Abstract

By drawing from theories of imperialism and power, this paper examines the agential and structural forms of the EU’s power projection in the world with a particular focus on the African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries. As evident in the areas of trade, agriculture, energy and security, the EU operates within a hierarchical, centre-periphery relationship with these countries and projects forms of power such as coercion, mobilization of bias, manipulation, exploitation but also attraction, features that are all associated with imperialism. This has broader implications on how we understand the EU as a polity as well as how power is embedded in the concept of imperialism.

1. Introduction

In a world of established (i.e. USA, Russia and China) and emerging (i.e. India, Brazil and Japan) superpowers, the EU is called upon, by its own citizens, not only to promote its interests but to do so in a way that is in sync with the proclamations of its founding fathers, such as Jean Monnet, but also contemporary leaders who see the Union as ‘a force for good’Footnote 1 in the world committed to ethical and moral values. The Union’s foreign policy objectives in the Maastricht Treaty (1993) clearly state such objectives: ‘to develop and consolidate democracy, the rule of law, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms’ (Article J.1), foster ‘the sustainable economic and social development of the developing countries, and more particularly the most disadvantaged among them’; ‘the smooth integration and gradual integration of the developing countries into the world economy’; and ‘the campaign against poverty in the developing countries’ (Article 130u). ‘Human rights … are the foundations of freedom, justice and peace in the world … The Union’s headway towards integration is paralleled in the field of human rights. In a world where human rights … continue to be violated daily, the Union’s commitment to human rights is continuously being translated into action’.Footnote 2 ‘The Union shall uphold and promote its values and interests. It shall contribute to peace, security, the sustainable development of the Earth, solidarity and mutual respect among peoples, free and fair trade, eradication of poverty and the protection of human rights, in particular the rights of the child, as well as to the strict observance and the development of international law, including respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter’.Footnote 3 These are objectives and declarations that reveal a superpower that has set for itself, high moral and ethical standards in its dealings with the world. And, it also reveals an ‘exceptional’ power that defines itself by juxtaposing its behaviour with other superpowers in the world, as for example, the USA, China and Russia. Indeed, the EU’s portrayal of its sui generis qualities is part of its existential narrative and its unique European history. Yet, to what extent is the EU really unique or sui generis when it comes to the nature of its power projection in the world? Is there a consistency between the EU’s internal and external praxis and discourse, or is there a ‘rhetoric-reality’ gap in its foreign policy?

The starting point of this analysis is the conceptualization of the EU as an Empire. Manuel Barroso’s (2007)Footnote 4 comment that the EU is a ‘non-imperial Empire’ has reignited debates regarding the nature of the EU’s power projection in the world. More particularly, it has awakened the ghosts of Europe’s imperial past, which has more often than not been associated with negative behaviour such as aggression, control, domination and exploitation. It has raised questions as to whether Europe has done away with this imperial past or whether it continues to operate in the ‘shadows of empire’ with imperialism deeply ingrained in the Union’s character shaping its behaviour in contemporary politics. This decade old debate has taken different shapes and forms as evident from works which see the EU as a ‘neo-medieval’ (Weaver 1997, Zielonka Citation2006), ‘gradated’ (Diez and Whitman Citation2002), ‘soft’ (Hettne and Soederbaum Citation2005), ‘neo-liberal’, ‘cooperative’ and ‘post-modern’ (Cooper Citation2007), ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘post-imperial’ (Beck and Grande Citation2007), ‘capital’ (Wood Citation2005), ‘in denial’ (Chandler Citation2006), a ‘quasi nineteenth century’ (Anderson Citation2007, Behr Citation2007), ‘hegemonic’ (Diez Citation2005, Haukkala Citation2008), ‘federalizing’ (Gravier Citation2011) or ‘accommodating’ and ‘assimilating’ (Marks Citation2012) empire. This debate has taken place in the backdrop – and in contrast – to the more popular conceptualizations of the EU as a ‘civilian’ (Duchene Citation1972), ‘soft’ (Nye Citation1990), ‘normative’ (Manners Citation2002) and ‘ethical’ (Aggestam Citation2008) power which are terms associated with positive behaviours such as persuasion and attraction. Yet, as with other works that have sought to understand the EU as a global actor (Bretherton and Vogler Citation1999, Hill and Smith Citation2005, Elgstrom and Smith Citation2006, McCormick Citation2006, Soderbaum and Langehove Citation2006, Sjursen Citation2007, Laidi Citation2008, Telo Citation2009, Toje Citation2010, Whitman Citation2011), there has not been a systematic utilization of the major theoretical and conceptual understandings of power (Dahl Citation1957, Bachrach and Baratz Citation1962, Weber Citation1978, Lukes Citation2005) in order to understand the nature and forms of the EU’s power projection in the world. For example, a recent edited volume (Gravier and Parker Citation2011) has comprehensively dealt with the various dimensions of the internal structure of the EU empire, including a comparative perspective with other empires such as the US, but did not theoretically engage with the external nature of the EU’s imperial power projection. More broadly, there has been little attention given to understanding how power is embedded in the notion of imperialism and how the different faces of power manifest themselves through imperialism. This paper aims to contribute towards filling these gaps in the literature by examining the nature of the EU’s power projection towards the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries.Footnote 5 It will combine a theoretically grounded ‘empirical framework analysis’ with ‘discourse and discursive analysis’ in its methodology, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The ACP countries are selected as a case study, as it is the author’s assertion that Europe’s contemporary imperial tendencies are nowhere more obvious than in its relationship with Africa. Also, in light of the fact that the ACP countries are the least developed of the world’s continents, it is an important testing ground for the overall credibility and ethics of European rhetoric and action.

2 Conceptualizing and theorizing imperialism and power

Imperialism is an essentially contested concept – it means different things to different people and there is no absolute agreement on what constitutes an ‘empire’. ‘Conceptual stretching’ (Sartori Citation1970) is evident in this case, as there is a propensity to define ‘everything as empire’ (Motyl Citation2001). However, some common patterns can be distinguished in the literature when it comes to the definition of the concept. For example, from a Marxist perspective imperialism has been associated with ‘the expansion of capital’ (Lenin Citation1916, Arendt Citation1951, Weber Citation1978, Waltz Citation1979, Harvey Citation2003) while others associate it with ‘coercion’ (Hurrell Citation2005a, Chandler Citation2006), ‘exploitation’ (Emmanuel Citation1972, Caporaso Citation1974; Chandler Citation2006), ‘force’ (Schumpeter Citation1951, Chandler Citation2006), ‘subordination’ (Mathew Citation1968), ‘domination’ (Cohen Citation1974, Motyl Citation2001, Chandler Citation2006), ‘control’ (Robinson Citation1972, Cohen Citation1974, Doyle Citation1986, Lake Citation2001, Hurrell Citation2005a), ‘inequality’ (Caporaso Citation1974), ‘dependence’ (Caporaso Citation1974, Cohen Citation1974, Chandler Citation2006), ‘asymmetry’ (Cohen Citation1974), with ‘hierarchical’ and ‘centre-periphery’ structures (Galtung Citation1971, Emmanuel Citation1972, Lake Citation2001, Motyl Citation2001, Chandler Citation2006) and ‘with the reversal of power relations between states’ (Morgenthau Citation1948). Finally, others identify imperialism when the ‘objects of imperialism’ perceive that there are ‘negative consequences’ stemming from their relations with the imperialist centre (Barnett and Duvall Citation2005, p. 63). Since, imperialism is closely associated – though often confused – with ‘neo-colonialism’ and ‘hegemony’ it is useful for comparative purposes to provide a similar term association. Thus, neocolonialism has been associated with ‘control’ (Crozier Citation1964, Nkrumah 1965, Hodder-Williams Citation2001), ‘inequality’ (Hodder-Williams Citation2001), ‘exploitation’ (Nkrumah 1965, Hodder-Williams Citation2001), ‘domination’ (Crozier Citation1964); whereas hegemony has been associated with ‘coercion’ (Gramsci Citation1971, Zahran and Ramos Citation2010), ‘domination’ (Cox Citation1987, Arrighi and Silver Citation1999, Joseph Citation2002, Cerny Citation2006), ‘consent’ (Gramsci Citation1971, Cox Citation1987, Joseph Citation2002, Cerny Citation2006, Zahran and Ramos Citation2010) and ‘leadership’ (Gramsci Citation1971, Cox Citation1987, Arrighi and Silver Citation1999, Cerny Citation2006, Zahran and Ramos Citation2010). A conceptual map comparing the three terms is provided below in Table :

Table 1. Terms associated with imperialism, neocolonialism and hegemony.

An equally great number of perspectives exist in theorizing imperialism. Three major strands of theories are those based on the insights of conservative scholars such as Disraeli in 1878Footnote 6 , Rhodes in 1888Footnote 7 and Kipling in 1899Footnote 8 ; liberals such as Hobson (Citation1902) and Angell (Citation1939); and Marxists such as Lenin (Citation1916), Luxemburg (Citation1951), Bukharin (Citation1972), Harvey (Citation2003) and Wood (Citation2005). The three theories agree that under-consumption at home leads to aggressive expansion of capital abroad to reinvigorate saturated domestic markets. They mainly disagree in regard to the value and necessity of imperialism, with the conservatives arguing that imperialism is in fact necessary and valuable for the metropolis, while the Marxists are on the opposite side of the spectrum. Other perspectives that draw from the three major theories of imperialism are those of dependency and underdevelopment scholars such as Baran (Citation1957), Frank (Citation1967), Galtung (Citation1971), Emmanuel (Citation1972), Amin (Citation1972), Wallerstein (1974) and Rodney (Citation1982) who view and examine the world in terms of centre-periphery relations, with the periphery dependent upon and exploited (mainly in terms of trade) by the centre, as well as politico-economic theories brought forth by Morgenthau (1948) and Cohen (Citation1974) who view imperialism as military conquest, economic exploitation and displacement of one culture by another. Finally, Schumpeter’s (Citation1951) socio-psychological theory views imperialism as an objectless expansion (a learned behaviour) driven by warlike elites.

When it comes to power, it was Machiavelli and Hobbes that provided the foundations in modern thinking about this concept and in more contemporary times, it was Weber (Citation1947), Dahl (Citation1957), Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1962, Citation1963), Lukes (Citation1974, Citation2005), Giddens (Citation1979) and Nye (Citation1990) that dissected and analysed the concept’s various forms and components.Footnote 9 According to Weber (Citation1947), power is defined ‘as the probability that an actor within a social relationship would be in a position to carry out his will despite resistance to it’; for Dahl (Citation1957) it is ‘power over’ or ‘the ability to make somebody do something that otherwise he/she would not have done’. For Lukes (Citation2005, p. 37) it is when ‘A exercises power over B when A affects B in a manner contrary to B’s interests’. Lukes emphasizes ‘interests’ as well as ‘responsibility’ and the role of ‘agency’: ‘the point … of locating power is to fix responsibility for consequences held to flow from the action, or inaction, of certain specifiable agents’(2005, p. 58). In contrast, Giddens (Citation1979, p. 93) emphasizes the role of ‘structure, arguing that the enduring relations in which actors participate determine their ability to exercise power, defining the latter ‘as the capability to secure outcomes where the realization of these outcomes depends on the agency of others’.Footnote 10 Similarly, Hayward (Citation1998, p. 12) sees power as ‘faceless’, whereby ‘power’s mechanisms are best conceived, not as instruments powerful agents use to prevent the powerless from acting freely, but rather as social boundaries that, together, define fields of action for all actors … and fields of possibility … facilitating and constraining social action … and whose mechanisms consist in laws, rules, norms, customs, social identities, and standards that constrain and enable inter- and intra-subjective action’.

Drawing from this literature, one can distinguish three major forms of power. Dahl’s conceptualization constitutes the first dimension of power (i.e. overt), whereby power involves a focus on behaviour in the making of decisions on issues over which there is an observable conflict of (subjective) interests, seen as express policy preferences, revealed by political participation. In this case, A participates in the decision-making of B in a manner contrary to B’s interests. Behaviours associated with this first dimension of power include those of ‘coercion’Footnote 11 , ‘force’Footnote 12 , ‘control’, ‘domination’ and ‘exploitation’. In international relations, an example of this first dimension of power can be the use of military force or economic sanctions by an entity A (state or regional organization), over entity B (state or regional organization) to force entity B to change its domestic or foreign policy position on a certain issue (e.g. US military invasion of Iraq; NATO bombings of the Milosevic regime; NATO bombings of Gadaffi’s regime; EU economic sanctions on Syria and Iran).

Bachrach and Baratz (Citation1962, Citation1963) developed the second dimension of power (i.e. covert), which involves a qualified critique of the behavioural focus of the first dimension of power and it allows for consideration of the ways in which decisions are prevented from being taken on potential issues over which there is an observable conflict of (subjective) interests seen as embodied in expressed policy preferences and sub-political grievances. In this case, ‘A devotes energies in creating or reinforcing social and political values and institutional practices that limit the scope of the political process to public consideration of only those issues which are comparatively innocuous to A’ (Bachrach and Baratz Citation1962, p. 948). Schattschneider (Citation1960, p. 71) referred to this form of power as ‘mobilization of bias’: all forms of political organization have a bias in favour of the exploitation of some kinds of conflict and the suppression of others because organization is the mobilization of bias. Some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out’. Thus, behaviours associated with this second form of power, include not only what Bachrach and Baratz later referred to as ‘agenda-setting’ (1970, p. 8) but also ‘inducement’, ‘persuasion’ and ‘encouragement’. In international relations, an example of this second dimension of power is when entity A (state or regional organization) devotes energies to designing and establishing international institutions that are in tune with the interests and values of A at the expense of the interests and values of B (state or regional organization). Consider for example, how the USA and its allies dominated the agenda as far as the establishment of the rules, regulations and voting power in the United Nations, the IMF and the World Bank (Hurrell Citation2005b, p. 54), institutions with clearly Western characteristics, structurally designed and organized to favourably bias the interests of these superpowers, often at the expense of those developing nation-states, which had less of a say in the institutional build up of these organizations. Another example can be, when a powerful regional bloc such as the EU (as we will observe later) sets the agenda of trade negotiations vis-à-vis weaker regional blocs in the developing world.

Lukes (1974, 2005) developed the third dimension of power (i.e. latent), which involves a thoroughgoing critique of the behavioural focus of the first two dimensions and which allows for consideration of the many ways in which potential issues are kept out of politics, whether through the operation of social forces and institutional practices or through individuals’ decisions. This moreover, can occur in the absence of actual, observable conflict, which may have been successfully averted – though there remains here an implicit reference to potential conflict. In other words, Lukes believes that it is highly unsatisfactory to suppose that power is only exercised in situations where there is overt or covert conflict. In fact, ‘the most insidious use of power is to prevent such conflict from arising in the first place’ (2005, p. 27). ‘Power can be at work, inducing compliance by influencing desires and beliefs, without being intelligent or intentional’ (Lukes Citation2005, p. 136). In this case, ‘A may exercise power over B by influencing, shaping or determining his very wants’ and ‘A prevents the formation of grievances from B by shaping its perceptions, cognitions, and preferences in such a way as to ensure the acceptance of B’s role in the existing order’. (2005, p. 27). Here, A affects B simply by its existence, by inactivity, by a lack of decision and intention. A may exercise power over B without being aware that it is doing so or of its consequences. Furthermore, B may not be aware of its ‘real interests’, may not express them and may be under a state of ‘false consciousness’, i.e. when entities (states or people) ‘have systematically distorted beliefs about the social order and their own place in it that work systematically against their interests’ (Lukes Citation2010, p. 15). Footnote 13 In other words, for Lukes, power can also be exercised by preventing the rise of grievances – by shaping perceptions, cognitions and preferences in such a way as to secure the acceptance of the status quo, since, no alternative appears to exist or because it is seen as natural or unchangeable or indeed beneficial. Non-behaviours associated with this third form of power include ‘attraction’ (Munuera Citation1994) and ‘influence’Footnote 14 , but may also contain certain hidden and subtle coercive elements such as ‘manipulation’Footnote 15 (Lukes Citation2005) and ‘representational force’Footnote 16 (Mattern Citation2007). In this third dimension of power, you have inaction and non-behaviour and any conflict that exists is ‘latent’ because those subjected to power do not express or even remain unaware of their interest. This means that the ‘real interests’ of B are very difficult to trace, because those concerned either cannot express them or are unable to recognize them. These two points, i.e. inaction and interests, are areas of critique of Lukes’ argument for some scholars (e.g. Bradshaw Citation1976, Young Citation1978, Lorenzi Citation2006), who point out that as much as it is difficult to find an empirical causal link between inaction and its consequences, it is also difficult to establish empirically the distinction between the ‘real’ and ‘subjective’ interests (a Marxist theme) of the entity which is subject to power. Lukes (Citation2005, p. 146) responded to the latter critique in particular, suggesting that there is an empirical basis for identifying ‘real’ interests, i.e. ‘when B exercises choice under conditions of relative autonomy and, in particular, independently of A’s power, e.g. through democratic participation’. And while Lukes rejected the Marxist roots of his argument, with, among other things, his emphasis on ‘agency’ rather than ‘structure’, one may add a further critique and argue that his third non-behavioural form of power significantly reminds us of the ‘invisible’ power that is exerted by any given ‘structure’ and the numerous ways that it constrains the actions of its various ‘agents’. In other words, the power of attraction may ultimately rest on the way in which the ‘structure’ makes A attractive to B and the ways in which A may have contributed in designing and reproducing that ‘structure’, as well as the ways B failed to contribute to that design or transform that ‘structure’. Thus, in international relations, an example of this third dimension of power may be when an entity A (state or regional organization) has a particular influence on an entity B (state or regional organization) in such a way that it shapes the preferences and values of entity B in ways that may even be against the interests of B. The EU’s so-called ‘power of attraction’ towards countries of Central and Eastern Europe that voluntarily sought to apply for EU membership may represent one such example of power. In that case, the EU did not act to invite these countries for membership but rather the EU’s model and mere existence shaped the preferences and perceptions of CEEC countries, in such a way that they believed that EU membership was the only beneficial strategic option to follow. At the same time, there may have been a latent or implicit conflict, involved here in the form of the ‘threat of exclusion’ from the benefits of the common market that these CEEC countries encountered should they have decided to opt out of the option of membership. Also, the EU’s rhetoric about being a polity of democracy and human rights may have indirectly induced these countries to want to be part of the EU in order to avoid being labelled as ‘undemocratic’. In other words, certain hidden coercive forces related to the CEEC’s countries application for EU membership may have been at play. At the same time, and taking into consideration the main critics of Lukes on the point of inaction and interests, it is difficult to establish empirically whether the EU’s inaction and mere existence acted as a pole of attraction for the CEEC countries or that those countries sought the membership route while operating under ‘false consciousness’ and without knowing what their real interests were on the issue. Also, there is difficulty in empirically measuring with accuracy how the international structure shaped the decision of those CEEC countries to apply for EU membership. In order to do so, one would have to examine whether the CEEC countries acted, as Lukes noted, within a framework of democracy and autonomy within the international system something which is not within the scope of this paper.

It is precisely within this broader discourse of the second and third dimensions of power that the much discussed notions of ‘civilian’ (Duchene Citation1972), ‘soft’ (Nye Citation1990) and ‘normative’ (Manners Citation2002) power fall under. From a conceptual and analytical point of view, all three notions are similar and neutral despite efforts to separate them or emphasize their positive connotations. Scheipers and Sicurelli (Citation2008, p. 609) argue that all three notions can be used for both ‘good and bad’ purposes, indicating when referring to normative power that ‘the ability to promote norms internationally may have either morally desirable or undesirable implications both for the norm promoter and for the receiver of these norms’. Table provides a conceptual map of the three forms of power, taking into consideration these concepts including that of imperial power Europe.

Table 2. The EU’s three dimensional power projection in the world.

Utilizing the existing definitions of imperialism and the terms associated with these (see Table ) as well as employing the three dimensions of the power model (see Table ), this paper defines imperialism as:

A hierarchical, centre-periphery relationship of asymmetry, inequality and dependence in inter-state relations maintained by coercion, exploitation and control (sovereign or not), expressed in overt, covert and latent ways, and which is viewed as such by the objects of imperialism.

In this sense, and under this definition, imperialism can be projected in all three forms of power, in behavioural and non-behavioural ways.

3 The imperial nature of the EU’s relationship with the ACP countries

The EU’s imperial relationship with the ACP countries is evident in two dimensions, better understood in terms of agency and structure. This dichotomy is important and for valid reasons – it essentially prompts us to consider with equal seriousness the role of both actors (agents) and context (structure) in our effort to comprehensively understand any socio-political phenomenon or political reality. Wendt (Citation1987, p. 338) made this point clear: ‘human beings and their organizations (institutions, states, regional organizations, etc.) are purposeful actors whose actions help reproduce or transform the society in which they live; b) society is made up of social relationships, which structure the interactions between these purposeful actors. Taken together, these truisms suggest that human agents and social structures are, in one way or another, theoretically interdependent or mutually implicating entities’. The key question that arises in this debate, is the respective importance of agency and structure – the simple answer is that both elements are equally important. Structures do constrain the behaviour of agents, but structures also depend on agents for their reproduction or transformation. The agency-structure theorem is relatively absent in discussions about the EU’s global role, which is strange given that it can provide us with important insights. One of those insights is the understanding that in any power relationship (including that of imperialism) there are both agential and structural dimensions. In the case of the EU–ACP relationship, for example, we can observe below that both agency and structure have played an important role in shaping that relationship.

3.1 Agential dimensions of imperialism in the EU–ACP relationship

The agential dimension in the EU’s imperial relationship with the ACP countries is evident in the areas of trade, agriculture, energy and security. It is more particularly evident in the EU’s behaviour towards the ACP countries while negotiating key agreements such as the Yaoundé (1963) and Lomé (1975) Conventions, the Cotonou Agreement (2000, 2005), the Africa–EU Partnership for Energy (2007) and the more recent Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) (Citation2008). The EU is, of course, not a single agent – it consists of Member States, EU institutions and interests groups – altogether, however, they project a behaviour that is formulated after negotiation and aggregation of the interests and input of those various actors from the European continent. Thus, in the majority of African’s views, Europe or the EU is represented by the totality of these actors and it is thus valid to analyse the Union as such a single entity. Nonetheless, one can observe that the key European actors driving EU policies in Africa are former colonial power member states such as Britain, France, The Netherlands, Italy and Belgium; EU institutions such as the European Commission’s DGs of external relations, trade, energy, agriculture, development and aid; multinational oil, gas and mining companies such as Royal Dutch Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, Anglo-American, Rio Tinto and BHP Billington; and European agricultural and trade unions and the European defence industry.

At first glance, just like the EU’s broader foreign policy objectives as outlined in the Maastricht Treaty and the European Security Strategy (2003), EU–ACP agreements contain many normative objectives and declarations. For example, the revised Cotonou Agreement (2005), in particular Article 2, outlines several fundamental principles that guide relations between the EU and the ACP: (a) equality of the partners and ownership of the developing strategies; (b) participation, apart from central governments and other actors from all sections of society including civil society and the private sector; (c) dialogue between all involved parties, as central to partnership and cooperation; and (d) differentiation and regionalization, with emphasis on the partner’s level of development, needs and performance. Furthermore, Articles 8–11 of the Agreement are specifically devoted to promoting democracy, human rights, good governance and security through conflict prevention and resolution. For example, Article 9 states that ‘respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms, including respect for fundamental social rights, democracy based on the rule of law and transparent and accountable governance are an integral part of sustainable development’. And Article 11 indicates that ‘the parties shall pursue an active, comprehensive and integrated policy of peace building and conflict prevention and resolution within the framework of the Partnership’. These principles ‘shall underpin the ACP–EU Partnership, and shall underpin the domestic and international policies of the Parties and constitute the essential elements of this Agreement’ (Article 9). Similarly, the European Commission’s Strategy for Africa (2005) refers to the need to form a relationship with Africa based on ‘equality, partnership, ownership, subsidiarity and solidarity’ as well as ‘reciprocity’ which is aimed at ‘poverty eradication and sustainable development’. At the same time, other EU declarations – outside of the framework of the EU–ACP Agreements – reveal the more realist than normative objectives of the Union. The Commission’s DG external trade states: ‘More than ever, Europe needs to import to export. Tackling restrictions on access to resources such as energy, metals and scrap, primary raw materials including certain agricultural materials, hides and skins must be a high priority’ (7). ‘As global demand increases and Europe becomes more dependent on external energy sources … we should seek to improve transparency, governance and trade in the energy sector in third countries through non-discriminatory conditions of transit and third party access to export pipelines infrastructure’ (7). Also, ‘the EU has a strategic interest in developing international rules and cooperation on competition policies to ensure European firms do not suffer in third countries from unreasonable subsidization of local companies or anti-competitive practices’ (8).Footnote 17 And a British think tank with close links to the Commission’s DG External Trade, which has been headed successively by two former British politicians, refers to the need to ‘pursue aggressively market access modelled on the US approach’ in regions such as the ACP, ‘both bilaterally and in the WTO’.Footnote 18 As we will observe below, the EU’s normative declarations are vaguely implemented on the ground whereas its realist ones dominate its policies, agenda and behaviour towards Africa.

The type of behaviour expressed by the EU is particularly evident in the negotiations of the Economic Partnership Agreements. Not only elements such as coercion, manipulation, but also attraction are particularly evident. Attraction is evident as the ACP countries are driven to negotiate trade and other related agreements with the EU in order to have access to its lucrative markets and the global trade market as well as to join global trade forums such as the WTO. More particularly, the ACP countries recognize that sustained growth in Africa requires implementing policies to expand exports away from dependence on a narrow range of (unprocessed) primary commodities (Commission for Africa Citation2010). Trade preferences can play an important role in this, yet this implies that only appropriately designed EPAs which takes into account the nature and structure of domestic African economies could lead to these increased ACP exports. Here, one can observe that the EU’s third dimensional power projection towards the ACP countries is more structural and non-behavioural. It is possible that the ACP countries are attracted to negotiating these EPA agreements, either because the structure of the international financial system compels them to do so, or because they are unaware of their ‘real interests’ and are operating under ‘false consciousness’. Lukes indicated that only when B is operating under conditions of democracy and autonomy, he is aware of his ‘real interest’ – however, in the case of Africa, one can observe (further in the discussion of Gultung’s structural imperial model) that the ACP countries are operating under conditions of dependence and asymmetry (rather than democracy and autonomy) when it comes to trade with the EU. Also, studies (e.g. Hurrell 2005b) question the lack of democracy in the governance of global financial institutions such as the IMF and the WTO, whereby polities such as the US and the EU dominate the design and rules of these institutions in contrast to developing countries, such as the ACP, which have little say. But there may also be another important explanation for why the ACP countries are willing to negotiate and sign these agreements. These countries are not monolithic or unitary agents, rather they consist of different actors, more particularly of African elites and the rest of the population, including civil society, which often have diverging ‘real interests’ between them. For example, African elites which are negotiating these agreements may see vast and direct benefits from their adoption as a way to empower their privileged position in society, despite the fact that they recognize that these agreements do not meet the development needs of the wider African population. Studies indeed indicate the active role that African elites have played, in close cooperation with elites of the North, in advancing the process of capitalist expansion and neoliberal economic models in Africa through international institutions (e.g. World Bank, WTO, IMF, G8, G22, the EU, UN, etc). Harris and Robinson (Citation2000, p.2) point out that ‘the developing world’s elites have been inexorably drawn into this process, with the leading capitalist groups in the Third World having trans-nationalized by integrating into global circuits of accumulation through a variety of mechanisms, ranging from subcontracting for global corporations, the purchase of foreign equity shares, mergers with corporations from other countries, joint ventures and increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) abroad of their own capital’. Taylor and Nel (Citation2002, p. 169) also indicate that African elites, far from stopping neoliberal economic expansion are actually ‘pushing for greater integration into the global capitalist order, but on renegotiated terms that clearly favour externally orientated Southern elites’ … ‘while leaving the rest of the continent to swim or sink, as it were, with the globalization current’ (166). In other words, it is important to indicate here, the role and responsibility of African agency, more particularly African elites, in engaging, negotiating and signing such trade agreements that may not benefit the wider African population and which may ultimately sustain and reproduce the asymmetric imperialist structures between Africa and the EU. Responsibility, however, as discussed further, arguably also lies with EU elites who have seemingly chosen to deal and negotiate almost exclusively with African elites – in a form of a global elite solidarity – marginalizing and ignoring the needs and recommendations of an already structurally weak African civil society, which struggles to make its voice heard and shape the policy-making process of the modern African state.

Coercion and manipulation have been evident in the frameworks set up to negotiate the EPAs, as well as the subsequent pressure from the EU on the ACP countries to sign the agreements. Firstly, the EU insisted that the EPAs were to be concluded not with the ACP group as a whole, but with six regions within the group. Also, no country could negotiate within more than one region. Since some countries in Africa are members of more than one regional organization, they were forced to choose between these groupings. By insisting on moving negotiations to the regional level, the EU excluded the possibility of more concerted action on behalf of the group as an entity (Slocum-Bradley Citation2007, p. 365). Since the regional groups are smaller, they have less power to negotiate an agreement that favours the interests of the developing countries. Secondly, the principle upon which the EPA agreements is based and which has been promoted by the EU as fait accompli – citing WTO rules – is that of ‘reciprocity’ in trade which essentially entails the elimination of all tariffs or other restrictions between trading countries. While this principle may be beneficial among countries with symmetrical wealth and development, it is not for those poorer countries or regions, such as the ACP bloc, whose goods and services cannot compete with those of more advanced polities such as the EU. Moreover, intense EU pressure was put on the ACP countries to sign the EPAs insisting on a December 2007 deadline (negotiations began in Sept. 2002). In this case, the EU insisted that the deal must be concluded in order to ensure WTO compliance with Peter Mandelson and Louis Michel, the EU’s Commissioners for trade and development, insisting that if the EPAs were not agreed by the end of the year they will have to ‘fall back on the EU’s default preference scheme’, meaning higher tariffs for the ACP countries.Footnote 19 The ACP countries, through their parliamentary representatives, repeatedly called for an extension of the deadline asking the Commission to ‘cease pressuring the ACP bloc’ to sign the agreements and allow more time to revise them in order to fulfil their development needs and aspirations.Footnote 20 The EU insisted on its earlier argument indicating the need to make the EU–ACP trade relations compatible with WTO rules. In fact, the EU’s argument of no ‘credible alternative’ was untrue in that the EU did have alternative choices but lacked political will. For example, the EU could seek to extend its WTO waiver or fine-tune the enhanced general system of preferences (often called GSP+) to allow all ACP countries to retain market access equivalent to that of the present. Even if a country brought immediate proceedings against the EU and the ACP, the glacial speed of WTO proceedings would allow ACP countries more time to assess their needs and the deals on the table. Forcing the pace of negotiations could only disadvantage the weakest player and it is a form of threat, bullyingFootnote 21 and manipulation. ACP officialsFootnote 22 also indicate how the EU sets the agenda and controlled the content and pace of negotiations with regard to Cotonou and the EPA agreements, allowing little room for debating clauses that were objectionable to the ACP countries such as ‘tariff liberalization’, ‘export tax’, ‘rules of origin of cumulation’ and the ‘SGP regime’, while also taking as de facto that the neoliberal economic model is the ‘starting point’ and ‘aspiration’ of the ACP countries. In that regard, it was argued that these agreements were ‘unfair and untenable’ and pressuring the ACP countries to sign them was essentially ‘holding poor countries to ransom’.Footnote 23 The Council of the 76 ACP Trade Ministers issued a statement deploring ‘the enormous pressure that has been brought to bear on the ACP states by the European Commission to initial the interim trade arrangements’ and that ‘the EU’s mercantilist interests have taken precedence over the ACP’s developmental and regional integration interests’. Footnote 24 The Assembly of the African Union stated: ‘Political and economic pressures are being exerted by the European Commission on African countries to initial Interim Economic Partnership Agreements’.Footnote 25 Also, President Wade of Senegal argued that Europe was trying to push Africa ‘into a straightjacket that doesn’t work’.Footnote 26 And Malawi’s President Mutharika accused the EU of ‘imperialism’, saying it was punishing countries that resisted the EPAs by threatening to withhold aid from the European Development Fund (EDF).Footnote 27

The EU’s policy to link future development funds to ACP countries to the condition of signing the EPAs is a further element of coercion and manipulation. In particular, the EU engineered the convergence of the final stages of the EPA negotiations with the programming of the 10th European Development Fund (EDF). This tactic, aimed to use the much-needed development aid to Africa in order to ‘window-dress’ or ‘sugar coat’ the Economic Partnership Agreements. According to Goodison (Citation2007, p. 148), this constituted an ‘institutional bribery’ with ACP finance ministers being ‘encouraged’ to ‘put the arm’ on reluctant trade ministers who remained unconvinced of the economic value of the proposed EPAs, which in the end resembled the Union’s ambitious bilateral agreements with some added ‘development assistance sweeteners’. Hurt (Citation2003, p. 174) also argues that the EU has deliberately put WTO and IMF rules at the centre of the debate portraying them as ‘fixed and immutable rather than the political construct that they are’, while Storey (Citation2006, p. 343–344) points out that the EU acted as ‘an old fashioned realpolitik’ promoting neoliberal governance at the expense of the development needs of the ACP countries. Slocum-Bradley and Bradley (Citation2010, p. 45) concludes that the process that the European Commission used to steer the ACP countries towards compliance with the EPAs is not in accordance with its vows to respect ACP sovereignty and promote ownership of adopted policies and practices.

The EU used similar coercive and manipulation tactics in its energy policy towards Africa. The Union, whose overall dependence on energy imports stands at 50% – has integrated its energy security interests in energy-rich Africa (i.e. oil, gas and uranium) into its foreign policy with the establishment of the Africa–EU Energy Partnership (2008). It renewed its interests in African energy imports, in November 2006, following its failure to reach agreement with Russia over a new cooperation and partnership agreement that would formalize their energy relationsFootnote 28 as well as increasing competition with other energy-seeking powers such as the US, China and India. Yet, this strategy has been one-sided, serving the interests of the EU and giving little attention to the continent’s energy needs, i.e. improving access to energy in rural areas and helping African states develop alternative energy sources. Youngs (Citation2009, p. 134) reveals that African governments have admonished European government hypocrisy in talking of new ‘jointly-owned’ energy partnerships, while they pour new funds into their own efforts to develop alternatives to oil and gas. They also accuse the EU of pushing for market liberalization as an instrumental fillip to their own supplies when combating local energy poverty as more a question of state intervention and redistribution. Muller (Citation2007, p. 16) points out how local activists are discontent as they see the European Investment Bank funding massive hydro-electricity plants (e.g. the Great Inga Dam in Congo), which have serious negative effects on the health and livelihoods of the surrounding populations (e.g. loss of habitat and fishing grounds). Human rights activists point out that European banks and firms are involved in systematic bribery of African leaders and local officials in return for access to resources. For example, French/Elf executives bribed compliant leaders in Gabon, Guinea, Angola and Congo-Brazzaville in return for protecting France’s supply of cheap petrol.Footnote 29 In Congo, France/Elf was accused of plotting a coup in 1992 to oust a government that had come to question the terms of oil contracts (Medard Citation1999, p. 8). Similarly, Angola’s oil riches have been appropriated by local elites with the complicity of foreign banks, often brokered by arms dealers connected to European governments and oil companies. Reports have also surfaced that in the period 1993–1998, French government officials appear to have unofficially assisted the oil for weapons trade in Angola, as production declined in its former dependencies Gabon and Cameroon.Footnote 30 In Angola specifically, the oil industry has been a classic ‘enclave’ sector since independence, cordoned off from the country’s conflict and replete with Portuguese advisors (Youngs Citation2009, p. 128). In the Nigerian Delta, the Dutch-British oil company Shell has been ruthlessly exploiting the region since the 1970s – in cooperation with the corrupted Nigerian elite – committing grave environmental and human rights violations and driving the indigenous communities to poverty. Yet, the EU which imports 20% of its oil (and 80% of its gas) from Nigeria has been reluctant to link its aid agreements and debt-relief schemes with governance and energy reform in Nigeria and has refrained from imposing real punitive measuresFootnote 31 , according to a Solana advisor, out of fear of ‘rocking the boat’ and disrupting energy supplies in Europe (Youngs Citation2009, p. 142). Finally, Congolese human rights campaigners claim that Louis Michel, former Belgian foreign minister and then EU Commissioner for Development had unsavoury dealings in Congo-Kinshasa linking him to Walloon arms and mining interests, aimed to siphon Congo’s raw materials to Europe with the complicity of well-paid local elites, in a mutually lucrative arrangement that compensated the economic deficits of Walloon Belgium (Muller Citation2007, p. 16).

While the EU is seeking to take advantage of trade and energy opportunities in Africa, it has given little attention – in accordance with its self-declared goals and values – to the continent’s democracy, human rights, good governance and security challenges. More particularly, conditionality has not been used effectively to foster progress and reforms in these areas. When it comes to promoting democracy, human rights and good governance – the primary expression of the EU’s ‘civilizing mission’ in the continent – key tools such as conditionality (invoking Articles 96 and 97 of the Cotonou Agreement) have not been applied effectively or consistently. For example, since 1988, no agreement with the ACP countries has been suspended or denounced because of human rights clauses, although aid has been reduced or suspended in a few cases in which they involved coups d’ etats or conspicuous violations of democratic principles (Smith Citation2008, p. 130), as with the coup in the case of Mali (2012). Notably, aid to Zimbabwe continued as authoritarianism increased and was only called into question when violence erupted over farm seizures (Youngs Citation2001, p. 22). Indicative is the fact that it is the poorest and most marginal state in Africa that have been subjected the most to aid suspensions or reductions – Nigeria which did suffer economic and diplomatic sanctions between 1993 and 1999 (as indicated earlier) was a rare exception to the rule, but even here sanctions crucially did not include oil (Khaliq Citation2008, p. 271). Mayer (Citation2008, p. 70) also points to double-standards and the inconsistency with which human rights clauses are included in the interregional agreements with the ACP than in those with South-East Asia. When it comes to the EU’s objective of promoting security in Africa through conflict prevention, resolution and transformation, here again the results have been limited, at best. In conflicts such as in Liberia (1989–2003), Sierra Leone (1991–2002), Somalia (1992-), Rwanda (1994), Ivory Coast (2002-) and Sudan/Darfur (2003-) the EU chose not to intervene through its collective security institutions, preferring to use sanctions and arms embargoes as well as support initiatives of the (relatively weak) African Union. When some member states such as France and the UK did intervene, respectively in Rwanda and Sierra Leone, they were heavily criticized for their timing, methods and results (Smith Citation2008, p. 175). And when the EU did intervene collectively in conflicts such as in Congo (1998-) and Chad (2005–2010), its ESDP operations were evaluated as ‘shallow and safe’ (Bailes Citation2008), ‘incoherent and contradicting’ (Styan Citation2010), ‘conditioned by European interests, primarily French and British’ (Olsen Citation2009) and ‘divorced from broader security challenges of the region’ (Howorth Citation2007).

3.2 Structural dimensions of imperialism in the EU–ACP relationship

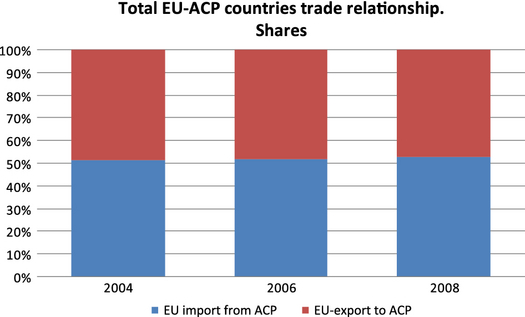

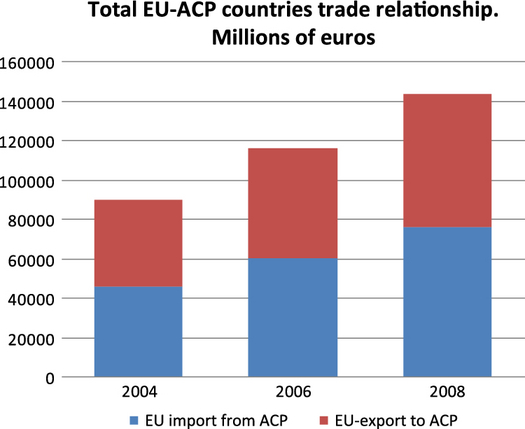

The structural dimensions of the EU’s imperial relationship with the ACP countries are can be made evident by utilizing statistical analysisFootnote 32 , combined with Galtung’s (Citation1971) ‘structural theory of economic imperialism’ and Emmanuel’s (Citation1972) ‘unequal exchange theory’. Here one can observe evidence of hierarchical and centre-periphery structures; asymmetry, inequality and dependence; and exploitation in the EU–ACP relationship. More specifically, Galtung (Citation1971, p. 83) indicated that in an imperialist relationship a centre nation has ‘power over’ a periphery nation which brings about a ‘disharmony of interests’ between them. At the same time, he also indicated that there is also a ‘harmony of interest’ between the elites in the centre nation and the elites in the periphery nation, with the latter acting as a ‘bridgehead’ for the former’s domination in the periphery nationFootnote 33 (Figure ). Both of these elements were evident in the previous ‘agential’ dimension section, where on the one hand, there were elements of coercion and domination exerted from the EU (Centre) towards the ACP countries (Periphery) and a disharmony of interests between the two blocs as a whole, and on the other, there was also evidence of a mutually beneficial and collaborative relationship between EU elites (centre – Centre) and ACP elites (centre – Periphery). Furthermore, according to Galtung (Citation1971, p. 89) the ‘interaction structure’ of empires is vertical between the centre nation and the periphery nation and relatively absent between periphery and periphery nations – he also indicated that periphery interaction with other centre nations is also relatively absent. He theorized this specific form of economic imperialism (1971, p. 101–103) as occurring in three forms: (a) in terms of absolute properties (i.e. development variables such as GNP/cap and percentage employed in non-primary sectors) the centre is high on rank dimensions and the periphery low; (b) in terms of interaction relation (i.e. trade composition index) the centre enriches itself more than the periphery; (c) in terms of interaction structure (i.e. partner and commodity concentration index) the centre is more centrally located in the interaction network than the periphery – the periphery being higher on the concentration indices. In that regard, the ‘development’ variables (i.e. GNP/cap & percentage employed in non-primary sectors) place the polities (i.e. EU and the ACP bloc) in the international ranking system, the ‘inequality’ variables (i.e. Gini income distribution; Gini land distribution) describe the internal structure of the polity, whereas the ‘vertical trade’ (i.e. trade composition index) and ‘feudal trade’ variables (i.e. partner concentration and commodity concentration index) describe the structure of relations between two polities. According to Galtung (Citation1971, p. 101–103), in a relationship of economic imperialism the following correlation pattern occurs (see Figure ) whereby solid lines indicate positive relations and the broken lines indicate negative relations between polities. Data analysisFootnote 34 supports the existence of elements of economic imperialism between the EU and the ACP countries according to the Galtung model. In particular, there is a negative relation between the ‘development’ and one of the ‘feudal trade’ (i.e. partner concentration) variables (i.e. correlation is −0.2283); between the ‘development’ and ‘inequality’ (i.e. Gini income and land) variables (i.e. correlation is −0.4317 and −0.2366, respectively); between the ‘vertical trade’ and one of the ‘inequality’ variables (i.e. correlation is -0.1461); and between ‘vertical trade’ and one of the ‘feudal trade’ variables (i.e. correlation is −0.0315) (See Table ). These negative relations/indices indicate the existence of economic imperialism between the two blocs expressed within a hierarchical, centre-periphery structure.

Figure 2 The correlation pattern according to Galtung’s economic imperialism theory. Source: Galtung Citation1971.

Table 3. Galtung’s economic imperialism theory applied to EU–ACP relations.

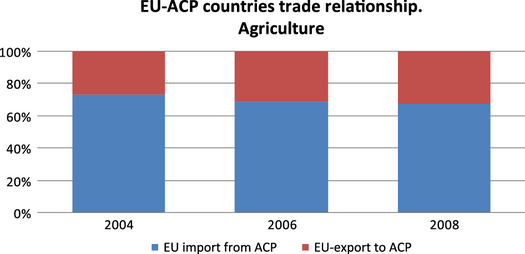

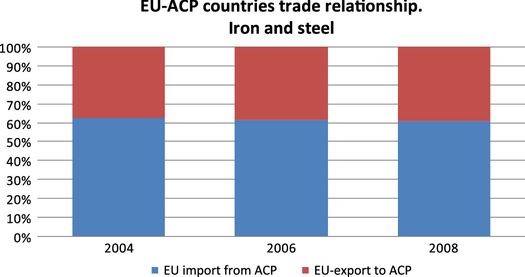

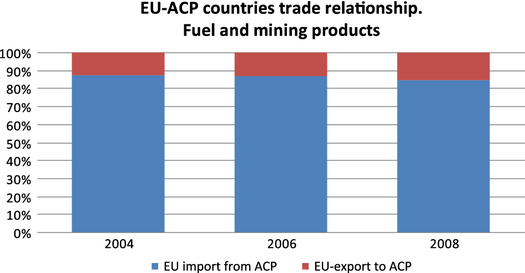

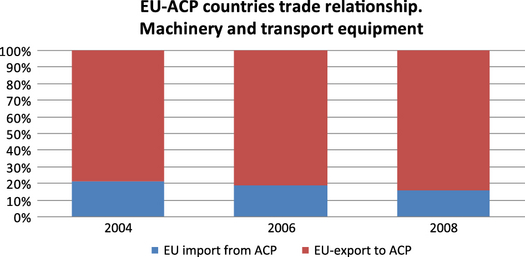

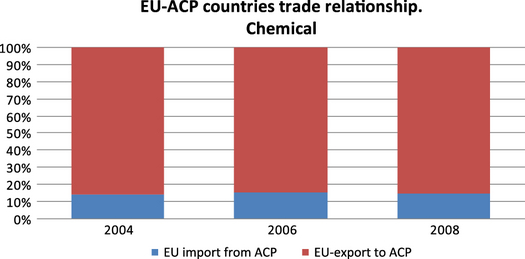

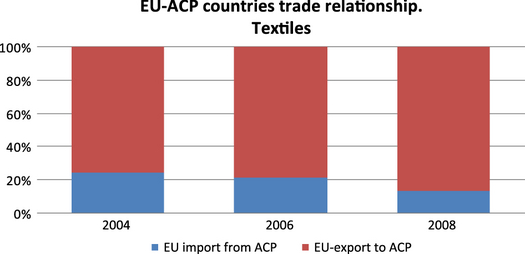

Emmanuel (1972, p. 91–92) also theorized that in a centre-periphery and hierarchical relation, there is an unequal exchange of products, whereby the centre predominantly provides the periphery with manufactured goods (i.e. iron, steel and textiles) including medium and high-tech products (i.e. electronic machinery, chemicals and communications equipment) in exchange for primary goods (i.e. oil, coal, fuels, gas and agricultural products). This relation is usually compounded by exploitation defined as the occurrence ‘when a fair exchange of product X with Y is undermined by trade distortions such as tariffs, quotas, indirect taxes, discriminatory transportation, rates, subsidies, cartels, etc.’ (1972, p. 91). Again, in this analysis one can observe elements of this unequal, hierarchical, centre-periphery relationship in trade between the EU and the ACP countries, which further supports the economic imperialism hypothesis. In particular, one can observe a pattern in the EU–ACP trade relationship, whereby the EU imports from the ACP countries mainly primary products (i.e. fuel & mining; agricultural products) in exchange for manufactured goods (i.e. machinery and transport equipment and chemicals) (see Tables , 5 and Annex) Also, this relationship is clearly compounded by exploitation as evidenced by the wide use of tariffs and subsidies by the EU in its agricultural sector in order to eradicate the only remaining competitive advantage that ACP countries have (cheap agricultural products) over EU producers. In particular, in the much touted ‘Everything but Arms’ (operating since 2001) initiative, the EU strongly pushed for the rapid removal of tariffs and non-tariff barriers in manufactured goods (where it enjoys the advantage) yet, ensured that any removal of such tariffs and barriers from agricultural products such as sugar, rice and bananas (where ACP countries enjoy the advantage) was to proceed slowly and gradually and in some case not at all (Flint Citation2008, p. 71). Also, the EU consistently uses enormous subsidies to protect its agricultural producers from any ACP competition with its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) regularly cited as being in flagrant breach of all neoliberal principles, dispensing approximately €58 billion ($77 billion) per year in subsidies.Footnote 35 These subsidies have a negative impact on free trade, with the CAP regularly resulting in large-scale overproduction and the excess then frequently ‘dumped’ on the ACP countries, thereby undercutting local producers who cannot compete (Flint Citation2008, p. 87).

Tables 4 and 5. Emmanuel’s unequal exchange theory applied to EU-ACP relations.

It is important to indicate that these hierarchical, centre-periphery structures between the EU and the ACP countries are much more profound and vivid, in terms of economic dependence and in accordance with the Galtung theorem, than those between other prospective empires (USA, China and Russia) with the ACP countries. For example, in 2009, total EU merchandize trade (i.e. goods, supplies, raw materials, products) with Africa accounted for 39.6% of total African merchandize trade, compared to 13.5% with China, 12.7% with the USA and 1% with Russia.Footnote 36 Also, periphery–periphery economic relations were also relatively small, compared to centre–periphery relations, partly a result of the relatively (compared to the EU) weak and divided African regional organizations such as the African Union, the Maghreb and Mashreq Unions and the Arab LeagueFootnote 37 – in particular, total intra-African merchandize trade amounted to only 9.2%.Footnote 38 Moreover, the institutional nature of the EU–ACP agreements (i.e. Cotonou) are arguably much wider and deeper in scope and nature than the respective agreements of Africa with the US (i.e. US African Growth and Opportunity Act), China (i.e. Forum of China and Africa Cooperation) and Russia (i.e. Russia-Africa Horizons Cooperation) – the same can also be said about the EU’s imperial ‘civilizing mission’ in Africa, expressed primarily through its democracy, human rights and good governance rhetoric, being more pronounced in the continent than those of other ‘empires’. These are reinforced by the closer, geographical, historical (colonial), political and sociocultural ties that exist between Europe and Africa that are conducive to maintaining such centre-periphery structures, and that can supersede the respective influence of a ‘global empire’ such as the US. In the present era of increased globalization, interdependence and interconnectedness, it should not be expected that peripheries of empires (such as the ACP group for the EU) have no relations or institutional links with other prospective empires, nor can it be expected that periphery-periphery relations are completely absent. But what is important in indicating that a specific region is the periphery of another, is the much greater degree of dependency that exists between that periphery region with its centre, than with other centres, as is the case of greater ACP dependency on the EU, than on the US, China or Russia.

4 Conclusion

This paper has indicated the agential and structural dimensions of the EU’s imperial relationship with the ACP countries. As an agency, we can observe that the EU projected, more particularly in its negotiations of the various trade, agricultural, energy and security agreements, elements of power that include coercion, agenda-setting, as well as attraction with hidden elements of manipulation – attraction and manipulation can also be considered to have structural and non-behavioural dimensions. On the structural dimension, we can observe that the EU operated within an economic relationship with the ACP countries that is characterized by hierarchical, centre-periphery structures, asymmetry, dependence and exploitation. We can also observe that the EU does little to transform this structural relationship – rather the Union has been complicit in its reproduction, sadly, in coordination with particular African agents, i.e. African elites. The existence of both of these agential and structural dimensions of imperialism strongly suggests that the EU relates to and behaves towards the ACP countries, as an imperial power Europe.

This has particular scholarly implications, as to how we understand imperialism as a specific form of power that is projected in various forms, including hard and soft (i.e. coercion, mobilization of bias/agenda-setting and attraction), ways (behavioural and non-behavioural) and dimensions (agential and structural). What it also reveals is that imperialism has mostly negative consequences on the recipients or objects of this form of power. But it also reveals that the role of agency, both from the perspective of the imperial power as well as from the perspective of the recipients of this form of power is crucial in changing, sustaining and reproducing the imperial structural relationship. When it comes to our understanding of the EU as an international actor, there are also scholarly implications – it means that this ‘imperial’ dimension of the Union needs to be recognized and reconciled along with the other more conventional identity traits of the Union as that of ‘civilian’, ‘normative’, ‘soft’ or ‘ethical’ power Europe. Perhaps this is the true nature of the EU – a somewhat contradicting, if not conflicted, entity which may project power in different ways and forms at different times and places. Finally and more importantly, the policy implications from this is that the EU will need – if it is serious in being a ‘force for good’ in the world – to address this evident ‘rhetoric-reality’, ‘discourse-praxis’ gap in its policies towards much of the developing world, not only for the sake of the latter but also for the sake of its own credibility, legitimacy and identity in the eyes of others and towards its own citizens.

Notes on contributor

Angelos Sepos is assistant professor in European Politics at Akhawayn University, Ifrane, Morocco. He is the author, among other among other publications, of The Europeanization of Cyprus: Polity, Policies and Politics (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) and co-editor (with Kenneth Dyson) of Which Europe? The Politics of Differentiated Integration (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this journal for their positive and constructive comments on the paper. Special thanks to Gianpiero Torrisi for his work on the quantitative analysis of the data.

Notes

1. Solana Citation2005. Javier Solana was the EU’s High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy at the time. See also, the EU’s European Security Strategy ‘A Secure Europe in a Better World’, Brussels, 12 December 2003, p.13.

2. Council of the EU, EU Annual Report on Human Rights, 1998–1999, Luxembourg: OOPEC, p.2.

3. Article I-3(4) of the Constitutional Treaty.

4. ‘Barosso says EU is an Empire’, EU Observer, 11 July 2007.

5. The term ACP is used for analytical purposes and to assist the qualitative and quantitative analysis of data (i.e.the EU signs agreements and trades with the ACP countries as a bloc) - the focus of the article, however, will be on Africa rather than the Caribbean and Pacific Region.

6. On Disraeli see Warner, H.L., 1932. Disraeli and the Eastern Question, 1876–1878: The Triumph of Imperialism, MA: Harvard University Press.

7. On Rhodes see Langer, W., 1935. Diplomacy of Imperialism: 1890–1902, New York: A.A. Knopf.

8. On Kipling see Carrington, C., 1955. Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work, London: Macmillan.

9. Arendt (Citation1970) (‘power in concert’), Habermas (Citation1986), (i.e. ‘communicative power’), Foucault (Citation1980) (i.e. ‘lack of a source of power’), Gaventa (Citation2007) (i.e. ‘cube of power’) and Barnett and Duvall (Citation2005) (‘four forms of power’) have also made important contributions.

10. Isaac, Citation1987 also took a similar structural approach to power.

11. ‘Coercion’ exists where ‘A secures B’s compliance by the threat of deprivation where there is a conflict over values or course of action between A and B’.

12. ‘Force’ exists when ‘A achieves his objectives in the face of B’s noncompliance by stripping him of the choice between compliance and non-compliance’.

13. ‘False consciousness’ or ‘the power to mislead’ is cultivated, among other ways, through censorship and disinformation and the promotion and sustenance of all kinds of failures of rationality and illusory thinking, leading to misrecognition of sources of desires and beliefs (Lukes Citation2005, p. 149).

14. ‘Influence’ exists where ‘A, without resorting to either a tacit or an overt threat of sever deprivation, causes B to changes his course of action’ (Bachrach and Baratz Citation1970, p. 30) – it belongs in the 3rd dimension of power ‘ as long as sanctions are not involved’ (Lukes Citation2005, p. 35).

15. In ‘manipulation’, ‘A seeks to disguise the nature and source of his demand upon B, and if A is successful, B is totally unaware that something is being demanded on him’ (Bachrach and Baratz Citation1963, p. 636).

16. ‘Representational force’ works through credible threats of unbearable harm to its victims and is aimed at the victim’s subjectivity rather than physicality and is communicated through norms rather than material capabilities (Mattern Citation2007, p. 110).

17. European Commission Citation2006b.

18. Chatman House Citation2008.

19. The Guardian, 8 November 2007.

20. Joint Assembly of the EU and the ACP countries 2008, Secretariat of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States 2008.

21. The Guardian, 8 November 2007.

22. Interview with Christiane Leong HoYng, Expert, Multilateral Trade Issues, ACP Secretariat, Brussels, 15 Oct. 2009.

23. The Guardian, 2 November 2007.

24. ACP Council of Ministers, 13 December 2007, ACP/25/013/07.

25. Assembly of the African Union, Tenth Ordinary Session, 31 January – 2 February 2008.

26. ‘Trade Talks Reach Impasse at Europe-Africa Summit’, Africa Renewal, vol. 21 (4), January 2008.

27. All Africa (2008) ‘If the EPAs Are So Good, Why Force Us to Sign?’ by P. Semu-Banda, 23 April.

28. The EU currently imports 15% of its oil and gas from Africa with this figure expected to substantially increase in the coming years.

29. The Independent, 25 January 2000.

30. InterPress Service News, 19 February 2009.

31. For example, when prominent Ogoni human rights activist Ken Saro Wiwa was executed in 1995, the EU refrained from imposing an oil embargo (under British and Dutch insistence) resorting instead to the softer measure of suspending military cooperation and the visa regime.

32. Special thanks to Gianpiero Torrisi (Centre for Urban & Regional Development Studies, Newcastle University) who has conducted the economic data gathering and analysis for the application of Galtung’s and Emmanuel’s models in this case study.

33. In indicating that there is a centre (elites) and periphery (non-elites) in both the Centre and Periphery nations, Galtung (Citation1971, p. 83) observed that there is a disharmony of interests between elites and non-elites in both the Centre and Periphery nations, with that disharmony being greater in the Periphery nation. He also indicated that there is a disharmony of interests between the periphery in the Centre nation and the periphery in the Periphery nation. These observations are noted but will not be empirically examined as they fall outside of the scope and objectives of this paper.

34. Data for % non-primary, Trade composition, Partner concentration and Commodity concentration are drawn from Eurostat; Data for GDP/cap are International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook (2009); Data for Gini Income are drawn from the World Income Inequality Database compiled by United Nations University. Note that except for the Gini land index which refers to the most recent available datum all other variables refer to the respective 1999–2009 average.

35. European Commission Citation2012.

36. OECD Factbook 2001, Africa’s trade partners.

37. For more on the weaknesses of these organizations see Mortimer Citation1999, Murithi Citation2005, Barnett and Solingen Citation2007.

38. Ibid.

References

- Aggestam , L. 2008 . Introduction: ethical power europe? . International Affairs , 84 ( 1 ) : 1 – 11 .

- Amin , S. 1972 . Underdevelopment and dependence in Black Africa: origins and contemporary forms . Journal of Modern African History , 10 ( 4 ) : 503 – 524 .

- Anderson , J. 2007 . “ Singular Europe: an empire once again? ” . In Geopolitics of European Union enlargement: the fortress empire , Edited by: Amstrong , W. and Anderson , J. 9 – 29 . London : Routledge .

- Angell , N. 1939 . The great illusion , Harmondsworth : Penguin Books .

- Arendt , H. 1970 . On violence , New York : Harcourt Brace .

- Arendt , H. 1951 . The origins of totalitarianism , New York : Harcourt Brace .

- Arrighi , G. and Silver , B. 1999 . Chaos and governance in the modern world system , Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press .

- Bachrach , P. and Baratz , M. 1970 . Power and poverty: theory and practice , New York : Oxford University Press .

- Bachrach , P. and Baratz , M. 1963 . Decision and non-decisions: an analytical framework . American Political Science Review , 57 ( 2 ) : 632 – 642 .

- Bachrach , P. and Baratz , M. 1962 . Two faces of power . American Political Science Review , 56 ( 4 ) : 947 – 952 .

- Bailes , A. 2008 . The EU and a ‘better world’: what role for the European security and defence policy? . International Affairs , 84 ( 1 ) : 115 – 130 .

- Baran , P. 1957 . The political economy of growth , New York : Monthly Review Press .

- Barnett , M. and Duvall , R. 2005 . Power in international politics . International Organization , 59 : 39 – 75 .

- Barnett , M. and Solingen , E. 2007 . “ Designed to fail or failure of design? the origins and legacy of the Arab league ” . In Crafting cooperation: regional institutions in comparative perspective , Edited by: Acharya , A. and Johnston , A. 180 – 220 . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

- Beck , U. and Grande , E. 2007 . Cosmopolitan Europe , Cambridge : Polity .

- Behr , H. 2007 . The European Union in the legacies of imperial rule? EU accession politics viewed from a historical comparative perspective . European Journal of International Relations , 13 ( 2 ) : 239 – 262 .

- Bradshaw , A. 1976 . A critique of Steven Lukes’ Power: a radical view . Sociology , 10 : 121 – 127 .

- Bretherton , C. and Vogler , J. 1999 . The European Union as a global actor , London : Routledge .

- Bukharin , N. 1972 . Imperialism and world economy , London : Merlin .

- Caporaso , J. 1974 . “ Methodological issues in the measurement of inequality, dependence, and exploitation ” . In Testing theories of economic imperialism , Edited by: Rosen , S. and Kurth , J. 91 – 123 . Lexington : Lexington Books .

- Cerny , P. 2006 . “ Dilemmas of operationalizing hegemony ” . In Hegemony and power: consensus and coercion in contemporary politics , Edited by: Haugaard , M. and Lentner , H. 67 – 89 . Oxford : Lexington Books .

- Chatman House . 2008 . EU trade policy: approaching a crossroads , London : Chatman House .

- Chandler , D. 2006 . Empire in Denial: the politics of state-building , London : Pluto Press .

- Cohen , B. 1974 . The question of imperialism: the political economy of dominance and dependence , London : Macmillan .

- Commission for Africa, 2010. Still our Common Interest. September.

- Cooper , R. 2007 . The breaking of nations: order and chaos in the twentieth-first century , 2nd ed. , London : Atlantic Books .

- Cotonou Agreement, 2000. ACP-EU Partnership Agreement. Cotonou, 23 June 2000. Revised 25 June 2005.

- Cox , R. 1987 . Production, power and world order , New York , NY : Columbia University Press .

- Crozier , B. 1964 . Neo-colonialism: a background book , London : Bodley Head .

- Dahl , R. 1957 . The concept of power . Behavioural Science , 2 ( 3 ) : 201 – 215 .

- Diez , T. 2005 . Constructing the self and changing others: reconsidering normative power Europe . Millennium: Journal of International Studies , 33 ( 3 ) : 613 – 636 .

- Diez , T. and Whitman , R. 2002 . Analyzing European integration: reflecting on the English school – scenarios for an encounter . Journal of Common Market Studies , 40 ( 1 ) : 43 – 67 .

- Doyle , M. 1986 . Empires , Ithaca , NY : Cornell University Press .

- Duchene , F. 1972 . “ Europe’s role in world peace ” . In Europe tomorrow: sixteen Europeans look ahead , Edited by: Mayne , R. 32 – 47 . London : Fontana .

- Elgstrom , O. and Smith , M. 2006 . The European union’s role in international politics: concepts and analysis , London : Routledge .

- Emmanuel , A. 1972 . Unequal exchange: a study of the imperialism of trade , London : New Left Books .

- European Commission . 2012 . The budget for the European Union for 2012 , Brussels : European Commission .

- European Commission . 2006 . DG trade. global Europe: Competing in the world , Brussels : European Commission .

- European Commission . 2005 . Sustainability impact assessment of proposed WTO Negotiations: final report for the forest sector study , Commissioned by the European Commission in association with the University of Manchester .

- European Commission . 2005 . EU strategy for Africa: towards a Euro-African pact to accelerate Africa’s development , Brussels : European Commission .

- European Commission . 2003 . A secure Europe in a better world. European security strategy , Brussels : European Commission .

- Flint , A. 2008 . Trade, poverty and the environment: The EU, Cotonou and the African-Caribbean-Pacific bloc , Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Foucault, M., 1980. Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings. 1972-1979. C.Gordon, ed. transl. Brighton: Harvester, 109–133.

- Frank , A.G. 1967 . Capitalism and underdevelopment in Latin America: historical studies in Chile and Brazil , London : Monthly Review Press .

- Galtung , J. 1971 . A structural theory of imperialism . Journal of Peace Research , 8 ( 2 ) : 82 – 83 .

- Gaventa , J. 2007 . “ Levels, spaces and forms of power: analyzing opportunities for change ” . In Power in world politics , Edited by: Berenskoetter , F. and Williams , M.J. 204 – 225 . London : Routledge .

- Giddens , A. 1979 . Central problems of social theory , Berkeley : University of California Press .

- Goodison , P. 2007 . The future of Africa’s trade with Europe: ‘new’ EU trade policy . Review of African Political Economy , 111 : 139 – 151 .

- Gramsci , A. 1971 . Selections from the prison notebooks , New York : International .

- Gravier , M. 2011 . Empire vs. federation: which Path for Europe? . Journal of Political Power , 4 ( 3 ) : 413 – 431 .

- Gravier , M. and Parker , N. 2011 . Imperial power and the organization of space in Europe and North Africa . Journal of Political Power , 4 ( 3 ) : 331 – 336 .

- Habermas , J. 1986 . The theory of communicative action , Cambridge : Polity Press .

- Harvey , D. 2003 . The new imperialism , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Harris, J. and Robinson, W., 2000. Fissures in the globalist ruling bloc? Seattle and the politics of globalization from above. Third Wave Study Group Paper, 1–23.

- Haukkala , H. 2008 . The European Union as a regional normative hegemon: the case of European neighbourhood policy . Europe-Asia Studies , 60 ( 9 ) : 1601 – 1622 .

- Hayward , C. 1998 . De-facing power . Polity , 31 ( 1 ) : 1 – 22 .

- Hettne , B. and Soederbaum , F. 2005 . Civilian power or soft imperialism? The EU as a global actor and the role of interregionalism . European Foreign Affairs Review , 10 ( 4 ) : 535 – 552 .

- Hill , C. and Smith , M. 2005 . International relations of the EU , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Hobson , J. 1902 . Imperialism: a study , London : Allen & Unwin .

- Hodder-Williams , R. 2001 . “ Colonialism: political aspects ” . In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioural sciences , Edited by: Smelser , N. and Baltes , P. 2237 – 2240 . Oxford : Elsevier .

- Howorth , J. 2007 . Security and defence policy in the European Union , Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Hurrell , A. 2005 . Pax Americana or the empire of insecurity . International Relations of the Asia-Pacific , 5 : 153 – 176 .

- Hurrell , A. 2005 . “ Power, institutions and the production of inequality ” . In Power in global governance , Edited by: Barnett , M. and Duvall , R. 33 – 59 . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

- Hurt , S. 2003 . Cooperation and coercion? The cotonou agreement between the European Union and ACP states and the end of the Lomé convention . Third World Quarterly , 24 ( 1 ) : 161 – 176 .

- Isaac , J. 1987 . Beyond the three faces of power: a realist critique . Polity , 20 ( 1 ) : 4 – 31 .

- Joint Assembly of the EU and the ACP Countries, 2008. ACP-EU Call to Put Back EPA Deadline. 23 November.

- Joseph , J. 2002 . Hegemony: a realist analysis , New York : Routledge .

- Khaliq , U. 2008 . Ethical dimensions of the foreign policy of the EU: a legal appraisal , Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

- Laidi , Z. , ed. 2008 . EU foreign policy in a globalized world: normative power and social preferences , London : Routledge .

- Lake , D. 2001 . “ Imperialism: political aspects ” . In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioural sciences , Edited by: Smelser , N.P. and Baltes , P. 7232 – 7234 . Oxford : Elsevier .

- Lenin, V., 1916. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Introduction by L. Norman and J. Malone. Living Marxism Originals. 1996. London: Pluto Press.

- Lorenzi , M. 2006 . Power: a radical view by Steven Lukes . Crossroads , 6 ( 2 ) : 87 – 95 .

- Lukes , S. 2010 . In defence of false consciousness , Chicago , CA : University of Chicago Legal Forum . 1–22

- Lukes , S. 2005 . Power: a radical view , 2nd ed , Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Lukes , S. 1974 . Power: a radical view , 1st ed. , Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Luxemburg , R. 1951 . The accumulation of capital , London : Routledge .

- Marks , G. 2012 . Europe and its empires: from Rome to the European Union . Journal of Common Market Studies , 50 ( 1 ) : 1 – 20 .

- Mathew , M.W. 1968 . The imperialism of free trade: Peru, 1820–70 . The Economic History Review , 21 ( 3 ) : 562 – 579 .

- Mattern , J.B. 2007 . “ Why soft power isn’t so soft: representation force and attraction in world politics ” . In Power in world politics , Edited by: Berenskoetter , F. and Williams , M.J. 98 – 120 . London : Routledge .

- Manners , I. 2002 . Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms? . Journal of Common Market Studies , 40 ( 2 ) : 235 – 258 .

- Mayer , H. 2008 . Is it still called ‘Chinese Whispers’? The EU’s rhetoric and action as a responsible global institution . International Affairs , 84 ( 1 ) : 61 – 79 .

- McCormick , J. 2006 . The European superpower , London : Palgrave Macmillan .

- Medard, J.F., 1999. Oil and War: Elf and ‘FrancaAfrique’ in the Gulf of Guinea. Working Paper. Bordeaux: Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Bordeaux, 1–13.

- Morgenthau , H. 1948 . Politics among nations: the struggle for power and peace , New York , NY : Alfred A. Knop .

- Mortimer , R. 1999 . “ The Arab Maghreb union: myth and reality ” . In North Africa in transition , Edited by: Zoubir , Y. 177 – 195 . Gainesville , FL : U Florida Press .