ABSTRACT

Anchored in a ‘core story’ of childhood development, ‘the biology of adversity and resilience’ (TBOAR) is an emerging scientific paradigm that seeks to explain how and why adverse childhood experiences have consequences in the form of negative ‘outcomes’ that span health and behavioural problems. In this article, Two Fuse bring TBOAR into conversation with an alternative way of producing knowledge about childhood adversity: an arts and education programme called Boys in the Making, which sees groups of boys and young men come together to collectively explore how a boy is shaped by and influences the world he lives in.

1. Introduction

As an ongoing collaboration between Fiona Whelan and Kevin Ryan, Two Fuse is committed to thinking across the boundaries of disciplinary enclosures. Two Fuse is also a way of acknowledging the relational nature of critical inquiry – that the pursuit of knowledge and understanding entails both direct and indirect encounters and exchanges that span self-other-world. In the dialogue below, Two Fuse bring science, collaborative arts, and community-based youth work into a conversation with a view to exploring different ways of understanding and publicly communicating childhood adversity.

Kevin works in the discipline of sociology, and is currently writing a critical genealogy of the emerging scientific paradigm known as ‘the biology of adversity and resilience’ (TBOAR), which seeks to explain how and why adverse childhood experiences have consequences in the form of negative ‘outcomes’ that span health and behavioural problems.

Fiona is an artist, writer and educator, whose practice is committed to exploring, exposing and reconfiguring power relations through durational engagements with people and place. Core to her practice is an 18-year engagement with Rialto Youth Project (RYP). Based in the Rialto inner-city area of Dublin in the Republic of Ireland, RYP are partners in developing Boys in the Making, which is a dynamic programme for boys and young men, and which sees groups come together to co-create a boy and explore his needs and experiences as he interacts with the world around him.

To provide some context before commencing with the dialogue itself, the Boys in the Making programme forms part of a long-term multi-layered project called What Does He Need?, which commenced in 2018 as a collaboration between Fiona Whelan, Rialto Youth Project and theatre company Brokentalkers.Footnote1 Operating at the intersection of collaborative arts practice, performance, qualitative research and youth work, the project aims to create a public dialogue about the current state of masculinity. The Boys in the Making strand of the project is explicitly pedagogical, underpinned by the core values of youth work as promoted by the National Youth Council of Ireland: empowerment of young people, equality and inclusion, respect for all young people, involvement of young people in decision-making, partnership and voluntary participation.Footnote2 Related to this, the Boys in the Making programme seeks to support children and young people to understand the complexities of their gender position and its intersection with other forms of inequality.Footnote3

As with other scientific paradigms, the emergence of TBOAR has been gradual, and it is worth noting that as recently as 2012, TBOAR was referred to in the primary literature as ‘the new biology of social adversity’ (see Boyce et al. Citation2012). The ‘new’ has since been dropped, and adversity is now coupled to ‘resilience’, which is something we return to at the end of our dialogue below, as this can be seen to map onto a longstanding issue of concern to social scientists, and sociologists in particular, i.e. ‘structure’ and ‘agency’, which in turn helps to understand how power relations are configured in the context of TBOAR and Boys in the Making.

The relationship between TBOAR and Boys in the Making is one of difference extending to scale, scope, location, and funding.Footnote4 Although they share a core concern – the formative experiences of children, and the social conditions that shape those experiences – they exist independently of each other. Boys in the Making is a local place-based programme, while TBOAR is anchored in a constellation of research centres/institutes, and disseminated through international networks, academic journals, and communication strategies intended to translate the science into public policy. By bringing programme and paradigm into dialogue, we aim to cast a critical light on what can be described (borrowing from Michel Foucault Citation1980) as a specific field of power/knowledge. TBOAR is a story of childhood development and social adversity that transcends context and claims universal normative validity, while Boys in the Making is about embodied and situated stories that occupy a subaltern position relative to TBOAR, and which are narrated through a performative mode of communication that spans collaborative arts and community-based youth work.

In the first section of the dialogue below we discuss an online resource relating to TBOAR called Charlie’s storyFootnote5 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxXLHpt0iEo] and also a poem called Stevie, written by a group of young men, as part of the Boys in the Making programme [https://www.whatdoesheneed.com/stevie-2/ see also ]. We invite readers to do a bit of preparation by reading/watching these two ways of figuring childhood adversity before reading the rest of this article.

Kevin: In the introduction above we have drawn attention to the relationship between stories and power/knowledge, and I thought we might start with this. I’m thinking specifically of how certain issues relating to children and childhood are framed and publicly narrated. An example of what I have in mind is Charlie’s story, which is a video resource produced by the Begin Before Birth Foundation. This is the story of a young man who has just been released from prison for ‘looting’ during unspecified ‘riots’, and his story is narrated from present to past, thereby tracking his ‘aggressive behaviour’ to in-utero experiences attributed to ‘maternal stress’. Designed to coach the public in the science informing TBOAR, Charlie’s story frames a simple yet powerful message: ‘what happens in the womb can last a lifetime’. It is as though this young man’s life has been programmed by his mother’s experiences during pregnancy, which begs the question of what can and ought to be done to prevent the developmental trajectory of vulnerable children from being ‘derailed’ (see Shonkoff et al. Citation2011, pp. 25–27). Intended to promote supportive interventions with a view to engineering better/positive ‘outcomes’ for children coping with adversity, it’s not difficult to imagine this type of explanatory framework having the effect of focusing policy interventions on individual behaviour at the expense of addressing structural inequalities; indeed the video closes with a question that invites this type of interpretation of the science: ‘could better care of pregnant women be a new way of preventing crime?’

Charlie’s story is a specific type of fiction, or more specifically a normative fiction assembled from a body of empirical evidence derived from scientific research, which is given quasi-biographical form as ‘Charlie’. I think this touches on the important issue of context, and the sorts of problems that can emerge as normative fictions such as TBOAR, which are underwritten by the epistemic authority of science, float free of context and acquire the properties of unquestionable truth. I’m curious about how Charlie’s story compares to the initial phase of Boys in the Making, and in particular the first of the boys created by the young men engaging in the programme, Stevie. It seems to me that there are certain commonalities, but also important differences. Charlie and Stevie are both composite characters for example, assembled from lived experience, yet neither story maps onto the biography of any particular individual. In addition, the way these two characters are scripted points to an important contrast between the story narrated by TBOAR (which is the backdrop to Charlie’s story) and the story that the creators of Stevie express through the poem they authored collectively. In some respects similar to Charlie, Stevie narrates a story that spans infancy to early adulthood, and it is the story of a boy becoming a man in a social setting where drugs and crime are part of the prevailing opportunity structure. This appears to be etched into the experience of the young men who created Stevie, and I’d like to put it to you that the story they tell approximates the ancient practice of parrhesia. This is a type of speech situation where ‘truth’ is at stake, and where the parrhesiastes, or the one who speaks candidly and without recourse to the techniques of rhetoric, takes a certain risk (see Foucault Citation2011). I’m going to suggest however that we steer parrhesia away from Foucault’s focus on truth-telling, thereby using this to frame a specific field of power/knowledge. In other words, at stake is not a true/false dichotomy so much as distinct forms of story-telling. TBOAR is anchored in the authority of science, while Boys in the Making is a performative approach to story-telling that exhibits the potential to call that authority into question. It takes a certain courage to produce and narrate a story like Stevie – to tell it as it is, as one experiences it and knows it to be. If this is a fiction, then I don’t read it as a normative fiction. Can you fill in the background to what I’ve outlined and share your thoughts on how Stevie might offer a critical perspective on TBOAR?

Fiona: Starting our conversation with a focus on stories is very appropriate and serves as a useful line of approach to the methodology of Boys in the Making and Stevie. The story of Stevie was created by a group of young men through a long-term process with an artist (myself) and two youth workers from RYP, and ongoing support from the manager of the organisation. The process was centred on a weekly private conversational space, minded carefully by the youth workers who had previously built a strong relationship with the group, subsequently creating the conditions for engagement for the young men in this process.

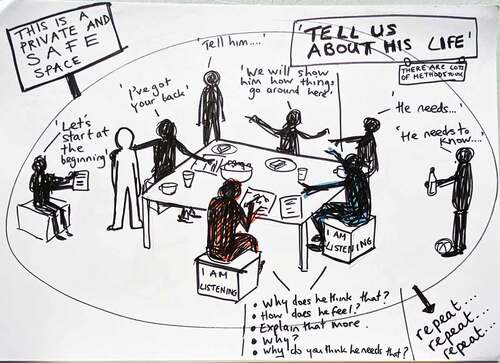

As a team leading the process, the artists and youth workers were consciously attuned to the importance of listening, establishing an enquiring tone, and avoiding any challenging or censoring of the conversation (). The act and demonstration of listening is a central feature of my practice as an artist, which can be seen in this process. Each week, leaving the conversational session, with pages of verbatim notes, my act of listening would translate into a set of drawings and collated texts that would then be shared back with the group at the following session, to demonstrate my listening and to enquire if I had heard correctly. Meanwhile, the youth workers would be engaging in outreach in the local area and connecting with members of the group between sessions, further advancing the conversations. As we all re-engaged each week, and worked with the collated material as a group, this would in turn lead to further deeper conversation, with new enquiries and directions, and importantly, a co-editing of the existing text, and the development of more writing as the story grew and changed through the process. After months of this process, which was not time-bound, the group arrived at an agreed text – a poem which was informed by all those present, and captured Stevie’s existence in that particular moment in time. The approach here fully recognises the intersubjective nature of story-telling (Jackson Citation2002) and its temporality (Lather Citation2009), which seems as odds with the nature of story-telling used to create Charlie.

Through the process of creating Stevie’s story, the young men who created him, mapped out a particular trajectory for the boy, which they felt would serve his needs.Footnote6 Sometime later, when finally presenting Stevie publicly, the young men wrote a speech about the making of Stevie in which they state that the ‘the boys that we know can relate to Stevie’s life … ’, emphasizing the social reality that underpinned their creation and decision-making. But they also went on to say that ‘we are only 18 and 19 so we don’t know if the end of Stevie is a happy ending – a solution or a downfall. It’s probably a fantasy, unless he’s smart, but some people do this as a reality’, ultimately telling the public to decide for themselves. I think this statement beautifully acknowledges the intersection of the external forces shaping Stevie’s life and his own agency as a young man, and the young men’s own agency and intelligence as his creators, trying to do their best for him, against an array of identified structures that are influencing him.

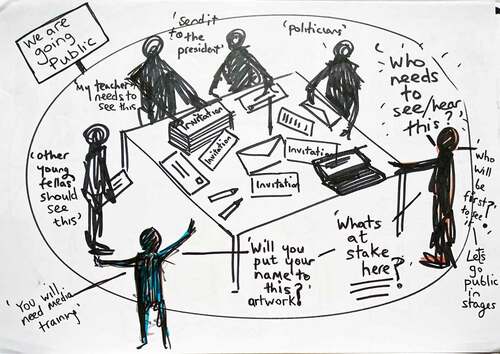

I agree with you, that the process of sharing this story is akin to a parrhesiastic speech act. You mention the courage needed to engage in acts of parrhesia. I think this is really important, and of course parrhesiastic acts always take place in public, with a defining characteristic of parrhesia linked to the public nature of the moment of speaking candidly from experience and with sincerity, thereby confronting the powers that influence and shape the prevailing social reality. In reflecting upon the process used to create Stevie (which now forms the Boys in the Making methodology), the slow and carefully considered transition between a private and public phase was identified as extremely important. The first phase of this methodological approach involves weekly enclosed conversations which build the character’s life. This process must operate in a safe space, where boys and young men can speak frankly, where judgment is suspended, to fully explore how it is that the character interacts with his world, how he shapes it, how it shapes him, and what needs emerge for him as he grows up. It was only when Stevie’s story emerged from this private conversational space, that the young men, youth workers and artist engaged in the conversation about the possibility of this story being told publicly, which would move the process into a second phase. Many meetings took place between all involved, and with the manager and further staff in RYP, to really consider what was at stake in this transition from private to public (see ), what publics needed to be exposed to the work, what other forms the story could take, who was willing to put their name to it, and what processes would the group need to engage in to be present in public alongside this work.

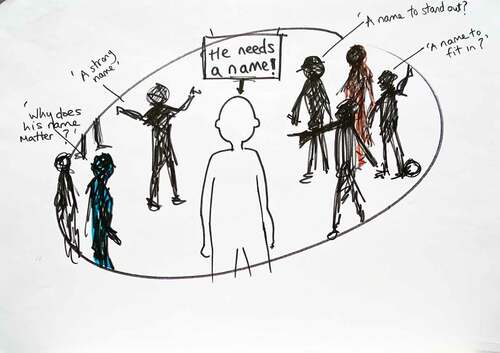

Figure 3. Boys in the Making methodology phase 1. Fiona Whelan and Rialto Youth Project. Drawing by Fiona Whelan.

One central feature of parrhesia is that it ‘opens up risk’ (Foucault Citation2011, p. 63). I think the methodology of Boys in the Making walks this line carefully, which is something I’d be happy to discuss with you in more detail. There is an element of risk attached to engaging in the type of critical exploration of one’s formation that occupies the private encounters of phase one of the process, in that it’s unsettling in and of itself as a group educational experience. However, the movement to the public domain in phase two brings the type of risk associated with parrhesia, both for the young men and for the youth project who show great courage in their willingness to make this transition.Footnote7 As different publics are presented with the characters’ stories and by association might feel challenged, implicated or exposed, there is a level of risk for a character’s makers, such as a risk of judgment, condemnation, alienation or harm. While this type of risk is unavoidable for a parrhesiast speaking in a situation characterised by power asymmetries, what was important in the Stevie process is that this risk was pre-empted and considered through a youth work analysis, so that the boys and young men who have created the character’s story, do not experience any unnecessary risk. This care could see this type of performative story-telling framed as both parrhesiastic, and counter-parrhesiastic as it relates to risk (see Whelan Citation2019). Take Stevie’s daily life as portrayed in the poem and animation that tells his story () – it is already full of risk, and this reflects the lives of countless young men across Ireland and beyond, who engage in drug dealing, or operate on the fringes of it, or live their lives seeking to avoid it. So the youth work process comes to the fore as this transition of the character’s story to public space is negotiated, to ensure a careful and considered movement.

Figure 4. Boys in the Making methodology phase 1. Fiona Whelan & Rialto Youth Project. Drawing by Fiona Whelan.

Figure 5. Boys in the Making methodology phase 2. Fiona Whelan & Rialto Youth Project. Drawing by Fiona Whelan.

Furthermore, the transition to public is slow and takes place in stages – the first-chosen public for Stevie was the local community who received a copy of the poem to their homes via the postal-service, later gathering for a preview of the animation. Only after an assessment of the response to the piece locally, was a wider public preview organised, which was also carefully mediated, before the animation was shown in a film festival. Eventually it may arrive online for general public watching. These phases are so important to ensure care in the risk-taking involved. The time given to this transition from private to public also promotes the sense of movement, that Stevie’s story, much like that of his makers, is in flux, and each encounter offers new insights through responses from different publics, which in turn influences the group and has the potential to instigate a further phase of work. In short, Stevie unlike Charlie is not fixed, he can be returned to by the group at any time. The open-ended nature of the programme and its situatedness in a local youth project which is a constant presence and resource for young people, means that the process can be returned to at a later date and new experiences developed for Stevie at any time. This open-endedness is indicative of how the agency of the young people who created Stevie is facilitated by the programme. The staging of his fictional life born into a specific world through a group process, creates the potential for conversations to move between the socially scripted reality the group perceive for the boy and the potential to be found in the imaginary space of creating new worlds and new realities.

Kevin: When you use the word ‘potential’, linking this to imaginable worlds and new realities, I feel you are moving into a space of thought and practice that spans ethics and politics, and which harbours normative considerations. I’d like to open this out a bit by bringing us back to the central message communicated by TBOAR. I’ve mentioned one version in the BBBF claim that ‘what happens in the womb can last a lifetime’. Another is that ‘the first three years last forever’, which is anchored in the claim that experience ‘gets under the skin’ during the early years and becomes ‘biologically embedded’ (see Essex et al. Citation2013, p. 58, Meaney Citation2010, p. 56). Regardless of how the message is framed, it summons’ the need for action, whether preventive or remedial. More specifically, TBOAR situates the deleterious effects of ‘adversity’ against the benefits of ‘resilience’, and what shapes the relation between one and the other is identified as ‘stress’. According to TBOAR, there are three types of stress – ‘positive’, ‘tolerable’ and ‘toxic’.Footnote8 While stress can apparently be conducive to learning and healthy development, at the toxic side of the spectrum is the kind of stress that figures in Charlie’s story, and the central claim here is that this can ‘disrupt the development of brain architecture’ and ‘increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment’.Footnote9 There’s an additional aspect to this which is worth drawing attention to, and it has a bearing on the theme of stories and what I referred to earlier as normative fictions. ‘Brain architecture’ and ‘toxic stress’ are both metaphors, designed as such with a view to fashioning a ‘core story’ of early child development which is tasked with communicating the science to a non-specialist public and to policy-makers (see Shonkoff et al. Citation2011, CDCHU Citation2014).

So we have this interlacing of facts and norms within the frame of a story which is replete with metaphors, and which is disseminated with the express purpose of shaping public opinion and influencing public policy. Let’s focus on the normativity at work here. According to TBOAR, the effects of toxic stress can be ascertained by studying its molecular, cellular, psychological, and behavioural effects, for example through the use of electroencephalogram technology (EEG) to produce a ‘readout of neurobiological “embedding” of early life stress’.Footnote10 The science is more than science however, as it looks beyond the biology of adversity and stress to the normative question of what ought to be done to counter harmful effects. It is right here, at the point where facts meet norms that the notion of ‘resilience’ appears. Importantly, and notwithstanding different ways of defining or interpreting resilience, TBOAR associates it with supportive relationships that are said to ‘buffer’ adverse childhood experiences.Footnote11 Without wishing to dispute the inference that children ought to be supported and protected by their primary care-givers, there is nevertheless cause for concern to the extent that ‘resilience’ remains a way of coping with adversity without necessarily doing anything to counter or mitigate its underlying causes/sources. This is among the criticisms of the science of childhood adversity, specifically as this relates to the CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, conducted between 1995–1997, which codifies adversity by assigning an ‘ACE score’ to individual children as a predictor of ‘negative outcomes’. As argued by Alex Winninghoff (Citation2020), the ACE approach is widely perceived to communicate the message that ‘something happened to you’, as opposed to ‘something is wrong with you’. In practice however it can convey the message ‘something is wrong with you because something happened to you’. This is one of the ways that TBOAR risks replicating a behavioural approach to social problems (see Edwards et al. Citation2017). If we take the time to drill down into how the word ‘adversity’ is used within the frame of TBOAR, it becomes apparent that it covers a multitude, and could well serve as an entry point into issues concerning inequality, discrimination, exploitation, exclusion, racism and injustice. In short, when ‘adversity’ is understood in biological terms, and when the science authorises a normative response in the form of ‘resilience’, then there is a danger of deeply political issues becoming depoliticised.

In what you’ve outlined concerning the methodology that has evolved through the process of Boys in the Making, you emphasise the care taken to mitigate the risk of judgment. How do you and your co-collaborators tackle the normative implications of Stevie’s story, and not just Stevie’s story, but also the many other quasi-fictional boys who now populate the landscape of the Boys in the Making programme?

Fiona: Perhaps I can begin to address this by explaining some key features of the Boys in the Making programme, which was developed from the methodology used to create Stevie. The process takes place with a group of boys or young men who are invited to create a boy character through a dialogical process. This process is always led by a youth worker/educator who has a strong relationship to the group, and an artist. This team places an emphasis on enquiring and listening. The only facts about the boy character that are predetermined are that he was born a boy and he is from the same place as the group harnessing specific contextual knowledge and exploring the intersection of social context and forms of masculinity. The combined effect of all these features is to place central importance on the knowledge of the group who are creating him, who draw on their lived experiences and observations of life in their own social context to shape the proposed life journey of the character. What emerges is a story of a fictitious boy who is born into a real world, and embodies much of the knowledge of his makers.Footnote12

The fictional nature of the boy is important as it promotes a sense of anonymity in the process – the boy is nobody specifically but is a part of everybody in the group. Importantly, he can embody a number of contrasting experiences and views born of the conversational exchange which created him. This process recognises the ongoing, temporal and relational nature of story-telling. Stevie’s story, unlike how those promoting TBOAR may tell a story, is not intended to be fixed or singular but full of complexity and movement. It does not claim to communicate a universal or normative truth, rather an account of one life, being shaped from the vantage point of a group at a given moment in time.

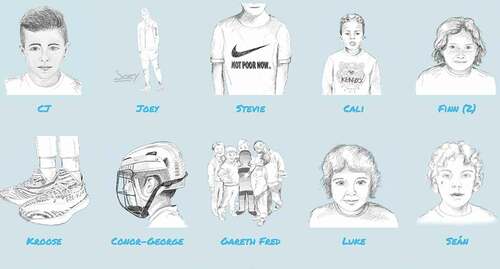

The open-ended and cumulative nature of this Boys in the Making program coupled with the ambition for its scale and reach, further help reduce the normative implications of sharing Stevie’s story. The character’s creation was born of a process rooted in a local youth project, with strong ties to the local communities. This embedded relationship offers a longitudinal potential to Stevie’s life, with future iterations possible, as his creators or others may re-engage in time and adapt and develop the story. Nothing is fixed. Furthermore, alongside Stevie, there have been many other boys created by groups (), including seven boys created by different groups at RYP, opening up many divergent experiences of one place. Currently, there are also an additional four boys being created in other parts of Dublin as part of a new pilot stage of testing the methodology in diverse contexts. From one young man to the next, or one group to the next, different opinions and outlooks emerge. While each story communicates a particular realm of experience, the multiplicity of stories helps to avoid any reduction to a simplistic or singular claim of truth.

Figure 7. Screen shot of What Does He Need? online at https://www.whatdoesheneed.com/boys/.

Importantly, the stories emerging for each character, as with Stevie, communicate the character’s life as he negotiates a complex set of social structures, which have power in his life. While he may show resilience and tactics for survival against perceived adversity, it is important that his story situates him in a context, so each boy’s creators and their publics can see the power relationship between the boy and his world, and the underlying sources of any adversity that he is navigating. In the face of the increasing depoliticisation of inequality and the dominant neoliberal logic which is outcome-driven and founded on evidence-based rationalities (see Kiely and Meade Citation2018), I would advocate for this form of indeterminate and open-ended educational process, committed to exploring and representing systemic power relations. As I also come to understand the normative fictions underpinning the science of TBOAR, and its increasing influence on policy in the form of overly prescriptive and determined responses, I’m inclined to further argue for the importance of the values underpinning the Boys in the Making programme. I believe our commitment to collectively examining lived experiences of power relations with young people in an open-ended process, offers an alternative ethical framework to the contemporary ethics of social inclusion, which has become an often reductive and simplistic antidote to histories of social exclusion (Whelan and Ryan Citation2016), and which does not always take account of the unequal systems one is being included into, and the power relations that govern that inclusion. My position is informed by the politics and values of RYP who have always rejected the term ‘disadvantaged’ in the state’s classification of Rialto, along with any overly prescriptive or reductive remedies to counter it. Instead, they adopt the defiant language of ‘oppression’ and ‘marginalisation’ in recognition of the external forces that shape the lives of young people they engage with, and promote a rigorous youth work practice, underpinned by their own needs-based analysis to determine modes of engagement and supports for young people.

Kevin: I’m sensing an important question beginning to emerge in what you’ve outlined, and to be more precise, it emerges at the power/knowledge interface: what exactly counts as evidence in laying claim to the truth of adverse childhood experiences, and whose views and perspectives count when it comes to narrating that truth? TBOAR communicates through the scientific language of ‘findings’ (see, for example, Shonkoff et al. Citation2021), and I’d like to delve into this way of codifying knowledge by returning to the issue of stress – both maternal stress, which features in Charlie’s story, but also ‘toxic’ stress associated with adverse experiences among so-called ‘disadvantaged’ children.Footnote13 The Michael Meaney Lab at McGill University has been at the cutting edge of research on maternal stress for many years now, using experiments on animals to examine how variations in maternal care regulate stress-reactivity on the part of offspring (see, for example, Meaney Citation2001, Champagne and Meaney Citation2006, Weaver et al. Citation2006). In the thick of this research is the age-old debate on ‘nature v nuture’. Experiments in cross-fostering for example demonstrate a non-genomic behavioural mode of transmission which is explained in terms of ‘environmental regulation’ (Meaney Citation2001, p. 1178; also Caldji et al. Citation2003, Weaver et al. Citation2004). What this boils down to is the claim that stress imposed on the mother as a result of environmental conditions is epigenetically impressed upon her offspring. In evolutionary terms, this is said to be adaptive, because it prepares young mammals for what is to come once they leave what Meaney describes as ‘the sanctity of the burrow’ (Citation2001, p. 1178). This is where the findings start to become significant to researchers interested in adverse childhood experiences, particularly among ‘disadvantaged’ children and families, because non-human mammals that inhabit a particularly threatening environment apparently programme or equip their young with a defensive response to threat or adversity. As this research is incorporated into TBOAR, the anxious young animal raised by a stressed mother morphs into the figure of the disadvantaged child, and normative fictions such as Charlie’s story come into focus, figuring children and young people who are edgy and fearful, on the knife-edge of the fight/flight response (for critical discussion see Richardson Citation2015, Ryan Citation2021). Coupled to the behavioural features of maternal stress are the health implications of children experiencing ‘toxic’ stress. To quote Meaney once more, ‘individuals who show exaggerated HPA [hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal] and sympathetic responses to stress are at increased risk for a variety of disorders, including heart disease, diabetes, anxiety, depression, and drug addiction’ (Meaney Citation2001, p. 1163).

I suggest taking a step back from the primary literature on stress as published in academic journals such as the Annual Review of Neuroscience, Biological Psychiatry, and Nature Neuroscience. This literature presents the central claims of TBOAR with a degree of caution, frequently acknowledging that that there is more work to be done, and that what can be inferred from the evidence remains contingent on further research. In his influential book on The structure of scientific revolutions, Thomas Kuhn notes that this type of ‘mopping up operation’ is a typical feature of what he calls ‘normal science’ (Citation1996, pp. 23–4), but what is worth noting here is how this acknowledged inference and conjecture vanishes once the research findings from TBOAR are repackaged and communicated to a non-specialist public.Footnote14 Otherwise put, as prepared and presented for public consumption, the story of how child development can be ‘derailed’ by adverse experiences and stress becomes a statement of scientifically verified fact, at which point it also arguably occupies a privileged place relative to the experience of inequality, marginality, and exclusion. It seems to me that Boys in the Making is very different in terms of how the knowledge informing the programme is generated, communicated, and folded back into the process as it develops. When it comes to publicly communicating the knowledge emerging from Boys in the Making, you have shared some insights into how this is done from the perspective of the young men who created Stevie. Could you say a bit more about this transition to public spaces – how would you characterise your audience or public, how do you engage that public, and what sort of responses or feedback do you get?

Fiona: These are really important questions. In Boys in the Making, as each character is transitioning to the public phase of the process (phase two), the group and the youth project (or school/community organisation), will consider who they want to hear this story and multiple publics will be identified and targeted. Importantly, the first request of any public is to listen, and in that sense, this approach connects back to the parrhesiastic speech act. The group of boys or young men who have created the boy will share his story through some form of artistic output (such as the Stevie poem and animation), and so the process led by youth workers/educators and artist is to create the conditions for listening to occur. I’m interested in what Susan Bickford describes as ‘political listening’ (Citation1996, p. 2), moving beyond a caring, empathic listening practice to a communicative interaction in which conflict and difference are central, such as that which arises from inequality. Bickford argues that it is precisely this kind of listening to one another that is required in democratic politics, and so to emphasise listening in our invitations to publics ‘is to confront the intersubjective character of politics’ (Citation1996, p. 4).

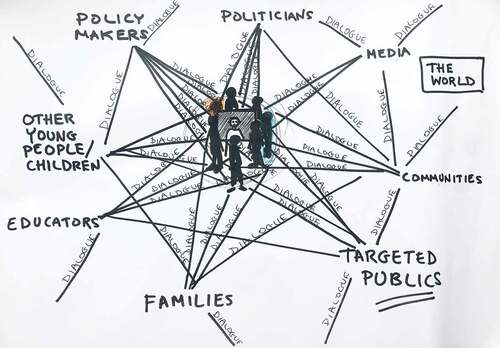

While listening to the content of a character’s story, publics are also confronted by his creators’ reflexivity and their capacity for voice (see Couldry Citation2009), as well as their own power relationship to him. And the boy’s creators are also confronted by the story they have told at this moment, and the publics’ responses to that. Something is unsettled when people speak and listen, which then opens up the possibility for something else to emerge from the interaction. In the case of the unfolding and cumulative process of creating and presenting Stevie to the world (as with all further characters created through the Boys in the Making methodology), it has been important to think about ways to move from phase two of the program, which sees the character’s story presented and listened to publicly, to a third phase where that story can enter into dialog with the world and where other publics can connect and engage with the complex themes and power relations being identified ().

Figure 8. Boys in the Making methodology phase 3, Fiona Whelan & Rialto Youth Project. Drawing by Fiona Whelan.

One such attempt to move into the public dialogue that would characterise the proposed phase three of the process, was led by myself and the manager of RYP, and involved inviting members of the public to write Stevie a letter – an opportunity to speak back to Stevie, encouraging a move beyond an empathic form of listening, to what Back presents as ‘a form of active listening that challenges the listener’s preconceptions and position while at the same time it engages critically with the content of what is being said and heard’ (Citation2007, p. 23). Importantly however, the letters were not to be penned from the subjective perspective of individual members of the public, as we wanted to avoid individualized or overly sentimental responses that personal letter writing might have elicited. Rather each was asked to identify with a person, place or thing in Stevie’s world, as identified in his story (told in the poem/animation), and speak from that position, to amplify the macro-political context in which the boy’s life exists and open up the dialogue about the power relationship between Stevie and the world he lives in. To date, fifty-three letters have been received that were written from multiple perspectives including ‘the flats’ (i.e. the housing complex where Stevie lives), ‘weed’ (marijuana), ‘the police’, ‘Mountjoy prison’ (in Dublin), ‘Nike’ (as a brand of shoe signifying prestige), ‘the bed’ (where Stevie sleeps at night), ‘Spiderman’ (who figures in Stevie’s story), and Stevie’s loyal Jack Russel dog. These letters can hopefully inform a future iteration of the process as the potential of phase three is examined further by those involved. Similarly, during the summer of 2021, myself and RYP staff also developed and tested ideas for another multilayered artistic and pedagogical response to Stevie’s story, which we temporarily framed as School of Stevie. The learning from this experiment also has the potential to seed a longer-term set of ideas in this open-ended and iterative project.

Kevin: Looking towards the future as an open horizon of possibilities seems to be fully in-tune with the methodology of Boys in the Making, which – if I understand it correctly – is guided not by codified rules and procedures but by looser principles of voice, listening, care, and equality. I’m acutely aware of how important the meaning of words is to the practice you’ve been discussing, and also how much time and effort you and your collaborators devote to the ‘grammar’ of the practice, which gives me reason to think that Boys in the Making might be described as artistic research, or if not that, then a mode of research that doesn’t necessarily conform to the logic of ‘research’ as this operates in the context of the biological and biomedical sciences.

Fiona: I think this a really interesting direction to take the conversation, as it connects to the central question of power and more specifically the authority of research. While I understand TBOAR to be a scientific paradigm that advocates for specific policy-responses to childhood adversity, and does this through a mode of communication that seeks to connect scientific research directly to policy-responses, I see Boys in the Making as a different type of relation. Its values and methodological approach could be described as a democratic form of public engagement, nurtured through creative modes of exchange that are polyvocal and dialogical in form, and contingent on the relational process that underpins the process, which is deeply rooted in youth work values, positioning young people centrally. Simultaneously, the boy-making process can also be seen as a collective research action, where knowledge is generated through the collective relational process. Furthermore, research is not generated for the purpose of extraction and external use, instead the research folds back into the group and informs the ongoing process. Over time, the destination of the research can shift to a series of identified and targeted publics, but this shift is decided upon by the group of young people, youth workers/educators and artist working collaboratively at an appropriate moment for the process. It is also worth remembering that the Boys in the Making programme is being developed in the context of a wider cross-sectoral and trans-disciplinary project called What Does He Need? and this framework means that the accumulating body of research has potential to further manifest in public through additional artistic and pedagogical responses, which in turn create new layers of public engagement for the wider project.Footnote15

Kevin: When you refer to your practice as a form of democratic engagement, I’m reminded again of the normative issues and concerns that arise within the frame of TBOAR and Boys in the Making. Once we open out the question of what children need – what we as adults think they need, or what they as children say they need – then everyone who is party to that conversation, adults and children alike, are drawn into one or another type of power relation. In a previous dialogue where we discussed your earlier work before What Does He Need? and Boys in the Making, I put it to you that there are at least two forms of relational power operating simultaneously within and through the work you do with RYP, one that articulates inequalities between those who exercise power and those who are subject to power, and the other whereby power is co-produced through collaboration (see Whelan and Ryan Citation2016). How does this play out in the context of Boys in the Making?

Fiona: Attending to power relations within the collaborative process has always been a primary concern of mine while exploring and responding to other systemic power relations in the lives of young people. After a number of years immersed as an artist in RYP (I’m taking us back to 2008 here), the symbol of a triangle () emerged as a means of visualising the triangulation of subject positions that correspond to the field of community-based, collaborative arts practice. On one side of this triangular relation is the artist, with a second side representing the professionals attached to a community organisation, and a third the users of the organisation, who are often classified in some way by their attachment to it (such as ‘client’ or ‘service user’). This set of relationships is typically hierarchical, with the artist and organisation’s staff members developing structures that participants, in this case youth, would be invited to avail of. The image of the triangle became a useful symbol to communicate (internally and externally) the distinct subject identities that underpinned the collaborative process. Subject positions would not be abandoned, risking a kind of neutralised equality that would mask the cultural hierarchy we were working to overcome. Instead, holding and working through the complexities attached to each of our points on the triangle was important, while laying the triangle flat, as an ambition to be non-hierarchical from the outset.

Figure 9. Policing Dialogues (2011), The LAB gallery, Dublin, What’s The Story? Collective. Photo by Michael Durand.

What emerged as centrally important in this visualisation of the triangulated relationship – which is still evident in the Boys in the Making process – is the contingency of the relations between artist, youth workers and young people. As one young person clearly stated many years ago, ‘Without us, you wouldn’t have a job’ (Anon, in Whelan Citation2014, p. 76). Of central importance in this statement is the recognition of young people’s agency, and an awareness on their part that by combining their individual agency within the context of the practice or specific programme, they are creating the power to act in concert (which may also include the decision to dis-engage from the process/programme). This process of mutual empowerment is also how stories of power become the power of story as the work transitions to public spaces.

Over the course of many years, the triangulated relational structure at the core of the collaborative process has generated a process of constant negotiation with regard to subjectivity, power relations and ethical dilemmas far more complex than the original three subject positions indicated above. The metaphor of the triangle was also used to visualise further sets of power relations in young people’s lives and became a methodological device that was operationalised as a space for agonistic dialogue.Footnote16 Over time, as multiple processes have been developed with young people, I’ve become more attentive to the fluctuating nature of power and the multi-layered contingency of the power relations of a group working collaboratively. Privileging the processual and the emergent, while staying attentive to the presence of power relations, strives to ensure that the Boys in the Making programme retains the capacity to generate unanticipated insights and learning that can feed back into the process as it moves into the future.

Kevin: The trialogical process you describe suggests a web of power relations operating through and within the space of collaboration. Indeed, this might be seen to mirror social life in the more general sense given that social life is invariably scripted to a greater or lesser extent, and with this in mind, I’m going to flip the biological framing of adversity (TBOAR) into a sociological version of the story. Otherwise put, the power relations that shape our formative years during childhood simultaneously provide us with agency while also conditioning what we might become in the future. In the discipline of sociology this is the classic ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ issue, or what Anthony Giddens preferred to theorise as a duality whereby social structures are at once the medium and outcome of action, both enabling and constraining the agency of social actors (Citation1984, pp. 25–28; see also Haugaard Citation2003). This offers a critical bearing on TBOAR to the extent that it maps onto ‘adversity’ (structural forces and constraints) and ‘resilience’ (as an agentic quality that is said to ‘buffer’ the damage otherwise caused by adversity). Here there is a notable contrast between the process you describe, which operates through a conscious awareness of power relations within the space of collaboration, and TBOAR, whereby the science reaches for universal normative validity, and does so by speaking for and on behalf of children living with adversity. In this way, scientific expertise assumes a position of authority that suggests a hierarchical relation between those who (claim to) know and those who are known. The upshot of this is that the structure/agency axis of TBOAR becomes a prescriptive and unidirectional mode of communication. In short, the agency of children at risk of negative ‘outcomes’ due to ‘adversity’ is to be acted upon in accordance with the science, and this with a view to engineering ‘positive’ outcomes. In this positing of outcomes, where ‘positive’ serves as short-hand for normatively desirable behaviours, dispositions and bodily functions, we come full-circle to the scripting of social life, except that now we encounter this not as an axiom of sociology, but as a biopolitical endeavour. The difference is crucial to understanding what is at stake here. Under the cover of scientific Truth-writ-large, TBOAR is a biopolitical project that aims to act upon life in the form of ‘childhood’. This is in fact an old story (see Ryan Citation2020), now clothed in the novel garb of neuroscience and epigenetics, and conveyed through catchy metaphors such as ‘toxic stress’ and ‘brain architecture’. While I have no doubt that the advocates of TBOAR are acting with good intentions, I feel it is imperative to interrogate the telos of this normative science. If agency is a matter of resilience, then it seems ‘agency’ stops short of tackling the causes of adversity, in which case the prevailing social structure becomes a situation to be endured rather than transformed.

By way of concluding, I’d like to return to what we referred to in the introduction as a relation between programme and paradigm in this particular field of power/knowledge, and more specifically, the relation between a universalising Truth scripted and authorised by science, and situated stories that emerge through sensate experience – a relation that can be explicated from Foucault by figuring it as a ‘parrhesiastic game’ (Citation2011, pp. 12–13). If it takes audacity to speak candidly and with sincerity about living with and through adversity, it also takes a type of courage to listen and to acknowledge that the truth of adversity exceeds the knowledge produced by the biological and biomedical sciences. At this point in time, this parrhesiastic game is hardly a meeting of equals, but what if collaborative arts, community-based youth work, and science were to converse as peers? To take it one step further – if this affords a way of really getting to grips with the causes and consequences of childhood adversity, then what if that conversation was to include the voices of children?

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the two anonymous referees for their thoughtful comments, constructive criticisms and suggestions. We also wish to acknowledge the following people and supports:

Ciaran Smyth (researcher, Vagabond Reviews) for designing and facilitating the process to capture the know- how of the Boys in the Making programme, which led to the production of the methdological overview and the programme name.

Dannielle McKenna (Rialto Youth Project), Michael Byrne (Rialto Youth Project), Jim Lawlor (formerly of Rialto Youth Project/independent advisor to What Does He Need?) - core youth work collaborators of Fiona Whelan's, who collectively worked with research partner Ciaran Smyth towards the production of the Boys in the Making methodological overview.

The Arts Council, National Youth Council of Ireland, Irish Museum of Modern Art and Rialto Youth Project for financial and in kind support towards the development of the Boys in the Making programme.

Create (the national development agency for collaborative arts) through a Dublin City Arts Office Revenue Grant, and the School of Applied Social Studies at University College Cork who supported the Boys in the Making methodology workshop in November 2022.

The young men who created Stevie with such honesty and courage.

All the boys, young men, educators, artists and youth workers throughout Dublin, currently engaged in the Boys in the Making programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kevin Ryan

Kevin Ryan is a lecturer at the National University of Ireland, Galway. His research explores freedom as a practice which is shaped by power relations, with a particular focus on childhood as the locus of biosocial power. Kevin's most recent monograph is Refiguring childhood: Encounters with biosocial power (MUP 2021).

Fiona Whelan

Fiona Whelan is a Dublin-based artist, writer and lecturer at the National College of Art and Design (NCAD). Her arts practice is committed to exploring and responding to systemic power relations and inequalities, through long-term collaborations with diverse individuals, groups and organisations.

Notes

1. See https://whatdoesheneed.com

3 In what follows we will be using ‘child’, ‘children’, ‘childhood’, ‘youth’, and ‘young people’ in accordance with the legal conception of childhood as the age of minority.

4 As part of the What Does He Need? project, the development of the Boys in the Making programme was supported via an invited residency for Fiona Whelan at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and through funding from the National Youth Council of Ireland: Artist in Youth Work Residency, an Arts Council Arts Participation Project Award, and Rialto Youth Project core funding. As a scientific paradigm, TBOAR is funded in a more varied way depending on the researcher and/or research project in question. For example, the Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University lists the Buffet Early Childhood Fund and the JPB Foundation as ‘Major Investors $10 million + (Cumulative Giving)’.

5 Charlie’s story was produced by the Begin Before Birth Foundation (BBBF), which is initiative by researchers at Imperial College London. The video is archived on YouTube along with two other video resources, one on epigenetics and another that focuses the core message that ‘what happens in the womb can last a lifetime’. See https://www.youtube.com/user/Beginbeforebirth.

7 Since the mid-1980s, Rialto Youth Project has built a strong capacity for arts-based work committed to the exploration and representation of social issues. This includes Policing Dialogues (2007-11) and Natural History of Hope (2012-16) which were long-term collaborative project developed with Fiona Whelan, and What Does He Need? (2018+) with Fiona Whelan and Brokentalkers. See http://rialtoyouthproject.net/critical-social-education-arts-based/

8 See the online resources available at the Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

9 Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/ [accessed 21 December 2021].

10 See the JPB Research Network on Toxic Stress. Details available here: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/innovation-application/frontiers-of-innovation/pediatric-innovation-initiative/jpb-research-network/ [accessed 21 December 2021].

11 See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html.

12 In 2021 Ciaran Smyth (Vagabond Reviews) was engaged as research partner to design a collaborative process to capture the know-how around the strand of the What Does He Need? project engaging with children and young people in the construction of an imaginary, place-based boy. He worked with Dannielle McKenna, Michael Byrne and Jim Lawlor (of Rialto Youth Project) and artist Fiona Whelan in a process of recursive conversational inquiry and (re)drawings to produce the methodological overview, and proposed Boys in the Making as a nomenclature that captured three dimensions: (a) the construction of an imaginary, place-based boy (b) the boys and young men engaging in that shared process of construction and (c) the mediating social, cultural, political and economic processes that govern the construction of masculinity.

13 For a critique of disadvantage as a way of figuring inequality see (Two Fuse Citation2018).

14 On how the science was crafted into a ‘core story’ designed to communicate to a non-specialist public, see (Shonkoff et al. Citation2011).

16 I’m referring here to the Policing Dialogues project (2007-11), a collaborative project led by a collective of young people, youth workers and artist exploring power and policing. For further discussion see Whelan (Citation2014, Citation2019).

References

- Back, L., 2007. The art of listening. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bickford, S., 1996. The dissonance of democracy: listening, conflict and citizenship. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Boyce, T.W., Sokolowski, M.B., and Robinson, G.E., 2012. Toward a new biology of social adversity. PNAS, 109 (2), 17143–17148. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121264109

- Caldji, C., Diorio, J., and Meaney, M.J., 2003. Variations in maternal care alter GABAA receptor subunit expression in brain regions associated with fear. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28 (11), 1950–1959. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300237

- CDCHU, 2014. A decade of science informing policy: the story of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Online at: http://www.developingchild.net Accessed 4 November 2021

- Champagne, F.A. and Meaney, M.J., 2006. Stress during gestation alters postpartum maternal care and the development of the offspring in a rodent model. Biological Psychiatry, 59 (12), 1227–1235. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.016

- Couldry, N., 2009. Rethinking the politics of voice. Continuum, 23 (4), 579–582. doi:10.1080/10304310903026594

- Edwards, R., et al., 2017. The problem with aces. submission to the house of commons science and technology select committee inquiry into the evidence-base for early years intervention (EY10039). Available at: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/parentingculturestudies/ 16 October 2020

- Essex, M.J., et al., 2013. Epigenetic vestiges of early developmental adversity: childhood stress exposure and DNA methylation in adolescence. Child Development, 84 (1), 58–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01641.x

- Foucault, M., 1980. Power/knowledge: selected interviews & other writings 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M., 2011. The courage of truth. lectures at the collège de France 1983-1984. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Giddens, A., 1984. The constitution of society. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Haugaard, M., 2003. Reflections on seven ways of creating power. European Journal of Social Theory, 6 (1), 87–113. doi:10.1177/1368431003006001562

- Jackson, M., 2002. The politics of storytelling: Violence, transgression and intersubjectivity. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Kiely, E. and Meade, R., 2018. Contemporary Irish youth work policy and practice: a governmental analysis. Child & Youth Services, 39 (1), 17–42. doi:10.1080/0145935X.2018.1426453

- Kuhn, T., 1996. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lather, P., 2009. Against empathy, voice and authenticity. In: A. Y Jackson and L.A Mazzei, eds. Voice in qualitative inquiry. London: Routledge, 17–26

- Meaney, M.J., 2001. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24 (1), 1161–1192. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161

- Meaney, M.J., 2010. Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene x environment interactions. Child Development, 81 (1), 41–79.

- Richardson, S.S., 2015. Maternal bodies in the postgenomic order: gender and the explanatory landscape of epigenetics. In: S.S. Richardson and H. Stevens, eds. Postgenomics: perspectives on biology after the genome. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 210–231.

- Ryan, K., 2020. Refiguring childhood: encounters with biosocial power. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Ryan, K., 2021. Programming the future: epigenetics, normative fictions, and maternal bodies. P.O.I. – Rivista di indagine filosofica e di nuove pratiche della conoscenza, 8 (1), 80–105: http://poireview.com/en/homepage-2/ Retrieved 12 January 2022

- Shonkoff, J.P., Bales, S., and N, 2011. Science does not speak for itself: translating development research for the public and policymakers. Child Development, 82 (1), 17–32. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01538.x

- Shonkoff, J.P., Slopen, N., and Williams, D.R., 2021. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42 (1), 115–134. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-101940

- Two Fuse, 2018. Freedom? Cork: Cork University Press.

- Weaver, I.C.G., et al., 2004. Epigenetic programming by maternal behaviour. Nature Neuroscience, 7 (8), 847–854. doi:10.1038/nn1276

- Weaver, I.C.G., Meaney, M.J., and Szyf, M., 2006. Maternal care effects on the hippocampal transcriptome and anxiety-mediated behaviors in the offspring that are reversible in adulthood. PNAS, 103 (9), 3480–3485. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507526103

- Whelan, F., 2014. TEN: territory, encounter & negotiation. A critical memoir by a socially engaged artist. ncad.academia.edu/fionawhelan Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Whelan, F., 2019. Reconfiguring systemic power relations: A collaborative practice-based exploration of inequality with young people and adults in Dublin. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin: Technological University Dublin.

- Whelan, F. and Ryan, K., 2016. Beating the bounds of socially-engaged art? A transdisciplinary dialogue on a collaborative art project with youth in Dublin, Ireland. FIELD: A Journal of Socially-Engaged Art Criticism, 4 (Spring). Online at http://field-journal.com/issue-4/beating-the-bounds-of-socially-engaged-art-a-transdisciplinary-dialogue-on-a-collaborative-art-project-with-youth-in-dublin-ireland Retrieved 5 December 2021

- Winninghoff, A., 2020. Trauma by numbers: warnings against the use of ACE scores in trauma-informed schools. Bank Street Occasional Paper Series, 2020 (43), 33–43. Available at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2020/iss43/4 Accessed 16 February 2022