Abstract

At a time when the welfare needs of individuals within powerful organisations, such as professional sport, are being scrutinised it is appropriate to look at what is being done to support athletes and what more may be needed. The RFL, in recognition of the need for welfare support, introduced player welfare managers to all Super League clubs in 2011. Using an interpretivist approach, we report the findings from a series of semi-structured interviews with player welfare managers (PWMs) that explored the PWMs’ perceptions of player welfare, what impact they believe they are having on player welfare, and what else is needed to enhance the service. The PWMs perceive that they have been an important resource for players, independent of the club and coaches, which has allowed players to seek support for a range of issues. The use of the services provided by PWMs increased over the time between interviews, this, it is thought, is due in part to a change of culture within the sport. The PWMs felt the head coach, along with the backing of the club, and the RFL structure were important in the services being accessible and accepted. The PWMs were struggling to meet the demands of their job roles, which were largely part time. However, since the results of this and other studies were made accessible to the RFL, large-scale changes to welfare provision have been made, including making the PWMs’ posts full-time. This is seen as an important contribution and commitment to players’ welfare needs.

Introduction

The world of elite level sport is viewed as a privileged place in society where, typically young males, are offered fame and fortune whilst doing a job they enjoy. These physically tough men, we presume, do not need any help beyond performance development. The support structures around them provide coaching, nutrition, fitness and sport psychology support (to cope with the on-field pressures of high-level competition). The reality may be very different. Professional sport can lead to socialisation, from a young age, into a ‘sub-culture’ of society that is ‘like a magnet drawing people (often males) with few formal qualifications from underprivileged and underserved populations’ (Kornbeck Citation2017, 317). The profession is precarious and the athletes vulnerable to those in power who decide if the aspiring young athlete can make a career in sport, and for how long.

Whilst concerns over young athletes’ holistic development have been researched for a number of years, research into the welfare of adults throughout their athletic careers has received little attention. The Bosman ruling in 1995 was the first time professional players were recognised as workers (Kornbeck Citation2017) and the European Union (EU) became involved in player welfare again in 2009 through the ‘Treaty of Lisbon’, when concern over access to education and training for athletes led to guidelines on ‘dual careers’ in high-performance sport. The ‘dual career’ guideline suggests that the protection of athletes is based on two principles: (1) athletes have a right to access education and training (just as in other careers); and (2) the ability to perform is enhanced by access to education (Henry Citation2013). A report by Professional Footballers Australia (2015) found that one in five retiring athletes experience significant difficulties in transitioning out of elite sport (Agnew et al. Citation2017) and concluded that supporting transitions were not being adequately addressed by the sport. This was followed in April 2017 by the UK Government who put forward the case for increased athlete care and suggested the safety, well-being and welfare of athletes, of all ages, should be at the centre of what sport does ‘Winning medals is, of course, really important, but should not be at the expense of the Duty of Care towards athletes, coaches and others involved in the system’ (Grey-Thompson Citation2017, 4).

The Duty of Care report (Grey-Thompson Citation2017) suggests there is somehow a ‘price to be paid’ for success in sport but sport cannot think of itself as special or different and able to behave outside what is recognised as acceptable behaviour in the rest of society. Several recommendations were made including athletes being encouraged to focus on a ‘dual career’, rather than solely the one sport they excel at, support for transitions (into and out of elite level sport), education and the mental welfare of athletes. Athletes who have not developed an identity beyond sport and who fail to engage with dual careers appear to be at greater risk of experiencing difficulties both during and after their sporting career (Park, Lavellee, and Tod Citation2012). Individual sport governing bodies are now beginning to recognise both the need and value of supporting all of a player’s needs. In some sports, for example the Australian Football League (AFL), welfare support for players has been compulsory for over 15 years (Kelly and Hickey Citation2008), whilst in other sports it has been a more recent addition. More recently, the study of an athlete’s needs has taken a holistic ecological approach and suggests that the interactions between the athlete and their environment are critical to the development of athletes (in both their athletic and non-athletic domains) (Henriksen, Stambulova, and Roessler Citation2011).

In rugby league the need for revised welfare support was recognised in 2010 when the Rugby Football League (RFL), the UK-governing body for rugby league, introduced new guidelines (RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2015) to address rugby players’ welfare, alongside their coaching and performance development. Since 2011, it has been compulsory for all full time clubs to employ a Player Welfare Manager (PWM) whose job it is to support the welfare of the players. This role has been supported with guidance and a player welfare strategy, headed up by a Welfare Director (WD). The Player Welfare Policy aims to educate and support players from the moment they enter the professional game, throughout their playing career and in at least the first two years after they transition out of a playing role within the game.

The aim of the Policy is to ensure that Rugby League players:

| (a) | Can play to the best of their abilities unhampered by off field concerns; | ||||

| (b) | Are proud advocates of rugby league and act as good role models and spokesmen for the sport; | ||||

| (c) | Understand the responsibilities of life in the public spotlight as professional sportsmen; | ||||

| (d) | Have good life skills, show respect to all and make wise and ethical decisions; | ||||

| (e) | Develop mental resilience and understand mental health and addiction; | ||||

| (f) | Take responsibility for and invest in their personal development; | ||||

| g) | Plan and prepare for their career after their playing career to enable a smooth and immediate transition; | ||||

| (h) | Engage with the educational and networking opportunities available to them during their career; | ||||

| (i) | Are better men for their involvement in rugby league; | ||||

| (j) | Are prepared to manage change; | ||||

| (k) | Are able to support themselves financially and emotionally when they transition out of the sport. | ||||

(RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2015)

There has been relatively little research into the role of player welfare managers; the study on AFL (Kelly and Hickey Citation2008) is one of the few. Kelly and Hickey (Citation2008) argue that although welfare support is described as being in the player’s ‘best interest’ the collecting and distribution of personal information about players, may be detrimental to their careers. Most other research on welfare is concerned with supporting young athletes and their welfare needs, and none to our knowledge has researched rugby league players. Whilst there are numerous studies on the welfare needs, in particular career transitions, mental health and help-seeking problems in a masculine society (as discussed below), there is a dearth of research on how welfare needs can be supported and how best to manage the athlete to meet all their personal and professional needs.

Career transitions, whether through retirement at the end of a career or a sudden loss in career (non-normative transition) through injury or de-selection, have been the focus of numerous studies (e.g. Park, Lavellee, and Tod Citation2012). Studies suggest there are higher than average levels of common mental disorders (CMD) amongst retired footballers (Gouttebarge, Aoki, and Kerkhoffs Citation2015a) and retired rugby union players (Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, and Lambert Citation2015b). In the rugby union study, 48% of retired players were found to be living with two or more CMD symptoms (Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, and Lambert Citation2015b). The transition to a new career, post-sport, can be aided by education and Jennings (Citation2015) found that educationally prepared players were better equipped for life after rugby and were able to cope with the emotional effects of retirement. Brownrigg et al. (Citation2012) explored the psychological impact of retirement on professional footballers; the retired athletes they interviewed felt that players could be encouraged to seek help with pre-planning and preparation for work post football.

The stigma surrounding mental health can make it difficult for players to engage with support (Gouttebarge, Kerkhoffs, and Lambert Citation2015b). Seeking help may be seen as a sign of mental weakness (Gulliver et al. Citation2015) and fears over losing a place in a team or a whole contract may mean athletes are reluctant to open up about their difficulties (Bauman Citation2016). There is some evidence to suggest that athletes are less likely than non-athletes to seek help for mental health problems (Watson Citation2005), specifically male athletes (Watson Citation2005). The age group 16–34 are also least likely to seek help for mental health difficulties and this is also the typical age of elite athletes (Wood, Harrison, and Kuchorska Citation2017). In their study of help-seeking behaviour amongst male professional footballers, Wood, Harrison, and Kuchorska (Citation2017) call for further research into sport and mental health, and outline the difficulties athletes may have in seeking help. They suggest that stigma surrounding mental health, alongside poor mental health literacy may be preventing help-seeking behaviour. According to Woods et al., there is limited support available within professional clubs and young footballers, and those forced to retire early, in particular, are critical of the support offered (Wood, Harrison, and Kuchorska Citation2017). Wolanin, Gross, and Hong (Citation2015) concede that there are sub-populations of elite athletes at increased risk of depression and there needs to be people in place who can diagnose and treat those with mental health problems but also those athletes are less likely to seek help due to time constraints and stigma.

Rugby is a physical sport that regularly adopts characteristics of aggression, violence and toughness (Williamson Citation1995; Light Citation2007). As a heavy contact sport, rugby has traditionally been seen to embody stereotypical masculine identities. Men who embody masculine norms are less likely to seek help for psychological issues (Steinfeldt and Steinfeldt Citation2012) and have been shown to have higher rates of depression, anxiety and substance abuse (Cournoyer and Mahalik Citation1995; Blazina and Watkins Citation1996) and ineffective coping strategies (Evans et al. Citation2011). Whilst there has been a trend towards more social inclusion and support in rugby, the physical nature continues to grow (Bathgate et al. Citation2002; Murray, Murray, and Robson Citation2014) as players strive to be physically intimidating and tough (Light Citation2007). Mental toughness is difficult to conceptualise but resonates with a macho, masculine, patriarchal culture (Kerr and Stirling Citation2017). This is supported by Anderson (Citation2011) who suggests there is a potential negative impact of focusing on mental toughness on both physical and psychological health. Kerr and Stirling (Citation2017) go further in suggesting that ‘not only is the construct (mental toughness) nebulous, but it reinforces the performance narrative, the masculine culture and win-at-all costs approach that is often associated with negative and harmful consequences for athletes’ and suggest both scholars and sports practitioners abandon the term. In its place they suggest that managing stress and adversity should be developed and framed within an athlete welfare approach.

The RFL in introducing a new welfare policy sought to meet some of the more holistic needs of their players. The WD who manages the policy and the PWMs who deliver on the welfare policy, were keen to know how the new guidelines transferred into meeting the welfare demands of the players. A report, including the views of rugby players across the Super League is available (Lewis et al. Citation2016), however this paper explores in-depth the PWMs’ perceptions of player welfare, how they engage with the role and what impact they believe they are having on player welfare, and what else is needed to enhance the service. The findings from this study will provide an insight into the PWMs’ role that can be utilised by the RFL and there is an opportunity for other sport-governing bodies and clubs, who recognise the findings from the PWMs to transfer the findings to their own sports.

Methods

Methodology

The study was part of a wider study to explore welfare support provided by the RFL. The study used a mixed methods approach, what is presented here is the qualitative phase of the research. The research adopted a ‘subtle realist’ approach which differs from a ‘realist’ approach as although we accept a realist ontology we also adopt a relativist epistemology. Hammersley (Citation1992) suggests that in adopting a ‘subtle realist’ position the researcher concedes that it is impossible to have certainty about any knowledge claims and that they cannot escape the social world to study it. Akin to researchers from a ‘social constructionist approach, “subtle realist” researchers do not accept at face value the words spoken by the participants. They acknowledge there may be factors or forces beyond the individual’s knowledge which drive behaviour (Murphy et al. Citation1998). However, the researcher can try and uncover these to describe and explain a causal relationship between a person’s experiences and perceptions and how they act. ‘Subtle realists’ describe the aim of research as being to represent reality, rather than reproduce it (Hammersley Citation1992). This approach Hammersley (Citation1992) argues, allows us to accommodate some elements of a social constructionist approach, without abandoning a commitment to independent truth (Murphy et al. Citation1998, 69). The objective, from a subtle realist perspective, is to search for knowledge about which we can be reasonably confident, based on the credibility and plausibility of knowledge claims (Murphy et al. Citation1998). Whilst this mixing of subjective and realist approaches is not without its critics (Smith and McGannon Citation2017), it is recognised by others as a legitimate approach to studying people and their social realities (Maxwell Citation2011; Shannon-Baker Citation2016; Howes Citation2017). The ‘mixing’ of approaches is a widely accepted philosophical approach, in particular in mixed methods (Teddie and Tashakkori Citation2011; Onwuegbuzie, Collins, and Frels Citation2013). As argued by Maxwell (Citation2011) philosophical stances and assumptions are lenses through which to view the world. The views they provide are fallible and incomplete and we need multiple lenses to acquire in-depth knowledge of the phenomena we study (Maxwell Citation2011, 28)

The subtle realist position fits with the research questions of understanding how PWMs perceive player welfare, what impacts they believe they will have and what more is needed. This approach involved interviewing the PWMs to gain their understanding of the role and its impacts but it also acknowledges that the researchers’ own backgrounds will influence both the line of questioning and the interpretation of the dialogue. Supporting the welfare of athletes is not necessarily easily defined and measured and should be viewed as ‘social reality’ (King and Horrocks Citation2012). Our understanding and experiences are relative to our specific cultural and social frames of reference (King and Horrocks Citation2012, 9) and can be interpreted in a number of ways. Many (but not all) of the PWMs are ex-players and all have been in and around the sport of rugby league for a number of years. Their interpretations of welfare provision and support will be grounded within those terms of reference. The all-female academic research team may be seen as naïve to the rugby league culture and make it difficult to interpret and understand the demands on professional male athletes. The lead author, however, has both experiences as a team sport member for many years and experience of the rugby league culture as a parent. These experiences meant that she came to the interviews with some preconceptions of the rugby league culture and in particular the pressure on players to demonstrate male stereotypical behaviours. However, the interpretations were discussed with another researcher who had fewer preconceptions of the rugby league world and who was able to act as a critical friend. A critical friend is one way of increasing the rigour of the research by encouraging reflexivity and challenging the construction of knowledge (Smith and McGannon Citation2017).

This research attempts to explore the realities of those engaged in one-to-one, continuous, structured but flexible welfare support to a group of professional athletes. For this Morgan and Ziglio’s (Citation2007) asset based approach to health promotion was used as a guide to designing the interview questions. An ‘asset based approach’, balances the evidence base on health deficits (identifying problems and needs) with an equal focus on health assets (resources for creating health and well-being). An asset approach seeks to identify and mobilise the capacity, skills, knowledge, connections and potential in individuals, communities and organisations to create positive health and cultivate resilience. This meant the questions allowed the PWMs to focus on the benefits and the challenges they faced and to identify areas of strength as well as weakness in the provision. Whilst these findings cannot be generalised to all professional sports, it may allow for naturalistic generalisations from others supporting elite level athletes who may recognise and relate to the findings from these PWMs’ experiences. This happens when the research resonates with the reader’s personal experiences (Smith Citation2018). We feel there is value to exploring these experiences as there is currently little understanding of help and support networks for elite-level athletes (Coyle, Gorczynski, and Gibson Citation2016).

The organisation of the RFL

The Super League is divided into 12 clubs, the majority of which are situated in the North of England with one club based in France (Catalan Dragons). In 2011, the RFL made it compulsory for all clubs to have a Player Welfare Manager (PWM) employed at least 3 days per week. They also provided a player welfare strategy (RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2015a) which outlined the roles and responsibilities of the PWM. Throughout the 12 clubs there are over 400 contracted rugby players. The RFL also commissions ‘Sporting Chance’ to provide counselling and mental health support to players as well as independent qualified Careers Coaches. The PWMs’ role is not to provide individual clinical support, but to act as a sign posting system to engage players with external agencies (such as Sporting Chance, Careers Coaches) who can provide the professional level of support needed. They act as an independent link between the players and services seen as important to player welfare.

Participants

The participants were purposively selected based on total population sampling (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014). All PWMs employed by a Super League club were invited to be interviewed. In the first year, 11 out of a possible 14 PWMs employed by Super League clubs were interviewed and in the second year 12 out of the 14. The PWMs who were not interviewed either did not respond to the e-mails or were unable to find a convenient time for the interview. It was important that the PWMs were able to refuse to take part and once two attempts were made to arrange the interviews, the PWMs’ right to not be involved was respected. To maintain anonymity no identifying features were included in the data collection. There are only a small number of PWMs all of whom know each other, providing any detail on individual participants would make them easily identifiable to their colleagues. The majority, but not all, were male. The participants ranged from being in the job a few months to five years. The participants were generally employed three days a week, although some were full time. They all had some compulsory training prior to starting the role and regular contact with the WD.

Procedure

Once ethical approval had been gained by the host institution ethical committee, participants were contacted by the WD, who acted as the gatekeeper, and given one of the researcher’s contact e-mail address to arrange an interview. Through e-mail exchange a mutually convenient time for an interview was organised and participants were e-mailed a copy of the ‘Participant Information’ and ‘Consent’ form. The researcher explained the aims of the study prior to the interview and agreed verbal consent before the first questions were asked. After two weeks the WD sent an e-mail reminder to encourage those who had not participated to arrange an interview. The interviewer attempted to put the PWMs at ease before each interview commenced through asking about when they first became involved with rugby league. Many of them noted they were nervous, they were reassured that there were no right or wrong answers and that all data would remain anonymous.

The interviews were repeated a year later, with some modifications to allow for those interviewed twice to discuss how they felt the job and welfare support in general had changed during the previous 12 months. Although many PWMs were interviewed twice, where there was a change in personnel a PWM may have been interviewed only once. The RFL were interested in knowing if the introduction of more formal guidance was perceived as beneficial to the role, the repeat interviews allowed for this to be explored.

Data collection

All data were collected through semi-structured interviews, lasting 18–90 min. Semi-structured interviews were chosen rather than structured as they allow participants more opportunity to be flexible and reveal their feelings towards their experiences so providing deeper knowledge (Sparkes and Smith Citation2014). The majority of these were telephone interviews but two interviews (one the first year and one the second year) were face to face. The participants were offered either type of interview, but due to ease of facilitation and time concerns, the majority chose to undertake the interviews over the telephone. Interview questions included asking them what their role involved, any success stories, what barriers they faced, how they felt players responded to them and how the role could be enhanced. The interview guide, once written, was discussed with the WD and amendments made as necessary. The guide, however, was flexible and allowed the participants to express views they felt pertinent without a rigid structure to the conversation.

Data analysis

Template Analysis (TA, King Citation2012; Brooks et al. Citation2015) is a method developed for the thematic analysis of qualitative research data that has been widely used within a variety of applied settings, e.g. health care practitioners (King et al. Citation2013), chronic low back pain patients (McCluskey et al. Citation2011) and teachers in an educational setting (Ray Citation2009). TA uses an iterative approach – in this study, this allowed for the identification of new themes over the course of the work, ensuring that the study could be adaptive in relation to emerging issues. Template analysis allows for the inclusion of a priori themes identified through engaging with the literature. Following the review of the literature we identified that welfare support, and help-seeking in particular, may be impeded by the masculine culture of rugby, the level of support from the club and stigma in general for men to ask for support (outside of on-field performance). The a priori themes identified provided the initial template from which to analyse the data. A priori codes do not have a special status and are equally as subject to redefinition, revision or deletion as any other themes in the analysis process.

Data analysis began with ‘immersion’ in the data through reading the first transcript. Line by line coding was then undertaken and any parts relating to the research question were coded. If they related to an a priori theme, they were attached to this code, if there was no existing code then a new theme was identified and given a new code. This was repeated on the second interview and led to the development of a second template (a priori and new themes). This revised template was then applied to the full data-set but any new themes emerging were added as the process continued leading to a ‘final template’. This final template was used as the initial template for the second set of interviews. The process was repeated and again any emergent themes were added as we progressed through coding all the second set of interviews. The second ‘final’ template was used for the interpretation and write up of the findings.

The findings were organised according to the asset based approach used in designing the interview guide. The first section identifies the ‘problems and needs’ the second identifies the ‘assets’ (resources available) and the final section the ‘deficits’ (what else is needed). The quotes provided by the PWMs are used to illustrate the findings in all three of these sections and are labelled by number only (1–11 for the first set of interviews, 12–24 for the second set). In some instances, this may be the same person but no attempt was made to match findings between interviews from year 1 to year 2. There were 383 pages of transcript (with 1.5 line spacing).

Trustworthiness

To increase the trustworthiness of the study various steps were taken:

(1) The researchers spent time with the WD understanding the structure of the RFL and the context of the role of the PWMs. The WD was also included in discussions surrounding the themes generated and the write up of the study. Although we did not go back to those involved in the study, by working with the WD we were able to explore and discuss the findings and interpretations from someone with a long-standing and in-depth understanding of the PWM. These ‘member reflections’ (Smith and McGannon Citation2017) allow us increased confidence in our interpretations of the findings.

(2) The interviews themselves began with simple descriptive questions to establish a rapport with the PWMs and put them at ease before asking more in depth and explorative questions on the role. Whilst there are many ways of doing thematic analysis, Template Analysis was chosen as it is a hierarchical coding system, but unlike other coding systems does not suggest a set sequence of coding levels. Instead it ‘encourages the analysis to develop themes more extensively where the richest data (in relation to the research question) are found’ (Brooks et al. Citation2015). Whilst Template Analysis is not bound to one epistemology, when adopting a relativist epistemology the use of a priori themes are tentative and the focus is on the emergence of themes from the data.

(3) The use of appropriate quotations increased confirmability by demonstrating that the interpretations are based on the data so demonstrating how conclusions and interpretation have been reached (Nowell et al. Citation2017). This level of detail provides evidence for the reader to reflect on the interpretations of the researchers (Smith Citation2018) so allowing for naturalistic generalisation. The templates were produced and discussed independently by two researchers who reflected on the final template which was used as the basis for the final discussion. It could be argued that the interpretivist position taken means that the researchers can only agree on the interpretations based on their own perspective as outsiders to the social situation. However, this additional step can also be seen as an opportunity for the initial researcher to reflect on and justify the decisions made and confirm the perceptions of the PWMs have come from the data they provided and not pre-conceived ideas around welfare support. This use of a ‘critical friend’ is again considered as a criterion for developing rigour in the findings (Smith and McGannon Citation2017).

Results

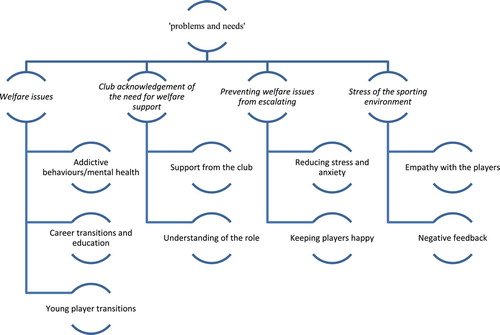

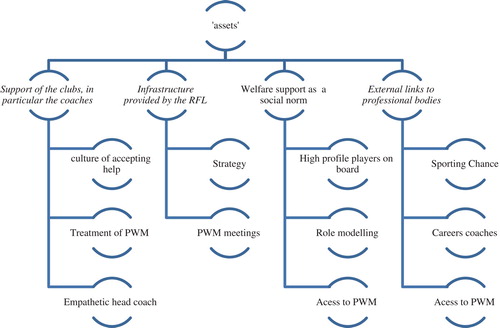

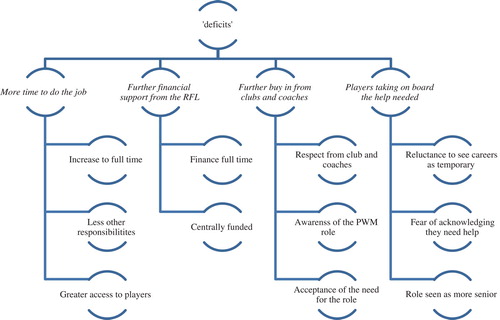

The themes developed from each data-set (one year apart) were similar, so are being reported as combined, with any changes described over the year included in the discussion. The results have been categorised into three core categories; PWMs’ perceptions of welfare issues experienced by Super League RFL players (‘problems and needs’), the factors that enhance welfare support (‘assets’), and areas of further need in supporting players’ welfare (‘deficits’). The three core categories and the subthemes related to them are illustrated in the thematic maps below (these are graphical representations of the final template), with examples of supporting quotes from the PWMs.

PWMs’ perceptions of welfare issues experienced by Super League RFL players (‘problems and needs’)

The PWMs described the role they undertook, and in doing so, described the range of problems they dealt with and illuminated the ways in which they felt their role was of benefit to the RFL ().

Welfare Issues

The PWMs identified a range of welfare issues that they were involved with these included addictive behaviours of some of the players (alcohol, drugs, gambling) ‘you’re always going to get a certain number that are going to be gamblers’ (PWM 2). They also acknowledged that these issues were being addressed by the RFL:

like the drugs I suppose really, you know like your social and non-prescription drugs, which has been, the new policy has come out, so we’re being very careful with that (PWM 11)

PWM 8 Yeah, we’ve dealt with all of those at various points, yeah, we’ve had, erm, you know, self-harming, erm, marriage breakdown, depression, anxiety, all of those things.

The PWMs facilitated a number of compulsory workshops to support players’ welfare with issues such as doping in sport, in particular, seen as important. More recently, issues such as social media use and how players are perceived in the media were regarded as important. The PWMs also kept a track of players’ education involvement and encouraged them to consider their future careers. They referred players on to a ‘careers coach’ for more specialised support. To identify player welfare needs one PWM asked players to fill in a welfare report:

So I’ll ask the players to fill in a welfare report and it’ll have education, relationships, career, erm, err, playing, it’ll have different areas and I’ll ask them to rate where they are in those areas. (PWM 8)

…but there’s a couple of the young lads who have been signed for the first team, who in my opinion as the welfare officer, are being severely mistreated and I don’t agree with that…

To me it’s about the health and well-being of the players and are they in a good position or are they sneaking off taking prescription drugs because they’re fed up and you know. That’s what we should be worried about’. (PWM 7)

Club acknowledgement of the need for welfare support

The PWMs described instances where they knew of problems a player was experiencing at home and that this may be linked to a recent drop in performance. They acknowledged that others at the club may not be aware of these problems so only they were in a position to realise the links. ‘Within the space of three months of my role there were issues arising that the club were not aware of so they quickly understood the need for my role’ (PWM 4). To begin with some clubs felt the PWMs were unnecessary as previously issues were not brought to light by the players, leading clubs to think there were no issues:

To start with a lot of people thought it was a bit of a cushy role and there was nothing really to do. But as I’ve mentioned, we have had some high profile cases at the club and they’ve seen the work that’s gone on, so there’s no question from the players that they see the role as important. (PWM 18)

Most of the people in management at a rugby league club, yeah they might have their own businesses, but they’ll all be from businesses somewhere. So do they really understand what player welfare is all about and the HR side of it? Does a coach? Because he’s come through and settled. Take some of the CEOs, they’ve not had to struggle with their career. So, can they relate to somebody struggling with their career? (PWM 5).

Preventing welfare issues from escalating

The PWMs also felt their intervention in welfare support was helping to prevent future mental health problems from escalating. Preventing mental health problems involved reducing stress and anxiety caused by issues either from outside or from within the sport:

First and foremost, its mental health well-being. They dovetail, because if a player is engaged in something outside his rugby career and he know he’s got a career outside that he’s working towards…it relieves that anxiety (PWM 5)

I think it’s a lot better because there never used to be one, erm, and it was very reactive to issues that arose. So it’s definitely a major improvement, erm, its whether it gets the continued investment and its continued to be taken seriously, erm, as its going, rather than reacting to events that occur and then throwing resources at it. I think if we can pre-empt things that may happen that we can try and avoid, then it’s got every chance of being a very successful meaningful role. (PWM 8)

It’s like a lot of thoroughbred horses, you know, they have to be in prime condition and if they’re not in prime condition, then they won’t perform and I think part of the getting in a prime condition is that they’re happy, all that they want to do, and this is all the players want to do, is they just want to play. (PWM 1)

Some, but not all clubs also have a club chaplain who is seen as important in providing pastoral support to players. Depending on the PWM the chaplain may be seen as the person to go to with personal problems instead of the PWM.

Stress of the sporting environment

Many PWM are ex-players and this allows them to recognise the stress of the environment ‘I think it helps in terms of my understanding of the lads and where they’re coming from, the pressures on them’ (PWM 6)

‘I think it helps that I was a player, you can empathise in a way as well as sympathise. I think that has helped me and I didn’t play at the top level… so I think that has helped me with the transition players who don’t make it or who have job insecurity’ (PWM 7). The PWMs have an understanding of what elite level sport can mean to an individual and how clubs are run ‘They (players) have to receive feedback, brutal feedback on a week to week basis from the peers, from the coaches, from media, from spectators, you know…’ (PWM 4). They also described how players were not used to having to do things for themselves ‘Used to people telling them what to do’ (PWM 1) so asking for help is not their normality.

Factors that enhance welfare support (‘assets’)

The PWMs were able to reflect on aspects of the set up and running of welfare support within the Super League RFL and identified a number of successful aspects. These included having an infrastructure provided by the RFL, support of the clubs, in particular the coaches, welfare support as a social norm and external links to professional bodies ().

Support of the clubs, in particular the coaches

The PWMs recognised that as well as the support of the RFL, they also need the club to support the role, but that the most influential official is the head coach:

If you don’t have buy in from the coach, or if the coach doesn’t support you on that, then you really are going to be struggling because the players will try and get away with anything, they really will, they’re only young men when all is said and done (PWM 16)

I can see, certainly the difference between the head coach we’ve got now and the one we had previously, who just made things, didn’t make things hard work, but didn’t help (PWM 13)

The first team coach doesn’t speak to me.

Doesn’t speak to you? Why?

Not really.

Because they don’t see the importance of welfare?

I don’t know really, I don’t know why he doesn’t speak to me, but he doesn’t. He doesn’t communicate with me on a regular basis. We don’t sit down and talk about players. Erm, you know, and I find that quite frustrating because I’ve been around the club a long time and I know how it works and lots of the people in it, you know.

Infrastructure provided by the RFL

The RFL by making the role of PWMs’ compulsory and providing a strategy have helped the development of the role ‘The policy makes it clear, welfare needs to be dealt with through the RFL, there needs to be a PWM in post, with no excuses from any club’ (PWM 3). They also provide central resources to fund external support such as Sporting Chance, which can be accessed by all clubs. By having PWM at each club and meetings between the PWMs they are also able to support each other:

So it’s interesting and when you go to these meetings with other RFL player welfare managers, I know for instance there’s about three or four clubs that I am particularly close with in terms of their welfare manager and discussing ideas and I’ll go off and call them to bounce ideas off them. (PWM 6)

I think so, its added the structure to it and I’m not very good at just operating without guidance, err, so I quite like [I: that you’ve been given that structure] and I like something to refer to and I like to know what I’m supposed to be responsible for.

Welfare support as a social norm

This was seen as the aspect that has improved most since the introduction of PWMs and has led to the greater uptake in services provided by the PWMs:

you’ve got to kind of crack the keepers in the team, the high-profile players. Once you get them on board and them doing it, well the less profile players say well he’s doing it, I should be doing it, that’s the norm. (PWM 14)

We’ve got some good leaders in our club, people like (player x) for example, is doing his (educational courses). Now (player x) is an England International .. That’s the kind of player, do you know what I mean [I: yeah, that you’re growing] exactly. Now all them players look up to him because he performs on the field, but also, he’s got his lifestyle off the field as well.

External links to professional bodies

The PWMs are provided with basic training but are not trained to provide specialist mental health services to support the players, they provide the link between the professional bodies. Sporting Chance is one of the most widely used services. They provide training courses for the PWMs, seminars and one-to one support to players who need it. They also support the PWMs ‘There have been some more serious incidents that have happened in my time here and I’ve used Sporting Chance for guidance for myself’ (PWM 4). Their services were valued highly by all the PWMs:

The amount of support they (Sporting Chance) offer to the lads, it’s vital and again in that culture shift, now that one or two lads have had help and received help and know there’s help out there, it’s encouraging others to speak up (PWM 12)

As far as career pathway element goes we have now, which has really come on leaps and bounds, by having a careers coach available…and that has been a very positive development (PWM 16)

Areas of further need in supporting player’s welfare (‘deficits’)

The PWMs felt they were well supported by the WD but that more could be provided by the RFL. This focused in particular on having more time to do the job, further financial support from the RFL and further buy in from clubs and coaches and players taking on board the help needed ().

More time to do the job

The PWMs overwhelmingly felt their role was restricted by the time they had available and that they could not do the job in the (mainly) three days a week they were paid for:

I end up working a large amount of hours every week. So, because all aspects of my role are important, I end up working a minimum of six days a week …fifty, sixty hours a week, most weeks…if I wanted to and or not be as good at my job, but because I have got professional pride in what I do I work more hours (PWM 18)

I haven’t seen my son for four days, it is very difficult for me, a massive concern for me, my wife is understanding but she is also concerned about the amount of hours I am spending at work and the amount of hours I am having to do to be in a job! (PWM 15)

Since the publication of the report (Lewis et al. Citation2016) the Super League Europe Annual General meeting have agreed that all clubs will provide a full-time PWM from the start of the 2018 season (RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2017a). Their remit will now also include assisting the Head of Youth with Academy and Scholarship players and providing support for office staff, focusing on mental health and well-being.

Further financial support from the RFL

The PWMs felt that the longer they were in the role, the more they realised what needed to be done and that the RFL needs to recognise that it is a full time role. ‘I think clubs are realising the importance of it but the money in the game is not coming to welfare’ (PWM 4). This was reiterated by PWM 18:

I believe more money should be spent in the area and that more credence needs to be given to it and guidance needs to be given to it from the governing body to actually make the area stronger because it’s only going to, it’s like a can of worms, once you start opening it, because as we’re starting to do a better job, there’s more issues being raised (PWM 18)

It’s a full-time role...if it was funded by the RFL for each club, then I would become more, the club would see it as a full-time role … instead at the moment it can be seen, even though it shouldn’t, as a part-time role (PWM 15).

I think where Player Welfare as a whole could really help is if you were centrally funded, so you’re not seen as a member of staff…If they were impartial, and have a minimum set of requirements, required skills, centrally funded by the RFL, so there is more importance placed on it… (PWM 20)

Further buy in from clubs and coaches

The respect and support the PWMs received from their clubs and coaches varied considerably, and the support of the coach in particular influenced both the time they have available to spend with players as well as how they were regarded by the players:

At some clubs there was still the attitude of some coaches that players did not need support … ‘in my day…kick him up the backside, that’s what they need and all this type of thing’… (PWM 16) and on the whole this was when coaches were ex-players who had not needed welfare support and perhaps came from an era where providing welfare support was not the norm.

There will be a big argument again this morning about what went on yesterday (the team losing). If they read the welfare manual, they cannot make decisions about fines on people’s behaviours etc. or anything else like that without me being present. They just do what they like. (PWM 14)

I think the main difficulty is actually getting everybody else at the club to understand that, you know, it is very important role and you need to be given the time to do your role correctly and not be dragged into other areas and asked to do other things that don’t actually come under your role. (PWM 11)

Player’s taking on board the help needed

For some of the PWMs it was felt that the players and not the club or coach, that were not giving welfare support the necessary time. They perceived that some players were resisting the help offered and made it difficult for the PWMs to successfully fulfil their role:

…they’re just concentrating on rugby and they think it is going to, everything is going to plan that way, they don’t think of it as being (temporary)…you’d think they’d want to come to you to ask for stuff, but they don’t you have to constantly badger them and say, yeah, that’s what I find hard. (PWM 10)

I saw somebody yesterday and it was, you know, ‘well I’m not so sure what I want to do after I stop playing’ and I said you want to stay on playing don’t you, he says ‘yeah, after I stop playing, I want to keep on playing!’ you know. (PWM 1)

I would make the PWMs in the club more senior in the role because people do not pay enough attention… and too much stuff goes on that doesn’t get reported out of fear. (PWM 5)

Discussion

The aim of the research was to explore the PWMs’ perceptions of player welfare (‘problems and needs’), how they engage with the role and what impact they believe they are having on player welfare (‘assets’), and to explore what else is needed to enhance the service (‘deficits’). The PWMs dealt with a range of issues and felt they were able to provide practical and emotional support so that the players could concentrate on their game and avoid issues such as addiction, anxiety and self-harm from escalating by signposting players on to specialised services. By having the infrastructure in place to support the players and the support of coaches and high-profile players, they were better placed to provide this support. However, they felt they did not have enough time to provide all the support the players needed and although they had begun to see a culture change to one that was more open to admitting and seeking help for problems, they needed further buy in from the RFL, clubs and players themselves. The findings, alongside the results of a players’ survey (Lewis et al. Citation2016), have been fed back to the RFL who have, through a recent Annual General Meeting responded to a number of the recommendations in the report (RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2017a) including importantly increasing the PWMs’ role from 3 days a week to full-time.

In taking a holistic ecological approach ((Henriksen, Stambulova, and Roessler Citation2011) we can approach the welfare support of athletes from many perspectives. The individual athlete will have particular welfare needs, their interactions with other players, coaches and support staff and the infrastructure provided by the governing body, right through to policies (such as the Treaty of Lisbon) will all impact on the individual athlete. The PWMs are tasked with implementing the policy provided by the RFL and facilitating links between players and coaches as well as encouraging a supportive environment between players.

The impact of the sporting environment on mental health, as perceived by the PWMs, supports the findings from previous research that the transitory nature of the career (Park, Lavellee, and Tod Citation2012), pressure to perform (Sundgot-Borgen and Torstveit Citation2004) and the pressures imposed by selection (Kornbeck Citation2017) may lead to mental health problems. The stigma attached to asking for support is, according to the PWMs, being broken down by the provision of the welfare support. The PWMs discuss a culture shift from one year to the next and this has been obtained by the ‘snowballing’ effect of one player asking for help, leading to another. This shift in culture may be important in the future success of welfare provision. The independence of the PWMs from the playing field is perhaps one of the reasons for the increased uptake in services. This does also, however, suggest that help-seeking is still hidden from those in power (club selectors, coaches) and that the PWMs act as an intermediator who is able to support the players in receiving help, but this information does not go any further. This is in contrast to Kelly and Hickey (Citation2008) study of AFL where they discussed that the collection and dissemination of players welfare needs may lead to deselection and players should retain the right to privacy. Within the RFL it appeared that whilst the PWMs may collect personal information on players they also retained confidentially. Until there is a time when there is a culture shift throughout professional sport it may be that keeping this level of confidentially is essential for the services to be successful. The PWMs also believed that role modelling, in particularly of successful players, was crucial to engaging the rest of the players. This means that the players themselves engage in interactions where they are aware of what each other is doing, but that the communication does not go up to coach or club level. The rugby players are a group for whom help-seeking may be hindered by the male macho culture surrounding the game as highlighted earlier (Steinfeldt and Steinfeldt Citation2012; Kerr and Stirling Citation2017). The idea that you can admit a weakness and a need for support, and still be a top performer, is important in changing the discussions around mental toughness and its implications both on and off the field but this idea does not appear currently to exist at all levels of the sport.

The governing body’s (RFL) acknowledgement of the need for player welfare support and their structural support for the PWMs, however, may also contribute to a reduction in fear that players will be seen as ‘mentally weak’ if they ask for support. Interestingly, the welfare policy uses the term ‘mental resilience’ rather than ‘mental toughness’. This adds to the debates of Bauman (Citation2016) and Gulliver et al. (Citation2015) above and provides support for the need for open and frank discussion of the role of mental health in elite-level sport. Whilst it is agreed with Wolanin, Gross, and Hong (Citation2015) that professionals need to be in place to assess and manage mental health problems in sport, perhaps if we can do more within the sport to remove the pressures to conform to masculine identities and allow players to discuss issues off and on the field, we may see a reduction in the prevalence of mental health problems.

The findings that PWMs believe athletes need to be free of other anxieties (such as financial concerns and future careers) supports the need to aid athletes with career transitions, through providing education and careers services, and builds on the findings of Jennings (Citation2015) and Brownrigg et al. (Citation2012). The PWMs valued the provision of these services for players, yet getting players engaged was still a struggle as there was reluctance for some players to acknowledge that their careers may end. The idea of a ‘dual career’ may not be appealing to those who only ever want to work in sport. An athlete who has a limited sense of self beyond their athletic identity will have more difficulties transitioning out of sport (Pink, Saunders, and Stynes Citation2015). Wagstaff, Fletcher, and Hanron (Citation2011) have suggested that (in line with a holistic ecological approach) we not only need to focus on individual career development, but also the organisational structures and environmental culture to support the individual. The RFL have a role to play in making education an essential part of the player’s career (just as training is compulsory so is education and personal development). The latest policy changes are beginning to move in this direction and whereas ‘forcing’ people is not motivational, making it the accepted cultural norm (by providing time and opportunities) is one way of doing this.

Due to the increased uptake and demand for their services, the PWMs were struggling to cope with the demands that the job entails. The need for the service meant that 3 days a week was insufficient to cope with the demands. The PWMs also mentioned they would also like to help younger (Academy) players who are not yet in the senior squad and those following retirement, but the resources were not in the main available. The time devoted to the job was potentially impacting on the welfare of the PWMs themselves. Access to support and a need to reduce the superfluous jobs added to the PWMs, when no one else is available, was also evident. Increasing the seniority and importance of the role may help with this. The RFL have responded to the recommendations made following these interviews with PWMs alongside a player’s survey (Lewis et al. Citation2016) in a number of positive ways. This includes making the PWMs’ position full-time, further training provided for PWMs, communicating to clubs (CEO’s, coaches and players) the importance of the PWMs’ role, formal supervision for PWMs from Sporting Chance and amendments to the policy to encourage further participation from players (RFL (Rugby Football League) Citation2017b). These are regarded as positive impacts of the research on improving practice within the structure of the governing body. In the long term as players, who have had access to welfare support as the norm, move into coaching and management we may see a further cultural shift throughout the club structure.

It is important to consider the strengths and limitations of this study. One strength is that nearly all the PWMs employed in the Super League were interviewed both at the start of the new welfare policy, and again a year later. This means that the experiences of most of the clubs are included and the effect of changes witnessed by the PWMs have been explored. It was felt the telephone interviews allowed the PWMs to talk freely as they may feel more anonymous than a face-to-face interview (Holt Citation2010). The limitations include the ‘outsider’ role of the interviewers who may have been deemed as judgemental of the Rugby League clubs and led to reluctance to discuss issues. Given more time, the interviewers could have spent time at the clubs, gaining an understanding of what it is like to work in professional rugby and developing trust and recognition with the PWMs. The qualitative data analysis is interpretive and so we need to be open to the fact that other researchers may have chosen a different questioning route and identified different thematic areas of significance in the data. The researchers all have a psychology background and the significance of mental health issues was potentially magnified both through the line of questioning and the analysis of the data as the health psychologist’s interest and understanding of this area led to prioritising issues of mental health over other welfare issues. At times, the interviews were cut short, as the PWMs had only a short time set aside to take the call reducing the opportunity to discuss issues in depth. It was felt that although some PWMs were very keen to talk and they wanted to talk about their roles and how important they perceived them to be, other interviews were more perfunctory and PWMs were just getting it out of the way. There was a concern amongst some that they should not be divulging details of issues and they were very concerned that they should not be identified. The data have been presented with as little context as possible to make sure the PWMs cannot be linked back to a specific club, however it was felt that ethically it is important that these issues are raised and that as researchers we do not hide from highlighting contentious issues.

To further address welfare support it is recommended that future research involves prolonged engagement with sports clubs to understand the role of welfare support for elite level athletes. Whilst these findings provide information on what the RFL is doing to support players, it would be interesting to know what other governing bodies are doing and the level of importance and financial support given to such services. The results provide some insights into the nature of elite level rugby league, and the issues faced by the PWMs may resonate with others working to support elite-level athletes, in particular team sports. Those working in other elite-level sporting arenas may recognise the issues raised here by the PWMs and consider how their practice compares and what, if anything, can be learnt from the experiences of the PWMs.

The pressures put upon elite-level RFL performers, as described by the PWMs, from other players, coaches, management and the public, meant that young men whilst being given a great opportunity to make a living from playing sport are also potentially being made vulnerable to the resulting pressures. This combined with the cultural norm of being ‘mentally tough’ and putting sport above all else means they are potentially compromising both their physical and mental health. The PWMs perceive their role, alongside the chaplains, as the buffer between these pressures, as they are in a position to provide opportunities to maintain a life outside of sport (both educationally and personally) and to protect them from the potential opportunities to harm themselves.

Conclusion

This study adds to our understanding of the role of welfare support within elite-level RFL and (in combination with the quantitative study) has made a significant impact on welfare provision at a policy level. The PWMs perceived they were making a valuable contribution to supporting players’ welfare through providing a bridge between the club and the professionals who can support them. They were doing this by being a constant feature at the clubs and being available to players, whenever needed. This was, in some cases, putting pressure on the PWMs themselves and the role. Since these interviews and publication of the report into welfare support (Lewis et al. Citation2016), the role has been expanded to ensure all clubs have full-time PWMs. It is apparent that as the job has progressed so players, through experiential and vicarious learning, are taking up services more frequently. The breaking down of barriers and changes to cultural norms is conducive to players seeking help, but the help needs to be there to support them. Welfare support of athletes needs to be viewed from an holistic ecological perspective, it is not just the individual athletes who may need to change their behaviour, but the club hierarchy, the governing bodies and potentially further policy changes. The welfare support of elite level athletes is still poorly understood and further investigation into how best to support the physical, psychological and emotional aspects of players is warranted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Kiara Lewis is the head of the Division of Health and Well-being and a member of the Centre for Applied Health Research at the University of Huddersfield. Kiara has a masters in Sport and Exercise Science and a PhD in engaging children into physical activity. She is an accredited sport and an exercise scientist (research) with the British Association of Sport and Exercise Scientist (BASES) and a member of HEPA (Health Enhancing Physical Activity network).

Alison Rodriguez is a lecturer in Child and Family Health in the School of Healthcare, a faculty of Medicine at the University of Leeds. Alison is a Psychologist with teaching and research supervision experience in research methods, health and critical health psychology. She has a masters in Health Psychology, a postgraduate certificate in Higher Education and a PhD in Children’s Palliative Care. Alison’s research focuses on the spiritual and psychological health and well-being experiences of individuals and their carers/family members.

Susie Kola-Palmer (PhD, CPsychol, CSci, AFBPsS, FHEA) is a senior lecturer in Psychology and the associate director of the Quantitative Research Methods Training Unit (QRM-TU), Department of Psychology, University of Huddersfield. Susie is a graduate of the National University of Ireland, Galway, where she completed her PhD. Appointed to the University of Huddersfield in 2010, Susie’s research interests are in the area of health psychology, including mental and social well-being and health risk behaviours and applied health research.

Nicole Sherretts is a postdoctoral researcher in psychology. She has experience in working with the criminal justice system in the USA. Nicole is an experienced quantitative research methodologist, and while she primarily conducts research in prisons in Pennsylvania (including those that house death row inmates), she is additionally currently on the Quantitative Work Package team for the EU-funded project None-in-Three. She has published research in criminal psychology, in the areas of: psychopathy, criminal social identity, inmate self-esteem and eyewitness identification accuracy.

References

- Agnew, D., A. Markes, P. Henderson, and C. Woods. 2017. “Deselection from Elite Austrailian Football as the Catalyst for a Return to Sub-Elite Competitions: When Elite Players Fell There is ‘Still More to Give’.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 117–136.

- Anderson, M. B. 2011. “Who’s Mental, Who’s Tough and Who’s Both? Mutton Constructs Dressed up as Lamb.” In Mental Toughness in Sport: Developments in Theory and Research, edited by D. F. Gucciardi and S. Gordon, 69–89. Oxon: Routledge.

- Bathgate, A., J. Best, G. Craig, and M. Jamieson. 2002. “A Prospective Study of Injuries to Elite Australian Rugby Union Players.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 36 (4): 265–269.10.1136/bjsm.36.4.265

- Bauman, N. J. 2016. “The Stigma of Mental Health in Athletes: Are Mental Toughness and Mental Health seen as Contradictory in Elite Sport?” British Journal of Sports Medicine 50 (3): 135–136.

- Blazina, C., and C. E. Watkins. 1996. “Masculine Gender Role Conflict: Effects on College Men’s Psychological Well-Being, Chemical Substance Usage, and Attitudes towards Help-Seeking.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 43: 461–465.10.1037/0022-0167.43.4.461

- Brooks, J., S. McCluskey, E. Turley, and N. King. 2015. “The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 12 (2): 202–222.10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

- Brownrigg, A., V. Burr, A. Locke, and A. Bridger. 2012. “You Don’t Know What’s around the Corner: A Qualitative Study of Professional Footballers in England Facing Career-Transitions.” Qualitative Methods in Psychology Bulletin14: 14–23. ISSN 2044-0820

- Cournoyer, R. J., and J. R. Mahalik. 1995. “Cross-Sectional Study of Gender Role Conflict Examining College-Aged and Middle-Aged Men.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 42: 11–19.10.1037/0022-0167.42.1.11

- Coyle, M., P. Gorczynski, and K. Gibson. 2016. “‘You Have to Be Mental to Jump of a Board Anyway’: Elite Divers’ Conceptualizations and Perceptions of Mental Health.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 29: 10–18.

- Evans, J., B. Frank, J. L. Oliffe, and D. Gregory. 2011. “Health, Illness, Men and Masculinities (HIMM): A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Men and Their Health.” Journal of Men’s Health 8 (1): 7–15.10.1016/j.jomh.2010.09.227

- Gouttebarge, V., H. Aoki and G. Kerkhoffs. 2015a. “Prevalence and Determinants of Symptoms Related to Mental Disorders in Retired Male Professional Footballers.” The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. [online]. Accessed November 16, 2016. http://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/sports-medphysical-fitness/article.php?cod=R40Y9999N00A150079

- Gouttebarge, V., G. Kerkhoffs and M. Lambert. 2015b. “Prevalence and Determinants of Symptoms of Common Mental Disorders in Retired Professional Rugby Union Players.” European Journal of Sport Science. [On-line]. doi:10.1080/17461391.2015.1086819

- Grey-Thompson, T. 2017. “Duty of Care in Sport.” Independent report to the Government. Accessed August 2, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/610130/Duty_of_Care_Review_-_April_2017__2.pdf

- Gulliver, A., K. M. Griffiths, A. Mackinnon, et al. 2015. “The Mental Health of Australian Elite Athletes.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 18 (3): 255–261.10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.006

- Hammersley, M. 1992. What is Wrong with Ethnography?. Oxon: Routledge.

- Henriksen, K., H. Stambulova, and K. K. Roessler. 2011. “Riding the Wave of an Expert: A Successful Talent Development Environment in Kayaking.” The Sport Psychologist 25 (3): 341–362.10.1123/tsp.25.3.341

- Henry, I. 2013. “Athlete Development, Athlete Rights and Athlete Welfare: A European Union Perspective.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 30 (4): 356–373.10.1080/09523367.2013.765721

- Holt, A. 2010. “Using the Telephone for Narrative Interviewing: A Research Note.” Qualitative Research 10 (1): 113–121.10.1177/1468794109348686

- Howes, L. M. 2017. “Developing the Methodology for an Applied, Interdisciplinary Research Project: Documenting the Journey toward Philosophical Clarity.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 11 (4): 450–468.10.1177/1558689815622018

- Jennings, S. 2015. “Are Educationally Prepared Rugby Players Better Equipped to Enter the Transition Process and into Life after Rugby?” MBA Dissertation, Dublin Business School.

- Kelly, P., and C. Hickey. 2008. “Player Welfare and Policy in the Sports Entertainment Industry: Player Development Managers and Risk Management in Australian Football League Clubs.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 43 (4): 383–398.10.1177/1012690208099873

- Kerr, G. and A. Stirling. 2017. “Issues of Maltreatment in High Performance Athlete Development: Mental Toughness as a Threat to Athlete Welfare.” In Routledge Handbook of Talent Identification and Development in Sport, edited by J. Baker, et al., 4-9–420. New York: Routledge.

- King, N. 2012. “Doing Template Analysis.” In Qualitative Organisational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges, edited by G. Symon and C. Cassell, 11–22. London: Sage.

- King, N., and C. Horrocks. 2012. Interviews in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- King, N., J. Melvin, J. Brooks, D. Wilde, and A. Bravington. 2013. Unpicking the Threads: How Specialist and Generalist Nurses Work with Patients, Careers and Other Professionals and Each Other to Support Cancer and Long Term Condition Patients in the Community. Project report. University of Huddersfield.

- Kornbeck, J. 2017. “Bosman and Athlete Welfare: The Sports Law Approach, the Social Policy Approach, and the EU Guidelines on Dual Careers.” Liverpool Law Review 38: 307–323.10.1007/s10991-017-9203-9

- Lewis, K., A. Rodriguez, S. Kola-Palmer and N. Sherrets. 2016. “Super League Player Welfare Study: A Mixed Method Evaluation.” University of Huddersfield. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/29771/.

- Light, R. 2007. “Re-Examining Hegemonic Masculinity in High School Rugby: The Body, Compliance and Resistance.” Quest 59 (3): 323–338.10.1080/00336297.2007.10483556

- Maxwell, J. A. 2011. “Paradigms or Toolkits? Philosophical and Methodological Positions as Heuristics for Mixed Methods Research.” Midwest Educational Research Journal 24 (2): 27–30.

- McCluskey, S., J. Brooks, N. King, and K. Burton. 2011. “The Influence of ‘Significant Others’ on Persistent Back Pain and Work Participation: A Qualitative Exploration of Illness Perceptions.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 12: 95–243.

- Morgan, A., and E. Ziglio. 2007. “Revitalising the Evidence Base for Public Health: An Assets Model.” Promotion & Education 14: 17–22.10.1177/10253823070140020701x

- Murphy, E., R. Dingwell, D. Greatbatch, S. Parker, and P. Watson 1998. "Qualitative Research Methods in Health Technology Assessment: A Review of the Literature". Health Technology Assessment 2 (16): 1–277

- Murray, A. D., I. R. Murray, and J. Robson. 2014. “Rugby Union: Faster, Higher, Stronger: Keeping an Evolving Sport Safe.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 48: 73–74.10.1136/bjsports-2012-091844

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–13.

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., K. M. T. Collins, and R. K. Frels. 2013. “Towards a New Research Philosophy for Addressing Social Justice Issues: Critical Dialectical Pluralism.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 7 (1): 9–26.10.5172/mra.2013.7.1.9

- Park, S., D. Lavellee, and D. Tod. 2012. “Athletes’ Career Transition out of Sport.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 6: 22–53.

- Pink, M., J. Saunders, and J. Stynes. 2015. “Reconciling the Maintenance of on-Field Success with off-Field Player Development: A Case Study of a Club Culture within the Australian Football League.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 21: 98–108.10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.11.009

- Ray, J. M. 2009. “A Template Analysis of Teacher Agency at an Academically Successful Dual Language School.” Journal of Advanced Academics 21 (1): 110–141.10.1177/1932202X0902100106

- RFL (Rugby Football League). 2015. “RFL Player Welfare Policy 2015-Onwards.” Player Welfare Standards 2015-2021. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://media.therfl.co.uk/docs/PLAYER%20WELFARE%20POLICY%20STANDARDS%20-%202016%20final%20PDF.pdf

- RFL (Rugby Football League). 2017a. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://www.rugby-league.com/article/50559/betfred-super-league-clubs-agree-full-time-player-welfare-provision

- RFL (Rugby Football League). 2017b. “Tier 1-3 Operational Rules 2017.” Accessed December 20, 2017. http://www.rugby-league.com/operational-rules/mobile/index.html#p=455

- Shannon-Baker, P. 2016. “Making Paradigms Meaningful in Mixed Methods Research.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 10 (4): 319–334.10.1177/1558689815575861

- Smith, B. 2018. “Generalizability in Qualitative Research: Misunderstandings, Opportunities and Recommendation for the Sport and Exercise Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 137–149. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221.

- Smith, B., and K. R. McGannon. 2017. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities in Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise 1–21. doi: 10.01080/1750984x.2017.131357.

- Sparkes, A. C., and B. Smith. 2014. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health. From Process to Product. Oxon: Routledge.

- Steinfeldt, J. A., and M. C. Steinfeldt. 2012. “Profile of Masculine Norms and Help-Seeking Stigma in College Football.” Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 1 (1): 58–71.10.1037/a0024919

- Sundgot-Borgen, J., and M. K. Torstveit. 2004. “Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Elite Athletes is Higher than in the General Population.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 14 (1): 25–32.10.1097/00042752-200401000-00005

- Teddie, C., and A. Tashakkori. 2011. “Mixed Methods Research: Contemporary Issues in an Emerging Field.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed, edited by N. K. Denzin and W. S. Lincoln, 285–299. Thosand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., D. Fletcher and S. Hanron. 2011. “Positive Organisational Psychology in Sport.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology S (2): 87–103.

- Watson, J. 2005. “College Student-Athletes’ Attitudes toward Help-Seeking Behavior and Expectations of Counseling Services.” Journal of College Student Development 46 (4): 442–449.10.1353/csd.2005.0044

- Williamson, J. 1995. “Hard-Core Rugby: Tough Men in a Tough Game.” Reference Reviews 9 (5): 36.

- Wolanin, A., M. Gross, and Eugene Hong. 2015. “Depression in Athletes: Prevalence and Risk Factors.” Current Sports Medicine Reports 14 (1): 56–60.10.1249/JSR.0000000000000123

- Wood, S., L. K. Harrison, and J. Kuchorska. 2017. “Male Professional Footballers’ Experiences of Mental Health Difficulties and Help-Seeking.” The Physcian and Sportsmedicine 120–128. doi: 10.1080/009/3847.2017.1283209.