Abstract

Adults in the modern society suffer from stress, and prolonged stress brings about various diseases. Hence, national measures to prevent stress are needed, and countries seek approaches based on the nature. The aim of this study is to analyze the effects of forest healing programs on stress in the Korean adult population through a meta-analysis. Eleven pertinent studies were selected, and the effect size of each parameter, pooled effect size, and heterogeneity were examined. Further, the heterogeneity of effect sizes was analyzed through moderator analysis using categorical variables as the moderators. The results were as follows. First, the pooled effect size of stress was −0.95, which is considered a large effect size. Total variance I2, which indicates the heterogeneity of effect size of stress, was quite large, at 77% (Q = 43.29, p < .0001). A meta-ANOVA analysis was performed for a moderator analysis with type of program, length of program, size of experimental group, subjects, sex, number of program sessions, and type of article, and there were no statistically significant differences between the parameters.

Introduction

Owing to the difficulties arising from the growingly complex social structure, excessive workload, academics, and interpersonal relationships, stress is common among people in the modern society. Stress is the body’s nonspecific response to stimuli, and the body tries to resist stress and maintain homeostasis. If homeostasis is disturbed amid psychological exhaustion, the individual becomes easily stressed, and the body feels strained as the individual drains all available resources. Prolonged stress leads to an increased prevalence of disease and depression as well (Choi & Lee Citation2003; Diwan et al. Citation2004; Kim and Kim Citation2007; Jung et al. Citation2017). Further, hormone changes due to stress leads to psychological and mental maladjustment (Breamner Citation1999; Shin Citation2017). Therefore, appropriately coping with psychological problems is crucial to reliving stress and protecting oneself (Suh Citation2011). Failure of coping leads to various types of diseases, including cardiovascular disease, gastric disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, chronic fatigue, and anxiety. Medical expenses have increased by 1.5% over the past five years since 2014, the fastest increase among OECD countries. In addition, the share of medical expenses in GDP has also increased by 1.5% over the past five years from 6.5% in 2014 to 8.0% in 2019 (Korea Insurance Research Institute Citation2021). The reasons for the increase are stagnant labor productivity, income growth, and aging population. And the government proposes various ways to prevent increased medical expenditures such as lifestyle adaptation and exercise. In particular, nine out of ten adults, that is, more than two-thirds of the total population, suffer from stress, calling for attention on adults’ physical health and psychological wellbeing and further research (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs Citation2016; Kwak Citation2018; Statistics Korea Citation2018). Moreover, there are mounting interests on forest healing, which utilizes forest resources that account of 64% of the Korean territory to boost humans’ immunity (Lee et al. Citation2015), and forest healing activities are used to protect psychological wellbeing and mental health from stress Forest healing promotes health through activities in the nature, such as walking in the forest and appreciating scenery, which improves the autonomic nervous, endocrine, and immune systems and thus relieve stress and promotes emotional stability (Li Citation2010; Jeon and Shin Citation2017). Previous studies confirmed that forest healing programs have positive effects on depression, anxiety, anger, emotional stability, stress, and mood and improves psychological aspects (Hong et al. Citation2013; Lim Citation2014; Kim and Lee Citation2014; Yoo et al. Citation2014; Kim et al. Citation2015; Lee Citation2015; Shin et al. Citation2015). In other words, the forest is an effective place that heals and rejuvenates people by helping them control their accumulated stress and achieve mental stability (Jo Citation2009; Park and Lee Citation2016). Research on forest healing in Korea was initiated by Shin and Oh (Citation1996) on patients with depression, and more research data are being accumulated year after year. However, past studies have been conducted as individual studies with varying subjects and topics. Thus, it is necessary to pool currently available research data on the psychological effects of forest healing, particularly through meta-analysis (Hwang Citation2015). This analysis is a good means to infer common trends and is widely utilized in various disciplines, including medicine, nursing, and education. Meta-analyses enable integrating individual study results and analyze common aspects among the research (West Citation2000), and the results are more reliable than the results of individual studies (Oh Citation2002). In addition, more specific analyses can be performed if there are no common findings among studies, enabling researchers to draw more accurate and systematic conclusions. Therefore, using a meta-analysis would enable us to take effect size into account and apply the findings in the field. The aim of this study is to systematically review various studies on the effects of forest healing programs on stress in adults to identify the features of various parameters applied in the forest healing programs. Furthermore, this study attempts to examine the effects of forest healing on stress to explore the direction of research on continuous and effective forest healing programs. Finally, this study will present foundational data for utilizing forest healing as preventive and rehabilitative purposes against disease in the adult population.

Research method

Research subject selection

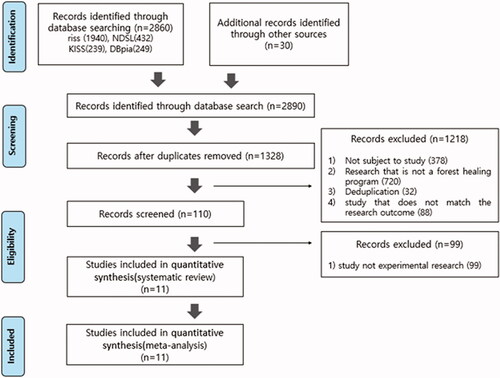

This study is a meta-analysis of the effects of forest healing programs on stress in the Korean adult population, and the study was conducted in adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analysis (PRIMSA) guidelines (Moher et al. Citation2009). Data that qualify per the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected based on the Participants, Intervention, Comparisons, Outcomes, Study Design (PICOS) model from Korean search engines (Choi et al. Citation2020). Participants were set to adults aged 18 years or older who have participated in a forest healing program. The intervention was set to programs run in the forest. The comparators were set to comparison groups that did not participate in a forest healing program. Among various effects of forest healing, the outcome was set to stress, a negative psychological emotion, and only studies that presented statistical values were selected. Finally, study designs were limited to non-randomized controlled trials (NRCTs), and the language was limited to Korean. Only Korean studies were selected because the purpose of this study is to investigate the effects and features of forest healing programs tailored to Korea’s natural environment. The exclusion criteria were individuals with cognitive disorder, such as dementia, pain and mental illness, or cancer, and activities performed in a natural environment other than a forest. Further, case series, meta-analyses, and studies with full text unavailable were excluded. After establishing the inclusion criteria, the literature search and selection processes were performed in adherence to the PRSIMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al. Citation2009).

Collecting data

Data were searched online from theses and journal-published articles in Korea on forest healing programs published in between 2000 and 28 February 2021. This is because forest healing research began in earnest in Korea from the beginning of 2000. The search was conducted in the RISS, NDSL, KISS, and DBpia using AND/OR. In the Korean databases, a combination of the following key words was used: (forest healing OR forest bathing OR forest experience OR forest adventure) AND (old age OR middle-aged OR elderly OR climacteric OR college student) AND (stress). Additionally, the researcher manually searched for the references to select additional studies.

Assessment of bias

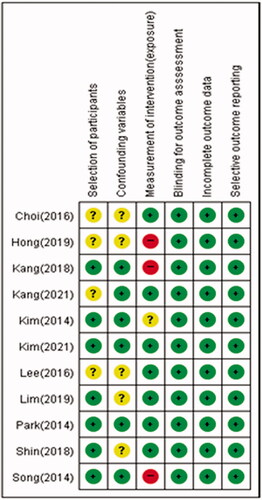

Quality of the studies was assessed using the RevMan 5.3 software, using the risk of bias assessment tool for non-randomized studies (RoBANS) (Kim et al. Citation2011). The assessment is performed on six parameters: selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of intervention, blinding for outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. The selected studies were rated to have a high (-), low (+), or uncertain (?) risk of bias for each domain, and the ratings were determined upon consensus among two researchers.

Data management and analysis

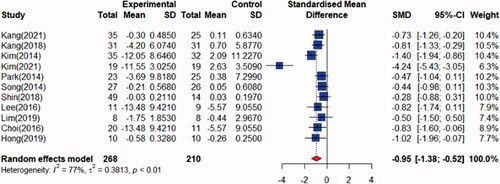

The general characteristics of the studies included authors, publication year, study participants, size of experimental group and control group, sex, study design, number of program sessions, length of program, contents of program, and outcomes. To compared the effect sizes of forest healing program on stress, meta-analysis was performed using RStudio. The pooled effect size of stress was computed, and the outcome parameters were presented as the difference of the average post-intervention value and average pre-intervention value. Because the study samples varied widely, effect size was converted to Hedge’s g, and 95% confidence interval was computed (Borenstein Citation2009). Forest plot presents the effect size, statistical significance, and weights in each study, and it shows the pooled effect size and statistical significance (Hwang Citation2020). In addition, the studies are independent and estimate the size of populations with different sample and duration, a random-effect model was used for the analysis. According to Cohen (Citation1988), an effect size of 0.10–0.30 is small, 0.40–0.70 is medium, and ≥ 0.80 is large. For heterogeneity, the average effect size was presented using a forest plot, and heterogeneity was analyzed using the total variance Q and actual variance I2. An I2 of 25% or lower indicates small heterogeneity, 25–50% indicates moderate heterogeneity, and ≥75% indicates large heterogeneity (Higgins and Green Citation2011). To assess the heterogeneity of stress, meta-ANOVA was performed with the types of programs, length of program, sample size of the experimental group, subjects, sex, number of sessions, and type of article. Further, to check for publication bias, asymmetry was visualized using a funnel plot, and the consistency of the outcomes was analyzed (Borenstein et al. Citation2009).

Results and discussion

Literature selection

A total of 2,890 studies were identified, and the studies were classified using the ProQuest RefWorks software. Duplicate searches, studies with ineligible subjects and those not conducted on forest healing programs, and studies with ineligible study outcomes and study designs were excluded. The full text of the resulting 110 studies was reviewed to select qualifying studies. Data collection and selection process was independently performed by two researchers, and disagreements were resolved by reading the full texts together and reviewing them against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reasons for the exclusion were recorded. Based on this process, a total of 11 studies were included in the meta-analysis ().

Characteristics of the included studies

It is the characteristics of the 11 studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Regarding type of publication, six were journal articles, while five were theses. The most common study subjects were college students (five studies). The studies were published from 2014 and present, and the most common number of program sessions was fewer than 12 sessions. Regarding study design, all 11 studies were NRCTs, and the details are presented in .

Table 1. General characteristics of included studies.

Quality assessment

shows the results of quality assessment of 11 included studies. The risk of bias in selection of participants and confounding variables was low, with 6 studies (54.5%) rated as low and 5 studies (45.5%) rated as uncertain. The risk of bias for measurement of intervention was low in 7 studies (63.6%), high in 3 studies (27.3%), and uncertain in 1 study (9.1%). The risk of bias for blinding for outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting was low in all 11 studies (100%). The risk of bias was low (80.3%) overall, confirming a high quality of the included studies.

Effects of Forest healing program on stress

The effect size on stress in 11 studies was pooled and computed as Hedge’s g, and a forest plot was used for visualization for a better understanding (). The pooled effect size was large, at −0.95 (95% CI: −1.38∼−0.52), and did not include 0, and thus was statistically significant (Z = −4.36, p < .00001). In terms of U3, an index for distribution overlap proposed by Cohen (Citation1988), the average of the experimental group is about 84% of the comparison group when the average of the control group is about 50%. In addition, in terms of binomial effect size display (BESD) proposed by Rosenthal and Rubin (Citation1982), the success rate is 27% in the control group but 72% in the experimental group. Thus, forest healing programs are considered to have a large effect on stress, and I2, a statistic for heterogeneity of the effect size, was large, at 77% (Q = 43.29, p < .0001).

Moderator analysis

The total effect size in Hedge’s g was −0.95(95% CI: −1.38∼−0.52), and heterogeneity was large, as proposed by Higgins and Green (Citation2011) (I2 = 77%, Q = 43.29, p < .0001). A moderator analysis needs to be performed if the effect sizes are heterogeneous across studies to additionally analyze the reason for the heterogeneity (Moher et al. Citation2009). A moderator analysis was performed for 11 included studies, to examine the heterogeneity of the effects on stress. A meta-ANOVA was performed with the type of program, length of program, size of experimental group, study participants, sex, number of sessions, and type of article as moderators (). The effect sizes of different forest healing programs were: −0.55 for forest therapy, −0.74 for walking and meditation, −1.43 for walking, and −1.02 for massage. Walking had the greatest effect size, but the effect sizes were not statistically significantly different among the types of forest healing programs (Qb = 3.34, p = .343). In terms of length of program, the effect size of programs that last between 60–120 min was large at −1.07, but there were no statistically significant differences among different lengths of program (Qb = 6.43, p = .166). In terms of size of the experimental group, the effect sizes were generally large, at −1.99 for 10–19, −0.53 for 20–29, and −0.98 for 30–39, but the differences were not statistically significant (Qb = 6.19, p = .185). In terms of study participants, the effect sizes were −1.36 for college students, −0.55 for adults (20s–40s), and −0.88 for middle-aged women (50s), with the greatest effect size for college students, but the differences were not statistically significant (Qb = 3.34, p = .187). In terms of sex, the effect size was −1.09 for mixed sexes and −0.68 for female only, but the differences were not statistically significant (Qb = 1.23, p = .268). In terms of number of program sessions, the effect size was large for 5–10 sessions at −1.75, but the difference in the effect sizes was not statistically significant (Qb = 5.48, p = .241). In terms of type of article, the effect size was −1.42 among theses and −0.71 among journal articles, but the difference was not statistically significant (Qb = 0.11, df = 1,45, p = .229). Moderators were analyzed using meta-ANOVA, and the heterogeneity of effect sizes were explained by moderators; however, there were no statistically significant differences observed for the parameters. Thus, other factors that can explain the differences in the effect sizes among studies shoud be taken in to consideration (Borenstein et al. Citation2009).

Table 2. Results of moderator analysis on stress.

Publication bias and sensitivity

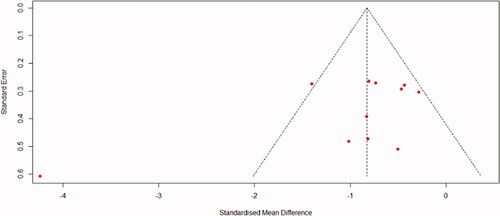

Publication bias was assessed based on funnel plot, which is the generally recommended method to visualize symmetry, and verified using the Egger’s regression test (Borenstein et al. Citation2009). There was a relatively good symmetry. The Egger’s regression analysis, which shows the relationship between sample size and effect size, performed to statistically test for error (asymmetry of effect size) confirmed the absence of publication error, with bias = −3.59(t = −1.61, df = 9, p = .142). Sensitivity testing showed that excluding the study by Kim (Citation2021) did not have a marked effect on total effect size and heterogeneity ().

Discussion

This study attempted to quantitatively analyze the effects of forest healing programs on stress relief in the Korean adult population in order to provide evidence-based practical and academic data. To this end, 2,890 journal articles and theses published in Korea between 2000 and 28 February 2021 were reviewed, and 11 studies relevant to the study topic were chosen to be included in the meta-analysis. Although studies on the topic are consistently on the rise since 2014, 11 is still a small number, highlighting the need to continue research on forest healing programs for adults. The characteristics of the included studies were as follows. First, six were journal articles, while five were theses. Regarding study participants, there were five studies conducted on college students, three studies on middle-aged adults, and three studies on middle-aged women. The types of stress targeted by forest healing programs were mostly occupational, parenting, and physical causes. In particular, forest healing programs with preventive purposes targeting various types of stresses in college students, such as employment, academic, and peer relations should be developed (Jang Citation1997). As a result of the study by Song et al. (Citation2014), the stress response of nursing female college students had a positive effect through the forest healing experience. Lee and Shin (Citation2019) found that forest healing programs using school forests affected the emotional stability and positive thinking of college students. Second, the most common length of program was 120 min or less (four studies), and the most common number of program sessions was 12 sessions or fewer (four studies). Third, all of the included studies were NRCTs. Therefore, subsequent studies should utilize various experimental study designs to increase the validity of the studies.

The effect size of forest healing programs on stress as reported in 11 studies was large, at −0.95 (95% CI: −1.38∼−0.52) (Cohen Citation1988). In other words, forest healing programs had a positive effect on relieving stress among adults. However, I2 was 77%, indicating large heterogeneity (Q = 43.29, p < .0001). As this study analyzed published research articles and theses, there is a possibility of publication bias in that unpublished research articles and reports were excluded. Thus, publication bias was analyzed over several steps. The results confirmed the absence of error large enough to undermine the validity of the study findings, and the overall validity of the effect size of the study was verified.

This study has several strengths. First, it computed the effect size of forest healing programs on stress, a negative psychological factor, in the Korean adult population, and by examining the overall effect of the program on stress, it presented evidence supporting the effectiveness of the programs. Second, by analyzing according to the type of forest healing programs in Korea, length of the programs, size of experimental group, study participants, sex, number of sessions, and type of articles, this study presented foundational data for developing these programs in the field. Third, by quantitatively integrating and analyzing existing studies that reported the effectiveness of these programs, this study provided generalized findings, and thus replication studies on the same topic are not needed, in addition to providing rational evidence assisting in decision-making in developing field programs. Fourth, this study provided clinical evidence for the average effect size for an outcome of forest healing programs. In addition, this study was an opportunity for exploring study designs for assessing the effectiveness of forest healing programs by analyzing existing literature. The findings will contribute to minimizing potential error committed by researchers in study designs and assessment and selection of scales for forest healing programs in the future. Fifth, subsequent studies should be conducted on children and adolescents’ stress as well, because stress in the modern society has emerged an important social problem among younger students.

Conclusions

This study meta-analyzed the effect size of forest healing programs on stress, a negative psychological aspect, in the Korean adult population based on NRCTs. The effectiveness of forest healing programs in relieving stress are being scientifically proven, and in consideration of the increasing number of people suffering from stress, forest healing programs hold significance as a topic of research. This study attempted to present foundational data for developing programs that relieve stress by analyzing the effect size of forest healing programs based on parameters such as type of program, length of program, size of experimental group, study participants, sex, number of sessions, and type of article. However, the number of studies included in the meta-analysis was small, so the results should be interpreted with caution. Further, subsequent studies that analyze the long-term effects of these programs on stress are also needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- *References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. 2009. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex (UK): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, p. 452.

- Breamner JD. 1999. Does stress damage the brain? Biol Psychiatry. 45(7):797–805.

- Choi EH, Kim MJ, Lee EN. 2020. A meta-analysis on the effects of mind-body therapy on patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Korean Acad Nurs. 50(3):385–400.

- *Choi JH, Kim HJ, Shin CS, Yeon PS, Lee JS. 2016. The effect of 12-week forest walking on functional fitness, self-efficacy, and stress in the middle-aged women. J Korean Inst For Recr. 20(3):27–38.

- Choi MR, Lee IH. 2003. The moderating and mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between stress and depression. Korean J Clin Psycho. 22(2):363–383.

- Cohen J. 1988. Satistical power analysis for the behavioral science. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Diwan S, Jonnalagadda SS, Balaswamy S. 2004. Resources predicting positive and negative affect during the experience of stress: a study of older Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. Gerontologist. 44(5):605–614.

- Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [Internet]. London (UK): The Cochrane Collaboration.

- *Hong JS. 2019. Effects of the aroma massage-therapy program using Needle Fir essential oil on the restoration from stress, somnipathy and fatigue in middle-aged women [Graduate Department of Forest Therapy (dissertation)]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- Hong SS, Kim HC, Cho SH. 2013. The effects of forests healing for cognitive function. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 24(1):63–74.

- Hwang SD. 2015. Meta-analysis using R. Seoul: Hakjisa.

- Hwang SD. 2020. Meta-analysis using R. Seoul: Hakjisa.

- Jang HS. 1997. The attachment, self-esteem and self-efficacy in adolescence. Korea J Hum Dev. 4:88–105.

- Jeon JY, Shin CS. 2017. Effects of indirect forest experience on the human psychology. Korean J Environ Ecol. 31(4):420–427.

- Jo YB. 2009. A study on the development of suitable locations evaluation model and therapy type to therapeutic forests [dissertation]. Iksan: Wonkwang University.

- Jung M, Choi W, Lee Y. 2017. Stress relief method and depression. Korean J Fam Pract. 7(6):837–843.

- *Kang BH. 2021. Effects of forest therapy program on academic and job-seeking stress reduction in university students [dissertation]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- *Kang YM, Koo CD, Shin WS. 2018. Effects of forest experiences on the feeling and child care stress of disabled children. J Korean Inst For Recr. 22(2):65–70.

- *Kim JG. 2021. The effect of self-guided forest therapy program [dissertation]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- Kim DJ, Lee SS. 2014. Effects of forest therapy program in school forest on employment stress and anxiety of university students. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 17(2):107–115.

- *Kim DC, Lee SS. 2014. Effects of forest therapy program in a school forest on employment stress and anxiety of university students. J Korean Soc People Plants Environ. 17(2):107–115.

- Kim HS, Kim B. 2007. The effects of self-esteem on the relationship between the elderly stress and depression. J Korea Geron Soc. 27(1):23–37.

- Kim MH, Wi AJ, Yoon BS, Shim BS, Han YH, Oh EM, An KW. 2015. The influence of forest experience program on physiological and psychological states in psychiatric inpatients. J Korean for Soc. 104(1):133–139.

- Kim SY, Park JE, Seo HJ, Seo HS, Son HJ, Shin CM, Lee YJ, Jang BH. 2011. NECA's guidance for undertaking systematic reviews and meta-analyses for intervention. National Evidence-based healthcare Collaborating Agency Team of New Health Technology Assessment.

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2016. Research report. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Korea Insurance Research Institute. 2021. Available from: https://www.kiri.or.kr/about/ci.do.

- Kwak KJ. 2018. Developmental psychology. Seoul: Hakjisa.

- Lee JE, Shin WS. 2019. The effects of campus forest therapy program on university students emotional stability and positive thinking. Korean J Environ Ecol. 33(6):748–757.

- *Lee JS. 2016. The effect of 12-weeks forest walking on functional fitness, self-efficacy, and stress in the middle-aged women [dissertation]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- Lee SH. 2015. The influence of forest healing program on stress high risk group′s job stress, depression, mood states, self-esteem, and HRV [dissertation]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- Lee YH, Kim SM, Li N. 2015. The effects of forest therapy on medical expenses reduction. J Women Econ. 12(2):23–44.

- Li Q. 2010. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ Health Prevent Med. 15(0):9–17.

- *Lim JG. 2019. The effects of the differences of place environment on blood pressure, resting heart rate, cortisol, serotonin, NK-cell, and mood state during meditation and walking exercise [dissertation]. Chuncheon: Hallym University.

- Lim YS. 2014. Impacts of forest therapy program on the self-esteem, depression degree and life-satisfaction of senior citizens in nursing home [dissertation]. Cheongju: Chungbuk National University.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 339:b2535.

- Oh SS. 2002. Meta-analysis theory and practice. Seoul: Konkuk University Press.

- *Park HS, Shin CS, Yeoun PS, Kim JY. 2014. A comparative study on the stress recovery effect of forest therapy. J Korean Inst For Recr. 18(1):13–24.

- Park SA, Lee MW. 2016. An analysis of the healing effects by types of forest space-focused on psychological restorativeness and satisfaction. J Korean Inst Landsc Archit. 44(4):75–85.

- Rosenthal R, Rubin D. 1982. A simple, general purpose display of magnitude of experimental effect. J Educ Psychol. 74(2):166–169.

- *Song JH, Cha JG, Lee CY, Choi YS, Yeoun PS. 2014. Effects of forest healing program on stress response and spirituality in female nursing college students and there experience. J Korean Inst For Recr. 18(1):109–125.

- Shin CS, Yeon PS, Jo MN, Kim JY. 2015. Effects of forest healing activity on women's menopausal symptoms and mental health recovery. J People Plants Environ. 18(4):319–325.

- *Shin BS, Lee KK. 2018. The effects of forest bathing on social psychological and job stress. J Naturopathy. 7(2):51–62.

- Shin KH. 2017. Stress handbook-managing stress for your perfect life. Seoul: CIR.

- Shin WS, Oh HK. 1996. The influence of the forest program on depression level. J Korean For Soc. 85(4):586–595.

- Statistics Korea. 2018. Social research-level of stress. Seoul: Statistics Korea.

- Suh KH. 2011. Relationships between stresses, problem-focused coping, upward/downward comparison coping and subjective well-being of college students. Korean J Youth Stud. 18(8):217–236.

- West GB. 2000. The effects of downsizing on survivors:a meta-analysis [dissertation]. Virginia. Virginia university.

- Yoo YS, Kim HC, Lee CJ, Jang NC, Son BK. 2014. A study of effects of sallimyok (forest therapy)-based mental health program on the depression the psychological stability. J Korean Soc School Commun Health Educ. 15(3):55–65.