ABSTRACT

Illegal economies have received substantial attention in conflict studies over the past decades. Often, this attention is linked to economicist paradigms, rendering invisible the political processes linking conflict and illegal economies. By discussing the Colombian case, we argue that criminalisation is linked to patterns of capital accumulation and State-building. First, it reflects a long-term conflict of Proudhonian overtones between small-scale producers and big capital; secondly, it reflects a Tillyian process but without a Tillyian effect. Thus, the interaction between capital accumulation, political power and warfare takes place, without the expected result of a centralised and efficient, democratic State.

1. Introduction

Colombia, for nearly half a century, has been both the scenario of the longest armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere and the focus of international efforts to eradicate thriving illegal economies, chiefly (but not exclusively) production of cocaine. Colombia has been for the last 40 years, undisputedly, the main producer of cocaine (Tokatlian Citation2000, Rentería Citation2001, Bagley Citation2005, Thoumi Citation2015, UNODC Citation2021). More recently, other illegal economies are getting as much attention, in particular illegal mining, chiefly (but not exclusively) of gold. Illegal economic activities have been given a privileged explanatory power in relation to the various ills afflicting Colombian society as if they possessed, per se, the ability to account for corruption or the longevity of the persistent internal armed conflict (Guáqueta Citation2003, McDougall Citation2009, Idrobo et al. Citation2014, Maldonado and Rozo Citation2014, Escobedo and Guío Citation2015, Davis et al. Citation2016, Rettberg and Ortiz Citation2016, Montero Citation2017, OECD Citation2017, Idler Citation2019). Drugs and now illegal mining are considered to be the ‘fuel’ of the conflict: take them out of the equation, and Colombia would be nothing short of an oasis of peace in a chaotic continent (El Tiempo Citation2000, El Tiempo Citation2020).

The basic premise behind the ‘fuel-of-the-conflict’ narrative, that conflict is primarily about rent-seeking, has been discussed elsewhere (Cramer Citation2002, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2003, Gutiérrez and Thomson Citation2021). In this paper, therefore, we will question other important premises behind this narrative that have not been subject to the same critical analysis.

First, we will question the obsessive emphasis with ‘non-State armed actors’ -an extremely vague and equivocal term, which obfuscates and confuses rather than clarifies the terms of the debate.Footnote1 This emphasis is particularly puzzling in a country where national elites have extensive and proven involvement in activities they themselves have defined as ‘criminal’: multiple scandals have exposed the links of dominant parties, senior government figures and their relatives, businesspeople and media personalities into a range of illegal activities, including, but not limited, to drug trafficking and production (Bowden Citation2010, López and Ávila Citation2010, Ronderos Citation2014, Davis Citation2015, Sáenz Citation2021). The wealth of evidence of implication of the elites in the illegal economy, accumulated mostly in journalistic work, has rarely been the subject of academic research -and when it is, is mostly through the phenomenon of right-wing paramilitarism (Medina Citation1990, Hristov Citation2009, Zelik Citation2015, Grajales Citation2017, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2019). Although the influence of illegal economies permeates the whole of Colombian society, the debate on illegal economic activities has centred, on the one hand, around non-State, particularly rebel, armed actors; on the other hand, it has centred on the bottom of the value-chain (i.e., cultivators and small-scale miners), the so-called ‘peripheries’ or ‘borderlands’, deflecting attention from the top of the value-chain, where most of the profit is actually created -and where often legal actors profit handsomely. We argue that discourses of centre (legal/State) and periphery (illegal/non-State) prevent us from understanding the ways in which illegal economies articulate with the broader political economy (cf. Domínguez Citation2005) and with State-building processes.

Secondly, we will question dominant approaches focused on the absence/presence and weakness/strength of the State in peripheral territories. Generally, these neo-functionalist approaches assume the State as a neutral expression, instead of an institution shaped by power relations and subject to contestation. On the contrary, we will emphasise how large swathes of territory supposedly outside the control of the State are, indeed, the product (and victims) of a particular version of State-building, which constantly reasserts itself through the creation of ‘hinterlands’ and ‘peripheries’ (Serje Citation2005). At the same time, the ‘centre’ is idealised, although

(…) nowhere in Colombia can one find the idealized state that elites claim is absent in the frontier. Indeed, the neutrality and disinterestedness that ruling groups insist must be established in the peripheries of the nation is lacking even in the supposedly most state-saturated regions of the country (the national capital). Even in the center, state and nonstate actors alike employ violence on an extensive scale and in the most arbitrary of manners to achieve their particularistic ends (Ramírez Citation2015, p. 36).

Thus, the centre-periphery divide and the criminalisation of the latter become State-building mechanisms, which are vigorously contested by the population in these regions. Our approach requires a shift from the emphasis on regional studies, so prevalent in Colombia, towards the corridors of the apparatuses of State where the political process of criminalisation is designed and decided.

Thirdly, we will question the reification of illegal economic activities, which assumes that their ‘illegal’ character is an intrinsic quality, instead of the product of a political process. In our understanding, definitions of ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ are not a merely technical affair, but are subject to asymmetrical power relations. Criminalisation is a power exercise by which an economic activity is regulated through specific forms of violence rather than through the mythical ‘invisible hand’ of the market (Ciro Citation2020). In this sense, we will move beyond the narrow binary opposition of legal/illegal: both categories are articulated in the broader political economy as means to regulate capital and political power accumulation.

In order to proceed with our arguments, we will focus on the political process behind the criminalisation of (mostly) small-scale producer economic activities. That political and criminal involvement are not a zero-sum type of inverse proportional relationship, and that indeed, involvement in criminal activities can in itself be political has been argued convincingly elsewhere (e.g., Gutiérrez and Thomson Citation2021); here we will focus on the political process behind criminalisation as such. This process reflects the tensions inherent to the accumulation patterns of both capital and political power in the Colombian context, which are indissociable from systematic large-scale dispossession of land from the myriad of independent producers who populate the Colombian hinterlands described as ‘red zones’ (i.e. areas of military operations). We will examine the criminalisation of the economies of coca and gold after 1996, a year signalling a significant escalation of direct and indirect State-led violence against criminalised producers. This violence has been justified in the name of the ‘war of drugs’, counter-insurgency and the ‘war on terror’, with the US providing arguments, support and funding (Palacios, Citation2012; Tate Citation2015, Vega Citation2015, Lindsay-Poland Citation2018).

We will argue, as proposition A, that both criminalised activities -cocaine and gold- share in common the fact that, although both are complex and stratified industries controlled at the top of the value-chain by powerful and well-connected individuals, their bottom is composed by a mass of small-scale producers who bear the brunt of the State repressive measures. We argue that this criminalisation is part of a historical hostility of the Colombian elites against small-scale independent producers, more oriented towards the reproduction of their family units rather than bigger capitalist venture (LeGrand Citation1986, Vega Citation2002). In this sense, the Colombian conflict responds more to the Proudhonian model of conflict -one revolving over the autonomy of small-scale producers- than the proletariat vs. bourgeoisie Marxist model of conflict.

Proposition B, builds up on proposition A. We argue that the criminalisation of economic activities has impacted significantly the State-building patterns in Colombia, war being an integral part of it. This war-system (Richani Citation2013) naturalises the large-scale dispossession of small-scale producers, which in any case does not go without resistance (Fajardo Citation2015). Here, the links observed by many sociologists between State-building and warfare (Tilly Citation1985, p. Citation1992, Giddens Citation1985, Mann Citation1988, Citation2012, Tarrow Citation2015) offer important clues to understand the process of State-building through massive violence against the population; but here the process (the intersection between war, political power and capital) does not produce the expected outcomes of the theory (the emergence of a relatively centralised and democratic nation-State). In this sense, we talk of a Tillyian process without a Tillyian effect.

We proceed by explaining the methods, before discussing in more detail some of the assumptions prevalent in the literature on illegal activities and conflict. We then discuss two criminalised economic activities in Colombia to provide background. We discuss criminalisation in the context of power relations, bringing to the fore the political process behind it. We then locate the place of these illegal economies in relation to specific patterns of capital accumulation -which we link to a Proudhonian model of class conflict- and forms of State-building, where we draw critically from the Tillyian model. We will finalise with some concluding remarks and outlining some elements for a research agenda on the topic.

2. Methods

This paper is of an exploratory nature, which means that it is more concerned with generating propositions in order to advance future research agendas, develop theory and concepts (Stebbins Citation2001, Davies Citation2006). This is mostly a discussion reflecting our discontent with much of the prevalent literature, whose concepts and categories of analysis seem ill-equipped (theoretically, empirically and also conceptually) to understand the complexities of the relationship between the legal and illegal spheres in conflict situations. This is the first contribution of a much broader research agenda in which we will further explore some of the discussions here advanced.

We approach the problem by analysing critically the regulatory legal frameworks of the mining and drug policies in the period 1996–2016 (See ). This paper also builds on extensive ethnographic experience in regions of illegal economic activities, including some regions which are predominantly cocaine producing (Putumayo, Cauca, Caquetá, Córdoba, Nariño y Guaviare) and some areas which have gold mining as a primary economic activity (Southern Bolívar) or as a complementary economy to peasant smallholders (Cauca Valley and Ituango).

Table 1. Main changes in the regulations on illegal drugs in Colombia (1998–2017)

Table 2. Main changes in the mining regulations in Colombia (2001–2017)

3. Illegal economies and conflict: some preliminary observations

The 1990s witnessed two simultaneous phenomena, which reinforced one another -the end of the Cold War and the global hegemony of the US-sponsored neoliberal system (Harvey Citation2005, Hobsbawm Citation2007). The end of history announced by Fukuyama (Citation1992), became also the end of human evolution, our species having arrived to the ultimate stage: the homo economicus.

During this period, the persistence of conflict after the (supposed) end of ideologies was explained by two dominant narratives. On the one hand, the New Wars paradigm claimed that conflicts were now diffuse and about identity, emphasising the ‘criminalisation’ of conflict (Kaldor, Citation2001). On the other, Paul Collier and his associates developed the narrow ‘economic theory of conflict’ according to which rent-seeking activities explain the root causes of any rebellion (Collier and Hoffler, Citation1998, Collier Citation2000). Simple as that. Both narratives have evolved and developed into other paradigms, such as the ‘crime-terror nexus’ or ‘continuum’ (e.g. Makarenko Citation2004).

These reductionist narratives have been subject to a relentless critique (e.g. Kalyvas Citation2001, Cramer Citation2002, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2003). Notwithstanding the crisis of this approach, its allure remains strong in Colombia. As the biggest producer of cocaine in the world, Colombia is a showcase to a pervasive narrative in which drugs are the ‘fuel’ and master explanation of conflict. President Iván Duque summarises this position eloquently, when he says ‘the biggest enemy of peace-building in Colombia is drug trafficking; the more coca, the less peace, this is the painful equation we have lived with for the past decades’ (Leal, Citation2021).

As Colombia slips towards a new cycle of conflict (Gutiérrez Citation2020, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2020) most explanations still revolve around the control of illegal rents by non-Strate actors (e.g., Massé and LeBillon Citation2018, Idler Citation2019; Garzón et al., Citation2021, Nova Citation2020, FIP Citation2021). This so-called ‘rebels-turned-narcos premise’ has been critiqued as a reductionist narrative, insufficiently grounded in evidence, according to which former ideologically committed rebels, by entering into the illegal drugs production chain become irredeemably corrupted (Gutiérrez and Thomson Citation2021). The more involved, the less political they become.

By criticising economicist reductionism, we do not hold the economy to be irrelevant to understanding conflict. On the contrary, we believe there is a need to adopt broader political economy perspectives instead of a narrow caricature which reduces the behaviour of people in conflict to that of maximising carnivores. This caricature reifies illegal economies by giving them intrinsic qualities which render invisible the social, political and historical context only in which they can be made sense of.

The economicist approach found its policy match in the counter-insurgent strategy to attack the so-called ‘funding sources of terrorism’ contained in the US Patriot Act,Footnote2 which had already been advanced through ‘Plan Colombia’ (1999), later mutating into the Colombian ‘Patriot Plan’ (Rojas, Citation2015, Tate Citation2015, Vega Citation2015, Lindsay-Poland Citation2018). Today, this approach has been adopted by the policy of ‘Peace with Legality’ of Duque’s government (Presidencia de la República Citation2018). Collapsing the wars against illegal economies and against insurgency turned the criminalisation of illegal activities into a moral crusade, far more serious than a merely legal question, conflating narratives of fatherland, values, sovereignty and patriotism (Ministerio de Defensa Citation2003, Centeno et al. Citation2013).

Ahead of Plan Colombia, there had been a significant escalation of military counter-narcotics operations since 1996, led paradoxically by president Ernesto Samper, whose campaign was handsomely funded by drug dealers (Rettberg Citation2011), after a 200,000 people-strong march of cocalero peasants (Ramírez Citation2011). Since then, entire regions and their populations have been criminalised as ‘red zones’, and subject to the treatment as enemies of the State -as ‘terrorists’ (Ramírez Citation1996, Citation2011, Gutiérrez Citation2021, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2021). Thus, people engaged in the drug economy became ‘narco-terrorists’ (a term which is often used in a very different way as how it originated in the 1980s).Footnote3 Later, those engaged in illegal mining, became ‘criminal miners’ and funders of ‘terrorism’, after president Santos formally declared ‘war’ against ‘criminal mining’ in 2015, labelling it -following US military jargon- a ‘high-value target’ (El Espectador Citation2015, Massé and LeBillon Citation2018). In 2019, president Duque was announcing to mining corporations (after they had required energic military measures) new military units to deal with ‘illegal’ miners (Arias Citation2019, Betancur Citation2019).

4. Some background on the cocaine and gold economies

Both coca and gold have long histories in Colombia spanning many centuries. Both economies are also extremely diverse, including people who work full-time on them, others who supplement farming income, people that have worked traditionally in these economies and people from far away who have settled into these regions with the illusion of leaving poverty behind. Although this is not the place to do a history of coca or gold, which have been done elsewhere (e.g., West Citation1972, Gootenberg Citation2008, Dávalos et al. Citation2016, Ciro Citation2020), we discuss key aspects of both economies in order to proceed with our argument on the criminalisation of both activities.

4.1. Cocaine

Coca has been for millennia a sacred plant for Andean American natives, before the German pharmaceutical industry created cocaine in the 19th century (Marichal et al. Citation2006). In the 1920s cocaine had been made illegal, first in the US, then in the rest of the world (Hawdon Citation1996, Spillane Citation1999, Gootenberg Citation2008, López Citation2016). In Colombia, the production and trade of illegal drugs started with marihuana in the mid-20th century, mostly to the US; these same networks were used when cocaine became the predominant drug in the 1970s (Sáenz Citation2021).

A number of factors coalesced to turn Colombia into the world’s number one cocaine producer, producing an estimated 64% of the world cocaine in 2019 (UNODC Citation2021). First, the elites’ unwillingness to reform the deeply unequal agrarian structures, coupled with high levels of political violence in the countryside throughout most of the 20th century, created a mass of uprooted peasants willing to expand the agrarian frontier through successive waves of colonisation (LeGrand Citation1986, Fajardo Citation2015). Coca provided this peasantry in dire need of some form of stability a promising and stable market. In fact, the combination of insurgency and coca created, in some regions, a wall of contention against land concentration (Molano Citation1994; Vásquez, Citation2009, Gutiérrez Citation2021).

Second, although the links between drugs and Colombian elites go back to the 1950s, before Colombia was a cocaine producer (Sáenz Citation2021), the combination of ferocious electoral politics, the 1970s fragmentation of national parties into regional coalitions, and the increasingly dirty counter-insurgency war, facilitated the convergence of the dominant bloc (politicians and army officers) with the mafias. One of the few scholarly accounts looking into this phenomenon from a systemic perspective -rather than as the personal proclivities of corrupt politician-, remarks that

When the drug economy hit the country by the mid ‘70s, these [political] bosses were in the midst of a ferocious competition among them for scarce votes. They needed the fresh resources offered by the narcos, and were not above getting them. The result was that the biggest party of the political system [ed. The Liberal party], and the most efficacious vote gatherer, underwent a deep transformation towards its criminalisation (Gutiérrez-Sanín et al. Citation2007, p. 23).

‘Political scandals’ such as ‘process 8000’ or the ‘Ñeñepolítica’ have stained presidential campaigns for the last 40 years with drug money, proving this is a structural problem at all levels of the State (López and Ávila, Citation2010; Rettberg Citation2011, Sáenz Citation2021). So strong is this association, that a political movement called decent ones was created -as if decency was a political programme in its own right! (El País Citation2018). In parallel, counter-insurgency brought other sectors of the State (armed forces and police) into this equation by the close association of right-wing paramilitarism (MAS, PEPEs, AUC, etc.) with the main Colombian cartels (Bowden Citation2010, López and Ávila Citation2010, CNMH Citation2013, Ronderos Citation2014, Sáenz Citation2021). Even international agencies in Colombia have been implicated in relations to the cartels: the campaign to kill Pablo Escobar relied heavily on support provided by the rival Cali cartel, and more recently, Michele Leonhart, head of the DEA, had to resign after evidence emerged that DEA agents in Colombia regularly attended sex parties with the Medellín Cartel (Davis Citation2015, Hosenball Citation2015).

The regional cocaine economies, despite their illegal nature, reproduce market dynamics in a highly stratified value-chain starting with coca cultivation and the production of base paste by the cocalero peasant. Then, the base paste is processed into cocaine, a process taking place in crystallizing facilities (cristalizaderos), where the product acquires most of its added value in the production stage. There are thousands of facilities producing base paste, but the production bottleneck is in the crystallizing facilities, which requires an investment outside the reach of the peasantry. Most of the value is not added at the stage of production, but on the trafficking stage: while the kilo of coca leaves is U$0.71, the kilo of base paste is U$500 and the kilo of cocaine is U$1.508 at the production facility. In the streets of Europe and the US, this same kilo can fluctuate between U$30,000 and U$100,000 depending on quality (UNODC Citation2020). However, the bulk of the discussion on illegal drugs focuses on the bottom of the value-chain -particularly, on cultivation (e.g., Dion and Russler Citation2008, Mejía et al. Citation2019), thus deflecting us from understanding the complexity of the value-chain and from locating the powerful actors within this chain.

4.2. Gold and illegal mining

The Andean region is very rich in gold and other minerals. The indigenous populations have been familiar with the art of goldsmithing for millennia, which reflected status, power, and devotion, but was not used for capital accumulation (Lechtman Citation1984, Citation1991, Reichel-Dolmatoff Citation1988). The myth of El Dorado, attracted the Conquistadores who exploited both the natives and imported African slaves to the mines of Iscuandé and Barbacoas, changing forever the demography of the Colombian Pacific region, developing a distinctive Afro-Colombian culture (De Friedemann Citation1974, Navarrete Citation2003). Soon, mints in Bogotá and Popayán started turning this gold into circulating capital (West Citation1972).

Precious metals were later central to the consolidation of regional economies -which functioned like ‘regional archipelagos’- that articulated slowly to national and international markets, providing the republican elites with the building blocks in the State-building process amidst a fierce fight over the control of labour and resources (Barona Citation1997).

Although mining no longer plays the central role it played in the national economy until the mid-19th century, it is still prominent in many regions: 141,000 people depend on mining, of which 74,000 depend on illegal mining. 72% of the mines in 2013, were considered small-scale, being predominantly oriented towards ‘subsistence and traditional mining’; of these, 66% were illegal (Guiza Citation2013, p. 112). According to a 2011 census, 87% of gold mines are illegal (i.e., lacking a mining title), the majority located in conflictive ‘red zones’ of Chocó, Bolívar, Cauca and Antioquia (Ibid.; OECD Citation2017). Most of the gold in the country, indeed, is produced by independent miners (small to mid-size miners without links to the State or to formal companies): according to the US Mineral Yearbook report between 2005 and 2015, they produced 80% of the Colombian gold production (in Castillo and Rubiano Citation2019).

After the global economic crisis of 2008, the sharp increase in the price of global commodities led to a drastic increase in gold exploitation in Latin America and Colombia, in particular (Idrobo et al. Citation2014, Massé and LeBillon Citation2018, Castillo and Rubiano Citation2019). The National Development Plan 2010–2014 needs to be made sense of in this context; by 2010, 4.8 million hectares of land had been given in concession to mining corporations, overlapping with ethnic and peasant territories, and with informal mining regions (Vélez-Torres Citation2014, Massé and LeBillon Citation2018). 2.1 million hectares had been granted in concession specifically to gold and precious metals mining companies in 2019, with two of them, Anglo Gold Ashanti and Continental Gold concentrating about half of this surface (Betancur Citation2019). Corporations often don’t pay taxes and only seldom pay royalties, so it has been argued that, at a dreadful social and environmental cost for communities, the State has actually ended up subsidising multinational mining, while the profits are channelled directly to national and international elites (Garay Citation2014, Vélez-Torres Citation2014).

If the regional economies of coca are diverse, this is much more the case in gold mining, which is largely concentrated in Chocó, Antioquia and Bolívar (OECD Citation2017). In Chocó, in the Pacific coast, gold panning was traditionally practised as a supplement to agriculture by former slaves, who remained autonomous in their territories thanks to this extra-income, despite the efforts of the multi-national Chocó Pacífico to control both the resources and labour in the region during the first part of the 20th century (Leal Citation2009, Castillo and Rubiano Citation2019). In North-East and Bajo Cauca of Antioquia, regions that have labelled ‘red zones’ since the 1980s (Ordóñez Citation2012), gold attracted during the 19th century peasants who settled and combined agricultural and mining activities, although in the last decades ‘pure miners’ have emerged (Lenis Citation2009, Pérez et al. Citation2009). In the South of Bolívar, towards the mid-20th century people arrived from all over to work in the gold economy, while others settled as farmers -many of them participating in the coca economy (Medina Citation2013). Other regions have witnessed a mixture of traditional and mechanised forms of mining, co-existing with farming activities as witnessed in fieldtrips in Ituango (May 2019), where fishermen supplemented their economy with gold, and Sevilla, Cauca Valley (July 2017) where dairy farmers panned gold for extra-income. Community processes, reflecting on these synergies, often refer to their economy as agro-minería (agri-mining) (cf., Vélez-Torres Citation2014, LeBillon et al. Citation2020).

While in some of these territories, the gold rush has attracted ‘outsider’ medium-scale illegal entrepreneurs to the territories, which invariably brought negative impacts, agreements with locals existed (Castillo and Rubiano Citation2019), something which seems impossible with the corporations. The recent scramble over the gold concessions attracted Gran Colombia Gold, a Canadian corporation, and the South African Anglo Gold Ashanti, to Antioquia and Bolívar, respectively, exacerbating violence. In the conflict between small-scale producers (who complain of the extreme difficulties to legalise their activities) and the corporations, the State sides squarely with the latter, putting its coercive apparatus at their service and favouring them with centuries-long concessions (Bernal-Guzmán Citation2018).

5. Demystifying illegal economies: the political process behind their criminalisation

Both the criminalisation of the cocalero and the small-scale miner have a history. Colombia’s legal regulations on narcotics started back in the 1920s, at the same time that the US developed its anti-drug legislation, becoming increasingly punitive as the century progressed (Bagley Citation2005, Uprimny et al. Citation2013, López Citation2016) -the number of people in prison for drug-related offences in Colombia grew by 289% between 2000 and Citation2015 (Chaparro and Pérez Citation2017). The National Statute on Narcotics was decreed in 1974, curiously, at the time that the first president with alleged links to drug trafficking, López Michelsen, came to power (Britto Citation2020, Sáenz Citation2021) and the most recent legal framework regulating drugs, Law 30 of 1986, was influenced by US president Reagan (Tokatlian Citation2000).

The mid-1990s cocalero marches mark the escalation of the criminalisation against these smallholders, which has been constant since (see ), except for a contradictory break in the context of the 2012–2016 peace negotiations (Acero and Machuca Citation2021). Cocalero protests were severely repressed, serving as the preamble to Plan Colombia, which aligned counter-narcotics and counter-insurgency operations (Rojas, Citation2015; Tate Citation2015, Lindsay-Poland Citation2018).

It is difficult to disaggregate displacement caused by fumigations from other causes, as counter-narcotics operations typically go hand in hand with other forms of public violence and paramilitary operations, but research show a strong correlation between fumigations, and displacement and/or other aggressions (Marín Citation2021). In Putumayo and Nariño, 35,000 families were displaced between 1999 and 2003 because of fumigations (Ceballos Citation2003). Some available figures, estimate that between 2001 and 2002, 75,597 people were directly displaced by fumigations (CODHES Citation2003). In 2008 fumigations in Antioquia and Vichada displaced 13,134 people (CODHES, Citation2008). During the Uribe government (2002–2010), the scale of fumigations reached a record high while ‘narco-peasants’ were displaced and criminalised: 2002, Uribe’s first year in government, reached a record 423,231 people forcefully displaced (Ibañez and Moya Citation2007). Meanwhile, the government repeated like a mantra that coca was the ‘plant that kills’ (la mata que mata) (Ciro Citation2018). Alongside US-sponsored Plan Colombia, the UN has promoted for the last 20 years monitoring mechanisms of coca cultivations while they are building similar tools to monitor ‘illegal’ mining (UNODC Citation2016), as part of these politics of criminalisation.

This State-led violence reflects the deep asymmetry in the distribution of rents and violence across the drug economy’s value-chain. While the rents are minimal among base paste producers, and they are massive among the final stages of production and distribution; violence, on the contrary, is massive in the lower links of the value-chain while it barely touches the higher links: trafficking and the financial tentacles of this industry.

The illegal condition of much small-mining derives from a series of changes in the legislation, which did not target small-scale mining per se, but made it in practice impossible (see ). The mining code (Law 685 of 2001) established for small-scale mining the same regulations as for the big-scale operations of multinational corporations, while the State incentivised private investments in mining and de-incentivised public mining production. According to Vélez-Torres, ‘the Colombian state has assumed the position of a broker whose main responsibility is to address the management of natural resources to attract and fulfil investors’ demands’ (Citation2014, p. 73). Later, the Decree 1102 of 2017 required mining titles for small producers, prompting two months of protests in North-Eastern Antioquia, demanding guarantees and titles for exploitation; these were met with disproportionate lethal violence by the authorities (Pareja Citation2017, Bernal-Guzmán Citation2018).

Most (90%) of the lands in which small-scale mining takes place are already under a mining concession, with the State systematically favouring big-scale mining interests (Guiza Citation2013, Betancur Citation2019, López Citation2021). The inability of small-scale producers to comply with legal requirements and the bureaucratic difficulties to legalise their operations mean that they end up being pushed into illegality (Massé and LeBillon Citation2018, Betancur Citation2019, Castillo and Rubiano Citation2019, Jonkman Citation2019).

Illegal mining -that ‘which lacks mining deeds or environmental licenses’ (Valencia Citation2017)-, operates often in areas of armed conflict. In this context, small-scale illegal mining ended up being accused of funding ‘terrorism’. Juan Carlos Pinzón, then Minister of Defence, during the parliamentary debate on legal and administrative measures against illegal mining, argued that:

(…) extortion, narcotics trafficking, and illegal mining are the source of an ever-increasing amount of funding available to armed groups resorting to terrorism to subdue the civilian population and to threaten the legitimate authority (Gaceta del Congreso, 16/09/2013, Year XXII, No 721, p.8. Our emphasis).

According to Pinzón, Plan Colombia’s alleged success against drug-trafficking forced guerrillas to look for new funding sources. Illegal mining gave these actors distinctive advantages: normative ‘anarchy’ (sic), blurry lines between legal and illegal activities, and little State control. Thus, the link between counter-narcotics operations and the new push to criminalise small-scale mining was made explicit. In recent years, the links between illegal mining and money laundering have been exploited to pressure for military responses to ‘criminal mining’ (Asobancaria, Citation2016; Montero Citation2017), although small-scale miners are not the beneficiaries from these transfers. In the aforementioned parliamentary debate, while the minister pressed for harsh measures against illegal mining, big-scale mining was praised as a pivot of ‘national development’.

The article 106 of the National Development Plan (2011–2014) of president Santos and Law 1450 of 2011 established a new regulatory framework for mining activities, which included harsher sentences for illegal mining. The discussion around mining, and the mining industry itself, became increasingly militarised since: 70,000 soldiers are part of 20 mining-energy-infrastructure battalions, two of which are exclusively devoted to the gold mining regions of Antioquia.Footnote4 Militarisation is particularly problematic considering the extensive links of the army and police with right-wing paramilitarism (Medina Citation1990, HRW Citation2001, Hristov Citation2009, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2019), and of paramilitarism with big-scale mining-extractive corporations (see Moor and Van de Sandt Citation2014, CNMH Citation2015, Betancur Citation2019) and highly destructive medium-scale mining operations in traditional small-scale mining territories (eg., Paulsen and Mosquera-Vallejo, Citation2020).

As we have discussed, there is nothing intrinsically illegal about coca or gold, no quality in them that makes them dangerous per se, or conflict-prone. As highlighted in other contexts, the definition of what is criminal can be shaped by class interests and power (Chambliss Citation1975, Thompson Citation1975). Therefore, we call the attention to the political process -which includes processes of State-building and the struggle over the control of labour and capital- by which both activities have become largely illegalised.

As a caveat, in the same way that we question the generalisation that deems all criminal activity as at the antipodes of politics, it would be equally wrong to assume that all criminal activity is political in its intent or results. What we say is that behind all criminal activity there is a political process that defines its boundaries and modalities. This process in the Colombian case is indissociable from armed conflict.

6. Conflict, the ‘refractory’ peasant and criminalisation

Colombia has experienced the longest armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere, lasting, with ebbs and flows, the best part of seven decades. Although the reasons at the root of the conflict and behind its extraordinary persistence are subject to much debate (e.g. CHCV Citation2015), its agrarian roots are beyond doubt. This conflict is linked to the colonisation of vast rural territories which until well into the 20th century were not settled. This colonisation was influenced by the opportunities opened up by the gradual integration of Colombia into foreign markets through the demand for tropical commodities such as tobacco, indigo, banana, cotton, rubber, quinine and coffee from the late 19th century onwards (LeGrand Citation1986, Rausch Citation1999, Domínguez Citation2005, Fajardo Citation2015, Tovar Citation2015, Britto Citation2020). These conditions created a highly mobile peasantry. Political upheaval and perennial conflict between the two dominant parties in Colombia (Liberal and Conservative) translated into significant bloodletting and mass displacement that exacerbated the movement of people and the expansion of the agrarian frontier, as the peasantry looked for both economic opportunities and political sanctuary whether deeper into the jungle or higher into the mountains (Molano Citation1987, Citation2017, Garzón Citation2015, Britto Citation2020). This process was further reinforced by the political decision of Colombian elites to stifle calls for agrarian reform by privileging colonisation processes into this ever-expanding agrarian frontier (Fajardo Citation2015).

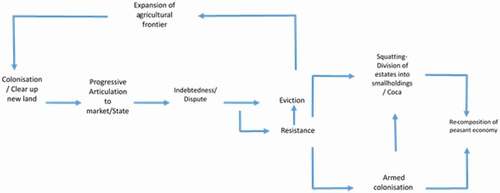

Behind this mobile peasantry came landlords and entrepreneurs, who, through debt, judicial mechanisms or naked violence, often claimed property over the lands cleared by the peasantry, therefore pushing them deeper into the jungle and thus reproducing a cycle of expansion of the agrarian frontier followed by land accumulation (Molano Citation1987, Citation1994, Fajardo Citation2009) (See ).

This cycle did not go uncontested: the insurgents have acted as a barrier against the penetration of land-grabbers and corporations into areas of colonisation (Molano Citation1994, Gutiérrez, Citation2019), while coca and mining provided viable alternatives allowing the reproduction of the family-scale economy of the smallholding peasantry. The coca economy has given these smallholders the chance to access education, health and infrastructure in the absence of State investment in rural regions. It has also given them the chance to remain in the land as a viable unit thanks to providing them with a stable market, and even aspire to some degree of social mobility; the possibilities for households headed by single mothers are also worth noting (Parada and Marín, Citation2019; Ciro Citation2020, Gutiérrez Citation2021). Illegal gold-mining has provided the peasantry with a precious opportunity to supplement their income to similar effect (Molano Citation2001, LeBillon et al. Citation2020, Paulsen-Espinoza and Mosquera-Vallejo Citation2020). Both illegal economies and insurgency underpin processes of resistance to the aforementioned pattern of land concentration, preventing the proletarianisation of rural smallholders who become a refractory peasantry, whose very existence represent a challenge to the status quo (Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2019).

6.1. More of Proudhon than Marx: refractory smallholders and the political economy of criminalisation

This relative buffer against land accumulation goes against the grain of the historical struggle of the Colombian dominant bloc to control both land and labour (LeGrand Citation1986). The Colombian conflict cannot be understood from the angle of proletariat versus bourgeoisie: although the Marxism-Leninism of the Colombian rebels cannot be treated as a deceptive and irrelevant ideological artifact (see Ferro and Uribe Citation2002, Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2003, Citation2019), guerrillas, with the exception of the region of Urabá (García Citation1996, Ortiz Citation2007, Carroll Citation2011), had scarce, if any, support among the proletariat to which Marxism-Leninism primarily aimed at. It had, instead, significant support among the smallholding peasantry in areas of colonisation (Gutiérrez-Sanín Citation2019), a situation which was not unique to Colombia (Shanin Citation1966, Popkin Citation1979, Skocpol Citation1982, Kalyvas Citation2015).

In Cauca Valley, for example, unlike the smallholders of the Andean slopes, the mass of landless wage earners working for the sugar industry were largely uninfluenced by the insurgency (Vega and Gutiérrez Citation2019). Likewise, there is significant evidence that the bulk of the political support to the guerrillas in coca producing regions came from smallholders who had some land (often very little, indeed), much more than from the raspachines, the floating population that comes and goes harvesting the coca leaf (Ferro Citation2004, Gutiérrez Citation2021). In the case of gold, judging from our experience in mining regions (Bolívar and Cauca Valley), the bulk of the support for insurgency came from small-scale miners and from smallholders that engaged in mining activities as a supplement to their income (cf. Molano Citation2001).

The political imagination of the settler peasantry at the bottom of this value-chain, a view of independent smallholdings articulated by links of collective solidarity, and by a sense of industry and social justice, resembles quite closely the view of Proudhon, according to which property (possession) and liberty are indissociable: ‘When property is widely distributed, society thrives, progresses, grows, and rises quickly to the zenith of its power (…) When property is concentrated, society, abusing itself, polluted, so to speak, grows corrupt, wears itself out (…) plunges into long-continued and fatal luxury’ (Proudhon Citation2011, p. 141). This Proudhonian take on property, and particularly on the land question, was articulated in his classic work Qu’est-ce que la propriété? [1840], in which he argued:

the man who takes possession of a field, and says, “This field is mine,” will not be unjust so long as everyone else has an equal right of possession; nor will he be unjust, if, wishing to change his location, he exchanges this field for an equivalent. But if, putting another in his place, he says to him, “Work for me while I rest,” he then becomes unjust, unassociated, unequal. He is a proprietor.

Reciprocally, the sluggard, or the rake, who, without performing any social task, enjoys like others -and often more than others- the products of society, should be proceeded against as a thief and a parasite (…) (Ibid:129-130)

This view was disparaged by Marx as petty-bourgeois, yet, it rings a much stronger bell with the project devised in the agrarian programme of Marquetalia, the foundational document of the FARC-EP, than the Communist Manifesto. And it is this view that, to a degree, has been possible to articulate at the local-level thanks to the smallholders resorting to illegal economies.

If the illegal economies offer smallholders opportunities for their reproduction, they offer bigger opportunities for the elites: after all, the part of the value-chain controlled by the peasantry is the weakest link. Illegal economies are scenarios of class struggle too -although not, as we’ve said, in the sense of proletariat vs. bourgeoisie. This struggle between oligarchs and small property owners who, more often than not, have informal deeds and extra-legal claims to their land, hovers around the distribution of rents, mechanisms of social mobility and access to resources and labour.

Criminalisation concentrates the risks associated to the illegal economies’ value-chain at the bottom and the profits at the top. In this pattern of accumulation, the smallholder -constantly under threat of displacement- can have a low margin for their reproduction, while the elites can profit from the more lucrative processing of goods produced by precarious and criminalised labour. Likewise, given their status and political power, elites can transfer rents from the illegal to the legal spheres (Ciro Citation2020).

6.2. A moral crusade: counter-insurgency meets the struggle against illegal economies

The refractory peasantry has resisted this pattern of accumulation/criminalisation resorting throughout history to various mechanisms, ranging from the so-called ‘weapons of the weak’ and the ‘hidden transcripts’ (cf. Scott Citation1985, Citation1990) to open rebellion (Sánchez Citation1977, Fajardo Citation1978, Citation2015, LeGrand Citation1986, Molano Citation1994). But their engagement in criminalised economies could also be regarded as a form of resistance, not explicitly as in other contexts (Crummey, Citation1986), but in the sense that, by escaping State regulation and countering the land-grabbing cycle, it allows them to remain independent producers. If open rebellion is almost universally treated by Statesmen -even by some scholars (Collier Citation2000)- as nothing more than criminality, criminalising economic activities is not so straightforward, producing significant institutional tensions.

Cocaine production was already criminalised by the time that a proportion of the peasantry embraced it as a mechanism for their survival as individuals and as class. This, however, was not the case with traditional and informal mining. Its criminalisation was a response of the elites to an economic activity that escaped their control and challenged their vision of development as enshrined in the National Development Plan 2010–2014, which described big-scale mining as a pivot (locomotora) of national development and which foresaw giving away significant portions of the territory on mining concession to big multinational players (Departamento Nacional de Planeación Citation2010), at the expense of other actors (i.e. ethnic communities and peasantry) living in those territories (Vélez-Torres Citation2014).

In order to justify this push towards the criminalisation of activities that, per se, are not necessarily criminal, these activities need to be demonised. It is not enough to present them as outside the regulatory framework of the State, or not paying taxes or royalties -something most of the legal big mining operations in Colombia seldom, if ever, do (Garay Citation2014, Vela-Almeida et al. Citation2021). They need to be presented as enemies of the nation by their association to the guerrillas, who had been systematically presented for over a decade as an existential threat (Centeno et al. Citation2013).

Presenting smallholders in criminalised economies as natural allies of the insurgency is credible because their activities take place typically in rural regions where guerrillas have an actual influence, and often regulate these industries.Footnote5 Thus, the fight against criminalised activities becomes more than an ordinary fight against crime: it becomes a moral crusade. The argument of combatting the ‘funding sources of terrorism’ through the criminalisation of small-scale miners, made available the repressive tools developed over decades of counter-insurgency for this purpose.Footnote6

There’s a wealth of conflict research literature that severs the link between illegal commodities and the historical and social context in which they are produced. Gold or cocaine are reified as representing in themselves the cause for conflict, which is reduced, a-la-Collier, to merely a rent-seeking enterprise (e.g., Idrobo et al. Citation2014, Maldonado and Rozo Citation2014, Escobedo and Guío Citation2015, Ortiz-Riomalo and Rettberg Citation2018). According to this perspective, the firm arm of the law should suffice to solve these conflicts. Based on our evidence, we claim that it is the very nature of the mining and drug legal frameworks what is at the heart of these territorial dynamics of social, environmental, and armed conflict. We can affirm, in this case, with Walter Benjamin (Citation1996) that it is not the absence of the law, but its very existence that creates conflict.

7. The Tillyian lens: criminalisation, resistance and state-building

The characterisation of these regions as ‘red zones’ (i.e., wild, lawless) legitimates the State’s strategy of ‘total war’, encompassing surveillance, terror, displacement, murder, bombings, fumigations and even infanticide (Lindsay-Poland Citation2018, Daniels Citation2021). Constitutional guarantees are suspended, and the criminalised peasant becomes subject of a mixture of conditional, paternalistic, and violent policies (Ciro Citation2018). Against this backdrop, there is a copious scholarly literature in Colombia to understand the relationship between the State and these ‘red zones.’ Most of the literature describe the State as being absent from these territories, or being weak (e.g., Pécaut Citation1989, Pizarro Citation2004, McDougall Citation2009, Duncan Citation2013, Giraldo Citation2013, Revelo and García Citation2018); often, the two demons, ‘State absence’ and ‘illegal economies’, are regarded as mutually reinforcing: ‘In stateless areas of Colombia, rebel consolidation tends to take place in areas where the drug trade is also present’ (McDougall Citation2009, p. 322). Over the last two decades this claim has been subject to scrutiny and critical analysis (González et al. Citation2003, González Citation2014, Ciro Citation2016, Ballvé Citation2020).

Our proposition to this debate, drawing critically from Tilly (Citation1985, p. Citation1992), is rather simple: these regions are not a blank slate where the State is (half or totally) present or not. These regions are the product of a particular form of State-building which re-creates a centre/periphery divide through the conflicts, interactions and negotiations of fragmented elites, as well as by the resistance of a refractory peasantry and regional subaltern groups to a specific pattern of accumulation.

7.1. Rendering the state visible

Although the activities at the bottom of the value-chain in these illegal economies take place in regions considered as hinterlands, contrary to the ‘absence of State’ literature, they are tightly imbricated with international and national markets (where, indeed, most of the value is produced) and with the legal, executive and legislative apparatuses of the State (cf. Domínguez Citation2005). Notwithstanding high levels of informal employment and unemployment, the State administration and mining-extractive industries, are the most important economic activities.Footnote7 The invisibilisation of the State is, in our opinion, partly the product of an over-normative notion of the State in Colombia, with functionalist overtones (cf. Ramírez Citation2015). Also, the focus on ‘non-State armed actors’ in relation to these economies has deflected the attention from the role of legal actors, and indeed the State. Thus, these narratives are limited to advocating a strengthening of the State presence -without problematising the State as such or the many ways in which the State actually operates in these territories and contributes to shaping them.

In order to grasp the ways in which State-building takes place in these ‘red zones’, we need to state the obvious: what is legal and illegal is defined in scenarios where political and economic powers are accumulated. Criminalisation is, indeed, devised by the State apparatuses (Hibou Citation2013). One of these, the national parliament, is a paradigm of the link between mafias and political power (López and Ávila Citation2010, Romero Citation2011). Here, the sphere of ‘criminality’ is demarcated through policies, laws, assistance programmes, decrees, etc., impacting on the workings of illegal economies and contributing to their regulation -how the rents of illegal markets are distributed, how the social costs of these are shared (including who and how gets punished). In this sense, what is sometimes depicted as ‘borderland battles’ (Idler Citation2019) is merely the local expression of battles, which, indeed, take place in the very ‘belly of the beast’, so to speak.

These designs at the centre of the national stage do not go uncontested. When cocaleros call coca the ‘resistance crop’, this has two meanings: a commodity that allows the smallholding peasantry to be reproduced as a class, as aforementioned, but also, an activity that allows them some autonomy from central government (Ciro Citation2020, Gutiérrez Citation2021). The same can be said about gold mining, as in many regions, small-scale miners have resisted through a broad repertoire that includes engagement with and contestation of this legal framework, to open mobilisation (Medina Citation2013, Jonkman Citation2019). Guerrillas in mining regions of Vichada and Guainía were described by Jorge Orlando Melo as ‘puritans’: ‘they have banned prostitution and dream of housing developments where miners can live with their wives and children, so they can “save money and get ahead”’ (in Molano Citation2001, p. 11).

The very existence of these criminalised economies, moreover, gives these smallholding peasants, traditionally excluded from the political channels of representation and often ignored as a political subject (Gutiérrez-Sanín, Citation2015), a leverage to be rendered visible to the State. For communities engaged in illegal activities, the attention this fact draws from central authorities gives them the chance to enter into negotiations with them on State-building in their ‘peripheries’, on social and economic development, on political representation. For decades, representatives of illegal economies have negotiated -rather unsuccessfully- with State these questions on behalf of the ‘peripheries’, giving them precarious representation mechanisms denied in practice by the formal political system (cf., Ramírez Citation2011).

7.2. The Tillyian process in Colombian perspective

This combination of top-down violence and bottom-up resistance as a State-building process resonates strongly with the ideas of Charles Tilly, who provocatively referred to State-building as organised crime and to the State as an organised racket (1985). He argued that from the late Middle Ages in Western Europe, power holders made war against one another; to fund the belligerent effort, they had to extract resources from the populations under their control, and borrow from bourgeois lenders. This strengthened centralisation and the bureaucratic machinery of modern States, leading inadvertently to State-making, that is, the elimination of the rivals of the elites in those territories over which they claim authority (Citation1985; Citation1992). For Tilly, violence and coercion lie at the heart of the State-making process. Coercion can be effective, but it can also lead to contestation and resistance, which in turn triggers its own specific dynamics into the State-building process. In Tilly’s view, popular resistance to war-making and State-making translated into concessions from rulers, limiting both activities and defining a system of entitlements that lays at the base of the modern democratic State. Other authors too have argued that the emergence of modern States and modern armies, while mutually reinforcing one another, gave rise to the notion of citizenship rights (Mann Citation1987, Giddens Citation1985, Tarrow Citation2015).

Though Tilly himself warned us that his model should be applied with great caution outside of Western Europe (1992), his model has been applied to a wide range of countries and contexts over the decades with varying degrees of success -or lack of (Barkey Citation1994, Reno Citation1998, Herbst Citation2000, Heydemann Citation2000, Centeno Citation2002, Leander Citation2004, Hui Citation2005, Taylor and Botea Citation2008, Cheeseman et al. Citation2018). This research has highlighted that context and a number of accessory mechanisms were dependant for the process to lead to the outcome described by Tilly. And although his model has been subject to persuasive criticism on a number of grounds including in the Western European cases he analyses (e.g., Kaspersen and Strandsbjerg Citation2017), it nonetheless provides valuable insights to understand the relationships between seemingly antinomic terms: crime and State-building, organised violence and citizenship.

We argue that the full value of Tilly’s insights got lost by a tendency to treat them as a model to be rejected or accepted in toto. Instead, we separate what we call the Tillyian process (the process of war-making, capital accumulation and State-building) from the Tillyian effect (the emergence of centralised nation-States with a strong bureaucracy and the emergence of democracy), to understand the link between conflict, criminality and political power in Colombia.

Here, we identify a Tillyian process without a Tillyian effect; that is, the process of war-making, State-building and capital accumulation go hand in hand, as already described, with the ‘organised crime’ metaphor being quite literal given the extensive links of the elites to mafias. However, the result of this process is not a strong democracy or even a centralised State as Tilly describes. What we have is a State dominated by fragmented but powerful regional-national coalitions, which systematically excludes significant sectors of the population by a number of mechanisms, including criminalisation -effectively turning whole categories of inhabitants into non-citizens. The demands of these non-citizens hover around their aspirations for social recognition, inclusion, infrastructure, and a vision for an alternative, rights-based, form of State-building (Jaramillo et al. Citation1986; Zamosc, Citation1986, García Citation1993, Ramírez Citation2011). In this sense, their ‘State-nostalgia’ (Ballvé Citation2020) represents an aspiration more than an endorsement of the actually-existing-State (cf. Ramírez Citation2015).

Tilly himself gave us a clue to understand this disjunction, in his definition of one of the State-building activities: protection. Rulers engage in protection by ‘(e)liminating or neutralizing the enemies of their clients’ (1985:181). Here, we need to go back to the political process behind criminalisation of illegal economies -who are the clients of the ruling bloc? who are the enemies of these clients? This requires to delve deeper into the nature of these regional and national elites, and into their complex and conflictive relationship with the criminalised subaltern dependant on illegal economies. Elucidating how criminalisation (in some cases) and strategic tolerance (in others) are used as protection mechanisms to the interests of the ruling bloc’s clients, is crucial to understand how the Tillyian process has unfolded in Colombia with effects very different to those devised by Tilly.

8. Concluding remarks

We have argued that there is an intimate link between the criminalisation of economic activities, patterns of capital accumulation and the dynamics of political power in Colombia. This link has been distorted in the literature, by an almost exclusive emphasis in focusing on ‘non-State armed actors’ in relation to illegal economies; by ignoring the length of the illegal value-chains by focusing on the lowest links in the ‘peripheries’; and by a reification of the illegal economies, which obscures the political process behind criminalisation. The criminalisation of the cocaleros and small-scale miners -indeed, their conflation with ‘terrorism’- is a process taking place at the heart of power structures, impacting how the violence and rents of illegal economies are distributed unevenly throughout the value-chain.

More than ‘new data’ (enough data is already out there), what we need is a new prism to look at the problem, for the conceptual tools we have at present are sorely ineffectual in order to give account of complex realities on the ground in conflict contexts such as Colombia. In this paper, we have set ourselves the task of delineating some basic elements for that prism. We propose to question the artificial dichotomy of legal/illegal as two distinct forms of economies or spheres of interaction, a distinction even more arbitrary in a country where the lines between both are blurry, to say the least, if not mutually constitutive. We also propose to critically examine centre/periphery distinctions -recently rekindled in the ‘borderlands’ literature (e.g., Idler Citation2019, Bhatia et al. Citation2021)- by understanding how both integrate through State-building mechanisms.

Illegal economies in Colombia exist as part of broader State-building processes and capital accumulation patterns, linking the regional to the national, through criminalisation, resistance, claims-making, militarisation, and the many opportunities available to the elites to legalise illegal rents. The specific modalities through which this happens, understanding the clientelistic networks of the various fragments and sections of the ruling bloc, exploring the contents of the various claims articulating to State-building demands, are among the many issues to advance in future research in this direction utilising this prism.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patricia Correa and Maira Triana for their assistance. Thanks to Michael Mann, Siniša Malešević, Jenny Pearce, Christian Olsson, Ana María López and Francisco Gutiérrez-Sanín for their most invaluable feedback during the ‘Political Power, Criminality and Conflict’ workshop (10/06/2021) and on subsequent drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

José A. Gutiérrez

José A. Gutiérrez Sociologist, researcher and lecturer. He has worked extensively on the Colombian conflict on issues related to governance and state-building. He has experience in Ireland, the EU, Kenya and Indonesia on development research. Currently he works in Teagasc, the Agriculture and Food Development Authority (Ireland) as post-doctoral research fellow.

Estefanía Ciro

Estefanía Ciro Research coordinator on drug trafficking, cocaine economies and war on drugs in the Truth Commission (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad), Colombia. Researcher at the Colombian Amazonian Think-Tank AlaOrillaDelRío. UNESCO Juan Bosch Prize Winner (2018). Political and social sciences PhD at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (2016).

Notes

1. In Colombia there are many irregular armed groups, with various organisational structures, constituencies, differential links to State institutions and wildly diverging political commitments. As such, to collapse them all into the category of ‘non-State armed groups’ clusters together group that have little in common, obscuring both the dynamics of conflict and the State’s role in it.

2. US Congress, ‘Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA Patriot Act) Act of 2001. Public Law 107–56. 107th Congress. 26 October 2001.

3. Narco-terrorism was used in the 1980s to describe Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel in their gruesome war against president Barco’s agreement of extradition with the US. However, the US ambassador Lewis Tamb has already referred to Colombian guerrillas as narco-guerrillas back in 1984 (Tokatlian Citation2000).

4. See the presentation of the Department of Defence (circa 2018) http://proyectos.andi.com.co/Documents/CEE/Colombia%20Genera%202015/Viernes/JoseJavierPerez.pdf

5. Right-wing paramilitaries regulate these activities in certain regions, but does not seem to bother too much the Colombian establishment, who shows a strategic tolerance in these cases.

6. For these debates in the Colombian parliament, see Gaceta del Congreso (03/08/2009. Year XVIII, No 673), Gaceta del Congreso (02/08/2010. Year XIX. No 476), Gaceta del Congreso (07/07/ 2013. Year XXII. No 471) and Gaceta del Congreso (16/09/ 2013. Year XXII, No 721).

7. See for instance, the central bank economic reports for some of these regions -Informe de Coyuntura Económica (Banco de la República de Colombia). We checked the reports of Chocó, Caquetá, Guainía, Guaviare, Putumayo, Vaupés y Vichada for 2013 and 2014.

References

- Acero, C. and Machuca, D., 2021. The substitution program on trial: progress and setbacks of the peace agreement in the policy against illicit crops in Colombia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 89, 103158. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103158

- Arias, F., 2019. Fudat, Nueva Fuerza contra Minería Ilegal. El Colombiano, 11th May.

- Asobancaria, 2016. Riesgo de Lavado de Activos y Financiación del Terrorismo en el subsector de extracción y comercialización de oro. Bogotá: Asobancaria.

- Bagley, B., 2005. Drug trafficking, political violence, and US policy in colombia under the clinton administration. In: C. Rojas, and J. Meltzer, eds. Elusive peace. International, National, and Local Dimensions of Conflict in Colombia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 21–52.

- Ballvé, T., 2020. The frontier effect. State formation and violence in Colombia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Barkey, K., 1994. Bureaucrats and bandits. The ottoman route to state centralization. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Barona, G., 1997. Economía Extractiva y Regiones de Frontera: el Papel Subsidiario de la Minería en la Formación de un Sistema Económico Regional. Historia Crítica, 14 (14), 25–52. doi:10.7440/histcrit14.1997.02

- Benjamin, W., 1996. M. Jenning, ed. Selected writings. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1913-1926

- Bernal-Guzmán, L., 2018. Minería de Oro en el Nordeste antioqueño: una Disputa Territorial por el Desarrollo. Gestión Y Ambiente, 21 (2), 74–85. doi:10.15446/ga.v21n2supl.77865

- Betancur, M., 2019. Minería del Oro, Territorio y Conflicto en Colombia. Bogotá: HBS.

- Bhatia, J., et al., 2021. Drugs, conflict and development. International Journal of Drug Policy, 89, 103212. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103212

- Bowden, M., 2010. Matar a Escobar: la Cacería del Hombre más Buscado del Mundo. Bogotá: Ingram.

- Britto, L., 2020. Marihuana Boom: the Rise and Fall of Colombia´s First Drug Paradise. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Carroll, L., 2011. Violent Democratization. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Castillo, A. and Rubiano, S., 2019. La Minería de Oro en la Selva. Bogotá: Uniandes.

- Ceballos, M., 2003. Plan Colombia: contraproductos y Crisis Humanitaria. Fumigaciones y desplazamiento en la frontera con Ecuador. Bogotá: CODHES.

- Centeno, M., 2002. Blood and debt. War and the Nation-State in Latin America. University Park (Pennsylvania): Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Centeno, M., Cruz, J., Flores, R., and Silva, G., 2013. Internal Wars and Latin American Nationalism. In: J. Hall, and S. Malešević, eds. Nationalism and war. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 279–305.

- Chambliss, W., 1975. Toward a Political Economy of Crime. Theory and Society, 2 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 149–170. doi:10.1007/BF00212732

- Chaparro, S. and Pérez, C., 2017. Sobredosis Carcelaria y Política de Drogas en América Latina. Bogotá: Dejusticia.

- CHCV, 2015. Contribución al Entendimiento del Conflicto Armado en Colombia. Bogotá: Desde Abajo.

- Cheeseman, N., Collord, M., and Reyntjens, F., 2018. War and democracy: the legacy of conflict in East Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies, 56 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 31–61. doi:10.1017/S0022278X17000623

- Ciro, C., 2016. Unos Grises muy Verracos. Bogotá: Ingeniería Jurídica.

- Ciro, E., 2018. Las tierras profundas de la “lucha contra las drogas” en Colombia: la ley y la violencia estatal en la vida de los pobladores rurales del Caquetá. Revista Colombiana de Sociología, 41 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 105–133.

- Ciro, E., 2020. Levantados de la Selva: vidas y Legitimidades de la Actividad Cocalera. Bogotá: Uniandes.

- CNMH, 2013. ¡Basta Ya! Bogotá: CNMH.

- CNMH, 2015. Con Licencia para Desplazar. Bogotá: CNMH.

- CODHES, 2003. Codhes Informa No. 44, 28th April.

- CODHES. 2008. Tapando el Sol con las Manos: informe sobre el Desplazamiento Forzado. Conflicto Armado y Derechos Humanos, January-June.

- Collier, P., 2000. Rebellion as a Quasi-criminal activity. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 44 (6), 839–853. doi:10.1177/0022002700044006008

- Collier, P. and Hoeffler, A., 1998. On economic causes of civil wars. Oxford Economic Papers, 50 (4), 563–573. doi:10.1093/oep/50.4.563

- Cramer, C., 2002. Homo economicus goes to war: methodological individualism, rational choice and the political economy of war. World Development, 30 (11), 1845–1864. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00120-1

- Crummey, D., 1986. Banditry, Rebellion and Social Protest in Africa. London: James Currey.

- Daniels, J., 2021. Colombia defence chief calls children who died in bombing “machines of war”, The Guardian, 11th March.

- Dávalos, L., Sánchez, K., and Armenteras, D., 2016. Deforestation and coca cultivation rooted in twentieth-century development projects. BioScience, 66 (11), 974–982. doi:10.1093/biosci/biw118

- Davies, P., 2006. Exploratory research. In: V. Jupp, ed. The SAGE dictionary of social research methods. London: Sage, 111–112.

- Davis, J., 2015. Michele Leonhart, head of D.E.A., to retire over handling of sex scandal. The New York Times, 21 st April.

- Davis, D., et al., 2016. A great perhaps? Colombia: Conflict and convergence. London: Hurst.

- de Defensa, M., 2003. Política de Defensa Y Seguridad Democrática. Bogotá: Presidencia de la República.

- De Friedemann, N., 1974. Minería, Descendencia Y Orfebrería Artesanal. Litoral Pacífico, Colombia, Bogotá: UNAL.

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación, 2010. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2010-2014 ‘Prosperidad para Todos’. Bogotá: DNP.

- Dion, M. and Russler, C., 2008. Eradication efforts, the state, displacement and poverty: explaining coca cultivation in Colombia during plan Colombia. Journal of Latin American Studies, 40 (3), 399–421. doi:10.1017/S0022216X08004380

- Domínguez, C., 2005. Amazonía Colombiana: economía Y Poblamiento. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

- Duncan, G., 2013. La división del trabajo en el narcotráfico: mercancía, capital Y geografía del Estado. In: J. Giraldo, ed. Economía Criminal Y Poder Político. Medellín: EAFIT, 113–160.

- El País, 2018. Candidatos de ‘Lista de la decencia’ firmaron pacto contra privilegios del Congreso. El País, 5th February.

- El Tiempo, 2020. El Control del Narcotráfico, la Gasolina que Atiza la Guerra en Cauca. El Tiempo, 21st April.

- Escobedo, R. and Guío, N., 2015. Oro, Crimen Organizado Y Guerrillas en Quibdó. Bogotá: FIP.

- Espectador, E., 2015. ‘Gobierno Declara “Objetivo de Alto Valor” a la Minería Criminal’, El Espectador, 30th July.

- Fajardo, D., 1978. Lucha de Clases en el Campo Tolimense. Estudios Marxistas, 15, 3–32.

- Fajardo, D., 2009. Territorios de la Agricultura Colombiana. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

- Fajardo, D., 2015. Estudio sobre los Orígenes del Conflicto Social Armado, Razones de su Persistencia Y sus Efectos más Profundos en la Sociedad Colombiana. In: Contribución al Entendimiento del Conflicto Armado en Colombia. Bogotá: Desde Abajo, 361–419.

- Ferro, J., 2004. Las Farc Y su Relación con la Economía de la Coca en el Sur de Colombia: testimonios de Colonos Y Guerrilleros. In: G. Sánchez, and E. Lair, eds. Violencias y Estrategias Colectivas en la Región Andina: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela. Bogotá: Norma, 411–441.

- Ferro, J. and Uribe, G., 2002. El Orden de la Guerra. Bogotá: CEJA.

- FIP, 2021. La Segunda Marquetalia: disidentes, Rearmados Y un Futuro Incierto. Serie Informes, 34.

- Fukuyama, F., 1992. The end of history and the last man. New York: Free Press.

- Garay, J., 2014. Minería en Colombia. Daños Ecológicos y Socio-Económicos Y Consideraciones sobre un Modelo Minero Alternativo. Bogotá: Contraloría General de la República.

- García, C., 1993. El Bajo Cauca Antioqueño. Bogotá: CINEP.

- García, C., 1996. Urabá. Región, Actores Y Conflicto. Bogotá: INER-CEREC.

- Garzón, S., 2015. Del patrón- Estado al Estado-patrón. La agencia campesina en las narrativas de la reforma agraria en Nariño. Bogotá: UNAL.

- Garzón, J., Cajiao, A., Cuesta, I., Prada, T., Silva, A., Tobo, P., and Zárate, L., 2021. Inseguridad, Violencia y Economías Ilegales en las Fronteras. Bogotá: FIP.

- Giddens, A., 1985. The nation-state and violence. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Giraldo, J., 2013. El Gobierno del Oro en el Bajo Cauca. Una lectura Weberiana sobre la Explotación Aurífera Aluvial no Legal. In: J. Giraldo, ed. Economía Criminal Y Poder Político. Medellín: EAFIT, 33–68.

- González, F., 2014. Poder Y Violencia en Colombia. Bogotá: CINEP.

- González, F., Bolívar, I., and Vásquez, T., 2003. Violencia Política en Colombia. De la Nación Fragmentada a la Construcción de Estado. Bogotá: CINEP.

- Gootenberg, P., 2008. Andean cocaine: The making of a global drug. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Grajales, J., 2017. Gobernar en Medio de la Violencia. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario.

- Guáqueta, A., 2003. The Colombian Conflict: political and Economic Dimensions. In: K. Ballentine, and J. Sherman, eds. The political economy of armed conflict: Beyond greed and grievance. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 73–104.

- Guiza, L., 2013. La Pequeña Minería en Colombia: una Actividad no tan Pequeña. Dyna, 181, 109–117.

- Gutiérrez, J., 2020. Toward a new phase of Guerrilla warfare in Colombia? The reconstitution of the FARC-EP in perspective. Latin American Perspectives, 47 (5), 227–244. doi:10.1177/0094582X20939118

- Gutiérrez, J., 2021. “Whatever we have, we owe it to coca.” Insights on armed conflict and the coca economy from Argelia, Colombia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 89, 103068. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103068

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., 2003. Criminal rebels? A discussion of war and criminality from the Colombian experience. London: LSE.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., 2015. ¿Una Historia Simple?’. In: Comisión Histórica del Conflicto Y sus Víctimas. Contribución al Entendimiento del Conflicto Armado en Colombia. Bogotá: Desde Abajo, 521–561.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., 2019. Clientelistic warfare. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., 2020. ¿Un Nuevo Ciclo de la Guerra en Colombia? Bogotá: Debate.

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., 2021. Mangling Life-Trajectories: institutionalized Calamity and Illegal Peasants in Colombia. Third World Quarterly, forthcoming. 1–20. doi:10.1080/01436597.2021.1962275

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F., Acevedo, T., and Viatela, J., 2007. Violent liberalism? State, conflict and political regime in Colombia, 1930-2006. Crisis states research centre working paper No. 19, London: LSE.

- Gutiérrez, J. and Thomson, F., 2021. Rebels-Turned-Narcos? The FARC-EP’s political involvement in Colombia’s cocaine economy. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 44 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 26–51. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1793456

- Harvey, D., 2005. A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hawdon, J., 1996. Cycles of deviance: structural change, moral boundaries, and drug use, 1880–1990. Sociological Spectrum, 16 (2), 183–207. doi:10.1080/02732173.1996.9982128

- Herbst, J., 2000. States and power in Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Heydemann, S., 2000. War, institutions and social change in the Middle East. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hibou, B., 2013. De la Privatización de las Economías ala Privatización de los Estados. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Hobsbawm, E., 2007. Globalisation, democracy and terrorism. London: LB.

- Hosenball, M., 2015. DEA chief to step down, congress probes sex party leaks. Reuters.com, 21st April.

- Hristov, J., 2009. Blood and capital: The paramilitarization of Colombia. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- HRW, 2001. The “Sixth Division”. New York: HRW.

- Hui, V., 2005. War and state formation in ancient China and early modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ibañez, A. and Moya, A., 2007. La Población Desplazada en Colombia: exámen de sus Condiciones Socioeconómicas Y Análisis de las Políticas Actuales. Bogotá: DNP.

- Idler, A., 2019. Borderland battles. violence, crime, and governance at the edges of Colombia’s war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Idrobo, N., Mejía, D., and Tribin, A., 2014. Illegal gold mining and violence in Colombia. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 20 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 83–111. doi:10.1515/peps-2013-0053

- Jaramillo, J., Mora, L., and Cubides, F., 1986. Colonización, Coca Y Guerrilla. Bogotá: UNAL.

- Jonkman, J., 2019. A different kind of formal: bottom-up state-making in small-scale gold mining regions in Chocó, Colombia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6 (4), 1184–1194. doi:10.1016/j.exis.2019.10.014

- Kaldor, M., 2001. New & Old Wars. Cambridge: Polity.

- Kalyvas, S., 2001. “New” and “Old” Civil wars: a valid distinction? World Politics, 54 (1 State, Political Power and Criminality in Civil War), 99–118. doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0022

- Kalyvas, S., 2015. Rebel governance during the Greek civil war. In: A. Arjona, N. Kasfir, and Z. Mampilly, eds. Rebel governance in civil war. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1942–1949

- Kaspersen, L. and Strandsbjerg, J., 2017. Does war make states? Investigations of Charles Tilly’s historical sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leal, C., 2009. La Compañía Minera Chocó Pacífico Y el auge del platino en Colombia, 1897-1930. Historia Crítica, 362 (39E), 150–164. doi:10.7440/histcrit39E.2009.08

- Leal, K., 2021. El enemigo de la construcción de la paz es el narcotráfico. Presidente Duque: Rcnradio.com.

- Leander, A., 2004. Wars and the un-making of states: taking Tilly seriously in the contemporary world. In: S. Guzzini, and D. Jung, eds. Contemporary security analysis and copenhagen peace research. London: Routledge, 69–80.