ABSTRACT

The United Kingdom (UK) lacks a uniform approach to safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (ICH) such as language. The UK ratified the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in June 2024. In the absence of any UK-wide ICH framework, various approaches to safeguarding ICH have been taken at nation-level and at the level of (usually individual) museums, libraries and heritage groups. ICH can bring tangible heritage to life and give objects meaning and enhance the dynamic of cultural heritage. However, although language is included in the UNESCO Convention, to the extent that it is a “vehicle” of ICH, only recently have some museums and other organizations started to exhibit language. This article sets out our research findings from a pilot study undertaken in 2022 where we engaged with heritage sector professionals to identify how their organizations currently work with language heritage. Participants in our study voiced concerns that language heritage can be hard to encapsulate. We outline the challenges and successes of language heritage work, as well as the support that professionals felt they needed to undertake further work to enable them to engage with the public and local communities in order to safeguard this important aspect of ICH.

Introduction

The United Kingdom (UK) lacks a uniform approach to safeguarding intangible cultural heritage (ICH) such as language. UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage 2003 (the “UNESCO Convention”) creates an inventory of ICH and encourages state engagement with communities to preserve and revitalize their practices, traditions and oral traditions and expressions. This includes language to the extent that it is “a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage” (Article 2(2)(a), UNESCO Convention). However, the UK only ratified the UNESCO Convention in June 2024. In the absence of any UK-wide ICH framework up until now, various approaches to safeguarding ICH have been taken at nation-level (e.g., ICH Scotland Wiki maintained by Museums and Galleries Scotland) and at the level of (usually individual) museums, libraries and heritage groups. At this current time, it may be useful to consider whether a more uniform approach might be useful, or at least to understand more about different practices around the country in preparation for immediate steps following ratification.

This article sets out our research findings from a pilot study undertaken in 2022 in which we engaged with heritage sector professionals to address the following research questions:

How are museums and heritage organizations around the UK currently working with language heritage?

What challenges and barriers have they encountered and how are they working to overcome these?

How do they expect to work with language heritage in the future?

We outline the challenges and successes of such work, as well as the support that professionals felt they needed to undertake further language heritage work to enable them to engage with the public and local communities in order to safeguard this important aspect of ICH.

We begin by defining our approach to “language heritage” in the UK context. We also signpost some recent developments in the ICH field, before presenting examples from around the world of how the heritage sector has worked with language heritage and public and community audiences. Next, we provide an overview of some of the challenges that have been identified by other professionals and researchers. We then turn to our study, explaining our methodology and giving examples of language heritage work in the UK elicited from museum professionals and museum websites, including five case studies, which highlight good practice but draw attention to a rather fragmented approach and lack of knowledge sharing. We also analyse some of the challenges and barriers encountered by heritage sector professionals in working with language heritage. Finally, we consider how such obstacles can be overcome and the support that organizations need to develop their language heritage projects.

Language Heritage

Language is a key marker of identity, allowing individuals to place themselves within the framework of their communities and the wider landscape. As Bialostocka (Citation2017, 18) argues, it represents “living heritage”, as a “repository and an organic inventory system […] contained in the linguistic interactions of the people who produce it”. We argue elsewhere (Braber and Howard Citation2023) that language, including dialects, accents and lexicons of UK communities, must be included within approaches which aim to safeguard the UK’s ICH. Language heritage is a crucial repository for community practices (Bialostocka Citation2017), enhances feelings of belonging (Sarma Citation2015) and promotes well-being (Gibson et al. Citation2021). We also concur with Gahtan, Cannata, and Sönmez (Citation2020, 7), that spoken linguistic varieties which lack documentation are frequently ignored and so our project was keen to capture practices which seek to safeguard all forms of linguistic heritage, including the dialect that forms part of daily life (Kral Citation2022, 242).

It is important to define what we mean by terms such as “language” and “dialect” as these can be problematic. Language broadly includes languages, dialects or lexicons used in the UK, whether passed down from older generations or shared within communities. Ayres-Bennett (Citation2020) describes the languages of the UK as:

English and the indigenous languages of Welsh, Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Cornish, Scots and Ulster Scots, observing that there is little legislation determining “official” languages of the UK, but that British citizenship legislation requires knowledge of English, Welsh or Scottish Gaelic.

Community languages such as Polish, Urdu and Panjabi.

Additional languages learnt in the UK, for example French and German in schools.

We adopt (1) and (2) in our definition of language heritage but not include (3) unless those languages were also inherited or shared within communities. We note that the distinction between languages and dialects is not always clear and can be a political issue in terms of nationhood, for example in relation to Ulster Scots. For the purposes of this study, we do not seek to assign categorization to the language discussed by our participants and simply report their views, acknowledging complexities and sensitivities.

We use the term “dialect” to mean the lexical choices, syntax and other discourse features (see e.g., Trudgill Citation1999) including accent, which refers to pronunciation, that constitute a variety of a language. Beal (Citation2018, 178) identifies perceptions that regional dialects constitute authentic “heritage” which is at risk from newer varieties:

Regional dialects are considered as part of the intangible heritage of the areas in which they are (or, most likely, were) spoken, while new varieties such as Multicultural London English ... or Kiezdeutsch ... emerging in superdiverse cities, are popularly dismissed as youth argots threatening to supplant older dialects.

Recent Developments

The term “heritage” is traditionally used to mean tangible heritage such as buildings and monuments. Smith (Citation2006, 11) argues that dominant hegemonic, typically Western European discourse about heritage “acts to constitute the way we think, talk and write about heritage” in what she terms “Authorised Heritage Discourse” (AHD). AHD values tangible, finite, “aesthetically pleasing” and delicate heritage over ICH. Furthermore, some researchers have observed that “white Westerners apparently have no intangible heritage” (Graham and Howard Citation2008, 9). Similarly, Smith and Waterton (Citation2008, 297) noted a perception amongst some heritage professionals that the UK has no ICH, as the tangible tends to be privileged and ICH is confined to non-Western cultures. Their findings came from interviews with English Heritage, the UK’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS Citation2017) as well as practitioners associated with the World Heritage Centre and the ICH section of UNESCO. Intangible heritage, and language specifically, may therefore be overlooked, limiting “living heritage” opportunities which would allow museums to reframe their approaches to community engagement and collaborative projects (Stefano Citation2022, 234; see also Durbach and Lixinski Citation2017, 2–3).

Both Dicks (Citation2004) and Blake draw attention to museums’ role in reconciling tensions between the value of heritage to society as a whole and its value to the communities to whom it “belongs”. According to Dicks (Citation2004, 119) “heritage production involves both salvaging the past, and staging it as a visitable experience”. She acknowledges competing claims for “local ownership of heritage”, which is both “a resource for professional interpreters and planners” and “a resource for people’s attempts to represent their own history and identities on a public stage”. Blake similarly recognizes the dual nature of heritage as both of universal value and of significance for local communities and argues that museums have a key role in addressing these concerns. Citing the UNESCO Recommendation on the Protection and Promotion of Museums and Collections, their Diversity and their Role in Society (2015), Blake asserts that “the social role of museums is understood as including help[ing] communities to face profound changes in society, including those leading to a rise in inequality and the breakdown of social ties” (UNESCO Citation1972, paragraph 17). Advocating an approach which puts local communities at the centre of efforts to safeguard their ICH, Blake calls on museums to increase their community engagement and to adopt an approach which promotes ICH as “an element of modern life” rather than merely something that ought to be documented or recorded.

However, Smith cautions that there are hidden voices within all communities and uncovering these is a particular challenge for museums; engaging with all groups as “active participants” is not necessarily straightforward (22). Smith further notes that guidance about how to achieve comprehensive inclusion is absent from the UNESCO Convention.

The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in the UK promotes the appreciation of cultural heritage. Even prior to the UK becoming a signatory to the UNESCO Convention, museums sought to explore the integration of ICH into their collections (ICOMOS Citation2018, 1). ICOMOS piloted projects with Museums of Cambridge and Peterborough which included language as a vehicle of ICH. However, it is not only museums who are working with language heritage; libraries and heritage groups around the UK can play a valuable role but face slightly different obstacles, as we explore in this paper. In some spheres, intangible heritage is seen as being an integral aspect of our cultural identity (see for example The Heritage Alliance Report Citation2019, 11, with a foreword written by the UK’s Minister for Sport, Heritage and Tourism). However, elsewhere, such as the 2016 Culture White Paper published by DCMS, it is omitted entirely despite recognition that culture is not just knowing lists of artworks and architecture. It is similarly neglected in DCMS’s 2017 Heritage Statement.

Several researchers have observed a shift in the approach taken by museums over the last two to three decades. Dicks (Citation2004, 120) argues that there has been a “recent turn to the past” representing a clear “second-wave of heritage-mania” which rejects the elitist orientation of earlier public museums and aims to display objects more accessibly. She also links social constructionist approaches to identity (which reject fixed inherited roles) to the advent of “an age of identity” where “[g]aining a sense of one’s past becomes integral to this project of claiming an identity for the self” (ibid., 121). These shifts from high to “ordinary” culture and towards an identity-centric approach are reflected in a “first-person focus in vernacular heritage” (ibid., 125). Beal (Citation2018, 177) comments that some of the shift away from a top-down presentation of displays in museums towards interactivity coincides with the impact agenda in academia. She notes various collaborations between universities and museums (for example Newcastle University’s involvement with Beamish Museum and Newcastle Discovery Museum), suggesting that the need to prove research impact has led to greater engagement between Higher Education institutes, local museums and the general public (see also the Mendoza Review Citation2017). While there may be multiple reasons for the shift from top-down to bottom-up approaches, such principles are evident in many museums’ language and other forms of ICH exhibitions.

Language Heritage Around the World

This shift is evident beyond the UK. Burden explains that the Afrikaans Language Museum (South Africa) balances the dual aims of presenting ICH in an engaging way and well-researched, educational manner. This involved using intangible heritage to contextualize tangible heritage but also working with, historically neglected, language in its own right, for example through song, customs and language. The museum invites visitor contributions through interactive whiteboards, thus bridging distance between the language displayed in the museum and the language in community use. A similar approach was also adopted in Museum Catharijne Convent in the Netherlands where people could enter on a website their experiences of the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage and encounters with pilgrims. Ordinary people were positioned as “experience experts” which according to van Eijnatten and de Nood (Citation2018, 101) was key to the successful redevelopment of the museum as such involvement at an early stage led to them becoming project ambassadors. The researchers also observed that the link between contemporary experience and historical artefacts enhanced visitor experience.

In 2020, a seminal collection edited by Margaret J.-M. Sönmez, Maia Wellington Gahtan and Nadia Cannata (Citation2020) was published entitled Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In this volume, researchers and practitioners present case studies of how they have worked with language heritage in museums around the world. Contributors report a range of means of inviting visitor participation which engages the public and produces new linguistic content for the museums, thus playing a role in collecting and revitalizing varieties, celebrating diversity and reducing stigma associated with some dialects. Such initiatives include encouraging participation in Dialect Karaoke where visitors are encouraged to record stories in local dialects (Lithuanian Hearth Museum, Zabarskaite Citation2020) and inviting visitors to provide “live” evaluations and perceptions of accents, words and grammar spoken by others to draw attention to linguistic biases (English Pop-Up Museum, UK, Ayres-Bennett Citation2020).

Several authors refer to the need for language heritage projects to extend beyond the walls of museums. Ayres-Bennett (Citation2020) notes that a key benefit of the pop-up museum of English she curated was that it was highly mobile and visited schools and youth clubs, for example, to encourage more young people to engage with language learning. It was also an important first step towards a permanent collection when funds were not yet available (for a proposed physical English language museum based in Winchester, UK). Zabarskaite (Citation2020) reports a similar call for portable exhibits from the Lithuanian Hearth Museum. Likewise, the Canadian Language Museum (Gold Citation2020), which seeks to represent three groups of language: English and French, indigenous languages and the languages of recent immigrants, found that portable exhibits, curated by MA Museum Studies students, provided a cost-effective means of taking language heritage into communities.

Materials and Methods

To answer the research questions listed in the introduction, we conducted a survey using JISC Online Surveys and carried out semi-structured interviews. Participants had the opportunity to participate anonymously or on an identifiable basis. The survey incorporated a mixture of multiple-choice questions and free text questions ensuring that we could: (a) collate quantitative data to measure, for example, how many museums work with language heritage, which types of heritage they worked with and what they felt were the greatest challenges to the sector; and (b) offer respondents the opportunity to raise issues we might not have probed in the multiple-choice questions and to provide detail about their own experiences and potential case studies (see Appendices for the survey and interview questions). The authors and our contacts shared the survey link on social media, and we also used the Arts Council’s List of Museums to send it directly to over 300 museums and heritage organizations over a period of three months from February to May 2022. We received 32 detailed responses. The respondents were therefore self-selecting and most had some interest, however limited, in linguistic heritage. Organizations who did not work with language heritage were probably unlikely to respond. Our findings thus present an impressionistic snapshot of the work being conducted by respondents.

The respondents covered a broad geographic area across England, Scotland and Northern Ireland, but we had no responses from Wales. Of the 32 survey respondents, 84% worked in museums, 13% in national heritage organizations and the remainder in charities, heritage groups, local authorities, historic properties and libraries. There was some overlap as, for example, some museums are run by charities or a local authority. Most respondents were employees or directors of their organizations, but we also heard from academics, trustees and volunteers.

To analyse free text responses, we exported text into a qualitative analysis software programme, NVivo. The responses were coded inductively based on themes and patterns that emerged from the data and these themes were combined and compared, before being revisited to produce an agreed set of coding. Themes and sub-themes were included in a codebook which informed the focus and structure of our analysis.

We included a question asking participants if they would be willing to take part in a detailed follow-up interview. A member of the research team contacted those who answered affirmatively, and one further participant was recruited through an email request which led to a referral to the interviewee. We encountered some problems scheduling interviews due to absences and staff shortages in the heritage sector caused by Covid-19. Nevertheless, nine semi-structured interviews were scheduled, each lasting between 35 and 75 min. The interviews were conducted online, recorded and transcribed. All transcripts were then imported into NVivo where they were coded in the same manner as the free text responses for the survey and the codebook was updated accordingly.

Our analysis focuses on the research questions and the themes and patterns identified through NVivo coding. Below are the most commonly occurring themes and sub-themes, but we also consider less frequent themes to ensure that as many voices as possible are included as these tend to highlight specific and hidden issues, for example on access and inclusion, collaboration and future plans.

Results and Discussion

How are museums and heritage organizations around the UK currently working with language heritage?

A small minority of 4% of respondents, working in libraries and heritage organizations, reported that their organization focused on language; 34% of respondents reported that they worked with language in one way or another. Of these, 38% worked with oral traditions (such as storytelling and singing), 85% with oral heritage/history and 94% with archives, including transcripts and sound recordings. Significantly, 97% worked with artefacts/objects demonstrating the prevalence of tangible heritage in the work of their organizations. Respondents worked with various aspects of language. 46% worked with minority languages of the UK (e.g., Irish, Scottish Gaelic), 55% worked with dialects and 27% worked with lexicons specific to communities or occupations (these figures reflect that some organizations worked with multiple aspects). Although two-thirds of respondents said that they did not currently work with language heritage, 94% felt that museums had a role to play in safeguarding language heritage and 97% felt that heritage groups or societies do too (81% felt local communities had a role to play and 78% felt that universities did).

Our findings indicate a mismatch between participants’ assessments that language heritage is something that their organizations should be safeguarding and their reports that most were not involved in this kind of work. This requires closer scrutiny to identify the reasons for the difference between theory and practice. Participants indicated that the main barriers to doing language heritage work were lack of staff (75%), funding (75%) and expertise (71%). Free text responses to the survey and responses given in interviews clarified that some participants felt they required considerable extra support and information to enable them to work with language. Several participants called for guidance including:

… practical examples of how to do so. (Survey 18)

- Guidance on how to appropriately acquisition or record intangible heritage, such as language, and how best to safeguard it. (Survey 16)

… some sort of framework, to get some guidance … I just think it would be extremely helpful if there was something there to help scope and give guidelines, funding for that kind of project. (Interview 5)

… books of practical “how to do” things as a museology and how to work in partnership are few and far between. (Interview 1)

I don't think anybody is looking at language as a specific research project. It's that they're coming across language and they're having to work it out from there. (Interview 1)

Dialect is often used in temporary displays, through e.g., artefact captions, graphics captions, in interviews, activity sessions, publications. It is invariably strand of content that's relevant, rather than an overt topic as such. (Survey 20)

The display is usually more seen as being what the subject is about, as opposed to a display about language. So if the linguistic term, maybe would add a bit of extra colour, or if maybe there isn't much that we can say in the display and we feel that we've got to co-opt all the information at our fingertips, then we will co-opt the local word. (Interview 4)

We want to capture those volunteers’ experiences of working in particular industries. Most of our volunteers are in the 60 plus age group, so they've got first-hand experience of working in a lot of those industries. So we want to collect that contextual information as well. But we are also finding, and this was an enlightenment to me because I don't have that background, in the course of developing that programme, there are specific vocabularies that relate to individual industries. They’re in some areas quite extensive and unbelievably opaque. If you start looking at textile production, for instance and in particular worsted production, it's got an entire vocabulary. (Interview 5)

The study, supplemented by desk-based research, elicited several detailed examples of current work with language heritage. These are presented here as case studies illustrating innovative and diverse approaches to engaging with languages, lexicons and dialect.

Case Studies of Language Heritage Work

A: The Word, South Tyneside, England

The Word, the National Centre for the Written Word, is South Tyneside Council’s cultural venue which includes a public library, storytelling space and exhibition venues in the North East of England. It has developed initiatives to encourage visitor and community participation in language. The Lost Dialects project focusing on North East dialect took place between 2016 and 2018 and aimed to “reignite an interest in the use of words that were used in local shipyards, mines, in street games and social gatherings and are at risk of being lost forever”. According to Julia Robinson, Principal Librarian for South Tyneside Council, who we interviewed as part of this study, the project leaders were aware that focusing on such a masculine, workplace community would neglect the language of other sections of the population and would not necessarily have wider appeal. So they were decided to incorporate domestic, cooking and playground language into the exhibition.

One interactive installation encouraged visitors to “donate” words, including dialect, by writing them on luggage tags which were strung up across the space. This yielded over 2,400 words which were ultimately used to produce a dialect dictionary known as the Word Bank of Lost Dialects, displayed as part of an exhibition by two artists, Jane Glennie and Robert Good, allowing visitors to take rubbings of their chosen Geordie (the colloquial term used to refer to Tyneside) words. The Lost Dialects exhibition also included local language quizzes, films about cooking popular dishes, traditional children’s skipping songs and a jukebox of North East songs performed by local musicians.

A further exhibition held in 2022 was Our Words, part of the Season of “Northern Conversations” programme. This involved working with Erin Dickson, a local artist who produced a map and illustrations of what it means to be part of the South Shields community, and Lizzie Lovejoy, an illustrator and poet from the North East who engaged with local people about what it means to be “northern”, stereotypes, accent and the fear of being misunderstood. Robinson emphasized that the Our Words exhibition focused on current language use and variation “not always looking back” because, “obviously, language is a living thing”. The Our Words project leaders sought to include all communities:

… obviously, not everyone who lives in the North East has been born in the North East, so to try and make it inclusive and not be saying, “You must be a Geordie to get something out of that”, it's been something we've had in mind as well. We'll try to phrase it like … “What does it mean to you to live in the North?” Not necessarily to be from the North?

B. Dorset Museum, Dorchester, England

Dorset Museum, located in Dorchester, England, has collections of archaeology and natural history as well as works by Thomas Hardy and William Barnes, local writers and poets who used the Dorset dialect. Its literary collection includes objects, such as clothing, as well as original manuscripts, belonging to the writers. There are a range of interactive displays and community engagement activities which seek to bring to life the Dorset dialect used by Hardy, Barnes and others associated with the local area. The Museum has collaborated with academics at University of Exeter and literary societies to inform their collections, as well as various players and storytellers to celebrate language through dialect performances and exhibitions. They provide opportunities for visitors to hear, speak and read Dorset dialect. They have installed a magnetic wall of dialect words which visitors are encouraged to use to form their own phrases, sentences and poems using the language of Hardy’s works.

C. Ulster Folk Museum, Northern Ireland

The Ulster Folk Museum in Northern Ireland has developed an educational Irish language trail, called the “Cúl Trá-il” which is audio-guided in either Irish or English. The trail uses streets and houses around the museum as prompts “to demonstrate authentic links between language, buildings, people and places” (Ulster Folk Museum Citation2022). A local language and culture-based trail in Ulster Scots is under development.

D. The British Library, London, England

The British Library has amassed extensive collections of spoken English over recent decades. Its archives include deposits from projects such as BBC Voices (2004–2005) with people talking about language, recorded by regions and nations around the UK using linguistic methodology provided by researchers at the University of Leeds. The British Library website gives access to sound archives, including excerpts of recordings collected as part of the Survey of English Dialects collected by the University of Leeds between 1950 and 1961. The University of Leeds’s Dialect and Heritage project is working with five museums to build a snapshot of dialect in England.

E. Lost Words, Nottingham, UK

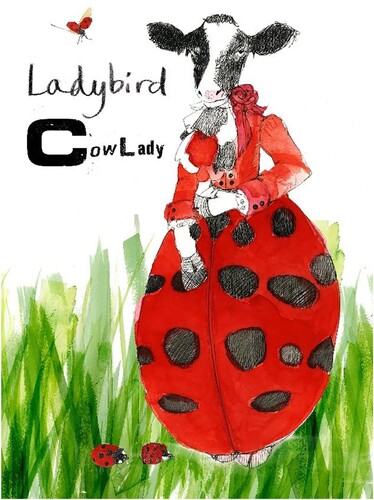

Nottingham Trent University’s Lost Words project engaged with local partners including local authorities, an artist and a poet to collect and celebrate Nottinghamshire dialect words, working with local schoolchildren to write poetry using dialect, and to exhibit words and illustrations in libraries. Extensive work has also been ongoing to document local “pit talk”, the specialized lexicon of local coal miners (Braber Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2022 as well as Braber, Ashmore, and Harrison Citation2017) ().

| (2) | What challenges and barriers have they encountered and how are they working to overcome these? | ||||

Figure 1. Example of illustrated dialect word “cowlady” used as stimulus for schoolchildren’s poetry workshop and library exhibitions (Lost Words, Nottinghamshire) (illustration by Hannah Sawtell).

As noted above, survey participants reported that the main barriers to doing language heritage work were lack of funding, staff and expertise. To understand these obstacles and how they can be addressed, we probed further in open ended questions in the survey and in the semi-structured interviews.

Funding, Staffing, Expertise

Several museums reported that they were constantly required to apply for funding for new projects. One volunteer-operated museum that was just beginning to think about working with heritage language associated with industry reported that they needed more help “marrying up” how to conduct a project with how to fund it: “I just think it would be extremely helpful if it was something there to help scope and give guidelines on funding for that kind of project” (Interview 5). They also felt that: “The initial thought is that we really do not have the skills to make an awful lot of sense of language heritage at this stage”. A participant from another volunteer-run historical society reported that success in obtaining funding was very much dependent on her own expertise of bid-writing which came from her pre-retirement career (Interview 8); other organizations without access to such skills require support in this area.

Organizations of all sizes reported staffing issues. One local authority-controlled museum stated they lacked resources to work with tangible heritage, which was positioned as the priority, with ICH and language heritage seen as further down the priority list and areas “which would involve more thinking” (Survey 11). A county museum representative reported that staff had very broad responsibilities. Therefore, producing new exhibitions was a challenge for staff resource because “it takes a little bit more time to research” new projects (Interview 4). Several museums reported being understaffed, some due to Covid-19 illness and isolation, but many suffered more long-term employee and volunteer shortages. One large museum reported having historic staffing issues which meant that existing experience of language heritage work had dwindled:

I think I’ve been pleasantly surprised with a vast collection we have and it’s just a huge challenge to try and utilise them because there's a huge amount of knowledge that has been lost through staff who weren’t replaced. (Interview 7)

I think what I see with early career curators is their job is really frustrating because it isn't that they don't know what to do – they do! But it's very hard for them to have the impact that they should have … . I think very good ideas often get squashed before they have chance to flourish a little bit. But people are like, “Oh God, I tried that 20 years ago. It doesn't work!”. And actually, you know, it's very crushing I think. So you do see great things and you do see great projects, but I think it's quite hard to do different things. (Interview 1)

The Trust don't let me do anything really. The curator, she thinks that efforts to decolonise are too “gung-ho”, which is a stupid turn of phrase but okay, and she thinks that I should have a more rounded view of decolonisation and not want to tear everything down. And I'm not trying to tear everything down. I'm trying to give a more rounded view, just not to her perspective. So those are definite barriers. (Interview 3)

Challenges of Working with Linguistic Variation

Seven participants queried how to “pitch” language exhibitions to appeal to a range of audiences, including people not associated with the particular language heritage. They were concerned that language heritage might seem dull or irrelevant. For example, a participant from an industrial heritage museum commented that:

We have industry experts who have could compile a glossary for us and that's a start, but actually the problem arises … of finding the cut-off point between what engages people's interests and what they find overwhelming. Whereas we within the museum might find those linguistic differences and dimensions to things very interesting, you're going to find out that level where we can look at those things without boring people. (Interview 5)

I've got a teenager and she was with her friend and I showed them local dialect writing and they just couldn't make head nor tail of it. They thought it was interesting, but “what is he talking about?”. So, I think what's a real challenge is communicating to different audiences in a kind of clear way. (Interview 6)

I think what the library service brought to the whole project was to make sure there was something for everyone in it in the way that a public library is something for everyone and make it accessible and it make it a bit of fun. I think it could have really become a quite serious, historical project which would have been an interest to the miners but no one beyond that community if the library service hadn't got involved in that way. (Interview 9)

… as time is going on, there's been much more of a mix or a flattening out of the common denominator of the youngest speaker … so it's really people from their 50s and older who have a fairly strong dialect either in accent or in lexicon or in grammar. (Interview 4)

Another professional working with large archives suggested that it would be worthwhile to monitor language change via “a possible project timed every 10 years or so to capture language and dialect. As more people move around the country local dialects may be diluted and will change” (Survey 30). A heritage organization volunteer from a different island commented on the challenges of running Scottish Gaelic-only events:

… there is sometimes an issue when monolingual individuals who settle here, “demand” that English is spoken, although the event has been clearly billed as Gaelic only. Their failure to understand the ways these behaviours are replicating Gaelic's history of oppression and exclusion, and how these demands reinforce the dominant language can seem peremptory and colonising. (Survey 26)

… attempting to foster the dialect through an “authorised” group guidance is, but needn't be, problematical. To identify – and thus promote – a dialect, having recognised orthography and definition is vital. But umpteen enthusiasts over the decades have shown that folk refuse to conform, taking a “that's not how we say it”, or “how I spell it”, attitude. This absorbs time to little gain. (Survey 20)

Each island has a very different pronunciation and idioms are very different. Vocabulary is different because all these islands still – the older people, they're a bit like labs they've not widened their contacts so much. And they were schooled pre-television so their expression is rich, diverse and accurate to place. (Interview 8)

Several of the participants suggested bringing together heritage sector professionals, academics and interested members of the public to share ideas, find ways through problems and to develop innovative approaches. One participant explained that work was already underway to develop such spaces and to work through challenges associated with linguistic heritage and sectarianism:

… it was identified by our directors that we should be contributing proactively to that, towards societal well-being. And so we’re very keen to put ourselves in the middle of that and to do so in a respectful way and to be proactive to create opportunities to learn, to challenge preconceptions and maybe provide a forum where people can learn about things that they might not otherwise. (Interview 7)

| (3) | How do museums and heritage organizations expect to work with language heritage in the future? | ||||

Over a third of participants indicated that they would like to improve documentation of linguistic varieties, including dialect and community-specific lexicons, particularly through building archives and exhibitions of audio-visual materials. For example, a respondent commented that, “Language is becoming standardized. This is inevitable because of the media. It's essential that we record local people who still retain regional variations in their speech and vocabulary”. Several participants advocated developing better links with oral history societies and archives to collect linguistic and cultural heritage.

There were also calls to make archives more accessible to the public, particularly through websites and to present linguistic heritage alongside tangible heritage wherever possible inside museums. There was also considerable awareness of the need to include all communities in projects aiming to capture and safeguard the UK’s language heritage. This informed many of their plans for future initiatives. One curator responsible for a large archive of English language and dialect commented that although archives are increasingly shifting from rural to more urban focus:

We are aware that our collections don't represent as well things like minority ethnic community varieties of English, although we're trying to plug those gaps … I would hope that any if there were ever a future dialect survey, it would both be of the English spoken by established communities here, but also the English that is spoken by other varieties. (Interview 2)

I think it would be really nice to be able to hear the voices of people who are being depicted and learn about what terms and languages like, even in the sort of queer community, there's quite a lot of, like, hidden queer histories in the organisation. (Interview 3)

Conclusion

ICH can bring tangible heritage to life and give objects meaning and enhance the dynamic of cultural heritage. However, only recently have some museums and other organizations started to display language. Participants in our study voiced concerns that language heritage can be hard to encapsulate. Nonetheless, the study found a great deal of good practice which involved high levels of community engagement and innovative approaches. Participants reported examples of collaborative work between museums, academics, heritage organizations, local authorities and artists. Projects which had the most positive impact involved high levels of interactivity and community engagement. These initiatives focused on sharing and reinvigorating community language rather than trying to reinstate the past.

However, there are clear gaps in the availability of expertise, staff and funds. Furthermore, participants identified difficulties in working out how to pitch language heritage and ensure that it is accessible and relevant. It also requires a flexible and nuanced approach to deal with sensitive issues. Reductions in funding are likely to become even more important in coming years (Museums Association Citation2023).

Museums interested in working with language heritage, but lacking knowledge and expertise, require support and guidance to navigate complex issues and a difficult funding landscape. Where should this provision come from? It could come from a national ICH policy, avoiding the common hierarchy of cultural practices. Scotland has made considerable progress in listing and organizing ICH alongside tangible heritage on the ICH Scotland Wiki, even though no single agency is leading or coordinating such efforts in Scotland. However, ICH has not been recorded in a central register in any of the other UK nations, although work is taking place in Wales in relation to ICH and the Welsh language, including via the National Museums of Wales and the National Eisteddford which celebrates Welsh arts, language and culture. Our participants had mixed feelings about the merits of UK-wide policy. Some participants indicated that a UK government-level approach or framework might circumvent tensions between groups with different visions for the future, particularly in relation to Scottish and Irish heritage languages. Others felt that governmental agencies in Scotland and Northern Ireland should be providing stronger leadership. Most respondents in England advocated a practitioner-based approach involving funding bodies, museum associations and other heritage professionals to produce guidance.

Meanwhile, participants largely agreed that knowledge-sharing, through visiting other museums, attending conferences and meetings and publishing guides and case studies, would allow them to learn from each other’s good practice. In light of this, our project team organized a roundtable event to bring together practitioners, policymakers, academics and others with experience or interest in working with this field. The event helped to raise awareness and encourage stakeholders to come together to identify paths to safeguarding the UK’s language heritage. Ongoing stakeholder events will continue this. An initial options paper has been produced to showcase examples of work taking place in and around Nottingham and Nottinghamshire in the UK (Braber, Howard, and Pickford Citation2023). Finally, the UK’s ratification of the UNESCO Convention and recent changes to the UK government indicate that now is the time to bring these issues to the fore and develop a coherent strategy to safeguard the UK’s diverse language heritage.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the museum professionals who took part in our surveys and interviews.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalie Braber

Natalie Braber is Professor of Linguistics at Nottingham Trent University. Her research specialises in language variation, 'pit talk', language as heritage, accent discrimination and ear witness testimony.

Victoria Howard

Victoria Howard is a postdoctoral researcher in sociolinguistics at University of Nottingham. She specialises in investigating language, communication and identities in professional settings. Between 2021-2023 she worked at Nottingham Trent University conducting research into language as intangible heritage in the UK.

References

- Ayres-Bennett, Wendy. 2020. “Celebrating Languages and Multilingualism in the UK and Beyond: A Pop-Up Museum of Modern Languages for the UK.” In Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Margaret J. -M. Sönmez, Maia W. Gahtan, and Nadia Cannata Salomone, 188–205. Oxford: Routledge.

- Beal, Joan. 2018. “Dialect as Heritage.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Superdiversity, edited by A. Creese, and A. Blackledge, 165–180. Oxford: Routledge.

- Bialostocka, O. 2017. “Inhabiting a Language: Linguistic Interactions as a Living Repository for Intangible Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Intangible History 12:18–26.

- Braber, Natalie. 2018a. “Pit Talk: The Secret Coal Mine Language That’s Not Going Extinct.” The Conversation, September 6. https://theconversation.com/pit-talk-the-secret-coal-mine-language-thats-now-going-extinct-96594

- Braber, Natalie. 2018b. “Pit Talk in the East Midlands.” In Sociolinguistics in England, edited by N. Braber, and S. Jansen, 243–274. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Braber, Natalie. 2022. Lexical Variation in an East Midlands Mining Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Braber, Natalie, C. Ashmore, and S. Harrison. 2017. Pit Talk of the East Midlands. Sheffield: Bradwell Books.

- Braber, Natalie, and Victoria Howard. 2023. “Safeguarding Language as Intangible Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Intangible History 18:145–158.

- Braber, Natalie, Victoria Howard, and Rich Pickford. 2023. A Place-Based Perspective on Intangible Heritage Benefits of Language and Dialect. https://www.ntu.ac.uk/about-us/community/nottingham-civic-exchange/publications/reports

- Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. 2017. Heritage Statement. 5th December.

- Dicks, Bella. 2004. Culture on Display. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Durbach, Andrea, and Lucas Lixinski. 2017. “Introduction.” In Heritage, Culture and Rights: Challenging Legal Discourses, edited by Andrea Durbach, and Lucas Lixinski, 1–7. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gahtan, Maia Wellington, Nadia Cannata, and Margaret J.-M. Sönmez. 2020. “Introduction.” In Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Margaret J -M Sönmez, Maia W Gahtan, and Nadia Cannata Salomone, 1–31. Oxford: Routledge.

- Gibson, Mandy, et al. 2021. “Does Community Cultural Connectedness Reduce the Influence of Area Disadvantage on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Young Peoples’ Suicide?” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 45 (6): 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13164.

- Gold, Elaine. 2020. “The Canadian Language Museum: Developing Travelling Exhibits.” In Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Margaret J -M Sönmez, Maia W Gahtan, and Nadia Cannata Salomone, 134–152. Oxford: Routledge.

- Graham, Brian, and Peter Howard. 2008. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. London: Routledge.

- The Heritage Alliance. 2019. Inspiring Creativity, Heritage & Creative Industries.

- ICH Scotland. https://ichscotland.org/wiki/shetland-dialect. Last accessed: 14 November 2022.

- ICOMOS. 2018. Exploring Intangible Cultural Heritage in Museum Contexts. A Pilot Project.

- Kral, Inge. 2022. “Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Book Review.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 17:242–243.

- Mendoza, Neil. 2017. The Mendoza Review: An Independent Review of Museums in England.

- Museums Association. 2023. Museums at Risk as Local Authority Funding Crisis Intensifies. https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2023/09/museums-at-risk-as-local-authority-funding-crisis-intensifies/#

- Sarma, Rashmirekha. 2015. “Disappearing Dialect: The Idu-Mishmi Language of Arunachal Pradesh (India).” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 10: 61–72.

- Smith, Laurajane. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Emma Waterton. 2008. “The Envy of the World?: Intangible Heritage in England.” In Intangible Heritage, edited by L. Smith, and N. Akagawa, 289–302. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884973

- Sönmez, Margaret J.-M., Maia Wellington Gahtan, and Nadia Cannata. 2020. Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Oxford: Routledge.

- Stefano, Michelle L. 2022. “Renewing Museum Meanings and Action with Intangible Cultural Heritage.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 17:234–238.

- Trudgill, Peter. 1999. The Dialects of England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Ulster Folk Museum. 2022. ‘Cúl Trá-il’. Last accessed 13 December 2022.

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Paris, 1972.

- van Eijnatten, Joris, and Marije de Nood. 2018. “Shared Stories: Narratives Linking the Tangible and Intangible in Museums.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 13:93–110.

- Zabarskaite, Jolanta. 2020. “The Lithuanian Hearth Museum.” In Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Margaret J.-M. Sönmez, Maia W. Gahtan, and Nadia Cannata Salomone, 51–66. Oxford: Routledge.

Appendices

1: Survey questions [the survey itself included examples and additional text boxes where needed]

Where is the organisation located?

How would you describe the type of organisation?

Is the organisation dedicated to: local area; region; nation; industry/occupation(s); rural area; urban area; arts/crafts; conflict; language; people/community; science; transport; other.

How would you describe your role at the organisation?

Which aspects of heritage does your organisation currently work with, collect or safeguard: archives; artefacts/objects; festive events; historical industrial or built environment; industry/trade; knowledge and practices concerning nature and universe; knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts; landscapes/natural environments; language; literature/books/written word; military history/heritage; oral histories; oral traditions; parks/open spaces; people’s/community culture; performing arts; religious history/heritage; rituals; science; other.

Which aspects of language does the organisation currently work with, collect or safeguard: minority language(s) of the UK; a language that is not an official language of the UK; dialect(s) of a UK language; lexicon/vocabulary specific to a region; lexicon specific to an industry/trade; other.

Which language(s), dialect(s), variety or element(s) of language does the organisation currently work with, collect or safeguard?

Please describe any programmes/measures in place to work with, collect or safeguard language heritage in your organisation.

Which programmes/measures do you think work well to safeguard language heritage?

Which programmes/measures aiming to safeguard language heritage do you think work less well?

Which of the following aspects of language heritage do you think should be safeguarded in the UK: minority language(s) of the UK; a language that is not an official language of the UK; dialect(s) of a UK language; lexicon/vocabulary specific to a region; lexicon specific to an industry/trade; don’t know.

Are there any other aspects of language heritage that you think should be safeguarded in the UK?

How could this be achieved?

Which organisations/institutions do you think should be involved in safeguarding language heritage: museums; local communities; heritage groups/societies; UK government; local authority/council; devolved UK governments; universities; schools; charities; international counterparts; other.

Challenges and obstacles: this question asked about potential obstacles including acquisition policy, time, cost and to what extent they agreed these were challenges.

Are you aware of any other challenges?

Please outline any internal or external support the organisation would need to overcome any challenges or obstacles you have identified.

Do you have any suggestions about how museums, heritage organisations, governments and any other bodies or institutions can help safeguard language as intangible cultural heritage?

Do you have any other comments?

2: Interview questions

Confirmation of consent and completion of consent form.

Open questions about interviewee’s role and organisation.

Where is the organisation located?

Could you tell me a bit about the organisation? What type of organisation is it? (museum, historic property etc)

▪ If museum, what type? i.e., who owned and funded it?

▪ What is the museum focused upon? (local area, industry, transport etc)

Please could you describe your role there?

When we talk about “language heritage”, what does that mean to you?

What does it mean within the context of your organisation?

Do you think it’s important to safeguard communities’ linguistic heritage?

What does safeguarding language heritage look like? What does it involve?

Which aspects of heritage are currently safeguarded by the organisation? Does this include intangible heritage? Language? If so, how?

What currently works well in the organisation’s approach to safeguarding language heritage?

What works less well?

Could you tell me about any projects or exhibitions relating to language heritage? Which parties have been involved?

Have you/your organisation encountered any obstacles to effectively safeguarding language heritage?

Whose responsibility is it to safeguard language heritage? Is it government / heritage sector org/ individual museums / national museums / local communities?

Who else should be involved and how?

What needs to happen for them to be able to do this? Is any further support required by the organisation/sector?

Do you/your organisation have any plans, ideas, innovations for safeguarding language heritage in the future?