ABSTRACT

SPACES (Supporting Physical Activity through Co-production in people with Severe Mental Illness) is a study which aims to develop an intervention to increase physical activity created with and for people with severe mental ill health (SMI), their carers and professionals involved in physical activity and/or severe mental ill health. People with SMI are less physically active than the general population and have an increased likelihood of experiencing long-term physical health conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes and obesity. The SPACES team employed a comprehensive process of Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) work embedded within a co-production strategy. Researchers worked together from the point of inception with people with lived experience, two of whom became co-applicants, to design and carry out the intervention development stage of the study. This included PPIE work and an iterative process of focus groups and interviews with various stakeholders and a consensus group made up of multiple stakeholders with lived, caring and professional experience. Here, we describe the co-production model we used, the benefits, challenges, achievements and areas for learning and improvement. We offer co-production principles and practical strategy, which we hope will be used, modified, personalised and built on by others. We also offer the idea that laying out the co-production strategy to be employed prior to a study commencing and then comparing how that strategy was or was not met could be a step towards creating more accountability and academic rigour in co-production.

Physical activity and severe mental ill health

People living with schizophrenia, bipolar and schizoaffective disorder are less physically active than the general population and spend more time sedentary. This is one of the contributors to the mortality gap. The majority of deaths amongst people with SMI are attributable to physical health conditions and modifiable lifestyle behaviours including tobacco use, physical inactivity and unhealthy diets. People living with SMI die 10–20 years earlier than the general population (WHO, Citation2018).

People living with serious mental illness (SMI) experience debilitating symptoms that worsen their physical health and quality of life. Regular physical activity (PA) may bring symptomatic improvements and enhance wellbeing. When undertaken in community-based group settings, PA may yield additional benefits such as reduced isolation. Initiating PA can be difficult for people with SMI, so PA engagement is commonly low. Designing acceptable and effective PA programs requires a better understanding of the lived experiences of PA initiation among people with SMI. (Quirk et al. Citation2020, 1)

Additionally, ‘The effectiveness of intervening to increase PA or reduce Sedentary Behaviour in SMI populations is unknown’ (Ashdown-Franks et al., Citation2018, p.3)

People with SMI experience significant barriers to being (more) physically active. Four stages have been identified on the journey from being physically inactive to starting to be physically active for people with SMI, namely ‘thinking about being active’, ‘planning and preparing for the activity’, ‘getting to the activity’ and ‘beginning the activity’ (Quirk et al. Citation2020)

To date, we do not know specifically what these barriers to physical activity (PA) are in the context of mental health service users in the UK. An Australian study found that enablers or motivators to engagement in community-based PA include person centred/individualised options, connection and sense of belonging and access to information and education (Wheeler et al. Citation2018) and these factors may well be transferrable to the SPACES context in terms of what makes PA easier for people with SMI. A co-production model is an ideal research philosophy to add to the existing knowledge base and to create an intervention to overcome it.

Co-production with the SMI population

People with SMI and the experience of being ‘heard’

People with severe mental ill health represent a marginalised population who experience social exclusion, stigma and limited access in many aspects of life (World Health Organisation (WHO) Citation2022). As people with SMI are less likely to be heard in any aspect of life, the authors postulate that this can translate into being heard in research.

From the perspective of one of the lived experience authors of this paper, this includes understanding that

‘(The SMI population) experiences a unique set of barriers to various aspects of life that the rest of the population doesn’t experience in entirety’.

Historically, the opinions and perspectives of people with SMI have often been thought to come from symptoms and/or a lack of capacity by those with the power to describe them and to write their history. This means that many people with SMI have been ‘spoken for’, ‘done to’ and ‘written about’ and for some members of the SMI population, this may have been their experience in their lifetime.

People living with SMI often have other minority identities (intersectionality) which are also underrepresented in research. For example, schizophrenia is disproportionately more likely to be diagnosed in black men (Schwartz and Blankenship Citation2014) and people with SMI often live in areas of high deprivation and face financial hardship.

It is important then to hear the voices of this group of people to ensure research is relevant, accessible and works to improve health in a way that is connected to real lived experience. From our experience, co-producing with people with SMI well requires active, consistent and sensitive work from a research team who need to be self-aware, reflexive, have an understanding of power dynamics and work to minimise inequalities.

The awareness of one’s own crisis experiences requires reflexivity. Which discrimination experiences have I had? How did I deal with them? How do I relate to my own crises, limits, norms, needs, demands, etc.? How do I bear these experiences within me? Such a continuous back-reference to oneself can help develop a compassionate, equal relationship. Co-production, therefore, starts with oneself. It is about myself and the questions and struggles I had and still have in my own life. If this back-reference is missing, people often start speaking or acting in roles, and then co-production may not be achieved.

Barriers and potential enablers to co-production

Barriers to working within a co-production framework for people living with SMI may be external, internalised or internal. External (the way in which research typically works, it’s timelines and pressured environment for example) as well as the inaccessibility of academic language, levels of literacy and access to technology, internalised (previous experiences of not be listened to or heard for example) and internal (illness experiences and symptoms). From the perspective of a lived experience member of the SPACES team,

barriers also include trust and creating an environment in which people with lived experience feel able to not only attend meetings and groups, but also to speak openly and with confidence that what they are saying will be heard, understood and valued.

People with SMI may need additional support to attend meetings in person and/or with digital access (Spanakis et al. Citation2022) and researchers working together with experts by experience need to make time and space for them to be heard and be open to creative and adaptive ways of working with people and two-way learning. Researchers co-producing in any area also need to be open to different ways of learning and communicating and to valuing input which is expressed and delivered in ways that may not be typical of the academic environment. From the lived experience perspective of a SPACES team member,

‘often we expect people with lived experience to meet us at a research level, but actually meeting somewhere in between benefits both parties’.

People with SMI are likely to go through fluctuating periods of better and worse health and functioning and therefore co-production work needs to be flexible enough to work with this. Experiences of people with SMI, which are described in the language of the medical literature as acute phase and negative symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar mania and depression can lead to a lessening of motivation and agency and make contributing difficult for people (Yang et al. Citation2021). Additionally, people who have experienced compulsory mental health care may have experienced a lack of agency and the after effects of involuntary mental health treatment can make contributing in the present difficult (Pandarakalam Citation2015).

Power, relevance, impact, equality and inclusion (co-production and patient and public involvement)

‘Co-production is a contested term. Partly that is because it means different things to different people and is used differently in different disciplinary contexts (Brandsen and Honingh 2018; Ewert and Evers 2014). Therefore, any attempt to produce or find in the literature a clear-cut, definitive, and unanimously agreed definition of co-production is futile and unnecessary (Bovaird and Loeffler 2013; Williams et al. 2021). We suggest that researchers do not then waste time searching for the “true co-production” but rather appreciate definitional heterogeneity and the contextual/disciplinary factors that explain it’.

There are many and varied descriptions and understandings of co-production. To date, there is little uniformity in the understanding of the term and typology is lacking. In the context of mental health research, co-production (and co-design) is often associated with PPIE (Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement) work, with a common rhetoric that co-production and PPIE share roots in the sense of theoretical background and moral, ethical and practical imperatives for including lived experience voices in research.

Though they may intersect, it is suffice to say that co-production and PPI have different origins, expectations, and norms. Whilst it is theoretically possible for research to be co-produced within a PPI framework, at this stage this is still exceptional and often achieved in spite of, rather than because of, the structures and norms of PPI

Co-production perspectives can include and grow from economic critique (Cahn Citation2004; Ostrom Citation1990) describing and addressing the split between the work done in the market economy and the work done in the non-market economy along power lines including gender, class, and pertinent to health research, the professional/user divide. Therefore, co-production is about power.

Co-production can also be understood as a practical tool, for example Integrated Knowledge Translation (IKT) where non-research professionals are engaged in the research process, usually to improve its relevance, impact and take up at policy level (Smith et al. Citation2022). Co-production is also about relevance and impact.

Alternatively and additionally, co-production can be traced back to Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (Arnstein Citation1969, ) and can be rooted in a drive to improve equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in research, policy and practice. Co-production has the potential to upturn the usual ways of doing research and in this way can be a ‘revolutionary science’ and ‘a means of transforming academia in itself’ (Smith et al. Citation2022, 12–13). Co-production is about equality, inclusion and new ways of doing, being and understanding in research.

Co-production acknowledges that scientific knowledge is used in a social context and aims to bring that social context into the process of knowledge production. We have found that our co-production work on SPACES spans the principles and practices in all three of these historic models. Power, relevance, impact, equality and inclusion.

By means of comparison and reference back to the work of Smith et al. (Citation2022) cited in this section and possible shared aims, both papers focus on co-production in a physical activity context, Smith et al. write more generally about co-production and explore the concepts/issues in co-production in depth whereas the focus here is on describing a specific example (the SPACES study) in depth. Our description and evaluation of the SPACES co-production work share a noting of the lack of typology around co-production developed to date and offer practical solutions. The two papers agree on the role of co-production in increasing research impact and addressing inequalities and the articles have a common aim or purpose of working towards and grappling with a collective understanding and explanation of co-production. Both works highlight the differences between co-production and PPIE (commonly conflated terminology) and seek to create awareness of language use around co-production and hold to account the increasing prominent use of terms which make research seem more inclusive and equitable than it really is (in this paper, we attempt to hold ourselves to account on this).

When working with a loosely defined concept, especially one which has its’ roots in addressing and redressing power imbalance, (we) as researchers, need to define what we mean by co-production as a tool to create self-awareness and to hold ourselves to account when the possibility of redefining and co-opting the term to suit our needs presents itself.

Introducing the SPACES study – coproducing a physical activity intervention in SMI

The SPACES Co-production model – laying the foundations for a co-produced study.

Despite great efforts to understand physical activity behaviours of SMI populations, the transfer of knowledge into actual sustained physical activity participation in mental health care appears to be deficient in many cases

A co-production model including all stakeholders (those with lived experience, their carers and mental health and physical health professionals) trialled in NHS Sites in the UK offers potential for knowledge transfer into practical application.

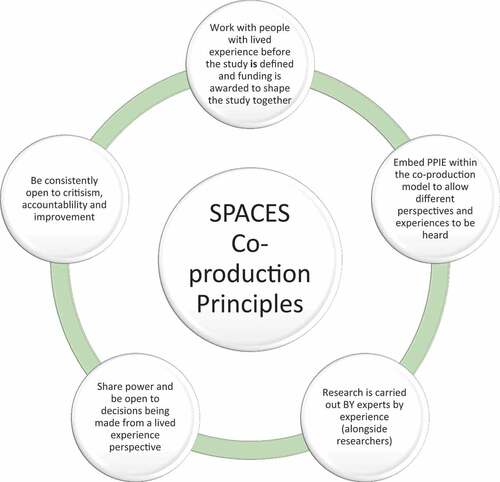

In order to describe and appraise our co-production work and to create the potential for it to be adapted by others in different contexts, we first need to define what we mean by co-production. The principles of co-production from the SPACES study can be seen in .

The early stages of the SPACES study (pre-study and work stream 1) employed a co-production strategy and extensive PPIE work to co-develop a physical activity intervention for people with SMI. Below we describe how our work meets the five points of our co-production method in .

On meeting our own expectations

Each of the five points from . Are explored below in terms of how the principle/expectation has been met on the SPACES study.

Work with people with lived experience before the study is defined and funding is awarded to shape the study together

Specifically, SPACES included lived experience co-applicants who had been involved in the study since the planning stages

‘SPACES has made the best effort to include service user input at every step of the way – even long before the funding application, we have had a voice throughout’

Embed PPIE within the co-production model to allow different perspectives and experiences to be heard

The people we co-produce with will likely be experienced in research and widening participation allows for perspectives of those who cannot be consistently involved and wish to contribute in different ways to be included.

Research is carried out by experts by experience (alongside researchers)

People with lived experience co-facilitated the SPACES work stream 1 qualitative work (focus groups on barriers and facilitators to physical activity) and actively participated in the programme management group (PMG).

Share power and be open to decisions being made from a lived experience perspective

Decisions about the intervention development were made by the study Consensus Group (see .) and a training and information session for the SPACES PPIE group on PPIE and co-production was delivered. This session was an introduction to the research process and research methods and why we involve people with lived experience. It was organised by the lived experience members of the team to create an opportunity to collaborate with greater shared understanding.

Be consistently open to criticism, accountability and improvement

Critical and positive feedback from the SPACES PPIE group and co-applicants have been included in this paper (see limitations and future learnings section) and this paper has been written by a team of seven authors, three of whom have lived experience alongside other researchers. In including critical feedback, we have sought personal accountability and to outline and respond to limitations.

Based on the above principles, here are the steps we took to put co-production into action.

(Power, relevance, impact, equality and inclusion)

Lived experience co-applicants

The SPACES project sought the lived experience viewpoint from the very early stages of the project – prior to the funding application and the research question being finalised. The SPACES team included an expert by experience in early planning meetings, and co-designed and co-facilitated lived experienced workshops prior to the funding application (see pre-study PPIE section). This person subsequently went on to be one of two lived experience co-applicants on the team. The second lived experience co-applicant was a participant in these initial PPIE workshops. Having this input throughout the project, from people who are both currently using services and have personal experience of using physical activity to aid their mental well-being allows the study to stay grounded in the reality that this population experiences on a day-to-day basis.

Pre-study PPIE work looking at the barriers and facilitators to physical activity in people with severe mental ill health

These workshops took place pre-study, to look at the barriers and facilitators to physical activity in people with severe mental ill health. A diverse group of people with SMI took part – including some who had not considered physical activity yet, and others who had completed a local initiative ‘Move More’ (Move More Sheffield Citation2020) and now had physical activity as part of their daily lives. During the course of the workshops, the team were able to create a fish bone diagram (.) highlighting some of the main barriers to physical activity that were experienced by this group. This in turn went on to shape how the research study was designed.

Consensus group with representation from all stakeholders

The SPACES consensus group is made up of people with lived experience of severe mental ill health, people who support them, healthcare professionals who work with people living with SMI and physical activity practitioners such as physiotherapists, trainers and instructors who may have experience of delivering physical activity interventions. The consensus group advised on each stage of the development of the intervention and reviewed each stage to make sure it is workable for people with SMI and the people who work with and support them. One of the key roles of the consensus group was to make decisions about what would be included in the SPACES intervention as we moved through the different phases of the project. Handing over and sharing the power to make decisions is a key part of co-production.

PPIE group involved from the beginning of work stream 1

The SPACES PPIE group is made up of people with direct lived experience, so people who are living with a severe mental illness (SMI) by which we mean Bipolar, Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. The role of the PPIE group is to offer feedback and input into the development of the project including the type of language used in documents sent to research participants and the development of the intervention as well as the potential to contribute to writing about the results of the project. Some of the PPIE group members are also part of the Consensus Group, which fits with co-production principles in that the different stakeholder groups are talking to each other in a network rather than all involvement being kept separate and mediated solely through the research team.

Training/Information session for PPIE group on PPIE and co-production in research and why we involve people with lived experience

An information session was organised where learning about the role of lived experience in research could be shared. Unique resources were created for this purpose by a team comprising lived experience co-applicants and a researcher with lived experience.

Resources shared and discussed included video resources ‘The Ladder of Co-production’ (CitationThink Local Act Personal, TLAP) and ‘The Parable of the Blobs and Squares’ (CitationAberdeenshire ADP Alcohol and Drugs). Aims of this session were to share knowledge and create a common purpose, enable the PPIE group to understand the wider world of research and how PPIE on the SPACES study fits in to the bigger research picture.

PPIE work facilitated by lived experience co-applicants and a researcher with lived experience and including new lived experience voices

Facilitation by people with lived experience can lead to more open and honest input in research and this may well be transferable to lived experience involvement relationships:

Some peer-interviewers found that disclosure enhanced participant-peer rapport from the onset of the interview. Peer-interviewers were empathetic to participants yet were able to maintain professional decorum. Participants were responsive to such disclosure which seemed to put them at ease, viewing the peer-interviewer as someone who could relate to their own experiences. (Devotta et al. Citation2016, 673)

The SPACES team were able to reach out to people with lived experience, carers and professionals who had not necessarily been involved in research before, through information acquired through lived experience involvement and through employing a research assistant onto the study who works as an occupational therapist (OT) and who is involved in many community-based mental health groups.

Benefits and achievements of co-production in physical activity and severe mental ill health

The benefits of the SPACES co-production model include authentic input and a connection between the research and the everyday experience of people living with SMI, rich data gathered through multi-stakeholder focus groups co-designed and co-lead by people with lived experience as well as an uncovering of nuances which may be missed in mainstream research processes and which may lead to the development of a more relevant intervention.

Achievements include the co-production process, experience and learning which forms part of a body of evidence for participatory research, hopefully a well-informed and accessible physical activity programme which can be tested and potentially embedded into the NHS and the creation of communication structures and ways of working within a diverse team.

We also offer a set of co-production principles and practical strategy, which we hope, will be used, modified, personalised and built on by others. We also offer the idea that laying out the co-production strategy to be employed prior to a study commencing and then comparing how that strategy was/was not met (meeting our own expectations) could be a step towards creating more accountability and academic rigour in co-production and co-produced research outputs.

Learnings, future potential and limitations

In terms of learning, it is important, in the authors’ experience, to encourage and emphasise the importance of the lived experience voice and how the research work could not be done in a way which is meaningful to end users (people using mental health services) without it. It is also important to foster confidence in experts by experience in the value of their input and contributions. This requires consistency, keeping promises in terms of frequency of co-production meetings, an openness to power sharing and adjusting to decisions that come from outside of the typical research team. In PPIE work, it can also include feeding back adjustments made to the research work in response to lived experience input.

Feedback from the SPACES PPIE group suggests that additional support to access meetings in person and digitally should be offered as a matter of course and experts by experience should be asked about other access requirements.

In terms of limitations, some of the barriers to co-production are systemic and from the lived experience perspective of a member of the SPACES team;

I’ve struggled a bit with being a co-applicant, mostly because I’m not formally connected to any of the institutions the rest of the research team are part of. This has meant I’ve sometimes felt a bit out of the loop/struggled to keep track of things – this isn’t to say that I haven’t felt supported by the team and everyone has always been very helpful when I’ve needed support with keeping on top of all of the different things, but for me, the fact that ‘the system’ isn’t very well set up to facilitate me easily having access to knowledge/resources/etc. is something I personally find to be a barrier

Other barriers to co-production are around ways that the research team can learn to communicate differently. On the flipside, the quote below, from a lived experience co-author shows how lived experience members of the team can break down barriers and act as a bridge to PPIE work within a co-production strategy.

I also recall chatting to a couple of the PPIE group members last time I met them in person, who were saying that they have struggled with things like knowing when they are needed and feeling like they want to know more about what will be discussed in PPIE sessions beforehand. I think that’s maybe less of a limitation as such, and more of a teething problem/future learning situation – i.e. it highlights the importance of doing things like asking them (PPIE group) for communication preferences (which I’m aware we did do, but still!). On the flip side, it also shows the benefits of having lived-experience co-applicants – it gives group members someone who they can potentially more easily trust to raise issues they are having. So yeah, not necessarily a limitation, but just that it creates a different/less automatic way of doing things that needs to be remembered by staff who are in contact with those people, which I at least think is interesting.

Additional points for future learning from a lived experience team members’ perspective include

The potential for upskilling PPIE members and lived experience co-applicants earlier in the process.

Delivering ‘the opposite training’ – and training the research study team on co-production and how to use it effectively and what barriers/challenges there could be, including internal power dynamics. This ‘opposite training’ is something that was discussed but hasn’t materialised in this study as yet.

The small amount of time we (lived experience co-applicants) had to dedicate to the project meant we were still on the periphery compared to many of the study team working on the project, having a day a week or more for lived experience co-applicants would have allowed this balance to be better and feel a more equal ownership over the project as we still feel somewhat like guests on the team.

In terms of learnings for the future around language usage and meaning, in the writing of this article, the authors have become aware of critique of ‘consensus’ from a co-production perspective. In their article

‘Designed to Clash? Reflecting on the Practical, Personal, and Structural Challenges of Collaborative Research in Psychiatry’ The authors write ‘Collaborative research in the field of psychiatry is designed to bring together researchers with widely diverse backgrounds. Emerging conflicts are important parts of knowledge production but also exceptional opportunities to negotiate research ethics, and potential vehicles for personal growth and transformation’

‘Goals and perspectives may vary extensively to the point that a joint proceeding becomes impossible’.

Our use of the word ‘consensus’, which has also been used by other colleagues working on co-produced studies and in PPIE work (based on anecdotal discussion), has further highlighted the importance of precision in language use when describing co-produced work. Grappling with concepts such as the tension between consensus and co-production will create and imperative for precise language use which will allow us to better document, improve and review our practice into the future.

Concluding thoughts

There is no one definition of co-production and co-production with any given community requires relationship with and knowledge of that community in order to work together most effectively. A blanket definition of co-production could diminish the flexibility and openness to learning which is very much its’ essence and so it becomes imperative for any co-produced study to outline in its outputs a working definition of the term in their specific context and how it has and has not been met.

As our theory and practice in co-production progresses, we create a pathway to learning, improvement and acceptance within the research community of co-produced research as a way of doing research which can be described in a shared language and where we can be held to account by our peers with and without lived experience in our processes and outputs.

Co-production in SMI and physical activity research creates a potential to uncover unseen barriers as well as facilitators and strengths in an underserved community who have been ‘done to’ and ‘spoken for’ for so long. Here, co-production is a way of doing which may allow solutions to be created using the combined strengths of lived experience insights and the methods employed in research which are trusted by policy makers and allow ‘what works’ to be shown in more diverse ways and become funded and widely available to the end user.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ extent their gratitude to the lived experience advisors, who contributed their time and lived expertise to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lauren Walker

Lauren Walker is a Research Associate with expertise is in co-production. Her research career since 2012 has been on studies looking into severe mental ill health in relation to physical health and care planning as well as refugee mental health. All of the major studies Lauren has worked on have been co-produced and she shares learnings from this through academic writing, training and working with PPIE groups as well as learning from those bringing other health related lived experiences to research and teaching. Lauren brings her own lived experience and carer perspective to her work as well as experience from the co-operative movement, welfare rights, advocacy and arts and mental health. She works to highlight and challenge power dynamics and to create a more egalitarian research environment.

Sam Dawson

Sam Dawson is an Occupational Therapist with more than 10 years' experience, the majority of which have been in mental health inpatient rehabilitation settings. Sam currently spends part of his time as a clinical research assistant and has a particular interest in promoting participation in physical activity for people with significant mental health condition. He currently helps run a mental health friendly football project in partnership with Sheffield Flourish and Sheffield United Community Foundation.

Samantha Brady

Samantha Brady is a Research Fellow/Trial Manager based at York Trials Unit. Sam previously managed the SPACES programme of research which aims to co-produce an intervention to support people with severe mental ill health to take part in physical activity. Sam is an experienced mixed methods health researcher, who joined the University of York in 2013. Prior to working at the University, she worked as a health care assistant in a variety of clinical mental health settings including acute, forensic, child and adolescent and older adult’s services.

Emily Hillison

Emily Hillison is a lived experience member of the authorship team and has provided a lived experience perspective to the development of SPACES. She has co-produced and delivered training to SPACES PPIE members, created and developed PPIE and consensus group member role descriptions and has been part of the programme management group for SPACES.

Michelle Horspool

Michelle Horspool is a Mental Health Nurse by background. She completed her PhD in 2008 and has over 10 years of experience working within NHS and academic research environments. Throughout this period she has been involved in the development and management of clinical trials and complex interventional studies across both primary care and mental health. Michelle maintains an active academic CV and is an Honorary Researcher at the University of Sheffield's Mental Health Research Unit.

Gareth Jones

Gareth Jones joined Sheffield Hallam University, Sport and Physical Activity Research Centre, in 2016 after completing his PhD in behavioural health psychology. Gareth currently works on various projects focusing on physical activity promotion with various target populations, including children and young people and people with severe mental ill health. Gareth’s expertise lay within psychological theory, intervention design, behaviour change and whole systems thinking.

Ellie Wildbore

Ellie Wildbore uses her lived experience of mental health in her work to increase the involvement of service users in research, improving access to research opportunities for service users and promoting the importance and benefits of clinical research. This means encouraging more people to take part in research as participants and volunteers in studies and as collaborators on studies. Ellie also teaches on various mental health related courses at universities regionally and works on research projects including SPACES, CARE Covid, Defining Relational Practice and New Roles in Mental Health.

Emily J Peckham

Emily Peckham is a Senior Research Fellow in the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group and holds an honorary appointment as Senior Research Fellow at Tees Ask and Wear Valleys NHS Trust. Emily’s research focuses on reducing the health inequalities people with severe mental illness experience and she has expertise conducting research with this participant group and in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions.

References

- Aberdeenshire ADP Alcohol and Drugs “The Parable of the Blobs and Squares” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eJDO1rcJbBw. Viewed 18/07/2022

- Arnstein, S R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4, July): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Ashdown-Franks, G., J. Williams, D. Vancampfort, J. Firth, F. Schuch, K. Hubbard, T. Craig, et al. 2018. ”Is It Possible for People with Severe Mental Illness to Sit Less and Move More? A Systematic Review of Interventions to Increase Physical Activity or Reduce Sedentary Behaviour.” Schizophrenia Research 202: 3–16. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.058.

- Beeker, T., R K. Glück, J. Ziegenhagen, L. Göppert, P. Jänchen, H. Krispin, J. Schwarz, et al. 2021. ”Designed to Clash? Reflecting on the Practical, Personal, and Structural Challenges of Collaborative Research in Psychiatry.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 701312. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.701312.

- Cahn, ES. 2004. No More Throw-Away People: The Co-Production Imperative. 1st ed. Washington DC: Essential Books.

- Devotta, K., J. Woodhall-Melnik, C. Pedersen, A. Wendaferew, T P. Dowbor, S J T. Guilcher, S. Hamilton-Wright, et al. 2016. ”Enriching Qualitative Research by Engaging Peer Interviewers: A Case Study.” Qualitative Research 16 (6): 661–680. doi:10.1177/1468794115626244.

- Matthews, E., M. Cowman, and S. Denieffe. 2017. “Using Experience-Based Co-Design for the Development of Physical Activity Provision in Rehabilitation and Recovery Mental Health Care.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 24 (7, Sep): 545–552. doi:10.1111/jpm.12401.

- Move More Sheffield. 2020. “A Healthier, Happier and More Connected Sheffield”. Viewed 31/08/2022. https://www.movemoresheffield.com/

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pandarakalam, J P. 2015. ”Formal Psychiatric Treatment: Advantages and Disadvantages.” British Journal of Medical Practitioners December 8 (4) Number

- Quirk, H., E. Hock, D. Harrop, H. Crank, E. Peckham, G. Traviss-Turner, K. Machaczek, et al. 2020. ”Understanding the Experience of Initiating Community-Based Group Physical Activity by People with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review Using a Meta-Ethnographic Approach.” European Psychiatry 63 (1): E95. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.93.

- Rose, D. 2009. “Collaboration.” In Handbook of Service User Involvement in Mental Health Research, edited by J. Wallcraft, B Schrank, and M Amering, 169–181. Oxford: WileyBlackwell.

- Schwartz, RC., and DM. Blankenship. 2014. “Racial Disparities in Psychotic Disorder Diagnosis: A Review of Empirical Literature.” World Journal of Psychiatry 4 (4): 133–140. doi:10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.133. 2014 Dec 22.

- Smith, B., O. Williams, L. Bone, the Moving Social Work Co-production. Collective, and and The Moving Social Work Co-production Collective 2022. ”Co-Production: A Resource to Guide Co-Producing Research in the Sport, Exercise, and Health Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 3: 10.1080/2159676X.2022.2052946

- Spanakis, P., R. Wadman, L. Walker, P. Heron, A. Mathers, J. Baker, G. Johnston, et al. 2022. ”Measuring the Digital Divide Among People with Severe Mental Ill Health Using the Essential Digital Skills Framework.” Perspectives in Public Health doi:10.1177/17579139221106399.

- Think Local Act Personal (TLAP) ‘The Ladder of Co-Production’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEgsJXLo7M8. Viewed 18/02/2022

- Von Peter, S., and G. Schulz. 2018. “I-As-We’ - Powerful Boundaries Within the Field of Mental Health Co-Production.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 27 (4): 1292–1300. doi:10.1111/inm.12469.

- Wheeler, AJ., H. Roennfeldt, M. Slattery, R. Krinks, and V. Stewart. 2018. “Codesigned Recommendations for Increasing Engagement in Structured Physical Activity for People with Serious Mental Health Problems in Australia.” Health & Social Care in the Community 26 (6): 860–870. doi:10.1111/hsc.12597.

- Williams, O., G. Robert, G.P. Martin, E. Hanna, and J. O’Hara. 2020. “Is Co-Production Just Really Good PPI? Making Sense of Patient and Public Involvement and Co-Production Networks.” In Decentring Health and Care Networks. Organizational Behaviour in Healthcare, edited by M. Bevir and J. Waring. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40889-3_10.

- World Health Organisation (WHO), 2018. Management of Physical Health Conditions in Adults with Severe Mental Disorders. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275718/9789241550383-eng.pdf viewed 14/10/2022

- World Health Organisation (WHO), January 2022. Schizophrenia Key Facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia Viewed 31/08/2022

- Yang, X., J. Huang, P. Harrision, M E. Roser, K. Tian, D. Wang, and G. Liu. 2021. “Motivational Differences in Unipolar and Bipolar Depression, Manic Bipolar, Acute and Stable Phase Schizophrenia.” Journal of Affective Disorders 283: 254–261. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.075.