ABSTRACT

This article explores the interactions between social policies and exchanges of support between parents aged 50 and over and their adult children in Italy and South Korea. In both countries, families are predominantly responsible for financial and care support to dependent members. However, in the mid-2010s, social security systems, labour market arrangements and family policies allocated resources between age groups in different proportions, favouring pensioners in Italy and prime-age workers in South Korea. Arguably, this difference may influence and interact with exchanges of support within families. Harmonised data for 2012–2013 from surveys of ageing are used to compare exchanges of financial support, instrumental care and intergenerational co-residence between parents aged 50 and above and their adult children. In Italy, where societal transfers favour older generations, intergenerational transfers from parents to children are large, and children provide complementary forms of help to ageing parents. In South Korea, where later-life protection is limited, parents are more heavily dependent upon adult children for financial and care support. The findings add to the existing literature on the relationship between societal and family transfers in European welfare regimes by exploring these interactions in broader contexts and policy areas.

Introduction

This article explores the interactions between social policies and exchanges of support between parents aged 50 and above and their adult children in Italy and South Korea (henceforth referred to as ‘Korea’) in 2012–2013. Italy and Korea are familialistic societies, where responsibility for financial and care support is predominantly assigned to families rather than to the state or the market (Saraceno, Citation2016). In both countries, family members rely strongly upon one another for financial support and informal care. However, in the period considered, social policies allocated resources between age groups in different proportions, favouring those born before the 1960s in Italy, and younger adults in Korea.

Previous studies of the interrelationships between societal transfers and family support have focussed on how different family policy regimes relate to intergenerational family transfers in Western Europe (Deindl & Brandt, Citation2011; Igel, Brandt, Heberkern, & Szydlik, Citation2009). This article examines how the allocation of resources between generations at the country level interacts with exchanges of support between parents aged 50 or more and their offspring in one familialistic country in Southern Europe and one in East Asia. Italy and Korea are compared with respect to a broad range of policies, including pensions, benefits, social services and labour market arrangements, to show how societal transfers in the mid-2010s favoured different generations in the two countries. Using harmonised survey data, intergenerational support is compared across three dimensions: financial transfers; exchanges of instrumental support (in the form of grandchild care, personal care and help with daily activities or household chores); and intergenerational co-residence, which facilitates support through in-kind transfers and cost-sharing (Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012).

Italy and Korea are treated here as homogenous countries, thereby overlooking wide regional disparities in socioeconomic and policy characteristics within each country. There are limitations in comparing two such different contexts, because the concept of intergenerational support may not be directly translatable across cultures, or may be manifested in ways that are not captured by the data. Nevertheless, the comparison is justified due to the similarities in the importance of intergenerational family support, and the differences in the generational allocation of resources between the two countries.

Conceptualising intergenerational support

Intergenerational support is defined here as the giving and receiving of money, care and help between middle-aged or older parents and their adult children, directly and/or through shared living arrangements. Studies of European countries using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, Citation2013) have found financial support to be predominantly from parents to children, while personal care and help with daily activities follow more mixed trajectories, with middle-aged and older parents commonly providing care for grandchildren and receiving care and help from their offspring at advanced ages (Brandt & Deindl, Citation2013). The extent of co-residence between generations varies across European countries according to social policies and cultural preferences (Albertini & Kohli, Citation2013). The limited studies of intergenerational support in East Asia available suggest that exchanges of support may follow different directions from those prevalent in Europe: intergenerational support flows mainly from children to parents and, despite changes in contemporary intergenerational relations; co-residence between generations remains a common form of old-age support, connected to cultural norms of filial responsibility (Lin & Yi, Citation2013).

Authors attempting to disentangle causation conceptualise intergenerational support as the product of interactions between circumstances at the individual, family and country level (Albertini, Citation2016). At the individual and family level, intergenerational support is seen as the result of need and opportunity structures, so that the likelihood of transfers increases when one family member needs instrumental or financial help, and another member possesses the necessary resources. At the country level, welfare regimes have been hypothesised to influence exchanges of support alongside demographic and cultural factors (Szydlik, Citation2008).

The literature on the influence of societal transfers on family exchanges revolves around the concepts of ‘crowding-out’ and ‘crowding-in’ of family support by welfare policies. The ‘crowding-out’ hypothesis predicts that increased public transfers and services to families will make family support less necessary, therefore reducing the overall volume of intergenerational exchange. By contrast, ‘crowding-in’ envisages a scenario in which increased generosity from the state prevents families from becoming overburdened, and allows beneficiaries to redistribute resources to their family members, thus producing an overall increase in intergenerational transfers (Kunemund & Rein, Citation1999). Studies of European countries using multilevel analyses of SHARE survey data have found evidence for both these theories (Deindl & Brandt, Citation2011; Igel et al., Citation2009). In line with these results, the ‘specialisation hypothesis’ between family members and the state in the provision of support has been developed with reference to the European context. Specialisation implies that higher societal transfers to families will crowd out essential, intensive support from relatives, but will promote more complementary, less demanding forms of help (Brandt & Deindl, Citation2013). Specialisation between societal and family transfers is commonly exemplified by a dichotomy between the North and South of Europe. The Scandinavian countries belonging to the social democratic welfare regime type, in which service provision for families is extensive, display a higher frequency of informal family help, but a lower average intensity of support, whilst in Mediterranean countries, where the degree of state support to families is at the lower end of the spectrum, family care appears to be less frequent, but more intensive because aimed at more critical needs. The UK and Central European countries perform somewhere in between these two extremes (Igel et al., Citation2009).

Other aspects of the relationship between societal and family transfers remain unexplored. First, the existing literature focuses mainly on how social services and expenditure on families are reflected in different intergenerational support transfer regimes (Brandt & Deindl, Citation2013). However, in societies in which family members are primarily responsible for financial and care support for one another, the relative allocation of resources to different age groups might be expected to interact with intergenerational exchanges of support within families. In particular, it is interesting to consider whether and how the crowding-in, crowding-out and specialisation hypotheses can be applied to a broader range of social policies allocating resources between generations. These include pensions, benefits to working-age individuals and labour market structures alongside social services and cash transfers. Secondly, the literature has mainly focussed on Western Europe, where basic old-age security is generally guaranteed by public or private pensions and old-age benefits (Igel et al., Citation2009; Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012). However, these transfers are still relatively underdeveloped in East Asia. The distribution of economic resources between generations is therefore expected to differ substantially between our two case studies, which in turn may result in different regimes of intergenerational family exchange.

Contextualising intergenerational support in Italy and Korea

Improvements in life expectancy and persistently low fertility have resulted in Italy having one of the oldest populations in the world, and Korea one of the most rapidly ageing, making intergenerational support a highly significant issue in both countries (UN, Citation2017).

By the mid-2010s, both countries had rapidly ageing societies in which family members relied heavily upon one another in responding to financial and care needs, but in which social policies allocated resources in different proportions to older and younger generations, favouring those born before the 1960s in Italy and those born after that period in Korea. The comparison of intergenerational support between Italy and Korea is undertaken here to shed light on how parent–child transfers of money and care relate to the level of societal support for different generations.

Reliance on intergenerational family support

Despite their geographical distance, Italy and Korea share striking affinities with respect to the importance assumed by intergenerational exchanges of support within families.

Regarding welfare policies, both countries can be considered familialistic, a term indicating the assumption, on the part of the state, that families are mainly responsible for the provision of support to their dependent members (Saraceno, Citation2016). This assumption may be implicit, as indicated by the absence of family care services, or explicit, as stated in measures reinforcing the family caring function, such as cash transfers to carers (Leitner, Citation2003). Housing policies contribute to fostering family members’ interdependence, since the scarce provision of mortgages and housing finance makes parental bequests and inheritances the main channels of access to homeownership (Di Feliciantonio & Aalbers, Citation2017; Ronald & Jin, Citation2010). Because in the two countries family care is predominantly women’s work, familialism also carries an implicit assumption about the division of gender roles (Leitner, Citation2003).

Familialistic policies in Italy and Korea coexist with highly segmented labour markets, characterised by a division between secure and long-term formal employment on the one hand, and an informal sector with scarce social protection on the other (Garibaldi & Taddei, Citation2013; Hwang & Lee, Citation2012). In Italy, dualism is the result of a process of labour market liberalisation, which, since the 1990s, has progressively made it easier for firms to hire on a fixed-term basis. The reform process has introduced flexibility at the margin, with temporary contracts created without affecting the position of workers in long-tenure jobs (Berloffa & Modena, Citation2012). In a context of low economic growth, the 2008 financial crisis resulted in a sharp increase in unemployment and in the deepening of earnings differentials between those in long-tenure jobs and those employed on a fixed-term basis (Jin, Fukahori, & Morgavi, Citation2016). Labour market liberalisation is also at the root of the Korean dualism, which is based on a distinction between the formal corporate sector and the informal sector, with very little mobility between the two (Jones & Fukawa, Citation2016). The marked growth of precarious work in Korea occurred after the 1997 financial crisis, which led to social polarisation and extensive casualisation of labour, in particular though the spread of self-employment (Hwang & Lee, Citation2012).

In both countries, labour market dualism has fostered socioeconomic inequalities. The occupationally segmented nature of the Italian and Korean welfare states implies that formal sector workers receive the main share of social protection (Estevez-Abe, Yang, & Choi, Citation2016). Workers in low-paid, temporary and non-regular jobs, as well as the self-employed, are less protected against unemployment and poverty, despite being disproportionately more exposed to both. In 2012–2013, the dates to which the data used in this article refer, unemployment benefits in both countries were of short duration, and eligibility criteria required recipients to have made contributions to the system for a period of one and a half to two years preceding unemployment, systematically excluding the long-term unemployed and informal sector workers (Corsini, Citation2012; Hwang & Lee, Citation2012). Despite recent labour market reforms, Italy and Korea continue to have unemployment benefits for poorer households that are among the lowest in the OECD (Citation2017a). Moreover, income support measures such as tax credits and cash allowances for low-income households are tied to the receipt of earnings from employment, excluding self-employed and informal sector workers from coverage (Hwang & Lee, Citation2012; Saraceno, Citation2016).

The similarities in welfare policies and labour market arrangements discussed in this section are such that Italy and Korea have been classified as belonging to the same ‘family of nations’, alongside Spain and Japan (Estevez-Abe et al., Citation2016). Within this grouping, Italy and Korea are characterised by stronger family norms shaping expectations of mutual support between parents and children. Analyses of attitudinal and values surveys indicate that, relative to Spain and Japan, Italy and Korea display higher levels of agreement about the importance of family obligations, lower individualism and less equal gender roles (Arpino & Tavares, Citation2013; Iwai & Yasuda, Citation2011).

The combination of familialistic policies, poor social protection for unemployment or labour informality and strong cultural obligations within the family implies that, in both countries, intergenerational transfers of money and care between family members are an essential source of support for those in need.

Differences in societal transfers to older and younger generations

Italy and Korea are similar with respect to the importance of intergenerational transfers of support. However, around the mid-2010s, societal transfers in the two countries allocated resources in opposite directions to different generations, favouring those born before 1960 in Italy, and those born after that in Korea.

Labour market dualism and the spread of the informal sector since the early 2000s have contributed to the widening of socioeconomic differences between generations. In Italy, informal employment has primarily affected younger people. Fixed-term contracts largely apply to new jobs, since those in long-tenure positions remain protected by rigid legislation (Berloffa & Modena, Citation2012). The proportion of temporary workers is highest among people in their 20s and 30s regardless of their level of education, and youth unemployment is widespread (Jin et al., Citation2016). By contrast, in Korea, those born before the 1960s have become over-represented in the informal sector. The rapid technological development of the country has relegated many of them to low-paying service jobs (Jones & Fukawa, Citation2016). Moreover, the seniority wage structure enforced in the corporate sector means that firms find it profitable to lay off workers in their 50s, commonly by offering one-off severance payments; these funds have often been invested by their recipients in small businesses or restaurants, which are very prone to failure (Yang, Citation2014).

The Italian and Korean pension systems differ in the extent to which they provide income security in later life. In Italy, public expenditure on old-age benefits as a percentage of GDP is the highest in the OECD (Citation2016b). Public pensions constitute the main pillar of the pension system and, combined with a set of means-tested benefits for low earners and survivors, they achieve virtually universal coverage of the population aged 65 and over. Average replacement rates are high, at around 80% of previous earnings (OECD, Citation2015b). By contrast, in Korea, later-life protection is scarce. Social security provision is split between the National Pension System (NPS) and private corporate pensions, though the latter are often replaced by severance payments, as noted above. Replacement rates in the NPS are low, around 45% of previous earnings, and neither public nor private pensions cover more than a third of those aged 65 and over (OECD, Citation2015b). Old-age poverty benefits are also underdeveloped. In the period considered, the Basic Pension scheme offered payments of up to 10% of the average earnings of those covered by the NPS, not enough to guarantee economic security; and the Basic Livelihood Security scheme had very low coverage as, to be eligible, recipients had to prove that they had no family member who could support them (Jones & Fukawa, Citation2016).

The differences in the two countries’ social security systems are reflected in differences in middle-aged and older people’s participation in the labour market (OECD, Citation2015b). Around 2015, Italians retired on average earlier than state pension age, due to high replacement rates, low penalties for early exit, and the difficulties faced by older people in finding re-employment after dismissal (Jin et al., Citation2016). Koreans, on the other hand, retired on average 10 years later than state pension age, often induced to continue working in the informal sector by low pension coverage and replacement rates (Yang, Citation2014).

Family policies in the two countries have also favoured the allocation of resources to different age groups. The Italian familialistic welfare model is based on state support for family care for dependent members through cash transfers and tax exemptions, with very limited provision of formal services (Saraceno, Citation2016). With regard to long-term care, the ‘accompanying allowance’ is a cash transfer providing financial support to people with disabilities. In 2013 this allowance covered around 10% of those aged 65 and over and, given the very low coverage of formal care services, it has long represented the main channel of support for frail or dependent older people in the country (Da Roit, Gonzalez Ferrer, & Moreno Fuentes, Citation2013). In the field of child care, on the other hand, the country lacks a coherent policy plan. The decentralisation of childcare services to local authorities has led to coverage rates of care for under-threes ranging from around 30% in the wealthier Northern regions to less than 5% in parts of the South (Vogliotti & Vattai, Citation2015). At the country level, childcare allowances are provided to low-income families, but the level of benefits is low and, as mentioned above, the eligibility criteria exclude self-employed and informal workers. Existing tax deductions for families with children are non-refundable, thus excluding low-income households (Saraceno, Citation2016). Due to the low level of support provided to families, those with young children are more likely to be in poverty, especially large families sustained by a single earner working in an informal or fixed-term job (Barbieri, Cutuli, & Tosi, Citation2012).

In Korea, since the early 2000s, the familialistic model of welfare has evolved towards de-familialisation through the market, with the state subsidising market-based services rather than providing financial assistance to families (Saraceno, Citation2016). Parents of children under the age of six are eligible for childcare subsidies covering between 30% and 100% of childcare expenditure, depending on family income. In 2012, parental leave and reduced working hours were subsidised by the state to facilitate work–family reconciliation for parents, and additional services for families on a low income and with disabled children were provided by local authorities (Chin, Lee, Lee, Son, & Sung, Citation2012). Tax deductions were also granted to parents of children under the age of 20, with additional refundable tax credits for low-income households. But the large expansion in service provision and coverage achieved in childcare has not been matched in the long-term care sector. A compulsory long-term care insurance system, in place since 2008, has funded the rapid expansion of market-based care for frail older people. However, coverage rates are still among the lowest in the OECD (Citation2015a). Major drawbacks of the system are the high share of costs borne by beneficiaries (around 15–20%), the absence of a centralised care management system and the low quality of services provided (Chon, Citation2014).

Public support for higher education funding is also relevant to the societal allocation of resources between generations. In both countries, public spending on tertiary education is low by OECD (Citation2017b) standards, at about 1% of GDP. Thus, parental investments are the predominant means of financing higher education. However, in Italy, tuition fees in public universities are inexpensive relative to both the OECD and the European averages (Citation2017b). In Korea, by contrast, the high cost of attending elite institutions, combined with a heavy focus on educational investments among families and the strong link between the type of university attended and labour market outcomes, lead many lower-income parents to become indebted and to seek employment in the informal sector after official retirement to finance post-secondary education for their children (Kim & Choi, Citation2015).

As a result of all these factors, in the mid-2010s, the income security of those born before the 1960s relative to that of younger people differed widely between the two countries. While in Italy poverty declined with age, reaching a minimum for the 66–75 age group, it rose steeply after the age of 50 in Korea, with around 60% of people over 75 living on less than 50% of the median household income (OECD, Citation2016c).

Comparing intergenerational support between Italy and Korea

In the mid-2010s, transfers among family members were, arguably, an essential source of support for financial and care needs in Italy and Korea. Around the same time, social policies allocated resources in opposite directions to different generations, favouring those born before 1960 in Italy, and those born after that in Korea. This section investigates how transfers of support between parents aged 50 and above and their adult children differed between the two countries in 2012–2013. The aim of the comparison is to build descriptive evidence about the relationship between the societal allocation of resources to different age groups and exchanges of intergenerational support within families.

The sample under study includes people who were aged 50 or more in the year of the survey interview, which is 2012 for Korea and 2013 for Italy. The choice of age 50 as the cut-off for the definition of middle-aged and older people makes it possible to study intergenerational support among Italian and Korean parents born before (or around) 1960. These groups are interesting to compare because in Italy they benefitted from generous societal transfers, but in Korea they were relatively disadvantaged. Such a broad definition of middle-to-older age facilitates an examination of age differences in intergenerational transfers, and allows for comparisons of parents with a range of diverse needs and resources.

The comparison is intended to shed light on how crowding-in, crowding-out and specialisation theories apply to the relationship between parent–child transfers and the societal allocation of resources between generations in two familialistic societies.

Datasets and analysis

Cross-sectional survey data on financial, instrumental and co-residential support were taken from wave 5 of the Italian sample of the SHARE and wave 4 of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) (KEIS, Citation2014; SHARE, Citation2013). These are multidisciplinary surveys on the demographic, socioeconomic, health and family characteristics of older people, and they allow for cross-country comparison by asking very similar sets of questions (Borsch-Supan & Jurges, Citation2005; KLI, Citation2007). SHARE wave 5 was collected in Italy in 2013, while KLoSA wave 4 refers to Korea in 2012.

The study samples were restricted to people aged 50 and above and with at least one living child, and the two datasets were merged after harmonising all relevant variables. The combined sample size is 10,343, consisting of 3036 Italian and 7307 Korean respondents. The difference in sample sizes implies that estimates for Korean respondents have smaller standard errors, however it does not affect the ability to analyse differences between the two countries. All questions in SHARE and KLoSA were asked directly to middle-aged and older parents, who constitute the main units of analysis for this study.

Italian and Korean parents were compared with respect to financial transfers given to and received from children, provision of grandchild care, help and care received from children and intergenerational co-residence. Conventional χ2 tests and logistic regression models with interactions were used to test for the statistical significance of differences between Italy and Korea. Because intergenerational support depends on parental gender (Albertini, Citation2016), all data are described separately for mothers and fathers. Despite both surveys being affected by longitudinal drop-out between the first wave and the one used here, estimates derived using calibrated survey weights suggest that attrition does not affect the representativeness of the samples with respect to the variables of interest (see Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Financial support

Exchanges of financial support between older parents and their adult children are measured using SHARE and KLoSA questions on whether, during the year before the interview, parents had given or received monetary gifts from any of their children. In SHARE Italy, only monetary gifts equal to or above €250 are coded. Using Purchasing Power Parity, this corresponded to 285,700 Korean Won in 2012. Therefore, to achieve comparability, only financial transfers equal to or above that sum in KLoSA were considered.

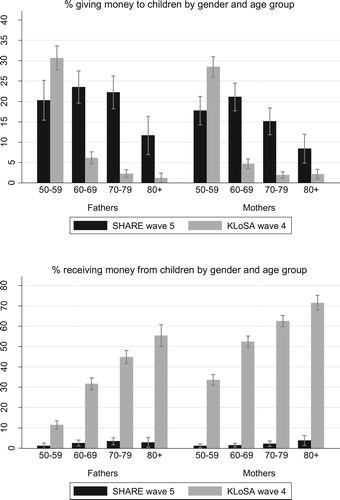

As shown in , monetary gifts in Italy were predominantly from parents to their adult children, and peaked between the parental ages of 60 and 69, possibly owing to receipt of lump-sum retirement payments or to the higher financial support needs of children attempting to set up their own families. In Korea, by contrast, very low proportions of parents financially supported their children beyond age 60, and upward financial support, especially for mothers, increased steeply with parental age.

Figure 1. Exchanges of financial support* between parents aged 50+ and their children (Italy 2013; Korea 2012). Source: Author’s analysis of data from SHARE wave 5 (Citation2013) and KLoSA wave 4 (KEIS, Citation2014). *SHARE codes financial transfers of €250 or above; in KLoSA, only financial transfers equal to or above 285,700 Won are considered (in 2012 €1 =|KRW 1143 using Purchasing Power Parity).

These results point to crowding-out of financial support between societal and family transfers. Generous pensions and old-age benefits combined with low support to younger working-age individuals in Italy are reflected in a net downward flow of monetary gifts, from parents to children. By contrast, societal transfers favouring corporate workers in their 30s and 40s in Korea are reflected in an upward balance of intergenerational transfers of money. In support of the specialisation hypothesis, larger societal transfers to older generations in Italy appear not only to crowd out monetary transfers from children, but also to enable parents to redistribute money to their children, thus increasing the overall volume of exchange.

Provision of care for grandchildren

The provision of care for grandchildren is used to indicate instrumental support from older parents to their adult children’s families. This is measured in both surveys by a question asking respondents who have grandchildren whether, in the year preceding the interview, they cared for them in the absence of either parent. For comparability, the samples were restricted to grandparents who reported providing care to grandchildren under the age of 10. Results from χ2 tests comparing the proportions of grandparents engaged in grandchild care between the two samples indicate that this activity is significantly more common in Italy than in Korea among all age groups ().

Table 1. Percentage of grandparents aged 50+ looking after grandchildren aged 0–10 without the presence of parents over the 12 months preceding the interview, by gender and age group (Italy 2013; Korea 2012).

Childcare service provision is nearly universal in Korea, but sporadic in Italy. The low proportions of Korean grandparents reporting care for grandchildren may be explained by the fact that grandchild care is made unnecessary by the presence of social services, which suggests a crowding-out mechanism. On the other hand, the higher economic security of middle-aged and older people in Italy may allow them to dedicate time to grandchild care, which may not be feasible for Korean grandparents obliged to work for pay by financial necessity.

Care and help from children to parents

Upward instrumental support is measured by indicators for the receipt of help and care by respondents from their adult children. In SHARE, this is the combination of responses to two sets of questions. The first asked respondents whether, over the past year, any child living outside their household had given them personal care or help with daily activities. The second asked whether, over the three months preceding the interview, a child living within the same household helped them with personal care nearly every day. In KLoSA, respondents were asked to name the five people who helped them the most with personal care or daily activities.

Following Igel et al. (Citation2009), in order to distinguish between less-intensive help with household chores and more intensive personal care, reports separate results for parents in good functional health and those suffering from limitations in activities of daily living (ADL). The grouping also accounts for the higher proportions of Italian parents reporting ADL limitations (around 15% of the sample) compared to Koreans (around 5%), which would otherwise result in a misrepresentation of the differences in receipt of help and care. For all groups except men in their 50s, Italians are significantly more likely than Koreans to receive support from their children when healthy. Filial care for parents with functional limitations, however, is higher in the Korean sample, although differences between Italians and Koreans are only statistically significant for mothers in their 60s and 70s.

Table 2. Percentage of parents aged 50+ receiving instrumental help and personal care from children in the 12 months preceding the interview, by gender, age group and ADL status (Italy 2013; Korea 2012).

In 2012–2013, the provision of long-term care services was scarce in both countries, but middle-aged and older Italians with disabilities received an ‘accompanying allowance’. Thus, Italian parents with functional health limitations were able to hire private carers, mostly migrant workers (Di Rosa, Melchiorre, Lucchetti, & Lamura, Citation2012). By contrast, in Korea, care from family members was the only option for those with lower levels of socioeconomic resources. In line with the specialisation hypothesis, stronger support to people with functional limitations in Italy appears to crowd-in filial help to healthy parents, while filial support to middle-aged and older parents in Korea is mainly directed at parents with critical care needs.

Intergenerational co-residence

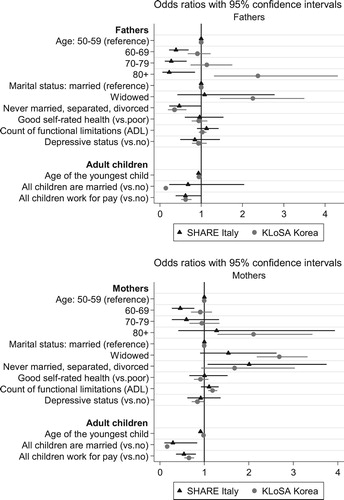

Co-residence between middle-aged and older parents and their adult children can be an important form of intergenerational support, operating through in-kind transfers and/or cost sharing; but it is often hard to identify its main beneficiaries (Isengard & Szydlik, Citation2012). To address the fact that shared living may be a response to the needs of either or both generations, logistic regression models for the probability of living with children were fitted to describe the parental and children’s characteristics associated with intergenerational co-residence. The models were fitted separately by gender and, to test for differences between the two countries, each explanatory variable was interacted with a binary indicator of whether the respondent belonged to the Korean KLoSA – as opposed to the Italian SHARE – sample (see Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). reports selected associations from the logit models.

Figure 2. Selected coefficients* from fully-adjusted logistic regressions for the probability of living with children, by gender (Italy 2013; Korea 2012). Source: Author’s analysis of data from SHARE wave 5 (Citation2013) and KLoSA wave 4 (KEIS, Citation2014). *Additional controls (not shown): Parental education and working status, household wealth, household rural dwelling and presence of grandchildren. All estimates are reported in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

In both countries, co-residence was less likely when adult children were married or employed. However, some differences emerge when comparing the parental characteristics associated with co-residence: while in Italy fathers in their 50s were most likely to live with their children, in Korea being aged 80 or older was associated with co-residence for parents of both genders. Moreover, parental widowhood was associated with co-residence among Korean, but not Italian, respondents. The associations suggest that, while in Italy co-residence mainly benefitted adult children who had not established their independence from the parental home through marriage and/or employment, in Korea it was also a response to the needs of older and widowed parents.

Conclusion

Intergenerational support is a timely issue to investigate in countries with ageing populations and a high degree of interdependence among family members such as Italy and Korea. As the description of social policies and labour markets in the two countries reveals, in 2012–2013 societal transfers allocated financial resources and services in opposite proportions between generations, favouring those born before the 1960s in Italy and younger generations in Korea. The comparison of intergenerational support transfers suggests that these differences are reflected in flows of intergenerational support within families.

In 2012–2013, Italians born before or around 1960 were guaranteed economic security through strong financial support measures. This provision has partly crowded-out financial and care support from their adult children, but has also allowed parents to redistribute resources to younger generations through transfers of money and grandchild care to their offspring. In Korea, by contrast, those born before the 1960s were disadvantaged by the spread of precarious employment before the expansion of the welfare state. Monetary transfers and personal care from adult children partly substituted for societal support to the older generations. However, this may have contributed to a decrease in the volume of intergenerational exchange by reducing the ability of parents to provide support, as well as their adult children’s availability to carry out less essential functions, such as helping with household chores.

This study adds to the literature on the relationships between societal and family transfers in European welfare regimes by exploring these interactions in broader contexts and policy areas than in previous research. The differences between Italy and Korea indicate that intergenerational exchanges of support within families tend to complement societal transfers to different generations. Overall, the results suggest that the specialisation between family support and societal transfers commonly found in studies of family policies in Europe (Brandt & Deindl, Citation2013) is also relevant to policies that allocate resources towards different age groups through pensions, services, cash transfers, benefits, taxation and the labour market. Policy developments in all these areas could therefore usefully take account of the potential redistributive effects of intergenerational family transfers.

The study on which this article is based has important limitations. Due to the limited size of the surveys used, Italy and Korea are treated as homogenous contexts, overlooking within-country regional disparities in socioeconomic conditions and access to services (OECD, Citation2016a, Citation2017c). Moreover, the concept of intergenerational support may not be directly translatable across different cultures. Variations in family norms between the two contexts may be partly driving intergenerational support patterns. In particular, parental responsibility is strongly emphasised in Italy, while respect for filial duty is highly commended in Korean society, as surveys of societal values suggest (Arpino & Tavares, Citation2013; Iwai & Yasuda, Citation2011).

Finally, the argument is based on descriptive evidence, and it refers to Italy and Korea at a specific point in time. Further research is needed formally to test the interactions between societal transfers and intergenerational exchanges of support. Intergenerational inequalities among current cohorts are likely to be transformed in the future, as young people’s employment is more responsive to crises, whereas social security systems tend to be slow in reacting to emerging social risks. An analysis of cohort trends would be necessary to assess how changes in the relative wealth of different generations in each country are reflected in intergenerational support exchanges.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the support received from Professor Emily Grundy, and the comments and suggestions received from the guest editors and reviewers of this themed issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Ginevra Floridi is studying for a PhD in Demography at the London School of Economics, UK. She holds a BSc in Economics from the University of Essex, and MSc’s in Population and Development and in Social Research Methods, from the London School of Economics. Her research focuses on ageing and intergenerational relations in Italy and South Korea.

ORCID

Ginevra Floridi http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1417-2631

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albertini, M. (2016). Ageing and family solidarity in Europe: Patterns and driving factors of intergenerational support. World Bank Policy Research (Working Paper n. WPS7678). Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Albertini, M., & Kohli, M. (2013). The generational contract in the family: An anlaysis of transfer regimes in Europe. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 828–840. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcs061

- Arpino, B., & Tavares, L. P. (2013). Fertility and values in Italy and Spain: A look at regional differences within the European context. Population Review, 52(1), 62–86. doi: 10.1353/prv.2013.0004

- Barbieri, P., Cutuli, G., & Tosi, M. (2012). Families, labour market and social risks. Childbirth and the risk of poverty among Italian households. Stato e Mercato, 22, 391–428. ISSN: 0392-9701.

- Berloffa, G., & Modena, F. (2012). Economic well-being in Italy: The role of income insecurity and intergenerational inequality. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 81(3), 751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.12.022

- Borsch-Supan, A., & Jurges, H. (2005). The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe: Methodology. Mannheim: Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Ageing (MEA).

- Brandt, M., & Deindl, C. (2013). Intergenerational transfers to adult children in Europe: Do social policies matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(1), 235–251.

- Chin, M., Lee, J., Lee, S., Son, S., & Sung, M. (2012). Family policy in South Korea: Development, current status, and challenges. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 53–64. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9480-1

- Chon, Y. (2014). The expansion of the Korean welfare state and its results – focusing on long-term care insurance for the elderly. Social Policy and Administration, 48(6), 704–720. doi: 10.1111/spol.12092

- Corsini, L. (2012). Unemployment insurance schemes, liquidity constraints and re-employment: A three country comparison. Comparative Economic Studies, 54(2), 321–340. doi: 10.1057/ces.2012.9

- Da Roit, B., Gonzalez Ferrer, A., & Moreno Fuentes, F. J. (2013). The new risk of dependency in old age and (missed) employment opportunities: The Southern Europe model in a comparative perspective. In J. Troisi & H. J. Von Kondratowitz (Eds.), Ageing in the Mediterranean (pp. 151–172). Bristol: Policy Press.

- Deindl, C., & Brandt, M. (2011). Financial support and practical help between older parents and their middle-aged children in Europe. Ageing and Society, 31, 645–662. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10001212

- Di Feliciantonio, C., & Aalbers, M. B. (2017). The prehistories of neoliberal housing policies in Italy and Spain and their reification in times of crisis. Housing Policy Debate, doi: 10.1080/10511482.2016.1276468

- Di Rosa, M., Melchiorre, M. G., Lucchetti, M., & Lamura, G. (2012). The impact of migrant work in the elder care sector: Recent trends and empirical evidence in Italy. European Journal of Social Work, 15(1), 9–27. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2011.562034

- Estevez-Abe, M., Yang, J. J., & Choi, Y. J. (2016). Beyond familialism: Recalibrating family, state and market in Southern Europe and East Asia. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(4), 301–313. doi: 10.1177/0958928716657274

- Garibaldi, P., & Taddei, F. (2013). Italy: A dual labour market in transition: Country case study on labour market segmentation (Working Paper n. 144). Geneva: ILO.

- Hwang, D. S., & Lee, B. H. (2012). Low wages and policy options in the Republic of Korea: Are policies working? International Labour Review, 151(3), 243–259. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1223514192

- Igel, C., Brandt, M., Heberkern, K., & Szydlik, M. (2009). Specialization between family and state intergenerational time transfers in Western Europe. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(2), 203–224. SocINDEX with Full Text, Ipswich, MA.

- Isengard, B., & Szydlik, M. (2012). Living apart (or) together? Coresidence of elderly parents and their adult children in Europe. Research on Aging, 34(4), 449–474. doi: 10.1177/0164027511428455

- Iwai, N., & Yasuda, T. (2011). Family values in East Asia: A comparison among Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan based on East Asian social survey 2006. Kyoto: Nakanishiya.

- Jin, Y., Fukahori, R., & Morgavi, H. (2016). Labour market transitions in Italy: Job separation, re-employment and policy implications (Working Paper n. 1291). Paris: OECD.

- Jones, R. S., & Fukawa, K. (2016). Labour market reforms in Korea to promote inclusive growth (Working Paper n. 1325). Paris: OECD.

- KEIS. (2014). The Korean longitudinal study of ageing. Retrieved from http://survey.keis.or.kr/eng/klosa/klosa01.jsp

- Kim, D. H., & Choi, Y. (2015). The irony of the unchecked growth of higher education in South Korea: Crystallisation of class cleavages and intensifying status competition. Development and Society, 44(3), 435–463. Retrieved from http://www.ekoreajournal.net/issue/index.htm

- KLI. (2007). KLoSA wave 1 userguide. Seoul: Korean Labour Institute.

- Kunemund, H., & Rein, M. (1999). There is more to receiving than needing: Theoretical arguments and empirical explorations of crowding in and crowding out. Ageing and Society, 19(1), 93–121. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society

- Leitner, S. (2003). Varieties of familialism: The caring function of the family in comparative perspective. European Societies, 5(4), 22. doi: 10.1080/1461669032000127642

- Lin, J. P., & Yi, C. C. (2013). A comparative analysis of intergenerational relations in East Asia. International Sociology, 28(3), 297–315. doi: 10.1177/0268580913485261

- OECD. (2015a). Health at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. (2015b). Pensions at a glance 2015: OECD and G20 indicators. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. (2016a). OECD economic surveys: Korea 2016. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. (2016b). Pension spending (indicator). Retrieved from https://data.oecd.org/

- OECD. (2016c). Poverty rate after taxes and transfers, by age group. Retrieved from https://data.oecd.org/

- OECD. (2017a). Average net replacement rates over 60 months of unemployment, 2015 (indicator). Retrieved from https://data.oecd.org/

- OECD. (2017b). Education at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. (2017c). OECD economic surveys: Italy 2017. Paris: OECD.

- Ronald, R., & Jin, M. Y. (2010). Homeownership in South Korea: Examining sector underdevelopment. Urban Studies, 47(11), 2367–2388. doi: 10.1177/0042098009357967

- Saraceno, C. (2016). Varieties of familialism: Comparing four Southern European and East Asian welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(4), 314–326. doi: 10.1177/0958928716657275

- SHARE. (2013). Survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Retrieved from http://www.share-project.org/

- Szydlik, M. (2008). Intergenerational solidarity and conflict. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 39(1), 97–114. SocINDEX with Full Text, Ipswich, MA.

- UN. (2017). World population prospects: The 2017 revision. Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat.

- Vogliotti, S., & Vattai, S. (2015). Welfare State: Le politiche della famiglia in un confronto Europeo [Family policies in a European comparison] (Working Paper n.2). Bolzano: Istituto Promozione Lavoratori (IPL).

- Yang, J. J. (2014). The welfare state and income security for the elderly in Korea. In T. R. Klassen & Y. Yang (Eds.), Korea's retirement predicament: The ageing tiger (pp. 39–52). Abigndon: Routledge.