ABSTRACT

As the phenomenon of playing hurt persists in sports, extant literature has explored the risk, pain, and injury custom (RPIC) from diverse angles. However, academic endeavours revealing the agency–structure continuum between individual agents’ willingness to play hurt and the capital structure related to the RPIC remain limited. This study aims to investigate professional athletes’ health-compromising practice and its underlying mechanism through capital games. Drawing on Bourdieu’s theory of practice, we examined two research questions: (a) how does individual athletes’ desire for capital justify playing hurt? and (b) how are their capital games connected to the RPIC? Empirical data were collected through semi-structured and photo-elicitation interviews with eight athletes and six coaches (ex-athletes) from three combat sports. The data were interpreted using reflexive thematic analysis. The findings were categorised into two narratives: (a) rationalisation of playing hurt and (b) reproduction of the RPIC. First, our participants continued playing hurt, expecting certain rewards (cultural, social, economic, and performance capital); this profit-seeking aspiration rationalised self-destructive action as an investment to garner social energy in the field. Second, the more athletes immersed themselves in capital games using health as a token, the more prominent the habitus of playing hurt became in the field. This RPIC reproduction mechanism drove former/present athletes’ choices to converge into an identical career trajectory, uni-taste, and limited subversion strategy, trapping them in a cycle where the victim becomes another perpetrator of playing hurt. These results are expected to provide sport institutions with insights into building safer sporting environments.

Introduction

Playing hurt – exercising with pain and injury – has been a recurring phenomenon in the sport sphere (Nixon Citation1993; Roderick, Waddington, and Parker Citation2000; Schneider et al. Citation2019). As sports inevitably entail risks of pain and injury, players experience direct and indirect physical, emotional, and social harm in contexts where suffering is glorified (Atkinson Citation2019; Nixon Citation1992; Wacquant Citation2004; Young Citation2012; Young, White, and McTeer Citation1994). For instance, 1996 Atlanta Olympic medallist Kerri Strug was lauded for overcoming a severe injury and prioritising her nation’s prestige over her health. Contrastingly, Simone Biles’s choice to opt out of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games to safeguard her mental health (NBC Sports, 28 July Citation2021) generated controversy over whether it was a ‘selfish, childish national embarrassment’ (The Washington Post, 29 July Citation2021). Similarly, in South Korea (this study’s setting), the media has idolised athletes’ willingness to play hurt (Lim and Park Citation2012), as exemplified by this headline: ‘South Koreans salute “superhero” Son Heung-min’s grit by donning Zorro-like mask at Qatar World Cup 2022’ (Asianet Newsable, 24 November Citation2022). While the media glorifies grit, the risk, pain, and injury custom (RPIC) can trigger negative after-effects, including early career termination, identity confusion, declined self-esteem, chronic pain, and permanent disability (Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007; Ristolainen et al. Citation2012; Spencer Citation2012), as observed among numerous Olympians who were injured during their careers (Palmer et al. Citation2021). The elite sports system pushes athletes to extreme thresholds to sustain their careers (e.g. Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021). However, athletes’ persistent efforts to play while being injured paradoxically reduce their possibility of success therein (Roderick Citation1998).

For decades, playing hurt has been studied from various perspectives; the main discourse can be broadly categorised into four aspects. First, abundant research has addressed sociocultural norms (e.g. sacrificing for the team, taking risks, and pushing the envelope), which steer athletes towards health-compromising practices (e.g. Hughes and Coakley Citation1991; Roderick Citation1998, Citation2006; Roderick, Waddington, and Parker Citation2000). As an epicentre of the risk-taking ethic, the ‘sportsnet’ – comprising coaches, trainers, teammates, fans, medical personnel, and other stakeholders – conveys a cultural message that normalises pain and injury (e.g. Malcolm Citation2006; Nixon Citation1992, Citation1993; Roderick Citation1998, Citation2006; Safai Citation2003). Specifically, Liston et al. (Citation2018) revealed that the sport subculture and institutional structure compel rugby players to remain ‘headstrong’ about injuries (e.g. ignoring or denying concussions). Meanwhile, Safai (Citation2003) showed that an institution’s precautionary culture (i.e. a zero-tolerance policy and uncompromising attitudes towards players’ head injuries) could counter risk-pain-injury pressures. In a similar vein, Malcolm and Sheard (Citation2002) argued that the English rugby union’s professionalisation did not lead to athletes’ acceptance of playing with pain and injury; rather, players demonstrated a marked reluctance to play hurt owing to the rugby sportsnet’s multifaceted support.

Second, several scholars have examined violence, hegemonic masculinity, and male identity related to pain and injury tolerance (e.g. Messner Citation1992; Spencer Citation2012; Young Citation2012; Young, White, and McTeer Citation1994). For instance, Messner (Citation1992) asserted that the conjunction of professional athletes’ masculine identity (internal element) and other sporting stakeholders’ pressures (external element) influenced athletes to sacrifice their bodies by playing with pain and injury. Young, White, and McTeer (Citation1994) noted that male athletes who halt training or games because of injury could be stigmatised as less masculine by peers, particularly when the injury is not considered serious. Spencer (Citation2012) found that mixed martial arts fighters’ injuries affect their sporting careers, depriving them of the alpha male position in the hierarchy. Although sports injury has primarily been regarded as a male-domain issue, both men and women are inclined to normalise pain and injury (Charlesworth and Young Citation2004); therefore, this phenomenon could relate more closely to the inherent nature of sports than gender differences (Mayer and Thiel Citation2018).

Third, multiple studies have shown that coaches’ insufficient health and safety support could jeopardise athletes’ careers (e.g. Anderson and Jackson Citation2013; Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2019; Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021; Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007). Authoritative coaching styles and hierarchical relationships legitimise risky environments that require athletes to withstand injuries and return prematurely from rehabilitation (Cavallerio, Wadey, and Wagstaff Citation2016; McMahon et al. Citation2020; Roderick, Waddington, and Parker Citation2000); in such cases, players may feel like ‘a dispensable tool’ for victory rather than a person (Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007, 135). Further, coaches’ unstable employment often places them under tremendous stress to win. This occupational pressure could lead them to urge medical practitioners to compromise their professional standards (i.e. returning injured athletes to training before medical clearance) and push athletes to play with injuries ‘especially when there is a no play-no pay payment structure’ (Anderson and Jackson Citation2013, 247).

Fourth, some researchers have conducted quantitative investigations of athletes’ willingness to play hurt (e.g. Jessiman-Perreault and Godley Citation2016; Mayer and Thiel Citation2018; Schneider et al. Citation2019; Schnell et al. Citation2014). In particular, Mayer and Thiel (Citation2018) examined adult elite athletes’ perceptions based on sickness presenteeism, which explains the reason employees attend work despite feeling sick. According to their survey, approximately half of 723 handball and track-and-field athletes had strong rest-aversion and pain-trivialising tendencies, whereas the other half took rest conditionally. Similarly, other survey-based studies have confirmed that various factors (e.g. sport type, social pressure, coaching style, and psychological characteristics) are associated with athletes’ willingness to play hurt (Jessiman-Perreault and Godley Citation2016; Schneider et al. Citation2019; Schnell et al. Citation2014).

Although previous studies have built sound knowledge of sporting pain and injury from diverse viewpoints, academic endeavours unveiling the agency-structure continuum between individual athletes’ willingness to play hurt and the capital structure related to the RPIC remain inadequate. Therefore, this study aims to explore professional athletes’ health-compromising practice and its underlying mechanism through capital games. Adopting Bourdieu’s theory of practice (i.e. the dialectical interplay between individual agents and social structure), we probed two research questions: (a) how does individual athletes’ desire for capital justify playing hurt? and (b) how are their capital games connected to the RPIC in combat sports?

Theoretical framework

Society is a battlefield wherein individuals struggle to gain more capital and attain higher positions using either succession (complying with the existing interest structure) or subversion (reconstructing the established hierarchy) strategies (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1993; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). The strategy’s appropriateness depends on its correspondence with a social practice – the nexus of capital, habitus, and field (Bourdieu Citation1984).

Capital is accumulated labour that possesses social energy (Bourdieu Citation1986). As the amount of capital determines the options available to individuals and their capacity to exercise power over others, it is imperative to convert one capital type into another to amass social energy (Bourdieu Citation1986). If the notion of capital is confined to financial currency, the complex and dynamic power struggles in contemporary society will remain enigmatic. In this context, Bourdieu (Citation1986) classified capital into economic, social, and cultural forms. Following this categorisation, other scholars subdivided capital into more specific formsFootnote1 to comprehend the rapidly changing society.

Habitus refers to an embodied schema that unconsciously influences one’s thoughts and actions towards a particular direction by imparting prizes (symbolic power) and penalties (symbolic violence) (Bourdieu Citation1984; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). However, habitus does not predetermine individuals’ decisions, instead, it allows conditional freedom. For example, the habitus prevalent in a university society provides significant naturalness and comfort to upper-class students but guarantees neither their continuation of college education nor working-class students’ failure to acquire an elite habitus, such as new etiquettes and academic interests (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1977). Hence, habitus is rigid but fluid, as working-class students can shift from their habitus to that of a higher class through demanding adaptation processes (e.g. Lehmann Citation2014).

Field is a multidimensional social place with its unique logic (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1993; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). As capital’s value can change depending on the field’s logic, those who want to earn profits through games must consider the dominant logic as a rule formed alongside the field’s history (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). For instance, the prevailing logic in our research setting – Confucianism and totalitarianism, which stress moral norms, self-discipline, and strict hierarchy – has developed over the course of Korean history (Ogura Citation2021). Korean governments exploited elite sports to legitimise their regimes through success in international sport events. To this end, their sport-related policies centred around ensuring athletes’ dedication to training in socially isolated institutions, such as sport-specialised boarding schools, universities, and national training centres (MCST Citation2019b). These training institutions operated on the principles of hierarchical relationships, coercive overtraining, and life control (MCST Citation2019a, Citation2019b; NHRCK Citation2019); the field’s historical trajectory intensified the two logics, influencing players’ way of capital conversion and their habitus formation.

Using the capital–habitus–field nexus, Wacquant (Citation2004) illustrated the process of assimilation into the boxing world, where individuals continually hone their bodies into weapons while experiencing indigenous meanings of ‘fear’, ‘violence’, ‘pain’, ‘injury’, and ‘sacrifice’ rooted in the gym. Wacquant also revealed that becoming a boxer is closely linked to the embodiment of a group’s identity, history, norm, and culture. This dialectical nexus is useful in unpacking the hidden mechanism of social practices in sport coaching (Jones et al. Citation2011). Nonetheless, previous studies that used Bourdieu’s lens tended to overlook dynamic interplays among the three concepts (Maton Citation2012). To address this limitation, we analyse professional athletes’ capital game around playing hurt and the RPIC from Bourdieu’s (Citation1984) perspective: [(capital)(habitus)]+field=practice.

Methodology

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) allows researchers to select the most suitable philosophical premise for the research topics, questions, and data (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, Citation2022). With this paradigmatic flexibility, we used RTA based on social constructionism (Patton Citation2015). Instead of pursuing a single objective truth, this approach ontologically assumes individuals as agents who construct reality with others in their group’s value structure and epistemologically views their language as the social component creating, distorting, and structuring reality (Patton Citation2015). This onto-epistemological standpoint provides this study with a solid philosophical foundation for exploring how individual members’ reality of playing hurt is (re)constructed via combat sport groups’ capital structure related to the RPIC.

Participants

After obtaining ethical approval from a government research ethics institution, we initiated participant recruitment. To identify how health-compromising practices are (re)produced in the athlete–coach pathway (Blackett, Evans, and Piggott Citation2017; Rynne Citation2014), we invited current athletes and coaches (former athletes) based on three criteria: those who have (a) maintained athletic careers spanning more than 10 years; (b) undergone injuries requiring surgery or rehabilitation; and (c) experienced group life at training institutions. Among the candidates, we selected participants from different age groups (Patton Citation2015) to reduce generational bias regarding pain and injury. A total of 14 participants (eight athletes and six coaches) from three combat sports were recruited, and the personal information (e.g. name, age, and sport) was anonymised to protect their identities (see ).

Table 1. Participant information.

Data collection

Grounded in social constructionism, we used two interview techniques to explore combat sport members’ reality associated with playing hurt through their language, which functions as a primary social component (Patton Citation2015). First, semi-structured interviews were conducted twice (50–60 mins each), using a guideline for questions (Patton Citation2015) on (a) injury experiences, including symptoms, degree of pain, diagnosis, rehabilitation, retirement, after-effects, others’ reactions, and coping strategies; and (b) the types of capital athletes hoped to accrue by playing hurt. Second, a photo-elicitation interview was conducted (30–50 min). Specifically, after two semi-structured interviews, we asked participants to prepare photos representing their experiences of playing with pain/injury and share the photos’ personal/communal meanings. This was an attempt to (a) evoke participants’ response (e.g. memory or feeling) more vividly (Phoenix Citation2010); (b) enable researchers to understand participants’ perspectives (Cope, Harvey, and Kirk Citation2015); and (c) give readers access to multiple dimensions (e.g. physical, emotional, and cultural) of phenomena by integrating verbal and visual information (Atkinson Citation2010). All interviews were transcribed verbatim, translated by the first author, and stored in a password-protected computer.

Data analysis

For data analysis, we employed the six phases of RTA (Braun and Clarke Citation2022) as a compass to navigate our analytic process rather than a ‘baking recipe that must be followed precisely’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 589).

In the first phase (familiarising yourselves with the dataset), we critically read and re-read the data, considering our participants’ social, political, cultural, economic, and environmental contexts (Patton Citation2015). The first author noted insights related to the research questions and Bourdieu’s ideas while transcribing the recorded data. The second author, a former international-level professional male wrestler, scrutinised participants’ comments from an insider’s viewpoint to discern their implicit communal meaning. Subsequently, the authors discussed each other’s tentative analyses, which guided the follow-up interviews and coding process. In the second phase (coding), recurring words and those related to the research questions were initially codified as the gerund form (e.g. protecting against a wage cut). Such codes were then organised for iterative theme development (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). In the third phase (generating initial themes), we inductively grouped codes into potential themes based on the patterns’ similarities using NVivo-12. The candidate themes were labelled with Bourdieu’s ideas (e.g. economic capital).

In the fourth phase (developing and reviewing themes), we split, combined, and discarded the initial themes based on their relationship with the research questions and theoretical concepts to develop them into stories (Braun and Clarke Citation2022). Next, we checked the inter-connections among potential themes, codes, and the entire dataset by moving back and forth between the inductive data-driven direction (dataset–initial codes–potential themes–concepts) and deductive theory-driven direction (concepts–potential themes–initial codes–dataset). Thereby, we could review whether our themes adequately represented the overall phenomena and aligned with the theoretical framework (e.g. converting playing hurt into financial compensation = economic capital). In the fifth phase (refining, defining, and naming themes), we narrowed down the analytic focus of the themes to key concepts (capital, field, and habitus) and named each story with umbrella-subtitles portraying the central phenomena. In the sixth phase (writing up), we discussed the final themes in line with previous literature via two analytic narratives: (a) rationalisation of playing hurt and (b) reproduction of the RPIC.

Rationalisation of playing hurt

Similar to the law of energy conservation, profiting in one field often involves paying the price in another (Bourdieu Citation1986). For elite athletes, the body is a necessary resource that must be managed to ensure success, but it is not always prioritised (Barker-Ruchti and Barker Citation2017). Our participants also sought to accumulate (a) cultural, (b) social, (c) economic, and (d) performance capital by utilising health as a token.

Cultural capital: acceptance to cultivate group taste

Cultural capitalFootnote2, such as a group’s embodied taste or culture, is a resource for social power (Bourdieu Citation1986). Our participants perceived a sense of diligence and masculinity as etiquette (Bourdieu Citation1984) necessary to be a ‘good player’ in the field and deemed playing hurt as a vehicle for cultivating the group taste espoused by the Confucian training culture.

A head coach repeated the motto () to all the members, but it didn’t move me in my first year at the national training centre. However, as time passed, I became known for not going to the medical room. Looking back at my experience, athletes do this because of coaches. 000 (another current national team player) never stopped training despite a serious injury. I told him, ‘You should rest’, but he continued training [because] he didn’t want the coach to think he wasn’t diligent. (Athlete 5)

I’m certain most teams have this kind of maxim () on the wall [of the gym] because coaches want to uphold this spirit. (Athlete 2)

The Confucian-style phrases highlight extreme self-discipline (Ogura Citation2021), which coaxed our participants to believe that the number/colour of medals reflects a person’s ‘diligence’ (Athletes 3 and 5; Coaches 1, 2, and 3) and attribute the incapability of tolerating agony to a deficiency of diligence. Athlete 8 mentioned, ‘When I feel like I’m on the verge of dying, I take a break, but Olympic medallists with more severe injuries than mine would keep exercising. I thought I needed to be like them’; Coach 2 added, ‘000 (a gold medallist player) has always been consistent; he didn’t rest and tolerated most injuries. That’s the reason he achieved such outstanding records’. These reactions can be interpreted as the group’s misrecognition (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), wherein playing hurt is equated with diligence. This misrecognition nudged participants to embrace the artificially formed taste (i.e. those who overcome pain and injury are ‘good players’) as natural (Bourdieu Citation1984) and enabled the reputation for diligence to be converted into financial benefits between coaches and athletes: ‘My coach said, “Technically, your salary should be cut, but you’re trying very hard; so, let’s freeze this time”’ (Athlete 6); and ‘I’ve helped diligent players get better deals when negotiating their contracts [with pro-teams] because I want to reward their efforts in enduring pain and training hard with great perseverance, though I don’t gain anything from this’ (Coach 3). In this cultural context, coaches can pressure injured athletes to play by redefining the economic value of playing hurt in the name of diligence, particularly when they have the power to control athletes’ salaries (e.g. Anderson and Jackson Citation2013).

The combat sport group’s tastes for machismo also influenced athletes’ willingness to play hurt. Our participants perceived the inability to endure injuries as a sign of ‘weakness’ (Athlete 1) and an ‘unmanly disposition’ (Athlete 3 and Coach 4). Players who internalised the trivialisation of risk, pain, and injury as a display of masculinity were prone to inflict symbolic violence (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1993; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) by mocking and ostracising those unwilling to conform to this vision of manliness (Young Citation2012). This skewed gender stereotype induced participants to wear social masks because emasculation from an injury could affect their careers. For instance, Coach 6, who transitioned from a professional athlete to head coach in 2019, attributed his success to maintaining the image of a ‘strong man’:

The biggest motivation for putting up with injuries was to imprint myself as a strong man in others’ eyes. I believe it helped me secure this job. You know, there aren’t many job positions in the elite section after retiring; that’s why I endured my injuries. Koreans like someone who perseveres well.

Corresponding to Atkinson’s (Citation2019) point that risk-taking could be rewarding, our analysis implies that the combat group’s taste for diligence and machismo cultivated by playing hurt contains symbolic power (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation2004; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), which can be wielded to retain or enhance social position in the hierarchy of ‘sportsnets’ (Nixon Citation1992).

Social capital: avoidance of stigmatisation as a malingerer in sportsnets

While social capital creates values through membership solidarity (Bourdieu Citation1986), its closed and exclusive attributes function as public evils by stigmatising those who breach its norms (Portes Citation1998). Likewise, the combat sportsnet preserves the norm of playing hurt by labelling requests for rest as ‘selfishness’ (Athletes 3 and 5) or ‘cunningness’ (Coaches 2 and 3). Specifically, when athletes’ pain and injury are invisible, it is difficult to judge their authenticity; thus, demands for rest are often deemed detrimental to the group’s solidarity. With the unfounded suspicion that a player might feign pain or injury to evade arduous training and burdensome role expectations (Roderick Citation2006; Roderick, Waddington, and Parker Citation2000), the combat sportsnet’s conspiratorial alliance (Nixon Citation1992; Citation1993) tends to allow rest only for observable (external) injuries or illnesses. Athlete 6 explained, ‘My internal pain was serious but hardly acknowledged here’. This echoes Young, White, and McTeer’s (Citation1994) analysis that admitting pain and injury, except in traumatically serious cases, is perceived as unpreparedness to sacrifice one’s body for the team. As subjective pain is indicative of physical damage that may have severe consequences, timely rest and open communication (where one can freely discuss safety issues) are crucial for long-term health and well-being (Chen, Buggy, and Kelly Citation2019). Nevertheless, some participants condemned taking breaks to cure subjective pain, regarding it as an ‘attitude problem’ (Athletes 1, 3, 4, 5, and 8; Coaches 2 and 3).

Even more problematic is that the distorted interpretation of one’s attitude towards suffering translates to life beyond sports. Athlete 3 commented, ‘I believe such idlers’ habits show their daily life attitude because I’ve never seen them living diligently after retirement’. Similarly, other participants were reluctant to build personal relationships with malingerers due to their ‘dishonest’ (Athlete 5) and ‘irresponsible’ image (Athlete 8; Coaches 2 and 3). This communal antipathy towards malingerers propelled individuals such as Athlete 1 to play hurt: ‘I did my best and worked hard, unlike the loafers’. This response can be construed as self-exclusion (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1977; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Although there is no official coercion to endure pain and injury, individuals’ will to differentiate themselves from ‘loafers’ (Athletes 1 and 4; Coach 3), ‘idlers’ (Athlete 3), and ‘shepherd boys’ (i.e. habitual liars) (Coach 2) discouraged them from resting. Such collective antagonism implies that professional athletes, who are potential candidates for advanced coaching positions, are seldom free from the risk of being stigmatised as malingerers; this is because certain sporting stakeholders can directly influence athletes’ future careers (e.g. Blackett, Evans, and Piggott Citation2017), and their employment usually progresses through informal sportsnet channels (e.g. Bradbury, van Sterkenburg, and Mignon Citation2018). Coach 3’s account depicts how stakeholders’ rigid preferences adversely affect athletes’ future economic activities.

[As a professor directing a university team] whenever I hire a coach, I pick someone diligent, even if his performance is less impressive than that of others. I’m pretty sure everyone in this field uses this standard.

Economic capital: negotiation for securing financial stability

Economic capital is an institutionalised currency (Bourdieu Citation1986). In elite sports, an injury can threaten athletes’ economic value (Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021; Spencer Citation2012) and coaches’ occupational safety. To secure financial stability, both coach and athlete participants utilised negotiating strategies while concealing their monetary aspirations. Athlete 5 illustrated his coach’s discriminatory behaviour in granting permission for breaks:

We’re all athletes, but my coaches treat me specially because I’m an ace player, so, unlike the other players, I can easily take breaks. In my experience, most coaches don’t readily allow young or underperforming athletes to rest, saying, ‘You have to bear [pain] a little more to be better’.

The coach’s remark, ‘bear a little more to be better’, can be interpreted as a euphemism (Bourdieu Citation1991, Citation1998), that is, an alternative expression dualising the objective truth (i.e. concealing exploitative relations). Superficially, it seems to benefit ‘young or underperforming’ athletes. However, in Bourdieu’s eyes, the coaches’ cajoling – which ostensibly attempts to improve the athletes’ performance (dualised truth) – may stem from their own desire for profit (objective truth). Coaches are also vulnerable to career instability (Anderson and Jackson Citation2013); this could motivate them to employ euphemisms to push athletes to withstand pain/injury or return early from rehabilitation, even if this lack of health and safety support could jeopardise (young and underperforming) athletes’ careers (e.g. Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2019; Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021; Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007). By using euphemisms as political lies (Purdy Citation2018), coaches who hope to acquire more capital through their players’ triumphs (Purdy, Jones, and Cassidy Citation2009) can achieve personal goals without damaging their reputations.

Likewise, athlete participants concealed pain and postponed medical treatments during the contract renewal period, perceiving injury as a factor undermining competitiveness in the market (Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021). This financial anxiety transformed severe injury into rational pain that ought to be withstood and hidden: ‘There will be a contract renewal this year […] I don’t think it would be too late to get surgery until I really can’t move’ (Athlete 1); and ‘When I negotiated my contract, I didn’t tell them about my shoulder surgery [experiences]’ (Athlete 3). Despite knowing that masking injuries and delaying medical treatments were short-sighted choices for their health, they continued to do so to extend their professional lives. Contrastingly, some participants deliberately highlighted injuries to receive compensation for their sacrifice for the team (Hughes and Coakley Citation1991) during salary negotiations:

I appealed to my company [a sport team operated by an enterprise] about my painstaking work; I won almost every international game and promoted our company by enduring serious injuries that will persist for the rest of my life. (Athlete 5)

The athletes’ ambivalent attitudes (either intentionally concealing pain or emphasising injuries) indicate that they view injury as an element of the capital game – such as a threat to finances or a means of a pay raise (loss or gain in economic capital) – rather than a health problem itself. These injury-related negotiations could be facilitated by the lack of health and injury-related clauses in participants’ formal contracts; some of them never questioned this issue: ‘Now that I’m talking with you, it’s weird that there is no clause about injury in my contract’ (Athlete 4); and ‘Could you send me relevant information? I’ll suggest this to my company [team]’ (Athlete 5). These reactions resonate with previous findings that sporting workplaces’ occupational safety and health systems are inadequate (Chen, Buggy, and Kelly Citation2019), which permits organisation-centred contract clauses (e.g. Kohe and Purdy Citation2016).

Performance capital: ignoring medical advice

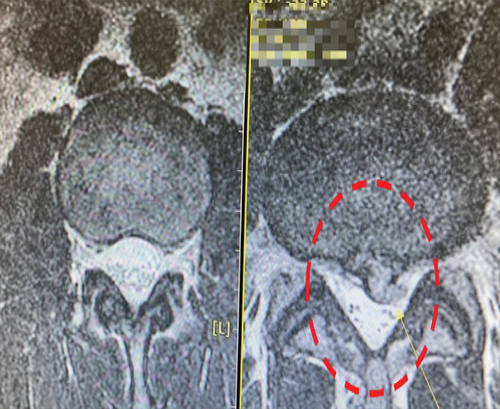

Performance capital is a constellation of embodied technical skills and competencies required to excel in a field (Miller Citation2017). Our participants invested tremendous efforts in refining their performances, as the shortage of this capital can cause unwanted exits from the field, which implies a ‘symbolic death’ for athletes (Atkinson Citation2019). Believing that body techniques deteriorate during injury-related time off (e.g. Spencer Citation2012), they self-diagnosed and ignored medical advice: ‘If I follow the doctor’s advice and get surgery, I’ll have to rest for about six months. It’s unimaginable because I’ve dedicated years to reach this [performance] level. I won’t get any surgery that will ruin my kinaesthetic sense’ (Athlete 7). Athlete 1 also judged his self-diagnosis to be more appropriate than that of a medical professional (see ):

Seeing this image (), the doctor said, ‘If you continue exercising without surgery, the lower half of your body could be paralysed’. But you see, if I had listened to what the doctor said, I would’ve regretted it a lot because, after that, I was able to continue my career without iron pieces in my spine.

Furthermore, participants distrusted over-treatment (‘It’s more profitable for doctors to exaggerate my injury’, Athlete 3) and felt anxious about being replaced (‘My rivals could surpass me during my break’, Athlete 6). For these reasons, they pursued symbolic safety (Kidder Citation2013) – a ritualistic feeling of being protected through temporary treatments, such as ‘pain relief patches/sprays’, ‘anti-inflammatory drugs’, and ‘ice packs’ – instead of following medical professionals’ suggestions and warnings.

As prescribing rest and treatment that prevent athletes from continuous sporting engagements is the most prevalent clinical option for sports-related illness, medical professionals often encounter relational difficulties and a lack of power in the sportsnet (AlHashmi and Matthews Citation2021; Anderson and Jackson Citation2013; Malcolm Citation2006). For instance, our participants frequently partook in medical-practice shopping (Pike Citation2005) to find treatments that fit their sporting goals and ignored medical advice that did not align with their preference by admitting their injuries only in extreme conditions, such as ‘ligament rupture’ (Athlete 2; Coaches 2 and 3), ‘fracture’ (Athlete 3), ‘inability to move’ (Athlete 1), and ‘eyesight loss’ (Athlete 5). These responses denote that athletes value their (insider) judgement more than medical personnel’s (outsider) comments (AlHashmi and Matthews Citation2021); even those with considerable understanding of injuries tend to conceal, ignore, and underreport their symptoms (e.g. Conway et al. Citation2020). This headstrong attitude reinforces the arguments that even top-level athletes struggle to self-determine the fine line between strenuous training and physical exploitation (e.g. Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2019; Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, and Lindgren Citation2021) and implies that the desire for performance capital can be a sufficient incentive for athletes to play hurt.

In summary, for our participants, health was both a vital resource to be preserved for survival and an asset to be consumed for social energy (Bourdieu Citation1986). These health-compromising games were implemented based on the group’s implicit belief that playing hurt would yield rewards. Hence, individual agents hyper-corrected (willingly tailored) their actions in accordance with the dominant norms (the RPIC) to secure profit (Bourdieu Citation1984). This desire for capital rationalised the self-destructive behaviour as an investment (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), leading to the reproduction of the RPIC in combat sports.

Reproduction of the RPIC

Within the game, those who crave a higher status or more assets should embrace the field’s logic as a rule that determines the value of different types of capital and their conversion rates (Bourdieu Citation1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Accepting the field’s logic and existing capital structure, our participants (former and current athletes) immersed themselves in the health-compromising game; this tightened the nexus between capital and field, sustaining the habitus of playing hurt.

Capital conversion: identical career trajectory

As professional athletes, our participants concentrated on activating capital rather than possessing it during the game. They feared their amassed capital’s inactivation (uselessness) after retirement and sought career transitions within sports fields (e.g. Schmid et al. Citation2023) by willingly playing hurt even if the group’s RPIC favouritism was dubious. However, capital games’ outcomes cannot be guaranteed owing to ‘the incommensurability of different capitals’ (Bourdieu Citation1986, 25); therefore, converting health – a limited resource (Barker-Ruchti and Barker Citation2017) – into other forms also entails high uncertainty (Bourdieu Citation1986; Portes Citation1998). For example, Athlete 3, who persistently carried out health-compromising practices to the extent of causing irremediable shoulder damage, neither secured a professional athletic career nor transitioned into an advanced coaching position. He eventually left the sport and moved to a different field, where he could not use his capital at its original value:

My athletic life ended two years ago because of my chronic shoulder injury. At the time, I thought it was right to bear the suffering, as the coaches said. But now I face the sad fact that all my efforts didn’t work. So, I’m currently working at my father’s restaurant.

Notwithstanding Athlete 3’s failure, all other participants successfully operated their capital games. Utilising their accrued capital, they sustained their athletic life and transitioned to leadership coaching positions (see ). This high rate of success can be analysed in three ways. First, institutional arrangements (i.e. fast-track) provide professional athletes with special advantages for smooth career transitions (Rynne Citation2014), such as exemption from formal tests and education required for the national coaching licence (Ryou Citation2021). Second, the capital accumulated (by playing hurt) during one’s athletic career positively influences authoritative stakeholders’ (e.g. senior directors) preference for male candidates who share their taste and can reproduce it (Blackett, Evans, and Piggott Citation2017) under the widespread assumption that athletic experience is a prerequisite for successful coaching (Turner Citation2008). Third, professional athletes have limited options to participate in pre-retirement education during their careers because elite sport environments demand large amounts of time and energy commitment (Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007; Schmid et al. Citation2023). These conditions not only made our participants especially suitable for directorial coaching positions, but also rendered them insensitive to other occupational sectors. Therefore, nearly all participants chose to stay in sports (i.e. their ‘home’) even after their athletic career ended (e.g. Chroni, Pettersen, and Dieffenbach Citation2020; Schmid et al. Citation2023). However, these preferential treatments also intensify the lack of homogeneity with other fields (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) by strongly restricting minority/outsiders’ entry (e.g. Bradbury, van Sterkenburg, and Mignon Citation2018) and majority/insiders’ exit (e.g. Kim, Dawson, and Cassidy Citation2020). This restriction, stemming from the incongruencies with fields outside sports, drives individuals to pursue an identical career path, reproducing a uni-taste between coaches (former athletes) and athletes (future coaches).

Localised field logic: Ex-/present athletes’ uni-taste

As per the game’s rules (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), our participants adhered to the field’s (Confucian and totalitarian) logics to judge what is desirable (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1993). The two kinds of logic established the moral standard of ‘no pain, no gain’ (Athlete 3; Coaches 2, 3, and 5) and ‘military rules’ (Athletes 1 and 5); these covertly deliver the cultural message (Nixon Citation1993) that playing hurt is right and rewarding by defining the dominant group’s taste as excellent and that of the heretic group as repulsive (Bourdieu Citation1984):

Coach 4: It’s disgusting to see players fuss over trivial injuries these days.

Athlete 4: My coach repeatedly says, ‘In my old days, I overcame all the pain, unlike you guys!’

Athlete 5: Senior athletes said, ‘How can you have a successful social life if you act so selfish?’

Experiencing such distinctions (Bourdieu Citation1984) throughout the training institutions (e.g. boarding school sports team→sport university→military athletic corps→professional club team or national training centres), our participants’ needs and interests converged to a uni-taste, and they became more preferential towards those who shared their taste (e.g. Blackett, Evans, and Piggott Citation2017). Since coaches act as gatekeepers of various resources and higher social positions in sportsnets (Jones et al. Citation2011; Nixon Citation1992; Purdy Citation2018), athletes may offset the cost of self-destructive behaviours with the reward of satisfying the coaches’ (ex-athletes) taste for playing hurt. For example, the supply-demand relationship between the group’s uni-taste and employment was witnessed in the previously cited remarks of Coach 6 (as an ex-athlete) in the subsection ‘Cultural capital’ and Coach 3 (as a current head director) in the subsection ‘Social capital’.

Moreover, the field’s localised (Confucian and totalitarian) logic induced our participants to seek their sporting goals with high-level perseverance and dedication in total institutions. This single-mindedness usually leads to athletic excellence but simultaneously constrains one’s development and possibilities for other careers (e.g. Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007; Schmid et al. Citation2023). Particularly, when athletes possess sport-specialised capital and uni-taste to a large degree without alternatives, they are more likely to experience hysteresis (i.e. the incapability to cope with unfamiliar logic in other social fields) (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), as in Athlete 3’s case: ‘After retirement, there has been really little I can do [apart from sport]. So, I’m considering coaching kids in a private gym while helping my father [in his restaurant] for now’. This hysteresis causes athletes to consider themselves ‘idiot(s)’ in the wider society (Kim, Dawson, and Cassidy Citation2020, 93) while confronting non-sporting people’s stereotypes deeming athletes ‘ignorant’ or ‘uneducated’ (Nam, Love, and Rider Citation2022, 287). These internal and external barriers make it harder for athletes to acclimatise to fields outside sport. Concurrently, individual players’ intention to (re)activate the value of capital earned during their athletic careers nudges them to remain in or return to their ‘home’ (i.e. the sport fields) (Chroni, Pettersen, and Dieffenbach Citation2020), where ‘almost all Korean high-performance coaches are former elite athletes who share collective experiences of being trained under an authoritative coaching regime’ (Kim, Dawson, and Cassidy Citation2020, 85).

Habitus of playing hurt: limited subversion strategy

The habitus of playing hurt, yielded by the dialectic nexus between the capital and field, gravitates ex-/present athletes’ perceptions and actions towards the RPIC in most cases. However, this does not imply that the habitus predetermines their reactions (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) because its continuity hinges on the proportion of succession and subversion in the field (Bourdieu Citation1993). Our participants usually employed succession strategies to maintain the field’s established interest structure by hyper-correcting (Bourdieu Citation1984) their behaviours to the RPIC for game profits. They also used subversion strategies when playing hurt could impair their health to an unbearable extent. As an example of subversion, some athletes avoided joining the national training centre, which is neither democratic nor safe (e.g. MCST Citation2019a, Citation2019b; NHRCK Citation2019): ‘The national centre [staff] pushes us to go through insanely gruelling training four times a day, and they would just throw us away if we were hurt. Does that make sense?’ (Athlete 6). For this reason, participants deemed it more profitable not to enter the ‘unsystematically gruelling’ (Athletes 5 and 6; Coach 2), ‘seriously hierarchical’ (Athlete 4), and ‘repetitive injury-causing’ (Athlete 2 and Coach 3) national training centre, even if it meant losing the chance to be national representatives. Athlete 4 stated, ‘Players today think [that] receiving a steady income in home pro-teams is much better than being a national team member’. To circumvent the national coaching staff’s potential retaliations to the athletes’ subversion (Bourdieu Citation1993) of refusing to enter the national training camp (e.g. Purdy, Jones, and Cassidy Citation2009) or self-protecting against high-load training programmes, some ‘smart’ athletes pleaded with home-team coaches to make plausible excuses:

Nowadays, smart athletes avoid unnecessary relational troubles with national team coaches in advance. They ask their pro-team coaches, who have a close bond with the national coaching staff, to exclude their names from the [member] list. This generation puts their interests before the nation’s prestige. (Coach 3)

The quote corresponds with Bourdieu’s (Citation1993) perspective that the subversion strategy is more likely to be limited to certain boundaries because extreme subversion entails a risk of being expelled from the field. Specifically, when discrepancies between the habitus and the agent’s practice worsen, individuals can challenge the field’s structure (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) with ‘cleft habitus’, which creates relational tension and conflict with the existing habitus (Bourdieu Citation2004). However, the smart athletes’ strategy was somewhat limited because (a) it was employed only by athletes who already had sufficient social capital (one’s available network) in the field, and (b) it was closer to a compromise since they implicitly agreed that the capital in the (health-compromising) game is still worth struggling for (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). As the smart athletes aimed to keep their own interests while maintaining the existing structure of the game, and their subversion was tacitly tolerated by coaching groups (professional and national teams), the above strategy seldom de/restructured the game. Rather, it contributed to a complicity (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) that strengthened the extant capital–habitus–field nexus, thereby reproducing the RPIC practice ().

Conclusion

This study adopted Bourdieu’s theory of practice to explore male athletes’ capital game as the agency–structure continuum between individual agents’ willingness to play hurt and the capital structure related to the RPIC in combat sports. Our sociological analysis revealed two key findings: (a) rationalisation of playing hurt and (b) reproduction of the RPIC.

First, athlete participants recognised the after-effects of playing with pain and injury. Still, they frequently chose this self-destructive behaviour based on the group’s implicit belief that playing hurt would yield rewards (e.g. cultural, social, economic, and performance capital). As gatekeepers of various resources and higher social positions in sportsnets (Jones et al. Citation2011; Nixon Citation1992; Purdy Citation2018), coach participants (ex-athletes) also solidified the existing structure of the health-compromising game by rewarding athletes’ behaviour of playing hurt with certain benefits. In this interest alignment, the agent’s profit-seeking aspiration rationalised playing hurt as an investment for social energy (Bourdieu Citation1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) to occupy higher positions in the field.

Second, the more athletes absorbed themselves in the capital game utilising health as a token, the more prominent the habitus of playing hurt became in the field; in turn, the RPIC practice recurs through the capital–habitus–field nexus (Bourdieu Citation1984). This reproduction mechanism gravitated our participants’ choices towards an identical career trajectory, uni-taste, and limited subversion strategy, leading them to encounter strong hysteresis (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Although individuals can overcome difficulties from hysteresis through endeavours such as intentionally disconnecting networks and eliminating cultural clues from one’s home field (e.g. Lavallee and Robinson Citation2007; Lehmann Citation2014; Nam, Love, and Rider Citation2022), nearly all participants did not attempt to do so. Since they had already acquired sport-specialised capital over a long period (11–22 years) in socially isolated training institutions, the desire to retain the value of their accumulated capital drove individuals to re-immerse in the game, trapping themselves in ‘the circle of the victim becoming another perpetrator’ (NHRCK Citation2020, 8) of playing hurt. In this re-cyclic system, coaches could perpetuate the enduring nature of dominant cultural ideologies by normalising emotional and physical abuse (i.e. pushing players to keep training while being sick, in pain, exhausted, or injured) based on their athletic experiences (e.g. Cavallerio, Wadey, and Wagstaff Citation2016; McMahon et al. Citation2020).

These findings contribute to linking individual agents’ willingness to play hurt (e.g. Jessiman-Perreault and Godley Citation2016; Mayer and Thiel Citation2018; Schneider et al. Citation2019; Schnell et al. Citation2014) with the supply–demand structure of capital related to the RPIC in combat sports. This agency–structure continuum unpacks the underlying mechanism of how individuals have negotiated the cost and benefit of health-compromising practices using certain strategies and how combat sport group members’ collective meaning of risk, pain, and injury is socially constructed. Given that merely emphasising health values seldom induces major changes in risk-taking behaviour (Liston et al. Citation2018), modifying the existing supply–demand structure could be an alternative approach to alleviate the phenomenon of playing hurt. In this vein, our findings can provide relevant sports institutions with insights regarding possible interventions (e.g. policy, regulation, or education). As agents desire to accrue capital by weighing certain behaviours’ costs and benefits based on game rules (Bourdieu Citation1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992), athletes would be reluctant to engage in this health-compromising game without profits.

Based on our sociological investigation, a further methodological effort can offer a deeper understanding of this topic. The current study employed semi-structured and photo-elicitation interviews to grasp former/present athletes’ realities of playing hurt in their own language (Patton Citation2015). Although these interview methods are useful in accessing participants’ indigenous meaning of playing hurt, they entail a methodological risk in that informants’ retrospective explanations of motivations and experiences may not align with those at the time of action (Dempsey Citation2010). Alternatively, a combination of the first-third perspective camcorders and video-based stimulated recall interviews (e.g. Ryou, Choi, and Lee Citation2023) can elicit participants’ ulterior motives behind the (playing hurt-related) behaviour while maintaining its naturalistic context (Mackenzie and Kerr Citation2012). This bricolage of methods enables participants to revisit their in-situ actions and discuss what, how, and why ‘“I did”, instead of “I might have”’ in recorded activities (Dempsey Citation2010, 350); therefore, it could support follow-up in-depth examinations of athletes’ health-compromising games through the emic-etic continuum (Patton Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juyoung Ryou

Juyoung Ryou is a doctoral researcher at Loughborough University. His research focuses on sport coaching-related issues (e.g. coach-athlete interaction, coach practice, athlete learning, and safe sport environment).

Eol Lee

Eol Lee graduated with a master's degree in sport science from Seoul National University (2018). His dissertation was about elite players' academic experiences. He has 15 years of career in wrestling and played at the international level as a national representative athlete. Afterwards, he worked as a head coach in a university wrestling team for six years and the junior national team for a year.

Notes

1. Several sport studies have interpreted athletes’ performance as Shilling’s physical capital (e.g. Purdy, Jones, and Cassidy Citation2009). However, unlike those studies, which barely distinguish between athletes’ performance and health, this study defines kinaesthetic sense and technical skills as performance capital (Miller Citation2017) to understand the relationship between athletes’ performance and health in more detail.

2. According to Bourdieu (Citation1986), there are three forms of cultural capital: (i) the embodied form is a long-lasting inclination, existing as a culture or taste in one’s body; (ii) the objectified form is a materialised cultural product such as paintings, books, and musical instruments; and (iii) the institutionalised form is a degree or certificate that individuals acquire through formal education. This study concentrates on the first form to delve into combat groups’ embodied tastes for playing hurt.

References

- AlHashmi, Reem, and Christopher R. Matthews. 2021. “‘He May Not Be Qualified in It, but I Think He’s Still Got the Knowledge’: Team Doctoring in Combat Sports.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 57 (1): 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220987136.

- Anderson, Lynley, and Steve Jackson. 2013. “Competing Loyalties in Sports Medicine: Threats to Medical Professionalism in Elite, Commercial Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48 (2): 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690211435031.

- Atkinson, Michael. 2010. “Fell Running in Post‐Sport Territories.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 2 (2): 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.488020.

- Atkinson, Michael. 2019. “Sport and Risk Culture.” In The Suffering Body in Sport: Shifting Thresholds of Pain, Risk and Injury, edited by Kevin Young, 5–21. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Barker-Ruchti, Natalie, and Dean Barker. 2017. Sustainability in High Performance Sport: Current Practices-Future Directions. New York: Routledge.

- Barker-Ruchti, Natalie, Astrid Schubring, Anna Post, and Stefan Pettersson. 2019. “An Elite Athlete’s Storying of Injuries and Non-Qualification for an Olympic Games: A Socio-Narratological Case Study.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (5): 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1605405.

- Blackett, Alexander David, Adam Evans, and David Piggott. 2017. “Why ‘The Best Way of Learning to Coach the Game is Playing the Game’: Conceptualising ‘Fast-Tracked’ High-Performance Coaching Pathways.” Sport, Education and Society 22 (6): 744–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1075494.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, 241–258. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. Sociology in Question. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2004. Science of Science and Reflexivity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bradbury, Steven, Jacco van Sterkenburg, and Patrick Mignon. 2018. “The Under-Representation and Experiences of Elite Level Minority Coaches in Professional Football in England, France and the Netherlands.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (3): 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216656807.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Cavallerio, Francesca, Ross Wadey, and Christopher R.D. Wagstaff. 2016. “Understanding Overuse Injuries in Rhythmic Gymnastics: A 12-Month Ethnographic Study.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 25:100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.05.002.

- Charlesworth, Hannah, and Young, Kevin. 2004. “Why English Female University Athletes Play with Pain: Motivations and Rationalisations.” In Sporting Bodies, Damaged Selves: Sociological Studies of Sports-Related Injuries, edited by Kevin Young, 163–180. Bingley: Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1476-2854(04)02008-4

- Chen, Yanbing, Conor Buggy, and Seamus Kelly. 2019. “Winning at All Costs: A Review of Risk-Taking Behaviour and Sporting Injury from an Occupational Safety and Health Perspective.” Sports Medicine-Open 5 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0189-9.

- Chroni, Stiliani, Sigurd Pettersen, and Kristen Dieffenbach. 2020. “Going from Athlete-To-Coach in Norwegian Winter Sports: Understanding the Transition Journey.” Sport in Society 23 (4): 751–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1631572.

- Conway, Fiona, Marianne Domingues, Robert Monaco, Laura M. Lesnewich, Anne E. Ray, Brandon L. Alderman, Sabrina M. Todaro, and Jennifer F. Buckman. 2020. “Concussion Symptom Underreporting among Incoming NCAA Division I College Athletes.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: Official Journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine 30 (3): 203–209. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000557.

- Cope, Ed, Stephen Harvey, and David Kirk. 2015. “Reflections on Using Visual Research Methods in Sports Coaching.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 7 (1): 88–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.877959.

- Dempsey, Nicholas. 2010. “Stimulated Recall Interviews in Ethnography.” Qualitative Sociology 33 (3): 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-010-9157-x.

- Dohlsten, John, Natalie Barker-Ruchti, and Eva-Carin Lindgren. 2021. “Sustainable Elite Sport: Swedish Athletes’ Voices of Sustainability in Athletics.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 13 (5): 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1778062.

- Edwards, Jonathan. 2021. “A Texas Deputy Attorney General Called Simone Biles a ‘National Embarrassment.’ His Boss Publicly Disagreed.” The Washington Post. July 29, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/07/29/texas-deputy-attorney-general-simone-biles/.

- Ford, Holley. 2021. “1996 Olympic Gymnast Kerri Strug Praises Simone Biles’ Decision.” NBC Sports. July 28, 2021. https://www.nbcsportswashington.com/tokyo-olympics/1996-olympic-gymnast-kerri-strug-praises-simone-biles-decision.

- Hughes, Robert, and Jay Coakley. 1991. “Positive Deviance Among Athletes: The Implications of Overconformity to the Sport Ethic.” Sociology of Sport Journal 8 (4): 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.8.4.307.

- Iyer, Sunita. 2022. “South Koreans Salute ‘Superhero’ Son Heung-Min’s Grit by Donning Zorro-Like Mask at Qatar World Cup 2022.” Asianet Newsable. November 24, 2022. https://newsable.asianetnews.com/sports/football-uruguay-south-korea-fans-applaud-superhero-son-heung-min-s-grit-by-donning-zorro-like-mask-at-qatar-world-cup-2022-snt-rluzi2.

- Jessiman-Perreault, Geneviève, and Jenny Godley. 2016. “Playing Through the Pain: A University-Based Study of Sports Injury.” Advances in Physical Education 6 (3): 178–194. https://doi.org/10.4236/ape.2016.63020.

- Jones, Robyn L., Paul Potrac, Chris Cushion, Lars Tore Ronglan, R. L. Jones, P. Potrac, C. Cushion, and L. T. Ronglan. 2011. The Sociology of Sports Coaching. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203865545.

- Kidder, Jeffrey L. 2013. “Parkour: Adventure, Risk, and Safety in the Urban Environment.” Qualitative Sociology 36 (3): 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-013-9254-8.

- Kim, Yoon Jin, Marcelle C. Dawson, and Tania Cassidy. 2020. “Crafting a One-Dimensional Identity: Exploring the Nexus Between Totalisation and Reinvention in an Elite Sports Environment.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (1): 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1555660.

- Kohe, Geoffrey Z., and Laura G. Purdy. 2016. “‘In Protection of Whose Wellbeing’? Considerations of ‘Clauses and A/Effects’ in Athlete Contracts.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 40 (3): 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516633269.

- Lavallee, David, and Hannah K. Robinson. 2007. “In Pursuit of an Identity: A Qualitative Exploration of Retirement from Women’s Artistic Gymnastics.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 8 (1): 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.05.003.

- Lehmann, Wolfgang. 2014. “Habitus Transformation and Hidden Injuries: Successful Working-Class University Students.” Sociology of Education 87 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040713498777.

- Lim, Seung-Yup, and Jae-Woo Park. 2012. “Rethinking Media Framing on the Discourse of Fighting-Spirit Under Injury in Korean Sports.” The Korean Journal of Sport 10 (3): 103–114.

- Liston, Katie, Mark McDowell, Dominic Malcolm, Andrea Scott-Bell, and Ivan Waddington. 2018. “On Being ‘Head Strong’: The Pain Zone and Concussion in Non-Elite Rugby Union.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (6): 668–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216679966.

- Mackenzie, Susan Houge, and John H. Kerr. 2012. “Head-Mounted Cameras and Stimulated Recall in Qualitative Sport Research.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 4 (1): 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2011.653495.

- Malcolm, Dominic. 2006. “Unprofessional Practice? The Status and Power of Sport Physicians.” Sociology of Sport Journal 23 (4): 376–395. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.23.4.376.

- Malcolm, Dominic, and Kenneth Sheard. 2002. “‘Pain in the Assets’: The Effects of Commercialization and Professionalization on the Management of Injury in English Rugby Union.” Sociology of Sport Journal 19 (2): 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.19.2.149.

- Maton, Karl. 2012. “Habitus.” In Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts, edited by Michael Grenfell, 48–64. London: Acumen Publishing.

- Mayer, Jochen, and Ansgar Thiel. 2018. “Presenteeism in the Elite Sports Workplace: The Willingness to Compete Hurt Among German Elite Handball and Track and Field Athletes.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 53 (1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216640525.

- MCST (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism). 2019a. Sports Innovation Committee’s Second Recommendation. Sejong: Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

- MCST. 2019b. Sports Innovation Committee’s Sixth Recommendation. Sejong: Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

- McMahon, Jenny, Chris Zehntner, Kerry R. McGannon, and Melanie Lang. 2020. “The Fast-Tracking of One Elite Athlete Swimmer into a Swimming Coaching Role: A Practice Contributing to the Perpetuation and Recycling of Abuse in Sport?” European Journal for Sport and Society 17 (3): 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2020.1792076.

- Messner, Michael A. 1992. Power at Play: Sports and the Problem of Masculinity. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Miller, Diana L. 2017. “Gender and Performance Capital Among Local Musicians.” Qualitative Sociology 40 (3): 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-017-9360-0.

- Nam, Benjamin H., Adam Love, and Robert A. Rider. 2022. “Symbolic Power and Dual Careers of Athletes: Successful Career Transition Experiences of Korean College Athletes Who Quit Sport.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 39 (3): 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2022.2045960.

- NHRCK (National Human Rights Commission of Korea). 2019. The Complete Enumeration on Human Rights Condition and (Sexual) Violence in Sports Area. Seoul: National Human Right Commission of Korea.

- NHRCK. 2020. Guidelines of Sport Rights. Seoul: National Human Rights Commission of Korea.

- Nixon, Howard L. 1992. “A Social Network Analysis of Influences on Athletes to Play with Pain and Injuries.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 16 (2): 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372359201600208.

- Nixon, Howard L. 1993. “Accepting the Risks of Pain and Injury in Sport: Mediated Cultural Influences on Playing Hurt.” Sociology of Sport Journal 10 (2): 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.10.2.183.

- Ogura, Kizo. 2021. Korean is a Philosophy. Tokyo: Kodansha and Seoul: Mosinsaram.

- Palmer, Debbie, Dale J. Cooper, Carolyn Emery, Mark E. Batt, Lars Engebretsen, Brigitte E. Scammell, Patrick Schamasch et al, 2021. “Self-Reported Sports Injuries and Later-Life Health Status in 3357 Retired Olympians from 131 Countries: A Cross-Sectional Survey among Those Competing in the Games between London 1948 and PyeongChang 2018.” British journal of sports medicine 55 (1): 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101772.

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Phoenix, Cassandra. 2010. “Seeing the World of Physical Culture: The Potential of Visual Methods for Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 2 (2): 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.488017.

- Pike, Elizabeth C. J. 2005. “‘Doctors Just Say “Rest and Take Ibuprofen”’: A Critical Examination of the Role of ‘Non-Orthodox’ Health Care in Women’s Sport.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 40 (2): 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690205057199.

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1.

- Purdy, Laura. 2018. Sports Coaching: The Basics. New York: Routledge.

- Purdy, Laura, Robyn Jones, and Tania Cassidy. 2009. “Negotiation and Capital: Athletes’ Use of Power in an Elite Men’s Rowing Program.” Sport, Education and Society 14 (3): 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320903037796.

- Ristolainen, Leena, Jyrki A. Kettunen, Urho M. Kujala, and Ari Heinonen. 2012. “Sport Injuries as the Main Cause of Sport Career Termination Among Finnish Top-Level Athletes.” European Journal of Sport Science 12 (3): 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.566365.

- Roderick, Martin. 1998. “The Sociology of Risk, Pain, and Injury: A Comment on the Work of Howard L. Nixon II.” Sociology of Sport Journal 15 (1): 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.15.1.64.

- Roderick, Martin. 2006. “Adding Insult to Injury: Workplace Injury in English Professional Football.” Sociology of Health and Illness 28 (1): 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00483.x.

- Roderick, Martin, Ivan Waddington, and Graham Parker. 2000. “Playing Hurt: Managing Injuries in English Professional Football.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 35 (2): 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269000035002003.

- Rynne, Steven. 2014. “‘Fast Track’ and ‘Traditional Path’ Coaches: Affordances, Agency and Social Capital.” Sport, Education and Society 19 (3): 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.670113.

- Ryou, Juyoung. 2021. “Exploring the Organized Realities and Education Logics in the Qualification Training System for Level 2-Sport-For-All-Coach Through the Analysis of Coordination Process.” Korean Journal of Sport Science 32 (1): 65–84. https://doi.org/10.24985/kjss.2021.32.1.65.

- Ryou, Juyoung., Euichang. Choi, and Okseon. Lee. 2023. “Pedagogical Touch: Exploring the Micro-Realities of Coach–Athlete Sensory Interactions in High-Performance Sports.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2023.2185600.

- Safai, Parissa. 2003. “Healing the Body in the ‘Culture of Risk’: Examining the Negotiation of Treatment Between Sport Medicine Clinicians and Injured Athletes in Canadian Intercollegiate Sport.” Sociology of Sport Journal 20 (2): 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.20.2.127.

- Schmid, Michael J., Merlin Örencik, Jürg Schmid, and Achim Conzelmann. 2023. “Linking Sports-Related and Socio-Economic Resources of Retiring Olympic Athletes to Their Subsequent Vocational Career.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 58 (5): 809–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902221123881.

- Schneider, Sven, Johannes Sauer, Gregor Berrsche, Christin Löbel, and Holger Schmitt. 2019. “‘Playing Hurt’ – Competitive Sport Despite Being Injured or in Pain.” Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin 70 (2): 43–52. https://doi.org/10.5960/dzsm.2019.365.

- Schnell, Alexia, Jochen Mayer, Katharina Diehl, Stephan Zipfel, and Ansgar Thiel. 2014. “Giving Everything for Athletic Success! – Sports-Specific Risk Acceptance of Elite Adolescent Athletes.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15 (2): 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.012.

- Spencer, Dale C. 2012. “Narratives of Despair and Loss: Pain, Injury and Masculinity in the Sport of Mixed Martial Arts.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 4 (1): 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2011.653499.

- Turner, David. 2008. “The Usual Suspects: Critical Consideration of the Fast Tracking of Ex-Elite Athletes into High Profile Coaching Roles.” Coaching Edge 13:18–19. https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/handle/2299/6456.

- Wacquant, Loïc J. D. 2004. Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Young, Kevin. 2012. Sport, Violence and Society. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874615.

- Young, Kevin, Philip White, and William McTeer. 1994. “Body Talk: Male Athletes Reflect on Sport, Injury, and Pain.” Sociology of Sport Journal 11 (2): 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.11.2.175.