ABSTRACT

In this paper, we examine the impact of Brexit on financial services employment in the UK. Initial estimates suggested that around 10,000 jobs could relocate from London to other EU financial centres as a result of Brexit. Official statistics show that the total number of job relocations that has taken place to date is lower than these estimates, but concerns have been raised concerning ‘missing’ financial services jobs as employment growth has been relatively flat since Brexit. We analyse the geographies of these ‘missing’ jobs and examine the different causes in wholesale and retail banking. Our findings suggest that it is the combination of Brexit alongside the changing nature of financial work itself that best account for ‘missing’ financial services jobs in the UK. As a result, Brexit is far from done and, in the case of financial services, it is likely to be some time before its full impacts are fully understood.

1. Introduction

The impact of Brexit on financial services employment in the UK has been the source of considerable policy and public debate since the UK voted to leave the EU in a referendum on 23 June 2016. During the UK’s membership of the EU, its financial services sector, and London’s financial district in particular deepened its trade with the EU in financial services, building on its long history as an international, rather than predominately domestically focused, financial centre (Kynaston, Citation2002). As a result, in the run up to, and following the referendum, attention increasingly focused on the impacts of Brexit on financial services.

Early estimates made before the UK left the EU, but after the referendum result (i.e. in the Brexit transition period), suggested that in the short term, up to 40,000 jobs could relocate from the UK to other European financial centres whilst over the long term, a further 30–40,000 jobs could relocate when also including jobs closely allied to financial services in legal and professional services (Oliver Wyman, Citation2016). However, most recent employment figures show that these figures overestimated the scale of job relocations from the UK that would happen as a result of Brexit. More recent figures suggest that the number of job relocations stands at closer to 7000 jobs (EY).

However, whilst job relocation figures point to greater resilience within the financial services sector post Brexit than had been predicted, at the same time, employment in financial services according to official statistics from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that the number of people employed in financial services has flatlined since the referendum. This comes despite the fact that as of June 2022, 1.06 million people were employed in financial services in the UK. Estimates suggest that if the rate of job creation had followed its pre referendum trend, there would be between 85,000 and 105,000 more people working in financial services New Financial (Citation2022).

This paradox, that fewer jobs appear to have relocated to Europe whilst at the same time fewer jobs have been created has been labelled a ‘curious case’ of ‘missing’ financial jobs (Pooley Rutter, Citation2022). In this paper, we examine these ‘missing’ jobs. We suggest that the jobs figures point to the need to understand the complex intersection of Brexit related changes to UK financial services which are playing out on a sector that is transforming its labour practices more generally in a number of ways, and in ways that are not limited to the UK. We wish to argue that the value of focusing on ‘missing’ jobs is that it moves attention from job relocations of jobs that were previously in the UK to the equally important question of where jobs are being created, what sort of jobs these are and where.

Our analysis identifies two key dynamics that come together to account for ‘missing’ financial services jobs in the UK. First, employment in financial services in the UK since the Brexit referendum has been relatively flat. This follows a trend that started in the wake of the 2007–8 financial crisis (before that, employment in financial services had been growing strongly since the 1980s). However, behind this general finding lies the fact that job growth has been stronger in key European financial centres, notably Paris and Dublin since Brexit, suggesting that reduced market access has impacted UK financial services in a distinctive way. Moreover, this trend is not uniform geographically across the UK. Employment has declined more markedly in Scotland than in the rest of the UK. We suggest that this may reflect the particular sectoral make up of financial services in Scotland and the classificatory issues for jobs in fintech (on which see Lai & Samers, Citation2021) that has grown particularly strongly in Scotland This demonstrates the need for research to consider the impacts of Brexit for financial services across the UK, and not limit analysis to London’s financial district.

Second, analysis of employment impacts needs to include retail and mid and back-office functions in addition to the high value wholesale financial service jobs that often dominate the Brexit debate. The decline in retail finance employment is an important part of the wider narrative but not immediately attributable to Brexit. This includes the declining retail bank branch network across the UK (Leyshon et al., Citation2006) and the growing trend to move mid and back-office functions to cheaper labour markets, notably in Eastern and Southern Europe. Given the complex interplay of these two factors, we suggest that far from being done, Brexit is being played out within a sector that is itself in a period of profound flux and hence it is likely to be some time before the full impacts of Brexit of UK financial services, and their consequences for wider economic growth, are fully understood.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we specify our methodology, noting the challenges in using employment data in financial services. In section three, we set out the changes for UK-EU financial services trade brought about by Brexit. In the fourth section, we analyse the implications for financial services employment in the UK and assesses the likely explanations for the trends seen. We conclude by reflecting on the implications of these findings, both for empirical understandings of Brexit and conceptual understandings of the nature of work within financial services.

2. Methodology

In order to document, analyse and explain the impacts of Brexit on financial services employment in the UK, we use primary, qualitative data alongside secondary data from financial organisations in the City of London and official labour market statistics. The first stage of the methodology involved a desk-based review of key policy announcements and consultations from UK national and London specific financial services authorities and regulators, alongside their counterparts in the European Commission. The second element of the methodology focuses on the tracking employment levels in financial services from the Workforce Jobs Survey at the Office for National statistics. This provides quarterly data on financial services employment across the United Kingdom, broken down to the national level in the Standard Industrial Classification category of financial services and insurance. It is important to note that because it is hard to precisely set out where the boundary between financial and other related professional services lies, and that this changes as the nature of financial services changes, it is hard to accurately account for the size of the financial services sector. We discuss this further in section four below.

We compare this data with corporate sources of analysis: the consultancy firm EY’s Brexit tracker and analysis from New Financial, a social enterprise cum think tank. Both of these organisations have been tracing the relocation of job, legal entities, and assets from the City of London to other European financial centres as a result of Brexit. The methods deployed by both organisations are similar in that they rely on publicly announced statements from banks, insurers, asset managers and other financial services providers to trace the relocation activities of major financial organisations in London. Both organisations explicitly state their research underestimates the full extent of relocation activity as it focuses on the largest organisations and relies on publicly announced statements.

The final element in the methodology was a series of in-depth qualitative interviews and close dialogue (Clark, Citation1998) with market participants that was undertaken between January 2021 and May 2021 with senior policy makers and financial actors in the City of London. Participants were recruited using non-random sampling methods with the aim of obtaining the perspectives of key stakeholders and decision makers (see Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008 on case study selection in qualitative research). This included UK government ministers, regulators, representatives from the major trade associations for financial services and senior management from financial services organisations. In total, 13 interviews conducted for this research. The interviews were semi-structured, yet fairly open-ended. Interviews lasted between 30 min and one hour and have been transcribed in full. Interviews covered the impact of Brexit on organisational structures in respondents’ organisations including how they traded between the UK and other member states prior to Brexit, their understandings of the relative strengths of different European financial centres (including London) post Brexit, and their assessment of the outlook for European financial services in the future. Interviews were coded thematically by both researchers focusing on evidence cited of corporate and policy networks formation.

3. Brexit and UK financial services

3.1. UK- EU financial services trade during UK single market membership

During the period of UK EU membership between 1973 and 2020, UK financial services, and the City of London in particular, deepened their trade with the EU, building on the longer history of London as an outward looking, international financial centre (Kynaston, Citation2012). To a large extent, this was supported through what is known as passporting. Passporting is an EU policy that permits cross-border supply of financial services between member states. Under passporting arrangements when the UK was an EU member state, a financial services provider based in the UK could sell their products and services to customers in the EU and vice versa. By using passporting, London in particular developed into Europe’s leading international financial centre but considerable trade was also established with other parts of the UK, notably in asset management from Edinburgh. By 2019, the EU accounted for 40% of UK financial services exports (£24 billion) and 32% of UK financial services imports (£6 billion) (UKICE, Citation2021).

These dense trading relations with Europe contributed to the importance of financial services to the UK economy, a trend that developed most significantly following the deregulatory reforms undertaken in the 1980s, collectively known as Big Bang. In 2019, financial, related and auxiliary services, including insurance contributed contributed £164 billion to the UK economy – just over 8% of GDP (ONS, Citation2023). Half of this output was generated in London but there are also significant clusters in cities such as Edinburgh, Leeds and Manchester, and towns such as Swindon, Bournemouth and Northampton. In the first quarter of 2020, there were 1.1 million people employed in financial services, 3.2% of total UK jobs.

Financial service exports are a vital area for the UK economy. In 2019, the UK ran a trade surplus in financial services of £41 billion (House of Commons Library, Citation2022).

3.2. EU-UK financial services trade under the trade and cooperation agreement

The nature of financial services trade with the EU changed profoundly when the UK left the EU with less market access for UK financial services into the EU than when the UK was a member state. The terms of this trade are set out in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), accompanied by specific arrangements for particular sectors, including financial services. For financial services, the TCA is accompanied by a non-binding Joint Declaration committing the UK and the EU to cooperation on matters of financial regulation. This is intended to be facilitated by a memorandum of understanding (MoU). However, although the UK government announced that the technical discussions underpinning the MoU had successfully concluded in March 2021, no formal text has emerged (HM Treasury, Citation2021). Even if the MoU was to come into force, it is no replacement for certainty regarding single-market access for UK financial services firms.

The TCA was the subject of intense negotiation before its agreement on 30 December 2020. The terms of the TCA can be traced back to the Political Declaration of October 2019, agreed by the UK and the EU alongside the Withdrawal Agreement. This made it clear that UK financial service firms would lose passporting rights into the single market. It was also clear that these would not be replaced under the terms of the TCA and that, instead, single market access for UK firms – and access to the UK market for EU firms – would be governed through equivalence decisions. Throughout the negotiations, the EU was clear that there would be no special carve outs for UK financial services that would permit the UK to benefit from some elements of the single market, such as passporting, whilst not taking part in free movement. This reflects the fact that although, in a narrow sense, equivalence involves making a technical assessment of the similarities between two regulatory systems, in practice it reflects a host of domestic and inter-state political relations (Eckert, Citation2022).

Equivalence is much more limited in terms of market access than the passporting system. Equivalence is not decided through bilateral negotiation but by each party independently deciding what access it will grant. Equivalence does not provide a full replacement for passporting. Even if it is granted, equivalence as set out by the EU does not cover the full range of financial services. Core banking services, such as lending, payments and deposit taking are excluded. Neither does equivalence grant permanent access rights. The EU can withdraw equivalence determinations with 30-days’ notice. Further equivalence decisions from the EU do not appear likely. Despite the UK being equivalent at the point of departure, the EU has stated that it requires further information in order to make equivalence decisions (European Commission, Citation2020).

Given that the UK was equivalent to the EU up until the point it left the single market, it could have technically expected the EU to make positive equivalence determinations. However, the EU has taken a restrictive approach, reflecting its concerns that the UK is seeking to obtain competitive advantage through divergence from EU regulation in the future. The EU only granted time-limited equivalence decisions for derivatives clearing (since extended and due to expire on 30 June 2025) and settling Irish securities (for an initial 6 months and now expired) (European Commission, Citation2023). Both these decisions were driven by the need to avoid short-term disruption within the EU.

In contrast, as Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced in November 2020 that the UK would adopt a more liberal approach, granting 28 equivalence decisions to the EEA in a range of areas, 21 to the USA, 15 to Singapore and 13 to Switzerland. Beyond the number of equivalence decisions granted, the UK has also made clear that its approach to equivalence differs from that of the EU, implicitly criticising the EU’s approach in the process. For example, as part of a wider emphasis on the importance of transparency and outcomes within the UK’s approach to equivalence, the Treasury has said that the withdrawal of equivalence would be considered only ‘as a last resort’ and would be accompanied by adaptation periods, rather than the 30 days’ notice period of the EU approach (HM Treasury, Citation2020).

The limited number of equivalence decisions granted by the EU means that UK financial services trade has less single-market access than other leading international financial centres such as New York and Singapore. As of January 2023, the US has 21 equivalence decisions from the EU, Singapore has 17, whereas the UK only has two. The profoundly different equivalence regimes being applied to London suggests that the EU’s approach to the UK may be motivated more by concerns to develop its own competencies in financial markets than by the merits of the UK’s domestic approach to regulation.

The UK has implemented a Temporary Permissions Regime, currently scheduled to run for three years until the end of 2023. This allows EEA firms and funds that were using a passport to access the UK market during the transition to continue to do so, provided they notified the Financial Conduct Authority that they would us the permissions regime before the end of transition. There is no equivalent EU-wide scheme for UK firms operating in the EU, although some member states, such as Ireland and Denmark, have established temporary permissions for UK firms that were passporting into particular parts of financial markets for specific periods of time from 1 January 2021 (Laven, Citation2021).

Since the end of the transition period, the UK government has emphasised the opportunity, as it sees it, to create a more competitive financial services sector by using the UK’s new-found domestic control of financial services regulation to better tailor regulation to the specific needs of the UK, rather than adopting regulation designed for all EU member states as was the case before Brexit. This is being achieved through the Financial Services Regulatory Review which will be implemented through the Financial Services and Markets Bill.Footnote1 At the time of writing, this Bill had not entered the statute book. However, it is clear that the government is seeking relatively modest regulatory change across a range of areas including capital markets and insurance alongside regulatory changes aimed at stimulating growth in green finance and fintech. Under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, there has been a greater emphasis on the prospects for economic growth through financial services. This was underscored by his Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, setting out the regulatory changes envisaged in a major speech in December 2022 (Hall, Citation2022).

None of the changes proposed seek to improve single market access for UK financial services since this is not possible under the terms of the TCA. Concerns have also been expressed within the sector that although a number of consultations and reviews have been announced, the pace at which regulatory change has been implemented is slower (Jones & Cruise, Citation2022). Others, including the Treasury Select Committee, have raised the prospect that further deregulation, particularly through encouraging regulators to consider competitiveness when making regulatory decision making, may create more risks and costs for financial services consumers (Treasury Select Committee, Citation2022).

3.3. Measuring the impact of the TCA on UK financial services

Two main measures have been used to try to specify the impact of the TCA on UK financial services as firms have responded to Brexit by moving parts of their business and/or jobs to different financial centres within the EU: first office moves and secondly employment figures. In this paper, we use employment figures because they provide a more fine-grained analysis of where changes are taking place, particularly within the UK.

A focus on job relocations is important because they reflect the nature of contemporary financial services work and activity. In particular, they reflect the centrality of deep, inter-personal networks to the operation of financial and related professional services (Cook et al., Citation2007). The importance of these inter-personal networks stems from the need to tailor financial services products to the bespoke requirements of clients (Clark & O’Connor, Citation1997). As such, much of the focus for both the UK and the EU post Brexit has been on where financial labour is located because this is the source of value creation within the sector. For example, the European Central Bank has been concerned that financial services firms were ‘brass plating’ their EU operations and has frequently signalled that UK entities will be required to ensure that sufficient staff are located in the EU to fulfil regulatory requirements made by the European Commission (Wymeersch, Citation2019).

However, whilst it is clear that such deep and dense labour networks are needed in financial centres, it is far harder to specify precisely how many people are doing which kinds of jobs and where. Furthermore, international comparisons are difficult because of the different ways in which national employment statistics are collated. Following Wójcik (Citation2021), in this paper we focus on the number of jobs rather than the value added of any given job because it is extremely difficult to accurately calculate value added in the case of financial and related business services jobs (FABS). This is because the cyclical nature of finance significantly impacts the value added attributed to jobs with that value appearing to grow significantly during asset price and credit bubbles which actually point to potential weaknesses, rather than growth, within the sector (Christophers, Citation2013).

4. Employment changes post Brexit in UK financial services

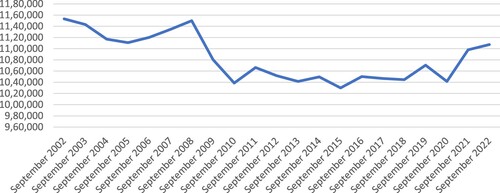

Latest official figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that in September 2022, there were 1.107 m jobs in financial services in the UK. The same figures, as shown in , point to three phases in financial services employment in the UK in the last 20 years (see also New Financial, Citation2022).

Figure 1. Jobs in UK financial services and insurance 2002–2022. Source: ONS Workforce Jobs Survey/Nomis.

First, there was a period of buoyant financial services employment, from 2002 up until the 2007–8 financial crisis. During this period the percentage of totally UK jobs made up of those in financial and related professional services averaged around 4% (). The second period can be classified as one of flat growth, from the financial crisis until the end of the most intensive phase of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2021. During this period, there was a steady decline in the percentage of jobs in financial and related professional services in the UK, dropping from 4.1% in 2008 to 3.5% in 2021.

Table 1. Employment in financial services insurance in the UK 2002–2022 (number of jobs and percentage of total jobs).

The third period is rather more speculative, given that the data is much more recent but there are signs of an increase in the number of jobs from 2021 onwards. This growth needs to be contextualised within the wider economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic in which it is hard to assess which parts of growth are due to a covid rebound and which are signals of intrinsic growth. Indeed, the percentage of total UK jobs in financial and insurance activities has remained at 3.5% during this period suggesting that the financial services sector is not outperforming growth in other parts of the economy. This analysis is corroborated by analyses that have used these figures to calculate that there would be around 52,000 more people working in financial services currently than the figures showed had the growth in jobs matched that in other areas of the economy (New Financial, Citation2022).

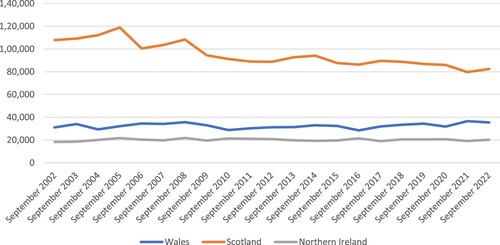

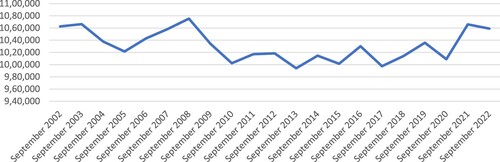

The picture becomes slightly more complex when the data is broken down across the United Kingdom over the same time period as shown in and .

Figure 2. Jobs in financial servies and insurance: Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland 2002–2022. Source: ONS Workforce Jobs Survey/Nomis.

Figure 3. Jobs in finanical services and insurance: England and Wales 2002–2022. Source: ONS Workforce Jobs Survey/Nomis.

These figures show that employment has remained largely flat in Wales and Northern Ireland. England is shown to be the main driver of the UK wide pattern described above, reflecting the dominance of London in financial services as a whole. However, employment has declined more markedly in Scotland, from 1,08,000 jobs in financial services and insurance in September 2002 to 82,421 in September 2022. This is significant because the government has made much of the potential for financial services to deliver economic growth across the UK, not only in London. For example, the Treasury’s State of the Sector report emphasises that ‘two-thirds of jobs [in financial services] are outside of London in finance hubs such as Belfast, Birmingham, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Leeds and Manchester’ (HM Treasury, Citation2022). This report is itself important because it was undertaken as part of a commitment to produce an annual report into the nature of UK financial services post Brexit.

4.1. Causes of financial services jobs figures in the UK

These figures suggest that whilst no part of the UK is seeing substantial growth in financial services employment, the trend for a reduction in total employment has been particularly marked in Scotland. In this section, we suggest that there are three main factors that explain these trends.

The first of these is Brexit. The ending of passporting and its replacement with equivalence determinations has led to the relocation of some financial services activity from the UK to financial centres within the EU. The aim of these moves is to adopt a base from which the firm can access the rest of the single market. The precise number of such office moves and the number of jobs that have relocated as a result is unknown, partly because firms view such figures as part of their organisational strategy and therefore are often reluctant to share such figures publicly. Consultancy firms have sought to use company annual reports in order to generate further information on the numbers involved. New Financial estimated in September 2021 that 440 firms in banking and finance had relocated part of their business from the UK into the EU. This included some firms who moved part of their business, including staff, and others who set up new entities within the EU, thereby creating new jobs in EU financial centres that would not necessarily have been created in the absence of Brexit (Hamre & Wright, Citation2021). They estimate that the total value of assets moved in these relocations is £900bn in banking and £100bn in assets and funds. As one of our interviewees, who worked on tracking financial services firm relocations post Brexit, summarised

Almost every firm that we’ve looked at is significantly expanding its trading operations in the EU. The most obvious case is banks, like Bank of America which has actually chosen to headquarter its EU markets business in Paris. They’ve got something like 400 people in Paris already, and that’s in a space for up to 1000. (Financial Services consultant, March 2020)

There’s a high density, of very highly qualified mathematical mathematically trained graduates pouring out of elite French universities. In Paris, you also feel slightly closer to London in terms of culture and the size and scale of the city than you would in somewhere like Frankfurt. Crucially, it's commutable [to London] in a way that Frankfurt isn't really. It is physically possible to get the first train out of London, or the train out of Paris. on a Monday morning and basically do a weekly commute, in a way that's Dublin and Frankfurt just aren’t really. It’s a nicer place to live, probably a nice place to work. Paris is where you want to base your business for a whole host of reasons. (Financial Services consultant, March 2020)

The second set of factors that explain the relatively flat employment figures in UK financial services relates to lower value financial services activity in retail banking and in the mid and back-office functions of wholesale banks. Research has identified a trend that pre-dates Brexit for declining branch numbers within retail banking, reflecting the growing use of online banking services and a desire to reduce costs on the part of banks (Leyshon et al., Citation2006). In other parts of this area of financial services there are geographically distinctive factors that are also likely to contribute to a lack of job creation in financial services. For example, our interviewees pointed to the different personal tax regimes in Scotland adding additional costs to businesses that were located in both England and Scotland, potentially making it more attractive for firms to concentrate their operations in either Scotland or the rest of the UK:

There are other factors that would potentially have an impact of in Scotland. The tax decisions of the Scottish government have made it harder for firms to have big presences up there because then they're juggling different tax rates for their employees. And obviously, if you go down the route of Scottish independence, then that's a much bigger game changer, I think. (Insurance Trade Body Manager, February 2020)

One really interesting, really interesting area to look at is Poland, rather than the frontline, financial centres. I mentioned that a lot of people in the City are thinking of Brexit, as the occasion to rethink the UK framework, rather than necessarily the cause. For example, take UBS. It now has 5000 staff in Poland, and its headcount in Poland has increased 40% since the referendum. US firms like the NY Mellon and State Street have got, I think, tens of thousands of people in Poland. Credit Suisse has got three different offices now in Poland and has moved thousands of staff. And I think what's going on here is that when firms started looking at their Brexit contingency plans, the first thing they did is look at their footprint across Europe more widely. They would be thinking, does this really makes sense for us to have 1000s of back office and middle office support staff in very expensive real estate in the middle of one of the most expensive cities in the world [London]’

I think they might be looking at that office in Glasgow with 2500 staff. Yes, it's cheaper than having them in London, but maybe it will be even cheaper to have them in Poland, or Latvia, or Lisbon. I suspect we'll see more of those relocations. So Brexit will not only have an impact on City of London at the top end. It could start to have an impact over time on the regional footprint of the banking and finance industry, which potentially has a bigger political impact than the City itself. You know if US investment banks are closing down offices in Glasgow, Belfast, Manchester, Leeds and relocating them to Poland, that is going to cause more of a stink politically big US investment bank moving 100–200 staff from the UK to the EU. Even though the economic impact is probably lower, at a local level, the economic impact is very negative, it is keenly felt. (Financial Services Consultant, March 2020)

The final reason for the flatlining of employment in financial services lies in the ways in which jobs are classified in official statistics as financial services jobs or not (on which see Wójcik (Citation2021)). The issues here are twofold. First, it is hard to easily define which jobs should fall within financial services and which fall within wider business and professional services and whether the latter should be included in the numbers of financial services employees. Second, the nature of financial services work itself is changing. This means that some roles which would be seen as financial services work may increasingly be categorised elsewhere. This is particularly true at the interface between financial services and computer services given the rise in fintech and tech companies entering financial services more generally (Lai & Samers, Citation2021). This issue has become particularly acute as financial services work itself has changed with the rise of fintech. This means that some work undertaken in fintech development which could be viewed as part of financial services is likely to be classified in financial services. This factor is likely to be particularly important when considering the figures in Scotland because Edinburgh in particular has developed into an important fintech centre (Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee, Citation2020).

5. Conclusions

To date, much of the research into the impacts of Brexit on financial services has focused on the implications for particular cities by focusing on the highest value, front office wholesale financial services jobs in London and other leading international financial centres. For example, research has examined the politics and political discourses that shaped the approach taken to Brexit by the City of London (James et al., Citation2022; Kalaitzake, Citation2021). Research has also examined the regulatory impacts of Brexit in relation to central banking and the political economy of regulation more generally (Talini, Citation2020) and adopted an historical perspective to understand the response of the City of London to Brexit (Schenk, Citation2019).

Our research extends these analyses by focusing on the impacts of Brexit on financial services employment in leading financial centres such as London but also in regional cities in the UK. In so doing, we begin to examine how Brexit is impacting financial services not only in wholesale finance but also in retail and mid and back-office functions.

Our analysis demonstrates that taking the UK as a whole, jobs growth in financial services is best characterised as relatively stagnant post Brexit. This builds on a trend that began following the 2007–8 financial crisis. Before, that point, jobs growth had been more buoyant. At one level this could be interpreted as a relatively positive outcome from Brexit given that worst case estimates of the number of jobs that would leave the UK in financial and related professional services have not come to pass. However, such an interpretation would overlook important insights jobs data can provide into the uneven geographical and sectoral implications of Brexit on employment in financial services in the UK. It also overlooks the ways in which post Brexit changes are playing out on a dynamic sector that is itself changing in common with financial services globally and in ways that are not driven by Brexit itself.

In terms of geography, our research draws attention to the greater proportional impact of job relocations in Scotland compared with the rest of the UK. Meanwhile in terms of the differential impact on different parts of financial services, our research points to the importance of including retail banking and mid and back-office activities in considerations of post-Brexit financial services employment. Both of these are, albeit for different reasons, also contributing to declining employment in financial services in the UK. In retail banking, this reflects wider branch bank closure programmes as banks seek to reduce costs. The same cost cutting rationale plays out differently in mid and back-office functions as banks in particular look to Eastern and Southern Europe to relocate these activities where labour is cheaper than in regional cities across the UK. Whilst Brexit is not directly the cause of these locations, Brexit may be the opportunity in that it encouraged banks to review their European locations more generally. Finally, the changing nature of finance itself, particularly fintech, may account for some of the employment stagnation as some jobs in fintech may be classified in technology or consulting (Wójcik, Citation2021). Further international comparative research would help assess whether this trend is pan European or a distinctive Brexit feature.

To what extent, then, have financial and relative professional services jobs gone ‘missing’ in the UK? At one level, it is clear that financial services employment growth has been at best muted in the UK and this contrasts with buoyant jobs increases in other parts of the EU post Brexit. However, it would be an error to attribute all of these so-called missing jobs to Brexit. Brexit has led to wider strategic audits by financial services firms of their European operations. Cost cutting objectives have been met partly by beginning to relocate some activity out of the UK to Eastern and Southern Europe whilst other activities, notably in person retail banking, has been cut altogether. Despite it being three years since the end of the transition period, it is clear that we will need more long-term data sets to fully assess the lasting impacts of Brexit on financial services employment. Moreover, we suggest that far from being done, Brexit is being played out within a sector that is itself in a period of profound flux and hence it is likely to be some time before the full impacts of Brexit of UK financial services, and their consequences for wider economic growth, are fully understood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah Hall

Sarah Hall is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Nottingham and Deputy Director at UK in a Changing Europe.

Martin Heneghan

Martin Heneghan is an Assistant Professor in Public and Social Policy at the University of Nottingham.

Notes

References

- Cassis, Y., & Wojcik, D. (2018). International financial centres after the global financial crisis and Brexit. Oxford University Press.

- Christophers, B. (2013). Banking across boundaries: Placing finance in capitalism.

- Clark, G. L. (1998). Stylized facts and close dialogue: Methodology in economic geography on JSTOR. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 88(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00085

- Clark, G. L., & O’Connor, K. (1997). The informational content of financial products and the spatial structure of the global finance industry. In K. Cox (Ed.), Space of globalization (pp. 89–114). Guildford Press.

- Cook, G. A. S., Pandit, N. R., Beaverstock, J. V., Taylor, P. J., & Pain, K. (2007). The role of location in knowledge creation and diffusion: Evidence of centripetal and centrifugal forces in the city of London financial services agglomeration. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(6), 1325–1345. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37380

- Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee. (2020). Negotiation of the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom Government. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.parliament.scot/api/sitecore/CustomMedia/OfficialReport?meetingId = 12692

- Eckert, S. (2022). Sectoral governance under the EU’s bilateral agreements and the limits of joint institutional frameworks: Insights from EU-Swiss bilateralism for post-Brexit relations with the UK. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 60(4), 1190–1210. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13315

- European Commission. (2020). Questions and answers: EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_2532

- European Commission. (2023). Equivalence of non-EU financial frameworks. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://finance.ec.europa.eu/eu-and-world/equivalence-non-eu-financial-frameworks_en

- GBSLEP. (2016). Greater Birmingham and Solihull local economic partnership strategic economic plan (2016-2018). https://gbslep.co.uk/strategy/strategic-economic-plan/

- Hall, S. (2022). The ‘Edinburgh Reforms’ show a renewed interest in financial services as a source of growth’ UK in a Changing Europe. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-edinburgh-reforms/

- Hall, S., & Heneghan, M. (2023). Interlocking corporate and policy networks in financial services: Paris-London relations post Brexit. Advances in Economic Geography (ZFW). In press.

- Hamre, E. F., & Wright, W. (2021). Brexit and the city: The impact so far. New financial.

- HM Treasury. (2020). Guidance document for the UK’s equivalence framework for financial services. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-document-for-the-uks-equivalence-framework-for-financial-services

- HM Treasury. (2021). Technical negotiations concluded on UK-EU memorandum of understanding. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/technical-negotiations-concluded-on-uk-eu-memorandum-of-understanding

- HM Treasury. (2022). State of the sector: Annual review of UK financial Services 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.theglobalcity.uk/PositiveWebsite/media/Research-reports/State-of-the-sector_annual-review-of-UK-financial-services-2022.pdf

- House of Commons Library. (2022). Financial services: Contribution to the UK economy. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06193/

- James, S., Kassim, H., & Warren, T. (2022). From Big Bang to Brexit: The city of London and the discursive power of finance. Political Studies , 70(3), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720985714

- Jones, H., & Cruise, S. (2022). Analysis: ‘Big Bang 2.0’ up in smoke as Britain’s finance law reforms underwhelm industry’ Reuters 20 July 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/big-bang-20-up-smoke-britains-finance-law-reforms-underwhelm-industry-2022-07-20/

- Kalaitzake, M. (2021). Brexit for finance? Structural interdependence as a source of financial political power within UK-EU withdrawal negotiations. Review of International Political Economy, 28(3), 479–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1734856

- Kynaston, D. (2002). The city of London volume 4: A club no more 1945-2000. Pimlico.

- Kynaston, D. (2012). City of London: The history. Vantage Books.

- Lai, K. P. Y., & Samers, M. (2021). Towards an economic geography of FinTech. Progress in Human Geography, 45(4), 720–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520938461

- Laven. (2021). Post-Brexit: Access regimes in key EEA member states, 1 July 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://www.lavenpartners.com/thought-leadership/brexit-temporary-permission-regimes/

- Leyshon, A., Signoretta, P., & French, S. (2006). The changing geography of British bank and building society branch networks, 1995-2003. Submission to Treasury Committee on Financial Inclusion, 35, 1, pp. 113–140.

- New Financial. (2022). The mystery of the missing banking and financial jobs in the UK. New Financial, London. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://newfinancial.org/the-mystery-of-the-missing-jobs-in-uk-banking-and-finance/

- Oliver Wyman. (2016). The impact of the UK’s exit, p. 24.

- ONS. (2023). Quarterly national accounts, Feburary 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/datasets/ukgdpolowlevelaggregates

- Pooley Rutter, C. (2022, November 17). The curious case of Britain’s ‘missing’ banking jobs. The Financial Times. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/986aa6b3-51c7-4124-8780-ddbc7e756f10

- Schenk, C. (2019). The city and financial services: Historical perspectives on the Brexit debate. The Political Quarterly, 90(S2), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12624

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Talini, L. (2020). Brexit and the future of the City of London: Between deregulation and innovation. In The politics and economics of Brexit (pp. 162–180). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Treasury Select Committee. (2022). Future of financial services regulation. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmtreasy/141/report.html

- UKICE 2021. (2021). The impact of Brexit on UK Services. UK in a Changing Europe. Retrieved January 31, 2023, from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/The-impact-of-Brexit-on-UK-services.pdf

- Wójcik, D. (2021). Financial and business services: A guide for the perplexed. In J. Knox Hayes, & D. Wójcik (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of financial geography (pp. 25–55). Routledge.

- Wright, W., Benson, C., & Friis Hamre, E. (2019). New financial Brexitometer.

- Wymeersch, E. (2019). Brexit and the provision of financial services into the EU and into the UK Ghent University Library. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/199400937.pdf