ABSTRACT

Territorial cooperation has a long history in the UK. Numerous stakeholders in the UK have a long-standing and active engagement in the EU’s Territorial Cooperation Programmes (also known as ETC and Interreg). Launched in 1990, Interreg is the EU’s framework for territorial cooperation, enabling joint actions and policy exchanges between national, regional and local actors from different Member States. Brexit led to the decision on the part of the UK Government not to participate in EU territorial cooperation programmes after 2021, except for the PEACE Plus programme covering Northern Ireland. This article examines what will be lost because of this decision, especially in terms of what, where and what types of organisations are impacted, and what will be ‘missed’ in terms of the added value associated with territorial cooperation. At a time when cooperation is seen as a key lever to support efforts in addressing major economic, political, social and environmental challenges, and border relations, the article examines what, if anything, is being/can be done to fill the gaps? The article is based on documentary analysis, programme data and engagement with policy, programme and project stakeholders.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Cooperation is highly prized. As the UN’s sustainable development goals state the ‘world is more interconnected than ever, progress has to involve partnership, cooperation and a collaboration’ (UN, Citation2016). The value of international cooperation and partnership is clearly a primary focus. However, the value of territorial approaches to development is also highlighted, for example, by the OECD (OECD, Citation2020) and EU. Thus, territorial cooperation at the regional and local level also has an important role to play. Territorial cooperation with neighbouring territories of the UK has a long history. Internationally, territorial cooperation arrangements come in numerous forms and are widely pursued as a means for territories to work together to address shared development opportunities and challenges. The most familiar forms of territorial cooperation in the UK are the EU’s Interreg Territorial Cooperation Programmes. Interreg is the EU’s framework for territorial cooperation that aims to enable joint actions and policy exchanges between national, regional and local actors from different Member States. Interreg has a long, 30+ year history and has become a well-established, well-respected component of the policy landscapes in the UK and across the territories elsewhere in Europe.

Post-Brexit, the UK government’s decision to withdraw from all but one European Territorial Cooperation ProgrammeFootnote1 represents a major shift in approach. In addition, the implications of COVID-19, and shifting domestic policy and international politics, mean there are wider ‘unknowns’ around future territorial cooperation linked to funding, policy priorities and political barriers. Despite these challenges, there are opportunities to pursue. Many other non-EU countries participate in Interreg programmes, noting the opportunities to pursue synergies with national policy objectives and to link with related territories in neighbouring counties (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2017). These conditions raise the questions will Interreg be missed by UK partners? For the UK, how will its loss differ in terms of geography, sectors/themes and organisations? Is there/will there be any opportunity for participation in territorial cooperation in the near future?

This article draws on research on the role and added value of territorial cooperation for participating regions carried out over a number of years of the UK’s involvement in InterregFootnote2 and linked to a number of policy and programme evaluation projects. The report utilises desk-based research, drawing on both policy and academic sources and interviews with project and policy stakeholders. The work includes:

Insights based on the experience of territorial cooperation;

Options and models for territorial cooperation; and

Recommendations for future territorial cooperation.

2. Approach and methods

Assessing the added value of territorial cooperation, in particular Interreg, is extremely challenging due to the comparatively small amounts of funding,Footnote3 large geographic areas covered, lack of comparable data and work which often involves ‘experimental’ and ‘soft’ areas of cooperation (Mirwaldt & McMaster, Citation2008). Nevertheless, the impact and added value of Interreg are the subject of formal evaluation reports and wider debate. Analyses reveal achievements in terms of the quantitative effects of EU funding in leveraging additional resources for economic development through ‘financial pooling’ acting as a catalyst for regeneration and encouraging partners to undertake sub-regional projects that might otherwise not take place (Martin & Tyler, Citation2006).

More widely acknowledged, but no less challenging to measure, is the qualitative added value of Interreg. Qualitative analysis and wider definitions of policy-added value have been widely applied to EU Cohesion Policy (Mairate, Citation2006), and Interreg in particular. The opportunities for the exchange of experience and learning and the adoption of innovative elements, processes or responses to domestic policy are commonly mentioned (Ferry & Gross, Citation2005). In line with Interreg’s scope to work across borders and with variable geographies, it is valued for enabling new approaches, new partnerships (Lähteenmäki-Smith & Dubois, Citation2006) and collaboration across new geographies (Böhme et al., Citation2003a; Colomb, Citation2007; Dühr et al., Citation2007; Farthing & Carrière, Citation2007). This work provides valuable insights into the areas/types of added value, in particular ‘soft’ added value. However, analyses tend to focus on value for the EU, region, programme areas or project partners and a single programme period. A major missing link, which became all too obvious during the Brexit negotiations, is a national understanding of the role of Interreg and views over successive programme periods.

As well as considering experience, this article seeks to look forward at conditions ‘post-Brexit’. To do so, the wider context for territorial cooperation is examined. Territorial cooperation is a much broader concept and process than Interreg programmes alone. Policy and academic literature explore the variety of territorial cooperation in the forms of cross-border (between adjacent regions), transnational (involving regional and local authorities) and interregional (large-scale information exchange and sharing of experience) cooperation (Perkmann, Citation2003; Scott, Citation2002). The rationales, forms and foci of territorial cooperation programmes differ considerably, linked to different development paths, contexts and needs (Faludi, Citation2007a, Citation2007b). Key variables when differentiating between forms of territorial cooperation structures are as follows:

The degree of administrative centralisation or decentralisation;

The levels of formality/institutionalisation involved;

The level of ‘openness’ and intensity of partner involvement;

The extent to which joint or parallel structures are in place to support cooperation; and

The extent to which the institutions involved take an active role in driving cooperation (McMaster et al., Citation2013).

Documentary and policy research: final programme reports; annual reports; European Commission evaluations and studies; programme publications; academic research.

Project review: Review of the UK Interreg A and B project descriptions in the INTERACT keep.eu database. 2110 projects, involving 4259 partners, are recorded in the KEEP database as involving UK partners.Footnote4 Developed by the EU’s INTERACT programme, the database is a source of aggregated information regarding the projects and beneficiaries. It offers a source of the cross programme and longitudinal data on geographic, partner type and thematic participation in Interreg.Footnote5

Interviews: A number of interviews were undertaken with experienced stakeholders, who offered perspectives on their involvement over successive programme periods. The interviews, 20+, involved national, programme and regional representatives over an extended period of 2018–2021. The results were collated and compared to identify common, shared themes, particularly in relation to perceptions of added value.

3. UK and European territorial cooperation

UK territories have been involved in Interreg for over 30 years, since its inception. Interreg’s aim is to jointly tackle common challenges and find shared solutions in fields such as health, environment, research, education, transport and sustainable energy. Projects are co-funded by seven-year programmes, to which participating countries commit funding. For example, for the 2014–2020 period, the UK committed to five cross-border cooperation programmes, six transnational programmes and four interregional programmes with a total budget of up to €10.1 billion (CEC, Citation2023). Interreg is a highly structured, institutionalised, closely managed/regulated programme-based cooperation. The programmes are developed based on a partnership approach with strong regional/local involvement in the development and delivery. With an overall aim of supporting territorial cooperation between participating regions, the programmes also have their own specific objectives and priorities, and distinctive elements, for example, the remote and peripheral communities in the Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme, connectivity in the North Sea Region programme and shared education, shared spaces and services in the PEACE programme.

The Withdrawal Agreement concluded between the EU and the UK establishes the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, in accordance with Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union (CEC, Citation2020a). Under the Withdrawal Agreement, UK partners can now only participate in projects and programmes until the closure of the 2014–2020 programmes. The only exception to the UK withdrawal from Interreg Programmes is the 2021–2027 PEACE Plus programme, which includes Northern Ireland. The decision not to pursue new participation in Interreg post 2020 has been opposed by, in particular, the devolved governments in the UK. Scottish Government and Scottish local authorities have been vocal in their ongoing commitment to territorial cooperation with neighbouring territories. In 2017, the Scottish Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe and External Affairs Mike Russell stated that ‘it remains important for Scotland to maintain presence and participation in the current EU cooperation programmes both now and after exit from the EU’ (Quoted in McMaster et al., Citation2017). More recently, in November 2022, the Scottish Government Employment Minister Richard Lochhead wrote to the UK Levelling Up Secretary stating that Scottish ministers believe that the UK Government should commit financially to participate in programmes for the 2021–2027 period. He highlighted the innovative projects which have benefited from £72.5 million of European Territorial Cooperation grants, the strong and valued role of Scottish partners; and concern there was ‘no funding, nor desire, to develop and continue the fruitful cooperation initiatives’ referred to in plans for shared prosperity funding (Scottish Government, Citation2022). Similarly, Scottish local councils state that without additional funding from the EU or national level there is no ‘financial room’ to maintain or foster external relations, but there is still an appetite for better awareness and opportunities for cooperation (Bergstra et al., Citation2021).

The Welsh Government was early to set out its ongoing commitment to territorial cooperation in the future. The Welsh Government (Citation2017) stated that it has attracted around £7.3 m per year from European Territorial Cooperation programmes, and went on to say that cross-border cooperation with Ireland could become even more important post-2020. The Ireland-Wales Shared Statement (Citation2021) highlights the wish for the ‘closest and deepest possible relationship between the UK and Ireland, and between Wales and Ireland’. As mentioned, Northern Ireland remains involved in the PEACE Plus Interreg programme, but loses wider links to the EU’s high north (e.g. previously possible through the Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme), to Scotland (e.g. previously possible through Northern Ireland – Ireland - Scotland cross-border cooperation Programme) and to wider Europe (e.g. previously possible through the North West Europe Programme). In England, as will be discussed, regional participation in Interreg has been more mixed. However, authorities in Cornwall and Kent have noted the loss of the resource and the impact on links to neighbouring territories. In March 2021, Cornwall County Council acted to set up a Memorandum of Understanding with Brittany Council, positioning itself as an ‘outward looking region’ (Cornwall County Council, Citation2021). Kent County Council highlighted the importance of ongoing partner cooperation across borders and the value of funds secured through Interreg in their response to the UK Government Communities and Local Government Select Committee Inquiry on Brexit and Local Government (Kent County Council, Citation2017). Subsequently, Kent County Council, along with Essex, has gone on to pursue cooperation through the Straits Committee (Citation2023), which links territories bordering the Dover Strait area and the Channel-North Sea region.

More generally, UK partners have a reputation as well-respected partners in cooperation programmes. They are widely recognised as leaders in their field, manage the administrative elements of the programmes well, and due to internal requirements to secure co-financing are noted as being experienced and focussed on delivering outputs and results (McMaster, Citation2017a). Despite the opposition, the UK government’s position on Interreg remains unchanged and responses note, instead, the power given to local governments to focus funding on locally-identified projects (Press and Journal, Citation2022). The decision by the UK Government appears to end opportunities for European territorial cooperation through Interreg for partners in most of the UK. It raises the questions, how does the loss differ in terms of geography, sectors/themes and organisations, and is there/will there be any opportunity for territorial cooperation in the near future?

In terms of involvement in Interreg, experiences vary across the UK. The programmes have different territorial coverage and financial scales. The largest in terms of funding was the Interreg B North West Europe Programme which includes highly populated territories. The smallest is the Interreg B Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme. illustrates the range of areas covered as well as the scale of the programmes.

Table 1. Interreg Programmes 2014–2020.

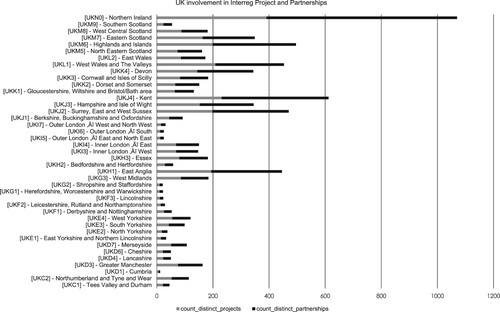

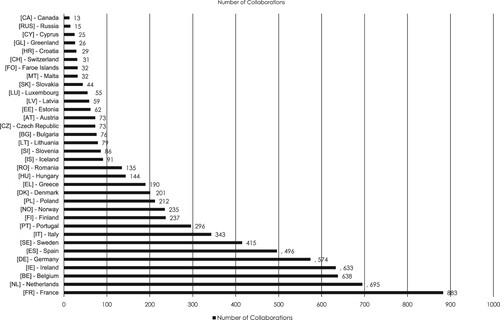

shows a regional distribution of participation. Northern Ireland, which has a direct land border with Ireland, and is eligible for multiple Interreg programmes, has a high proportion of projects, particularly given its comparatively small population size. Similarly, Wales and Scotland have high levels of involvement. The highest numbers of projects are in Northern Ireland and South East England, large areas of which are covered by two cross-border programmes and the Interreg North West Europe and North Sea Region Programmes. The Highlands and Islands in Scotland are also notable for their high levels of engagement, especially given their comparatively small population. The lower levels of participation in, for example, Cumbria and Yorkshire partly reflect the geography of the programmes, the perceived relevance of ‘border’ issues and access to alternative sources of funding. illustrates the countries that stakeholders are most commonly working with. It is notable that France, Ireland, Germany and the Nordic countries are key partners.

Figure 1. Regional breakdown of UK participation (numbers of projects and partnerships by region/nation). Source: author calculations from the KEEP.eu database https://keep.eu/statistics/.

Figure 2. Cooperating regions. Source: author calculations from the KEEP.eu database https://keep.eu/statistics/.

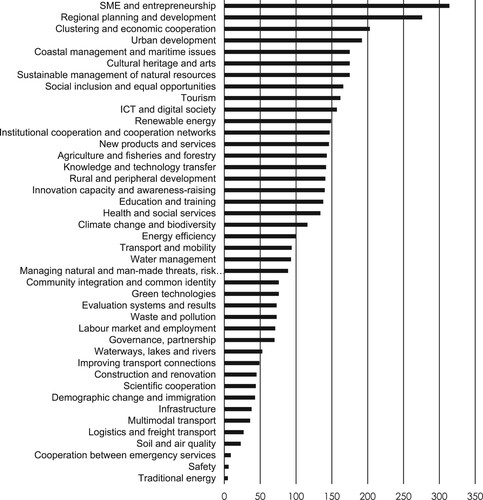

The Interreg programmes share broad development goals, informed by both EU and national development priorities, most notably: innovation and competitiveness, resource efficiency and renewable energy, adaptation to climate change and protecting the natural and cultural heritage. Interreg projects with UK partners funded since 2000 cover themes ranging from forestry to social inclusion, see . The highest numbers of projects fall under three broad headings: SME and entrepreneurship; planning, clustering and economic cooperation; cultural heritage and sustainable management of natural resources.

Figure 3. Thematic categorisation of UK projects. Source: author calculations from the KEEP.eu database https://keep.eu/statistics/.

Looking beyond the broad themes, the projects have entailed various activities, such as capital investments which have led to, for example, building and area redevelopment (locations within urban areas and villages, public and recreational spaces, public buildings, visitor destinations); and transport infrastructure provision (community roads, port and marina infrastructure, and small-scale public transport infrastructure). However, rather than physical outputs, the main focus of the projects tends to be focused on intangible solutions-based work focusing on innovation, and capacity/services, which target, for example, developing new and improved services.

A wide range of project partners are involved in Interreg. Strongly represented are local government; government agencies and authorities; universities and FE colleges; and NGOs. For some institutions, Interreg has been a small ‘side line’ to their main role. However, for others it forms a quite significant strand of funding. For example, Kent County Council was eligible under four Interreg A and B programmes, see , and in the past has secured a number of projects and associated resources.

Table 2. EU funding for Kent 2007–2013 (£1 = €0.85 exchange rate – figures are approximate as rates vary).

breaks down the sectors further and provides an average of the sizes of projects for Scotland. In this case the high level of University participation and a high level of private-sector engagement are notable. This runs counter to the general trend of lower levels of private sector engagement in Interreg.

Table 3. Scotland Interreg award by sectors 2014–2020.

Looking across these figures and tables, the high levels of engagement by territories ‘lagging’ in relation to overall UK development levels, for example, the Highlands and Islands, Northern Ireland and W. Wales, are important in the context of wider regional development debates. Links to ‘near neighbours’, France, Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands are clearly strong through Interreg. However, also of note is the intensity of links with Nordic and Scandinavian partners, including non-EU Member States Norway and Iceland. The topics of cooperation highlight both the range of themes covered and also the high concentrations of activity in key ‘territorially-based’ activities such as clustering, coastal and maritime development, urban development and sustainable management of environmental resources, suggesting a ‘distinct role’ for Interreg in these areas.

3.1 Mind the gap – added value of Interreg?

As has been noted, assessing added value is challenging (Mairate, Citation2006), especially for such a large, long-running and complex initiative. Account needs to be taken of context, scale, capacity and perceptions may differ and vary over time (Bachtler & Taylor, Citation2003). Added value also comprises different elements (Böhme et al., Citation2003b; Colomb, Citation2007). Taking this into account, this research draws on experience over a number of programme periods and insights from stakeholders with direct experience of Interreg.

At the outset, it is important to note that various operational criticisms are levelled at Interreg, and territorial cooperation more generally. Assessments note challenges such as the time it takes to build up relationships, technical/administrative issues and how to best deliver, capitalise and carry forward results (CEC, Citation2016; Panteia, Citation2010). Post-Brexit, important questions are raised about the value of pursuing regional cooperation with EU territories and ‘EU-focused projects’. These questions are all the more relevant against the background of the cost of living crisis, pressures on domestic public services and major public sector budget cuts.

Despite efforts at simplification, the Interreg programme remains complex due to, for example, the time taken to develop projects, time and cost involved in maintaining large partnerships, administrative complexities and delays, heavy reporting requirements and bureaucracy around verification of claims and procurement requirements. Issues around administrative complexity have sometimes ‘scared away’ participants, in particular private sector partners. In some instances, difficulties are heightened by weaknesses in the support and guidance offered to partners. Lack of identifiable results is another major concern, with many project outputs criticised for being temporary, limited to joint reports/strategies or lacking transferability (FORUM GmbH, Citation2009). Taken together the high amount of effort, administrative effort and limited returns suggest an overall high transaction cost involved in Interreg, which runs counter to its overall aim of reducing such barriers.

Nevertheless, not only is there pressure to continue participation in territorial cooperation from within the UK, territorial cooperation remains widely pursued internationally as a means for areas with shared and common interests to address joint challenges and opportunities (Blatter, Citation2001; MacLeod, Citation2001; Mederios, Citation2018; Ohmae, Citation1993; Perkmann, Citation2007; van Houtum, Citation2000). The following are areas where partners identify ‘distinct’ added value.

Territorial cooperation is identified as offering a thematic and/or territorial focus on specific areas. Analysis of UK participation in Interreg programmes found particular clusters of activity in relation to the following sectors: energy; low carbon/green technology; transport and connectivity; construction; blue growth and marine economy; health and life sciences; agri-food; environmental protection and creative industries and culture (McMaster, Citation2017b). Crucially, cooperation programmes and projects offered the chance to work within territorially-relevant and ‘relatable’ areas of activity alongside territories with the same, similar, or related place-based opportunities and challenges. For example, the Northern Periphery and Arctic programme has been particularly relevant for the Highlands and Islands given the programme’s focus on the needs of remote and sparsely-populated areas. The North Sea Programme, in turn, has been valuable by linking territories along the North Sea coast, and funding a number of innovative projects in fields such as maritime transport and aspects off-shore renewables. Overall, the programmes have enabled collaboration in, for example, niche/emerging territorially important sectors, which are not necessarily prioritised by national policy, for example, a specific types of aquaculture (Laganà, Citation2020; McMaster & Vironen, Citation2017).

Through cooperation, partners have built critical mass to develop, test and pilot specialised and tailored actions and activities in ways that would not have been possible working in isolation (Hörnström et al., Citation2012; McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019) for example, with cooperation helping to fill specific knowledge gaps and enable access to external expertise on territorially relevant themes. For example, Interreg programmes were early to support work on remote health care provision in extremely isolated communities. Cooperation between coastal, island and peripheral regions connects areas and interests which can be marginalised or overlooked by domestic policies, for example, the value of cruise tourism to island communities. In addition, as has been noted, the partner types involved in Interreg programmes are diverse. Working through triple and quadruple helix partnerships, involving public authorities, industry, academia and citizens, is a common characteristic of Interreg projects. Thus, territories can extend their networks and connections, for example, to include centres of research excellence, public authorities leading development in service provision and building connections to act jointly.

The recognition that partners ‘have a lot to offer’ has been important in building confidence and giving a profile to stakeholders. International recognition was an unexpected, but valuable, result noted by Scottish partners involved in the European Territorial Cooperation programmes (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019). They not only gained from the shared experience, but the process of sharing their experience with others and the opportunity to become a ‘leader’ in the project was also beneficial. For example, in the CityLogo (URBACT), the recognition of Dundee’s leading role in the use of city branding and strategic communication as an economic development tool means the City now has a solid evidence base and confidence upon which to progress and justify further efforts (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019). At a more strategic level, for regional and devolved governments, participation in programme monitoring committees is a channel for regular meetings with international counterparts and multi-level partnerships. For example, representatives of the Scottish Government would sit alongside representatives of the UK government on the North Sea Region Programme Monitoring Committee. Along with the Scottish Government, regional representatives attended Monitoring Committees for the Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme, and sit alongside government and European Commission officials from the participating countries.

Innovation in the form of new ideas, approaches and processes is central to territorial cooperation initiatives. Territorial cooperation programmes have been ‘early adopters’ of work in areas such as the circular economy, and remote public service provision prior to their prioritisation in mainstream programmes. For example, allowing a local authority to ‘take a risk’ or draw in best practices in a way that would not be possible acting alone. In particular, territorial cooperation initiatives have a key role in facilitating the flow and exchange of information, which underpins innovation. Innovation networks and connections not only enable knowledge sharing but also function to build up common social capital and trust. Many programmes are increasingly in a position to develop, apply and exploit that information, for example, pre-commercial research working in association with potential end-users, product and process innovation with marketable products and improved approaches (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019). For example, partners involved in a project supporting entrepreneurial firms working in digital and green economies funded by the North West Europe Programme noted the valuable chance to ‘explore validating their innovation in one or more partner regions in Europe, thanks to the support from the Interreg IV-B North West Europe programme’ (National Centre for Universities and Business, Citation2015). The small scale of the projects and the collaborative approach means there is an opportunity to ‘give things a go’, test, trial and pilot. If it works well that is a useful outcome, if not the organisation is better informed and can come up with alternative solutions. For example, practitioners working in the ‘mPower project’, funded by the Interreg VB Ireland – Scotland – Northern Ireland cross-border programme, highlighted the value of cooperation for working more effectively, working better by linking up strengths, for example, in work on patient well-being and health management, and for recognising locational nuances and appreciating differences (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019)

Learning and exchange of ideas are vital to building social capital and working more effectively, working better by linking up strengths and recognising locational nuances and appreciating differences. Partners invest effort into developing innovative thinking and ideas, taking a valuable opportunity to gain a wider perspective, For example, a study of the Ireland-Wales programme notes

despite the relatively small size of the Interreg Ireland-Wales programme, the evolution of Ireland-Wales cross-border cooperation under its aegis has proved essential to the empowerment of policy networks in Ireland and Wales. This is one of the programme’s most important achievements. Cross-border networks in Ireland and Wales have gained independence from the actions that have formed them, they have enforced and introduced boundaries to strengthen their position in new cross-border processes in areas of interests such as scientific research, culture and tourism (Laganà & Wincott, Citation2020).

This is especially important at a time when budgetary pressures can force a narrowing of perspectives and focus solely on core tasks. Cooperative actions are also valued as catalysts to stimulate new ideas for funding and action, either accessing a new market or driving innovation, for example, in emerging sectors such as the circular economy. For example, in cooperation programmes the scale of the projects and the opportunity to work in partnership are appealing to ‘kick start’ organisations wanting to engage but lacking the experience or scale to move straight into a larger application to one of the bigger funds. As well as the formal links, the informal exchanges and interpersonal links are invaluable for building enthusiasm and ‘excitement’ in participants which they can bring back to their own organisations. The importance of recognising and capitalising on these ‘soft’ outcomes, retaining links and know-how and extending/embedding them in participating organisations is something that Interreg partners note as valuable (McMaster & Vironen, Citation2019).

The networks of stakeholders that have developed through successful territorial cooperation programmes have strategic know-how, local knowledge, thematic expertise and a combined capacity to innovate and take informed, forward-looking perspectives on future development. Particular successes are noted in relation to growth and economic development, business relationship, SMEs, entrepreneurial skills (particularly for youth), research and innovation, the labour market, university engagement, vocational training, environment, transport, tourism, culture and media, and ‘new governance’ (e-government) (Guillermo-Ramirez, Citation2018). More recently, COVID responses and understanding territorial impacts have been the subject of successful cooperation (NPA, Citation2020). COVID restrictions and responses demanded significant shifts, change and innovation in a wide range of economic, social and environmental practices. Exchanges of ideas and approaches and dialogue on new thinking are central to managing events in the short term and for future development. Similarly, responses to global challenges such as climate change and exchange on best managing the potential of the specific area need and potential all benefit from collaborative efforts.

4. Finding opportunities: taking forward added value

What is clear from the preceding assessment is that Interreg cooperation does bring something ‘extra’. Without it, various territories in the UK will have to face the loss of valuable cooperation links and work built over a long period of time, such as in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Programmes and projects have been active in many areas of work relevant to the contemporary challenges facing UK territories today and in the future. The loss of momentum caused by the uncertainty since the Brexit vote in 2016 and withdrawal during 2021–2027 Interreg programmes are substantial, for example, with local and regionally-based EU policy officers and programme contact points moving to other roles. This represents a loss of capacity as well as a financial resource. Furthermore, COVID and associated closed borders and reduced travel, economic and political crises, and pressure on public spending and services have posed major challenges and barriers.

Looking to the future, it is technically possible for the UK territories to be involved in Interreg programmes. The new European Territorial Cooperation (ETC) Regulations proposed by the European Commission’s DG Regio make provision for UK participation as a ‘third country’ (CEC, Citation2020b). In EU regulations the third country refers to any country outside the EU. ‘Third country’ participation is a routine part of Interreg and other European Territorial Cooperation programmes. The Interreg regulation states

It is necessary to continue supporting or, as appropriate, to establish cooperation in all its dimensions with the Union’s neighbouring third countries, as such cooperation is an important regional development policy tool and should benefit the regions of the Member States which border third countries (CEC, Citation2020b ).

Numerous EU neighbour countries, ranging from Iceland to Tunisia, have negotiated ‘third country’ participation in Interreg programmes. Alongside a financial commitment to the programmes, they participate in setting programme objectives, programme management and implementation and project partnerships. Currently, as a reserved matter, agreement to participate as a ‘third country’ would have to be secured by the UK Government. Nevertheless, the ETC regulations also make provision for geographic flexibility, which may allow for partner participation on a self-funded, case-by-case basis. However, at present, Northern Ireland remains the only UK territory to be involved in a 2021–2027 Interreg programme. The involvement of Scottish, Welsh or English territories would require self-funding, and a formal commitment to specific programmes which currently would also require some form of agreement from the UK government.

Despite this option being available, substantial progress towards re-engagement with the Interreg programmes is so far limited. Therefore, it is useful to take a broader perspective on the numerous forms of territorial cooperation with more open flexible frameworks, which could be/are open to UK territories, or could inspire future efforts, albeit with fewer financial resources, as illustrates.

Table 4. Forms of cooperation.

As illustrates, territorial cooperation can range from sporadic consultation involving limited resources to wide-ranging and well-resourced programmes with accompanying institutional frameworks. Each arrangement has pros and cons. However, the very fact that territorial cooperation has developed in such a range of ways and in different contexts demonstrates:

Cooperation is widely valued and sought after by stakeholders across sectors and levels of government;

There are a range of ‘entry points’ for territorial cooperation, associations, formal programmes and mixed approaches;

Cooperation efforts change and evolve, participants come and go, arrangements can get more/less formal/lead to spin off initiatives; and

Cooperation initiatives ‘co-exist’ and work in complementary ways to the benefit of all partners (McMaster et al., Citation2021).

Another example concerns building on the long history of links and cooperation with the Arctic regions and countries. Scotland’s northern location, as well as cultural, social and economic links with the northernmost parts of Europe in particular was formalised through the Arctic Connections – Scotland’s Arctic Policy Framework in 2019 (Scottish Government, Citation2019). The Scottish-Arctic cooperation aims for a two-way discussion with the aim of paving the way for new collaborations and opportunities on shared challenges such as climate change, but also presenting Scotland, in the post-Brexit environment, as ‘an open and outward looking nation’. Naturally, this provides an opportunity to build on the already strong links with the man of the territories of the Interreg Northern Periphery and the Arctic Programme but offers opportunities also beyond the EU (most notably with Canada and northern parts of the USA).

At this stage, efforts are modest in terms of financial resources, but do have a weight of support behind them. Crucially, they retain a level of contact between key stakeholders, which links to the retention of key areas of the added value that come from territorial cooperation: the contacts and networks. However, these illustrate examples of how engagement, recognising and pooling other forms of territorial engagement, working pragmatically can lead to an evolving network of territorial cooperation. There is evidence of emerging approaches worthy of future study in the future and raising questions such as whether territorial cooperation is increasingly localised, as opposed to regional and how durable are the new initiatives?

5. Conclusions

Interreg supports territorial cooperation across borders and UK partners have been active and engaged partners in various programmes for over 30 years. The UK government’s decision not to participate in Interreg programmes was taken despite the potential and precedent for non-EU Member States to engage, and support for ongoing participation from the Devolved Governments and a number of English territories. The decision also comes at a time of increased policy and theoretical interest in territorial cooperation.

This assessment of the experience of Interreg in the UK acknowledges the shortcomings and challenges of what can be a complex form of funding to work with. However, the assessment also highlights places and areas where Interreg has added value and focussed support. These include the particular impact and influence in UK territories facing specific territorial development challenges, such as the Highlands and Islands, Northern Ireland and South Wales. Drawing on works of literature on the qualitative added value of the policy, the value of territorial cooperation as a means of building critical mass, enhancing international profiles and engagement, developing and maintaining productive networks and adapting/managing change are highlighted.

While participation in future Interreg programmes is not impossible from a regulatory perspective and is something that is actively pursued by some stakeholders, Interreg is not the ‘only show in town’ as far as territorial cooperation is concerned. Taking a broader view of territorial cooperation shows that other territorially based forms of cooperation exist and could be key to maintaining some form of momentum in cooperation efforts, retaining key networks, relationships and know-how. Other forms of territorial cooperation also highlight how there can be flexibility through a range of ‘entry points’ for territorial cooperation, associations, formal programmes and mixed approaches; cooperation efforts change and evolve, participants come and go, arrangements can get more/less formal/lead to spin off initiatives; and cooperation initiatives ‘co-exist’ and work in complementary ways to the benefit of all partners.

This paper comes at a time of ongoing change and does not provide a comprehensive analysis. However, it demonstrates that there is evidence of emerging approaches worthy of future study in the future and raising questions such as whether territorial cooperation is increasingly localised, as opposed to regional and how durable are the new initiatives? Will devolved governments continue to look to Interreg as a form of cooperation to ‘return to’ or pursue new solutions?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Irene McMaster

Irene McMaster is a Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the European Policies Research Centre (EPRC) in the University of Strathclyde. Her research focuses on European Territorial Cooperation and regional development policy.

Heidi Vironen

Heidi Vironen is a Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the European Policies Research Centre (EPRC) in the University of Strathclyde. Her research focuses on European Territorial Cooperation, particularly in the European High North and Arctic.

Notes

1 With the exception of the 2021–2027 PEACE PLUS Programme.

2 In particular the works draw on research undertaken as part of McMaster et al. (Citation2021) Territorial Cooperation Around the Irish Sea, EPRC Report for Welsh Government, May 2021 and McMaster and Vironen (Citation2019) European Territorial Cooperation in Scotland post 2020, EPRC Report for Scotland Europa.

3 In 2021–2027 EU funds allocated to Cohesion Policy amount to EUR 392 billion, the European territorial cooperation element of this is 6.7 billion European Commission, DG Regio, European Territorial Cooperation https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/policy/cooperation/european-territorial/cross-border_en, accessed 27 January 2023.

4 Figures corrected as on 19.01.23 https://keep.eu/countries-and-regions/

5 https://keep.eu/, it is acknowledged that the data base of not complete for all programmes. Limitations on the data are listed https://keep.eu/faq/data-what-are-the-limitations-of-data-in-keep/

References

- Bachtler, J., & Taylor, S. (2003). The added value of the structural funds: A regional perspective, IQ-Net Special Report, June, Glasgow, European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

- Bergstra, M., Hagemejer, J., & Karunska, K. (2021). Restoring "lost connections" between the EU and the UK as a consequence of Brexit through local and regional authorities, European Committee of the Regions, Committee for Citizenship, Governance, Institutional and External Affairs - Publications Office of the EU.

- Blatter, J. K. (2001). Debordering the world of states: Towards a multi-level system in Europe and a multi-polity system in North America? Insights from border regions. European Journal of International Relations, 7(2), 175–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066101007002002

- Böhme, K., Haarich, S., Lähteenmäki-Smith, K., Polverari, L., Turró Bassols, L., & Andreu, A. (2003b). The territorial effects of structural funds, ESPON 2.2.1, Nordregio, Stockholm, 2003.

- Böhme, K., Josserand, F., Ingi Haraldsson, P., Bachtler, J., & Polverari, L. (2003a). Trans-national Nordic-Scottish co-operation: Lessons for policy and practice, Nordregio Working Paper 2003:3, Stockholm.

- CEC. (2016). Ex post evaluation of the ERDF and Cohesion Fund 2007-13, commission working document, Brussels 19.9.2016.

- CEC. (2020a). AGREEMENT on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12020W/TXT

- CEC. (2020b). Interreg regulation – confirmation of the final compromise text with a view to agreement, 11 December 2020. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13697-2020-INIT/en/pdf

- CEC, DG Regio. (2023). European territorial cooperation. Retrieved January 27, 2023 from https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/policy/cooperation/european-territorial/cross-border_en

- Colomb, C. (2007). The added value of transnational cooperation: Towards a new framework for evaluating learning and policy change. Planning, Practice & Research, 22(3), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701666712

- Cornwall County Council. (2021). Cornwall and Brittany to strengthen relationship. Retrieved March 2021 from https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/council-and-democracy/council-news-room/media-releases/news-from-2021/new-from-march-2021/cornwall-and-brittany-to-strengthen-relationship

- Dühr, S., Stead, D., & Zonneveld, W. (2007). The europeanization of spatial planning. Planning Practice and Research, 22(3), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701688245

- Faludi, A. (2007a). Territorial cohesion policy and the European model of society1. European Planning Studies, 15(4), 567–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310701232079

- Faludi, A. (2007b). Making sense of the territorial agenda of the European union. European Journal of Spatial Development, 5(3). ISSN 1650-9544. http://www.nordregio.se/EJSD/refereed25.pdf

- Farthing, S., & Carrière, J. (2007). Reflections on policy-oriented learning in transnational visioning processes: The case of the Atlantic spatial development perspective. Planning, Practice and Research, 22(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701637580

- Ferry, M., & Gross, F. (2005). The future of territorial cooperation in an enlarged EU, Paper prepared for 2nd International Conference, Benchmarking Regional Policy in Europe, Riga, 24-26 April 2005.

- FORUM GmbH. (2009). Impacts and benefits of transnational projects (INTERREG III B) Forschungen 138, Ed.: Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs (BMVBS) Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (BBR), Bonn.

- Government of Ireland and Welsh Government. (2021). Ireland wales shared statement. https://www.dfa.ie/media/dfa/ourrolepolicies/ourwork/Ireland-Wales-Shared-Statement-Action-Plan-Final.pdf

- Green, G. (2022). Proposal for an informal framework for co-operation across the Irish Sea space presentation to the Welsh Government. Irish Sea Cooperation Workshop, on line, 24 Nov 2022.

- Guillermo-Ramirez, M. (2018). The added value of European territorial cooperation. Drawing from case studies. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation. The urban book series (pp. 25–47). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74887-0_3

- Hörnström, L., Smed Olsen, L., & Van Well, L. (2012). Added value of cross-border and transnational cooperation in Nordic Regions, Nordregio Working Paper 2012:14. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13697-2020-INIT/en/pdf

- Kent County Council. (2014). Maximising the benefits from Kent's European relationships, select committee report, Kent County Council, February 2014, https://www.kent.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/12816/Kents-European-relationship.pdf

- Kent County Council. (2017). CLG select committee inquiry on Brexit and local government: Kent County Council response. https://democracy.kent.gov.uk/documents/s85282/FinalKCCCLGBrexitInquiryResponse141117.pdf, accessed 1.3.23

- Laganà, G. (2020). The added value of the Ireland-Wales cooperation programme. Retrieved September 14, 2020 from https://www.centreonconstitutionalchange.ac.uk/news-and-opinion/ireland-wales-programme

- Laganà, G., & Wincott, D. (2020). The added value of the Ireland Wales cooperation programme, Wales Governance Centre, July 2020.

- Lähteenmäki-Smith, K., & Dubois, A. (2006). Collective learning through transnational co-operation: The case of Interreg IIIB. Nordregio. 2006.

- Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government. (2017). Securing Wales’s future: Transition from the European Union to a new relationship with Europe.

- Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government. (2021). SCoRe Cymru guidance. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-04/score-cymru-guidance.pdf

- MacLeod, G. (2001). New regionalism reconsidered: Globalization and the remaking of political economic space. International Journal of Urban and Regional Studies, 25(4), 804–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00345

- Mairate, A. (2006). The added value of EU cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 40(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600600496

- Martin, R., & Tyler, P. (2006). Evaluating the impact of the structural funds on objective 1 regions: An exploratory discussion. Regional Studies, 40(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400600600546

- McMaster, I. (2017a). Brexit and Interreg: Would the UK be missed? http://www.cohesify.eu/2017/03/03/brexit-interreg-uk-missed/

- McMaster, I. (2017b). UK cross-border and transnational cooperation: Experiences, lessons and future, European policy research paper No. 100, European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde, pp. 30.

- McMaster, I., Bachtler, J., & Stewart, l. (2017). Eu cooperation and innovation – delivering value from our European partnerships. Report on the conference organised by Scotland Europa and Scottish Enterprise in partnership with the Royal Society of Edinburgh 29 September 2017. https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/63100/

- McMaster, I., van der Zwet, A., & Vironen, H. (2013). Territorial cooperation governance. In G. Gorzelak & K. Zawalinska (Eds.), European territories: From cooperation to integration? (pp. 155–116). Scholar.

- McMaster, I., & Vironen, H. (2017). The involvement of non-EU member states in European territorial cooperation programmes. European Structural and Investment Fund Journal, 5(3), 235–244.

- McMaster, I., & Vironen, H. (2019). European territorial cooperation in Scotland post 2020. EPRC Report for Scotland Europa.

- McMaster, I., Vironen, H., & Michie, R. (2021). Territorial cooperation around the Irish Sea. EPRC Report for Welsh Government, May 2021.

- Mederios, E. (2018). European territorial cooperation; The urban book series. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74887-0

- Mirwaldt, K., & McMaster, I. (2008). Reconsidering cohesion policy: The contested debate on territorial cohesion. EoRPA Paper 08/5 EoRPA paper presented at the 29th EoRPA meeting, Ross Priory, 6–8 October 2008.

- National Centre for Universities and Business. (2015). State of the relationship report 2015. https://www.ncub.co.uk/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&category_slug=reports&alias=335-state-of-the-relationship-may-2015&Itemid=2728

- North Sea Region Programme. https://northsearegion.eu/in-for-care/

- NPA. (2020). Northern periphery and arctic programme Covid-19 response group. https://www.interreg-npa.eu/covid-19/npa-response-group-and-projects/

- OECD. (2020). OECD programme on a territorial approach to the SDGs. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/territorial-approach-sdgs.htm

- Ohmae, K. (1993). The rise of the region state. Foreign Affairs, 72(1), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/20045526

- Panteia. (2010). 2000-2006 Interreg III community initiative ex post evaluation, Report to the European Commission.

- Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe: Significance and drivers of regional cross-border Co-operation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776403010002004

- Perkmann, M. (2007). Policy entrepreneurship and multi-level governance: A comparative study of European cross-border regions. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 25(6), 861–879. https://doi.org/10.1068/c60m

- Press and Journal. (2022). UK Government must replace lost EU funding for Scottish projects, says Minister, Nov, 21, 2022. https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/politics/scottish-politics/5067622/uk-government-must-replace-lost-eu-funding-for-scottish-projects-says-minister/, accessed 27.01.23

- Scott, J. (2002). Cross-border governance in the Baltic Sea Region. Regional and Federal Studies, 12(4), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004777

- Scottish Government. (2019). Arctic connections, Scotland’s arctic policy framework. https://www.gov.scot/publications/arctic-connections-scotlands-arctic-policy-framework/

- Scottish Government. (2022). European research funding should be protected, published 22 November 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2023 from https://www.gov.scot/news/european-research-funding-should-be-protected/

- Straits Committee. (2023). About the Straits Committee. https://straitscommittee.eu/

- Sundelius, B., & Wiklund, C. (1979). The Nordic community: The ugly duckling of regional cooperation. Journal of Common Market Studies, XVIII(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1979.tb00828.x

- UN Sustainable Development Goals. (2016). https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals#:~:text=The%20Sustainable%20Development%20Goals%20(SDGs)%2C%20also%20known%20as%20the,people%20enjoy%20peace%20and%20prosperity

- van Houtum, H. (2000). An overview of European geographical research on borders and border regions. Journal of Borderlands Studies, XV(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2000.9695542

- Welsh Government. (2023). Irish sea framework: Guidance, Welsh Government 21 February 2023, https://www.gov.wales/irish-sea-framework-guidance