ABSTRACT

The closure of the Australian passenger vehicle industry in 2017 ended an important phase in the nation’s economic history. Closure affected up to 100,000 employees working across the Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and the supply chain, with the impacts concentrated in two Australian states. This paper examines both the processes and the outcomes of this closure, making use of a Just Transitions lens to assess the wider impacts of this change. It reviews the measures put in place to assist workers displaced by plant closure, while also drawing on three waves of data from a survey of retrenched workers. The paper argues the process of transition for former employees was shaped by the distinctive characteristics of Australia’s system of industrial relations and the ambition of its governments to have as many affected workers find employment as possible. This objective was prioritised over quality of employment or the emerging skill needs of industries. The paper finds that while former auto workers have been able to re-establish themselves in the labour market, the management of this major change does not meet the expectations of a Just Transition as too little attention was directed to the wider societal impacts of this transformation.

Introduction

The first announcements that constituted the closure of the automotive passenger industry in Australia took place more than a decade ago in May 2013 and emerged in the context of a globally changing car industry (Bailey et al., Citation2010), a relatively strong Australian currency and shifting priorities amongst global car makers as the industry faced substantial challenges (Beer, Citation2018). The withdrawal of subsidies and tariff protections also played some part, albeit a relatively small role. Parts of the Australian passenger vehicle industry had shut down previously, with Mitsubishi Motors Australia Limited the most recent exit, having closed its Lonsdale facility in 2004 and Tonsley assembly plant in 2008. The impacts of industry-wide shutdown were most acutely felt in Melbourne (including Geelong) and Adelaide where the Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and their supply chains were concentrated.

The closure of the industry carried with it the potential for substantial long-term impacts, given localised labour markets are especially vulnerable to long-term impacts from large-scale layoffs (Celli et al., Citation2023). Economic shifts in response to both technological and environmental change, characteristic of doing local business in a global economy, also bring complex social impacts. Australia’s automotive industry closure occurred within a policy environment increasingly focussed on the question of a Just Transition for workers, communities and industries affected by the shift away from fossil fuels. The shutdown of Australia’s car industry, although not explicitly driven by transition to a low-carbon economy, can therefore offer insights into the management of this kind of change. This paper addresses this potential by being the first to analyse events in the automotive industry from the perspective of a Just Transition.

Although the just transition movement originally sought to protect vulnerable communities from economic hardship brought about by the environmental regulation of industry, and the resulting mass job losses, it has evolved since the 1990s to encompass a range of concepts from justice movements. While much climate change discussion and research has focused on the scientific aspect of the crisis, Just Transition advocates for attention to the profound social impacts of transition and the even distribution of its impacts and benefits (Wang & Lo, Citation2021). However, the concept is not understood or applied homogenously – it has evolved over time, becoming international, and contains political tensions. It is to be expected that the car industry globally will endure further shocks as electric vehicle production increases, and that other communities, especially those tied to the production of fossil fuels, will experience wholesale transition at a regional scale similar to that experienced by Australia’s outer-urban automotive manufacturing communities. Whether a just transition has been achieved for Australia’s former automotive workers is therefore a salient question, but one that presents many dimensions of enquiry.

This paper addresses that complexity by reporting on the outcomes of an Australian Research Council Linkage Project on the impact of the closure of the car industry in Australia. It makes use of four forms of primary data collected over three years (Beer et al., Citation2019): a survey of affected workers employed by the OEMs and firms in the supply chain; qualitative in-depth interviews with a smaller group of respondents; a survey of impacted communities (Beer et al., Citation2023); and a Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE) on the preferences of affected workers for future employment and training. Elements of this work are yet to be completed, but substantial progress has been made on all major components of the project.

To date, key findings have illuminated the economic vulnerabilities of workers who exited the car industry, especially through the further shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, but showed that labour market outcomes following the closure were decidedly more positive (Irving et al., Citation2022) than those following the closure of Mitsubishi’s Lonsdale plant (Beer et al., Citation2006). They have also shown a clear perception in communities surrounding the closed plants that the Australian Government, state governments and the auto industry had not met their expectations around leadership in a time of turmoil (Beer et al., Citation2023).

The remainder of this paper discusses Just Transitions as a concept able to shed a broader perspective on questions of fundamental change in local economies. The analysis is then divided into two parts. The first considers the impacts of the policy environment surrounding the end of Australia’s passenger vehicle industry, particularly as it related to the assistance given to workers to prepare for the post-closure labour market. The second considers a selection of labour market outcomes from three waves of survey data. We then discuss the relationship between those policy intentions and their real-world outcomes, with a view to understanding how well workers were protected from the negative effects of this significant industrial transformation.

Just transitions

Just Transitions is a multi-faceted concept with its roots in the labour movement. As several researchers have argued (Newsome, Citation2015; Rainnie et al., Citation2011), globalisation and other changes in the economic structure of advanced economies has resulted in significant disruption to both individual workers and entire communities. In Australia and elsewhere (ACTU, nd; Normann & Tellman, Citation2021) labour organisations and others have attempted to develop a narrative of positive change through advocacy for a Just Transition, a concept drawn from the experience of unions in the USA in industries facing environmental regulation, and its later application to the coal industry in Germany, where unions, governments and industry worked together for more than a decade to plan for closure. In Australia the concept of a Just Transitions fills an important gap for labour unions: historically unions have represented their members up until the point at which they have left the industry – which has meant workers forced out of employment by plant closure have lost access to a political, social and economic support network previously forming a central pillar of their lives.

Debate around Just Transitions has developed rapidly over the past two decades, with many authors now emphasising the pressing issues of climate change and environmental justice (Healy & Barry, Citation2017; Heffron & McCauley, Citation2018). In linking the causes of climate change – extractive capitalism and unsustainable growth – to the political and social causes of inequity, it argues for the climate crisis as an opportunity for systemic reform, resulting in greater social justice and a regenerative economy. Wang and Lo (Citation2021) identified five major strands within this literature, Just Transitions as a concept focussed on: labour market change; integrated justice; socio-technical transition; governance; and public perception. Within this body of work, some researchers have been careful to draw attention to the economic and labour market implications of change and the role of governments in shaping outcomes (Routledge et al., Citation2018). While and Eadson (Citation2022) highlighted the risk of a shift to a low carbon economy further entrenching spatial divisions of labour, arguing it is important for Just Transitions to include a focus on ‘skills, training and pathways to employment across supply chains’ (p. 385). They discussed the key mediating role of governments with respect to decarbonisation, observing that:

… quantifying future economic and employment impacts of decarbonisation is difficult because much will depend on choices made by governments and how to decarbonise, over what time scales, the balance of economic and legislative instruments and the extent to which there are shared international frameworks (While & Eadson, Citation2022, p. 389).

Healy and Barry (Citation2017, p. 424) observed ‘the concept of a just transition has been left relatively open to multiple interpretations’, broadening to include both those in the formal workforce and those outside it, while also paying attention to community wellbeing. Wang and Lo (Citation2021) suggested that debates about what constitutes a just transition, specifically the tension between environmental and economic concerns, pose significant governance issues. Many scholars have emphasised the need for coalitions, alliances and community engagement to achieve just transition. However, this fluidity and ambiguity has been identified by Snell (Citation2018) as a core strength of the concept, who argued the conceptual breadth of Just Transitions and absence of hard boundaries allows it to serve as an important point of departure for conversations around change between a wide range of stakeholders. This plasticity is of value given the politically charged nature of Just Transitions debates (Newell & Mulvaney, Citation2013; Routledge et al., Citation2018), but it serves as more than just a starting point for conversations. Snell (Citation2018) noted that it provides an ideal to which those managing change should aspire, embodying elements of inclusion, justice, and wholesale transformation to an equitable and sustainable economy.

The literature on Just Transitions has established a set of aspirations for workers and communities affected by the global shift from fossil fuels (e.g. ILO, Citation2015) to sustainable alternatives. As part of that goal setting, there is an explicit commitment to ensure that communities that have depended on fossil fuels and their use do not bear a disproportionate share of the costs of change, as well as being placed to share fairly in its benefits. This means affected workers and the localities in which they live and work need assistance in finding sustainable alternative livelihoods (Johnstone & Hielscher, Citation2017). Rainnie et al. (Citation2019) argued scholarship into Just Transitions has identified six core principles that should inform all action. There needs to be a sense of: distributional justice; procedural justice; restorative justice for harms done in the past; an acknowledgement of local values and the need to include all within the community; spatial sensitivity; and the need to match long- and short- term actions to the pace at which change is occurring. Similarly, Pai et al. (Citation2020) produced a systematic review of the literature and identified 18 elements within four clusters that should inform the design and implementation of a Just Transition ().

Table 1. Elements of Just Transition.

Just Transitions is both a ‘call for action’ to address climate change, and a set of aspirations focussed on the experiences of workers and communities affected by this profound industrial change. It is more ambitious than conventional policy settings that address the impact of industry change, including plant closures, in that the remit for policy action extends beyond the simple redeployment of retrenched workers to embrace questions of social cohesion, the viability of regional economies and better public sector programmes. Other work into structural adjustment in advanced economies has raised similar ideas, albeit with a lesser focus on community impacts and the conscious development of whole new industries. Rainnie et al. (Citation2019) suggested successful closure management should:

focus on place – In localities undergoing transformation, individuals and enterprises have a sense of belonging and inclusion.

focus on governance – Local decision making is critical to achieving the aspirations of a successful closure.

offer a unified vision for the future – A clear vision and a set of goals, targets and strategies for turning the vision into reality.

engage with local institutions – Dialogue between local institutions that builds trust and creates a ‘democratic dividend’ to advance the closure process.

emphasise help for affected individuals – Targeting assistance to those individuals and groups for whom the closure process will be most challenging.

focus on the local capture of value – It is not enough to attract new enterprises; long-term sustainability requires the local capture of value, so that the wealth ‘sticks’ in the region.

consider transformation over multiple time frames – A view of transformation that is attentive to the relations among short-, medium- and long-term responses and outcomes.

acknowledge the emotional element of closure processes – Communities need to have the opportunity to give voice to their feelings and perspectives on the closure process.

Similarly, Bailey et al. (Citation2014) concluded public policy responses to plant closures must be: (1) multidimensional in that they transcend narrow sector-based concerns and address broader spatial impacts; (2) inclusive in that they build on a broad coalition of economic and social stakeholders; and (3) long-term in that they acknowledge that adaptation takes many years.

There is a more recent body of work on just transitions for the automotive industry and similar carbon-intensive sectors. Beale (Citation2024) concluded from her examination of the impacts of the closure of the Australian car industry that just transition remains an important guiding principle for governments and communities in face of a restricting economy. She also argued for the need for programmes of extended duration, as the most pressing challenges for workers made redundant are unlikely to appear within the first two years. Pichler et al. (Citation2021) examined the Austrian automotive sector and its capacity to adjust to a decarbonised world, paying particular attention to the capacities of the labour force. From their interviews with workers, trade union officials, work council members and employers, they identified three major narratives of change (Beer et al., Citation2021), improvement, diversification and transformation. On that basis, they concluded the Austrian vehicle industry was well placed to move into a decarbonised future, largely because of the adaptability of its workforce and other industry participants. The critical role of trade unions in enabling a just transition was also emphasised by Galgóczi’s (Citation2020) analysis of change in the coal and automotive industry across Europe. Krzywdzinski (Citation2020) used a mixed methods approach to consider change in Germany’s automotive industry and concluded that while transition to a low carbon future may potentially benefit some suppliers and the industry as a whole, outcomes were likely to be highly differentiated across the elements of the production process, and the regional impacts are likely to be unequal. Dall-Orsoletta et al. (Citation2022) noted the transition to the production and consumption oof electric vehicles created a broad spectrum of challenges to a just transition, including the potentially adverse impacts on communities unable to afford these new technologies and associated infrastructure.

As we can see, all these approaches contain significant overlap with the clustered elements identified by Pai et al. (Citation2020) in Just Transitions. They are future-oriented and inclusive, while also encompassing a strong community element and a focus on managing change at an appropriate scale. They acknowledge critical stakeholders, ascribing a critical role to governments as well as the community and industry. However, the degree to which they reflect established practice for managing change in real-world closure settings is varied and longer-term impacts are only partially understood (Celli et al., Citation2023). We therefore turn to the data to assess how well the experience of Australia’s former automotive workers stood up to these aspirations.

Automotive industry closure in Australia: a just transition?

Transition programmes and structural adjustment

The announcement of the closure of the passenger vehicle manufacturing sector in Australia was accompanied by a series of commitments by governments and industry to the establishment of ‘industry leading’ responses to shutdown (Dinmore & Beer, Citation2022). In part this reflected the magnitude of the announcements and their political and economic consequences, but it also reflected the regulatory environment and the reality that automotive firms had received considerable financial support from Australian governments over many decades (Beer & Thomas, Citation2007).

Actions taken in response to the impending shutdowns occurred across four dimensions: first, the delivery to affected workers of pre-closure information, counselling and job search preparation; second, the careful management of the closures as events – with major celebrations organised for some high-profile shutdowns; third, the provision of post-closure job search and retraining assistance for affected workers from OEMs and supply chain firms; and, finally, the implementation of local regional development initiatives aimed at finding new economic opportunities in the communities affected by change (Beer et al., Citation2021). These measures were co-ordinated by governments but partly funded by lump sum contributions from the major auto firms.

Programmes introduced by governments to assist displaced workers were evaluated as successful in reducing worker anxiety and the negative emotional effects of job loss (DIIS, Citation2020). Workers were provided with extensive career advice, training options and job placement assistance. These programmes were not always successful in assisting workers find new jobs, but they offered a sense of procedural justice, leaving them with the understanding that everything that could have been done to help, had been done (Barnes & Weller, Citation2020). To complement individual interventions, governments invested in the generation of job opportunities and developed a strategy for linking the skills of retrenched workers to the skills required in newly created jobs (Fairbrother et al., Citation2013). In the most affected locations, Geelong and Adelaide, governments provided funds to help supply chain firms diversify and attract new investment. In both locations, governments invested heavily in infrastructure to stimulate employment (Tierney et al., Citation2023).

ACIL Allen Consulting (Citation2019) evaluated the workforce transition programmes attached to the shutdown of the passenger vehicle industry in Australia. It found that collaboration between each of the leading companies, relevant government departments, and supply chain companies resulted in the successful deployment of retrenched workers into other jobs, ongoing study or retirement. Success was evaluated according to worker satisfaction with the process, rather than as a result of an objective assessment of circumstances before and after retrenchment – a form of procedural justice. This achievement was attributed to:

The early notification of plant closures (see ), which gave stakeholders time to design and develop intervention strategies and a range of support initiatives;

The provision of a range of flexible, individually tailored and compassionately delivered employment, health and wellbeing and financial support programmes;

The establishment of transition hubs (one-stop-shop information centres) at which employees could access a range of services; and,

The close collaboration of all stakeholders throughout the closure process.

Table 2. Timeline of the Australian automotive closures.

A number of reports echoed the narrative of success evident in the ACIL Allen report, but such assessments were largely undertaken soon after the shutdowns; tended to focus on processes and policy directions rather than outcomes; took place within a complex environment in which a large number of labour market interventions were implemented simultaneously; and, were unable to anticipate the impact of a global pandemic and its impact on affected workers, their families and communities. The next section uses longitudinal data on labour market outcomes over the period 2020–2022 to provide evidence on how those made redundant have fared in the labour market and financially.

More critical assessments were made of government actions and their ability to move beyond the workforce and address community concerns. Beer et al. (Citation2023) reported on the outcomes of a survey of the communities most affected by the shutdown of Australia’s automotive industry. When residents were asked to assess the performance of those charged with leading this process change, they indicated that the car manufacturers and central governments (the Australian Government and the state governments of Victoria and South Australia) performed most poorly, and gave the most favourable evaluations to leaders from the social services sector who played a visible role in delivering support to those in need of assistance. Clearly, the ambition embedded within the Just Transitions literature focussed on addressing community impacts was not met in this instance.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the impact of COVID-19 on the labour market experiences of those made redundant with the closure of car manufacturing in Australia. Australia’s car industry was heavily concentrated in the states of Victoria and South Australia, and while the latter was relatively unaffected by COVID, Victoria felt significant impacts. The state capital, Melbourne, endured 512 days of lockdown, with tight restrictions on travel, shopping and the ability to go to work. The Australian Government’s Job Keeper programme provided a guaranteed income for those employed on an ongoing basis, but others in less secure labour market positions received little support. Those looking for work, working part time, or employed under less formal arrangements, suffered significant disadvantage as they lost the ability to earn an income. A significant percentage of former automotive workers were vulnerable under these circumstances, having lost the security of full time, ongoing work, and being re-engaged on the very fringes of the labour market. Post 2021 they have benefited from an economy that has grown sharply, with interest rates at record lows and unemployment rates falling to levels not experienced in Australia since the early 1970s. However, a muted economic rebound in the wake of COVID-19 would have left this group of employees at risk, still at the fringes of the labour market, and without substantial recent experience or networks to assist their job search.

Three years of insight into labour market outcomes

As the earlier discussion has outlined, a Just Transitions represents an ideal to aspire to in managing large scale economic shock, including the closure of entire industries. This section uses the insights from three waves of surveys to evaluate the outcomes associated with the closure of the Australian passenger vehicle industry. It considers the labour market outcomes for workers from the OEMs and supply chain firms over the three years from 2020 to 2022. The survey consisted of a range of questions, with some questions asked each year, while other data were collected for a single year only, or occasionally. This has allowed for a longer-term perspective on key outcome measures – such as labour force status – while also permitting a wider array of issues to be addressed.

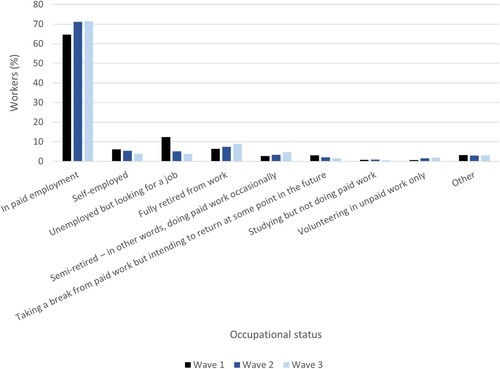

Labour force status is one of the key metrics governments and the community look at in the wake of an economic shock and the results for retrenched workers for the period 2020–2022 are shown in below. Overall, the results have been positive, with an increasing number of respondents in paid employment or formally retired, with associated declines in those unemployed and looking for work, those temporarily withdrawn from the labour market, as well as those studying and not engaged in paid work.

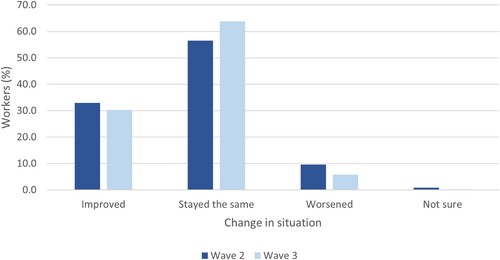

Additional data on employment change between each wave of data collection shows respondents were most likely to report their job circumstances had not changed, but those who did experience a change were more likely to experience an improvement in their situation rather than a reversal ().

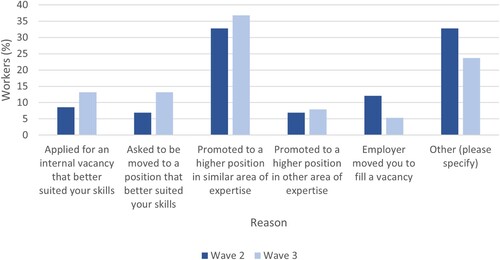

For many, this change was a promotion, while other moves were linked to the individual seeking a better match between their skills/experience and their current employment (). These outcomes are important because they speak to both the agency of the individuals in seeking out better opportunities for themselves, and also the process of adjustment that occurs once a displaced worker finds new employment. Workers may enter a firm at a lower level or in a less skilled position but are then able to reposition themselves as they gain experience in the new enterprise.

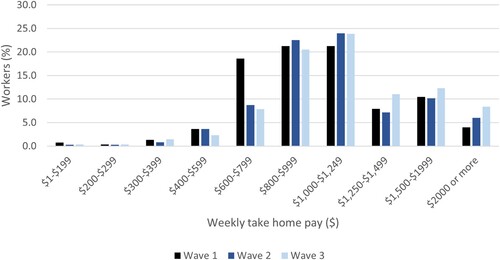

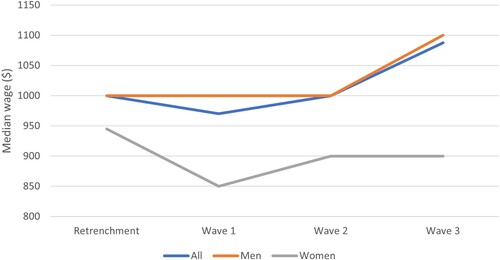

Average wages rose over the three waves of data collection () and there was a significant shift in the percentage of workers earning less than average weekly earnings ($1,000 to $1,249 per week) towards wages above the national median. For example, the percentage of workers earning more than $2,000 per week rose from four per cent to 8.4 per cent. Once again, the wages data speak to the adjustment of workers over time as they re-established themselves and took advantage of improving economic conditions. Overall, 315 interviewees reported their incomes had increased over the three years, while 87 reported a decline in their income, while 50 individuals reported no change at all.

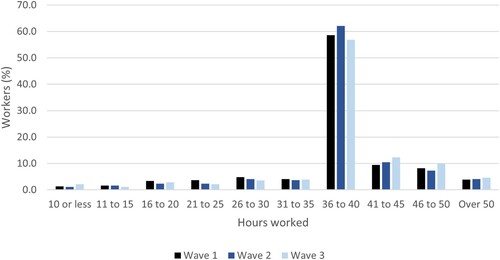

Across the three waves of the survey self-reported incomes rose, in part, because of an increase in the number of hours worked (). However, the increase in hours worked was not as substantial as the increase in wages, with the majority of respondents reporting their hours remained stable over the three years (200 respondents), while 182 indicated their hours increased and 139 noted their hours worked fell over the three-year period.

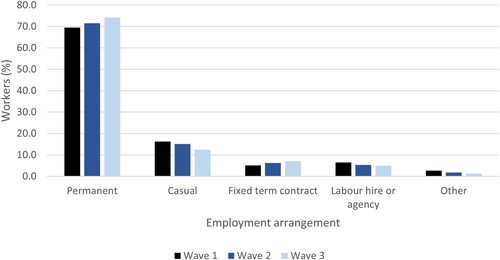

Data on security of employment for former auto workers presents an equally positive set of outcomes () with more than 70 per cent engaged permanently by Wave 3, and a further seven per cent on fixed term contracts. The percentage of staff employed on casual contracts fell from 16 per cent in 2020–12.1 per cent by 2022 and – unlike earlier plant closures – very few workers were engaged through labour hire firms (Irving et al., Citation2022).

Of the 453 respondents for whom three waves of data are available, some 322 were in secure forms of employment at Wave 1 and remained in secure work over the subsequent waves. Only 16 respondents moved to insecure forms of employment. A further 91 respondents were engaged in insecure work at the start of the longitudinal survey and remained in more tenuous forms of employment. Just 24 of the insecure employed moved to more stable and secure forms of employment over the subsequent waves. Overall, these data suggest a form of ‘lock in’ with respect to labour market outcomes, with former automotive employees either unable to find or move to more secure forms of work, or unwilling to take on a more substantial work commitment.

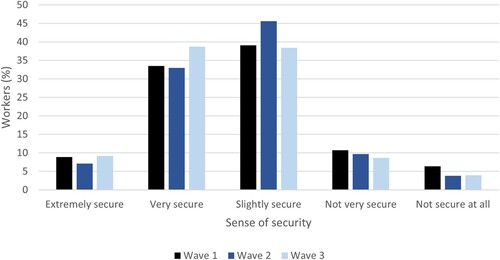

Survey respondents were not solely asked about the nature of their employment arrangement, they were also asked about their perceived security in their place of work. As illustrates, most retrenched workers felt their current employment was secure, and this had increased over time. Across the 457 respondents for whom three waves of data is available, 219 reported no change in their perceived security of tenure, 178 felt they had become more secure over time and 77 had a sense that their employment security had declined.

Figure 7. Sense of security in main job, three waves.

Note: Wave 1 n = 824; Wave 2 n = 631; Wave 3 n = 550.

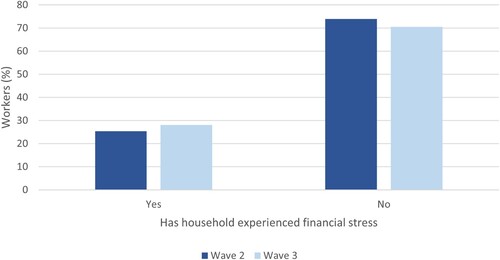

Employment remains an important indicator of outcomes associated with labour market change, but it may give a false impression if full time employment has been replaced by a job with fewer working hours or a lower hourly rate of pay. The second and third survey waves included a question on financial stress resulting from redundancy in the automotive industry and as shows, the incidence of financial stress increased between 2021 and 2022 despite improving employment rates.

Figure 8. Incidence of financial stress as a result of leaving the auto industry, Waves 2 and 3.

Note: Wave 2 n = 886; Wave 3 n = 783.

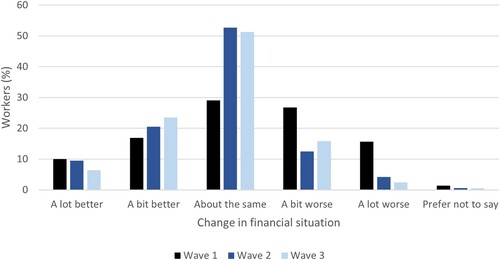

It is important to acknowledge, however, that the majority of respondents reported they were not financially stressed. It is likely the financial pressures experienced by some households may be a product of economy-wide changes – including escalating housing costs and general inflation – rather than labour-force specific processes. Further insights into the financial vulnerability of affected workers were obtained by asking respondents about their changing financial circumstances (). It is clear that, for the population of respondents as a whole, 2020 saw a significant worsening of finances when compared with the period working in the auto industry, while 2021 resulted in a significant upturn and 2022 brought modest improvements for some households, and a slight decline for others.

Figure 9. Change in financial situation since interviewed/leaving auto-industry, by year.

Note: Wave 1 n = 1265; Wave 2 n = 886; Wave 3 n = 783.

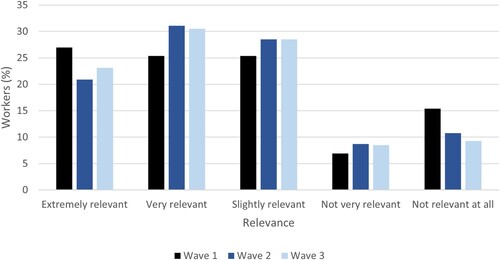

The literature on Just Transitions prioritises the quality of work available to those affected by industrial change. Quality, of course, has a number of dimensions including security of employment, pay rates and the capacity to work the desired number of hours. It also includes the sense of wellbeing associated with the capacity to redeploy existing skills and knowledge sets, as well as overall satisfaction with the new place of work and its culture. Workers made redundant from the Australian passenger vehicle industry reported mixed outcomes with respect to their capacity to apply their skills to their new place of employment (). At Wave 3, 45 per cent of respondents reported that their knowledge and abilities were either slightly relevant, not very relevant or not relevant at all to their new job. Moreover, the data suggest some workers found the match between their pre-existing skills and their new employment declined over time, especially amongst those who reported a very close fit at the first wave of data collection. Amongst the respondents for whom three waves of responses are available, 238 of the 474 respondents indicated that the relevance of their knowledge and skills obtained in the auto industry remained the same, 118 indicated that the match strengthened over time and a further 118 responded that their previous experience and abilities became less relevant.

Figure 10. Relevance of knowledge and skills from the auto industry, repeat cross-sectional.

Note: Wave 1 n = 824; Wave 2 n = 631; Wave 3 n = 550.

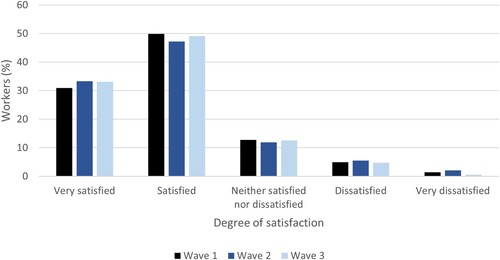

Figure 11. Job satisfaction with new employer, three waves.

Note: Wave 1 n = 824; Wave 2 n = 631; Wave 3 n = 550.

At the same time, most former automotive workers in employment were satisfied or very satisfied with their new job, with 60 per cent reporting no change in their level of satisfaction across the three waves, with those more satisfied over time, and less satisfied over time approximately equal at 20 per cent. The degree to which employees are satisfied with their new employment is significant, but it is more critical to understand how this compares with their former role in the car industry. A significant percentage of those re-deployed were less satisfied with their new employment when compared with their previous job, such that some 32 per cent of respondents were still either less satisfied or much less satisfied at Wave 3. At the same time, 34 per cent were more satisfied or much more satisfied in the 2022 data collection, and overall satisfaction with the new job increased over time, with 110 of the 474 respondents for whom three waves of data are available indicating that they became less satisfied over time while 146 reported they became more satisfied over time ().

As Weller et al. (Citation2020) acknowledged, the gender dimensions of economic transformation are both important and often under reported. The closure of the Australian car industry appears to have exacerbated – already strong – gender inequities (). Female median wages were substantially lower than wages paid to males within the automotive sector and this gap has widened over the intervening period. Male median wages rose by $100 per week from redundancy to Wave 3, while female median wages decreased by $45. Expressed another way, the weekly wages of women fell from 95 per cent of the male wage to 82 per cent.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper sets out to better understand the labour market impacts of the shutdown of the Australian passenger vehicle industry. At a conceptual level it has drawn on the ideal of a Just Transitions to serve as a standard against which the management of major economic change should be assessed. Empirically it has made use of three waves of survey data from a research project supported by the Australian Research Council that has examined the impact of the closure of the automotive industry. Overall, the analysis of labour market outcomes for those made redundant when Australia’s car industry closed is predominantly positive. The data shows high levels of employment in Waves 2 and 3; high levels of re-employment in ongoing roles; a high perception of job security; access to a substantial number of hours of employment; few staff employed casually or through a labour hire firm; and wages broadly equal to those available in the car manufacturing sector or better. Importantly, the majority of these indicators of labour market success improved over the three years from 2020 to 2022 as the Australian economy rebounded from the shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and as workers became established in their new positions.

The strengths evident at Wave 3 in the labour market outcomes of those made redundant from the Australian car making industry may give a falsely optimistic perspective on how this transition was managed. When judged against the aspirations set out in the Just Transitions literature, significant shortcomings emerge. For example, not all dimensions of the analysis present a positive picture of resilience in the face of change. We cannot overlook the fact that too many of the respondents to this survey were unemployed or in a difficult financial position in 2020 when the impacts of lockdowns and pandemic were most acute. Three years after the last operating automotive assembly plant closed many workers remained in circumstances that made them vulnerable to further shocks, of which COVID-19 was an example. This resulted in financial distress, lower levels of satisfaction with their place of employment and lower average incomes. Importantly, this vulnerability became evident after an extended period of time – well beyond the time frame of government-sponsored programme evaluations and other assessments (DIIS, Citation2020).

At a more fundamental level, labour market adjustment assistance was established with the goal of helping workers into new employment as quickly as possible. Too little was undertaken to equip them with new, high-level skills or to restructure local economies towards emerging markets focussed on advanced manufacturing, professional services, or other emerging industries. Implementation of government policies informed by the ideals of a Just Transitions would have prioritised both these challenges. In addition, Just Transitions embed labour market training and skills acquisition into their programme designs, but our analysis has demonstrated the skills and tacit knowledge of former automotive workers were lost from the workforce or were not fully appreciated/deployed in their new places of work. This represents a significant loss given current policy and public debates in Australia on skills shortages and the inability of businesses to find staff. In part, as Dinmore and Beer (Citation2022) have noted, former automotive industry workers may not be seen to represent a good ‘fit’ with the emerging job opportunities because of their age, preference to work locally rather than where new jobs are being created, as a consequence of prejudice and because retrenched workers have not received sufficient guidance to, and assistance with, future employment outside their former industry.

Just Transitions perspectives direct policy makers and researchers alike to consider the wider societal impacts of change, and the degree to which policy responses and government actions are inclusive. There is clear evidence that such considerations have not been given sufficient attention. As noted earlier in the paper, there was a clear sentiment that governments and industry alike had not met the expectations of community with respect to leading this process of change. Social service providers, with limited real influence, but a significant presence ‘on the ground’ were assessed far more favourably. In addition, our analysis presents a stark picture of the gendered impacts of the closure of the automotive sector in Australia, with the median wages of women relative to men falling by five percentage points over three years. Many factors likely contributed to this outcome, including the nature and pay rates of the employment opportunities available to men and women, the take up of part time work and the greater care responsibilities of women, which increased for many during the COVID-19 lockdowns, impacting on their availability for paid work. Clearly, however, the closure of the car industry was much more detrimental for the future earnings of women than for men and, under a Just Transitions framework, this issue would have been specifically addressed.

Overall, there is much to celebrate in the labour market outcomes of workers made redundant from the Australian car industry. However, a simple focus on whether those made redundant found new work appears insufficient, especially when judged against the benchmarks established for a Just Transitions. There is a pressing need to address those broader dimensions of change, including achieving social cohesion, strengthening regional economies and implementing more co-ordinated approaches. These did not happen, and we can only conclude that greater attention to Just Transitions principles and practices will result in better outcomes in the future, especially as Australia and other nations decarbonise their economies. It is also evident that considerable progress has been made over the past two decades in the management of plant closures (Beer & Thomas, Citation2007; Irving et al., Citation2022). The progress that has been made to date is encouraging and speaks to the capacity for further evolution in how Australia responds to economic shocks. The Just Transitions framework is now a mature and comprehensive perspective, one that understands the need to respond to change at both the local level and across the national economy. It also recognises the social, gendered, technological, and justice dimensions of economic transformation and the consequent need to build new skills to enable future prosperity. It continues to represent an ideal for dealing with future plant closures, and if implemented it would ensure a future that is more equal, productive and sustainable.

Statement on ethics

All participants in this study provided informed verbal consent before being interviewed. The study and questions were approved by the University of South Australia Research Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 203492), which is responsible for ensuring that University research complies with national research ethics guidelines as outlined in National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018).

Citation: National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrew Beer

Prof Andrew Beer is Executive Dean of UniSA Business at the University of South Australia. His research interests include the operation and functioning of Australia’s housing markets, the drivers of regional growth, economic change in major cities and the impact of major plant closures.

Sally Weller

Assoc. Prof Sally Weller is an economic geographer and economic sociologist at the University of South Australia. Her interests focus on labour markets, regional development and Australian political economy.

Helen Dinmore

Dr Helen Dinmore is a Research Fellow in UniSA Business at the University of South Australia. She has a background in the humanities and her research interests include housing, work, and social and economic disadvantage.

Julie Ratcliffe

Prof Julie Ratcliffe is Matthew Flinders Fellow and Professor of Health Economics at Flinders University. Her research interests include measuring and valuing quality of life and wellbeing in individuals and communities and the application of choice modelling in establishing individuals and community preferences for employment re-structuring and future employment options.

Ilke Onur

Ilke Onur is an Associate Professor of Economics in the College of Business, Government and Law at Flinders University. His general field of research is applied microeconomics with special focus on industrial organisation, auctions, health and development economics, economics of information systems and electronic commerce.

David Bailey

Prof David Bailey is Professor of Business Economics at the Birmingham Business School, and a Senior Fellow of the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe programme, exploring the impacts of Brexit on UK automotive and manufacturing. He has written extensively on industrial and regional policy, especially in relation to manufacturing and the auto industry.

Tom Barnes

Dr Tom Barnes is an economic sociologist and ARC DECRA Senior Research Fellow at Australian Catholic University (ACU) in Sydney. His research primarily focuses on insecure, precarious and informal work in Australia and Asia.

Jacob Irving

Mr Jacob Irving is a Project Officer supporting research activities in UniSA Business at the University of South Australia. His current PhD research investigates the impacts of emerging transport technologies on land use, and his research interests include urban economics and spatial studies.

Sandy Horne

Ms Sandy Horne is Project Officer: Research for UniSA Business at the University of South Australia. She has worked closely on several Category 1 funded research projects.

Josefina Atienza

Ms Josefina Atienza is Linkage Research Coordinator in UniSA Business at the University of South Australia.

Markku Sotarauta

Prof Markku Sotarauta is Professor of Regional Development Studies in Faculty of Management and Business at Tampere University, Finland. In 2011-2013, he served as the founding Dean of the School of Management and, in 2009-2010, as the last Dean of the Faculty of Economics and Administration. Professor Sotarauta specialises in leadership and institutional entrepreneurship in city and regional development.

References

- ACIL Allen Consulting. (2019). The transition of the Australian car manufacturing sector - outcomes & best practice summary report, department of employment, skills, Small and Family Business, July 2019. https://docs.employment.gov.au/documents/transition-australian-car-manufacturing-sector-outcomes-and-best-practice-summary-report.

- Bailey, D., Bentley, G., de Ruyter, A., & Hall, S. (2014). Plant closures and taskforce responses: An analysis of the impact of and policy response to MG Rover in Birmingham. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2014.899477

- Bailey, D., De Ruyter, A., Michie, J., & Tyler, P. (2010). Global restructuring and the auto industry. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(3), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq029

- Barnes, T., & Weller, S.A. (2020). Becoming precarious? Precarious work and life trajectories after retrenchment. Critical Sociology, 46(4-5), 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920519896822

- Beale, G. (2024). Just for whom? Lessons from Australia’s automotive closure. In A. Cebulla (Ed.), The future of work and technology: Global trends, challenges and policies with an Australian perspective (pp. 97–116). CRC Press.

- Beer, A. (2018). The closure of the Australian car manufacturing industry: Redundancy, policy and community impacts. Australian Geographer, 49(3), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2017.1402452

- Beer, A., Barnes, T., & Horne, S. (2021). Place-based industrial strategy and economic trajectory: Advancing agency-based approaches. Regional Studies, 984–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1947485

- Beer, A., Baum, F., Thomas, H., Lowry, D., Cutler, C., Zhang, G., Jolley, G., Ziersch, A., Verity, F., MacDougall, C., & Newman, L. (2006). An evaluation of the impact of retrenchment at Mitsubishi focussing on affected workers, their families, and communities: Implications for human services policies and practices. Flinders University.

- Beer, A., Sotarauta, M., & Bailey, D. (2023). Leading change in communities experiencing economic transition: Place leadership, expectations, and industry closure. Journal of Change Management, 23(1), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2023.2164936

- Beer, A., & Thomas, H. (2007). The politics and policy of economic restructuring in Australia: Understanding government responses to the closure of an automotive plant. Space and Polity, 11(3), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570701811569

- Beer, A., Weller, S., Barnes, T., Onur, I., Ratcliffe, J., Bailey, D., & Sotarauta, M. (2019). The urban and regional impacts of plant closures: New methods and perspectives. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1622440

- Celli, V., Cerqua, A., & Pellegrini, G. (2023). The long-term effects of mass layoffs: Do local economies (ever) recover? Journal of Economic Geography, 23(5), 1121–1144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbad012

- Dall-Orsoletta, A., Ferreira, P., & Dranka, G. (2022). Low-carbon technologies and just energy transition: Prospects for electric vehicles. Energy Conversion and Management: X, 16, 100271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2022.100271

- Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (DIIS). (2020). Australian Automotive Industry: Transition following the end of Australian motor vehicle production. Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. January.

- Dinmore, H., & Beer, A. (2022). Career degradation in Australian cities: Globalization, precarity and adversity. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2022.2078737

- Fairbrother, P., Snell, D., Bamberry, L., Carias Vega, D., Homsey, C., Toome, E., Cairns, G., Stroud, D., Evans, C., & Gekara, V. (2013). Skilling the Bay-geelong regional labour market profile, final report. RMIT University.

- Galgóczi, B. (2020). Just transition on the ground: Challenges and opportunities for social dialogue. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 26(4), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680120951704

- Healy, N., & Barry, J. (2017). Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy, 108, 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.014

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘Just Transition’? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 88, 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

- ILO. (2015). Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all. International Labour Organization. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_432859.pdf.

- Irving, J., Beer, A., Weller, S., & Barnes, T. (2022). Plant closures in Australia’s automotive industry: Continuity and change. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2021.2016071

- Johnstone, P., & Hielscher, S. (2017). Phasing out coal, sustaining coal communities? Living with technological decline in sustainability pathways. Extractive Industries and Society, 4(3), 457–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2017.06.002

- Krzywdzinski, M. (2020). Globalisation, decarbonisation and technological change: Challenges for the German and CEE automotive supplier industry. In B. Galgóczi (Ed.), Towards a just transition: Coal, cars and the world of work. ETUI, The European Trade Union Institute. Retrieved 05:05, January 05, 2024, from https://www.etui.org/publications/books/towards-a-just-transition-coal-cars-and-the-world-of-work.

- Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12008

- Newsome, A. (2015). Trade unions, immigration and immigrants in Europe revisited: Unions’ attitudes and actions under new conditions. Comparative Migration Studies, 45(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40878-015-0003-x

- Normann, H., & Tellman, S. (2021). Trade unions’ interpretation of a just transition in a fossil fuel economy. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40, 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.09.007

- Pai, S., Harrison, K., & Zerrifi, H. (2020). A systematic review of the key elements of a Just Transition for fossil fuel workers. Clean Economy Working Paper Series, Wp, 20–04. April.

- Pichler, M., Krenmayr, N., Maneka, D., Brand, U., Högelsberger, H., & Wissen, M. (2021). Beyond the jobs-versus-environment dilemma? Contested social-ecological transformations in the automotive industry. Energy Research & Social Science, 79, 102180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102180

- Rainnie, A., Beer, A., & Rafferty, M. (2019). Effectiveness of place-based packages. Regional Australia Institute.

- Rainnie, A., Herod, A., & McGrath-Champ, S. (2011). Review and positions: Global production networks and labour. Competition & Change, 15(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1179/102452911X13025292603714

- Routledge, P., Cumbers, A., & Derickson, K. D. (2018). States of just transition: Realising climate justice through and against the state. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 88, 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.015

- Snell, D. (2018). ‘Just transition’? Conceptual challenges meet stark reality in a ‘transitioning’ coal region in Australia. Globalizations, 15(4), 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1454679

- Tierney, J., Weller, S., Barnes, T., & Beer, A. (2023). Left-behind neighbourhoods in old industrial regions. Regional Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2234942

- Wang, X., & Lo, K. (2021). Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291

- Weller, S., Beer, A., Porter, J., & Veitch, W. (2020). Identifying measures of success for a global best-practice thermal coal mine and thermal coal-fired power station closure – Final Report. UniSA Business.

- While, A., & Eadson, W. (2022). Zero carbon as economic restructuring: Spatial divisions of labour and just transition. New Political Economy, 27(3), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1967909