?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Forest extraction is an important livelihood activity for millions of low-income households in rural areas of developing countries. Understanding the choices households make to extract forest products can help formulate strategies for preventing livelihood strains associated with forest degradation. This article evaluates the nature, extent and determinants of forest extraction among rural households in western Kenya. Data were obtained from a survey of 924 randomly selected households in the Mt. Elgon area in western Kenya. The level of forest extraction was measured as the aggregate value of products extracted, while a Double Hurdle model was applied to assess the factors influencing forest extraction. The results show that the choice to engage in forest-based livelihood was generally higher among households with lower asset value, membership in forest user associations, and headed by males. The results further show that although the majority of households’ engaging in forest-based livelihood were of the lowest wealth category, households in the middle wealth category were found to extract higher value products. Institutional characteristics, including access to agricultural markets, credit, extension, and membership to forest user groups, increased the likelihood of households’ extracting higher value products. Overall, the results show that in addition to asset endowment, other contextual factors, such as access to markets, agricultural extension, and membership to farmer groups defined whether a household extracted forest products for survival or accumulation.

Introduction

A growing body of research demonstrates the importance of forests as a livelihood source for many rural people in developing countries (Mamo et al. Citation2007; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that about one billion people get a significant share of their incomes from forest extraction (FAO Citation2016). Forest extraction is the process of obtaining forest products that include food, fuelwood, construction materials, and medicinal plants for consumption or sale (Velded et al. Citation2004; Paumgarten Citation2005; Mamo et al. Citation2007). The importance of forests as a source of livelihood is widely recognized by international treaties, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Sustainable Development Goals and the Bonn Challenge in which world leaders agreed to reforest 350 million hectares of land by 2030 (Dave et al. Citation2019).

The recognition that rural households in developing countries diversify their income sources has attracted widespread attention from scholars and policymakers (Mamo et al. Citation2007; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). Most studies reveal that livelihood diversification is critical for decreasing livelihood threats and vulnerability, stabilizing household incomes, and reducing poverty (Fisher Citation2004; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). The literature identifies two broad determinants for household diversification – push and pull factors. The push factors motivate households to extract for survival while pull factors relate to diversification by choice or wealth accumulation (Ellis Citation2000). A wide body of literature, therefore makes a distinction between households who rely on forests because they have no alternative and those who use forests resources as a matter of choice (Mamo et al. Citation2007; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Nielsen et al. Citation2013; Zenteno et al. Citation2013; Melaku Getahun Citation2016). This categorization is based on the idea that poor households engage in forest extraction for survival, while their wealthier counterparts engage for accumulation purposes. This argument suggests that low-asset endowed rural households engage in forest extraction activities to support their current consumption or cope with risks and shocks, such as drought and floods (Nguyen et al. Citation2015). Conversely, better-off households are attracted to extract high-value forest products to enhance their asset endowment (Mango et al. Citation2017). However, some recent studies have challenged these forest user categories by proving evidence to show that some poor households engage in forest extraction by choice to accumulate their wealth (Angelsen et al. Citation2014). There is also evidence showing that some wealthy households engage in forest extraction to support consumption or cope with shocks and risks such as crop failure and livestock epidemics (Melaku Getahun Citation2016). Thus, the empirical evidence of the determinants of forest extraction remains diverse and inconclusive.

Despite this understanding, many previous studies have considered forest users' extraction motives (push or pull) in isolation of each other (Paumgarten Citation2005; Babulo et al. Citation2008; Zenteno et al. Citation2013; Mango et al. Citation2017). A key concern, therefore, is that most previous studies do not take into account heterogeneities in rural household’s contexts based on wealth category, gender, income, or livelihood vulnerability (Uberhuaga et al. Citation2012; Zenteno et al. Citation2013; Thondhlana and Muchapondwa Citation2014). This article responds to this gap by analyzing the nature, extent, and factors influencing forest extraction decisions among rural households in Kenya. The article goes beyond other previous studies by analyzing how the determinants of livelihood diversification vary by different socioeconomic groups. This is essential to inform future forest conservation and livelihood improvement strategies (Wunder et al. Citation2014; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the methodology used while Section 3 presents the findings and discussions. Section 4 presents the conclusions and policy implications.

Materials and methods

Description of the study areas

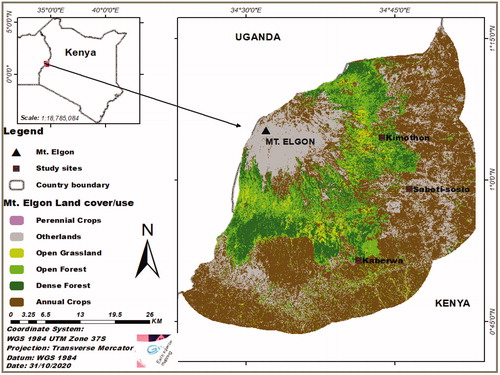

The study was conducted in the Mt. Elgon ecosystem in western Kenya (), an area characterized by high levels of forest dependence, a history of communal forestry and degradation of forest resources due to the high human activities (Mburu et al. Citation2007). The ecosystem is located at the border between Kenya and Uganda (Mburu et al. Citation2007) and at about 100 km north-east of Lake Victoria. Large parts of the ecosystem are gazetted as protected areas, including a montane forest reserve (73,705 ha) under the management of the Kenya Forest Service, a national park (16,916 ha) which is managed by the Kenya Wildlife Service and a nature reserve (17,200 ha) managed by Bungoma County Government. Mt Elgon is also one of Kenya's five main “water towers” – forested upland area which contains many springs and streams that are the sources of major rivers that eventually drain into lakes (FAO Citation2016). The other water towers are Aberdare range, Mt. Kenya, Cherangani hills, and Mau Complex forests. The lower parts of Mt. Elgon ecosystem are inhabited by local communities whose main economic activities are mixed crop and livestock farming (Kaitibie et al. Citation2009).

Analytical framework

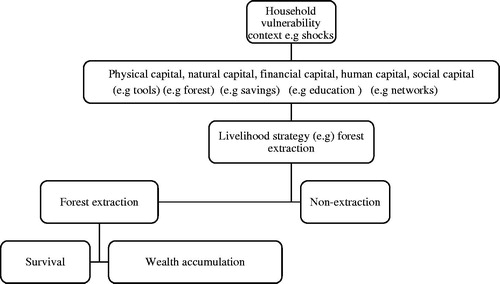

Following the work of Nguyen et al. (Citation2015), this study applies the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) to show the linkage between household assets, livelihood strategies, and outcomes and how they relate to each other (). The SLF consists of three closely connected components: livelihood context and capitals (assets and resources), livelihood strategies, and livelihood outcomes (Scoones Citation1998; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). The vulnerability context refers to factors that affect people’s livelihoods which may include low prices and wages, high transaction costs, market failure, and undeveloped institutions (Nguyen et al. Citation2015). The household assets and resources can be categorized into; physical capital (e.g. distance to the market), natural capital (e.g. land, livestock, and own woodlot), financial capital (e.g. business income), human capital (e.g. educational attainment), and social capital (e.g. membership in social groups). Depending on the vulnerability context and access to the various capital forms, a typical household would pursue varied livelihood options which may include the extraction of environmental resources, such as collection of forest products and fishing (Nielsen et al. Citation2013). The livelihood strategy selected by the household leads to a set of livelihood outcomes which would be survival or wealth accumulation. Hence, this framework offers a foundation for broadly understanding the determinants of forest extraction actions among rural households (Nguyen et al. Citation2015).

Figure 2. The Sustainable Livelihood Framework showing the linkage between household assets and livelihood strategies. Source: Adopted from the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (Nguyen et al. Citation2015).

Data and sampling

The study employed a three-stage procedure for data collection following (Do et al. Citation2019). At the first stage, we selected three forest stations to represent the different administrative areas across the Mt. Elgon catchment and proximity to the forest. At the second stage, we purposefully sampled 30 villages within five kilometers of the forest boundary. Lastly, we then randomly selected 924 forest-dependent households proportionate to the village’s population. The field survey to collect the data took place between November 2018 and January 2019. The questionnaire used in conducting household interviews contained information on household capital endowment, household choices on forest extraction, the types of forest products extracted, and level of extraction and various socioeconomic variables. A description of the variables applied in the study is provided in .

Table 1. Description of variables and measurement.

Estimation strategy

The study analyzed forest-based livelihood and their determinants in two stages. In the first stage, descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the nature and type of forest products extracted. The intensity of forest extraction was measured in terms of the sum of the value of forest products collected. The value of forest products was derived from their market prices and actual costs (e.g. transportation costs or fee payable) incurred in extraction. The value and type of products extracted (firewood, wild vegetables, fruits, and honey) were categorized by wealth groups in order to provide understanding of how extraction varies with income and socioeconomic economic circumstances of the household. Following the works of Nguyen et al. (Citation2015), the households were grouped into wealth categories based on their household assets. This was done using a wealth index generated from principal component analysis (PCA). In this procedure, the wealthy category composed of those households with a wealth index above the mean value and the standard deviation. The middle group included households with a wealth index within the mean and standard deviation. The poor group composed of households with a wealth index below the mean and standard deviation.

In the second step, the study applied Cragg’s Double Hurdle model to identify the factors influencing forest extraction. The choice of the model was based on the assumption that the household’s forest extraction decisions follow a two-step sequential process. First, a household chooses whether to extract forest products or not. Second, a household then decides the intensity at which to engage in forest extraction. The model combines both a binary Probit with a Tobit model (EquationEqs. (1–3)), which allows the simultaneous analysis of two sequential household decision on forest extraction:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

where

is the decision to engage in forest-based livelihood activities while

is a vector of variables such as socioeconomic characteristics, demographic characteristics, asset endowment, institutional characteristics, and shocks hypothesized to influence the household forest extraction decisions. The intensity of forest extraction is denoted by

while

is vector representing the parameters to be estimated, and ε is the error term.

Results and discussion

Description of household profile

shows differences between households engaging in forest extraction (participants) and those who do not (non-participants). Compared to non-participants, participants of forest-based livelihood options are more likely to be younger, with lower levels of education, involved in farming as the main occupation, low asset value, lower incomes, and face severe shocks. However, the results show that there are no significant differences between participants of forest-based livelihoods and non-participants concerning a number of household characteristics (household size, gender, and land size), transaction costs (distance to forests, distance to markets distance to all-weather roads), access to credit facilities, expenditure levels, and level of vulnerability.

Table 2. Basic household characteristics (participants and non-participants in forest-based livelihood).

Nature extent of forest extraction

The study first assessed the extent (value) of forest-based livelihood disaggregated by wealth groups and type of products extracted (firewood, wild vegetables, fruits, and honey). We then compared the extraction intensities between the female-headed and male-headed households. This comparison was necessary to deepen the understanding of gender dynamics in forest-based livelihood decisions. We specifically tested the hypothesis that there were no significant differences in forest extraction intensity between male and female-headed households across the wealth groups and product categories. The results are as shown in .

Table 3. Extent and nature of participation in forest-based livelihood.

shows that, except for wild vegetables, male-headed households have a higher value of all main forest products extracted. This could be explained by differences in gender roles which discourage women from engaging in forest extraction for commercial purposes (Amevenku et al. Citation2019; Mai et al. Citation2019). In the study area, harvesting of food products from the forest is usually viewed as women’s work because of gender norms that limit them to reproductive and subsistence-based roles (Pouliot and Treue Citation2013; Powel et al. Citation2013; Nguyen et al. Citation2020). This would explain why female-headed households extracted wild vegetables at a higher intensity for home consumption. Our findings are consistent with other studies which show limited engagement in commercial-based forest livelihood among women (Lax and Köthke Citation2017; Rasmussen et al. Citation2017; Imfumu and Lukoki Citation2020). In addition, other studies also show that men often dominate the governing jurisdiction over forest resources implying differential access, which may disadvantage women (Lidestav Citation2010; Mai et al. Citation2019).

As shown in , the intensity of extracting forest products was higher among middle-wealthy group compared to the other wealth categories. The lower extraction intensity among the wealthier households could be explained by their access to other alternative livelihood opportunities which raises the opportunity costs of engaging in forest-based livelihoods (Heubach et al. Citation2011; Nguyen et al. Citation2015). Similarly, the intensity of extraction among the resource-constrained (poorer) households can be dissuaded because of their inability to meet the direct and transaction costs of obtaining forest products. These findings imply that forest extraction decisions vary among households depending on the household type (gender and wealth category), nature, and extent of forest-based livelihood.

Determinants of forest-based livelihood decisions

presents the results of Cragg’s Double hurdle model, which includes the household decision levels on forest-based livelihood (decision to engage in forest-based livelihood (Column 2) and the household decisions on the intensity of forest extraction (Column 3). The analysis includes variables representing various households’ capitals (human, physical, financial, social, and natural) which are assumed to influence the decision and extent of forest extraction.

Table 4. Cragg’s Double Hurdle model results.

The results show that while gender did not influence households’ decision to extract, it positively affected the intensity of extraction. This is could be attributed to gender differences in time endowment, with women facing constraints given that they have to attend to other household roles. Similarly, there are societal norms in the study area which limit women from engaging in certain forest-based livelihood forms, such as collecting firewood for sale (see also, Fisher Citation2004; Amare et al. Citation2017; Smith et al. Citation2017). As shown in , the household head’s age negatively influenced households’ decision to extract forest products. This could be explained by the fact that older household heads have access to more resources accumulated over time, allowing them to pursue other alternative and possibly more lucrative livelihood activities. A global study on environmental resource dependence (Angelsen et al. Citation2011) found that older household heads engaged in forest-based livelihood at a lower level in part because they had accumulated assets over time which allowed them to engage in alternative livelihood activities. Besides, extraction processes such as the harvesting of timber or fuelwood may be physically strenuous or labor intensive which may dissuade older people from engaging in these activities (Lax and Kothke Citation2017; Balde et al. Citation2020). The size of the household had a positive influence on forest-based livelihood decisions. Consistent with our finding, Angelsen et al. (Citation2011) argued that households with more household members are more likely to have the capacity to supply the labor needed for forest extraction activities. Additionally, households with more members are more likely to face higher demand for food and other non-food items which may therefore push them into forest-based livelihoods (Maua et al. Citation2018; Demie Citation2019).

further shows that while access to agricultural extension services negatively influenced the households’ decision to engage in forest-based livelihood, its influence on the intensity of extraction was not important. The finding is partly consistent with Babulo et al. (Citation2008) and Melaku Getahun (Citation2016) who show that access to extension services can enable a household to access other alternative livelihoods through improved farm profits and agribusiness. Similar to the variable extension, the level of education did not influence the household’s choice of forest extraction, but negatively affected the intensity of forest extraction. A possible explanation is that educated household heads are more likely to have alternative livelihood sources, such as wage labor, teaching, or government jobs (Pouliot and Treue Citation2013; Jannat et al. Citation2018).

The results show that transaction costs reflected in distance to the market or to an all-weather road negatively affected the decision on the intensity of forest extraction. This is consistent with other studies (Zenteno et al. Citation2013; Ofoegbu et al. Citation2017) which show that households with better access to physical capital such as paved roads tend to have lower engagement with forest-based livelihood. Similarly, land size had a negative influence on the intensity of forest extraction. Access to land increases the potential to earn from agricultural activities therefore reducing the need for forest extraction (McElwee and Bosworth Citation2010; Melaku Getahun Citation2016). Group membership was included in the analysis to measure the influence of social capital on forest-based livelihood activities. The results show that being a member in forest user group positively influenced extraction decisions. This association could be as result of sharing of information on the opportunities for forest extraction (Paumgarten Citation2005; Langat et al. Citation2016; Masoodi and Sundriyal Citation2020). Equally, the collective performance of forest extraction activities can lower transaction costs therefore increasing the likelihood of engaging in forest-based livelihood.

The results also show that financial capital, such as access to credit, had a negative influence on the extent of forest extraction. A possible explanation is that access to credit can allow households to engage in alternative livelihood activities such as retail shops and mobile money transfer services which is consistent with wider literature (Kimengsi et al. Citation2019; Reta et al. Citation2020). Further, the influence of income on the decision to extract was negative, implying that increase in income reduces the likelihood of engaging in forest-based livelihoods (Pandey et al. Citation2016).

In order to assess how forest extraction, differ by wealth categories, we applied a set of probit regressions and report the results in Annex 1. The results show existence of variability in the determinants of forest extraction across wealth groups. While the high vulnerability may push households to engage in forest-based livelihoods, the lack of assets and other resources required for extraction activities can constrain the level of engagement.

Conclusion and policy implications

This article analyzed the nature, extent, and factors influencing forest extraction decisions among rural households in Kenya. The article shows that engagement in forest-based livelihood was generally higher for households with lower asset value, membership in forest user associations, and households headed by males. Institutional aspects such as access to agricultural markets, credit, extension services, and membership in forest user groups increased the likelihood of extracting higher value products. Overall, our findings show that in addition to asset endowment, other contextual factors such as gender, access to markets, agricultural extension, and membership in farmer groups defined whether a household extracted forest products for survival or wealth accumulation.

Overall, the findings of this study reveal that a household’s resource endowment has an important influence on choice of a livelihood strategy. Equally, the article demonstrates that diversification of households into forest-based livelihood varies according to differential access to entitlements, restrictions, and opportunities, a wide range of motivations and wealth disparities. The differences in motivations, nature, and intensity of forest extraction have implications on sustainable forest use. Incorporating this understanding in forest management strategies is important in addressing challenges of forest degradation in developing countries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the residents of the study region and the enumerators for the support that they gave during the entire research period. We also wish to thank all those who took their time to review this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amare D, Mekuria W, Wondie M, Teketay D, Eshete A, Darr D. 2017. Wood extraction among the households of Zege Peninsula, Northern Ethiopia. Ecol Econom. 142:177–184.

- Amevenku FKY, Asravor RK, Kuwornu JKM, Zhang X. 2019. Determinants of livelihood strategies of fishing households in the volta Basin, Ghana. Cogent Econ Finance. 7(1):1595291–1595291.

- Angelsen A, Jagger P, Babigumira R, Belcher B, Hogarth NJ, Bauch S, Börner J, Smith-Hall C, Wunder S. 2014. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: a global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 64(1):S12–S28.

- Angelsen A, Larsen HO, Lund JF, Smith-Hall C, Wunder S, editors. 2011. Measuring livelihoods and environmental dependence: methods for research and fieldwork. London: Earthscan.

- Babulo B, Muys B, Nega F, Tollens E, Nyssen J, Deckers J, Mathijs E. 2008. Household livelihood strategies and forest dependence in the highlands of Tigray, Nothern Ethiopia. Agric Syst. 98(2):147–155.

- Balde BS, Karanja A, Kobayashi H, Gasparatos A. 2020. Linking rural livelihoods and fuelwood demand from mangroves and upland forests in the coastal region of Guinea. In Sustainability challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa I. Singapore: Springer; p. 221–244.

- Dave R, Saint-Laurent C, Murray L, Antunes Daldegan G, Brouwer R, de Mattos Scaramuzza CA. 2019. Second Bonn challenge progress report, application of the barometer in 2018. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Demie G. 2019. Contribution of non-timber forest products in rural communities’ Livelihoods around Chilimo forest, West Shewa, Ethiopia. J Nat Sci. 9(22). http://doi.org/10.7176/JNSR/9-22-04

- Do TL, Nguyen TT, Grote U. 2019. Livestock production, rural poverty, and perceived shocks: evidence from panel data for Vietnam. J Dev Stud. 55(1):99–119.

- Ellis F. 2000. Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- FAO. 2016. Global forest resources assessment 2015-how are the world’s forest changing? 2nd ed. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Fisher M. 2004. Household welfare and forest dependence in Malawi. Envir Dev Econ. 9(2):135–154.

- Heubach K, Wittig R, Nuppenau EA, Hahn K. 2011. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: a case study from northern Benin. Ecol Econ. 70(11):1991–2001.

- Imfumu E, Lukoki F. 2020. Profitability and determinants of the choice of commercialization of non-timber forest products in Kinshasa. Case of Salacia pynaertii De Wild, Gnetum africanum Welw, Pteridum centrali-Africanum Hieron. Open Access Lib J. 7(1):1–11.

- Jannat M, Hossain MK, Uddin MM, Hossain MA, Kamruzzaman M. 2018. People’s dependency on forest resources and contributions of forests to the livelihoods: a case study in Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh. Int J Sust Dev World Ecol. 25(6):554–561.

- Kaitibie S, Omore A, Rich K, Salasya B, Hooton N, Mwero D, Kristjanson P. 2009. Influence pathways and economic impacts of policy change in the Kenyan dairy sector. Nairobi (Kenya): Research Report 15 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute.

- Kimengsi JN, Pretzsch J, Kechia MA, Ongolo S. 2019. Measuring livelihood diversification and forest conservation choices: insights from rural Cameroon. Forests. 10(2):81.

- Langat DK, Maranga EK, Aboud AA, Cheboiwo JK. 2016. Role of forest resources to local livelihoods: the case of East Mau forest ecosystem, Kenya. Int J for Res. 2016:1–10.

- Lax J, Köthke M. 2017. Livelihood strategies and forest product utilisation of rural households in Nepal. Small-Scale For. 16 (4):505–520.

- Lidestav G. 2010. In competition with a brother: women’s inheritance positions in contemporary Swedish family forestry. Scand J For Res. 25(sup9):14–24.

- Mai A, Iwanschitz B, Weissen U, Denzler R, Haberstock D, Nerlich V, Schuler A. 2019. Status of Hexis’ SOFC stack development and the Galileo 1000 N micro-CHP system. ECS Trans. 35(1):87–95.

- Mamo G, Sjaastad E, Vedeld P. 2007. Economic dependence on forest resources: a case from Dendi District in Ethiopia. Forest Policy Econ. 9(8):916–927.

- Mango N, Makate C, Tamene L, Mponela P, Ndengu G. 2017. Awareness and adoption of land, soil and water conservation practices in the Chinyanja Triangle, Southern Africa. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 5(2):122–129.

- Masoodi HUR, Sundriyal RC. 2020. Richness of non-timber forest products in Himalayan communities—diversity, distribution, use pattern and conservation status. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 16(1):1–15.

- Maua JO, Tsingalia MH, Cheboiwo J. 2018. Socioeconomic factors influencing dependence of households on non-timber forest products in South Nandi Forest, Kenya. J Econom Sust Dev. 9(14).

- Mburu LM, Wakhungu JW, Gitu KW. 2007. Determinants of smallholder dairy farmers’ adoption of various milk marketing channels in Kenya highlands. Livest Res Rural Dev. 19(9):46–59.

- McElwee G, Bosworth G. 2010. Exploring the strategic skills of farmers across a typology of farm diversification approaches. J Farm Management. 13(12):819–838.

- Melaku Getahun J. 2016. Oromo indigenous knowledge and practices in natural resources management: land, forest, and water in focus. J Ecosyst Eco Graph. 6 (2):181.

- Nguyen TT, Do TL, Bühler D, Hartje R, Grote U. 2015. Rural livelihoods and environmental resources dependence in Cambodia. Ecol Econ. 120 (C):282–295.

- Nguyen TT, Nguyen TT, Grote U. 2020. Multiple shocks and households’ choice of coping strategies in rural Cambodia. Ecol Econ. 167(167):106442.

- Nielsen ØJ, Rayamajhi S, Uberhuaga P, Meilby H, Smith-Hall C. 2013. Quantifying rural livelihood strategies in developing countries using an activity choice approach. Agric Econ. 44(1):57–71.

- Ofoegbu C, Chirwa PW, Francis J, Babalola FD. 2017. Socioeconomic factors influencing household dependence on forests and its implication for forest-based climate change interventions. South For. 79(2):109–116.

- Pandey AK, Tripathi YC, Kumar A. 2016. Non timber forest products (NTFPs) for sustained livelihood: challenges and strategies. Res J For. 10(1):1–7.

- Paumgarten F. 2005. The role of non-timber forest products as safety-nets: a review of evidence with a focus on South Africa. GeoJournal. 64(3):189–197.

- Pouliot M, Treue T. 2013. Rural people’s reliance on forests and the non-forest environment. World Dev. 43:180–193.

- Powel JE, Sorenson EP, Rozzelle CJ, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. 2013. Scalp dermoids: a review of their anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 29(3):375–380.

- Rasmussen LV, Watkins C, Agrawal A. 2017. Forest contributions to livelihoods in changing agriculture-forest landscapes. For Policy Econ. 84(84):1–8.

- Reta Z, Adgo Y, Girum T, Mekonnen N. 2020. Assessment of contribution of non-timber forest products in the socioeconomic status of peoples in Eastern Ethiopia. Op Acc J Bio Sci & Res. 4(4). http://doi.org/10.46718/JBGSR.2020.04.000101

- Scoones I. 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis’. Brighton: IDS. Working paper No. 72.

- Smith HE, Hudson MD, Schreckenberg K. 2017. Livelihood diversification: the role of charcoal production in southern Malawi. Energy Sustain Dev. 36:22–36.

- Thondhlana G, Muchapondwa E. 2014. Dependence on environmental resources and implications for household. Ecol Econ. 108:59–67.

- Uberhuaga P, Smith-Hall C, Helles F. 2012. Forest income and dependency in lowland Bolivia. Environ Dev Sustain. 14(1):3–23.

- Velded P, Angelsen A, Sjaastad E, Berg GK. 2004. Counting on the environment: forest incomes and rural poor. Washington (DC): The World Bank. Environment Department papers. Paper No. 98, Environmental economics series.

- Wunder S, Borner J, Shively G, Wyman M. 2014. Safety nets, gap filling and forest: a global comparative perspective. World Dev. 64(S1):S29–S42.

- Zenteno M, Zuidema PA, de Jong W, Boot RG. 2013. Livelihood strategies and forest dependence: new insights from Bolivian forest communities. For Policy Econ. 26:12–12.

Annex 1

Determinants of Forest-based livelihood among wealth categories