ABSTRACT

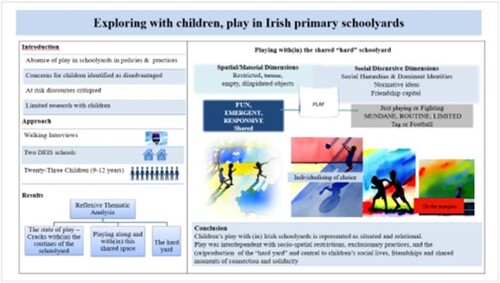

Children’s play in Irish schoolyards remains neglected in educational policies and practices despite government commitments to inclusive schools and children’s rights. There is a dearth of research on children’s perspectives of play, criticisms of ‘at risk’ discourses underpinning concerns for certain children’s play rights, and studies identifying exclusion within Irish schoolyards, particularly for children with minoritized identities. This inquiry informed by the theory of practice architectures used walking interviews to explore with twenty-three children their play practices in two Irish primary schools identified as disadvantaged. Analysis of the interviews generated three themes: (1) the state of play – cracks with(in) the routines of the schoolyard, (2) playing along and with(in) this shared space and (3) the hard yard. This inquiry contributes to understandings of children’s play with(in) Irish schoolyards, as socially situated practices with contrasting representations of play as habitual and emerging. Play was central to children’s social lives, identities, and friendships and interrelated with diverse constraints, exclusionary practices, and the (re)production of the ‘hard yard’. While mattering most children’s experiences of significant constraints and inequities, this inquiry also highlighted the transformative possibilities generated within play to create shared possibilities for individual and collective flourishing.

Introduction

Despite Ireland’s commitments to children’s rights including a national play policy, reminding schools of their Article 31 obligations, there is scant attention within educational policies or practices to children’s play in schoolyards (Bergin et al., Citation2023; National Children’s Office [NCO], Citation2004). This neglects interdisciplinary research on the importance of play in children’s lives and cross-sectoral policy concerns regarding exclusion within schoolyards, particularly for children with minoritized identities (Department of Education and Skills [DES], Citation2017; Department of Education [DOE], Citation2022; NCO, Citation2004; Russell, Citation2021). To progress practices, recommendations highlight the need to generate a greater understanding of the complex interrelationships between children, play, and contextual factors, emphasising the limited research from children’s perspectives and on social dimensions, particularly intersectional inequities (Baines & Blatchford, Citation2023; Clements & Harding, Citation2022; Russell, Citation2021). Informed by critical play scholarship and the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis, Citation2019) this inquiry, therefore, aims to explore with children their play in Irish schoolyards, identified as disadvantaged.

Children’s play in schoolyards

The schoolyard is represented as atypical, in affording regular opportunities to play with peers due to increasing societal restrictions (Baines & Blatchford, Citation2023; McKendrick, Citation2019). However, as Lester et al. (Citation2019) discuss tensions exist between the educational focus of schools and the promotion of play as ‘initiated, controlled and structured by children themselves’ (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [UNCRC], Citation2013, p. 1). Studies have shed light on how adults’ normative ideas and lack of value on play, intersect with individualistic practices, regulating and restricting space, time, and permission for play in schoolyards (Baines & Blatchford, Citation2023; Bergin et al., Citation2023; Rönnlund, Citation2017).

Russell’s (Citation2021) review of the research on outdoor play in schoolyards, underlines how children’s diverse, ideas, experiences, and values on play, differ not only from adults. Children’s play has been conceptualised as enacting their culture, with studies describing how children identify a wide range of preferred activities as play; value most having fun, being with friends, and choosing what they want to do; draw on ‘real’ and ‘digital’ worlds, appropriate spaces and objects, and seek out risk and challenge to create play (Baines & Blatchford, Citation2023; Beresin, Citation2010; Clements & Harding, Citation2022). Research also highlights play in schoolyards as instrumental to children’s sense of belonging in school (Russell, Citation2021). Although limited, studies have generated insights into inclusion in schoolyards as requiring on-going negotiations of hierarchical social structures that intersect with children’s abilities and racialised, gendered and classed identities (Kustatscher, Citation2017; Lodewyk et al., Citation2020; Massey et al., Citation2020; Ringrose & Renold, Citation2010). An overall absence of knowledge on the social processes within play, however, has been identified in recent systematic reviews, particularly from the perspectives of children with minoritised identities and in middle childhood (Massey et al., Citation2020; Russell, Citation2021).

The Irish context

There is scarce research also exploring with children their play in Irish schoolyards, however, as in other contexts, play and being with friends are described as the most valued aspect of school (Blake et al., Citation2018; Devine et al., Citation2020; O’Rourke et al., Citation2017). In Ireland, children’s play in schoolyards usually occurs outdoors during mandated daily 30-minute ‘break times’, divided into short morning (10/15 mins) and longer afternoon breaks (20/30 mins) (Devine et al., Citation2020). Although data are limited, Irish schoolyards are described as mostly hard surfaced, lacking play value, funding, or equipment, with over a quarter of schools reporting insufficient space for play (Devine et al., Citation2020; Fahy et al., Citation2020; Marron, Citation2008; NCO, Citation2004). A lack of pedagogical guidance adds to the challenge of progressing play rights, with school requirements focused on safety and more recently instrumental initiatives (Marron, Citation2008; Walsh & Fallon, Citation2021).

This contrasts with the focus within Irish inclusive educational policies on children’s rights and whole-school approaches that create welcoming spaces and foster respect, acceptance and belonging (DES, Citation2017; DOE, Citation2022; National Council for Special Education, Citation2011). Irish inclusive educational policies primarily address disability with a separate social inclusion strategy outlined in the DEIS plan (Department of Education, Citation2017). DEIS draws on data gathered using a deprivation index (variables include parents’ education levels, employment status and housing) to provide additional educational supports to schools with a high proportion of students identified as disadvantaged (273 primary schools out of approximately 3300 nationally, Department of Education, Citation2023).

Reflecting wider research on the dilemmas of inclusion, the DEIS programme is the subject of on-going debate due to concerns about deficit-focused practices, a higher proportion of students from minoritized communities, lower achievement rates, increased bullying and conflict and the reproduction of societal inequities (Ainscow, Citation2020; Fleming & Harford, Citation2021; Ní Dhuinn & Keane, Citation2021). Significantly, interdisciplinary studies highlight the Irish schoolyard as a place of exclusion, more so for children with minoritized identities and disabled children, who describe bullying, racism, restricted physical activity opportunities, and a lack of meaningful peer relationships (Blake et al., Citation2018; D’Urso et al., Citation2021; Fahy et al., Citation2020; Fennell, Citation2021; Ní Dhuinn & Keane, Citation2021; Scholtz & Gilligan, Citation2017). The Irish play policy also articulates specific concerns regarding the social inclusion of children, identified as disadvantaged (NCO, Citation2004). However, schoolyards and play remain absent from inclusive school policies and guidelines, including the new action plan on bullying (DOE, Citation2022). The complex challenges within schoolyards and inclusive policies and practices in an Irish context resonate with recent scholarship on play, critiquing ‘at risk’ discourses and practices as situating the ‘problem’ with the child, while neglecting systemic and societal injustices (Gerlach & Browne, Citation2021; Kustatscher, Citation2017; Lester et al., Citation2019; Russell, Citation2021).

Theoretical approach and research aim

Drawing on critical and post-humanist theories, inter-disciplinary play scholarship (re)conceptualises play as interdependent within unique contexts, processes, and relationships (Gerlach & Browne, Citation2021; Lester et al., Citation2019; Lodewyk et al., Citation2020; Woodyer et al., Citation2016). A critical research and practice approach is advocated that interrogates normative assumptions and challenges inequities to focus on children’s perspectives and the conditions that interrelate with play possibilities (Kaukko et al., Citation2022; Lester et al., Citation2019; Russell et al., Citation2023). Aligning with this agenda, the theory of practice architectures frames everyday activities as socially established practices constituted in certain doings (actions), sayings (language, ideas, discourses) and relatings (how people relate to one another and the world) (Mahon et al., Citation2017). Of most interest, Kemmis (Citation2019) explains is to understand how practices happen in certain ways in certain contexts, enabled and constrained by diverse cultural-discursive, material-economic, and social-political arrangements.

This inquiry is part of a wider multi-study project informed by critical occupational theories exploring multiple perspectives of play in Irish schoolyards to better understand the conditions that make play possible and generate practice possibilities. To address the tension between making visible inequities and avoiding essentialist representations, this inquiry draws on recent research recommendations to focus on children’s experiences in disadvantaged contexts while avoiding social categories (Kaukko et al., Citation2022; O’Rourke et al., Citation2017). The theory of practice architectures offers a theoretical and methodological resource to frame this inquiry which aims to explore with children their experiences of play in Irish DEIS primary schoolyards.

Methodological approach

Ensuring methodological choices align with theoretical understandings and inquiry aims is of most importance for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research (Nayar & Stanley, Citation2023). The decision to employ walking interviews and reflexive thematic analysis is congruent with critical perspectives of knowledge as situated and that interpretations are those of the researcher – in this inquiry informed by the theory of practice architectures and play scholarship (Kemmis, Citation2019; Springgay & Truman, Citation2019; Spyrou et al., Citation2019). Drawing from ethnographic research and Kusenbach's (Citation2003) go-along interviews, walking interviews aim to provide a contextualised understanding of everyday practices, leveraging embodied experiences and spatial cues as participants walk with the researcher in a familiar context (Springgay & Truman, Citation2019). Ethical considerations also informed the choice of walking interviews, promoting children’s participation, and reducing vulnerability to power imbalances by providing children with more control over the pace and content of interviews (Camponovo et al., Citation2023; Horgan et al., Citation2022). Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Log number: 2021-0357) and the Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork (Log number:2021-111).

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was employed to recruit children from two DEIS schools, involving an invitation letter to 51 schools in an education department region with a major city, towns, and rural schools. The two co-educational Catholic schools represent a city and town context with over 300 and 800 pupils, respectively. Both schools had large green areas, hard surfaced yards, boundaried by walls, designated areas for each class group (approximately 22 children) and little fixed equipment. School principals acted as gatekeepers providing initial parent and child information and consent forms and supervising a researcher information session to classes identified based on children’s ages and children and teachers’ timetables. Twenty-three children, 6 girls and 17 boys (aged 9–12) from across 3 classes in the two schools completed consent forms, while not requested 13 children described themselves as from minoritized communities.

Data gathering

The data gathering protocol considered ethical, practical, and methodological aspects including children’s availability, weather, and research time constraints. Multiple visits over eight weeks supported ethical recommendations to spend time in context to gain familiarity (Spyrou et al., Citation2019) and involved walking interviews and informal observations during break times. Two walking interviews were planned to support richer insights enabling children to extend and review their narratives. Informed consent was recognised as an on-going process and children’s choice to participate, and inquiry information was reviewed before each interview.

Interviews took place in the yard between breaks with teachers supervising from within the school for privacy. All children completed an initial interview, leading the researcher around their schoolyard. The researcher recorded the interview on MS Teams software, using an external microphone. Guiding questions were informed by the theory of practice architectures (a) describe your play (sayings), (b) show me/tell me where you play/what you do/who you are with/your best memories (doings) (c) tell me your experiences of children’s play together/being left out of play in the schoolyard (relatings) and what constrains and enables your play (arrangements).

Children requested the opportunity to self-aggregate into peer groups for the second interview as this reflected their experiences within play in the schoolyard. As Horgan et al. (Citation2022) recommend research with children requires ethical responsiveness and the researchers adapted the protocol accordingly. Children self-organised into two groups of five boys in the town school, and three groups of four boys; two girls /two boys and four girls in the city school. A prior plan was agreed with children to speak close to the microphone one at a time. This group interview held loosely to guiding questions and drew on children’s interviews, however, was mostly responsive to what children decided to focus on, often triggered by spatial elements in the yard. Individual interviews were on average 20 minutes and group interviews 60 minutes. Interview recordings were uploaded to MS Stream software on a secure server before leaving the school.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) served as the analytical approach, involving a systematic six-stage process (Braun et al., Citation2022; Byrne, Citation2022). Informed by the theoretical approach and inquiry aim, the analysis used an initial inductive approach centring children’s constructions of play, This included listening to recordings, producing transcriptions, and coding interviews descriptively (identifying words/sayings children used to describe play practices) and interpretatively (identifying how descriptions related to conceptualizations of play, spaces, and inclusion/exclusion). Codes were then grouped, and the data were at this stage treated as a single data set and not differentiated by any categories. Using the lens of practice architectures theory, the analysis constructed initial themes with shared meaning focusing on children’s representations of play practices and enabling and constraining practice arrangements. Final analysis involved, returning to the interview data to consider resonance and points of difference with theoretical concepts and collaborative discussions on how themes constructed mattered certain elements and excluded others. Writing up themes clarified each theme’s central concept and children’s names were replaced with pseudonyms.

Results

Applying the theory of practice architectures to children’s interview data generated rich insights into children’s play as social practices situated within Irish schoolyards. The analysis generated three themes emphasising differing central ideas interpreted from children’s experiences and perspectives: (1) the state of play – cracks with(in) the routines of the schoolyard, (2) playing along and with(in) this shared space and (3) the hard yard.

The state of play – cracks with(in) the routines of the schoolyard

This theme focuses on children’s contrasting representations of play practices as both habitual and emergent. Analysing this apparent incongruence highlights how children’s experiences of habitual play practices resonate and contrast with discourses on childhood and play as a right and the centrality of fun in children’s experiences of play as emergent and transformative.

Children’s descriptions of how they play with(in) the routines of the schoolyard were diverse, ambiguous, and often contradictory, reflecting the subjective plurality of children’s experiences. While children’s reasons for valuing play were multiple – as an opportunity to get exercise and sunshine, to spend time with friends, or take a break from classwork, a positive affective dimension was central to all children’s representations of why they valued play.

It’s really, really, fun for me, and it’s fun for other people. (Orin, 10). It just makes you feel happier. (Paul, 10)

There’s nothing else to do except tag (Evan, 10) You’re free to do what you want, well, you’re not free to do what you want. (Carol, 12)

Most people would be hyped in the yard if there was no teachers. Yeah, they would be running around, like being crazy. (Paul, 10)

The best time I think was when it was winter and there was ice on the ground … (Ziggy, 10). When (SNA/Teacher assistant) turned her back, we all started ice skating. (David, 11)

Cohering the apparent incongruence between contrasting representations of play was a shared construction of play within the schoolyard as necessary. Children’s experiences of play as emergent, represented play as always possible. Children’s memories of play as fun, then meant that fun and happiness were also always possible. The significance of the positive affective dimensions of play was thus emphasised – holding possibilities to disrupt the mundanity of everyday schoolyard routines.

And if you didn’t have break, what would it be like? (Researcher). I’ld quit the school I’d leave. (Tim, 10)

Playing along and with(in) this shared space

Interpreting children’s play in schoolyards as relational is the central concept of this theme. The analysis highlights the interrelationships between children’s play choices and enabling and constraining arrangements and emphasises the significance of play to children’s identities, friendships, and relationships with(in) the schoolyard.

The limited resources and restricted space available to children were prominent in their descriptions of play practices. Walls and chalk lines created spatial boundaries which children played within, with, and against in schoolyards and embedded within games as goal posts and finishing lines. By their absence, all objects were made relevant. A shaded corner, sloped edge, or dangling pipe on the schoolyard (was) pulled (by) children into play together. Ideas were carried into the schoolyard from ‘real’ and digital spaces and enacted and reconfigured within play. Materiality was mostly human, and movement and touch while regulated was inevitable. Children intentionally and unintentionally connected, balls, and the ground producing a constantly changing, mostly noisy, sensory field. Play’s interdependencies with temporal dimensions was evident in how seasonal natural elements of fallen leaves and rain ‘created action’ (Orin, 10) and how sunny days extended boundaries onto grassy areas. The spatial separation of different age groups in the yard also intersected with the production of distinct social groups of us/we/our class and them/ the other class, determining who, where, and what children could and couldn’t play with.

Sometimes I do see my cousins over the wall and the teacher just tells them to go away. (Paul, 10)

Everybody that plays football like they all have a big friend group and everyone that doesn’t, they have a friend group as well … but I think we’re more popular. (David, 10)

The person that made the game up controls the whole game … Well then we nerf him … Say if your power is way too strong, yeah, then you can make the creators or the owners of the game specifically … make their power weaker. (Ben, 10)

I don’t like foursquare, but I don’t play basketball cos Sarah never wants to and I don’t know why. (June, 10)

The hard yard

This theme focuses on children’s experiences of significant constraints and a normalised acceptance of fighting and exclusionary practices in what we termed ‘the hard yard’. The analysis examines how children’s experiences of play practices were interrelated with the constant (re)production of the ‘hard yard’ as a restrictive, inequitable, and exclusionary social space.

Significant spatial-material constraints on children’s play opportunities were represented as an injustice, reinforced by children’s perspectives of better spaces and objects in other schools and classes and for many of having ‘more stuff to do at home’ (David 10). The schoolyard was described as boring, ‘just endless’ (Matthew, 10) with ‘nothing inside of it’ (David, 10). The limited availability of objects was confounded by their random removal and dilapidated state, for example, deflated balls and broken basketball hoops. While useful for ball games, children recounted multiple experiences of falling and hurting themselves on the hard, tarmacked ground where natural elements were absent or out of bounds.

No climbing trees … no grabbing the leaves on the trees. (Peter, 10)

Don’t push somebody else. Don’t throw at somebody else. Don’t grab somebody’s hair, it’s common sense, there isn’t like rules that usually they wouldn’t know. (Serena, 12)

They’re just putting our options down more. What good is that like? What good is that? … We’re not going to be able to learn. (Liam, 10)

I think, my teacher is racist, my substitute teacher (Paul, 10). I really think so because she’s always mean to, John (Sarah, 10). Oh yeah, she always is. John doesn’t even do anything. (June, 10)

Our class and the other class … they started making gangs and then we started fighting, throwing stones at people, dragging them down off the monkey bars. (Matthew, 10)

They'd like tell me to play hide and seek with them yeah, say yes and I turned around and I turned back, and they’ve all gone running away from me. (Carole, 12)

It’s usually if that person doesn’t, like no one goes around with that person, they’re a troublemaker and they always make trouble for other people (Patrick, 10). She has lice. nobody hangs out with her because of that. (Carole 12)

‘I’m mostly focused on myself … They don’t do it to me so I’m happy’. (Paul, 10)

Discussion

In making visible significant constraints, inequities, and exclusionary practices within children’s play in schoolyards, this inquiry’s resonance with previous research, echoing Titman’s (Citation1994) observations, further establishes the pervasive neglect for play within schoolyards. Interpretations of play rights policies as ‘blunt instruments’ (Lester & Russell, Citation2014, p. 16) in the absence of contextualised research, informed the aim of this inquiry. This discussion focuses on how the insights generated into children’s constructions of play as socially situated practices, informed by the theory of practice architectures, may contribute to progressing the conditions for play possibilities in the context of Irish schoolyards.

Play rights recommendations to provide adequate space, time, and permission to play within schoolyards (Russell, Citation2021) are unrealised in children’s experiences across the two Irish DEIS schools of hard-surfaced, restricted spaces, lacking care and play value. Given the reported absence of research to date, this inquiry strengthens the case for a comprehensive evaluation of existing play provisions in Irish schoolyards nationally. However, the significance of play to children’s identities, friendships, experiences of fun, connection, and exclusion, emphasises the need for an evaluation that considers more than spatial-material dimensions. Aligning with schoolyard play research recommendations, facilitating adults and children to analyse conditions for play in their context requires attending also to existing assumptions, norms, and social practices (Russell, Citation2021). The ‘exemplar’ (Lester et al., Citation2019) presented, shows the potential as Kemmis (Citation2019) suggests to use the theory of practice architectures as a praxis tool to support evaluation processes. As this inquiry emphasises, this approach supports not only the identification but greater understanding of how, socio-political, and cultural-discursive arrangements enable and constrain social practices in complex interrelated ways.

Children’s contrasting representations of play as habitual and emergent highlight the complexities of play as social practices (with)in schoolyards. Play, as mundane practices within everyday routines, was interrelated with the (re)production of what was termed ‘the hard yard’, where children negotiated their own identities and how to relate with others in this constrained space. Resonating with previous studies, the consequences of careless, neglect-full schoolyards were played out most significantly, in children’s acceptance of restrictions, fighting, social hierarchies, and individualistic and exclusionary practices as the ‘norm’ (Beresin, Citation2010; Rönnlund, Citation2017; Titman, Citation1994). In this Irish context, how the ‘hard yard’ was kept in place as Kemmis (Citation2019) describes by play practices interrelated with certain normative traditions, underscores the need for greater consideration of play in attempts to address the schoolyard, as a place of exclusion (Marron, Citation2008; Ní Dhuinn & Keane, Citation2021; Scholtz & Gilligan, Citation2017).

Of further relevance to school practices, this inquiry provides us with a different lens to consider ideas of play as always freely chosen, fun and suspended from everyday realities. The individualising of children’s choices was identified as an important dimension in children’s experiences of the (re) production of social hierarchies, dominant identities, and exclusionary social practices. The ‘hard yard’ produced dominant identities of ball players and getting along with others which represent as Rönnlund (Citation2017) argues, constructions of the ideal schoolyard child. Certain ways of playing and play choices were however privileged and enabled. Despite children’s acknowledgement of inequitable opportunities, the troublemaker child was represented as choosing to be on the margins of play, both socially and spatially. Children’s play choices were further complicated by interrelating with acceptance by peers, a desire to be popular, children’s feelings of safety and with the maintenance of friendships, which held significant social capital. These interpretations suggest the need to reconsider ideas of agency as relational (Lester et al., Citation2019) and as Spyrou et al. (Citation2019) assert the relevance of vulnerability in children’s lives.

Children’s experiences of hurt and harm and precarious friendships within play practices as they navigated individual and collective interests in schoolyards make visible what Ringrose and Renold (Citation2010) describe as ‘normative cruelties’. This has implications for practices that accept these cruelties as a social learning dimension of freely chosen play, with at best individual and societal benefits and at least, no long-term consequences (Sandseter et al., Citation2023). Neglecting the evidence that children with minoritised identities experience greater exclusion impacting significantly on their health and well-being (D’Urso et al., Citation2021) risks perpetuating societal inequities.

Addressing inclusion within play as a normalising social practice (Springgay & Truman, Citation2019) requires making visible constraints that reproduce inequitable, exclusionary, and individualistic play choices. However, despite experiences of ‘playing along’ within the ‘hard yard’, children’s perspectives reflected Kaukko et al.’s (Citation2022) suggestion that play practices are prefigured but not predetermined. Children’s contrasting representations of play reflected their experiences of play as not only reproducing but disrupting habitual practices. Play held the hopeful potential to always create conditions of possibility for fun, happiness and a sense of acceptance and connection with peers. The significance of positive affective dimensions to children’s identification of play as central to their social lives resonates with research on the importance of positive emotions to overall life evaluations (Helliwell et al., Citation2023; Kustatscher, Citation2017). In mattering most children’s experiences, this inquiry sheds light on how creating conditions for equitable play also creates conditions of possibilities to transform schoolyards from spaces of exclusion to shared spaces as Lester et al. (Citation2019) suggest for both individual and collective flourishing.

Methodological considerations

The trustworthiness of the research was supported by collaborative reflexive decision-making, a clear description of the theoretical approach and inquiry aim, an audit trail, the completion of two interviews and a systematic analytical approach (Nayar & Stanley, Citation2023). This inquiry held no intentions to generalise or categorise, and the researchers’ interpretations focused on resonance rather than validation (Springgay & Truman, Citation2019). It is necessary to highlight, however, that the small purposive group of participants had a greater number of girls and 13 children identified as having minoritised identities, given the research on play inequities as interrelated with intersectional identities. Children’s active engagement in the walking interviews reflected previous reports of this method as a child-friendly, ethical, participatory approach to generating contextualised knowledge (Horgan et al., Citation2022). The theory of practice architectures proved beneficial as both a theoretical and methodological approach in generating insights into the complexities of play as a social practice in a specific context.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the children for taking part in this inquiry and their families and teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michelle Bergin

Michelle Bergin is a Ph.D. candidate and early-stage researcher on the P4Play programme (www.p4play.eu) and a registered occupational therapist. Michelle’s research interests include how critical, decolonial, and post-qualitative theory intersects with practices and human flourishing.

Bryan Boyle

Bryan Boyle is a lecturer at the department of occupational science and occupational therapy at University College Cork, and a visiting lecturer at Luleå University of Technology, Sweden. Dr. Boyle’s research interests include the intersections of technologies and children.

Margareta Lilja

Emerita Margareta Lilja is an occupational therapy professor at Luleå University of Technology, Sweden. Professor Lilja’s research interests include occupational science and play.

Maria Prellwitz

Maria Prellwitz is a lecturer at the department of occupational therapy, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden. Professor Prellwitz’s research interests include children’s play and playground accessibility.

References

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

- Baines, E., & Blatchford, P. (2023). The decline in breaktimes and lunchtimes in primary and secondary schools in England: Results from three national surveys spanning 25 years. British Educational Research Journal, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3874

- Beresin, A. R. (2010). Recess battles: Playing, fighting, and storytelling. Mississippi University.

- Bergin, M., Boyle, B., Lilja, M., & Prellwitz, M. (2023). Irish schoolyards: Teacher’s experiences of their practices and children’s play – “it’s not as straight forward as we think”. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2023.2192201

- Blake, A., Sexton, J., Lynch, H., Moore, A., & Coughlan, M. (2018). An exploration of the outdoor play experiences of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder in an Irish preschool setting. Today’s Children Tomorrow’s Parents: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 47, 100–116.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2022). Doing reflexive TA. The University of Auckland. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://www.thematicanalysis.net/doing-reflexive-ta/

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke's approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Camponovo, S., Monnet, N., Moody, Z., & Darbellay, F. (2023). Research with children from a transdisciplinary perspective: Coproduction of knowledge by walking. Children’s Geographies, 21(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.2017405

- Clements, T., & Harding, E. L. (2022). Children’s views on playtime in schools: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Playwork Practice, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijpp.02.01.11

- Department of Education. (2017). DEIS Plan, 2017: Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/0fea7-deis-plan-2017/

- Department of Education. (2022). Cineáltas: Action plan on bullying Ireland‘s whole education approach to preventing and addressing bullying in schools. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/52aaf-cinealtas-action-plan-on-bullying/

- Department of Education. (2023). DEIS Schools 2023-2024. https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/4018ea-deis-delivering-equality-of-opportunity-in-schools/#deis-schools-2023-2024

- Department of Education and Skills. (2017). Deis plan, 2017: Delivering equality of opportunity in schools.

- Devine, D., Symonds, J., Sloan, S., Cahoon, A., Crean, M., Farrell, E., Davies, A., Blue, T., & Hogan, J. (2020). Children’s school lives: An introduction, Report No.1, University College Dublin. Retrieved 9 June, 2023, from https://cslstudy.ie/news/

- D’Urso, G., Symonds, J., & Pace, U. (2021). Positive youth development and being bullied in early adolescence: A sociocultural analysis of national cohort data. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 41(4), 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431620931199

- Fahy, S., Delicâte, N., & Lynch, H. (2020). Now, being, occupational: Outdoor play and children with autism. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(1), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1816207

- Fennell, J. (2021). Break-time inclusion: A case study of the effects of adult organised play on children with special educational needs. REACH: Journal of Inclusive Education in Ireland, 21(2), 77–87. https://www.reachjournal.ie/index.php/reach/article/view/117

- Fleming, B., & Harford, J. (2021). The DEIS programme as a policy aimed at combating educational disadvantage: Fit for purpose? Irish Educational Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1964568

- Gerlach, A., & Browne, A. J. (2021). Interrogating play as a strategy to foster child health equity and counteract racism and racialization. Journal of Occupational Science, 28(3), 414–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1826642

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., Norton, M., Goff, L., & Wang, S. (2023). World happiness, trust and social connections in times of crisis. In J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard, J. D. Sachs, L. B. Aknin, J. E. De Neve, & S. Wang (Eds.), World happiness report 2023. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/world-happiness-trust-and-social-connections-in-times-of-crisis/

- Horgan, D., Fernández, E., & Kitching, K. (2022). Walking and talking with girls in their urban environments: A methodological meandering. Irish Journal of Sociology, https://doi.org/10.1177/07916035221088408

- Kaukko, M., Wilkinson, J., & Haswell, N. (2022). ‘This is our treehouse’: Investigating play through a practice architectures lens. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 29(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682221091419

- Kemmis, S. (2019). A practice sensibility. An invitation to the theory of practice architectures. Springer.

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/146613810343007

- Kustatscher, M. (2017). The emotional geographies of belonging: Children’s intersectional identities in primary school. Children’s Geographies, 15(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1252829

- Lester, S., Lester, J., & Russell, W. (Eds.). (2019). Everyday playfulness: A new approach to children‘s play and adult responses to it. Jessica Kingsley.

- Lester, S., & Russell, W. (2014). Turning the world upside down: Playing as the deliberate creation of uncertainty. Children, 1(2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.3390/children1020241

- Lodewyk, K. R., McNamara, L., & Sullivan, P. (2020). Associations between elementary students’ victimization, peer belonging, affect, physical activity, and enjoyment by gender during recess. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 35(2), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573519856814

- Mahon, K., Kemmis, S., Francisco, S., & Lloyd, A. (2017). Introduction: Practice theory and the theory of practice architectures. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Exploring education and professional practice (pp. 1–30). Springer.

- Marron, S. (2008). An analysis of break time active play in Irish primary schools [Unpublished master's thesis]. Waterford Institute of Technology. http://repository.wit.ie/id/eprint/1027

- Massey, W., Neilson, L., & Salas, J. (2020). A critical examination of school-based recess: What do the children think? Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health, 12(5), 749–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1683062

- McKendrick, J. H. (2019). Scotland’s school grounds: Playful and play-full learning environments? Scottish Educational Review, 51(2), 28–42.

- National Children’s Office. (2004). Ready, steady, play! A national play policy. The Stationary Office. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from https://assets.gov.ie/24440/03bb09b94dec4bf4b6b43d617ff8cb58.pdf

- National Council for Special Education. (2011). Inclusive education framework. https://ncse.ie/wpcontent/uploads/2014/10/InclusiveEducationFramework_InteractiveVersion.pdf

- Nayar, S., & Stanley, M. (Eds.). (2023). Qualitative research methodologies for occupational science and occupational therapy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Ní Dhuinn, M., & Keane, E. (2021). ’But you don’t look Irish’: Identity constructions of minority ethnic students as ‘non-Irish’ and deficient learners at school in Ireland. International Studies in Sociology of Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2021.1927144

- O’Rourke, C., O’Farrelly, C., Booth, A., & Doyle, O. (2017). ’Little bit afraid ‘til I found how it was’: Children’s subjective early school experiences in a disadvantaged community in Ireland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(2), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1288386

- Ringrose, J., & Renold, E. (2010). Normative cruelties and gender deviants: The performative effects of bully discourses for girls and boys in school. British Educational Research Journal, 36(4), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903018117

- Rönnlund, M. (2017). The ideal schoolyard child: Subjectivity in teachers representations of educational outdoor space. In T. Vaahtera, A.-M. Niemi, S. Lappalainen, & D. Beach (Eds.), Troubling educational cultures in the nordic countries (pp. 34–51). Tufnell Press.

- Russell, W. (2021). The case for play in schools: A review of the literature. Retrieved 6 December, 2022, from https://outdoorplayandlearning.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-Case-For-Play-In-Schools-web-1-1.pdf

- Russell, W., Tawil, B., & Barclay, M. (2023). (At)tending to rhizomes: How researching neighbourhood play with children can affect and be affected by policy and practice in transcalar ways in the context of the Welsh government’s play sufficiency duty. Civitas – Revista de Ciências Sociais, 23, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2023.1.42098

- Sandseter, E. B. H., Kleppe, R., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2023). Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: An evolutionary approach. International Journal of Play, 12(1), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2022.2152531

- Scholtz, J., & Gilligan, R. (2017). Encountering difference: Young girls’ perspectives on separateness and friendship in culturally diverse schools in Dublin. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 24(2), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568216648365

- Springgay, S., & Truman, S. E. (2019). Walking methodologies in a more-than-human world. Walking Lab. Routledge.

- Spyrou, S., Rosen, R., & Cook, D. T. (2019). Reimagining childhood studies. Bloomsbury.

- Titman, W. (1994). Special places; special people: The hidden curriculum of school grounds. Worldwide Fund for Nature.

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2013). General comment No. 17 (2013) on the right of the child to rest, leisure, play, recreational activities, cultural life, and the arts (art. 31). https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9bcc4.html

- Walsh, G., & Fallon, J. (2021). What’s all the fuss about play’? Expanding student teachers’ beliefs and understandings of play as pedagogy in practice. Early Years, 41(4), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2019.1581731

- Woodyer, T., Martin, D., & Carter, S. (2016). Ludic geographies. In B. Evans, J. Horton, & T. Skelton (Eds.), Play and recreation, health, and wellbeing (pp. 17–33). Springer.