ABSTRACT

Recognising the limited literature detailing the practical application of co-production principles and practices within sport, exercise and health research, critical reflections on co-production principles and practice are shared here, drawing on two participatory action research (PAR) projects in the United Kingdom (UK). Co-production and PAR are distinguished, and their commonalities discussed. Both projects were facilitated by occupational therapists and concerned with health inequities and social justice. The Voices for Inclusive Activity project brought disabled people together online to explore more accessible and inclusive approaches to evaluate disability sport and physical activity. The Positive Mental Attitude project took place with a community-based football league for people with experience of mental distress and explored the nature and value of participation. Both projects involved researching with people who are often excluded from research. Addressing power imbalances can function to engage marginalised people in processes of knowledge production and enable social justice. Co-production offers useful principles that are democratic, inclusive, collaborative, and participatory, but the process is not straightforward. The reflections within this paper focus on the challenges and opportunities the first and second authors faced as facilitators of co-produced research. Participant and co-researcher quotes reveal how participatory methods and approaches address gaps in experiential knowledge of exclusion and marginalisation. The potential for co-produced research to influence policy and practice is outlined.

Introduction

Critical reflections on facilitating the co-production of two participatory action research (PAR) projects are shared within this paper: The Voices for Inclusive Activity (VIA) project and Positive Mental Attitude (PMA) project. Rather than prescribing a specific method for co-production, complexities are discussed using critical reflections on learning and practical insights. Both PAR projects were facilitated by occupational therapists: health professionals who focus on what people do and how this relates to their health and well-being. Current sport and physical activity workforce policy in England acknowledges the relevance of occupational therapy (Sport England Citation2018). The profession’s focus on what people do is based on a broad definition of occupation, as ‘ … a group of activities that has personal and sociocultural meaning, is named within a culture and supports participation in society’ (Creek Citation2010, p. 25). Occupational therapists work with people to enable participation in the activities and occupations of their everyday lives. This includes participation in sport and physical activity, and also research. As therapists, they use a range of approaches to facilitate participation, tailored to individuals and communities through action, dialogue, reflection and professional reasoning (Creek Citation2014).

While the role of occupational therapists within the delivery of sport and physical activity has already been recognised, the authors assert the contribution they can make within sport and physical activity research.

Co-production and PAR

Within this paper, it is argued that the practices of co-production sit well within a PAR approach, yet first it is useful to distinguish between the two.

There is no universally agreed definition of what co-production is; Smith et al. (Citation2022) describe attempts to define as ‘futile and unnecessary’ (Pg. 3). Previously, Williams et al. (Citation2020) have guarded against attempts to define, noting examples that have neglected to acknowledge an ethical and political imperative, contributing to the notion of ‘cobiquity’: where any form of collaboration may be labelled as ‘co-production’ (Williams et al. Citation2020). It remains a contested field, although notable recent attempts have been made to advance definition through a typology of co-production, which defines it as a way of working grounded in principles such as shared power, respect, trust, equality, flexible thinking, valuing relationships and reciprocal learning (Smith et al. Citation2022). Generally, co-production involves partnership working towards a mutually defined aim, where everyone connected with an issue plays an active part, and existing skills, experience and knowledge are valued and utilised. Co-production is used in evaluation, policy making, service development and provision, but can also be applied within research (Beresford et al. Citation2021; Glynos and Speed Citation2012).

Partnership is enabled through an inclusive research process, encouraging meaningful engagement, greater relevance and significance of research focus and intended outcomes (Atkin, Thomson, and Wood Citation2020). Within this collaborative approach, diversity is respected, every effort is made to ensure power is shared among the group and attention is paid to reciprocity (Smith et al. Citation2022). The co-production of research requires the acknowledgement of potential power imbalances between co-researchers, with the danger of replicating traditional, profession-led approaches where resulting policies and services serve to further marginalise (Layton Citation2014; Atkin, Thomson, and Wood Citation2020). Such approaches, where the problem is individualised and the professional offers the solution, have long been challenged by disability rights activists and the service user movement (Oliver Citation2002).

While co-production has existed for almost five decades it is a more recent phenomena within sport, physical activity and health research; yet it has been readily embraced for its potential to challenge understandings and generate new knowledge by involving those traditionally marginalised from research (Smith et al. Citation2022). Despite this developing interest towards a ‘participatory turn’, Smith et al acknowledge ‘a dearth of literature comprehensively detailing co-production relevant to research’, particularly in co-production that is equitable and experientially informed (2022, p2).

Equally within occupational therapy research, the move towards such practices is relatively recent, despite the recognised synergy between the co-production of research and the person-centred and partnership working principles underpinning the profession (Atkin, Thomson, and Wood Citation2020; Harries, Barron, and Ballinger Citation2020; Momori and Richards Citation2017).

In comparison with co-production, PAR is focused on participation through recurrent cycles of planning, action and reflection (Macdonald Citation2012), defined as:

“… a process in which ‘we’, researchers and participants, systematically work together in cycles to explore concerns, claims or issues that impact upon or disrupt people’s lives”

As a research approach, PAR involves specific processes, including agreeing methods, gathering and analysing data. PAR also involves cycles of planning, action and reflection, with learning from each cycle contributing towards further planning and action (Koch and Kralik Citation2006). While this structure distinguishes PAR from co-production, there are parallels with co-production principles, such as developing and maintaining equitable partnerships by engaging experiential knowledge and skills (Smith et al. Citation2022; Beresford et al. Citation2021).

The roots of PAR lie in activism (Bryant et al. Citation2019; Freire Citation2014). Examples within both sport and physical activity and occupational therapy research demonstrate the use of PAR and co-production to address matters of social injustice and exclusion. Sport for development researchers have asserted the value of PAR in developing, implementing and evaluating sport and physical activity programmes (Holt et al. Citation2013; Rich and Misener Citation2020) and in co-producing guidance with health professionals (van de Ven, Boardley, and Chandler Citation2022). Others discuss the challenge of transforming power relations to support the engagement of marginalised people (Frisby et al. Citation2005; Spaaij et al. Citation2018). Across both sport and physical activity and occupational therapy PAR research, creative methods have been used to subvert conventional approaches to knowledge production. For example, podcasting (Smith, Danford et al. Citation2021a), photovoice (Birken and Bryant Citation2019; Hayhurst and Centeno Citation2019; McSweeney et al. Citation2022), WhatsApp© conversations (Dania and Griffin Citation2021), World Cafés (Pettican, Speed et al. Citation2021) and go-along interviews (Pettican et al. Citation2022). Within the occupational therapy literature, the principles and practices of PAR have also been related to professional skills, philosophies and knowledge translation (Wimpenny Citation2013; Kramer-Roy Citation2015; Bennett et al. Citation2016).

Reflexivity in co-production/PAR

Reflection is both integral to occupational therapy practice and a fundamental stage within the PAR cycle (Andrews Citation2000; Koch and Kralik Citation2006), yet the significance of reflection and reflexivity is less acknowledged within co-production literature. Reflection facilitates ‘ … learning and developing from experience, resulting in a changed perspective’ (Andrews Citation2000, p. 396). Whereas reflexivity refers more specifically to the systematic evaluation of a researcher’s own impact on processes of partnership working and relationship dynamics within a project (Mansfield (Citation2016). Within both projects, reflexivity has involved reflective discussions with co-researchers during the processes of research planning and after data collection, by recording field notes and activities. This paper is based upon the distinct issues highlighted within these episodes of reflection.

Smith et al. (Citation2022) call for more reflexive accounts on the processes of undertaking co-production, to illuminate alignment between motivations for co-producing research, sharing of power and decision-making, along with the barriers and facilitators of co-produced research. This is where the authors hope this paper will contribute new knowledge, in offering reflexive insight into the practices of co-produced research underpinned by the processes of PAR, from our perspectives as occupational therapists, situated within an academic context.

Limitations

In the dissemination of both projects, shared actions and reflections have been prioritised, sustaining the voices and perspectives of collaborators and co-researchers. However, the authors recognise this paper will reach a predominantly academic audience and are aware of its limitations in not being co-produced.

Language and terminology

In both projects, language was discussed and, sometimes, contested. The term disabled people is used in this paper to reflect the UK social model of disability, although critique of this conceptualisation is acknowledged (Smith, Mallick et al. Citation2021b; Brighton et al. Citation2021). Some co-researchers within the VIA project expressed a preference for person-first language (person with a disability), reflecting how disability is described in some international contexts (Smith, Mallick et al. Citation2021b). In the PMA project, the steering group discussed and agreed on the term people with experience of mental distress, rather than descriptive biomedical terms such as psychiatric disorder or mental health problem. This was intended as an inclusive recognition that, for some people, mental distress is transitory, whereas diagnostic terms can feel like a permanent label. Similarly, some co-researchers have chosen pseudonyms while, after discussion of the implications, others preferred to use their real names in publications. Within this paper we have employed the term marginalised people, a descriptor used elsewhere to refer collectively to those who are subject to ‘othering’ from dominant and mainstream society because of ‘perceived difference’ (Duncan and Creek Citation2014, p. 460).

Method

In this section, each project is presented within a deliberately descriptive account, in response to the lack of reports detailing the intricate practicalities of co-producing sport, exercise and health research (Smith et al. Citation2022).

The two projects were undertaken within the context of PhD programmes by the first (Anna Pettican) and second (Beverley Goodman) authors. Anna has completed her PhD and is now supervising Beverley’s PhD, which is now in the data analysis stage. The other authors represent the supervisory teams of both projects.

The six reflective themes are discussed as aspects of facilitating co-production within PAR. They broadly reflect the research process and are organised according to the stages involved, from problem identification to dissemination (Hickson Citation2008). The VIA project themes, Building partnerships, Sustaining accessibility and Trusting the process, are focused on the commencement of the project, so are presented first. The themes from the PMA project, Making spaces, Actions and words and Decisions about data, span the research process and are therefore presented second. The significance of facilitation within co-production arose during an early experience of dissemination by co-researchers on the VIA project. As part of a co-production training workshop for disability sport and physical activity organisations, co-researchers were invited to share their experiences of the research process. They co-designed their section, presenting their experiences of co-producing the VIA project within themes, which have contributed to those expressed within this paper. For the PMA project, Anna engaged in structured reflective discussions, two with steering group members and one with a participant. These conversations aligned with a collaborative cycle of learning through doing (Bryant et al. Citation2012, p. 27), but have also informed the themes within this paper. For example, the stage of ‘Coming together’ from this cycle relates to the theme of Making spaces.

Reflective themes

The Voices for Inclusive Activity (VIA) project

A group of seven people, including five disabled people and one family carer, were co-researchers on the project that sits within Beverley’s PhD, named Voices for Inclusive Activity by co-researchers. The overall aim of the VIA project is to identify more accessible and inclusive approaches of evaluating sport and physical activity. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the group was established online, working together on their research questions, designing methods and collecting data. Although not the desired location for co-production, this was a pragmatic response necessitated by pandemic restrictions (Langley et al. Citation2021). From reflections on the process undertaken, three themes have been identified: the first, Building partnerships, discusses the early stages of building the research team. Related to this is the second theme of Sustaining accessibility, which discusses challenges and opportunities in working with a collaborating organisation and mediating digital exclusion. Finally, Trusting the process explores the uncertainty of the PAR process and how this was experienced by co-researchers.

Theme 1.1: building partnerships

Relational ethics are key to effective co-production and PAR (Smith et al. Citation2022). This requires the proactive building of relationships with partners, who contribute vital experiential expertise to the process of co-learning and knowledge production, disrupting the conventionally hierarchical nature of research. Such partners may also facilitate connections with other potential collaborators (Mansfield Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2022).

Beverley’s PhD began in 2019 with a scoping exercise that involved physically meeting and building relationships with regional providers of sport and physical activity opportunities for disabled people. Beverley was introduced to most of these providers by a professional working in the disability sport and physical activity field. However, in early 2020, COVID-19 restrictions barred face-to-face research and all subsequent activity proceeded online.

Beverley identified an individual collaborator working for a regional disability sport and physical activity provider, who agreed to assist with the recruitment of co-researchers. Working together, they persisted with recruitment efforts at a time when inequities and marginalisation in practice and research were exacerbated by pandemic restrictions (Beresford et al. Citation2021).

Although PAR is typically located in a community familiar to co-researchers (Hand et al. Citation2019), for the VIA project there was no comfortable environment in which to meet with potential co-researchers and spend time developing relationships, which could have had implications for power dynamics. An online space was created that successfully engaged people who might not ordinarily be involved in research. The collaborator used existing means of contact to introduce the project to potential co-researchers, usually text message or phone call, and established Beverley as a trusted contact.

The VIA project aligned with what was happening elsewhere in response to COVID-19 restrictions. Although valid concerns were raised about digital exclusion and the potential for online methods to further marginalise people (Allam et al. Citation2021), this was mediated by the efforts of the collaborator’s organisation, which was supporting people to remain active with online physical activity and social opportunities, supplying equipment and data to access these sessions and introducing participants to using the online meeting platform, Zoom©. There was fortuitous alignment with Beverley’s research into online meeting platforms, which found Zoom© the most accessible for collaboration (Daniels et al. Citation2019).

Beverley held initial conversations with potential co-researchers on Zoom© to discuss the project, what it might involve, to obtain consent to proceed and explore any additional support needs. The collaborator joined in one of these meetings to support communication and relationship building with the potential co-researcher and their family carer. Every effort was made to avoid coerced participation by ensuring potential co-researchers were informed about the project (Beresford Citation2013a; Curtis Citation2018). One person declined to participate, expressing concerns about the academic nature of the project. Although reassurance may have been provided to this potential co-researcher, the decision was clearly expressed. This was accepted to avoid any coercion that may have arisen due to the potential co-researcher’s relationship with the collaborator (Curtis Citation2018; Gopichandran Citation2020).

Five of the seven co-researchers were connected through the collaborator but did not know each other well. One co-researcher became involved via their connection with a different organisation and had no previous contact with the other co-researchers. Beverley only knew the co-researchers through initial project introductions. Relationships were built across and among the group using introductions and icebreakers. For example, individual co-researchers introduced themselves by sharing an object representing their interests on screen. Co-creating ways of working included scheduling times to socialise, to build a sense of community among co-researchers. Their developing partnership is illustrated in Box 1, below, when co-researchers discussed the process of working together. This example also demonstrates how individual strengths might contribute to collective progress and how mutual benefit may come to be recognised.

Karen: We all have different strengths; we work quite well as a group together.

Vanessa: It’s like we’re really in our zone now and it’s just fabulous, honestly, I love it.

Fiona: And that’s why I think, Bev, you shouldn’t be worried about there being a couple more groups, because I feel like we’re so into it now, that it’s not going to make much of a difference […] it’s for all our benefit and the benefit of the project.

This first reflective theme has offered insights into how partnerships were developed within the VIA project and discusses ethical tensions around engaging with collaborators. This extends into the second theme, which further explores the role of collaborators in enabling access to involvement in research.

Theme 1.2: sustaining accessibility

All co-researchers were involved in considering accessibility throughout the VIA project, enabling each other to participate at every stage of the research process; a vital consideration in ensuring access to knowledge production (Garbutt et al. Citation2010; Nind Citation2017). However, it was also necessary to ensure that information used to introduce the project to potential co-researchers was available in a range of formats (Garbutt et al. Citation2010). While all information was available in written and video format, according to potential co-researchers’ accessibility needs, the collaborator recommended the production of Easy Read information, and to ensure all email communications were written in Plain English.

Negotiating how and where co-researchers come together to create a safe and collaborative space is integral to the accessibility and inclusivity of PAR (Bryant et al. Citation2012). The effectiveness of the shared space can be affected by group size and guidance on online facilitation suggests 6–8 people as most accessible (Daniels et al. Citation2019). Together, the seven co-researchers collaborated to find a day, time, duration, and frequency of meeting that suited everyone, and met for nine monthly discussion groups to plan the project, with two additional social sessions and subsequent meetings to discuss data analysis. Beverley arranged individual catchups with co-researchers who could not attend groups: to provide updates, elicit thoughts and suggestions, and maintain working relationships.

The use of digital communication is likely to remain as the project continues, because of the advantages stated by co-researchers, including increased reach and accessibility (Allam et al. Citation2021; Hickey et al. Citation2021). Co-researchers indicated how difficult it would have been to participate in person, due to personal schedules, the demands of travel and the requirement to negotiate adjustments for a physical meeting. However, as happened in this project, adaptations may still be needed for an online environment, such as scheduling comfort breaks, using small discussion groups, enabling contribution via text and direct message and sending documents by post before meetings.

Time was set aside for co-researchers to discuss and decide what role Beverley should take on the project. They negotiated Beverley’s role as facilitator, distinct from a leader, in line with Hand et al. (Citation2019), putting in place the practical arrangements to come together, discuss and focus on the issues of concern. As facilitator, Beverley was responsible for arranging the sessions and creating a programme in response to the group’s requests and suggestions. The co-researchers had many other responsibilities drawing on their time, so this approach ensured energies were focused on sharing and developing ideas. Rather than undermining the democratic aspect of participation, this practical approach also helped to counter some of the challenges in maintaining progress between the very productive discussion group sessions. To ensure productivity during and between sessions, the group found solutions to access issues, which included:

producing accessible agendas for discussions

reviewing key points from the last meeting at the start of each session

agreeing clear tasks to be discussed in breakout groups.

Over the course of the discussion groups and at their own pace, co-researchers demonstrated affinity with tasks according to their experiences and availability, and those that would play to but also grow individual strengths, echoing capacity-building approaches (Vega-Córdova et al. Citation2020; Egid et al. Citation2021). Within Box 2, Fiona reflects on how co-researchers took responsibility for particular aspects of the project. This connects with the theme of Sustaining accessibility, as tasks were appropriate to each individual’s capacities and preferences, enabling involvement that suited them. For example, one co-researcher had previous experience of survey design, two had established networks of contacts with funders and providers, while two others worked together to select Easy Read images and test accessibility of the language used.

“It was always going to be difficult to pin down the [research] question and roles of everyone in the research group. We’ve got our tasks for next time, and […] I can see sort of where it’s going now. The thought sharing process is difficult to get your head around but now we’ve got specific roles we can think about what we’re doing. Excited to see where it goes”.

In this theme, accessibility is therefore not only concerned with access to the project, but also facilitating the group’s access to their own valuable resources to strengthen co-production.

Theme 1.3: trusting the process

The negotiated and, at times, ‘messy’ nature of participatory research, where knowledge is built through collaboration and is not reliant on a script or formula, is well recognised as a necessary ‘rite of passage’ for PAR and co-production (Cook Citation2009). Within the VIA project, participatory processes gave scope to think outside of the conventions of what research should be; co-researchers were integral to the creative process of forming the research design. A deliberately open approach led to feelings of uncertainty, yet through co-researcher collaboration, trust in the process emerged, as demonstrated in Vanessa’s reflection within Box 3.

“I told my friend, there’s this lovely group and we are making something. It feels like we’re making a cake, like we had loads of ingredients, we weren’t too sure, we were in the cupboard. We had all this choice and now we’ve gone, well we’ll have a bit of that and a bit of that and we’re not necessarily going to use that one, even though it’s there, and we’ve made the cake batter. That’s what it feels like – now we’re waiting for the oven to warm up, and we can cook the cake”.

The research proposal, including research questions and ideas for collaborative data gathering, emerged via a discursive approach necessitated by the meeting format but recommended within participatory research (Freire Citation2014). Within two online breakout rooms, co-researchers explored the overarching issue guided by a series of broad questions. By considering who the research was for, who should be involved and what should be asked, co-researchers worked through the process of designing a research proposal. As decisions were made, any lack of certainty about project direction was overcome. Beverley facilitated feedback of ideas to the whole group, giving space for any disagreement to be aired. A commitment to including and embracing the diversity of co-researchers requires space for open dialogue, challenge and compromise (Atkin, Thomson, and Wood Citation2020). On the few occasions where conflict or doubt occurred, this was worked out through these facilitated discussions until a consensus was reached. Co-researchers commented on the value of hearing and considering alternative perspectives to their own, which was a welcome and constructive development within the collaborative process (Williams et al. Citation2020). One example of seeking alternative perspectives came from the suggestion from co-researchers to engage funders and providers of disability sport and physical activity as participants. For Beverley as facilitator, this was an unexpected turn; she had considered involving such groups as stakeholders but had assumed co-researchers would want to centre the voices of disabled people. The need for trust in the process was reciprocated across all co-researchers as the argument was made for how involving this new group of participants would establish existing national and regional contexts and help identify current practice.

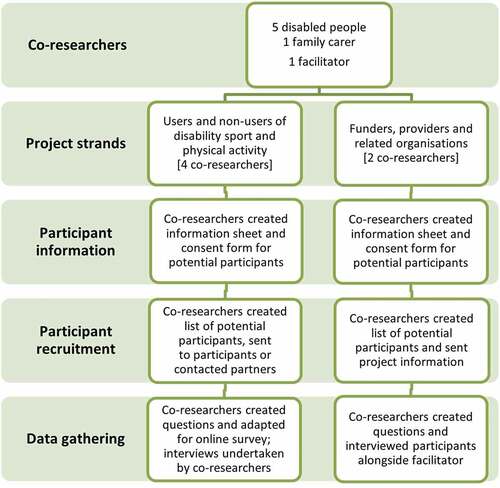

Thus, the group decided to split the project into two strands (see ). One strand (two co-researchers) explored evaluation with disability sport and physical activity funders, providers, and related organisations. The remaining group members (four co-researchers) felt more comfortable engaging with users and non-users of disability sport and physical activity. In each strand, potential methods were discussed; while any method can be used within a PAR project, co-researchers were aware the research needed to be feasible and achievable in light of COVID-19 restrictions. Individual online interviews were agreed to engage funders, providers and related organisations, while accessibility was a vital consideration for users and non-users of physical activity. In both strands, questions were formulated by co-researchers. For the users and non-users of physical activity, co-researchers adapted the questions for use in a survey (delivered via Qualtrics), for individual interviews and for focus groups, to offer further choice about participation. Information sheets and consent forms for each group of participants were also co-created within the subgroups. Co-researchers tried out interview questions with each other and one co-researcher shared their own tips for interviewing, from previous experience. Most co-researchers have been involved within the processes of participant recruitment and data gathering, incorporating elements of participatory analysis. The analytical process can be a point of challenge within participatory research due to the potential complexity and volume of information to be handled, the time this stage requires, and how this affects the ability to respond to co-researchers in a timely fashion (Frisby et al. Citation2005; Nind Citation2011; Liebenberg, Jamal, and Ikeda et al. Citation2020). Extraction and analysis of data requires practices and processes that are difficult to co-ordinate across a range of people with widely different experiences and knowledge. Often it is more pragmatic for teams of researchers to work separately, before coming together to compare outcomes. Having discussed the practicalities, co-researchers arrived at a compromise where their reflections on data collection activity are used as an initial point of analysis. At the end of each data gathering session, co-researchers undertake a process of reflection, informed by Driscoll’s reflective framework (Driscoll Citation2007).

There were simultaneous reflective processes happening, as Beverley had been keeping a reflexive diary from the earliest stage of the project to interrogate how any privilege, assumptions and position shaped the collaborative process, while co-researchers were encouraged to engage in this verbal form of reflexivity (Egid et al. Citation2021).

The VIA project provided a new opportunity for productivity, occupational and social engagement at a time when COVID-19 restrictions had widespread and significant impacts on disabled people’s access to sport and physical activity participation (Activity Alliance Citation2022). By Trusting the process of collaborative research, co-researchers could direct a research project in ways meaningful to them, while pursuing their ultimate aim of improving opportunities for disabled people’s participation in sport and physical activity.

Onward stages of the research process will now be outlined and discussed in relation to the PMA research project.

The Positive Mental Attitude (PMA) research project

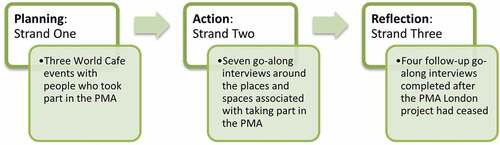

This research project was co-produced by people with experience of mental distress who were participating in a community-based football league, known as the PMA Sports Academy, with Anna. Together they explored the nature and value of their participation in the football league. The project commenced by establishing a research steering group, who designed, gathered and analysed data from three World Café events and a series of go-along interviews from 2010–2015 (see ).

The project’s findings have been reported elsewhere (Pettican, Speed et al. Citation2021, Citation2022). Three reflective themes on co-production from the PMA project are presented here: Making spaces, Actions and words, Decisions about data.

A World Café brings people together to share and discuss ideas around a table, with refreshments available (Brown and Isaacs Citation2005). The steering group adapted the structure so at the three events, players moved around the tables freely, recording their thoughts and discussions directly on tablecloths in different ways. The steering group also planned and agreed go-along interviews (Carpiano Citation2009; Garcia et al. Citation2012; Castrodale Citation2018) as a method to explore the places that participants identified as important. The term go-along was deliberately employed in acknowledgement that ‘walking interview’ is exclusionary (Evans and Jones Citation2011). These interviews involved movement within an agreed geographical area associated with the PMA. The specific pace and route were decided by participants, but vehicle use was not permitted. This method was particularly relevant because participation in the PMA was synonymous with being outdoors and frequenting specific places. Participants co-produced knowledge by shaping the direction (both literally and metaphorically) of the 11 interviews. The method was inherently representative and democratic, which are important considerations for PAR (Mikulak et al. Citation2022). Although Anna was able to suggest research methods as a researcher, this knowledge was balanced carefully with listening to other members’ views about what was needed from each strand and how participation might be enabled.

Theme 2.1: making spaces

Whereas Beverley had to create an online space for collaborative research, Anna was able to access a physical space to build relationships with PMA players and staff. She visited frequently on an informal basis, going along to watch tournaments and joining in warm-ups and training activities. She saw this as engaging in co-occupations to support the co-production process (Bryant, Pettican and Coetzee. Citation2017). Participating in co-occupations refers to two or more people sharing engagement in an occupation (Pickens and Pizur-Barnekow Citation2009). Participating in existing structures and occupations, such as training sessions and league meetings, provided important opportunities to learn about the people, environments and occupations that made up the project setting. It also provided opportunities for learning and adopting local terminology, which ensured that language did not become a barrier to the research process (Bondy Citation2012). Thus, connecting with steps made in the VIA project to enable access to knowledge production. For example, participants in the PMA were referred to as players, as an intentional move away from terms used elsewhere (psychiatric patients, service users). Gradually, a core group of 6–8 players decided to meet as a steering group. The group made space to meet alongside the PMA’s existing structures and activities, typically following a football training session or match, to reduce travel costs and time (Bryant et al. Citation2012).

Making spaces is an ongoing process of negotiation, reflecting how power needs to be shared in co-production. Steering group membership shifted repeatedly, evolving into a dynamic and fluid collective of players. There were times when players did not actively participate in the group, due to personal and external circumstances, and other times when the same players were directly and actively involved. The group was an anchor for people to make choices about joining and leaving as their ability and/or capacity fluctuated. These shifts prompted new ethical considerations, requiring pragmatic thinking about how to carefully balance means and ends in PAR (Robertson and Griffiths Citation2012). For example, holding steering group meetings in an open public café space was preferred by members, but posed potential confidentiality issues. When players in the PMA project were absent for steering group meetings, Anna re-introduced their ideas and insights into discussions at pertinent points, using their words rather than providing her interpretation. Anna aimed to protect and ensure the representativeness of the project by building on successive detailed discussions and working to ensure voices were sustained despite absence. When adaptation, involvement, representation and choice come together, there are implications for which research activities are valued and why. For example, one player liaised directly with Anna about steering group meeting times and locations by text message, to support the project’s momentum. He reminded other players to attend and unlocked the venue if required, but said very little in discussions. As facilitators, Anna and Beverley valued and respected these and similar choices about participation. This offers another perspective on Making spaces, considering how refining the research drew on players’ direct experiences of teamwork, using team nicknames and knowing who might need extra support and when. This experience was helpful for the project in two ways. Anna was positioned as a minority outsider fitting into their (majority) ways of doing things. This addressed somewhat the power imbalance that needs to be challenged through co-produced research (Smith et al., Citation2022). The players had established ways of working together: they knew who might need meeting reminders, who might require extra space some days, and who was good at making the tea. This undoubtedly led to a collaborative research experience, as Keith reflected on during the discussion with Anna, shown in Box 4:

‘Usually in set ups you have people who are way up there and people who are way down there. Like even [names a league-mate] who I used to have a lot of trouble with […] he’d just get a bit annoying […] the coaches always taught me to have more patience […] we’re all at different stages as far as technical ability goes you know. Some have learning disabilities and some have mental health issues […] so [at the time of the research project] we had all uh learnt to bounce off each other and not use it as a weapon. My weakness could be their strength and vice versa. I never knew none of these skills before’.

Theme 2.2: actions and words

The data gathering methods of the World Cafés and go-along interviews in the PMA research were chosen by the steering group, who carefully considered how players’ actions might shape the words emerging from the project. The World Café events recreated the accessible and familiar environment of a café with the potential for flexible participation for all PMA players. For example, one player chose to contribute while seated away from the main group, writing on separate sheets which were later stapled onto the tablecloths. Connecting with the VIA project theme of Sustaining accessibility, drawing or scribing was encouraged to overcome potential literacy issues. This emphasises equity rather than equality and resists the idea that everyone must be doing the same thing in the same way (Pettican, Speed et al. Citation2021). This reflected an ongoing commitment to accommodating the everyday reality where players lived with issues such as fatigue, reduced concentration, memory impairment and paranoia. For example, a steering group member provided a clear explanation for why groups were divided between tables, to avoid triggering paranoid thoughts.

The findings from the World Cafés emphasised the community and social aspects of people’s participation in the PMA. These were explored further in the next data collection strand, where steering group members decided to engage with individuals, offering a more confidential space to show and tell their experiences of the PMA.

By adapting go-along interviews, potential participants could be included who had difficulty mobilising or being in large, open, public places (Kinney Citation2018), in an effort to make the method as inclusive as possible. For one of the go-along interviews, we met at a public location and discussed it together, like standing at a viewpoint. In Box 5, Sid shares his personal reflections on his go-along interview:

“Like this research we’re talking about […] I can remember when we started it […] all the way back in Wood Green. You know. If you asked me to go back to Wood Green and sit in the same café you know memories would start flooding back. You know which train station we got off at, which path we took, how we dispersed to go home, did I carry on when I was released from hospital”.

An unexpected challenge was potential spatial breaches of confidentiality (Kinney Citation2018), which occurred when two participants encountered people they knew. The steering group discussed what to do. They decided from that point on, a pre-interview discussion should include making an agreement about what to say if someone known to either the researcher or the participant was encountered during the interview. This approach, learning through doing and making collaborative decisions as required, was also important in the data analysis phase of the PMA research project.

Theme 2.3: decisions about data

Participatory data analysis is less common than other phases of PAR (Nind Citation2011), with the potential challenges having been previously discussed in the context of the VIA project.

However, it was decided within the PMA project to co-produce the analytical frame, working directly with the steering group. This was informed by an understanding that the players were expert in making observations, decisions, and judgements about their performance as a team and individuals in their shared activities. To facilitate analysis, the steering group decided to use a large photograph of their changing room as a visual template to organise data. This was a dynamic process, with the steering group hanging up and re-positioning tablecloth and interview data as new insights emerged. This was a relevant and helpful visual metaphor that highlighted differences in perspectives as well as commonalities, indicated by the different positionings. It was emphasised that differences in perspectives were a welcomed part of the process.

The steering group also decided to do collective analysis using small, circular-coloured stickers on the World Café tablecloths: red to depict an important point, and blue to represent a popular point. We decided where to place the stickers together. In contrast to other World Café studies, which focus on the content of written statements on the tablecloths (Fouché and Light Citation2011; Teut et al. Citation2013), visual data were analysed, considering how and where the statements had been presented and positioned (Mitchell Citation2011). Such actions enabled collaborative decisions about data. However, in respect of the co-production principle of reciprocity and mutuality, the benefits of such research must extend beyond the production of findings, as highlighted within the concluding quote in Box 6 (Diver and Higgins Citation2014; Smith et al. Citation2022).

“Yeah without it […] I would not go to the leisure centre and mix and play football at all. I wouldn’t have the confidence. I wouldn’t even been in the leisure centre […] It was a platform for me”

Discussion

The six reflective themes outlined across the two studies capture new knowledge about the practicalities, tensions and nuances that might be encountered when facilitating co-produced research.

Valuing different forms of research participation

Central to co-produced research is the use of varying approaches to enable access and make space for the design and implementation of co-produced research projects. While co-production offers a strategy for collaboration, attention must be paid to the inclusivity of research practices, the provision of accessible information, and forms of research involvement and ownership (Layton Citation2014). Such strategies aim to avoid the oppression and exclusion often experienced by people living with mental distress and disability (Oliver Citation1992). In the VIA project, creating a digital space for collaboration expanded reach and access, reducing barriers to participation, enabling co-researchers to meet more easily and to sustain engagement with the project’s fundamental purpose. The research process was proactively adapted throughout both projects to enable the participation of co-researchers, reflecting the need for flexibility, but recognising the uncertainty that may manifest without a rigid research process. Maintaining involvement and thus representation is crucial for sustaining PAR project momentum (Kramer-Roy Citation2015). It is underpinned by discussing and determining choices to engage with research activities that co-researchers feel are interesting and achievable, balanced with their other commitments and responsibilities. As such, variation in levels of involvement was expected.

The practices of maintaining working relationships with co-researchers highlight how the facilitation of PAR contrasts with approaches to participant absence in other methodologies. Indeed, rather than accepting non-attendance as an expression of a person’s feelings about the research project, a researcher using a PAR approach is likely to actively seek them out, recognising that their lives involve more than just the project and will negotiate other ways of maintaining involvement (Bryant, Pettican and Coetzee. Citation2017). However, this must be undertaken carefully, to ensure ethical principles such as autonomy are upheld (Hickson Citation2008). To sustain representation and project momentum, participation takes diverse forms that are not typically accommodated by conventional research practices.

The first three authors, as occupational therapists, see research as a co-occupation with benefits. While individuals gain from participation, local and national organisations and academic communities also benefit from the skills gained and outputs of studies. Therefore, we assert that assumptions about what constitutes ‘participation’ must be subject to a reflexive process, because this could be devaluing important aspects of working together (Bryant , Pettican and Coetzee. Citation2017). PAR involves an ongoing process of exploring assumptions about what actions and products are valued, and by whom, ensuring shared and individual choices are active and informed (Macdonald Citation2012). It also requires engagement with how power is exerted within and beyond the research. A commitment to enabling co-researchers to have as fully informed a choice as possible about their involvement and to share responsibility for knowledge production both relate to issues around power dynamics within research. The repeated plan-act-reflect cycles of PAR may involve co-researchers in any or all stages of the research process (Koch and Kralik Citation2006). Whilst PAR involves specific processes and procedures, it does not dictate data gathering or analysis methods, enabling those involved in the research to decide which methods are most accessible, inclusive, and relevant (Langhout and Thomas Citation2010).

Aligning PAR and co-production

Participatory action research arose from dissatisfaction with the narrow research subject role and a wish for active participation and collaboration, to address social wrongs and power imbalances to achieve meaningful social change (Beresford Citation2013b; Freire Citation2014; Beresford et al. Citation2021). As such, it resonates and focuses co-production to advance knowledge and understanding.

The term co-production has been adopted to describe approaches of variable standards and levels of involvement (Beresfordet al. Citation2021; Glynos and Speed Citation2012). Rather than introduce a new way of ‘doing’ co-production, the authors suggest the usefulness of PAR to support and guides co-produced research, which may be helpful for novice researchers unfamiliar with collaborative working (York, MacKenzie, and Purdy et al. Citation2021). This is highlighted within the identified reflective themes, which indicate sustained commitment to addressing power imbalances, grounding the PAR approach in trusting, equitable and respectful relationships: a principle of co-production (Smith et al. Citation2022). Aligning PAR with co-production is a valuable development, supported by Smith’s et al. (Citation2022) typology of co-production for research.

The reflective themes demonstrate that PAR can deliberately disrupt the idea that only professional academics can produce research and elucidate its suitability to researching with marginalised and oppressed groups (Koch and Kralik Citation2006; Bryant et al. Citation2010; Hand et al. Citation2019). These groups are often excluded, undermining the usefulness, authenticity and reliability of research findings when applied to them as a population (Oliver Citation1992). The purpose of both projects was to do research with people who are too often excluded from research, while simultaneously addressing issues of inequality in physical activity participation.

The authors acknowledge their privilege, operating within an institution supportive of the practice of participatory research, with both projects building on the precedent of researchers who have championed such approaches (Adomako Citation2020; Bryant et al., Citation2016, Bryant et al. Citation2019; Pettican Citation2018). It is elsewhere discussed how the wider context of research and the legacy of preference towards positivist epistemologies, sometimes evident within institutional ethics and funding processes, provide additional challenges to involving people otherwise excluded from knowledge production (Bryant , Pettican and Coetzee. Citation2017).

Such exclusion exacerbates inequalities in accessing power and resources (Redwood, Gale, and Greenfield et al. Citation2012). Even if this exclusion is unplanned or inadvertent, when policy is not informed by their experiences, their marginalised status is reinforced (Redwood, Gale, and Greenfield et al. Citation2012; Beresford Citation2013b). The findings from the PMA research project have been an important counter in this regard, highlighting the need for broader social change outside of specialist provision (Pettican et al. Citation2022). These findings are now informing policy and practice within Sport for Confidence CIC, where the first author is working with participants, coaches and national governing bodies of sport to enable participation in physical activity for marginalised populations (Pettican and Barrett Citation2017; Pettican, Bullen et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

Our critical reflections and collaborator quotes illustrate advances in knowledge and understanding for facilitators of co-produced research. Whilst we resist any notions of a manual for co-production, specific approaches such as PAR provide a supportive framework for novice researchers. We hope our perspective of research as an occupation enables future practice to focus on the subtleties and nuances of doing research together. Furthermore, co-producing research with marginalised populations has value in addressing gaps in knowledge that arise from exclusion. It provides a platform through which different experiences and understandings can not only be captured, but can contribute to a more democratic society.

Acknowledgments

Anna and Beverley would like to acknowledge the work, skills and experience of their co-researchers in undertaking the research projects described here and who would like to be mentioned by name: Tom Horey, Fiona Montgomery, Karen Oldale, Vanessa Wallace, Ryan Zammit and Mike Zammit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Activity Alliance. 2022. Annual Disability and Activity Survey 2021-2022. Loughborough: Activity Alliance.

- Adomako, E. S. 2020. Exploring the Staff and Service User Perspectives on the Impact of the Physical and Social Environment on Service Users’ Engagement in Therapeutic Activities in an Adult Acute Mental Health Inpatient Unit. Essex: University of Essex.

- Allam, A., Ballard-Ridley, S., Barrett, K., Cain, L, Serrao, C, Hutchinson-Pascal, N, et al.et al. 2021. ”Co-Producing Virtual Co-Production: Adapting to Change.” In COVID-19 and Co-Production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy, and Practice: Volume 2: Co-Production Methods and Working Together at a Distance, edited by O. Williams, Bristol: Policy Press 8 .

- Andrews, J. 2000. “The Value of Reflective Practice: A Student Case Study.” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 63 (8): 396–398. doi:10.1177/030802260006300807.

- Atkin, H., L. Thomson, and O. Wood. 2020. “Co-Production in Research: Co-Researcher Perspectives on Its Value and Challenges.” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 83 (7): 415–417. doi:10.1177/0308022620929542.

- Bennett, S., M. Whitehead, S. Eames, J. Fleming, S. Low, and E. Caldwell. 2016. “Building Capacity for Knowledge Translation in Occupational Therapy: Learning Through Participatory Action Research.” BMC Medical Education 16 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0771-5.

- Beresford, P. 2013a. Beyond the Usual Suspects. London: Shaping Our Lives.

- Beresford, P. 2013b. “From “Other” to Involved: User Involvement in Research: An Emerging Paradigm.” Nordic Social Work Research Routledge. 3 (2): 139–148. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2013.835138.

- Beresford, P., Farr, M, Hickey, G, Kaur, M, Ocloo, J, Tembo, D, Williams, O et al.(2021). ”The Challenges and Necessity of Co-Production: Introduction to.” In COVID-19 and Co-Production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy, and Practice: Volume 1: The Challenges and Necessity of Co-ProductionVol. 1. eds. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Birken, M., and W. Bryant. 2019. “A Photovoice Study of User Experiences of an Occupational Therapy Department Within an Acute Inpatient Mental Health Setting.” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 82 (9): 532–543. doi:10.1177/0308022619836954.

- Bondy, C. 2012. “How Did I Get Here? The Social Process of Accessing Field Sites.” Qualitative Research 13 (5): 578–590. doi:10.1177/1468794112442524.

- Brighton, J., R C. Townsend, N. Campbell, and T L. Williams. 2021. “Moving Beyond Models: Theorizing Physical Disability in the Sociology of Sport.” Sociology of Sport Journal 38 (4): 386–398. doi:10.1123/ssj.2020-0012.

- Brown, J., and D. Isaacs. 2005. The World Cafe: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter. San Francisco: Berrerr-Koehler Publishers Limited.

- Bryant, W., K. Cordingley, E. Adomako, and M. Birken. 2019. “Making Activism a Participatory, Inclusive and Developmental Process: A Research Programme Involving Mental Health Service Users.” Disability & Society 34 (7–8): 1264–1288. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.1613963.

- Bryant, W., K. Cordingley, K. Sims, J. Dokal-Marandi, H. Pritchard, V. Stannard, and E. Adamako. 2016. “Collaborative Research Exploring Mental Health Service User Perspectives on Acute Inpatient Occupational Therapy.” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 79 (10): 607. doi:10.1177/0308022616650899.

- Bryant, W., J. Parsonage, A. Tibbs, C. Andrews, J. Clark, and L. Franco. 2012. “Meeting in the Mist: Key Considerations in a Collaborative Research Partnership with People with Mental Health Issues.” Work 43 (1): 23–31. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-1444.

- Bryant, W., Pettican, A., Coetzee, S., et al. 2017. ”Designing Participatory Action Research to Relocate Margins, Borders and Centres. In Sakellariou, D., Pollard, N. eds., Occupational Therapies Without Borders: Integrating Justice with Practice. 2nd ed. 73–81. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

- Bryant, W., G. Vacher, P. Beresford, and E. McKay. 2010. “The Modernisation of Mental Health Day Services: Participatory Action Research Exploring Social Networking.” Mental Health Review Journal 15 (3): 11–21. doi:10.5042/mhrj.2010.0655.

- Carpiano, R. M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with Me: The “Go-Along” Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health & Place 15 (1): 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

- Castrodale, M. 2018. “Mobilising Dis/Ability Research: A Critical Discussion of Qualitative Go-Along Interviews in Practice.” Qualitative Inquiry 24 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1177/1077800417727765.

- Cook, T. 2009. “The Purpose of Mess in Action Research: Building Rigour Though a Messy Turn.” Educational Action Research 17 (2): 277–291. doi:10.1080/09650790902914241.

- Creek, J. 2010. The Core Concepts of Occupational Therapy: A Dynamic Framework for Practice. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

- Creek, J. 2014. ”Approaches to Practice”. In Creek’s Occupational Therapy and Mental Health, In 5th edn. edited by W. Bryant, J. Fieldhouse, and K. Bannigan, 50–71. Edinburgh:Churchill Livingston Elsevier.

- Curtis, C. 2018. “Giving Voice versus Gate-Keeping: Ethics and Complexities in Qualitative Research Collaborations.” In SAGE Research Methods Cases in Psychology. London: SAGE Publications Ltd https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526429230.

- Dania, A., and L. L. Griffin. 2021. “Using Social Network Theory to Explore a Participatory Action Research Collaboration Through Social Media.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health Routledge. 13 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1836506.

- Daniels, N., P. Gillen, K. Casson, and I. Wilson. 2019. “STEER: Factors to Consider When Designing Online Focus Groups Using Audiovisual Technology in Health Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1–11. doi:10.1177/1609406919885786.

- Diver, S. W., and M. N. Higgins. 2014. “Giving Back Through Collaborative Research: Towards a Practice of Dynamic Reciprocity.” Journal of Research Practice 10 (2): 1–13.

- Driscoll, J. 2007. Practising Clinical Supervision: A Reflective Approach for Healthcare Professionals 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Balliere Tindall Elsevier.

- Duncan, M. E., and J. Creek. 2014. ”Working on the Margins: Occupational Therapy and Social Inclusion”. In Creek’s Occupational Therapy and Mental Health, In 5th edn. edited by W. Bryant, J. Fieldhouse, and K. Bannigan, 457–473. Edinburgh:Churchill Livingston Elsevier.

- Egid, B. R., M. Roura, B. Aktar, J. Amegee Quach, I. Chumo, S. Dias, G. Hegel, et al. 2021. ”‘You Want to Deal with Power While Riding on Power’: Global Perspectives on Power in Participatory Health Research and Co-Production Approaches.” BMJ Global Health 6 (11): 1–15. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006978.

- Evans, J., and P. Jones. 2011. “The Walking Interview: Methodology, Mobility and Place.” Applied Geography 31 (2): 849–858. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

- Fouché, C., and G. Light. 2011. “An Invitation to Dialogue: “The World Cafe” in Social Work Research.” Qualitative Social Work 10 (1): 28–48. doi:10.1177/1473325010376016.

- Freire, P. 2014. Pedagogy of the Oppressed 30th anniv. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Frisby, W., C J. Reid, S. Millar, and L. Hoeber. 2005. “Putting “Participatory” into Participatory Forms of Action Research.” Journal of Sport Management 19 (4): 367–386. doi:10.1123/jsm.19.4.367.

- Garbutt, R., J. Tattersall, Jo Dunn, and R. Boycott-Garnett. 2010. “Accessible Article: Involving People with Learning Disabilities in Research.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 38 (1): 21–34. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3156.2009.00556.x.

- Garcia, C. M., M E. Eisenberg, E A. Frerich, K E. Lechner, and K. Lust. 2012. “Conducting Go-Along Interviews to Understand Context and Promote Health.” Qualitative Health Research 22 (10): 1395–1403. doi:10.1177/1049732312452936.

- Glynos, J., and E. Speed. 2012. “Varieties of Co-Production in Public Services: Time Banks in a UK Health Policy Context.” Critical Policy Studies 6 (4): 402–433. doi:10.1080/19460171.2012.730760.

- Gopichandran, V. 2020. “Community Gatekeepers and the Conundrum of Confidentiality and Coercion.” Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 5 (1): 11–13. doi:10.20529/IJME.2020.009.

- Hand, C., D L. Rudman, C. McGrath, C. Donnelly, and M. Sands. 2019. “Initiating Participatory Action Research with Older Adults: Lessons Learned Through Reflexivity.” Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 38 (4): 512–520. doi:10.1017/S0714980819000072.

- Harries, P., D. Barron, and C. Ballinger. 2020. “Developments in Public Involvement and Co-Production in Research: Embracing Our Values and Those of Our Service Users and Carers.” The British Journal of Occupational Therapy 83 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1177/0308022619844143.

- Hayhurst, L. M. C., and L. del S. C. Centeno. 2019. ““We are Prisoners in Our Own Homes”: Connecting the Environment, Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights to Sport for Development and Peace in Nicaragua.” Sustainability 11 (16): 4485. doi:10.3390/su11164485.

- Hickey, G., Allam, A, Boolaky, U, McManus, T, Staniszewska, S, Tembo, D . 2021. ”Co-Producing and Funding Research in the Context of a Global Health Pandemic.” In COVID-19 and Co-Production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy, and Practice: Volume 1: The Challenges and Necessity of Co-Production, edited by P. Beresford, Bristol: Policy Press 10.

- Hickson, M. 2008. Research Handbook for Health Care Professionals. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Holt, N. L., Tara-Leigh F. McHugh, L N. Tink, B C. Kingsley, A M. Coppola, K C. Neely, and R. McDonald. 2013. “Developing Sport-Based After-School Programmes Using a Participatory Action Research Approach.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 5 (3): 332–355. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2013.809377.

- Kinney, P. 2018. “Walking Interview Ethics.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research Ethics, edited by R. Iphofen and M. Tolich, 174–187. London: SAGE Publications Limited.

- Koch, T., and D. Kralik. 2006. Participatory Action Research in Health Care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Kramer-Roy, D. 2015. “Using Participatory and Creative Methods to Facilitate Emancipatory Research with People Facing Multiple Disadvantage: A Role for Health and Care Professionals.” Disability & Society 30 (8): 1207–1224. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1090955.

- Langhout, R. D., and E. Thomas. 2010. “Imagining Participatory Action Research in Collaboration with Children: An Introduction.” American Journal of Community Psychology 46 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9321-1.

- Langley, J., Wallace, N., Davis, A., Gwilt, I., Knowles, S., Partridge, R., Wheeler, G., Ankeny, U. 2021. ”COVID Co-Design Does Not *HAVE* to Be Digital!: Why “Which Platform Should We Use?” Should Not Be Your First Question.” In COVID-19 and Co-Production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy, and Practice: Volume 2: Co-Production Methods and Working Together at a Distance, edited by O. Williams, Bristol: Policy Press 10 .

- Layton, N. A. 2014. “Sylvia Docker Lecture: The Practice, Research, Policy Nexus in Contemporary Occupational Therapy.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 61 (2): 49–57. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12107.

- Liebenberg, L., A. Jamal, and J. Ikeda. 2020. “Extending Youth Voices in a Participatory Thematic Analysis Approach.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406920934614.

- Macdonald, C. D. 2012. “Understanding Participatory Action Research: A Qualitative Research Methodology Option.” Canadian Journal of Action Research 13 (2): 34–50. doi:10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37.

- Mansfield, L. 2016. “Resourcefulness, Reciprocity and Reflexivity: The Three Rs of Partnership in Sport for Public Health Research.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 8 (4): 713–729. doi:10.1080/19406940.2016.1220409.

- McSweeney, M., Otte, J., Eyul, P., Hayhurst, L.M.C., Parytci, D.T. 2022. Conducing collaborative research across global North-South contexts: benefits, challenges and implications of working with visual and digital participatory research approaches. In Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 10.1080/2159676X.2022.2048059.

- Mikulak, M., S. Ryan, P. Bebbington, S. Bennett, J. Carter, L. Davidson, K. Liddell, A. Vaid, and C. Albury. 2022. “‘’Ethnography?!? I Can’t Even Say It”: Co-Designing Training for Ethnographic Research for People with Learning Disabilities and Carers.” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50 (1): 52–60. doi:10.1111/bld.12424.

- Mitchell, C. 2011. Doing Visual Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Momori, N., and R. Richards. 2017. “Service user and carer involvement: Co-production.” In Occupational therapy evidence in practice for mental health, edited by C. Long, J. Cronin-Davis, and D. Coterill, 17–34. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119378785.

- Nind, M. 2011. “Participatory Data Analysis: A Step Too Far?” Qualitative Research 11 (4): 349–363. doi:10.1177/1468794111404310.

- Nind, M. 2017. “The Practical Wisdom of Inclusive Research.” Qualitative Research 17 (3): 278–288. doi:10.1177/1468794117708123.

- Oliver, M. 1992. “Changing the Social Relations of Research Production?” Disability, Handicap & Society 7 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1080/02674649266780141.

- Oliver, M. 2002. Emancipatory research: A vehicle for social transformation and policy development, 1st Annual Disability Research Seminar, 2002, Dublin. Dublin.

- Pettican, A. 2018. Getting Together to Play Football: A Participatory Action Research Study with the Positive Mental Attitude Sports Academy. Essex: University of Essex.

- Pettican, A. R., and L. Barrett. (2017) Using Boccia as an Assessment and Intervention Tool: An evidence-based guide for occupational therapy practice. London, UK. Available at: https://www.bocciaengland.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=9ecc72fb-802a-4594-83fd-0cc2806f573b.

- Pettican, AR., Bullen, D., Barrett, L, Fletcher, L . (2021) The Therapeutic use of Table Tennis: An Evidence-Based Guide. London, UK. Available at: https://www.tabletennisengland.co.uk/content/uploads/2021/10/SFC_Table_Tennis_Brochure_May21.pdf.

- Pettican, A., E. Speed, W. Bryant, C. Kilbride, and P. Beresford. 2022. “Levelling the Playing Field: Exploring Inequalities and Exclusions with a Community-Based Football League for People with Experience of Mental Distress.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 69 (3): 290–300. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12791.

- Pettican, Anna, E. Speed, C. Kilbride, W. Bryant, and P. Beresford. 2021. “An Occupational Justice Perspective on Playing Football and Living with Mental Distress.” Journal of Occupational Science 28 (1): 159–172. doi:10.1080/14427591.2020.1816208.

- Pickens, N. D., and K. Pizur-Barnekow. 2009. “Co-Occupation: Extending the Dialogue.” Journal of Occupational Science 16 (3): 151–156. doi:10.1080/14427591.2009.9686656.

- Redwood, S., N. K. Gale, and S. Greenfield. 2012. ““You Give Us Rangoli, We Give You Talk”: Using an Art-Based Activity to Elicit Data from a Seldom Heard Group.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 12 (7): 1–13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-7.

- Rich, K. A., and L. Misener. 2020. “Get Active Powassan: Developing Sport and Recreation Programs and Policies Through Participatory Action Research in a Rural Community Context.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (2): 272–288. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1636850.

- Robertson, L., and S. Griffiths. 2012. “Problem Solving in Occupational Therapy.” In Clinical Reasoning in Occupational Therapy, edited by L. Robertson, 1–14. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Smith, R., M. Danford, S C. Darnell, Maria Joaquina Lima. Larrazabal, and M. Abdellatif. 2021a. “‘Like, What Even is a Podcast?’ Approaching Sport-For-Development Youth Participatory Action Research Through Digital Methodologies.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (1): 128–145. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1836515.

- Smith, B., K. Mallick, J. Monforte, and C. Foster. 2021b. “Disability, the Communication of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, and Ableism: A Call for Inclusive Messages.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 55 (20): 1121–1122. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103780.

- Smith, B., O. Williams, L. Bone, and the Moving Social Work Co-production. Collective. 2022. “Co-Production: A Resource to Guide Co-Producing Research in the Sport, Exercise, and Health Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 1–29. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2022.2052946.

- Spaaij, R., N. Schulenkorf, R. Jeanes, and S. Oxford. 2018. “Participatory Research in Sport-For-Development: Complexities, Experiences and (Missed) Opportunities.” Sport Management Review 21 (1): 25–37. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2017.05.003.

- Sport England. 2018. Working in an Active Nation: The Professional Workforce Strategy for England. London: Sport England.

- Teut, M., Bloedt, S., Baur, R., Betsch, F., Elies, M., Fruehwald, M., Fuesgen, I., Kerckhoff, A., Kuger, E., Schimpf, D, Schnabel, K., Walach, H., Warme, B., Warning, A., Wilkens, J., Witt, C.M. 2013. ”Dementia: Treating Patients and Caregivers with Complementary and Alternative Medicine - Results of a Clinical Expert Conference Using the World Cafe Method.” Forschende Komplementarmedizin 20 (4): 276–280.

- van de Ven, K., I. Boardley, and M. Chandler. 2022. “Identifying Best-Practice Amongst Health Professionals Who Work with People Using Image and Performance Enhancing Drugs (IPEDs) Through Participatory Action Research.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health Routledge. 14 (2): 199–215. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2021.1898457.

- Vega-Córdova, V., I. Álvarez‐aguado, C. Jenaro, H. Spencer‐gonzález, and M. Díaz Araya. 2020. “Analyzing Roles, Barriers, and Supports of Co-Researchers in Inclusive Research.” Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 17 (4): 318–331. doi:10.1111/jppi.12354.

- Williams, O., S. Sarre, S C. Papoulias, S. Knowles, G. Robert, P. Beresford, D. Rose, S. Carr, M. Kaur, and V J. Palmer. 2020. “Lost in the Shadows: Reflections on the Dark Side of Co-Production.” Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1): 43. doi:10.1186/s12961-020-00558-0.

- Wimpenny, K. 2013. “Using Participatory Action Research to Support Knowledge Translation in Practice Settings.” International Journal of Practice-Based Learning in Health and Social Care 1 (1): 3–14. doi:10.11120/pblh.2013.00004.

- York, L., A. MacKenzie, and N. Purdy. 2021. “The Challenges and Opportunities of Conducting PhD Participatory Action Research on Sensitive Issues: Young People and Sexting.” Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 20 (2): 73–83. doi:10.1177/20471734211014454.