Abstract

Indonesia’s 120.5-million-hectare forest area shrinks due to deforestation, mainly community cultivation. Forest Land Redistribution (FLR) via programs like Social Forestry, TORA, KHDPK, Food Estate, and infrastructure development attempts to address this issue but conflicts with climate change and biodiversity goals. This review analyses the urgency of FLR for non-forestry and proposes balanced policy recommendations for economic development and environmental preservation. Implementing FLR in Indonesia is crucial for national programs like SF, TORA, FE, and infrastructure development, impacting biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation. It should follow three key principles: regional strategies for sustainability, a mitigation hierarchy to prevent biodiversity damage, and enhancing biodiversity hotspots to connect fragmented forests, fostering wildlife movement and genetic diversity for resilient ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Indonesia has a legally designated forest area of 120.5 million hectares. This designation implies that the state controls and protects forest areas to be managed sustainably (MoEF Citation2020). Forests are vital ecosystems that play a crucial role in maintaining environmental balance, supporting biodiversity and human life, regulating climate, and sustaining local and global communities. In Indonesia, forests have been designated under various function categories, (Margono et al. Citation2012; MoEF Citation2020). However, the management of these forests has undergone significant changes over the years, with four distinct periods marking the country’s forest management history (Resosudarmo et al. Citation2012). Since the mid-1960s, Indonesia has witnessed a surge in commercial exploitation of forests, leading to widespread deforestation. This was further aggravated by shifting cultivation, transmigration, agriculture, and palm oil plantation activities. Forest areas thus are consequently reduced. Such areas are in constant contention for conversion into non-forest development zones, often for large-scale plantations (Sunderlin and Resosudarmo Citation1996; MoEF Citation2020; Susetyo Citation2022). To address these issues, the Government of Indonesia (GoI) has implemented laws and regulations governing the use of forest areas for various purposes, while also recognizing the rights of local communities regarding land ownership and usage. However, as the demand of forest land for development purposes continues to rise, especially after the decentralization era deforestation and conflicts over forest tenure in different regions of Indonesia increased significantly (Resosudarmo et al. Citation2012; Gunawan and Sugiarti Citation2015).

Changes in forest area designation and conversion for non-forestry activities are now governed by specific regulations, allowing national strategic projects utilization for purposes such as mining, infrastructure development, agriculture, and public facilities. These changes are subject to permits under responsible management and utilization of forest areas (Republic Indonesia Citation2015b).

In response to decades of deforestation and to achieve various environmental and social objectives, the GoI has also introduced several policies related to the redistribution of forest land utilization. These initiatives include the social forestry (SF) program, agrarian reform land program (TORA), food estate (FE) program, and the designation of forests with special management (KHDPK). These policies aim to empower local communities, restore forests, enhance biodiversity, and support economic recovery and food security projects (MoEF Citation2021a; Greenpeace Citation2022; Susetyo Citation2022).

This review aims to critically analyze the significance of forest land redistribution (FLR) for non-forestry purposes in Indonesia. It seeks to explore the implications and complexities of such redistribution, examining its relevance to biodiversity conservation and climate change issues. By applying various scientific perspectives, this review intends to provide policy recommendations that strike a balance between economic development and environmental preservation.

2. Method

2.1. Rationale

Indonesia grapples with a dual challenge: balancing economic growth and equity alongside the pressing issue of deforestation. The surge in deforestation began post the 1997/1998 economic crisis, driven by extensive forest encroachment. This was exacerbated by decentralization, which transferred forest management authority to local districts and provinces, intensifying forest exploitation and conversion. Despite the economic recovery, community-driven cultivation of forest areas persists, leading to deforestation in diverse ecosystems including lowland to mountain forests, mangroves, and peatlands. The 2019 COVID-19 pandemic further compounded the issue, causing economic downturns and a subsequent spike in deforestation. Simultaneously, legal processes continue to allocate forest areas for regional and infrastructure development, contributing to forest shrinkage and fragmentation.

Deforested areas, now under community or group control, pose a challenge due to ineffective management and hindrances in ecosystem restoration. To address deforestation, foster community prosperity, and drive national development, various policies have been instituted, such as social forestry, TORA (Tanah Obyek Reforma Agraria/Land of Agrarian Reform Objects), Food Estate, KHDPK (Kawasan Hutan Dengan Pengelolaan Khusus/Forest Area with Special Management), and infrastructure development. These policies center on forest land redistribution (FLR) for non-forestry purposes. However, there is growing concern that these programs may conflict with Indonesia’s commitments in climate change mitigation through Enhanced Nationally Determined Contributions (ENDC) and biodiversity conservation. Consequently, a thorough review and analysis of these policies is imperative to underscore their urgency and ensure they align with broader environmental goals.

2.2. Materials and methods

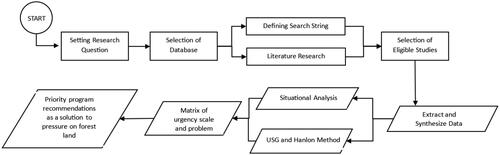

shows the steps of the literature review. First, it was setting of research question and then selected the database. Second, the database selection was conducted through (i) defining of search string and (ii) literatures research finding. This selection would produce the eligible literature studies. Third, the eligible literatures are then extracted and synthesized to support the next analysis Next, an analysis of Urgency, Seriousness and Growth (USG) was carried out, namely: 1. Urgency (urgency of the issue); the problem must be solved immediately related to the availability of time; 2. Seriousness (gravity of the issue): how a problem can lead to more serious issues.; 3 Growth (development of issues): the possibility of the problem growing worse if not well addressed. USG is one of the tools to arrange priority issues to be resolved (Creswell Citation2014). The reference in analyzing data uses a need assessment approach (Chovancová Citation2014) by determining rankings and scores from 1 to 5 or 1 to 10. Issues with the highest total score are priority issues.

2.3. Identification of forest land redistribution

Identifying forest land redistribution involves legal, environmental, and socio-economic factors. The process includes collecting and studying regulations related to forest land tenure, management, community and indigenous community management rights, and regulations related to changes in forest function, ownership status, and management access. Secondly, we examined government policies and programs related to the redistribution of forest land, specifically those focused on land reform, the rights of indigenous peoples, and environmental conservation. It is important to acknowledge the complexity of this issue and the various perspectives involved. Third, a literature search was conducted to evaluate the potential ecological consequences of forest land redistribution, such as deforestation, habitat loss, soil erosion, and impacts on biodiversity. Fourth, the social impacts of forest land redistribution on local communities were assessed, including trends in livelihoods, access to forests, cultural practices, and land tenure arrangements. Fifth, changes in the designation of forest areas for non-forestry purposes were tracked over time using official data released by the government through the forestry statistics book.

By considering these factors and measures, we make an analysis of forest land redistribution, its drivers, and its impacts on the ecological, social, and economic environment. Recommendations could then be provided for a more sustainable and equitable redistribution of forest land.

2.4. Analysis of the relationship between forest land redistribution and biodiversity conservation and climate change

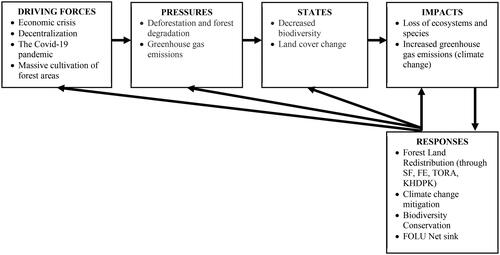

To analyze the impact of forest land redistribution on biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation, the DPSIR (Driving forces, Pressures, State, Impacts, and Responses) framework was employed (Kristensen Citation2004; Maxim et al. Citation2009; Gari et al. Citation2015). This framework is well-suited for analyzing the complex relationship between human activities and the natural environment (Kristensen Citation2004; Bradley and Yee Citation2015) as outlined below ():

Figure 2. The DPSIR framework can effectively illustrate the complex interplay between drivers, pressures, states, impacts, and responses in relation to forest land redistribution, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation.

2.4.1. Driving forces

Economic crisis: The economic crisis of 1997/1998 in Indonesia triggered significant upheaval, marked by economic shocks, policy reforms, and political transformations. Rising poverty and unemployment rates led to a strategic shift toward agriculture expansion to navigate the crisis, inadvertently exacerbating issues in the forestry sector, such as a surge in illegal logging activities, particularly in Java and other regions, and large-scale forest clearings for plantations. Amidst these pressures, forests also faced intensified deforestation and degradation, driven primarily by oil palm expansion, along with cocoa, coffee, shrimp, rubber, and pepper production.

Decentralization: Decentralization post-1998 reform led to the establishment of new provinces and districts, expanding territorial boundaries, and driving changes in national spatial planning. This process altered the function and designation of state forest areas, with numerous provinces implementing changes in forest area allocation and function for non-forestry purposes.

The Covid-19 pandemic: The COVID-19 pandemic has brought both challenges and opportunities for forests. Lockdown in Indonesia has led to increased illegal wildlife hunting and forest encroachment, driven by reduced farmer incomes. Sustainable forest programs have suffered setbacks, hindering achievements and exacerbating household food insecurity. Proposed mitigation measures include promoting community-based forest management, diversifying income sources, enhancing land productivity, utilizing online markets, and implementing policies for sustainable forest management and community development, emphasizing the need for adaptive strategies amidst pandemic-induced challenges for forest conservation and livelihoods.

Massive cultivation of forest areas: Farming activities, induced by agricultural expansion, are the primary cause of deforestation in tropical areas, including Indonesia, driven by food demand and economic growth. This expansion impacts various ecosystems, including lowlands, uplands, mangroves, and peatlands, with crops like rubber, tea, palm oil, coffee, and cocoa contributing to substantial forest loss.

2.4.2. Pressures

Deforestation and forest degradation: Redistribution of forest land can result in deforestation (permanent removal of forest) and forest degradation (degradation of forest quality), causing habitat loss and biodiversity decline.

Greenhouse gas emissions: Conversion of forest land results in emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases, increasing global warming and climate change.

2.4.3. States

Decreased biodiversity: Deforestation and forest degradation result in habitat and species loss, reducing biodiversity and genetic diversity.

Land cover change: Conversion of forest area into non-forest land alter ecosystem structure and function, affecting water cycling, carbon storage, and local and regional climate patterns.

2.4.4. Impacts

Loss of ecosystems and species: Deforestation and forest degradation result in the loss of important ecosystems and the species that depend on these habitats.

Increased greenhouse gas emissions: Conversion of forest land results in CO2 emissions that contribute to global warming and climate change.

2.4.5. Responses

Forest Land Redistribution: Forest Land Redistribution (FLR) in Indonesia aims to address issues hampering effective forest management by altering the function and designation of forest areas, guided by Government Regulation Number 104 of 2015. The FLR program seeks to increase food production, promote equitable development, enhance human-nature relations, improve economic welfare, manage urban-rural interactions, and ensure sustainable forest use. Implemented through national programs like Social Forestry (SF), Land of Agrarian Reform Objects (TORA), Food Estates (FE), Forest Area with Special Management (KHDPK), and infrastructure development, FLR is pivotal in achieving these objectives.

Climate change mitigation: Through equitable and sustainable policies, Indonesia can maximize its forests’ role as carbon sinks, aiding global climate change mitigation efforts. Conservation and sustainable practices will strengthen the nation’s climate resilience and contribute to broader global initiatives in combatting climate change.

Biodiversity Conservation: The establishment of new protected areas, buffer zones, and wildlife corridors should be integral parts of the land redistribution planning process. Additionally, sustainable land redistribution can promote the restoration of degraded ecosystems, enhancing the overall health and resilience of Indonesia’s biodiversity

FOLU Net sink: Achieving target of IFNET 2030 (Indonesia’s FOLU-NS 2030) requires mitigation actions to reduce GHG emissions from deforestation, forest degradation, and land use changes, ensuring absorption rates surpass emission rates by 2030. Forest Land Redistribution (FLR) is crucial for empowering local communities, indigenous groups, and responsible land managers to enhance carbon sequestration, mitigate deforestation, and promote sustainable land use. Combining FLR with mitigation actions presents a holistic approach to combating climate change and achieving a net sink in the forestry and land sector by 2030, in line with Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets.

3. History of forest land use in Indonesia

The historical evolution of forest land use in Indonesia can be divided into four periods: the precolonial-colonial period, the Old Order, the New Order, and the Reformation Era. Forest land tenure involves determining who has access to and control over forest land, as well as the rights to use, manage, and transfer forest resources. This concept is crucial in understanding the political context of forest land use (Larson Citation2013).

Teak forests existed in Java since the sixteenth century, prior to colonization (Dhani Citation2015). The archipelago consisted of kingdoms with varying territories and laws, where land and resource rights, including forests, were based on customary and local wisdom (Madonna Citation2019). Forest management positions, such as Juru Wana or Juru Pangalasan, were already in place, and indigenous communities had easy access to forests for their livelihoods. However, the arrival of colonizers changed the perception of forests as an economic resource (Ferdaus et al. Citation2014).

During the Dutch colonial period, the Forestry Regulation and Agrarian Law were established, allowing the colonial government to control land and categorize it as state-owned (Dhani Citation2015). The Dutch East Indies government managed teak forests in Java, but overexploitation led to their severe degradation. Forest management techniques were introduced, and local community access to forests was limited, leading to an increase in forest violations (Afifah and Suprijono Citation2020). The Japanese colonial government further exploited forests during its brief rule (Nurjaya Citation2005).

President Soekarno introduced the Basic Agrarian Law No. 5 Year 1960, transferring customary land and resource rights to the central government (Rachman and Siscawati Citation2013). In 1950, around 87% of Indonesia’s land was estimated to be forested (Tsujino et al. Citation2016). The Forestry Service, initially under the Ministry of Agriculture, was later transformed into the State Forestry Company (PERHUTANI). The Ministry of Forestry (MoF) was established in 1964, but political upheavals, including the G-30-S PKI rebellion, the MoF was suspended (Nurjaya Citation2005).

During the New Order era, natural resources, including forests, were seen as potential sources of economic growth (Economic Growth Development) (Rachman and Siscawati Citation2013). The Basic Law on Forestry defined state forests and private forests, with the state having control over all forests in Indonesia (Rachman and Siscawati Citation2013; Siscawati et al. Citation2017). Forest management regulations continued from the Dutch colonial era, and deforestation increased due to timber exploitation (Siscawati et al. Citation2017).

The Reformation Era brought constitutional, legislative, and bureaucratic reforms, including the revocation of the Basic Forestry Provisions Law (Law Number 5 of 1967) and its replacement with the Forestry Law (Law of The Republic Indonesia Number 41 of 1999 Concerning Forestry Citation1999; Ardiansyah et al. Citation2015). Decentralization was implemented, and communities reclaimed their customary rights in state forests (Suwarno et al. Citation2018). The SF program was introduced, allowing communities access to forests while maintaining the state’s ownership of forest resources (Nanang and Inoue Citation2000; Budiono et al. Citation2018).

During the New Order period and the reform era, there was massive exploitation, and permits were issued for both foreign and domestic investors to establish plantations, particularly oil palm, by converting forest areas (forest area release) and clearing rice fields and transmigration land. According to the Head of the Public Relations Bureau of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), 7.3 million hectares of forest area were released from 1984 to 2020 (Susetyo Citation2022).

Throughout these four periods, the history of forest management policies was shaped by political and economic developments, aiming to generate national income from forest resources. This had a direct impact on deforestation and led to communities living around the forest losing access to and benefits from nearby resources (Resosudarmo et al. Citation2012).

4. Driver of pressure on forests area

Some pressures on forest land run dynamically based on the land use land use change on forestry (LULUCF) in the field influenced by both natural and anthropogenic influences, with substantial implications for ecosystem dynamics and carbon storage potential (Mishra et al. Citation2022). Some pressures come from national economic development (economic crisis), political issue (decentralization policy), national health condition (covid-19 pandemic), and forest encroachment done by local community for crops and livestock cultivation which had contributed one-fifth of forest loss in Indonesia (Mullan et al. Citation2017; Austin et al. Citation2019).

4.1. The 1997/1998 economic crisis

In 1997/1998, Indonesia faced economic shocks, policy reforms, and political transformations, leading to an increase in poverty and unemployment rates. To overcome the crisis, agriculture expansion was considered crucial. However, this expansion had adverse effects on the forestry sector, resulting in illegal logging activities, particularly in Java and other regions (Sunderlin Citation1999). Forest cover was also compromised due to spontaneous decisions by farmers and large-scale forest clearing for plantations (Sunderlin Citation1999).

The economic crisis and political changes in 1998 further intensified population pressure on forests, particularly reducing forest cover. Oil palm was the primary commodity driving large-scale forest clearing, with cocoa, coffee, shrimp, rubber, and pepper production also contributing to spontaneous forest clearing (Sunderlin Citation1999). Some examples are local communities in Lampung and surrounding areas which were motivated by the sharp increase in local coffee prices and the transitional government regime to reopen forest areas and encroachment on the Rawa Danau Nature Reserve in Banten which was primarily perpetrated by people living nearby rather than outsiders (Darmawan et al. Citation2009).

Sunderlin and Resosudarmo (Citation1999) criticized the idea that population growth, particularly among small landholders, was the main cause of deforestation. Based on the events during the 1997/1998 economic crisis, they concluded that while population growth played a role, it should be seen as an intermediary variable rather than an independent one. Other non-population factors likely had a more significant impact. The depreciation of the currency made agricultural and mining exports attractive, as they generated US dollars while input costs were paid in the local currency. This led to the expansion of oil palm and cocoa plantations in 1998, resulting in the loss of forest cover (Sunderlin and Resosudarmo Citation1999).

4.2. Decentralization

Deforestation has been occurring since the mid-1960s, coinciding with the onset and continuous growth of commercial forest exploitation during that time. This was also resulted from shifting cultivation, self-initiative and regular transmigration, agriculture, plantations, and industrial timber plantations (Sunderlin and Resosudarmo Citation1996). However, massive and extensive deforestation occurred in the aftermath of the reform movement in 1998. It has prompted the establishment of a government decentralization system through the enactment of Law No. 22 of 1999, subsequently replaced by Law No. 32 of 2004 and again by Law No. 23 of 2014 on Regional Government. Decentralization has resulted in the emergence of new provinces and districts, also known as territorial expansion. In the context of territorial expansion, natural resource management is essential for sustainable economic development (Tan et al. Citation2023). This has driven changes in the spatial planning of provinces and districts at the national level, leading to alterations in spatial structure and patterns that involve changes in the function and designation of state forest areas.

Since the enactment of the regional government law until December 2020, a total of 34 provinces have implemented changes in forest area allocation and function through the review of provincial spatial planning (RTRWP) (MoEF Citation2021b). By the end of 2020, a cumulative total of 897,302.71 hectares of forest areas have been converted into transmigration settlements, and 7,243,745.10 hectares have been allocated for other non-forestry purposes. Additionally, there were permits for temporary use of forest areas for non-mining exploration covering 48,147.45 hectares, for production operations in mining areas covering 559,218.59 hectares and for non-mining purposes reached 81,235.67 hectares. There were also exchanges of forest areas totaling 88,192.91 hectares, occurring in 13 provinces (MoEF Citation2021b).

4.3. The Covid-19 pandemic

Analyses of the COVID-19 pandemic’s economic crisis on forests show uncertain long-term impacts. Wunder et al. (Citation2021) found that inhibiting and increasing factors of deforestation balance each other, with no clear evidence of increased deforestation in Latin America but no significant reduction either. Lack of environmental monitoring during the pandemic has enabled illegal use of forest products by armed groups and mafia (Lopez-Feldman et al. Citation2020). In Nepal, officials observed an increase in illegal wildlife hunting during lockdown due to a lack of oversight (Poudel Citation2021). Similar concerns were raised by Golar et al. (Citation2020) in Indonesia, where the social and economic impacts of the pandemic may lead to increased forest resource utilization and illegal logging in Sulawesi.

Pieter et al. (Citation2022) found that COVID-19 significantly affected farmers’ lives, leading to decreased demand, lower selling prices, and a 38.45% decline in farmers’ incomes. The pandemic also hampered the SF program, reducing the achievement from 1.6 million ha in 2019 to 0.6 million ha by the end of 2020 (MoEF Citation2021b). Food security at the household level was also impacted (A’Dani et al. Citation2021). Food security is also exacerbated by the impact of climate change, which causes a decrease in agricultural productivity due to changes in rainfall and an increase in temperature (Sharifi et al. Citation2019; Azizi et al. Citation2022).

As a result, farmers faced reduced income reduction and sought alternative sources, leading to increased forest encroachment, both with and without legal licenses (MoEF Citation2022d). To prevent further destruction, various actions have been taken during and after the pandemic, such as motivating farmer groups to manage forests with health protocols, creating new income-generating activities, increasing land productivity, utilizing online markets, addressing SF limitations, applying information technology for marketing, ensuring product quality, and implementing operational policies for COVID-19 safety, sustainable forest management, and community development (Ihza Citation2020; Jusmalinda and Asmin Citation2020; RECOFTC Citation2021; Laksana et al. Citation2022; MoEF Citation2022d)

4.4. Massive cultivation of forest areas by the communities

Farming activities had been recognized as the main direct driver of deforestation and contribute to the loss of 70% of forest area in almost all tropical areas including Indonesia (Gibbs et al. Citation2010; Hosonuma et al. Citation2012; Charnsungnern and Tantanasarit Citation2017). Agricultural expansion in forest area is basically driven by increasing demand for food, to do make room for crops and livestock generated from population and income growth. However, governments also play important role, either by passively ignoring the conversion of natural ecosystems or through policies that encourage new agricultural conversions (Mullan et al. Citation2017).

Deforestation affects various ecosystems in Indonesia, including lowlands, uplands, mangroves, and peatlands, driven by agricultural expansion (Achmad and Purwanto Citation2014). This shift toward agriculture, fueled by products like rubber, tea, palm oil, coffee, cocoa, spices, and cinnamon, supports economic growth and livelihoods (Nazarreta et al. Citation2020; Saputra et al. Citation2021; Nguyen et al. Citation2022). Over 20 years, Sumatra lost 7 million hectares of primary forest and 33% of degraded forest, mainly in its Southern and Central lowlands (Margono et al. Citation2012). Monoculture plantations replaced 15,989 hectares of forest in 25 years (Kuswanda and Sunandar Citation2018), influenced by the Green economy and global commodity demand, impacting neighboring countries as well (Jansen and Kalas Citation2023).

Historically, upland forest cultivation was primarily in lowlands, with limited expansion into highlands, except for tree-based plantations like rubber (Wilcove et al. Citation2013; Fox et al. Citation2014; Ahrends et al. Citation2015; Crist et al. Citation2017). Recent studies show significant forest losses due to highland cropland expansion in Asia and Eastern Africa (Barrow et al. Citation2010; Pongkijvorasin and Teerasuwannajak Citation2015; Zeng et al. Citation2018; Summase et al. Citation2019; Lynam Citation2022). Upland forest cultivation in Indonesia is widespread, from horticulture farming in Java to South Sulawesi (Kholil and Dewi Citation2015; Pudjiastuti and Sudarmadji Citation2018; Auliyani Citation2020; Santosa Citation2023).

Mangrove clearing in Indonesia has been substantial, with an average annual rate of 52,000 hectares between 1980 and 2005 (Murdiyarso et al. Citation2015). From 1990 to 2021, the mangrove area decreased from 4.25 million hectares to 3.31 million hectares, with 19.26% (637,624.31 hectares) considered critical (Choong et al. Citation1990; Ditjen PDASRH Citation2021). Exploitation of mangroves for shrimp farming, timber, and other purposes dates back to the 1800s (Ilman et al. Citation2016), intensifying in the 1990s in Java, Sumatra, and Kalimantan (Choong et al. Citation1990) and continuing in the 2000s for aquaculture, oil palm, and timber (Richards and Friess Citation2015; Sillanpää et al. Citation2017).

Indonesia holds nearly half of the world’s tropical peatland, around 20.6 million hectares (Page et al. Citation2011; Osaki et al. Citation2016; Yuliani and Rahman Citation2018), with land conversion being the primary driver of peatland destruction (Maskun, Naswar Assidiq, et al. Citation2021). Transition to oil palm plantations, including peatland fires, has caused extensive damage (Syahda Citation2021). About 20% of oil palm plantations are on peatlands, with potential expansion posing additional risks (Syahda Citation2021). Peat swamp forest conversion to oil palm is estimated at 50,000 to 100,000 hectares annually (Wibowo Citation2010). Peatland is also utilized for the national FE program, integrating food, agriculture, plantation, and animal husbandry (Danurdara Citation2023).

Small-scale agriculture and plantations have contributed significantly to national forest loss in Indonesia, accounting for one-fifth of deforestation (Austin et al. Citation2019). Deforestation threatens biodiversity and contributes to Indonesia’s role in air pollution and climate change, increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and reducing water quality and quantity (Foley et al. Citation2011; Austin et al. Citation2019). Expanding farming in protected upland areas has led to negative consequences like floods, landslides, erosion (Kholil and Dewi Citation2015; Arifien et al. Citation2021), forest damage, environmental degradation (Haryati Citation2014; Pudjiastuti and Sudarmadji Citation2018; Mukaromah and Handoyo Citation2019; Santosa Citation2023) and unsuitability for development (Aminuddin et al. Citation2005; Razali et al. Citation2018). Peatland utilization, especially for oil palm plantations, raises climate change concerns (Syahda Citation2021).

5. FLR as solutions

Land redistribution is an effort by governments to modify the distribution of land ownership. Therefore, FLR is allocation of forests land to beneficiaries to providing more equitable access (FAO Citation2022). The FLR in Indonesia is generally carried out to solve problems that burden forest areas which make their management ineffective. The FLR conducted by changing the function and designation of forest areas. This change refers to the legal basis, namely Government Regulation Number 104 of 2015 about procedures for changing the designation and function of forest areas.

The Changing of forest areas require a long process and must go through a study by an independent integrated team. This integrated team consists of experts from various disciplines and stakeholders. This is to ensure that changes to the designation and function of forest areas correctly assessed. Changes in forest areas for non-forestry can be carried out partially in the district area or simultaneously with the revision of the spatial planning for provincial areas. Partially, changes in forest areas are carried out through forest area exchanges and release of forest areas (Republic Indonesia Citation2015a). The policy of changing forest areas is implemented to meet the demands of national development dynamics and the aspirations of the community changes in designation, function, and utilization or temporary use of forest areas (Iskandar et al. Citation2011).

The main objectives of the FLR program are to: (a) increase and diversify food production, (b) equitable distribution of development, (c) improve human relations with nature, (d) improve people’s economic welfare, (e) manage urban-rural interactions and (f) sustainable use of forests. In the last few decades, FLR done through various national programs such as SF, TORAFootnote1, FEFootnote2, KHDPKFootnote3 and national infrastructure development.

5.1. Social forestry (SF)

Social Forestry (SF) is a development strategy aimed at improving the livelihood conditions of local communities by involving them in small-scale forest management activities. It emerged in response to sustainability concerns in densely populated developing countries (Mallik and Rahman Citation1994). In Indonesia, SF policy has evolved through three generations, corresponding to changes in the political system, with the third generation adopting SF as a national program with an ambitious target of 12.7 million hectares (Fisher et al. Citation2019).

Law Number 41 of 1999 mandated SF as a response to the ineffectiveness of the state-based forest management approach during the New Order era, aiming for balanced benefits between economic, ecological, and socio-cultural interests (Pambudi Citation2020). Decentralization in the reform era led to community-based forest management approaches, but doubts arose within the government, leading to a majority of forest areas being managed by private sector entities, with minimal community involvement (Kuncoro et al. Citation2018).

Since 2016 and 2021, the SF policy has been simplified through the Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) Number P 83 of 2016 and Number 8 of 2021, providing legal access and approval to communities for managing forest resources through various schemes (Gunawan et al. Citation2022). The position of SF is now legally stronger since it has been included in the Job Creation Law. Previously, SF was only regulated through ministerial regulations. The current SF program in Indonesia supports the community’s economic recovery post the Covid-19 pandemic through the establishment and improvement of Social Forestry Business Groups (KUPS). However, the program’s realization is still below expectations, with only 5.63 million hectares out of the targeted 12.7 million hectares achieved as of August 2023 (Setiawan Citation2023).

SF initiatives have evolved into new modalities of forest management, empowering local managers and, as a result, enabling for the integration of varied local practices and the support of local livelihoods. However, the implementation of these programs faces numerous hurdles. State-mandated community initiatives, for example, will remain isolated endeavors until there are reforms in the wider economic and social governance frameworks, including the devolution of rights to local users (Moeliono et al. Citation2017; Wong et al. Citation2020; Gunawan et al. Citation2022). To ensure the success of SF, policies and regulations in Indonesia need to provide legal certainty regarding community-managed forest land rights (Pane et al. Citation2021). Collaboration between the government, local communities, civil society, and other stakeholders is essential for the effective implementation of SF policies (Mutaqin et al. Citation2022).

5.2. TORA

The Agrarian Reform Object Land Program in Indonesia, also known as TORA, is a government strategy aimed at achieving community economic equality in forest area utilization (Nurlinda Citation2018). In contrast to the SF program which only grants permits/approvals for forest management, TORA can be claimed as a property right over land. Supported by Presidential Regulation Number 88 of 2017 and the Decree of the Minister of Environment and Forestry in 2018, TORA focuses on allocating ownership, tenure/access, and legal land use to resolve land use conflicts in forest areas.

TORA has seven main objectives, including reducing land tenure inequality, creating prosperity and social welfare, alleviating poverty and generating jobs, improving access to economic resources, resolving agrarian conflicts, enhancing food security, and maintaining environmental quality. This program allocates 9 million hectares of land for distribution, consisting of asset legalization of ±4.5 million hectares and land redistribution of ±4.5 million hectares (Alvian and Mujiburohman Citation2022).

To determine areas suitable for TORA, four criteria are considered: 1) forest areas used for settlement or supporting livelihoods of local and customary communities, 2) forest areas with public and social facilities, 3) areas where farming activities managed by the local community (e.g. paddy fields, mixed gardens, ponds, or dry land agriculture), and 4) forests managed by customary law communities as defined by statutory provisions.

TORA’s implementation follows a top-down approach (Tarigan Citation2018). Although its main goal is multi-sectoral, the main priority is the social welfare of the community. Notably, ecological aspects related to biodiversity in forest areas, the impact of forest conversion into cultivation areas, and other uses have not received sufficient attention and require further research.

In the process of transferring forest management rights from the state to the community, it is essential to establish clear guidelines to preserve the forest’s condition. Socializing on absolute conservation strategy to the community is crucial to raise awareness of the importance of biodiversity, particularly for rare and endemic species, and encourage their involvement in conservation efforts. TORA can be a viable alternative to balance economic growth with environmental conservation, provided that the main principles in determining forest land within the program are strictly adhered to, ensuring harmony between ecology and economic considerations (Nijman and Menken Citation2005).

5.3. Food estates

The food estate (FE) is a large-scale crop cultivation business covering an area of more than 25 hectares (ha) that relies on science, technology, capital, and modern management (Djoko Citation2020; Lubis et al. Citation2021). The priority commodities for its development in these FEs include rice, corn, soybeans, cassava, sweet potatoes, peanuts, sorghum, fruits, vegetables, sago, palm oil, sugar cane, and cattle or chickens (Fadillah et al. Citation2021).

The FE is part of the National Strategic Program aimed at building a national FE on 1.6 million ha in 2015-2019, spread across Central Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, Papua, and Maluku (Aru Islands), and an additional 165,000 ha in 2020-2024 in Central Kalimantan, South Sumatra, North Sumatra, and East Nusa Tenggara (Setyo and Elly Citation2018; Lasminingrat and Efriza Citation2020). Previous FE programs like the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) Project and the Delta Kayan FE projects had negative environmental and social impacts (Ito et al. Citation2014).

With large-scale food production, FE utilizes capital and technology to produce food sustainably. However, development on peatlands raises concerns about deforestation, loss of biodiversity, social conflicts, and carbon emissions (Maskun et al. Citation2021). While the value of peat swamp forests for biodiversity is not fully understood, the development policy in Central Kalimantan focuses on utilizing existing ex-PLG and non-ex-PLG lands (peatland development for agriculture) (Posa et al. Citation2011; Mukti Citation2020).

The operation of FE on degraded peatlands carries a moderate to high risk of negative impacts, especially with changes in farming methods and increased use of inputs and mechanical equipment (Basundoro and Sulaeman Citation2022). Additionally, using protected forest areas for food security has raised concerns about their role in reducing GHG emissions and mitigating climate change (BBC Citation2020; Eryan et al. Citation2020; Pantau Gambut Citation2021; Mutia et al. Citation2022). To manage the risk, peatlands with certain thickness can be used for agricultural cultivation, while others are designated as protected areas (Yeny et al. Citation2022).

5.4. KHDPK

In Java Island, the forest area spans 3,135,648.7 Ha, managed by PT. Perhutani (82%), the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (16%), and the Regional Government (2%) (Ekawati et al. Citation2015). PT. Perhutani has been managing the forests since 1972, involving 25,863 villages where farming is the main livelihood and many are poor and underdeveloped (Hardiyanto Citation2015). Conflict often arises between PT. Perhutani and the community regarding land management allocation, despite Law No.41/1999s shift toward granting legal rights to use forest products for communities (Ekawati et al. Citation2015; Ramadhan et al. Citation2021).

Various community involvement in PT. Perhutani started in 1972, including intercropping programs. In 1982, the Forest Village Community Development (PMDHFootnote4) program was launched, covering an area of 47,549 Ha involving 137,090 households (Perum Perhutani Citation1996). The PMDH development for community access to forest management has been a long and dynamic process. One such program is Community Base Forest Management (PHBMFootnote5), introduced in 2001 by Perhutani, which later became part of the partnership category of the SF scheme with permits like Recognition and Protection of Forestry Partnerships (Kulin KKFootnote6) (MoEF Citation2016). Subsequently, in 2017, a new regulation called Social Forestry Utilization Permit (IPHPSFootnote7) was launched in the Perum Perhutani work area, resulting in both Kulin KK and IPHPS schemes being implemented in the area.

IPHPS is unique, granting forest land permit without rights and providing more secure tenure and profit-sharing, but community interest is limited due to perceived investments exceeding its capacity (Ragandhi et al. Citation2021). Despite the benefits to farmers from P.39/2017 implementation, confusion remains among 36% of farmers regarding the new regulation, and cases of rejection from Perhutani toward IPHPS have been observed (Ragandhi et al. Citation2021). The SF schemes in Java, IPHPS and Kulin KK, have not fully utilized the economic, social, and ecological potential of Java’s forests, leading to persistent land conflicts between Perhutani and the community (Ramadhan et al. Citation2021).

The forest management in Java is regulated by the Job Creation Law and Government Regulation Number 23 of 2021, which designates KHDPK in certain state forests located in production forest areas and protected forests in Central, East, and West Java, and Banten provinces (MoEF Citation2022c). This decision has implications for PT. Perhutani, obliges the release of its 1,103,941 Ha to the Central Government (MoEF), and serves various purposes, including SF and forest rehabilitation. The policy reflects President Joko Widodo’s efforts to redistribute forest land to communities and reduce forest tenure inequality (Ekawati Citation2019).

5.5. Infrastructure development

The infrastructure sector is one of the main focuses in the Joko Widodo administration. This is intended to improve connectivity and stimulate economic growth in various regions of the country (Pati Regency Public Works and Spatial Planning Departmen Citation2020). National strategic infrastructure project includes national strategic roads that serve national and international interests based on strategic criteria, namely having a role in fostering national unity and integrity, serving vulnerable areas, being part of cross-regional or cross-international roads, serving interstate border interests and important state assets, and for national defence and security. Strategic Roads can be built in forest areas based on cooperation or lease use of forest areas (MoEF Citation2019).

Infrastructure development such as airports, seaports, highways, toll roads, railways, dams and irrigation networks, high-voltage electricity networks are some of the National Strategic Project (PSN) that require redistribution of forest areas (Gunawan and Sugiarti Citation2015). This development in forest areas, has significant and negative effects on the environment and wildlife migration (Sigit Citation2013; Baderi Citation2018). Linear infrastructure, such as roads and highways, rapidly expands in tropical forests, leading to roadkill, predation, and hunting of vulnerable species (Laurance et al. Citation2009). Toll road construction also disturbs local communities and damages the environment (Ministry of Public Work Citation2010; Fitri Citation2018).

In Indonesia, linear infrastructure is categorized as strategic roads in forest areas, designated for national interests, but their establishment should not divide the forestry area (Subarudi Citation2001; Sigit Citation2013). Proper planning and technical specifications are necessary to mitigate the negative impacts including habitat disturbance, hydrology function decrease, and forest conversion (MoEF Citation2019).

6. The relevancies and impacts of FLR

This section explores FLR’s relevance in Indonesia, focusing on its impact on climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation. Indonesia’s extensive forests are critical for global climate efforts, but mismanagement can lead to deforestation, disrupting the carbon cycle. Land use changes, including deforestation, threaten biodiversity. Conservation measures like protected areas and biodiversity assessments are vital. Lastly, we assess FLR’s role in Indonesia’s emissions reduction commitments, particularly in achieving FOLU Net Sink 2030 targets. Understanding these facets is crucial for shaping Indonesia’s environmental future and meeting climate and conservation goals.

6.1. Relevance to climate change mitigation

Forests play a crucial role in mitigating climate change by acting as carbon sinks, absorbing and storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (Nunes et al. Citation2020; Njana et al. Citation2021). Land use changes, often associated with FLR, can lead to deforestation and forest degradation, releasing stored carbon back into the atmosphere and exacerbating climate change (Houghton et al. Citation2012). Hence, it is crucial to carefully manage land redistribution to minimize the negative impacts on forest cover and carbon storage. Careful FLR planning can help mitigate these impacts and ensure that carbon-rich forests remain intact, preserving their role as critical carbon sinks. A comprehensive national climate change policy and alignment of sectoral policies are needed to mitigate and adapt to climate change and global warming. In addition, the use of modern technologies that are environmentally friendly and resource efficient and the implementation of climate change awareness programs are crucial (Azizi et al. Citation2022).

Proper forest management, including equitable land redistribution, is essential to ensure the preservation and expansion of forests, maximizing their capacity as carbon sinks (Ameray et al. Citation2021; Štraus et al. Citation2023). By implementing equitable and sustainable policies, the country can enhance its forests’ role as carbon sinks, sequestering significant amounts of carbon dioxide and contributing to global efforts in combating climate change. By ensuring sustainable practices and conservation of valuable forest ecosystems, Indonesia can bolster its climate change mitigation strategies and contribute to the broader global efforts to combat climate change and securing climate-resilient future for the nation.

6.2. Relevance to biodiversity conservation

Indonesia’s forests are home to a wide array of plant and animal species, including many endemic ones. Preserving these diverse ecosystems through well-managed FLR is essential for the long-term conservation of biodiversity. FLR in Indonesia holds significant relevance for biodiversity conservation. With land use change such as for agriculture, husbandry, industries, and settlements, biodiversity faces threats due to habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation (Haddad et al. Citation2015; Taubert et al. Citation2018; Galgani et al. Citation2021). Unplanned and unsustainable FLR can lead to deforestation, fragmentation, and degradation of forest habitats. These changes in land use pose a severe threat to biodiversity, resulting in the loss of species and disruptions to entire ecosystems.

Properly planned FLR can have a positive impact on biodiversity conservation. By designating protected areas and allocating land to communities for sustainable management, it becomes possible to preserve essential habitats for wildlife and maintain ecological connectivity. These protected areas play a critical role in biodiversity conservation, and FLR can help establish and maintain such areas. Strategies for FLR should be designed with careful consideration of biodiversity conservation goals. The establishment of protected areas, buffer zones, and wildlife corridors should be integral parts of the land redistribution planning process. Additionally, sustainable land redistribution can promote the restoration of degraded ecosystems, enhancing the overall health and resilience of Indonesia’s biodiversity. Furthermore, engaging local communities, civil society, and other stakeholders in decision-making can enhance the effectiveness of conservation efforts and ensure the sustainable use of forest resources.

6.3. Relevance to FOLU Net Sink

Forest and Other Land Use Net Sink (FOLU-NS) 2030 is a condition to be achieved through mitigation actions to reduce GHG emissions from the forestry and land sector under the condition that the absorption rate is higher than the emission rate in 2030 (MoEF Citation2023). FLR is highly relevant in the context of achieving FOLU-NS 2030 through mitigation actions. FOLU-NS 2030 requires mitigation actions to reduce GHG emissions from deforestation, forest degradation, and land use changes, aiming for higher absorption rates than emissions in 2030 (MoEF Citation2023).

FLR can play a vital role in helping achieve the absorption rate necessary to surpass the emission rate and create a net sink in 2030. Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) aims to reduce GHG emissions by 29% (unconditionally) and up to 41% (conditionally) by 2030 (Masripatin et al. Citation2017). The Enhanced NDC has increased the emission reduction target to 31.89% (unconditional) and 43.20% (conditional) (MoEF Citation2023). To achieve the NDC and FOLU-NS 2030 targets, Indonesia is accelerating emission reduction efforts, focusing on the forestry sector and land use change (LTS-LCCR document).

To achieve the NDC and FOLU-NS2030, FLR is highly relevant by empowering local communities, indigenous groups, and responsible land stewards, we can enhance carbon sequestration, mitigate deforestation, and promote sustainable land use practices. FLR, combined with mitigation actions, presents a holistic approach to combatting climate change and achieving a net sink in the forestry and land sector by 2030. To ensure environmental protection and sustainability, a comprehensive National Climate Change Policy is necessary. This policy should be aligned with other sectoral policies, such as those for industry, agriculture, energy, transportation, and economics (Azizi et al. Citation2022).

7. Urgency

What is the urgency of redistributing forestry land for non-forestry use? Looking back at the history of forestry land management and tenure, the FLR is an unavoidable consequence and land demands will continue to rise as the population grows. On the other hand, Indonesia is also facing the challenge of a high rate of biodiversity extinction and is requires a commitment to reduce emissions to increase carbon sequestration in order to mitigating global climate change. Since FLR has the potential to contradict biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation commitments, it is crucial to conduct an urgency analysis in order to determine a harmonization strategy between the issues.

An analysis was carried out using descriptive-qualitative techniques with Urgency, Seriousness, Growth (USG) analysis. Urgency is a program related to the time available and the time pressure is to solve the of biodiversity and climate change. Seriousness shows the consequences arising from delays in solving problems that cause these issues or the consequences that can cause other problems while Growth shows that program development will have a worse impact if left unchecked.

For urgency, we assign the highest score (5) to policies established by law, presidential decree, or government regulation, and a score of 4 for those established by ministerial decree. For seriousness, we give the highest score (5) for activities that have a very broad or international impact, a score of 4 for those with a broad or national-level impact that covers several islands, and a score of 3 for those with a fairly broad impact that could cover one island. For growth, we evaluate how likely the problem is to worsen if not resolved, assigning the highest score (5) for very likely to worsen, worsening (4), and moderately worsening (3).

The total USG score in shows that the priority programs to be implemented by the government are Social Forestry, Infrastructure Development, TORA, Food Estate and KHDPK, respectively.

Table 1. Matrix of Urgency, seriousness and growth of FLR.

8. Implications

Indonesia’s Fair Economy policy aims to redistribute around 12% of the country’s land area to farmers and communities by 2019, including forest lands (KSP, 2017). However, this reform may conflict or contradictive with emission reduction commitments as two-thirds of GHG emissions come from forests. SF programs focusing on FLR can impact livelihoods and climate change commitments. Implementation challenges arise from ambitious targets and rushed land distribution (Resosudarmo et al. Citation2019).

Indonesia is committed to supporting biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation, as agreed in COP 15 CBD and COP 27 UNFCCC. The country aims to limit the global average temperature increase to 1.5 °C and reduce the loss of high biodiversity areas, including ecosystems of high ecological integrity (CBD Citation2022; MoEF Citation2022a; UNFCCC Citation2022). To achieve these goals, FLR must consider environmental and biodiversity aspects, such as forest areas’ adequacy and cover. Furthermore, the government should also evaluate forest area concessions and implement sustainable forest management and deforestation control to achieve the FOLU Net Sink 2030 policy (MoEF Citation2022b).

FLR can lead to significant consequences like deforestation, degradation, and fragmentation. By carefully considering the environmental and biodiversity aspects, a balance between FLR, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation can be achieved through several key principles:

Landscape-based management: Developing regional strategies to achieve a sustainable and climate-proof society through adequate spatial planning can minimize negative impacts arising from deforestation and fragmentation in land redistribution (Arts et al. Citation2017; Pinto-Correia et al. Citation2018).

Strengthening ESIA (Environment and Social Impact Assessment) in the process of FLR: Adopting the Mitigation Hierarchy approach can effectively minimize development’s impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services. It involves a series of actions to anticipate and avoid impacts on biodiversity, followed by rehabilitation, restoration, and replacement if necessary (CSBI Citation2015).

Maintaining green space and biodiversity hotspot areas: to preserve environmental integrity, it is essential to increase green space areas, high conservation value areas, and biodiversity hotspots, especially located on cultivated land (Molotoks et al. Citation2017; MoEF Citation2022e).

In order to achieve a balance between economic growth and environmental protection, policies should prioritize sustainable resource exploitation, improve governance, adopt environmental regulations, and engage stakeholders. This requires multisectoral measures that promote green development and resource efficiency, as well as policy alignment and stakeholder participation (Zhang et al. Citation2024).

9. Conclusion

FLR is a government effort to modify the distribution of land ownership and provide more equitable access to forest resources. The implementation of FLR in Indonesia holds significant relevance in addressing various national programs, such as SF, TORA, FE, and national infrastructure development. As a policy approach, FLR, holds the potential to significantly impact both biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation efforts. The implementation of the forest land distribution policy involves three key principles: 1) Developing regional strategies through spatial planning for a sustainable and climate-resilient society; 2) Adopting a mitigation hierarchy to predict and prevent biodiversity damage; 3) Increasing green space, conserving high-value areas, and enhancing biodiversity hotspots, especially on farmland. This policy also aims to consolidate habitats and connect fragmented forest patches, promoting wildlife movement and genetic diversity for healthier ecosystems and species adaptability in changing environments.

Author’s contribution

Authors as the main contributors are Hendra Gunawan, Budi Mulyanto, Sri Suharti, Subarudi, Pratiwi, Endang Karlina, Rozza Tri Kwatrina, Asmanah Widarti, Raden Garsetiasih, Reny Sawitri and Titi Kalima with contribution: 1) Define Topic and Purpose, 2) Methodology: Establish a Clear Framework, 3). Literature Review: Search, Select, and Analyze, 4) Writing the original draft, 5) Revise, Edit, and Seek Feedback, 6) Finalize the Text, 7) Create a Bibliography, and 8) Proofread; Irma Yeny, Ari Nurlia, Edwin Martin, Desmiwati, Mariana Takandjandji, NM Heriyanto, Sulistya Ekawati and Rachman Efendi, with contribution: (1), (2), (3) (4), (5), and (7). Authors as the member contributors are Anita Rianti, Vivin Silvaliandra Sihombing, Said Fahmi, and Fenky Marsandi with contribution: (2), (3), (4), and (5).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, and all parties who helped in data collecting and writing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Notes

1 Land of Agrarian Reform Objects, hereinafter abbreviated as TORA is land controlled by the state and/or land that has been owned by the community to be redistributed or legalized (President of The Republic of Indonesia Regulation Number 86 of 2018 about Agrarian Reform).

2 Food Estate is a large-scale food business that is a series of activities carried out to utilize natural resources through human efforts by utilizing capital, technology, and other resources to produce food products to fulfill human needs in an integrated manner including food crops, horticulture, plantations, livestock, and fisheries in a Forest Area (Regulation of The Minister of Environment and Forestry of The Republic of Indonesia Number P.24/Menlhk/Setjen/Kum.1/10/2020 about Provision of Forest Area for Food Estate Development).

3 Forest Area with Special Management hereinafter abbreviated as KHDPK is a state forest area with protection and production functions in Central Central Java, East Java, West Java, and Banten Provinces, whose management is not carried out by the government, and Banten Province whose management is not handed over to state-owned enterprises in the field of forestry (Regulation of The Minister of Environment and Forestry of The Republic of Indonesia Number 4 of 2023 about Social Forestry Management in Forest Areas With Special Management).

4 Forest Village Community Development (PMDH) is a forest management strategy that aims to reduce the poverty level of forest village communities, provide optimum benefits and achieve forest sustainability.

5 Community Based Forest Management (PHBM) is a forest management scheme that gives space to the village community around the forest as the main actor.

6 Kulin KK is a forest management scheme in the form of cooperation between forest communities and Perhutani, both in production and protected forests. Communities that have already managed Perhutani land are allowed to apply for cooperation with Perhutani so that their activities become legal.

7 Social Forestry Forest Utilization Permit (IPHPS) is one form of social forestry program in Perum Perhutani’s working area to overcome the problem of agricultural land use on forest land without planting forest staple crops.

References

- Achmad B, Purwanto RH. 2014. Peluang adopsi system agroforestry Dan Kontribusi Ekonomi Pada Berbagai Pola Tanam Hutan Rakyat Di Kabupaten Ciamis. J Environ. 14(1):15–26.

- A’Dani F, Sukayat Y, Setiawan I, Judawinata G. 2021. Pandemic Covid-19: the rise and fall of agriculture strategy of maintaining the availability of rice farmer staple food in their household during Covid-19 pandemic (case study: Pelem Village, Gabus District, Grobogan Regency, Central Java). JPMIBA. 7:309–316. doi: 10.25157/ma.v7i1.4529.

- Afifah IN, Suprijono A. 2020. Pengelolaan Hutan di Jawa dan Madura: kajian tentang Kebijakan Eksploitasi Hutan Tahun 1913-1932. AVATARA, e-J Hist Edu. 8(1): 1–8.

- Ahrends A, Hollingsworth PM, Ziegler AD, Fox JM, Chen H, Su Y, Xu J. 2015. Current trends of rubber plantation expansion may threaten biodiversity and livelihoods. Glob Environ Ch. 34:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.002.

- Alvian F, Mujiburohman DA. 2022. Implementasi Reforma Agraria Pada Era Pemerintahan Presiden Joko Widodo. JTA. 5(2):111–126. doi: 10.31292/jta.v5i2.176.

- Ameray A, Bergeron Y, Valeria O, Montoro Girona M, Cavard X. 2021. Forest carbon management: a review of silvicultural practices and management strategies across boreal, temperate and tropical forests. Curr Forestry Rep. 7(4):245–266. doi: 10.1007/s40725-021-00151-w.

- Aminuddin B, Ghulam M, Abdullah WY, Zulkefli M, Salama R. 2005. Sustainability of current agricultural practices in the Cameron Highlands, Malaysia. Water Air Soil Pollut: focus. 5(1–2):89–101. doi: 10.1007/s11267-005-7405-y.

- Ardiansyah F, Marthen AA, Amalia N. 2015. Forest and land-use governance in a decentralized Indonesia: a legal and policy review. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- Arifien Y, Anggarawati S, Wibaningwati DB. 2021. The influence of farmer behavior and motivation in land conservation on farmers’ income in the upper Ciliwung Watershed, Bogor Regency. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 686(1):012015. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/686/1/012015.

- Arts B, Buizer M, Horlings L, Ingram V, van Oosten C, Opdam P. 2017. Landscape approaches: a state-of-the-art review. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 42(1):439–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060932.

- Auliyani D. 2020. Upaya Konservasi Tanah dan Air pada Daerah Pertanian Dataran Tinggi di Sub-Daerah Aliran Sungai Gandul. JIPI. 25:382–387. doi: 10.18343/jipi.25.3.382.

- Austin KG, Schwantes A, Gu Y, Kasibhatla PS. 2019. What causes deforestation in Indonesia? Environ Res Lett. 14(2):024007. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaf6db.

- Azizi J, Zarei N, Ali S. 2022. The short- and long-term impacts of climate change on the irrigated barley yield in Iran: an application of dynamic ordinary least squares approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 29(26):40169–40177. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19046-9.

- Baderi F. 2018. Kerusakan Lingkungan Hidup dan Pembangunan Infrastruktur. Jakarta: harian Ekonomi Neraca. [accessed 2023 May]. https://www.neraca.co.id/article/103568/kerusakan-lingkungan-hidup-dan-pembangunan-infrastruktur.

- Barrow CJ, Chan NW, Masron TB. 2010. Farming and other stakeholders in a tropical highland: towards less environmentaly damaging and more sustainable practices. J Sustain Agri. 34(4):365–388. doi: 10.1080/10440041003680205.

- Basundoro AF, Sulaeman FH. 2022. Meninjau Pengembangan Food Estate Sebagai Strategi Ketahanan Nasional pada Era Pandemi COVID-19. J Lemhannas RI. 8(2):27–41. doi: 10.55960/jlri.v8i2.307.

- BBC. 2020. Food estate: proyek lumbung pangan di hutan lindung, pegiat lingkungan peringatkanbencana dan konflik dengan masyarakat adat ‘tidak terhindarkan’. Jakarta: BBC; [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-54990753.

- Bradley P, Yee S. 2015. Using the DPSIR framework to develop a conceptual model: technical support document. Vol. EPA/600/R-15/154. Washington, D. C.: US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. Atlantic Ecology Division.

- Budiono R, Nugroho B, Hardjanto, Nurrochmat DR. 2018. The dynamics of forest hegemony in Indonesia. JAKK. 15(2):113–126. doi: 10.20886/jakk.2018.15.2.113-126.

- CBD. 2022. Nations adopt four goals, 23 targets for 2030 in landmark UN biodiversity agreement. Kunming-Montreal: Convention on Biological Biodiversity; [accessed 2023 July]. https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022.

- Charnsungnern M, Tantanasarit S. 2017. Environmental sustainability of highland agricultural land use patterns for Mae Raem and Mae Sa watersheds, Chiang Mai province. Kasetsart J Soc Sci. 38(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.kjss.2016.04.001.

- Choong ET, Wirakusumah RS, Achmadi SS. 1990. Mangrove forest resources in Indonesia. For Ecolog Manag. 33–34:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(90)90183-C.

- Chovancová B. 2014. Needs analysis and Esp course design: self-perception of language needs among pre-service students. Stud Log Gramm Rhetor. 38(1):43–57. doi: 10.2478/slgr-2014-0031.

- Creswell JW. 2014. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. USA: SAGE.

- Crist E, Mora C, Engelman R. 2017. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science. 356(6335):260–264. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2011.

- CSBI. 2015. A cross-sector guide for implementing the Mitigation Hieharchy. UK: The Biodiversity Consultancy Ltd.

- Danurdara DGAO. 2023. Permasalahan dalam Pembukaan Lahan Gambut pada Program Food Estate. JPT. 7(2):4918–4924.

- Darmawan A, Prasetyo L, Tsuyuki S. 2009. Monitoring agricultural expansion during the economic crisis in Indonesia: a case study of the rawa Danau Nature Reserve. JFP. 14(2):53–66. doi: 10.20659/jfp.14.2_53.

- Dhani R. 2015. Perkembangan Hukum Kehutanan Dan Faktor-Faktor Penghambat Pemberantasan Illegal Logging Dari Sisi Undang-Undang Nasional. [accessed 2023 May]. https://www.academia.edu/11315953/PERKEMBANGAN_HUKUM_KEHUTANAN_DAN_FAKTOR_FAKTOR_PENGHAMBAT_PEMBERANTASAN_ILLEGAL_LOGGING_DARI_SISI_UNDANG_UNDANG_NASIONAL.

- Ditjen PDASRH. 2021. Peta Mangrove Nasional tahun 2021. Jakarta: direktorat Konservasi Tanah dan Air, Ditjen PDASRH, KLHK.

- Djoko IE. 2020. Menteri Pertahanan RI Sebagai Leading Sector Dalam Pengembangan Food Estate Bekerjasama Dengan Menteri PUPR dan Mentan. WIRA Media Inforamsi Kementerian Pertahanan. Jakarta: kementerian Pertahanan Republik Indonesia.

- Ekawati S. 2019. Evaluasi Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Sekitar Hutan: Untuk memastikan tercapainya Perhutanan Sosial. Jogyakarta: PT. Kanisius.

- Ekawati S, Budiningsih K, Sylviani Suryandari E, Hakim I. 2015. Kajian Tinjauan Kritis Pengelolaan Hutan di Pulau Jawa. PolBrief, Pusat Penelitian Dan Pengembangan Sosial Ekonomi, Kebijakan Dan Perubahan Iklim. 9(1):1–8.

- Eryan A, Shafira D, Wongkar EELT. 2020. Analisis Hukum Pengembangan Food Estate di Kawasan Hutan Lindung. Jakarta: Indonesian Centre for Environment Law.

- Fadillah, AN, Sisgianto, Loilatu, MJ, 2021. The urgency of food estate for national food security in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. JGPI 1(1):35–44. doi: 10.53341/jgpi.v1i1.8.

- FAO. 2022. Voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests in the context of national food security. Rome, Italy: food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations.

- Ferdaus RM, Iswari P, Kristianto ED, Muhajir M, Diantoro TD, Septivianto S. 2014. Rekonfigurasi Hutan Jawa: Sebuah Peta Jalan Usulan CSO. Yogyakarta: Biro Penerbitan ARuPA.

- Fisher MR, Dhiaulhaq A, Sahide MAK. 2019. The politics, economies, and ecologies of Indonesia’s third generation of social forestry: an introduction to the special section. FS. 3(1):152–170. doi: 10.24259/fs.v3i1.6348.

- Fitri NN. 2018. Dampak Pembangunan Infrastruktur Jalan Tol Terhadap Kondisi Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat: Studi Kasus di Kecamatan Grati, Kabupaten Pasuruan. Jember, Jawa Timur: Universitas Jember.

- Foley J, Ramankutty N, Brauman K, Cassidy E, Gerber J, Johnston M, Mueller N, O’Connell C, Ray D, West P, et al. 2011. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature. 478(7369):337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10452.

- Fox J, Castella J-C, Ziegler A, Westley S. 2014. Expansion of rubber mono-cropping and its implications for the resilience of ecosystems in the face of climate change in Montane Mainland Southeast Asia. Glob Environ Res. 18:145–150.

- Galgani P, Woltjes G, de Adlehart TR, de Groot RH, Varoucha E. 2021. Land use, land use change, biodiversity and ecosystem Services. Wageningen: echte en Eerlijke Prijs voor Duurzame Producten.

- Gari SR, Newton A, Icely JD. 2015. A review of the application and evolution of the DPSIR framework with an emphasis on coastal social-ecological systems. Ocean Coast Manag. 103:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.11.013.

- Gibbs HK, Ruesch AS, Achard F, Clayton MK, Holmgren P, Ramankutty N, Foley JA. 2010. Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107(38):16732–16737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910275107.

- Golar G, Malik A, Muis H, Herman A, Nurudin N, Lukman L. 2020. The social-economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic: implications for potential forest degradation. Heliyon. 6(10):e05354. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05354.

- Greenpeace. 2022. Indonesia’s food estate program: feeding the climate crisis. Jakarta: greenpeace.

- Gunawan H, Sugiarti S. 2015. Perlunya penunjukan kawasan konservasi baru untuk mengantisipasi degradasi keanekaragaman hayati akibat perubahan RTRW di Kawasan Wallacea (Lesson Learnt Inisiasi Pengusulan Taman Nasional Mekongga, Sulawesi Tenggara). BioWallacea. 1(3):122–133.

- Gunawan, H, Yeny, I, Karlina, E, Suharti, S, Mulyanto, B, Ekawati, S, Garsetiasih, R, Sumirat, BK, Sawitri, R, Heriyanto, NM, et al. 2022. Integrating social forestry and biodiversity conservation in Indonesia. Forests. 13(12), 2152. doi: 10.3390/f13122152.

- Haddad N, Brudvig L, Jean C, Davies K, Gonzalez A, Holt R, Lovejoy T, Sexton J, Austin M, Collins C, et al. 2015. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth ecosystems. Sci Adv. 1(2):e1500052. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500052.

- Hardiyanto B. 2015. Jalan Menuju Hutan Subur Rakyat Makmur. Jakarta: PT. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Haryati U. 2014. Karakteristik Fisik Tanah Kawasan Budidaya Sayuran Dataran Tinggi, Hubungannya dengan Strategi Pengelolaan Lahan. JSL. 8(2):125–138.

- Hosonuma N, Herold M, De Sy V, De Fries RS, Brockhaus M, Verchot L, Angelsen A, Romijn E. 2012. An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environ Res Lett. 7(4):044009. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044009.

- Houghton RA, House JI, Pongratz J, van der Werf GR, DeFries RS, Hansen MC, Le Quéré C, Ramankutty N. 2012. Carbon emissions from land use and land-cover change. Biogeosciences. 9(12):5125–5142. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-5125-2012.

- Ihza KN. 2020. Dampak Covid-19 Terhadap Usaha Mikro Kecil Dan Menengah (UMKM) (Studi Kasus UMKM Ikhwa Comp Desa Watesprojo, Kemlagi, Mojokerto). JIP. 1(1):1325–1330.

- Ilman, M, Dargusch, P, Dart, P, Onrizal. 2016. A historical analysis of the drivers of loss and degradation of Indonesia’s mangroves. Land Use Policy. 54:448–459. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.010.

- Iskandar Silalahi MD, Hasan D, Nurlinda I. 2011. Kebijakan Perubahan Kawasan Hutan dalam Pengelolaan Berkelanjutan. Bandung: Unpad Press.

- Ito T, Rachman N, Savitri L. 2014. Power to make land dispossession acceptable: a policy discourse analysis of the Merauke integrated food and energy estate (MIFEE), Papua, Indonesia. J Peasant Stud. 41(1):29–50. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2013.873029.

- Jansen LJM, Kalas PP. 2023. Improving governance of tenure in policy and practice: Agrarian and environmental transition in the Mekong region and its impacts on sustainability analyzed through the ‘Tenure-Scape’ Approach. Sustainability. 15(3):1773. doi: 10.3390/su15031773.

- Jusmalinda, J, Asmin F. 2020. Dampak Pemberitaan Penyebaran Covid Terhadap Pengelolaan Hutan Sumatera Barat. JPN. 5:55-68. doi: 10.30559/jpn.v5i1.181.

- Kholil K, Dewi I. 2015. Evaluation of land use change in the upstream of Ciliwung watershed to ensure sustainability of water resources. Asian J Water Environ Pollut. 12:11–19.

- Kristensen P. 2004. DPSIR framework. Workshop on a comprehensive/detailed assessment of the vulnerability of water resources to environmental change in Africa using river basin approach; p. 27–29. September 2004; Nairobi, Kenya.

- Kuncoro M, Suyatna H, Sadono R, Susilo S, Nairobi Syafei R, Ratih A, Tyas DW, Prajulianto A, Lestari L. 2018. Dampak Perhutanan Sosial: Perspektif Ekonomi, Sosial dan Lingkungan. Jakarta: ministry of Environment and Forestry.

- Kuswanda W, Sunandar A. 2018. Analysis of land use change and its relation to land potential and elephant habitat at Besitang Watershed, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 20(1):350–358. doi: 10.13057/biodiv/d200141.

- Laksana TG, Nurdiansyah D, Nugraha NAS, Ramadhani RD. 2022. Peningkatan Pemasaran Produk yang Less Contact di Desa Wisata Adiluhur Melalui Pemanfaatan Teknologi Informasi Di masa Pandemi Covid-19. JPKM. 2(2):1093–1102. doi: 10.47492/eamal.v2i2.1537.

- Larson AM. 2013. Hak Tenurial dan Akses ke Hutan Manual Pelatihan untuk Penelitian. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

- Lasminingrat L, Efriza E. 2020. The development of national food estate: the Indonesian food crisis anticipation strategy. JPBH. 10(3):229. doi: 10.33172/jpbh.v10i3.1110.

- Laurance WF, Goosem M, Laurance SGW. 2009. Impacts of roads and linear clearings on tropical forests. Trends Ecol Evol. 24(12):659–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.009.

- Law of The Republic Indonesia Number 41 of 1999 Concerning Forestry. 1999. Indonesia.

- Lopez-Feldman A, Chávez C, Velez M, Bejarano H, Chimeli A, Feres J, Robalino J, Salcedo R, Viteri C. 2020. Environmental impacts and policy responses to Covid-19: a view from Latin America. Environ Resour Econ, 1-6. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00460-x.

- Lubis MS, Munawir Z, Matondang SA. 2021. Planning the food estate for community development and welfare. J Environ Manag Tour. 12(5):1263–1268. doi: 10.14505//jemt.12.5(53).11.

- Lynam J. 2022. The highland perennial farming system Sustainable intensification and the limits of farm size. London: Routledge.

- Madonna EA. 2019. Penerapan Hak Masyarakat Hukum Adat dalam Pengelolaan Hutan di Indonesia. BHL. 3(2):264–278. doi: 10.24970/jbhl.v3n2.19.

- Mallik AU, Rahman H. 1994. Community forestry in developed and developing countries: a comparative study. For Chron. 70(6):731–735. doi: 10.5558/tfc70731-6.

- Margono BA, Turubanova S, Zhuravleva I, Potapov P, Tyukavina A, Baccini A, Goetz S, Hansen MC. 2012. Mapping and monitoring deforestation and forest degradation in Sumatra (Indonesia) using Landsat time series data sets from 1990 to 2010. Environ Res Lett. 7(3):034010. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034010.

- Maskun A, Naswar Assidiq H, Bachril SN. 2021. Palm oil cultivation on peatlands and its impact on increasing Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions. IOP Conf Ser : Earth Environ Sci. 724(1):012092. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/724/1/012092.

- Maskun NM, Nur SS, Bachril SNA, Mukarramah NH. 2021. Detrimental impact of Indonesian food estate policy: conflict of norms, destruction of protected forest, and its implication to the climate change. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 824(1):012097. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/824/1/012097.

- Masripatin N, Rachmawaty E, Suryanti Y, Setyawan H, Farid M, Iskandar N. 2017. Strategi implementasi NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution). Jakarta: Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim, Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan.

- Maxim L, Spangenberg JH, O’Connor M. 2009. An analysis of risks for biodiversity under the DPSIR framework. Ecol Econ. 69(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.03.017.

- Ministry of Public Work. 2010. Dampak Positif dan Negatif dari Pembangunan Infrastruktur Jalan. Jakarta: Ministry of Public Work.

- Mishra A, Humpenöder F, Churkina G, Reyer CPO, Beier F, Bodirsky BL, Schellnhuber HJ, Lotze-Campen H, Popp A. 2022. Land use change and carbon emissions of a transformation to timber cities. Nat Commun. 13(1):4889. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32244-w.

- MoEF. 2016. Regulation of The Minister 0f Environment annd Forestry Number P.83/Menlhk/Setjen/Kum.1/10/2016 Concerning Social Forestry. Jakarta: Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

- MoEF. 2019. Regulation of the Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia Number P.23/Menlhk/Setjen/Kum.1/5/2019 Regarding Strategic Roads in Forest Areas. Jakarta: ministry of Environment and Forestry.

- MoEF. 2020. Status Kehutanan Indonesia Tahun 2020. Jakarta: Ministry of Environment and Fofrestry.

- MoEF. 2021a. Minister of Forestry Regulation No. 7 of 2021 concerning Forestry Planning, Changes in the Designation of Forest Areas and Changes in the Function of Forest Areas, and Use of Forest Areas. Jakarta: Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

- MoEF. 2021b. Refleksi Akhir Tahun: Capaian Tora dan Perhutanan Sosial di Tahun 2021. Jakarta: Ministry of Environment and Forestry; [accessed 2023]. http://ppid.menlhk.go.id/berita/siaran-pers/6330/capaian-tora-dan-perhutanan-sosial-di-tahun-2021.

- MoEF. 2022a. Adaptation communication, directorate general of climate change. Jakarta: Ministry of Environment and Forestry.