Abstract

The Republic of Korea (ROK) has had a successful experience in greening its land because of strong state policy and public participation. This paper aims to analyze the interest positions, participation, and accountability of multiple actors in the process of greening movements in the ROK. These movements were divided into two phases: forest rehabilitation (1973–1997) and urban greening (1998–2017). During the first phase, farmers caused deforestation by slash-and-burn farming and illegal logging, and governmental agencies acted as helpers controlled the farmers’ deforestation activities. During the second phase, government agencies and enterprises caused deforestation with urban development projects, including construction of housings and roads. Multiple actors including citizens, NGOs, and enterprises helped urban greening through campaigns, donations, and monitoring. As a result, managing interest positions is significant to motivate multiple actors to participate in the greening movement. Participation with clear accountability is meaningful for successful greening. Therefore interest-based participation requiring accountability contributes to greening. This phenomenon indicates interconnection for interest positions, participation and accountability should be considered in designing greening policies.

1. Introduction

Society has a long history of trying to fill the land with greenery. Many countries have experienced the problems of deforestation and forest degradation, which threaten the stability of ecosystems and human well-being. States have established and implemented national greening policies, including national forest programs. Since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992, national forest programs have been widely acknowledged as a means to implement internationally agreed-upon goals for sustainable forest management. With the focus on the environmental quality of urban areas, urban greening movements have emerged in many countries (Rubin Citation2008). Urban green spaces, such as parks, gardens, street trees, creeks, and waterfronts, have been created and revived through urban greening projects in the United States (Westphal Citation2003; Strohbach et al. Citation2013), Canada (De Sousa Citation2003), Russia (Nilsson et al. Citation2007), the United Kingdom (Doick et al. Citation2009), and China (Chen and Jim Citation2008). Individuals and organizations have participated in urban greening activities, such as tree planting (Westphal Citation1999) and community gardens (Rosol Citation2010). Fundamentally, participation of multiple stakeholders in forest management was recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Forests and Intergovernmental Forum on Forests proposals for action at the international level (Elsasser Citation2002). The accountability of stakeholders to solve deforestation problems and implement sustainable forest management has become increasingly important. Participation and accountability have been emphasized as basic general principles of good forest governance (Cadman Citation2009; Secco et al. Citation2014; PROFOR and FAO Citation2011).

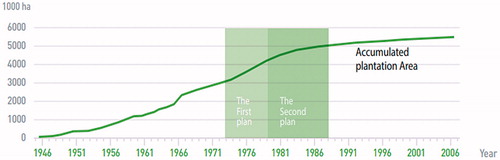

Based on the forest governance literature, this study focuses on participation and accountability by multiple actors with interest positions on forest issues. Interest positions to the problem of deforestation differentiate types of participation and accountability in greening. This study aims to conduct an analysis to improve the interpretation and understanding of the features of public participation and accountability in the process of greening the lands through a case study of the Republic of Korea (ROK). The ROK achieved reforestation despite severe deforestation and forest degradation after the Korean War (1950–1953). During the First National Forest Development Plan (NFDP) (1973–1978) and the Second Plan (1979–1987), the Korea Forest Service (KFS) reforested nearly 2 million ha (Park and Lee Citation2014, pp.5167-5168). A combination of investment in forest protection with a well-equipped technology supported to select suitable species, prepare seedlings, and plant and nurture the trees properly and consequently contributed to successful greening (Park et al. Citation2017). The ROK experienced a forest transition, which is defined as a turnaround in forest cover trends from net deforestation to net reforestation (Mather Citation1992). This ROK case followed the forest transition pathway of the State’s forest policy.

Several scholars have argued that the government-led efforts were a major driving force in the successful rehabilitation of forests in ROK (Lee et al. Citation2010; Bae et al. Citation2012; Park and Youn Citation2017). However, the public and private sectors took part in those forest restoration efforts. Several scholars have mentioned that public participation contributed to the successful forest restoration in the ROK (Lee et al. Citation2010; Bae et al. Citation2012). The ROK has made substantial efforts to create and manage urban green spaces in the last decades. Individuals and organizations have taken part in urban greening projects (Kim et al. Citation2010; Choi et al. Citation2011; Park and Youn Citation2013). This research attempts to find meaningful participation in greening. Linking with the theory of interest position and accountability, contribution of public participation to greening will be interpreted. The research finding will provide us with lessons of effective forest governance.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Interest positions

Vested interests are the driving force behind forest policy (Krott Citation2010). According to Krott (Citation2010), “interests are based on action orientation, adhered to by individuals or groups, and designate the benefits that the individuals or groups can receive from a certain project, such as a forest.” Forest interests constitute one of the most crucial factors for forming and implementing forest policies. Interests always trace back to certain stakeholders, because they indicate only those benefits from which a stakeholder can profit. In forestry, the term “interest” explains the actions taken by the various stakeholders who utilize or protect forests (Park Citation2009). The conflicts between various interests are inevitable in forest management. Creating forest policy is a social bargaining process for regulating the conflicts of forest interests (Krott Citation2010).

Interests generate an actor’s position on forest management issues. In environmental politics, an actor’s relationship to environmental imposition distinguishes their interests. Von Prittwitz (Citation1990) divided interests in environmental politics into three positions: causers, victims, and helpers. According to him, any actor who represents one of these positions has either advantages or disadvantages in the political process. If people are the causers of problems, they lose the legitimation of their activities. Being described as a victim, by contrast, could appeal to sympathy and indicate powerlessness. Being viewed as a helper is advantageous, because the public looks favorably upon those helping to solve forest problems. In forest management, some (causers) cause forest-related conflicts; some (victims) experience economic, ecological, or social loss from the forest conflicts; and some (helpers) contribute to solving the forest conflicts. With interest positions, the relationships among the actors in forest use and conservation can be understood. The interest positions do not remain constant and can change over time (Park Citation2009).

Interest positions have been analyzed in various environmental conflicts, such as the BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) crisis (Feindt and Kleinschmit Citation2011), forest and climate change (Kleinschmit and Sjöstedt Citation2014), felling an old tree (Östberg and Kleinschmit Citation2016) and forest conservation (Park and Kleinschmit Citation2016). The results demonstrate that interest position analysis is a means to describe different positions on forest problems. Therefore, this research examined the interest positions of actors in the greening movement in the ROK.

2.2. Participation

The Forest Principles (United Nations Citation1992) is a non-legally binding agreement on forests signed at the UNCED by many countries. The agreement includes a recommendation that governments should promote and provide opportunities for the participation of interested parties in the development, implementation, and planning of national forest policies (Article 2(d)). Public participation has been regarded as an approach to achieve sustainable forest management (Kangas et al. Citation2010; Cantiani Citation2012; Bruna-Garcia and Marey-Perez Citation2014). In particular, community has been reconsidered as an alternative means of managing forests including forest conservation. Community plays a positive role in resource management as a small spatial unit, as a homogenous social structure, and as a shared norm (Agrawal and Gibson Citation1999). Social capital of communities supports sustainable forest management at the community level (Lee et al. Citation2017). Community forest management has a positive impact on local livelihoods (Rahut et al. Citation2015) and forest conservation (Hayes and Persha Citation2010). Participatory forest management contributes to democratizing forest policy (Elasser 2007).

There are many definitions of public participation. Voluntary public participation is inclusive with respect to the interests of the stake holders, may complement the existing legal and institutional framework, fair and transparent to all participants, based on participants acting in good faith, and does not guarantee the outcome (MCPFE Citation2002). There are various typologies of public participation. Arnstein (Citation1969) illustrated participation in a ladder pattern, with eight rungs corresponding to the extent of a citizen’s power in determining the end product; manipulation, therapy, informing, consultation, placation, partnership, delegated power, and citizen control. Sabucedo and Arce (Citation1991) used two dimensions to classify political participation: a dimension distinguishing political action within and outside the system and a progressive–conservative scale. They labeled four types of political participation: electoral persuasion, conventional participation, violent participation, and direct nonviolent participation. Tosun (Citation1999) classified participation to three types: spontaneous participation, induced participation, and coercive participation—with consideration of multiple attributes. Spontaneous participation is a voluntary and autonomous activity on the part of the people to manage their problems without help from governmental or other external agencies. Induced participation is sponsored, mandated, and officially endorsed. Coercive participation is compulsory and manipulated.

As aforementioned, there are various approaches and classifications of participation. This research focuses on the spontaneity of participation by Tosun (Citation1999). The focus of this study is to investigate if public participation in greening movements in the ROK is spontaneous, induced, or coercive.

2.3. Accountability

Accountability is a traditional requirement of public officials. Various stakeholders have emerged, and their accountability is required for implementing public policies successfully. There are two concepts of accountability: as a virtue and a mechanism (Bovens Citation2010). For virtue, accountability is a normative concept and a set of standards to evaluate public actors’ behavior. As a mechanism, accountability is an institutional relation where an actor can be held accountable by a forum. Accountability can be classified as vertical, horizontal, and diagonal. Vertical accountability mechanisms require governmental officials to appeal downwards to the citizens, and horizontal accountability mechanisms require public officials to report sideways to other officials and agencies within the state (Ackerman Citation2004). Diagonal accountability refers to hybrid combination between vertical and horizontal accountability, involving direct citizen engagement within the state’s institutions (Fox Citation2015, p. 347). The social accountability approach toward building accountability relies on civic engagement and the public responsiveness of states (Fox Citation2015). Citizens and civil organizations participate directly or indirectly in exacting accountability. In the field of forest governance (in particular, good forest governance), accountability is one of the basic general principles of forest governance and includes participation, transparency and legitimacy (Cadman Citation2009; Secco et al. Citation2014; PROFOR and FAO Citation2011). According to Cadman (Citation2009), participation is the fundamental structural aspect of governance to secure legitimacy, and meaningful participation requires internal and external accountability. Effective accountability by public and private actors is an indicator for evaluating the quality of governance (Cadman Citation2009). This research investigates how actors’ accountability in greening movements have been required in the ROK. Various forms of accountability in greening activities will be interpreted considering types of participation by multiple actors.

3. Context of greening movements in the Republic of Korea

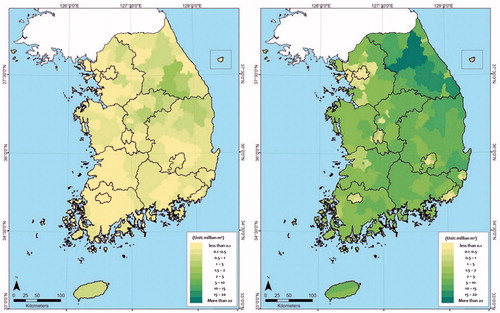

The ROK spent six decades greening its lands (). The lands become greener. Forest areas have increased rapidly for 40 years and then slowly after the end of the Second NFDP in 1987 (). In 1990s and 2000s, forest areas have increased slightly and steadily. On the basis of this phenomenon, Korean greening can be divided into two periods when forest areas rapidly and slightly increased. On the other hand, urbanization influenced greening movements. Urban forest policies have been recognized as a crucial agenda item since the late 1990s (Park and Youn Citation2013, p. 273). The 4th NFDP (1998-2007) include establishment of urban forests as one of eight major strategies by KFS. Focusing on the rate of increase of forest areas and emergence of urban greening policy, two phases of greening are divided in this paper. The exact time of periods is based on the period of NFDPs by KFS. Comparing two phases, meaning, focus areas, goals and approaches of greening have changed over time (). The first phase from 1973 to 1997 focused on forest rehabilitation. After the Korean War (1950–1953), the ROK’s government intensively concentrated on forestland recovery. To avoid deforestation and forest degradation and increase forest areas, the government applied a project approach for reforestation and erosion control through the first and second NFDPs. The ROK achieved successful reforestation through the first (1973–1978) and second (1979–1987) NFDPs through projects implemented mostly in rural areas. Based on forest resources, a forest management infrastructure was established in the third NFDP (1988–1997).

Figure 1. Change in forest cover map from 1963 to 2013. Source: Bae (Citation2014: 38).

Table 1. Comparison of the two phases of greening movements in the Republic of Korea.

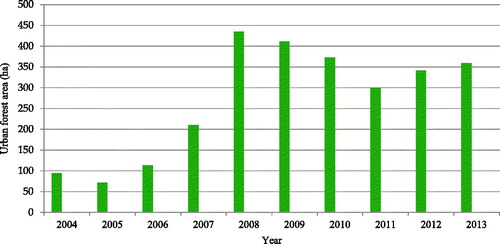

The goal of forest rehabilitation was completely achieved at the first phase of greening. The second phase focused on managing forests which established in the first phase. In particular, the second phase concentrated on sustainable forest management as a new vision of forest management during the fourth (1998–2007) and the fifth NFDPs (2008–2017). Towards sustainable forest management, urban forest policies have been recognized as a crucial policy agenda for increased urban dwellers. The urban population in the ROK increased from 4 million in 1950 to 40.8 million in 2014; the percentage of the population in urban areas increased nearly four-fold from 21% in 1950 to 82% in 2014 (United Nations Citation2010, Citation2014). Many kinds of urban issues emerged such as transportation, education, pollution and do on. Social attention to well-being in urban areas created demand on urban green areas. In greening policies, urban greening was paid more attention than rural greening. KFS established policies to establish urban forests as the second greening movement in the ROK. The Establishment and Management of Forest Resource Act included the term of urban forests since 2007. According to the Basic Plan for Urban Forests (2008–2017) by KFS, central and local governments established and managed various types of urban forests, including street trees, urban parks, and school forests (Koo et al. Citation2013, p. 201). KFS provided metropolitan cities with 80 billion Korean Won (USD 73 million) as grants for constructing urban forests from 2005 to 2010 (Park and Youn Citation2013, p. 275). Urban forests have been planted continuously (). From 2003 to 2013, the total 2,916 ha of urban forests at 2,467 sites have been established (Korea Forest Service Citation2014, p. 372). Since 2000s, greening has been concentrated on urban green spaces and services. Landscape approaches considering multiple interacting land uses (Sayer et al. Citation2013) have also been applied to urban greening. In addition to constructing green spaces, managing ecosystem services, which consist of provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services (World Resources Institute Citation2005, p. 33–37), is also considered in the greening process. In particular, the ROK emphasizes recreation and health services of forests.

Figure 3. Urban forests established from 2004 to 2013. Source: Korea Forest Service (Citation2014, p.388).

4. Method

A case study method was used to identify and interpret features of interest positions, public participation, and accountability by multiple actors in the ROK’s greening movements. This study relied largely on historical records and articles examining those movements. The analysis materials were policy documents, including national plans, legislation texts, and policy reports on greening movements and public participation from 1973 to 2017. The period includes the phases of forest rehabilitation (1973–1997) and urban greening (1998–2017). Related data were collected from policy research on forest rehabilitation (Park and Youn Citation2017) and urban greening (Park and Youn Citation2013). In this research, the characteristics of public participation and accountability in greening movements were described and interpreted by using the actors’ interest positions (causers and helpers) on deforestation and greening. Lessons for designing greening policies will be indicated.

5. Results

Interest positions, causers of deforestation problems, and helpers of greening were described during two periods of greening movements in the ROK. Participation by communities and citizens and accountabilities by public and private actors were interpreted through interest positions. The changes of interest positions, the forms of participation, and accountability were analyzed.

5.1. Interest positions of actors: causers and helpers

5.1.1. The first phase of the greening movements (1973–1997)

The ROK experienced severe deforestation and forest degradation caused by several factors. The Korean War, from 1950 to 1953, caused rapid deforestation and forest degradation. After this war, residents had high demands for food and fuel for cooking and heating. The farmers cultivated farmlands through slash-and-burn activities and illegally logged for firewood, which were proximate causes of deforestation and forest degradation in 1970s (Park and Youn Citation2017). In 1973, about 125 thousand ha, an area equal to 1.3% of the ROK’s forest area, was subjected to slash-and-burn farming (Lee and Bae Citation2007, p. 326). From 1962 to 1972, 17,923 cases of illegal logging occurred. Farmers were main causers of deforestation and forest degradation.

Controlling slash-and-burn farming and illegal logging is required to restore forests. The ROK’s government introduced regulations to eliminate slash-and-burn farming and illegal logging. The KFS established 10-year forest rehabilitation plans—the First (1973–1978) and the Second (1979–1988)—and implemented them successfully. The KFS played a helper role in overcoming deforestation and forest degradation (Bae et al. Citation2012; Park and Youn Citation2017). Public and private actors but had a role in the greening. During the first phase, residents in ‘Sanlimgyes’, small-sized forest communities, played a significant role by planting trees. At the end of the 1950s, a total of 21,628 Sanlimyges, comprising greater than 2 million members had been established (Choi Citation2008, p. 316).

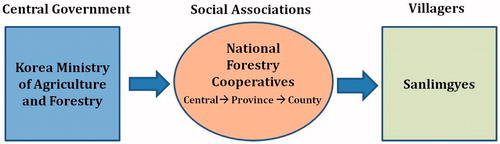

The KFS’s greening policies were integrated to the New Village Movement, named as ‘SaemaulUndong’, a rural development policy from the Ministry of Home Affairs (Park and Youn Citation2017). The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) promoted social associations and delegated authority to them to implement forest activities under the government’s control. The social associations played a role as proxy agents for forest management because of insufficient governmental resources.

The ROK’s government established the National Forestry Cooperatives (NFCs) as a social association in 1962. The NFCs had the task of helping forest owners and villagers understand the relevant policies and encouraging them to participate in forest projects. The contents of the administrative guidance included forest owners’ legal obligations, public mobilization, and the transfer of technical information about the reforestation activities. In the process of establishing of firewood plantations, the NFCs guided the methods of planting and managing trees and transferred general information about the government’s strategies and importance of planting trees as well as specific information about tree species, planting methods, and the project’s procedures.

In summary, a Sanlimgye was a community unit guided by the NFCs. The MAF distributed seedlings to villagers and monitored tree planting using a one-way network between the NFCs and Sanlimgyes (). The NFCs had a hierarchical structure, from central to local (county level), and played a role as policy brokers in the reforestation policy making process.

5.1.2. The second phase of greening movements (1998–2017)

In the process of urbanization, the environmental quality of urban spaces has been a significant subject in the ROK’s urban policies (Koo et al. Citation2013). During this second phase, the social attention paid to urban forests was related green spaces, not fuel and food resources. In the process of urban development, social demands for urban green spaces emerged and occasionally conflicted with development activities, such as the construction of roads and buildings. Typically, the corporations and local governments that operate urban development projects were regarded as the major causers of deforestation and forest degradation (Yoo Citation2001). In many cases, the citizens and environmental NGOs opposed urban development plans and requested forest conservation (Park Citation2009). These organizations voluntarily conducted campaigns and created petitions for the maintenance of urban green spaces (Kim et al. Citation2006). In several cases, such as Daeji Mountain and Sungmi Mountain, the urban development plans were changed to forest conservation plans in accordance with the citizens’ requests (Park Citation2009). During this second phase, various private actors presented their interests in urban green spaces and participated in planting trees. Environmental and forest NGOs, such as the Citizens’ Movement for Environmental Justice, Forest for Life, and the Seoul Green Trust, were established and conducted various campaigns for greening urban areas.

Conflicts with urban green space management emerged. The demands on the green spaces by urban dwellers and environmental NGOS conflicted with other demands on urban development, including construction of housing, roads, and buildings by local governments and enterprises. The national media presented the former as helpers and the latter as causers (Park Citation2009). Citizens voluntarily conducted urban greening campaigns in collaboration with environmental NGOs in several cities. Private enterprises also joined urban forest projects and provided financial support for the greening of urban spaces (Park and Youn Citation2013; Chung et al. Citation2012). The multiple actors shared the same goal, to establish urban green spaces, and cooperated.

5.2. Participation and accountability

5.2.1. The first phase of greening movements (1973–1997)

Sanlimgyes contributed to restoring forests. These associations were not spontaneously formed by villagers in the process of forest rehabilitation. Instead, the government encouraged communities to build Sanlimgyes consisting of forest owners and villagers to protect and plant trees, whereas governmental resources were limited to rehabilitating wholly denuded forest lands.

According to Article 4 of the Provisional Forest Protection Act, enacted in 1951, the Minister of the MAF could organize and deorganize Sanlimgyes and require certain activities from them in the process of planting trees and monitoring forest management. The Sanlimgyes had been created because of the ROK’s requirement for human resources in forest management. The government used its authority and attempted to apply traditional cultures of community to the reforestation projects. The ROK mobilized villagers for reforestation projects because of insufficient financial resources, despite external aid.

In 1953, the Ordinance on Compulsory Labor was enacted and exacted statutory labor from the villagers for tree planting and erosion control projects (Kim et al. Citation2009). In 1963, the Provisional Act on Land Greening indicated that mayors and governors could require compulsory labor from villagers. If the villagers remanded to the compulsory labor could not comply with the order, they had to pay the wages of other laborers or find replacements. At that time, compulsory labor was an effective instrument for implementing the reforestation policy. According to the governmental provisions, the members of the Sanlimgyes were one of the primary targets for compulsory labor. The Sanlimgyes played a role as the compulsory labor organizations that followed orders from the local ministers (Choi Citation2008). Not the villagers, but the ROK’s government, established the managerial regulation of Sanlimgyes, “the Articles of Sanlimgye” in 1962. The Articles included the Sanlimgye’s tasks, such as the following:

Article 9. (1) The members of Sanlimgye shall not collect the forest products specified in the Acts. (2) If the members of the Sanlimgye catch people in violation of collect those forest products, they must immediately submit a report to the Sanlimgye offices. … 4. The members of the Sanlimgye shall be assigned to fatigue duty, such as fire control, according to the directions of Sanlimgye leaders, to protect the forests within the Sanlimgye. … 12. The members of Sanlimgye shall follow instructions for implementing forest policies from the governmental agencies or National Forestry Cooperatives.

The ROK’s government used “administrative guidance” as one method of administration, a traditional governing style since the Japanese colonial era (Han Citation2004, p. 147). The MAF directly and indirectly guided the locals in the implementation forest activities. Compulsory mobilization for national projects can create hostility among the people. Therefore, the government used guidance as a policy means with a non-legal binding. “Administrative guidance occurs when administrators take action of no coercive legal effect that encourages regulated parties to act in a specific way in order to realize some administrative aim (Young Citation1984, p. 923).” Binding administrative guidance is very valuable to the maintenance of a policy system of a limited government (Anthony Citation1992). However, under the military government in the 1970s and 1980s, the villagers might have regarded the government’s guidance as commands with legally binding effects.

Administrative guidance for reforestation was linked with programs and organizations for Saemaul Undong. To inact Saemaul Undong at the local level, the provinces, cities, and districts established divisions. Each officer from the Saemaul Undong division had a responsibility for a Saemaul Undong in a village (Chung et al. Citation2012). This structure enabled the villagers to participate in forest rehabilitation projects at a national scale. Multilevel governmental organizations functioned as action agencies for greening the lands.

The MAF used Sanlimgyes as source of human resources for implementing reforestation policies and forest management activities, such as controlling erosion, illegal logging, and forest fires. The mayors and governors could command the individuals who violated the forest protection regulations to restore what they had damaged or destroyed to its original state. If the violators did not follow these commands, the mayors and governors forced the Sanlimgyes take action and levy expensive fines. If forest owners did not conduct forest management activities such as forest disease control, the mayors and governors could permit the Sanlimgyes to act on behalf of the forest owners. To control forest fires, members of Sanlimgyes were required to organize and manage the forest fire control teams (Korea Forest Service Citation1997, p. 211). During the first NFDP, from 1973 to 1978, a total of 41,934 ha of erosion control works were conducted, and 23.7 million villagers were mobilized for these works (Korea Forest Service Citation1997, p. 414) ().

Table 2. Total work area and the number of participants in the erosion control projects.

To facilitate community participation in the reforestation activities, the ROK’s government financially compensated those who participated in building village nurseries and planting trees to control erosion (Lee and Lee Citation2005, p. 11). Participants in reforestation projects received grains (Korea Forest Service Citation1997, p. 313). Some were given wheat flour through support from the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency as a payment for erosion control activities (Chung et al. Citation2012). At that time, this system was a means for villagers to overcome poverty in the rural communities. Planted trees also provided villagers with food, such as chestnuts, walnuts, persimmons, and citrus.

As aforementioned, the Sanlimgyes took part in establishing firewood forests. According to the Forest Act enacted in 1962, the benefits of firewood forests were distributed to the forest owners (20%) and Sanlimgyes (80%) (Korea Forest Service Citation1997, p. 320–321). The Sanlimgyes could obtain wood for heating and cooking fuel through participation in the reforestation projects. Since 1970, the reforestation activities have been integrated with Saemaul Undong. Saemaul Undong programs included projects for increasing forest income. For example, the villagers could earn money by collecting lawn seeds from neighboring hills and bringing them to the villages’ Saemaul Undong leaders (Kim et al. Citation2009). Therefore, reforestation projects contributed to improving the livelihoods of communities.

At this phase of the greening movements, the residents took part in the reforestation through government regulations and incentives. Their participation was not purely voluntary but coerced by the Ordinance on Compulsory Labor and induced by economic incentives. This type of participation is possible under the vertical structure of administrative power, where the government’s accountability for reforestation is dominant. This successful greening movement was driven by vertical accountability: from state to society.

5.2.2. The second phase of greening movements (1998–2017)

Private actors participated in formation, implementation, and evaluation of policies in the process of creating urban greening policy. In most cases, private actors presented their opinions about protecting and expanding urban green spaces in urban development plans. They took part in identifying and selecting the matters related to urban green spaces and the formulation of urban greening plans. In the process of establishing the master plans for urban parks and green spaces in all of the ROK’s seven metropolitan cities, multiple stakeholders participated in committees on urban parks and in public hearings to share information and opinions about urban forest management (Park and Youn Citation2013). In several cities, the citizens vigorously opposed the city’s drafted urban development plan (Park Citation2009). In the process of establishing the Seoul Forest Park, Forest for Life, a forest NGO suggested an agenda for its construction. This agenda changed the Seoul government’s urban development plan.

Various actors participated in planting trees in urban areas, and they preferably donated money for urban green space maintenance and expansion. Enterprises and citizens offered financial support for constructing urban forests in metropolitan cities (Kim et al. Citation2010). In the case of Umyeon Mountain in Seoul, a donation movement—One Account per Person, emerged (Park Citation2009, p. 133). One account was worth KRW10,000 (around USD 9) from one individual and KRW50,000 to KRW100,000 (USD 45–USD 90) from one association or company. Concerts and campaigns by citizens to raise money for the common purchase of forest lands were conducted. Various actors, such as musicians, priests, teachers, and enterprises, took part in the movement. In the case of Daeji Mountain in Yongin City, the campaign to “Buy a 1-pyeong (3.3 m2) lot” was conducted by citizens and environmental NGOs against the construction of houses by a public corporation, Korea Land Corporation (Park Citation2009, p. 134). The citizens’ donations in these two cases directly influenced forest conservation policies, and this situation is one type of national trust movement. In the case of Seoul Forest approximately 70 private enterprises and 5,000 citizens donated approximately KRW5 billion (USD 4.3 million) to establish urban forests from May 2003 to April 2004 (Kim et al. Citation2009).

In several cases of urban green space management, various actors joined in monitoring the construction and management. In the case of Seoul Forest, monitoring groups consisted of citizen volunteers. At Daeji Mountain (Kim et al. Citation2006), the committee consisted of various actors, including residents, NGOs, forestry experts, and public corporations, who conducted field monitoring activities while establishing an urban forest park. The activities of committees were also evaluated through a series of public meetings. Therefore, multiple actors participated in the formation, implementation, and evaluation of urban greening policies.

Voluntary agreements have played a significant role in the ROK’s urban greening movements. Multiple actors participated in agreements for establishing urban green spaces. Several metropolitan cities and private actors, such as companies, banks, and churches, worked cooperatively with urban greening projects based on partnership agreements (Park and Youn Citation2013). The agreements included the tasks of signatories, for example, planting trees by citizens and environmental NGOs and financial donations by enterprises. Accountability for greening was distributed to public and private actors through voluntary agreements that delineated the bi- or multilateral accountability in greening.

Participation by private enterprises in greening movements is known as corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (Chung et al. Citation2012). CSR can convey positive images of corporations to the public and might be a significant determinant of an investor’s socially responsible investment decisions (Kim et al. Citation2009). A private enterprise, Yuhan-Kimberly, provided financial support for urban forest projects and this has been regarded as a successful case of green CSR by consumers in the ROK (Park and Youn Citation2013; Chung et al. Citation2012).

The KFS established urban forest policies as one national forest management strategy. Following these policies, local governments built and managed urban forest parks. Some local governments created unique policies for establishing and managing urban forests. For example, Jeollanam-do (Province) announced the 10-Year Jeollanam Forest Project (2015–2024),” including establishing forests through the collaboration of multiple actors to maximize multiple forest values (Yoon et al. Citation2016). Jeollanam-do is implementing this project as a place strategy for the differentiation of provinces focusing green spaces. This branding approach is an entrepreneurial development scheme that aims to differentiate cities or municipalities from their national and international competitors based on strengths and competitive advantages (Gulsrud et al. Citation2013). Jeollanam-do is trying to make the province an attractive and livable place with green spaces.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This study described and interpreted the interest positions, participation, and accountability by the actors in the ROK’s greening movements, which occurred in two phases: forest rehabilitation (1973–1997) and urban greening (1998–2017). In the first phase of the greening movements, farmers’ illegal activities, such as slash-and-burn farming and logging, were the main causes of deforestation. The government as a helper controlled the farmers’ behavior to solve the problem of deforestation using policy instruments. The government provided financial and technical support for reforestation projects and encouraged villagers to participate in the projects cooperatively with regulatory and economic instruments. The key to the successful completion of the reforestation projects was the ROK’s interventions and innovations in their administrative reforms (Yoo Citation1987), such as coordinated national plans, collaboration among branches of governmental, and organizational reformation (Park and Youn Citation2017). Obviously, the residents or farmers were the causers and the governments were helpers in deforestation and forest degradation. Governmental administration had controlled deforestation and implemented reforestation. Using regulatory instruments, such as laws and economic incentives, governments mobilized villagers to implement reforestation projects and led a new village movement called Saemaul Undong, in which communities, including Sanlimgyes, were required to join reforestation activities with a top-down direction. The government’s administrative guidance noted the importance of public participation in implementing reforestation projects and encouraged villagers to participate. Villagers were partially paid for their labor in reforestation projects. Here public participation was based on the interests in greening for development of the villages. When the demands on trees as food and fuel were satisfied, residents could participate in conserving and planting trees. Governments required accountability by residents in greening with various types of policy instruments. In particular, governments required citizens’ accountability in following the rules of prohibition of illegal logging and performing plantation activities. Requirement of residents’ accountability was effective for greening.

In the second phase of the greening movements, the ROK addressed the modern urban forestry conflicts (Gritten et al. Citation2013) between construction projects and green space protection. Private actors requested a change in the cities’ urban planning to include accountability for urban green space management. To maintain and increase green spaces within urban areas, multiple actors spontaneously participated in forming, implementing, and monitoring urban greening policies with a bottom-up direction. Through cooperation and voluntary agreements, these multiple actors established and managed urban green spaces. At that time, for nature conservation, a national trust (NT) movement based on voluntary participation emerged in the ROK. The NT movement emerged in England in 1895 to promote the permanent preservation of lands and tenements of beauty or historic interest for the benefit of the nation, and, with respect to lands, for the preservation of their natural features and of animal and plant life (Harvey Citation1987). This movement prevents lands including forests from being developed under the market’s economic logic, through donations and voluntary activities by the private sector (Park Citation2009). In several cases in the ROK, citizens and enterprises donated money to purchase forest lands to stop house construction (Park Citation2009, p. 133–134). Here citizens have interests in public values of urban forests for enhancing quality of their lives. They criticized urban development plans by local governments, newly recognized their accountability in greening urban spaces and implemented their accountability in greening with their own resources. They introduced new greening approaches such as campaigns for maintaining green spaces and donation for creating and keeping green space in urban areas. Multiple stakeholders, including citizens, enterprises, environmental NGOs, churches and so on, share accountability and invest their resources in greening.

Comparing the first and second phases of greening, public participation and accountability in planting trees (), the features of interests-based participation and meaningful participation requiring accountability in successful greening are found. Types and levels of participation in greening is based on interests. To increase or induce participation by multiple actors in greening, it is necessary to understand the actors’ interest positions on forests and to manage forest interests by multiple actors. When demands on forest resources for fuel and food were dominant in the first phase of greening, farmers or residents, who needed land to grow food and wood for cooking food and keeping their homes warm, engaged in slash-and-burn farming and illegal logging that caused deforestation. Many developing countries experience the same causes of deforestation (Youn et al. Citation2017). The demand on provisioning services of ecosystem such as fuel and food can make farmers causers of deforestation. This case indicates that governmental agencies as helpers for greening should control the deforestation activities and require accountability by forest communities in planting trees. In the second phase, the governmental agencies and corporations with the interests in urban development were the causers of deforestation because of road and building construction. Citizens with high preferences for the recreational services which green spaces provide (Koo et al. Citation2013) played a helper role in the greening, especially in urban areas. Some enterprises also emerged as the helpers and engaged in green CSR through greening activities: the donation of financial resources and participation in planting and monitoring the trees (Chung et al. Citation2012). Recently, municipalities emerged as a helper in greening through using green spaces as a local brand (Yoon et al. Citation2016). This phenomenon indicates that multiple actors have interests in urban green spaces and participate in creating urban green spaces recognized their accountability. Throughout the two greening phases, the actors’ positions on their interests in the forest have been changed and the types of their participation have been diversified. The diverse ecological, economic, and social conditions of forests results in the prioritization of forest's contributions to human well-being. People who lived in the areas with a fuel shortage, placed high values on forest provisioning services in the first phase, while urbanized societies placed high values on the cultural services of forests such as recreation and the regulating services of forests such as climate change mitigation, in the second phase. This change of preferred forest interests caused changes in the actors’ positions on deforestation and greening. The level of participation was also changed by interests. Greening activities were based on community participation in both phases. In the second phase, multiple actors voluntarily participated in greening activities. According to the participation ladder by Arnstein (Citation1969), community participation in the first phase belonged to “manipulation,” the lowest rung of participation. At that time, communities and residents were mobilized by governmental agencies to plant trees. Coercive participation (Tosun Citation1999) led to successful reforestation. In the second phase, civic participation belongs to “partnership,” the highest rung of participation (Arnstein Citation1969). Without pressure, local governments, citizens, enterprises, and NGOs participated in the process of urban greening policy making, including policy formation and implementation. They built partnerships with government agencies for green space management in urban areas. Spontaneous participation (Tosun Citation1999) led to successful urban greening. At the first phase the typical interests in forests existed. Interests by farmers and government could be clearly divided. Public participation in greening is simply designed and mobilized, considered control of deforestation activities. However, in the second phase multiple forest interests emerged. Citizens have different positions to greening. Governments have also different positions to deforestation and greening. Depending on the interests, social actors play dual roles as causers of deforestation and helpers of greening. Therefore figuring out and managing forest interests is a necessary step for successful greening. For example, when fire woods which provide forest provisioning services can be substituted to other energy resources, deforestation activities by individuals can be controlled (Park and Youn Citation2017). When interest in urban green spaces emerge at the society, greening activities can be vitalized by multiple actors.

Table 3. Comparison between the phases of greening movements.

Participation requiring accountability contributes to successful greening. In the first phase, the government agencies’ administrative power was dominant in avoiding slash-and-burn farming and illegal logging and rehabilitating forests. Vertical accountability led by the government was effective in controlling the causes of deforestation. In the second phase, private actors participated in the greening movement as partners with public actors. Voluntary agreements requested the accountability of public and private actors in greening activities. Based on voluntary partnership agreements, private actors, including citizens, enterprises, scientists, and environmental NGOs, executed their accountability in the greening process through discussing and deliberating the greening agenda as committee members, donating money for establishing green spaces, and implementing greening performances and the monitoring of green space management. In both phases of successful greening, participation in greening is based on the binding and non-binding institution requiring accountability. This study supports that meaningful participation requires accountability (Cadman Citation2009) for successful greening. Accountability shifted from government-led to civil society-led over time in the ROK. Network cohesion between public and private actors was promoted in the ROK’s greening movements. These phenomena can be named as forest governance (Secco et al. Citation2014). Participation and accountability is key themes in governance (Blair Citation2000). For good forest governance, participation with accountability is necessary.

The features in are interconnected and interacted. The emergence of diverse forest interests and changes in preferred forest interests caused the changes of interest positions about deforestation and greening by multiple actors. New interests motivated voluntary participation by civil society and a new approach to local development by municipalities. Participation and accountability have shifted from government-led to society-led. Based on the research results, it cannot be argued that government-led greening is wrong and society-led greening is right. The ROK case indicates that both methods, government-led and society-led, can be appropriate for greening, according to the context of forest interests. Therefore, greening strategies should be designed with consideration for social context, including demands on forests and social institutions supported by accountability. The research results indicate that meaningful participation requiring accountability by multiple actors including civil society is necessary to successful greening.

Analyzing greening movement phenomena has some limitations. By focusing on changes at a national scale, local phenomena with statistical data were not described. In the future, the field studies at the local sites could add more specific information on community participation for greening. This research focused on the ROK. These research results cannot be applied to other countries directly. However, the ROK case provides insights for solving the similar problems of deforestation and forest degradation that other countries face in rural and urban areas. This study contributes to understanding the interconnection among interest positions, participation, and accountability by actors and designing greening strategies in the forest governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerman J. 2004. Co-governance for accountability: beyond “exit” and “voice”. World Dev. 32:447–463.

- Agrawal A, Gibson CC. 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 27:629–649.

- Anthony RA. 1992. Interpretive rules, policy statements, guidances, manuals, and the like: should federal agencies use them to bind the public? Duke Law J. 41:1311–1384.

- Arnstein SR. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Plann. 35:216–224.

- Bae JS. 2014. Leveraging public programmes with socio-economic and development objectives to support conservation and restoration of ecosystems: lessons learned from the Republic of Korea’s National Reforestation Programme. Daejeon (Republic of Korea): Korea Forest Service. https://www.cbd.int/ecorestoration/doc/Korean-Study_Final-Version-20150106.pdf

- Bae JS, Joo RW, Kim YS. 2012. Forest transition in South Korea: reality, path and drivers. Land Use Policy. 29:198–207.

- Blair H. 2000. Participation and accountability at the periphery: democratic local governance in six countries. World Dev. 28:21–39.

- Bovens M. 2010. Two concepts of accountability: accountability as a virtue and as a mechanism. West Eur Politics. 33:946–967.

- Bruna-Garcia X, Marey-Perez MF. 2014. Public participation: a need of forest planning. Iforest Biogeosci For. 7:216–226.

- Cadman T. 2009. Quality, legitimacy and global governance: a comparative analysis of four forest institutions. Doctoral dissertation. Tasmania (Australia): University of Tasmania.

- Cantiani MG. 2012. Forest planning and public participation: a possible methodological approach. Iforest Biogeosci For. 5:72–82.

- Chen WY, Jim CY. 2008. Cost–benefit analysis of the leisure value of urban greening in the new Chinese city of Zhuhai. Cities. 25:298–309.

- Choi SJ, Hwang WS, Kim SH, Park CS. 2011. Analysis of social networks in the management organization of Seoul Forest Park. J Korean Inst Landscape Archit. 39:74–82.

- Choi B. 2008. The developments and character of setting up the forestry mutual-aid society in 1945–1960s. J Historical Stud. 90:291–336.

- Chung JY, Yeo-Chang Y, Cho D-S. 2012. Evolutionary governance choice for corporate social responsibility: a forestry campaign case in South Korea. Int J Sustainable Dev World Ecol. 19:339–348.

- De Sousa CA. 2003. Turning brownfields into green space in the City of Toronto. Landscape Urban Plann. 62:181–198.

- Doick KJ, Sellers G, Castan-Broto V, Silverthorne T. 2009. Understanding success in the context of brownfield greening projects: the requirement for outcome evaluation in urban greenspace success assessment. Urban For Urban Greening. 8:163–178.

- Elsasser P. 2002. Rules for participation and negotiation and their possible influence on the content of a National Forest Programme. For Policy Econ. 4:291–300.

- Elsasser P. 2007. Do “stakeholders” represent citizen interests? An empirical inquiry into assessments of policy aims in the National Forest Programme for Germany. For Policy Econ. 9:1018–1030.

- Feindt PH, Kleinschmit D. 2011. The BSE crisis in German newspapers: reframing responsibility. Sci Cult. 20:183–208.

- Fox JA. 2015. Social accountability: what does the evidence really say? World Dev. 72:346–361.

- Gritten D, Mola-Yudego B, Delgado-Matas C, Kortelainen J. 2013. A quantitative review of the representation of forest conflicts across the world: resource periphery and emerging patterns. For Policy Econ. 33:11–20.

- Gulsrud NM, Gooding S, van den Bosch CCK. 2013. Green space branding in Denmark in an era of neoliberal governance. Urban For Urban Greening. 12:330–337.

- Han SY. 2004. Historical survey of the indirect administrative guidance. Korean Public Admin Rev. 38:147–170.

- Harvey HJ. 1987. Changing attitudes to nature conservation: The National Trust. Biol J Linn Soc. 32:149–159.

- Hayes T, Persha L. 2010. Nesting local forestry initiatives: revisiting community forest management in a REDD + world. For Policy Econ. 12:545–553.

- Kangas A, Saarinen N, Saarikoski H, Leskinen LA, Hujala T, Tikkanen J. 2010. Stakeholder perspectives about proper participation for Regional Forest Programmes in Finland. For Policy Econ. 12:213–222.

- Kim JH, Tae YL, Chang CY, Kim KM. 2010. Study on current status and direction of environmental governance around urban forest in Korea: with a focus on the recognition of local government officials. J Korean For Soc. 99:580–589.

- Kim B, Kwon G, Park M, Park H, Bae I, Oh S, Youn Y, Lee S. 2009. Analysis of Korean successful case of reforestation. Daejeon (Republic of Korea): Korea Forest Service. (In Korean.)

- Kim J, Park M, Tae Y. 2006. Collaborative and participatory model for urban forest management: a case study of Daejisan in Korea. J Korean For Soc. 95:149–154.

- Kim SH, So JK, Han KW, Park CS, Hwang WS, Choi SJ. 2009. Measures to enhance social capital in the field of national territorial management II. Anyang (Republic of Korea): Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements.

- Kleinschmit D, Sjöstedt V. 2014. Between science and politics: Swedish newspaper reporting on forests in a changing climate. Environ Sci Policy. 35:117–127.

- Koo J, Park M, Youn Y. 2013. Preferences of urban dwellers on urban forest recreational services in South Korea. Urban For Urban Greening. 12:200–210.

- Korea Forest Service. 1997. The 50-year history of Korea forest policy. Seoul (Republic of Korea): Korea Forest Service. (In Korean.)

- Korea Forest Service. 2010. National statistics of urban forests. Daejeon (Republic of Korea): Korea Forest Service. (In Korean.)

- Korea Forest Service. 2014. Statistical yearbook of forestry 2014. Vol. 44, Daejeon (Republic of Korea): Korea Forest Service. (In Korean.)

- Krott M. 2010. Forest policy analysis. Dordrecht (The Netherlands): Springer.

- Lee KB, Bae JS. 2007. Factors of success of the clearance policy for slash-and-burn fields in the 1970. J Korean For Soc. 96:325–337. (In Korean, with English summary.)

- Lee DK, Lee YK. 2005. Roles of Saemaul Undong in reforestation and NGO activities for sustainable forest management in Korea. J Sustainable For. 20:1–16.

- Lee Y, Rianti IP, Park M. 2017. Measuring social capital in Indonesian community forest management. For Sci Technol. 13:133–141.

- Lee DK, Shin JH, Park PS, Park YD. 2010. Forest rehabilitation in Korea. In Lee DK, editor. Korean forests: lessons learned from stories of success and failure. Daejeon (Republic of Korea) Korea Forest Research Institute; p. 35–58.

- Mather AS. 1992. The forest transition. Area. 24:367–379.

- MCPFE (Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe). 2002. Public Participation in Forestry in Europe and North America, Vienna, Austria; p. 4–14. http://www.foresteurope.org/documentos/public_participation_in_forestry.pdf

- Nilsson K, Åkerlund U, Konijnendijk CC, Alekseev A, Caspersen OH, Guldager S, Kuznetsov E, Mezenko A, Selikhovkin A. 2007. Implementing urban greening aid projects–the case of St. Petersburg, Russia. Urban For Urban Greening. 6:93–101.

- Östberg J, Kleinschmit D. 2016. Comparative study of local and national media reporting: conflict around the tv oak in Stockholm, Sweden. Forests. 7:233.

- Park M, Kleinschmit D. 2016. Framing forest conservation in the global media: an interest-based approach. For Policy Econ. 68:7–15.

- Park M, Lee H. 2014. Forest policy and law for sustainability within the Korean Peninsula. Sustainability. 6:5162–5186.

- Park H, Lee JY, Song M. 2017. Scientific activities responsible for successful forest greening in Korea. For Sci Technol. 13:1–8.

- Park M, Youn Y. 2013. Development of urban forest policy-making toward governance in the Republic of Korea. Urban For Urban Greening. 12:273–281.

- Park M, Youn Y. 2017. Reforestation policy integration by the multiple sectors toward forest transition in the Republic of Korea. For Policy Econ. 76:45–55.

- Park M. 2009. Media discourse in forest communication: the issue of forest conservation in the Korean and global media. Göttingen (Germany): Cuvillier.

- PROFOR (The Program on Forests), FAO. 2011. Framework for assessing and monitoring forest governance, Rome, Italy.

- Rahut DB, Ali A, Behera B. 2015. Household participation and effects of community forest management on income and poverty levels: empirical evidence from Bhutan. For Policy Econ. 61:20–29.

- Rosol M. 2010. Public participation in post-Fordist urban green space governance: the case of community gardens in Berlin. Int J Urban Reg Res Reg . 34:548–563.

- Rubin V. 2008. The roots of the urban greening movement. In: Birch, E., Wachter, S. editors. Growing greener cities: urban sustainability in the twenty-first century. Philadelphia, (PA): University of Pennsylvania Press; p. 187–206.

- Sabucedo J, Arce C. 1991. Types of political participation: a multidimensional analysis. Eur J Political Res . 20:93–102.

- Sayer J, Sunderland T, Ghazoul J, Pfund JL, Sheil D, Meijaard E, Venter M, Boedhihartono SK, Day M, Garcia C, et al. 2013. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 110:8349–8356.

- Secco L, Da Re R, Pettenella DM, Gatto P. 2014. Why and how to measure forest governance at local level: a set of indicators. For Policy Econ. 49:57–71.

- Strohbach MW, Lerman SB, Warren PS. 2013. Are small greening areas enhancing bird diversity? Insights from community-driven greening projects in Boston. Landscape Urban Plann. 114:69–79.

- Tosun C. 1999. Towards a typology of community participation in the tourism development process. Anatolia. 10:113–134.

- United Nations. 1992. Forest Principles. http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126–3annex3.htm

- United Nations. 2010. World Urbanization Prospects, the 2009 Revision, New York.

- United Nations. 2014. World Urbanization Prospects: the 2014 Division, New York.

- von Prittwitz V. 1990. Das Katastrophenparadox: Elemente einer Theorie der Unweltpolitik. Opladen (Germany): Leske + Budrich.

- Westphal LM. 1999. Growing power: social benefits of urban greening projects. Doctoral dissertation. Chicago: University of Illinois.

- Westphal LM. 2003. Urban greening and social benefits: a study of empowerment outcomes. J Arboricul. 29:137–147.

- World Resources Institute. 2005. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. Washington (DC). http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.354.aspx.pdf.

- Yoo JH. 1987. Interventions and innovations for administrative reforms in Korea: the Saemaul Undong. J East West Stud. 16:57–77.

- Yoo RH. 2001. A study on the urban forests management by the residents participation. Doctorial thesis. Seoul (Republic of Korea): The Konkuk University.

- Yoon B, Kim H, Yang C, Heo Y, Kim M, An K. 2016. Significant of local forest policy on 10-years Jeonnam Forest Project. Korean J For Econ. 23:31–44. (In Korean, with English summary.)

- Youn YC, Choi J, de Jong W, Liu J, Park M, Camacho LD, Damayanti ED, Huu-dung N, Tachibana S, Bhojvaid PP, et al. 2017. Conditions of forest transition in Asian countries: a qualitative comparative analysis. For Policy Econ. 76:14–24.

- Young MK. 1984. Judicial review of administrative guidance: governmentally encouraged consensual dispute resolution in Japan. Columbia Law Rev. 84:923–983.