ABSTRACT

The development community has become an important financer of innovation processes in the Global South. This research scrutinizes Finnish private enterprises receiving development assistance for their innovation processes, targeting the markets of the Global South. Beyond the critical rationales, there is a lack of contextual understanding about the development impacts of private sector – focused development cooperation. The research reveals that the private sector’s role in development is heterogeneous and complex. Although, companies’ involvement has brought innovations, new actors, and funding to development cooperation, it has only fragile ties to the conventional objectives of development – to reduce extreme poverty and inequality. Innovation activities of the Finnish companies focus on rather developed markets of middle-income countries and an educated wealthy minority. Local communities have minor involvement in the design, profit sharing, or value addition of such projects, and their main role is the consumption of end products.

During the last decade, the international development nexus between the Global South and the Global North is changing rapidly. The economic development of the south and the changing geographies of poverty and wealth have played a part in fracturing the north–south axis that has historically framed development interventions and projections. The legacies of the era of global financial crises, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the increased criticism toward traditional approaches of development cooperation have substantially redirected official development aid (ODA; CONCORD Europe Citation2017; Horner and Hulme Citation2019). This has increased demands for so-called aid effectiveness (Rampa and Bilal Citation2011) based on demands of reciprocity and donor countries’ more explicit commercial self-interest (Hooli and Jauhiainen Citation2017). The focus of the international development regime has gradually come to emphasize support for the private sector taking a more active role instead of the more traditional agencies of development, including governmental actors and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs; Savelli, Schwartz, and Ahlers Citation2019). This article analyses the increasing role of Finnish private companies’ innovation processes in the country’s ODA.

Economic growth, even while it is much criticized as an ultimate objective of development cooperation, has returned to replace poverty reduction as a central objective of international development, and private sector–focused growth is considered its main engine (Mawdsley Citation2017). Several macroregional, national, and nongovernmental development organizations are expecting private sector–led development cooperation to bring new knowledge, operational models, innovations, and finances to development cooperation (Jauhiainen and Hooli Citation2019). This may happen, for example, by nurturing new investments, contributing to self-regulating markets and market efficiencies, improving individual income levels by creating new and better jobs, and generating new tax revenues that governments can use for social welfare and poverty reduction (Jeppesen Citation2005).

Despite the abovementioned positive aspirations, academic scholars have been rather critical of the increased engagement of the private sector in development cooperation (Schulpen and Gibbon Citation2002; Kolk and Van Tulder Citation2006; Davis Citation2012; Tomlinson Citation2012; Di Bella et al. Citation2013; Kindornay and Reilly-King Citation2013; Blowfield and Dolan Citation2014 McEwan et al. Citation2017; Savelli, Schwartz, and Ahlers Citation2019). The central point of this critique is that there is not enough connective fabric between the engagement of the private sector in development and the development impacts provided by them (Mawdsley Citation2015, Citation2017). The empirical evidence on the development impacts of the profit-seeking private sector involved in development cooperation on the intended beneficiaries and how the interests of various actors may meet or align are still insufficient (Tomlinson Citation2012; Kindornay and Reilly-King Citation2013). Like development impacts in general, the development impacts brought about by the private sector are extremely difficult to measure.

This article contributes to the existing literature of development and innovation studies by scrutinizing the development objectives of private companies from the Global North that have been involved in development cooperation by receiving funds from the ODA of Finland. The qualitative empirical research material consists of interviews with 24 private enterprises that have been supported by Finnish ODA through the Business with Impact (BEAM) programme in 2015–2019, participatory observation notes and document analyses of the BEAM programme, and the Finnish Development Policy Programme document (Ministry for Foreign Affairs [MFA] Citation2016). In particular, the research questions are:

What kind of development impacts are Finnish technology companies receiving ODA promoting?

Who are the main beneficiaries of Finnish private sector–focused development cooperation?

The rest of the article is organized as follows. It begins with a brief literature review of the changing paradigm of international development policy and its main critique. Second, a detailed description of the research data and methodology is provided. Thereafter, it explains how Finland’s development cooperation has undergone a significant transition and analyse the perceptions and roles of Finnish private enterprises receiving funding from Finnish ODA. The research concludes by discussing the limitations of the contemporary private sector’s development approach and making a policy recommendation for its improvement.

1. Changing paradigm of the international development nexus

The agenda for new international development includes smart aid, south–south development cooperation, innovations, technology development, financialization, competitive bidding for aid, growth-oriented entrepreneurship, and mutual business interests between the donor and the receiver (Janus, Klingebiel, and Paulo Citation2015; Villanger Citation2016; Bodenstein, Faust, and Furness Citation2017; Mawdsley Citation2018). During the last years, authors have increasingly analysed the transition of international development as a policy area toward economic growth, driven by the private sector (Mawdsley Citation2017). Although economic growth has been one of the main objectives throughout the history of modern development assistance, its impacts on the well-being of the people in the Global South are limited, and it has been distributed rather unequally (Oishi and Kesebir Citation2015). Furthermore, the pursuit of it has caused serious environmental consequences. Dividing countries into the Global North and Global South has been the most popular way of describing income and development inequalities at the global level. Although the binary division is much criticized, fluid, and constantly in transition, it has remained an important analytical framework for performing macroscale analyses of world development dynamics (Horner and Hulme Citation2019). In this research, the south–north divide is done according to the BEAM programme’s funding guidelines, where the south includes any of the developing countries eligible for ODA listed by the DAC-OECD, except China, and the north includes all the members of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC’s).

Several development agencies, including the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP Citation2012), are emphasizing the private sector as the most important driver of economic growth, a significant source of new innovations and technologies, and a major philanthropic source for social investments in development. Moreover, corporations from the Global North are increasingly interested in participating in development cooperation, as rapid economic growth and favourable demographic development have created new desirable markets in developing countries (Taylor Citation2016). Extensive distribution of and access to mobile technology have improved local access to knowledge, markets, and services. Therefore, a growing number of private-sector actors are searching for opportunities to refine their existing innovations and identify new needs for innovation in the Global South. One driver of this development is the idea that responsibility can be a source of innovation, based on conceptual discussions of responsible innovations (Halme and Korpela Citation2014). A responsible innovation is defined as a new or considerably improved implemented product, business model, process, or service, the application of which alleviates or solves various social, economic, and environmental challenges (Halme and Laurila Citation2009; Bos-Brouwers Citation2010).

The private sector has always been involved in development cooperation. However, gradually, the role of the private sector in development is intensifying and spreading to different sectors (Bodenstein, Faust, and Furness Citation2017). Development agencies and policies are constantly developing new instruments, institutional structures, programmes, priorities, and public–private partnerships to support, leverage, and finance private-sector activities in development cooperation. As will be explain further, Finland has been one of the forerunners in the contemporary transformation of ODA.

One important move toward private sector–focused development cooperation occurred in 2011 at the High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan, where the private sector was officially acknowledged as a key partner in the design and implementation of development policies and strategies (Eyben and Savage Citation2013). In a similar vein, private-sector representatives played an active role in the launch of the United Nations Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. SDGs are, globally, the most significant contemporary development strategy on which many of the OECD-DACs’ development objectives are based, including those of Finland (MFA Citation2016). The SDGs define the private sector’s role as being an active stakeholder rather than a philanthropic sponsor (Scheyvens, Banks, and Hughes Citation2016).

Di Bella et al. (Citation2013, 2) divided private-sector development approaches into three categories. First, ‘private-sector development’ includes various activities of governments, development organizations, and financial institutions supporting the business of private enterprises, including actions enhancing investments in developing countries. Second, the ‘private sector in development’ refers to the activities and roles of private enterprises that are mainly included in their core operations and business but have positive development impacts and enforce economic growth. This category is also closely linked to discussions about corporate responsibility. Although there is an abundance of definitions of corporate responsibility (Dahlsrud Citation2008), it is commonly defined as the integration of corporate self-regulation into a business’s strategy for acting responsibly with regard to social, environmental, and economic issues (Rasche, Morsing, and Moon Citation2017). Third, ‘private-sector engagement for development’ is defined as actions that are beyond the activities of the approach of the private sector in development, through which private enterprises actively look for positive development impacts. This includes, for example, inclusive business models or value chains, supporting or coordinating development activities or actively having strategic or operational aims for responsible business practices (Di Bella et al. Citation2013).

Similarly, Blowfield and Dolan (Citation2014, 23–26) distinguished the private sector as a development tool that promotes immanent development merely by having operations in developing countries from the private sector as a development agent whereby private enterprises persistently work toward having a positive development impact. However, these categories are interrelated and not mutually exclusive (McEwan et al. Citation2017). It must also be noted that the private sector includes a heterogeneous group of actors – from multinational corporations to small start-ups and family businesses – coming from the highly distinct socioeconomic contexts of the Global North and Global South.

The majority of the authors in development studies and various actors in NGOs recognize the role of a well-functioning private sector, and complex development issues require the involvement of various actors, including in the private sector. However, many of them have been critical of the new but ambiguous role of the private sector in development cooperation (Schulpen and Gibbon Citation2002; Kolk and Van Tulder Citation2006; Davis Citation2012; Tomlinson Citation2012; Kindornay and Reilly-King Citation2013; Blowfield and Dolan Citation2014; Mawdsley Citation2015, Citation2017; McEwan et al. Citation2017). According to this critique, many donors have been uncritical of how the objectives of the profit-focused private sector and development objectives fit together and how the interests of different actors may diverge or align (Tomlinson Citation2012; Kindornay and Reilly-King Citation2013). The activities in the private sector related to the development of new technology require high levels of knowledge and several skilled individuals (Hooli and Jauhiainen Citation2017). Innovation and technology development demand often-expensive product development and risk-taking, which is challenging for the global disfranchized communities living in poverty, and thus development promoting these issues may actually increase inequality (Cozzens and Kaplinsky Citation2009).

The scholars of development studies have criticized the rather uncritical faith of policy makers and donors that profit-seeking companies involved in development cooperation are somehow responsible for generating positive development impacts. As Blowfield and Dolan (Citation2014) express quite frankly, a private company ‘is no more responsible for development outcomes than a hammer is responsible for the carpenter’s thump’ (24). When the private sector is involved in development cooperation, issues such as environmental degradation, poor labour practices, and opaque tax-collection practices must be acknowledged with extra attention (Rowden Citation2011; Dhahri and Omri Citation2018). Private sector–led development cooperation that focuses on common business interests and economic development may decrease donors’ intentions to eradicate poverty and inequality, directing development cooperation instead toward enhancing business, innovation, and export opportunities for the donor country’s companies (Hooli and Jauhiainen Citation2017). Nonetheless, companies from the north generally have limited knowledge of the local context, a lack of collaboration partners, and restricted time to be present in the Global South. Furthermore, when poverty and underdevelopment are regarded as a source of innovations and potential business opportunities, the aim of the development easily becomes highly ideological, with an emphasis on competitive and entrepreneurial individuals rather than on communities achieving common goals (Hooli Citation2016, 69).

2. Research data and methodology

The empirical data of this research consist of triangulation of various data sources, including public documents, interviews, and participatory observations. Triangulation is relevant to generalize the subjectivity of qualitative analyses and to gather deeper knowledge about the validity and reliability of quantitative analyses (Hartley and Sturm Citation1997). In policy documents, particular attention is paid to Finland’s Development Policy (MFA Citation2016), which is the guiding document of Finnish development cooperation. The materials on the BEAM programme is compiled by interviewing representatives of 24 private enterprises that received funding through the programme, acting as a member of a coordination team and conducting participatory observation of one BEAM-funded project, Geospatial Business Ecosystem in Tanzania 2016–2018, and engaging in participatory observation of five public events of the programme (2017–2019). In addition, the documents Mid-term Development Evaluation of the Business with Impact (BEAM) Programme (MFA Citation2017) and Final Report of Developmental Evaluation of Business with Impact (BEAM) Programme (MFA Citation2019) were analysed.

Commonly, government strategy and policy documents are created by the government to guide and anticipate future development (Spradley Citation2016). For this research, these documents represent institutional views, broader strategic and operational directions, and larger changes in the government concerning development policy. Flick (Citation2006) denoted that public documents represent a form of truth developed for a certain purpose. Hence, it is important to reveal for what purposes they are developed and by whom. Furthermore, the public events of the BEAM programme offered valuable insights into and feedback about the implementation of the programme, as both BEAM coordinators and several fund-receiving companies were involved.

The institutional views of the development policy are compared to the perspectives and operative actions of 24 Finnish private-sector enterprises that received funding from the BEAM programme. BEAM was the first joint programme (2015–2019) between Business Finland, which is the national funding agency for technology and innovation, and the MFA of Finland. It was also the first programme directing ODA funds solely to the Finnish private sector. The objective of the BEAM programme was to create new and sustainable businesses and innovations in the Global South. The programme aimed to accelerate private companies and other actors from Finland to generate innovations for tackling global development challenges and, with these innovations, to develop sustainable and successful businesses in developing countries and Finland.

Interview data were collected in 21 semistructured interviews conducted between May 2017 and December 2019. In addition, three companies participated in the BEAM project (2016–2018) coordinated by the author at University of Turku. These three companies were interviewed and asked questions similar to those included in the semistructured interviews. Thus, overall interview data included 24 companies. Moreover, participatory observation (see, e.g. Clark et al. Citation2009) during four business visits of the three companies involved in the University of Turku BEAM project in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, Kenya (2016–2018) were done.

The interviewed persons from the companies were commonly CEOs (Chief executive officer), deputy CEOs, or coordinators of the BEAM projects. All interviews were audio-recorded, and notes were taken during the interviews. Afterward, the interviews were transcribed and arranged in an Excel file according to the research themes. The research material from the participatory observation included field notes and photos. All the qualitative empirical materials were analysed using content analysis, in which the content was systematically coded into patterns and themes that were significant for the study questions.

According to the final report of the BEAM, the programme funded 151 projects altogether (MFA Citation2019). The total budget of the projects was around 58,800,000 euros, of which the public funding was worth 31,200,000 euros. The other 27,600,000 euros consisted of applicants’ self-funding; 116 of the projects were led by private enterprises, and 44 were led by research institutions (see ). However, a majority of the projects led by the research institute were aimed at enhancing business or innovation ecosystems in developing countries, and only a few of the projects focused on research.

Table 1. BEAM programme funding data (MFA Citation2019).

Most of the enterprises with representatives interviewed in this research were very small in terms of their employment. Eighteen of the companies had 20 or fewer employees, and 10 of those had 10 or fewer. Five of the companies had fewer than 200 employees, and one had about 750 employees. The companies were high technology companies involved in the development of such products as mobile teaching and gaming applications (n = 6), remote sensing technologies (n = 3), and clean technology solutions (n = 3). Four of the companies were dealing with water purification or sewage treatment, and two with the energy sector. Other individual cases were related to tourism, agriculture, construction, health services, chemistry, and industry in general.

3. Finnish development cooperation in transition

Development policy is an important part of Finland’s foreign and security policy, and development cooperation is the most important means by which to implement it. In Finland, the MFA steers development policy. Finland started providing ODA to less developed regions more than 50 years ago. ODA was included in the government budget for the first time in the early 1960s. In 1970, the Finnish government committed to comprise 0.7% of gross national income in ODA, and in 1975, it gained membership in the DAC of the OECD (MFA Citation2016). So far, Finland has never achieved this target.

Over the last two decades, the main aim of Finland’s development policy has been to fulfil United Nations development strategies. The current development policy and the development cooperation of Finland are guided by the UN’s SDGs. The goal is to promote socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable development and foster peaceful societies all over the world. The ultimate goal of Finland’s Development Policy is to eradicate extreme poverty and inequality (MFA Citation2016). However, during the previous government administration (2015–2019), Finnish development policy underwent its most significant reform since its establishment in the name of fostering its aid effectiveness. Concretely, this reform has meant that Finland has (a) substantially reduced its development aid budget and (b) emphasized the role of the private sector and innovation in development cooperation, as well as that (c) the objectives of development assistance has been increasingly decoupled along with the international trade agenda.

The most drastic turn in Finland’s development policy happened in 2016, when the government slashed about 40% of the overall development cooperation budget (about 200,000,000 euros). The government also decided to break its pattern of channelling revenue from emissions trading into development cooperation. The result has been a substantial reduction of funds; for example, in 2014, 69,000,000 euros’ worth of emissions trading revenue was diverted into development cooperation. Afterward, the budget of ODA slightly increased again, and in 2020, Finland’s development cooperation appropriations amounted to 1,031,000,000 euros, which is, on average, 0.45% of the gross national income during the spending limit period. Of this share, 673,000,000 euros are allocated to bilateral cooperation, and the remaining development cooperation funding of 358,000,000 euros includes the costs of receiving refugees, Finland’s share of the European Union’s development cooperation budget, and other payments classified under development assistance in several administrative areas (MFA Citation2020).

The development policy launched in 2016 (MFA Citation2016) was the first in which actors from private enterprises played a key role. The minister of foreign trade and development in charge of preparing this policy, Kai Mykkänen, stated in a radio interview, ‘From now on, the central evaluation criteria for all of Finland’s development projects will be how well those projects manage to create new market opportunities or operational environments for Finnish enterprises’ (Radio Suomi Citation2016).

Generally, private-sector activities in development cooperation are part of the government’s Team Finland activities. The purpose of Team Finland is to bring together all publicly funded internationalizing services available in Finland. The Development Policy states:

Commercial cooperation with developing countries to promote sustainable development is supported by Team Finland activities, which will be further developed … Information about services and forms of funding available for companies will be improved. Start-up companies’ contacts with developing countries will be reinforced. The strengthening of societies and business environments in developing countries through Finnish development cooperation will also benefit Finnish companies more generally. (MFA Citation2016, 39–40)

The main government institution supporting the private sector in developing cooperation is the national development finance institution Finnfund. It provides capital investments and loans directed to developing regions through private companies that are obligated to practice corporate social responsibility. According to the Development Policy (MFA Citation2016), Finnfund ‘supports projects with a Finnish interest, which may involve a goal important for Finland, or a Finnish company’ (42).

Ylönen (Citation2012) denoted that the ‘Finnish interest’ (208) is a confusing concept, as it may be interpreted in terms of Finnish development policy priorities or Finnish commercial benefits. According to him, in practice, it has been used mainly to refer to the commercial interest of Finland. Moreover, several Finnish NGOs have been concerned about Finnfund’s private equity investments through tax havens and increasingly directing its actions away from developing countries (Finnwatch Citation2019).

Simultaneously to the budget cuts of ODA, the public financing for Finnfund was increased remarkably, as it received 130,000,000 euros in supplementary funding that was converted from traditional grant aid. This was a major increase, as before the recent financing, the state’s total contribution for Finnfund since its 1980 establishment had been about 165,000,000 euros. During the latest negotiations, Finnfund requested a grant of 40,000,000 euros, and thus the increase was more than triple what it had requested.

The other main instruments for private-sector actors in development cooperation are the Finnpartnership programme, which supports common development projects between actors from Finland and developing countries, and the BEAM programme. As its name suggests, BEAM’s objective was to support businesses with development impacts. During the application process, applicants were required to define their expected development impact in a separate attachment. In principle, although MFA-ODA projects should have a clear development impact, Business Finland and private companies are not obligated to demonstrate the development impacts of their actions. Administratively, the BEAM programme was coordinated by Business Finland, which is also its main funder. Business Finland did not have previous experience participating in development cooperation. The MFA does not fund all BEAM projects, but data on the specific contributions by these organizations are not publicly available.

Moreover, there is a strong ethos to look actively for ways to create new market opportunities for Finnish companies through the ODA, as the Development Policy (MFA Citation2016) claims:

Work to identify and develop new financial investment opportunities will be launched without delay. It will be a way to increase direct capital investments and loans to developing countries, particularly in the fields of clean technology, sustainable water management, energy and food production, and combating climate change. (MFA Citation2016, 43)

4. Private-sector development for whom?

According to Finland’s Development Policy (MFA Citation2016), the partners for bilateral development cooperation are among the least developed countries or are classified as fragile states in the OECD-DAC list of ODA recipients (OECD Citation2019). The ministry expects that aid-receiving countries will depend on external aid for a long time. Due to the rapid economic development of the Global South, some of the partner countries are becoming middle-income countries. Therefore, the government is withdrawing gradually from bilateral development cooperation and focusing on other types of collaboration, such as providing expertise, focusing on research and innovation, investing, and increasing commercial cooperation.

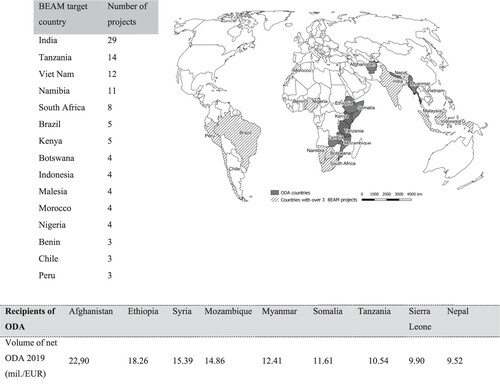

Over the last decade, Finland has withdrawn from several bilateral development partnerships. In addition to the economic progress of partner countries and the overall decrease in Finland’s state budget for development cooperation, the third main reason for this withdrawal has been the strategic decision for Finland to focus on fewer recipients, to increase the development impacts on the chosen countries. This is a general trend in OECD-DAC policies, which has encouraged donors to focus their funds and efforts on fewer countries and sectors to improve results and performance (e.g. OECD Citation2009). Currently, Finland provide bilateral development mainly to 11 countries: Somalia, Zambia, Kenya, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Syria, Mozambique, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, and Nepal (see ). Moreover, Finland provides small amounts of support to the Palestinian region, the Middle East, Eritrea, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Figure 1. Recipients of Finnish ODA and the volume of assistance (MFA Citation2020) compared to the locations of the 113 BEAM projects.

Unlike the carefully selected bilateral development partners, the target countries of the BEAM programme can be any of the developing countries eligible for ODA listed by the DAC-OECD, except for China, where Business Finland has its own programme. The private sector’s geographical focus in BEAM projects is significantly wider than and distinct from the geographical focus defined in Finland’s Development Policy. When the official partners of development were carefully selected least-developed countries, BEAM projects clearly focused on more developed countries, and the geographical focus was much more scattered. indicates the target countries of BEAM projects, in relation to nine official bilateral development cooperation countries. Altogether, the figure indicates the locations of 113 BEAM projects. The rest of the projects did not yet have any country-specific location, or any emphasized regions, like southern Africa or the Middle East.

This result shows that the interests of private companies are targeting significantly more developed countries than the ODA of Finland is. Over half of the 113 BEAM projects (51%; Namibia n = 11, South Africa n = 8, Brazil n = 5, Botswana n = 4, Malaysia n = 4, and Peru n = 3) were located in countries classified as upper-middle income countries in the DAC-OECD list of ODA recipients (OECD Citation2019) or as high-income countries, as Chile (n = 3) does not belong to the DAC-OECD list but is classified as a high-income country. More than one-third of the projects (34%) targeted lower-middle-income countries. Overall, India was by far the most popular project destination, as more than one out of every four projects (n = 29) was targeted there. Other lower-middle-income countries included Vietnam (n = 12), Kenya (n = 5), Nigeria (n = 4), Indonesia (n = 4), and Morocco (n = 4). Only 15% of BEAM projects were targeted at the least developed countries (Tanzania n = 14 and Benin n = 3).

The interest in more economically developed countries and middle-income countries was also evident in the 24 interviews. Most often (n = 8), when asked why the BEAM project was targeting a particular country, the reason was explained using the positive prospects of market opportunities. As one interviewee explained, ‘We chose to focus on India because we believe to find growing markets from there, as it is a bit more developed of a developing country’ (Interview June 6, 2017).

Moreover, an existing collaboration partner (n = 8) and previous experiences (n = 7) from the target country were mentioned as important factors in choosing a particular location. It became very evident that, unlike in traditional development cooperation, the enterprises engaging in development cooperation function with the market logic that profitability is the first priority, along with other requirements such as operating rather stable and developed markets and having trusted collaboration partners. Therefore, private-sector business activities in this type of development cooperation rarely target least-developed countries.

Perhaps more important than the actual geographical location of projects is to analyse with whom the companies are collaborating and who is included in their projects, as many middle-income countries have highly uneven income structures. In general, companies had only loose connections to the target countries, and in particular, local communities were inadequately included in the projects. When asked who their main cooperation partners in the target communities were, enterprises most often regarded local companies – which generally acted as local agents, customers, or intermediating consultants between the enterprise and the local customer – as the most important contacts. The second most important cooperation partners were public-sector actors such as ministries and municipalities. Most often, they were the customers of the companies’ end products. Therefore, the most important local cooperation partners were already skilled individuals who had a degree from an institute of higher education. The third most common answer for the most important contact in the target country was the local Embassy of Finland. The role of local communities in the projects genuinely was limited, and only a few companies had considered their strategic or operational activities from the perspective of inclusive development (Gupta, Pouw, and Ros-Tonen Citation2015). Just two respondents mentioned local communities as their customers; none of the enterprises regarded them as among the most important contacts.

5. Private-sector development for what?

According to the interviews, 75% (n = 18) of the companies responded that their development impacts were instrumental and directly related to their technology or the service they were developing. The development process for the products featured in BEAM can be divided into two categories: companies that were making their technology or service available for developing countries mainly by expanding their markets there and companies that were developing new products to solve some of the challenges occurring in developing countries. The end products varied from water purification and security to Internet security, automated data collection, and using open data in remote sensing applications. Some companies focused on sanitation and waste recovery, whereas others were creating new wood-construction solutions for urbanization and new franchise models for organic smallholders. One company was developing an educative mobile gaming platform, and another was working on an Airbnb-like platform to provide backpackers with accommodations and experiences living in local communities.

Most often, the technology was expected to solve technical challenges related to social, economic, or environmental issues occurring in developing countries, as the following three examples illustrate: ‘We will provide electricity and light for all communities that improves security’ (Interview May 15, 2018). ‘Our objective is to secure fresh water for all’ (Interview May 31, 2017). ‘Well, that is a good question. … Most probably, it is to improve sanitation and recycle bio waste’ (Interview August 28, 2017).

The government (MFA Citation2016, 40) regards Finnish private companies as key partners in development cooperation. In particular, their role is considered significant for meeting the second priority area targets in the Development Policy: ‘Developing countries’ own economies have generated more jobs, livelihood opportunities and well-being’ (MFA Citation2016, 15). At the beginning of the interviews, none of the companies mentioned development impacts as the main objectives of their actions when asked ‘What are the overall objectives of your BEAM project?’ All of the projects were in the early stages, and the main objectives were related to accessing the developing countries’ markets, establishing networks, and gaining additional funding for the companies’ research and development (R&D). Several of the respondents admitted frankly that their main motivation for their involvement in the BEAM project was not to enter new markets in developing countries but that it was related to the rather easy access to public R&D funding to develop their products:

Let’s say we did not care about the geographical location of the project when the Finnish higher-education institute approached us to join their project consortium. We needed funds for our R&D, and public funds are competitive in Finland. Thus, for us, BEAM provided access to public funding, and naturally, it does not matter whether our customers come from Africa or Germany, although developing countries are not our first priority. (Interview June 2, 2017)

Interestingly, although the interviewed enterprises considered development impacts relevant for their strategic activities, defining the actual development impact clearly was challenging for most of them. The commonly mentioned positive development impacts were attached to general economic growth and job creation in the developing markets, as well as in the company’s home country. Economic benefits to their customers were expected to trickle down more broadly to the societies. These views are in line with the Finnish government’s statements, as explained in the beginning of this section. Savelli and her colleagues (Citation2019) identified similar findings when they researched the role and motivations of Dutch private companies involved in development cooperation in Kenya.

Another major development impact was related to the overall discourse on corporate responsibility. The Finnish companies in this research were aiming to promote gender equality, apply renewable energy, and support fair working conditions in their activities in the developing countries. Corporate responsibility was considered a built-in set of values for companies coming from Nordic countries. As one company reported, ‘We are looking for good Finnish practices to operate’ (Interview June 1, 2017). This is in line with the development policy because operationally, the enterprises are expected to fulfil this objective by developing new, responsible innovations, as the next quotation explains:

Finnish companies are encouraged to provide commercially viable, development-enhancing solutions to fast-growing developing country markets. Finnish know-how [emphasis added] in the fields of clean technology and bioeconomy can boost the implementation of a circular economy in developing countries. This is a way to support climate change mitigation and sustainable development through ordinary business activities [emphasis added]. (MFA Citation2016, 39)

Both the development policy and companies emphasized the creation of new local employment as one of the private sector’s main strengths, as compared to ODA projects that are more traditional. However, among the companies interviewed in this study, the generation of new employment was very modest, the projects added only weak local value, locals were insufficiently involved in the R&D of these products, and the products were also manufactured elsewhere. Only a couple of enterprises employed locals directly, and those were local experts with existing high skill levels.

Only eight of the interviewees stated that local actors had taken part in their companies’ product development. In five of these cases, the local actors were small consultant companies, whose role was to assist with localizing the technologies and helping with local bureaucracy. The next statement was very illustrative, in response to the question ‘Were local actors involved in the R&D of the product you developed in the BEAM project?’ One company responded, ‘No. We visited Namibia and identified the local needs. Now, we are developing a product for those needs. However, the product also is suitable for other contexts’ (Interview May 29, 2017). Part of the reason why local communities were not involved in BEAM projects was related to the funding guidelines of the BEAM projects, as only Finnish actors are eligible for this funding. In relation to this point, several of the companies perceived that their main challenge was precisely the lack of local ownership. For that reason, entering new markets of developing countries had been extremely challenging for them.

As most of the projects were in rather early phase, it was unclear how the lack of local involvement affected the innovations’ application in very different socioeconomic contexts. However, researchers have been rather critical towards the idea of transferring knowledge from one place to another because knowledge developed elsewhere may not be appropriate for the economic, social, and historic conditions of another place (Ibert Citation2007). The procedural approach to knowledge is closely linked to an understanding of knowledge as an indivisible part of fluid social practices. Thus, instead, knowledge is created interactively and is partly tacit; thus, it must be translated when used in different local and historical contexts (Ziervogel et al. Citation2021). Knowledge creation is considered a complex spatiotemporal process evolving from the interpretations and interactions of people from various scales and sectors (Livingstone Citation2010).

Four of the interviewed companies aimed to develop platforms for local third-party developers to help local communities gain added social or economic value and provide a platform for local business. These platforms were related to learning, agricultural productivity, tourism, and improved data management, as these respondents explained:

Our initial thought was to provide a platform that would enable everyone to be able to learn. (Interview May 29, 2017)

We help local companies to access global markets and offer work with good labour rights and working conditions. (Interview August 29, 2017)

Well … our company is providing a new service that creates employment, knowledge, and modern know-how. This is a new way of thinking about business development based on analytical knowledge. Our aim is to create Web pages out of complicated user interfaces that will completely change our customers’ commercial units opportunities to affect their own business. (Interview May 30, 2017)

6. Conclusion and discussion

In this research, I scrutinized Finnish private companies that received funds from Finland’s ODA for their innovation activities in the Global South. In recent years, Finland, like many other OECD-DAC countries, has elaborated a need for major transformation of ODA. In practice, this transformation has meant major cuts from the budgets of NGOs and projects that are more traditional and a strategic reversal towards innovation and private sector–focused development cooperation. Political rhetoric has also changed; now, decision-makers’ speeches and development policies are increasingly explicit about the funders’ self-interest and demands for reciprocity being major drivers of development policy.

Due to paradigm changes in the development regime and accelerated criticism of traditional approaches to development assistance, it seems rather inevitable that the private sector’s role will be expanded in the future. The international development community is developing new programmes and modalities to amplify private-sector engagement and involvement with development activities. Evidently, some responsible innovations, such as new and improved medicines, sanitation and water purification, and solar power, have solved technical development issues, and private-sector involvement in development has led to some win-win situations between technology providers and their clients. In addition, the complex issues surrounding development demand wider participation from different actors, including private enterprises and innovation developers from the Global North. The BEAM is a good example of a development programme that has successfully brought in new actors that would not otherwise have been involved in development cooperation and that have contributed their know-how and labour input. Furthermore, Business Finland and participating private companies have made significant additional financial contributions.

However, the beneficiaries of the BEAM programme mainly have been the Finnish private companies that received government funding. Beyond the technical innovations the private companies’ development impacts were ambiguous and rather modest. It was unclear how these projects managed to reach the agents for whom development cooperation was meant in the first place. At its best, the development impacts for the local communities were based on instrumental support that provided technical and economic solutions for some individuals in some places but left out the complex, nonlinear political, social, and economic preconditions that produced underdevelopment and inequality in the first place.

Companies had only weak linkages to the main objectives of Finnish development policy – to reduce inequality and poverty. Unlike the few carefully selected least-developed countries that are the strategic focus of Finland’s ODA, most of the BEAM projects were located in middle-income countries, and the geographical focus of the programme is very scattered. Moreover, the companies focusing on the least-developed countries had only weak linkages to the local communities’ innovation capacity because their collaboration partners came from the educated, wealthy minority. Most of the companies stated that their first priority was to do profitable business and that the development impacts would be a possible bonus and beneficial for their public image.

For a long time, development organizations and researchers have been quite unanimous in stating that all development approaches must be based on community development and inclusive development – in which community members take collective actions and generate solutions to common challenges through a bottom-up approach and local empowerment (McEwan et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, the government of Finland emphasizes local ownership, bottom-up processes, and empowerment in its Development Policy (MFA Citation2016, 13). However, the findings reveal that local communities were inadequately involved in the design or operationalization of the innovation processes financed by the BEAM programme. The increase in local employment was very modest. The products were not manufactured in the Global South, and local added value has been scarce. The expected role of local communities was to be consumers, local agents, or resellers of the end products.

Although the private-sector actors are highly diverse, Finnish companies and the government share a strong belief that responsible capitalism, market forces, and innovations are the central answer to contemporary development issues. Significant weight is placed on responsible innovations, market mechanisms, and improved corporate responsibility, undermining the fundamental economic, environmental, and social changes the world needs. Finland increasingly is using public funds for development cooperation to fund the expansion of domestic enterprises to developing countries. Similar development also has been evident elsewhere, such as in the United Kingdom and New Zealand (Mawdsley Citation2015). Moreover, innovation development by private enterprises currently is preserved in ODA very homogeneously. However, companies that have opened up their technology platforms for local third-party developers may have much stronger and inclusive development impacts than companies that only slightly adjust or sell their technologies developed elsewhere in developing countries do. Part of the reason for this may be the low critical mass of Finnish companies interested in developing countries.

Lastly, as a policy recommendation, more discussion is needed on new kinds of modalities for intersectional collective-learning processes to enhance the development impacts of private-sector innovation processes in the Global South. The results indicate that, although private companies lack capacity and local knowledge, they are willing and would benefit from larger cooperation models. Thus, rather than supporting individual’ enterprises and actions sparsely, there is a need to support the evolution of larger ecosystems involving private sector actors from the Global South, as well as universities, NGOs, governmental actors, the international development community, and local communities in well-selected and carefully defined geographic areas. This kind of cooperation could better pair the needs of the target communities and structural support for local governments with the technological know-how of foreign companies to enhance the impact of the cooperation on local job creation, capacity building, and ownership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blowfield, M., and C. S. Dolan. 2014. “Business as a Development Agent: Evidence of Possibility and Improbability.” Third World Quarterly 35 (1): 22–42.

- Bodenstein, T., J. Faust, and M. Furness. 2017. “European Union Development Policy: Collective Action in Times of Global Transformation and Domestic Crisis.” Development Policy Review 35 (4): 441–453.

- Bos-Brouwers, H. 2010. “Corporate Sustainability and Innovation in SMEs: Evidence of Themes and Activities in Practice.” Business Strategy and the Environment 19: 417–435.

- Clark, A., C. Holland, J. Katz, and S. Peace. 2009. “Learning to See: Lessons from a Participatory Observation Research Project in Public Spaces.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 12 (4): 345–360.

- CONCORD Europe. 2017. 10 Point Roadmap for Europe on the Role of the Private Sector in Development. https://concordeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Private-sector-2017-online-final.pdf?1fdb40&1fdb40&7c2b17&7c2b17.

- Cozzens, S. E., and R. Kaplinsky. 2009. “Innovation, Poverty and Inequality: Cause, Coincidence, or Co-Evolution?” In Handbook of Innovation and Developing Countries: Building Domestic Capabilities in a Global Setting, edited by B.-Å. Lundvall, K. J. Joseph, C. Chaminade, and J. Vang, 57–82. Cheltenham, CH: Edward Elgar.

- Dahlsrud, A. 2008. “How Corporate Social Responsibility is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 15: 1–13.

- Davis, P. 2012. “Re-thinking the Role of the Corporate Sector in International Development.” Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 12 (4): 427–438.

- Dhahri, S., and A. Omri. 2018. “Entrepreneurship Contribution to the Three Pillars of Sustainable Development: What Does the Evidence Really Say?” World Development 106: 64–77.

- Di Bella, J., A. Grant, S. Kindornay, and S. Tissot. 2013. The Private Sector and Development: Key Concepts. Ottawa: North-South Institute.

- Eyben, R., and L. Savage. 2013. “Emerging and Submerging Powers: Imagined Geographies in the New Development Partnership at the Busan Fourth High Level Forum.” The Journal of Development Studies 49 (4): 457–469.

- Finnwatch. 2019. Finfundin sijoitusrahaston hallintoyhtiö kiersi veroja [The Unit Trust of Finfund Evaded Taxes], May 5. https://finnwatch.org/fi/uutiset/623-finnfundin-sijoitusrahaston-hallinnointiyhtioe-kiersi-veroja.

- Flick, U. 2006. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

- Gupta, J., N. R. Pouw, and M. A. Ros-Tonen. 2015. “Towards an Elaborated Theory of Inclusive Development.” The European Journal of Development Research 27 (4): 541–559.

- Halme, M., and M. Korpela. 2014. “Responsible Innovation Toward Sustainable Development in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Resource Perspective.” Business Strategy and the Environment 23 (8): 547–566.

- Halme, M., and J. Laurila. 2009. “Philanthropy, Integration or Innovation? Exploring the Financial and Societal Outcomes of Different Types of Corporate Responsibility.” Journal of Business Ethics 84 (3): 325–339.

- Hartley, R. I., and P. Sturm. 1997. “Triangulation.” Computer Vision and Image Understanding 68 (2): 146–157.

- Hooli, L. 2016. Adaptability, Transformation and Complex Changes in Namibia and Tanzania: Resilience and Innovation System Development in Local Communities. Turku: Annales Universitatis Turkuensis A II 321.

- Hooli, L. J., and J. S. Jauhiainen. 2017. “Development Aid 2.0—Towards Innovation-Centric Development Co-operation: The Case of Finland in Southern Africa.” 2017 IST-Africa Week Conference (IST-Africa).

- Horner, R., and D. Hulme. 2019. “From International to Global Development: New Geographies of 21st Century Development.” Development and Change 50 (2): 347–378.

- Ibert, O. 2007. “Towards a Geography of Knowledge Creation: The Ambivalences Between ‘Knowledge as an Object’and ‘Knowing in Practice’.” Regional Studies 41 (1): 103–114.

- Janus, H., S. Klingebiel, and S. Paulo. 2015. “Beyond Aid: A Conceptual Perspective on the Transformation of Development Cooperation.” Journal of International Development 27 (2): 155–169.

- Jauhiainen, J. S., and L. Hooli. 2019. Innovation for Development in Africa. London: Routledge.

- Jeppesen, S. 2005. “Enhancing Competitiveness and Securing Equitable Development: Can Small, Micro, and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) Do the Trick?” Development in Practice 15 (3–4): 463–474.

- Kindornay, S., and F. Reilly-King. 2013. “Promotion and Partnership: Bilateral Donor Approaches to the Private Sector.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études du Développement 34 (4): 533–552.

- Kolk, A., and R. Van Tulder. 2006. “Poverty Alleviation as Business Strategy? Evaluating Commitments of Frontrunner Multinational Corporations.” World Development 34 (5): 789–801.

- Livingstone, D. N. 2010. Putting Science in its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Mawdsley, E. 2015. “DFID, the Private Sector and the Re-Centring of an Economic Growth Agenda in International Development.” Global Society 29 (3): 339–358.

- Mawdsley, E. 2017. “Development Geography 1: Cooperation, Competition and Convergence Between ‘North’ and ‘South’.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (1): 108–117.

- Mawdsley, E. 2018. “Development Geography II: Financialization.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 264–274.

- McEwan, C., E. Mawdsley, G. Banks, and R. Scheyvens. 2017. “Enrolling the Private Sector in Community Development: Magic Bullet or Sleight of Hand?” Development and Change 48 (1): 28–53.

- MFA (Ministry for Foreign Affairs). 2016. Finland’s Development Policy. http://formin.finland.fi/public/download.aspx?ID=155593&GUID=%7B6E4F9704-3A6B-4207-977D-0FBC44E084AF%7D.

- MFA (Ministry for Foreign Affairs). 2017. Developmental Evaluation of Business with Impact (BEAM) Programme: Mid-term Evaluation. http://formin.fi/public/default.aspx?contentid=365332&nodeid=49312&contentlan=2&culture=en-US.

- MFA (Ministry for Foreign Affairs). 2019. Final Report of Developmental Evaluation of Business with Impact (BEAM) Programme. https://um.fi/documents/384998/0/BEAM+Developmental+Evaluation+report+2019+%281%29.pdf/f61855fa-db34-0664-9af8-940e46a763c3?t=1576006774001.

- MFA (Ministry for Foreign Affairs). 2020. Development Cooperation Appropriations 2020. https://um.fi/documents/35732/0/finlands-development-cooperation-appropriations-2020.pdf/37bbf9ef-d33f-9c37-bb19-2c0a5cfae09d?t=1588162597793.

- OECD. 2009. Better Aid: Managing Aid Practices of DAC Countries. https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/35051857.pdf.

- OECD. 2019. DAC List of ODA Recipients. Effective for reporting on aid in 2018 and 2019. http://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/DAC-List-of-ODA-Recipients-for-reporting-2018-and-2019-flows.pdf.

- Oishi, S., and S. Kesebir. 2015. “Income Inequality Explains Why Economic Growth Does not Always Translate to an Increase in Happiness.” Psychological Science 26 (10): 1630–1638.

- Radio Suomi. 2016. Interview of the Foreign Minister of Finland Kai Mykkänen, February, 12.

- Rampa, F., and S. Bilal. 2011. “Emerging Economies in Africa and the Development Effectiveness Debate.” European Centre for Development Policy Management 107: 11–107.

- Rasche, A., M. Morsing, and J. Moon, eds. 2017. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategy, Communication, Governance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rowden, R. 2011. India’s Role in the New Global Farmland Grab. New Delhi, India: GRAIN and Economics Research Foundation.

- Savelli, E., K. Schwartz, and R. Ahlers. 2019. “The Dutch Aid and Trade Policy: Policy Discourses Versus Development Practices in the Kenyan Water and Sanitation Sector.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37 (6): 1126–1147.

- Scheyvens, R., G. Banks, and E. Hughes. 2016. “The Private Sector and the SDGs: The Need to Move Beyond ‘Business as Usual.” Sustainable Development 24 (6): 371–382.

- Schulpen, L., and P. Gibbon. 2002. “Private Sector Development: Policies, Practices and Problems.” World Development 30 (1): 1–15.

- Spradley, J. P. 2016. Participant Observation. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Taylor, I. 2016. “Dependency Redux: Why Africa is Not Rising.” Review of African Political Economy 43 (147): 8–25.

- Tomlinson, B., ed. 2012. Aid and the Private Sector: Catalysing Poverty Reduction and Development? Reality of Aid. Quezon City, Philippines: IBON International.

- UNDP. 2012. Strategy for Working with the Private Sector. www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/Partnerships/Private%20Sector/UNDP-Private-Sector-Strategy-final-draft-2012.pdf.

- Villanger, E. 2016. “Back in Business: Private Sector Development for Poverty Reduction in Norwegian Aid.” Forum for Development Studies 43 (2): 333–362.

- Ylönen, M. 2012. “Finland, Transformation of the Finnish Development Policy: The Private Turn.” In Aid and the Private Sector: Catalysing Poverty Reduction and Development? Edited by B. Tomlinson. Reality of Aid Report, 205–210. Quezon City: IBON International.

- Ziervogel, G., J. Enqvist, L. Metelerkamp, and J. van Breda. 2021. “Supporting Transformative Climate Adaptation: Community-Level Capacity Building and Knowledge co-Creation in South Africa.” Climate Policy, 1–16.