ABSTRACT

In answer to appeals for more participatory frameworks to advance qualitative methodologies, this article shows how a novel emancipatory approach to disability research produced significant impact and learnings. We (academics and non-academics) explain how ethical problems experienced in traditional qualitative research designed to understand how grassroots disabled activists in the UK were reacting to the International Paralympic Committee’s WeThe15 campaign, led to the emergence of an ‘emancipatory approach to research’. We discuss how a small group of creative non-academic disabled activists, artists and athletes formed a foundational project called Project Group Spirit to unpick concerns about the WeThe15 campaign and formulate activist interventions in the context of Paralympic sport. Three sets of action-orientated activist findings that arose from the project are described: ‘Disabled Athletes and Artists, and their Activism’, ‘Engaging with WeThe15’ and ‘The Moral High Ground’. These themes, we show, provided the groundwork for the group to organise themselves into a wider principled project called the Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group). The article ends by discussing a) the potential impact of the KEI Group b) academic barriers to emancipatory approaches and c) ways to evaluate emancipatory disability research. This article is an example of emancipatory research in action to help foster high-quality participatory frameworks going forward.

Introduction and background

Recently, there have been appeals for more participatory approaches to advance qualitative methods and methodologies in sport research (Smith et al. Citation2022). However, there are very few practical examples that have answered such calls (see, e.g., Sharpe et al. Citation2022; Smith et al. Citation2023). This article offers a practical example of how a participatory approach called ‘emancipatory disability research’ was used in disability sport studies. Specifically, a case is made for a paradigmatic shift towards researching sport, disability and social change topics. We make this case by reflecting on ethical problems encountered when academics employed a ‘traditional qualitative research’ approach to understand how grassroots disabled activists in the UK were reacting to the new ‘top-down’ WeThe15 campaign.Footnote1 We show how a ‘spontaneous’ shift towards a progressive ‘emancipatory disability research’ approach (Barnes Citation2002, Griffiths Citation2022b, Oliver Citation1992), were disabled activists had power and control in the production of knowledge, produced significant social impact and learnings.

There has been growing interest in studies specifically focused on disability activism within and around the context of Paralympic sport (Haslett and Smith, Citation2022). This sport, disability and activism literature can be contextualised within wider bodies of research on non-disabled athlete activism (see Magrath Citation2022), the social legacy potential of Paralympic sport (Brittain and Beacom Citation2016, Pappous and Brown Citation2018) and disability activism/advocacy (Berghs et al. Citation2020, Griffiths Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Soldatic et al. Citation2019). Much of this research is about the activism/advocacy of elite Para athletes, for example, empirical studies carried out in different cultural contexts (e.g. South Korea, UK) showed the various ways that elite Para athletes (e.g. Paralympians) either engage or do not engage in various forms of activism and advocacy (Braye Citation2016, Choi, Haslett, and Smith Citation2019). One interesting aspect of these studies is the way researchers suggested how different forms of activism and advocacy promote or reproduce different understandings of disability, such as a Social Model or a Medical/Individual Model understanding of disability (see, e.g., Smith, Bundon, and Best Citation2016).

The Medical/Individual Model of disability is the dominant way of understanding disability. This model views disability as a medical problem that resides in the individual (Goodley, Citation2016). A ‘person with a disability’ from this viewpoint is an individual who has had a personal tragedy that should be overcome rather than accommodated for. In contrast, from a Social Model understanding (see Oliver Citation2013), disability consists of the barriers that a person with impairment experiences, because of the way in which society is organised, which excludes or devalues them. A ‘disabled person’ from this lens is disabled by society and attention is directed at an inaccessible society that erected barriers that effectively disable participation. Acknowledging that disabled people across the world refer to themselves in different ways for different reasons, such as ‘people with disabilities’ as recommended terminology by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), the term ‘disabled people’ is used in this article, following the Social Model.

Researchers have also questioned whether Paralympic sport either is, or is not, a suitable context to promote disability activism. This research often involved the views of disabled activists and/or critical disability studies scholars (Braye, Dixon, and Gibbons, Citation2013, Peers Citation2018). The interesting contemporary development in this literature concerned how some disabled activists seem to be moving from eschewing to accepting Paralympic sport as a suitable context to promote disability equality. For example, Peers (Citation2018) explained that there has been little mention of the Paralympic movement in the history of the disability rights movement because elite disability sport structures can, in fact, perpetuate discrimination against disabled people in society (also see, e.g., Clifford [Citation2020, 184] on this subject). However, since then, the International Disability Alliance (IDA) and other disability advocacy organisations have joined forces with the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) to use the Paralympic platform to campaign for the rights of all disabled people, globally, through the WeThe15 campaign (see https://www.wethe15.org/).

Cementing its strategic shift towards disability-rights advocacy (IPC Citation2019), the IPC used the Tokyo Paralympic Games 2020 (held in 2021) as a platform to launch the WeThe15 campaign. This ambitious initiative brought together the largest ever coalition of international organisations (e.g. IPC, IDA, UNESCO) with the self-described aim of ending discrimination against disabled people (i.e. 15% of the whole world) within 10 years. The WeThe15 campaign is one of a rising number of new ambitious global initiatives or innovations that promote disability equality in different contexts that either implicitly or explicitly use Paralympic sport as a platform to promote their initiatives. For example, The Valuable 500 in business (see www.thevaluable500.com) or the UK Aid funded Para Sport Against Stigma project (see https://at2030.org/para-sport-against-stigma/), run through the Global Disability and Innovation Hub (see www.disabilityinnovation.com), aims to use Paralympic sport as a tool to challenge disability stigma and discrimination in Sub-Saharan Africa. These new global initiatives take a ‘top-down’ approach to social change that essentially imposes change in a hierarchical way on disabled people (Beresford Citation2021, 112). This contrasts with social change approaches owned by disabled people with activism rooted within grassroots disability communities (see Beresford Citation2021, Clifford Citation2020).

The purpose of this article is to show the benefit of an ‘emancipatory research paradigm’ in which non-academic grassroots disabled activists had power and control in the production and exchange of knowledge. Rather than conducting academic research, the article is a commentary by us, as authors [Author A, B and C], a mix of academics, non-academics, activists and artists, based on our personal experiences of being involved in a project that formed organically to exchange knowledge about disability, sport and social activism. Throughout the article, we acknowledge and reflect upon the formation, organisation, publicity and power dynamics of the Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group) – an exploratory project dictated by grassroots disabled activists that sit outside academia. This progressive approach, as we argue throughout the article, can inform academic knowledge regarding participatory approaches to research, and help academics contribute towards the social and political emancipation of disabled people.

In terms of methodological advancement regarding qualitative research in sport, the contribution of this article is a practical example of an emancipatory disability approach, in action, to help promote and foster high-quality participatory research approaches going forward. Moreover, shifting power relations in the production of knowledge is significant as there is a dearth of emancipatory participatory approaches in disability sport studies (see Haslett Citation2023, Spencer and Molnár Citation2022) especially when compared to the wider field of disability studies (see, e.g., Liddiard et al. Citation2019). The motivation for this approach arose, as will be discussed next, from frustrations with power relations and ethical problems experienced on a different project that used a ‘traditional qualitative research paradigm’, dictated by academics. We show how an engaging emancipatory disability approach can spontaneously form when academics and non-academics experience problems with ‘traditional’ research, and then work together to address such problems.

Reflecting on ‘top-town’ disability research: problems with the ‘traditional qualitative paradigm’

I, Author A (non-disabled academic), was involved in a global internationally funded research project to evaluate the WeThe15 campaign. Within this interdisciplinary project, involving multiple researchers from across different countries, my task was to capture how grassroots disabled activists from the UK were reacting to the WeThe15 campaign. The research design on this aspect of the wider global project was not dissimilar to much research already carried-out in the field of sport, disability and social activism – the ‘traditional qualitative paradigm’. Let me explain what I mean.

By ‘traditional qualitative paradigm’ I am specifically referring to a history of disability research conducted by non-disabled academics for disabled people (Barnes Citation1996) including qualitative studies in the context of disability, sport and activism research (see Haslett and Smith, Citation2022 for overview of such studies). For me and others, this traditional approach involves teams of non-disabled researchers, like me, working more on participants (e.g. disabled athletes and activists) as subjects in the research process rather than with disabled people as collaborators in the process in more equitable ways (Macbeth Citation2010, Smith et al. Citation2022). In this approach, non-disabled academics are positioned as the experts in the production of knowledge and design of studies about disabled people.

In the UK, I encountered specific barriers employing this traditional qualitative approach to recruit and engage grassroots disability activists in research about the WeThe15 campaign. Some activists, for example, declined to take part in interviews or focus groups on the basis that disabled activists should be remunerated (paid) for their knowledge and time, especially in ‘top-down’ funded research projects. I also found that some disabled activists have become resistant to this ‘passive’ research approach as they felt their information was being used to benefit non-disabled researchers and funders, often at their expense. Essentially, the traditional qualitative approach, especially when employed in the context of ambitious ‘top-down’ disability initiatives like the WeThe15 campaign, is also perceived as a ‘top-down’ research approach by some grassroots disabled activists in the UK.

Reflecting on this experience, I feel the traditional qualitative paradigm, when used on its own in the context of sport and disability activism research, will not be taken seriously by many disabled activists. It can be perceived as a ‘parasite approach’ where the only people benefiting are researchers and their career aspirations (Dolmage Citation2017, Fitzgerald Citation2009, Macbeth Citation2010, Stone and Priestley Citation1996). As Goodley and Moore (Citation2000) said over 20 years ago, ‘there is a wide gap between the rhetoric of research outputs (which promote the liberation of disabled people) and the discourses and social practices in which we work (which shape careers in the academic world)’ (816). This gap is still significant and evident in the contemporary field of disability sport studies. For example, Spencer and Molnár (Citation2022) showed how disabled people are still predominantly considered as participants/subjects in disability sport research designs in contrast to partners or leaders in the production of knowledge.

Organic emancipatory research rooted in grassroots disability activism

I, Author C (non-academic disabled activist and artist), having been involved in grassroots disability activism for over 40 years as a disabled person and having bumped heads repeatedly with those groups and organisations run and controlled by non-disabled disability professionals, I was always looking for ways in which we could shift the power relations in this area and show that we could be included as leaders rather than being portrayed as passive recipients of their largesse.

Following a traditional research interview with Author A about the WeThe15 campaign, in which I was a participant, we went on to discuss the possibility of developing an emancipatory approach to research, where disabled people would have more power and control over the research process. Author A and I co-applied for and obtained some seed funding from Author A’s institution to form a working relationship between academic researchers and grassroots disabled activists. The funding was used to pay for the involvement of a small group of disabled people who all had previous experience as disabled athletes, artists and activists, but more importantly, were all strong advocates of the Social Model understanding of disability.

The plan was to meet once a week to discuss the issues around involving disabled athletes, particularly Paralympians with all their attendant publicity, in disability activism. The members of the group, which we called Project Group Spirit, not only brought their own experiences to the debates but were also able to reach out to a wider network of their disabled peers throughout the UK. Another of the issues discussed by the group was the negative reaction by disabled people in the UK when they were approached to possibly collaborate with the WeThe15 Campaign. Many valid explanations were unearthed, and it was decided that we would continue examining these issues, as a group, after Project Group Spirit ended.

The result was the formation of the Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group). The KEI Group continued to grow as we invited more disabled people with relevant experience to join our focus on promoting the emancipatory paradigm; demystifying the structures and processes which create disability, and the establishment of a workable dialogue between the research community and disabled people.

The emancipatory disability paradigm: progressive activist research by, for and with, disabled people

An emancipatory disability research paradigm concerns changing the power relations in research production from research done on disabled people towards research carried-out with or dictated by disabled people (Oliver Citation1992). However, it is just one of many participatory frameworks that claims to work with, not on, disabled people such as ‘participatory action research’, ‘co-designed’, ‘co-production’, ‘public and patient involvement’, or ‘user-centred design research’. Importantly, all these approaches are contested in the sense that all have the potential to include disabled people in meaningful and impactful ways or in problematic tokenistic ways (see Haslett Citation2023).

Therefore, in contrast to other participatory approaches noted, we see ‘emancipatory disability research’ as an inherently political approach with a need to explicitly attend to/shift power dynamics. For us, this means research that is led and controlled by disabled people with experience and expertise to advance the social and political emancipation of disabled people (Griffiths Citation2022b). According to Oliver (Citation1992) and developed by Barnes (Citation2002) and others (McColl et al. Citation2013, Pinto Citation2019, Stone and Priestley Citation1996, Zarb Citation1992) it is a dynamic and engaging process underpinned by core principles, such as:

Control: disabled people must actively participate in all stages of the research process.

Accountability: the research process must be transparent, and outcomes should support activism.

Practical outcomes: research must produce knowledge that is useful for disabled people’s movements.

Research must be led by a Social Model understanding of disability.

Researchers must be clear about their epistemological and ontological positions.

Research must value and foreground lived experience of disability.

Working to change the power relations in the production of knowledge clearly suits research on sport, disability and social activism topics because people who live the disabling barriers (see Thomas Citation2014), such as disabled athletes and activists, and who are developing or have developed strategies to challenge such barriers, will help us better to understand the root causes of inequality and oppression. In the rest of this article, we show the potential of an emancipatory approach to produce impact and learnings by commenting and reflecting on how a group of non-academic activists formed Project Group Spirit as a foundational project to organise themselves into the Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group). This article is just one of many outputs from KEI Group projects that have gone to different audiences (see below sub-section on KEI Group).

Project group spirit

Who was involved, what happened, how and why

Author C and Author A co-applied for, and received, university seed funding to start ‘a project’ underpinned by emancipatory principles involving academics and grassroots activists (i.e. non-academics) that could potentially lead to carrying out, for example, co-produced research in the context of disability, sport and social activism. In line with an emancipatory approach to research and grassroots activism, Author C had full control over how the seed funding budget was spent, who was involved, how they were remunerated, what was done and how information arising from the project should be used going forward. The project, which came to be named Project Group Spirit, was viewed as a foundational project, organic in nature, which could lead to something more meaningful, therefore no specific outcomes or expectations were set.

Author C decided to purposefully recruit six disabled activists (e.g. artists and athletes) from his networks in the UK who he felt would ‘think sideways about disability, sport and social activism’ (i.e. think outside the box, or radically, about disability). The disabled activists involved had combined experience and expertise in areas such as elite-level Paralympic sport, the Disability Arts movement as well as campaigning, protesting and advocating for disability rights and equality. While all the activists involved were connected to grassroots movements and/or deaf and disabled people’s organisations (DDPOs), they joined this project as individuals in contrast to representatives of organisations or campaigns.

Accounting and budgeting for accessibility requirements, Author C facilitated four 1-hour Zoom sessions, weekly, across January 2022. Before each meeting, Author C produced rough agendas, sent out reading materials and suggested research tasks for the group to undertake before the next meeting (e.g. ‘this week, find out what you can about who controls the organisations connected to the WeThe15 campaign’). The Zoom sessions were facilitated by Author C on Author A’s university platform and were recorded for note taking purposes only. Author C produced detailed analytical notes of each session (e.g. approx. 2000 words of interesting findings in contrast to descriptive ‘meeting minutes’) and circulated these to the Group members each week for feedback. Considering perceived power dynamics in the project from the outset, Author C also decided that it would be appropriate that Author A, being a non-disabled academic, should not attend the initial three Zoom sessions but be invited by the Group to come to the final (fourth) Zoom session. Following the Project Group Spirit sessions, a document was produced by Author C that encapsulated the various topics and themes that had been discussed over the four-week period with ideas for next steps.

Author C and the Group members were unable to attract the interest of young, currently active, high-profile UK Paralympians in participating in the discussions, although some additional input was achieved through accessing their various networks. This could have come from a combination of reasons such as younger Paralympians avoiding the project due to the perceived radical make-up of the Group or a lack of interest in being labelled as a political activist at this stage in their sporting lives/careers (see Smith, Bundon and Best Citation2016).

As the Project Group Spirit discussions were not academic research, this project did not fall under the remit of university ethics approval. Moreover, a key principle of forging relationships between academics and non-academics is that prior ethical approval is not needed to involve members of the public in decisions towards the production of research (see NIRH Citation2020, Citation2021). In contrast, social justice ethical approaches, with a political aim of representing the voices and decisions of disabled people in the process of research, were foregrounded in this project (Mietola, Miettinen, and Vehmas Citation2017). For example, because Project Group Spirit emerged considering problems discussed in ‘traditional’ research, Author A’s role was not to lead, but act as a resource for this emancipatory project through academic status and access to networks, knowledges, funding opportunities and resources (i.e. to support the administration of the activities and provide an accessible Zoom platform to meet on). Nonetheless, institutional ethical procedures and principles were also drawn upon for important decisions across the project. For example, after each Project Group Spirit Zoom meeting, Author A sent Author C an MP3 recording of the meeting and then deleted the recording from the Zoom platform.

The organic discussions across the four Zoom sessions ranged over many different aspects of sport, disability and social activism. One main area involved exploring the potential for disabled athletes, in particular Paralympians, to participate in actions and protests in the UK with other non-sports focused disabled people. Another key area involved discussing whether disabled people in the UK should collaborate with those international ‘top-down’ organisations who created the WeThe15 campaign.

Authors A and C used the Group Spirit zoom session notes and subsequent dialogue as data to create themes for this article. As highlighted by Smith et al. (Citation2022), qualitative methods are suitable for equitable and experientially informed projects involving academics with experience in qualitative research (Author A) in partnership with non-academics (Author C). Ideas from Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) reflexive thematic analysis were utilised to create the themes, signalling, for example, commitment to ‘reflective and thoughtful’ engagement with the information gathered. Inductive reasoning was focused on to bring the contextual experiences of those involved to generate socially useful knowledge (Oliver Citation1992). To illustrate points across the themes, cartoons produced by Author C and extracts from the Project Group Spirit session notes are shown. In addition, the activist findings are connected to concepts and ideas in relevant academic literature. The themes, outlined next, are described as action-orientated because of the activist influence in the process. They became the foundations for the organic outcome of Project Group Spirit that will be discussed after – the establishment of the Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group).

Project group spirit: action-orientated activist findings

”Athletes just want to play, just like artists want to create”: disabled athletes and artists, and their activism

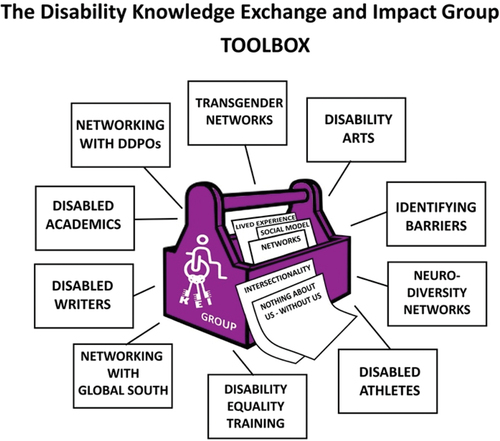

This theme captures how Project Group Spirit discussions involved unpicking the differences between disabled athletes and disabled artists in terms of their activism. To shift power relations, the group also came up with ideas on how athletes and disabled artists can do activism together.

The group often returned to the area of discussing differences between athletes and activists in terms of motivations and barriers to engage in disability activism. They addressed the notion that Paralympians do not really use their sporting platforms to engage in raising awareness of the barriers faced by disabled people. By this they meant high profile disabled athletes in the UK did not appear to be interested in the struggle that was taking place between disabled people and the government departments, service providers and charities that claimed to support them.

Relating to findings from Smith et al. (Citation2016) about how Para athletes are more or less ‘politically activist’ at different career stages, the Group surmised that these days elite disabled athletes tend to be quite young, not very politically aware and face fewer barriers than previous generations. It was also pointed out across the sessions that there were many different groups of disabled athletes who may have different motivations to engage in activism (Hughes Citation2009). These included 1) non-disabled athletes who, having experienced injury, changed to being disabled athletes, 2) non-disabled people who, having experienced injury, became disabled athletes after being introduced to sport as a form of therapy and 3) people who have been disabled since birth who became involved in sport.

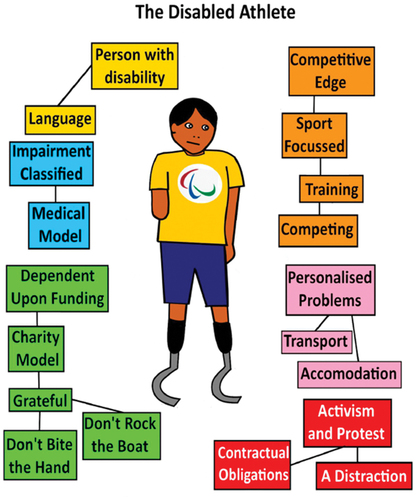

A diagram of a cartoon depicting a disabled athlete surrounded by the forces that impact upon their activism. An athlete with two running blades wearing a t-shirt with the IPC logo.

A diagram of a cartoon depicting a disabled activist surrounded by the forces that impact upon their activism. A person dressed in purple holding a rights not charity placard.

The group went on to talk about how disabled artists do not often understand that disabled athletes do have to fight to be accepted as competitive athletes, to get funding, to access sports halls and hotels, to take wheelchairs on planes for competitions and how they are or are not reported in the press (see, e.g. Rees, Robinson, and Shields [Citation2019] on media representations of Para athletes). They also have to fight for these things in the context of policy/contractual bans on speaking out against governments and sponsors. Group members also discussed how non-sporty disabled artists have a lack of understanding of how it feels to be an athlete; the adrenaline and endorphin rush, the coming together with other disabled people and the feeling of inclusion that is generated. The Group agreed that it would be understandable when disabled athletes get perplexed with opposition from within the disabled community about their ‘politics’. As this extract from Author C’s Zoom Session One Notes exemplifies.

Athletes just want to play, just like artists want to create, and academics want to learn, it comes from within. It is also a way to forget about every other stress in your life and just be absorbed in the moment, which is why to suddenly find that other disabled people have an issue with you doing it [sport], doesn’t seem to make any sense to them.

Over the four sessions, the Group also took a systemic viewpoint to how disabled athletes and 'non-sports' artists differed in terms of their ‘activism’. They felt that when Para athletes do speak out publicly about discrimination or marginalisation, it is often framed as an individualistic act in comparison to artists who see their activism as part of a wider collective. They reasoned those disabled athletes, overall, viewed disabling barriers as a personal issue and something that they had to make compromises about or learn to tolerate as an individual (see, Reeve [Citation2014] on internalised oppression and Thomas [Citation2014] on disabling barriers). The Group connected this attitude to how the structure of the Paralympic Movement is couched in rehabilitative terms, disability labels, competition and a Medical/Individual Model discourse that views disability as something to be overcome. In contrast, they felt disabled artists/activists largely saw each disabling barrier as a systemic problem and worked with others to challenge and remove each barrier for the good of everyone. As Beddard (Citation2012) said, artists see a world constructed of barriers, prejudice and exclusion as stimuli to create work and therefore embrace disability as a central tenet of identity and creativity.

Action - tear down the wall of manipulation

Project Group Spirit also spent considerable time coming up with ideas for athletes and artists to engage in activism together. They felt this ‘us and them’ paradigm (Beddard Citation2012) was a result of structural manipulation. One suggestion was that Para athletes and practitioners (coaches, leaders) should undergo Disability Equality Training (DET) that is led and delivered by disabled professionals rather than disability awareness training that is often facilitated by non-disabled people. They also suggested creating an anonymous/safe space in which disabled athletes can share their experiences of being faced with barriers. Creating a short film/animation that shows the commonality rather than the differences that exist between the two groups would also help, the group felt. Linked to this, another idea was to try and identify common issues like stereotypes perpetuated in the media, improving access to transport or accessible accommodation.

A cartoon of a group of disabled athletes and disabled artists on either side of a broken down wall called the ‘Wall of Media Manipulation’ The artists are saying to the athletes “what to you say we start fighting them together”.

”Is it worth it?”: Engaging with WeThe15

This second theme is about the Group’s concerns about the WeThe15 campaign and whether or not it was worth it to give their support to this top-down initiative. To shift power relations, the Group decided to promote the practice of reciprocity and mutuality (Beresford Citation2021, Smith et al. Citation2022).

The Group’s primary concern was about the involvement of disabled people in the WeThe15 decision-making process. This concern was mainly around their perception that many of the organisations involved with WeThe15 were managed by non-disabled people. This, they said, had significant negative connotations, as the apparent similarity between the WeThe15 initiatives and those disability charities who, whilst claiming to represent disabled people, actually had very little representation of disabled people at the top (Clifford Citation2020). Those disabled people who are involved are often tokenistic and being used for photo opportunities. As this extract from the Zoom Session Two Notes exemplifies.

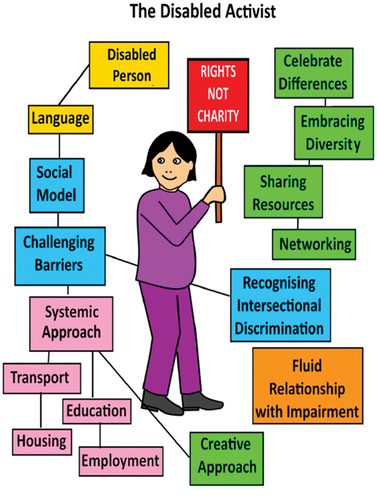

A cartoon of a diverse group of disabled activists at the WeThe15 launch saying “So why is there no mention of any groups & organisations of disabled people benign involved”?

As with similar organisations, the only disabled people visible on their social/media platforms seem to be those ‘Token Crips’ assembled for a feel-good photo opportunity. There is no mention of disabled people being involved in anything meaningful in the WeThe15 campaign, nor whether or not they have been involved in setting the agenda.

Another significant concern was the language used by WeThe15 on social media that indicated they want to make changes FOR disabled people rather than campaigning in a way that supports disabled people to make these changes for themselves. A further major concern was that some of the funding for the disabled sports community within the UK had come from Atos who, the Group claimed, had been instrumental in the deaths of thousands of disabled benefits claimants due to their aggressive assessment process (see, Braye [Citation2017]; Brittain and Beacom [Citation2016]; Clifford [Citation2020] on the relationship between Atos, the IPC and the UK Disabled Peoples Movement). The Group felt that the continued funding of the IPC by Atos would be unacceptable to many disabled people in the UK. Overall, however, the main criticism from the Group of the Wethe15 campaign was its lack of transparency. All the members found it difficult to obtain information about how the campaign was run, how it had arrived at its aims and objectives, in what capacity were disabled people involved and who was setting the agenda.

A cartoon of a wheelchair user graffiti artist spraying “sponsorship = profit = cuts” on ‘Paralympics 2012 sponsored by aTos’ billboard.

Action – promoting the practice of reciprocity and mutuality

The Group went on to consider if it was ‘worth it’ for them to engage with or support the WeThe15 initiative. On the one hand, the Group felt that if they offered their support to WeThe15 there was the danger of having their activist ideas hijacked in order to legitimise WeThe15’s actions. The Group felt that their involvement could offer WeThe15 a ‘cloak of respectability’ at their expense, as was often the case when disabled activists/artists became involved with similar ‘top-down’ initiatives. However, it was agreed that these initiatives were not going to go away and that grassroots activists had the choice of standing on the side lines (and watch as initiatives like WeThe15 vacuumed up funding) or finding a way to share resources.

With an aim to work towards the mutual benefit of grassroots activists and top-down initiatives, after Zoom Session Three, Project Group Spirit members compiled a list of specific questions to potentially ask of WeThe15, such as:

Are WeThe15 aware that many disabled people involved in activism and campaigning in the UK have a negative perception of their campaign?

Are the people running WeThe15 aware of the differences between those disabled people involved in sport and those not, and what impact this will have on their respective involvement?

People involved with WeThe15 must be aware of just how strongly disabled people in the UK feel about Atos. Why has not this ever been addressed?

Are WeThe15 willing to pay disabled people for their services rather than continuing to exploit the expectation that disabled people do not charge for their time or expertise?

Where has this money come from to develop WeThe15, and are disabled people involved in this process?

“We’re right and here’s why you should agree with us”: the moral high ground

The final action-orientated theme involved the Group members reflecting on how they come from a similar ethical or political viewpoint. To shift power relations, they decided to find ways to address and broaden their representation. The Group felt the Social Model understanding of disability, as developed in the UK (Barnes Citation2007, Griffiths Citation2022a, Citation2022b), was fundamental to their ethics and politics, as this extract from Zoom Session Four Notes highlighted.

If WeThe15 are suggesting that they are building the campaign around the Social Model understanding of disability, then the only place that they could obtain the necessary expertise and guidance would be from the UK disabled people’s movement. This is where the Social Model understanding not only originated but is continually being updated to match a changing society.

Their first reflection concerned language. Project Group Spirit members used Social Model language of disability as an important factor when evaluating if top-down initiatives are genuine and accessible. This meant the term ‘disabled people’ is a political term used to emphasise social oppression and nature of the discrimination that disabled people face on a daily basis (Oliver Citation2013). In contrast, they felt that the term ‘persons with disabilities’, as used by WeThe15 campaign, means ethically and politically opposite Medical/Individual Model language. However, the Group acknowledged that focusing too much on the disability language used can take attention away from positive impacts that top-down organisations and initiatives are making towards inclusion. One compromise suggestion made was that WeThe15 (and other similar groups) should be encouraged to change their language just a little bit initially, for example, referring to disabled people as ‘people with disabilities/disabled people’, similar to some ‘Deaf/deaf’ campaigns.

The second related reflection involved disability politics. The possibility was raised that because members of the Group all come from the same unchallenged UK Social Model viewpoint, it could be argued that they are trying to impose their own way of thinking on others. For example, the Group reasoned that most disabled athletes are not necessarily politically aware and, like the vast majority of people, are not involved in politics. The Group also agreed that there would be a danger of activists, like themselves, being seen to be taking the moral high ground and attempting to change, e.g., athletes into something more resembling themselves. They felt that trying to ‘fix’ non-politicised disabled people in a ‘we’re right and here’s why you should agree with us’ sort of way had a ring of Medical/Individual Model about it (i.e. fixing the individual).

A cartoon of two people on top of a hill called the ‘moral high ground’ saying “Agree With Us” and “We’re Right”.

Action – include a broader representation of disabled people

During the final Project Group Spirit meetings, the members realised that to actually make a difference, there needed to be input from other viewpoints and backgrounds (e.g. younger, high-profile, active Paralympians). They felt their right to continue discussing these issues was challenged without the involvement of disabled people who are not politicised or have any awareness of the UK Social Model understanding of disability. In line with the emancipatory and organic approach to this project, the Group decided that they wanted to continue working on these issues in a more meaningful way, gain more interest and credibility, establish a structure grounded in core principles, but remain organic and open to change. Accordingly, the Group members decided the outcome of Project Group Spirit was to use the discussions as a foundation to establish the, more structured, Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group).

Disability Knowledge Exchange and Impact Group (KEI Group): an activist network

The KEI Group was established as a result of a continuous process of reasoning and hermeneutics, which brought together the events of Project Group Spirit and subsequent activities, and the knowledge, resources and experiences of all involved.

At this stage Author A had become a collaborator in the emancipatory project and Author B (a disabled academic and activist), along with new members, joined the project too. As a group, we originally thought of the KEI Group as an advisory board to inform academic research, but that seemed a bit passive and beholden to a university. We then toyed with the idea of a ‘think tank’, however, to address power relations we then decided on an initial framework for the KEI Group. Importantly, we continued to make sense of how the KEI Group was forming through multiple and entangled layers of reflexivity between us, as academics, non-academics and activists.

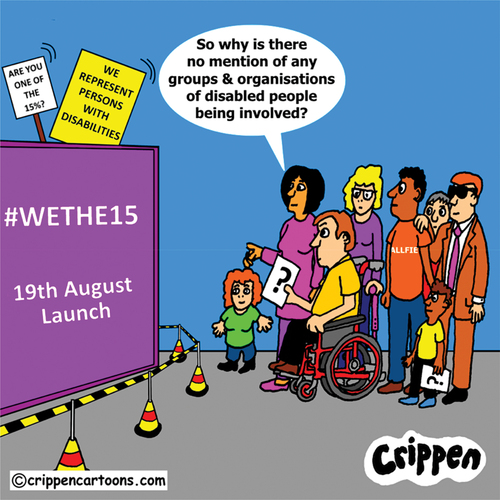

Through co-creating a term of reference, which was organic in nature, we decided that the KEI Group should be run within the context of the disabled people’s movement watchword – ‘nothing about us, without us!’ (Barnes Citation2007). This meant where possible all key roles to be undertaken by those disabled people who possess the necessary experience and expertise, with support provided by colleagues. Also, that those disabled people involved will always be remunerated for their involvement. We agreed the KEI Group should seek to include a broad representation of disabled people. Membership should aim to be diverse in terms of gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationality, age, class and access requirements (e.g. for different impairment experiences). It should also aim to include disabled activists who have expertise in broad areas such as social policy, human rights, media, academia, sports, arts, advocacy and campaigning. Also, addressing the ‘moral high ground’ problem, we decided the KEI Group should aim to include disabled activists and advocates that differ in their underpinning philosophies and preferred strategies to advocate for social change. This means including non-politicised disabled people, and disabled activists who have more radical tendencies as well as those with more reformist inclinations.

In terms of power dynamics, we came to an agreement that the KEI Group structure should involve 1) ‘the facilitator’ (Author C) from the disabled people’s community to organise the exchange of knowledge (e.g. monthly meetings) and to dictate the direction of impact following consultation with other members. 2) ‘the administrator’ (Author A) from the academic community to manage the day-to-day running of the group and to act as a conduit of knowledge to relative academic audiences such as academic funders and journals. 3)‘the core collaborators’ from the original Project Group Spirit including new disabled members such as active Paralympians, who inform/dictate the direction of knowledge exchanges. 4) ‘the ad-hoc collaborators’ (e.g. Author B and other new members) from the disabled people's community and allies, who are brought into the group from the ‘peripheries’ in appropriate ways for meaningful reasons.

We decided that the purpose of the KEI Group was to coordinate wide networks of disabled people who have the necessary expertise and experience to work on/input on various ‘KEI projects’ in the context of sport, disability and social activism. As noted, the Project Group Spirit action-orientated themes became the foundations for these projects. KEI projects involved exchanging knowledge, publicising the group and building capacity by seeking more funding and support. For example, between Jan 2022 and Nov 2022, the KEI Group networked, consulted and exchanged knowledge with multiple sport and disability organisations, academic groups and individuals, both nationally and internationally. In another example, over two half-days in July 2022, the KEI Group facilitated two Knowledge Exchange Forums which included approximately 20 individual disabled people (Paralympians, artists, activists, advocates and academics) who were connected to sport and disability organisations. Workshop 1 addressed the following question: ‘What are the benefits of disabled athletes becoming more involved in activism and protest in the UK?’ Workshop 2 addressed the following question: ‘What are the benefits of disabled people in the UK becoming more involved in the WeThe15 Campaign?’ Adhering to our principle that emancipatory research must produce knowledge that is useful for disabled people’s movements, the findings of these workshops were disseminated in plain English to the activists involved and/or the DDPOs they were connected to (in contrast to an academic audience).

A cartoon of the KEI Group depicted as a toolbox full of ideas and concepts necessary to promote the social and political emancipation of disabled people.

Finally, concerning the connection between universities and academic research and the KEI Group, we determined the KEI Group should remain as an independent, autonomous and public group that can act as a resource for universities and researchers in a number of ways; for example, academic researchers that wish to co-produce equitable and experientially informed research with disabled people, their groups and organisations. At the same time, universities and academic researchers can be a resource for the KEI Group, by providing access to networks (e.g. top-down organisations) resources (e.g. research skills, spaces, funding, time) and knowledge (e.g. academic research).

Addressing academic barriers to adopting the emancipatory approach

As we have shown, shifting power relations through an emancipatory approach to research can deliver multiple benefits, but we also encountered challenges and barriers throughout our projects. Many of these, we found, were embedded within neoliberal and elitist university systems and structures (Dolmage Citation2017, Smith et al. Citation2022). We argue that many of these challenges stemmed from what we term a confused model understanding of disability. Let us explain.

As disability is becoming more of a social justice issue in academic research (like gender and race), more ‘non-disabled’ scholars are becoming attracted to do research in the area of disability activism (Berghs et al. Citation2020). This development, coupled with a growing trend for interdisciplinary approaches to research projects (i.e. multiple academics looking at the ‘problem’ of disability through different theoretical lenses) can create a theoretical and practical challenge to promoting emancipatory approaches. The ever-present potential danger of this scenario is a situation in which scholars who do not necessarily have a research background in disability studies or lived experience of disability hold significant power in the research processes.

Although critical disability studies scholars advocate strongly for the benefit of interdisciplinary approaches to disability research (Goodley Citation2016, Shildrick Citation2012), there is a danger that key underpinning principles of disability studies can get lost in new ambitious projects. For example, a Social Model understanding of disability can become viewed as just one of many theoretical lenses by academics involved in projects. This is a challenge because a Social Model understanding of disability (e.g. the principle of doing research to provide information with which disabled people can empower themselves) is a way of thinking that is foundational and core by many disability studies scholars and disability activists (Goodley Citation2016). We argue this can create a confused model of disability if/when research projects present a confused understanding of disability, meaning it can be unclear if researchers and research designs are trying to fix (Medical/Individual Model understanding) or save disabled people (Charity Model understanding), or understand oppression and marginalisation through social world organisation (Social Model understanding, see Smith and Bundon Citation2018). We found this confused understanding of disability created a number of academic barriers to fully adopting the emancipatory approach.

One associated barrier concerned securing adequate resourcing for our emancipatory research. As mentioned, one of the key principles of Project Group Spirit and the KEI Group is that disabled people involved were remunerated for their participation. Moreover, our approach placed a value on how the project should develop in an organic and unforced grassroots nature. However, we found funding applications through academic systems often require research questions, designs, costings and outcomes to be set before funding can be awarded. Moreover, neoliberal academic structures tend to award funding to individual academics to benefit their individual careers rather than to emancipatory projects that can help disabled people and disability communities empower themselves. Related to this, another challenge we encountered was the difficulty of individual early career academics on short-term contracts trying to secure funding for such emancipatory projects that are necessarily long term.

Another major challenge involved trying to persuade the value of an emancipatory approach ‘upwards’ within academic hierarchies. As Smith et al. (Citation2022) said, due to structural inequalities in academia, those who carry-out this kind of work occupy less prestigious academic positions. Although our emancipatory research had clear benefits, such as addressing power inequalities in research and amplifying marginalised voices, we encountered several barriers while trying to convince senior academics about this approach. One barrier was that senior academics perceived that emancipatory research would cost more in time and money than traditional approaches. However, we found and argued that this approach is relatively inexpensive when compared to international research collaborations, and remuneration costs for lived experience and expertise are negligible in comparison to research staff costs.

We do not have solutions to all these academic barriers, but we suggest that it might be helpful for scholars in the field to consider ways to address and rethink what Lau (Citation2019) described as the ‘academic culture of speed’. We encourage scholars to think how the persistent and consistent desire for outputs in academic structures can contribute to disablement rather than emancipation. Think about how early-career academics can be discouraged from engaging in emancipatory projects due to mounting demands for productivity. Think about whether big research spends with ambitious goals, which are controlled through hierarchies of knowing/knowledge in universities, can really improve the lives of disabled participants or their communities. Advocate, we suggest, for ‘slow scholarship’ to do research that allows time for building relationships and foundational work in disability research projects, as this can help to disrupt rigid structures of academic labour (Lau Citation2019).

How might emancipatory approaches be judged in terms of research quality?

From our experiences on this project, we encourage academics and activists to think about how to judge the quality of emancipatory participatory approaches like this (Haslett Citation2023, Liddiard et al. Citation2019, Powis et al. Citation2023). To help foster high-quality research going forward, here are some critical questions that others may wish to consider, focused on the ability of projects to enable disabled people to empower themselves in the short and long terms.

Ask questions about who is really benefiting in the long term. Although this project had ambitions to give control to disabled activists in the production of research, it could be legitimately argued that this ‘emancipatory approach’ just mitigated problems with ‘traditional approaches’ that will still gain more attention in the long term.

Does the research project produce knowledge that benefits disabled peoples’ movements? While this article is written for an academic audience, it is just one of many outputs that went to grassroots activists in different formats.

Consider if power relations have really shifted at all. While our attempt was to shift power relations, this project took place within wider complicated power dynamics involving conflicting interests and motivations coming from activists, academics, project managers, DDPOs, disabled people who work in sport, academic strategists, as well as international sport and disability organisations.

Related to this, ask questions about how projects can deal with conflict and distrust if/when it arises. We experienced some conflict in this project in part because our ambitions outweighed our resources. For example, after an engaging year, some activists felt they were abandoned in favour of other relationships when funding and university support expired.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have shown how adopting an emancipatory paradigm can shift power relations in the production of research and create significant learnings and impact. A group of non-academic disabled activists worked on a small project that laid the foundations to develop a larger structured project to exchange knowledge on sport, disability and activism. Emancipatory projects like this are needed to shine an important light on whose knowledge has been missing from the production of research in disability sport studies, why there is a need to address power dynamics and how to do it (Haslett Citation2023, Spencer and Molnár Citation2022).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Damian Haslett

Damian Haslett’s research has explored disability sport and social change. One example of this focus is his research on Para athletes as ‘social activists/advocates’ that has been published in several edited books and academic journals. Damian has worked on a variety of projects in and around Paralympic sport including research underpinned by emancipatory participatory principles and practices.

Miro Griffiths

Dr Miro Griffiths is a Disability Studies scholar, based in the School of Sociology and Social Policy, at the University of Leeds. His research is associated – primarily – with understanding disabled people’s experiences of resistance, activism, social movement participation, and advocacy. His contribution to existing bodies of literature has progressed ideas and theories about power, resistance practices, and disabled people’s pursuit for liberation.

Dave Lupton

Dave Lupton aka Crippen - Disabled Cartoonist has been an active member of the UK Disabled People's movement for over 40 years. He is currently working on updating the grey scale cartoons he created in the 1980's and 90's. Dave also works as an access auditor, disability equality consultant, trainer, and facilitator, is an editor with Disability Arts Online (DAO) and an Executive member of the Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People (GMCDP). He has also been Chair of the National Union of Journalists Disabled Members Council and Editor of the TUDA News, the magazine of the Trades Union Disability Alliance (TUDA) and Disability Arts Magazine (DAM). Dave now lives on the Isle of Wight.

Notes

1. The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) launched the WeThe15 campaign at the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games (held in August 2021). WeThe15 was self-described as sport’s biggest ever human rights movement to end discrimination. Their aim was to transform the lives of the world’s 1.2 billion ‘persons with disabilities’ who represent 15% of the global population (see https://www.wethe15.org/).

References

- Barnes, Colin. 1996. “Disability and the Myth of the Independent Researcher.” Disability & Society 11 (1): 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599650023362.

- Barnes, Colin. 2002. “‘Emancipatory Disability research’: Project or Process?” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 2 (1): no–no. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2002.00157.x.

- Barnes, Colin. 2007. “Disability Activism and the Struggle for Change: Disability, Policy and Politics in the UK.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 2 (3): 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197907081259.

- Beddard, Jamie. 2012. “The Race to Mainstream Acceptance”. In Cultural Shifts:A Collection of Essays About Disability, Success, Art, Sport and the Influence of the London 2012 Paralympic Games. Edited by Camilla Brueton and Esther Fox. An Accentuate Publication.

- Beresford, Peter. 2021. Participatory Ideology: From Exclusion to Involvement. Policy Press.

- Berghs, Maria, Tsitsi Chataika, Yahya El-Lahib, Kudakwashe Dube, M. Berghs, T. Chataika, Y. El-Lahib, and K. Dube. 2020. The Routledge Handbook of Disability Activism. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351165082.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braye, Stuart. 2016. ““‘I’m Not an activist’: An Exploratory Investigation into Retired British Paralympic athletes’ Views on the Relationship Between the Paralympic Games and Disability Equality in the United Kingdom.” Disability & Society 31 (9): 1288–1300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1251392.

- Braye, Stuart. 2017. ““You Shall Not murder”: Atos at the Paralympic Games.” Journal of Disability & Religion 21 (2): 215–229.

- Braye, Stuart, Kevin Dixon, and Tom Gibbons. 2013. “‘A Mockery of equality’: An Exploratory Investigation into Disabled activists’ Views of the Paralympic Games.” Disability & Society 28 (7): 984–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.748648.

- Brittain, Ian, and Aaron Beacom. 2016. “Leveraging the London 2012 Paralympic Games: What Legacy for Disabled People?” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 40 (6): 499–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516655580.

- Choi, Inhyang, Damian Haslett, and Brett Smith. 2019. “Disabled Athlete Activism in South Korea: A Mixed-Method Study.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19 (4): 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1674903.

- Clifford, Ellen. 2020. The War on Disabled People: Capitalism, Welfare and the Making of a Human Catastrophe. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350225732.

- Dolmage, Jay. 2017. Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. University of Michigan Press.

- Fitzgerald, Hayley. 2009. “Are You a ‘Parasite’ Researcher? Researching Disability and Youth Sport.” In Disability and Youth Sport, edited by Hayley Fitzgerald, 157–171. New York: Routledge.

- Goodley, Dan. 2016. Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. London: Sage.

- Goodley, Dan, and Michele Moore. 2000. “Doing disability research: Activist lives and the academy.” Disability & Society 15 (6): 861–882.

- Griffiths, Miro. 2022a. “Disabled Youth Participation within Activism and Social Movement Bases: An Empirical Investigation of the UK Disabled People’s Movement.” Current Sociology 001139212211005. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921221100579.

- Griffiths, Miro. 2022b. “UK Social Model of Disability and the Quest for Emancipation.” In Handbook of Disability, edited by Marcia Rioux, Jose Viera, Alexis Buettgen, and Ezra Zubrow, 1–15. Singapore: Springer.

- Haslett, Damian. 2023. “Addressing Power Dynamics in Disability Sport Studies: Emancipatory Participatory Principles for Social Justice Research.” In Routledge Handbook of Sport, Leisure and Justice, edited by Stefan Lawrence, Rasul Mowatt, and Joanne Hill.

- Haslett, Damian, and Brett Smith. 2022. “Disability, Sport and Social Activism.” In Athlete Activism: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Rory Magrath, 65–76. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140290-7.

- Hughes, Brian. 2009. “Disability Activisms: Social Model Stalwarts and Biological Citizens.” Disability & Society 24 (6): 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590903160118.

- IPC. 2019. “International Paralympic Committee Strategic Plan 2019 to 2022.” https://www.paralympic.org/

- Lau, Travis Chi Wing. 2019. “Slowness, Disability, and Academic Productivity: The Need to Rethink Academic Culture.” In Disability at the University: A Disabled Students’ Manifesto, edited by Peter Lang, 11–19. New York.

- Liddiard, Kirsty, Katherine Runswick‐Cole, Dan Goodley, Sally Whitney, Emma Vogelmann, and M. B. E. Lucy Watts. 2019. ““I Was Excited by the Idea of a Project That Focuses on Those Unasked questions” Co‐Producing Disability Research with Disabled Young People.” Children & Society 33 (2): 154–167.

- Macbeth, Jessica. 2010. “Reflecting on Disability Research in Sport and Leisure Settings.” Leisure Studies 29 (4): 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2010.523834.

- Magrath, Rory. 2022. Athlete Activism: Contemporary Perspectives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140290.

- McColl, Mary Ann, William Adair, Sue Davey, and Nick Kates. 2013. “The Learning Collaborative: An Approach to Emancipatory Research in Disability Studies.” Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 2 (1): 71–93. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v2i1.71.

- Mietola, Reetta, Sonja Miettinen, and Simo Vehmas. 2017. “Voiceless Subjects? Research Ethics and Persons with Profound Intellectual Disabilities.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20 (3): 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1287872.

- NIRH. 2020. “A Map of Resources for Co-Producing Research in Health and Social Care: A Guide for Researchers, Members of the Public and Health and Social Care Practitioners.” Version 1.2. https://arc-w.nihr.ac.uk/Wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Map-of-resources-Web-version-v1.2.pdf.

- NIRH. 2021. “Briefing Notes for Researchers – Public Involvement in NHS, Heath and Social Care Researcher.” In Retrieved: Briefing Notes for Researchers - Public Involvement in NHS, Health and Social Care Research. NIHR.

- Oliver, Mike. 1992. “Changing the Social Relations of Research Production?” Disability, Handicap & Society 7 (2): 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02674649266780141.

- Oliver, Mike. 2013. “The Social Model of Disability: Thirty Years on.” Disability & Society 28 (7): 1024–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773.

- Pappous, Athanasios, and Chris Brown. 2018. “Paralympic Legacies: A Critical Perspective.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies, edited by Ian Brittain and A. Beacom, 647–664. London: Palgrave Macmillian. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-47901-3_29.

- Peers, Danielle. 2018. “Sport and Social Movements by and for Disability and Deaf Communities: Important Differences in Self-Determination, Politicisation, and Activism.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies, edited by Ian Brittain and A. Beacom, 71–97. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-47901-3_5.

- Pinto, Paula Campos. 2019. “When Academia Meets Activism: The Place of Research in Struggles for Disability Rights.” In Global Perspectives on Disability Activism and Advocacy: Our Way, edited by Karen Soldatic and Kelley Johnson, 315–327. New York: Routledge.

- Powis, Ben, James Brighton, and P. David Howe. 2023. “Researching Disability Sport: Theory, Method, Practice”. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003153696.

- Rees, Leanne, Priscilla Robinson, and Nora Shields. 2019. “Media Portrayal of Elite Athletes with Disability - a Systematic Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation 41 (4): 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1397775.

- Reeve, Donna. 2014. “Psycho-Emotional Disablism and Internalised Oppression.” In Disabling Barriers - Enabling Environments, edited by John Swain, Colin Barnes, and Carol Thomas, 92–98. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Sharpe, Lesley, Janine Coates, and Carolynne Mason. 2022. “Participatory Research with Young People with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities: A Reflective Account.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 14 (3): 460–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1952297.

- Shildrick, Margrit. 2012. “Critical Disability Studies: Rethinking the Conventions for the Age of Postmodernity.” In Handbook to Disability Studies, edited by Nock Watson, Alan Roulstone, and Carol Thomas, 30–41. London: Routledge.

- Smith, Brett, and Andrea Bundon. 2018. “Disability Models: Explaining and Understanding Disability Sport in Different Ways.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies, edited by Ian Brittain and A. Beacom, 15–34. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-47901-3_2.

- Smith, Brett, Andrea Bundon, and Melanie Best. 2016. “Disability Sport and Activist Identities: A Qualitative Study of Narratives of Activism Among Elite Athletes with Impairment.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 26:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.07.003.

- Smith, Brett, Kerry R. McGannon, Mike Atkinson, and the Moving Social Work Co-production. Collective. 2023. “Advancing Participatory Approaches to Co-Production, Co-Design, and Community Based-Research in Sport, Exercise and Health: A Curated Collection of Contemporary Views.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 15 (2): 159–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2052946.

- Smith, Brett, Oli Williams, Lydia Bone, the Moving Social Work Co-production. Collective, and and the Moving Social Work Co-production Collective. 2022. “Co-Production: A Resource to Guide Co-Producing Research in the Sport, Exercise, and Health Sciences.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health 15 (2): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2052946.

- Soldatic, Karen, Kelley Johnson, K. Soldatic, and K. Johnson. 2019. Global Perspectives on Disability Activism and Advocacy: Our Way. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351237499.

- Spencer, Nancy, and Győző Molnár. 2022. “Whose Knowledge Counts? Examining Paradigmatic Trends in Adapted Physical Activity Research.” Quest 74 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2021.2021258.

- Stone, Emma, and Mark Priestley. 1996. “Parasites, Pawns and Partners: Disability Research and the Role of Non-Disabled Researchers.” The British Journal of Sociology 47 (4): 699–716. https://doi.org/10.2307/591081.

- Thomas, Carol. 2014. “Disability and Impairment.” In Disabling Barriers - Enabling Environments, edited by John Swain, Sally French, Colin Barnes, and Carol Thomas. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Zarb, Gerry. 1992. “On the Road to Damascus: First Steps Towards Changing the Relations of Disability Research Production.” Disability, Handicap & Society 7 (2): 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02674649266780161.