ABSTRACT

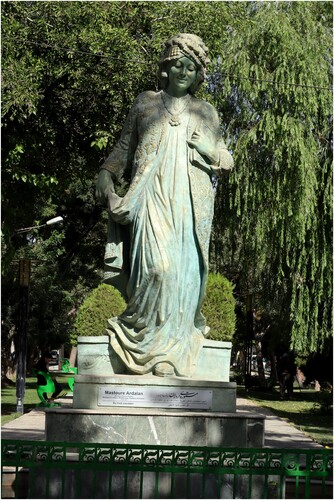

Between 2009 and 2011, the Kurdish sculptor Hadî Ziaoddînî created a statue of poet Mestûre Erdalan (1805–1847), in the city of Sine (Sanandaj, Iranian Kurdistan or Rojhelat). A woman standing, carrying a book in her hand, the figure of Mestûre is unique in the Islamic Republic of Iran. She is not wearing the obligatory hijab but a Kurdish kofî. This paper presents the evolving representation and reception of Mestûre, the first Kurdish female poet and chronicler. The existing research on heritage in Iran focuses mainly on the policies of Pahlavi and Islamic regimes, tourism and conservation. This paper reveals the dissonant heritage-making that inspires Kurdish ethnic and national identity and the empowerment of women in Iran. The latter gained momentum, especially after the killing of the Kurdish woman, Jîna (Mahsa) Amînî, by the morality police in 2022. The multi-layered heritage performance engages identity politics, artistic creation and the new practice of visiting the statue of Mestûre. Starting from Ziaoddînî’s work as the focal point of discussion, the study identifies various links between the statue and other artistic products, as well as investigates the contemporary relationship between Mestûre and the inhabitants of Sine. The relationship is mediated by the sculpture and the moral imagination it stirs in empowering Kurdish women.

Introduction

With a population of more than 500,000, Sine (Sanandaj), the capital of Kordestan province, situated in the Zagros mountains, is the main Kurdish cultural and political center in Iran. In the past, it was the capital of the powerful Kurdish emirate of Erdelan, one of the quasi-independent Kurdish emirates that were loosely connected to either the Persian or the Ottoman Empire. In 2019 Sine was awarded the title of a “City of Music” by the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (Cities of Music Citation2019) ().

However, Iran’s centralizing policy, which intensified with the advent of modern national states in the Middle East in the twentieth century, brought radical changes to the Kurdish reality (Cabi Citation2022). Some authors described them in terms of internal colonialism (Soleimani and Mohammadpour Citation2019). The border now cuts across the Kurdish land (Kurdistan), partitioning it among the national states of Iran, Turkey, Iraq and Syria. Despite many attempts to gain some degree of independence, Kurds were not allowed any autonomy in Iran, and the government continues to harshly suppress their cultural and political rights through regulations that often restrict Kurdish publications and schools, or result in arbitrary arrests of activists, unfair trials and executions of prisoners (Cabi Citation2022; Sheyholislami Citation2023; Vali Citation2020). The brutality of the regime became visible especially in the last months of 2022 after the morality police killed the Kurdish woman Jîna (Mahsa) Emînî for not wearing her hijab properly, which led to the protests labeled by some as the feminist revolution in Iran. Despite the ruthlessness of the regime, protesters demonstrated surprising creativity in various artistic performances.

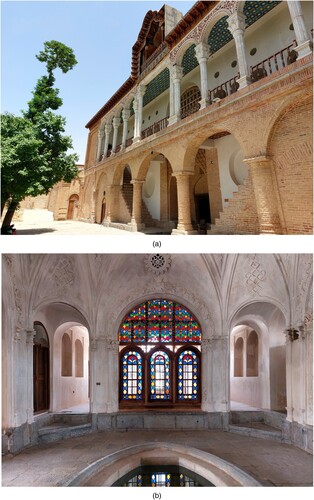

Not far from the Awyer (Abidar) mountain overlooking Sine, in the richer upper part of the city, there is a mansion known as Xosrow Abad, which is today a tourist attraction. At the entrance to the green alley leading to the mansion, a five-meter statue of the Kurdish female poet and chronicler Mah Şeref Xanim Kurdistanî, or Mestûre Erdelan, was erected. The statue was created in 2009 by the Kurdish sculptor, Hadî Ziaoddînî, from Sine. He has created many other statues and sculptures that have brought him fame all over Rojhelat, Iran and in other parts of Kurdistan, but the statue of Mestûre could only be erected in 2011 after negotiations between him, the city council and the Iranian regime – the Etla’at, (Iranian security and intelligence service). At the beginning of 2022, the sculpture was granted National Tangible Heritage status in Iran (Tehran Times Citation2022) ().

The statue is unique for several reasons. First of all, it is one of the very few statues of a female subject in Iran. Secondly, Mestûre is not wearing the obligatory head cover, the hijab, but the traditional Kurdish kofî (hat). The history of its creation reflects what Tunbridge and Ashworth call dissonant heritage (1996), and also a successful consensus reached finally by the aforementioned actors for the benefit of Sine’s inhabitants. What is more, rooted in folkloric and literary inspiration, as well as in Ziaoddînî’s imagination, mystical intuition, and research, the figure provokes a discussion about the various uses of heritage (Smith Citation2006; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017; Waterton and Watson Citation2015; Wu and Hou Citation2015) and the interactions among them which often challenge the Western-oriented approach to heritage (Smith Citation2006; Wu and Hou Citation2015). This paper also draws attention to the Kurdish claims of humanness and universality of their heritage against the minoritizing and Eurocentric lenses of Iranian (Soleimani and Mohammadpour Citation2019) and global heritage policies. As will be shown, the process of the reception and representation of Mestûre is multi-layered, engaging identity politics, various discourses, affects, artistic creation and the new practice of visiting her statue and even talking with her. Therefore, the aim of this paper is primarily to expose the dissonant heritage performance and discourses that have developed on the margins of official Iranian heritage. Secondly, it aims to track the interactions among the various ensuing emerging expressions of heritage (literature, art and their interpretations) to show how they evolved and inspired each other and were performed and connected with Kurdish identity, women’s empowerment and dissent from the oppression of the Islamic Republic. Hence the paper does not focus exclusively on the feminist practices but traces them with regard to the earlier artistic performances by men artists which lead to the creation of the sculpture. Mestûre’s heritage, which made a journey from literature to public space of the modern city stirs Kurdish women’s imagination, courage and self-confidence. However, women’s interpretations of Mestûre and her sculpture are not identical with the imaginations that inspired the creation of the statue and this is where the transformation of heritage practices become visible. What all these performances share is an intimacy with Mestûre which encourages a “network of passionate human beings engaging with each other” through art and invites political claims (Plummer Citation2003, 7).

Anna Reading underlined that gender perspectives on heritage emerged recently from diverse disciplines. She contended that the feminist approach includes “attentiveness to the gendered curation, protection, preservation and commemoration of the past” (Citation2015, 398). While this is certainly a useful overview of feminist heritage practices, it says little about any imaginative mechanisms that connect women their subjectivities and their heritages. Women’s empowerment has been often understood in terms of political rights, social movements, and economic and institutional solutions, and the role of imagination was rarely discussed. However, there are still corners of the earth where imaginary worlds constitute the only reliable refuge from the harsh reality, and such circumstances often equip imagination with political meaning.

In recent decades, feminist perspectives within Middle Eastern Studies have developed rapidly, encompassing a wide range of fields and ethnic groups. Nevertheless, studies on the empowerment of women through heritage are still very scarce, and scattered among various disciplines. For example, the representations of ancient women painted on the walls in Cairo during the Arab Spring were only briefly mentioned as empowering symbols in an article about gender and graffiti (Abaza Citation2023). Empowerment through heritage was also discussed in relation to women from minoritized groups, who are in a “doubled periphery position,” as representatives of a minority and as women (Maghsudeh Citation2023, 105). Existing studies focus mainly on continuation, conservation and preservation of traditions (Abbadi Citation2020; Maghsudeh Citation2023; Shisheliakina Citation2022), financial empowerment (Abbadi Citation2020; Shisheliakina Citation2022) or overcoming traumas (Abbadi Citation2020). Hence, this paper proposes another approach to women’s empowerment through heritage by shedding light on representation, interpretation and contemporary encounters with the historical figure, the Kurdish female poet. These practices are understood in this study as intertwined expressions of heritage inspiring imaginative mechanisms of ethnic and female empowerment. In contrast to the feminist discourse in Kurdish studies, this analysis does not concentrate on pre-Islamic or folkloric female characters (Alakom Citation2013; Caglayan Citation2012; Deniz Citation2024) but investigates the figure of Mestûre, who is rooted in the Kurdish Sunni Islamic past, challenging omissions and demonstrating the paradoxes and intricacies of feminist heritage-making in the Shi’i republic of Iran.

The studies of heritage in Iran have focused on the transformation of heritage policy marked by the political turmoil in Iran’s twentieth-century history. The Pahlavi regime’s invention of grand pre-Islamic heritage, inspired largely by Western scholars, constituted the cornerstone of the Pahlavi monarchy (1925–1979, Grigor Citation2004; Citation2005; Hodjat Citation1995). Nevertheless, some limited examples of a more citizen-focused art, combining motifs from Shi’i folklore with modernist ideas, were also revealed (Amini Citation2020). The minorities and their peripheral lands and heritages were, however, ignored by the Shah’s policy as useless folklore (Grigor Citation2005). The 1979 Islamic revolution resulted in a temporary rejection of everything pre-Islamic and even in hostility to the arts (Grigor Citation2005; Hodjat Citation1995; Mahdizadeh Citation2021; Mozaffari Citation2013; Mozaffari Citation2015). The gradual acknowledgment of the ancient Iranian past by the Islamic authorities coincided with the Iran-Iraq war (1980–1988) and the necessity to stir national sentiments. Also, the new heritage discourse grew within the developing Islamic ideology (Hodjat Citation1995). In the post-war era of President Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989–1997), the commodification of heritage was perceived as an economic stimulus for Iran (Mozaffari Citation2015). Heritage from below was identified with “grass-roots heritage societies” and social movements (Jones, Mozaffari, and Jasper Citation2017; Mozaffari Citation2015), or “community support for sustainable tourism development” (Pezeshki, Khodadadi, and Bagheri Citation2023). Nevertheless, even though highlighting the perspectives “from below,” all these studies present Iranian heritage as an ethnic and linguistic monolith and largely ignore heritage-making conducted by minorities such as the Kurds, Azeris, Baluch and many others. Publications often concentrate on the globally recognizable heritage sites such as Pasargadae, Persepolis or the gardens of Shiraz (Grigor Citation2005; Jones, Mozaffari, and Jasper Citation2017; Mahdizadeh Citation2021; Mozaffari Citation2015) and neglect places little known by the outside world, such as Iranian Kurdistan. This paper addresses some of these gaps and draws attention to heritage uses among Kurds. Instead of focusing on folklore, it points to Kurdish classical and modern literature, art and the urban space of Sine () .

The process of representing women in arts in the urban space of Iran began in the Pahlavi era and was continued in the Islamic Republic (Ghaeli, Sararoudi, and Ghorbani Citation(1399) 2020). Surprisingly, these two periods demonstrate similarities, such as the prevalence of the mother figure. The interesting exception was Woman Without Veil by Parviz Tanavoli, erected in the sixties in the park in Tehran designed by the architect Kamran Diba (the cousin of Queen Farah Diba Pahlavi, the Shah’s third wife and a patron of arts). According to Amini, it was “the first and last public representation of a modern woman in the history of Iranian public art” (Citation2020, 202). In the nineties, during the presidency of Mohammed Khatami (1997–2005), the Islamic authorities took a more favorable stance toward art and artistic representations of humans which stirred the creation of public statues, but mainly of men. The few existing statues of women represent mothers and mothers of martyrs, characters from traditional stories, abstract figures of women, and only very rarely individuals (Ghaeli, Sararoudi, and Ghorbani Citation(1399) 2020). While Ghaeli, Sararoudi and Ghorbani discuss only the sculptures located in Tehran, the authors of this paper identified five other statues of women in the Kurdish cities of Sine, Dîwander, Bane and Serdeşt. Those in Sine and Dîwander are by Ziaoddînî, the three others (two in Bane and one in Serdeşt) are by Abubekr Pîran. They are white, wear headscarves and are figures of mothers. A gold statue of the poet Parvin Etesami is located in the city of Tabriz (East Azerbaijan Province) in the garden of her father’s house, which became a museum to her. Hence, this paper draws attention to the statue of an individual woman, an important empowering factor, as stressed by many of those interviewed.

In the following sections of this paper, after introducing the methodology, the figure of Mestûre Erdelan and her emerging heritage will be presented. The focus will then pass to the erection of Ziaoddînî’s statue and to the new artistic discourse, the performances and works it inspired, with special attention to Mestûre’s Kurdish identity and her womanhood.

Methodology

The study is based on ethnographic fieldwork, photography, text analysis and semi-structured interviews and conversations with 27 Kurdish artists, photographers, writers, activists, actors, film directors, researchers, students, a carpenter and an Erdelan family member, 17 of whom were women and 10 men, from Rojhelat. Nineteen of the interviews were conducted in Sine, four in Bane and two in Tehran, mainly in July 2022. Three interviews were conducted with people living in the UK, Germany and the USA who were known to be involved in the subject of Mestûre. Importantly, the majority of the interviews were conducted in the Sorani and Sineyi dialects of Kurdish, one in Farsi and three in English. Conducting the interviews in heritage languages increases trust and invites themes that are not always revealed when speaking the official majority language (Olko Citation2018; Smith Citation2021).

The authors contacted artists and intellectuals who had declared interest in Mestûre and in Ziaoddînî’s sculpture, or whose interest was expected because of their intellectual and artistic engagement. The authors chose artists because they are deemed to be masters of imagination. Women artists and activists were asked if they knew Mestûre, her works and her statue, and what she and her statue meant to them. To elicit a more detailed reflection, a picture of the sculpture was used. While interviewing Cemal Ehmedî Ayin and Hadî Ziaoddînî, the authors focused on the reasons for their literary and artistic passion for Mestûre and on the history of the statue. The study benefited from occasional chats such as with the carpenter, but the research in Iran inevitably had limitations. Discretion had to be the main motto, because activists and artists were often under the surveillance of Etla’at and interviewing them openly might have brought danger to both the participants and the authors. For that reason, apart from a few prominent Kurdish individuals, the names of the participants in the study were changed.

The understanding of heritage in this study goes beyond the mere portrayal of a historical Kurdish figure. Rather, it is perceived as an act of communication, a meaning-making and empowering experience, because “the real moment of heritage when our emotions and sense of self are truly engaged is in the act of passing on and receiving memories and knowledge” (Smith Citation2006, 2). Such acts evoke moral imagination, which fills the gaps between abstract ideas, memories and observations (Steiner Citation2000), invites awareness of the various dimensions embedded in a situation and impacts our actions (Nussbaum Citation1990; Werhane and Moriarty Citation2009). Hence imagination hosts, refurbishes and recreates our memory and thus constitutes an invisible operational space for heritage performances. This space can be further developed by art in turning it into a tangible object like the sculpture of Mestûre.

The authors see heritage as “the present past” (Butler Citation2006; Fowler Citation1992; Wu and Hou Citation2015) and specifically focus on any possible “abuses” of the past (Waterton and Watson Citation2015, 12) inspired by people’s present needs. Rephrasing Waterton and Watson, it can be said that heritage experience is constructed within and without the realm of imagination and representation, including moments of subjective and inter-subjective engagement and the interplay between them (12). As will be shown, these interplays result in multi-layered performances citing existing discourses and recreating them in new forms, both material and non-material. They may come into being as a sculpture emerging from various oral, literary and mystical inspirations, or as the intimate practice of visiting Mestûre’s statue and talking with her. They are reconstructed in a range of new artistic forms, too numerous for the scope of this paper. Furthermore, such performances not only constitute present interactions but reach out “to imagined and future audiences” (Haldrup and Bærenholdt Citation2015, 54). The Kurdish process of recreating Mestûre’s image cannot be reduced to aesthetic endeavor, nor can their practice of visiting the sculpture be perceived simply as leisure and tourism. Following Wu and Hou, these practices seem to possess a deeply moral and political meaning and “are intended to activate a sense of virtue” (Citation2015, 45), stir moral imagination (Nussbaum Citation1990; Steiner Citation2000; Werhane and Moriarty. Citation2009) and thus empower people.

Figure 4. The bust of Mestûre in the park of Sami Abdul Rehman, Hewlêr (Erbil), Iraqi Kurdistan, 2011.

Initially, the sense of virtue and moral imagination was connected with Kurdishness or “being a Kurd,” which is representative of a group whose language, cultural heritage and political desires have been suppressed by the Iranian regimes of both the Pahlavi shahs and the ayatollahs (Cabi Citation2022; McDowall Citation2004; Sheyholislami Citation2023; Soleimani and Mohammadpour Citation2019; Vali Citation2020). Applying Tunbridge and Ashworth’s notion of “dissonant heritage,” it can be concluded that official Iranian heritage, which in the twentieth century strongly emphasized the greatness and unifying potential of the Farsi language and the culture expressed in it (Cabi Citation2021; Grigor Citation2005; Sheyholislami Citation2023), was prone to disinherit the other nations, as well as marginalize and suppress their distinctive historical experiences, languages and cultures. The Iranian regime sought to both deny the historical record in which the heritage of other ethnic groups is rooted and to deflect the modern nationality of other groups by their minoritizing and museumification (Tunbridge and Ashworth Citation1996, 36). This policy was based on creating and deepening the division between the “official,” identified with the Iranian state, and the “local,” associated with various, sometimes rebellious, minorities (Cabi Citation2021; Citation2022; Vali Citation2020).

It is not only the Islamic Republic, but also many Iranian dissidents and intellectuals who tend to ignore or silence the Kurdish minority (Soleimani and Mohammadpour Citation2019). The most widespread form of silencing is to use the word Iranian rather than Kurdish. Of course, the word Iranian encompasses Kurdish, because the Kurdish language belongs to the wider Iranian family of languages, but more often than not the word was used to minoritize any Kurdish participation in Iran. The latest example is Jîna Emînî, who in the Iranian sources is often called only by her official name Mahsa, and her Kurdish identity is rarely mentioned. The same happens with the slogan of the 2022 revolution, Jin, Jiyan, Azadî (Women, Life, Freedom) which used to be a Kurdish leftist slogan that was popular among the Kurds in Turkey and Syria (Käser Citation2021). Recently, it was translated into Farsi and presented to the world as Zan, zandegi, azadi, with little mention of its Kurdish origin (Ghaderi Citation2024). Hence, the dissonant heritage consists of – on the one hand – ignoring or silencing Kurdish identity by the Iranian side and – on the other – challenging this policy by the Kurds, stressing the existence of the specifically Kurdish past and heritage. Throughout the twentieth century, both Pahlavi and Islamic regimes showed little interest in Mestûre Erdalan’s heritage. Naming the statue as being of “national Iranian heritage” took place only after the artwork became important for the Kurds, which can be interpreted as an intention to take control of the emerging heritage narrative.

What follows is that being a Kurd in Iran entails explicit attachment to and care for Kurdish historical, linguistic and cultural heritage, perceived as “distinct” from, or at least “not identical” to Persian or Iranian heritage. Contrary to the official narrative, the Kurdish opposition does not consider it “local,” “tribal” or “ethnic,” but “national Kurdish” (Vali Citation2020). This was also evident in the majority of the interviews. The interlocutors pointed to links with the heritage of the Kurds in neighboring countries and expressed a wish to interact with world heritage without interference from the Iranian authorities and culture. As demonstrated in another study, the heritage is no longer perceived by the Kurds only as “national Kurdish” but as inseparable part of the world heritage (Bocheńska and Ghaderi Citation2023). As will be shown further, Mestûre, whose biography links the emirates of Erdelan and Baban (today Iraqi Kurdistan), is a connecting link between Rojhelat and Başûr (Kurdistan Region of Iraq). Gradually, however, Mestûre’s talent, and her tragic life and death in exile in Baban, became associated also with women’s history, suffering and emancipation. Hence, by engaging gender, the heritage of Mestûre and the Kurdish politics of dissent have been enriched with a new dimension. The aforementioned sense of virtue in relation to Mestûre is therefore politicized in two ways. It appeals both to the Kurdish cultural and national struggle and to the struggle of women in Iran, which, in the case of Kurdish women, is intersectional (Fallah Citation2019).

Mah Şeref Xanim Kurdistanî, whose literary pseudonym Mestûre means “hidden” and “innocent,” and who was also the author of a book on Islamic jurisprudence, inevitably evokes the Muslim woman’s piety. Muslim piety is today challenged by many women in Iran in their struggle against the obligatory hijab. However, the statue portrays Mestûre not in the prescribed hijab, but in a Kurdish kofî. Therefore, the artistic solution, though rooted in Ziaoddînî’s vision of the Kurdish past, unexpectedly started to appeal to the Kurdish and Iranian present. It is because, nowadays, the headgear proposed by Ziaoddînî reflects dissent from the hijab, expressed either by wearing it loosely or by replacing it with a hat or hood. In July 2022 in Sine, there were also women with their hair uncovered. This radical anti-hijab stance intensified throughout Iran after the death of Jîna Emînî. But it must be remembered that Kurdish opposition in Sine includes also the practicing Muslims, such as those from the community of Ehmed Muftîzade (1933–1993), the Sunni reformist and politician; these women play an active role, and for them, the headscarf is not a symbol of oppression. They are attached to Kurdishness and do not perceive Mestûre’s Kurdish outfit as infringing Islamic rules. At the same time, they consider the politicized Shi’i Islam of the Islamic Republic to be oppressive and to violate Islamic morality (Interview with a community member, Sine, July 2022).

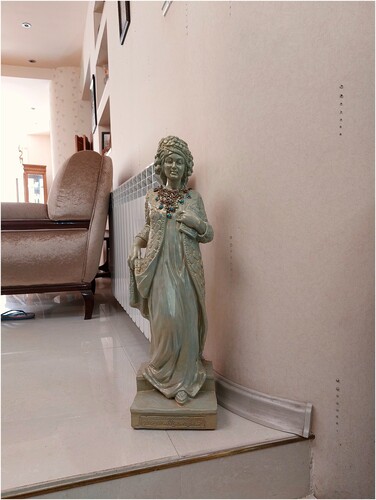

Finally, in a conflict over erecting the statue of Mestûre in Sine, Muslim piety and heritage, which importantly includes works in Farsi, became assets in negotiating the details with the Iranian authorities. Therefore, it is evident that the Kurds also resort to the Muslim and Iranian heritage narrative to achieve their goals, and a line is not always drawn between Kurdish and Iranian identities and heritages. The situation depends on many variables, such as perceived state pressure, the ideology followed, the language and context in which the conversation takes place, the sense of belonging and position of an interlocutor, the location of the conversation, etc. Hence, discussing Mestûre’s heritage moves beyond “the singular readings” (Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017, 3). As stressed by Eta Nehayî, a Kurdish writer who employed Mestûre’s image in one of his short stories (Eta Nehayî Citation2015), she is definitely not a symbol that would be adopted by a mass movement (Interview with the writer, Sine, July 2022). Nevertheless, her image began to be popularized by Ziaoddînî’s sculpture, and even subtly commercialized in the form of the smaller copies produced by him and his assistants that reached private owners. However, as was seen in all the interviews, “feeling” and “being” with Mestûre becomes an intimate imaginative experience of self, which is both singular and collective (Plummer Citation2003; Tolia-Kelly, Waterton, and Watson Citation2017, 3). Yet, this tends to be limited to small-scale activism and artistic and intellectual engagement, even though, as stated by Ziaoddînî, his sculpture was intended to educate the Kurdish masses (Interview with Ziaoddînî, Sine, July 2022). Despite this small-scale commitment, however, memory and imagination have become tools for shaping the many invisible aspects of Kurdish heritage and resistance, such as the self-confidence of female artists to enter the world of men with their message.

Mestûre Erdelan and the Kurdish Dissonant Heritage-Making

Born in 1805 in the Erdalan emirate, Mestûre is a fascinating historical figure, still little known outside Kurdistan. She was born into a family belonging to Qadirî tariqat in a period of prosperity for the emirate and its capital, Sine, ruled by the Kurdish Erdelan family. Despite being a woman, thanks to her father, who recognized her intellectual potential, Mestûre received a thorough education and soon became known in Sine as a talented poet, writing in Persian and Gorani Kurdish. This obviously made her an attractive candidate to be a second wife (1826) of the new ruler, Xosrow Khan (1805–1834), already married to the Qajar Shah’s daughter. Legend has it that Xosrow Khan and Mestûre loved each other deeply, which reverberates in the folk songs, love poems and beautiful elegies written by Mestûre after the premature death of her husband. While in her Persian poetry, she followed strict Arabic scansion (‘arūż) and Persianate literary tropes, in her Kurdish poems she applied simple diction and vivid figurative language, suffused with a personal tone and unique feminine qualities (Ghaderi and Scalbert-Yücel Citation2021, 9).

As a new member of the ruling family, Mestûre was encouraged to write a historical chronicle depicting the history of the Erdelan family and the emirate. In this way, she continued an already existing tradition of recording Kurdish history in Persian, which the Russian historian Evgeniya Vasilyeva described as a “distinctive genre of local dynastic chronicles” (Citation1990, 39). In her comparative study, Vasilyeva suggested that even though Mestûre used information from her predecessors, she hardly ever simply copied from other works. Mestûre verified sources and referred to the oral stories she knew from the Erdelans, proving her knowledge, eloquence and creativity. She wrote an introduction to Islamic law (Shari’at) as religious guidance for women (Bush Citation2022). After Xosrow Khan’s death, his second wife – who had not given birth to an heir – was duly forced into exile. She found shelter in Silêmanî (Baban Emirate), where she later passed away and was buried.

Mestûre’s output began to be discovered in Iranian Kurdistan only in the 1920s, when her poems were, for the first time, collected and published in Persian as Diwan-i Mah Şeref Xanim Kurdistanî Mutakhalis be Mestûre [The Diwan by Mah Şeref Xanim Kurdistanî, Known as Mestûre, 1925] by Yahya Marîfat. This inspired Meryem Erdelan (1893–1967), an Armenian married to a Kurdish diplomat, to establish and name after Mestûre, in 1927, the first school for girls in Sine, of which she also became the director (Interview with Dr Asad Erdalan, Tehran, July 2022). She believed that perfection and knowledge would make people immortal, even beyond one hundred years (Fahri Citation(1352) 1971, 113). These two events can be related to the increasing commitment of Kurdish intellectuals to Kurdish heritage and education visible in the first decades of the twentieth century (Cabi Citation2022). The publication of Mestûre’s historical chronicle by Nasir Azadpûr in 1946 coincided with the establishment of the Kurdistan Republic in Mahabad (1946), which was an important though short-lived Kurdish attempt to establish autonomy from the central Iranian authorities under the auspices of the Soviet Army. Proclaimed in the city of Mahabad, and widely known as Mahabad or the Kurdistan Republic, it was supported by many Kurds from other parts of Kurdistan, including the military forces of Mela Mustafa Barzanî from Iraq. However, after the withdrawal of the Soviet Army, and realizing the imminent danger of a massacre of civilians by the Iranian army, the president, Qazî Muhammad, decided to avoid a war. Barzanî forces left Mahabad and sought refuge in the Soviet Union, and the Iranian army entered Mahabad in December 1946, bringing an end to Kurdish autonomy; its main political leaders were hanged in March 1947. Some members of the Erdelan family, and Azadpûr himself, were actively engaged in Kurdish politics in that period, and the process of promoting Kurdish independence inevitably evoked interest in Kurdish history (Vasilyeva Citation1990, 11). According to Ayin, after the collapse of the Republic, due to persecution and restrictions, it was not easy to publish Mestûre’s chronicle prepared for print as Tarikh-i Al-Akrad (The History of the Kurds). The work was finally published only in 1949 under the title Tarikh-i Ardalan (The History of Erdelan; interview with Ayin, Sine, July 2022). However, the date 1946 was retained as the year of publication, and in this way, the book became symbolically linked to the Mahabad Republic and the Kurdish case, even though its title had to be changed.

The output of Mestûre was not resumed until the end of the century even though in the sixties and seventies she was included in some Farsi publications, for example in an anthology of Iranian poets (Hedayat and Mosaffa Citation(1340) 1961), and in an encyclopedia of famous women in Iran, which was dedicated to Queen Farrah (Fakhri, 95–96). In the 1970s her poetry was recited in a Kurdish program by Muhemmed Siddîq Muftîzade on Radio Tehran. The text of the broadcast was subsequently published by Muhemmed Elî Qeredaxî in Başûr (Citation2021). In 1990, the first translation (Russian) of Mestûre’s chronicle by Vasilyeva was published in the Soviet Union which may have had an impact on the Iraqi Kurds who studied there (Bocheńska Citation2023). The Kurdish Sorani translation by the poet Hejar Mukriyanî followed in 2002, published in Başûr. After the US invasion of Iraq (2003), and political recognition of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq (KRI, 2005), interest in Mestûre was demonstrated freely in that area. Ziaoddînî was invited to erect a sculpture of her in Hewlêr (Erbil) – the capital of KRI. Created in Sine, the four-meter bust of Mestûre made a trip on a truck across the Iran-Iraq border and was unveiled in 2005 during the first international conference on Mestûre arranged with the support of the KRI government (). This event resonated in Rojhelat, evoking even a sense of jealousy, which assisted Ziaoddînî in fulfilling his dream of erecting a sculpture of Mestûre also in Sine.

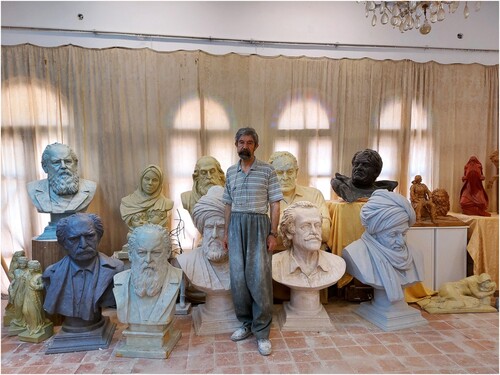

The emerging heritage of Mestûre exposes the Kurdish national idea as dissonant with the centralizing Iranian policy that thwarted Kurdish autonomy. Yet, it also highlights the active role of Kurdish women and their desire for education. Moreover, the two similar representations of Mestûre created by Ziaoddînî, placed on either side of the border, testify to the imaginative political link between Rojhelat and Başûr. This connection was also interestingly exposed in the documentary Road to Kurdistan (2013) by Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri, showcasing Ziaoddînî and his workshop in Sine, and narrating the story of the director’s father traveling from Sine to Silêmanî in order to unearth the family’s Kurdish past and to pay tribute to Mestûre by repeating her arduous trip and visiting her grave in Başûr.

From Literature to Public Sculpture and the Global Brand: Cemal Ehmedî Ayin and Hadî Ziaoddînî

Despite the difficult political and social circumstances in Iranian Kurdistan in the twentieth and the twenty-first century, the publication of Mestûre’s work gradually stirred more interest in her and a desire to make her widely known among the inhabitants of Sine, Rojhelat, Kurdistan, Iran, and even globally. This desire encouraged various uses of heritage. While the performances discussed in this section cannot yet be described as feminist, they firmly established the Kurdish aspect of Mestûre’s heritage and directed attention toward the Kurdish woman, her personality and skills.

The poet, writer and historian, Cemal Ehmedî Ayin, was one of the first to tirelessly dig into private archives and conduct research on Mestûre’s life in both Rojhelat and Başûr. His novel, entitled Barghayi az Tarikh-e Sar be Mohr [The Pages from Untold History, 2005], became one of the most popular points of reference, and Ayin himself became an expert to be consulted by other artists such as Hadî Ziaoddînî. However, what is immediately apparent is that both Ayin and Ziaoddînî’s research sought not only to discover historical facts about Mestûre, but also expressed an intimate relationship rooted in their dreams and mystical visions inspired by a close reading of her poetry, and an emotional connection with the sites associated with her.

Of all the sources, Ayin pointed to Mestûre’s Gorani Kurdish poetry as drawing his attention and leading him to study more about her and nineteenth-century Kurdistan. Interestingly, Ayin presented himself as a Persian language poet and writer, but he stressed the impact of Mestûre’s “strong and passionate feelings” expressed in her Kurdish poetry, which had deeply touched him. He was attracted by the feminine lyrical subject who – for the first time in the history of Kurdish literature – was openly talking about her love for a man (Ghaderi and Scalbert-Yücel Citation2021). However, in describing his novel, Ayin indicated that he imagined her elegies and mourning as referring not only to her personal life but also to the political situation of nineteenth-century Kurdistan:

I focused on her passionate love for Xosrow Khan. I think she talks about her love in a very respectful way, and her elegies for Xosrow Khan were crucial for my writing. It was a time when the two important Kurdish principalities (the Erdelans and the Babans) had collapsed, and Mestûre witnessed that collapse. In my novel, I expanded her mourning for Xosrow Khan, to describe the historical collapse of Kurdish principalities. She focused on historical events, such as the histories of Erdelan and Baban, and she witnessed the fratricide between the Kurds (…). So, in general, it is possible that Mestûre was mourning the collapse of the principalities too. (Interview with Ayin, Sine, July 2022)

Ayin’s interpretation of her poems goes beyond the historically contextualized literary reading, and even “abuses” it to propose another literary vision, where Mestûre is both a loving woman and a stateswoman with Kurdish national consciousness, mourning not only her beloved but also the collapsing Kurdish emirates. Accordingly, in his novel, Ayin dealt interchangeably with both Mestûre’s personal life and the history of the two Kurdish principalities (Ayin Citation2005). Interestingly, he did not offer an academic essay to impose his reading on Mestûre’s poems; instead, he treated this reading as “a possibility,” and located his proposed interpretation in the heritage performed anew, his modern novel. It is important to stress that, during our conversation in Sine, he also frequently cited Mestûre’s poems, because for him, thinking and talking about Mestûre was inseparable from performing her poems. This clearly demonstrates the role of literary imagination in the thinking process. He claimed that Mestûre herself guided him to discover some things about her life. For example, she ordered him in a dream to read her poem from the collection he had prepared, only to learn that the poem was missing from the book, which led him to correct his mistake in a new edition. This shows that in the Kurdish context, the production of knowledge and heritage-making is not only inspired by modern historical research or national ideology, but also by poetry-inspired mystical imagery, which evokes deep emotions, stirring imagination and new forms of creativity.

The same is true of Ziaoddînî, who sought inspiration in Mestûre’s poetry, in her biography, in oral stories and songs performed by elderly people in Sine, and also in Ayin’s novel and many conversations with him. However, he stressed that, for him, the most significant was his own spiritual connection with Mestûre:

Maybe this does not sound very scientific. This is something that I cannot describe in a concrete way. It is beyond the real. I feel spiritual affinity with Mestûre. Very often I have felt her presence. I had a feeling that Mestûre herself came to me and said “Here I am. This is me.” I felt she was talking with me. (Interview with Ziaoddînî, Sine, July 2022)

It is important to note that Ziaoddînî’s workshop is located within the walls of the palace of Xosrow Abad, and his spiritual relationship with Mestûre was evoked by the place, as he could imagine Mestûre living and working in a real architectural and historical setting. Thus, for him, the location seemed to become filled with Mestûre, allowing him intimate contact with his muse, showing that heritage involves both the imaginative and the real process of experiencing it, not just a passive reception of the past (Haldrup and Bærenholdt Citation2015; Smith Citation2006). Yet, unlike Ayin, Ziaoddînî had to convert the words “that speak about soul, and not about size and scale” (Interview with Ziaoddînî, Sine, October 2021, July 2022) into a physical representation. Mestûre’s heritage, including various literary sources, had to be transformed into visual and material form, and thus reimagined and radically re-modeled. What is more, he wished to draw a contrast between the two different periods of Mestûre’s life: her happy aristocratic youth and the later gloomy period of loss, exile and solitude. According to Ziaoddînî, these were two opposite worlds that he had to reconcile in the process of making the sculpture, and to do so he spent time researching human psychology, including human movement in specific states of mind; that knowledge influenced his technical skills. Finally, it was for him to decide the location of the sculpture, and he pointed to the entrance to the alley leading to Xosrow Abad’s palace. He stressed that he was not in favor of a square – where the majority of his other statues are located – because “squares are very noisy, and would not fit Mestûre’s spirit and her inner tranquility” (Interview with Ziaoddînî, Sine, October 2021 and July 2022) ().

However, despite all these efforts, the statue of Mestûre encountered problems from representatives of the regime, who insisted that the dress on her right leg was too tight and could provoke sexual desire among men. The regime, represented in Kurdistan by the oppressive security service, is called they by the people of Sine, who lower their voices when saying it. The negotiations between the artist and them took place via a chain of people who helped to convince the Iranian authorities to give their consent. But also, Ziaoddînî did not intend to create an anti-Islamic sculpture and was open to adjusting the dress to the morality code proposed by the Iranian authorities, which led to a positive outcome. It enabled the statue to enter the public sphere as the statue of an individual woman, and thus – as discussed below – invited new imagination and performance of heritage. What is also significant is that in the process of making the sculpture, Ziaoddînî enriched his spiritual affinity with Mestûre through psychological research, and thus merged his experience, originating in the literary and mystical imagination, with modern knowledge. This clearly shows that the latter may not necessarily replace the former, but that they can perfectly co-exist in the Kurdish context. What is more, Ziaoddînî produced and sold more than a thousand small (fifty-centimeter) copies of the statue, which became popular in Kurdish houses, bookstores and museums in Rojhelat and Başûr, reaching even Europe; they became a symbol, for many as a souvenir but also as a portable object with a moral connection with Mestûre and Kurdish heritage. A carpenter from Sine said that, by having the statue at home, he wished to introduce a symbol of a human and a liberated woman, and that everyone who visits his house can see it (). He added:

Wasn’t Napoleon a criminal? He was a criminal, but in France, they erected grand monuments to commemorate him (…). And Napoleon became a global thing, they exposed his human features and transformed him into a brand. So why cannot we turn Mestûre into a brand, a brand that encompasses humanness? Two hundred years ago she was an educated, thoughtful woman, and today, when reading her poems, we can find such tenderness in them that it proves her humanness and makes her an example for all people. (Interview with the carpenter, Sine July 2022)

By referring to “branding,” the carpenter both points to the pitfalls of the universal heritage produced by the Western world (Smith Citation2006), and also appeals to it, by offering a heritage that can serve the purpose of promoting not just Kurds but human values. Interestingly, his point of reference is not Iranian heritage but world heritage, and the universal values of “all people.” In his words, it seems that he intends to rebrand locally recognized Kurdish heritage to become a universally recognized symbol, thereby challenging the Iranian policy of minoritizing the Kurds and their culture which is visible in other Kurdish heritage practices (Bocheńska and Ghaderi Citation2023).

From Intimacy to Public Protest: Mestûre as a Woman Who “Did Something Interesting in Her Life”

For young women who today struggle for their rights as Kurdish women, Mestûre Erdelan, and especially her statue by Ziaoddînî, has become an important point of reference. Her sculpture increased the public visibility of not just a woman, but of a talented woman, who – as stressed by many of them – “did something interesting in her life.”

Soraya, a photographer from Sine, underlined that in a country like Iran, where the rights of women are in the hands of men, having such a sculpture in the city center “is maybe the only source of satisfaction” (Interview with Soraya, Sine, July 2022). Many of those interviewed rejoiced in the fact that Mestûre is not wearing a hijab but Kurdish clothes and kofi because – as they stressed – their struggle in Iran is intersectional and includes fighting simultaneously for the rights of Kurds and women. They stated that she must be holding a book in her hand, pointing out that Kurdish women have the talent and the mental capacity to develop themselves, which has been often denied to them by society. Şîlan, the artist from Bane, highlighted the fact that the urban space in Iran has been dominated by sculptures of male subjects and that creating the statue of Mestûre required much courage and strength in breaking with that norm (Interview with Şîlan, Bane, July 2022). Rana, another photographer from Sine, emphasized that she likes the sculpture because it symbolizes the fact “that we women have existed.” She added:

I visited the Xosrow Khan palace (…). These were the rooms filled with sunlight where she used to sit, think and write. And this offers me a very nice feeling to the extent that I talk with this sculpture. I come to her and I say ‘Mestûre, I came to you’. This offers me a really lovely feeling which makes her alive. (Interview with Rana, Sine, July 2022)

Rana’s very intimate relationship with the sculpture and the site corresponds with the experience of heritage described by Ziaoddînî. Yet, this time it was not just the mansion but also the sculpture by Ziaoddînî that inspired Rana to imagine such a close emotional bond with Mestûre. This reflects the moment of an interplay; the heritage is reused by both the new representation and the new practice and performance which such representation invites (Waterton and Watson Citation2015). Contrary to Ziaoddînî, Rana persives Mestûre not as a muse of an artist but as an active figure, who can empower contemporary women. She also referred to Mestûre’s work on jurisprudence and said:

At that time women did not know much about their rights, but she took care of women. What especially makes this figure inspiring to me is that she was able to find her way and she followed the interests that other women of her time were not thinking about. (Interview with Rana, Sine, July 2022)

Hence, it appears that the work on Islamic law is associated with women’s rights, which definitely “abuses” the historical facts. Yet, this mistake is invited by Rana’s imagination and her own strong desire to find her way, follow her interests and assist other women to do so. Evidently, the heritage of Mestûre merges with the young women’s social and political desires and struggles ().

Çinar, a writer from Sine, stressed that what she found significant was that Ziaoddînî located the sculpture of Mestûre not in the impoverished downtown or outskirts of Sine – where previously a sculpture of “mother” was erected – but in its very heart, the more elegant upper part, in the vicinity of the Xosrow Abad and the Awyer mountain, which are visited by many people. Even though Ziaoddînî chose this place mainly because of its historical importance and tranquility, for Çinar his decision elevated the role of Mestûre as a woman in Kurdish society. Moreover, she linked it to her struggle to remodel the spatial division in her Kurdish home, where during family meetings the better space was usually occupied by the men. For a few years, she struggled with the men to change their point of view and make space for women next to them, as well as insisting that the women take their seats next to the male family members, in which she finally succeeded. This indicates that the public urban reality and the private space of home interpenetrate in Rojhelati women’s imagination, and cannot be discussed as entirely separate. Çinar added that, in recent years, she had been inspired by women guerillas from Rojava, but “Mestûre was from here, from Sine and therefore she is so important to us,” highlighting the importance of the local context with reference to greater Kurdistan, not Iran. She believed that the figure of Mestûre assisted women in entering the world of men and in breaking with its order. According to her, the process of “entering the men’s world” possesses both a spatial and moral characteristic: women are entering the spaces intended for men, but they also undertake new professional activities (photography, writing) which were until recently fully dominated by men (Interview with Çinar, Sine, July 2022). What is more, it is imagined as a long-term endeavor, designed to reach out to future generations also (Haldrup and Bærenholdt Citation2015). Mestûre, as a woman who gained her skills in the male-dominated world of the nineteenth century, and whose sculpture entered the male-dominated public space of the modern city, stirs young women’s imagination, courage and self-confidence to perform many even more risky acts of dissent. Çinar wore colorful clothes and vivid make-up when going out, and even when being interrogated by Etla’at, to manifest her dissent from the Iranian regime’s policy of gender discrimination. By asking the Etla’at representatives about the sense of the many limits imposed on women in Iran, she managed to momentarily transform the oppressive space of the security office into a site of dissent and civic debate. She stated that the source of her courage was Mestûre “who was brave,” which evidently activated her moral imagination and sense of virtue (Interview with Çinar, July 2022). When, after the murder of Jîna Emînî, the women activists of Sine asked permission to organize a gathering next to Mestûre’s sculpture, only to learn they were not allowed to do so, Çinar wrote a short story, (Hêrîşî Mişkekan/The Attack of Rats), in which she transformed the leisure zone into a site of protest (Online communication with Çinar, March 2023). Hence, with the help of literary fiction, Ziaoddînî’s image of Mestûre became intertwined with the image of Jîna, her tragic death and the 2022 protests and thus – even though only as part of literary fiction and on a small scale – gained a new symbolic life.

Nevertheless, despite widespread admiration for Ziaoddînî’s statue of Mestûre, some women expressed criticism, pointing to her downcast eyes as a compromise with the regime and the conservative part of Kurdish society, or to the fact that many more women of non-aristocratic background also deserve commemoration, and that this should be performed by women and not only by male artists. However, these criticisms do not detract from the social meaning of the sculpture, but rather reveal the increasing radicalization of women in Iran. Even though the new postulates of women are quite far from Ziaoddînî’s vision of the noble Kurdish muse, they are all the result of the complex process of heritage meaning-making in very precarious circumstances.

Conclusion

Mestûre’s legacy began to be discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century and went through various transformations. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, recreated in a few literary works, Mestûre became a muse for male Kurdish artists, such as Ayin and Ziaoddînî. However, by entering the Iranian-Kurdish public space as a statue, Mestûre acquired a new feminist meaning. Her representation by Ziaoddînî became an inspiration to struggle for more rights for women and their greater visibility as creators and in the public sphere. Young female artists imagine Mestûre as a woman who managed to enter the world of men, discover herself, and do something interesting in her life.

In this paper, the evolving representation and interpretation of Mestûre and the different uses of her heritage have been presented as empowering Kurdish identity and women’s self-confidence. The analysis contributes to studies on heritage in Iran which, until now, largely ignored the cultures of ethnic groups. It draws attention to the heritage-making of minoritized communities and specifically explores some of the imaginative mechanisms of women’s empowerment through their heritage. Addressing the stereotypical image of Kurdish culture, which is often reduced to folklore, the focus was on a historical figure, classical and modern literature, art, and the interplay between them. Until now, the encounters with monuments representing historical figures in Iran have been mainly associated with state policy (Grigor Citation2005). Women’s encounters with Mestûre stir their moral imagination and self-confidence, showing that the connection to a historical personage may be an example of a heritage from below.

In contrast with the prioritization of the pre-Islamic and folkloric representation of women in Kurdish studies, a personage rooted in the Sunni Kurdish past is presented, in order to demonstrate the paradoxes in the modern heritage practices performed by Kurdish women in the Islamic Republic, such as combining Mestûre’s Muslim piety with anti-hijab protests and women rights. The study tracked the performance of the complex multi-layered heritage, consisting of citing literary sources, experiencing and expressing a close emotional and spiritual bond with Mestûre, conducting research, writing literature and creating art, visiting the site of the statue and placing its smaller versions at home to demonstrate attachment to Kurdish values and women’s liberation. These practices reveal transformations and intricacies such as changing a muse into a symbol of liberated woman, connecting mystical experience with research, or the urban space with the transformation of family hierarchies; they expose the vibrant and empowering aspects of moral imagination. Importantly, performing Mestûre’s heritage consists also of acts of dissent that are not just imaginary but become enacted in the real world, such as Çinar’s performances in the Etla’at office. Such acts are designed to undermine both the conservative norms in Kurdish society and the discriminatory policy of the Islamic Republic. By imagining Mestûre and her statue, female artists and activists enter the world of men, in both a spatial and metaphorical sense.

Moreover, by recognizing Mestûre’s attachment to Islam and the Persian language, her heritage is open to other readings also. She is an important symbol among the Kurdish Muslim women, whose Muslim piety is closely intertwined with Kurdish identity. What is more, the statue was recently recognized as “Iranian national heritage,” which may indicate the Iranian authorities’ intention to take control of the heritage discourse produced in recent decades by the Kurds in the neighboring Kurdish areas of Rojhelat and Başûr, silencing it by subsuming it under the banner of “Iranian heritage.” Therefore, modern Kurdish heritage-making includes the intentional “rebranding” of their heritage from “local” to “national” and “universal,” exhibiting human values and women’s liberation to draw the attention of the outside world and assist them in establishing independent links beyond their homeland. The charming statue of Mestûre points to the power of imagination and art, shedding light on the creativity behind the recent protests, which obviously did not come out of nowhere. In a reality where negotiations are still too often replaced by force, and the hope for change by precarity, imagination becomes not just a refuge but also a powerful political tool.

Acknowledgements

The authors express deep gratitude to all people in Rojhelat who took part in the research! They thank Farangis Ghaderi, Persheng Sadegh-Vaziri, Houzan Mahmoud and Andrew Bush for many fascinating discussions about the poet. They are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abaza, Mona. 2023. “The Vanished Representations of Gender and Graffiti After 2011.” In Routledge Handbook on Women in the Middle East, edited by Suad Joseph and Zeina Zaatari, 407–429. London: Routledge.

- Abbadi, Fatma. 2020. Embroidery in the Age of Corona [Online Lecture]. Crafting Conversations No.3. Institute of Islamic Studies. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ni2_UQpfpEw&t=3906s.

- Alakom, Rohat. 2013. Di Folklora Kurdî de Serdestiyeke Jinan. Istanbul: Avesta.

- Amini, Niloofar. 2020. “The Aesthetic Resistance of Iranian Architects and Artists During the Late Pahlavi Era.” Studies in History and Theory of Architecture 8:197–212.

- Ayin, Cemal E. 2005. Barghayi az Tarikh-e Sar be Mohr [The pages from untold history]. Hewlêr: Aras.

- Bocheńska, Joanna. 2023. “Obituary. Evegeniya Illyinichna Vasilyeva (1935–2023).” Kurdish Studies Journal 1 (1): 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1163/29502292-00101002.

- Bocheńska, Joanna, and Farangis Ghaderi. 2023. “‘Gan qey bedenî yeno çi mana’ (What the Soul Means for the Body): Collecting and Archiving Kurdish Folklore as a Strategy for Language Revitalization and Indigenous Knowledge Production.” Folklore 134 (3): 344–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2023.2205777.

- Bush, Andrew J. 2022. “Masturah Ardalan’s Fiqh for Women in Kurdistan.” Paper Presented at the ASPS Virtual Event Series IX: Iranian Heritage and the Today’s World, Part I, Law, State and Social Order, May 26. https://www.persianatesocieties.org/event/asps-virtual-event-series-ix-iranian-heritage-and-todays-world-part-i-law-state-and-social-order/.

- Butler, Beverley. 2006. “Heritage and the Present Past.” In The Handbook of Material Culture, edited by Chris Tilley, Webb Keane, Susan Keuchler, Mike Rowlands, and Patricia Spyer, 463–479. London: Sage Publications.

- Cabi, Marouf. 2021. “The Duality of ‘Official’ and ‘Local’ in Modern Iran: Historical and Intellectual Foundations.” Middle Eastern Studies 57 (5): 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2021.1891892.

- Cabi, Marouf. 2022. The Formation of Modern Kurdish Society in Iran. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Caglayan, Handan. 2012. “From Kawa the Blacksmith to Ishtar the Goddess: Gender Constructions in Ideological-Political Discourses of the Kurdish Movement in Post-1980 Turkey (Translated by Can Evren).” European Journal of Turkish Studies 14:1–28.

- Cities of Music. 2019. https://citiesofmusic.net/city/sanandaj/.

- Deniz, Dilşa. 2024. Shâhmaran. The Neolithic Eternal Mother, Love and the Kurds. London and New York: Lexington Books.

- Fahri, Q. A. V. (1352) 1971. Karname-ye Zanan-e Mashur-e Iran Qabl Az Eslam Asr-e Hazer. Tehran.

- Fallah, S. 2019. “Kurdish Women’s Challenges and Struggles at the Time of Conflict and Post-Conflict: An Exploratory Research Study on Status of Kurdish Women in Iran.” In Women in Conflict and Post-Conflict Situations: An Anthology of Cases from Iraq, Iran, Syria and Other Countries, edited by S. Behnaz Hosseini, 53–94. Zürich: Lit Verlag.

- Fowler, Peter. 1992. The Past in Contemporary Society: Then, Now. London: Routledge.

- Ghaderi, Farangis. 2024. “Jin, Jiyan Azadi and the Historical Erasure of Kurds.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 55 (4): 718–723. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002074382300137X.

- Ghaderi, Farangis, and Clemence Scalbert-Yücel. 2021. “Unsung Poets of Kurdistan: A Reflection on Women’s Voices in Kurdish Poetry.” In Women’s Voices from Kurdistan. A Selection of Kurdish Poetry, edited by Farangis Ghaderi, Clémence Scalbert Yücel, and Yaser Hassan Ali, 7–17. London: Transnational Press.

- Ghaeli, Zainab, Mehrnoosh Shafiei Sararoudi, and ShaabanAli Ghorbani. (1399) 2020. “Barrasi-ye Mozu’i ve Mohtawai-ye Mojasamehay-e Zan dar Shahre Tehran” [Thematic and content study of female statues in Tehran]. Nashriye-ye Honarhay-e Ziba-Honarhay-e Tajasomi [The Fine and Visual Arts Journal] 25 (1): 109–124.

- Grigor, Talinn. 2004. “Recultivating ‘Good Taste’: The Early Pahlavi Modernists and Their Society for National Heritage.” Iranian Studies 37 (1): 17–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/0021086042000232929.

- Grigor, Talinn. 2005. “Cultivat(ing) Modernities: The Society for National Heritage, Political Propaganda and Public Architecture in Twentieth Century Iran.” PhD, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Haldrup, Michael, and Jørgen O. Bærenholdt. 2015. “Heritage as Performance.” In The Palgrave Handbook of the Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, 52–68. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hedayat, Reza Q. Kh, and Mazaher Mosaffa. (1340) 1961. Majma’ol Fosaha [Anthology of poets]. Tehran: Amir Kabir.

- Hodjat, Mehdi. 1995. “Cultural Heritage in Iran: Policies for an Islamic Country.” PhD, The King’s Manor University of York.

- Jones, Tod, Ali Mozaffari, and James M. Jasper. 2017. “Heritage Contests: What Can We Learn from Social Movements?” Heritage and Society 10 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2018.1428445.

- Käser, Isabel. 2021. The Kurdish Women Freedom Movements. Gender, Body Politics and Militant Femininities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maghsudeh, Manijeh. 2023. “Porkhani and Ihsani: Women Healers in the Turkmen Community in Iran.” In Ethnic Religious Minorities in Iran, edited by S. Behnaz Hosseini, 95–108. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mahdizadeh, Sara. 2021. “Shiraz’s Heritage Gardens During the Political Turmoil in Twentieth-Century Iran.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 27 (9): 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1883717.

- McDowall, David. 2004. The Modern History of the Kurds. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Mozaffari, Ali. 2013. “Islamism and Iran’s Islamic Period Museum.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (3): 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.652145.

- Mozaffari, Ali. 2015. “The Heritage ‘NGO’: A Case Study on the Role of Grassroots Heritage Societies in Iran and Their Perception of Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (9): 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1028961.

- Muftîzade, Muhemmed Siddîq. 2021. Wêje û Wêjewanan. Edited by Muhemmed ‘Elî Qaradaxî. Soran: Soran University.

- Nehayî, Eta. 2015. Ew balinde-y birîndar e ke min im [The wounded bird who is me]. Bane: Mang Publications.

- Nussbaum, Martha. 1990. Love’s Knowledge. Essays on Philosophy and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Olko, Justyna. 2018. “Acting in and Through the Heritage Language: Collaborative Strategies for Research, Empowerment, and Reconnecting with the Past.” Collaborative Anthropologies 11 (1): 48–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/cla.2018.0001.

- Pezeshki, Fereshteh, Masood Khodadadi, and Moslem Bagheri. 2023. “Investigating Community Support for Sustainable Tourism Development in Small Heritage Sites in Iran: A Grounded Theory Approach.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 29 (8): 773–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2023.2220316.

- Plummer, Ken. 2003. Intimate Citizenship. Private Decision and Public Dialogues. Seattle: Washington University Press.

- Reading, Anna. 2015. “Making Feminist Heritage Work: Gender and Heritage.” In The Palgrave Handbook of The Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, 397–413. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sheyholislami, Jaffer. 2023. “Linguistic Human Rights in Kurdistan.” In The Handbook of Linguistic Human Rights, edited by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Robert Philipson, 357–371. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

- Shisheliakina, Alena. 2022. “Being a Woman and Being a Tatar. Intersectional Perspectives on Identity and Tradition in the Post-Soviet Context.” PhD, University of Tartu Press, Tartu.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Linda T. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books.

- Soleimani, Kamal, and Ahmad Mohammadpour. 2019. “Can Non-Persian Speaks? The Sovereign’s Narration of ‘Iranian Identity’.” Ethnicities 19 (5): 925–947. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796819853059.

- Steiner, Rudolf. 2000. Filozofia Wolności (Die Philosophie der Freiheit). Polish translation by Jerzy Prokopiuk. Warszawa: Spectrum.

- Tehran Times. 2022. “Statue of Kurdish Writer Mastureh Ardalan Awarded National Heritage Status.” February 4, 2022. https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/469798/Statue-of-Kurdish-writer-Mastureh-Ardalan-awarded-national-heritage.

- Tolia-Kelly, Divya P., Emma Waterton, and Steve Watson. 2017. “Introduction: Heritage, Affect and Emotion.” In Heritage, Affect and Emotion: Politics, Practices and Infrastructure, edited by Divya P. Tolia-Kelly, Emma Waterton, and Steve Watson, 1–11. New York: Routledge.

- Tunbridge, John E., and Gregory J. Ashworth. 1996. Dissonant Heritage. The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. West Sussex: Wiley.

- Vali, Abbas. 2020. The Forgotten Years of Kurdish Nationalism in Iran. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vasilyeva, Evgeniya I. 1990. “Vvedeniye” [Introduction]. In Mah Şeref Xanim Kurdistanî. Khronika Doma Ardalan, edited by Yevgeniya Ilinichna, 8–41. Moskva: Nauka.

- Waterton, Emma, and Steve Watson. 2015. “Heritage as a Focus of Research: Past, Present and New Directions.” In The Palgrave Handbook of The Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, 1–14. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Werhane, Patricia H., and Brian Moriarty. 2009. “Moral Imagination and Management Decision Making.” Bridge Paper, 2-16.

- Wu, Zongije, and Song Hou. 2015. “Heritage and Discourse.” In The Palgrave Handbook of The Contemporary Heritage Research, edited by Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, 37–51. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.