ABSTRACT

With a strong policy focus on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the least developed countries (LDCs), there is a demand for information that can inform efforts to promote innovation, technological development and SME development. This paper presents results from a bibliometric analysis of publications on SME development in the LDCs. It was informed by different perspectives on how SME innovation occurs: mainstream emphasis on formal research and development and a framework emphasizing learning and organizational capabilities. The results show that there are low levels of research on SME development in the LDCs and generally there is limited coverage on topics that can inform SME innovation and technological development in SMEs. Our findings highlight the need for further research on SME development in LDCs that is informed by a wide perspective of what innovation and technological development are in these countries and can guide policy efforts.

1. Introduction

The development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has, in recent decades, been emphasized in policies and programmes in many countries classified as least developed countries (LDCs), and has been a part of their efforts to promote innovation. Some countries, such as Bangladesh, have opted to develop specific SME policies (Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Citation2019). Other countries, such as Tanzania and Rwanda have promoted SME development as a part of their larger entrepreneurship strategies (Republic of Rwanda Citation2020; United Republic of Tanzania Citation2017).

An emphasis on SMEs in developing countries has been reinforced by multilaterals and donors. Acs and Virgill (Citation2010) argue that when developing countries and donors started to recognize that import substitution and export orientation policies failed to deliver the expected economic benefits, the attention shifted to the SME sector. This is, for instance, reflected in the work of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which stated that SMEs are important drivers for economic growth across Sub- Saharan Africa (IFC Citation2014). In the same vein donors, such as the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), announced their intention to support 300,000 SMEs in low-income countries (DFID, Citation2011). This focus on SME development is aligned with what is happening in the rest of the world. SMEs represent 95% of firms globally and have been estimated to contribute more than half of global employment (IFC Citation2021; World Bank Group Citation2017, Citation2020). Both formal and informal SMEs contribute massively to GDP and economic growth.

Many LDCs aspire to enhance their innovation and economic standing and reach middle-income classification in the near future. They are also among the countries which, in the pre-COVID-19 years, had some of the highest GDP growth rates. In 2019, Rwanda had, for example, an annual GDP growth rate of 9.4%, and Bangladesh had a growth rate of 8.2% for the same year (IMF Citation2022). Typically, LDCs have relatively young populations with large numbers of young people entering the labour forces every year. It can be challenging for countries to provide masses of young people with employment opportunities. Promoting SME development has become one of the tools that governments in LDCs have applied to avoid a high rate of youth unemployment and to enhance their innovation and economic standing.

There are a number of avenues that can be pursued when promoting innovation and SME development in the LDCs, as is the case in other countries. To provide input into these efforts, there is a demand for research that analyses how SME innovation in the LDCs is carried out. There is a long history of research on innovation and SME development – and more generally on entrepreneurship – in what are now classified as high-income countries. Research on entrepreneurship can be traced as far back as to Richard Cantillon, an Irish businessman and banker in the eighteenth century (Thornton Citation2010). Later Joseph Schumpeter drew attention to entrepreneurs and business creation and popularized the concept of ‘creative destruction’ (McGraw Citation2007). With the growing role of SMEs, research on entrepreneurship development has been expanding in high-income countries. Mapping this expansion, its features and examining its impact has become a regular endeavour (Ferreira, Reis, and Miranda Citation2015; Meyer Citation2012). This allows researchers and policy makers to measure changes in knowledge production focused on SME development, and to identify potential research gaps the bridging of which can provide policy insights.

While research can provide insights into how to stimulate SME development and innovation in high-income countries, it is not clear to what extent research exists that can cast light on and support SME development in LDCs. Poole (Citation2018) argues that the assertion made by Lingelbach et al in the early 2000s is still valid, that entrepreneurship in developing economies is the least studied economic and social phenomenon today (Lingelbach, de la Vina, and Asel Citation2005). The implication of this is that ‘policymakers are faced with taking decisions that constitute nothing more than leaps of faith based on an unproven discourse’ (Poole Citation2018). Poole argues that there is a risk when a policy emphasis is made on an under-researched field, in the sense that interest groups can more easily hijack the agenda. The limited research on entrepreneurship in developing economies is also not likely to be focused on the poorest countries in the world. A recent analysis showed that research on innovation in developing countries, including management, economics, and business research, was predominantly aimed at upper-middle income countries and many low-income countries are marginalized. (Lema, Kraemer-Mbula, and Rakas Citation2021).

Previous research has also shown limited participation of developing countries´ authors in research on economic issues. Amarante et al. (Citation2022) analyzed the contributions of developing countries' researchers at the most prestigious development conferences, their publications in the top 20 journals in development studies and the citations of their research. Their results showed only one in six articles was being authored by Southern researchers. In comparison, almost three-quarters of the papers were authored by Northern researchers. The authors argue that one of the reasons for this under representation is a culture of exclusivity in the profession of economics (Amarante et al. Citation2022; Bayer and Rose Citation2016).

Thorsteinsdottir, Bell, and Bandyopadhyay (Citation2020) have also shown a relatively weak involvement of locally affiliated authors in the SME research on LDCs, with less than half of the publications studied, having authors with local affiliations. This may reflect a limited capacity in the LDCs to do SME-focused research and a need for specific training of local experts in carrying out entrepreneurship research. It may also reflect a lack of research funding. With more local participation the research may be better grounded and can better inform policies and programmes to promote SME development in the LDCs.

With the large policy emphasis on promoting SME and innovation in the LDCs, there is an unmet demand for research to inform evidence-based policies and programmes. Under some circumstances, it can be useful for LDCs to have access to the massive literature on SME development in high-income countries. However, SME and entrepreneurship development are highly context dependent. The culture of entrepreneurship differs widely among countries, and the institutional structure and the wider environment for business development are diverse across nations. Research on innovation and SME development in these countries, therefore, needs to cast a clear light on the specific challenges they face and examine approaches to address them that are adjusted to the local conditions. There is a need for a more in-depth focus on the context of entrepreneurship development which is more informed by evolutionary approaches from the innovation systems literature (Schmutzler, Pugh, and Tsvetkova Citation2022).

1.2. An emphasis on technology development

One approach the LDCs, have followed to promote innovation in their countries has been to promote technology-intensive SME development and technology adoption by SMEs with a strong emphasis on information and communication technologies (ICT). A focus on these technologies is echoed in development policies from early on, and some of the countries have been building the necessary infrastructure to push this front. More recently the emphasis on ICT has been reflected in digitalization policies, including e-marketing and e-commerce. Senegal, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia have, for instance, all developed digitalization strategies, which include an emphasis on strengthening their SME sector with ICT development (Thorsteinsdottir, Bell, and Bandyopadhyay Citation2021). Generally, there appears to be a heavier focus on using digital technologies in these policies than on developing local technology-based industries. The policies' goals are typically to stimulate the integration of digital technologies in the public and private sectors, to stimulate the quality of their services and the enhancement of products. While these policies do at times not have much in common with SME policies, strengthening SME innovation through digitalization is a common theme which includes an emphasis on digital marketing and e-commerce. In some of these policies, there is also a focus to promote technology-based SMEs. Because of the policy emphasis on digitalization and relevance to SME development, we decided to include an analysis of if and how the available SME development literature addresses technology development in general, including ICT and digitalization and thereby can inform policy development and implementation.

Another recent policy emphasis in some LDCs relevant to SME development is start-up acts. Senegal developed a start-up act in 2020, which supports new, typically technology-based, SME development (République du Sénégal Citation2020). It became the third country in the world to do so, following the lead of Italy and Tunisia. These acts are a set of legislative and regulatory frameworks, often involving tax incentives, or subsides aimed at fostering SME development, particularly by technology-intensive firms (Rodrigues Citation2021). The acts are often pushed by technology-based SMEs and developed in a participatory manner directly involving collaboration between policy makers and local SMEs. The development of start-up policy tools is therefore closely aligned with technology development but again it is not clear to what extent these tools are informed by research.

1.3. Innovation in LDCs SMEs

In order to identify the extent to which existing research on LDCs is relevant for promoting SME innovation and technology development in these countries, it is important to understand how innovation can take place in SMEs in LDCs. Ernst et al argued for a wide perspective of innovation when focusing on developing countries and defined it as: ‘the processes by which firms master and implement the design and production of goods and services that are new to them, irrespective of whether or not they are new to their competitors – domestic or foreign’ (Ernst, Mytelka, and Ganiatsos Citation1998). Innovation therefore would involve the adoption of existing processes and capacity building, often involving tacit knowledge. A focus only on new-to-the world innovation would, as a result, leave out much innovative efforts of firms in the LDCs. Lundvall et al. (Citation2009) emphasized that innovation in developing countries in general, derives from processes of science-based and experience-based learning (Lundvall et al. Citation2009). Any analyses on innovation in the LDCs thus need to include a wider perspective than considering only science-based innovation activities. This aligns with von Hippel who emphasized the key role of the interactions with end-users in the innovation process, which would involve experience-based learning (Von Hippel Citation1988).

Kraemer-Mbula et al. have analyzed innovation in micro- and small enterprises (MSEs) in four countries in Africa, including two LDCs, Tanzania and Uganda (Kraemer-Mbula et al. Citation2019). They argue that the mainstream conceptual frameworks applied to analyze innovation reflect the socioeconomic features of high-income countries and typically consider innovation processes as only driven by expenditure on formal research and development (R&D) and the input of engineers and scientists. This has underestimated innovation efforts in African countries. Innovation surveys on the continent, for example, do not capture the innovation activities of MSEs as they are guided by such conceptual frameworks. The surveys also only include registered firms, as opposed to the informal firms that are prevalent on the continent and are typically limited to firms of 10 employees or more, leaving out micro enterprises and smaller SMEs. By including informal firms and smaller SMEs and a much wider perspective of what constitutes innovation processes, Kraemer-Mbula's et al findings demonstrated that the MSEs in the countries they studied were indeed engaged in innovation. They demonstrated that even though the firms were focusing on R&D to a limited extent, they were engaging in learning, capability development and innovation and that these three processes were closely intertwined.

In their research, Kraemer-Mbula et al emphasized that the innovation was expressed in how employees at the MSEs work and interact to solve problems of their firm operations. This is based on insights from work on organizational capabilities and dynamic capabilities reflecting the ability of firms to learn and recombine knowledge to adapt to changing environments (Dosi and Teece Citation1998; Nelson and Winter Citation1982; Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997). While it is difficult to measure firms' learning, Kraemer-Mbula et al have developed a taxonomy of the learning mechanisms of firms in developing countries (). It is informed by research on work organization and capability development in developing countries. The firms do not in general undertake formal R&D, have few linkages with universities or research institutes and their learning is typically informal and involves learning-by-doing. The framework is informed by the notion that learning and capability development rely on two types of knowledge, codified science-based knowledge and practical experience-based knowledge and the latter is more important for SME innovation in the LDCs. Also, the learning can be internal within the firm or external from other organizations or through interactions with other institutions, firms, users or suppliers.

Table 1. A taxonomy of learning mechanism.

The overarching question this paper address is to examine to what extent the available literature on SME/entrepreneurial development (hereafter called SME development) focuses on issues relevant to innovation in the LDCs and which thereby can inform policy making to promote SME innovation in the LDCs. With the expectation that technology development is particularly important for SME development in many LDCs, expressed by their emphasis on digitalization policies, the paper will also examine to what extent the available research on SME development can guide technology-intensive development.

To guide this research, we will rely on the taxonomy of learning presented in . The taxonomy will inform what keywords to use to capture research that can be relevant to SME innovation in the LDCs. By relying on the taxonomy, we will cast a wide net in identifying innovation processes relevant to the LDCs. On the one hand, we will evaluate the extent of literature that reflects a concentration on formal R&D. But our central focus will, on the other hand, be to look at research on learning and SME interactions in these countries.

To put the research on SME innovation in a wider context we will start by exploring the extent the existing research focuses on SME development in the LDCs in general and examine if there have been any considerable changes over the years.

The specific questions addressed in this paper are:

What is the extent of research on SME development in the LDCs?

How many research publications are there on SME development in the LDCs during the period studied?

Are there any considerable changes in the volume of publications over the years?

Which LDCs are most frequently focused on in this research?

Is the research on SME development in the LDCs focusing on understanding and promoting topics relevant to innovation in the LDCs?

Is the research on SME development in the LDCs addressing technological issues and technology development of the LDCs?

2. Methodology

To address these questions, we conducted a bibliometric analysis of publications on SME and entrepreneurship development in the LDCs. The approach we used in this research was to start by building a dataset with as many publications on SME development in the LDCs, as possible from the period from 2010 to 2019. We then explored the extent of this research in the LDCs and its focus on innovation and technology development. To build a dataset, we used both the Scopus database and the EBSCO database platform, to retrieve publications on this topic. Scopus is a multidisciplinary database with around 90 million records. Apart from journal articles and conference papers, Scopus has started to include books and book chapters. EBSCO is a database platform that connects to a number of different databases, including JSTOR, ERIC, SciELo, World Bank eLibrary, African Journals Online and Google Scholar. It covers a wider range of publications than typical research databases, as it also includes grey literature in the form of academic dissertations, reports and working papers that are not typically peer-reviewed.

Countries define SMEs differently, but typically they are defined according to how many employees firms have, or how much income they make. According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), developing economies typically define SMEs as employing between 10 and 49 employees, whereas micro enterprises employ less than ten staff (UNIDO Citation2005). We searched the databases using variations of the key words ‘SME’, ‘Small and medium firms’, Small and medium enterprises' and ‘entrepreneur’, which includes also entrepreneurial and entrepreneurship. We paired these keywords with ‘least developed countries’ or ‘LDCs’ and the names of the 46 countries listed as LDCs by the United Nations (UN Citation2021). Before selecting a publication for our dataset, we read each paper's abstract to evaluate whether the paper was focused on promoting entrepreneurship or SME development. If the paper was, for instance, primarily on promoting energy development, or agriculture by involving a SME, we rejected the paper as an entry for the dataset. If there was any doubt about an entry, both authors read the abstracts independently and judged its relevance.

We then cleaned the dataset and ensured that it did not include the same publication multiple times. Afterwards, we examined the volume, the changes over time, the focal country/countries of the papers and the extent to which the publications researched innovation as well as technology issues. To do so we read the abstracts once again and identified and coded the main themes each paper addressed. We then searched the abstracts of the SME development dataset for references to topics related to terms in the taxonomy of learning presented in . We used variations of the keywords aimed at catching R&D, learning, and terms such as interactions, knowledge exchange, networks, linkages and partnerships.

Lastly, we read the abstracts of each of the papers identified to confirm their thematic foci. For instance, we looked at how the papers focused on learning and the interactive terms and their alignment with , the taxonomy of learning mechanism. While guided our analysis we did not follow it to the letter and, as a result, there is not a complete alignment between and the research section. We started by searching for references to ‘innovation’ in the SME development dataset, which is a term not specifically referred to in . We also widened the searches by including related search terms such as networks and partnerships, which can provide a more complete coverage of innovation-related literature. We therefore included keywords encapsulating innovation, R&D, learning, knowledge exchanges, interactions, networks, linkages, and partnerships.

3. Results

3.1. Background features of research on SME development

Through the database searches, we identified a total of 1258 publications, published from 2010 to 2019, on the topics ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘SME’ development focused on the LDCs (). Most of the documents, or over 65%, were articles. With Scopus having enhanced its coverage in recent years to include book chapters and books in its database, and with the EBSCO platform including a wider range of publications, such as theses and reports, the types of publications were varied, as can be seen in . Still, the dataset includes relatively few publication types other than articles. Considering that it covers ten years, this would seem to be an underestimate of other publication types. For instance, several multilaterals and national governments have been actively producing reports on entrepreneurship issues in developing countries and the LDCs, but only 28 reports were generated in the search results for the period studied.

Table 2. Publications on SME development/entrepreneurship in the LDCs according to types of publications.

The dataset is, therefore, likely to underrepresent reports on entrepreneurship and SME development in the LDCs. The same observation applies to working papers. The dataset includes a number of working papers, mostly from multilateral organizations and organizations in high-income countries, but seems to underreport working papers produced by institutions in LDCs. As a result, this analysis cannot claim to include all publications on SME development/entrepreneurship in the LDCs. The high proportion of articles in journals reflects a relatively heavy involvement in quality control processes. In general, both local and international journals involve peer review processes that vet the publications and ensure they are of high enough quality to be published.

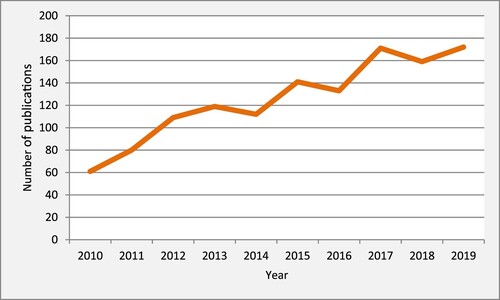

Considering that there are 46 LDCs in the world, the total number of SME development publications for all the LDCs is low (1258 papers), or on average less than 126 publications a year covering all types of SME and entrepreneurship topics for 46 countries. This confirms that limited efforts have been made to research entrepreneurship and SME development in general in LDCs. To explore whether there have been any changes in the emphasis on research on SME development/entrepreneurship over the period we studied, we looked at the number of documents published per year. In general, there is an increase over this period in the number of publications on SME development in the LDCs (). The increase from the beginning of the period until the end is almost three-fold. However, it is uneven, and some of the years experienced stagnation or a slight drop in publications. Overall, though, the data suggest that research on entrepreneurship is increasing in the LDCs, and the stock of knowledge on SME development is expanding.

By looking at publications per year it becomes even clearer how few publications focus on entrepreneurship and SME development issues in LDCs in general. If the publications were evenly distributed among the LDCs, which they are not, the increase in documents over the period would be from 1.25 publications per country, per year at the beginning of the period, to 3.66 publications per country per year at the end of the period studied.

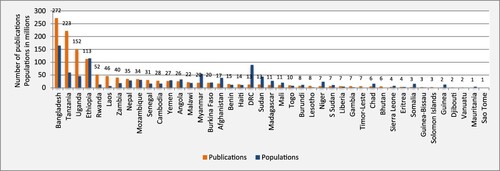

To get a better view of SME development/entrepreneurship in the LDCs, we analyzed our dataset at the country level. When we look at the focal countries for the publications in our dataset, it is evident that research on SME development/entrepreneurship focuses only on a few LDCs (). By far most documents concern entrepreneurship issues in Bangladesh, or around 22% of the papers. SME development in Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia are also relatively frequently researched. Over 60% of the papers on SME development/entrepreneurship are focused on these four countries. A total of four countries (Central African Republic, Comoros, Kiribati and Tuvalu) have no publications in these databases on SME development from 2010 to 2019. Over half of the LDCs have almost no research on these issues, with zero to ten publications over a ten-year period.

Figure 2. Publications on SME development/entrepreneurship in the LDCs and population size by country (2010–2019).

Note: The value numbers above each column refer to number of publications on SME development in the countries.

We also present the population sizes for each country (). This analysis shows that the top four countries in terms of a number of publications have also relatively large populations. Many of the countries with very few papers have relatively small populations. War torn countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Sudan, and Myanmar are not frequently focal countries for papers on SME development/entrepreneurship. A few countries, in addition to the top four countries, seem to have a relatively high number of papers on SME development/entrepreneurship compared to their population sizes. These are Rwanda, Laos, Zambia, Senegal, and Cambodia.

Even though the databases did include SME publications in various languages, it is quite possible that they have a bias for English-language coverage, and thus underestimate papers focused on non-English speaking countries. In general, there are substantial gaps in entrepreneurship research, which can lead to challenges in developing evidence-based policies and programmes to foster entrepreneurship in most LDCs. Considering that promoting SMEs is a common pillar of economic and industry policies, these gaps are likely detrimental to the countries' overall growth and diminish their ability to promote sustainable development.

3.3. Focus on innovation in research on SME development

3.3.1. Innovation

When we searched the abstracts of the whole SME development data set for references to innovation, we identified around 11% of the publications mentioning innovation in their abstracts. In many cases, innovation was just mentioned in passing and the publications didn't analyze innovation in any shape or form. A thematic review of the abstracts of the publications in the dataset identified only around 3% of the publications including innovation as a key theme.

Examples of publications that were very general are a paper on the importance of innovation for organizations in the twenty-first century (Uddin and Bose Citation2012) and another paper on the importance of innovation for achieving economic growth in Benin (Tokognon and Yunfei Citation2018). There were also papers that discussed the importance and roles of SMEs more generally as engines of growth and sources of innovation, such as on Ugandan SMEs (Mugambe Citation2019), on SMEs from Bangladesh (Arafat and Ahmed Citation2013) and in Ethiopia (Gebremichael Citation2014). While these publications demonstrate the importance of SMEs for economic growth and innovation, they typically don't analyze the processes in any detail. Some publications emphasized the importance of entrepreneurship in promoting innovation, for example in East Timor (Xavier, Vieira, and Rodrigues Citation2014). A publication also identified variables that promote entrepreneurship development in Haiti (Eliccel Citation2016) and hinder such development in Angola, Madagascar, and Mozambique (Herrington and Coduras Citation2019) without much attention being paid to innovation. There are also several publications on entrepreneurial orientation and innovation with a focus on Ethiopia (Tessema Citation2013), Angola (António Citation2015), Bangladesh (McKenzie and Woodruff Citation2017), and Uganda (Abaho et al. Citation2017).

Access to finances is a challenge for SMEs in the LDCs so quite a few articles were focused on financing issues. Some of them did not address innovation in detail but were rather on financial arrangements, such as microfinancing. Several articles were, however, on topics, such as financial innovation in sub-Saharan Africa, in Ethiopia (Lingelbach et al. Citation2012), in Tanzania (Matare and Sreedhara Citation2019) as well as in Bangladesh (Qamruzzaman and Jianguo Citation2019). These publications typically discuss new ways of financing SMEs to improve their access to financing.

Several publications examine innovation by relying on the national innovation systems framework where they identify the main actors contributing to innovation. They include studies on the innovation systems in Ethiopia (Tegene Citation2016), Mudde, Gerba, and Chekol (Citation2015), and Zambia (Zulu Citation2017). Another perspective that looks at the main institutions involved in innovation is looking at what has been called the innovation ecosystem. This includes a publication on the innovation ecosystem in Cambodia (Ehst et al. Citation2018), and start-up ecosystem in Bangladesh (Iftekhar, Imran, and Sadia Citation2018). These publications generally map the main actors involved in innovation and tend not to present a detailed analysis of SMEs' roles in innovation.

Several publications that mention innovation in their abstracts are focused on technology. One thesis focused on technology transfer by a university in Tanzania to the informal economy (Szogs Citation2010), while another looked at the adoption of technological innovation by SMEs in Laos (Troilo Citation2014). One study looked at the technology innovation capability of firms in Ethiopia and concluded that technology innovation capability has a mediating role in the relationship between organizational learning capability and SMEs performance (Hailekiros and Renyong Citation2016). This is a deeper analysis of SME processes than most of the publications mentioned above.

There were also some publications in the SME development dataset examining innovation hubs and incubators. These include a study reviewing the incubation landscapes in Mozambique and Zambia (Naidoo-Swettenham and Miettinen Citation2015), on how innovation hubs can be better supported in Rwanda (Obeysekare, Mehta, and Maitland Citation2017) and how ICT hubs have impacted social economic development in Africa (Moraa and Gathege Citation2013). There was also a study on the implementation reality of hubs in Rwanda (Friederici Citation2018).

Some publications addressed specific innovation, such as frugal innovation (Peša Citation2018), or inclusive innovation (Jiménez Citation2019), while others addressed innovation in specific sectors such as in manufacturing in Yemen (Alqershi, Abas, and Mohd Mokhtar Citation2018) or in tourism sector in several countries, such as Gambia, Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania (Carlisle et al. Citation2013; Krishnan Citation2016; Sheldon and Daniele Citation2017).

There is thus quite a variety of SME research in the LDCs that includes a focus on innovation in their abstracts. It discusses innovation in many different countries, with several countries being in Sub-Saharan Africa. Most of the publications are general or focused on more macro issues, such as identifying the main actors involved in innovation rather than on understanding how innovation occurs in SMEs.

3.3.2. Formal R&D

We also looked at the extent the SME development publications in the dataset mentioned R&D as measuring formal learning presented in R&D was rarely discussed in the abstracts of the publications with less than 1% of the SME publications' referring to R&D. As discussed above, Kraemer-Mbula et al. (Citation2019) argued that R&D generally doesn't play a large role for SME innovation in most sub-Saharan Africa countries. This was confirmed by a publication that argued based on its research that the value of R&D, technological leadership and innovation is moderate for SMEs in Angola and companies prefer low-risk projects (António Citation2015). In the same vein, another publication argued that value proposition, quality and flexibility of SMEs can enable the firms to participate in global value chains with minimal capital, R&D and technology cost (Asamnew Citation2012).

There is, however, not a consensus on this topic and research on five LDCs in sub-Sharan Africa argued that R&D was one of the important determinants of SME innovation (Abubakar et al. Citation2019.) A study on SMEs in Sudan identified a lack of R&D leading to poor local capacity to build technology and a heavy reliance on foreign technologies (Nour Citation2011). Likewise, Vieira, Cabral, and Rodrigues (Citation2012) argued for the importance of R&D and said private investment in SMEs and R&D in key sectors is one of the four pillars of the economic framework in East Timor. A study on several ASEAN countries, including Laos, compared the main strategies firms engaged in R&D, versus those not engaged in R&D, use to promote innovation with the latter group emphasizing more human resource strategies (Tsuji et al. Citation2018).

In general, the research done on R&D by SMEs in the LDCs is so limited that its role in firm innovation remains quite unclear. This limited focus on R&D aligns well with the argument of Kraemer-Mbula et al. (Citation2019) that R&D investment is not important for SME innovation in most sub-Saharan Africa countries. If R&D is not important for SME innovation in the LDCs, the lack of research on SME development and R&D may, therefore, not have much impact on SME innovation in the LDCs. Below we will look further at whether the publications are discussing the key concepts presented in on informal learning and thereby are likely to provide relevant research to guide innovation efforts in the LDCs.

3.3.3. Learning

Learning on the job and learning by trial and error were emphasized by Kraemer-Mbula et al. (Citation2019) as contributors to innovation in the LDCs. When we looked at the whole set of publications on SME development, we identified about 4.5% of them to be focused on learning. Apart from Kraemer-Mbula et al none of these publications referred to learning-on-the job and learning-by-trial-and-error specifically. In some of these SME publications, there was only a mention of learning in the abstracts without the publication discussing learning in any detail. There were, for example, references to projects that included the name ‘learning’ even though learning was not a topic of the publication per se. Other publications referred only generally to learning without it being discussed in any detail. This included some publications on the national innovation systems, such as the national innovation system in Zambia which was mostly on policy aspects and made a cursory reference to learning (Zulu Citation2017). There were also several papers that referred to learning about the use of technologies, such as apps or ICT training or using technologies for collaborative learning. Other papers discussed education programmes that were focused on teaching entrepreneurship skills and typically did not include firms directly. A few of the learning programmes, for example, discussed how well these training programmes were aligned with the needs of SMEs in their focal countries.

There were a few publications that could contribute to promoting the understanding of the role of learning for SME innovation. A thesis argued that older firms in the apparel industry in Bangladesh had a performance advantage due to their accumulated experience and learning over the years (Faroque Citation2014). Other papers discussed learning-by-exporting where SMEs enhance their competitiveness when exporting and learning about international standards. (Vidavong Citation2019) and how globalization depends on the ability of firms to learn (Awuah and Amal Citation2011). One paper showed that organizational learning capability had strong positive effects both on technological innovation capability and firm performance in Ethiopia (Hailekiros and Renyong Citation2016). Another paper discussed how microcredit strategies shape learning by women in Tanzania (Sigalla and Carney Citation2012).

A few papers in the SME development dataset compared SME's learning orientation with market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation as enablers for SMEs to build dynamic capabilities (see e.g. Kibeshi and Nsubili Citation2019; Ngwa and Kabangu Citation2016; Sarker and Palit Citation2015; Tukamuhabwa Citation2011) There were inconclusive results on the importance of learning orientation and for example, research showed it to have no effects on SMEs in Bangladesh (Sarker and Palit Citation2015) Only a few of the publications on learning addressed the topic of learning through networking or generally discussed interactive learning which will be addressed further in section 3.3.4 below.

Thus, there appears to be limited research on SME development that analyses learning as a contribution to innovation by SMEs in the LDCs and there is scope for further research on how SMEs' learning can contribute to innovation in these countries.

3.3.4. Networks, linkages, interactive learning and partnerships.

3.3.4.1. Networks

When we searched network(s) as a search term in the abstracts of the SME development publications in the LDCs, close to 12% of the publications referred to them. Most of the publications are not likely to contribute to innovation studies. Some publications discussed, for example, ICT networks or road or plumbing networks. A common research theme was also a comparison of the access to networks by women versus male entrepreneurs, typically demonstrating poorer access by women. There were also publications that generally examined the importance of social ties, social networks, or social media networks rather than analyzing networking. A few publications mentioned that hubs or business incubators and access to venture capital provided opportunities to strengthen firms' networks without providing more details on how the networks function or can be promoted (Das, Hui, and Jamal Citation2017; Elmansori Citation2014; Friederici Citation2018).

The SME publications that may contribute to understanding networks for innovation were diverse and included network configuration and SME competitiveness in Tanzania (Kavenuke, Mboma, and Mbamba Citation2019), the nature and extent of relationships between entrepreneurial networks and their performance (Ng and Rieple Citation2014), an analysis of the interrelationships of internal and external supply chain integration in manufacturing-based firms in Malawi (Kanyoma, Agbola, and Oloruntoba Citation2018), the development of models of entrepreneurial networks in Uganda (Evans and Thomas Citation2013) and how social capital is embedded in a durable network of relationships (Rooks, Szirmai, and Sserwanga Citation2012).

Some publications focused on the role of networking in exporting and internationalization. They looked, for example, at the importance of networking for internationalization and on whether networking resources impacted export performance in Bangladesh (Faroque Citation2014; Faroque, Morrish, and Ferdous Citation2017), on how weak networking structures challenged SME's access to international markets in Tanzania (Kazimoto Citation2014), and on how institutional frameworks shaped the formation of domestic and international networks of exporting agricultural SMEs in Bangladesh (Bose Citation2019). Some research looked at current practices of collaborative networks and the challenges in forming them in Tanzania (Msanjila and Kamuzora Citation2010, Citation2012). There was also research that focused on the strengths of weak ties in Burkina Faso (Berrou and Combarnous Citation2012). Several publications looked at the effects of ecologies of innovation on entrepreneurial networking in Uganda (Mayanja et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

Networks and networking were common themes of the publications in the SME dataset, but only a small proportion of them seem relevant to innovation studies. In those publications, there are however diverse networking topics addressed which reflects the complexity of the various networks.

3.3.4.2. Linkages

When we searched for SME publications that included the word ‘link’ in their abstracts we identified over 7% of the publications in the dataset. Several of these also mentioned networks and thus have been discussed above. Most of the additional papers referred to linkages in a very general way, without analyzing them further or examining their value for the firms' innovation. They, for instance, mention in passing the linkages of firms with financial institutions. Others mentioned generally that there are links between lack of resources and SME internationalization or referred to the links of firms to markets without providing much detail. Several SME development publications also looked at linkages between the personality traits of entrepreneurs and SME performance.

The few papers that addressed linkages in detail, discussed linkages as a part of business strategies. For example, the supply chain performance in Uganda could be enhanced by linkages with marketing which could enhance organizational learning (Tukamuhabwa Citation2011) and the linkages between agile supply chain format and firm sales performance in Bangladesh (Alam et al. Citation2019). There were several papers that discussed linkages in terms of enhancing support to firms, such as how linkages with supporting bodies in Tanzania can improve the processing of agricultural raw products (Mashimba Citation2014), and how funds have linked investors with SME entrepreneurs in disadvantaged communities in Zambia (Dawson Citation2011). Related to this was a publication on how banks can establish relational links with SMEs as a business strategy in Angola (Paulo Citation2017). While these papers are focused on linking firms with available financial resources, there were also at least a couple of papers focused on linking firms in Bangladesh with sources of information, such as financial information, and providing marketing linkages and general counselling to firms in Nepal (Habib and Shah Citation2010; Rupakhetee Citation2012). Another paper compared the value of linkages of SMEs to large companies versus the informal sector in terms of creating value and generating income in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Herderschee, Kaiser, and Samba Citation2011). One paper had a more external focus and looked at the weak linkages between firms in Laos and regional economic integration (Kyophilavong, Vanhnalat, and Phonvisay Citation2017) and a couple of papers focused particularly on university-industry linkages in Tanzania (Kaijage Citation2010; Szogs Citation2010).

3.3.4.3. Interaction

Variations of interaction were mentioned in just under 5% of the SME publications in the dataset. When we looked at the publications most of them did not discuss topics that can directly enhance our understanding of innovation, such as interactive learning of firms. Several of the papers referred generally to human interactions or topics such as how religion and entrepreneurship interact. Other papers discussed the use of technologies to promote interactions or social media interactions. There were also papers that discussed interactions in data collection or between other variables that were a part of the study. There were also mentions of cross boarder interactions.

A few SME development publications promoted the importance of interactions for innovation and economic development. These included a book on entrepreneurship, innovation and economic development which was based on empirical research in several countries (Szirmai, Naudé, and Goedhuys Citation2011) Most of the countries were not LDCs but rather lower-middle income countries such as India and Vietnam. The book did however also analyze interactions and innovation in Ethiopia making it relevant for this paper. Related to this is a thesis that is guided by the National Innovation System's framework in its investigation of innovative entrepreneurship in Ethiopia (Tegene Citation2016); another thesis that looks at the interactions of actors and structure in local economic development in Afghanistan through the lens of social institutions (Ritchie Citation2013), and a thesis looking at the importance of interaction in science, technology, and innovation in Zambia (Zulu Citation2017). Some of the publications focused on more specific interactions such as SME's interactions with customers in Rwanda (Xavier Citation2013), interactions of SMEs with government departments in Myanmar (Rand et al. Citation2019), interactions involving marketing developing programmes in Rwanda (Wakkee, Barua, and Van Beukering Citation2014), and interactions of large firms to support SMEs in Mozambique (Sawaya and Bhero, Citation2017).

There was also a discussion of interactions for ICT development, of, for example, increasing interactions between users and developers of apps aimed at entrepreneurs in Senegal (Scharff et al. Citation2016). Interactions were also a theme to analyze strategies for start-up development. This included an initiative to provide an interactive environment to enhance the start-up decision process in Uganda (Ejiri and Sol Citation2012; Sol, Ejiri, and Nabukenya Citation2011).

Even though there were fewer numbers of SME publications in the dataset that analyzed interactions than networks and linkages, those publications seem to emphasize contributions to innovation to a larger extent. They also were focused on several LDCs, including several sub-Saharan African countries.

3.3.4.4. Partnerships

When we looked at references to partnerships in the SME development dataset, we identified just over 3% of the publications that discussed them. Further scrutiny showed that only a few of these papers discussed firm-led partnerships. Instead, they more often addressed partnerships involving governments that funded or led initiatives or supported infrastructure development. There was also discussion of partnerships between financial institutions in providing support to firms. In other cases, the discussion of partnerships was too general to cast light on SME partnerships, for example stating only that the SMEs need partnerships. There were also some publications that referred to partnerships as a type of firm and contrasted it with a sole proprietary firm. International partnerships were also mentioned, involving governments or multinationals.

A few publications that addressed firm-led partnerships examined how firms gained access to expertise through partnerships. This included a paper analyzing Tanzanian programmes and policy support emphasizing the need for partnerships to access expertise (Abdulla and Othman Citation2011) and a paper specifically on how e-commerce firms in Tanzania established partnerships to be able to better solve technical problems (Kabanda and Brown Citation2017). Related to this was a publication that examined how an NGO could transform into a social enterprise in Burkina Faso by relying on partnerships (Dumalanède and Payaud Citation2018). There were a couple of papers addressing how partnerships were a business strategy to gain market leadership positions, one addressed strategic alliances in service/construction firms in Afghanistan (Sahibzada and Foghani Citation2014), while the other looked at innovative management techniques and technology transfer involving SMEs in Nepal (Tiwari Citation2019).

Very few publications have examined SME-led partnerships. Research involving partnerships in LDCs is much more likely to be focused on involving partnerships involving public sector actors than SMEs. While it is an important topic it does not cast light on the complex topic of partnership formation by SMEs in the LDCs.

This review of the contributions of the research on SME development to innovation in the LDCs, does in general not contribute much towards understanding either formal or informal learning by SMEs, in the LDCs. The review shows only a few pockets of literature that could cast light on the topic. Considering that SME innovation is likely to be shaped by local contexts, there is a large unmet demand for future research in this area.

3.4. Focus on technology in research on SME development

As discussed above, there is a policy emphasis on technology development by many LDC governments and more specifically on ICT development and digitalization by SMEs. One of the objectives of this research is to examine the extent to which research on SME development focuses on technology and technology-based firms. We decided to cast a wide net and look at any mentions of technology or technology development in the abstracts of the papers. In general, there was not a strong focus on technology in the publications we identified on SME development. More papers examined the use of technology, rather than the formation and development of technology-based firms. Around 10% of the papers we examined involved some discussion of the use of technology. Typically, these papers discussed the use of e-commerce, internet-based or mobile banking, or the use of information and communication technologies in marketing efforts. They, for instance, examined how ICT can change how women run their businesses or looked at the impact of digital literacy to encourage entrepreneurship. Judging from the literature in the dataset, widespread adoption of technology appears to be challenging for many entrepreneurs and SMEs in LDCs, particularly in rural areas.

Around 3% of the SME publications discussed technology more generally for SME development (as distinct from a focus on technology use). They, for example, looked at the role of technology infrastructure, such as education and outreach spaces for digital literacy, or telecentres, in developing entrepreneurship. Bangladesh and Tanzania were by far the most frequent focal countries for research on technical aspects of SME development. In Bangladesh, some of the papers were connected to research on the Union Digital Centres that have been set up in rural areas as a part of the Digital Bangladesh strategy to encourage e-government services and rural entrepreneurship. In Tanzania, there was a heavy emphasis on mobile financing, partly connected to the expansion of the M-Pesa service from Kenya to Tanzania.

Overall, then, there is a limited emphasis on technology in SME development publications. Many LDCs, including Bangladesh, Senegal, Cambodia, Rwanda, and Uganda have singled out digital technology as a priority and have set up initiatives to promote SME technological development. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 9, to promote industry, innovation, and infrastructure, includes the targets to enhance, in different ways, technologies in LDCs. Considering these initiatives, there is certainly scope to strengthen research on technology and SME development in LDCs.

4. Discussion

This paper has demonstrated that research on SME development and entrepreneurship concentrated on LDCs, is limited in most countries. A large proportion of the research is focused on only four LDCs. Many LDCs have little to no research focused on their SME development and are thus not able to harness evidence-based research to develop SME and innovation strategies. Considering the need of LDCs to promote innovation and the important potential contributions of their SME sector there is a demand for a much stronger emphasis on SME development in LDCs' research.

The research has also shown that while innovation is mentioned in a considerable number of abstracts on SME development in the LDCs, close scrutiny shows that most of the publications don't have any significant focus on innovation. The publications typically mention innovation in a general fashion. The ones that have a clear focus on innovation at times concentrate on more macro issues, such as identifying the main actors involved in innovation rather than understanding how innovation actually occurs in SMEs.

The SME development publications also have a very limited focus on R&D issues which reflects a weak focus on investigating research-based learning for innovation. According to Lundvall et al. (Citation2009), innovation is the result of a combination of science-based and experience-based learning. As a result, the limited focus on researching R&D would be detrimental to understanding innovation efforts in the LDCs that include a science-based component. However, others including Ernst, Mytelka, and Ganiatsos (Citation1998) and Kraemer-Mbula et al. (Citation2019) underplay the importance of R&D investment for SME innovation in sub-Saharan African countries and other low-and-middle income countries. If that is the case, the lack of research on SME development and R&D may therefore not have much detrimental effect on SME innovation in the LDCs. If R&D is not important for SME innovation, it does not matter much that it is not being studied. It would still be beneficial to conduct more research to confirm more widely the role R&D investment plays in SME innovation in LDCs.

When we widen the topics and look more carefully at informal learning for SME innovation and look at topics such as learning-on-the-job, learning-by-trial and error, linkages, interactions, networking, partnerships, and interactive learning, we only see pockets of research that loosely can connect to these topics in the SME development literature focused on the LDCs. As a result, we cannot identify much research that could inform efforts to stimulate SME innovation in the LDCs. As there are considerable efforts going on in the LDCs to promote SME development and innovation, this void of research on informal learning of SMEs implies that policies to support SMEs may not be grounded in the realities of the countries. Poole (Citation2018) argued that when a policy emphasis is made on an under researched field, there is a high risk that interest groups can hijack the agenda and direct governmental support to efforts that are not likely to lead to much SME innovation.

The analysis also indicated that there is limited emphasis on examining technology development in the SME papers. There are only a few publications discussing technology issues in the dataset and they mostly focus on the use of the technologies as opposed to their development. With the strong priority many LDCs have placed on promoting digital and other technologies there is a demand for research that informs those developments. Again, this void of research is likely to be detrimental to technological development in these countries and again poses a risk that interest groups will hijack the intended agendas of these policies.

A clear limitation of this research is that we may have overlooked research focused on SME development in the LDCs and thus there exists more research than we identified that is informing policies for SME innovation in the LDCs. This applies particularly to research published in the grey literature, i.e. reports and working papers and research written in other languages than English. Even though the databases we relied on identified publications not written in English, they may have missed several publications that rightly should have been in the dataset we analyzed. The coverages of the databases have, however, been improving in recent years, both in terms of including types of publications such as reports and working papers, and research written in more varied languages than English. Considering how extremely low the observed publication levels were, (with less than four publications on average per country at the end of the study period, and about half the 46 LDCs having less than 10 publications focused on their SME development for the whole 10-year period studied), we can be certain that there is a need for more research on SME development and innovation in the LDCs. The heavy emphasis on policies promoting SME development, innovation, and technologies in these countries, noted in the Introduction, underscores the need for this research.

An implication of this analysis is to point out the clear need for governmental agencies in the LDCs, along with international funders, to fund research that analyses SME development, technological development, and innovation in the LDCs to expand the stock of knowledge on SME development in these countries. Further research should, at a minimum, focus on the topics presented in , to cast a better light on SME innovation under the specific conditions in the LDCs. As previous research has indicated that capacity building may be a limiting factor for this research, those funders should consider including research training elements as part of their funding portfolios. With more locally grounded research, the evidence bases of policies and programmes promoting SME development can be strengthened in the LDCs to benefit both social and economic development in these countries and help them graduate to higher income rankings.

Acknowledgements

The team also acknowledges collaboration with the United Nations Technology Bank for Least Developed Countries. We want to thank two anonymous reviewers and an editor of Innovation and Development for constructive feedback. Any possible errors in this paper are solely those of the authors. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent views of IDRC, our funder, nor its Board of Governors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The authors agree to make data supporting the results or analyses presented in this paper available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abaho, E., D. B. Begumisa, F. Aikiriza, and I. Turyasingura. 2017. “Entrepreneurial Orientation Among Social Enterprises in Uganda.” Business Management Review 20 (2): 1–14.

- Abdulla, A. R., and M. M. Othman. 2011. “How SME Build up Core Competencies to Support Itself Grow Up: A Case Study to Tanzania Firm Kilombero Sugar Company Ltd (KSCL).” 2011 international conference on management and service science, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China, 2011, 1–4.

- Abubakar, Y. A., C. Hand, D. Smallbone, and G. Saridakis. 2019. “What Specific Modes of Internationalization Influence SME Innovation in Sub-Saharan Least Developed Countries (LDCs)?” Technovation 79:56–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2018.05.004.

- Acs, Z., and N. Virgill. 2010. “Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries.” In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction, edited by Z. J. Acs and D. B. Audretsch, 1-19. New York, NY: Springer.

- Alam, M. D. S. A., D. Wang, A. Waheed, M. S. Khan, and M. Farrukh. 2019. “Analysing the Impact of Agile Supply Chain on Firms’ Sales Performance with Moderating Effect of Technological-Integration.” International Journal of Applied Decision Sciences 12: 402. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJADS.2019.102629.

- Alqershi, N. A., Z. B. Abas, and S. Mohd Mokhtar. 2018. “Strategic Innovation as Driver for SME Performance in Yemen.” Journal of Technology and Operations Management 13 (1): 30–41. https://doi.org/10.32890/jtom2018.13.1.4.

- Amarante, V., V. Amarante, R. Burger, G. Chelwa, J. Cockburn, A. Kassouf, A. McKay, and J. Zurbigg. 2022. “Underrepresentation of Developing Country Researchers in Development Research.” Applied Economics Letters 29 (17): 1659–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1965528.

- António, M. M. L. 2015. “Orientação Empreendedora das MPME Angolanas: Evidencia Empírica do Municípo de Cazengo-Kwanza Norte (Angola).” Masters diss., Instituto Politécnico do Porto.

- Arafat, M. A., and E. Ahmed. 2013. “Managing Human Resources in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Developing Countries: A Research Agenda for Bangladesh SMEs.” International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research 55 (43): 215–217.

- Asamnew, D. K. 2012. “Internet Technology Use in The Value Chain of Ethiopian SMEs: The Benefits, Problems & Prospects.” Masters diss., Linköping University.

- Awuah, G. B., and M. Amal. 2011. “Impact of Globalization.” European Business Review 23 (1): 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555341111098026.

- Bayer, A., and C. E. Rose. 2016. “Diversity in the Economics Profession: A New Attack on an Old Problem.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (4): 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.4.221.

- Berrou, J.-P., and F. Combarnous. 2012. “The Personal Networks of Entrepreneurs in an Informal African Urban Economy: Does the ‘Strength of Ties’ Matter?” Review of Social Economy 70 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2011.577347.

- Bose, T. K. 2019. “Institutional Framework and Networking of Exporting Agricultural SMEs in Bangladesh.” Doctoral diss., University of Glasgow.

- Carlisle, S., M. Kunc, E. Jones, and S. Tiffin. 2013. “Supporting Innovation for Tourism Development Through Multi-Stakeholder Approaches: Experiences from Africa.” Tourism Management 35:59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.05.010.

- Das, B., X. F. Hui, and S. S. Jamal. 2017. “Venture Capital: Alternate Financing Mechanism To Support SMEs.” Conference proceedings of the 5th international symposium on project management, ISPM 2017.

- Dawson, L. 2011. “Business Plans Offer Sustainable Industry Guidance for Zambian Workers.” Working paper. Australia: University of Notre Dame.

- DFID. 2011. The Engine of Development: The Private Sector and Prosperity for Poor People. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67490/Private-sector-approach-paper-May2011.pdf.

- Dosi, G., and D. J. Teece. 1998. “Organizational Competencies and the Boundaries of the Firm.” In Markets and Organization, edited by R. Arena and C. Longhi, 281-302. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Dumalanède, C., and M. A. Payaud. 2018. “Reaching the Bottom of the Pyramid with a Social Enterprise Model: The Case of the NGO Entrepreneurs du Monde and its Social Enterprise Nafa Naana in Burkina Faso.” Global Business and Organizational Excellence 37:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21888.

- Ehst, M., S. Sak, M. M. E. Sanchez, and L. V. Nguyen. 2018. Entrepreneurial Cambodia: Cambodia Policy Note (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/603641543599469665/Entrepreneurial-Cambodia-Cambodia-Policy-Note.

- Ejiri, A. H., and H. G. Sol. 2012. “Decision Enhancement Services for Small and Medium Enterprise Start-Ups in Uganda.” 2012 45th Hawaii international conference on system sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 2012, 4830–4839.

- Eliccel, P. 2016. “La performance des entreprises et l’impact de l aculture nationale: Une illustration dans le context socio-économique haïtien.” Diss., Université. des Antilles.

- Elmansori, E. 2014. “Fostering Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Through Business Incubators in the Arab World.” Doctorial Diss., Erasmus University, ISS International Institute of Social Studies.

- Ernst, D., L. Mytelka, and T. Ganiatsos. 1998. “Technological Capabilities in the Context of Export-Led Growth: A Conceptual Framework.” In In Technologial Capabilities and Export Success in Asia, edited by D. Ernst, 4–45. London: Routledge.

- Evans, D., and C. Thomas . 2013. Network Science Center Research Team's Visit to Kampala, Uganda. United States Military Academy Network Science Center, Technical Report 13-007.

- Faroque, A. R. 2014. “Network Exploration and Exploitation in International Entrepreneurship: An Opportunity-Based View.” Diss., University of Canterbury.

- Faroque, A. R., S. C. Morrish, and A. S. Ferdous. 2017. “Networking, Business Process Innovativeness and Export Performance: The Case of South Asian Low-Tech Industry.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 32 (6): 864–875. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2015-0113.

- Ferreira, M. P., N. R. Reis, and R. Miranda. 2015. “Thirty Years of Entrepreneurship Research Published in Top Journals: Analysis of Citations, Co-Citations and Themes.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 5 (17): 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-015-0035-6.

- Friederici, N. 2018. “Grounding the Dream of African Innovation Hubs: Two Cases in Kigali.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 23 (2): 01850012. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946718500127.

- Gebremichael, B. A. 2014. “The Impact of Subsidy on the Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs).” Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 5:178–188.

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. 2019. SME Policy 2019. Ministry of Industries. http://bscic.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bscic.portal.gov.bd/page/7a956433_c02e_483d_9c17_db194d9f4a23/2020-01-01-19-01-8029ba8887b407ce0836783a9424a605.pdf.

- Habib, S. M. A., and P. Shah. 2010. “Economics of Integrating Access to Finance and Access to Information in Bangladesh Economy.” Banking & Finance Letters 2 (1): 241–248.

- Hailekiros, G. S., and H. Renyong. 2016. “The Effect of Organizational Learning Capability on Firm Performance: Mediated by Technological Innovation Capability.” European Journal of Business and Management 8 (30).

- Herderschee, J., K.-A. Kaiser, and D. M. Samba. 2011. “Resilience of an African Giant.” In Resilience of an African Giant, 75–99. World Bank Publications The World Bank Group, number 2359. https://doi.org/10.1596/9780821389096_CH05.

- Herrington, M., and A. Coduras. 2019. “The National Entrepreneurship Framework Conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Study of GEM Data/National Expert Surveys for South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Madagascar.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 9:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0183-1.

- IFC. 2014. Sub-Saharan Africa: SME Initiatives. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/region__ext_content/regions/sub-saharan+africa/advisory+services/sustainablebusiness/sme_initiatives.

- IFC. 2021. Small Business, big Growth: How Investing in SMEs Creates Jobs. International Finance Corporation. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099137208052240777/pdf/IDU0bc3323070be2e04f7e0b2af0cf89e317a2c4.pdf.

- Iftekhar, U. K., N. K. Imran, and N. H. Sadia. 2018. “Critical Success Factors of Tech-Based Disruptive Startup Ecosystem in Bangladesh.” Journal of Entrepreneurship & Management 7 (2): 7–27.

- IMF. 2022. Real GDP Growth: Annual Percent Change. International Monetary Fund. All Country Data. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCHWEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/BGD.

- Jiménez, A. 2019. “Inclusive Innovation from the Lenses of Situated Agency: Insights from Innovation Hubs in the UK and Zambia.” Innovation and Development 9 (1): 41–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2018.1445412.

- Kabanda, S., and I. Brown. 2017. “A Structuration Analysis of Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Adoption of E-Commerce: The Case of Tanzania.” Telematics and Informatics 34 (4): 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.01.002.

- Kaijage, E. S. 2010. “University – Industry Linkage in Tanzania and Its Impact on Smes’ Development.” Business Management Review 14 (1): 1–26.

- Kanyoma, K. E., F. W. Agbola, and R. Oloruntoba. 2018. “An Evaluation of Supply Chain Integration Across Multi-Tier Supply Chains of Manufacturing-Based SMEs in Malawi.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 29 (3): 1001–1024. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-10-2017-0277.

- Kavenuke, R., L. Mboma, and U. Mbamba. 2019. “The Influence of Network Configurations in Enhancing Smes’ Competitiveness: Evidences from Building Materials Retailers in Tanzania.” Business Management Review 22 (2): 87–99.

- Kazimoto, P. 2014. “Assessment of Challenges Facing Small and Medium Enterprises Towards International Marketing Standards: A Case Study of Arusha Region Tanzania.” International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences 4 (2): 303–311.

- Kibeshi, K., and I. Nsubili. 2019. “Strategic Entrepreneurship, Competitive Advantage, and SMEs’ Performance in the Welding Industry in Tanzania.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 9 (1): 1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40497-018-0125-3

- Kraemer-Mbula, E., E. Lorenz, L. Takala-Greenish, O. O. Jegede, T. Garba, M. Mutambala, and T. Esemu. 2019. “Are African Micro- and Small Enterprises Misunderstood Unpacking the Relationship Between Work Organisation, Capability Development and Innovation.” International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation and Development 11 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTLID.2019.097411.

- Krishnan, A. M. 2016. “Entrepreneurship and the Discovery and Exploitation of Business Opportunities.” In Tourism Management, Marketing, and Development, edited by M. M. Mariani, W. Czakon, D. Buhalis, and O. Vitouladiti, 59–86. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kyophilavong, P., B. Vanhnalat, and A. Phonvisay. 2017. “Lao SME Participation in Regional Economic Integration.” Southeast Asian Economies 34 (1): 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1355/ae34-1h.

- Lema, R., E. Kraemer-Mbula, and M. Rakas. 2021. “Innovation in Developing Countries: Examining Two Decades of Research.” Innovation and Development 11 (2-3): 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2021.1989647.

- Lingelbach, D., L. de la Vina, and P. Asel. 2005. “What’s Distinctive About Growth-Orientated Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries?” UTSE college of business centre for global entrepreneurship working paper No. 1. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.742605.

- Lingelbach, D., V. Sriram, T. Mersha, and K. Saffu. 2012. “Financial Innovation in Desperately Poor Economies: Some Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Proceedings of the international council for small business 2012 world conference, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Lundvall, B. Å., J. Vang, K. J. Joseph, and C. Chaminade. 2009. “Innovation System Research and Developing Countries.” In Handbook of Innovation Systems and Developing Countries, edited by BÅ Lundvall, K. J. Joseph, C. Chaminade, and J. Vang, 1–30. Northhampton: Edward Elgar.

- Mashimba, S. 2014. “Performance of Micro and Small-Scale Enterprises (MSEs) in Tanzania: Growth Hazards of Fruit and Vegetables Processing Vendors.” Journal of Applied Economics and Business Research 4 (2): 120–133.

- Matare, G. P., and T. N. Sreedhara. 2019. “Financial Management Practices and Growth of Micro, SMEs of Tanzania. Research Review.” International Journal of Multidisciplinary 4 (2): 967–972.

- Mayanja, S., J. M. Ntayi, J. C. Munene, J. R. K. Kagaari, and W. Balunywa. 2019b. “Ecologies of Innovation Among Small and Medium Enterprises in Uganda as a Mediator of Entrepreneurial Networking and Opportunity Exploitation.” Cogent Business & Management 6 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1641256.

- Mayanja, S. S., J. M. Ntayi, J. C. Munene, J. R. K. Kagaari, W. Balunywa, and L. Orobia. 2019a. “Positive Deviance, Ecologies of Innovation and Entrepreneurial Networking.” World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 15 (4): 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-12-2018-0110.

- McGraw, T. K. 2007. Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- McKenzie, D., and C. Woodruff. 2017. “Business Practices in Small Firms in Developing Countries.” Management Science 63 (9): 2967–2981. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2492.

- Meyer, M., D. Libaers, B. Thijs, K. Grant, W. Glänzel, and K. Debackere. 2012. “Origin and Emergence of Entrepreneurship as a Research Field.” Scientometrics 98 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1021-9.

- Moraa, H., and D. Gathege. 2013. “How ICT Hubs Models Have Impacted on the Technology Entrepreneurship Development.” Proceedings of the sixth international conference on information and communications technologies and development: notes – volume 2 (ICTD ‘13), 100–103. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Msanjila, S. S., and F. R. Kamuzora. 2010. The Role of ICTs on Enhancing Collaborative Capital in Developing Economies: A Case of SMEs and Non-State Actors in Tanzania. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Msanjila, S. S., and F. R. Kamuzora. 2012. “Collaborative Networks as a Mechanism for Strengthening Competitiveness: Small and Medium Enterprises and Non-State Actors in Tanzania as Cases.” Journal of Language, Technology & Entrepreneurship in Africa 3 (2): 68–81.

- Mudde, H., D. T. Gerba, and A. D. Chekol. 2015. “Entrepreneurship Education in Ethiopian Universities: Institutional Assessment.” Synthesis report, No 2015/01, working papers. Maastricht School of Management. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:msm:wpaper:2015/01.

- Mugambe, P. 2019. “Developing a Sustainable Financing Model for SMEs during the Organizational Life Cycle in Uganda.” Diss., North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus.

- Naidoo-Swettenham, T., and J. Miettinen. 2015. “Strategies Employed to Support Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Southern Africa.” Proceedings of the international conference on innovation & entrepreneurship.

- Nelson, R. R., and S. G. Winter. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Ng, W., and A. Rieple. 2014. “Special Issue on “The Role of Networks in Entrepreneurial Performance: New Answers to Old Questions?”, Special Issue Guest Editors’ Introduction.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 10 (3): 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0308-5.

- Ngwa, M., and K. Kabangu. 2016. “Developing Dynamic Capabilities in Emerging Markets : Comparative Multiple Case Studies of Cameroonian and Zambian SMEs.” Diss.

- Nour, S. 2011. “Assessment of Skill and Technology Indicators at the Macro-Micro Levels in Sudan.” MERIT Working Papers 2011-031. United Nations University – Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (MERIT).

- Obeysekare, E., K. Mehta, and C. Maitland. 2017. “Defining Success in a Developing Country's Innovation Ecosystem: The Case of Rwanda.” 2017 IEEE global humanitarian technology conference (GHTC). San Jose, CA, USA, 2017. 1–7.

- Paulo, K. M. S. 2017. “Modelo de Relacionamento Banca – PME: O Caso de Angola.” Master diss., University of Lisbon.

- Peša, I. 2018. “The Developmental Potential of Frugal Innovation among Mobile Money Agents in Kitwe, Zambia.” The European Journal of Development Research 30 (1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0114-3.

- Poole, D. L. 2018. “Entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship and SMEs in Developing Economies: How Subverting Terminology Sustains Flawed Policy.” World Development Perspectives 9:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2018.04.003.

- Qamruzzaman, M., and W. Jianguo. 2019. “SME Financing Innovation and SME Development in Bangladesh: An Application of ARDL.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 31 (6): 521–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1468975.

- Rand, J., P. C. Rodriguez, F. Tarp, N. Trifković, and team C. 2019. “Myanmar Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises 2018 Qualitative Study.” Central Statistical Organization, Ministry of Planning and Finance, UNU-WIDER, and University of Copenhagen. Central Statistical Organization, Ministry of Planning and Finance. UNU-WIDER, and University of Copenhagen.

- Republic of Rwanda. 2020. Entrepreneurship Development Policy: Developing an Effective Entrepreneurship and MSME Ecosystem in Rwanda. Ministry of Trade and Industry. https://www.minicom.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Minicom/Publications/Policies/Entrepreneurship_Development_Policy_-_EDP.pdf.

- Ritchie, H. A. 2013. “Negotiating Tradition, Power and Fragility in Afghanistan: Institutional Innovation and Change in Value Chain Development.” Diss.

- Rodrigues, E. 2021. Start-up Acts: An Emerging Instrument to Foster the Development of Innovative High-Growth Firms. ICReport in the Series on Innovative Finance. Investment Climate Reform Facility. https://www.icr-facility.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/icreport_startupacts.pdf.

- Rooks, G., A. Szirmai, and A. Sserwanga. 2012. “Network Structure and Innovative Performance of African Entrepreneurs: The Case of Uganda.” Journal of African Economies 21 (4): 609–636. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejs011.

- République du Sénégal. 2020. Loi Relative à la Création et à la Promotion de la Startup au Sénégal. Ministry of Digital Economy and Telecommunications. http://www.numerique.gouv.sn/mediatheque/documentation/loi-relative-%C3%A0-la-cr%C3%A9ation-et-%C3%A0-la-promotion-de-la-startup-au-s%C3%A9n%C3%A9gal.

- Rupakhetee, K. 2012. “Evaluation of Micro Credit Support in Enterprise Development for Poverty Reduction in Developing Countries; Evidence from Micro Level Data of Nepal.” Doctoral diss., Seoul National University.

- Sahibzada, I., and S. Foghani. 2014. “Role of Strategic Alliance as an Instrument for Rapid Growth, by the Afghan Firms.” Journal of Marketing and Consumer Research 5: 1–11.

- Sarker, S., and M. Palit. 2015. “Strategic Orientation and Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in Bangladesh.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 24 (4): 572–586. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2015.068643.

- Sawaya, A., and S. Bhero. 2017. “Large Enterprises Neglect Supporting SMEs in Mozambique.” Journal of Economics and Public Finance 4 (1): 77. https://doi.org/10.22158/jepf.v4n1p77.

- Scharff, C., F. Gandhi, D. Hoernes, S. D'Costa, M. Bejarano, A. Greenberg, F. Patino, et al. 2016. “AppDock: An Education and Outreach Space for Device Literacy.” ACM international conference proceeding series.

- Schmutzler, J., R. Pugh, and A. Tsvetkova. 2022. “Contextual and Evolutionary Perspectives on Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Insights from Chris Freeman’s Thinking.” Innovation and Development 12 (1): 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/2157930X.2021.1931742.

- Sheldon, P. J., and R. Daniele, eds. 2017. Social Entrepreneurship and Tourism: Philosophy and Practice. Cham: Springer.