ABSTRACT

The UK economy is one of the most geographically unequal among OECD countries, with London's lead having increased since the mid-1980s. The UK is also one of the most centralised, in terms of the overwhelming concentration of economic, financial, political and institutional power in the capital, London. A key question, therefore, is whether the latter feature is a cause of the former. This paper focuses on one aspect of this question, namely London's dominating role in the UK's financialised, neoliberal-globalised growth model that has held sway for the past forty years. It is often argued that London's pre-eminence in finance acts as an engine of national growth, delivering benefits to all regions through ‘trickle down' effects. We argue that these claims are exaggerated and that much more need to be known about London's negative impacts on other regions and cities, about the geographical dimensions of what some have labelled the ‘finance curse'. We argue that such negative effects are integral to the growth of regional inequality in the UK. The Government's new ‘Levelling Up’ policy, though innovative in some respects, remains subordinate to the promotion of London and finance, and is unlikely to decentre and spatially rebalance the economy.

To suggest social action for the public good to the City of London is like discussing the Origin of Species with a bishop 60 years ago … An orthodoxy is in question and the more persuasive the argument the greater the offence. (J.M. Keynes, Citation1926)

For years our prosperity has been pinned on financial wizardry in London’s Square mile, with other sectors and other regions left behind. That imbalance left us hugely exposed when the banking crisis hit. And now Britain has a budget deficit higher than at any time since the Second World War. We need to spread growth across the whole country and across all sectors. (N. Clegg, Citation2010)

Introduction

The announcement by the UK Government in early-2022 of a major new spatial policy initiative, directed at ‘levelling up’ the economic geography of the country (HM Government, Citation2022) marked the latest phase in almost a century of British regional and urban policies aimed at reducing geographical inequalities in economic prosperity and performance. The basic objective of ‘levelling up’ had been proclaimed by Government two years earlier:

[T]oo many parts of the country have felt left behind. Neglected, unloved, as though someone had taken a strategic decision that their fate did not matter as much as the metropolis [London]. So I want you to know that this Government not only a vision to change this for the better. We have a mission to unite and level up … We will double down on levelling up … To mend the indefensible gap in opportunity and productivity and connectivity between the regions of the UK. (Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Citation2020)

As the nation’s capital city, primary economic centre, main concentration of media and cultural production, seat of national government, and – of particular significance – one of the world’s leading financial centres, London has always exerted a dominating influence over UK national life. Indeed, the UK economy is one of the most centralised in the OECD bloc. As The Economist, hardly a left-leaning publication, has commented:

So much that is wrong with Britain today stems from the fact that is unusually centralised. Draw a circle with a 60-mile radius from Charing Cross [central London]. Within that circle the vast majority of public spending is administered … all major decisions pertaining to foreign policy, defence, the economy, the national debt, interest rates, [taken] … all of the major banks, the major theatres, media and art worlds, the five best universities, 70 percent of the FTSE, most of Britain’s airport capacity [located] … (The Economist, Citation2017)

There are those who contest any such suggestion, and argue that London is the nation’s economic dynamo (‘the goose that lays the golden egg’) that benefits the rest of the UK, for example, through the surplus taxes paid by London businesses and residents that help to support nation-wide social and public services, by generating the largest external trade surplus, and through acting as a major customer for the products and services of the nation’s other cities and regions (Greater London Authority, Citation2016, Citation2019; Tetlow, Citation2017). For these commentators, London is the ‘cash cow’ that ‘subsidizes’ northern regions of the UK, so that attempts to ‘level up’ those regions runs the serious risk of diverting resources away from, and hence ‘levelling down’ London, undermining its dynamism and competitiveness (Adonis, Citation2021).

These concerns notwithstanding, we know much less about the potential distortions, disbenefits and costs that global cities and global financial centres like London can impose on their national economies, and how those distortions and costs can hinder the economic growth and development of other domestic regions and cities. Our argument in this paper is that the problem of ‘left behind’ regions, cities and places in the UK cannot be divorced from London’s key role in, and influence on, the UK’s national political economy. A marked change in the nature and orientation of national economic management took place at the end of the 1970s, from a post-war Keynesian-welfarist model to a neoliberal-financialisation-globalisation model, in which finance was almost completely deregulated and singled out as the nation’s prime ‘growth engine’.

To power that engine, London’s role as a global financial centre has been repeatedly prioritised and promoted (see, for example, Davis, Citation2022; Shaxson, Citation2018). In a very real sense, a ‘strategic decision’ (to quote Johnson, Citation2022) was indeed made by successive Governments that the fate of the UK’s ‘left behind’ places did not matter as much as the finance-driven success of London, the metropolis. As Davis (Citation2022) documents, the variant of neoliberalism prosecuted by the Thatcher Governments in the 1980s and 1990s was quintessentially that of financialisation and this was focused primarily on promoting London’s competitiveness as a global financial centre.

Many of the central figures of the Thatcher Revolution came not from business but from the [financial] City … Such people first took over the Treasury and then the Department of Trade and Industry … In effect a political coup took place … City and banking perspectives became a powerful influence in government economic policymaking and institutional management. (Davis Citation2022, pp. 56–57)

Our argument in this paper, then, is that just as London’s rising economic performance over recent decades has been closely tied up with the UK’s financialised neoliberal growth regime, so too has the slower economic growth of much of the rest of the UK. The implications for ‘levelling up’ are far reaching. We conclude that while the Government’s new levelling up policy programme contains some important measures to help spread economic prosperity and opportunity more evenly across the UK, it has some key limitations (Martin et al., Citation2022), and will have to go much further if it is to secure a much-needed decentring of the national economy.

A city apart? How London has grown away from the rest of the UK

London has long been regarded as the UK’s economic ‘powerhouse’. Even during the Industrial Revolution and Victorian periods, when economic development was proceeding apace in the northern industrial regions of Britain, London was the largest manufacturing centre of the country, employing over 500,000 manufacturing workers in 1861 (Hall, Citation1962). It was also by far the wealthiest part of the country, which reflected its predominance in imperial administration, finance and mercantile services. The importance of northern regional manufacturing and trading centres such as Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Newcastle, Sheffield, Birmingham, and Glasgow notwithstanding, more than 50 percent of middle-class income in Victorian times was accounted for by London (Rubinstein, Citation1977).

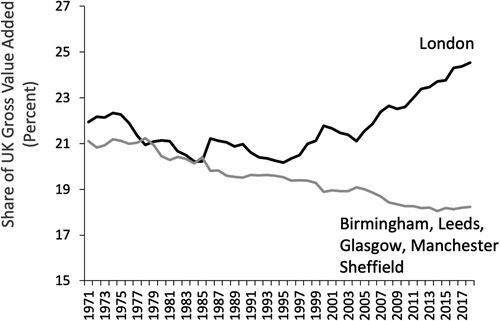

It has been estimated that in 1871 London’s per capita GDP was 47 percent above the national average (Crafts, Citation2005). Also using historical estimates of regional per capita GDP, according to Geary and Stark (Citation2016) for the first six decades of the twentieth century London’s advantage averaged around 40 percent above the national average. Over the past five decades, and using per capita GVA rather than per capita GDP,Footnote1 this lead has increased, from around 40 percent to more than 80 percent above the national average by 2021, and more than twice the per capita GVA of the North East region (see ). This overwhelming dominance is mirrored by London’s increasing share of the UK national economy. In 1971, London accounted for some 22 percent of national gross value added (GVA). By comparison, the next biggest city, Birmingham, accounted for just over 7 percent, and the next, Manchester, 4.5 percent. Even the five next biggest regional cities after London – Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Newcastle and Glasgow – together collectively accounted for no more than London’s share (). The shares of both London and this group of five cities all declined up to the mid-1980s, primarily because of deindustrialisation.Footnote2 But since then, while the five cities’ share of national output has continued to fall, London’s share stabilised in the second half of the 1980s, and then increased progressively, to reach almost 25 percent by 2018.

Figure 1. Shares of UK Output (Gross Value Added, in constant £2016): London and Five Next Biggest Cities, 1971–2018. Sources and Notes: Data from Cambridge Econometrics and Office for National Statistics. London consists of the 32 boroughs plus the City of London; Other cities comprise the relevant Local Authority Districts as defined by the Core Cities Group (https://www.corecities.com).

Table 1. London’s Pulling Away from the UK’s Regions: Per Capita GVA 1971-2021, £2019, UK = 100.

The claim is often made that London’s economic success exemplifies the advantages and efficiencies that derive from and reinforce the agglomeration externalities generated by the city’s economic size and its density of businesses, services and population. There is a substantial literature in urban economics that extols the virtues of such agglomeration (for example, Ahrend et al., Citation2017; Combes et al., Citation2012; Glaeser, Citation2010, Citation2011). Indeed, the notion of ‘agglomeration’ as a positive force has hi-jacked urban economics and the policy community alike, to the extent it is now in effect a non-questioned self-evident truth. The success of London’s finance, banking and insurance leadership is typically cited as evidence of the city’s agglomeration advantage. The city is also used as a ‘role model’ (Coffey et al., Citation2022), and frequently held up as an exemplar of what could be achieved in the UK’s ‘second tier’ cities – such as Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield and others in northern Britain – if only they were bigger, since they all lie below the rank-size line fitted to the UK’s urban hierarchy with London at its top (see, for example, Centre for Cities, Citation2020; Overman & Rice, Citation2008). But assertions that the UK’s second-tier cities are ‘too small’ need to be scrutinised carefully.Footnote3 The UK’s second cities show low productivity relative to their size, so it is not clear how increasing size by itself would remedy this deficit. London’s exceptional output growth in recent decades has been mainly driven by the dramatic expansion of its financial economy. While this has certainly been aided by agglomeration effects, London’s financial economy has benefited enormously from the deregulation policies of central Government and its prioritisation of finance as the nation’s ‘growth engine’, with London as its main driving force.

London and the UK’s financialised economic growth model

London’s primacy as the UK’s main financial centre dates back to the seventeenth century when the key institutions of the Bank of England, Lloyds Insurance, and the Stock Exchange were all established.Footnote4 In the nineteenth century, regional banks and stock markets had played an important role in funding Britain’s Industrial Revolution and its development in northern cities and towns. But by the early years of the twentieth century the UK’s banking system had become focused in London, in part because of the city’s role in financing the British Empire, in part because regional stock markets had become closely integrated with the London market, and in part because a process of bank mergers had concentrated activity in just a handful of banks, most of which became headquartered in London.Footnote5 This increasing concentration of finance in London continued after the Second World War, especially from 1960s onwards, when the city became the international centre of the new Eurodollar market (see Martin, Citation1994), and its role as a major global financial centre began to expand.Footnote6

But it was the Thatcher Government’s deregulation of the British financial system in 1979 and especially in 1986 (the so-called ‘Big Bang’) that unleashed an unprecedented growth of London’s financial system and power, both nationally and globally (Martin, Citation2013). This deregulatory strategy was itself part of a largescale political shift from the post-war model of economic growth based around the pursuit of full employment and an expanding welfare state, to a model characterised by the rolling back of regulation, the privatisation of large sections of the public sector, a de-prioritisation of manufacturing industry, the encouragement of financial activities, and a highly permissive stance towards globalisation: essentially a shift to a financialised and globalised regime of accumulation and a neoliberal mode of socio-economic regulation.

London’s financial nexus both led and supported this neoliberal shift in national policymaking, spearheading the pressure for a globally-orientated, deregulated financial system whilst also standing to benefit the most from such a development (Davis, Citation2022; Shaxson, Citation2018). The promotion and protection of London’s competitive position as a global financial centre became a key over-riding Government concern during both the Thatcher Governments and the New Labour Governments that followed, and continues to this day. As Davis (Citation2022) documents, the 1980s and 1990s were decades when ‘financial City-think’ effectively infiltrated central Government in London, primarily the Treasury and the Bank of England, but even the Department for Trade and Industry:

Neoliberalism, like capitalism, comes in many varieties, The one adopted in Britain was very much influenced by people with financial market backgrounds. They knew a lot about the City and capital markets but relatively little about manufacturing and regional industries. Markets to them were all about transactions, not production, labour or materials. Industry was part of an ageing foreign space for them. Finance was their new world. (Davis, Citation2022, pp. 82–83)Footnote7

London-based financial institutions have also played a central role in the UK’s financialised-neoliberal economic policy model itself, including the privatisation programme, (the selling-off over the 1980s and 1990s of large swathes of public industries, utilities and services, amounting to more than £70billion), and the private finance initiative or PFI (the private financing of public sector capital projects, such as hospitals and schools, another £300billion). Such was the success of London-based institutions in executing the privatisation programme (House of Commons Library, Citation2014; Martin, Citation1999), that by the early-1990s they had also become leading players in privatising state activities around the world. At the same time, PFI projects have involved complex financial consortia of private investors and individual lenders, often London-based, to which the agreed long-term contracted and indexed repayments, interest, rents and charges, are made. Further, according to Shaxson (Citation2018),

PFI is just part of a bigger picture of Government spending via the private sector … a third of the UK Government ‘s annual budget now goes on privately run but taxpayer-funded public services. These arrangements also tend to involve similar geographical flows out from the British regions and down into the London nexus. (Citation2018, p. 22)

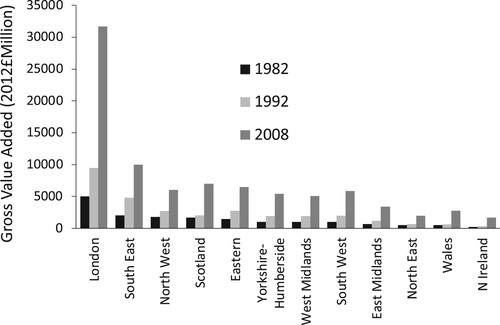

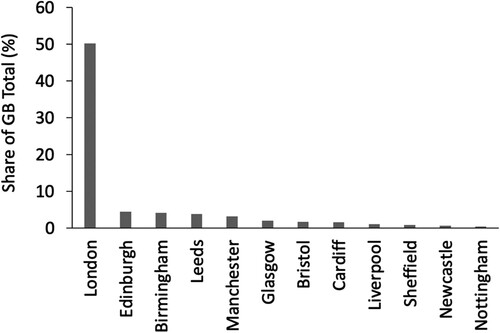

London prospered considerably from this new economic model of globalised financialisation. Nationally, the Gross Value Added generated by banking and finance grew sixfold in real terms between 1982 and 2008, almost doubling in the 1982–1990 boom years, and more than trebling again in the subsequent boom phase of 1992–2008. While every major region of the UK shared in the growth in output in banking and finance over this period, London was the undisputed prime beneficiary – indeed, driver – of the process, substantially increasing its dominance as the nation’s primary financial centre (; see also Gieve, Citation2007). London accounts for 51 percent of the UK GVA attributable to financial services, more than ten times the next most important financial centre, Edinburgh ( and Hutton, Citation2022). London has also increased its pivotal role in the global financial system, so that it now accounts for 43 percent of global volumes of foreign exchange trade, 50 percent of global trading in interest rate derivatives, and nearly 40 percent of European asset management.Footnote9 Further, it accounts for 81 percent of the headquarters of UK-based investment management firms, 93 percent of the funds managed by those firms, and 75 percent of the workforce in this sector.Footnote10 According to London&Partners (Citation2022), a Mayor of London backed organisation for promoting businesses in the capital, London is a world leader in the expanding fintech industry, with almost half of all European investment into that sector, and more than New York.

Figure 2. London’s Increasing Dominance of the UK’s Financial Economy – Gross Value Added by Financial Services: London and the Regions, 1982–2008. Sources: Data from Cambridge Econometrics and Office for National Statistics.

Figure 3. London’s Share of the UK’s Financial Economy – Gross Value Added by Financial Services: London and Other Major Cities, 2019. Sources: Data from Office for National Statistics.

Not surprisingly, the ‘light touch’ approach to financial regulation followed by the UK Government has also made London a major destination for the financial assets of a wealthy global elite, more attractive than New York (Atkinson et al., Citation2017; Cunningham & Savage, Citation2017; Neate, Citation2021). The spending power of this class of plutocrats has led to a conspicuous consumption and construction boom. London real estate has effectively become an unmonitored and unscrutinised ‘safe deposit box’ for a transnational elite, including Russian oligarchs and Middle Eastern billionaires (Fernandez et al., Citation2016). UK Governments did little to regulate or control such activity.Footnote11 Indeed, in a deliberate move to make the City of London the top global centre for trading the Chinese renimbi, in 2013 the British Chancellor of the Exchequer not only relaxed the UK’s banking rules to let Chinese banks operate in London with reduced oversight, but also provided additional enticement by allowing Chinese companies to own stakes of up to 100 percent in British power stations, a strategic component of the UK’s public infrastructure (Tőpfer & Hall, Citation2018).

It has been this dominant imperative, of both the UK Government and City of London financial institutions, to take almost whatever steps are needed to ensure London’s ‘competitiveness’ as a global financial centre, that has helped propel its economic growth (Amin et al., Citation2003; Shaxson, Citation2018). And the national and international success of London’s banking, finance, and associated services has been repeatedly celebrated by successive Chancellors of the Exchequer; by the Greater London Authority, the devolved regional governance body for Greater London; and by the main business groups and organisations that represent the capital’s financial interests, particularly TheCityUK, the one-stop lobbyist run by the City of London Corporation, the local authority for the financial Square Mile surrounding the Bank of England (Eagleton-Pierce, Citation2023; Green, Citation2018; James et al., Citation2021).Footnote12

Such had become the UK’s and London’s dependence on the finance sector, that the British Government went to unprecedented lengths to bail it out during the financial crisis of 2007–2008. The initial support, both direct and indirect, pledged by the UK government reached £1.162 trillion; although this had fallen to £456.33 billion by the end of March 2011, this latter sum still amounted to more than 30 percent of UK GDP at that time (National Audit Office, Citation2011). A disproportionate amount of this support went to London-based banks and enabled London to weather the crisis far better than other regions and cities of the UK (Gordon, Citation2016; Overman, Citation2011; Roberts, Citation2018). And despite certain restrictions imposed by the UK Government to increase the robustness of the financial sector, very few of London’s financial jobs decamped to cities in mainland Europe which tried to woo them, nor did any of the hundreds of foreign financial institutions in London choose to leave.

More worrying has been the UK’s departure from the Europe Union (‘Brexit’). To ensure the ‘global competitiveness’ of London’s financial institutions in the ‘post-Brexit’ era, the Government has announced (as of December 2022) another ‘bonfire’ of regulations – a Big Bang 2.0 – in effect undoing and relaxing the very rules imposed after 2008. So, among the 30 reforms announced, the cap on bankers’ bonuses has been removed, the firewall between retail and investment activities dismantled, and capital rules introduced following the crisis are to be relaxed. According to the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer,

This country's financial services sector is the powerhouse of the British economy, driving innovation, growth and prosperity across the country … Leaving the EU gives us a golden opportunity to reshape our regulatory regime and unleash the full potential of our formidable financial services sector. (Jeremy Hunt, 9 December 2022).Footnote13

Has London’s economic success benefited the regions?

If London thrives, it is frequently contended, then the other regions and cities of the UK thrive. Three arguments are typically invoked in support of this claim: that London generates a large fiscal surplus – a surplus of taxes paid to Government over spending received from Government – which helps pay for public spending in other, fiscal-deficit, regions; that London runs a trade surplus which helps the UK’s balance of payments, and at the same time makes significant purchases of goods and services from other UK regions, and cities and thus supports businesses and jobs in those places; and, thirdly, that London’s economic growth and prosperity ‘trickles down’ to the rest of the country.

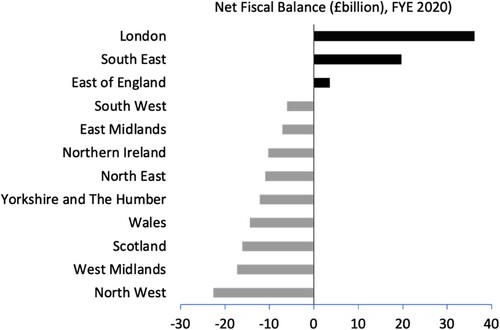

London is frequently singled out as the region that runs a significant fiscal surplus (see Centre for Cities, Citation2015; City of London Corporation, Citation2014; Tetlow, Citation2017). Official data show that only three regions – London, the South East and East of England – run surpluses, with London having the largest, some £36.1billion in 2019/20. All other regions run a fiscal deficit (ONS, Citation2021; ). It might appear reasonable, therefore, to claim that London’s surplus offsets a significant proportion of the fiscal deficit in other regions (some 30 percent of the total of £117.1 billion in 2019/2020).

Figure 4. Net Public Fiscal Surplus (Tax Revenue minus Expenditure): London and the Other UK Regions, Financial Year 2019/2020. Source: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicsectorfinance/articles/countryandregionalpublicsectorfinances/financialyearending2020.

But spatial outcomes are not so straightforward. In fact, on most categories of Government public spending on economic functions and affairs, and especially capital spending such as transport, London receives significantly more per capita than all other English regions (see ). It is the concentration of transport and public R&D funding in London and its hinterland that are especially consequential for growth and productivity (Stansbury et al., Citation2023). It is precisely this bias in public spending towards London that has become a source of complaint by local policymakers in northern cities and regions. While some of London’s higher per capita funding might well be justified in terms of the high cost structures (for land, labour and so on) in the capital, this is unlikely to fully explain the city’s disproportionate share. It also

Table 2. Identifiable public expenditure by function, per capita, London and the UK’s other regions, Annual Average 2017/18–2019/20 (Indexed UK = 100).

gives the lie to the oft-made argument that London’s prosperity exemplifies the ‘benefits of market forces’. The fact is that London’s economy is no less, and on most counts more, underwritten by Government spending than other English regions.

A second argument is that London likewise plays a pivotal role in the UK’s trade balance (). Although London runs a large deficit in goods trade, second only to the surrounding South East region, it has a very large trade surplus in services, by far outstripping any other region of the UK (ONS, Citation2021). Much of this surplus is accounted for by finance and insurance, with London making up some 45 percent of national exports in these sectors. The net result is that London runs an overall trade surplus, the largest of any region, some £28.7 billion in 2019, sufficient to offset more than a third of the £79 billion deficit of those regions with a negative trade balance in that year ().

Table 3. International Trade Balances (in £billions), London and the Other UK Regions, 2019.

Exactly how far and in what ways London’s international trade surplus benefits other UK regions and cities is an unresearched issue. Theory suggests that regions with persistent trade surpluses will grow faster than those with persistent trade deficits (as predicted, for example, by the dynamic Harrod trade multiplier: see Thirlwall, Citation1980). At the same time, a recurrent claim is that London’s growth is an important source of demand for the goods and services of the other UK regions, indeed, that London imports more from the rest of the UK than it does from outside the UK (GLA, Citation2019), although it has also been estimated that London imports on average only 3 percent of intermediary goods produced in each other region of the UK (see Greater London Authority, Citation2016, Citation2019, Citation2020). The problem is that no official data on inter-regional trade within the UK are available, so that analyses use estimates, for example derived from national input-output tables. Until proper domestic inter-regional trade flow data are collected and made available for the UK’s regions, it is difficult to assess at all accurately how far London acts as a significant export market for the rest of the UK’s cities and regions.

Such issues have not, however, deterred commentators from arguing that London’s prosperity and growth ‘trickles down’ from the capital to the rest of the country. The idea has an obvious appeal to policy-makers seeking to justify the concentration of public resources in London. Thus, when he was Mayor of London, Boris Johnson repeatedly championed the view that the best way of reviving economically lagging places across Britain was to pump yet more public money into London itself. During his first term of office as Mayor he declaimed that:

If you want to stimulate [your cities] then you invest in London, because London is the motor not just of the south-east, not just of England, not just of Britain, but of the whole of the UK economy. (Boris Johnson, Conservative Party Conference Speech, Citation2009)

I’m making the case now to central government for more funding for London. A pound [of Treasury money] spent in Croydon [a borough of London] is far more value to the country from a strict utilitarian calculus than a pound spent in Strathclyde. Indeed, you will generate jobs and growth in Strathclyde far more effectively if you invest in Hackney or Croydon and other parts of London. (Boris Johnson, Interview with Huffington Post, Citation2012)

This is not to argue that London’s economic success confers little benefit on the UK’s other regions and cities. But statements extolling such benefits rarely give proper weight to the other side of the ‘balance sheet’, that is to the negative effects and distortions of London’s dominant role in the UK’s financialised economy on the country’s other regions and cities.

The limits and costs of London’s financial economy: disbenefits for the regions

According to the Treasury’s (Citation2021) review of the UK finance sector, led by Chancellor Rishi Sunak, the financial services sector has ‘a critical role as a contributor and enabler for the wider economy. Innovation and dynamism in financial services will increasingly play a crucial role in levelling up the regions and nations of the UK’ (page 12). The extent to which London’s financial sector will drive, contribute to and enable regional ‘levelling up’ across the country is, however, far from self evident.

In recent years, a growing body of analysis has argued that too much finance – increasing financialisation of the economy and an ever-expanding size of the finance sector – harms the host economy and society: what has become termed the ‘finance curse’ (Baker et al., Citation2018; Christensen et al., Citation2016; Shaxson, Citation2018). Essentially, the argument is that once finance grows beyond a certain size relative to the rest of the economy, it begins to have negative impacts, including the crowding out of other types of activity, dampening productivity, heightening instability and volatility, and causing poor overall economic performance, while spilling over to shape and distort the social, political, and cultural landscape more broadly (Arcand et al., Citation2015; Baker et al., Citation2018; Cecchetti & Kharroubi, Citation2012, Citation2015; Christensen et al., Citation2016; Epstein & Montecino, Citation2016).Footnote17

In their pioneering work, for example, Baker et al. (Citation2018) estimate that the net costs of the finance sector in the UK over 1995–2015 to be around £4.5trillion (two years’ worth of national GDP), made up of £2.7trillion ‘misallocation costs’ and £1.7trillion ‘crisis costs’ (associated with the financial crisis and associated recession of 2008–2010).Footnote18 Misallocation costs are defined as the price of diverting resources away from non-financial sectors into finance, thereby lowering investment in tradable industries and innovation, leading to a weakening in productivity growth (Benigno et al., Citation2020). Baker et al maintain that these costs are a direct reflection of the size of London’s role in the UK’s finance sector and the city’s highly prominent position in world financial markets.

Historically, the UK banking system has increasingly shifted its focus away from funding industry. Whereas in 1950, some 60 percent of bank lending in the UK went into the private non-financial business sector, by 2010 this had fallen to a mere 10 percent (Bank of England, 2014). British banks have instead preferred to direct ever-increasing shares of their loans to other banks and financial institutions, to real estate, and overseas investment. Since 1980 for example, banks resident in the UK has shown a far greater international exposure than banks in any other global financial centre (Financial Times, 15 December Citation2020). By 2020, London banks had liabilities overseas worth $5.1 trillion (more than twice UK Gross National Income), and controlled overseas assets worth $4.9 trillion (Citation2020).

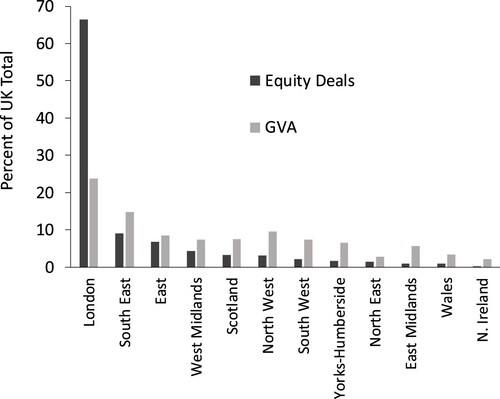

Moreover, even when London firms do channel funding into UK businesses, there is considerable evidence of a pronounced distance decay effect. London contains by far the largest concentration of venture capital and private equity firms, and perhaps not surprisingly it has the highest share of total national equity deals in small and medium sized firms: it captures 66 percent of the national flow of equity finance into SMEs, almost three times its share of national gross value added (), and by comparison other regions lack capital markets of any depth.Footnote19 As a result of this spatial proximity bias, even after controlling for firm and industry effects, small firms based outside of London and the South East have a 50% lower probability of securing an equity investment deal, and this probability is further compounded by differences in the sizes of deals with most regions outside London receiving significantly lower deal sizes (Wilson et al., Citation2019). Of course, this effect has both demand and supply causes that co-evolve through time, but it geographically circumscribes London’s benefits. The spatial bias in SME equity funding is not simply due to the large size and dynamism of the London economy, but reflects the overwhelming concentration of the venture and equity market in London itsel (Klagge et al., Citation2017).

Figure 5. Share of UK Equity Finance deals (SMEs), and Share of Gross Value Added, London and other UK regions, 2021. Source: British Business Bank (2021) Regions and Nations Tracker: Small Business Finance Markets (https://www.british-business-bank.co.uk/research/regions-and-nations-tracker-2021/).

Baker et al. (op cit) identify three types of misallocation effect that require investigation. The first is harmful financial agency, the tendency for financial actors to engage in risky speculative behaviour, in pursuit of ever larger profits, fees and bonuses, behaviour that historically has repeatedly led to cycles of booms and harmful crashes (Aliber et al., Citation2001). Given the liberalised and globalised financialised system built after 1980 which allowed and rewarded ever greater levels of ‘cleverly concealed’ risk, it was almost inevitable that it would eventually lead to a crash. Not only did the 2007–2008 crash cause one of the deepest and longest recessions in UK history, it also appears to have permanently shifted the UK economy onto a lower growth path.Footnote20 Wolf (Citation2015) estimates that by the end of 2013, UK GDP was 14 percent below where it would have been if it had followed the postwar trend. The slowdown in growth since the crash has affected every region of the UK, including London. But the fact is that London undoubtedly benefited most from the Government’s bailing out of the banking system, and it recovered from the crisis much faster than any other region, enabling it to actually increase its relative prosperity (see ). At the same time, cities in northern regions have borne the brunt of the massive public spending cuts imposed by the Government after 2010 in its bid to pay for its bailing out of the banks (Centre for Cities, Citation2019; Gray & Barford, Citation2018).

Table 4. London’s much faster recovery from the Financial Crisis: Regional Per Capita GVA (Balanced, Current Prices), 2009 and 2020 (UK = 100).

The second type of misallocation effect identified by Baker at al is what they call structural gravitational forces, involving the pull that finance, and its main centre, London, exerts within the economy by attracting both financial and human capital from other sectors and regions where it could be profitably and productively deployed (that is, rent attraction and brain drain). This is perhaps the root cause of the apparent reluctance of London’s financial system to invest equity and long-term ‘patient’ capital in non-financial industries. Concern has also long been expressed about the ‘vacuum cleaner’ effect of

London in drawing human talent out of other areas of the UK. As early as 1919, the prominent political geographer Sir Halford Mackinder had warned about the way that London sucks in human talent from the rest of the country and how national interests become dominated by that city:

As long as you allow a great metropolis to drain most of the best young brains from local communities, to cite only one aspect of what goes on, so long must organisations centre unduly in the metropolis and become inevitably an organisation of nation-wide interests and classes. (Mackinder, Citation1919, pp. 131–132)Footnote21

One of the big problems we have at the moment … is that London is becoming a giant suction machine draining the life out of the rest of the country. (Cable, Citation2013)

Another such gravitational force is the flow of the UK’s pension monies into London, where the majority of fund managers and institutions are based. Pension contributions and savings originate right across the various cities and regions of Britain and are channelled into and controlled by financial institutions and fund managers based in London. Martin and Minns (Citation1995), for example, found that some 95 percent of UK pension funds are controlled from London and the South East. This spatially centralised market, worth around £3 trillion, pursues liquidity rather than productive investment, and is intricately intertwined with London’s financial nexus, generating fees and charges that cycle mainly within London’s economy.

A third type of misallocation arising from the over-sized concentration of finance in London is that of unintended distortionary price effects (Baker et al, Citation1995). The inflow of finance into London from across the UK and from across the world has a number of distortionary effects. At one level, it fosters a strong currency, the protection of which has been a long-standing aim of the UK Treasury policy, irrespective of the needs of industry. During booms, rising property prices and financial asset values attract investment way from long-term productivity-enhancing projects, leaving manufacturing underfunded (Kaminska, Citation2016). In effect, London’s financial dominance ‘crowds out’ other activities (Krugman, 2016), and regions. Further, the fees charged on the huge daily volumes of financial transactions, the very high salaries and bonuses of many of those managing those transactions, and the influx of property investments from abroad, have all helped fuel a dramatic inflation of property prices in London since the early-1990s. Such property inflation has not only posed problems for low paid workers in London itself, but fuels house price inflation waves across the UK more generally, and creates problems for national economic policy.

As suggested by The Economist quote in the Introduction, the geographical over-centralisation of the UK economy in London is multi-faceted. We have focused here mainly on one particular aspect of this centralisation, but a crucial one, namely London’s role as a dominant financial centre and the hold this has had on national policy making, especially over the past four decades or so, and the negative implications this in turn has had for other, especially northern, regions and cities of the UK.Footnote22 Paul Collier (Citation2018a) puts the problem in these stark terms:

The mighty productivity of today’s London grows out of advantages to which the whole nation has historically contributed … Yet today, the prosperity of London is tightly clasped in and around the metropolis: the rest of the country must feel as if it is living under not so much the ‘yoke of capital’ as the yoke of the capital. It is time to cast it off. (Paul Collier, ‘How to save Britain from London’, Prospect, Citation2018a; emphasis added)

Conclusion: London, levelling up and spatially de-centring the UK’s political economy

Our basic argument in this paper is that the problem of regional economic inequality in the UK, and especially the falling behind of much of northern Britain, cannot be understood in isolation from the concentration of economic, financial and political power in London, and the strategic policy priorities of the state, itself overwhelmingly centralised in London. The recent slowdown of productivity growth in London and uncertainty about the future of some financial sectors have led some commentators to suggest that London’s economic dynamism is now weakening and itself presents a regional problem (see Wolf, Citation2023). However, at present, we do not know whether a temporary slowdown heralds the start a longer-term convergence in fortunes (Martin & Sunley, Citation2023), and it is important to remember that during past episodes of decline and transformation, such as during the growth of consumer industries in the 1930s, and the decline of manufacturing from the 1970s, London has proved adept at using both economic and political resources to reinvent its economic base and build new sources of growth. In our view, it is unlikely that London’s role in the UK’s regional problem will dissipate and lose significance without policy reform (Martin et al., Citation2021).

How then to reduce the highly geographically skewed, and overly financially-orientated nature of British capitalism? Collier’s own suggested policies are a mix of the radical, such as higher taxes on those sources of income, earned and unearned, that are produced by agglomeration in London, and the more conventional, such as improving the skills and training of those living in northern cities and towns, stimulating investment in knowledge-based activities in these areas, and encouraging more agglomeration around and between northern cities (Collier, Citation2018a; Citation2018b). Useful though these ideas may be, they seem to us to merely scratch at the surface of the problem of how to decentre the UK’s economy away from an overdependence on finance and London.

Over the decades, the UK state has built an institutional, regulatory and innovation support system that funds and encourages the growth of the London region as a global financial centre and as a core for public scientific research. Such is the strength of this system and its priority throughout all areas of government that it is rarely identified and discussed. In contrast, other regions of the economy have not benefitted from equivalent institutional and financial systems that are attuned to the needs of their economies. Building more supportive regional institutional frameworks for economic growth and productivity is a long-term programme. The Levelling Up White Paper (HM Government, Citation2022) takes some first steps by promising more devolved ‘metro-mayoral’ combined authorities to add to the few that have been established in recent years. Devolving certain fiscal and other powers, and a degree of policy autonomy, to such city-region authorities is certainly a move in the right direction. As is the ‘mission’ to shift a larger share of public R&D support towards regions outside of London and the South East. But the Government’s vision of spatial devolution is one of a geographically discontinuous patchwork of (self-selecting) bodies with circumscribed powers, within a system of competitive bidding for discretionary funds. What is needed is a comprehensive, nation-wide federated system of city-region authorities to which as much as possible of central Government mainstream spending and extensive fiscal powers should be devolved.

However, the Levelling Up White Paper stops way short of such an ambition. Equally striking is the omission of any real consideration of the changes that are needed to establish a more regionally balanced financial system. London should of course remain a leading centre of international finance for which it has a significant global competitive advantage. But a key aim of ‘levelling up’ should be to establish a functioning system of regional finance and capital markets, especially for SMEs (Huggins & Prokop, Citation2014; Klagge et al., Citation2017). This should be a key part of a radical institutional reform that would give city-regional authorities the necessary capacities and resources to develop their own economic frameworks that could promote a much more spatially balanced mode of growth.

Such regionally-based finance-capital markets would comprise both public and private institutions. The Bank of England used to have city-region branches (including in Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, and Newcastle), established in 1826–1828 to deal with problems caused by the failure of local banknote-issuing banks. From the 1980s these were replaced by regional ‘agencies’, of which there are 12, including one for Greater London based in the City of London. Their stated role is to maintain contact with local industry and commerce and report back to the Bank of England Head Office in London on the economy as seen and experienced by local firms (Beverly, Citation1997). It is far from clear, however, just how much influence these regional agencies have on Bank of England policy, and how far the views of the agency in the City of London trumps those from the regions. There would seem to be considerable opportunity to strengthen the role and influence of these regional agencies, and for embedding them more deeply into their regional economies, and so helping to avoid the London-centrism of the Bank of England.

The same argument could be applied even more forcefully to the Treasury. As we have noted, this institution has long had an enormously influential role in Government economic policy, and in protecting and promoting London’s financial nexus (see Davis, Citation2022; Lee, Citation2018). The proposal in the Levelling Up White Paper to establish a Treasury office (together with branches of other Government Departments) as part of a new Economic Campus in the northern town of Darlington is a welcome initiative, although the precise role and influence of this outpost is as yet unclear. But why not have other such economic campuses with regional offices of the Treasury, say in Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, and Newcastle, alongside decentralised branches of the Bank of England? The Government owned British Business Bank, currently based in Sheffield, could also have offices in these cities. And what about re-creating regional stock markets, orientated to raising finance for and trading stocks and shares for regional businesses? The former Manchester Stock Exchange, for example, was opened in 1836 for this purpose. By the end of the 19thC it had become the busiest of the regional exchanges for industrial stocks in the country (Campbell, Citation2016). There is a strong case for re-establishing such regional stock markets to cater explicitly for local SMEs, to fill local equity gaps, to promote local economic development, and to rebalance the current disproportionate concentration of SME equity funding in London (highlighted in ).

In our view, notwithstanding the urgent need for more funding in the regions for transport infrastructure, for skill formation, and R&D, redressing the longstanding geographical socio-economic inequalities in the UK also requires radical levelling up of the key financial, political and governance structures that are key to economic growth. The establishment of a number of sizable, integrated financial centres in the regions, orientated to funding local business, would be an important part of this decentring. The obvious model for such a decentred federal system is Germany, where in addition to the main financial centre, Frankfurt, there are seven other regional financial centres, six of which also house stockmarkets and important clusters of venture capital firms. And of course, Germany’s sixteen Länder have a range of important fiscal, taxation and policy powers, and are able to influence national policy via the Bundesrat. A key challenge facing ‘levelling up’ the UK’s economic geography is that regional inequalities in economic, financial and political power have become deeply institutionalised in the very form of the country’s political economy, centred on London, and it will require a significant decentring of this London-based system if the UK is to shed its dubious honour of being one of the most geographically unequal countries in the OECD.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on a presentation given by Ron Martin at the Annual Conference of the Irish Branch of the Regional Studies Association in honour of Professor James Walsh, in September 2022. He wishes to thank the organisers of that conference for their invitation to give that talk, and for their perceptive comments in the discussion that followed. We are also grateful to two referees, and a number of colleagues, who made useful suggestions which helped to improve the argument.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ron Martin

Ron Martin is an Emeritus Professor of Geography at Cambridge University. His research interests include regional economic development; the resilience of regional and city economies; evolutionary economic geography; the geographies of money and spatial economic policy. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, was President of the Regional Studies Association between 2015 and 2020, and holds the Victoria Gold Medal from the Royal Geographical Society for outstanding contributions to economic geography.

Peter Sunley

Peter Sunley is Professor of Economic Geography at Southampton University. His research has focused on geographies of labour; industry clusters; social enterprise; design and creative industries; the economic evolution of cities and regions; economic resilience; local and regional economic policy and advanced manufacturing. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Science.

Notes

1 Gross Value Added (GVA) is equal to GDP + product subsidies – product taxes.

2 Like many other major UK cities, London deindustrialized rapidly over the 1970s and 1980s. Between 1971 and 1991, London saw its industrial employment (manufacturing plus construction, water and energy) decline from 1.044 million to 360,000, that is by 66 percent. This compares with a decline of 43 percent nationally. This certainly impacted negatively on London’s labour market and its public services. But, as we discuss below, unlike and in contrast to the UK’s other cities, as a global financial centre London was to benefit hugely from the Government’s financial deregulation policies in the 1980s, especially those in 1986. This gave London a new phase of (finance-based) economic growth, while other British cities were left struggling with the effects of deindustrialisation.

3 As Krugman (Citation1996, p. 41) argues, the rank size rule does not fit the UK because London is a ‘different creature’ from the rest of the urban hierarchy, being not just the UK’s largest city but also the overwhelming political, financial and cultural centre of the country.

4 The Bank of England was incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1694; Lloyds Insurance can trace its origins back to 1686; and the Stock Exchange was founded in 1698. The London Metals Exchange, another key institution of London’s financial nexus, was established in 1847.

5 In 1836, stock exchanges were established in Liverpool and Manchester during the first railway promotion boom. The second railway promotion boom of 1844–1845 was accompanied by the establishment of several more exchanges, including Glasgow, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Dundee, Belfast, Cardiff Bristol, Huddersfield, Hull, Leeds, Leicester, Newcastle, Nottingham, Sheffield, and York. The provincial stock exchanges combined into larger entities in the 1960s, and eventually amalgamated with the London Stock Exchange in 1973 (see Campbell et al., Citation2016). The British banking sector had many small local and regional banks in the mid-nineteenth century. From around 1885 until the end of World War One there was a process of increasingly larger mergers between banks. By the end of the merger wave, the English and Welsh market was highly concentrated, with only five major banks (Braggion et al., Citation2022).

6 According to Silverwood and Berry (Citation2023), the financing of investment and trade in the Empire in the 19thC, the use of the Gold Standard as part of macro-economic management in the inter-war years, as well as facilitating London’s role in the Eurodollar and Eurbond markets in the 1960s and 1970s, all testify to the way the UK state historically has chosen to promote finance capital accumulation over its industrial counterpart.

7 As Davis (Citation2022, pp. 56–84) points out, this influence or infiltration of the financial City within Government has if anything increased. Since the financial crisis of 2008, almost every senior figure who has managed Treasury economic policy has had a background in investment banking, the Stock Exchange or insurance: ‘Just as it had been normal to have Chancellors without economics or business experience for decades, now it seems normal to put investment bankers in charge' (Davis, Citation2022, p. 84).

8 These tax havens – last fragments of Britain’s lost Empire – include Anguila, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Gibraltar, Monserrat and the Turks and Caicos Islands. In addition, the Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man around the British mainland also function as part of this London-based ‘new Empire’ of financial accumulation.

9 See: ‘How London grew into a financial powerhouse’, Financial Times, 15 December 2020 (https://ig.ft.com/mapping-london-financial-centre/).

10 See Investment Association Annual Survey 2020–2021(https://www.theia.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Investment%20Management%20Survey%202021-22%20full%20report.pdf).

11 See Shaxson (Citation2018) for a revealing, and disturbing, exposé of the role of London in attracting and managing money from wealthy individuals and oligarchs from around the world, how the City of London is linked into the satellite tax havens of the Caymans and Gibraltar, how HM Treasury, the Bank of England and other banks have operated a lax attitude towards the origins and movement (and laundering) of much of that money, and the weaknesses of the whole regulatory regime that is meant to oversee all these flows into and out of London.

12 The City of London Corporation (CLC) actually predates the British Parliament, and is very different from other UK Local Authorities. It has an official (the ‘remembrancer’) installed in Parliament, facing the Speaker, and whose job it is to report back to the CLC what is going on, and to spread City infuence in Parliament. Banks, including Chinese banks, and law and accounting firms, appoint voters in its local elections.

13 See https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/229996/big-bang-20-hunt-promises-bonfire-of-city-rules.aspx

14 ‘More risk, fewer rules: the plan to revive the City of London’, Financial Times, 15 February, 2023. See https://www.ft.com/content/477318a9-5b05-4305-9e0d-f605431692db. The City Minster is a ministerial post within the Treasury, responsible fpr overseeing financial services, including the City of London itself.

15 This move to undo the regulatory system governing UK banks is in direct contrast to the argument made by Ben Bernanke (Citation2022), former Chair of the US Federal Reserve, in his December 2022 Nobel Prize lecture, in which he stresses the need for ‘strong financial regulation' in order to prevent a repeat of the Financial Crisis. (https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2022/bernanke/lecture/)

16 This is even predicted by orthodox economic theories such as endogenous growth models and ‘new economic geography’ models, as well as by heterodox cumulative causation models of regional development.

17 Earlier studies had shown there to be a convex and non-monotone relationship between the size of a country’s finance sector and the volatility of its output growth (Minsky, Citation1986; Kindleberger, Citation1978; Easterly et al., Citation2000).

18 An earlier study by Epstein and Montecino (Citation2016) estimated misallocation costs of the US finance sector over 1990–2005 to be at least $1.9trillion

19 In this respect the UK differs significantly from Germany, where the venture capital and private equity market is much more evenly distributed between regions, and where as a result there is a much more even geographical spread of equity investment into SMEs (see Klagge et al., Citation2017).

20 This lower growth trend resembles the 1 percent per year rise in GDP per head seen in the UK between 1870 and 1950, rather than the 2.3 percent gaverage growth rate between 1950 and 2007 (Wolf, Citation2015).

21 This view was echoed two decades later by the Barlow Commission, in its famous report on the geographical distribution of the nation’s industries: ‘The contribution in one area of such a large proportion of the national population as is contained in Greater London, and the attraction to the Metropolis of the best industrial, financial, commercial and general ability, represents a serious drain on the rest of the country' (Barlow, Citation1940, p. 84).

22 The UK would seem to exemplify Dow’s (Citation1999) argument that as banking has developed historically (through six stages, from pure (local) financial intermediation to (global) securitization), so financial systems have become spatially concentrated in and contolled from particular global centres which fuel the economies of their surrounding ‘core’ regions, but deprive other, ‘non-core’ or ‘peripheral’ regions of key economic resources.

References

- Adonis, A. (2021, December 8). The Short-sightedness of ‘levelling up’, Prospect.

- Ahrend, R., Farchy, E., Kaplanis, I., & Lembcke, A. (2017). What makes Cities more productive∼ agglomeration economies and the role of urban governance. OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 6, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/2ce4b893-en

- Aliber, R. Z., Kindleberger, C., & McCauley, R. N. (2001). Manias, panics and crashes: A history of financial crises (8th ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Amin, A., Massey, D., & Thrift, N. (2003). The ‘regional problem’ and the spatial grammar of British politics. Working paper, Catalyst.

- Arcand, J., Berkes, E., & Panizza, U. (2015). Too much finance? Journal of Economic Growth, 20(2), 105–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-015-9115-2

- Atkinson, R., Parker, S., & Burrows, R. (2017). Elite formation, power and space in contemporary London. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(5-6), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417717792

- Baker, A., Epstein, G., & Montecino, J. (2018). The UK’s finance curse? Costs and Processes, Sheffield: SPERI Report.

- Barlow, M. (1940). Report of the Commission on the Distribution of the Industrial Population, London: H. M. Stationary Office.

- Benigno, G., Fornaro, L., & Wolf, M. (2020). The Global Financial Resource Curse, FRB of New York Staff, Report No. 915.

- Bernanke, B. (2022). Banking, credit, and economic fluctuations. Nobel Prize in Economics Documents 2022-3. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/risnobelp/2022_5f003.htm

- Beverly, J. (1997). The Bank’s regional agencies, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, November, pp. 424-427. (Updated in Eckersley, P. and Webber, P. (2003) The Bank’s regional agencies, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, March, pp. 92-96).

- Braggion, F., Dwakasing, N., & Moore, L. (2022). Value creating mergers: British Namk consolidation, 1885-1925, Explorations in Economic History 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2021.101422

- Britton, J., Van der Erve, L., Waltmann, B., & Xu, X. (2021). London calling? Higher education, geographical mobility and early career earnings. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Cable, N. (2013). London draining life out of rest of country. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-25444981

- Campbell, G., Rogers, M., & Turner, J. D. (2016). The rise and decline of the UK's provincial stock markets, 1869–1929, Queen's University Centre for Economic History, Queen's University, Belfast.

- Cecchetti, S., & Kharroubi, E. (2012). Reassessing the impact of finance on growth, BIS Working Paper 381. https://ssrn.com/abstract = 2117753

- Cecchetti, S., & Kharroubi, E. (2015). Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth? CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP10642.

- Centre for Cities. (2015). Mapping Britain’s public finances: Where is Tax raised and where is it spent?.

- Centre for Cities. (2019, January 28). A decade of austerity, Cities Outlook 2019. https://www.centreforcities.org/reader/cities-outlook-2019/a-decade-of-austerity/

- Centre for Cities. (2020). Why big cities are crucial for ‘levelling up’. https://www.centreforcities.org/reader/why-big-cities-are-crucial-to-levelling-up/

- Champion, T. (2019). How many extra people should London be planning fro/. Geography (Sheffield, England), 104(3), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2019.12094080

- Champion, T., & Gordon, I. (2019). Linking spatial and social mobility: Is London's “escalator” as strong as it was? Population, Space and Place, 27. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2306

- Christensen, J., Shaxson, N., & Wigan, D. (2016). The finance curse: Britain and the world economy. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115612793

- City of London Corporation. (2014). London’s finances and revenues, Research Report, London: City of London Corporation.

- Clegg, N. (2010, June 29). Fair shares. The Northern Echo. http://www.theNorthernecho.co.uk/features/leader/8244486.Fair_shares/

- Coffey, D., Thornley, C., & Tomlinson, P. (2022). Industrial policy, productivity and place: London as a ‘role model’ and high speed 2 (HS2). Regional Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2110226

- Collier, P. (2018a, October 12). How to save Britain from London, Prospect.

- Collier, P. (2018b). The future of capitalism: Facing the new anxieties. Allen Lane.

- Combes, P.-P., Duranton, G., Gobillon, L., Puga, D., & Roux, S. (2012). The productivity advantages of large cities: Distinguishing agglomeration from firm selection. Econometrica, 80(6), 2543–2594. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA8442

- Crafts, N. (2005). Regional GDP in Britain, 1871-1911: Some estimates. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 52(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0036-9292.2005.00334.x

- Cunningham, N., & Savage, M. (2017). An intensifying and elite city. City, 21(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1263490

- Davis, A. (2022). Bankruptcy, bubbles and bailouts: The inside history of the treasury since 1976. Manchester University Press.

- Deutsche Bank. (2013). London and the UK Economy: In for a Penny, In for a Pound, Special Report, Deutsch Bank Markets Research. London.

- Dow, S. (1999). Stages of banking development and the spatial evolution of the financial system. In R. Martin (Ed.), Money and the space economy (pp. 31–48). John Wiley.

- Eagleton-Pierce, M. (2023). Uncovering the City of London corporation: Territory and temporalities in the new state capitalism. Enivironment and Planning, A: Economy and Space, 55, 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221083986.

- Easterly, W., Islam, R., & Stiglitz, J. (2000). Explaining growth volatility, World Bank Report 28159.

- Epstein, G., & Montecino, J. (2016). Overcharged: The high cost of finance. The Roosevelt Institute.

- Fernandez, R., Hofman, A., & Aalbers, M. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(12), 2443–2461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16659479

- Financial Times. (2020, December 15). How London grew into a financial powerhouse, Financial Times. https://ig.ft.com/mapping-london-financial-centre/

- Financial Times. (2023, February 15). More risk, fewer rules: The plan to revive the City of London. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/477318a9-5b05-4305-9e0d-f605431692db

- Garcia-Bernardo, J., Fichtner, J., Frank, W., Takes, F., & Heemskerk, E. (2017). Uncovering offshore financial centers: Conduits and sinks in the global corporate ownership network, Scientific Reports 7: 6246 | doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9.

- Geary, F., & Stark, T. (2016). What happened to regional inequality in Britain in the twentieth century? The Economic History Review, 69(1), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12114

- Gieve, J. (2007). The city’s growth: The crest of a wave or swimming with the stream. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Q2, 286–290. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2007/quarterly-bulletin-2007-q2.pdf

- Glaeser, E., Ed. (2010). Agglomeration economics. University of Chicago Press.

- Glaeser, E. (2011). Triumph of the city. Macmillan.

- Gordon, I. (2016). Quantitative easing of an international financial centre: How central London came so well out of the post-2007 crisis. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(2), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsw012

- Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018). The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- Greater London Authority. (2016). London: The global powerhouse. GLA.

- Greater London Authority. (2019). London and the UK: A declaration of interdependence. GLA.

- Greater London Authority. (2020). The evidence base for London’s Local Industrial Strategy – Final Report, London: GLA.

- Green, J. (2018). The offshore city, Chinese finance, and British capitalism: Geo-economic rebalancing under the coalition government. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(2), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117737263

- H.M. Government. (2022). Levelling up the United Kingdom. GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- H.M.Treasury. (2021). A new chapter for financial services. OGL London.

- Hall, P. (1962). The industries of London. Routledge.

- House of Commons Library. (2014). Privatisation, Research Paper 14/61, House of Commons Library, London. https://www.economist.com/bagehots-notebook/2017/02/23/the-pragmatic-case-for-moving-britains-capital-to-manchester

- Huggins, R., & Prokop, D. (2014). Stock markets and economic development: The case for regional exchanges. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 5(3), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2013.059870

- Hutton, G. (2022). Financial services: Contribution to the UK economy. House of Commons Library 6193.

- James, S., Kassim, H., & Warren, T. (2021). From Big Bang to Brexit: The City of London and the discursive power of finance. Political Studies, 70(3), 719–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720985714

- Johnson, B. (2009, October 6). Speech to the Conservative Party Annual Conference, Manchester. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2009/06/oct/michael-white-conservative-conference-diary/

- Johnson, B. (2012, April 30). Interview with the Huffington Post. Job Creation Should Be The Mayor's Top Priority, Concludes LinkedIn Poll | HuffPost UK Politics (huffingtonpost.co.uk).

- Johnson, B. (2020, June 30). New Deal for Britain Speech. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-a-new-deal-for-britain

- Kaminska, I. (2016). Brexit and Dutch Disease. Financial Times. https://ftalphaville ft.com/2016/10/12/2177179/brexit-and-britains-dutch-disease/

- Keynes, J. M. (1926). The End of Laissez-Faire. The Hogarth Press.

- Kindleberger, C. (1978). Manias, panics and crashes: A history of financial crises. Basic Books.

- Klagge, B., Martin, R. L., & Sunley, P. (2017). The spatial structure of the financial system and the funding of regional business: A comparison of Britain and Germany. In R. L. Martin & J. Pollard (Eds.), Handbook on the geographies of money and finance (pp. 125–155). Edward Elgar.

- Kollydas, K., & Green, A. (2022). Graduate pathways: identifying patterns of regional retention and attraction, Report, University of Birmingham.

- Krugman, P. (1996). The self-organising economy. MIT Press.

- Lee, S. (2018). The developmental state in England: The role of the treasury in industrial policy. In C. Berry, J. Froud, & T. Barker (Eds.), The political economy of industrial strategy in the UK (pp. 39–50). Agenda.

- London and Partners. (2022). 2021: The Year London tech reached new heights, dealroom.co, London tech set to reach new heights in 2022 following record year for VC investment (londonandpartners.com)

- Mackinder, H. (1919). Democratic ideals and reality: A study in the politics of reconstruction. H Holt.

- Martin, R. L. (1994). Stateless monies, global financial integration and national economic autonomy: The end of geography. In S. Corbridge, N. Thrift, & R. Martin (Eds.), Money, power and space (pp. 152–176). Blackwell.

- Martin, R. L. (1999). Selling off the state: Privatisation, the equity market, and the geographies of shareholder capitalism. In R. L. Martin (Ed.), Money and the space economy (pp. 261–283). John Wiley.

- Martin, R. L. (2013). London’s economy: From resurgence to recession to rebalancing. In M. Tewdwr-Jones, N. Phelps, & R. Freestone (Eds.), The planning imagination: Peter Hall and the study of urban and regional planning (pp. 67–84). Routledge.

- Martin, R. L., Gardiner, B., Pike, A., Sunley, P. J., & Tyler, P. (2021). Levelling up left behind places: The scale and nature of the economic and policy challenge. Taylor and Francis.

- Martin, R. L., Gardiner, B., Pike, A., Sunley, P. J., & Tyler, P. (2022). Levelling up the UK: Reinforcing the policy agenda. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 794–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2022.2150562

- Martin, R. L., & Minns, R. (1995). Undermining the financial base of regions: The spatial structure and implications of the UK pension funnd system. Regional Studies, 29(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409512331348853

- Martin, R. L., & Sunley, P. (2023). Is London’s productivity slowdown changing the UK’s Regional Problem? https://www.regionalstudies.org/news/blog2023is-londons-productivity-slowdown-changing-the-uks-regional-problem/

- Massey, D. (2013). The ills of financial dominance, Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/ills-of-financial-dominance/

- McCann, P. (2016). The UK regional-national economic problem. Routledge.

- Minsky, H. P. (1986). Stabilizing an unstable economy. Yale University Press.

- National Audit Office. (2011). The financial stability interventions. NAO.

- Neate, R. (2021, February 24). London has more Dollar Millionaires than New York, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/24/london-dollar-millionaires-new-york-covid-crisis-assets-wealth

- OECD. (2020). Cities and regions at a glance – Country Note - the United Kingdom OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2022 | en | OECD.

- Office for National Statistics. (2021). International trade by subnational areas of the UK, 2019. ONS.

- Overman, H. (2011). How did London get away with it? Centrepiece 333, London School of Economics. https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cp333.pdf

- Overman, H., & Rice, P. (2008). Resurgent cities and regional economic performance. SERC Policy Paper 1, London School of Economics.

- Roberts, R. (2018). London: Downturn, recovery and new challenges – But still pre-eminent. In Y. Cassis & D. Wojcik (Eds.), International financial cebtres after the global financial crisid and brexit (pp. 37–60). Academic Press.

- Rowthorn, R. E. (2010). Combined and unven development. Spatial Economic Analysis, 5(4), 363–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2010.516445

- Rubinstein, W. (1977). The victorian middle classes: Wealth, occupation and geography. The Economic History Review, 30(4), 602–623. https://doi.org/10.2307/2596009

- Shaxson, S. (2018). The finance curse: How global finance is making us all poorer. The Bodley Head.

- Silverwood, J., & Berry, C. (2023). The distinctiveness of state capitalism in Britain: Market-making, industrial policy and economic space. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 55(1), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221102960

- Stansbury, A., Turner, D., & Balls, E. (2023). Tackling the UK’s regional inequality: Binding constraints and avenues for policy intervention, Working Paper, MIT.

- Swinney, P., & Williams, M. (2016). The great British brain drain: Where graduates move and why. Centre for Cities.

- Tetlow, G. (2017, May 17). New figures show how London and the South subsidize the UK, Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/6ebd5350-3f8f-11e7-9d56-25f963e998b2

- The Economist. (2017). The pragmatic case for moving London to Manchester.

- Thirlwall, A. (1980). Regional problems are ‘balance-of-payments’ problems. Regional Studies, 14(5), 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595238000185371

- Tőpfer, L.-M., & Hall, S. (2018). London’s rise as an offshore RMB financial centre: State-finance relations and selective institutional adaptation. Regional Studies, 52(8), 1053–1064. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1275538

- Wilson, N., Kacer, M., & Wright, M. (2019). Equity Finance and the UK Regions: Understanding regional variations in the supply and demand of equity and growth finance for Business, BEIS Research Paper 2019/12, London: Department of Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy.

- Wolf, M. (2015). The shifts and the shocks: What we have learned and have still to learn from the financial crisis. Penguin.

- Wolf, M. (2023). The UK economy has two regional problems, not one, Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5b1c5cc4-6961-4bbc-9132-ac6472796395