIPE Citation2017).

To ensure the alignment of STI with other development efforts, comprehensive agendas were put in place in conjunction with monitoring tools. Those include the STISAA and the STI indicators development initiative for Africa (Kahn Citation2008; African Union Commission Citation2014; New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD) Citation2014). In addition to this, operational frameworks to facilitate the integration of research in business communities were put in place. This can be observed through established partnerships between the IUCEA and the East African Business Council to foster joint research and innovation initiatives and inform potential areas for curricula improvement. The EAC Common Market Protocol of 2010 is also among the regional policy instruments that were put in place to ensure that market-led research aiming at technological development and technology adaptation in the society is conducted (UNESCO Citation2016). All these efforts, to some extent, contribute to individual countries’ IS constructions as they shape the context of the system evolution.

Even though commitments on paper were strong, the progress made has been meagre when compared to the expectations expressed in visions and goals of the documents. Most African countries have developed their visions to align their development with the Millennium Development Goals, agenda 2063 as well as the current Sustainable Development Goals. However, the progress in using STI to deliver on those visions has not been satisfactory in many countries. There is still a great need for enhancing STI systems in different Regional Economic Communities of Africa. The East African region is seen as the best performing Regional Economic Community to the Agenda 2063 aspirations. This raises the societal expectations and puts high pressure on the building of efficient STI systems in East Africa (AUDA-NEPAD Citation2020), although there is a lack of skills, financial means and infrastructures, among other challenges. The progress in honouring commitments from individual countries has also been challenging; for instance, the R&D investment average at the continental level still looms at 0.5% of GDP with some countries at almost 0% of GDP (ACBF Citation2017).

The STI institutionalization has also been lagging behind other parts of the world; some African countries do not have sufficient organizations for the management of STI or policies to guide the promotion of STI. The NIS is expected to build on existing organization, interactive learning and innovation capabilities contributing to industrial development. Considering the slow progress, it is hard to realize how interactions can be facilitated and how the NIS concept can be embraced. However, some countries have indeed made progress in promoting STI and setting the scene for accepting the NIS concept for ensuring the contribution of knowledge to the development of society. The East African region is among the parts of the African continent that have made some progress. The following section presents the system setting and STI integration performance of Rwanda in comparison to two of its neighbouring countries.

4.1. Progress in promoting STI in Rwanda, Tanzania and Kenya

Investment in STI is among the key strategic actions for making STI a tool for development and to ensure that the needed knowledge for societal development is being generated. The GDP composition of a nation may give a general picture of how R&D is making a difference in national economic development. Countries shifting from a natural resources-based development to a knowledge-based development show a higher rate of technological development, reflected in the progress made by its industrial sector (Freeman Citation1995). This does not seem to be the case for the East African Region, even though efforts are being made. The countries selected for this study have small differences in their GDP composition, with the service sector dominating in all countries followed by the agriculture sector. The industry sector is still lagging behind in Rwanda compared to the other countries, even though it is still relatively low also in the other countries compared to the current technological and products’ demand in the region (UNESCO Citation2016). The R&D expenditure as a measure in effort in knowledge and technology production is still low compared to the commitment of 1% share of the GDP, especially for Rwanda and Tanzania, which are still below the continental average of 0.5% (ACBF Citation2017). shows the countries’ R&D expenditure per capita, per researchers and by sector of performance.

Table 2. R&D Expenditure (PPP$ and %).

In relative terms, Rwanda spends less than half and less than a quarter of what Tanzania and Kenya respectively spend on R&D as a share of GDP. If we look at R&D expenditure by sector of performance, we can notice considerable differences between the countries, reflecting disparities in policies for knowledge generation. In Rwanda, almost a third of all R&D is carried out in the non-profit sector (). The corresponding figure for Kenya is 12% and virtually non-existent for Tanzania. In all three countries, Higher Education is a prominent performer of R&D, accounting for as much as 86% in Tanzania and close to 50% in Rwanda. In these two countries, the main R&D performer in industrialized countries, the business sector, is not an actor at all, whereas Kenya has seen the contribution of the business sector climb to 8.66% of total R&D expenditure in 2013. The situation with low levels of resources devoted to R&D and the absence of major actors in the NIS is further exacerbated by the fact that much of the funding is appropriated from abroad in the form of Official Development Aid (ODA) and other international sources. Foreign funding contributes about 69, 47 and 42% for Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania respectively (UNESCO Citation2016). This shows the need for all the countries to develop strategies to build internal funding mechanisms, shy away from the high reliance on foreign funding and instead develop collaborative mechanisms with external research communities built on mutual contributions.

4.2. Institutional and organization development in Rwanda, Tanzania and Kenya

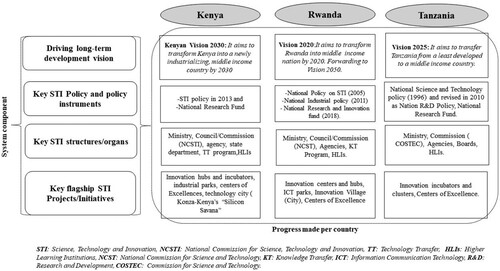

Among the key components of innovation systems are institutions, both formal and informal, as well as aligned working environment characterized by policies and legal frameworks (Edquist and Hommen Citation2008). For emerging national innovation systems, the setting up of organizations and institutions for facilitating the production, acquisition, diffusion, transfer and use of economically valuable knowledge are among the key steps. Knowledge infrastructures development is important as well as human capital development. To understand the process of NIS construction in developing context like the East African region context, it is relevant to look at how countries have developed their long-term development visions and how they are setting up systems to make STI as a matter for achieving those envisioned long-term development goals. This can be examined by looking at the progress in developing institutions and policy instruments as well as emerging initiatives as a way of starting the system move. shows the progress made by each of the selected countries in the above-mentioned issues.

Figure 1. Progress in national STI and R&D organizational development. Source: Authors’ own compilation based on United Republic of Tanzania Citation1999; Republic of Kenya Citation2007; World Bank Citation2008; Republic of Rwanda Citation2012; UNESCO Citation2016.

As seen in , Rwanda has a highly ambitious vision 2020. That country also exhibits a consistently high and positive trend in GDP growth in recent years (UNESCO Citation2015; IMF Citation2019) despite exhibiting the lowest investment level in R&D of the three countries. Partly, this can be explained by the fact that the current sustained economic growth is not so much relying on knowledge and technologies produced locally but rather on the importation of technology. However, the reliance on technology importation does not, in most cases, offer sustainable development solutions (Juma Citation2016). With the current R&D investment for Rwanda, it is hard to imagine the achievement of the envisioned knowledge-based economy and economic transformation, unless strategic measures in R&D funding can be developed or collaborative mechanisms that stimulate active learning can be fostered, raising internal research and technological competencies. The worrying situation is not only for Rwanda, the other countries in this study are also concerned as well, considering that they all base their R&D funding on foreign funds; as shown in , only Kenya has taken steps to involve the business sector in investing and performing R&D.

5. National innovation system in Rwanda: empirical evidence on the construction process

5.1. The emergence of the NIS concept in Rwanda and its integration progress

The survey of STI personnel in Rwanda reveals that the NIS concept in Rwanda is not uniformly understood by all stakeholders. The general low level of awareness of the concept among some stakeholders makes it harder for the actors in the innovation system to work in harmony. Without a clear understanding of the inner workings of the innovation system, the identification and alignment of inter and intra-institutional responsibilities become haphazard at best (Chaminade, Lundvall, and Haneef Citation2018; Fagerberg, Bengt-Åke, and Srholec Citation2018). Academic and research institutions in Rwanda appear to understand the concept fairly well whereas private and government institutions have a relatively low level of understanding of the concept. Considering the Rwandan ambition of fairly rapidly becoming a knowledge-based economy, efforts are being invested in establishing institutions and organizations to promote higher education and research, but the interactions among institutions that are emerging and the rest of the society are still challenging. Respondents recognized that a strong education system can help in building the Rwandan NIS as this can be the source of qualified graduates who can serve in the business sector as well as the society at large. In the interviews, the performance of problem-based research was highlighted as a key driver for constructing a NIS but the Rwandan research environment shows a low level of interaction among researchers and research end-users. This makes research that is being conducted unresponsive to demands of the society.

-Does the system exist? I know that there are strategic policies that drive plans and actions considering innovations for improvement. Innovation is reflected in most of the policy documents and innovative ways of doing things are encouraged. If the system is to be established then, it needs to be well understood and I think that it needs to take reference from where it succeeded (Senior policymaker).

-Our organization is not much familiar with the NIS, however, we recognize the need for research to find solutions that match with the national development pace, like in the agriculture sector we need solutions to increase the production that meets the demand (Private Sector Federation Representative).

Several respondents of the survey point to the very low level of collaboration between academic/research institutions and the private sector. The lack of interactions may also be linked to poor coordination and facilitation from public institutions that are mandated to do that. This may be resulting from the weak institutional framework and lack of clear policy frameworks, as highlighted by respondents. Institutions are there, but operate in silos.

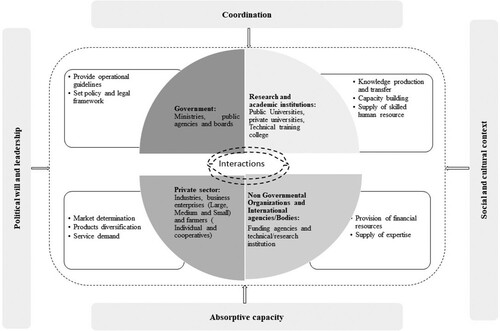

The current stage in the construction process from the narrow perspective shows low interactions in STI organization and R&D performance. The narrow perspective focuses on the organization of STI and R&D performance and it is at the centre of the NIS maturity and performance (Cassiolato et al. Citation2006). With the observed low interactions, the current status on the Rwandan NIS seems to be at the early stage although promising based on the commitment and trends in activities aiming at establishing an operational NIS. The broader perspective that consists of the overall operational environment seems to be more developed as there is a high political will expressed in policy documents and leadership commitments. The high interest from the society also expresses a promising social and cultural acceptance of innovations, which is a challenge in some places in the NIS construction process, particularly in developing countries. The coordination and absorptive capacity are among the major challenges from a broader perspective. shows the overall map of the Rwanda NIS in both narrow and broader perspectives based on interviews and policy document data.

5.2. Awareness of the concept of innovation and views on its economic impact in Rwanda

Contrary to the rather low understanding of the notion of the NIS, the respondents exhibited a high level of awareness of the concept of innovation; however, their views and definitions of innovation varied across stakeholders’ categories. Despite this variation in views, perceptions on the end results from innovations remain similar as all interviewed people acknowledged that innovations aim at addressing community needs. Actors from the education sector view innovation as the application of new knowledge or value addition to the existing knowledge for addressing the community needs and they recognize that the knowledge is to be generated from research and education. However, a few mentioned experience and exposure to be the source of needed knowledge for innovation. This reflects the status of incremental innovation dominating in developing countries which are mainly results of utilization of imported technologies with active learning as a technology adoption approach (González-Pernía, Parrilli, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015). The public/government and private sectors perceive innovation as any new thing that is done differently and have a positive impact. This view is not much different from the higher education perspective, although both these sectors view innovation as an end product in itself without considering the process and key stimulating factors.

-It is hard to define innovation as different organizations may have their own definition depending on their focus. This is driven by agendas in place and discussion. In Rwanda, it is hard because there is no public discussion on innovation and the understanding of innovation among stakeholders is still problematic (Funding agency).

-Innovation is the application of knowledge or research outputs to meet the market demand. They can be a technology or a new market. However, we need to differentiate innovation and invention even though both have commonalities (University researcher).

-Innovation in PSF is viewed as any solution to the relevant problem in the society that helps in creating new jobs, new market and transform the livelihood in the society (PSF Representative).

Table 3. Stakeholder interest in innovation categories.

5.3. Potential socio-economic sectors for innovation in Rwanda

Based on the demand from the Rwandan society, there is a wide range of possible innovations even though resources are limited. The current demand in the Rwandan society calls for innovation in different socio-economic sectors to achieve the expected socio-economic transformation. Respondents to the survey have varying views on the potential for innovation in different sectors in Rwanda where increased innovation capabilities can lead to considerable industrial development and development of society in general. The agriculture sector scores highest among potential and promising sectors. Other key sectors including ICT, industry (manufacturing), health, education, service and construction and urbanization are considered to have potential for innovation (). This does not exclude other sectors to have innovation potential but those are key sectors perceived to be promising, based on current demand, government priorities and possibilities for investment and resources mobilization. The list appears to be long, and for realizable impact, priorities need to be set.

Table 4. Perceptions on the potential for innovation in socio-economic sectors.

Priority setting is one of the best practices in building internal capabilities, especially in the case of scarce resources (Dosso, Kleibrink, and Matusiak Citation2018). The stakeholders’ views on potential socio-economic sectors might pave the way for priority setting in building innovation systems in key sectors which can ultimately contribute to the overall NIS performance. This might be also a tool for local and regional innovation systems development, which can enhance industrial development in specific regions and sectors depending on existing potential and their efficient exploitation. The understanding of innovation propensity in potential socio-economic sectors plays an important role in resources allocation and specialization in tools and mechanisms for interaction and learning process (Freeman Citation1995; Leydesdorff et al. Citation2019). The observed high potential in agriculture and ICT sectors, if well exploited, can influence other sectors as both are comprehensive sectors covering a wide range of actors and different localities across the country.

5.4. Systemic interactions: innovation pathways and stakeholders’ linkage

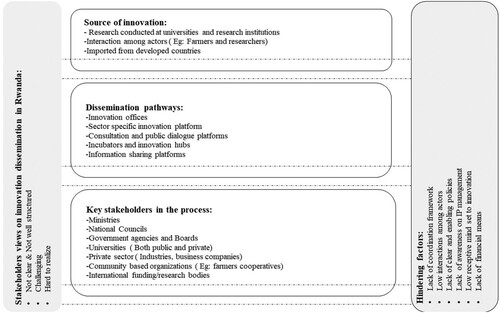

The process of innovation dissemination remains unclear to many stakeholders in Rwandan institutions and is perceived as challenging, even hard to realize. Dissemination in this context entails bringing the innovation to end-users, either in the form of a commercial undertaking or as a social innovation transferred directly to the users, e.g. improved agricultural farming techniques. Only a few representatives of institutions stated that substantial steps in dissemination have been taken. Major reasons for this low dissemination ability identified by the respondents include the lack of clear dissemination framework, lack of coordination at the national level and within institutions, lack of flexible systems that allow dynamism among stakeholders, lack of skills for better profiling innovations to be disseminated and lack of financial means as well as lack of a supportive and receptive mindset for innovation for end-users. In addition to these major reasons, poor information sharing and lack of knowledge commercialization strategies, as well as low skills in Intellectual Properties management are recognized by the interviewees as limiting factors for innovation dissemination.

-It remains unclear as to how innovation generation and dissemination are coordinated, as sources of innovation are not well mapped out and some potential innovators don’t even know that they have that potential. At the national level, there are gaps particularly due to the lack of frameworks to coordinate innovation processes. The conflict of interest among stakeholders is observed as one of the hindering factors for innovation development and dissemination (Senior Policy Maker).

-Innovation development and dissemination is still challenging in Rwanda, as many stakeholders consider technology/solution importation as innovation and most reliable compared to local solutions. The mindset in relying on imported solutions and lack of financial means are key hindering factors for innovation dissemination. However, the negative competition and rivality among innovators can’t be negligated as well (Senior STI Manager).

Although innovation dissemination is still very low in many institutions, it was recognized in institutions where dissemination actually is occurring (e.g. the Institute for Policy Analysis and Research (IPAR) and Rwanda Agriculture Board (RAB)) that public dialogue, innovation platforms, community innovation centres, workshops, seminars and conferences are major pathways for dissemination. However, it was generally highlighted by most stakeholders that it is important to set platforms for stakeholders’ interactions, varying from intra to inter- institutional collaborations. Among the ways to do that include establishment of innovation uptake offices, establishing stakeholders/professional networks, creation of incubators and setting proper communication channels as well enabling a business environment that stimulates commercialization of knowledge. Integrated multidisciplinary approaches for innovation dissemination are encouraged for research institutions whereas public dialogues and market linkage are considered by the respondents as the best approaches to link researchers, public sector and private sector respectively.

To increase dissemination capacity, the importance of collaboration among stakeholders was highlighted in aspects related to capacity building, financial resources mobilization and infrastructure sharing. Most of the respondents stated that their institutions were engaged in collaboration in different forms including both formalized and non-formal collaborations. Formalized collaborations include collaborations under contract agreements, loans, MoUs and joint projects. Stakeholder collaborations include universities, ministries, government agencies, research institutions, industries, business companies, community-based organizations, local NGOs, international NGOs, UN agencies and international funding bodies like USAID, DFID, Sida, AfDB and WB. shows the current status and future perspective of origin and dissemination of innovations, considering key players as well as challenges they are facing in the process.

Figure 3. Innovation emergence and dissemination pathways as well as associated challenges. Source: Survey by the authors, 2018.

A low level of collaboration among local institutions was observed compared to collaboration with international and regional institutions. Collaborations among public institutions are very low and most of the actors claim this to be the root cause of the low performance of the entire systems as this in many cases results in duplications of efforts. Collaboration between universities and local industries/private sector was judged to be almost non-existent and even in cases where collaborations have been initiated by government push, they did not materialize and did not result in any positive impact or sustained initiative contributing to innovation development.

The development and dissemination of new knowledge are key for the construction process of the innovation system. The source of innovation and pathways for dissemination as well as actors engagement is crucial in the construction process and requires preparedness as well as a welcoming environment (Alkemade, Kleinschmidt, and Hekkert Citation2007; Fagerberg, Fosaas, and Sapprasert Citation2012). As interview results showed, sources of innovation, as well as pathways, are unclear to actors. That coupled with the low receptive mindset of end users are among the key hindering factors. As suggested by Chaminade and Lundvall (Citation2019) and Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae (Citation2010), clear organizational structures and coherent mandates are major factors to build synergies in the knowledge production and dissemination process. This also needs to be accompanied by attributes and values such as trust and loyalty among actors. This can be facilitated by enhancing open debates on innovation and policy dialogues among actors.

5.5. Research and innovation policy and governance framework

Research and innovation policy and governance frameworks in Rwanda are perceived by stakeholders as relatively supportive to research and innovation development, albeit with limited enabling capacity as there are no recognizable incentive schemes for innovators and researchers. Policies for STI are perceived as well formulated as they are considered to be aligned with the government agenda and development plans. But this does not exclude the observed duplications and overlaps in policies which results in low implementation and waste of resources.

Even though there is a National Science, Technology and Innovation policy put in place in 2006, it is not yet accompanied by other policy instruments, which are still in the pipeline or in future plans as acknowledged by NCST. Development of research and innovation policies at intuitional levels is still very low as most academic and research institutions as well as public institutions do not have institutional research policies but rather have research strategies in place. Few of them have research units to manage research activities; only academic and research institutions have made any progress in establishing research units. As pointed out by the representative of the Private Sector Federation (PSF), the Rwandan private sector shows a low interest in research and this explains the lack of R&D units in almost all industries in Rwanda. However, the PSF is establishing a research unit on market research. This newly started unit has a very low number of researchers; it relies on outsourcing consultants but has a long-term vision of hiring permanent researchers in different disciplines of research that are pertinent to the Rwandan private sector.

Despite the effort devoted to new structures for research management, innovation management is still lagging behind in matters related to policy frameworks. There is no institution in Rwanda with a specific innovation policy and few have offices that focus on innovation matters only; those that do are academic and research institutions. Examples are the University of Rwanda and the National Industrial Research Development Agency. In most other institutions, research and innovation are managed under research units and research strategies cover innovation matters when it comes to policies.

Despite the existence of national policies and laws – such as the Intellectual Property Law – as well as institutions performing research and innovation, there is a number of management challenges that deserve attention. Among these are the lack of policy implementation mechanisms and tools, lack of skilled human capital for policy formulation and implementation, lack of awareness on the existence of some policies and laws, duplication and overlaps among policies, instability and lack of flexibility in policies and disconnect among policy-makers and implementers. The lack of awareness on policies and law coupled with a lack of implementation mechanisms were key challenges mentioned by all respondents. Research and academic institutions perceived policies to have overlaps and duplications as well as being unstable without allowing time for implementation and assessing their impact.

-There are some policies in place and law (STI policy, IP law, …) but they present some challenges related to duplication and overlaps in their scope. Their implementation is problematic and deserves attention from policymakers. National policies should be accompanied by institutional policies for effective implementation at different levels. Although, this is not observed in many research and academic institutions when it comes to innovation policy. A conducive environment for policy implementation needs to be in place as well with skilled human resources (University Researcher).

-In Rwanda, policies, regulations and laws are in place but people are not aware of them and their implementation is still low. Innovators should be sensitized about the existence of the IP law and how beneficial it can be to protect their IP as most of the people in the Rwandan context are not aware of the IP issues (Innovation Manager at University.)

6. Concluding remarks: insights and prospects for the Rwandan NIS construction process

It is a premise of this paper that the National Innovation System as a model of innovation needs a thorough scrutiny before its integration in a developing countries’ context (Lundvall Citation2007; Kraemer-Mbula and Wamae Citation2010). The adoption and integration of NIS need to take into account contextual realities that differ between countries and levels of economic activities. The ongoing debate on adoption and contextualization of NIS in developing countries has to consider dynamics in organizational structure, knowledge production capacity as well as end users absorptive capacity. The Rwandan case confirms a high need for enhanced interactive learning with a balanced use of modes of learning. The role of innovation policies and understanding of innovation process are other fundamental aspects for the contextualization of the NIS model. The integration of NIS appears to be progressive process with different stages that include different milestones. There is an ongoing debate on how to measure these stages in the integration process. However, it is important to ensure coherence between patterns of the narrow and broader perspectives of the NIS in the construction process.

For Rwanda, the construction process of the National Innovation System exhibits some characteristics of the ideal NIS prescribed in the literature. However, it is evident that there still is a lack of understanding of the concept itself among the stakeholders. The efforts towards NIS construction in Rwanda are oriented to the narrow NIS with a strong interest in increasing R&D investment, STI capacity building and infrastructure development. R&D-based knowledge is considered to be the most reliable source of innovation. However, it might be wise to consider other modes of knowledge acquisition and accumulation like ‘learning by doing’ and ‘ learning by using’ in the construction process as suggested by Lundvall (Citation1998) and González-Pernía, Parrilli, and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2015). This of course requires building capacity and capabilities; both dynamic and absorptive capabilities are imperative in this case. The enhancement of the higher education system and strong collaborations as well as proper organizational structures can be among the option to build such capabilities.

This leads to a further premise of this paper, which is that awareness among the stakeholders of the NIS concept and its economic impact is vital for understanding ways for building a system that promotes innovation as a tool for economic growth. This point to the broader NIS that needs to be consistent with the narrow NIS for a sustainable comprehensive NIS. Supportive political environment, socio-cultural support systems and a conducive business environment are major components to focus on in the broader NIS construction process, as observed in the Rwandan case. The level of understanding of the concept and its associated element has a considerable impact on the broad NIS construction. In addition to this, the effect of geographical proximities and regional integration needs to be considered for possible effects on economic growth. In the context of small countries like Rwanda, a selective approach in the system construction process can be an option in linking transnational innovation system and local innovation systems (Shafaeddin Citation2000). This should be associated with coherent policies and policy instruments that allow for collaboration and synergetic actions among stakeholders.

Based on the standard theoretical provisions, the NIS construction process in Rwanda shows promising progress. However, there is still a lack of focus on ensuring interactions among actors and synergies among institutions. It may take time to build an effective NIS in Rwanda, as in many other developing countries, but it is feasible if the concept is well understood by the government agencies that are mandated to promote STI. It is clear from the survey that government and higher education institutions are the almost exclusive performers of STI in Rwanda. However, constructing a dynamic NIS also requires the involvement of industry as the main user of knowledge and technologies produced from R&D as well as a potential investor in R&D. This is particularly relevant for the development of the agro-business sector, which holds a high potential for innovation activities and industrial development.

Rwanda has made a good progress in accepting the NIS concept compared to its neighbouring countries in the region. This is particularly so in matters related to STI in policies and national development plan as well as institutional development. However, Rwanda is still lagging behind in matters related to R&D funding compared to the two other countries in the region used in this study, Kenya and Tanzania. This indicates the need for Rwanda to set up mechanisms for research fund mobilization as well as for reconsidering national funding priorities of R&D in order to achieve the aspired knowledge-based economy that is reflected in the national development plans and programmes. Moreover, the country exhibits a lack of research capacity in both infrastructure and human resources. It remains a challenge to enhance interaction with industries and other end-users of innovations. Incubators are identified as the main instrument for maturing innovative ideas, but it is still a challenge to proceed from incubation to commercialization and utilization in society. This would appear to be connected to the lack of collaboration among actors; hence, the enhancement of collaborative frameworks is key in Rwanda’s NIS ongoing construction process, and by extension, in the building up of innovation capabilities and industrial development.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) through the University of Rwanda-Sweden Program – Research Management Support Sub-Program.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Encompasses Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

References

- ACBF. 2017. Africa Capacity Report 2017: Building Capacity in Science, Technology and Innovation for Africa’s Transformation. Harare, Zimbabwe: The African Capacity Building Foundation.

- African Union Commission. 2014. Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa 2024. Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Alkemade, Floortje, Chris Kleinschmidt, and Marko Hekkert. 2007. “Analysing Emerging Innovation Systems: A Functions Approach to Foresight.” International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy 3 (2): 139-168.

- Arocena, R., B. Göransson, and J. Sutz. 2014. “Universities and Higher Education in Development.” In International Development – Ideas, Experiences and Prospects, edited by Bruce Currie-Alder, Ravi Kanbur, David M. Malone, and Rohinton Medhora, 582–599. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- AUDA-NEPAD (African Union Development Agency-NEPAD). 2020. First Continental Report on the Implementation of Agenda 2063. Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Cassiolato, Eduardo, Helena Maria, Martins Lastres, Maria Lucia, and Maciel Eds. 2006. “Systems of Innovation and Development-Evidence from Brazil.” Review of New Horizons in the Economics of Innovation series, by Christopher Freeman. Technovation 26: 543.

- Chaminade, Cristina, and Bengt-åke Lundvall. 2019. Science, Technology, and Innovation Policy: Old Patterns and New Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chaminade, Cristina, Bengt-Åke Lundvall, and Shagufta Haneef. 2018. Advanced Introduction to National Innovation Systems. Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Clark, Norman. 2002. “Innovation Systems, Institutional Change And The New Knowledge Market : Implications For Third World Agricultural Development.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 11 (4–5): 353–368.

- Coenen, Lars. 2006. “Faraway, So Close! The Chaning Geographies of Regional Innovatio.” PhD diss., Lund University.

- Djeflat, Abdelkader. 2015. “Emerging Innovation Systems (EIS): A New Conceptual Framework For Analysing GCC And Maghreb Countries Policies.” International Journal of Innovation and Knowledge Management in Middle East and North Africa 4 (2): 75-85.

- Dosso, Mafini, Alexander Kleibrink, and Monika Matusiak. 2018. “Smart Specialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa : New Perspectives for Innovation-Led Territorial Development.” EAI’s international conference on Technology, R&D, Education & Economy for Africa.

- Edquist, Charles and Leif Hommen, eds. 2008. Small Country Innovation Systems: Globalization, Change and Policy in Asia and Europe. Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and James Dzisah. 2008. “Rethinking Development: Circulation in the Triple Helix.” Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 20 (6): 653–666.

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and Loet Leydesdorff. 2000. “The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a Triple Helix of University-Industry -Government Relations.” Research Policy 29: 109–123.

- Fagerberg, Jan, Lundvall Bengt-Åke, and Martin Srholec. 2018. “Global Value Chains, National Innovation Systems and Economic Development.” The European Journal of Development Research 30: 533–556.

- Fagerberg, Jan, Morten Fosaas, and Koson Sapprasert. 2012. “Innovation: Exploring the Knowledge Base.” Research Policy 41 (7): 1132–1153.

- Freeman, Chris. 1995. “The National System of Innovation in Historical Perspective.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 19 (1): 5–24.

- Godin, Benoît. 2017. Models of Innovation: The History of an Idea. London: The MIT Press.

- González-Pernía, José L., Mario Davide Parrilli, and Iñaki Peña-Legazkue. 2015. “STI–DUI Learning Modes, Firm–University Collaboration and Innovation.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 40 (3): 475–492.

- Havas, Attila. 2002. “Policy Matter in a Transition Country ? The Case of Hungary.” Journal of International Relations and Development 5 (4): 380–402.

- Högselius, Per. 2005. The Dynamics of Innovation in Eastern Europe: Lesson from Estonia. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- ICIPE (International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology). 2017. BioInnovate Africa Programme Implementation Manual (2016–2021). Nairobi, Kenya: International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2019. World Economic Outlook: Growth Slowdown, Precarious Recovery. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- IUCEA (Inter-University Council for East African). 2015. Summary Report of the Regional Workshop on Eastern and Southern Africa Higher Education Centers of Excellence (ACE II). Dar es Salaam: United Republic of Tanzania.

- Jacobsson, Staffan, and Anna Bergek. 2006. “A Framework for Guiding Policy-Makers Intervening in Emerging Innovation Systems in ‘Catching-Up’ Countries.” The European Journal of Development Research 18 (4): 687–707.

- Juma, Calestous. 2016. “Education, Research, and Innovation in Africa: Forging Strategic Linkages for Economic Transformation.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.

- Kahn, Michael Jeffrey. 2008. “Africa’s Plan of Action for Science and Technology and Indicators : South African Experience.” The African Statistical Journal 6: 163–176.

- Kraemer-Mbula, Erika, and Watu Wamae. 2010. “The Relevance of Innovation Systems to Developing Countries.” In Innovation and the Development Agenda, edited by Erika Kraemer-Mbula, and Watu Wamae, 39–65. Paris: OECD Publisjing.

- Lall, Sanjaya, and Carlo Pietrobelli. 2003. “National Technology Systems for Manufacturing in Sub-Saharan Africa.” 1st Globelics Conference, Rio de Janeiro.

- Leydesdorff, Loet, Caroline S. Wagner, Jordan A. Comins, and Fred Phillips. 2019. “Synergy in the Knowledge Base of U.S. Innovation Systems at National, State, and Regional Levels: The Contributions of High-Tech Manufacturing and Knowledge-Intensive Services.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70 (10): 1108–1123.

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke, ed. 1992. National Innovation Systems: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Pinter.

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 1998. “Why Study National Systems and National Styles of Innovation?” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 10 (4): 403–422.

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 2007. “Innovation System Research and Policy: Where It Came from and Where It Might Go.” CAS Seminar.

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 2010. National Systems of Innovation: Toward a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London/New York: Anthem Press.

- Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 2012. “Innovation in Africa – Towards a Realistic Vision.” In Challenge of African Transformation: Exploring Through Innovation Approach, edited by M. Muchie and A. Baskaran, 44–50. Pretoria: African Institute of South Africa.

- Manley, Karen. 2002. “The Systems Approach to Innovation Studies.” AJIS 9 (2): 94–102.

- Mugabe, John, and Aggrey Ambali. 2005. Africa’s Science and Technology Consolidated Plan of Action. Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Nelson, R., ed. 1993. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- NEPAD. 2014. African Innovation Outlook 2014. Pretoria: NEPAD Planning and Coordination Agency (NPCA).

- OECD/Eurostat. 2018. Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th Edition, The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities. Paris/Luxembourg: OECD Publishing/ Eurostat.

- Republic of Kenya. 2007. “The Kenya Vision 2030.” Government of the Republic of Kenya, 2007.

- Republic of Rwanda. 2012. “Rwanda Vision 2020. Revised in 2012.” MINECOFIN, Kigali.

- Sawyerr, Akilagpa. 2004. “Challenges Facing African Universities: Selected Issues.” African Studies Review 47 (1): 1–59.

- Scerri, Mario, ed. 2016. The Emergence of System of Innovation on South (ern) Africa: Long Histories and Contemporary Debates. Johannesburg: MISTRA/Real African Publishers.

- Shafaeddin, Mehdi. 2000. “What Did Frederick List Actually Say? Some Clarifications on the Infant Industry Argument.” UNCTAD Discussion Papers 149: 1–24.

- UNESCO. 2015. Mapping Research and Innovation in the Republic of Rwanda. Edited by G. A. Lemarchand and A. Tash. Paris: GO→SPIN Country Profiles in Science, Technology and Innovation Policy, vol. 4. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UNESCO. 2016. UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- United Republic of Tanzania. 1999. “The Tanzania Development Vision 2025.” Ministry of Planning.

- Vertova, Giovanna. 2014. “The State and National Systems of Innovation: A Sympathetic Critique.” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College 823: 20.

- World Bank. 2008. “Science, Technology and Innovation System Profile for Tanzania.” The World bank.