?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Forest resources are a salient and critical issue requiring ongoing attention by the Thai government. Community forest management (CFM) is a practice used to, among other things, resolve land use issues and regulate the extraction and use of non-timber forest product (NTFPs). Managing as a community forest can not only enhance the livelihoods of the local people but also improve their socio-economic condition. This research was conducted at the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest located in Pa Mae Phrik National Forest Reserve in Thailand’s northern province of Lampang. We collected species biodiversity data of the forest’s total area of 3,925 ha using a systematic sampling method, and twenty-five 40 × 40 m (0.16 ha) survey plots were established in the community forest. Interviews of 159 household heads and/or other household representatives were conducted using a designed questionnaire. The questionnaire focused on information regarding the households’ NTFP utilization habits and engagement in CFM processes. A forest survey was conducted which found that there were 197 plant species, 144 genera, and 62 families in the community forest. Of these, 160 plant species were classified as having medicinal uses, 89 were used as food, 37 as extractives, 32 for firewood, and 12 for fibers. This study also revealed that unmonitored over-exploitation of NTFPs may negatively impact forest biodiversity. As surveyed, 68.55% of households depended on NTFPs. The value of the harvested NTFPs was 6.35% of the total community income. A positive correlation between NTFP income and CFM suggests that utilization of NTFPs combined with CFM can create income opportunities and promote participation in CFM. In addition, income earned from NTFPs and participation in CFM were directly related to the socio-economics of identifiable groups in this community. Laborers, merchants, and low-income families utilized NTFPs to a lesser degree. Single people, household heads, those with a bachelor’s degree, and low income families were less likely to participate in CFM while land owners were more likely to do so. This study implies that the harvesting of NTFPs should not go unchecked, especially of species that are threatened or likely to be threatened if over-harvested. Efforts to enhance lower income household utilization, to more equitably distribute the benefits, and to incentivize community involvement should be prioritized as doing so is crucial to maintaining a healthy supply of NTFPs and safeguarding the community forest biodiversity.

Introduction

Worldwide, forest resources are crucial to the livelihoods of people who live in proximity. Approximately 1.6 billion local people, or more than 25% of the world’s population, depend on bio-diverse forest resources for their livelihoods (The World Bank Citation2001), the value of which has been estimated to be as much as US $166–490 billion per year (Liang et al. Citation2016). Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are crucial contributors to rural communities, and lower income households have been found to depend on them to support their livelihoods in many parts of the world (Amgrose-Oji Citation2003; Heubach et al. Citation2011; Melaku et al. Citation2014; Liu and Moe Citation2016; Saifullah et al. Citation2018). Developing countries have been found to rely on forests for upwards of 28% of their total household incomes Angelsen et al. (Citation2014).

Thailand is a developing country. Forests cover nearly one-third of its land area (RFD Citation2019) and it is rich in bio-diverse forest resources with over 15,000 species of plants, accounting for 8% of the plant species found globally (ONEP Citation2009). Roughly 23 million people live near national forest reserve areas that supply NTFPs, such as edible plants, wild fruit, medicinal plants, fuelwood, mushrooms, insects, wild animals, fibers, and extractives that provide crucial subsistence and income opportunities valued at US $25,000 per village and over US $2 billion nationwide (ONEP Citation2004; Witchawutipong Citation2005; ITTO Citation2006; Jarernsuk et al. Citation2015; Larpkerna, et al. Citation2017; Mianmit et al. Citation2017).

Management of these forests is critical to their continued viability as a source of crucial resources. Over-dependency leads to biodiversity loss which can have profound and far-reaching consequences (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Citation2005) on species composition and distribution (Sagar et al. Citation2003; Thapa and Chapman Citation2010) and regeneration (Murali et al. Citation1996; Popradit et al. Citation2015). Over-exploitation of forest resources can also have a long term, harmful impact on overall ecosystem health and resiliency (Rew et al. Citation2005). Consequently, there is inherent conflict between resource utilization and biodiversity conservation that requires purposeful and properly focused management practices to address.

Community forest management (CFM) has been widely recognized as an effective management approach to help resolve this conflict. An estimated 14% of all forests in developing countries are governed by CFM; it has been adopted and implemented in many such countries, including Thailand (Gilmour et al. Citation2004). Community forests provide environmental, social and economic benefits (RECOFTC Citation2007), can supplement and assist lower income households (Blair and Olpadwala Citation1988), support the sustainability of NTFPs and help alleviate poverty in remote areas (Gilmour et al. Citation2004; Thammanu and Caihong Citation2014; Mianmit et al. Citation2017). Increased trade in NTFPs has been shown to slow deforestation by increasing the economic value of forest biodiversity (Shanley et al. Citation2002); effective local institutional management can reduce forest degradation (Ostrom et al. Citation1994; Ostrom Citation2005). In addition, the responsible use of NTFPs under CFM can lead to successful forest management that is beneficial to well-being and ecosystem services alike, thereby improving rural livelihoods and conserving forest biodiversity simultaneously (Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019b).

CFM emphasizes local interest and participation in protecting forest resources. Successful implementation of forest management depends on this local participation as well as on other factors and forms of engagement in CFM, the analysis and understanding of which can help to define effective CFM practices. People’s participation in management activities, knowledge and perceptions regarding forest management, management regulations, and benefit sharing can all provide useful insight into how CFM can be implemented to maximize the benefit while safeguarding the resources (Ostrom et al. Citation1994; Pragtong Citation1995; Ostrom Citation2005; Salam et al. Citation2006; Sunderlin Citation2006; Negi et al. Citation2018).

Certain socio-demographics of a community can also impact forms and levels of engagement (Babulo et al. Citation2008; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Heubach et al. Citation2011; Mutenje et al. Citation2011; Kar and Jacobson Citation2012; Melaku et al. Citation2014; Schaafsma et al. Citation2014; Aminu et al. Citation2017; Suleiman et al. Citation2017; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019a) and participation in CFM (Lise Citation2000; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Bahdur et al. Citation2013; Musyoki et al. Citation2016; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019b; Zang et al. Citation2019). Knowledge of these relationships can help to inform effective management practices.

In Thailand, the Royal Forest Department (RFD) has promoted CFM since 1987 (RFD Citation2014), and it has been widely implemented. Community forest establishment projects have been initiated in more than 17,400 villages, covering a total area of 1.2 million ha, or 7% of the country’s total forest area (RFD Citation2020). The emphasis on local participation in management was reiterated by the Thai government’s Community Forest Act B.E. 2562 of May 24, 2019 which granted local decision making authority to communities who managed community forest projects (Royal Thai Government Citation2019).

In spite of the breadth of CFM projects throughout Thailand, the challenges and threat of biodiversity loss persist. Nearly 1,500 plant species have been classified as vulnerable, 207 are endangered, and 18 species are critically endangered (DNP Citation2017). Continued and unmonitored extraction can have a long-lasting and potentially irreparable effect on the forest ecosystem as well as on the livelihoods of dependent residents. Understanding the factors that contribute to species diversity and the vagaries of local resident engagement in forest management and their utilization of NTFPs provides knowledge pertinent to sustainable and effective forest management practices.

With this goal in mind, the objectives of this study were to (1) analyze the species diversity and the current status of the community forest, (2) evaluate the effectiveness of CFM and its relationship with NTFP utilization, and (3) identify socio-economic demographics that impact NTFP income and engagement in CFM. The information to be gained in this research can help to safeguard the longevity and proliferation of forest resource as well as the livelihoods those resources support, both in the study area and community forests country-wide.

Materials and methods

Study area

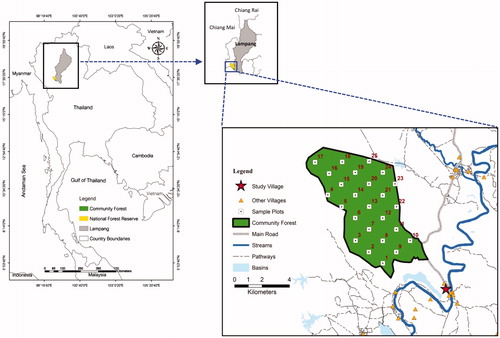

Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum (village no. 3), in Mae Phrik District of Lampang Province in northern Thailand, was chosen as the study area. It is located between N 17°22′48″ and N 17°27′47″ and the E 99°00′47″ and E 99°05′48″ in the Pa Mae Phrik National Forest Reserve. The total area of the community forest is 3,925 ha (). The village has 265 households and a population of approximately 1,060 people (MPSAO Citation2018).

This study area was classified as deciduous forests: mixed deciduous forest and dry dipterocarp forest. Generally, deciduous forests in Thailand represent 18.26% of the country’s total forest area (RFD Citation2019). These forests serve a vital role as a source of biodiversity while contributing to forest ecosystem services that improve the livelihoods of those who live in close proximity (Kabir and Webb Citation2006; Chaiyo et al. Citation2011; Larpkerna et al. Citation2017; Mianmit et al. Citation2017). Similarly, the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest has and continues to provide these services to its local residents. However, unchecked extraction of forest resources can create an existential threat to the viability of the forest and its services, evidence of which was widespread and recognized.

Since 2008, local people have managed the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest in collaboration with the RFD under a community forest project. Implementation of this CFM project was in response to the significant and impactful damage caused by forest land encroachment and illegal logging. Under CFM, awareness of the importance of the forest expanded, increased income was realized and livelihoods were improved.

This area experienced the damage, ramifications and long term threats posed by the pre-CFM conditions as well as the benefits of the responsive implementation of CFM. Thus, it is a suitable model to study in order to develop strategies to ascertain the impact of CFM and to improve sustainable forest management in Thailand.

Framework, variables, and hypotheses

Framework

To increase the livelihoods of the local community and to conserve biodiversity, forests should be managed for sustainability. CFM has been embraced by institutions, academics, and governments, and employed in different ways. Several reports have shown that CFM can enhance local livelihoods and contribute to sustainable forest conservation (Salam et al. Citation2006; Chen et al. Citation2013; Chechina et al. Citation2018). To be successful, CFM should effectively manage forest resources.

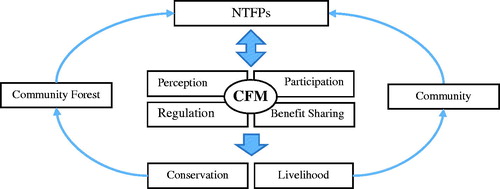

The framework of this study is displayed in . Under community management, forests provide diverse tree species and NTFPs that are beneficial to the rural communities. The success and effectiveness of CFM in doing so can be evaluated by investigating the four components of CFM (Pragtong Citation1995; Salam et al. Citation2006; Sunderlin Citation2006; Negi, et al. Citation2018). Generally, these are (1) people’s level of participation in management efforts, (2) knowledge and opinions as to regulations and their effectiveness, (3) perception and understanding of CFM, and (4) benefit sharing. Effective management can expand the provision of NTFPs in support of rural community livelihoods and to conserve the community forest biodiversity. Because NTFP income could incentivize participation in CFM, we presume a relationship between NTFP income and CFM effectiveness.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework links between utilization of NTFPs and CFM in community forest for livelihood and biodiversity conservation.

In addition, different socio-economic factors of people in the community could impact NTFP extraction and participation in CFM. In order to be able to understand how to promote engagement in forest management, we focused on the extent of participation. Thus, this study analyzed the socio-economic factors that influence NTFP income and participation.

Variables

Pertinent data was collected by using a questionnaire specifically designed for this purpose. Interviews were conducted with 159 household heads and/or the representatives who engaged in NTFP utilization. The following socio-economic data and opinions regarding CFM were also obtained:

NTFP income: Income of a household obtained by collecting and utilizing NTFPs: edible plants, wild fruits, medicinal plants, fuelwood, mushrooms, honey and insects, small animals, fibers, and extractives (Jarernsuk et al. Citation2015; Larpkerna et al. Citation2017; Mianmit et al. Citation2017).

Community forest management (CFM): The four components of CFM effectiveness are generally identified in ‘Framework’ above. The degree of people’s engagement in the community forest project as demonstrated by an analysis of these four components evidences the success and/or effectiveness of CFM. A more detailed explanation of each of these four components and their specific focuses is reflected in .

Socio-demographics: Previous studies have found that certain personal and household demographics are related to the amount of NTFP income and participation in CFM (Lise Citation2000; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Heubach et al. Citation2011; Mutenje et al. Citation2011; Kar and Jacobson Citation2012; Bahdur et al. Citation2013; Melaku et al. Citation2014; Schaafsma et al. Citation2014; Musyoki et al. Citation2016; Aminu et al. Citation2017; Suleiman et al. Citation2017; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019a, 2019b; Zang, et al. Citation2019). The 10 factors selected as variables are: gender, age, marital status, household status, education levels, number of household members, main occupation, household income, land ownership, and land rental.

Table 1. Components CFM effectiveness.

Hypotheses

Based on the conceptual framework of the study, the following two hypotheses were developed.

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive relationship between NTFP income and CFM

NTFP income is expected to positively correlate with effective forest management. Benefitting from forest biodiversity plays an important role in encouraging participation in forest management, supplementing household incomes, and contributing to the overall effectiveness of CFM. Greater engagement in CFM will expand the opportunities for increased NTFP income while increased income will ultimately incentivize CFM development.

Hypothesis 2: Socio-economic factors influence NTFP income and participation in CFM

Previous studies have shown that various factors could influence the utilization of resources and forest management. Our study emphasized two dependent variables: (1) dependency on NTFPs for income and (2) participation in CFM ().

Table 2. Variable descriptions and expected socio-economic factors’ impact on NTFP income and participation in CFM.

We expected that some socio-economic factors would be indicators of NTFP income and the degree of participation. For instance, older people have a higher level of NTFP extraction than younger people due to their experience in doing so (Heubach et al. Citation2011; Mutenje et al. Citation2011). Because gathering NTFPs is difficult labor and physically taxing, males have higher NTFP income than females (Schaafsma et al. Citation2014; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019a). Being married is positively correlated with NTFP income (Aminu et al. Citation2017). Household heads gathered NTFPs less than non-heads of households (Tugume et al. Citation2015). NTFP utilization is likely to decrease as education levels increase; those with less education have more limited employment opportunities prompting a reliance on forest resources (Heubach et al. Citation2011; Mutenje et al. Citation2011; Kar and Jacobson Citation2012; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019a). Larger households are more likely to engage in NTFP extraction because they have more available labor to do so (Babulo et al. Citation2008; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Aminu et al. Citation2017; Suleiman et al. Citation2017). A main occupation as a laborer or a merchant positively correlates with NTFP utilization (Mutenje et al. Citation2011). Household income was also expected to relate to income derived from NTFPs; a lack of a secure income source created a need to otherwise enhance household income (Kar and Jacobson Citation2012; Melaku et al. Citation2014). Land ownership was related to NTFP income; non-landowners tended to engage more in NTFP collection for subsistence because of insufficient crop harvestings (Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019a).

In terms of CFM participation, we expected that females would take part in management activities more than males (Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Musyoki et al. Citation2016). Enhanced age and its concomitant impact on physical strength resulted in less participation (Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Zang et al. Citation2019). Those who are married would have greater opportunity and participate to a higher degree than a single person who is solely responsible for the household (Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011). The head of a family, who is more concerned with sources of income and more prominent in household decision making, participates more (Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011). Those with higher levels of education will be more involved as they are more informed and generally have a longer-term vision (Bahdur et al. Citation2013; Musyoki et al. Citation2016). The number of household members is also related to the level of participation as larger families have more potential workers that can be involved in CFM (Lise Citation2000; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Bahdur et al. Citation2013). Households in which the main occupation was a farmer are positively correlated with participation in CFM (Lestari et al. Citation2015). Higher income families are likely to have greater participation in social forest activities because they are more acutely aware of the fatal consequence of deforestation (Dolisca et al. Citation2006). However, those who owned land participated less than renters whose interest in acquiring land use rights prompts more involvement in CFM (Dolisca et al. Citation2006).

Data collection

Forest survey and sample plot selection

A field survey was conducted from July to October 2018. The goal of the survey was to assess the plant species diversity in the community forest. This research utilized the results of a study conducted in the same area by the RFD in 2016 to calculate the sampling intensity with a confidence probability of 95% (RFD Citation2017). This provided an estimate of sample plots using the standard deviation obtained from previous samplings of similar populations (Avery and Burkhart Citation1983; Asrat and Tesfaye Citation2013). The formula used to calculate sampling intensity is:

(1)

(1)

where n is the sampling intensity; Z is the z-value for confidence interval of 95%;

is the standard deviation for density of tree species; and E is the % acceptable level of sampling error.

The result indicated that 25 sampling plots were representative of the total area. Thus, 0.1% of the total forest inventory was sampled and surveyed using a systematic sampling method (ANSAB Citation2010). Sample plots of 40 × 40 m (0.16 ha) were established. In each plot, trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥4.5 cm were measured and identified in 10 × 10 m subplots. Saplings with a DBH <4.5 cm and height >1.30 m were also measured and identified in 4 × 4 m subplots. In addition, within each plot, 1 × 1 m subplots were laid and all seedlings were identified and counted.

Household survey

Interviews were conducted to gather information regarding how the households utilized NTFPs and to evaluate their participation in CFM. In addition, the survey sought to ascertain households’ opinions about forest management, as well as their perception of the effectiveness of regulations and benefit sharing by the community.

Proportional allocation was used for the sample size determination using the formula proposed by Yamane (Citation1967). The formula is:

(2)

(2)

where n is the sampling to be estimated; N is the number of households;

is the significance level (0.05).

Based on 265 community households, the calculation showed that 159 households provided sufficient sampling intensity for the household interview.

Three types of questions were developed for the questionnaire: (1) requests for specific demographics, (2) multiple choice (single/multiple answers and Likert scales), and (3) open-ended. The questionnaire comprised three sections related to: (1) socio-demographics, (2) NTFP utilization, and (3) community forest management.

Data analysis

In order to assess species diversity and their current status, plants were classified into species, genera, and families. Species classification was based on binomial nomenclature (DNP Citation2014). The habit of the plants was classified as tree, shrub, shrubby tree, herb, climber, etc. In addition, specimens of initially unknown species were eventually identified by comparing them with known specimens in the Herbarium of Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. Referencing the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Citation2019), the statuses of identified plant species were classified as vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered, and the species’ population numbers in the region were also investigated. Moreover, the plant species were categorized based on how they were used as NTFPs in Thailand as food, medicine, fuelwood, fiber, or as an extractive product.

Representatives of 159 households were interviewed in order to determine the nature and extent of NTFPs collected and utilized. Descriptive statistics were used to explain the socio-demographics. The total net return and economic value of the NTFPs obtained from the forest were estimated based on utilization and income from sale in local markets in one year. An opportunity labor cost of 300 baht/day (US $9.68) was used to calculate the value of the time involved in NTFP collection. Transportation costs incurred in collecting NTFPs were also considered in determining net returns using this formula (Tejaswi Citation2008):

(3)

(3)

where Pi is the price of the good; i is the counter of NTFPs;

is the quantity of goods collected by households h; W is the wage rate;

is the hours worked by households h;

is the transportation costs used by households h.

The classification of household income was categorized into four quartiles based on household income from least to highest: first quartile (Q1 < 25th percentile), second quartile (Q2 < 50th percentile), third quartile (Q3 < 75th percentile), and fourth quartile (Q4 > 75th percentile). The household’s relative dependence on NTFP income was measured in each quartile by calculating the percentage of household income derived from the NTFPs. The Gini index of inequality was used to compute the difference in benefit sharing of NTFP income in the community:

(4)

(4)

where

is the number of samples;

is the NTFP income of households.

The survey data regarding the effectiveness of CFM was analyzed and measured on a 5-level Likert scale. The minimum and the maximum length of the Likert scale were broken down into equal mean intervals of 0.80 in the 5 levels in order to provide a weighted mean in efficiency of CFM. The interpretation is as follows:

A Spearman Rho coefficient correlation was performed to analyze the correlation between NTFP income and CFM using the equation:

(5)

(5)

where

is the Spearman rank correlation;

is the difference between the ranks of variables; n is the number of observations.

In addition, a multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between variables to determine the key factors affecting NTFP income and participation in CFM using the following:

(6)

(6)

where

is the dependent variable NTFP income or CFM participation;

is the intercept;

is the regression coefficient in the population;

are the independent variables: gender, age, marital status, household status, educational levels, number of household members, main occupation, household income, land ownership, rented land, and

is an error or residual.

All statistical calculations were performed using R program version 3.6.2 for Windows software (R Development Core Team Citation2019).

Results

Current status of plant species diversity and NTFPs in the community Forest

The inventory of the area in this study yielded a total of 18,567 trees comprising 197 species, 144 genera, and 62 plant families: 129 tree, 99 sapling, and 141 seedling species were identified. Of these, 160 plant species have been classified as having medicinal used, 89 are used as food, 37 as extractive products, 32 as fuelwood, and 12 as fibers. These NTFPs are grouped into categories shown in Appendix 1.

Twenty-six plant species were classified and listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species with seven of these species also listed therein as experiencing a decreasing population. In addition, nine species were reported to have ≤10 stems, 20 species were listed as of Least Concern (LC) including these 7 species with ≤10 stems Casearia grewiifolia, Cassia fistula, Dalbergia cana, Holarrhena pubescens, Oxystelma esculentum, Siphonodon celastrineus, and Vitex pinnata. Two species, Chukrasia tabularis and Globba winitii, were listed as having a decreasing population. The Red List classification also showed four species that were Near Threatened (NT) with decreasing populations: Dalbergia cultrata, Dipterocarpus obtusifolius, Dipterocarpus tuberculatus, and Shorea obtusa. Moreover, Dalbergia oliveri is an Endangered (EN) species with a very high risk of extinction in the wild. Additionally, Cycas siamensis is considered Vulnerable (VU) with a decreasing population and highly likely to become endangered if its main threats persist ().

Table 3. Current status of plant species in the community forest.

NTFP extraction and income

Socio-economics of the respondents

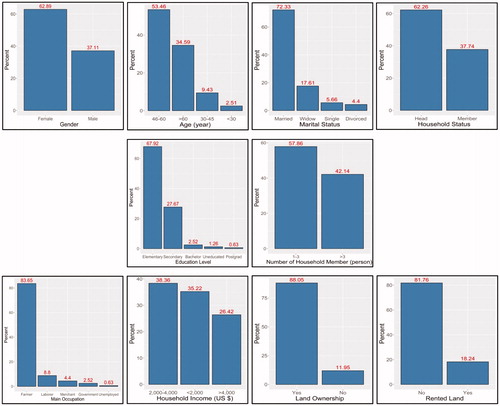

The socio-economics are presented in . The majority of the respondents (62.89%) were female. The respondents ranged from 26 to 86 years old with an average age of 57. Most respondents were married (72.33%). About 17.61% reported as widowed and 5.66% as single. Fewer than 5% of the respondents were divorced. About 62.26% of the respondents were heads of household and 37.74% were other household members. Most respondents had a primary school education (67.92%), followed in decreasing order by secondary school (27.67%), bachelor’s degree (2.52%), non-educated (1.26%), and post-graduate (0.63%). Most families (57.86%) had 1–3 people while 42.14% of families had more than 3 members. Being a farmer was listed as the most common primary occupation (83.65%), while 8.80% of respondents were laborers, 4.40% were merchants, 2.52% were government officials or company employees, and 0.63% were unemployed. Household incomes ranged from US $348.39 to US $46,212.90, while the mean was US $3,587.79. The vast majority of respondents were landowners (88.05%) and did not rent land (81.76%).

NTFP utilization and economic value

In 2018, 109 households collected NTFPs from the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest. An average household gathered NTFPs 22.55 times per year and 3.89 h were expended each time. The average distance traveled to collect NTFPs was 4.69 km/time. The total net return to these 109 households was estimated to be US $36,215.15 (1,122,670 baht) (). When comparing income with the cost of collection, mushrooms provided the highest percentage of net return (73.47%) followed in descending order by wild fruits (14.93%), small animals (6.04%), edible plants (3.18%), and honey keeping and insect collection (2%). Data regarding other NTFPs such as medicinal plants, firewood, fibers, and extractives were not included as their value was insignificantly low or, in the case of extractives, were not collected for household use. If the benefit were shared among these households, each would receive an average of US $227.76 (7,060.82 baht) per year. The total value of the consumption and sale of NTFPs accounted for 6.35% of the total annual income of the community (US $60,358.62 or 1,871,117.30 baht).

Table 4. Total net NTFP income return from Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest in 2018.

Benefit sharing of NTFP income in community

A comparison of mean household income and NTFP income by income quartile is reflected in . It demonstrates that, regardless of income level, the household obtained additional income through NTFPs. The mean NTFP income varied somewhat between quartiles (US $85.23–US $307.93). The lower income quartiles (Q1 = 7.34%, Q2 = 12.38%, and Q3 = 8.89%) experienced a much larger percentage of income boost (9.54% average) from NTFPs than the highest income quartile (Q4 = 3.37%). The Gini coefficients also reflect that the degree of inequality in NTFP income between households in the community was 71.98%. Upon comparison of the income quartiles, it can be seen that there was also a high degree of inequality.

Table 5. Mean comparison between NTFP income and household income.

Effectiveness of CFM

The effectiveness of CFM in this study was reflected in results plotted on a Likert scale with 5 levels: ‘very high’ = 5 points (4.21–5.00), ‘high’ = 4 points (3.41–4.20), ‘moderate’ = 3 points (2.61–3.40), ‘low’ = 2 point (1.81–2.60), and ‘very low’ (1.00–1.80). presents a mean of respondents’ opinions regarding, and participation levels in, CFM. Overall, people were highly engaged (3.92). The enforcement of community forest regulations, the perception and understanding of people in managing their forest resources, and benefits derived from forest biodiversity of the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest were reported as ‘very high’ (4.40, 4.75, and 4.61, respectively), while the overall involvement of people in forest management activities was ‘high’ (3.55). Participation, specifically in forest activities, and in sharing benefits were ‘high’ (3.76 and 3.82). However, participation in decision-making (3.35) and in monitoring and evaluation (3.03) were at a ‘moderate’ level. Overall, the level of involvement was ‘high’ (3.55).

Table 6. Effectiveness of CFM and level of participation.

The relationship between NTFP income and CFM

The Spearman’s Rho correlation coefficients (r = 0.524) show in that NTFP income and CFM were significant (p ˂ 0.001). This indicates that there is a positive relationship between NTFP income and the effectiveness of CFM. Income from NTFPs was positively associated with the level of participation (r = 0.522), community forest regulations (r = 0.269), and benefit sharing (r = 0.279). However, NTFP income was not significantly correlated with perception and understanding.

Table 7. Correlations (Spearman) between NTFP income and CFM (n = 159).

Socio-economics affecting NTFP income and participation in CFM

The Multiple Linear Regression was analyzed to determine how certain socio-economic factors were related to NTFP income and CFM participation. The ten demographics shown in were included in the model. In this study, a stepwise Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to choose the best-fit model.

The multiple regression model with predictors showed that some factors significantly affect NTFP income (R2 = 0.118, p ˂ 0.01). Main occupations reported as ‘laborers’ and ‘merchants’ had notable negative impact on NTFP income, denoting an expectation of lower NTFP income. People with low income also had a similar negative effect on NTFP extraction and were likewise expected to have low NTFP income ().

Table 8. Multiple linear regression for variables predicting NTFP income (n = 109).

An analysis of how socio-demographics affect participation in CFM also found that the multiple regression model was highly significant (R2 = 0.159, p ˂ 0.001). A single person, household head, someone who attained a bachelor’s degree, and low-income households had consequential negative effects on participation suggesting that they were expected to engage less in CFM. Conversely, people who owned land had significant positive effect on participation leading to an expectation of higher CFM engagement ().

Table 9. Multiple linear regression for variables predicting participation in CFM (n = 159).

Discussion

Plant species diversity and sources of NTFPs

The Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest is the source of a vast array of NTFPs. At least 160 species can be used for medicinal purposes, 89 for food, 37 for extractive production, 32 as fuelwood, and 12 for fiber (Appendix 1). This was consistent with findings in other studies wherein it was found that forest biodiversity could assist to meet basic needs while otherwise enhancing livelihoods and generating income (Kim et al. Citation2008; Kumar Citation2015; Rijal et al. Citation2019).

Deciduous forests are important tropical dry forests with the potential to provide services to rural communities in remote areas (Kabir and Webb Citation2006; Chaiyo et al. Citation2011; Thammanu and Caihong Citation2014; Larpkerna et al. Citation2017). Nearly one-fifth of Thailand’s forest area is covered by deciduous forests (RFD Citation2019). Consequently, they play a critical role in providing NTFPs to nearby communities.

Though they presently have high populations and are accessible to support local livelihoods, 26 plant species found in this study were listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (). Six species were listed as LC: Chukrasia tabularis, Globba winitii, VU: Cycas siamensis and NT species: Dipterocarpus obtusifolius, Dipterocarpus tuberculatus, and Shorea obtusa. Even though their numbers in the community forest were not low, their regional populations were decreasing according to the IUCN report. Moreover, Dalbergia cultrata was designated as NT as a result of having a low and decreasing population both in the community forest and region-wide. This suggests that protecting these species should be prioritized for conservation.

In addition, nine plant species had a population of 10 or less stems including critical species Dalbergia oliveri (EN). Further, Cycas siamensis (VU) is an ornamental plant species that has been over-exploited in Thailand due to increasing demand for it as garden decoration. Thus, it is urgent for a strategic plan of forest management to maintain plant species and monitor NTFP utilization.

Utilization of NTFPs for rural livelihoods

Most households in the community relied on NTFPs for food, medicine, fuelwood, and fibers (). This was similar to the findings of previous studies that people in Thailand rely on NTFPs for their living in various ways (Jarernsuk et al. Citation2015; Larpkerna et al. Citation2017; Mianmit et al. Citation2017). The estimated value of NTFPs collected and utilized as cash income or for other subsistence during the study period was US $60,360. This highlights the role of NTFPs in supporting rural communities (ONEP Citation2004; Witchawutipong Citation2005; ITTO Citation2006).

Naturally, different NTFPs provided different levels of income. Mushrooms and wild fruits were the most valuable providing higher monetary value. Lower household income tended to obtain a higher income from NTFPs than higher household income (). This suggests that the economic status of a household influences the level of NTFP extraction and production. Therefore, the result of this study supports the proposition that NTFP utilization enables lower income households to improve their living condition, as shown in other studies (Blair and Olpadwala Citation1988; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Mulenga et al. Citation2011; Kar and Jacobson Citation2012; Sharma et al. Citation2015; Tugume et al. Citation2015).

This study also revealed that it has a very diverse composition of species, especially of those used for medicine and foods (Appendix 1). However, this research found that NTFP usage levels of various plant species were very low when compared to the available NTFPs () indicating a greater potential for NTFP utilization for increased improvement of livelihoods.

NTFPs provided food, served other daily functions, and generated sales income which accounted for 6.35% of the total annual household income. Compared to the other case studies in developing countries (Angelsen et al. Citation2014), this percentage of income was low. In Zambia, it was estimated to be 34% of the total household income (Saifullah et al. Citation2018), in Northern Benin it was 39% (Heubach et al. Citation2011) and in Myanmar, it accounted for 44.37% of the total household income (Liu and Moe Citation2016). A study in Malaysia reported that NTFPs contributed 24% of total annual household incomes (Mulenga et al. Citation2011). This research showed that a potential for greater income exists and enhancing forest biodiversity to provide a larger and ongoing supply of NTFPs is needed. In addition, the Gini coefficient reflected a high level of inequality between income quartiles and households. This suggests that the benefit sharing of NTFPs varied disproportionally in the community.

Implication of CFM in the community Forest

People were generally engaged and involved in the implementation of CFM at the high level (). However, involvement in decision making, a key process in managing local forest resources, was limited. This study suggests that Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum should prioritize participation, especially in decision making, and identify it as fundamentally important for successful forest management (Blair and Olpadwala Citation1988; Pragtong Citation1995).

Community involvement in monitoring and evaluation of CFM was at the moderate level which indicated that it could be an obstacle to more collaborative forest management. A lack of thorough monitoring and evaluation of the utilization of NTFPs could have a detrimental impact on species diversity and the ongoing supply of varied and numerous NTFPs.

Linkage between NTFP income and CFM

NTFP income levels had an impact on and were related to the effectiveness of CFM (). As such, more NTFP income can lead to increased effectiveness. This is in line with previous studies that supported the proposition that higher dependency on the forest induced higher participation and, as a result, more effective management (Lise Citation2000; Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007; Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011; Tugume et al. Citation2015; Soe and Yeo-Chang Citation2019b).

Concomitantly, higher engagement and improved CFM could create income opportunities and improve living condition. This study also showed that income from NTFPs was closely related to the enforcement of regulations and benefit sharing. Thus, if regulations are enforced and the benefits are shared equitably, everyone can realize higher NTFP income.

According to Ostrom et al. (Citation1994) and Ostrom (Citation2005), a forest system can be influenced by three factors: natural attributes, economic attributes, and rules. If there is CFM in a community, it denotes that formal rules governing forest management exist and forestry activities conform to those rules. With proper rules and design, forestry activities could have a positive impact on rural livelihoods and community forest improvement. The results indicate the relationship between NTFP income and CFM effectiveness.

Socio-economics that influence NTFP income

Income from NTFPs was influenced by various socio-economic factors. As reflected in , the main occupation and income level were characteristics that impacted NTFP income. Laborers and merchants were negatively related to NTFP extraction. However, this result is not consistent with the findings in a previous study that those primary occupations positively correlate with NTFP utilization (Mutenje et al. Citation2011).

Recently in rural Thailand, off-farm employment has become more available to provide income opportunities for poor people. This is partly because the 2018 government wage policy increased the minimum wage to 300 baht per day. Generally, workers can find jobs in their villages or in nearby cities. Higher wages as a laborer or profits from business could exceed income derived from NTFPs. Consequently, off-farm employment opportunities could reduce NTFP dependence and the resulting pressure on forests (Angelsen and Kaimowitz Citation1999; Suleiman et al. Citation2017).

In addition, our estimated model showed that lower income households (<US $2,806.45) were negatively correlated with NTFP extraction, implying less interest in NTFP extraction. Kar and Jacobson (Citation2012) revealed that lacking wage labor in agriculture or other employment or lacking in general income security could prompt NTFP collection. Contrary to the previous findings, our study found that people in low-income households would have more incentive to seek higher wage farm or other employment rather than focus on NTFP collection. A possible reason is that collecting NTFPs has a high opportunity cost of labor which is estimated at 78% of total costs incurred in collecting NTFPs (). Also, higher-income households could have access to more resources and more opportunities to access NTFPs than lower-income households (Ezebilo and Mattsson Citation2010).

Socio-economics that influence participation in CFM

Different socio-demographics also affected the level of participation (). Our model illustrates that marital status, the role in the family, educational levels, household income, and land ownership are key factors that influence participation.

For instance, participation was lower for single people as they generally had responsibilities at home with less family members to share those responsibilities, thereby limiting the time available to take part in outside activities (Coulibaly-Lingani et al. Citation2011).

Household heads were less likely to participate arguably due to having greater responsibility to provide financially and otherwise for the family. It was similarly observed by Okumu and Muchapondwa (Citation2017) that household heads employed in off-farm jobs were less actively engaged in collective management of forest resources.

Household income had an impact on participation. Our results are in-line with previous studies that suggest wealthier households are more likely to participation in forest management (Atmiş et al. Citation2007; Dolisca et al. Citation2006; Musyoki et al. Citation2016; Apipoonyanon et al. Citation2020). Members of lower income households may find it difficult to spend time on social forestry activities due to household economic pressure to engage in additional work to increase income. Thus, low income can be a factor that reduces participation in CFM.

Those who attain a higher level of education have greater opportunities for better paying jobs and are generally more involved in off-farm and off-forestry activities (Jumbe and Angelsen Citation2007; Lestari, et al. Citation2015). The result of this study showed that respondents with a bachelor degree participated less than those with lower levels of education.

Unexpectedly, land ownership shows a positive relationship to CFM participation. This indicated that landowners are more likely to be engaged in community forest activities than those who were landless. It was similarly observed in several studies that security of tenure contributed to increased participation in public programs (Zhang and Owiredu Citation2007; Musyoki et al. Citation2016; Zang, et al. Citation2019). A possible explanation could be that people who owned land are more concerned about the benefits of the community forest to their agriculture lands. This idea that farmers are more closely involved is consistent with the findings of Lestari et al. (Citation2015) and Apipoonyanon et al. (Citation2020). Thus, land tenure status influences participation in CFM (Atmiş et al. Citation2007).

Conclusions

This study identified the diversity of plant species in the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest and the current status of these species. In addition, how NTFPs were utilized and how the local residents contributed to the management of the forest to enhance their livelihoods and to biodiversity conservation were also determined. Socio-demographics of the households were analyzed to understand the people in the community in the context of sustainable forest management.

Based on the results of this study, we have the following insights into improving forest management to improve living condition and conserve the biodiversity of the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest:

The community forest’s remarkable diversity plays an important role in providing NTFPs. NTFPs from the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest supported livelihoods through CFM. However, 26 species were listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 7 of which were listed as experiencing decreasing populations. In addition, a very low number of stems of 9 additional species were recorded in the community forest. The status of these NTFP-providing species is concerning because of these numbers. The continued extraction of NTFPs should be strictly monitored and the harvesting of threatened or species at risk of becoming threatened should not go unchecked.

NTFP utilization in the community forest tends to improve household economy of lower income households. However, lower income families are less likely to have competitive access to forest resources than higher income families. Hence, efforts to facilitate and promote lower income household NTFP utilization should be enhanced. In addition, there should be a focus on ensuring a more equitable sharing of the benefits.

Receiving NTFP income leads to contribution to the management of community forest. Contribution leads to effectiveness which can create opportunities for more income. A relationship exists between NTFP dependence and the effectiveness of community forest management for the benefit of all; this is a relationship that should be demonstrated and used to prompt more participation in CFM.

Participation in CFM and income derived from NTFPs are related to certain demographics. A single person, a head of the family, someone with a bachelor’s degree, and low income families tend to participate less. To improve overall participation, there should be a focus on those with these demographics. Furthermore, strategies to prompt the involvement in monitoring and evaluation activities as well as in the decision-making process should be developed.

However, this study is limited in that only the plant species used as NTFPs in the subject region were considered. The other NTFPs such as mushrooms, honey, and insects were not included in the analysis. Thus, future study should investigate NTFP utilization of these NTFPs in the community forest to obtain additional data to support more effective forest management.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Asian Forest Cooperation Organization (AFoCO) and the Royal Forest Department (RFD) for the opportunity to pursue this project. Finally, this research would not have been possible without the assistance of the village leaders and people of Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amgrose-Oji B. 2003. The contribution of NTFPs to the livelihoods of the ‘forest poor’: evidence from the tropical forest zone of south-west Cameroon. Int Rev. 5:106–117.

- Aminu SA, Ibrahim Y, Ismail HA. 2017. Assessment of economic benefits of NTFPs in Southern Kaduna, Kaduna State, Nigeria. J Sci Environ. 2:30–35.

- Angelsen A, Jagger P, Babigumira R, Belcher B, Hogarth NJ, Bauch S, Börner J, Smith-Hall C, Wunder S. 2014. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: a global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 64(Suppl 1):S12–S28.

- Angelsen A, Kaimowitz D. 1999. Rethinking the causes of deforestation: lessons from economic models. World Bank Res Obs. 14(1):73–98.

- ANSAB. 2010. Participatory inventory of non-timber forest products. Kathmandu: ANSAB.

- Apipoonyanon C, Kuwornu JKM, Szabo S, Shrestha RP. 2020. Factors influencing household participation in community forest management: evidence from Udon Thani Province, Thailand. J Sustain For. 39(2):184–206.

- Asrat Z, Tesfaye Y. 2013. Training manual on: forest inventory and management in the context of SFM and REDD+. Wondo Genet: Hawassa University.

- Atmiş E, Daşdemir İ, Lise W, Yıldıran Ö. 2007. Factors affecting women’s participation in forestry in Turkey. Ecol Econ. 60(4):787–796.

- Avery TE, Burkhart HE. 1983. Forest measurements. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- Babulo B, Muys B, Nega F, Tollens E, Nyssen J, Deckers J, Mathijs E. 2008. Household livelihood strategies and forest dependence in the highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Agric Syst. 98(2):147–155.

- Bahdur B, Chhetri K, Johnsen FH, Yoshimoto A. 2013. Community forestry in the hills of Nepal: determinants of user participation in forest management. Forest Policy Econ. 30:6–13.

- Blair HW, Olpadwala PD. 1988. Forestry in development planning: lessons from the rural experience. London: Westview Press.

- Chaiyo U, Garivait S, Wanthongchai K. 2011. Carbon storage in above-ground biomass of tropical deciduous forest in Ratchaburi Province. Thailand. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 58:239–260.

- Chechina M, Neveux Y, Parkins JR, Hamann A. 2018. Balancing conservation and livelihoods: a study of forest-dependent communities in the Philippines. Conservat Soc. 16(4):420–430.

- Chen H, Zhu T, Krott M, Maddox D. 2013. Community forestry management and livelihood development in northwest China: integration of governance, project design, and community participation. Reg Environ Change. 13(1):67–75.

- Coulibaly-Lingani P, Savadogo P, Tigabu M, Oden P-C. 2011. Factors influencing people’s participation in the forest management program in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Forest Policy Econ. 13(4):292–302.

- DNP. 2014. Thai plant names Tem Smittinand. Bangkok (in Thai): Forest Herbarium, DNP.

- DNP. 2017. Threatened plants in Thailand. Bangkok: Forest Herbarium, DNP

- Dolisca F, Carter DR, McDaniel JM, Shannon DA, Jolly CM. 2006. Factors influencing farmers’ participation in forestry management programs: a case study from Haiti. For Ecol Manag. 236(2–3):324–331.

- Ezebilo EE, Mattsson L. 2010. Contribution of non-timber forest products to livelihoods of communities in Southeast Nigeria. Int J Sust Dev World. 17(3):231–235.

- Gilmour D, Malla Y, Nurse M. 2004. Linkages between community forestry and poverty. Bangkok: RECOFTC.

- Heubach K, Wittig R, Nuppenau E-A, Hahn K. 2011. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: a case study from Northern Benin. Ecol Econ. 70(11):1991–2001.

- ITTO. 2006. Achieving the ITTO objective 2000 and sustainable forest management in Thailand: Report of the diagnostic mission. ITTO. [accessed 2018 June 20]. https://www.itto.int/direct/topics/topics_pdf_download/topics_id=3,12,70,000&no=1&disp=inline

- Jarernsuk S, Petchsri S, Poolprasert P, Wattanadumrong B. 2015. Economic value of non-timber forest products used by the largest Hmong community in Thailand. NU Int J Sci. 12:38–51.

- Jumbe CBL, Angelsen A. 2007. Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecol Econ. 62(3–4):661–672.

- Kabir ME, Webb EL. 2006. Saving a forest: the composition and structure of a deciduous forest under community management in Northeast Thailand. Nat Hist Bull Siam Soc. 54:239–260.

- Kar SP, Jacobson MG. 2012. NTFP income contribution to household economy and related socio-economic factors: lesson from Bangladesh. Forest Policy Econ. 14(1):136–142.

- Kim S, Sasaki N, Koike M. 2008. Assessment of non-timber forest products in Phnom Kok community forest, Cambodia. Asia Europe J. 6(2):345–354.

- Kumar V. 2015. Impact of non timber forest produces (NTFPs) on food and livelihood security: an economic study of tribal economy in Dang’s District of Gujarat. Int J Agric Environ Biotechnol. 8(2):387–404.

- Larpkerna P, Eriksen MH, Waiboonya P. 2017. Diversity and uses of tree species in the deciduous dipterocarp forest, Mae Chaem District, Chiang Mai Province, Northern Thailand. NUJST. 25:43–55.

- Lestari S, Kotani K, Kakinaka M. 2015. Enhancing voluntary participation in community collaborative forest management: a case of Central Java, Indonesia. J Environ Manage. 150:299–309.

- Liang J, Crowther TW, Picard N, Wiser S, Zhou M, Alberti G, Schulze E-D, McGuire AD, Bozzato F, Pretzsch H, et al. 2016. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science. 354(6309):aaf8957.

- Lise W. 2000. Factors influencing people’s participation in forest management in India. Ecol Econ. 34(3):379–392.

- Liu J, Moe KT. 2016. Economic contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to rural livelihoods in the Tharawady District of Myanmar. Int J Sci. 5:12–21.

- Melaku E, Ewnetu Z, Teketay D. 2014. Non-timber forest products and household incomes in Bonga forest area, Southwestern Ethiopia. J Res. 25(1):215–223.

- Mianmit N, Jintana V, Sunthornhao P, Kanhasin P, Takeda S. 2017. Contribution of NTFPs to local livelihood: a case study of Nong Sai Sub-district of Nang Rong District under Buriram Province in Northeast Thailand. J Agrofor Environ. 11:123–128.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. Washington DC: World Resource Institute.

- MPSAO. 2018. Population in the Mae Phrik Subdistrict Administrative Organization. Lampang (in Thai): MPSAO.

- Mulenga B, Richardson R, Mapemba L, Tembo G. 2011. The contribution of non-timber forest products to rural household income in Zambia. East Lansing, MI: Department of Agriculture, Food, Resource and Economics, Michigan State University.

- Murali KS, Shankar U, Shaanker RU, Ganeshaiah KN, Bawa KS. 1996. Extraction of non-timber forest products in the forests of Biligiri Rangan Hills, India. 2. Impact of NTFP extraction on regeneration, population structure, and species composition. Econ Bot. 50(3):252–269.

- Musyoki JK, Mugwe J, Mutundu K, Muchiri M. 2016. Factors influencing level of participation of community forest associations in management forests in Kenya. J Sustain Forest. 35(3):205–216.

- Mutenje MJ, Ortmann GF, Ferrer SRD. 2011. Management of non-timber forestry products extraction: local institutions, ecological knowledge and market structure in South-Eastern Zimbabwe. Ecol Econ. 70(3):454–461.

- Negi S, Pham TT, Karky B, Garcia C. 2018. Role of community and user attributes in collective action: case study of community-based forest management in Nepal. Forests. 9:136.

- Okumu B, Muchapondwa E. 2017. Determinants of successful collective management of forest resources: evidence from Kenyan Community Forest Associations. South Africa: Working paper 698, Economic Research Southern Africa.

- ONEP. 2004. Thailand environment monitor series. Bangkok: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

- ONEP. 2009. Thailand: National report on the implementation of the convention on biological diversity. Bangkok: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

- Ostrom E. 2005. Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker J. 1994. Rules, games and common-pool resources. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Popradit A, Srisatit T, Kiratiprayoon S, Yoshimura J, Ishida A, Shiyomi M, Murayama T, Chantaranothai P, Outtaranakorn S, Phromma I, et al. 2015. Anthropogenic effects on a tropical forest according to the distance from human settlements. Sci Rep. 5:14689.

- Pragtong K. 1995. Community forestry in Thailand. Bangkok: RFD.

- R Development Core Team. 2019. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- RECOFTC. 2007. Sharing the wealth, improving the distribution of benefits and costs from community forestry: policy and legal frameworks, synthesis of discussions at the second community forestry forum. Bangkok: RECOFTC, FAO and SNV.

- Rew LJ, Medd RW, Van de Ven R, Gavin JJ, Robinson GR, Tuitee M, Barnes J, Walker S. 2005. Weed species richness, density and relative abundance on farms in the subtropical grain region of Australia. Aust J Exp Agric. 45(6):711–723.

- RFD. 2000. Community forest project approval between 2000-present. RFD. [Accessed 30 January 2020]. http://www.forest.go.th/community-extension/2017/02/02/.

- RFD. 2014. Implementation guidelines for community forest projects of the Royal Forest Department. Bangkok (in Thai): RFD.

- RFD. 2017. Study of carbon sequestration and biodiversity in the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest, Northern Thailand. Bangkok (in Thai): RFD.

- RFD. 2019. Executive summary. Bangkok (in Thai): RFD.

- Rijal S, Adhikari S, Pant RR. 2019. Non-timber forest products and livelihood linkages: a case of Lamabagar. Nepal. IJMSIR. 13:326–331.

- Royal Thai Government. 2019. Community Forest Act B.E. 2562. pp. 71–103. Bangkok (in Thai): Royal Thai Government.

- Sagar R, Raghubanshi AS, Singh JS. 2003. Tree species composition, dispersion and diversity along a disturbance gradient in a dry tropical forest region of India. For Ecol Manag. 186(1–3):61–71.

- Saifullah MK, Kari FB, Othman A. 2018. Income dependency on non-timber forest products: an empirical evidence of the indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Soc Indic Res. 135(1):215–231.

- Salam MA, Noguchi T, Pothitan R. 2006. Community forest management in Thailand: current situation and dynamics in the context of sustainable development. New Forest. 31(2):273–291.

- Schaafsma M, Morse-Jones S, Posen P, Swetnam RD, Balmford A, Bateman IJ, Burgess ND, Chamshama SAO, Fisher B, Freeman T, et al. 2014. The importance of local forest benefits: economic valuation of non-timber forest products in the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania. Glob Environ Change. 24:295–305.

- Shanley P, Luz L, Swingland IR. 2002. The faint promise of a distant market: a survey of Belém’s trade in non-timber forest products. Biodivers Conserv. 11(4):615–636.

- Sharma D, Tiwari BK, Chaturvedi SS, Diengdoh E. 2015. Status, utilization and economic valuation of non-timber forest products of Arunachal Pradesh, India. JFES. 31:24–37.

- Soe KT, Yeo-Chang Y. 2019a. Livelihood dependency on non-timber forest products: implications for REDD+. Forests. 10:427.

- Soe KT, Yeo-Chang Y. 2019b. Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: a case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. For Policy Econ. 100:129–141.

- Suleiman MS, Wasonga VO, Mbau JS, Suleiman A, Elhadi YA. 2017. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano. Ecol Process. 6(1):23.

- Sunderlin WD. 2006. Poverty alleviation through community forestry in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam: an assessment of the potential. Forest Policy Econ. 8(4):386–396.

- Tejaswi PB. 2008. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for food and livelihood security: an economic study of tribal economy in Western Ghats of Karnataka, India [Dissertation]. Ghent, Belgium: Ghent University.

- Thammanu S, Caihong Z. 2014. The growing stock and sustainable utilization of white bamboo, Bambusa membranacea (Munro) C.M.A. Stapleton &N.H. Xia in the natural mixed deciduous forest with teak in Thailand: a case study of Huay Mae Hin Community Forest, Ngao District, Lampang Province. Int J Sci. 3:23–30.

- Thapa S, Chapman DS. 2010. Impacts of resource extraction on forest structure and diversity in Bardia National Park. Nepal. For Ecol Manag. 259(3):641–649.

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [Accessed 2019 Sept 29]. https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

- The World Bank. 2001. Sustaining forest: a development strategy. Washington (DC): The World Bank.

- Tugume P, Buyinza M, Namaalwa J, K. Kakudidi E, Mucunguzi P, Kalema J, Kamatenesi M. 2015. Socio-economic predictors of dependence on non-timber forest products: lessons from Mabira Central Forest Reserve Communities. JAES. 4(2):195–214.

- Witchawutipong J. 2005. Thailand community forestry. Bangkok: RFD.

- Yamane T. 1967. Statistics: an introductory analysis. New York: Harper and Row.

- Zang L, Araral E, Wang Y. 2019. Effects of land fragmentation on the governance of the commons: theory and evidence from 284 villages and 17 provinces in China. Land Use Policy. 82:518–527.

- Zhang D, Owiredu EA. 2007. Land tenure, market, and the establishment of forest plantations in Ghana. For Policy Econ. 9(6):602–610.

Appendix 1. List of plant families and the nature of NTFPs in Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest.