ABSTRACT

The aim of the article is to bring in the concept of governance and financial bureaucracies into the discussion on financing of innovation and development. The article refers to national development banks as the example of state-backed investors who make investment decisions in line with policy priorities (to prioritized sectors, technologies and development projects). While building on the examples of public development banks, the article seeks to conceptualize the governance of public strategic investments through the notion of a state-led ‘investment function’. In doing so, the article seeks complementarity of the concepts that derive from economics and innovation literature on one hand and public policy and governance literature on the other hand. This study suggests that the governance of state-led investments can be understood as a combination of financial policies, institutions and organizational routines that translate into capacities of respective public bureaucratic structures to make financing decisions.

1. Introduction

Following Schumpeterian innovation and development theory, technological innovation and finance are the two factors that define varying development trajectories, thereby making financial policies and financial governance integral components of effective economic and innovation policies (Burlamaqui and Kattel Citation2016a). Indeed, from the empirical-historical perspective, we have observed diverging development trajectories among nations rather than convergence towards similar levels of wealth and technological capabilities (Burlamaqui and Kattel Citation2016b; Dahi and Demir Citation2016; Gallagher and Porzecanski Citation2011; Radosevic Citation2001). Further, financing innovation involves investing in new sectors and economic activities, and hence is inherently uncertain – it adds to the financial instability that characterizes all financial systems (Burlamaqui and Kregel Citation2005; Kregel and Burlamaqui Citation2005).

In the context of modern global financialized industrial capitalism, developing countries are more prone to experiencing negative structural effects from financial shocks, and therefore a combination of macroeconomic and industrial policies defines their ability to withstand or respond to these shocks. That is, ‘the interaction between both policies is, therefore, critical for policy makers to prevent short-term shocks from turning into long-run losses of capabilities’ (Cimoli et al. Citation2020, 740). In other words, production – and innovation – capabilities are directly affected by macroeconomic and financing conditions. Hence, the process of development itself amplifies financial instability (Kregel and Burlamaqui Citation2005) and at the same time developing countries are more vulnerable to external financial shocks (Cimoli et al. Citation2020).

From a historical perspective, national governments have been handling more and more financial resources. Public spending has been steadily increasing during the past century – from less than 10% in the 1880s to some 30% in developing countries and some 50% of GDP and above in some developed countries in the 2010s.Footnote1 Yet nowhere and at no time have we witnessed public spending of such magnitude as today, with post-COVID recovery and green transition plans being put in place by national governments across the world: some $3 billion worldwide has been allocated to ‘building back better’ and making the economic growth necessarily more green, more inclusive and just, and more resilient. At the same time, an increasing number of countries are experiencing public debt distress (UNCTAD Citation2023).

All the above-mentioned factors raise the question of governments acting as strategic investors, and the various policy tools and coordination across policy domains (e.g. fiscal and monetary, fiscal and industrial, monetary and industrial/innovation) and policy levels (e.g. national and supranational or local/regional and federal) involved in directing financial capital towards productive use, including decarbonization (Mikheeva and Ryan-Collins Citation2022). Further, this also raises the question of the capabilities needed to effectively perform and evaluate state-led investments in innovation-led development and green growth.

An innovation systems approach emphasizes a systemic approach to learning and knowledge creation, interconnectedness of policy domains and therefore a ‘holistic’ policy approach to innovation-led growth and development. Fagerberg (Citation2017, Citation2022) identifies five basic processes in a national innovation system that influence (and are influenced by) the system’s technological dynamics or innovation (Fagerberg Citation2022, 230). These processes, also referred to as functions (Bergek et al. Citation2008) or activities (Edquist Citation2004), are the following: knowledge provision, supply of skills, demand for innovation, financing of innovation and shaping of institutions (laws and regulations) (Fagerberg Citation2022, 230).

In other words, a systemic approach to innovation recognizes the financing ‘function’ on a conceptual level, but in terms of analysis, innovation literature tends to take a narrower neo-Schumpeterian approach to finance. The focus remains either on venture capital types of financing (see, for example, The Handbook of the Economics of Innovation (2010) or The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation (2017); also Hanusch and Pyka Citation2006) or public spending on R&D and early-stage innovation only (see, for example, Borrás and Edquist Citation2019 or various contributions in the Elgar Encyclopedia on the Economics of Knowledge and Innovation (Citation2022)). In a similar fashion, literature on ‘modern industrial policy’ does not refer to the design of ‘modern financing policies’ conducive to investing in structural transformation (on ‘modern industrial policy’ see, for example, Felipe Citation2015).

This paper aims to make the case for a public sector’s ‘financing function’ or ‘state-led investment function’ that is similarly integral to innovation systems and economic development. By building on existing studies of ‘directionality’ of finance – whereby various types of financial capital result in different types of activities that are being financed (Mazzucato Citation2019; Mazzucato and Penna Citation2016; Mazzucato and Semieniuk Citation2017; also Marois Citation2021a) – this paper aims to make the case for incorporating a broader analysis of financial institutions, and their institutional functions and capabilities, into innovation literature in a more systematic way.

In order to do this, the study builds on the empirical examples of development banks – a specialized public financial institution operating at the intersection of innovation/industrial and financial policies. As financial institutions, development banks are also subject to financial regulation and supervisory oversight and, as they often borrow funds from foreign capital markets and multilateral lenders, they themselves are active financial actors on the global markets and are subject to global market dynamics and regulatory regimes. By supporting innovation and development projects in the non-financial sector, these specialized public institutions epitomize a state-led investment function whereby state-backed finance is directed to prioritized economic activities and hence productive capabilities. Therefore, state investment banks represent one of the modalities of how governments perform the ‘financing function’ in innovation systems, which has been discussed in literature on development (for example Griffith-Jones and Ocampo Citation2018) and political economy (for example Marois Citation2021a), but much less so in innovation studies.

The contribution of this study is therefore twofold. In conceptual terms, this paper suggests that governments perform a wider range of financing tasks than is typically analysed in the innovation literature. Namely, the strategic coordination of financial resources to serve the purpose of structural transformation along innovation and development priorities (be it decarbonization, industrial development and diversification or high-value export promotion). In empirical terms, this article takes the example of development or state investment banks which perform the function of state-led investors. This function is operationalized through internal capabilities, or routines, that can be analysed in conjunction with their institutional functions and policy roles. Both aspects are essential for a better understanding of how state-led investments are designed and implemented in line with industrial and innovation policy goals.

Methodologically, the paper relies on secondary empirical material published elsewhere to illustrate the ‘state-led investment function’. The conceptual framework builds on existing strains of literature, mostly from outside traditional innovation studies, in order to outline conceptual complementarities and the potential synergies of various strands of research. This then translates into a set of new research questions that can be placed within the field of the economics of innovation and the political economy of innovation.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents a literature review that brings together literature on financial institutions and governance on the one hand and public policy and policy capacities on the other hand. Section 3 elaborates on development banks by referring to various empirical cases discussed in the existing literature. Section 4 discusses the conceptualization of state-led investments and, subsequently, new research questions and section 5 concludes.

2. Financing of innovation and development

In the context of development, provision and deployment of financial capital has been one of the major policy concerns: active qualitative and quantitative credit controls, including external capital controls, were an integral element of industrialization-led development throughout most of the twentieth century and were particularly strong during the 1950s to 1970s, when the so-called ‘developmental state’ approach was taken by many national governments. These policies were based on the macroeconomic assumption that markets alone cannot generate full employment and government spending is essential for maintaining the required levels of aggregate demand (Keynes Citation1936). In political economy terms, coordination of industrial finance was often ‘central to the interaction between government and business’ and it was ‘a concrete mechanism of directing resources in support of innovation priorities’ (Calder Citation1993, xix). Such monumental economic, as much as political, tasks required capable financial administrations and it is therefore relevant to consider what constitutes governments’ abilities to pursue strategic state-led investments. However, there are few studies that analyse how governments perform and coordinate strategic investments and financing policies.

This section reviews the following strains of literature: Schumpeterian and (Post)Keynesian approaches to financial institutions in the context of development; the financial governance literature that discusses key public finance agencies – central banks, finance ministries, state investment banks – and the coordination of various financial policy domains; and the literature on public policy capacities and capabilities, which views public sector organizations as evolving, while continuously building internal capabilities that feed into policy design and implementation (as well as policy evaluation).

2.1. Investments, institutions and development

Burlamaqui and Kattel (Citation2016a) suggest that ‘economic development is not continuous and orderly, but rather an abrupt and conflict-prone process’ and therefore economic policies, particularly in the context of development, should aim at ‘flexible’ institutional configurations to allow for ‘continuous institutional reforms’ as national economic development trajectories unfold (Citation2016a, 1–2). After World War II, flexibility of financial credit policies was also discussed as one of the ‘lessons’ from state-led industrialization in newly independent countries, where flexible credit allocation policies were needed for the ‘balanced growth’ of emerging industries, alongside monetary stability and the diversification of financial structures (see, for example, YanFootnote2 Citation1982, 608). In the modern-day context, ‘flexibility’ and policy experimentation are extensively discussed in the case of China’s gradualist approach to market reforms and development (Weber Citation2021), as well as in the context of sustainability transitions (Kivimaa and Rogge Citation2022).

The Schumpeterian theory of economic development emphasizes the entrepreneur-banker nexus as the source of innovation (Schumpeter [Citation[1911]1961] Citation[1911]1961). Mazzucato and Wray (Citation2019) have suggested a Keynes-Minsky-Schumpeter framework, thereby emphasizing that financial systems can (and should) contain incentives for channelling financial capital into productive, development-oriented and innovation-inducing economic activities (also Burlamaqui Citation2015; Kregel and Burlamaqui Citation2005; King and Levine Citation1993). At the same time, in modern financialized industrial capitalism, governments tend to ‘de-risk’ private financial capital instead of pursuing more active financial policy interventions with the aim of enabling structural change (Gabor Citation2023).

The strategic role of state-led investments, particularly at a time of crisis, has been well conceptualized in (Post)Keynesian economics literature. The Keynesian theory of effective demand and the notion of ‘socialisation of investments’ suggested that public spending can (and should) influence the business cycle (Keynes Citation1936). Similarly, the theory of ‘functional finance’ suggested that public spending (including the issue of new money and debt) should aim to help generate full employment, lower inflation and mitigate fluctuations of the business cycle (Lerner Citation1943; also Nell and Forstater Citation2003). Minsky’s ‘financial fragility’ hypothesis implied that financial systems are inherently fragile and therefore there is a need for the ‘Big Government’ (and the ‘Big Bank’) that can ‘tame’ the fluctuations of financial cycles by building institutional buffers (Minsky Citation1986).

A Schumpeter-Minsky synthesis refers to the financing of innovation and development being inherently uncertain, which adds to financial instability: the development of new industries and investments in new economic activities imply economic uncertainties coupled with the creation of financial liabilities, which are held by various financial actors in the financial system, and not all these liabilities will be eventually repaid (Burlamaqui and Kregel Citation2005; Kregel and Burlamaqui Citation2005).

Following Dow (Citation2014) and her interpretation of Keynes (Citation1936), there are institutional configurations that influence financing actors (public and private) and their disposition to face such uncertainty: it is positive when there is confidence in future returns on investments and negative when such confidence is absent, either during economic downturn or when the technology or business model or market is not mature and hence the risks are too high. Therefore, financial governance of economic development and structural transformation(s) can be defined through policy-oriented institutions (policies, governance agencies and coordination within and between them), which form an essential part of ‘institutional configurations’ that influence the disposition of financing actors to face uncertainty of investments.

To conclude, the ability of public investments to influence the direction of development and innovation applies not only to the times of crisis, but is crucial to ensuring long-term prosperity and inclusive growth (Mazzucato Citation2013, Citation2018). This is because public investments tend to assume greater risks, and tend to diversify and invest in a wider range of technologies, which is essential for avoiding technological lock-ins (Mazzucato and Penna Citation2016; Mazzucato and Semieniuk Citation2017).

2.2. Public finance – a governance perspective

The Global Financial Crisis and COVID health crisis raised important questions about the roles of central banks in economic development and post-COVID economic recovery (UNCTAD Citation2020). Similarly, the roles of central banks and ministries of finance are discussed in the context of the green transition (Campiglio et al. Citation2018; Dikau and Volz Citation2018; also Mikheeva and Ryan-Collins Citation2022). Finance ministries are increasingly seen as the focal points of green financial governance in terms of leading on developing climate-related capabilities within national administrations (Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action Citation2023).

Existing studies of ‘catching up’ development trajectories refer to policy-oriented financial institutions, but they are often described as secondary to the industrial and economic planning governance. Indeed, studies of successful late industrializations, and particularly the so-called East Asian ‘developmental states’,Footnote3 put an emphasis on coordinated financing policies to support prioritized sectors that were key to the post-World War Two developmental strategies in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia and more recently China (Calder Citation1993; Development Bank of Japan and Japan Economic Research Institute Citation1999; Dikau and Volz Citation2021; Thurbon Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2016; Wade Citation2004). The coordination between key financial policy agencies such as central banks and treasuries/ministries of finance was crucial for channelling financial capital to industrial sectors, but also due to different time horizons: the immediate effects of fiscal and financial policies are different from industrial policies, which typically take longer to produce noticeable economic effects (Ali Citation1978).Footnote4

The notion of financial ‘state activism’ or ‘strategic techno-industrial governance’ is not confined to industrial credit allocation policies and the extensive capital controls of the 1950s to 1970s, but has recently been described in the case of Korea (Thurbon Citation2016; see also Lee Citation2019; Thurbon and Weiss Citation2019), Taiwan (Thurbon Citation2019), China (Burlamaqui Citation2020; Dikau and Volz Citation2021; Sanderson and Forsythe Citation2013) and the USA (Wade Citation2017; Weiss Citation2014). Further, the European Commission explicitly refers to financing policies as one of the key governing elements of innovation and development: concerted efforts to encourage and coordinate financial instruments and risk-taking in the EU funding ecosystem is key to directing innovation activities towards solving societal challenges (Mazzucato Citation2019). In the context of post-COVID recovery, the €800 billion Next Generation EU Fund is another example of a strategic approach to investment-led recovery and green growth, with coordination mechanisms linking national investments with economic and structural reforms (Mazzucato, Carreras, and Mikheeva Citation2023).Footnote5

The rapidly emerging literature on low-carbon transition and climate finance is also valuable in the following two respects: it takes on a systems-wide approach due to the systemic risks and radical uncertainty that climate change poses to financial systems (for example Kedward, Ryan-Collins, and Chenet Citation2020); and it emphasizes the abilities of key public financial agencies – particularly central banks – to influence the direction of financial flows in the economy (Barkawi and Zadek Citation2021; Campiglio Citation2016; Campiglio et al. Citation2018; Dikau and Ryan-Collins Citation2017; Dikau and Volz Citation2020). From the New Deal introduced by Roosevelt in the US to post-World War Two newly independent ‘developmental’ states, central banks had an explicit development-oriented mandate (UNCTAD Citation2020, Citation2013; Braun and Downey Citation2020; Bezemer et al. Citation2018; also De Carvalho Citation1995). In addition, literature on green transitions has been reinforcing the lessons that can be learned from the actual policy practice of industrial credit guidance policies that were instrumental to successful industrialization-led structural transformations (Mikheeva and Ryan-Collins Citation2022; Kedward, Gabor, and Ryan-Collins Citation2022) and, more recently, green refinancing schemes (Dikau and Volz Citation2018; Citation2021).

In addition, the increasing involvement of ministries of finance in environmental policies has been studied in the context of the European Emissions Trading System (ETS). This has highlighted the importance of these public agencies, as well as their different objectives (fiscal policy and macroeconomic policies) in shaping the ETS, which links environmental and fiscal policies (Skovgaard Citation2017a), as well as the overall ability to shape the conversation on climate finance either as a fiscal cost or as a policy response (Skovgaard Citation2017b).Footnote6 The recently founded global Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action recognizes that finance ministries have a distinctive role to play in leading on the climate agenda within their respective governments, while playing three key functions: setting economic strategy and vision, conducting fiscal policy and implementing financing function (reforming financial system to channel finance towards green transition) (The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action Citation2023, 45).

From a broader perspective, the economic and policy problems addressed in the rapidly developing research on climate finance speak to similar research questions on the financing of industrialization. Namely, green structural transformation implies directing capital to low-carbon innovation while simultaneously limiting investments in dirty sectors – this parallels the challenge of supporting productive sectors while limiting financing of speculation-prone sectors (e.g. consumption and real estate) in the course of rapid industrialization during the post-World War II period. Therefore, coordination of financial and macroeconomic policies on the one hand and industrial, green and innovation policies on the other hand is challenging and can involve conflicting policy objectives, such as expansionary investments versus financial and macroeconomic stability (Mikheeva and Ryan-Collins Citation2022).

To conclude, the financial governance perspective enables us to consider the broader institutional context in which (national) financial capital operates. The governance perspective also emphasizes the crucial role of coordination between financial policies and non-financial, such as industrial, innovation, trade and climate policies. In other words, literature on financial governance is helpful in defining state-led investments in innovation and development through coordination and complementarities (as well as contestation) between financial policies, as well as between key public agencies – public bureaucracies.

2.3. Public sector capacities and capabilities

Policy capacities and public bureaucracies that are integral to the process of policy making are typically discussed in the literature on public governance and public policy. In more general terms, Painter and Pierre (Citation2005), Peters (Citation2015) and Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) analyse the capacities of governments to design, implement and coordinate public policies. Literature on policy capacities discusses analytical, including transposing scientific evidence into policy making (Howlett Citation2015), regulatory and relational capacities (Jayasuriya Citation2004, Citation2005).

Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett (Citation2015) differentiate between operational, analytical, and political capacities that exist at individual, organizational and systemic levels. This framework substantially adds to our understanding of the competences and capabilities involved in policymaking. The framework also suggests that effective policymaking would imply the existence of a set of skills and resources – or competences and capabilities – necessary to perform policy functions (Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett Citation2015, 166). Mukherjee and Bali (Citation2019) develop this argument further by suggesting that effective policy solutions are possible when analytical, managerial and political capabilities of policymakers co-exist.

More recent studies emphasize that understanding ‘post-growth’ policies requires a more nuanced analysis of public sector capabilities (Borras and Edler Citation2020). Further, ‘innovation does need capable public bureaucracies’ as modern public organizations are ‘consciously aiming to support innovation and technological advancements’ (Kattel, Drechsler and Karo Citation2022, 64; also Kattel and Takala Citation2021). While building on the conceptual premises of evolutionary economics (policy making is a continuous process whereby institutional and organizational structures evolve – Nelson and Winter Citation1982) and by drawing parallels with the literature on dynamic capabilities in private firms (for example Teece Citation2016, Citation2022), these studies suggest that public sector organizations are not static and their internal capabilities evolve, thereby being integral to the process of policy making (Kattel, Drechsler and Karo Citation2022; Kattel Citation2023). Further, organizational capabilities exist in the form of organizational routines that exist and change over time – they represent ‘patterned organisational behaviour of learning and change’ (Kattel Citation2023, 6).

If there is a ‘financing function’ or ‘state-led investment function’ that governments perform, then it is relevant to ask what capacities and capabilities are needed for public financial institutions to design and implement financial policies that enable innovation and development. Existing literature discusses policy capacities related to specific financial policy domains. For example, regulatory capacities are discussed (Levine Citation2012; Lütz Citation2004; Quaglia Citation2014), particularly in the context of responding to financial crisis conditions (Woo et al. Citation2016) or to pursue nationalist financial policies, such as ‘banking nationalism’ (Mérő and Piroska Citation2016). Capacities of central banks are analysed with regard to the ‘profit-oriented planning’ within the private financial system (Braun Citation2021) or climate finance (Dikau and Ryan-Collins Citation2017; Dikau and Volz Citation2018) as well as development-oriented policy mandates (Barkawi and Zadek Citation2021; Braun and Downey Citation2020). Regulatory capacities are discussed in relation to financial innovations and the necessary collaboration between central banks and private financial actors (Mikheeva and Tõnurist Citation2019). It is important to differentiate between the varying capacities of these actors (public and private) to engage in collaborative practices (Mikheeva and Tõnurist Citation2019) or what constitutes ‘relational’ capacities (Jayasuriya Citation2005).

There is considerably less literature on state-led investments as, contrary to the financial regulation function jointly carried out by finance ministries and central banks, public investments represent a greater variety of policy tools implemented by a greater number of public agencies (from public procurement and subsidies to investments by state-owned companies and fiscal policies). Literature on state investment banks partially fills that gap: there are studies of public investment banks that are capable of effectively channelling financial capital to policy-relevant sectors (Griffith-Jones and Ocampo Citation2018; Macfarlane and Mazzucato Citation2018; Mikheeva Citation2019). There are also recent studies of a wide range of institutional functions performed by public banking institutions (Marois Citation2021a).

To conclude, literature on policy capacities and public bureaucracies suggests that public policies can be studied from an additional, organizational perspective. This is because public sector bureaucracies are not static organizations, but evolve and develop policy-related capabilities that can either help or hinder the process of policy making. Further, organizational routine is introduced as an analytical category (Kattel Citation2023) and this represents a more ‘granular’ approach to studying public sector organizations. Routine-based approach can help in shedding more light on financial policies in particular, as they are often characterized by closed policy communities (e.g. Mikheeva and Tõnurist Citation2019; Tsingou Citation2015) and expert-driven capabilities (e.g. Seabrooke and Tsingou Citation2014). To empirically illustrate this approach, the next section discusses national development banks as the example of a public agency performing a state-led investment function.

3. Development banks: strategic state-led investors

The literature discussing policy roles and comparative studies of state investment banks has been expanding, particularly since the Global Financial Crisis. The revival of academic and policy interest in development banks during the past decade poses many questions as to how governments can be utilizing these institutions as strategic financing tools in industrial and innovation policies and, more recently, low-carbon transition policies (for example German KfWFootnote7 has played an important role in the national energy efficiency programme Energiewende). Sometimes this is also coupled with the need to take public investments off public finance balance sheets as often the activities of state investment banks do not count as public expendituresFootnote8 while, de facto, complementing ‘official’ public investment expenditures (Guter-Sandu and Murau Citation2022). Public banking institutions are additionally seen as policy-oriented institutions that can actively help implement the green transition and decarbonization by acting in the public interest and counterbalancing profit-oriented private banking (Marois Citation2021b; also Mazzucato and Penna Citation2016).

3.1. Institutional context

State investment banks never function in isolation, but closely coordinate with other key public financial agencies, particularly ministries of finance and, less often, central banks. Following the latest Global Survey of Development Banks (WB Citation2018), more than two-thirds of 64 surveyed institutions worldwide are operating under ministries of finance and some of them are simultaneously subject to financial regulation by their respective central banks or financial supervisory authorities. Central banks are increasingly establishing refinancing credit lines to priority sectors, including green sectors, and China’s central bank has been using this as an instrument of industrial policy (Dikau and Volz Citation2021) in close coordination with the China Development Bank.

Studies of industrial credit provision in some of newly industrialized economies such as Taiwan and Malaysia refer to similar types of coordination: central banks or ministries of finance have established dedicated funds (often in the form of soft-loan schemes) to support prioritized economic sectors while financing was administered by development banks (Mikheeva Citation2018; Thurbon Citation2001). In addition, governments (ministries of finance, central banks or dedicated guarantee agencies) often provide guarantees that can serve various functions: from helping to cover currency exchange risks (particularly relevant for the imports of capital goods and technology) to de-risking private investments in prioritized and new industries or serving as a risk-sharing mechanism in large infrastructure projects comprised of multiple types of investors.Footnote9

Development banks often report to ministries of finance on financial indicators, while non-financial indicators are increasingly gaining importance. The global survey of development banks (WB Citation2018) indicated that most of the surveyed banks were not equipped with adequate techniques to measure and monitor the development-related effects. Such non-financial indicators are typically reported to the ministry of economy or industry, but measuring developmental impact beyond direct measures such as generated employment and produced output is complex, because it takes a long time to materialize and can involve different ‘relational’ capacities. For example, capturing productivity effects generated by an industrial loan involves closer monitoring and detailed examination of industrial borrowers by the bank throughout and after the lifetime of the financed project (Mikheeva Citation2018).

The various types of policy and operational linkages development banks have with other public agencies and ministries imply that the political economy of this coordination can involve conflicting objectives. Calder (Citation1993), while analysing industrial credit policies in post-World War II Japan, refers to the general notion of higher risk-taking and a willingness to venture into new economic sectors promoted by economic planning bureaucrats at the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, which was at times in conflict with the more cautious attitude of financial policy bureaucrats in the Ministry of Finance, who emphasized financial stability and prudence. In a somewhat similar vein, when development banks are supervised by financial regulatory authorities but are owned and operate under one of the ministries (typically the ministry of finance), this may create potential problems with timely corrective action, as the ministry does not always have strong risk assessment capacities when compared to a central bank or financial regulatory authority (WB Citation2018, 38). At the same time, making development banks subject to the banking regulations governing commercial finance poses the risk of these policy-oriented institutions becoming too risk-averse, with no incentives to venture into new investment areas (see the most recent analysis of tailoring regulatory oversight to development banks’ objectives by Gottschalk, Xu, and Barros Citation2020; also KfW Citation2016).

Today, the development banking sector is essentially global and many development banks have established separate international or foreign investment subsidiaries (for example Germany’s KfW, Korea’s KDB, China’s CDB). Foreign arms of development banks can become important players in shaping industrial policy objectives and the financing landscape abroad – foreign lending by Germany’s KfW and China’s Development Bank are such examples, not without criticism, particularly in terms of affecting the development trajectories in developing countries (for example Naqvi, Henow and Chang Citation2018). At the same time, development banks follow internationalization strategies by entering international financial markets whereby competitive project finance is structured through syndicated finance – joint financing provided by a group of development banks, either for mega infrastructure projects or for truly global industries, such as ship building or logistics and freight (see the case study of the Development Bank of Singapore and its internationalization strategy in Geok, Gleave, and Buche Citation2006). On the other hand, the internationalization of large domestic non-financial firms creates additional demand for establishing subsidiaries in the key export markets of domestic firms (see the case study of the Korea Development Bank in Mikheeva Citation2019). Further, by channelling funds from foreign financial institutions and capital markets to domestic firms, banks and public institutions, development banks often act as the bridges between domestic needs for capital investments and global financial markets. One example is Mexico’s Nacional Financiera, which was tasked with approving all foreign borrowing by public agencies during the decades of successful industrialization (Blair Citation1964, 221).

Private financing actors are usually seen as the sine qua non of development and innovation financing. In policy practice it takes the form of promoting public-private partnerships, co-investment programmes and de-risking private capital. Without denying the importance of market mechanisms, this has often resulted in the use of ever-increasing leveraging and financial engineering techniques, and a reliance on financial intermediaries, rather than market intelligence and technical competences about new sectors of the ‘real’ economy (Griffith-Jones and Naqvi Citation2020). In other words, development banks are subject to globalization and financialization trends, and there is a need to better understand how development-oriented projects are structured for financing using increasingly opaque pricing and risk-sharing mechanisms and algorithms (Griffith-Jones and Naqvi Citation2020; Kavvadia Citation2020).

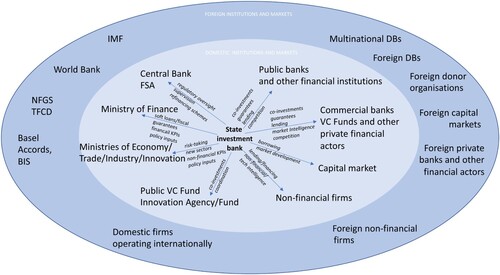

is a stylized depiction of various types of activities pursued by development banks jointly with other policy and market actors, while differentiating between domestic and foreign institutional contexts. The types and complexities of these relations represent dynamic institutional configurations from which we may discern patterns of inter-agency coordination. For example, hierarchical coordination takes place between development banks and financial supervisory authorities, as well as through reporting on financial performance indicators. Co-investments with commercial banks do not exclude competition for borrowers and markets, although in conceptual terms ‘complementarity’ and ‘additionality’ of state-led investments is necessary and is often emphasized in formal mandates (see, for example, Griffith-Jones and Naqvi (Citation2020) discussing the additionality of the European Investment Bank (EIB) lending). However, as discussed above, financialization and the increasing involvement of private actors in development financing results in the duality of these roles.

3.2. Policy and institutional functions

A wide range of empirical cases discussed in the existing literature suggests various typologies in the policy roles that development banks perform. For example, Mazzucato and Penna (Citation2016) differentiate between countercyclical, capital development, venture capitalist and mission-oriented or challenge-led policy roles. Griffith-Jones and Ocampo (Citation2018) differentiate between the five development-oriented roles played by development banks: counteracting a procyclical behaviour of private finance; promotion of innovation and structural transformation; facilitating financial inclusion; providing large-scale infrastructure investments; and promoting sustainable and green growth (Citation2018). Geddes, Schmidt, and Steffen (Citation2018) differentiate between capital provision, de-risking, educational, signalling and first/early mover roles when considering the financing of green energy by state investment banks. Ferraz and Coutinho (Citation2019) suggest differentiating between pro-cyclical, counter-cyclical and pre-cycle investment-related roles that development banks play, depending on the timing of their investments vis-à-vis a business cycle.

Mikheeva (Citation2019) suggests that development banks can perform investment, transition and managerial functions where the investment type is associated with a greater financial discretion in making investment decisions, while managerial type refers to a stronger focus on the financial management of largely pre-defined soft-loan schemes that are designed and funded out of ‘earmarked funds’ by either a ministry of finance or industry or, in some cases, central bank. State investment banks also play the role of developing financial and capital markets: Kregel (Citation2009) points to the crucial domestic ‘capital development’ role played by Brazilian BNDESFootnote10 as it largely supplants the domestic private capital market, while Mertens and Thiemann (Citation2018) discuss how European development banks act as quasi-fiscal institutions and play a role in shaping financial markets in the EU.

Marois (Citation2021a) extends the debate towards public banks at large and the need for a ‘dynamic’ view on publicly owned banking institutions – that is, their institutional functions change over time depending on the political economy and contested interests of social actors (Marois Citation2021b). Within this everchanging context, public banks can play the following functions: household and/or commercial retail and commercial services; development finance and investment services; concessional lending and service provisioning; venture capital and equity financing; mandate-driven and emergency lending; public sector collaborations and support services; micro- and SMEs support; knowledge services; financial integration and access; aid and development (Marois Citation2021b, 98–100).

Most of the existing research attempts to group the activities of development banks according to the institutional functions they play in different national economic, political and public governance contexts. At the same time, it is also relevant to ask how these functions are performed. That is, in terms of academic research as well as policy practice (and evaluation), one of the main challenges is to understand whether and how a state investment bank carries out its institutional functions – in our case, in the context of financing innovation and development. One way of doing this is by analysing a bank’s internal capabilities and organizational routines – a dynamic process of organizational learning (Becker et al. Citation2005; Kattel Citation2023).

3.3. Dynamic capabilities and routines

Development banks are often described in existing literature as ‘constantly reinventing themselves’ and changing policy priorities – this is necessary for them to retain policy relevance in the long run (e.g. Griffith-Jones and Ocampo Citation2018). This also means that the institutional context in which they operate (coordinate) and their internal capabilities need to be ‘reinvented’. For example, development banks often provide policy inputs in terms of sectoral reports, technology evaluations, forecasts and market intelligence to the ministry of economy/industry. Such expertise is crucial at the start of industrialization,Footnote11 but it is no less important in the context of financing innovation and technology-intensive firms.Footnote12

Analytical, technical capabilities are typically located in the technical appraisal department or financial advisory department (Mazzucato and Mikheeva Citation2020).Footnote13 In addition, development banks often nurture networked relations with research institutions, industrial associations – for example, Germany’s KfW maintains long-standing relations with various Fraunhofer Institutes that specialize in applied research and the EIB has working relations with the range of European industry associations.

In the context of foreign institutions and markets, there are similarly different types of interactions and activities development banks perform. Internationally, they may compete for foreign investment opportunities while simultaneously providing financial avenues for the internationalization strategies of domestic firms – this requires global market intelligence and technology forecasting analytical tools. Raising funds from foreign capital markets, borrowing from international lenders while participating in syndicated financing in international mega-projects or competitive industries, involves another set of internal capabilities. At the same time, development banks are subject to the regulatory standards and knowledge regimes created by international multilateral organizations, such as the IMF, World Bank and Basel Committee, as well as the newly created NFGS and TFCD. The rapidly emerging climate-related reporting, disclosure and investment standards also affect development banks, so they need to develop new sets of climate-related capabilities, not only in terms of financial reporting and global climate finance, but also in terms of technical knowledge of low-carbon technologies and sectors.

Therefore, identifying and analysing organizational routines – understood as the basic components of organizational behaviour and repository of organizational capabilities (Becker et al. Citation2005) – can be considered as essential for state investment banks to ‘reinvent’ themselves in line with changing policy priorities or new economic activities that need to be supported. This translates into intentional development of new organizational capabilities – analytical and technical, relational and coordinative, financial and administrative – to carry out new policy-related tasks, such as financing new forms of renewable energy, supporting decarbonization projects or radical innovation in food processing and materials industries, to name just a few.

In other words, financial institutions learn – accumulate tacit knowledge – through the actual process of financing new economic activities, thereby acquiring unique technical and financing capabilities vis-à-vis the productive economy and technologies. It is of outmost interest to trace the evolution of such learning within state investment banks. Situating the organizational forms of such learning can be telling in terms of understanding actual investment strategies, risk appetite, conditionalities of investments and the potential development-related effects of financing decisions. For example, understanding how the front office – or sales team – solicit technical advice for project appraisal (whether is there an internal technical appraisal team or external experts) can be helpful in analysing criteria for investment decisions, whether these decisions are risk-averse or the range of projects is diverse enough. Similarly, whether there are coordination-related capabilities that define the ability of the bank to coordinate activities – particularly with the finance ministry and ministry of economy/industry – in order to feed into economic and industrial strategies. In broader terms, it is relevant to analyse whether and how organizational routines reflect the ‘form and function’ of the public financial institution to carry out its policy-related financing mission (e.g. see Ferraz and Coutinho (Citation2019) for the discussion of the BNDES’ pro-investment mission).

4. State-led investment function and new research questions

To reiterate, various public agencies could have various degrees of importance in designing policies that aim to stimulate innovation and development financing. Understanding financial bureaucracies (i.e. key public organizations) can help us analyse not only policies, but also a set of capabilities that affect these policies and, ultimately, ‘institutional configurations’, echoing Burlamaqui and Kattel (Citation2016a,Citationb), that can be either conducive to or hinder effective innovation and development financing.

‘Functions’ and ‘activities’ have often been used interchangeably in the literature on systems innovation in order to show what ‘happens’ in the systems rather than focusing on their ‘components’, such as organizations and institutions (Borrás and Edquist Citation2019, 23). The analysis of systems of innovation through a functionalist lens allows for a more dynamic approach to ‘what happens’ in the system (i.e. what are the various activities in the system that cause innovation to occur) and for identifying the determinants of innovation rather than consequences (Hekkert et al. Citation2007; Bergek et al. Citation2008, Citation2010). With the example of functional public procurement, Borras and Edquist (Citation2019, 31) suggest that a functionalist approach keeps the focus on problems that need to be solved: the public agency would specify what needs to be achieved rather than how it needs to be achieved, using functional specifications rather than product specifications.

This article suggests taking one step back and considering the internal capabilities of the public agency that define how the above-mentioned agency specifies ‘what is it to be achieved’. This way research questions move closer to the policy practice and, ideally, feedback to the research agenda. Following this functionalist approach, while adding insights on public sector capabilities as discussed above, we may suggest that governments perform strategic ‘financing’ or an ‘investment’ function in the innovation system that results in financing and innovation-related activities in both, public and private sector organizations. Put differently, a ‘state-led investment function’ can be analysed through strategic public policies and related public bureaucracies, in terms of their internal capabilities to design and carry out these policies. Therefore, incorporating research on public sector organizations into innovation systems studies can help build a more nuanced understanding of how governments participate and shape the financial capital that is available within a given innovation system.

In terms of a comparative approach that allows studying different institutional configurations (for example financial systems or innovation systems), the concept of functionality can be equally helpful. It has been also applied in literature on public governance as an analytical construct in order to identify the critical roles and functions that governments, together with other social actors, perform in the society (Peters and Pierre Citation2016). In empirical terms and in view of policy practice, functional governance has been emphasized as the one spanning across various administrative jurisdictions or policy domains or geographic boundaries: see, for example, ESPON (Citation2018) studies of regional planning; and Varone et al. (Citation2013) discussing functional regulatory spaces in the context of wicked problems. In addition, various authors suggested the notion of functionality in innovation systems and the typology of functions that lead to innovation processes in systems (Bergek et al. Citation2008, Citation2010; Hekkert et al. Citation2007; also Borrás and Edquist Citation2019). In this regard, identifying institutions, policies, organizations and activities that constitute a ‘state-investment function’ can be helpful when analysing financial governance across different political and economic systems without being prescriptive.

This is because the governance perspective does not imply a causal analysis, nor does it imply a certain extent of normativity. Instead, it offers an ‘organising framework in identifying ‘objects worth of study’ (Stoker Citation1998, 18). Functionality of governance also implies a comparative element, that is, analysing how the same critical role(s) is performed through various functions in various governments. In other words, the functionalist approach to governance ‘defines core functions of governing generically, i.e. it makes no prejudgments about the degree to which government institutions fulfil those functions or, for that matter, whether governance is democratic’ (Peters and Pierre Citation2016, 6). Therefore, it is possible to compare how various functions – for example, state-led investments in innovation – are carried out between various governments and political systems (in space) or between various periods of time.

Finally, analysing public bureaucracies in terms of organizational routines and tacit knowledge imply political economy considerations: various public agencies (and ministries) would have a different view on development-oriented public investments and related financing policy tools. The research on conflicting policy objectives is very limited and is only mentioned in relation to the success stories of late industrialization, as noted above. However, intra-bureaucratic conflicts over policy tools are not only political, but can also be technical (or technocratic) in nature: a ministry of economy or innovation agency might have a different view on development-related investments from that of the finance ministry. Moreover, in the era of financialized industrial capitalism, finance has become a contested field (Marois Citation2021a) and the insights from political economy can be equally helpful when incorporated into the innovation systems research agenda.

5. Conclusions

This article aims to widen the notion of finance in innovation literature and to partly overcome the fragmentation of research streams where monetary, fiscal, budgetary and regulatory policies on the one hand, and innovation-oriented financing on the other hand, are treated somewhat interdependently but studied separately. This is also apparent in the emerging literature on financial governance of the green transition (Newell et al. Citation2023) or climate-related finance (Kedward, Ryan-Collins, and Chenet Citation2020).

The article has also suggested that the notion of ‘functional governance’ helps problematize the role, functions and actors involved in carrying out state-led investments in innovation and development without limiting the analysis to measuring impact or coordination between policies or institutions alone. Indeed, more coherent coordination between various policy tools, and between financing and industrial and innovation policies, is becoming a sine qua non of innovation and development. However, the question of how governments would enable or perform the often ambitious, state-led investment function is rarely brought to the front. Often, the capacities of governments to design and implement policies are considered as an exogeneous variable or simply as ‘given’. While integrating research streams on public governance and capabilities, innovation studies and finance, this article has attempted to overcome this limitation by looking at public policies in conjunction with financial bureaucracies and by outlining three broader research themes that can be incorporated into the field of innovation studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Government expenditure in modern history: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/FRA/JPN/GBR/SWE/ESP/ITA/ZAF/IND.

2 The then deputy governor of Bank Negara, Malaysia’s Central Bank.

3 See Johnson (Citation1999) on the history of the term.

4 The then governor of Bank Negara, Malaysia’s Central Bank; in office 1962–1980.

5 However, the ‘distinctly European’ macroeconomic framework limiting state aid and the reluctance of the EU to reform fiscal rules around public debt ceilings result in de-risking private investments rather than ‘disciplining’ it around (green) industrial policy goals (Gabor Citation2023).

6 Other studies of financial bureaucracies have similarly identified the various ‘roles’ of ministries of finance in fiscal policies: either of ‘guardians of the purse’ with a stronger emphasis on balanced national budgets or with a more ‘developmental’ view and focus on structural budgets and countercyclical public spending (Raudla et al. Citation2018).

7 Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau.

8 There is no general rule and, in many cases, governments decide to include the activities of state investment banks under public spending: for example, the newly established UK Infrastructure Bank. Whether to include the activities of development banks in public debt figures or not is a matter of national accounting regulations as well as politics.

9 Strategic coordination between central banks and industrial investment banks goes back to the first industrial bankers of the 19th century when central banks acted as ‘the lenders of last resort’ for newly established, privately owned industrial banks. Borrowing short term from various private investors while investing long term in industrial enterprises generated the problem of maturity mismatch and authorisation of additional capital. For example, Banque de France was essential for overcoming this constraint when Credit Mobilier invested in the booming railroads (Sraffa 1929–1930; also Cameron Citation1953).

10 Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social

11 For example, Korea Development Bank provided technology evaluation training to civil servants from other public agencies (Mikheeva Citation2019).

12 This can involve either new technologies or the early stages of technological readiness. For example, the EIB runs the Energy Demo Facility project whereby finance is provided to help overcome the ‘valley of death’, i.e. to transition from demonstration to commercialization stages. Source: https://www.eib.org/attachments/thematic/innovfin_energy_demo_projects_en.pdf.

13 Although the operational links between technical and financial expertise remains unexplored and is not easy to capture.

References

- Ali, I. M. 1978. Relations of Central Banks with Treasuries, Planning and Development Agencies in Government. In T. B. Korea, The 12th SEANZA Central Banking Course Lectures, September 4-November 10, 402–408. Seoul: The Bank of Korea.

- Antonelli, C., ed. 2022. Elgar Encyclopedia on the Economics of Knowledge and Innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Barkawi, A., and S. Zadek. 2021. Governing Finance for Sustainable Prosperity. Council for Economic Policies Discussion Note. https://www.cepweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Barkawi-and-Zadek-2021.-Governing-Finance-for-Sustainable-Prosperity.pdf.

- Becker, M., N. Lazaric, R. P. Nelson, and S. G. Winter. 2005. “Applying Organizational Routines in Understanding Organizational Change.” Industrial and Corporate Change 14 (5): 775–791. doi:10.1093/icc/dth071.

- Bergek, A., S. Jacobsson, B. Carlsson, S. Lindmark, and A. Rickne. 2008. “Analyzing the Functional Dynamics of Technological Innovation Systems: A Scheme of Analysis.” Research Policy 37 (3): 407–429. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.12.003.

- Bergek, A., S. Jacobsson, M. Hekkert, and K. Smith. 2010. “Functionality of Innovation Systems as a Rationale for and Guide to Innovation Policy.” In The Theory and Practice of Innovation Policy. An International Research Handbook, edited by R. Smits, S. Kuhlmann, and P. Shapira, 117–146. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bezemer, D., J. Ryan-Collins, F. van Lerven, and L. Zhang. 2018. Credit Where its due: A Historical, Theoretical and Empirical Review of Credit Guidance Policies in the 20th Century. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper 2018-11. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/public-purpose/files/iipp-wp-2018-11_credit_where_its_due.pdf.

- Blair, C. 1964. “Nacional Financiera: Entrepreneurship in a Mixed Economy.” In Public Policy and Private Enterprise in Mexico, edited by R. Vernon, 191–240. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Borras, S., and J. Edler. 2020. “The Roles of the State in the Governance of Socio-Technical Systems’ Transformation.” Research Policy 49 (5), doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.103971.

- Borrás, S., and C. Edquist. 2019. Holistic Innovation Policy — Theoretical Foundations, Policy Problems and Instrument Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Braun, B. 2021. “Central Bank Planning for Public Purpose.” In Pandemic Exposures: Economy and Society in Time of Coronavirus, edited by D. Fassin and M. Fourcade, 105–122. Chicago: HAU Books.

- Braun, B., and L. Downey. 2020. Against Amnesia: Reimagining Central Banking. Council on Economic Policies, Discussion Note 2020/1. https://www.cepweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CEP-DN-Against-Amnesia.-Re-Imagining-Central-Banking.pdf.

- Burlamaqui, L. 2015. “Finance, Development and the Chinese Entrepreneurial State: A Schumpeter-Keynes-Minsky Approach.” Brazilian Journal of Political Economy 35 (4): 728–744.

- Burlamaqui, L. 2020. “Schumpeter, the Entrepreneurial State and China. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2020-15).” https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2020-15.

- Burlamaqui, L., and R. Kattel. 2016a. “Development as Leapfrogging, not Convergence, not Catch-up: Towards Schumpeterian Theories of Finance and Development.” Review of Political Economy 28 (2): 270–288. doi:10.1080/09538259.2016.1142718.

- Burlamaqui, L., and R. Kattel. 2016b. “Assessing Divergent Development Trajectories: Schumpeterian Competition, Finance and Financial Governance.” Brazilian Journal of Innovation 15 (1): 9–32.

- Burlamaqui, L., and J. A. Kregel. 2005. “Innovation, Competition and Financial Vulnerability in Economic Development.” Revista de Economia Política 25 (2): 5–22.

- Calder, K. 1993. Strategic Capitalism: Private Finance and Public Purpose in Japanese Industrial Finance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cameron, R. 1953. “The Crédit Mobilier and the Economic Development of Europe.” Journal of Political Economy 61: 461–488. doi:10.1086/257433.

- Campiglio, E. 2016. “Beyond Carbon Pricing: The Role of Banking and Monetary Policy in Financing the Transition to a low-Carbon Economy.” Ecological Economics 121: 220–230. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.03.020.

- Campiglio, E., Y. Dafermos, P. Monnin, J. Ryan-Collins, G. Schotten, and M. Tanaka. 2018. “Climate Change Challenges for Central Banks and Financial Regulators.” Nature Climate Change 8: 462–468. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0175-0.

- Cimoli, M., J. A. Ocampo, G. Porcile, and N. Saporito. 2020. “Choosing Sides in the Trilemma: International Financial Cycles and Structural Change in Developing Economies.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 29 (7): 740–761. doi:10.1080/10438599.2020.1719631.

- The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action. 2023. Strengthening the Role of Ministries of Finance in Driving Climate Action. A Framework and Guide for Ministers and Ministries of Finance. https://www.financeministersforclimate.org/reports.

- Dahi, O., and F. Demir. 2016. South-South Trade and Finance in the Twenty-First Century: Rise of the South or a Second Great Divergence. London and New York: Anthem Press.

- De Carvalho, F. J. C. 1995. “The Independence of Central Banks: A Critical Assessment of the Arguments.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 18 (2): 159–175. doi:10.1080/01603477.1995.11490066.

- Development Bank of Japan and Japan Economic Research Institute. 1999. Development Banking in the New Millennium: An Evaluation of Development Banking in Selected Countries and Lessons for the Future. ISBN 4-89110-003-6.

- Dikau, S., and J. Ryan-Collins. 2017. Green Central Banking in Emerging Market and Developing Country Economies. New Economic Foundation. http://neweconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Green-Central-Banking.pdf.

- Dikau, S., and U. Volz. 2018. Central Banking, Climate Change and Green Finance. ADBI Working Paper 867. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. https://www.adb.org/publications/central-banking-climate-change-and-green- finance.

- Dikau, S., and U. Volz. 2020. Central Bank Mandates, Sustainability Objectives and the Promotion of Green Finance. No. 232. London. https://www.soas.ac.uk/economics/research/workingpapers/file145514.pdf.

- Dikau, S., and U. Volz. 2021. Out of the Window? Green Monetary Policy in China: Window Guidance and the Promotion of Sustainable Lending and Investment. Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy Working Paper 388/Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper 360. London School of Economics and Political Science. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/35145/1/working-paper-360-Dikau-Volz.pdf.

- Dow, S. 2014. “Animal Spirits and Organization.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 37 (2): 211–231.

- Edquist, C. 2004. “Systems of Innovation: Perspectives and Challenges.” In Oxford Handbook of Innovation, edited by J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery, and R. R. Nelson, 181–208. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ESPON. 2018. COMPASS – Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Final Report. Retrieved from: https://www.espon.eu/planning-systems.

- Fagerberg, J. 2017. “Innovation Policy: Rationales, Lessons and Challenges.” Journal of Economic Surveys 31 (2): 497–512. doi:10.1111/joes.12164.

- Fagerberg, J. 2022. “Innovation Policy.” In Elgar Encyclopedia on the Economics of Knowledge and Innovation, edited by C. Antonelli, 229–235. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Felipe, J. 2015. Development and Modern Industrial Policy in Practice: Issues and Country Experiences. Cheltenham: Asian Development Bank and Edward Elgar.

- Ferraz, J. C., and L. Coutinho. 2019. “Investment Policies, Development Finance and Economic Transformation: Lessons from BNDES.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 48: 86–102. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2017.11.008.

- Gabor, D. 2023. The (European) Derisking State. SocArXiv. May 17. doi:10.31235/osf.io/hpbj2

- Gallagher, K., and R. Porzecanski. 2011. The Dragon in the Room: China and the Future of Latin American Industrialization. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Geddes, A., T. Schmidt, and B. Steffen. 2018. “The Multiple Roles of State Investment Banks in low-Carbon Energy Finance: An Analysis of Australia, the UK and Germany.” Energy Policy 115: 158–170. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.01.009.

- Geok, W. B., T. Gleave, and I. Buche. 2006. DBS Bank – Ship Financing Challenges in Asia. Case no ABCC-2006-003. Nanyang Technological University and Maritime Port of Authority of Singapore.

- Gottschalk, R., J. Xu, and L. Barros. 2020. Financial Regulation of National Development Banks – NDBs. Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Research paper no 173. https://www.afd.fr/sites/afd/files/2020-11-11-43-44/financial-regulation-national-development-banks.pdf.

- Griffith-Jones, S., and N. Naqvi. 2020. Industrial Policy and Risk-Sharing in Public Development Banks: Lessons for the Post-COVID Response from the EIB and EFSI. Oxford: Global Economic Governance Programme, University of Oxford.

- Griffith-Jones, S., and J. A. Ocampo. 2018. The Future of National Development Banks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Guter-Sandu, A., and S. Murau. 2022. “The Eurozone’s Evolving Fiscal Ecosystem: Mitigating Fiscal Discipline by Governing Through off-Balance-Sheet Fiscal Agencies.” New Political Economy 27 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1080/13563467.2021.1910648.

- Hanusch, H., and A. Pyka. 2006. Manifesto for Comprehensive neo-Schumpeterian Economics. Discussion Paper Series 278, Universitaet Augsburg, Institute for Economics. https://www.wiwi.uni-augsburg.de/vwl/institut/paper/289.pdf.

- Hekkert, M. P., R. A. Suurs, S. O. Negro, S. Kuhlmann, and R. E. Smits. 2007. “Functions of Innovation Systems: A New Approach for Analysing Technological Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (4): 413–432.

- Howlett, M. 2015. “Policy Analytical Capacity: The Supply and Demand for Policy Analysis in Government.” Policy and Society 34 (3-4): 173–182. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.002.

- Jayasuriya, K. 2004. “The new Regulatory State and Relational Capacity.” Policy & Politics 32 (4): 487–501. doi:10.1332/0305573042009462.

- Jayasuriya, K. 2005. “Beyond Institutional Fetishism: From the Developmental to the Regulatory State.” New Political Economy 10 (3): 381–387. doi:10.1080/13563460500204290.

- Johnson, Ch. 1999. “The Developmental State: Odyssey of a Concept.” In The Developmental State, edited by M. Woo-Cummings, 32–60. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kattel, R. 2023. “Dynamic Capabilities of the Public Sector: Towards a New Synthesis.” Revista do Serviço Público 74 (1): 12–41.

- Kattel, R., W. Drechsler, and E. Karo. 2022. Innovation Bureaucracy: Let’s Make the State Entrepreneurial. Yale University Press.

- Kattel, R., and V. Takala. 2021. Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector: The Case of the UK’s Government Digital Service. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2021/01). https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2021-01.

- Kavvadia, H. 2020. “From a Policy Bank to a Crowding-in Bank: The Development of the European Investment Bank in the Last ten Years, as Seen Through its Business Model.” Croatian Regional Development Journal 1 (1): 27–38. doi:10.2478/crdj-2021-0003.

- Kedward, K., D. Gabor, and J. Ryan-Collins. 2022. “Aligning Finance with the Green Transition: From a Risk-based to an Allocative Green Credit Policy Regime.” UCL Institute for Innovation and PublicPurpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2022-11). 2022–2033. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2022-11.

- Kedward, K., J. Ryan-Collins, and H. Chenet. 2020. Managing Nature-Related Financial Risks: A Precautionary Policy Approach for Central Banks and Financial Supervisors. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2020-09). https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2020-09.

- Keynes, J. M. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- King, R., and R. Levine. 1993. “Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might be Right.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108 (3): 717–737. doi:10.2307/2118406.

- Kivimaa, P., and K. S. Rogge. 2022. “Interplay of Policy Experimentation and Institutional Change in Sustainability Transitions: The Case of Mobility as a Service in Finland.” Research Policy 51 (1): 104412. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2021.104412.

- Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW). 2016. Regulation of Promotional Banks and Potential Impacts. KfW Papers and Proceedings on Economics. https://www.kfw.de/PDF/Download-Center/Konzernthemen/Research/PDF-Dokumente-Studien-und-Materialien/PDF-Dateien-Paper-and-Proceedings-(EN)/Regulation-of-promotional-banks-November-2016.pdf.

- Kregel, J. A. 2009. “The Global Crisis and the Implications for Developing Countries and the BRICs: Is the "B" Really Justified?” Revista de Economia Política 29 (4): 341–356. doi:10.1590/S0101-31572009000400002.

- Kregel, J. A., and L. Burlamaqui. 2005. “Banking and the Financing of Development: A Schumpeterian and Minskyan Perspective.” In Reimagining Growth: Toward a Renewal of the Idea of Development, edited by S. De Paula and G. A. Dymski, 141–168. London: Zed Books.

- Lee, K. 2019. “Financing of Industrial Development in Korea and Implications for Africa.” In The Oxford Handbook of Structural Transformation, edited by C. Monga and J. Lin, 549–570. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lerner, A. P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt.” Social Research 10 (1): 38–51.

- Levine, R. 2012. “The Governance of Financial Regulation: Reform Lessons from the Recent Crisis.” International Review of Finance 12 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2443.2011.01133.x.

- Lütz, S. 2004. “Convergence Within National Diversity: The Regulatory State in Finance.” Journal of Public Policy 24 (2): 169–197. doi:10.1017/S0143814X04000091.

- Macfarlane, L., and M. Mazzucato. 2018. State Investment Banks and Patient Finance: An International Comparison. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2018-01).

- Marois, T. 2021a. Public Banks: Decarbonisation, Definancialisation and Democratisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marois, T. 2021b. “A Dynamic Theory of Public Banks (and Why it Matters).” Review of Political Economy 34 (2): 356–371. doi:10.1080/09538259.2021.1898110.

- Mazzucato, M. 2013. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking the Public vs. Private Myth in Risk and Innovation. London: Anthem.

- Mazzucato, M. (2019). Governing Missions in the European Union. Report for the European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/research_and_innovation/contact/documents/ec_rtd_mazzucato-report-issue2_072019.pdf.

- Mazzucato, M., M. Carreras, and O. Mikheeva. 2023. Steering Economic Recovery in Europe: Lessons for Governing the Recovery and Resilience Facility. European Parliament Study Series. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/699556/IPOL_STU(2023)699556_EN.pdf.

- Mazzucato, M., and O. Mikheeva. 2020. “The EIB and the New EU Missions Framework: Opportunities and Lessons from the EIB’s Advisory Support to the Circular Economy.” UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP). Policy Report (IIPP WP2020-17). https://www.eib.org/attachments/press/eib-and-new-eu-missions-framework-report-18-nov-en.pdf.

- Mazzucato, M., and C. Penna. 2016. “Beyond Market Failures: The Market Creating and Shaping Roles of State Investment Banks.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 19 (4): 305–326. doi:10.1080/17487870.2016.1216416.

- Mazzucato, M., and G. Semieniuk. 2017. “Public Financing of Innovation: New Questions.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1): 24–48. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grw036.

- Mazzucato, M., and R. Wray. 2019. “(Re)Introducing Finance Into Evolutionary Economics: Keynes, Schumpeter, Minsky and Financial Fragility.” In Schumpeter’s Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy: A Twenty First Century Update, edited by L. Burlamaqui and R. Kattel, 135–161. Oxford: Routledge.

- Mérő, K., and D. Piroska. 2016. “Banking Union and Banking Nationalism — Explaining opt-out Choices of Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic.” Policy and Society 35 (3): 215–226. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2016.10.001.

- Mertens, D., and M. Thiemann. 2018. “Market-based but State-led: The Role of Public Development Banks in Shaping Market-based Finance in the European Union.” Competition and Change 22 (2): 184–204.

- Mikheeva, O. 2018. Institutional Context and the Typology of Functions of National Development Banks. The case of Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) in Malaysia (No. 82). TUT Ragnar Nurkse Department of Innovation and Governance. http://hum.ttu.ee/wp/paper82.pdf.

- Mikheeva, O. 2019. “Financing of Innovation: National Development Banks in Newly Industrialized Countries of East Asia.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 42 (4): 590–619. doi:10.1080/01603477.2019.1640065.

- Mikheeva, O., and J. Ryan-Collins. 2022. Governing Finance to Support the net-Zero Transition: Lessons from Successful Industrialisations. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (No. WP 2022/01). https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2022-01.

- Mikheeva, O., and P. Tõnurist. 2019. “Co-Creation for the Reduction of Uncertainty in Financial Governance: The Case of Monetary Authority of Singapore.” Administrative Culture 19 (2): 60–80. doi:10.32994/hk.v19i2.199.

- Minsky, H. P. 1986. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mukherjee, I., and A. S. Bali. 2019. “Policy Effectiveness and Capacity: Two Sides of the Design Coin.” Policy Design and Practice 2 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1080/25741292.2019.1632616.

- Naqvi, N., A. Henow, and H.-J. Chang. 2018. “Kicking Away the Financial Ladder? German Development Banking under Economic Globalization.” Review of International Political Economy 25 (5): 672–698.

- Nell, E. J., and M. Forstater. 2003. Reinventing Functional Finance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nelson, R., and S. Winter. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Newell, P., F. Daley, O. Mikheeva, and I. Peša. 2023. “Mind the gap: The Global Governance of Just Transitions.” Global Policy 14 (3): 425–437. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.13236.

- Painter, M., and J. Pierre, eds. 2005. Challenges to State Policy Capacity: Global Trends and Comparative Perspectives. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peters, B. G. 2015. “Policy Capacity in Public Administration.” Policy and Society 34 (3-4): 219–228. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.005.

- Peters, G., and J. Pierre. 2016. Comparative Governance: Rediscovering the Functional Dimension of Governing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quaglia, L. 2014. “The Sources of European Union Influence in International Financial Regulatory Fora.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.882970.

- Radosevic, S. 2001. “Pan-European Industrial Networks as Factors of Convergence and Divergence Within Europe.” In Interlocking Dimensions of European Integration. One Europe or Several?, edited by H. Wallace, 45–67. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Raudla, R., L. Mjøset, R. Kattel, A. Cepilovs, O. Mikheeva, and B.-S. Tranøy. 2018. “Different Faces of Fiscal Bureaucracy.” Administrative Culture 19 (1): 5–36. doi:10.32994/ac.v19i1.177.

- Sanderson, H., and M. Forsythe. 2013. China’s Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence – How China Development Bank is Rewriting the Rules of Finance. New York: Wiley.

- Schumpeter, J. A. [1911]1961. The Theory of Economic Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Seabrooke, L., and E. Tsingou. 2014. “Distinctions, Affiliations, and Professional Knowledge in Financial Reform Expert Groups.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (3): 389–407. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.882967.

- Skovgaard, J. 2017a. “Limiting Costs or Correcting Market Failures? Finance Ministries and Frame Alignment in UN Climate Finance Negotiations.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 17 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1007/s10784-016-9348-3.

- Skovgaard, J. 2017b. “The Role of Finance Ministries in Environmental Policy Making: The Case of European Union Emissions Trading System Reform in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands.” Environmental Policy and Governance 27 (4): 351–364. doi:10.1002/eet.1767.

- Stoker, G. 1998. “Governance as Theory: Five Propositions.” International Social Science Journal 50 (155): 17–28. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00106.

- Teece, D. J. 2016. “Dynamic Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Management in Large Organizations: Toward a Theory of the (Entrepreneurial) Firm.” European Economic Review 86: 202–216.

- Teece, D. J. 2022. Evolutionary Economics, Routines, and Dynamic Capabilities. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2022-17). https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/wp2022-17.

- The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action. 2023. “Strengthening the Role of Ministries of Finance in Driving Climate Action. A Framework and Guide for Ministers and Ministries of Finance.” Final Report. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wpcontent/uploads/2023/08/Strengthening_the_role_of_Ministries_of_Finance_in_driving_action_Framework_and_guide_FULL_REPORT.pdf.

- Thurbon, E. 2001. “Two Paths to Financial Liberalization: South Korea and Taiwan.” The Pacific Review 14: 241–267. doi:10.1080/09512740110037370.