ABSTRACT

The Agricultural Innovation System perspective highlights the importance of interaction for learning and innovation, but so far little research is done on the cultural differences of farmers and the effect this has on interaction, knowledge sharing and innovation. We took a cultural perspective to better understand local interaction, knowledge sharing and learning dynamics, and uptake of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in Bangladesh where the Department of Agricultural Extension organizes Farmer Field Schools (FFS) for IPM. However, the success of the FFS approach at farmer level is quite diverse. We coupled an ethnographic study with an analysis, based on Cultural Theory, to identify the cultural pattern of behaviour, underlying preferences of social organization, and the effect this has on pest management innovation in two farmer communities. Findings showed that in one village with strong group solidarity, farmers tended to share knowledge in a wide network, and started to apply IPM while reducing pesticide use. In the other community, individualism and fatalism prevailed and farmers only shared knowledge within their close network, distrusted outsiders and continued to rely on pesticides. We conclude that it is important to include cultural studies in cross-disciplinary research and design of local innovation interventions.

1. Introduction

In many developing countries, agricultural innovations aim to overcome development challenges and those facing farmers trying to earn a livelihood. This is related to agro-ecological, market and/or regulatory conditions or farmers’ capacities and resources. The Agricultural Innovation System (AIS) perspective argues the need for collaborative interaction among multiple actors in order to identify and analyse these problems and devise innovations that are technically sound, affordable and understandable to farmers, and coherent with government policies (Schut et al. Citation2019). The AIS perspective recognizes the role of learning (Hall et al. Citation2006) and innovation intermediaries in effective networking between actors with different knowledge, interests and power resources (Leeuwis and Aarts Citation2011). The existing innovation literature emphasizes the role of innovation intermediaries in facilitating multi-actor interactions (Van Paassen et al. Citation2013; Kivimaa et al. Citation2019), however, less attention has been given to the influence of culture and inter-cultural differences between actors involved in these interactions and in learning and innovation processes (Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2008; Smith Citation2010; Lie and Witteveen Citation2013, Citation2019). To enhance inclusive innovation in agriculture, we need more understanding of the influence of culture on the performance of innovation tasks by different actors, and the overall innovation patterns that emerge in a specific context. In this paper, we study the influence of cultural differences on the innovation dynamics of eggplant pest management in two farmer communities in Bangladesh. This research was part of an interdisciplinary research project ‘to enhance agricultural production systems towards sustainable food security in Bangladesh’, and aimed to investigate the technical and social constraints on the adoption of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), introduced via Farmer Field School (FFS).

Scientists, policy makers and international development agencies increasingly promote IPM, because of the overuse and misuse of pesticides (Oerke Citation2006; Parsa et al. Citation2014; Chakraborty, and Newton Citation2011). Since 1960, agricultural production has doubled worldwide, due to high-yielding varieties and improved water and soil management but these newly developed agro-ecosystems are also more susceptible to weeds and pests (Popp, Pető, and Nagy Citation2013). This has led to more effective mechanically weeding and a 15–20 fold increase in pesticide use worldwide (Oerke Citation2006). Further production potential could be achieved through better pest management, especially if we can curb the overuse and misuse of pesticides that lead to pest resistance and damage to pests’ natural enemies in the environment (Oerke Citation2006; Parsa et al. Citation2014; Chakraborty, and Newton Citation2011). Pesticide use also creates environmental externalities and health hazards, another reason why IPM is widely recommended as a safer, environment-friendly and more cost-effective approach to pest management (Popp, Pető, and Nagy Citation2013).

An IPM Farmer Field School (FFS) approach was developed as a participatory learning approach for farmers to learn about IPM and integrated crop management, which involves taking into account a complex range of issues, such as pest dynamics and soil fertility management (Gallagher, Ooi, and Kenmore Citation2009). IPM-FFS is a time-intensive learning approach that can last for 14 weekly sessions of an average of 4 h each, covering a full season activities for a particular crop (such as vegetables or rice) executed by the farmers, with support from extension officers. In IPM-FFS, partly illiterate farmers implement and closely observe experiments and compare the results to their ‘ordinary’ farm practices; they jointly discuss experiment outcomes while also receiving education on ‘abstract’ issues such as nutrient cycles, rotation schemes, pest life cycles, beneficial insects, etc. (Gallagher, Ooi, and Kenmore Citation2009; Van de Fliert, Dilts, and Pontius Citation2002).

Despite a strong conceptual grounding and substantial promotion, IPM practices have not been adopted on a large scale. A survey amongst 413 IPM professionals and practitioners in 96 countries (Parsa et al. Citation2014) highlighted 6 sets of obstacles for IPM adoption: weaknesses in research, outreach, IPM itself and farmers’ capacities; interference from pesticide industry and inadequate incentives for adoption. The relative importance of these clusters of obstacles varies from area to area, due to biophysical and socio-cultural differences. For developing countries, the main problem highlighted was that ‘IPM requires coordinated action within a farmer community’ (Parsa et al. Citation2014, 3889). To gain a better understanding of the effectiveness of IPM-FFS in farmer communities we did an in-depth study of the role of culture on the networking, interactive knowledge sharing, learning and alignment of farmers in two village communities with quite different uptakes of IPM.

2. Conceptualization of innovation process and culture

Agricultural Innovation aims to bring together networks of individuals, organizations and enterprises in order to bring new products, new processes and new forms of organization into (large scale) economic use (Hall et al. Citation2006). These processes involve networking, knowledge sharing, learning and aligning practices (Van Lente et al. Citation2003; Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2008, Citation2009). Evolution of such a process is highly complex and context-specific. The national policy context, biophysical conditions as well as the culture of farmer communities and other organizations involved influence the dynamics of the innovation process.

Culture is a collective, psychological phenomenon that through behavioural, emotional and cognitive elements influences how groups function and can jointly learn and solve problems. There are two quite different conceptualizations and epistemologies related to culture (Patel Citation2015; Citation2017; Lie and Witteveen Citation2013, Citation2019). Firstly, the socio-psychological mode takes a structural-functional and etic perspective on culture: reducing complex situations to known ones by identifying national or corporate ‘stable’ characterizations or typology of culture influencing individual learning and innovative behaviour. An example is the cultural framework consisting of Hofstede (Citation1991) distinguishing 6 dimensions of cultural orientations: individualism-collectivism; power distance; degree of masculinity-femininity; degree of uncertainty avoidance; time perspective and indulgence. Another prominent framework of Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (Citation1997) characterizes societies on the way how they solved 7 types of dilemmas. The second mode concerns the ethnographic and emic research perspective. This perspective looks at the complexity of culture as dynamic process of meaning-making. Cultural patterns emerge and change through the transaction or exchange of material and symbolic ‘items’ at individual and group level (Barth, Citation1956). It concerns an ongoing process with some actors more powerful than others, and some actors adhering more to the proposed cultural norms and values than others (Featherstone Citation1995; Patel Citation2017).

This research set out to understand the complexity of culture, influencing networking, meaning-making and innovation of practices in, pest management in two different farmer communities. Rather than employing a quantitative deductive research approach, it opted for a qualitative, inductive inquiry, applying ethnographic research methods. Having done the ethnographic research and rich descriptions of the cultural practices and meaning-making, however, we wanted to understand the underlying mechanisms. Perri Citation6 and Richards (Citation2017, 99) note,

to understand culture, we need to know the micro-foundations of human interaction and conflict management: the practices and ritual forms that explain their preferences and emotions. The specification of the underlying mechanism turns a typology into something capable of explanation.

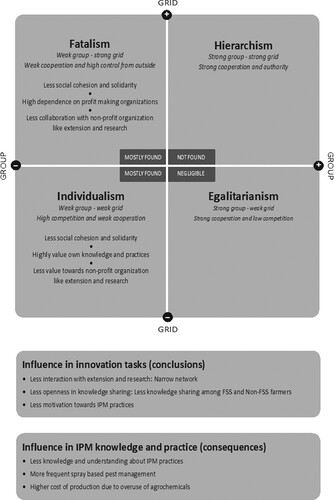

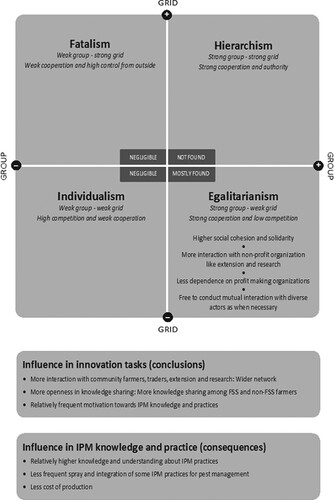

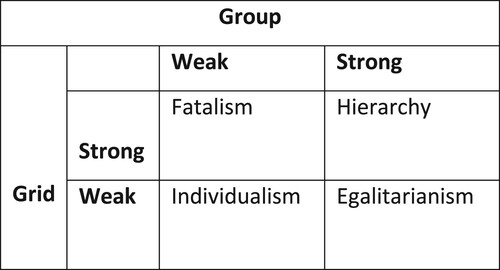

As highlighted above, Cultural Theory views culture as a preference or interpretation of meaning of a cultural constituted world (Craig and Douglas Citation2006). It distinguishes two critical preferences in social organization: ‘grid’ referring to the adherence to social regulation (so-called prescriptions), and ‘group’ referring to the adherence to social integration. Depending on the degree of grid and group adherence of its various members, a particular group of people can be positioned along the axes, and display a social-cultural organization typified as hierarchy, individualism, egalitarianism or fatalism.

In a hierarchal culture, people have a strong feeling of solidarity and tend to follow prescriptions or a strong grid, such as formal authority, as regards to rules for doing things with specialization and division of labour, etc. In contrast to this members of an egalitarian culture tend to follow fewer prescriptions and a weak grid and have a shared life of voluntary consent with strong feelings of solidarity. Members of an individualist culture show less solidarity and follow fewer prescriptions. In an individualist culture people prefer self-regulation as they highly value their personal autonomy, freedom, individual achievement and right to privacy. Finally, in a fatalistic culture, people tend to follow subscriptions from above but have little sense of solidarity (Patel and Rayner Citation2012).

Based on cultural theory, the research will answer the following two questions:

How do cultural differences between two farmer communities influence innovation processes: networking (relations with those within and outside the community), interactive knowledge sharing, learning and alignment for eggplant IPM?

What are the outcomes of the pest management oriented innovation processes (networking, knowledge sharing, learning and alignment for pest management and especially IPM) in the two communities?

3. Research setting and methodology

In Bangladesh, eggplant is grown on approximately 50, 000 hectares (10% vegetable area) by 150,000 smallholders (BBS Citation2018; Choudhary, Nasiruddin, and Gaur Citation2014). In Jamalpur, eggplant is an extensively grown (3167 ha [BBS Citation2018]) and an important vegetable crop (Kabir et al. Citation2010), particularly for the poor as they can harvest eggplant over a prolonged period, earning some regular cash for daily expenses. However, various pests and diseases lead to severe yield losses: the insect-pest fruit and shoot borer can cause losses of up to 70% in commercial settings (Choudhary, Nasiruddin, and Gaur Citation2014). Farmers often use pesticides indiscriminately and frequently at high concentrations (Raza et al. Citation2018), one reason why the Bangladeshi government has put so much effort into the development and implementation of the IPM-FFS approach.

At the outset of this research to better understand the influence of culture on pest management innovation, informal scoping discussions (Yin Citation2009) were done with government extension officers and researchers in Jamalpur to identify major eggplant growing villages with IPM-FFS. After several orienting field visits, Pirijpur West and Gopinathpur were selected as two major eggplant growing villages. Pirijpur West was known as IPM-FFS success story (Nov 2012- Feb 2013), while Gopinathpur would soon receive an IPM-FFS (April 2015).

In Purijpur, people cultivated eggplant in the winter, while those in Gopinathpur did so in the hot summer season, when pathogens and pests are more prevalent. This may have influenced the results and findings of our research somewhat as in situations of higher pest threats farmers might be eager to use IPM with a relative slower action mode, but it was not possible to find IPM-FFS communities with exactly similar crop conditions. Our research primarily focussed on the social dimension of FFS and IPM uptake.

In principle, we applied an inductive research approach, using ethnographic research methods. To get to know the villages and start relating to the farmers, the researcher used Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) techniques (Chambers Citation1994) such as transect walks, village map exercises and interactive group discussions to gather information about the demographics, the physical set up, cropping patterns, problems of eggplant cultivation, the frequency of agrochemical use, the nature of knowledge sharing and other pertinent factors. This scoping study was followed by participatory observations, numerous chats and open interviews, all aimed to attain an in-depth understanding of farmer communities’ innovation behaviour such as networking, knowledge sharing habits and alignment of cultivation practices. As IPM is labour-intensive, and efficacy depends on coordinated pest management in stretches of land under eggplant cultivation, farmers were purposely selected for the in-depth interviews, based on two criteria: (a) they had large or small area under eggplant cultivation; and (b) the farmer or spouse attended a IPM-FFS (so-called FFS farmer) or not (so-called non-FFS farmers). Farmers felt uncomfortable during being interviewed; hence we managed to get interviews with 6 FFS and 6 non-FFS farmers from Gopinathpur, and 8 FFS and 4 non-FFS farmers from Pirijpur but retrieved more interesting information through the more ethnographic research methods.

Ethnographic data were gathered through regular farm and home visits, informal talks and chats on the street, in local pesticide and grocery shops and relevant offices, informal group discussions; visits during emergent situations such as flooding, higher levels of insect and disease infestation and, whenever possible random participant observations of management practices (March 2015 to June 2017). In Gopinathpur, we attended the IPM-FFS sessions in 2015 and a ‘Field Day’, organized after the completion of the IPM-FFS to show and discuss IPM related issues among FFS and non-FFS farmers as well as with agricultural extension officers. As we had not been able to attend the IPM-FFS and field day in 2013 in Purijpur, we conducted more informal discussions in the community and organized two small Focus Group Discussions with 4 FFS and 4 non-FFS farmers respectively. In 2016, a community event was organized, where scientists from a research institute, agricultural extension officers, local pesticide trader, FFS and non-FFS eggplant farmers took part in an ‘open discussion’ on ‘the prospects and challenges in eggplant pest management’. These activities enabled the researcher to observe farmer-to-farmer interaction and knowledge sharing with outsiders.

The interviews, informal talks and discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed and coded. ‘Narrative analysis’ (Riessman Citation2008) was used to identify core issues in meaning-making related to networking, knowledge sharing, pest-management learning and action. As the cultural patterns of interaction and innovation are highly linked to a farmer community’s social organization, we added an analysis with Douglas Cultural framework. This provided additional explanations about farmers’ practices, relationships and capabilities related to pest management innovation.

4. Results

4.1. Introduction to study villages

Pirijpur (West) village was formed after river bank erosion and a subsequent change in the pathway of a branch of Brahamputra river. The majority of the farm families of this village migrated to the West side of the river to make use of the new land, and formed new households. They have relatively more land than in the other study village. Gopinathpur can be approached via an earthen road with a small sluice gate-bridge, controlling the water flow from Jhinai river that surrounds the village and an adjacent village. Before the liberation war of 1971, there were more than 100 Hindu families in Gopinathpur. Most of them were high educated and rich, owning dairy farms with large landholdings. They maintained good relations with the low-educated Muslim community members, who were employed as trusted servants or used farmland under sharecrop arrangements. During liberation war, the majority of the Hindu families migrated to India. Nowadays, 12–15 Hindu families still remain in Gopinathpur (while their high-educated family members live in the cities). Only a few large Hindu and Muslim farmers lease out or sharecropped their land to the low-educated, poor community of smallholders. gives some basic information about the two farmer communities.

Table 1. Major demographic and other information of two study villages.

Illiteracy, poverty, mistrust and misunderstanding seem to be common social features in Gopinathpur. Observations and informal talks revealed many inter-familial conflicts; with mutual avoidance, competition and/or evident jealousy. For examples at times of floods, households quarrel rather than to agree on proper management of the water and the sluice gate. There are five mosques around the village, and social tensions lead people to visit different mosques for their prayers. There were no reports of familial conflicts within Pirijpur: families did not demonstrate a strong disliking of each other in public. As there is no sluice gate in Pirijpur, flood-water management is not a community issue. The village has a cohesive ambiance, with the villagers organizing boat race competitions and everyone using the same mosque and contributing to its upkeep and the annual religious festival.

In both villages, eggplant is the most important vegetable crop, grown to cover household expenses. provides key data concerning eggplant cultivation. Farmers in Gopinathpur mostly cultivate summer eggplant: a long bushy variety for which each mature plant needs supporting with a bamboo cane. This involves extra expense and labour. In 2015 the villagers’ main challenge was controlling an outbreak of eggplant fruit and shoot borer (EFSB). In Pirijpur, farmers mainly cultivate winter eggplant, a dwarf variety that does not need a bamboo cane to support it when it is mature. In 2015, the crop was threatened by outbreaks of different diseases.

Table 2. Eggplant cultivation data of the two study villages.

This section describes cultural patterns in farmer community innovation behaviour related to pest management, notably: networking, knowledge sharing, learning and alignment of eggplant IPM practices.

4.2. Networking among farmer community members

The farmer networks in the two villages were quite different in terms of group solidarity, conflict management and collaborative action. In Gopinathpur, farmers repeatedly spoke of thefts of eggplants and damage to their fields caused by neighbours’ goats, which led to conflicts. One respondent told me: ‘This village is not good; there are conflicts with relatives and neighbours about tiny issues. After school (IPM-FFS) we do not speak to each other to settle these issues’. The field level extension officer, (the Sub-Assistant Agriculture Officer (SAAO) of Gopinathpur) underscored the low level of social cohesion: To protect their harvests, some farmers stayed overnight in their fields during harvest time. One elderly woman said that she stayed beside her eggplant field with a kerosene lamp and mosquito net. By contrast, in Pirijpur, where most eggplant fields are further away from household dwellings, farmers made no reference to thefts or the need for crop protection. One farmer mentioned that if any villager was in need of vegetables, they would receive them as a courtesy.

Though Gopinathpur is a small village and all the homesteads are located close to one another on the same side of the earthen road, only one non-FFS farmer was aware of the existence of the IPM-FFS within their village, showing that villagers did not share information with each other. IPM-FFS sessions were conducted in the open yard of one participating farmer. When the session was finished the FFS farmers were reluctant to start an IPM club. A few years ago they had run a cooperative which had fallen flat and the members had lost their savings and this led them to expect that the IPM club fund would be misappropriated. It took several informal gatherings before 10 (out of 25) group members finally agreed to start the club. They recruited a graduate student from a neighbouring village as executive member, to ensure close monitoring and fair practices. But ultimately there was no unity in running the club.

In Pirijpur, the farmers quickly organized themselves. One FFS farmer said, ‘After selecting the participants (for the IPM-FFS) we collected money from each member and constructed a new room which we used to conduct some classes’. After the IPM-FFS sessions, all 25 members joined the IPM club and the room is now equipped as IPM club office to conduct monthly meetings. According to the SAAO for Pirijpur, this well-organized IPM club captured the attention of the upazila’s agriculture office, which subsequently involved the group in several other collaborative programmes, in which non-FFS farmers were also free to join. Discussions revealed that majority of the farmers within the community know about the IPM club. In Gopinathpur, I found it difficult to mobilize farmers for a group discussion session. Farmers disagreed about who should be invited to participate and highlighted their disinterest: ‘people will not come, nobody will come just for empty words. It would be better to provide concrete benefits’. Eventually a few participants did turn up to the meeting. In Pirijpur less effort was needed to organize the session and everybody invited showed up or delegated another family member. Here there was a clear appreciation of group discussions, and the IPM club took the lead in organizing the ‘open discussion’ to which scientists and agricultural extension officers were invited.

4.3. Networking with outsiders

Illiteracy plays a major role in shaping Gopinathpur farmers’ interactions with insiders and outsiders. One farmer said: ‘We are illiterate. We repeatedly ask the traders which pesticide will work’. Another farmer said: ‘I am illiterate, cannot remember pesticide names. I do not understand what is inside the pesticides’. The majority of farmers here lack the confidence to visit the agricultural office with their questions or to have formal interactions with the officers. Most of the Gopinathpur farmers who participated in the FFS have a superficial knowledge and understanding about IPM practices. At the IPM-FFS ‘field day’, they did not arrange booths to explain IPM practices to the villagers who did not participate in the FFS.

In Pirijpur, illiteracy was no big challenge: most farmers seemed to feel at ease during formal and informal interactions with both insiders and outsiders. Farmers did not need a try-out for the programmed ‘open discussions’ event, and actively engaged in group discussions, presented and submitted written discussion summaries, and took part in question-answering sessions in front of extension officers and researchers. They demonstrated a better understanding of various IPM practices and showed more confidence and shared their real-life experiences.

In both communities, most farmers got their pest management information from nearby sources such as neighbouring farmers, friends, relatives, local traders or visiting pesticide promotion officers. In case of emergency, such as the appearance of a new insect or disease or a severe infestation, most of the farmers in Gopinathpur talked to traders and regular visiting pesticide promotion officers. Villagers had very few interactions with agricultural extension officers: only one-quarter of farmers I interviewed in Gopinathpur had interacted with the field extension officer and just one farmer had visited the Upazila Agricultural Office. It is telling that the year after the IPM-FFS, when the village experienced a severe EFSB infestation in that nobody called the SAAO to seek advice.

When similar emergencies arose in Pirijpur, most farmers communicated with local traders and those at market places because of their physical closeness and the value of face-to-face contact. But some farmers (both FFS and non-FFS) called the SAAO to seek advice before visiting pesticide traders. Whether by cellphone or face-to-face, nearly half of the Pirijpur FFS farmers and some non-FFS villagers had regular contact with SAAO and other extension officers. Moreover, nearly half of the farmers in Pirijpur whom I interviewed had visited the Upazila Agriculture Office and some of them had also visited the District Level Agriculture Office and Research Institute (to attend training courses). They had less connection with pesticide promotion officers as the latter visited their fields less frequently.

In Gopinathpur, an outsider (such as the extension officer) needed to engage in frequent informal, personal interactions for a long period, before farmers started to trust them and share relevant confidential information and seek advice. Good relations with some influential families were essential to organize an event in Gopinathpur, one reason that led the extension officer to conduct the IPM-FFS in the home yard of a respected family, and to invite three family members to attend the IPM-FFS. By contrast, in Pirijpur outsiders did not need to invest much time in trust-building before farmers start to share knowledge and experiences. The local SAAO said that the villagers readily offered two places for the IPM-FFS, and did not expect family favours in return.

4.4. Pest management knowledge sharing

Observations and discussions revealed that the majority of Gopinathpur farmers only trusted a few familiar people with whom they shared pest and disease management knowledge i.e. few relatives, friends, or a trusted trader from whom they get agrochemicals on credit. In Pirijpur, farmers readily trusted and share pest management knowledge and practices with a range of people: neighbouring farmers, known eggplant farmers, progressive FFS farmers, extension officers, local traders and visiting researchers.

4.4.1. Valuation of knowledge sharing amongst community members

Most Gopinathpur farmers did not share pest management knowledge with others nor did they visit the ‘sex pheromone trap’ demonstration plot of the IPM-FFS. Though they might have a cooperative relationship with a few other farmers, illiteracy, poor knowledge and understanding about pest management discouraged them from sharing their pesticide management experience. In informal conversations, Gopinathpur farmers demonstrated feelings of competition and jealousy towards each other, and did not want others to benefit from their knowledge. Some farmers mentioned that some farmers even tore off the name of pesticide from the bottle so that others could not see what they were using. One FFS farmer said- ‘Local farmers, myself included, will not give good suggestions to others.’

In Pirijpur, farmers tended to openly exchange knowledge and ideas amongst each other. Most farmers had visited the ‘sex pheromone trap’ demonstration plots of the IPM-FFS. During the ‘open community discussion’, farmers openly shared experiences of high and low pest infestations. Some farmers discovered that eggplant seedlings from the same source, cultivated with similar management practices performed differently due to the soil conditions. One farmer said that ‘another farmer had used “rotten mud” in the seed bed-which created the disease problem, but after some seasons this problem will disappear’. Another farmer added-‘I put the main field’s soil on the seed bed, so that the seedlings get accustomed with the nutrients and environment from the beginning to be better adapted in the main field’s soil’. A non-FFS farmer said that ‘the FFS farmers give us suggestions; they also invite us to their meetings. If we ask other non-FFS farmers about pest and disease control, they also answer in a good way, no hide and seek’.

4.4.2. Valuation of knowledge sharing with outsiders

Most of the Gopinathpur farmers valued their own knowledge of eggplant cultivation more than the knowledge provided by government extension officers, pesticide companies and traders. Though the farmers acknowledged frequently interacting with traders and pesticide promotion officers about pesticide names and doses, most of them mistrusted the latter’s business policy. They did not rely on SAAO’s pest management knowledge because he did not visit fields often enough to make a proper diagnosis and did not know the names of the latest and most effective pesticides. The SAAO confirmed that the Gopinathpur farmers hoped to get subsidized or free fertilizers, seeds or pesticides but were less interested in being provided information.

In Pirijpur, farmers valued their own and outsiders’ knowledge in eggplant pest management. They collaborated with outsiders’ programmes and spent more time and effort on knowledge sharing. Informal discussions confirmed that the SAAO of Pirijpur frequently visited the community to diagnose field problems and was known by the majority of the farmers. During interviews, the majority of the FFS and half of the non-FFS farmers acknowledged the SAAO and other extension officers’ contribution to eggplant pest management. Though Pirijpur farmers did hope to get material incentives, the SAAO confirmed that they were also highly interested in new knowledge and technologies.

4.5. IPM learning and practices

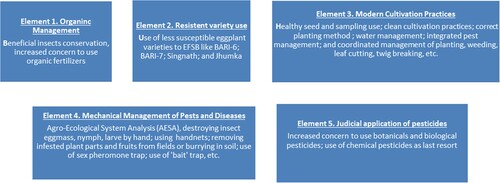

In the IPM-FFSs organized in both villages, a variety of knowledge and practices were discussed under the ‘Five Elements of IPM’ (). These elements help the farmers to understand that IPM is about the integrated management of pests, involves the application of a set of knowledge and practices, in which prudent application of pesticides is suggested as a last resort. The rest of this sub-section discusses the different levels of knowledge, understanding and application of IPM practices at the two farmer communities.

4.5.1. Differences in pest management knowledge and practices discussed in IPM-FFS

Though more than half Gopinathpur FFS farmers said that they applied clean cultivation practices, observations showed that the majority kept infested plant parts, such as EFSB infested twig, rotten leaves, fruits. They cut off the leaves of the infested summer eggplants, but left the leaves on the ground, providing a breeding ground for insects and increasing the risk of further infection. Few non-FFS farmers knew about or applied clean cultivation practices in Gopinathpur. Two farmers clearly stated that, when eggplant was a new vegetable in the village, the fields were kept clean but nowadays farmers were reluctant and did not have time to do so. Another farmer said: ‘I kept my field clean last year but as others did not it was not effective, so why should I continue?’ In Pirijpur, the majority of the FFS and non-FFS farmers knew about clean cultivation practices and most IPM farmers removed infected plant parts from their field to prevent further infestation. Field observations also showed that the fields of non-FFS farmers in Pirijpur were cleaner than in Gopinathpur.

Interviews revealed that half of the Gopinathpur FFS farmers (see ) soon forgot about beneficial insects after IPM-FFS, while non-FFS farmers did not know about beneficial insects at all. One FFS farmer’s husband said –‘Insects? Insects are enemies. Insects do only harm’. In Pirijpur nearly all FFS and some non-FFS Pirijpur farmers know about the existence of beneficial insects and some made efforts to keep them in their fields. One FFS farmer noted: ‘Spraying also kills beneficial insects. Beneficial insects eat harmful insects’ eggs and larvae. So, we should spray less to let the beneficial insects live’.

Table 3. Differences in major pest management knowledge and practice among FFS and Non-FFS respondents of both communities.

In Gopinathpur, less than half FFS farmers had a clear idea about the ‘sex pheromone trap’ which is locally known as ‘container’. Non-FFS farmers had heard about ‘container’ but did not know how it worked. Apart from the IPM-FFS demonstration plot, none of the Gopinathpur farmers used the sex pheromone trap. As the majority did not understand its workings, they were reluctant to try. One farmer said ‘Containers are not useful. If the container can control insects then why do people spray?’ In contrast, in Pirijpur, the majority of FFS farmers knew how the trap worked, and half of the interviewed FFS farmers were using traps at the time of the research. Half of the non-FFS Pirijpur farmers knew about the trap but did not use them as the agricultural office had not provided the promised free materials.

Most of the Gopinathpur farmers did not know the appearance of adult EFSB insect. Farmers usually saw small larva of EFSB in infested plant parts, which had no legs and wings. But the adult EFSB insects that fell in the trap had legs and wing resembling an insect that infests rice field. Even the owner of the demonstration plot said ‘Those containers are good for nothing, insects that fall into the container are not the eggplant’s insects, those are insects of the rice field’. By contrast, the majority of the Pirijpur FFS farmers knew the appearance of an adult EFSB. One farmer said- ‘The right insect (EFSB) falls into the container’.

In Gopinatpur, a few FFS and non-FFS farmers regularly hand-picked insect egg mass, larva, nymph, etc., although most opted for using a pesticide. In contrast, most Pirijpur FFS farmers destroyed egg mass, larva, nymph and insects by hand and uprooted severely disease-infested plants before considering spraying. One Pirijpur FFS farmer said- ‘There are jassids (insects) in my field but I will not spray so easily. If there are insects and eggs at the upper leaves I will rub ash on them to destroy them’. Some Pirijpur farmers followed their SAAO’s suggestion, and sprayed soapy water to control small insects such as leaf hoppers, white flies, jassid and aphid. Some Pirijpur farmers also cultivated coriander, sesame, etc. as a border crop that functions as an insect repellant and followed other seed and soil treatment practices recommended in the FFS and subsequent extension programmes. Gopinathpur farmers did not plant border crops with an insect repellent effect, and were not aware of the seed- and soil-treatment practices.

There was a major difference in the frequency of pesticide spraying between the two communities, with the spraying frequency and financial investment of most Gopinathpur farmers being higher than those of Pirijpur farmers. Gopinathpur farmers usually sprayed at 3–5 d intervals. In times of severe EFSB infestation during summer, most Gopinathpur farmers sprayed a range of pesticides on alternate days. In a group discussion meeting, one farmer said: ‘Pesticide use is increasing at such a rate that in the near future we might need to spray every day to control the insects’. Some pesticide promotion officers confirmed Gopinathpur farmers’ generally tended to overuse pesticides and had a higher frequency of spraying. In contrast, most Pirijpur farmers only sprayed once every 7–10 days. In case of severe infestation, they sprayed weekly or twice a week. Government extension officers confirmed the lower spray frequency among Pirijpur farmers. During a severe infestation, FFS and non-FFS farmers of both communities increased the spray frequency and tried different agrochemicals suggested by the traders.

The data above show that Pirijpur farmers were more aware of different eggplant pest and disease management options than Gopinathpur farmers. We found a higher level of awareness about IPM and utilization of its practices among Pirijpur FFS farmers than Gopinathpur FFS farmers and that more non-FFS farmers in Pirijpur knew about and applied IPM practices than non-FFS farmers in Gopinathpur.

5. Analysis of results and discussion

Empirical findings related to the networking, knowledge sharing, learning and alignment for coordinated pest management in the two farmer communities revealed quite distinct cultural patterns of social behaviour. When looking at these patterns some core elements seem to emerge. Extensive mistrust limited knowledge sharing and cooperation in Gopinathpur, while in Pirijpur there was trustful knowledge sharing, solidarity and collaboration. These patterns developed through performative reinforcement of meaning-making, practices and relations within the groups in their specific context (Perri Citation6 and Richards Citation2017). Our study was not geared towards an historical understanding of the cultural patterns, but in Gopinathpur the hierarchic relationships of the educated, rich Hindu families with the Muslim servants and sharecroppers; tensions experienced during the liberation war; the present general low level of education of farmers, and exposure to the highly competitive agricultural markets in area might have played a role. The situation and relationships seemed to have evolved more benevolent in the Muslim community of Purijpur, which benefitted from the additional land, created by the change of pathway of the Brahamputra river.

As highlighted in the theory section, rather than making an in-depth historical analysis, we want to understand the micro-mechanisms underneath the observed cultural meaning-making, relationships and practices in the farmer communities guiding pest management innovation, and therefore used the framework of Cultural Theory to assess farmers preferences in social organization and the influence this had on their networking, knowledge-sharing and IPM uptake.

5.1. Cultural characterization of Gopinathpur farmers

Most Gopinathpur farmers are positioned in the ‘weak group’ category of cultural theory, and show a cultural blend of ‘individualism’ and ‘fatalism’ in relation to eggplant pest management (see and ). Some farmers tended towards ‘weak group/ weak grid’ falling into the quadrant of ‘individualism’, characterized by competitive relationships with other community farmers, high valuation of personal freedom related to pest management and a strong reliance on own pesticide-oriented expertise. Some other farmers tended to ‘weak group/ strong grid’, falling in the ‘fatalism’ quadrant. Their social life was characterized by non-cooperative relationships within the community, while they were simultaneously dependent on pest management advice from others, as they lacked knowledge and confidence in own pest management practices.

Figure 2. Forms of social organization of human life in grid-group theory (adopted and simplified from Douglas Citation1978; Patel and Rayner Citation2012).

5.1.1. The influence of culture on networking, knowledge sharing and alignment

Results revealed that, adherence to ‘weak group’ rationality, characterized by mistrust, conflicts, jealousy non-cooperative and competitive attitudes, discouraged wider networking within Gopinathpur community for mutual sharing of pest management knowledge and practices, let alone collaboration for coordinated IPM measures. Most of the illiterate Gopinathpur farmers barely interacted with extension officers and researchers. They lacked confidence to interact with agricultural officers through formal office visits, cellphone calls, etc. and were unwilling to devote time to the SAAO to receive advice. Moreover, they did not trust the knowledge of government extension officers, and were only interested in possible subsidies. After the IPM-FFS, neither the farmers nor the SAAO met up with each other to run the IPM club. Similar findings have been found in another study in Bangladesh (Hamid and Shepherd Citation2005). In general, most Gopinathpur farmers interacted with a small number of people, having a so-called narrow network from which they sought to attain the necessary knowledge for eggplant pest and disease management.

The ‘weak group’ rationality of the Gopinathpur farmers limited knowledge sharing and learning about IPM. Farmers could not read pesticide names and prescriptions, did not understand the complex dynamics of IPM, and mainly learned through observation of each other’s pest and disease management practices and visible effects. Illiteracy contributed to ‘strong grid’ adherence, because these farmers needed affirmation from nearby experts before engaging in certain practices. Nearby traders and visiting pesticide promotion officers provided the necessary advice and pesticides, but rarely knew about or shared IPM knowledge and practices. Other case studies from Bangladesh confirm that farmers actively seek pest management advice and pesticide names from pesticide traders (Robinson, Das, and Chancellor Citation2007; Alam and Wolf Citation2016). The farmers hardly interacted with agricultural extension officers and so lacked necessary knowledge about IPM. Though some farmers learned one or two IPM practices at the IPM-FFS, most of them did not understand the complexity of IPM. The few farmers, who understood IPM practices, did not share this knowledge to their non-FFS neighbours due to weak relational ties. Though the summer eggplant with higher incidence of pests may also have discouraged farmers to try the slow-impact-IPM measures, the study showed the socio-cultural aspects illiteracy; little IPM knowledge; strong reliance on traders and pesticide promotion officers; weak relational ties and limited knowledge sharing highly constrained IPM learning and adoption of IPM.

5.2. Cultural characterization of Pirijpur (West) farmers

Most Pirijpur farmers were positioned in a ‘strong group’ category of cultural theory as they show cultural characteristics of ‘egalitarianism’. Most farmers showed ‘strong group/ weak grid’ behaviour as in ‘egalitarianism’ characterized by high mutual trust and cooperative relationships, and free interaction with a relatively high number of actors (neighbouring farmers, progressive FFS farmers, local traders, traders of nearby cities, extension officers, researchers, etc.).

5.2.1. The influence of culture on networking, knowledge sharing and alignment

The majority of the Pirijpur farmers displayed strong group solidarity, which stimulated pest management knowledge sharing with a wider network. When necessary, they freely interacted with an array of actors, as they did not have competitive or mistrusting feelings and relationships. Strong group solidarity and literacy skills enabled Pirijpur FFS farmers to organize an IPM club, which served as a bridge between the farmer community and outsider experts such as agricultural extension officers and researchers, inciting the latter to follow-up visits and programmes. Most of the literate Pirijpur FFS farmers interacted confidently with a relatively ‘wider network’ about eggplant pest management, which facilitated the innovation process (Hall et al. Citation2003). As there is a ‘stronger group’ feeling, the majority of the Pirijpur farmers easily exchanged knowledge and ideas with FFS- and non-FFS farmers, encouraging them to apply IPM. Pirijpur farmers exchanged knowledge with nearby traders, but as they could read the labels they critically selected certain pesticides. In this area where the winter eggplant experienced slightly less diseases, the open collaboration between farmers, extension officers and researchers facilitated innovation towards IPM ().

5.3. The effect of cultural differences on the outcome of the IPM innovation processes

Our study shows that due to cultural differences IPM innovation processes (networking, knowledge sharing and alignment) unfolded differently in the two communities and led to divergent outcomes. In Gopinathpur, the IPM-FFS did not lead to noticeable differences in the reported pest management practices of FFS and non-FFS farmers. Similar results were found in another case study in Bangladesh (Hamid and Shepherd Citation2005) where FFS and non-FFS farmers used the same amounts of insecticides and did not practice IPM. In Purijpur, however the IPM-FFS led to some changes in eggplant cultivation practices: farmers started soil and seed treatment, handpicking of insect egg mass, larva, nymphs, etc.; less frequent pesticide spraying; and displayed an increased concern for clean cultivation practices and coordinated pest management. The difference in pest incidence between the communities might have influenced the results, as in times of severe disease outbreaks, both villages tended to resort to agrochemicals as the dominant pest management strategy. However, the worldwide survey of Parsa et al. (Citation2014) showed IPM effectiveness accounted for about 18.4% of the adoption failure, while outreach and farmer characteristics accounted for 33.2% and 10.4%; hence it remains of crucial importance to understand these socio-cultural dynamics.

6. Conclusions

Scientists and policy makers increasingly advocate IPM as an agricultural practice, allowing good production with less detrimental environmental and health effects. However, in developing countries, IPM-FFS suffers from low adoption rates. As part of a larger research project on effectiveness of an eggplant IPM-FFS approach in Bangladesh, this article zoomed in on the influence of culture in farmer-level innovation. Inductive research showed differences in literacy coupled with divergent cultural patterns in networking, knowledge sharing, learning and alignment led to quite different IPM awareness and uptake. The observed cultural patterns were (partly) explained by the farmers’ preference for a certain form of social regulation and social integration. In the village with a low literacy, Gopinathpur, several farmers coupled their ‘weak group feeling’ with ‘high grid’ adherence. Because they could not read pesticide names and prescriptions, they needed reassurance and tended to strictly follow the prescriptions from someone, they considered knowledgeable about the actual pest and disease situation in their field. This was often a visiting pesticide officer or nearby trader rather than a government extension officers promoting IPM. In Purijpur, farmers displayed a ‘strong group feeling’ and ‘limited rigidness’, hence they were open to new knowledge and collaboratively tried out and adopted some IPM practices.

In this epoch, where scientists and practitioners increasingly engage in cross- and transdisciplinary research and innovation processes for sustainable agriculture and climate resilience, the importance of cultural studies is more and more recognized (Roncoli, Crane, and Orlove Citation2009). Technical and multi-level institutional research needs to be coupled with ethnographic knowledge. This study showed the relevance of cultural research to understand innovation processes at farmer community level, and the need for agricultural officers to take this into account in their extension approach. Furthermore, we demonstrated the value of Douglas cultural framework as cross-disciplinary tool for understanding cultural diversity and the effect it has on knowledge and innovation processes.

Acknowledgements

This research was part of the PhD Research project NICHE-BGD-156, executed by PhDs related to the Interdisciplinary Institute for Food Security (IIFS) of the Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU) in Mymensingh. We hereby would like to thank the Dutch Education organisation NUFFIC for funding the NICHE-BGD-156 project; and IIFS, BAU and all respondents for their kind support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, S. A., and H. Wolf. 2016. “Do Pesticide Sellers Make Farmers Sick? Health, Information, and Adoption of Technology in Bangladesh.” Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 41 (1): 62–80.

- Avelino, F., J. Grin, B. Pel, and S. Jhagroe. 2016. “The Politics of Sustainability Transitions.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 18 (5): 557–567.

- Avelino, F., and J. Rotmans. 2009. “Power in Transition; An Interdisciplinary Framework to Study Power in Relation to Structural Change.” European Journal of Social Theory 12 (4): 543–569.

- Barth,, F. 1956. “Ecologic Relationships of Ethnic Groups in Swat, North Pakistan.” American Anthropologist 58: 1079–1089.

- BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics). 2018. “Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics-2017.” Dhaka, Ministry of Planning.

- Chakraborty,, S., and A. C. Newton. 2011. “Climate Change, Plant Diseases and Food Security: An Overview.” Plant Pathology 60: 2–14.

- Chambers, R. 1994. “The Origins and Practice of Participatory Rural Appraisal.” World Development 22 (7): 953–969.

- Choudhary, B., K. M. Nasiruddin, and K. Gaur. 2014. The Status of Commercial Bt Brinjal in Bangladesh. ISAAA Brief 47. New Delhi: ISAAA South Asia Office.

- Craig, S., and S. Douglas. 2006. “Beyond National Culture: Implications of Cultural Dynamics for Consumer Research.” International Marketing Review 23: 322–342.

- Douglas, M. 1978. Cultural Bias. In Occasional paper 35. London: Royal Anthropological Institute.

- Featherstone, M. 1995. Uncoding Culture: Globalization, Postmodernism and Identity. London: Sage.

- Gallagher, K. D., P. A. C. Ooi, and P. E. Kenmore. 2009. “Impact of IPM Programs in Asia Agriculture.” Chapter 9 In Integrated Pest Management: Dissemination and Impact, edited by R. Peshin and A. K. Dhawan, 347–358. New York: Springer.

- Hall, A., W. Janssen, E. Pehu, and R. Rajalathi. 2006. Enhancing Agricultural Innovation: How to Go Beyond the Strengthening of Research Systems. Washinton, DC: World Bank.

- Hall, A., V. R. Sulaiman, N. Clark, and B. Yoganand. 2003. “From Measuring Impact to Learning Institutional Lessons: An Innovation Systems Perspective on Improving the Management of International Agricultural Research.” Agricultural Systems 78: 213–241.

- Hamid, A., and D. D. Shepherd. 2005. “Understanding Farmers’ Decision Making on Rice Pest Management: Implications for Integrated Pest Management (IPM) policy in Bangladesh.” 21st Annual Conference Proceedings, AIAEE, San Antonio, Texas, May 25–31.

- Hofstede, G. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: Mc-Graw-Hill.

- Kabir, M. H., M. S. Rahman, S. Khalil, A. R. Khan, and M. S. Rahman. 2010. “Assessment of Effectiveness of Pheromone Trap as IPM Practice for BSFB Management in Brinjal.” J. Agrofor. Environ 4 (1): 139–141.

- Kivimaa, P., W. Boon, S. Hyysalo, and L. Klerkx. 2019. “Towards a Typology of Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions: A Systemic Review and Research Agenda.” Research Policy 48: 1062–1075. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.006.

- Klerkx, L., and C. Leeuwis. 2008. “Matching Demand and Supply in the Agricultural Knowledge Infrastructure: Experiences with Innovation Intermediaries.” Food Policy 33 (3): 260–276.

- Klerkx, L., and C. Leeuwis. 2009. “Establishment and Embedding of Innovation Brokers at Different Innovation System Levels: Insights from the Dutch Agricultural Sector.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 76 (6): 849–860.

- Leeuwis, C., and N. Aarts. 2011. “Rethinking Communication in Innovation Processes: Creating Space for Change in Complex Systems.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 17 (1): 21–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2011.536344.

- Lie, R., and L. Witteveen. 2013. “Spaces of Intercultural Learning.” In International Perspectives on Journalism (Internationale Perspectieven op Journalistiek), edited by S. Mertens, 19–34. Gent: Academia Press.

- Lie, R., and L. Witteveen. 2019. “ICTS for Learning in the Field of Rural Communication.”.” In Handbook of Communication for Development and Social Change, edited by J. Servaes, 1–18. Singapore: Springer Nature. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7035-8_89-1.

- Oerke, E. C. 2006. “Crop Losses to Pests.” The Journal of Agricultural Science 144 (1): 31–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859605005708.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., D. Tabara, R. Bouwen, M. Craps, A. Dewulf, E. Mostert, D. Ridder, and T. Taillieu. 2008. “The Importance of Social Learning and Culture for Sustainable Water Management.” Ecological Economics 64: 284–495.

- Parsa, S., S. Morse, A. Bonifacio, T. C. B. Chancellor, B. Condori, V. Crespo-Pérez, L. A. Shaun, et al. 2014. “Obstacles to Integrated Pest Management Adoption in Developing Countries.” PNAS Early Edition, 111 (10): 3889–3894. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1312693111.

- Patel, T. 2015. “Crossing Disciplinary, Epistemological and Conceptual Boundaries in Search for Better Cultural Sense-Making Tools; A Review of Principal Cultural Approaches from Business and Anthropological Literatures.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 28 (5): 728–748. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-03-2015-0049.

- Patel, T. 2017. “Multiparadigmatic Studies of Culture: Needs, Challenges and Recommendations for Managements Studies.” European Management Review 14 (14): 83–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12089.

- Patel, T., and R. Rayner. 2012. “Towards a Transactional Approach to Culture: Illustrating the Application of Douglasian Cultural Framework in a Variety of Management Settings.” European Management Review 9: 121–138.

- Perri 6, P., and P. Richards. 2017. “Chapter 3. Building Fundamental Explanation.” In Understanding Social Thought and Conflict, edited by M. Douglas, 97–145. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Popp, J., K. Pető, and J. Nagy. 2013. “Pesticide Productivity and Food Security. A Review.” Agronomy for Sustainable Development 33: 243–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0105-x.

- Raza, S., A. Rahman, K. M. Rahaman, F. M. Julianan, S. Hossain, A. Rahaman, K. Hossain, J. Alama, and M. Asaduzzaman. 2018. “Present Status of Insecticide use for the Cultivation of Brinjal in Kushtia Region, Bangaldesh.” International Journal of Engineering Science Invention 7 (10): 44–51.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Robinson, E. J. Z., S. R. Das, and T. B. C. Chancellor. 2007. “Motivations Behind Farmers’ Pesticide Use in Bangladesh Rice Farming.” Agriculture and Human Values 24: 323–332.

- Roncoli, C., T. Crane, and B. Orlove. 2009. “Fielding Climate Change in Cultural Anthropology.” In Anthropology and Climate Change: From Encounters to Actions, edited by S. Crate and M. Nuttall, 87–115. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Schut, M., L. Klerkx, J. Kamanda, M. Sartas, and C. Leeuwis. 2019. “Innovation Platforms; Synopsis of Innovation Platforms in Agricultural Research and Development.” Encyclopedia of Food Security and Sustainability 3: 510–515. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22197-5.

- Smith, M. K. 2010. “David A. Kolb on Experiential Learning.” The Encyclopedia of Informal Education.” Retrieved 13 July 2018. http://infed.org/mobi/david-a-kolb-on-experiential-learning/.

- Thompson, M. 1996. Inherent Relationality: An Anti-Dualistic Approach to Institutions. Bergen: LOS Centre Publication.

- Trompenaars, F., and C. Hampden-Turner. 1997. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Van de Fliert, E., R. Dilts, and J. Pontius. 2002. “Farmer Researcher Teams, Farmer Field Schools and Community IPM; Different Platforms for Different Research and Learning Objectives.” In Wheelbarrows Full of Frogs; Social Learning in Rural Resource Management: International Research and Reflections, edited by C. Leeuwis and R. Pyburn, 121–133. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum.

- Van Lente, H., M. Hekkert, R. Smits, and B. Van Waveren. 2003. “Roles of Systemic Intermediaries in Transition Process.” International Journal of Innovation Management 7 (3): 1–33.

- Van Paassen, A., L. Klerkx, R. Adu-Acheampong, S. Adjei-Nsiah, B. Ouologuem, E. Zannou, P. Vissoh, L. Soumano, F. Dembele, and M. Traore. 2013. “Choice-making in Facilitation of Agricultural Innovation Platforms in Different Contexts; Experiences from Ghana, Benin, and Mali.” Knowledge Management for Development Journal 9 (3): 76–94. https://km4djournal.org/index.php/km4dj/article/view/156/257.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.