Abstract

Luang Prabang Province's (LPP) forest cover was estimated at 24.2% (0.48 million ha) of the total land area in 1982. This decreased to 12.8% by the early 2000s and then sharply increased to 32.8% (0.65 million ha) in 2010, an annual increase of 2.8% (50,000 ha) from 2002 to 2010. This paper attempts to examine the factors influencing the increase of forest cover in LPP during the 2000s. The study analyzes the influence of local socioeconomic development on changes in forest cover based on forest transition theory (FTT). The study period is relatively short compared to historical studies of forest transition, which often extend over several decades. To overcome this limitation, Huaphanh Province, which showed a decrease in forest cover, was used as a control province for comparison. Secondary social and economic data from various sources were collected and analyzed using qualitative and comparative analysis. The results from this study indicate that the increase in forest cover is closely linked to socioeconomic development in the province. Increasing economic development and urbanization provided alternative employment opportunities for the rural population and led to decreases in both rural population and poverty. In addition, with improvement of infrastructure in rural areas, particularly roads and access to markets, rural households changed their agricultural practices from subsistence-oriented to market-oriented production. As a result, the rate of rural poverty continued to decline and areas of shifting cultivation and upland rice production decreased, which left the formerly cultivated land to fallow for a longer period, allowing the natural recovery of vegetation.

Introduction

According to the National Forest Resources Assessment (NFRA), Luang Prabang Province's (LPP) forest cover was estimated at 24.2% (0.48 million ha) of the total land area of the province in 1982, which was the lowest rate among all of the provinces in Lao People's Democratic Republic (PDR) (DoF Citation2005). This decreased to 22.2% by the early 1990s and to 12.8% (0.25 million ha) in 2002. In 2010, the forest cover sharply increased to 32.8% (0.65 million ha), an annual increase of 2.8% (50,000 ha) from 2002 to 2010. The increase was due to large unstocked forest being restored and becoming forest again when its canopy cover reached 20% and above (DoF Citation2005, Citation2012). However, there is no evidence that this assessment can explain the restoration of large areas of unstocked forests.

Poverty, particularly rural poverty, was the major cause of the rapid decline in forest cover, not only in LPP but also in Northern Laos in general. In the 1980s, about 250,000 families or 1.5 million people had been practicing slash-and-burn shifting cultivation. They were mostly very poor people with no alternative livelihood options. About 300,000 ha per year of forests were cleared for food production, particularly upland rice production (MAF Citation1989). In the 1990s and 2000s, in order to address the root causes of shifting cultivation, the government launched many development programs in the northern region, the main ones being: Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Program (SCSP); a National Growth and Poverty Alleviation Program (NGPAP); and Land Use Planning and Land Allocation (LUPLA). In 2004, the government endorsed the National Growth and Poverty Eradication Strategy (NGPES) up to the year 2020, which set development targets to eradicate shifting cultivation by 2010 and poverty by 2020. Although forest cover continued to decrease from 41.5% in 2002 to 40.3% in 2010 at national level, there was a net gain of forests in the northern region at an average of 0.7% annually from 2002 to 2010. This gain was most likely influenced by the decrease in both rural poverty and slash-and-burn shifting cultivation in the northern provinces (Kim and Alounsavath Citation2015). However, the driving force behind the increase in forest cover in the northern provinces is not yet clear.

There are a number of case studies on the increase in forest cover in different countries in Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The increase in forest cover in Europe and North America is related to economic development (Rudel et al. Citation2005). However, increase in forest cover in some Asian countries (China, India, Vietnam, Bhutan, and South Korea) depend not so much on the level of economic development but on social and political factors at work under their distinctive national circumstances and capacities (Bae et al. Citation2012). For instance, the forest cover in South Korea increased from 35% of the national land area in the mid-1950s to nearly 60% (5.9 million ha) by the mid 1970s. During this period, the GDP was estimated at US$79 per capita in 1960 and at US$1000 in 1977 (Bae et al. Citation2012, p. 204).

The objective of this study was to examine factors influencing the increase of forest cover in LPP during the 2000s based on forest transition theory (FTT). Our hypothesis is that the quantitative gain of forest cover in LPP is related to socioeconomic development of the province and follows the economic development path of FTT. Due to economic development and increasing urbanization, rural poverty decreased leading to a decreasing rate of slash-and-burn shifting cultivation and thus leaving fallow areas for a longer period. This subsequently led to natural recovery of the vegetation.

Theoretical background

Forest cover has been observed to change positively as economic development progresses. The change from shrinking to expanding forests has been defined as “forest transition” (Grainger Citation1995; Mather Citation1992). Based on a number of case studies in many countries, five pathways have been identified to explain changes in forest cover (Lambin and Meyfroidt Citation2010; Rudel et al. Citation2005).

Economic Development Path: This occurs when land pressure decreases as farmers leave the land and move to urban areas for better paying jobs. As a result, marginal lands become too expensive to manage as cost of labor increases due to labor scarcity; hence, land is eventually abandoned and reverts to forest (Rudel et al. Citation2005).

Forest Scarcity Path: Deforestation caused by agricultural expansion or wood production creates a scarcity of forest products and decreases the ability of forests to deliver ecosystems goods and services. The growing population and economic growth cause increases in the demand for forest products and forest services, which may reinforce this scarcity. The price of forest products increases and it becomes increasingly profitable to plant trees in plantations, woodlots, and gardens (Rudel et al. Citation2005). The economic response by landowners includes tree plantation development and more intensive forest management (Hyde et al. Citation1996).

State Forest Policy Path: This occurs when national forest policies change for reasons not directly linked to the forest sector, which include modernizing the economy, promoting eco-tourism or developing tree plantations, integrating marginal social groups such as ethnic minorities living in forests, and restricting wood extraction from natural forests via the creation of natural reserves or managed state forests. Policies restricting land use in forest zones can also contribute to forest protection and recovery.

Globalization Path: This is an expansion of the Economic Development Path when the global demand for tourism and conservation encourages more investment in forests, while the rural poor migrate outside their regions or countries, thus leaving marginal agricultural lands to forest. This pathway influences land use in developing countries and can result in international forest agreements or increased interest in rural forests (Lambin and Meyfroidt Citation2010).

Smallholder, Tree-based Land-use Intensification Path: This occurs with the innovative use of systems that incorporate greater tree cover including fruit orchards, woodlots, agroforestry systems, gardens, hedgerows, abandoned land, or fallows with secondary succession. In this case, reforestation can occur without land abandonment, as described in the Economic Development Path, but rather as a consequence of more sustainable farming practices. These changes in forest cover occur on a smaller scale and are the result of agricultural innovation rather than forest conservation as described in the Forest Scarcity Path (Lambin and Meyfroidt Citation2010).

Materials and methods

Study area and design

LPP is located in the center of the northern region of Laos lying between 19°10′–21°30′N and 101°40′–103°40′E. In 2005, the province had a total area of 2063 km2 with population density of 21.6 persons per km2. LPP borders Phongsaly Province to the north, Huaphan Province to the east, and Vientiane Province to the south. In 1995 Luang Prabang City was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO for its unique architectural, religious, and cultural heritage. The province is divided into 12 administrative districts and 785 villages. The population in 2013 was 432,267 inhabitants (male 49.9% and female 50.1%) with an average household size of 5.3 and population growth rate and density of 1.9% and 21.6 persons per km2, respectively (LSB Citation2005, Citation2014). The province receives an average annual rainfall of 1467 mm with mean maximum temperature and minimum temperature of 31.9 °C and 20.1 °C, respectively. The main occupation of the people is agriculture with 81.3% of households engaged in agricultural production (ACO Citation2012). Other occupations include government service and employment in non-governmental organizations and businesses.

The study period was from 2000 to 2010, corresponding to two NFCAs and two national agricultural censuses (1998/1999 and 2010/2011), which provided data on farm and non-farm households and on agricultural and forestry land uses. The study period is relatively short compared to previous studies of forest transition which often extended over several decades. To overcome this limitation, Huaphanh Province, which had a decrease in forest cover from 29% (0.49 million ha) of the total land area in 2002 to 24.7% (0.40 million ha) in 2010, was used as a control province for comparison. Both provinces have some similarities in terms of history of forest uses that had caused deforestation and forest degradation over past decades, and both have similar social, cultural, and economic characteristics, as well as agricultural and forest management practices. However, Huaphanh's population density was lower than LPP (17 persons per km2 in 2005).

Data collection and sources

Secondary social and economic data of LPP and Huaphanh Province were collected from various sources (see ). The social data focused on population growth and distribution between urban and rural areas including the number of poor people, while the economic data focused on economic growth of three sectors namely agriculture and forestry, industry, and services. These sectors are the main contributors to growth of GDP. In the agriculture and forestry sector, we critically examined annual upland rice and maize cultivation. These crops have been extensively cultivated over the last decade (ACO Citation2012) and have a significant impact on land use and forest cover change in most of the provinces in Northern Laos (Kaspar et al. Citation2012). Rural population data, including rural poverty data, were collected from the National Population Census, Lao Expenditure and Consumption Survey (LECS), and Provincial Statistics Centers of LPP and Huaphanh Province. LECS is the most comprehensive household survey in Lao PDR and forms the basis for official poverty estimates (MPI Citation2010). The main data sources on agriculture including farm households were the Agricultural Statistic Yearbook and the Agricultural Census of 1998/1999 and 2010/2011 published by the Department of Planning. Data on forestland allocation and tree plantations were collected from the Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office (PAFO) of LPP and Huaphanh Province, and the Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Office (SCSO). Other information including government reports on the implementation of national and provincial socioeconomic, rural development, and poverty eradication were also collected from various sources.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using qualitative and comparative analysis. The qualitative analysis was used to gain an in-depth understanding of underlying factors influencing the increase of forest cover in LPP, based on FTT. The comparative analysis was used to study whether the levels of data that have significant effect on increase in forest cover in LPP significantly differ from those of Huaphanh Province. If they do, this finding would strengthen the empirical evidence to support our hypothesis that increasing forest cover is linked to socioeconomic development. The following data were included (): GDP per capita; upland rice cultivation (% of total rice cultivation); rural poverty (% of total population); rural population (% of total population); land allocation (% of total households); tree plantation (ha); and maize cultivation (ha). The single factor analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to test the statistical difference of these data between Huaphanh and LPP. We used a significance level of 0.05 for the statistical analyses.

Table 1. List of data.

Results and discussion

Luang Prabang Province

Economic growth

Since 2000, LPP's economic development has been considerably higher than other provinces in Northern Laos. Its GDP grew at 7% per year from 2001 to 2005 and 9.4% per year from 2006 to 2010, with estimated GDP per capita rising from US$310 in 2000 to US$931 in 2010 (LPO Citation2005, Citation2010). The agriculture and forestry sector accounted for 45% of the provincial economy in 2000 but declined from 45.3% in 2000 to 43.6% in 2010; while the service sector share in GDP gradually increased from 29.2% in 2000 to 35% in 2010, the highest growth of all service sectors among all of the provinces in Northern Laos. The contribution of the industry sector in 2010 also slightly decreased compared to 2000. The service sector continues showing growth since UNESCO declared Luang Prabang City a World Heritage Site in 1995 as a result of its unique architectural, religious, and cultural heritage. Since then, Luang Prabang City has been transformed into an important natural, historic, and cultural tourism destination. The government has made a lot of effort to conserve this World Heritage Site and to improve facilities and infrastructure such as roads, airport, transportation, accommodation, food supply, cultural tourism sites, and tourist guide services to attract domestic and foreign tourists. The number of guesthouses and resorts increased by 310 (from 10 in 1996 to 320 in 2013), and the number of restaurants increased from 44 in 2002 to 283 in 2013 (LSB Citation2005, Citation2014). The number of foreign visitors continued to increase from 31,050 in 2000 to 135,000 in 2005 and 240,712 in 2009 (LPO Citation2005, Citation2010).

Rural–urban migration

As more job opportunities became available, the migration of rural populations into cities fuelled economic development and increasing urbanization. From 1997 to 2010, the urban population rose from 39,600 to 147,100 while the rural population decreased from nearly 89% of the total population in 1997 to 65% in 2010 (). Many case studies demonstrate that rural–urban migration has a positive impact on forests. In South Korea, massive rural–urban migration had a positive effect on forest regeneration, resulting in a decrease of firewood consumption and thus an increase in the average volume of growing stock after the 1970s (Bae et al. Citation2012). In the case of Southern Bolivia, out-migration ultimately led to the collapse of the traditional highland economy, but also boosted environmental recovery as a result of reduced pressure on forest resources and availability of non-natural resource-based income from migrant remittances (Preston et al. Citation1997).

Table 2. Trends in total and rural population in Luang Prabang Province from 1997 to 2010.

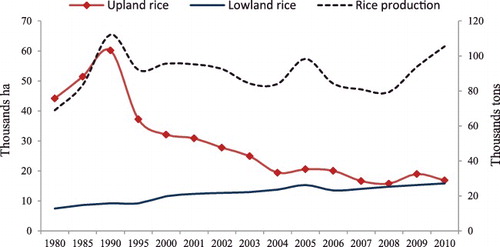

Upland rice and maize cultivation

Many crop varieties were cultivated between 1980 to 2010, but upland rice was the most dominant crop followed by lowland rice and maize with an average annual cultivation of 29,133, 12,439, and 9361 ha, respectively. The area of upland rice cultivation decreased by 70% from nearly 60,000 ha in 1990 to 16,000 ha in 2010 (). For upland rice cultivation, farmers mostly clear young and old fallow forestlands, and sometimes dense forests. This practice has been carried out for decades and has remained the predominant land use type not only in LPP but also in the uplands of northern Lao PDR. However, the areas of shifting cultivation in LPP decreased by 16.5% (330,000 ha) of the total area between 2000 and 2009 (Kaspar et al. Citation2012).

Further, from 2006 to 2010, nearly 2400 families changed their agricultural practices from upland rice production to commercial agricultural crop and livestock production, small business, and provision of other services (LPO Citation2005, Citation2010). Although, the total areas of rice production has decreased, total rice production has increased (DOP Citation2006, Citation2011, Citation2014). This increase could be a result of the productivity of lowland rice which increased by 1.2 tons per ha from 2000 (3.4 tons per ha) to 2010 (4.6 tons per ha).

Rural poverty reduction

In the 1990s, the government launched the NGPAP, which initially made slow progress with the poverty rate decreasing by 3.3% from 43.3% in 1993 to 40% in 2002. In the 2000s, the government implemented large infrastructure development projects for rural development and poverty eradication with a special focus on four sectors: (i) roads construction aligned with electricity, tap water supply, and other communication facilities; (ii) agriculture and forestry, focusing on commercial crops and livestock production; (iii) education; and (iv) health. From 1997 to 2008, the number of rural households with road access increased almost three times from 23.3% (12,979 households) of total rural households to 70.4% (38,000 households). From 2003 to 2007, the poverty rate rapidly decreased by nearly 50% from 40% in 2002 to 27% in 2008. Analysis of the relationship between poverty incidence and rural road development in Laos reveals that improved road access alone in rural areas attributed to about 13% of the decline in rural poverty between 1997 and 2003 (Peter Citation2005).

Another important factor that contributed to the decline in rural poverty was a major shift from subsistence to market-oriented agriculture. In 2010, LPP, compared to the other provinces in Northern Laos, had the second highest sale of farm produce. This was estimated at 45% of all farm produce on the market produced by households (ACO Citation2012). Between 2006 and 2010, over 7000 tons of maize, Job's tear, and sesame were exported mainly to Thailand, China, and Vietnam. More than 8500 buffalo, cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep were also exported (LPO Citation2005, Citation2010).

Forestland allocation

Forestland allocation to individual families was one of several Lao government tools to enforce policy issues, such as the eradication or stabilization of slash-and-burn shifting cultivation. From 1995 to 2005, nearly 80% of total villages in LPP completed land allocation and 65% of all families received land use certificates. Most of the forestlands allocated were classed within protected categories (conservation, protection, and regeneration). Based on the Forest Law including forestland allocation agreements on protection and utilization, these forest categories should lead to both recovery of forest vegetation and increased quantities of forest resources (GOL Citation2005). In Vietnam, natural forest regrowth was significantly associated with the area of forestry land allocated to households in 1994, and also the significant negative correlation with forestland allocation and rate of increase in mountain maize (Meyfroidt and Lambin Citation2008).

Tree plantation

Teak (Tectona grandis) and rubber (Hevea brasilliensis) plantations also contributed to increase in forest cover as well as households’ income. The total area of teak and rubber plantations in LPP are 25,440 ha and 13,500 ha, respectively (LPO Citation2005, Citation2010). Most of the teak and rubber plantations belong to farmers and the private sector. Harvesting of teak generally begins in year 12 when trees reach a merchantable size of 15 cm diameter at breast height (DBH). Most growers coordinate harvest with household needs for finance, and harvest levels of teak are steadily increasing as the resource matures. In 2006, it was estimated that over 7000 m3 of teak plantation was harvested and 20,000 m3 in 2010 (Midgly et al. Citation2011).

Huaphanh Province

Between 2000 and 2010, the estimated GDP per capita in Huaphanh rose from US$180 in 2000 to US$388 in 2010, which was the lowest growth compared with other provinces in Northern Laos. Agriculture comprised 65% of the provincial economy but slightly declined from 70.6% in 2001 to 64.6% in 2010, while the share of the services sector in GDP gradually increased from 14.3% in 2002 to 20.4% in 2010. The rural population increased slightly, but the high poverty rate in rural areas began to slowly decrease. Between 1997 and 2010, the poverty rate decreased from 71% in 1997 to 50% in 2010, with 93% of the poor in 2010 in rural areas. With increasing demand for agricultural products, particularly maize, farm households increased to 92% of which nearly 80% were subsistence farmers. Implementation of the land use planning and land allocation program was very slow, only about 20% of villages completed the land allocation process and only about 32% of families received land use certificates. The area of upland rice cultivation has continued to increase with increasing maize cultivation to meet market demands from neighboring countries, especially Vietnam.

shows the results of one-way ANOVA of seven data categories between Huaphanh and LPP; only maize was not significantly different. The results suggest that economic growth, rural population, rural poverty, and tree plantation development have a significant influence on the increases in forest cover in LPP. The decrease of forest cover in Huaphanh Province appears to depend on the level of socioeconomic development of the province, particularly slow economic growth and slow reduction in rural poverty. The proportion of poor people to total rural population was very high and implementation of the land use planning and land allocation program was very slow. Consequently, the area of shifting cultivation and upland rice production continued to increase, with forest clearances leading to decreases in forest cover.

Table 3. Results of one-way ANOVA of mean value (± standard deviation) of seven data categories between Huaphanh Province and Luang Prabang Province.

Conclusions

The results suggest that shifting cultivation particularly upland rice cultivation, reduction of rural population and poverty, and tree plantation development were the main factors influencing the increase of forest cover in LPP. Determining which pathway has led to forest transition in LPP therefore depends on determining what factors have caused the reductions in rural poverty and population in the province, which in turn led to the reduction in shifting cultivation, particularly upland rice cultivation, and the consequent reversion of fallow land back to forest. The trends during the study period of the share of agriculture and forestry, industry, and services in the GDP of the province showed agriculture and forestry, and (at a lower rate) industry decreasing, while services showed an increasing share of GDP. This finding, coupled with the finding that more and more farm households are changing their agricultural practices from subsistence production to market-oriented production, supports our hypothesis that the change in forest cover in LPP is related to socioeconomic development in the province.

It cannot be concluded, however, that only the Economic Development Path to forest transition has been taken in LPP. The findings have also indicated other pathways to forest transition. Tree plantation development and rural development are supported by government policy and provision of incentives. These indicate that the Smallholder, Tree-based Land-use Intensification Path and the State Forest Policy Path are also important pathways that have led to forest cover increase in LPP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Reference

- Agriculture Census Office (ACO). 2012. Report on Lao census of agriculture 2010/2011. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: Agriculture Census Office.

- Bae JS, Joo RW, Kim YS. 2012. Forest transition in South Korea: reality, path and drivers. Land Use Policy. 29:198–207.

- Department of Forestry (DoF). 2005. Report on the assessment of forest cover and land use during 1992–2002. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: Department of Forestry.

- Department of Forestry (DoF). 2012. Report on the assessment of forest cover and land use during 1992–2010. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: Department of Forestry.

- Department of Planning (DOP). 2006, 2011, 2014. Agriculture statistic 1976–2013. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: Department of Planning.

- Government of Lao PDR (GOL). 2005. Forestry strategy to the year 2020 of the Lao PDR. Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR: Department of Forestry.

- Grainger A. 1995. The forest transition. Area. 27:242–251.

- Hyde WF, Amacher GS, Magrath W. 1996. Deforestation and forest land use: theory, evidence, and policy implications. World Bank Res Observer. 11:223–248.

- Kaspar H, Cornelia H, Andreas H, Peter M, Urs W. 2012. Dynamics of shifting cultivation landscapes in northern Lao PDR between 2000 and 2009 based on an analysis of MODIS time series and Landsat images. Mum Ecol. 41:21–36.

- Kim SB, Alounsavath O. 2015. Forest policy measures influence on the increase of forest cover in northern Laos. Forest Sci Technol. 1–6.

- Lambin EF, Meyfroidt P. 2010. Land use transitions: socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy. 27:108–118.

- Lao Statistic Bureau (LSB). 1997. Country report on population census 1995. Vientiane Capital: National Statistic Bureau.

- Lao Statistic Bureau (LSB). 2005. Country report on population census 1995 and 2005. Vientiane Capital: National Statistic Bureau.

- Lao Statistic Bureau (LSB). 2011. Statistic year book 2010. Vientiane Capital: National Statistic Bureau.

- Lao Statistic Bureau (LSB). 2005, 2014. Statistic year book 2005, 2013. Vientiane Capital: National Statistic Bureau.

- Luang Prabang Provincial Office (LPO). 2005, 2010. The sixth and seventh five-year plan on socio-economic development (2006–2010; 2011–2015). Luang Prabang: Luang Prabang Provincial Office (in Laos).

- Mather A. 1992. The forest transition: the inter-relationship of afforestation and agriculture in Scotland. Area. 24:367–379.

- Meyfroidt P, Lambin EF. 2008. The causes of the reforestation in Vietnam. Land Use Policy. 25:182–197.

- Midgly S, Bennett J, Samonty X, Stevens P, Mounlamai K, Midgly D, Brown A. 2011. Scoping study: payments for environmental services and planted log value chains in Laos. Canberra.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). 1989. Report on forest resources development to the 1st National Forestry Conference. Vientiane Capital: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (in Laos).

- Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI). 2010. Poverty in Lao PDR 2008: Lao expenditure and consumption survey 1992/03–2007/08. Vientiane Capital: Ministry of Planning and Investment.

- Peter W. 2005. Road development and poverty reduction: the case of Lao PDR. ADB Institute Research Paper Series No. 64.

- Preston D, Mackline M, Warburton J. 1997. Fewer people, less erosion: the twentieth century in Southern Bolivia. Geogra J. 163:198–205.

- Rudel TK, Coomes OT, Moran E, Achard F, Angelsen A, Xu J, Lambin E. 2005. Forest transitions: towards a global understanding of land use change. Global Environ Change. 15:23–31.