ABSTRACT

Unbalanced or absent Indigenous representation in interpretive materials at government administered heritage sites in settler-colonial contexts can create contention and perpetuate a misinformed or one-dimensional visitor experience and historical narrative. This research therefore examines representation in interpretive materials accessible in 2019 at heritage sites with Indigenous ancestral connections in settler-colonial contexts. This study uses 10 U.S. case study heritage sites and two supplementary sites in Washington, Idaho, and Hawai‘i. Researcers utilized participant observation and systematic photography during two 2019 research phases to document interpretive materials. Quantification generated 731 analytic units which were subsequently assessed for the presence of inductively and deductively generated codes. The assembled empirical results illustrate three overarching themes: (1) controlled historical narrative; (2) absence of shared authority; and (3) challenges in representing and/or integrating different ways of knowing. This research contributes to heritage studies and practical heritage site management in two ways: (1) offering a timely multi-sited and multicultural sample of settler-colonial heritage site interpretive materials comparable to other sites; and (2) illustrating empirical trends in interpretive materials that privilege settlers over Indigenous peoples. This research suggests that future interpretation could benefit from a more balanced multivocal approach that recognizes ancestral and contemporary Indigenous homelands and the complexity of Indigenous-settler interactions.

1. Introduction

Through public interpretation and programming, heritage site interpretation often seeks to tell a more balanced history of places and the experiences of peoples who once dwelled there. Heritage organizations and government entities with heritage mandates aim to achieve this in part through the development of cultural and visitor centers, museum exhibits, reconstructed and preserved historic structures, monuments to the past, and public art. At heritage sites administered by U.S., federal, state, and local governments, these spaces hold formal mandates – often embodied in law, policy, and regulation – to maintain contemporary relationships with culturally-affiliated Tribal Nations and a diverse range of additional stakeholders (e.g., NHPA Citation2016; NEPA Citation2021; AIRFA Citation1994; NAGPRA Citation2006); however, in spite of these obligations, U.S. interpretive materials, such as visitor center exhibits, trails with thematic wayside signs, maps, and brochures, often construct the past largely through the perspectives of Euro-Americans, while excluding or marginalizing the perspectives and experiences of Indigenous peoples (Zerubavel Citation1995, 11).Footnote1 Heritage interpretation materials can therefore manifest foundational contradictions and hold unrealized potential. Critically reevaluated and retooled, such interpretation holds not only the potential but the mandate to pivot, turning to more inclusive visions and subaltern voices while acknowledging and disseminating difficult histories (Little and Shackel Citation2014, 128).

Efforts to reevaluate public interpretation of the past have simmered quietly for decades as part of broader revisionary and decolonizing efforts in settler-colonial contexts like the U.S.; however, changes to interpretive materials and programs often depend on resources, priorities, personalities, number of visitors and their demographics, among other factors (e.g., Barcalow and Spoon Citation2018; Edwards Citation1994; Spoon and Arnold Citation2012; Wahl, Lee, and Jamal Citation2020). In recent years, this reevaluation has accelerated amidst a surge in social justice protests following the murder of George Floyd and the emerging Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the United States and globally. This reevaluation has been further encouraged by the Land Back movement in the U.S. which supports Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination by enabling Indigenous ancestral and treaty lands to be returned to Indigenous communities. For example, there is contention over Mount Rushmore National Memorial located within the Black Hills National Forest, which is part of broader landscapes that are spiritually important to multiple Tribal Nations, and is a landmark imbued with colonial symbolism through its monumental depiction of U.S. presidents (Bearfoot Citation2022; Ishisaka Citation2022; Kaur Citation2020; NDN Collective Citation2021; Treuer Citation2021). Public awareness is therefore increasing of heritage monuments in settler-colonial contexts that celebrate settlers who participated in the displacement of Indigenous peoples while at the same time lacking representation or misrepresenting Indigenous peoples in the past and present. Attention in the media and in protests has led to the widespread dismantling, destruction, and removal of these types of monuments (Aguilera Citation2020; BBC Citation2020; Grovier Citation2020; Guy Citation2020; Morris Citation2020; Parveen et al. Citation2020; Philimon, Hughes, and della Cava Citation2020; Restuccia and Kiernan Citation2020; Schultz Citation2020). Globally, museum and heritage associations have issued statements committing to decolonize the information shared with the public by providing more equitable representation of Black, Indigenous, and Peoples of Color (BIPOC) (American Institute for Conservation and Foundation for Advancement in Conservation Citation2022; Association of Independent Museums Citation2021; Oregon Museum Associations Citation2020; English Heritage Citation2020; Museum Association Citation2020). Further, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) adds that the process of decolonization needs to recognize past and present power dynamics, such as colonialism, enslavement, and civil rights (Stevens Citation2020). Further, scholars have focused critical attention on the politics and meaning of colonial memorialization which is common at settler-colonial heritage sites (Burch-Brown Citation2020; Cribbs and Rim Citation2019; Frank and Ristic Citation2020; McGonigle Leyh Citation2020; Wahl, Lee, and Jamal Citation2020; Zhang Citation2020). This momentum appears poised to continue and spread, drawing greater attention to externally-administered heritage sites and their interpretation of contested histories on previously colonized lands or what we refer to as settler-colonial contexts.

In spite of a growing number of U.S. state and federal legal mandates for agencies to engage with Indigenous peoples, interpretive materials at government administered heritage sites generally continue to portray history from a predominantly Euro-American perspective (Bright et al. Citation2021; Wahl, Lee, and Jamal Citation2020). This reflects not only the inherent biases of agency staff and consultants, but also institutional and legal factors operating at various government levels. Among these, the original establishing legislation of federal and state parks and sites defines the mission of each site’s future management and interpretation – including outmoded legislation from decades prior. For example, the public purpose of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (FOVA), established by an act of U.S. Congress in 1961 (75 Stat.196), states that the intention of Congress in creating the park, and therefore the mandate of the National Park Service, is to preserve and interpret three aspects of the site: (1) the activities of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the nineteenth century, (2) the settlement of the Oregon Territory, and (3) the establishment of the U.S. Army’s Vancouver Barracks (United States Department of the Interior Citation2008, 6). Yet, the lands now occupied by this site were a place where Tribal Nations lived, traveled, traded, and cared for the land since time immemorial to the contemporary moment, maintaining their place-based connections (Deur Citation2012). Although Indigenous peoples’ presence at FOVA is included in the site’s interpretation, it is not part of the park’s legally mandated mission, and this has impeded the development of interpretation on Indigenous themes. For this reason, at heritage sites in settler-colonial contexts such as Fort Vancouver, and analogous to other venues across the U.S. and abroad, a change in interpretive content may require changes at the legislative level – effectively redefining the fundamental purpose of the heritage site to include these Indigenous ancestral and contemporary relationships and the dynamic interactions and exchanges between Indigenous peoples and settler populations.

This paper focuses on Indigenous representation in interpretive materials at heritage sites with differing portrayals of history and memory. We define heritage sites as places designated for protection and public engagement and learning because of their cultural or historical value, serving as places of memory and knowledge (Baird Citation2017, 4; Jackson Citation2016, 24; Little and Shackel Citation2014, 39). Heritage site interpretive materials that explore a diversity of experiences, cultural meanings, and actions occurring within contexts of unequal power over time (Roseberry Citation1994, 36–44) can assist in identifying root causes that created unbalanced or absent representation in heritage site interpretation with contested and colonial histories (Di Leonardo Citation1993, 78; Farmer Citation2004; Leng and Chen Citation2021). Our approach thus examines some of the processes that created the content and underpinning values and perspectives expressed in certain heritage site interpretive materials within settler-colonial contexts.

We focused on 10 heritage sites and two supplementary sites in Hawai‘i and Cascadia or Pacific Northwest, U.S., as case studies. We utilized systematic participant observation and photography of site interpretive materials and programmatic content. In particular, we used the content of heritage interpretive materials of indoor and outdoor exhibits, trails and overlooks with thematic wayside signs, maps, and brochures, as the unit of analysis. Quantification of these materials yielded 731 interpretive units. Using descriptive statistics, we calculated the frequency of codes developed inductively from the photographs and participant observation and deductively during the iterative analysis process. We generated the following three primary themes from our assembled quantitative results: (1) controlled historical narrative, (2) absence of shared authority, and (3) challenges in representing and/or integrating multiple ways of knowing. These findings have implications for more inclusive and equitable representation at settler-colonial heritage sites in the U.S. and more generally.

Our research highlights how power shapes representation at certain heritage sites in settler-colonial contexts resulting in what stories are being told, who is telling them, and how they are conveyed. This is accomplished through a multi-sited quantitative study of U.S. government administered heritage sites that include Indigenous and settler histories. Previous research on heritage interpretation typically focused on materials and technical processes; however, there is now greater attention being paid to understanding the meanings of heritage spaces and the lived experiences of different peoples at those sites, recognizing the roles of power and history in shaping narratives (Bright et al. Citation2021; Wahl, Lee, and Jamal Citation2020; Waterton and Watson Citation2013, 558; Winter Citation2013, 539). Indeed, Kryder-Reid argues that the field of heritage management needs to recognize multiple ways of knowing, especially the knowledge of those communities historically marginalized in interpretation and in other domains (Citation2018, 691). Kølvraa and Knudsen add that although colonial history is part of European and American heritage, there is a need to share different experiences of colonialism as well as investigate differences in past and present relationships with heritage sites in settler-colonialism (Citation2020, 2). Our research contributes to this effort by contextualizing Indigenous representation at heritage sites, illustrating privileged stories and voices, (i.e., settlers) and the resulting obfuscating of others (i.e., Indigenous peoples). Our results are relevant not only in the U.S. but to other analogous settler-colonial contexts including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

2. Heritage and History in Interpretive Materials

Certain understandings of heritage and history frame Indigenous representations in interpretive materials at heritage sites as well as the underlying historical narratives that led to those representations. History is a representation of peoples’ experiences of the past. Most historical records and accounts do not tell what precisely happened, but how the recorder of the event experienced it (Trouillot Citation1995). Trouillot explains that parts of the past are often silenced or forgotten, which can occur in fact and archive creation, narrative formation, and the “making of history in the final instance” (Citation1995, 26). In North America, commemorations of the past often exclude the experiences of Indigenous peoples, with historical representations framed through Euro-American perspectives (Zerubavel Citation1995, 11; Runnels et al. Citation2017). Further, Smith explains that in contexts of settler-colonialism dominant settler groups often use certain versions of history to marginalize and “other” Indigenous and less-privileged peoples (Citation2010, 33–34). Indeed, more marginalized populations in settler-colonial contexts often struggle with such representation because they are inhibited by those holding authority, which in this case is U.S. state and federal government administered heritage sites.

Heritage is not history, but a reflection of societal values and a producer of meaning (Baird Citation2017, 10; Jackson Citation2016). Societies often construct heritage based on what is deemed important to them (Hoelscher Citation2011, 203). The objects and places that display heritage serve to produce meaning and inform understanding of the past and present (Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Citation2006; Jackson Citation2016, 24; Kølvraa and Timm Knudsen Citation2020). Baird explains that heritage sites, which often include broader landscapes beyond their administrative boundaries, broadly serve as places of memory and belonging that hold knowledge as well as locations that negotiate community and national identity. Further, she states that heritage sites may also be places of conflict, death, loss, displacement, and other traumas that render discussions or interpretation of heritage difficult for certain people (Citation2017, 4). Importantly, heritage sites can destructively construct misconceptions of common memory (Young Citation1993, 6) when there is a lack of representation resulting in dissonance and disagreement over heritage places (Hanson et al. Citation2022; Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018; Little and Shackel Citation2014, 40; Liu, Dupre, and Jin Citation2021, 451). Little and Shackel explain that although difficult, heritage work can create a story of the past that recognizes and teaches difficult histories when approached with sensitivity to these concerns (Citation2014, 128).

The heritage sites in this study and analogous settler-colonial contexts utilize interpretation as a key method for communicating with visitors about the past and its relationships to the present through a variety of materials, such as thematic indoor and outdoor exhibits and displays, trails and overlooks with wayside signs, maps, brochures, and videos. Interpretation is a process of sharing with visitors the wonder, beauty, inspiration, understanding, appreciation, and meaning of places as well as the cultures and histories of places (Benton Citation2011, 7; National Park Service Citation2007, 7; Tilden Citation2009, 25; Uzzell Citation1998). In general, the influence of power on knowledge has impacted interpretive narratives and how these narratives are situated in site-specific interpretive materials developed over time. The poor ethics of past and present government agencies and museums in settler-colonial contexts often marginalized, excluded, and disenfranchised Indigenous populations, which in turn created erasure or unbalanced narratives that privilege settlers over Indigenous peoples (Onciul Citation2015; Smith Citation2006, 281; Zerubavel Citation1995). Indeed, some current Indigenous representation in interpretive materials on ancestral lands situated on externally administered heritage sites only occurred after those with authority invited them to do so (Smith Citation2006, 281). Research also indicates that Euro-American perspectives often frame representations of the past, and heritage site staff and exhibit designers often select information to present based on their interests and desired messages (Ballantyne and Hughes Citation2003, 16; Zerubavel Citation1995, 11). These insights on how power shapes representation at heritage sites therefore assists in the framing of the research that follows.

3. Research Design and Methodology

The purpose of this study was to understand Indigenous representation in interpretive materials available in 2019 at the time of study from heritage sites in settler-colonial contexts. We examined how heritage sites interpret the past and represent the diverse peoples connected to them, especially Indigenous populations. This study was developed in collaboration with the U.S. National Park Service at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and with culturally and historically affiliated Tribal Nations, Canadian First Nations, and Native Hawaiian organizations. We used two primary research methods: participant observation and systematic photography of interpretive materials.Footnote2 Data collection occurred in two June/July and August 2019 research phases. The sample included ten heritage sites and two supplementary sites in Washington, Idaho, and Hawai‘i, USA. We selected the following case study sites: Fort Simcoe Historical State Park, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Fort Spokane in Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, Fort Nisqually Living History Museum in Point Defiance Park, Pu'uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, The Volcano Art Center in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park and Niaulani Campus Administrative Office & Gallery in Volcano Village, Spokane House Interpretive Center in Riverside State Park, Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park,Footnote3 Pu'ukoholā Heiau National Historic Site, and Sacajawea Historical State Park and Interpretive Center. The two supplementary sites were Whitman Mission National Historic Site and Kamakahonu National Historic Landmark. The criteria for case study selection included: accessibility during two research trips, Indigenous connections, the availability of interpretation, use by diverse communities, and administration by non-tribal governments.

At each site, we conducted participant observation and systematic photography of interpretive materials (Schensul and LeCompte Citation2013). We used a “walkabout” approach of participant observation to document interpretive materials, programming, and visitor activities using field notes. We also systemically photo-documented interpretive materials, such as signage, interpretive displays, and other important features of the heritage sites. This process created a full description of each space and its use with photographs and notes (Schensul and LeCompte Citation2013). More specifically, we photographed all signage and displays relating to culture and history as well as some signage on other information. If available during our visits, we participated in activities occurring at the sites, such as cultural demonstrations or tours and collected all interpretive and promotional materials available to visitors. In this process, we not only observed the physicality of the spaces, but also what interpretive content is included at sites and how information – especially contested stories – about the past is presented and communicated to site visitors. We took more than 3,600 photographs which made up a total of 731 interpretive units for analysis. Interpretive units were identified as units of interpretation that could stand alone, such as individual interpretive panels, interpretation confined within a display case, distinctive pages of guidebooks, art installations or displays, narrative content within brochures and maps, individual wayside panels or signs, and other similar distinguishable interpretive materials. We used inductive content analysis to identify the frequency (or presence/absence) of codes (or themes, messages, voices, and perspectives) in the 731 interpretive units of photographed exhibits, signage, maps, brochures, and audio recordings integrated into exhibits (Bernard Citation2011; Schensul and LeCompte Citation2013). Lastly, we assembled the empirical trends identified in the descriptive statistics into three primary themes with multiple components each that generally represent the interpretive materials across the 12 case study sites at the time of study.

It should be noted that this study represents the interpretive materials available at the time of our research in 2019. These materials may have been created at different times and by different people, therefore the interpretive materials studied are representative of their contexts, but are also analogous to other settler-colonial contexts. As a snapshot of the sites’ interpretive materials at the time of study, it is possible that interpretive materials have been updated since this research. Only interpretive materials that could be photographed or physically taken away by the researcher were included in the study and not the content of live or video recorded interpretation. Some of these more in-depth videos and live programming provided additional content beyond the interpretive materials selected for analysis in this study, particularly the use of first person contemporary Indigenous voices. For the purposes of comparison across all 12 sites, and to balance the amount of content which originated from each individual site, we decided to omit these interpretive mechanisms, which varied greatly across the sample. Indeed, previous research illustrates that live programming, videos, and other creative methods can supplement the stories told at heritage sites, which invites further analysis beyond the scope of this study (Wahl, Lee, and Jamal Citation2020; Tsenova, Wood, and Kirk Citation2022). As such, this research provides an understanding of what visitors were experiencing and learning at that specific moment in time from the interpretive materials that met the criteria and were accessible and comparable across sites.

4. Results and Discussion

Our research found that interpretive materials from 2019 at the case study sites follow specific narratives, share little authority, and are univocal. Indeed, as found in previous research on Indigenous representation in settler-colonialism, many heritage sites established at and after contact evince an enduring historic colonial presence, which can negatively impact relationships between governments and Indigenous peoples thus influencing interpretation and broader historical narratives (Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018; Onciul Citation2015). As such, external government entities administering and interpreting heritage sites still largely influence the manner in which sites present information to visitors, at times excluding differing perspectives and memories, especially those of Indigenous peoples with ancestral and contemporary relationships with the sites. Our findings reinforce and expand on these phenomena.

In the following sections, we present the results that emerged in our analysis of Indigenous representation in interpretive materials at the selected heritage sites. See for a breakdown of quantitative results and content analysis theme definitions. See for textured examples of themes and findings. Assembling our empirical results, we found three primary themes with multiple components each: (1) controlled historical narrative, (2) lack of shared authority, and (3) challenges in representing and/or integrating multiple ways of knowing. Through a multi-sited study conducted in 2019 using interpretive materials as the units of analysis, this research contributes to heritage studies and heritage site management by empirically illustrating unbalanced or absent representations of Indigenous experiences in interpretive materials across the selected heritage sites at the time of study with lessons learned and implications relevant to analogous settler-colonial contexts.

Table 1. Quantitative results of interpretive content analysis.

Table 2. Interpretive content analysis sub-theme examples.

4.1 Controlled Historical Narrative

Generally, there was a controlled historical narrative that characterized interpretive materials across the sample. Within this controlled historical narrative were the following four fixed narrative categories: (1) essentialized or static and unchanging Indigenous peoples; (2) non-Indigenous history; (3) settler-colonial contact history; and (4) nature largely devoid of culture. Each of the four narrative categories occurred in more than one quarter of interpretive units across the studied sites. With only a few exceptions, the major interpretive topics at individual sites fall within the four narrative categories.Footnote4 These narrative categories demonstrate a collective and largely celebratory mainstream U.S. history interpretive narrative of heritage sites. Jackson explains that at heritage sites, power lies in the production and reproduction of stories (Citation2016, 23). Indeed, part of nation-building is the use of the power of institutions like museums and heritage sites to create shared narratives, identities, and a sense of community (Anderson Citation1991). Nations often use tangible and monumental heritage to share and legitimize national ideologies and collective memories of the past (Smith Citation2006, 48–49). The stories either shared in or excluded from heritage interpretation often reinforce standard Western narratives of the past through Euro-American perspectives (Zerubavel Citation1995, 11; Smith Citation2010, 34; Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018). The four fixed narrative categories observed at studied heritage sites follow this pattern identified in the literature, presenting a constructed, commemorative history of the lives of Indigenous peoples before and at contact with Euro-Americans, of Euro-American expansion and success in the Northwest and Hawai‘i, of coexistence of Indigenous peoples and Euro-Americans, and of nature and its protection in U.S. government administered protected areas. This pattern reinforces power dynamics, preventing the telling of stories outside of these narratives, such as negative Indigenous experiences during the contact period and stories valued by Indigenous communities.

Essentialized Indigenous Peoples was the most common narrative category. This category occurred in 35.3% of interpretive units with the discussion of Indigenous peoples as primarily pre-contact and fixed in the past. Content within this narrative category focused on topics such as Indigenous materials and lifeways, Indigenous history before contact, traditional practices and beliefs, sacredness and connection to place, and Indigenous people and nature. More emphasis was placed on physical material culture and past lifeways, history, and traditional practices and beliefs. At many research sites, discussions focused on the ways Indigenous populations lived before contact with Euro-Americans, sharing information such as how they fed themselves, tools they used, the organization of societies and communities, and spiritual practices or belief systems – all in the past and using the past tense. Many of the observed interpretive displays place Indigenous peoples (if represented at all) in contrast with Euro-American settlers and colonizers. Several sites also organize interpretation on Indigenous peoples into separated topics related to material cultural such as basketry, tools and weapons, foods, and clothing and shelter. Case study sites focused on Hawaiian heritage generally followed these same patterns, discussing history, events, and traditional beliefs and practices with a perspective towards the past. Indeed, interpretation of Indigenous peoples at heritage sites often provides pre-contact and “pre-historic” representations, with minimal discussion of the present (Onciul Citation2015, 132).

Within this fixed narrative category of essentialized Indigenous peoples is very limited discussion of contemporary Indigenous populations. Interpretation of cultural continuity, contemporary Indigenous peoples, continued Indigenous cultural education, current practices, and current projects and collaborations only occurred in 9.6% of interpretive units. At some research sites these topics are never discussed. Many of these limited more up-to-date references were in the form of quotes from contemporary Indigenous people; discussions of current traditional practices, beliefs, and education; and the sharing of recent projects and collaborations. For example, at Sacajawea Historical State Park near the entrance of the interpretive center, is a large sign discussing current Tribal programming and recommendations to visit Tribal institutions. And at Puʻukoholā Heiau National Historic Site, an interpretive display discusses the site’s current Hawaiian partners and recent events held there. Indeed, previous research points out that interpretations of the past, heritage, and archaeology often fix Indigenous peoples in ancient beliefs and traditions, ignoring modern cultures and lives (Ross Citation2020, 66; Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018, 756). Lonetree adds that the exclusion or minimal interpretation of contemporary relationships and peoples can be problematic since it tends to perpetuate the viewpoint that Indigenous cultures are static and unchanging thus ignoring the living people and the importance and relevance of cultural landscapes, places, structures, and artifacts (Citation2012, 14). This type of presentation of Indigenous peoples is seen across the research sites, demonstrating a controlled historic narrative with a fixed narrative category focused on an essentialized view of Indigenous peoples’ lives before and at contact with Euro-Americans.

Next, non-Indigenous history, was the second most commonly used fixed narrative category. This narrative category was used in 28.7% of interpretive units. Interpretive use of this narrative category focused on the colonizer story of history typically devoid of Indigenous peoples. These descriptions discuss topics such as the U.S. military, exploration and settlement, the fur trade, missions and missionaries, and U.S. development, with a heavy focus on the U.S. military, exploration and settlement, and the fur trade. Within this narrative category, interpretation shared stories of the establishment and life at military and fur trading forts, the life of soldiers and fort residents, the exploration and establishment of Euro-Americans in the Northwest, and the founding of missions. The non-Indigenous history narrative category follows a greater American narrative of westward expansion and Euro-American success in the west. Devoid of Indigenous peoples and perspectives, these stories essentialize the settler-colonial experience and hint at Manifest Destiny ideals or where settlers are justified in their encroachment onto Indigenous lands from the east to the west coast, U.S. By telling these aspects of history without Indigenous peoples’ inclusion, interpretive displays seemingly lack a complete understanding of the past. This non-Indigenous history narrative category further demonstrates a controlled historical narrative of Euro-American and U.S. expansion and success in the Northwest, a common theme presented in U.S. history.

The third fixed narrative category, settler-colonial contact history was found in 27.9% of interpretive units at the studied sites. These interpretive stories, often told from the colonizer perspective, discuss both positive and neutral experiences of Euro-Americans and Indigenous peoples in contact-era events, such as exploration and settlement, the fur trade, and missions and boarding schools. Interpretive units within this narrative category focus on Euro-Americans’ interactions with Indigenous populations, essentializing the settler-colonial history of westward and Hawaiian Island exploration and establishment, missionary and boarding school interactions, and fur trade efforts, roles, and relationships. Many of these interpretive units emphasize the “pioneer spirit” and Euro-American success and efforts in collaboration with Indigenous populations, supporting a positive somewhat “multicultural” U.S. history narrative. These largely positive-leaning accounts of contact during the settlement and exploration of the U.S. west, the fur trade, and missionary efforts are common across the case study sites. This fixed narrative category follows an established narrative of the coexistence of Euro-Americans and Indigenous peoples.

The fourth fixed narrative category, nature largely devoid of culture, occurred in 26.5% of interpretive units. Interpretation with this narrative category discusses topics of regional plants and animals, the environment, bodies of water, geological features such as volcanoes, and natural history, with a specific focus on the nature and geology of the site being interpreted. This interpretation is largely devoid of discussion of human and cultural interactions with nature, with only certain case study sites discussing human interactions with the environment. The largest most geographically and biological diverse site in the study, Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park integrated information about Indigenous peoples and nature, mixing topics such as Indigenous knowledge and traditions into nature and conservation information. The select interpretive units that do this help to bridge the artificial divide between nature and culture that was observed in many of the studied interpretive units and seen at other heritage sites and areas protected for strict nature conservation (Harrison Citation2012). The majority of interpretive units within this narrative category often only connect humans and nature in discussions of Western environmental conservation. The U.S. National Parks were established at the end of the nineteenth century; this began a movement of people working to preserve the “wilderness” from human advancement. This perspective furthers views of humans and nature as separate in a manner inconsistent with perspectives commonly shared by Indigenous communities, and ignores Indigenous peoples’ removal from their ancestral and traditional lands (Cronon Citation1996; Vaccaro, Beltran, and Paquet Citation2013). This fixed narrative category of nature largely devoid of culture furthers this false dichotomy and erases negative aspects of the history of U.S. relations with Indigenous populations. Indeed, Ross explains that interpretation of heritage and the archaeological past that follow this nature-culture dichotomy typically ignores Indigenous peoples’ connection to place and the environment (Citation2020, 66). This narrative category demonstrates a common narrative of nature and its protection in American parks through the lens of Western conservation in which the land is seen as separate from humans, adding to a narrative of Euro-American success in the western U.S.

Overall, these four fixed narrative categories in the content of interpretive materials at these heritage sites at the time of study demonstrate the presence of a controlled historical narrative of the U.S. that determines and favors a common narrative and a shared memory of the past and of settler-colonial interactions (Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018, 755; Smith Citation2006, 58). A broad understanding of history is created by the use of the four fixed narrative categories: (1) essentialized Indigenous peoples; (2) the colonizer story of history; (3) settler-colonial contact history; and (4) nature largely devoid of culture. These narrative categories provide interpretation representing multiple people, events, and topics, but largely lack multiple perspectives. As Anila explains, in the creation of narratives it is important to recognize whose stories are shared and who has the power to share them (Citation2017, 110). Indeed, as heritage sites develop interpretive plans and create interpretive materials, they are often required to fit their work into sites’ established timeframes and interpretive themes. Employees at these sites, in turn, often unknowingly continue to interpret and create content within the confines of controlled historical narratives, missing opportunities to challenge common U.S. narratives. These controlled historical accounts reinforce unbalanced power dynamics between Indigenous peoples and heritage sites, barring other stories from being told, such as the negative experiences of Indigenous peoples during contact, the stories and history valued by Indigenous populations, or other accounts outside typical or mainstream U.S. narratives of a place. Communities ignored or misrepresented in these narratives may in turn view this type of interpretation as incorrect or degrading (Macdonald Citation2016, 267). By offering perspectives outside of the four fixed narrative categories, heritage sites can therefore challenge common memories and stories, more equitably expanding their representations of the past (Smith Citation2006, 49) and the peoples connected to these important places.

4.2 Lack of Shared Authority

There was a lack of shared authority in the portrayal of information within the content of the four fixed narrative categories. The stories shared at the studied sites are largely told by a generalized narrative voice sharing some authority in the retelling of history with Euro-American voices. As such, we define authority as the ability of a group or person to speak for themselves, be taken seriously as knowledge holders, and be represented in the data (Onciul Citation2015). This imbalance in authority in interpretive materials at heritage sites is represented in the voice, citations and quotations, and historical people named in the interpretive texts. Content analysis of these interpretive units showed very little first-person voice, more quotes and citations of Euro-Americans, and more Euro-Americans named in the interpretive units at studied sites.Footnote5

The selected sites used very little first-person voice. We define voice as the perspective and communication style in an interpretive unit (Onciul Citation2015). More than three quarters (76.1%) of the interpretive units used narrative voice to share interpretive stories. This narrative voice is a general, omniscient style of communication that does not indicate a specific group or person as the communicator. But due to the context of the sites and their administration by non-tribal governments, the narrative voice is clearly a Euro-American voice. The second most common voice used in the interpretive units is a management and park voice. This voice is used in 14.9% of interpretive units. Management and park voice often focuses on communicating rules, regulations, and site orientation information to visitors. The use of these two voice types maintains authority in the site, sharing little authority with outside parties. Passive voices, such as these, give no agency to those discussed in the interpretation, such as Indigenous peoples, with their experiences of the past and present being largely silenced. It removes responsibility for what is shared in interpretation (Onciul Citation2015, 7).

Euro-American and Indigenous groups have very little authority through first-person voice in the telling of the narratives at sites. Euro-American voice is used overtly in 5.1% of interpretive units and Indigenous voice is used overtly in 4.5% of interpretive units. Some sites used no Euro-American or Indigenous voice. While these are both small percentages, it is important to recognize that the abundant narrative voice, though not overtly stated, is a Euro-American voice and representation of history. In many instances, the use of Euro-American or Indigenous voice occurs where interpretation consists largely of quotes – such as missionary diary submissions at Whitman Mission National Historic Site – rather than where an unquoted message appears. Where sites use the Indigenous voice in interpretation, it occurs through direct statements from Indigenous peoples or through the use of traditional stories. This was seen in the Nez Perce National Historical Park brochure, which contains a direct message from a member of the Chief Joseph band of the Colville Confederated Tribes, Albert Andrews Redstar. This message tells the visitor to reflect on the site’s history and meaning, stating “In some places we are also visitors, as are you. Remember this when you enter the Salmon and Snake River and the Wallowa Valley countries, that this was also our home … once (United States Department of the Interior Citation2015, 2).” Yet for the most part, the critical Indigenous voice that illustrates contemporary culture is absent.

Additionally, a lack of Indigenous authority and representation is demonstrated in patterns revealed in analysis of citations, quotes, and references used at sites. Euro-Americans were the most cited and quoted group, making up almost half (46.4%) of all quotes and citations. Scientists, historians, historic texts, newspapers, and other similar sources made up just less than a quarter (23.2%) of citations and quotes across all interpretive units. While these types of citations are not explicitly linked to Euro-Americans, oftentimes these types of sources are from Euro-Americans and give more authority to their narrative voice. As observed at Hawaiian sites, Indigenous people can have multiple identities and roles, in that there may be Indigenous site staff or scientists included in quotes and references without their Indigenous identity being recognized.

A limited use of quotes and references from Indigenous peoples further demonstrates this lack of authority. Less than a quarter (22.1%) of citations and quotes are from Indigenous peoples, with an additional 8.4% being from traditional Indigenous stories. Most of the quotes that are from Indigenous peoples are fairly recent, which helps to emphasize that Indigenous peoples remain connected to sites. In contrast, the use of traditional stories places Indigenous peoples in the past if they are presented only in pre-contact times without appropriate context. Through these types of quotations, little authority is given to Indigenous peoples in the telling of their own history. Although recorded history from Indigenous populations may be unavailable to sites, living Indigenous peoples could potentially share this knowledge and provide references to and quotations for incorporation in interpretive materials. Many sites rely on historical records and journals of Euro-Americans for quotations, such as using the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to tell accounts of the Expedition and their interactions with Indigenous peoples along the way. This type of narrative gives more authority and representation to Euro-Americans, leaving Indigenous peoples lacking representation.

Further, a lack of shared authority with and representation of Indigenous peoples is further illustrated in the use of names of people from history in interpretation. Euro-Americans make up nearly two-thirds (65.6%) of named people, while Indigenous peoples make up only one-third (34.4%) of all named people from history. In many instances, interpretive signs name several Euro-Americans, while naming only one or no Indigenous person. Across all the observed sites, only at three sites did Indigenous peoples make up more than half of all people named from history; and each of these sites has a distinct interpretive focus on Hawaiian heritage. The Indigenous peoples named in interpretation often were considered unique or exceptions to history. A study by Modlin, similarly found that the interpretive stories shared about enslaved peoples’ experiences were those of the “(a)typical individual slave” who was presented as an example of the entire enslaved population’s experience when in reality these enslaved Africans had extraordinary lives or special positions, and/or had escaped from enslavement (Citation2008, 281–282). Overall, at three-quarters of the studied sites, Euro-Americans from history are named more than Indigenous peoples within the interpretation and narrative categories. The sites selected for this research all have Indigenous history and peoples connected to them, making this disparity in naming people from history even more significant.Footnote6 Using the names of Indigenous people within interpretation can indicate their contribution and knowledge, demonstrating authority in self-representation (Krmpotich and Anderson Citation2005). By using the names of more Euro-Americans from history than Indigenous peoples, site interpretation places more emphasis on the importance of Euro-Americans’ roles in the version of history that is being told, resulting in Euro-Americans having more authority through greater representation, and Indigenous peoples having little shared authority or representation.

In sum, a lack of shared authority in the portrayal of information in the fixed narrative categories results from minimal use of first-person voice, disproportionate quotations from Euro-Americans, and more naming of Euro-Americans from history. This provides more authority to Euro-Americans – emphasizing their importance while excluding critical Indigenous voices and representation. Indeed, most historical records and accounts typically do not tell precisely what happened, but how the recorder of the event experienced it (Trouillot Citation1995, 2–26). The production of history occurs in situations of unequal power that silence the stories of the less powerful (Trouillot Citation1995). In giving more story-telling authority to a general narrative voice and to Euro-Americans, heritage sites largely favor the Euro-American experience of history. Indigenous populations and other groups influenced by colonial powers are often excluded in the telling of history or, in limited instances, are “allowed” to share their stories by Euro-American authority-holders (Smith Citation2010, 33–34).

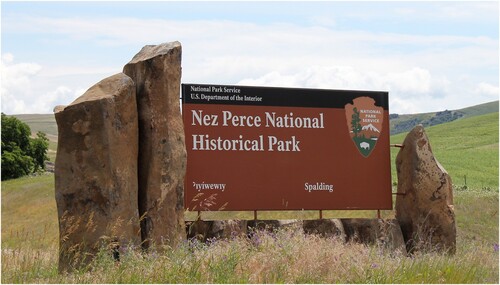

Scholars and practitioners have increasingly encouraged sharing voice and authority in museums and heritage sites (e.g., Anila Citation2017; Jackson Citation2016; Krmpotich and Anderson Citation2005; Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018; Lonetree Citation2012; Onciul Citation2015, Citation2019; Quinn and Pegno Citation2014; Watterson and Hillerdal Citation2020). By sharing authority and voice with multiple populations, especially through recognizing and honoring Indigenous sovereignty as well as ancestral and current place-based Indigenous ties, interpretation better demonstrates the intricacies, varieties, and nuances of cultures and histories, brings Indigenous voices and presence forward, and creates a safe space in which Indigenous communities feel represented and heard (Onciul Citation2015, 7–8; Spoon and Arnold Citation2012; Tapsell Citation2019). One initial way this is accomplished at sites is by including an Indigenous site name on park signs, such as the sign at Nez Perce National Historical Park, which lists both the Indigenous site name and the Spalding site name, creating an immediate indication of Indigenous presence to visitors (). Or further creating an Indigenous presence with a statement such as those that recognize the Nuwu/Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute/Chemehuevi) ancestral homeland at three refuges in the Desert National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Nevada, stating, “Nuwuvi Ancestral Lands” under the site name on various entrance signs. These sites also each provide a welcome to the public from a first person Indigenous perspective on an interpretive sign with accompanying evocative imagery and/or Indigenous art (Spoon and Arnold Citation2012, Citation2016; Verschuuren et al. Citation2021). Indigenous voice in interpretation can authenticate people’s histories, experiences, and identities, and emphasize that they are not just in the past (Onciul Citation2015, 8; Sandahl Citation2019). This is especially important at heritage sites with difficult and colonial histories, as the past still affects current experiences of descendent communities and individuals (Jackson Citation2016, 30). By recognizing cultural erasure in history and beginning to privilege Indigenous voices in interpretation, heritage sites can honor Indigenous experiences and history (Lonetree Citation2012, 169–171) as well as equitably and respectfully weave these more balanced voices into broader historical narratives of the region, nation, and beyond.

4.3 Challenges in Representing and/or Integrating Multiple Ways of Knowing

Lastly, we found that there were challenges in representing and scant integration of multiple ways of knowing within the interpretive narratives across the sites. This is demonstrated in univocal interpretation, with little multivocality and minimal inclusion of negative aspects of contact history – essentially little sharing of perspective and voice. We define univocality as the use of a single voice or perspective in an interpretive unit and define multivocality as the use or presence of multiple voices and the perspectives of more than one people in an interpretive context. This type of representation can reinforce dominant views of the past and prevent an honest telling of what happened in history (Smith Citation2006).

Across all sites investigated, univocality is the norm within interpretive materials. Three quarters (75.4%) of all the interpretive units use univocal interpretive language, providing only a single voice or perspective on the narrative being presented. The percentage of univocality used across the studied sites ranges from 41.9% to as high as 90.2% of interpretive units at individual sites. Univocality can often be read as a neutral presentation of information; however, it does not recognize the presence of different perspectives and can reinforce dominant views of the past. Given that the studied heritage sites are connected to multiple groups of peoples, these places could have multiple understandings of and varied perspectives on their histories. Although common across all the study sites, univocality provides a narrow perspective of the past and present, resulting in narrative categories without blended, multiple ways of knowing.

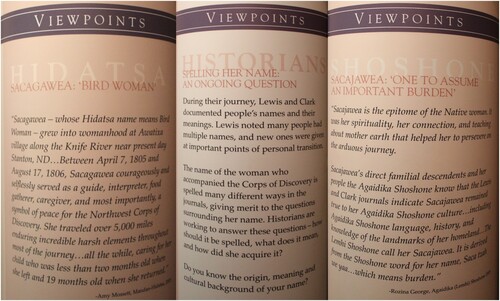

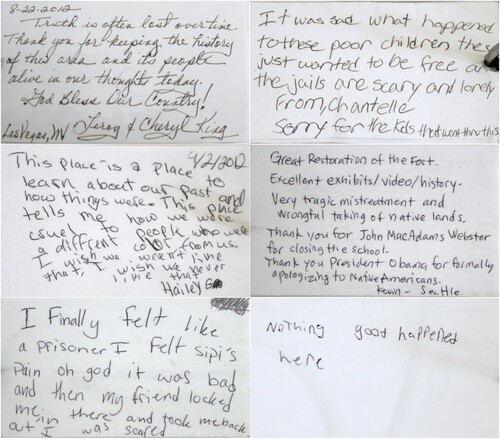

Multivocality is used in less than one quarter (20.4%) of the interpretive units. The use of multivocality allows for the presence of multiple voices and perspectives, in turn leading to multiple and potentially blended ways of knowing. The percentage of multivocality used across the observed sites ranges from 29.1% to as low as 2.2%. When used at sites, the types of multivocality employed range from simple terms or statements suggesting the presence of more than one perspective, to the sharing of multiple views in one statement, to interpretive displays placing different perspectives side-by-side () or stating that contrasting views or opinions might exist. Fort Spokane in Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area takes this even further, allowing visitors to comment on their experiences of seeing soldiers’ and Indigenous children’s perspectives side-by-side. The interpretation then displays the visitor comments (). An alternative approach we propose beyond multivocality is polyvocality where a single holistic narrative is presented that includes the perspectives of multiple actors in contexts of power (Anila Citation2017; Mason, Whitehead, and Graham Citation2013; Tsenova, Wood, and Kirk Citation2022).

Figure 2. Multiple perspectives interpretation – “Viewpoints,” Sacajawea Historical State Park. Note the three different perspectives provided from the views of the Hidatsa, historians, and the Shoshone. Photograph by Leah Rosenkranz.

Figure 3. Visitor reflections – Fort Spokane, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. Note the feelings expressed in the comments, demonstrating visitors’ perspectives on the site after being exposed to the difficult history of the site and boarding school. Photograph by Leah Rosenkranz.

Recent research suggests that heritage sites can successfully bring forward diverse perspectives by design, incorporating multivocality into the production and content of interpretive media (Anila Citation2017; Ballantyne, Packer, and Bond Citation2012; Kryder-Reid Citation2016; Shelton Citation2019). By combining different perspectives of a site’s history using people’s own knowledge and memories, interpretation can demonstrate to different people the complexity of a site and its history and meaning (Haraway Citation1991; Phillips Citation2019). Further, including Indigenous voices in interpretation can help to ensure that voices other than those of colonizers and settler colonial societies are expressed in places where Indigenous peoples lack power (Butler Citation2011). For example, at Fort Spokane, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area a large interpretive display of a timeline begins with a statement from the Spokane and Colville Tribes explaining that they have “lived continuously on this land since time immemorial,” then continues with history up to the present, with a representation of a calendar ball tying together oral history and later events in time. In a different approach, Puʻukoholā Heiau National Historic Site has entire interpretive displays with text in the Hawaiian language and the reverse side in English. Multivocality can indeed reduce bias, challenge misinformation, and address contested history in a meaningful way (Onciul Citation2015, 163). With less than one-quarter of interpretive units using multivocality, a lack of representation and/or integration of multiple ways of knowing exists in interpretation at these studied sites.

Further, a minimal representation of negative contact history presents only a partial story and results in superficial positive messaging that does not engage the real-world trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples during the contact period. Discussions of negative contact history only occur in 12.0% of interpretive units across all the observed sites. In comparison to the four narrative categories, this is a very low occurrence. The instances where interpretation does discuss negative contact history, topics such as war and violence, missions and boarding schools, reservations, disease, and land destruction are mentioned. These aspects of site history are important to providing the visitor with a more holistic understanding through the sharing of multiple perspectives of the past. In the lack of discussion of these topics, multiple ways of knowing are not represented and blended narratives are not created, resulting in history being viewed through “rose colored glasses.” In excluding negative contact history, sites maintain common U.S. narratives and present less diverse perspectives of the past (Liu, Dupre, and Jin Citation2021, 451; Smith Citation2006). The inclusion of negative or counter narratives can help to challenge collective assumptions and simplified meanings of the past, while highlighting traditionally ignored voices and histories (Anila Citation2017, 113). Indeed, more accurate portrayals of site history that contain contradictions and contested meanings can be a strength that enhances the visitor experience while balancing broader historical narratives that may only tell part of the history through a potentially biased lens. In losing the negative aspects of history, site interpretation can fall back into the traditional four fixed narrative categories shared prior.

In sum, challenges in representing and/or integrating multiple ways of knowing in interpretive materials is attributed to the high use of univocality, limited use of multivocality, and little representation of negative contact history. This type of interpretation maintains a single perspective, reinforces dominant views, and provides a positive representation of history. The creation and use of univocal narratives of history often silences aspects of the past (Trouillot Citation1995). The erasure of history is a part of the process of creating “hegemonic accounts” of history; and providing a single, unblended narrative of the past in interpretation tells history in positive ways that do not challenge grand U.S. narratives of the past (Farmer Citation2004, 308). Conversely, by telling the story of sites in a multivocal and blended manner, heritage sites can share the power of representation, enhancing cultural understanding (Ballantyne, Packer, and Bond Citation2012; Haraway Citation1991).

5. Conclusion

Collectively, our findings empirically illustrate absent or unbalanced Indigenous representation in interpretive materials across select heritage sites in Hawai‘i and Cascadia. We argue that Indigenous representation in interpretive materials at heritage sites can be divided into three primary themes: (1) controlled historical narrative; (2) absence of shared authority; and (3) challenges in representing and/or integrating multiple ways of knowing. These themes suggest that heritage sites administered by government agencies and their partners contained interpretive materials at the time of study that reinforced unequal power structures and prevailing narratives of historical colonial powers, often excluding stories and perspectives that fall outside of the dominant group’s way of recounting history (Kryder-Reid et al. Citation2018; Smith Citation2006, Citation2010; Zerubavel Citation1995). These processes and resulting interpretive content at heritage sites can also influence national narratives and stories, which can be further used to reinforce cultural erasure and social inequality through the dominant group’s viewpoint (Jackson Citation2016; Smith Citation2006; Young Citation1993). Indeed, the stories presented in interpretive materials at these heritage sites offered generalized, omniscient and Euro-American voices that share little authority with Indigenous peoples, providing uniform, univocal accounts of history. This controlled historical narrative leaves out Indigenous voices and perspectives, creating interpretive content that lacks shared authority and multivocality. Indeed, the interpretive materials analyzed tended to privilege colonial, Euro-American perspectives of history, ignoring the lasting effects of colonialism and the contemporary presence of Indigenous peoples and their relationships with the landscapes where the sites are situated. As such, previous research indicates that heritage sites actively serve to reinforce and construct meaning and to shape public understandings of the past. These heritage landscapes often serve as sites of memory and belonging, where identities are actively negotiated by communities and nations (Baird Citation2017, 4; Jackson Citation2016, 24; Kølvraa and Timm Knudsen Citation2020). Within settler-colonial contexts like the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, as in this study, representations of Indigenous history are generally at once significant loci of contestation and can be absent or misinformed in prevailing interpretive material narratives (Liu, Dupre, and Jin Citation2021; Smith Citation2006).

Our findings and associated interpretations also confirm that heritage sites struggle to address difficult and painful pasts, such as those of colonial encounters and physical violence, though they hold the potential as venues for reflection and critical discussion of these pasts through key narratives and multiple perspectives (Logan Citation2019, 176). Just as lasting colonial influences continue to shape government relationships with Indigenous peoples today, these influences continue to affect the interpretation of heritage sites – perhaps especially those sites where Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples’ histories intersect and collide. The powers of government agencies in settler-colonial contexts that administer and interpret heritage sites, as well as their formal mandates to publics real or imagined, still significantly influence the media and messages presented to visitors. The complexity of the histories of these sites, and the complexities of those histories’ meanings each is lost in interpretation that: follows unified and common narratives, shares little authority with minority voices and views, and lacks representation and integration of multiple ways of knowing that potentially embrace the complex realities and meanings of history in place. Even within the narrow mandates of government agencies, these represent missed opportunities: for realizing the potential diversity, equity, and inclusiveness of interpretive media and processes; and for sharing with visitors a more holistic, representative, and equitable view of the histories of places, in their full complexity and richness. We agree with Onciul who states, “heritage sites and museums are important points of entry for Indigenous peoples’ voices into mainstream society because they have the ability to validate identities, histories, culture and societies” (Citation2015, 8). Indeed, as heritage sites identify the ways in which they tell stories of the past, they can work towards building interpretation and programming that raises Indigenous voices, increases Indigenous presence, recognizes enduring Indigenous ancestral connections with sites and their broader cultural landscapes, and identifies interactions and exchanges between Indigenous peoples and settler populations. (In order to further operationalize our findings, we developed which outlines our lessons learned and heritage site management recommendations.) Bringing forward Indigenous voices, sharing authority, representing and integrating multiple ways of knowing, sharing stories that defy prevailing narratives, and reinforcing contemporary Indigenous presence at sites: together, these ingredients can help broaden the scope and veracity of interpretive messaging at heritage sites in settler-colonial contexts, while beginning to redress generations of physical and textual erasure of past and present Indigenous peoples from their ancestral homelands.

Table 3. Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Increasing Indigenous Representation, Voice, and Authority in Heritage Site Interpretive Materials.

Geological Information

Fort Simcoe Historical State Park; Nez Perce National Historical Park; Fort Spokane in Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area; Fort Nisqually Living History Museum, Point Defiance Park; Pu'uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park; The Volcano Art Center in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park and Niaulani Campus Administrative Office & Gallery in Volcano Village; Spokane House Interpretive Center, Riverside State Park; Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park; Pu'ukoholā Heiau National Historic Site; Sacajawea Historical State Park and Interpretive Center; Whitman Mission National Historic Site; Kamakahonu National Historic Landmark.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of our research collaborators and individuals who supported this research. We thank Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and the National Park Service who made this work possible through their funding and collaboration. We also thank the Wayne Suttles Graduate Fellowship for their funding of the thesis paper that this article evolved from. Special thanks to the Native American Tribes and Tribal Nations, Canadian First Nations, and Native Hawaiian organizations with cultural and historic ties to the Fort Vancouver landscape who guided and encouraged this work. We would also like to thank David Harrelson of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde for his efforts in supporting and guiding our research and work. We thank the leaders, members, and community of the case study sites for welcoming us: Fort Simcoe Historical State Park, Nez Perce National Historical Park, Fort Spokane in Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, Fort Nisqually Living History Museum in Point Defiance Park, Pu'uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, The Volcano Art Center in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park and Niaulani Campus Administrative Office & Gallery in Volcano Village, Spokane House Interpretive Center in Riverside State Park, Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park, Pu'ukoholā Heiau National Historic Site, Sacajawea Historical State Park and Interpretive Center, Whitman Mission National Historic Site, and Kamakahonu National Historic Landmark. We would also like to thank Doug Wilson, Theresa Langford, and Tracy Fortmann for their continued support throughout this project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, we use a broad definition for the term Indigenous that recognizes groups in a manner largely defining Indigenous peoples as first peoples to a specific geographic area who have been disrupted or displaced by colonization (Corntassel Citation2003; Secretariat of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Citation2009; Trigger and Dalley Citation2010). A broad definition was used to incorporate Kanaka ‘Ōiwi, Native Hawaiian, peoples in the research and analysis, without a need for separate terms. Hawaiian ancestors are Polynesians who navigated the ocean to the archipelago now known as Hawai‘i, over time developing a distinct language and culture (Brown Citation2019, vii). This definition includes both traditionally associated Indigenous peoples and those colonially-relocated to a place. These two different relations to place affect the experience, knowledge, and history people have with sites. While there is value in discussing the unique experiences of local or traditionally associated Indigenous peoples with a special focus or as a unique category of Indigeneity, for this project these specifications are set aside in favor of a broader use of the term Indigenous, in order to begin to quantify Indigenous representation in interpretation at the studied sites in a manner addressing all Indigenous peoples with ancestral ties to the sites.

2 During this study we also conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews. This paper focuses on interpretive materials only. For additional findings from interviews, see Rosenkranz, Spoon, and Deur Citation2021.

3 We selected Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park for: (1) its intangible cultural heritage connected to the volcano; (2) its example of the nature-culture relationship at a significant landscape scale; and (3) one of the author’s relationship with the site (Spoon Citation2007).

4 Some sites include discussions of negative contact history and preservation and conservation in one-quarter or more of interpretive units. Discussions of negative contact history typically are combined with contact history, and discussions of preservation and conservation are often integrated with site messages about physical protection of the site or integrated with discussions of nature and geology.

5 We recognize that in some instances, non-Indigenous voices may be disproportionately available to agencies within historical sources, and obtaining and incorporating content from historical Indigenous sources and contemporary Indigenous peoples can be difficult, have extra costs, and require extra effort and expertise to engage contemporary Indigenous communities.

6 We recognize that in some cases there may not be names on record for Indigenous peoples, resulting in a greater number of named Euro-Americans.

References

- American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 [AIRFA]. Public Law 95-341(1994), 42 USC § 1996.

- Aguilera, Jasmine. 2020. “Confederate Statues are Being Removed Amid Protests Over George Floyd's Death. Here's What to Know.” Time, June 24, 2020. https://time.com/5849184/confederate-statues-removed/.

- American Institute for Conservation and Foundation for Advancement in Conservation. 2022. “Land Acknowledgement and Actions.” American Institute for Conservation. https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-us/land-acknowledgement/.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

- Anila, Swarupa. 2017. “Inclusion Requires Fracturing.” Journal of Museum Education 42 (2): 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2017.1306996.

- Association of Independent Museums. 2021. “Heritage Sector Organisations Issue Joint Statement of Intent.” Association of Independent Museums. https://aim-museums.co.uk/heritage-sector-organisations-issue-joint-statement-intent/.

- Baird, Melissa F. 2017. Critical Theory and the Anthropology of Heritage Landscapes. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Ballantyne, Roy, and Karen Hughes. 2003. “Measure Twice, Cut Once: Developing a Research-Based Interpretive Signs Checklist.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 19: 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0814062600001439.

- Ballantyne, Roy, Jan Packer, and Nigel Bond. 2012. “Interpreting Shared and Contested Histories: The Broken Links Exhibition.” Curator: The Museum Journal 55 (2): 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2012.00137.x.

- Barcalow, Kate Monti, and Jeremy Spoon. 2018. “Traditional Cultural Properties or Places, Consultation, and the Restoration of Native American Relationships with Aboriginal Lands in the Western United States.” Human Organization 77 (4): 291–301. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259.77.4.291.

- BBC. 2020. "Theodore Roosevelt Statue to be Removed by New York Museum.” BBC, June 22, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53135599.

- Bearfoot, Cheyenne. 2022. “Land Back: The Indigenous Fight to Reclaim Stolen Lands.” KQED Radio, April 21, 2022. https://www.kqed.org/education/535779/land-back-the-indigenous-fight-to-reclaim-stolen-lands.

- Benton, Gregory M. 2011. “Visitor Perceptions of Cultural Resource Management at Three National Park Service Sites.” Visitor Studies 14 (1): 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2011.557631.

- Bernard, H. Russell. 2011. Research Method in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Oxford, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Bright, Candace Forbes, Kelly N. Foster, Andrew Joyner, and Oceane Tanny. 2021. “Heritage Tourism, Historic Roadside Markers and “Just Representation” in Tennessee, USA.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29 (2-3): 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1768264.

- Brown, Marie Alohalani. 2019. “Forward.” In The Past before Us: Moʻokūʻauhau as Methodology, edited by Nālani Wilson-Hokowhitu, vii–vix. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Burch-Brown, Joanna. 2020. “Should Slavery’s Statues Be Preserved? On Transitional Justice and Contested Heritage.” Journal of Applied Philosophy 39 (5): 807–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12485.

- Butler, Shelley Ruth. 2011. Contested Representations: Revisiting into the Heart of Africa. Tonawanda, NY: University of Toronto Press.

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C., and T. J. Ferguson. 2006. “Memory Pieces and Footprints: Multivocality and the Meanings of Ancient Times and Ancestral Places among the Zuni and Hopi.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.148.

- Corntassel, Jeff J. 2003. “Who is Indigenous? ‘Peoplehood and Ethnonationalist Approaches to Rearticulating Indigenous Identity.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 9 (1): 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537110412331301365.

- Cribbs, Sarah E., and Ruby Rim. 2019. “Heritage or Hate: A Discourse Analysis of Confederate Statues.” American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research 3 (3): 201–210.

- Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” In Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, edited by William Cronon, 69–90. London: Norton and Company.

- Deur, Douglas. 2012. “An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.” Pacific West Region: Social Science Series Publication Number 2011-12, Northwest Cultural Resources Institute Report No. 15. Seattle: Pacific West Region, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

- Di Leonardo, Micaela. 1993. “What a Difference Political Economy Makes: Feminist Anthropology in the Postmodern Era.” Anthropological Quarterly 66 (2): 76–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/3317106.

- Edwards, Curtis. 1994. A Region 6 Interpretive Services Aid: Interpretive Project Guide Book. Portland: Okanogan National Forest, Pacific Northwest Region, U.S. Deparrtment of Agriculture. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5104524.pdf.

- English Heritage. 2020. “English Heritage’s Historic Memorials and Black Lives Matter.” English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about-us/search-news/historic-memorials-statues-and-black-lives-matter.

- Farmer, Paul. 2004. “An Anthropology of Structural Violence” Current Anthropology 45 (3): 305–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/382250.

- Frank, Sybille, and Mirjana Ristic. 2020. “Urban Fallism: Monuments, Iconoclasm and Activism.” City 24 (3-4): 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1784578.

- Grovier, Kelly. 2020. “Black Lives Matter protests: Why are Statues so Powerful?” BBC, June 12, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200612-black-lives-matter-protests-why-are-statues-so-powerful.

- Guy, Jack. 2020. “Britain's Imperialist Monuments Face a Bitter Reckoning Amid Black Lives Matter Protests.” CNN, June 11, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/uk-statues-protest-movement-scli-intl-gbr/index.html.

- Hanson, Kelsey E., Steve Baumann, Theresa Pasqual, Octavius Seowtewa, and T. J. Ferguson. 2022. “This Place Belongs to Us’, Historic Contexts as a Mechanism for Multivocality in the National Register.” American Antiquity 87 (3): 439–456. https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2022.15.

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge Press.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2012. Heritage: Critical Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Hoelscher, Steven. 2011. “Heritage.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by Sharon Macdonald, 198–218. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing.

- Ishisaka, Naomi. 2022. “Why We Should Transfer ‘Land Back’ to Indigenous People.” The Seattle Times, October 17, 2000. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/why-we-should-transfer-land-back-to-indigenous-people/.

- Jackson, Antoinette T. 2016. Speaking for the Enslaved: Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites. New York: Routledge.

- Kaur, Harmeet. 2020. “Indigenous People Across the US Want Their Land Back – And the Movement is Gaining Momentum.” CNN, November 26, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/25/us/indigenous-people-reclaiming-their-lands-trnd/index.html.

- Kølvraa, Christoffer, and Britta Timm Knudsen. 2020. “Decolonizing European Colonial Heritage in Urban Spaces – An Introduction to the Special Issue.” Heritage & Society 13 (1-2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159032X.2021.1888370.

- Krmpotich, Cara, and David Anderson. 2005. “Collaborative Exhibitions and Visitor Reactions: The Case of Nitsitapiisinni: Our Way of Life.” Curator: The Museum Journal 48 (4): 377–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2005.tb00184.x.

- Kryder-Reid, Elizabeth. 2016. California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and Politics of Heritage. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kryder-Reid, Elizabeth. 2018. “Introduction: Tools for a Critical Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (7): 691–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1413680.

- Kryder-Reid, Elizabeth, Jeremy W. Foutz, Elizabeth Wood, and Larry J. Zimmerman. 2018. “‘I Just Don’t Ever Use That Word’: Investigating Stakeholders’ Understanding of Heritage.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24(7): 743–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1339110

- Leng, Ts-Kang, and Rung-Yi Chen. 2021. “The Red Culture and Political Economy of Museums in Shanghai.” China Review 21(3): 247–270.

- Little, Barbara J., and Paul A. Shackel. 2014. Archaeology, Heritage, and Civic Engagement: Working toward the Public Good. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Liu, Yang, Karine Dupre, and Xin Jin. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Literature on Contested Heritage.” Current Issues in Tourism 24 (4): 442–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1774516.

- Logan, Karen. 2019. “Collecting the Troubles and Beyond: The Role of the Ulster Museum in Interpreting Contested History.” In Difficult issues: ICOM International Conference, 21−23 September 2017 in Helsingborg, Sweden: Proceedings, edited by ICOM Deutschland, 166–178. Heidelberg: Art Historicum.

- Lonetree, Amy. 2012. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Macdonald, Sharon. 2016. “Exhibiting Contentious and Difficult Histories: Ethics, Emotions and Reflexivity.” In Museums, Ethics and Cultural Heritage, edited by Bernice L. Murphy, 267–277. London: Routledge.

- Mason, Rhiannon, Christopher Whitehead, and Helen Graham. 2013. “One Voice to Many Voices? Displaying Polyvocality in an Art Gallery.” In Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration, edited by Viv Golding, and Wayne Modest, 163–177. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- McGonigle Leyh, Brianne. 2020. “Imperatives of the Present: Black Lives Matter and the Politics of Memory and Memorialization.” Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 38 (4): 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0924051920967541.

- Modlin Jr, E. Arnold. 2008. “Tales Told on the Tour: Mythic Representations of Slavery by Docents at North Carolina Plantation Museums.” Southeastern Geographer 48 (3): 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.0.0025

- Morris, Phillip. 2020. “As Monuments Fall, How Does the World Reckon with its Racist Past?” National Geographic, June 29, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/confederate-monuments-fall-question-how-rewrite-history.

- Museums Association. 2020. “Ending Racism in Museums.” Museums Association. https://www.museumsassociation.org/campaigns/advocacy/ending-racism-in-museums/.

- National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 [NEPA]. 2021. Public Law, 91–190. 42 USC § 1501.

- National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 [NHPA]. 2016. U.S. Code 54, 36 CFR § 800.

- National Park Service. 2007. Foundations of Interpretation Curriculum Content Narrative: Types of Interpretation. Electronic Document, http://www.nps.gov/idp/interp/101/FoundationsCurriculum.pdf.