ABSTRACT

This paper contributes towards our understanding of the role of public sector organisations in delivering circular economy (CE) goals, suggesting that such organisations seek to deliver social value when implementing CE activities. Through empirical evidence from Wales, and a programme designed to deliver circular outcomes via increased collaborative working in public sector organisations, the paper shows that public sector actors interpret the CE as a means to deliver well-being outcomes. The paper shows that public sector organisations, in Wales, are seeking to exploit the maximum social value from CE activities. This, the paper argues, requires a nuanced attention to the context and circumstances in which public service delivery is implemented. A legislative framework, the Wellbeing Future Generations Act (2015), that promotes collaborative working with people and communities to prevent persistent problems such as poverty, health inequalities and climate change, is supporting the creation of a definition of a CE that connects people and wellbeing to resource loops. The key contribution of the paper is to provide an empirical model demonstrating how public sector organisations in Wales are enacting CE in Wales, mediating between and integrating the social, material and spatial elements of a CE.

1. Introduction

The circular economy (hereafter, CE) is commonly conceptualised as a system in which the use of finite resources is decoupled from economic growth. Some arguments in favour of its adoption, however, suggest that the CE has the potential to bring attendant social and environmental benefits (Van Buren et al., Citation2016). While multiple, often competing, definitions are mostly rooted in business language and focus on economic growth as the primary form of value creation (Kirchherr et al., Citation2017) social topics such as ‘just’ transitions and the concept of a circular society are increasingly becoming part of a CE conceptualisation (Kirchherr et al., Citation2023). It has been suggested that the pursuit of a CE transition has the potential to achieve transformative outcomes and produce positive social change that contributes to the public good (Lazarevic et al., Citation2022; Mazzucato, Citation2013).

According to one of its predominant advocates, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (Citation2015), the CE can help achieve welfare and sustainable economic growth, addressing inter and intra-generational equity concerns through the preservation of natural capital and resource productivity. Hitherto, many of the applications of CE principles have concentrated on the redesign of manufacturing and service systems to benefit the biosphere. While the resultant ecological renewal and reduction of finite resources clearly benefits humankind, the recognition of the social aspects (e.g. how can the CE lead to greater social equality, both at the geographic and intergenerational levels?) has received less attention.

Programmes and policies for a CE are fast becoming key to regional, national and international plans for creating sustainable futures (Korhonen et al., Citation2018), yet there are concerns in the way in which broader social implications are attributed to – and can be achieved by – the CE (Hobson & Lynch, Citation2016; Moreau et al., Citation2017). As a contested concept (Korhonen et al., Citation2018; Lazarevic & Valve, Citation2017), there are open questions about the social dimension of the CE and how it might affect, for example, inequality, the distribution of resources and exploitation of labour (Schröder et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the importance of social elements within the CE (Murray et al., Citation2017) has not been examined in depth either conceptually and empirically.

Some fruitful contributions are starting to emerge to address the question of how a CE can become a tool for transformative change (Calisto Friant et al., Citation2020) that can support the well-being, capabilities and choices of future generations (Schröder et al., Citation2020). Such transformative changes are the remit of public sector organisations (PSOs), in their role to address social inequalities and to support all members of the community. This paper contributes towards our understanding of the role of PSOs in delivering CE goals and shows how PSO practitioners and decision makers interpret the CE to deliver well-being outcomes.

The paper starts from the consideration of the role of PSOs in delivering CE goals and provides empirical evidence that PSOs seek to deliver social value from CE activities. This, the paper argues, requires a nuanced attention to the context and circumstances in which public service delivery is implemented.

Arguments in favour of the importance of the need to understand context-bound barriers for CE, and the exploration of what needs to change, where problems lie and how this might influence/ enable the shift towards a CE in a particular territorial context are not new (see, for example, Grafström & Aasma, Citation2021; Lever & Sonnino, Citation2022) and can offer useful insights into the way in which a nuanced spatial CE approach can be conceptualised. Williams (Citation2019) suggests that a spatial approach to the CE implies a great deal more than creating a CE and circular business models within specific spatial contexts. A spatial circular approach, we contend, can tackle many other socio-economic problems affecting cities and regions. Hence, PSOs, being at the centre of service delivery, can promote a CE that is an expression of place-based innovation and experimentation that seeks to connect people and well-being to resource loops. The paper, therefore, asks the following questions: Q1: to what extent are current CE approaches adequate in explaining how PSO practitioners and decision makers interpret the CE in public service delivery?; Q2: How can we articulate the way in which PSOs in Wales use CE approaches that place social and ecological value creation as essential orientations (Haase et al., Citation2024; Jaeger-Erben et al., Citation2021)?

To address these questions, the paper examines the case study of Wales (one of four devolved territories of the UK). Wales was the first European country to adopt sustainable development as a statutory duty and the first to embrace social and economic wellbeing in its policy repertoire by establishing a Wellbeing of Future Generations Act (hereafter, WFGA) (2015). The act is ‘a one of a kind’ legislation that places a statutory obligation on all public bodies in Wales, including the Welsh Government (WG) itself, to demonstrate how they are taking action to meet the national wellbeing goals. As the legislative environment seeks to promote collaborative working with people and communities to prevent persistent problems such as poverty, health inequalities and climate change, there seems, we argue, to be a more nuanced definition of a CE emerging, one that connects people and wellbeing to resource loops. We draw our insights from data gathered during the recruitment phase of the Circular Economy Innovation Communities (CEIC) (2020–2023)Footnote1 initiative. CEIC sought to enhance collaboration between different local and regional governments, public and third-sector organisations to undertake innovation around service delivery that could provide CE benefits.

The key contribution of this article is therefore to provide an empirical model demonstrating how PSOs in Wales are enacting CE in Wales, mediating between and effectively integrating the social, material and spatial elements of a CE.

The paper starts with a brief overview of the role of PSOs in CE transition and the opportunities that a CE can offer to reach social goals. It follows with a brief discussion of emerging spatial approaches that investigate circular cities and regions. After introducing the methodological approach, we explore the challenges that PSOs have suggested could benefit from regional collaboration and the adoption of CE solutions as they emerged through the CEIC recruitment process. Before highlighting venues for future research, we discuss how the WFGA has set transformation direction, which have informed the way in which PSOs develop a CE framing, leading to opportunities to connect well-being to resource loops.

2. Addressing the social in the circular economy

Researchers have recently started to identify the need to reconcile CE approaches with wider sustainability discourse, including the social dimension. The lack of linkages between CE and sustainable development was first highlighted by Kirchherr et al. (Citation2017). As suggested by Padilla-Rivera et al. (Citation2020, p. 2)

notwithstanding a few voices from authors advocating for the inclusion of social aspects in CE concepts, tools, and metrics, the concept of CE today clearly appears to prioritize the economic system with primary benefits for the environment, either resource efficiency or environmental efficiency, and only implicitly addresses gains for social aspects.

While we do not have space here to discuss these contributions in detail, it is important to highlight that a CE might come to define very contrasting visions of sustainable development (Bauwens et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, while there is common agreement that the transition towards a CE could foster more sustainable futures, these will likely have very different social and economic foundations (Lowe & Genovese, Citation2022). Importantly, contributions to address societal well-being call for CE approaches that can put social and ecological value creation as essential orientations (see for instance Jaeger-Erben et al. (Citation2021) and, in contrast, Haase et al. (Citation2024)). In addition, Dzhengiz et al. (Citation2023) identified several reoccurring conceptualisations of CE in extant reviews. Some authors, to address such conceptual plurality, see the CE a ‘floating signifier’ (Corvellec et al., Citation2022; Niskanen et al., Citation2020; Rödl et al., Citation2022). Viewing the CE as a ‘floating signifier’ suggests that its meaning is dependent on the context in which it is being explored. As such, the concept may absorb different forms of meaning (e.g. serving different purposes) and each group or individual may have their own perspective on what the term means, leading to differing interpretations. Hence, such understanding of the CE might allow for ‘an expansion of the imaginary regarding other possible circular futures’ (Calisto Friant et al., Citation2020, p. 2) and deliver transformative outcomes.

As PSOs become increasingly engaged in the CE transition, not only as policymakers but also as adopters of CE practices and strategies in their service delivery, there are opportunities and potential to better understand how CE approaches to public service delivery can bring sustainability benefits that encompass the social dimension and enrich the meaning of the CE concept.

2.1. Public sector’s role in the circular economy

As PSOs are confronted with both increasing demand and resource constraints, they become central to the mitigation of many pressing and often ‘wicked’ social and environmental problems (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973) and to the promotion of different approaches in their resolution (Weber & Khademian, Citation2008). Hence, there is a growing interest in public service innovation (De Vries et al., Citation2016; Vickers et al., Citation2017), the role of PSOs as core actors in CE transitions (Klein et al., Citation2020; Klein et al., Citation2022) and the specific challenges that PSOs might face in introducing CE innovations (Clifton et al., Citation2024).

Recent academic research has explored the role of the public sector as a ‘regulator’ of CE transition (Klein et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, PSOs could also be seen as (i) major economic actors within the CE as significant purchasers of goods and services; (ii) role models where the public sector can serve as an example of good practices and (iii) pursuers of multiple political and social goals as demonstrated by PSOs engagement and growing interest in sustainability practices (Droege et al., Citation2021; Khan et al., Citation2020; Klein et al., Citation2020). The first two refer directly to CE practices adopted in areas such as public procurement, internal operations and day-to-day work processes and procedures of PSOs (see for instance Alhola et al. (Citation2019) and Rocca et al. (Citation2023)); the third one – PSOs as pursuers of multiple political and social goals – refers directly to the role that PSOs can play in the delivery of public services and how circularity can be integrated into public services facing citizens and society (Klein et al., Citation2020). In this respect, as argued in Clifton et al. (Citation2024), circular innovation in PSOs will also involve external stakeholders, such as citizens, businesses, and third-sector organisations, through the co-production of circular public service delivery (e.g. via public–private partnerships and stakeholder engagement). In practice, however, research and evidence on CE in PSOs still predominately focuses on circular initiatives oriented towards emission and waste reduction and energy and resource efficiency (Klein et al., Citation2022).

Nevertheless, PSOs and public service delivery cover many aspects of everyday life – health, social care, education, early years, community justice, enterprise and skills – and as public sector service provision often revolves around providing cost-effective services and creating societal wellbeing, there are further opportunities to investigate the relationship between PSOs – vis-à-vis public service delivery – and CE. We refer here to the opportunities to deliver, among others, ‘public’ goals, to promote societal innovation, circular society initiatives, citizens’ wellbeing, and CE-based collaboration platforms. For instance, PSOs can support societal innovation and mobilise multi-actor collaboration in addressing the needs of service users and create ‘social value’ by contributing to human and social life (Moulaert & Sekia, Citation2003; van der Have & Rubalcaba, Citation2016). In relation to the UK’s National Health Service, Vickers et al. (Citation2017), stress how the role of the re-organisation of public services via market-based principles with an increasingly diverse range of providers from the public, private and civil society sectors can address community health needs and social value. Marchesi and Tweed (Citation2021) argue that there are opportunities to explore the co-production and co-creation of service delivery and the empowerment of consumers/ service users in the social housing sectors. These examples suggest that there might be opportunities for PSOs to deliver public services that offer the potential for better performance and efficiency, financial savings, and social cohesion via cross-sectoral and territorial coalitions of social actors (Gallego-Bono & Tapia-Baranda, Citation2022; Pusz et al., Citation2024). A broader approach to CE in PSOs – one that can produce positive social change – will therefore require attention to and participation across multiple stakeholders, for the production and allocation of goods and services in PSOs service delivery.

2.2. A spatial approach to the circular economy

There has been increasing attention paid to the role of cities and regions as important sites for action to promote societal transformations to more sustainable production and consumption patterns (Vergragt et al., Citation2016). On the one hand, the pressures associated with tackling climate change and reducing carbon emissions have given rise to a rescaling of environmental governance in which the state has explicitly devolved and redistributed environmental responsibilities downwards to cities and regions (Bulkeley, Citation2005; Gibbs & Jonas, Citation2000; While et al., Citation2010). On the other hand, cities and regions are often perceived by practitioners as pioneers in the transition towards sustainability, frequently instigating changes before national policies have been devised (Arsova et al., Citation2021).

There are several factors that explain the growing importance of the role of cities and regions. Cities and regions, for example, are responsible for framing and putting into practice a wide range of policies in different fields, including planning, water, waste and public transportation (Erickson & Tempest, Citation2014), with city and regional development governance, visions and policies playing important roles in supporting the transitions towards sustainability (Bradshaw & de Martino Jannuzzi, Citation2019; Galarraga et al., Citation2011). Moreover, uneven distribution of innovation processes is often influenced by actors, networks and institutions at these spatial levels (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Local and regional actors have a deep knowledge and understanding of their environment and local territories, with proximity to environmental, social, and economic issues. Avdiushchenko (Citation2018) also suggests that, at the regional scale, one can more effectively measure some dimensions of circularity, such as CE entrepreneurship, waste management or sharing initiatives due to the number of structural, cohesion and investment funds that might operate at this level.

Within the CE literature, discussions across different geographic scales often refer to the distinction between the micro (e.g. products and individual companies and innovation potential), the meso (e.g. eco-industrial park and the opportunities that neighbouring industries can offer in terms of increased environmental and economic efficiency) and the macro level, which looks at the way in which cities, regions and nations are key actors for the CE, both in terms of policy for and – in support of – CE and the adoption of circular models (Aranda-Usón et al., Citation2020; Prendeville et al., Citation2018). These contributions share a focus on how cities and regions are the scale at which most circular innovations emerge and the way in which regional and local flows of materials and products, in order to extend the life cycle of products, can reduce waste generation and the consumption of resources. While most studies that adopt a spatial approach to the CE derive from the urban and city realm, a regional lens is also useful. Such a lens can help capturing the dimension of metabolic flows, which extend beyond the administrative boundaries of cities, connecting actors and activities across regional boundaries and beyond (Heurkens & Dąbrowski, Citation2020).

Within these research contributions that seek to identify the geographical implications of the CE, we can distinguish two levels of analysis. The first one seeks to highlight the different factors that can influence the adoption of CE aimed at categorising the state of CE development within a given city/ region. The second level, on the contrary, seeks to question the extent to which the current CE approach is adequate when applied to cities and regions. Some research investigates how deep historical roots and the overall development trajectory of territories can influence CE transition (Tapia et al., Citation2021). Veyssière et al. (Citation2022) for instance, highlight that local and institutional factors are key in facilitating the implementation of CE. These include existing social networks and common shared values. Moreover, of specific interest here are the contributions spanning from the investigation of CE practices within the built environment and the opportunities offered from circular approaches to sustainable housing, transport and green infrastructure that have developed as a distinctive area of research (Calisto Friant et al., Citation2023; Diesch & Massari, Citation2024; Tsatsou et al., Citation2023; Williams, Citation2023). This research, in particular, questions the extent to which the current CE approaches are adequate when applied to cities and regions.

While there is a wide variety of actors engaged in the CE that operate at different levels – including governance systems – and resource flows that exceed city and regional boundaries, there are a number of opportunities that a spatial approach to the CE can offer. Firstly, cities and regions represent centres of both production and consumption. Agreeing with Williams (Citation2019) CE approaches currently focus on the production side; the need – and opportunities – for addressing sustainable consumption patterns, in cities and beyond, is understudied. This is particularly relevant when considering the localisation of resource flows and the importance of how different geographical scales interact in closing resource loops. Marsden and Farioli (Citation2015) propose that to achieve synergies between sustainability, security, sovereignty, and effective resource governance, a more place-based eco-economic model needs to be advanced.

Secondly, land – and land use – is often overlooked as a resource, despite the importance and value for cities and regions. We are referring here to how cities and regions might allocate land and resources to natural systems through planning processes (Williams, Citation2023). For instance, a spatial circular approach can encourage changes to public transport infrastructure to increase green mobility and the re-organisation of public spaces. CE can provide opportunities to create public spaces that encourage citizen to cooperate and develop social innovation as well as prioritise green infrastructure systems such as public space and green areas.

Moreover, infrastructure networks such as electricity, gas, water, transport, data and waste networks are embedded in specific territories – being cities and regions – even if they organise flows for other wider spaces (Goldthau, Citation2014). Thus, infrastructure networks – or the lack of – can present opportunities (and challenges) to facilitate circular approaches and the circulation of resources. Local food production, local energy systems of production and provision as well as green mobility and waste recovery are some of the examples emerging as cities and regions experiment with the CE concept (Aranda-Usón et al., Citation2020; Prendeville et al., Citation2018).

Lastly, in light of persistent environmental and social challenges (such as climate change and problems of regional economic restructuring), socio-ecological innovation approaches, such as foundational economy and CE, are increasingly representing examples of place-based innovation that allows to capture the directionality of innovation, opens up to new innovation actors and encourages place-based experimentation (Coenen & Morgan, Citation2020; Lazarevic et al., Citation2022). This also extends to include the normative turn in regional innovation policy (Uyarra et al., Citation2019) in seeking to address societal challenges emphasising that regional policy can, together with other stakeholders, steer innovation systems into specific directions (Isaksen et al., Citation2022). Moreover, with regard to the regional scale there is evidence of what Newsholme et al. (Citation2022) term the ‘double disjuncture’, whereby the expectations of policymakers are out of line with both the national policymakers and local business actors.

2.3. Key factors of a revised circular economy approach to connect human well-being to resource loops

We have sought to highlight the relevance of the two strands of emerging research – one looking at the role of PSOs in CE, the other exploring emerging spatial approaches that investigate circular cities and regions – in understanding how CE approaches can facilitate social change.

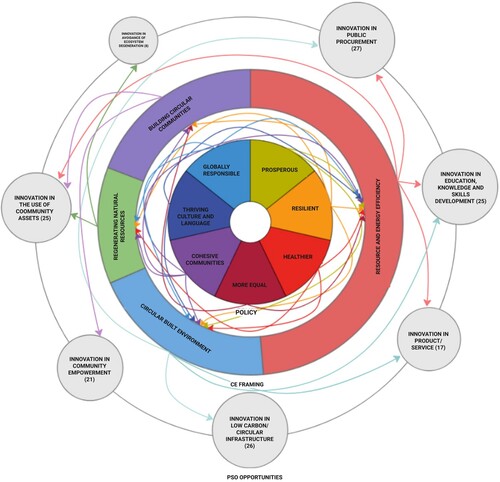

In order to reconcile and effectively integrate the social, material and spatial elements into the CE concept, a number of factors need to be considered that emerge from the literature reviewed above. These are: (i) the relevance of agency in providing meaning to CE approaches. In particular, with reference to PSOs, this alludes to the multitude of actors involved, framing different articulations and understanding of the CE (e.g. how this might differ in the public and private realms). This also includes actors such as regional and local governments that can support via policy development a set of common shared values around CE framing to mobilise actors; (ii) participation across multiple stakeholders, incorporating community and participatory processes in public sector service delivery to provide better access to resources in addressing and tackling socio-economic problems; and (iii) circular approaches to resource management – that include resource efficiencies, the built environment (such as building and infrastructure assets); regeneration of natural resources through more effective use of land and other environment assets, and provision of opportunities for communities to benefit from CE innovation (we refer here specifically to the building of circular communities of production and consumption). Thus, a spatial approach to the CE for PSOs implies more than just adopting circular business models and resource loops within specific spatial contexts. These are summarised in .

Figure 1. Key elements of a revised circular economy approach through which PSOs connect human wellbeing to resource loops.

We now turn to empirically investigate how these factors are informing a more nuanced definition of a CE, one that connects people and wellbeing to resource loops.

3. The Welsh context: public service delivery and the Future Generation Act

Wales (one of four devolved territories of the UK) was one the first European countries to adopt sustainable development (SD) as a statutory duty with SD becoming the central organising principle of the WG. In 2019, the WG was the first devolved nation in the UK to declare a climate emergency, committing to net zero by 2050 (subsequently revised to 2030) and setting up ambitions to promote a pathway towards a zero waste and low carbon economy (see, for example, WG, Citation2021; WG, Citation2022). Devolution and local government reform have allowed for the emergence of a regional and local governance in the UK. The case of Wales is interesting as it is attempting to promote a distinctive sustainability transition pathway and, analytically, sub-national governments can be considered to exemplify relevant qualities of regions such as becoming key strategic space for the management of economic, social and environmental tensions (see for instance De Laurentis et al., Citation2017).

In terms of PSOs and public sector reform, one of the most important pieces of legislation to be introduced in Wales in recent years is the Wellbeing Future Generations Act (WFGA) (2015). The WFGA has established a radical new framework for place-based development that, whilst we do not have the space to appraise the success (or otherwise) of the framework, mandates a new process of co-production that challenges the hierarchical division of labour between the state and the citizen. Since 2015, the act has placed a legal duty on the Welsh public sector and WG Ministers to deliver their work, while considering the needs of future generations and planning for long-term well-being. Public bodies and Welsh Ministers are now required to adopt and use a sustainable development principle in their governance and operations reframed around seven national wellbeing goals.

The act sets up seven connected well-being goals. These are:

- A prosperous Wales: An innovative, productive and low carbon society which recognises the limits of the global environment and therefore uses resources efficiently and proportionately (including acting on climate change); and which develops a skilled and well-educated population in an economy which generates wealth and provides employment opportunities, allowing people to take advantage of the wealth generated through securing decent work;

- A resilient Wales: A nation which maintains and enhances a biodiverse natural environment with healthy functioning ecosystems that support social, economic and ecological resilience and the capacity to adapt to change (for example, climate change);

- A healthier Wales: A society in which people’s physical and mental well-being is maximised and in which choices and behaviours that benefit future health are understood;

- A more equal Wales: A society that enables people to fulfil their potential no matter what their background or circumstances (including their socio-economic background and circumstances);

- A Wales of cohesive communities: Attractive, viable, safe and well-connected communities;

- A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language: A society that promotes and protects culture, heritage and the Welsh language, and which encourages people to participate in the arts, and sports and recreation;

- A globally responsible Wales: A society that promotes and protects culture, heritage and the Welsh language, and which encourages people to participate in the arts, and sports and recreation.

The act also identifies five ways of working, which public bodies need to evidence, and consider, in applying the sustainable development principle. These include long-term, integration, involvement, collaboration and prevention. Both involvement and collaboration stress the relevance of involving people with an interest in achieving the wellbeing goals via for instance stakeholder engagement, cross-regional collaboration and collaborative working to meet the wellbeing objectives.

These goals, and the ways of working, are important and, we argue, supported a more nuanced definition of a CE emerging, one that connects people and wellbeing to resource loops..

4. Methodology

We draw our insights from data gathered during the recruitment process for the Circular Economy Innovation Communities (CEIC) programme. CEIC was a regional intervention, funded under Priority 5 axis of the European Social Fund, ‘Public services reform and regional working’. It aimed to bring together public service providers from the public and third sectors across South Wales to develop innovative services that provide CE benefits.

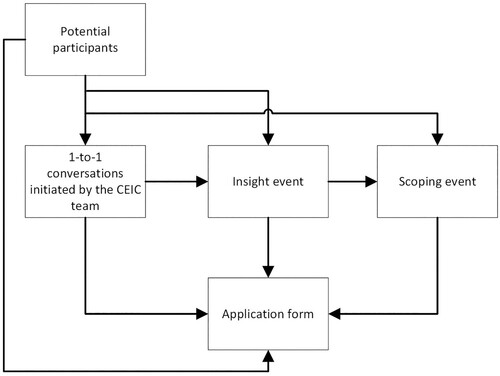

The pathways through which potential participants could engage with the CEIC team during the recruitment process for CEIC are shown in .

Figure 2. The multiple pathways through which potential participants engaged with the CEIC team.

Note: Each node in the process diagram provided the opportunity for the team to ask participants ‘What public service challenges are you facing that would benefit from a circular economy lens?’

Our research adopted a method of qualitative inquiry that can be described as ‘participatory conversation’ (Swain & King, Citation2022, p. 2). We adopted a combination of purposive and snowball sampling aligned with our recruitment strategy. Public service providers eligible to take part in the programme were initially contacted by a member of the CEIC team by email or phone call to raise awareness of the programme. In discussions with participants, the CE innovation process was framed as a lens through which any challenge could be viewed in order to develop inherently resource efficient solutions. During the early interactions, the CEIC team asked, ‘What public service challenges are you facing that would benefit from a circular economy lens?’. The responses to this question were noted in a master document for each cohort. The public service providers were invited to bring colleagues and their public service networks to one of CEIC’s weekly insight events, which were also made open to all public and third-sector organisations in South Wales. In the insight events, participants were given a chance to answer the same question in breakout rooms, where responses were collected by CEIC facilitators and added to the master document. Where a critical mass of potential applicants interested in a particular aspect of service delivery emerged, the CEIC team ran ‘scoping events’ for the cohort to explore shared challenges. Depending on the pathway taken, potential participants had between one and four opportunities to provide a response. The key areas of discussion identified in the master document were clustered into key themes which were transcribed into short reports and shared with potential participants. Finally, as participants signed up to the programme, they were asked to write in the application form what challenge they would be interested in working on. Each of these engagements can be considered ‘stakeholder consultations’ (c.f. Anderson et al., Citation2008). In total, the CEIC research team engaged with 775 individuals across 123 public service organisations. A list of organisations engaged with is provided in .

Table 1. List of organisations engaged.

Many participants opted not to provide a response and a total of 156 individual statements from potential participants were collected across the master documents. In analysing the master documents, a template analysis process was used (King, Citation2012). The a priori codes used in the template were the overarching goals of the WFGA. The data assigned to the goals was further refined into themes that demonstrated how the PSOs envisioned the CE to be able to deliver against the different goals.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Themes emerging from PSOs interest in CE

The themes emerging from the analysis of public sector interests are presented in . Although separated in for heuristic purposes, such emerging themes have often appeared in combinations, being interconnected. The rationale followed was one that grouped them around the core driver identified and the one where the most benefits can be expected.

Table 2. Thematic priorities for public sector representatives engaged with during the CEIC recruitment process.

Four broad themes were identified that demonstrated how potential participants in the CEIC programme perceived the CE as an enabler of public service delivery: resource and energy efficiency measures adopted with regard to non-land and infrastructure assets needed to deliver public services; circular built environment addressing building and infrastructure assets; regenerating natural resources through more effective use of land and other environment assets; and building circular communities, connecting people to local resource flows.

In agreement with Klein et al. (Citation2022) findings, most of the ideas presented by PSOs were focused on addressing resource and energy efficiency measures. A total of seventy-one ideas were put forward by potential participants. In line with the public sector’s role as a ‘major economic actor’ (Klein et al., Citation2020), many of the potential participants saw public procurement as a mechanism through which they could deliver more resource and energy-efficient public services at the regional level. Twenty-three opportunities for circular public procurement were mentioned by participants during the recruitment process. The focus on public procurement is not unexpected; it meets two of the headline actions identified in WG’s Beyond Recycling: A strategy to make the circular economy in Wales a reality (WG, Citation2021) – supporting businesses in Wales to reduce their carbon footprint and become more resource efficient, and procuring on a basis which prioritises goods and products which are made from remanufactured, refurbished and recycled materials or come from low carbon and sustainable materials like wood. Supporting the public sector to make better procurement decisions has been a priority for WG and its CE delivery body, WRAP Cymru. Support for procurement has been offered by WRAP Cymru since 2016 and a new ‘Sustainable Procurement Hierarchy’ was released in 2021 (WRAP, Citation2021). Circular procurement was discussed in terms that would primarily contribute to the Wellbeing of Future Generation Goal of ‘A Prosperous Wales’, using the public purse to stimulate innovation. Moreover, a CE approach could also contribute to the ‘foundational economy’, which WG describes as ‘the part of our economy that creates and distributes goods and service that we rely on for everyday life’.Footnote2 Increasingly, the foundational economy, as argued by Coenen and Morgan (Citation2020), has become an example of place-based social innovation where the state, and PSOs, can be seen as the direct provider or funder to deliver foundational services and infrastructure. In addition, as suggested by Wahlund and Hansen (Citation2022) and Calafati et al. (Citation2021) a foundational economy could deliver social improvements in environmentally sustainable ways, particularly when it comes to regulating and controlling foundational sectors dependent on long-distance supply chains. As the table shows, participant PSOs highlighted that, for instance, public spending could support the foundational economy to directly contribute towards decarbonisation goals and a CE.

Additionally, potential participants did not only see themselves as enablers of innovation, but also as being actively engaged in innovative behaviours within organisations. A total of thirty-four challenges that would require innovation within organisations were mentioned by participants. As De Vries et al. (Citation2016) identify in their systematic literature review, the goals of public service innovation differ from those of private organisations. Potential participants identified the CE as an opportunity to contribute to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery (the ubiquitous ‘doing more with less’), through such approaches as multi-agency working, sharing and electrifying vehicle fleets and new patterns of service delivery such as the reuse or recycling of orthopaedic boots that would result in a ‘win-win’ situation that either reduced or shared the costs and environmental impact of the resources needed to deliver services. Beyond this, PSOs also identified opportunities to tackle societal problems that would contribute to ‘A resilient Wales’ and ‘A more equal Wales’, such as sensors to detect and address water pollution, using the CE to address poverty, health and wellbeing within communities, exploring active travel options and finding solutions for the charging of equipment in special needs schools. A third focus for resource and energy-efficient innovation was on the development of CE knowledge and skills across the current and future workforce, contributing to ‘A prosperous Wales’ by ‘developing a skilled and well-educated workforce’ and to the goal of ‘A globally responsible Wales’ by giving people the skills and knowledge to understand the impact of their actions on a global level. Fourteen ideas related to knowledge and skills development were provided. Innovation to support the embedding of CE skills (such as implementing carbon and circular literacy in housing associations and local authorities and developing curricula that provide CE learning opportunities) also contribute to the ‘ways of working’ espoused by the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act, particularly thinking for the long-term, prevention and involvement. As suggested in the public sector innovation literature such innovative goals cannot be achieved in isolation (cf Clifton et al., Citation2024) and a key point of the success in the interest shown in the programme was that participant PSOs welcomed the opportunity for different organisations to come together to generate sustainable solutions. For instance, health boards welcomed the opportunity to work with social enterprises to repurpose their cardboard waste, providing employment for disadvantaged members of the community.

The circular built environment theme brings together potential initiatives that make more efficient and effective use of public service-owned built assets and associated infrastructure, primarily social housing, education establishments, and hospital and local authority estates. The built environment and infrastructure is inextricably linked to the CE at city and regional levels. PSOs at local and regional levels might share responsibility for the development and maintenance of local infrastructure and investigate opportunities to planning, design and construction that can minimise material use and operational carbon emissions. Moreover, infrastructure is also necessary to facilitate circular activities and the circulation of resources.

In total, twenty-nine ideas relating to the circular built environment were put forward by potential participants, contributing to the Wellbeing of Future Generations goals of ‘A prosperous Wales’, ‘A resilient Wales’, ‘A healthier Wales’, ‘A Wales of cohesive communities’, ‘A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language’, and ‘A globally responsible Wales’. Partly due to the decision to focus early recruitment activities on social housing providers, the largest sub-group (twelve) refers to the need to decarbonise the substantial social housing estate in Wales which has been a significant focus in recent years for WG (see for example Green et al., Citation2019 for more context).

Sub-themes emerging in the circular built environment are similar to those seen for the resource and energy-efficiency measures theme. Built environment innovation to support resource efficiency and effectiveness in existing service provision was a key opportunity, with twenty-seven ideas suggested (for example, the sharing estates between PSOs, sharing of electric charging infrastructure, reconfiguring healthcare estates to deliver lower carbon healthcare, including at-home care options, using maintenance and improvement schedules to deliver resource and energy-efficiency measures in existing social housing, and digitally delivering leisure and cultural services in order to reduce built environment assets). Procurement processes (two ideas) are seen as levers to influence the construction supply chain through the development of specifications and tenders for circular construction.

The need for education, knowledge and skills development to address the significant skills gap in so-called green building (Hale et al., Citation2022) was also identified by one participant. There is also, however, the recognition that current built environment assets may not be able to deliver the scale of change needed to deliver CE benefits, particularly in the light of the climate emergency. Therefore, innovation opportunities are also seen in the provision of new built environment assets such as zero carbon schools (referring to schools that are net zero in both operational and embodied carbon) and application of design for life and circular principles to build environment assets. Finally, the need to preserve cultural built environment assets was identified by one participant in relation to the decarbonisation of historic public buildings. The opportunities for a circular built environment encompass planning as a tool for implementing circular development, an area most relevant in the literature (Williams, Citation2023). Moreover, place-based circular narratives linked to the built environment, as shown, do not always rely on economic competitiveness and technological innovation (Calisto Friant et al., Citation2023), but play the role of grounding circular innovation in context (Diesch & Massari, Citation2024) to address socio-economic challenges.

The regenerating natural resources theme brings together PSO ideas in relation to the protection and regenerative use of natural resources such as land, rivers and the sea. CE approaches are seen by PSOs to have the potential to support natural processes and restore natural ecosystems that have been affected by human activity. PSOs at city and regional level identify the opportunity to contribute to ‘A resilient Wales’ and ‘A globally responsible Wales’ by increasing biodiversity and reducing strain on local and global ecosystems caused by over-extraction of resources and pollution. Further, access to healthy green spaces can contribute to ‘A healthier Wales’, ‘A Wales of cohesive communities’ and ‘A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language’, bringing about wellbeing benefits associated with engagement with a healthy environment. PSOs where interested in seeking CE opportunities to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services from green infrastructure, among other the provision of environmental services such as energy and other social qualities of green infrastructure (cf. Cheshmehzangi et al., Citation2021).

Eighteen ideas addressing the regeneration of natural resources were put forward by potential participants, the lowest of the thematic CE action areas, reflecting Williams’ (Citation2023) contention that land and natural assets are often overlooked in the consideration of resource flows. The theme included ideas relating to the innovative use of natural assets in communities to simultaneously deliver health and social benefits and regenerate land (for example, using green space in hospital estates for circular social prescribing, regenerative community growing processes, implementation of nature-based solutions in social housing projects to minimise adverse effects of the climate emergency such as flooding). Other initiatives included innovation to monitor and improve the health of local ecosystems such as the development of water pollution sensors for monitoring the quality of water courses and processes to determine and address adverse impacts of visitors in public green spaces.

Finally, the ‘building circular communities’ theme recognises that the CE is enabled not only by flows of tangible resources, but also by the flows of intangible resources such as community goodwill and engagement. In doing so, it addresses that the CE is a systemic socio-technical transition (Loorbach et al., Citation2017). The theme is closely allied with that of circular built environment but acknowledges that community assets extend beyond the built environment. It is also closely allied with the theme of regenerating natural resources but focuses more on the social connection between humans and the natural ecosystem than on the ecosystem services delivered. This supports to a certain extent, what Calisto Friant et al. (Citation2024, p. 29) define as ‘social cycle of care’ in a CE.

We see from the opportunities identified by potential participants that PSOs perceive that local and regional communities can benefit from CE opportunities in a variety of ways. For instance, community-based circular initiatives can contribute to ‘A prosperous Wales’ by providing opportunities for decent work for local residents. ‘A resilient Wales’ could emerge through developing and securing local resources such as food and energy. This can also contribute to a fairer distribution of resources and ‘A more equal Wales’ and in the case of community health initiatives and community growing opportunities can contribute to ‘A healthier Wales’. Moreover, empowering communities to come together to innovate around environmental and social inequalities could contribute significantly to the goal of ‘A Wales of cohesive communities’.

Twenty-eight ideas related to the theme of ‘building circular communities’ were identified. PSOs considered that CE innovation activities could augment their efforts to become more circular (whether the goal of the innovation was to increase efficiency, reduce costs or deliver social benefits). For example, social housing providers saw the opportunity for community-based circular activities to contribute to a more holistic decarbonisation of their activities through, for the provision of repair cafes or the issuing of community-level waste avoidance challenges. PSOs also demonstrated particular interests in securing and sharing local resources through community energy and food projects as community growing and community pantries and the delivery of co-benefits such as the alleviation of food and fuel poverty (Lever & Sonnino, Citation2022). A key focus of opportunities in this theme was the empowerment and engagement of communities in decision-making (cf Diesch & Massari, Citation2024). This is in line with the ‘ways of working’ identified in the WFGA and specifically ‘involvement’, which emphasises ‘the importance of involving people with an interest in achieving the wellbeing goals and ensuring that those people reflect the diversity of the area which the body serves’. As such, potential participants saw opportunities for innovation in consultation processes for the use of community assets such as disused buildings, legacy industrial sites and green spaces, including potentially marginalised members of the community such as the elderly, digitally poor, homeless and learning and physically disabled. Moreover, and agreeing with Marchesi and Tweed (Citation2021), some of the examples under the ‘building circular communities’ theme illustrate that the implementation of a CE implicates not only the development of technological solutions for resource efficiency but also the promotion of production-consumption practices among citizens and service providers that might support resource efficiency and waste reduction (e.g. trialling the reuse and recycling of furniture and carpets within social housing provision) and induce behavioural change. A summary of how these themes connect with the key factors highlighted in the literature is presented in .

5.2. Mediating the social, material and spatial elements of a CE

Following the discussion of the themes emerging from PSOs interest in the CE, we return here briefly to the research questions posed in the paper.

The themes and examples illustrated above show that PSOs in Wales interpret the meaning of a CE in such a way that can deliver well-being outcomes and social value. The discussion demonstrates that, as suggested in the literature, the CE can be defined and implemented in a variety of ways, which are influenced by the multitude of actors involved, the context and policy programmes under which CE outcomes are sought to be achieved.

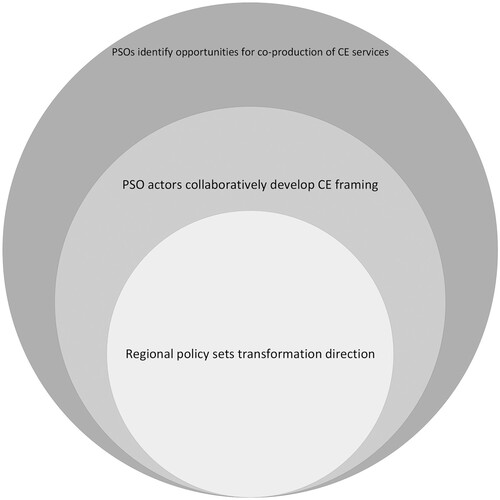

PSOs, as shows, seek to achieve a number of goals through CE opportunities that can address both socio-economic inequalities and improve resource management. Since the focus of the programme was on PSOs and third-sector organisations, it might not come as a surprise that transformative change is sought by PSOs as a way to address their fundamental role in society, one that addresses social inequalities and support all members of the community. PSOs have a deep knowledge and understanding of the environment and local territories in which they operate, with proximity to environmental, social, and economic issues. Hence, CE innovation challenges and opportunities in PSOs can be viewed as a lens through which resource-efficient solutions can be sought in addressing socio-economic outcomes, and vice-versa. This adds to the current research and evidence on CE in PSOs that, as discussed, still predominately focuses on circular initiatives oriented towards emission and waste reduction and energy and resource efficiency (cf Klein et al., Citation2020).

Importantly, the WFGA has provided ‘a particular direction of transformative change’ (Weber & Rohracher, Citation2012, p. 1042) that characterises the directionality domain in Wales. As the WG sees the CE as a key part of delivering at least some of the goals for the WFGA, this can be achieved through the coordination of actors’ interests, networks and institutions presented as the very core of the change process. The WFGA mandates a new process of co-production that challenges the hierarchical division of labour between the state and the citizen. This links CE innovation to collaboration, integration and long-term thinking that encompass PSOs to include communities and citizens. What it shows is that, according to Veyssière et al. (Citation2022), a local/ regional CE, will also need institutional factors to support coordination and the development of a set of common shared values to mobilise actors.

Finally, the table shows that CE in PSOs requires different stakeholders coming together to collaborate towards CE interventions, bringing different experiences and different types of knowledge about the same system (Schröder et al., Citation2020). The empirical evidence shown in the paper stresses that in many cases the initiatives investigated need to build on community participation and community empowerment. Such community engagement however highlights more than just certain mode of delivery – via participatory mechanism. It supports the claim that a CE while it seeks to preserve the value of products and materials for as long as possible (Haase et al., Citation2024), it can do so by considering flows of intangible resources such as communities and citizens. This suggests an alternative vision of circularity, one that questions current CE approaches especially those focussed on as a series of restorative and regenerative industrial systems – and associated business models – and places social and ecological value creation at its core. As the paper shows PSOs in Wales are experimenting with this vision seeking to deliver public services that offer the potential for better performance and efficiency and social cohesion, linking wellbeing goals to resource loops.

6. Conclusion

This paper has sought to contribute to our understanding of the role of PSOs in delivering CE goals. Starting from the consideration of the role of such organisations in delivering CE goals, the paper has provided empirical evidence that PSOs in Wales seek to deliver social value through their CE activities. Our empirical focus has been particularly useful for understanding the extent to which the CE challenges in PSOs are influenced by context. As PSOs seek to address the complex interplay of systemic social, economic and environmental problems, they identify opportunities to deliver public services that offer the potential for better performance and efficiency, financial savings, and social cohesion.

The empirical evidence has shown the importance of understanding how different actors might frame different articulations and understanding of the CE. In Wales, PSOs see the CE as an opportunity to deliver CE approaches to resource management – at city and regional levels – that include resource efficiencies, the built environment (such as building and infrastructure assets); regeneration of natural resources through more effective use of land and other environment assets, and provision of opportunities for communities to benefit from CE innovation. In addition, the legislative environment set around the WFGA in Wales has set transformation direction, which have informed the way in which PSOs develop a CE framing, leading to opportunities to connect well-being to resource loops.

The paper has suggested an empirical model demonstrating how PSOs in Wales are enacting CE in Wales, mediating between and effectively integrating the social, material and spatial elements of a CE. As shown, there is value in identifying how PSOs identify opportunities and work collaboratively to develop CE framing. This is important and future research should increasingly focus on empirical evidence such as the one provided here to support our understanding of the role of PSOs in delivering CE goals. The findings of this paper provide valuable insights and lessons to be learnt for further development of CE approaches.

Certainly, there are many further avenues for future research to be considered and a number of limitations that have affected the generalisability of the results; something that future research could address. The research scope has been restricted to a single case study, that of Wales, in a specific context and time, that of the recruitment of participants to the CEIC project. The recruitment process meant that some PSOs had greater levels of representation than others, and some individuals were able to identify and express opportunities for innovation on multiple occasions, which could lead to an over-exaggeration of the importance of some themes across the PSO landscape. For example, targeted recruitment of housing associations in the early stages of recruitment led to the development of a strong theme around the decarbonisation of social housing. In addition, as the CEIC programme proceeded, the programme dissemination activities and word-of-mouth from previous participants about the type of challenges that had already been addressed through the programme may have shaped the thinking of potential participants in later cohorts. In addition, in our choice of policy framing, considering how the PSOs adopted the high-level WFGA in local policy may have shed more light on what topics were not being seen as innovation opportunities by PSOs. The adoption of a single case study offered some evidence-rich and detailed explanation of how PSOs framed different articulations and understanding of the CE. Yet future research could apply the research questions and methods adopted here to other geographical contexts. It is also worth noting that the CEIC programme due to funding restrictions was not open to the business sector. By including business actors, different articulations and framing of a CE could have emerged.

Despite these limitations, the paper provides an empirical overview of the relevant factors that can reconcile and effectively integrate the social, material and spatial elements into the CE concept. Future research could expand on this empirical frame to test and strengthen the empirical and conceptual evidence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carla De Laurentis

Dr Carla De Laurentis is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Management at the University of West of England. Her main research interests converge around the geography of innovation. She is interested in understanding the mechanisms that lead to an effective diffusion of sustainable practices in the public sector and businesses, investigating why regions show different patterns in the emergence of renewable energy systems and in the implementation of circular economy principles.

Katie Beverley

Dr Katie Beverley is a Senior Research Officer at Cardiff Metropolitan University. Her main research interest is in the strategic use of design to support sustainable innovation in the public, private and third sector.

Nick Clifton

Nick Clifton, PhD, is Professor of Economic Geography and Regional Development at Cardiff Metropolitan University. His main research interests are in regional development, small business and entrepreneurship, networks, business strategy, innovation and creativity. He is an affiliated member of the Centre for Innovation Research (CIRCLE) at Lund University, and member of the UKRI-funded Innovation and Research Caucus.

Emily Bacon

Dr Emily Bacon is a Senior Lecturer in the Value-Based Health & Care Academy, School of Management, Swansea University. Her research focuses on innovation ecosystems, knowledge transfer, and inter-organisational collaboration. She is particularly interested in the implementation of innovation across large-scale ecosystems for both public and private sector organisations.

Jennifer Rudd

Dr Jennifer Rudd is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Management at Swansea University. She has a PhD in chemistry and worked on technological solutions to the climate crisis for over a decade. She moved into social science in 2019 and since then has developed climate change education programmes that have been used internationally and recognised by the European Commission as linking sustainability and digital competencies. She is currently in the Wales Net Zero by 2035 group, commissioned by Welsh Government to create pathways for Wales to become net zero by 2035.

Gary Walpole

Dr Gary Walpole is a Reader in business management at Cardiff Metropolitan University and Director of the Circular Economy Innovation Communities programme, which has developed 250 practitioners from 140 organisations across Wales and created a Circular Economy Innovation eco-system. He specializes in developing innovation capabilities and publishes on firm level and regional innovation. He is passionate about developing individual and organizational capabilities to avert the climate crisis.

Notes

1 The Circular Economy and Innovation Communities programme (CEIC), funded by the Welsh Government and the European Social Fund, aims at working with leaders and managers of public service and third sector organisations in the two city-regions of Cardiff City Region and Swansea Bay City to develop their knowledge and skills in the circular economy and to promote new service solutions to enhance productivity and deliver Circular Economy benefits.

References

- Alhola, K., Ryding, S. O., Salmenperä, H., & Busch, N. J. (2019). Exploiting the potential of public procurement: Opportunities for circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 23(1), 96–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12770

- Anderson, Stuart, Allen, Pauline, Peckham, Stephen, & Goodwin, Nick. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems, 6(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

- Aranda-Usón, A., Portillo-Tarragona, P., Scarpellini, S., & Llena-Macarulla, F. (2020). The progressive adoption of a circular economy by businesses for cleaner production: An approach from a regional study in Spain. Journal of Cleaner Production, 247, Article 119648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119648

- Arsova, S., Genovese, A., Ketikidis, P. H., Alberich, J. P., & Solomon, A. (2021). Implementing regional circular economy policies: A proposed living constellation of stakeholders. Sustainability, 13(9), 4916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094916

- Avdiushchenko, A. (2018). Toward a circular economy regional monitoring framework for European regions: Conceptual approach. Sustainability, 10(12), 4398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124398

- Bauwens, T., Hekkert, M., & Kirchherr, J. (2020). Circular futures: What will they look like? Ecological Economics, 175, Article 106703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106703

- Bradshaw, A., & de Martino Jannuzzi, G. (2019). Governing energy transitions and regional economic development: Evidence from three Brazilian states. Energy Policy, 126, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.05.025

- Bulkeley, H. (2005). Reconfiguring environmental governance: Towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geography, 24(8), 875–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.07.002

- Calafati, L., Froud, J., Haslam, C., Johal, S., & Williams, K. (2021). Meeting social needs on a damaged planet: Foundational economy 2.0 and the careful practice of radical policy (Working Paper No. 8).

- Calisto Friant, M., Reid, K., Boesler, P., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Salomone, R. (2023). Sustainable circular cities? Analysing urban circular economy policies in Amsterdam, Glasgow, and Copenhagen. Local Environment, 28(10), 1331–1369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2023.2206643

- Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Salomone, R. (2020). A typology of circular economy discourses: Navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 161, Article 104917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104917

- Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., & Salomone, R. (2024). Transition to a sustainable circular society: More than just resource efficiency. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 4(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-023-00272-3

- Cheshmehzangi, A., Butters, C., Xie, L., & Dawodu, A. (2021). Green infrastructures for urban sustainability: Issues, implications, and solutions for underdeveloped areas. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 59, Article 127028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127028

- Clifton, N., Kyaw, K. S., Liu, Z., & Walpole, G. (2024). An empirical study on public sector versus third sector circular economy-oriented innovations. Sustainability, 16(4), 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041650

- Clube, R. K. M., & Tennant, M. (2020). The circular economy and human needs satisfaction: Promising the radical, delivering the familiar. Ecological Economics, 177, Article 106772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106772

- Coenen, L., & Morgan, K. (2020). Evolving geographies of innovation: Existing paradigms, critiques and possible alternatives. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 74(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2019.1692065

- Corvellec, H., Stowell, A. F., & Johansson, N. (2022). Critiques of the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 26(2), 421–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13187

- De Laurentis, C., Eames, M., & Hunt, M. (2017). Retrofitting the built environment ‘to save’ energy: Arbed, the emergence of a distinctive sustainability transition pathway in Wales. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 35(7), 1156–1175.

- De Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. (2016). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, 94(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12209

- Diesch, A., & Massari, M. (2024). Hidden gems: The potential of places and social innovation for circular territories in Bogotá. Cities, 144, Article 104645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104645

- Droege, H., Raggi, A., & Ramos, T. B. (2021). Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(6), 1715–1729. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2140

- Dzhengiz, T., Miller, E. M., Ovaska, J., & Patala, S. (2023). Unpacking the circular economy: A problematizing review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 25(2), 270–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12329

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2015). Growth within: A circular economy vision for a competitive Europe.

- Erickson, P., & Tempest, K. (2014). Advancing climate ambition: How city-scale actions can contribute to global climate goals. Stockholm Environment Institute.

- Galarraga, I., Gonzalez-Eguino, M., & Markandya, A. (2011). The role of regional governments in climate change policy. Environmental Policy and Governance, 21(3), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.572

- Gallego-Bono, J. R., & Tapia-Baranda, M. (2022). Industrial ecology and sustainable change: Inertia and transformation in Mexican agro-industrial sugarcane clusters. European Planning Studies, 30(7), 1271–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1869186

- Gibbs, D., & Jonas, A. E. G. (2000). Governance and regulation in local environmental policy: The utility of a regime approach. Geoforum, 31(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00052-4

- Goldthau, A. (2014). Rethinking the governance of energy infrastructure: Scale, decentralization and polycentrism. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.02.009

- Grafström, J., & Aasma, S. (2021). Breaking circular economy barriers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 292, Article 126002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126002

- Green, E., Lannon, S., Patterson, J., Variale, F., & Iorwerth, H. (2019). Understanding the decarbonisation of housing: Wales as a case study. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 329(1), Article 012001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/329/1/012001

- Haase, L. M., Mugge, R., Mosgaard, M. A., Bocken, N., Jaeger-Erben, M., Pizzol, M., & Jørgensen, M. S. (2024). Who are the value transformers, value co-operators and value gatekeepers? New routes to value preservation in a sufficiency-based circular economy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 204, Article 107502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2024.107502

- Hale, J., Jofeh, C., & Chadwick, P. (2022). Decarbonising existing homes in Wales: A participatory behavioural systems mapping approach. UCL Open Environment, 4(1), e047.

- Heurkens, E., & Dąbrowski, M. (2020). Circling the square: Governance of the circular economy transition in the Amsterdam metropolitan area. European Spatial Research and Policy, 27(2), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.27.2.02

- Hobson, K., & Lynch, N. (2016). Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: Radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures, 82, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.012

- Isaksen, A., Trippl, M., & Mayer, H. (2022). Regional innovation systems in an era of grand societal challenges: Reorientation versus transformation. European Planning Studies, 30(11), 2125–2138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2084226

- Jaeger-Erben, M., Jensen, C., Hofmann, F., & Zwiers, J. (2021). There is no sustainable circular economy without a circular society. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 168, Article 105476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105476

- Khan, O., Daddi, T., & Iraldo, F. (2020). The role of dynamic capabilities in circular economy implementation and performance of companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(6), 3018–3033. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2020

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research (pp. 426–450). Sage.

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005

- Kirchherr, J., Yang, N.-H. N., Schulze-Spüntrup, F., Heerink, M. J., & Hartley, K. (2023). Conceptualizing the circular economy (revisited): An analysis of 221 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 194, Article 107001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107001

- Klein, N., Ramos, T. B., & Deutz, P. (2020). Circular economy practices and strategies in public sector organizations: An integrative review. Sustainability, 12(10), 4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181

- Klein, N., Ramos, T. B., & Deutz, P. (2022). Advancing the circular economy in public sector organisations: Employees’ perspectives on practices. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2(2), 759–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00044-x

- Korhonen, J., Nuur, C., Feldmann, A., & Birkie, S. E. (2018). Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. Journal of Cleaner Production, 175, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.111

- Lazarevic, D., Salo, H., & Kautto, P. (2022). Circular economy policies and their transformative outcomes: The transformative intent of Finland's strategic policy programme. Journal of Cleaner Production, 379, Article 134892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134892

- Lazarevic, D., & Valve, H. (2017). Narrating expectations for the circular economy: Towards a common and contested European transition. Energy Research & Social Science, 31, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.006

- Lever, J., & Sonnino, R. (2022). Food system transformation for sustainable city-regions: Exploring the potential of circular economies. Regional Studies, 56(12), 2019–2031. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.2021168

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

- Lowe, B. H., & Genovese, A. (2022). What theories of value (could) underpin our circular futures? Ecological Economics, 195, Article 107382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107382

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Steen, M., Menzel, M.-P., Karlsen, A., Sommer, P., Hansen, G. H., & Normann, H. E. (2019). Path creation, global production networks and regional development: A comparative international analysis of the offshore wind sector. Progress in Planning, 130, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2018.01.001

- Marchesi, M., & Tweed, C. (2021). Social innovation for a circular economy in social housing. Sustainable Cities and Society, 71, Article 102925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102925

- Marsden, T., & Farioli, F. (2015). Natural powers: From the bio-economy to the eco-economy and sustainable place-making. Sustainability Science, 10(2), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0287-z

- Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs. private sector myths. Anthem Press.

- Moreau, V., Sahakian, M., van Griethuysen, P., & Vuille, F. (2017). Coming full circle: Why social and institutional dimensions matter for the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 21(3), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12598

- Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies, 37(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000065442

- Murray, A., Skene, K., & Haynes, K. (2017). The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2

- Newsholme, A., Deutz, P., Affolderbach, J., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2022). Negotiating stakeholder relationships in a regional circular economy: Discourse analysis of multi-scalar policies and company statements from the north of England. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2(2), 783–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00143-9

- Niskanen, J., Anshelm, J., & McLaren, D. (2020). Local conflicts and national consensus: The strange case of circular economy in Sweden. Journal of Cleaner Production, 261, Article 121117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121117

- Padilla-Rivera, A., Russo-Garrido, S., & Merveille, N. (2020). Addressing the social aspects of a circular economy: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(19), 7912. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197912

- Prendeville, S., Cherim, E., & Bocken, N. (2018). Circular cities: Mapping six cities in transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 26, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.03.002

- Pusz, M., Jonas, A. E. G., & Deutz, P. (2024). Knitting circular ties: Empowering networks for the social enterprise-led local development of an integrative circular economy. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 4(1), 201–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-023-00271-4

- Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Rocca, L., Veneziani, M., & Carini, C. (2023). Mapping the diffusion of circular economy good practices: Success factors and sustainable challenges. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(4), 2035–2048. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3235

- Rödl, M. B., Åhlvik, T., Bergeå, H., Hallgren, L., & Böhm, S. (2022). Performing the circular economy: How an ambiguous discourse is managed and maintained through meetings. Journal of Cleaner Production, 360, Article 132144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132144

- Schröder, P., Bengtsson, M., Cohen, M., Dewick, P., Hofstetter, J., & Sarkis, J. (2019). Degrowth within – aligning circular economy and strong sustainability narratives. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 146, 190–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.038

- Schröder, P., Lemille, A., & Desmond, P. (2020). Making the circular economy work for human development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 156, Article 104686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104686

- Swain, Jon, & King, Brendan. (2022). Using Informal Conversations in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 160940692210850. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/16094069221085056

- Tapia, C., Bianchi, M., Pallaske, G., & Bassi, A. M. (2021). Towards a territorial definition of a circular economy: Exploring the role of territorial factors in closed-loop systems. European Planning Studies, 29(8), 1438–1457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1867511

- Tsatsou, A., Frantzeskaki, N., & Malamis, S. (2023). Nature-based solutions for circular urban water systems: A scoping literature review and a proposal for urban design and planning. Journal of Cleaner Production, 394, Article 136325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136325

- Uyarra, E., Ribeiro, B., & Dale-Clough, L. (2019). Exploring the normative turn in regional innovation policy: Responsibility and the quest for public value. European Planning Studies, 27(12), 2359–2375. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1609425

- Van Buren, N., Demmers, M., van der Heijden, R., & Witlox, F. (2016). Towards a circular economy: The role of Dutch logistics industries and governments. Sustainability, 8(7), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8070647

- van der Have, R. P., & Rubalcaba, L. (2016). Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Research Policy, 45(9), 1923–1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.010

- Vergragt, P. J., Dendler, L., de Jong, M., & Matus, K. (2016). Transitions to sustainable consumption and production in cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.050

- Veyssière, S., Laperche, B., & Blanquart, C. (2022). Territorial development process based on the circular economy: A systematic literature review. European Planning Studies, 30(7), 1192–1211. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1873917

- Vickers, I., Lyon, F., Sepulveda, L., & McMullin, C. (2017). Public service innovation and multiple institutional logics: The case of hybrid social enterprise providers of health and wellbeing. Research Policy, 46(10), 1755–1768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.08.003

- Wahlund, M., & Hansen, T. (2022). Exploring alternative economic pathways: A comparison of foundational economy and Doughnut economics. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 18(1), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2030280

- Weber, E. P., & Khademian, A. M. (2008). Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public Administration Review, 68(2), 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00866.x