ABSTRACT

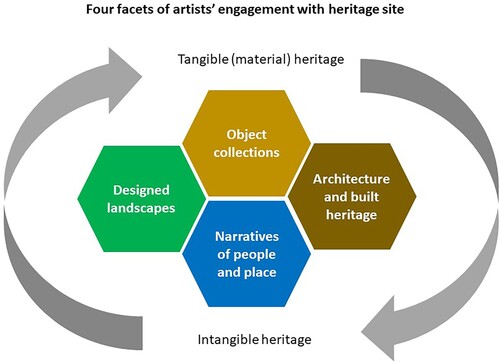

Since the 1990s, contemporary art projects have appeared in an increasing variety of heritage sites across the UK, from grand palaces and country houses, to industrial museums and historic waterways. In England, the country's two leading national heritage organizations, The National Trust and English Heritage, have vigorously engaged with contemporary art and artists, generating exhibitions and temporary commissions that significantly extend traditional approaches to heritage presentation. Drawing on interviews with art curators and program managers working in this field and grounded analysis of project documentation and grey literature, this article maps the territory of contemporary artists’ recent engagement with the heritage sector and the institutional claims made for the benefits of this new type of heritage practice. Artistic engagement focuses on four significant aspects of heritage sites: object collections; built architecture; designed landscapes; and intangible narratives of people and place. Disparate and sometimes conflicting claims are made for the value of this activity, ranging from audience development and diversification, increased visitor numbers, heritage site reanimation, to the generation of opportunities for artists’ creative and professional development. Despite this growth and the strong level of advocacy advanced for contemporary art in heritage practice, a more critical understanding of this field is required.

Introduction

Visitors to Belsay Hall in Northumberland during the summer of 2018 had the opportunity to experience a haunting sound installation The Yellow Wallpaper by Turner Prize winning artist, Susan Philipsz. Combining the intangible heritage of border ballads with the physical fabric of the English Heritage site, Philipsz's voice emanated from fireplaces in the otherwise empty spaces of the upstairs bedrooms. Drawing inspiration from Charlotte Perkins Gilman's short story of the same name and Edgar Allan Poe's Murder in the Rue Morgue, visitors were invited to imagine the conversations that might have once filled the echoing spaces of the Middleton family's home; which itself incorporated a fourteenth Century fortified tower designed to protect the family from the travails that featured in many of the border ballads.

Philipsz's work was the latest instalment in a lengthy history of contemporary art being commissioned for Belsay, which started with Living at Belsay in 1996 and has involved artists such as Ron Mueck, Hew Locke, and Mariele Neudecker, fashion designers including Stella McCartney and Viktor and Rolf, and collaborations for Picture House (2007) between Boudica and Mike Figgis, and Tilda Swinton and John Byrne. Mostly presented in group shows, Belsay has been a pioneering test bed for the evolving field of contemporary artists responding to heritage sites. This burgeoning field of practice has its roots in institutional critique in museums, and there is now a proliferation of projects and programs across a range of heritage sites and settings, from grand palaces and country houses, to industrial museums and historic waterways.

Despite this, and the often “blue chip” status of many involved, this is a neglected field critically and academically (similar to the cognate areas of public art and temporary site-specific practice), and what literature there is tends to concentrate on museological practice (e.g., McShine Citation1999; Putnam Citation2001; Chubb Citation2007; Cass Citation2015), or individual case studies (see Cass, Powell, and Park Citation2020). This lack of critical currency might partly be due to the emphasis on interpretation and visitor engagement by two of the key commissioners of this type of work, the UK's main heritage organizations English Heritage and the National Trust. Motivation of all involved has been questioned, as Tom Lubbock commented in The Guardian review of Ha ha in 1993:

In general, I feel that the fame should now be up altogether with ‘responding to sites’, because it's extremely rare for artists to have any vital response to the sites allotted to them. (They suddenly discover an interest in gardens, or naval hospitals, or the carpet industry.) Something can usually be cooked up, and it looks good on the cv. But it simply becomes a way of unnecessarily generating art – with some added tincture of worldly relevance – like a school project, or an answer to the old question ‘What shall I draw Mum?’ It gives the not very gifted something to fall back on (a bad plan). And it's no big improvement on the old outdoor-sculpture practice of dotting already existing statues around a landscape.

Drawing on grounded analysis and interviews with key actors this article seeks to map the evolution of what we argue is a distinct strand of practice – contemporary art in heritage – and in so doing draw out its characteristics and complexities. Alongside charting the expansion of the field, into what might be described as a new commissioning industry, and identifying the strategic and artistic drivers for the development of the practice, we argue that these might be the very things that have undermined the critical attention afforded to this activity.

Methods and Data Sample

This research was undertaken as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council project Mapping Contemporary Art in the Heritage Experience (MCAHE: https://research.ncl.ac.uk/mcahe/, 2017–2019) which aimed to examine the development of contemporary art in heritage in the UK from the perspective of artists, commissioners, and audiences, and involved creating a series of new artwork commissions in partnership with heritage partners including the National Trust, English Heritage, and the Churches Conservation Trust. Within this, we were particularly interested in exploring how the discourse of contemporary art in heritage practice has evolved over the last 30+ years, from early projects in the 1990s, and how these projects and activities have been variously described (by commissioning bodies, curators, heritage partners, and the media, for example) in terms of their perceived purposes, benefits, impacts, and effects. The research had two key phases: document and archive analysis, using a grounded approach, and qualitative semi-structured interviews with key actors in the field.

This focus was on practice in the UK for two principal reasons: the UK has been a prime generator of this kind of work, undoubtedly partly due to its well-established heritage and arts sectors; and, as this was the first attempt to do such a study, it was decided that forming a practical foundation from which future comparator studies could be undertaken was most realistic. The starting point was a database created by the sector support organization Arts&Heritage (A&H; a partner on MCAHE) which contained information on 333 projects based in museums and heritage sites that were realized between 1994 and 2014. This was an audit covering Scotland, England, and Wales undertaken by A&H in 2013 for Arts Council England (ACE). This database was then developed and refined further by the MCAHE team through desk-based research into published literature, sector-based newsletters, reports, documentation and web-based research.

This material was then augmented with data gathered through an online Open Call to professionals working in the arts and heritage sector (March–June 2018) promoted through the MCAHE website and social media, via project partners including the Contemporary Visual Arts Network, sector newsletters and fora, online mailbases and advertisement with A-N The Artists Information Company. The call generated 86 responses from 56 artists and curators. Respondents were asked to provide details of individual projects they had been involved in, including project description, commissioner and commissioning process, funding and funders, those involved (e.g., artists, commissioners, curators, partners), and any web or publication references. There was also a free text box for additional information. Criteria for inclusion was kept deliberately broad, drawing on the definition of cultural heritage site as set out by ICOMOS (the International Council on Monuments and Sites 2008), i.e., “a place, locality, natural landscape, settlement area, architectural complex, archaeological site, or standing structure that is recognised and often legally protected as a place of historical and cultural significance.” Building on A&H work the research database initially included places designated as museums but was then refined to focus on in-situ heritage site-based projects only, in other words excluding projects taking place in purpose built museums and galleries holding (ex-situ) object collections or projects presented in natural landscapes with no specific historic or built heritage link. Landscape projects were included where these took place in archaeological sites or the estates of Country House Museums. As of March 2019, the database contained 389 projects. Desk-based research was then conducted into each of these projects, with a total of 3954 project-relevant documents being collated, including newspaper articles and reviews, project briefs and evaluation reports, artist websites, blogs by artists or organizations, press releases, education packs, and YouTube video links.

A sample of 78 projects (20%) was then examined and coded using NVivo. A grounded approach was taken to the analysis – an appropriate method for areas where little information exists and open research questions provide an exploratory starting point which is later refined as analysis progresses (Cresswell Citation2007). Analysis concentrated on documentary materials created around the time of the project's production and presentation in order to be able to track changes in the evolution of the field of practice. Accordingly, a purposive strategy was taken to secure a sample which covered a full range of: project type (temporary commission, exhibition of existing work, residency); site type; and key commissioning programs, across three decades – 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. The selection was then further refined through consideration of the volume and variety of document data available on any individual project. Three initial categories of nodes were generated reflecting the broad research areas of the overall project (Descriptions; Motivations and Origins; and Purpose, benefits, and impacts), from which further clusters developed during coding.

Alongside this, a series of 13 semi-structured interviews (conducted in-person and via video calling) were undertaken. Participants included art in heritage program managers and independent art curators active in this field. Interviewees were selected on the basis of their depth of engagement in the field as captured in the database, and on the recommendation of A&H. Interviews focused on issues such as the challenges of commissioning and presenting site-specific artworks in heritage contexts, the perceived motivations and benefits, and the evolution of both curatorial and artistic practice since the early 1990s.

The discussion below reports the key findings from this research, structured around the core themes that emerged from both the interviews and document analysis, namely: artistic engagement with heritage, the claims made for the benefits and imagined impacts of the practice, and the modalities of visitor engagement. Within this four key characteristics in artists’ engagement with heritage sites are identified – working with object collections, architectural heritage, designed landscapes, and narratives of people and place – although the field is equally characterized by a complex relationship between the intent of commissioners and those of artists, and attitudes toward interpretation and audience.

Artistic Engagement with Heritage Sites

As argued elsewhere, the field of “contemporary art in heritage,” as emerging over the last three decades, has origins within earlier, often artist-led, interventionist practice within museum collections (Black and Farley Citation2020; Cass Citation2015). At first mostly initiated within art museums, since 1990 this interventionist practice rapidly extended to broader types of object collections, including those housed within science and natural history museums and, importantly for this heritage sector-based research, “house-museums.” 40% (n = 155) of projects captured in the MCAHE research database were located in “Country House and Estate” type properties. Looking to this last category as a key location, and beyond into the more diverse terrain of heritage sites, UK-based mapping reveals a massive expansion of artistic activity in this field, from only 15 contemporary art in heritage site projects mapped for the 1990s, to 92 in the 2000s, and 282 recorded for the period 2010–2018. From its tentative and experimental beginnings, by the 2010s this activity could be described as something of a new commissioning industry, supported by major national heritage institutions, including the National Trust and English Heritage and funding from ACE. The National Trust, in particular, has been a key commissioner through its Trust New Art (TNA) programme, which has involved working with over 200 artists to deliver projects at over 100 properties across England and Wales since 2009. This overall growth in commissioning is underpinned by increased investment in specialist training and CPD opportunities for staff at participating heritage properties, provided both internally by the National Trust and through A&H, which since 2017–2018 has operated as the ACE appointed national Sector Support Organization for contemporary art in heritage development. As evidenced in this research, between 2014–2018 at least 95 heritage sites, of various scale and profile, from royal palaces to small local authority-run museums and historical industrial landscapes, had hosted or commissioned such projects. These encompass the work of over 200 artists, including established international names such as Turner Prize-winners Jeremy Deller, Antony Gormley, and Susan Philipsz, alongside many more emerging and less high-profile artists.

Looking further and more qualitatively into the data, this expansion of artistic engagement with heritage can be plotted across multiple facets of heritage site content (see ). Included in this is the material heritage of object collections, architecture and designed landscapes, all of which are encircled by and imbricated with the intangible heritage and historical narratives of people and place held within these sites.

While materiality has long been foregrounded within heritage preservation and conservation practice, the divisibility of these two dimensions, tangible and intangible heritage, is questioned by many scholars. In his book, Architectural Heritage Revisited, Ilan Vit-Suzan, for example, suggests that tangible and intangible heritage are at a minimum “correlated” dimensions, which together “constitute the form and content of heritage. A building's fabric is the form; its associated meaning is the content. Each one changes differently over time. While form shows some permanence and fixation, content is more allusive and fragile” (Vit-Suzan Citation2014, 2 original italics).

With a rather different emphasis, Katrina Schlunke writes of the relational “intertwinement” of heritage materiality with processes of collective and personal memory, what she terms a “material remembering” (Schlunke Citation2013, 253–254). MCAHE mapping research suggests that generating new passages of connection between these correlated tangible and intangible worlds and exploring the emotional bonds between historic objects, buildings, landscapes and the people who once created, used and inhabited them is a key motivation for many artists and curators working in this field. The aim is to open the heritage context out for audiences, who also bring their own lived experiences to these encounters.

Focusing on artistic and curatorial intentionality, the following project examples drawn from the research database give an indication of the varying routes of connection forged by artists in their engagement with these four principal facets of heritage sites, beginning with two contrasting projects working with object collections.

1. Object collections

A Dark Day in Paradise

Artist(s): Clare Twomey/Location: Brighton Royal Pavilion/Dates: 8 June 2010–16 January 2011.

In 2010 thousands of black ceramic butterflies invaded the state rooms and back stairs spaces of Brighton's Royal Pavilion. This was Clare Twomey's A Dark Day in Paradise, developed as part of Museumaker, a program designed to “unlock the creative potential of museum collections” through inspirational contemporary craft-led projects (MLA, Citation2011). In the artist’s own words, Dark Day … was very much a “gut response” to the visual exoticism and decadence of the Pavilion's décor and what she knew about the extravagant lifestyle of its creator, the Prince Regent:

This idea of a black mourning veil coming down over the Pavilion just came to me. You tend to understand butterflies as beautiful things but here, the colour and the way they have manifested themselves is ominous. They are there to judge the opulence (Twomey, quoted in Meakin Citation2010).

Artist(s): Gary McCann/Location: Felbrigg Hall/Dates: 6 January–30 October 2018 (subsequently extended into 2019).

For this Trust New Art project theater designer Gary McCann created a series of fantastical display cabinets containing an often bizarre assemblage of forgotten family objects retrieved from Fellbrigg's cupboards and attics. From these remnants, each cabinet worked to create a new set of imaginative juxtapositions. In one vitrine from “The Diorama,” for example, a group of small porcelain figurines are presented as if escaping “from moth-eaten stuffed weasels [while beside them] fine china lies abandoned within the blasted slopes of a volcanic eruption” (National Trust Citation2018b). For McCann these new cabinets, modeled on the seventeenth Century idea of the Wunderkammer, were about sharing the sense of discovery he had experienced at Felbrigg and offering new visitors to the Hall, “the chance to take part in their own Grand Tour as they move from room to room” (the artist, quoted by Visit Norfolk Citation2018).

2. Architectural heritage

Invisible Structura I&II

Artist(s): David Behar Perahia/Location: Gloucester Cathedral/Dates: 12–28 February & 28th May–11th June 2011.

The exhibitions Invisible Structura I&II were the products of a year-long residency exploring the architectural history of Gloucester Cathedral. As the artist recounts in his residency blog, he was immediately struck with “awe and wonder” at how the proportions of the Norman cathedral had been generated from a basic system of human-scale measurements (Perahia Citation2011). Combining sculpture, sound, video, performance, and drawing, the exhibitions aimed to develop a contemporary sculptural language based on the historic construction principals and technologies used in the Cathedral. In one of the final artworks, Perahia invited members of the public to help him construct a sculpture from wooden scaffolds in the Cathedral's grounds, intending this as a communal reference to the physical labor and community effort needed to create a building of this scale and complexity in the medieval period.

Newton’s Cottage

Artist(s): Observatorium/Location: Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park/Dates: 1 October – 29 November 2014.

Commissioned by the London Legacy Development Corporation and the Canal & River Trust, Newton's Cottage was a large scale architectural sculpture erected on the site and echoing the form of the original lock keeper's cottage at Carpenter's Road Lock. As Ruud Reutelingsperger, a member of the Observatorium team, told design magazine Dezeen: “to reflect on the history of the site, to celebrate the crafts, and to use a material [timber] that you can touch and smell was important to us.” This was thought especially vital on a site which was part of an ambitious new urban development where otherwise there seemed to be “no room for the past” (Reutelingsperger, quoted in Griffiths Citation2014). In the project press release, Reutelingsperger states that the resurrected cottage, used over its two-month stay as the venue for a series of free public events, was intended as “a place for reflection and contemplation” about London's historic waterways, “their importance and their role for London and beyond” (London Legacy Development Corporation press release Citation2014).

3. Designed landscapes

Repens

Artist(s): Anya Gallaccio/Location: Compton Verney/Dates: 1–31 July 2000.

Repens was one of a program of temporary “Art in the Park” projects commissioned for Compton Verney, while the Grade I listed house was in the process of being redeveloped into an art gallery. For her project (curated by Locus+) Anya Gallaccio borrowed an (unrealized) decorative motif originally designed by architect Robert Adam for the ceiling of Compton Verney's Great Hall, enlarging and reproducing this as a pattern mown into the house's surrounding lawns. Reflecting on his own visit experience of Repens in 2000, critic Duncan McLaren (Citation2000) writes:

If “Capability” Brown removed formal decorative features when landscaping the grounds at Compton Verney, Gallaccio has re-introduced them by borrowing from Adam. But not at the cost of Brown's earthy vision. Close up, the lines and patches of unmown grass are studded with thistles and bees: it's ironic that the imposition of such a formal design can effectively bring attention to nature.

Give Me Shelter

Artist(s): various/Location: Attingham Park/Dates: 1 October 2008–27 September 2009.

Curated by Meadow Arts Give Me Shelter brought together existing and newly commissioned works by nine contemporary artists inserted within the extensive landscape and eighteenth Century pleasure ground of Attingham Park. These included sculptural installations in the walled garden and on the lake, and a series of folly-like structures located within the woodlands. One of these, the giant mud and lime-built How to Survive in the Coming Bad Years by Heather and Ivan Morrison, was designed for occupation by local nesting birds, while another, The Double Hut by Henry Krokatsis, echoed and highlighted the subterranean atmosphere of the property's former ice house. Summing up the overall curatorial approach for the project, Meadow Arts highlights the way in which Give Me Shelter offered an interjection on global concerns around climate change and “man's contradictory and fraught relationship with the natural world”: a world which “we exploit and ruin” but also “romanticise,” and “following an age old instinct, rely upon […] to provide us with shelter from various threats” (Meadow Arts Citationn.d.).

4. Narratives of people and place

All in a Day’s Work ().

Artist(s): Catherine Bertola/Location: Ripon Workhouse Museum/Dates: 25 March – 27 November 2016.

In her response to the bleak history of Ripon's Victorian Workhouse Catherine Bertola created a series of sculptural installations housed within three of the sleeping cells used by former workhouse residents. These installations were commissioned as part of A&H's Meeting Point programme, funded by ACE's Museum Resilience Fund, to support smaller museums and heritage organisations in commissioning contemporary art. The installations themselves filled the cells with mounds of materials linked to the different types of labor that inmates were forced to undertake, such as stone breaking, wood chopping and laundry work. A solitary wooden stool was placed at the entrance to each cell, as if presaging the arrival of another unfortunate occupant. Over six days of the project the installations were brought to life by a group of local volunteers specially recruited by the artist. Dressed in Workhouse uniforms the volunteers sat alone in the cells silently performing their prescribed tasks: “Drawing on the history of still life and tableaux, the work seeks to invoke a sense of the endless physical hardship endured by the inmates, and the segregation they experienced within the Workhouse” (Arts&Heritage Citation2018).

Gogmagog – The Voices of the Bells ()

Artist(s): Matt Stokes/Location: Holy Trinity Church Sunderland/Dates: 7 July–23 September 2018.

Holy Trinity is an eighteenth century Grade I listed church located in an historic area of Sunderland. No longer used for regular worship the church is managed and cared for by the Churches Conservation Trust, with an ambition to regenerate it as a new cultural venue for the city. Presented as a sound installation within the nave, Gogmagog celebrated the multi-layered histories of the church and its changing relationships with its surrounding community. As artist Matt Stokes describes it, Gogmagog is a musical reinterpretation of a traditional Triple Bob peal rung on Holy Trinity's bells in 1898:

[this] new version of the peal has been given life by local composers, bell ringers, musicians, singers and choirs, drawing lyrics from the story of the church's historical social roles, paralleled by the thoughts, hopes and fears of the community who inhabit Old Sunderland (Stokes Citation2018).

While it is possible to delineate these four key facets of artistic engagement with heritage sites, what the examples show is that both the intent of commissioners and artists, and the response of artists can vary significantly. Those working in the field of arts and heritage do so within a complex meshwork of perceived power hierarchies, institutional intent, different understandings of the artistic processes, and different expectations of participant and/or audience engagement. The sense from those involved is that the inevitable messiness of the process has increased as the field has expanded. The institutional drivers, evident in artist briefs and from the research interviews, centered on audience engagement and creative interpretation – which could be perceived as instrumental – are perhaps part of the reason that this kind of practice has not gained the critical attention afforded gallery-based artworks. Allied to this is what could be termed a further instrumentalization of the practice through a raft of claims made for its benefit and value, despite a paucity of supporting evidence.

Institutional Claims Made for the Benefits and Value of This Practice

Beyond the stated (and implied) motivations and intentions of producing artists and contemporary art curators, such as those sampled above, disparate and sometimes contradictory claims are made for the public benefits and value of contemporary art in heritage activity by the institutional commissioners and funders of this practice. Analysis suggests that these claims can be matched to three principal value orientations: (a) expansion and diversification of the heritage audience; (b) interpretive imperatives; (c) artists’ and arts sector development. Any, or indeed all, of these may hold a place in the business case for initiating a contemporary art in heritage project and in the framework of success criteria for post-activity evaluation.

Expansion and Diversification of the Heritage Audience

There is growing evidence and recognition within the UK heritage sector that heritage visitor audiences represent a narrow, mainly older, middle class and largely white demographic. The 2017–2018 statistics released by the UK Government in their annual “Taking Part” (England) survey show that this visitor demographic had changed little since the survey started in 2005–2006 (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport 2018). The 2017–2018 survey showed “significant increases” in heritage engagement since 2005/2006 among all adults except for those in the 25–44 age group. It notes “a significant and persistent heritage engagement gap” of around 20% between adults in the upper and lower socio–economic groups, with 81% of adults in the upper socio–economic group visiting a heritage site in the last 12 months compared to only 61% in the lower group. The report also highlights the fact that BAME groups continue to have significantly lower levels of engagement with heritage sites than the White ethnic group: at 58% visiting for BAME compared to 77% in White groups. For major heritage charities like the National Trust and English Heritage, who are reliant on memberships and entry charges for much of their income, increasing visitor numbers and diversification of this traditional (and ageing) audience is highlighted as a key business imperative. As the interview data and document analysis shows, while the needs and interests of this traditional audience remains a key focus for the heritage sector as a whole, contemporary art activity is commonly seen as a way to attract and develop new and younger audiences, particularly Millennials. This association of the visual arts and especially contemporary art with a younger demographic seems to be borne out in recent research published by The Audience Agency, which found a stronger engagement with the visual arts among the 16–34 age group compared to other art forms. The report also suggests that visual arts audiences “reflect the ethnic makeup of the English population more closely than most other artforms” (The Audience Agency Citation2019, 8).

Contemporary arts commissions, whether sited inside or outdoors, are also seen as opportunities to move visitors differently around a heritage property, away from areas with the most visitor traffic to parts of a site, building or collection that usually have a lower footfall or which are not normally open to the public. Importantly, in offering something “different” and “new” temporary arts projects can be used as part of a strategy to attract repeat visitors. Beyond actual visitor numbers, engagement with contemporary art may also be part of a strategy to change the wider public image of a heritage organization, with concomitant positive impact on longer-term institutional sustainability (e.g., in terms of memberships, volunteer and staff base or in attracting future charitable donations). In the interviews and document data this ambition is often expressed in terms of boosting a sense of contemporary “relevance” and “connection” with heritage places, why they are important for people today, and crucially for organizations that are most usually understood as conservation bodies, why these “special” places (collections, buildings, and landscapes) should be preserved for the future. As the National Trust states in reference to its aspirations “to move, teach and inspire” (a key element of its Playing our part development strategy launched in 2015):

People's tastes are changing and their expectations continue to grow. We’ll work harder to give our visitors experiences that are emotionally rewarding, intellectually stimulating and inspire them to support our cause. We will invest in major changes at our most visited houses to transform how we tell the story of why they matter (National Trust, Citation2019.)

Interpretive Imperatives

As with many of the arts projects commissioned for “Challenging Histories,” contemporary art at heritage sites is commonly seen as means to reinvigorate normative interpretations and as a methodology for revealing hidden narratives and untold (and often more “difficult”) histories of a site. Reflecting on the “Unravelled at Nymans” project (2012), and emphasizing the critical and interventionist roots of contemporary art in heritage practice, “Unravelled” curator Matt Smith states:

As with any history, the stories told at historic properties are selective. This is done partly to provide visitors with a coherent narrative, partly to exploit the most interesting stories, and partly reflects the interests and values of the staff and organisation that run the house. Artistic intervention can make this selectivity more apparent and thus open to scrutiny (Smith Citation2012).

Speaking about the institutional and staff ambitions behind two new artworks commissioned for National Trust's Gibside in 2018 (generated as part of MCAHE) the property's Visitor Operations Manager observed that traditional methods of interpretation, such as guided tours and interpretive panels, were not really delivering on the Trust's “move, teach and inspire” strategy. Bringing in contemporary artists and commissioning new artworks that respond to the site “gives us a way of asking questions and challenging people in a way that we would struggle to do just using our own voice. […] it is a different way of telling a story” (MCAHE research interview 2017). This desire to open up the range of interpretive perspectives that might be brought to a site, and thus the diversity of potential stories that might be told about and within it, was further emphasized in a research interview with the Trust's National Public Programmes Curator, a keen champion of polyvocal approaches to interpretation and especially of contemporary artists’ abilities to interrogate and challenge visitors’, and the Trust's own assumptions about a site's value, historical and cultural interest. For this curator, contemporary art in heritage projects were all about: “moving away from - this is our institutional voice, this is our institutional line, this is the one way that you should see this object - more towards what might this mean for real people today” (MCAHE research interview 2018).

While there is a clear institutional drive here towards welcoming and embracing fresh ideas, contemporary art in heritage commissioning brings real challenges in terms of maintaining the legibility of such projects for visitors and in providing artists with a genuine opportunity for critical engagement with heritage site. Although many artists will respond positively to a well-defined brief, if framed too tightly within a specific interpretive agenda there is a danger that the creative potential of a project, and the new insights and values that artistic engagement is expected to bring, may be curtailed.

Artists’ and Arts Sector Development

Not surprisingly, the opportunity to extend the possibilities for individual creative practice is a key motivation for artists engaging with heritage site projects. Many artists quoted in the data sample spoke of the fascination of working with such visually and materially rich environments and their enjoyment of the research process involved in a heritage-based commission or residency. While most commissioned projects will link in some way with an artist’s ongoing subject interests (e.g., Marcus Coates 2018 Conference for the Birds at Cherryburn, the latest in Coates's long-term artistic investigation of animal worlds) or working processes, crucially, such projects also offer opportunities to extend artistic practice, through engagement with new subject matter and source material, new environments and audiences. Reflecting on the works produced for her residency exhibition, Folded, at Leighton House Museum (7 December 2011–2015 January 2012), artist Clare Burnett writes:

At first I thought the residency would be just about how I could work in a historical space, but I have been surprised by the way so many themes that run through my work have been brought together: the discarded materials I’ve been experimenting with, how pared down shapes can articulate a space […] The residency has also made me push my work further and raised new questions for the future (Folded Citation2012).

Equally important in ACE's support for contemporary art in heritage (at the National Trust or through other heritage organizations) is the expressed desire to grow the audience base for contemporary art. As one ACE Visual Arts Relationship Manager explained, expanding the types of venue where the public can encounter and experience contemporary art is a key part of this audience development strategy:

We use the phrase ‘Art in Unexpected Places’. It's not confined to visual arts and it's not confined to heritage. It's basically about opportunities for audiences to engage with art outside the conventional arts infrastructure and the opportunities that that provides to reach different audiences who might not, for whatever reason, because of where they are located or because they don't think [contemporary art is for them]. They don't consume art via those conventional galleries (MCAHE research interview, 2017).

While the strategy to draw heritage visitors into perhaps unexpected encounters with contemporary art remains the dominant trend in this field, some heritage-based art programs and exhibitions included in the MCAHE mapping, especially where working with high profile “blue chip” artists, take a different approach to audience diversification: making a deliberate appeal to established visual art audiences. The “Beyond Limits” sculpture exhibitions at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, organized by Sotherby's (2005–2015) and the series of contemporary artists’ projects (by James Turrell, Richard Long, and Damien Hirst) at Houghton Hall in Norfolk (2015–2018) could all be regarded as examples of this approach. Rather than commissioning new artworks that might encourage and challenge heritage visitors to reconsider normative understandings of a site (its architecture, collections or landscape), as in most of the TNA programming for example, arguably, in these projects (which focus on the presentation of existing artworks), the emphasis of interplay between artwork and site is reversed: the heritage site forming a context for re-examining the possibilities for viewing and experiencing the artwork.

Expanding the Modalities for Art in Heritage Engagement

Arts approaches offer new ways of experiencing places, arts languages offer new ways of expressing experience of places, arts expressions can contribute to life-affirming cultural values which seek to encourage understanding of our interdependence with place […] Arts approaches offer new ways of experiencing places using our senses, our emotions and our imaginations […] The arts are also known for the value they place on feelings, for the importance of being receptive to the emotional impact of a subject. They encourage people to become more conscious of how places affect them, how they make them feel. The arts encourage empathy; understanding life from another perspective. (Dungey Citation1989)

So states Jan Dungey in a rare early argument for the value of contemporary art in heritage (Citation1989, 229–230, original italics) that foretells the strength of later academic interest in heritage and affect (see for example Staiff Citation2014; Smith, Wetherall, and Campbell Citation2018; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017). Considered from this perspective contemporary art in heritage production opens-up alternative modalities of audience engagement with heritage that go beyond discursive and authorized interpretations of site. As Russell Staiff argues, heritage is not just about “understanding”:

heritage is not there to provide knowledge in a direct way, rather it's about a whole series of interconnections and networks that encourage a multitude of responses and even deepened experiences, deepened reflections and a heightening of the senses. Heritage is more than logical things and more than the logic of thing (Staiff Citation2014, 68).

Conclusion

The massive expansion of contemporary art in heritage between 1990 and 2018 arguably means that it can now be regarded as a commissioning industry in its own right. The particularities of the heritage context and nature of artistic practice within make it a specific strand of practice allied to, but distinct from, the broader field of public art activity. The strategic support of Arts Council England and major national heritage organizations including the National Trust, English Heritage and the Canal and River Trust has been critical in the expansion of the field, but has also created tensions where the institutional, and ultimately instrumental, expectations held of artists and artworks do not necessarily sit well with an artist's own practice, their responses to site and motivations for involvement. The challenges of the practice are also inherent in the artists’ briefs – which often call for disruption, infiltration, subversion – and yet the repercussions this sometimes has are then problematic or not expected, and hence not always well managed, by the commissioning organization.

As shown here disparate and sometimes contradictory claims are made for the benefits and value of this practice, orientated around three imperatives: audience engagement, site interpretation, and arts development. Increasingly artists are contending with complex local and global histories, and there has been a notable shift from object-based working, drawn from institutional critique of the museum, to the tangible and intangible heritage, seen and unseen histories, of people and places. Arguably this is a particular value that contemporary art practice opens up for the heritage sector, creating opportunities for new modes of visitor engagement with heritage sites, including sensory, emotional, imaginative, and critical engagement. This reflects a desire within heritage organizations to shift perceptions of heritage sites from static with passive consumption toward sites becoming living cultural resources with real contemporary relevance (National Trust Citation2018a). Contemporary art can play a role in this but this research has indicated that for this to happen (within commissioning organizations, and for artists) the framing of this activity needs to move from its largely instrumental and audience-orientated narrative, toward a more critical understanding of the practice itself.

Acknowledgements

This article was submitted to this Journal in January 2020 and draws on research conducted in 2017–2020 as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project, “Mapping Contemporary Art in the Heritage Experience: Creation, Consumption and Exchange” (MCAHE) led by Newcastle University (PI Prof. Andrew Burton) in collaboration with the University of Leeds, National Trust, Arts & Heritage, the Churches Conservation Trust, and English Heritage. We would very much like to thank all the curators, program managers, and heritage site staff who contributed to our series of research interviews and whose commentaries are quoted in this article. Our thanks also go to MCAHE project assistant Sophie Headdon who provided invaluable support on document data collection.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arts&Heritage. 2018. “Meeting Point Ripon Museums - Arts & Heritage.” Accessed 5 October 2018. https://www.artsandheritage.org.uk/projects/ripon-museums/.

- Audience Agency. 2019. Audiences for the Visual Arts. London; Manchester: The Audience Agency.

- Black, Niki, and Rebecca Farley. 2020. “Mapping Contemporary Art in the Heritage Experience.” In Contemporary Art in Heritage Places, edited by Nick Cass, Anna Powell, and Gill Park, 15–31. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cass, Nick. 2015. “Interventions in a Shrine: Contemporary Art at the Brontë Parsonage Museum.” PhD Thesis, University of Leeds.

- Cass, Nick, Anna Powell, and Gill Park, eds. 2020. Contemporary Art in Heritage Places. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chubb, Shirley. 2007. “Intervention, Location and Cultural Positioning: Working as a Contemporary Artist Curator in British Museums.” PhD Thesis, University of Brighton.

- Cresswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. 2018. “Taking Part Survey: England Adult Report 2017-18.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/740242/180911_Taking_Part_Adult_Annual_Report_-_Revised.pdf.

- Dodd, Jocelyn, and Sarah Plumb. 2018. “Whose Voice Do We Hear?” In Prejudice and Pride: LGBTQ Heritage and Its Contemporary Implications, edited by Richard Sandell, Rachael Lennon, and Matt Smith, 75–80. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, University of Leicester.

- Dungey, Jan. 1989. “Where Arts, Imagination and Environment Meet.” In Heritage Interpretation: Volume 1 The Natural and Built Environment, edited by D. L. Uzzell, 229–231. London: Belhaven Press.

- Folded. 2012. London: Leighton House Museum.

- Griffiths, Alyn. 2014. “Skeletal Pavilion Shaped Like a Lock Keeper’s Cottage Pops Up in London’s Olympic Park.” Dezeen. October. https://www.dezeen.com/2014/10/22/observatorium-1930s-lock-keepers-cottage-wood-london-olympic-park/.

- Lennon, R. 2018. “For Ever, for Everyone?” In Prejudice and Pride: LGBTQ Heritage and its Contemporary Implications, edited by Richard Sandell, Rachael Lennon, and Matt Smith, 9–16. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, University of Leicester.

- London Legacy Development Corporation. 2014. “Old Lock-Keeper’s Cottage is Resurrected on Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.” [Press release].

- McLaren, Duncan. 2000. “Fine Art is Put Out to Grass.” The Independent, September 6.

- McShine, Kynaston. 1999. The Museum as Muse: Artists Reflect. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

- Meadow Arts. n.d. “Meadow Arts Give Me Shelter - Attingham Park, Shrewsbury, Shropshire.” Accessed 11 July 2018. https://www.meadowarts.org/exhibitions/give-me-shelter.

- Meakin, Níone. 2010. “A Dark Day In Paradise, Royal Pavilion, June 8 to January 16, 2011.” The Argus, June 4.

- Museums Libraries and Archives Council. 2011. Sharing the Impact of Museumaker. London: MLA.

- National Trust. 2014. Memorandum of Understanding between Arts Council England and the National Trust, April 2014. London; Swindon: Arts Council England; The National Trust.

- National Trust. 2016. “Call for Expressions of Interest: Contemporary Art Project Brief - Hanbury Hall, Worcester.” Swindon: National Trust.

- National Trust. 2018a. “Annual Report 2017/18.” Swindon: National Trust.

- National Trust. 2018b. “Exploring the Wild and Exotic at Felbrigg National Trust.” Accessed 20 March 2018. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/felbrigg-hall-gardens-and-estate/features/exploring-the-wild-and-exotic-at-felbrigg?platform=hootsuite.

- National Trust. 2019. Strategy. Accessed 2 September 2019. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/strategy.

- Perahia, David Behar. 2011. INVISIBLE STRUCTURA I Exhibition David Behar Perahia Diary. Accessed September 10, 2018. https://davidbeharperahia.wordpress.com/2011/03/28/invisible-structura-i-exhibition/.

- Putnam, James. 2001. Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Schlunke, Katrina. 2013. “Memory and Materiality.” Memory Studies 6 (3): 253–261. doi:10.1177/1750698013482864.

- Smith, Matt. 2012. “The Art of Unravelling the Past.” Engage 31: 73–78.

- Smith, L., M. Wetherall, and G. Campbell. 2018. Emotion, Affective Practices, and the Past in the Present. London; New York: Routledge.

- Staiff, Russell. 2014. Re-imagining Heritage Interpretation: Enchanting the Past-Future. Farnham; Burlington: Ashgate.

- Stokes, Matt. 2018. Gogmagog – the Voices of the Bells. Leaflet from Installation at Holy Trinity Church, Sunderland.

- Tolia-Kelly, Divia P., Emma Waterton, and Steve Watson. 2017. Heritage, Affect and Emotion: Politics, Practices and Infrastructures. London, New York: Routledge.

- Visit Norfolk. 2018. “Curious Cabinets at Felbrigg Hall.” Accessed September 10, 2018.

- Vit-Suzan, Ilan. 2014. Architectural Heritage Revisited: A Holistic Engagement of its Tangible and Intangible Constituents. Abingdon; New York: Routledge.

- Zebracki, Martin, Rob Van Der Vaart, and Irina Van Aalst. 2010. “Deconstructing Public Artopia: Situating Public-Art Claims within Practice.” Geoforum 41 (5): 786–795. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.04.011.