ABSTRACT

This study examines the level of forest users’ participation at different stages of a participatory forest management (PFM) program, and identifies factors that influence their level of participation in the Gebradima forest, southwest Ethiopia. Data were collected from five forest user groups (FUGs) through household surveys, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions. A participation index (PI) and binary logistic regression model were used to analyze the data. Results revealed that the level of the forest users’ PI was 65.7%, 59%, and 54.9% at the planning, implementation, and monitoring stages, respectively. The logistic regression model showed that gender, family size, education level, income from the forest, distance of the forest from home, restriction on charcoal and timber harvesting, elite domination in decision-making processes, and lack of incentives were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) predictors for the level of participation. Thus, this study suggests that policy-makers and project designers should consider these factors in making future PFM implementation strategies to improve the level of forest users’ participation in forest management activities.

Introduction

Over the last two decades community participation in the management of government-owned forests has become a theme of policy and academic work in attempts to enhance sustainable forest management in many developing countries (Chirenje et al. Citation2013). This has shifted the emphasis from central decision-making to local decision-making, in which local communities participate in conserving and managing their forests (Islam et al. Citation2015).

This policy shift comes from the recognition of the failure of top-down state forest policies to ensure sustainable management and equitable access to forest resources (Tesfaye et al. Citation2012). The aim is now to develop joint management between local communities and government agencies to conserve forest resources on the basis of trust and friendship (Islam et al. Citation2015). This is necessary to achieve both long-term development and sustainability of the forest resources (Maier et al. Citation2014).This change results from international pressure such as Agenda 21 of the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil in 1992 and the 2003 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, which have given impetus to the role of local communities in sustainable management of forest resources (Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007; Shrestha and McManus Citation2008). It is now generally agreed that local communities should participate in forest management decision-making (Agrawal and Gupta Citation2005; Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007).

A fundamental assumption is that individual forest users may collaborate to manage and use the resources in a sustainable way if they are given the opportunity to participate in decision-making about forest resource management (Shrestha and McManus Citation2008). Similarly, decentralization theory suggests that local decision-makers may make better decisions than centralized authorities. This is because local people have site-specific forest knowledge and do not represent high administration costs (Tacconi Citation2007). It is also believed that locally-made decisions through local participation will enjoy greater acceptance, and thus facilitate policy implementation in forest resource management (Maier et al. Citation2014). In the context of environmental policy, participation is assumed to produce improved environmental conditions and easier implementation of the decisions compared to traditional, less inclusive modes of decision-making (Newig and Fritsch Citation2009). In top-down forest management, decisions are made at the central-state level with users excluded from the decision-making process and regulations are imposed in an exercise of top-down authority (Mbatu Citation2009; Chhetri et al. Citation2013), in contrast with bottom-up management (Mbatu Citation2009).

Accordingly, many developing countries have revised their forest policies, and institutionalized participatory forest management (PFM) approaches in their policy directives (Eilola et al. Citation2015). For instance, many African and South Asian countries have integrated local communities’ participation in the management of natural resources through a PFM approach (Schreckenberg et al. Citation2006). In Ethiopia, PFM programs have been implemented through community participation since the 1990s (Ameha et al. Citation2014). The PFM scheme at Gebradima forest, southwestern Ethiopia is one recent example.

PFM is an approach to forest management where local government authorities and communities living closest to forests work together to make decisions in all forest management matters, from co-managing resources to formulating and implementing institutional arrangements (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO] Citation2012). “Participation” has variable meanings (Chowdhury Citation2004). Some have explained the notion of participation with the concept of influence (Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007). Others have argued that participation means empowering local communities (Eilola et al. Citation2015). According to FAO (Citation2012), participation is a process in which stakeholders influence policy formulation, investment choices, share control over development initiatives and management decisions, and establish the necessary sense of ownership among local communities. Likewise, Reed et al. (Citation2009) defined participation as the involvement of non-conventional stakeholders, along with conventional stakeholders, in planning, implementing, and evaluating actions.

In this study, “participation” refers to active involvement of the forest user group (FUG) members in the forest management decision-making process at each stage of PFM program development. The term “FUG” means individuals who live in and around the forests, and who organize themselves to manage the forests collectively through formal agreement with the forest department. Several studies have shown that community participation in decision-making and developmental activities occurs at different stages of the project cycle (Sharma et al. Citation2011; Bagdi and Kurothe Citation2014; Obadire et al. Citation2014).

For instance, “participatory forestry planning” involves the beneficiary in decision-making in delineating the forest boundary to be managed, forest resources analysis, identification of users, preparing a forest management action plan, agreeing on responsibilities for implementation, assigning roles and responsibilities to the parties, and developing subsidiary bylaws that govern the activities (i.e. planning stage) (Chowdhury Citation2004), bringing the beneficiary into the community development and forest management activities (i.e. implementation stage) (Reed et al. (Citation2009), and into examining the whole process (i.e. monitoring stage) (Islam et al. Citation2013).

Several studies emphasize the importance of community participation in sustainable forest management (Chirenje et al. Citation2013). It is clear that the involvement of local communities in forest governance helps to ensure the sustainability of a project, increases acceptance, makes environmental policy more cost efficient and effective (Ferranti et al. Citation2010; Maier et al. Citation2014), reduces conflicts with local authorities and promotes better governance (Newig and Fritsch Citation2009), builds trust between community and forest department, and develops a sense of responsible ownership (Agrawal and Gupta Citation2005).

A number of studies have shown that environmental management initiatives that exclude affected parties from decision-making have proven to be unsustainable (Agrawal and Chhatre Citation2006; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Ferranti et al. Citation2010). There is, however, some doubt about the extent to which the development project interventions involved the beneficiaries at various stages of natural resource management decision-making processes, and the available evidence is limited (Maier et al. Citation2014).

A better understanding of factors influencing individual participation in community forestry activities is crucial because community forestry aims to promote both forest conservation and livelihood improvements (Chhetri et al. Citation2013). Thus, several previous studies have shown that numerous factors have influenced the degree of household participation in forest management. For instance, Agrawal and Chhatre (Citation2006) have classified these as demographic, socioeconomic, biophysical variables, and other institutional related factors. Most studies have focused upon demographic and socioeconomic factors affecting community participation in forestry management activities (Degeti Citation2003; Salam et al. Citation2005; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Getacher and Tafere Citation2013), rather than institutional factors. Chhetri et al. (Citation2013) suggest that factors leading to low levels of community participation in developmental projects should be explored.

Although participation in forest policy and management has gained popularity in Ethiopia since the 1990s, the extent to which PFM has been successful in securing forest users’ participation during the planning, implementation, and monitoring phases has not been much investigated. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to examine the level of forest users’ involvement at the three stages of a PFM program (i.e. planning, implementation, and monitoring), and identify factors influencing their level of participation in the program. This study contributes to the growing PFM literature through testing the common assumption that bottom-up conservation approaches encourage higher levels of local community participation than top-down conservation approaches.

Methodology

Study area

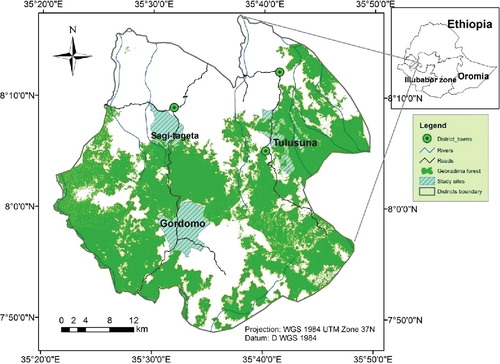

This research was conducted in five FUGS across three PFM rural kebeles (the lowest administrative units in Ethiopia), where Gebradima forest is located (7°48′–8°17′N, 35°21′–35°49′E) (). The forest covers three districts of Illubabor administrative zone of Oromia regional state, southwest highlands of Ethiopia. The altitude of the forest area ranges from 1444 to 2444 m above sea level. More than 90% of the land area belongs to the woina-dega (subtropical) agro-climatic zone. In the study area, different landforms such as rugged mountains, deep gorges, and extensive dissected plateaus are the main topographic features. According to the Central Statistical Agency (CSA Citation2013), the total population of the three districts is 155,136, out of which 77,180 are males and 77,956 females, with a population density of 88 persons/km2.

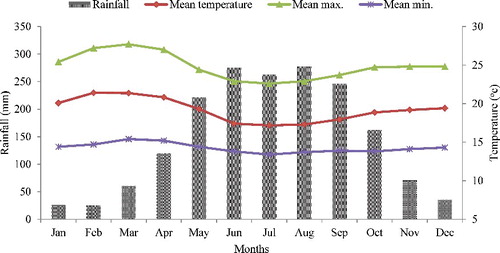

According to 16 years’ climate data of the Ethiopian National Meteorological Agency (NMA) from 2000–2015, the climate of the study area is moist subtropical with a mean annual temperature of 19.18 °C and mean annual rainfall of 1782.76 mm (NMA Citation2016). About 91.23% of the total annual rainfall occurs between March and October, with the highest amount in August. The rainfall pattern is unimodal, with little rainfall in January and February, gradually increasing to a peak between June and August, and decreasing in November and December (). The hottest months are from January to April, with maximum temperature in March (27.7 °C), and the coldest months are from June to December, with minimum temperature in July (13.4 °C).

Figure 2. Mean, maximum, and minimum monthly temperature and rainfall (NMA Citation2016).

The vegetation of the study area is characterized by tropical montane evergreen rainforest with the dominant tree species including Albizia gummifera, Millittia ferruginea, Pouteria adolfi-friederici, Schefflera abyssinica, Sapim ellipticum, Ficus sur, and Croton macrostachyus (Tadesse et al. Citation2016). The soils of the study area consist of dystric nitisols (red-basaltic soil), cambisols, dystric gleysols, gypsic yermosols, and orthic solonchaks (FAO Citation1990). The main sources of household income in the study area are crop cultivation, livestock rearing, and extraction of various forest products particularly forest coffee, honey, and spices. The principal crops are maize (Zea mays) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), mainly for subsistence needs. Vegetables and a variety of fruits are also cultivated by local farmers in the study area.

Description of the program

Gebradima forest is one of the 58 National Forest Priority Areas of Ethiopia. Local communities at Gebradima forest had organized themselves as FUGs and signed an agreement with the district forest enterprise office to manage, protect, and use the forest resources. According to the records available in the district forest enterprise office, a total of 13 FUGs were established during the fiscal year of 2010 to June 2015, with the help of FARM-Africa, an international British based non-governmental organization. FUGs began managing a total area of 29,901.61 ha of the natural forest, and about 2182 households participated as of December 2015. The specific objectives of this program are: (i) to manage the forest in a sustainable way by participating local communities who live in and around the forest through development of a new institution (i.e. FUGs); (ii) to strengthen the institutional capacity of the forest department; and (iii) to increase the value generated from forest products towards sustainable rural development (FARM-Africa Citation2014).

Sample design and data collection

This study used a two-stage random sampling technique to select FUGs and household heads. In the first stage of the sampling procedure, five FUGs were randomly selected out of the total 13 FUGs that were formed under PFM program arrangements in the study area. In the second stage, using a list of households in each FUG from the district forest enterprise office, sample size was determined through probability proportional to size sampling technique. Accordingly, a total of 172 households (20% of the study population) were selected for the study. Household heads for the questionnaire survey were randomly selected from each FUG and a lottery method was used for all of these random selections. The respective sample size for each FUG was calculated (see ).

Table 1. Distribution of sample size of households from each selected FUGs.

The data required for this research were generated through a structured questionnaire, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews, which were undertaken from January to March 2016. The survey questionnaires had three sections. The first section collected household characteristics such as demographic information (age, gender, marital status, and family size), socioeconomic information (education level, forest income, landholding size, livestock ownership, and occupation) and biophysical information (distance from the forest and market).

The second part contained 21 participation indicators designed to assess a forest user's level of participation in a PFM program at different stages. Accordingly, eight indicators were used for the planning stage, eight for the implementation stage, and five for the monitoring stage. Participation indicators were identified through literature reviews and discussion with district forest experts. These indicators were rated on a three-point continuum with 1 = low, 2 = medium, and 3 = high. The third section included six items to assess institutional related factors that affect participation levels with 1 = yes and 0 = no. The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into Afaan Oromo, the local language, in order to make it understandable to both enumerators and respondents. Finally, the pre-tested questionnaires were administered to the sampled household heads through trained enumerators. The enumerators were supervised by the lead author of this research throughout the field data collection period.

In addition to the quantitative household survey, key informant interviews and focus group discussions were conducted to obtain qualitative information. To obtain accurate information, the focus group discussions were held with a few knowledgeable FUG members who could provide reliable information. The key informants included FUG members, FUG leaders, forest managers, and forest experts. Accordingly, a total of three focus group discussions, each with eight participants, were undertaken in each of the three PFM rural kebele administrative offices. During these discussions, participants were asked about their membership in FUGs organized for carrying out forest management, level of FUG participation in the PFM program, and factors that influence their levels of participation in the program. The data generated during interviews and focus group discussions were used to consolidate and triangulate the data obtained through the household survey.

Statistical data analysis

The data generated by the structured questionnaire were organized and entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v20 for analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) were used to summarize the profile of the respondents. The binary logistic regression model was employed to identify significant factors that influenced the level of participation. To determine the level of a forest user's participation at each stage of the PFM program (i.e. planning, implementation, monitoring), a participation index (PI) was used following a modified formula (Sharma et al. Citation2011; Bagdi and Kurothe Citation2014; Obadire et al. Citation2014):(1) where PIi is participation index for ith respondent; Yij is the score of jth item for ith respondent; K is the maximum participation score:

(2) where PI is participation index for PFM program; PIi is participation index for ith respondent; N is the total number of respondents.

The overall PI was created by adding values of participation at the three stages. Categorization of PI value calculated in a particular PFM program can also be categorized into three categories as suggested by Bagdi and Kurothe (Citation2014), based on the normal distribution curve values as given in . The mean and standard deviation (SD) of marks were used to separate participants into low, moderate, and high levels of participation.

Table 2. Categorization of people's participation according to normal distribution curve values.

Variables and model specification

In order to identify factors that influence the level of a forest user's participation in the PFM program, the binary logistic regression model was employed. When the response variable is binary, the logistic regression model enabled assessment of the association between an independent variable and the response variable (Manor et al. Citation2000; Greene Citation2008). Thus, for the logistic regression model requirement, the overall participation score was dichotomized into a dummy variable by using the mean score of participation. This categorization does not affect the size and significance of main effects, types of association, and interactive effects (Manor et al. Citation2000; Greene Citation2008).

The response is a binary variable. Active participation equals 1 (if respondents scored higher than or equal to the mean participation score) and less participation equals 0 (if respondents scored less than the mean participation score). Let Yi represent a dichotomous variable that equals l if the respondent has actively participated in the program, otherwise 0. The probability of a forest user expressing active participation in the PFM program Pr (Yi = 1) is a cumulative density function/(likelihood function) evaluated at Xiβ, where Xi is a set of explanatory variables and β is parameters to be estimated. This kind of cumulative density function can be modelled using a logistic probability function which has the following form (Greene Citation2008; Getacher and Tafere Citation2013):(3) The estimation form of this logistic transformation of the probability that a respondent will express active participation, Pr (Yi = 1) is represented as (Greene Citation2008; Getacher and Tafere Citation2013):

(4) where Pr denotes the probability that the ith respondent had for active participation; Xi is a vector of explanatory variables; β is parameters to be estimated.The dependent variable of this study is the level of a forest user's participation in the PFM program, which coded as 1 if the respondent had actively participated in the program and 0 otherwise. Explanatory variables selected for the study were grouped into four different categories: demographic variables (age, gender, and family size); socioeconomic variables (education level, forest income, landholding size, livestock ownership); biophysical variables (distance from the forest and market); and institutional related factors (low level of awareness about the project and its benefits, restriction on charcoal and timber harvesting, lack of sense of ownership, lack of forest committee accountability, elite domination in decision-making processes, and lack of incentives) that affect their level of participation. The selection of explanatory variables used in the model were based on available data at hand that were expected to influence the level of participation in the study area, and on empirical literature dealing with participation in PFM. shows the hypothesized explanatory variables used in the logistic model and their direction of association with response variables. These factors were included in the logistic regression model as independent variables as follows:

(5)

Table 3. Explanatory variables included in the logistic regression model EquationEquation (5)(5) .

Results and discussion

General survey of the respondents

presents the general characteristics of the respondents. Of the total household respondents (172), 80.8% were male and the remaining 19.2% were female. Even though the PFM approach encourages women's participation, most of the female-headed households were not members of the PFM program owing to their double burden of work and cultural barriers. The marital status of the respondents at the time of the survey showed 93.6% were married and the remaining 6.4% were single. With respect to educational level, most of the respondents (65%) had no formal education, and 35% had acquired some level of formal school education. The Oromo ethnic group comprised the largest proportion (91.9%) of the total households sampled.

Table 4. General characteristics of the surveyed households (N = 172).

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for the vast majority (98.8%) of households, indicating that most of the sampled households are engaged in mixed farming. The average age of the sample household head was 43.6 years. This average conceals differences in age among sample household heads, which ranged from 20 years to 70 years, in which the majority (70.3%) belong in the 31–55 year age category. The average household family size was 6.1, which was larger than the regional mean family size of 5.4 (CSA Citation2016). The average livestock holding per household was about 5.8 tropical livestock units (TLU). On average the respondents possessed 1.92 ha of land, which is higher than the national household average land holding size of 1 ha (CSA Citation2016). The size of the land owned by respondents varied from a minimum of 0.25 ha to a maximum of 4 ha. The average annual income from the forest was 5948 Ethiopian Birr (1.0 US$ was approximately 22.0 Ethiopian Birr at the time of the study).

Forest users’ participation in the PFM planning stage

presents the level of forest users’ participation during the planning stage of the PFM program. Results of PIs showed that there is a wide variation among measured indicators of participation from a low (40.7%) in developing forest management bylaws that define the activities of FUG institutions to high (82.6%) in delineating the forest boundary to be managed. Thus, the formulation of some existing bylaws and their approval did not fully involve FUG members. The results from interviews and focus group discussions confirmed that some of the rules relating to forest management were set by forest authorities. This result supports the findings of Ameha et al. (Citation2014) who reported that the subsidiary bylaws of FUGs were formulated at the time a PFM was established, with little input from the FUG members across five PFM pilot sites in Ethiopia.

Table 5. Results of forest users’ participation in the planning stage of the PFM program.

Failure to involve all possible stakeholders in the process of bylaw formulation would render most bylaws ineffective (Mowo et al. Citation2016). For instance, a study conducted by Sanginga et al. (Citation2004) in southwestern Uganda reported that limited involvement of local communities in natural resource management policy development and the formulation of bylaws were major factors responsible for the increasing degradation of natural resources.

Forest users’ PI was calculated to be 65.7% in the planning stage of the PFM program (). Thus, forest users exhibited a moderate level of participation during the planning stage of the program. This implies that many of the working plans of this project originated from a bottom-up approach. As one participant said: “Before PFM implementation local communities were considered as destroyers of the forest, but PFM recognized us as sound forest managers.” In line with this, Degeti (Citation2003) argued that providing decision-making rights is the key to mobilizing people's participation in natural resource conservation. This finding is, however, not in line with Islam et al. (Citation2013) who reported that local people were less involved with forestry project planning in Bangladesh, as forest department officers had always played the dominant role and controlled the whole decision-making process. According to these authors, the greatest challenge to effective participation is usually the forest department officials’ decision-making behavior, which tends to inhibit a participatory forest management approach.

Similarly, Husseini et al. (Citation2016) reported that most households did not participate in forest reserve management in the northern region of Ghana. There, the main reason for non-participation by local communities was a lack of invitation to participate in any decision-making processes, and lack of awareness about the benefits of forest reserve management. These authors concluded that the top-down approach of the authorities was likely to thwart collaborative forest management efforts.

Forest users’ participation in the PFM implementation stage

shows the involvement of forest users in implementation activities of the project. The PIs during the project implementation stage ranged from 39.7% to 74%. Respondents showed a high level of participation in knowledge and skill development training (74%) provided by the project to build the capacities of the FUGs for managing forest resources. This was followed by nursery establishment (69.2%), which was developed by the project as an alternative income generation activity. Active involvement of FUG members in nursery establishments was also observed during the fieldwork when the project supported communities by providing materials and seedlings.

Table 6. Results of forest users’ participation in the implementation stage of the PFM program.

In contrast, a low level of participation (39.7%) was observed in forest fire fighting. The possible reasons explained by the participants during focus group discussions was that fire incidents had never been a problem, as the PFM was demarcated and the expansion of agriculture beyond the forest boundary was prohibited. Furthermore, one respondent noted that, “forest fire incidents were common before the commencement of the PFM project; but they were minimized after PFM.” Overall, the average PI calculated at the implementation stage of the program was 59%, a moderate level. This indicates that the project had involved forest users in project implementation activities. For instance, interviews and focus group discussions revealed that most of the forest users participated in planting new trees because of various seedlings provided by the project. As one participant said, “unlike the centralized approach, PFM encourages forest users to participate in the tree planting and management.” This finding is similar to that of Maraga et al. (Citation2011) who reported high community participation in afforestation project activities (i.e. tree nursery and woodlot establishment) in the River Nyando basin, Kenya.

Forest users’ participation in the PFM monitoring stage

shows the forest users’ level of participation in the monitoring stage of the program. The level was found to be high in some project activities and low in others. For instance, the PI was high in forest patrols (69.4%) and low in follow-ups of forest management bylaws (38%). This low level of participation could be attributed to the lack of full involvement of FUG members in the formulation of bylaws and their approval, because additional bylaws were made by the forest authorities without the consent of the users. The mean PI of forest users at monitoring stage was found to be 54.9%. Thus, the level of participation during this stage was also moderate. This finding disagrees with that of Maraga et al. (Citation2011) who observed low community participation in the afforestation project monitoring and evaluation stage in Kenya. According to Islam et al. (Citation2013), lack of community participation in the monitoring and evaluation stage led to failure of the projects.

Table 7. Results of forest users’ participation in the monitoring stage of the PFM program.

Overall participation of forest users at different stages of the PFM program

shows the overall level of forest users’ PIs at different stages of the PFM program. The results revealed that 65.7% of forest users participated at the planning stage, compared to 59% at the implementation and 54.9% at the monitoring stages. Overall, the PI results showed that the forest users had a moderate level of participation in the PFM program (59.9%) as calculated from the average of the three different stages. This implies that the project had adopted the bottom-up approach to ensure the participation of forest users in the program's development.

Factors influencing levels of forest users’ participation

illustrates the results of the binary logistic regression model and the explanatory variables tested. Regression analysis indicated that different demographic, socioeconomic, biophysical, and institutional related factors influenced the levels of forest users’ participation in the PFM program. A statistically significant fitted model (χ2 = 130.28, P = 0.000) suggested that the model had strong explanatory power. The Nagelkerke R Square value shows that c. 71% of the variations in the level of participation were explained by the explanatory variables considered in the study. Of the 15 explanatory variables tested in the binary regression model, eight were proved statistically significant at 1% and 5% probability levels ().

Table 8. Results of logistic regression model analysis.

The logistic regression results demonstrated that there was a significant and positive association between gender (GEND) and level of participation, implying that male respondents showed a higher level of participation than females (β = 1.517, P = 0.018; ). This difference in gender participation could be attributed to the differences in gender roles in rural Ethiopian society; hence, males have a greater chance of participating than females who take responsibility for childcare and domestic chores. This is in line with the finding of Getacher and Tafere (Citation2013) who reported that, because of their multiple burdens such as childcare, fetching water, and cooking food, women did not actively participate in community forest management in northern Ethiopia.

Similarly, family size was positively and significantly correlated with level of participation in the forest management program (β = 0.340, P = 0.001; ), indicating that an increase in family size could increase the probability of forest users’ levels of participation. According to Chhetri et al. (Citation2013), households with larger families participated more in community forest management activities than smaller ones in Nepal. Larger families provided more workers. This finding is also consistent with that of Dolisca et al. (Citation2006) who reported that households with fewer members participated less in social forestry activities in Haiti. A similar finding, that there was a positive and significant relationship between family size and level of participation in community forest management, was reported from Ethiopia by Getacher and Tafere (Citation2013). One possible explanation for these findings is that households with larger families have a greater demand for forest products such as firewood and cut grass.

Level of education (EDUC) was positively and significantly associated with level of participation (β = 2.225, P = 0.000; ), implying that more educated forest users had a higher probability of participating in the program. According to Obadire et al. (Citation2014), the number of years spent in formal education is one of the important determinants for a high level of participation in a forest management program as education catalyzes the process of information flow and leads the farmers to explore different pathways of getting information about the project and its associated benefits. This finding matches the results of some other studies (Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Chhetri et al. Citation2013; Getacher and Tafere Citation2013), which reported that people with no formal education showed a low level of participation in forest management decision-making processes compared to those with some formal education.

As expected, the logistic regression analysis revealed that income from the forest (AIFFRST) was significant and positive (β = 0.001, P = 0.000; ). This suggests that respondents who had benefited more from the forest products were active participants in program implementation. Similar findings were reported by Degeti (Citation2003) and Getacher and Tafere (Citation2013) in Ethiopia who noted that the higher economic benefit derived from the forest products encouraged participation by households. The result also confirms the finding from India by Agrawal and Chhatre (Citation2006) who reported that higher economic benefits from the forests encouraged the community to participate in the management of forest resources. In line with this, Dolisca et al. (Citation2006) argued that high forest dependency stimulates participation in forest management activities.

The link between distance from the forest (DISFRST) and level of participation was negative and significant (β = –0.367, P = 0.009; ). This implied that as distance of home from the forest increased by 1 km, the probability of a forest user's active participation in forest governance decreased by 0.693 times. This study agrees with Guthiga (Citation2008) who reported that distance from the forest had a negative influence on people's involvement in forest management in Kenya. In northern Ethiopia Getacher and Tafere (Citation2013) found similar results; namely that as distance from the forest increased by an hour, the probability that a household would show a high level of participation declined by 30.4%. This was mainly because households that are far from the forest are not able to access forest benefits so easily as those households which are near.

As expected, restriction on charcoal production and timber harvesting (RCHTH), particularly for commercial purposes, was significantly and negatively associated with level of participation (β = –1.556, P = 0.047; ). This suggests that restrictions imposed on commercial forest product harvesting are likely to discourage participation in PFM programs. Interviews and discussions with respondents also revealed that restrictions imposed on charcoal making and timber harvesting discouraged forest users’ participation in PFM activities. According to respondents, forest policy provides only regulated access and withdrawal rights through issuing of permits from the executive committee. Further, they added that even exploitation of timber for subsistence required permission from the executive committee. This result agrees with the findings of Ameha et al. (Citation2014) who reported that FUG members require permits from the executive committee to extract several timber forest products from live trees for domestic purposes. In the same way, there was a negative association between lack of incentives (LICT) and level of forest users’ participation in the forest management program, which was statistically significant (β = –0.779, P = 0.037; ).

The result from focus group discussions also confirmed that lack of incentives was crucial to the low level of participation in the program. On the other hand, interviews with zonal and district forest managers showed that free access to both timber and non-timber forest products, employment opportunities (particularly in nursery establishment sites), and various forms of capacity-building training should be considered as greater incentives for users to participate in forest governance. In line with this, Agrawal and Ostrom (Citation2001) argued that even if forests are important to people, their participation will be sustained only when there is perceived benefit over costs associated with the incentives offered. Degeti (Citation2003) found that monetary benefits together with free access rights enhanced people's participation in forest conservation activities.

This finding is consistent with the literature on common property resource management (Agrawal and Ostrom Citation2001), showing that lack of incentive is a major determinant of users’ levels of participation in natural resource governance. A similar study by Adhikari et al. (Citation2014) found that incentives for resource governance and management under the community forestry program in Nepal was insufficient to achieve people's effective participation. According to Salam et al. (Citation2005), unless better incentives are considered in a forest management strategy, there is little motivation for people to participate in sustainable forest management.

Coinciding with a working assumption, elite domination (ELD) in decision-making processes was significantly and negatively associated with levels of participation in the logistic regression analysis (β = –0.436, P = 0.042; ). This implies that elite control of the forest management decision-making process reduced forest users’ levels of participation in project activities. This result coincides with the findings of Jumbe and Angelsen (Citation2007), who reported that a major factor hindering households’ participation in forest governance is local elite domination in decision-making, as the poor and disadvantaged groups are less likely to influence decisions in their favor. A similar study by Adhikari et al. (Citation2014) reported that the wealthy elite caste members dominated decision-making positions in community forest management in Nepal, owing to their powers as a result of sociocultural norms, greater capacities, and direct access to state functionaries. Dolisca et al. (Citation2006) found similar results in the study on factors influencing farmers’ participation in a forestry management program in Haiti. As suggested by Jumbe and Angelsen (Citation2007) and by Agrawal and Ostrom (Citation2001) the issue of elite domination in community forest management was addressed through ensuring wider inclusion of disadvantaged groups in all forest management activities.

In general, the binary logistic regression model showed that demographic (GEND), (FAMLYSI), socioeconomic (EDUC), (AIFFRST), biophysical (DISFRST), and institutional (RCHTH), (ELD), and (LICT) variables were the major factors for a higher level of participation in the PFM program.

Conclusion and policy implications

This study has attempted to examine the level of forest users’ participation and identify the main factors that influence their level of participation in a PFM program in Gebradima forest, southwest Ethiopia. The results revealed that forest users’ PI was 65.7% at the planning stage, 59% at the implementation stage, and 54.9% at the monitoring stage of the PFM program: a moderate level of participation in all stages of the program. This indicates that there is some evidence of success in involving the beneficiary in forest management decision-making to achieve sustainable forest management.

The results of logistic regression analysis revealed that, among the selected variables expected to influence the level of a forest user's participation, gender, family size, education level, and forest income had positive and significant effects on the level of participation, while distance from the forest, restriction on charcoal and timber harvesting, elite domination over decision-making, and lack of incentives had negative and significant impacts on the level of participation in the forest management program. This has important implications for making effective PFM strategies to raise the participation level of forest users in sustainable forest management. Accordingly, it is imperative that policy-makers and project designers pay utmost attention to these factors that hinder a high level of participation in PFM programs. Moreover, there is a need to increase the participation level of women and disadvantaged groups in forest management decision-making processes in order to ensure equal benefit for all users. This study supports the need to change the top-down approach of forest conservation by involving FUG members at every stage of forest management to ensure the win-win situation of sustainable management of the forest and better livelihood opportunities for forest users.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all members of the forest user groups and enumerators in the study area who generously participated in this research. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their fruitful comments on this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adhikari S, Kingi T, Ganesh S. 2014. Incentives for community participation in the governance and management of common property resources: the case of community forest management in Nepal. Forest Policy Econ. 44:1–9.

- Agrawal A, Ostrom E. 2001. Collective action, property rights, and decentralization in resource use in India and Nepal. Politics Soc. 29:485–514.

- Agrawal A, Gupta K. 2005. Decentralization and participation: the governance of common pool resources in Nepal's Terai. World Dev. 33:1101–1114.

- Agrawal A, Chhatre A. 2006. Explaining success on the commons: community forest governance in the Indian Himalayas. World Dev. 34:149–166.

- Ameha A, Larsen O, Lemenih M. 2014. Participatory forest management in Ethiopia: learning from pilot projects. Environ Manage. 53:838–854.

- Bagdi GL, Kurothe R. 2014. People's participation in watershed management programmes: evaluation study of Vidarbha region of Maharashtra in India. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2:57–66.

- Chhetri K, Johsen H, Konoshima M, Yoshimtota A. 2013. Community forestry in the hills of Nepal: determinants of user participation in forest management. Forest Policy Econ. 30:6–13.

- Chirenje L, Richard A, Emmanuel G, Musamba B. 2013. Local communities’ participation in decision-making processes through planning and budgeting in African countries. Chinese J Popul Resour Environ. 11:10–16.

- Chowdhury SA. 2004. Participation in forestry: a study of people's participation on the social forestry policy in Bangladesh: myth or reality [M.Phil. dissertation]. Bergen (Norway): Department of Administration and Organization Theory, University of Bergen.

- CSA [Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia] 2013. In: Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Woreda Level from 2014–2017. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency.

- CSA [Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia] 2016. Agricultural sample survey report for the year 2015/2016 (Report on land use utilization for private peasant holdings, meher season). Vol. 4. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency.

- Degeti T. 2003. Factors affecting people's participation in participatory forest management: the case of IFMP Adaba-Dodola in Bale Zone of Oromia Region [MA dissertation]. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University.

- Dolisca F, Carter R, McDaniel M, Shannon A, Jolly M. 2006. Factors influencing farmers’ participation in forestry management programs: a case study from Haiti. Forest Ecol Manag. 236:324–331.

- Eilola S, Fagerholm N, Maki S, Khamis M, Kayhko N. 2015. Realization of participation and spatiality in participatory forest management a policy–practice analysis from Zanzibar, Tanzania. J Environ Plann Manage. 58:1242–1269.

- FARM-Africa. 2014. Five years report on strengthening sustainable livelihoods and forest management program in Ethiopia, Project Summary Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations] 1990. The conservation and rehabilitation of African lands; towards sustainable agriculture. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization United Nations] 2012. Global forest resources assessment. Progress Towards Sustainable Forest Management. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Ferranti F, Beunen R, Speranza M. 2010. Natura 2000 network: a comparison of the Italian and Dutch implementation experiences. J Environ Policy Plan. 12:293–314.

- Getacher T, Tafere A. 2013. Explaining the determinants of community based forest management: evidence from Alamata. Ethiopia Int J Commun Dev. 1:63–70.

- Greene WH. 2008. Econometric analysis. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Guthiga PM. 2008. Understanding local communities’ perception of existing forest management regimes of a Kenyan rainforest. Int J Soc For. 1:145–166.

- Husseini R, Kendie B, Agbesinyale P. 2016. Community participation in the management of forest reserves in the Northern Region of Ghana, Int J Sust Dev World Ecol. 23:245–256.

- Islam KK, Rahman M, Fujiwara T, Sato N. 2013. People's participation in forest conservation and livelihoods improvement: experience from a forestry project in Bangladesh, Int J Biodiversity Sci Ecosystem Services Manage. 9:30–43.

- Islam KK, Jose S, Tani M, Kimihiko H, Krott M, Sato N. 2015. Does actor power impede outcomes in participatory agroforestry approach? Evidence from Sal forests area. Bangladesh Agrofor Syst. 89:885–899.

- Jumbe CB, Angelsen A. 2007. Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecol Econ. 62:661–667.

- Maier C, Lindner, T, Winkel G. 2014. Stakeholders’ perceptions of participation in forest policy: a case study from Baden-Württemberg. Land Use Policy. 39:166–176.

- Manor O, Matthews S, Power C. 2000. Dichotomous or categorical response? Analyzing self-rated health and lifetime social class. Int J Epidemiol. 29:149–157.

- Maraga N, Kibwage K, Oindo O, Oyunge O. 2011. Community participation in the project cycle of afforestation projects in River Nyando basin. Kenya Int J Curr Res. 3:54–59.

- Mbatu RS. 2009. Forest exploitation in Cameroon (1884–1994): an oxymoron of top‐down and bottom‐up forest management policy approaches, Int J Environ Stud. 66:747–763.

- Mowo J, Masuki K, Lyamchai C, Tanui J, Adimassu Z, Kamugisha R. 2016. By-laws formulation and enforcement in natural resource management: lessons from the highlands of eastern Africa. For Trees Livelihoods. 25:120–131.

- Newig J, Fritsch O. 2009. Environmental governance: participatory, multi-level and effective? Environ Policy Governan. 19:197–214.

- NMA [National Meteorological Agency of Ethiopia] 2016. Temperature and rainfall data of gore meteorological station. Addis Ababa: Unpublished document.

- Obadire OS, Mudau MJ, Zuwarimwe J, Sarfo-Mensah P. 2014. Participation index analysis for CRDP at Muyexe in Limpopo province, South Africa. J Hum Ecol. 48:321–328.

- Reed MS, Graves A, Dandy N, Posthumus H, Hubacek K, Morris J, Prell C, Quin CH, Stringer, LC. 2009. Who's in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J Environ Manage. 90:1933–1949.

- Sanginga PC, Kamugisha R, Martin, A, Kakuru A, Stroud A. 2004. Facilitating participatory processes for policy change in natural resource management: lessons from the highlands of south-western Uganda. Uganda J Agricul Sci. 9:958–970.

- Salam MA, Noguchi T, Koike M. 2005. Factors influencing the sustained participation of farmers in participatory forestry: a case study in central Sal forests in Bangladesh. J Environ Manage. 74:43–51.

- Schreckenberg K, Luttrell C, Moss C. 2006. Participatory forest management: an overview: forest policy and environment programme: grey literature. March 2006 ODI UK. Available from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3781.pdf

- Sharma R, Singh P, Padaria RN. 2011. Social processes and people's participation in watershed development in India. J Comm Mobilization Sustain Dev. 6:168–173.

- Shrestha KK, McManus P. 2008. The politics of community participation in natural resource management: lessons from community forestry in Nepal. Aust For. 71:135–146.

- Storck H, Bezabh E, Berhanu A, Andrzje B, Hawariat SW. 1991. Farming systems and farm management practices of smallholders in the Hararghe Highlands: a baseline survey. Germany: Wissenchaftsverlag Vauk Kiel.

- Tacconi L. 2007. Decentralization, forests and livelihoods: theory and narrative. Glob Environ Change. 17:338–348.

- Tadesse S, Woldetsadik M, Senbeta F. 2016. Impacts of participatory forest management on forest conditions: evidences from Gebradima forest, southwest Ethiopia. J Sustain For. 35:604–622.

- Tesfaye Y, Roos A, Campbell J, Bohlin F. 2012. Factors associated with the performance of user groups in a participatory forest management around Dodola Forest in the Bale Mountains. Southern Ethiopia J Dev Stud. 48:1665–1682.