ABSTRACT

The aims of this review were to: 1) offer a comprehensive analysis of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences since the beginning of the 21st century, 2) enhance conceptual clarity and methodological rigour, and 3) identify new avenues of potential narrative exploration. Following an extensive search across two databases (i.e. Sportdiscus and Psychinfo) and a targeted manual search, 77 research papers were used to provide an overview of narrative research, highlighting data collection and analysis methods, participants, findings, significant contributions, as well as the narrative themes and types. Our analytic process, drawing from the traditions of narrative analysis, showcased how narrative research has been conducted and its revelations in sport and exercise sciences. The analysis uncovered that 51 articles had aims in three primary areas: 1) meaning and identity construction, 2) disability and/or impairment, and 3) athletic career pathways and/or in-career transitions. Additionally, 51 articles identified narrative types, with the performance (N = 26), relational (N = 12), and restitution (N = 8) types appearing most frequently. While this review reveals commonalities linking narrative research in sport and exercise sciences, many gaps and future challenges were also identified. Primarily, we recommend that narrative researchers: 1) be more consistent in their language to prevent confusion and misunderstandings, 2) differentiate between narratives and stories more clearly, 3) analyse the content and/or structure of stories, 4) expand research on exercise, health, and physical activity, 5) include participants from diverse cultural and non-Western contexts, 6) explore narrative characters, and 7) investigate the performance narrative type in applied settings.

Researchers engaging with narrative inquiry as a form of qualitative research have become more common within sport and exercise sciences. For instance, 19% (13 out of 69) of all published articles in the journal of Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health in 2022 were identified as incorporating a narrative approach. Within these studies, the topics varied widely with researchers exploring issues such as elite talent in sport and arts (John and Thiel Citation2022), racism (Keaton Citation2022), disability in sport and physical activity (Lowry et al. Citation2022; Williams, Lozano-Sufrategui, and Tomasone Citation2022), gender (Darpatova-Hruzewicz Citation2022; Graham and Blackett Citation2022), and trauma (Whitley et al. Citation2022). Consequently, as researchers continue to utilise narrative analysis as a form of meaning-making, a review of the field since its ascendency is overdue. Below, we briefly outline narrative as a form of inquiry, present an overview of the landscape of narrative analysis in sport and exercise through the overview of eight review-type papers, and then proceed with defining the scope, type, and aims of this review.

Narrative as a form of inquiry

Humans are storytellers, and as far as we can tell, this has always been so. For example, there are illustrations of cave art from the Palaeolithic era, ‘imbued with narrative content [that] display complex literary features such as composition, juxtaposition, association and scene’ (Papathomas Citation2016, 38). This historical connection to the human capacity and propensity for story telling is highly important because narrative researchers believe that stories are actors, they do things, and ‘narratives play a key part in constituting meaning [and] making sense of our experiences’ (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009a, 280). This interest in stories, and the subsequent understanding of the narratives that hold them together, began to take shape at the beginning of the 20th century with Thomas and Znaniecki’s (Citation1918) sociological studies on Polish immigrants. Labov and Waletzky (Citation1967) then offered a more formalised approach to narrative inquiry, while the ‘narrative turn’ opened a new door of possibilities within the field (Bruner Citation1986; A. W. Frank Citation1995; Gergen and Gergen Citation1986; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998). Yet, as the field of narrative research has developed and evolved, there does remain a lack of clarity concerning the methodological process and definitional boundaries, challenging the coherence and generalisability of findings. At the same time, there are indeed many elements that hold narrative research together; first and foremost, it is the focus and interest in stories.

Primarily, narrative researchers are interested in: 1) the stories people tell, and 2) the broader narrative structures available in which these stories are shaped and moulded. Importantly, there are no shortage of definitions and interpretations concerning what comprises a story or a narrative (for an overview see Monforte and Smith Citation2023), so for the purpose of this review paper we suggest the following. First, a story is a tale that has a sequence, coherence, a discernable consequence, and is further aided by the human imagination (A. W. Frank Citation2010; Gergen and Gergen Citation1986; B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009a). Stories are usually consistent in how they unfold, the listener can follow the events until the conclusion, and a storyteller crafts each tale within the recesses of their own mind. Second, according to Frank (Citation2010), stories refer to the actual tales people tell while the term narrative is used to describe the dimensions of a story or stories that hold them together. ‘People tell stories, not narratives’ (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009b, 2), and Frank (Citation2013) proposed that a narrative is, ‘the most general storyline that can be recognized underlying the plot and tensions of particular stories’ (p. 75). As Papathomas (Citation2016) suggests, ‘where there is an identifiable genre, plot and character, there is usually a narrative’ (p. 40). Finally, Monforte and Smith (Citation2023) point out that while ‘stories are unique and individual, people compose their stories by adapting and combining the narratives that cultures make available’ (p. 110).

Narrative research within sport and exercise sciences

Narrative analysis first appeared in sport and exercise literature via Smith and Sparkes’ (Citation2002, Citation2004; Sparkes and Smith Citation2003, 2005) studies about men who acquired spinal cord injuries through sport. Within these investigations, the authors brought attention to three narrative types (e.g. chaos, restitution, and quest) that the men used to construct their life stories. For example, within the restitution narrative type, the men were able-bodied, now they are disabled, and strive to be able-bodied once again. Crucially, narratives are not stagnant entities, they are ‘actors … and can do things on, in, and with us’ (B. Smith Citation2016, 261). Meaning, if a restitution narrative is guiding a disabled person’s life, what happens to that life when the impairment will remain chronic (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2011)? Notably, narrative types are accessible and applicable to others and these three narrative types have been utilised and expanded by researchers investigating physical activity amongst wounded military veterans (Carless Citation2014; Evans, Andreassen, and Virklund Citation2020), body perceptions of women engaging in yoga (Leledaki Citation2014), or growth-related experiences in Olympic swimmers (Howells and Fletcher Citation2015).

Following the initial work of Sparkes and Smith, the next notable contribution within the field was the identification of the performance narrative (Carless and Douglas Citation2009; Douglas and Carless Citation2006) amongst professional female golfers. Within this narrative type, the researchers suggested that ‘being competitive is storied as “natural”, … winning is prioritized to the extent that discipline, sacrifice and pain are accepted in the pursuit of glory, and failure is accompanied by feelings of shame’ (Carless and Douglas Citation2009, 54). The performance narrative has become prominent since its introduction in sport and exercise, in part, because it makes sense; it is logical, available, and resonates with high performing athletes and relevant culture. Furthermore, it has driven researchers to explore the implications of this narrative in athletes’ lives, how it contributed to their successes, but also the career implications following retirement or severe injury. To date, researchers have explored the repercussions of the performance narrative in studies including Olympic and Paralympic athletes (Trainor et al. Citation2023), handball (Ekengren et al. Citation2019) and tennis (Alina Franck & Natalia Stambulova, Citation2018) players, as well as endurance athletes suffering from eating disorders (Busanich, McGannon, and Schinke Citation2014; Papathomas and Lavallee Citation2014).

Existing review-type papers

To overview the narrative discourse in sport and exercise sciences, we used a methodical search (see methodology) to identify eight review-type papers and appraised them in terms of type, aim, and significant contributions. Among the eight review-type papers, of particular interest and importance are the methodological propositions concerning what constitutes narrative analysis and how it ‘could’ be done. As an umbrella term, narrative analysis takes stories and storytelling as a form of inquiry (Monforte and Smith Citation2023), and while the methodological process is inherently open and creative, the review-type papers were consistent in promoting several key features of narrative analysis, including, but not limited to: 1) a shared philosophical assumption (McGannon and Smith Citation2015; Papathomas Citation2016; B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009a), 2) the analytical perspective of the authors, and 3) the presentation of the findings. First, it is promoted that those conducting a narrative analysis adhere to an interpretivist paradigm, typically within the realms of ontological relativism and epistemological interpretivism. Narrative researchers are ‘interested in personal truth ahead of objective truth … [and] therefore seek out personal experience stories not in spite of subjectivity but because of their subjectivity’ (Papathomas Citation2016, 38). Second, narrative scholars will commonly analyse stories regarding ‘what’ was said (i.e. the content, narrative themes, etc.), ‘how’ it was said (i.e. story structure, plot, etc.), or both (see analytical bracketing, B. Smith Citation2016), and position themselves as storyanalysts or storytellers (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009a, Citation2009b). While both perspectives propose myriad techniques to engage with narratives, storyanalysts place narratives under analysis, but for storytellers, analysis is the story (Monforte and Smith Citation2023). Third, narrative research is generally presented differently than more traditional qualitative research, with storyanalysts telling a story through realist tales (often devoid of authorial presence) while storytellers use creative analytical practices and the story itself is both analytical and theoretical (Monforte and Smith Citation2023).

Scope, type, and aims of this review

Drawing from our analysis of eight review-type papers and our own insights into the narrative discourse within sport and exercise research, we delineate the scope, type, and aims of this review. As narrative inquiry has gradually gained interest over the past two decades, our focus naturally gravitated towards recent developments, especially considering the absence of a prior comprehensive assessment of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences. Consequently, we chose a state-of-the-art critical review approach (Grant and Booth Citation2009) informed by contemporary methodologies to fulfil our overarching aims of encapsulating the current landscape, identifying the most significant contributions, and charting pathways for future investigation. In summary, while the field of narrative research provides vast potential in sport and exercise research, the breadth of what has been done compels thoughtful consideration of the past, present, and future of narrative inquiry. Therefore, the aims of this review were threefold: 1) to offer a comprehensive analysis of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences since the beginning of the 21st century, 2) to enhance conceptual clarity and methodological rigour, and 3) to identify new avenues of potential narrative exploration.

Methodology

Review design

Our research paradigm and methodology are rooted in relativist (i.e. ontological) and interpretivist (i.e. epistemological) assumptions. In alignment with these philosophical perspectives, we employed a state-of-the-art critical review method as a framework to explore existing narrative research in sport and exercise sciences. This method aligns with our aims by prioritising current issues, narrative representation, a comprehensive literature search, and an emphasis on new perspectives and future research directions. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that our philosophical stance requires a deeper comprehension of methodology beyond specific techniques or procedural tools (Sparkes, Citation2015). Thus, we recognise the interpretive nature of data analysis and our subjective involvement in the research process, which inevitably influenced the outcomes.

Search strategy and identifying relevant papers

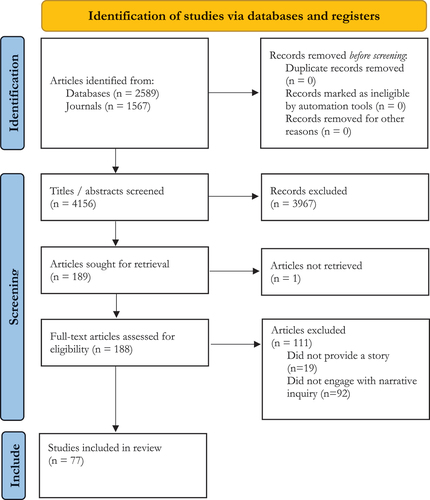

This review search strategy comprised two steps. Step one aimed to identify review-type papers to provide an overview of narrative research in sport and exercise science, while step two identified relevant papers for the study. In step one, a manual search was conducted via Google Scholar as well incorporating our own familiarity with narrative literature. As a result, we identified eight review-type papers (see ) representing the beginning, middle, and end of the designated period of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences. The search strategy in step two consisted of two primary rounds, followed suggestions from Grant and Booth (Citation2009), and encompassed an iterativeFootnote1 and integrative approach designed to comprehensively gather relevant studies and ensure inclusivity. During the first round (identification), peer-reviewed journal articles (in English) were sought after on the databases of Psychinfo and Sportdiscus. As the authors wanted to avoid excluding potentially relevant articles, the broadest possible keyword ‘narrative’ was used without any restriction to the year of publication. The search led to the identification of 4156 articles. In the second round (screening) abstracts were initially screened to gauge general eligibility (i.e. must be about sports and/or exercise and conduct a narrative analysis) which resulted in the exclusion of 3967 articles. Next, we employed a relativist lens while reading the remaining 188 full-text articles for study eligibility and prioritised the following three criteria (see Monforte and Smith Citation2023); 1) substantive contribution and worthiness (i.e. does the research contribute empirically, methodologically, theoretically, etc.), 2) meaningful coherence (i.e. uses methods and procedures that fits research questions and connects with literature, findings, and interpretations), and 3) focus (i.e. is the purpose and point to the research consistent). The final selection was laborious, time consuming, and inevitably subjective, and while not possible to impart the intricacies of this process to the reader, the following are examples of why a narrative article could have been excluded: 1) the researchers did not actually perform a narrative analysis, 2) narrative types, themes, and/or stories were not discussed, or 3) narrative discourse was not thoroughly engaged with. Ultimately, the final screening process excluded 111 articles, leaving a total of 77 articles included in the review (see and ). Finally, to ensure that relevant articles were not missed, we conducted a manual search (from 2002 to April 25th, 2024) of the 12 journals in which the total list of 77 articles was comprised, which added no new articles, and a kind of saturation was achieved.

Table 1. A brief summary of the identified review-type papers in sport and exercise sciences on narrative research (in a chronological order).

Table 2. Summary of narrative studies.

Bibliographical coding, appraisal, and analysis of included papers

All included articles were sorted alphabetically based on the first author’s and (if necessary) second author’s surname. Then, each article was assigned a biographical code (see ) which will be used (appears in square brackets) to differentiate between included review papers and other references. The articles were then full-text read to assess their aim(s), data collection and analysis methods, participants, findings (conceptual, empirical, practical), significant contributions, as well as the narrative themes and types. No formal research quality appraisal was conducted as all included articles were peer-reviewed in well-respected journals within the field, thus ensuring an inherent level of research quality (see e.g. Crossen et al. Citation2023). is the final outcome of our work, which we deem to be a representative overview of the designated period of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences. Next, to synthesise the data, the authors aimed to juxtapose the traditions of state-of-the-art critical reviews (see e.g. Stambulova and Wylleman Citation2019) with the conventions and historical roots of narrative inquiry. Therefore, it was fitting to use the perspective that narrative inquiry has made available to us by analysing the ‘whats’ and ‘hows’ of the articles included in this review. With this in mind, we engaged in a comprehensive and iterative coding process, meticulously examining each article to identify prevalent themes, features, characteristics, and common topics. This involved detailed hand-coding and pattern recognition, and was supported by thematic (see B. Smith Citation2016) and structural (see Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998) narrative analytic principles, to draw out significant insights and trends within the literature. Through this methodical approach, the authors were able to synthesise the data and provide a nuanced overview of the narrative research landscape in sport and exercise sciences.

Findings

Below we have arranged the findings into three sections; 1) the landscape of narrative research in sport and exercise science, 2) ‘how’ has narrative research been done, and 3) ‘what’ has narrative inquiry explored and revealed in sport and exercise sciences. The findings are organised to showcase the current topography of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences as well as highlighting research gaps and future challenges.

The landscape of narrative research in sport and exercise science

Our holistic analysis of form revealed that the last two decades of narrative research depicted a structure comparable to a progressive narrative type, or more specifically, a progression of slow ascension (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998). Between 2002 and 2012 only 10 articles were published. However, beginning in 2012, the prevalence of narrative articles began to trend upwards, culminating in a steep curve since 2018 whereby 56% (N = 43) of the papers in this study were published. In examining the rise of narrative inquiry in sport and exercise sciences, it is pertinent to understand researchers’ motivations. As such, when scrutinising research purpose, our analysis identified that narrative inquiry is valued for its inherent openness and reflexivity, rendering it particularly conducive to the exploration of topics revolving around life experiences (N = 27), identity construction (N = 14), and meaning (N = 7). Notably, 49% (N = 38) of research teams identified themselves as explorers, while 21% (N = 16) sought deeper comprehension. In contrast, a scant few adopted more post-positivistic language, such as analysing (N = 1) or comparing and contrasting (N = 1). While word choice is of course highly subjective, the shared language which underpins narrative researchers’ aims is noteworthy. Further, this common language speaks directly to the shared paradigm in which narrative researchers almost exclusively operated, as all included studies were either specifically positioned within ontological relativism and epistemological interpretivism or could be inferred as such if not directly stated. Finally, the cultural context in which research projects are situated will undoubtedly influence the perspectives and the research topics explored. Consequently, it is relevant to know where narrative researchers and study participants were geographically (and culturally) based. Considering that the roots of narrative inquiry developed in the United Kingdom [10, 13, 63, 64, 68, 69], it is perhaps unsurprising that 40% (N = 31) of the studies took place there. In total, 10 different countries were represented in this review, with 19 studies taking place in North America (12 Canada, 7 USA), 13 in continental Europe, and nine comprising multiple countries.

“How” has narrative research been done

Narrative research is a time-intensive process in terms of data collection and analysis; therefore, the sample sizes are understandably small. Further, considering that researchers who utilise narrative inquiry are prioritising personal truth over objective truth, a small number of participants is not only desirable, but arguably necessary. For the 77 studies, the mean was 11.1, median 5, and mode 2, while further subdivision of included participants highlighted that 32% (N = 25) of all studies had two or fewer participants, only five studies [46, 52, 65, 70, 72] included more than 30 participants, and 13 studies exclusively targeted females. To collect data, all but 10 research teams used interviews, either semi-structured (N = 33), life-story/history (N = 16), conversational (N = 6), visually aided/art-based (N = 9), or narrative-type (N = 3). In addition to interviews, some researchers incorporated other data collection methods such as observations (N = 5), questionnaires/surveys (N = 3), or biographical mapping (N = 2). For the 10 included studies not based on interviews, five [33, 35, 36, 37, 62, 66] analysed autobiographies, two [38, 39] examined digital sources, one [20] used letter writing, and one [42] used poems and short stories.

While placing stories and storytelling as the object of enquiry is what broadly separates

narrative analysis from other qualitative methods, there are many ways that researchers can conduct a narrative analysis. A common starting point was for researchers to identify themselves as either storytellers and/or storyanalysts and explore their data concerning what was said (i.e. content) and/or how the participants said it (i.e. structure). However, even though not all studies explicitly stated a position,Footnote2 our investigation deduced that 62 of the studies took a storyanalyst perspective 10 were storytellers, and five used both perspectives. To analyse and interpret the data, narrative researchers drew upon a variety of tools made available to them during the last two decades, and while is not an exhaustive list, it does speak to the diversity of this method. Thematic narrative analysis (N = 26) was the most frequently used analytic lens, followed by structural analysis (N = 17), creative non-fiction (N = 13), dialogical narrative analysis (N = 11), holistic analysis of form/holistic form structural analysis/holistic form analysis (N = 8), and content analysis/holistic content analysis/categorical content analysis (N = 10). Further, it was common (N = 24) for authors to apply more than one approach when analysing data (i.e. bracketing), for instance combining content and structural analysis together [e.g. 2, 3, 7, 43]. Within the reviewed articles, researchers frequently identified narrative themes (N = 17), narrative types (N = 30), or both (N = 21), while nine articles did not specify either narrative themes or narrative types. However, seven of the articles not specifying narrative themes or types were presented from a storyteller perspective, where analysis ‘is’ the story, and the representation differs significantly from that of realist tales. Of the 62 articles deemed to use a storyanalyst position, 12 articles identified narrative themes, 30 identified narrative types, 18 of the articles discussed both, while two articles did not identify narrative themes or types of narratives. Finally, when representing the findings, realist tales were used in 73% of the articles (N = 56), while the remaining 21 articles used a variety of creative analytical practices.

“What” has narrative inquiry explored and revealed in sport and exercise sciences

Within the 77 narrative studies, 15 focused on exercise, health, and/or physical activity, while 61 were sport related (with 16 being elite sport). Moreover, deeper analysis highlighted that 51 of the included articles had aims categorised within three areas: 1) meaning and identity construction [1, 6, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, 18, 24, 27, 37, 38, 44, 47, 48, 51, 56, 61], 2) disability and/or impairment [1, 13, 14, 17, 20, 31, 50, 52, 63, 64, 65, 67, 69, 75, 77], and 3) athletic career pathways and/or in-career transitions [7, 10, 15, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30, 39, 51, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60]. Other key research foci in this review appearing more than three times included children and/or youth [3, 11, 19, 50, 57, 72, 74], pain/injury [20, 24, 39, 70, 71, 76], disordered eating [8, 9, 33, 40, 43], and coach/athlete relationships [3, 19, 42, 67]. Researchers engaging with narrative inquiry have made significant contributions to sport and exercise sciences, and our examination highlighted the depth and breadth of what is possible when researchers listen, analyse, and interpret the stories permeating the world in which we live. Despite narrative analysis offering no set rules for how the process ‘should’ unfold, 66% (N = 51) of the articles scaffolded their contributions upon the identification of narrative types.Footnote3

The most frequent narrative type identified in the reviewed articles was performance (N = 26), a highly relatable narrative type regardless of sport type or geographical location, and one identified amongst elite athletes [e.g. 2, 10, 33], professionals [e.g. 23, 26], and juniors [e.g. 57, 72]. The performance narrative type emphasises that high-performing athletes’ identities and sense of self are closely (if not entirely) related to their athletic performance as highlighted here; ‘for me, it’s natural if the training goes well, I feel good, and if the training is harder, it’s harder for me emotionally too’ (Barker-Ruchti et al. Citation2019, 694). In many cases, the performance narrative type is what drives athletes to elite accomplishments. However, the concern of many researchers is the potentially harmful side-effects that can follow this singular focus, such as disordered eating [e.g. 8, 33, 43], mental health issues following retirement [e.g. 29, 39], or playing through injury [20, 39, 71]. Furthermore, an important concept introduced within this narrative type adopted from health and illness research is narrative wreckage (see A. W. Frank Citation1995), which is the idea that the performance narrative type functions well for athletes, until it no longer does, and the athlete might not have the resources to deal with the narrative disruption. Some researchers have suggested that narrative wreckage occurs because the stories that people tell do not fit with the culturally dominant narrative types available (McLeod Citation1997), so when an elite athlete retires or career ends due to injury, how do they story their life when their identity has changed significantly? While all athletes navigate differently, and some do not experience any narrative wreckage at all (see narrative flexibility below), for others, the consequences can be severe (Douglas and Carless Citation2009).

The second most common narrative type identified in this review was the relational narrative type (N = 12), a narrative type that emerges in stark contrast to the performance narrative type,

emphasising ‘interpersonal dimensions rather than the separate self’ (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, and Zilber Citation1998, 87), is open rather than rigid, and adopts an ‘empathetic and attentive other-orientation instead of self-orientation’ (Douglas and Carless Citation2009, 223). Consequently, the relational narrative type appeared as a counter narrative that some athletes adopted making them less vulnerable to moments of narrative wreckage. To highlight, professional athletes telling relational narratives said that while sport was a big part of their life, they were more than just athletes; ‘I’m a positive and social person, I smile a lot. If we have trips abroad I try to talk to foreigners … so that everyone would have a good time and it would be nice to spend time together’ (Ronkainen and Ryba Citation2020, 554). Although the relational narrative type was found in active athletes, it was often observed that athletes transitioned from the performance narrative type to the relational narrative type, illustrating narrative flexibility (Sparkes and Smith Citation2002). Narrative flexibility refers to the ability of individuals to shift between narratives when constructing their stories, which is likely (but not necessarily) due to contextual changes (Ramos, Svensson, and Stambulova Citationin press). This adaptability allows individuals to navigate complex experiences, make sense of diverse perspectives, and effectively communicate their experiences to others. In the case of high achieving athletes, having a level of narrative flexibility can be beneficial as they are able to story their life and experiences outside of sport and performance, ideally avoiding periods of narrative wreckage (Ramos, Svensson, and Stambulova Citationin press).

The restitution narrative type, which follows the basic assumption that we can/will return to a previous state of living and underpinned by an expectation of recovery and hope, was identified eight times, and appeared repeatedly for people living with permanent or semi-permanent disability [e.g. 1, 63, 64, 67, 69, 75, 76]. Intuitively, it is logical that this was the narrative type identified by researchers working with athletes and/or people living with varying levels of disability as it gives people meaning, purpose, and a goal in the face of new circumstances. To underscore, one participant stated that, ‘I’d give everything I had to try and get back up and get walking … I don’t think I should accept it, there is always hope. If I didn’t have that hope, I wouldn’t carry on’ (Williams Citation2018, 229). However, a concern from researchers would be that what happens to a person when a present condition (i.e. spinal cord injury, chronic arthritis, etc.) becomes permanent and their life can no longer be framed around restitution? Further, while this narrative type is considered more desirable than the chaos narrative type [e.g. 36, 64, 75], it can prevent people from accepting their disability and exploring avenues that might be psychosocially and/or physically beneficial (Perrier, Smith, and Latimer-Cheung Citation2013). Finally, researchers in health and exercise research have also pointed to the quest narrative type [e.g. 1, 2, 32, 36, 63, 64] as being highly positive when people are open to growth and development in a variety of ways (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2009a).

Notably, the aims of researchers engaging with narrative inquiry were not always to identify a narrative type as 34% (N = 26) of the articles engaged with narrative in different ways. For instance, it was quite common for authorial teams to examine and interpret their data (i.e. thematic narrative analysis, structural analysis), identify narrative themes, and illuminate the findings via a realist tale [3, 4, 5, 28, 46, 47, 53, 61, 67, 74]. In this way, the authors were acting as storyanalysts and primarily interested in what stories were told, not how the participants told them. The narrative themes varied widely and were context specific. Within these 10 articles, 37 themes were identified, but never more than once. Conversely, for the seven research teams that chose to act as storytellers and not identify narrative themes or narrative types [6, 13, 40, 42, 50, 62, 66], the objective was to present the human experience through stories designed to arouse strong feelings and emotions within the reader. Further, this approach is intended to increase the readability and relatability for those both inside and outside of academia. For example, ethnodramas present findings similarly to a movie script [62, 66], portrait vignettes read like a page of a novel [6, 42, 50], while first person narratives [13, 40] stay close to the participants own words and experiences.

Critical reflections

Our state-of-the-art critical review of the last two decades of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences reveals a sharp increase in the methodology’s application, specifically since 2018 whereby 56% of the articles included in this review were published. Our analysis demonstrates that narrative inquiry links researchers together through an open ontological (i.e. relativism) and epistemological (i.e. interpretivism) perspective that underpins their philosophical worldview. Consequently, narrative researchers aim to understand personal truth, and not ‘the truth’ as others might strive to do (Monforte and Smith Citation2023). Narrative researchers share a similar language unique to the method, often acting as ‘explorers’ and uncover narrative themes and types. Further, all narrative researchers place the stories their participants tell under investigation through a plethora of analytical lenses and techniques with intentions of sharing meaningful life experiences. However, as narrative inquiry has gained a foothold within sport and exercise sciences, our review also uncovered tensions and inconsistencies that must be addressed.

Even though narrative inquiry is linked through its focus on stories, a key tenet is that it is non-prescriptive and the researchers of the eight review-type papers included in this study intentionally avoid placing parameters upon those who wish to engage with the method. For instance, Monforte and Smith (Citation2023) suggest that ‘narrative research offers no overall rules about suitable materials or modes of analysis, or the best level at which to study stories’ (p. 115), while Holstein and Gubrium (Citation2012) state that there is wide variety in what actually constitutes narrative analysis. Yet, any mode of inquiry must have boundaries, and to emphasise this point Chase (Citation2018) highlights two key issues:

First, when researchers use the term indiscriminately, describing any account, object, or performance as narrative without explaining how it is narrative, the concept becomes meaningless. Second, without a sense of the concept’s boundaries, nonnarrative ways of communicating … are marginalized in our understanding of social life. (p. 949)

Therefore, and almost paradoxically, the question becomes how we balance the openness that narrative inquiry can offer while at the same time eliminate the idea that anything goes? While the solutions to some of the tensions and inconsistencies uncovered in this review are inherently complex, we do offer some reflections below to help ensure the meaning of narrative does not become meaning(less).

Inconsistent terminology

Smith and Sparkes, (Citation2009b) are clear that ‘people tell stories, not narratives’ (p. 2), and while humans rely upon the narrative structures that are culturally available to them, it is highly unlikely they are conscious of this concept in their daily life. Therefore, narrative researchers gather stories from their participants, and it is up to them to interpret and apply the principles of narrative analysis. However, in the reviewed articles we noted that the words narrative and story/stories were often not differentiated. ‘The analysis focuses not so much on what is in the narratives, but on how the narratives are told’ [26], ‘the yogic body tells particular narratives … ’ [32], or ‘Imari and Marcus both tell sink or swim narratives … ’ [7], are a few examples of many where authors are not clear on this point. In principle, if researchers are not correctly understanding this foundational concept, then it is easy to see how the lines between what is and what is not narrative research becomes blurry.

Similarly, the way in which authors depicted and represented narratives, narrative typologies, narrative types, and narrative themes often lacked consistency. First, throughout the articles it was common for authors to use narrative, narrative type, and narrative typology interchangeably, which at face value might not appear to be problematic. Yet, one obvious issue is simply that narrative, narrative type, and narrative typology could be three different things with three different meanings, or perhaps they are supposed to be one in the same. However, when few people have been intentional about this terminology, doubt will remain. Still, a potentially larger issue is that this intersection ultimately leads to confusion when we begin to unravel the narratives, narrative types, and narrative typologies in the reviewed articles. Within this study, a clear hierarchy developed whereby three narrative types were repeatedly identified (e.g. performance, relational, and restitution). Conversely, there were many other narrative types that were only identified once, were highly contextualised, and when taking a discerning position, it could be questioned whether they were narrative types at all. This is not to undercut any of the work researchers have done, rather, it is to bring to light an issue within narrative inquiry in the sport and exercise sciences.

To elucidate further, identifiable narrative types (we will use this term to encompass

narratives, narrative types, and narrative typologies) provide a template regardless of the specific details in the stories people tell and the contexts in which they live. The restitution narrative type is a well-known example whereby people with illness, injury, or perhaps an eating disorder might tell different stories but adhere to the same narrative type. Relatedly, the CEO of a fortune 500 company might identify with the performance narrative, even though the context of business is vastly different from a high-level sporting career (see Taylor and Carroll Citation2010). Conversely, what appears often in the articles included in this study is that many narrative types identified are: 1) highly specific, and 2) might in fact be storylines rather than a narrative type. For example, narrative types such as ‘no I in team’ [21], ‘searching for the spotlight’ [30], ‘the long-term non-exerciser’ [52], or ‘more to me’ [24], speaks to the specific context in which they were identified, therefore the relatability to other aspects of the lived experience is less clear. Further, one narrative type termed the ‘Cinderella story’ [1] is specifically called a story, not a narrative type. Within this perspective, if everything is a narrative, then as Chase (Citation2018) suggested, the term narrative becomes meaningless.

To address the above stated tensions, namely the blurring of narrative types with highly contextualised narrative types and/or storylines and inconsistent terminology, we suggest negotiating the language based upon terms and frameworks that have already been used. First, we caution researchers to be more discerning when constructing narratives from their data and to consider more critically the differentiation between stories and narratives. To aid in this process, the framework of big, middle, and small stories (Griffin and Phoenix Citation2015; Phoenix and Sparkes Citation2009) could be considered as it helps to categorise stories based on their scope and context, thus facilitating a structured analysis. By maintaining this distinction, researchers can systematically identify and analyse patterns within each story type to construct broader narratives, ensuring clarity in differentiating between individual storylines and constructed narrative types.

Second, we recommend that there needs to be a return to the notion of a metanarrative (B. Smith and Sparkes Citation2005), the idea being that there are indeed a finite number of higher-level narratives that people, regardless of context, follow when storying their lives. Invariably, however, the question then becomes, ‘how many metanarratives are there?’ Admittedly, while there will most likely never be a consensus answer to this question (nor are we searching for one), as a starting point we propose people construct their stories around; 1) striving towards a new state (quest), 2) seeking a return to a previous state of being (restitution), 3) maintaining an achieved level of contentment (order), 4) experiencing a gradual deterioration over time (decay) or 5) lacking any order at all (chaos). Therefore, if we acknowledge that there is indeed the highest order of narratives (e.g. five metanarratives), then other narrative types can be referred to as such and are a subtype of one of the five metanarratives (i.e. a performance narrative type could be a derivative of the quest). Finally, we offer that highly contextualised narrative types be called context-situated narratives, acknowledging that while they may be relatable, they lack broad transferability. For example, ‘searching for the spotlight’ [30] would be a context-situated narrative, perhaps connecting to the performance narrative type and quest metanarrative. In any case, this proposition brings the potential for narrative researchers to share common language, give more meaning to narratives that are repeatedly identified in research, and also differentiate narrative types that are specific to a particular context or environment in which they were discovered.

Tensions and inconsistencies within analysis and representation

A strength of narrative inquiry is that it allows a wide berth for researchers to analyse and interpret their data. Within this review, over 20 different analytical lenses were adopted by researchers to examine the data as storyanalysts or storytellers, and narrative themes were commonly generated to either structure the metanarrative or narrative types, and/or present the stories via creative analytical practices or realist tales. Yet, even though narrative analysis is an open analytical technique with recommendations rather than rules, our review of the last two decades of narrative inquiry demonstrates tensions and inconsistencies within the process.

A major tension that became evident during the screening process was that in many cases the line between a narrative analysis and other qualitative methodologies (i.e. thematic analysis) is somewhat unclear. Primarily, this tension relates to authors adhering to a narrative analysis but falling short of interpreting how the data is narrative or what this narrative might actually mean (Chase Citation2018)? In other words, if the authors do not engage with the theoretical aspects of narrative, then how do we differentiate between narrative analysis and other approaches? Importantly, to be included in this review a primary inclusion criterion was the authors’ engagement with narrative discourse (see Monforte and Smith Citation2023), which all 77 included articles did well. The issue, rather, appeared when reviewing the 188 articles that made it through the first screening round and identifying that many of the excluded 111 papers either did not engage with stories, did not engage with narrative discourse, or both. Principally, this problem did not often appear in the literature review or methods sections as most research teams were clear on their positions, referenced relevant narrative theorists, and utilised a narrative methodology in the analysis process. Rather, there were many examples (i.e. Budden et al. Citation2022; Eke et al. Citation2020; Erickson, Backhouse, and Carless Citation2017) in related discussions whereby narrative discourse were rarely mentioned, or in some cases, the word narrative never appeared at all. Crucially, we are not discounting the work done or minimising any contributions that authors have made. Nevertheless, this review has revealed that this essential aspect of narrative inquiry can (and has) been neglected in published articles within the field.

Subsequently, another inconsistency rests in the methodological positions that researchers adopt (i.e. storyteller vs. storyanalyst, or both) and the perspective of whether they will examine the whats and/or hows of stories and narratives. These methodological perspectives appeared in Smith & Sparkes, Citation2009a, Citation2009b) narrative review-type papers, which built upon the work of A. Frank (Citation2007, Citation1995), highlighting that researchers take varying perspectives when performing the analysis. The most common perspective adopted was that of a storyanalyst [N = 62] whereby researchers would scrutinise the content (i.e. what), the structure (i.e. how), or both. However, within these positions our analysis showcased that authors were somewhat inconsistent between their stated position and then how the findings were represented. First, there were numerous examples [e.g. 17, 23, 59] where authors would state that they were taking the position of storyanalysts, yet the findings were represented as if they acted as storytellers. Second, there were very few instances where authors operated exclusively as storytellers [42, 50], meaning they truly embraced Frank’s (Citation1995) position that ‘thinking with stories takes the story as already complete; there is no going beyond it’ (p. 23), and as a result there was little discussion concerning the stories showcased in the article. Further, most authorial teams acting as storytellers also took the position of a storyanalyst [e.g. 6, 16, 60, 62], even if it was not specifically stated. Finally, a third tension was that while authors applied multiple narrative analysis lenses to interact with the data, it was hard to distinguish how a particular procedure led to an outwardly different conclusion. For instance, there were many examples where authors used different techniques (i.e. HFSA [11], a SA [2], or a NASF [22]) but the end results were similar, in this case the identification of a performance narrative.

Research gaps, future challenges, and recommendations

Our state-of-the-art critical review over the past two decades of narrative research in sport and exercise sciences highlights a maturing field that has significantly advanced our understanding of human experiences. Despite the growth and methodological diversity, several gaps and challenges remain that warrant attention. To address these issues and promote further development, we propose a series of recommendations focused on methodological rigour, theoretical and conceptual clarity, and empirical and applied expansion. These recommendations aim to enhance the clarity of narrative inquiry practices, negotiate consistency in terminology and analysis, and encourage broader application across diverse contexts within sport and exercise sciences. Furthermore, they emphasise the importance of establishing boundaries within narrative inquiry to maintain its integrity and respect the discipline’s unique methodological and theoretical foundations.

The language used in narrative research should be better negotiated to prevent confusion and misunderstandings. We propose that the highest order narratives be referred to as metanarratives, such as restitution, quest, order, decay, and chaos. The level below are narrative types, a subtype of one of the five metanarratives and maintains a high degree of transferability to other contexts. Finally, context-situated narratives are specific to a given situation and lack broad transferability.

The line between when a story ends and a narrative begins can be hazy, and there were many instances in the reviewed articles whereby identified narrative types were more likely to be storylines. Therefore, we urge researchers to be clearer in their differentiation between narratives and stories, and using the big, middle, and small story framework can be a useful approach (Griffin and Phoenix Citation2015).

For researchers new to narrative inquiry, the diversity of analytical techniques can be daunting. We suggest simplifying this by focusing on the two most common approaches used in the reviewed articles: analysing the content (i.e. what is being said) or the structure of stories (i.e. how they are being said). Researchers can also combine both perspectives using bracketing. While researchers are free to choose any method, promoting these two approaches can make narrative inquiry more appealing and accessible.

There is an imbalance in the research, with only 20% of the articles focusing on exercise, health, and physical activity. Researchers are encouraged to expand narrative research in these areas, particularly investigating the experiences of youth, children, the elderly, and marginalised communities. Additionally, exploring the impact of physical activity on mental health and chronic disease management could provide valuable insights. Broadening the scope of narrative research will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of diverse experiences in health, physical activity, and exercise contexts.

The vast majority of the reviewed studies involved researchers and participants based in Western countries. To enhance the global applicability and richness of narrative research, we recommend that future studies actively seek to include participants from diverse cultural backgrounds and non-Western contexts. This will help to uncover a wider array of narrative experiences and perspectives, providing a more comprehensive understanding of sport, exercise, and health across different cultural and socio-economic environments.

We believe that a deeper understanding of narrative characters, archetypal characters (i.e. brute, conformist, egoist, citizen), and character roles (e.g. the protagonist, antagonist) offers potential for applied practitioners in their work. Researchers state that ‘where there is an identifiable genre, plot, and character, there is usually a narrative’ (Papathomas Citation2016, 40), yet character development is scantly discussed in any of the reviewed articles. For instance, could it not be relevant for a coach to understand the characters the team needs to be successful considering that not everyone can be the hero?

The performance narrative type is well-established in sport and exercise science literature, but it is time to understand the practical applications. Beyond identifying its existence, researchers should expose athletes to the dangers of narrative wreckage (e.g. depression, identity loss) and strategies to mitigate these challenges. Promoting cultural narrative diversity and encouraging narrative flexibility may enrich athletes’ experiences. Practitioners can also actively use narratives in their interventions to support athlete well-being and resilience. Integrating these approaches can provide a more holistic understanding and practical application of narratives in sport and exercise contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert T. Book

Robert T. Book Jr is an associate professor in the Department of Sports, Physical Education, and Outdoor Studies at the University of South-Eastern Norway. His research focuses on athletic talent development environments, career pathways, cultural transitions, and narrative methodology.

Joar Svensson

Joar Svensson is a lecturer in the School of Health and Welfare at Halmstad University. His work as a researcher has focused on career development and motivation whereas his applied work concentrates on peak performance in elite athletes and Michelin starred chefs.

Natalia Stambulova

Natalia Stambulova is a professor in the School of Health and Welfare at Halmstad University. Her robust research portfolio pertains to the full span of the athletic career, with a primary focus on elite sport, career transitions, and crisis intervention.

Notes

1. This includes an expansion and re-examination of our search process following reviewer and editor feedback during the revision process.

2. Authors are not required to state their position, and this methodological position was a development that happened over time, becoming more ingrained following Smith and Sparkes’ recommendations (Citation2009a; Citation2009b).

3. Researchers would either identify an undiscovered narrative type, add to the robustness of a previously identified narrative type, or both.

References

- Åkesdotter, C., G. Kenttä, and A. C. Sparkes. 2023. “Elite Athletes Seeking Psychiatric Treatment: Stigma, Impression Management Strategies, and the Dangers of the Performance Narrative.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 36 (1): 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2023.2185697.

- Allan, V., B. Smith, J. Côté, K. A. Maritn Ginis, and A. E. Latimer-Cheung. 2018. “Narratives of Participation Among Individuals with Physical Disabilities: A Life-Course Analysis of Athletes’ Experiences and Development in Parasport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 37:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.004.

- Barker-Ruchti, N., A. Schubring, A. Post, and S. Pettersson. 2019. “An Elite Athlete’s Storying of Injuries and Non-Qualification for an Olympic Games: A Socio-Narratological Case Study.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (5): 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1605405.

- Battaglia, A., G. Kerr, and A. Stirling. 2022. ““It’s Less About You as a Person and More About the Result You Can produce”: Examining Coach and Peer Dynamics in Sport from a Psychosocial Perspective.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (3): 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1947884.

- Bennett, E. V., L. Hurd Clarke, K. C. Kowalski, and P. R. E. Crocker. 2017. “From Pleasure and Pride to the Fear of Decline: Exploring the Emotions in Older Women’s Physical Activity Narratives.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 33:113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.012.

- Bennett, E. V., L. R. Trainor, A. M. Bundon, M. Tremblay, S. Mannella, and P. R. E. Crocker. 2022. “From “Blessing in Disguise” to “What Do I Do now?”: How Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Hopefuls Perceived, Experienced, and Coped with the Postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Games.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 62:102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102246.

- Blodgett, A. T., Y. Ge, R. J. Schinke, and K. R. McGannon. 2017. “Intersecting Identities of Elite Female Boxers: Stories of Cultural Difference and Marginalization in Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 32:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.006.

- Book, R. T., K. Henriksen, and N. Stambulova. 2021. “Sink or Swim: Career Narratives of Two African American Athletes from Underserved Communities in the United States.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (6): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1787490.

- Bruner, J. 1986. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Budden, T., J. A. Dimmock, B. Smith, M. Rosenberg, M. R. Beauchamp, and B. Jackson. 2022. “Making Sense of Humour Among Men in a Weight-Loss Program: A Dialogical Narrative Approach.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (7): 1098–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1979635.

- Busanich, R., K. R. McGannon, and R. J. Schinke. 2014. “Comparing Elite Male and Female Distance Runners’ Experiences of Disordered Eating Through Narrative Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15 (6): 705–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.002.

- Busanich, R., K. R. McGannon, and R. J. Schinke. 2016. “Exploring Disordered Eating and Embodiment in Male Distance Runners Through Visual Narrative Methods.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 8 (1): 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1028093.

- Carless, D. 2014. “Narrative Transformation Among Military Personnel on an Adventurous Training and Sport Course.” Qualitative Health Research 24 (10): 1440–1450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314548596.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2009. “‘We haven’t Got a Seat on the Bus for you’ or ‘All the Seats Are Mine’: Narratives and Career Transition in Professional Golf.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 1 (1): 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398440802567949.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2013a. ““In the Boat” but “Selling Myself Short”: Stories, Narratives, and Identity Development in Elite Sport.” The Sport Psychologist 27 (1): 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.27.1.27.

- Carless, D., and K. Douglas. 2013b. “Living, Resisting, and Playing the Part of the Athlete: Narrative Tensions in Elite Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 14 (5): 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.05.003.

- Carless, D., and A. C. Sparkes. 2008. “The Physical Activity Experiences of Men with Serious Mental Illness: Three Short Stories.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 9 (2): 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.03.008.

- Carless, D., A. C. Sparkes, K. Douglas, and C. Cooke. 2014. “Disability, Inclusive Adventurous Training and Adapted Sport: Two Soldiers’ Stories of Involvement.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15 (1): 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.001.

- Cavallerio, F., R. Wadey, and C. R. D. Wagstaff. 2017. “Adjusting to Retirement from Sport: Narratives of Former Competitive Rhythmic Gymnasts.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 9 (5): 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1335651.

- Chase, S. E. 2018. “Narrative Inquiry: Toward Theoretical and Methodological Maturity.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 946–970. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Coker-Cranney, A., J. C. Watson, M. Bernstein, D. K. Voelker, and J. Coakley. 2018. “How Far Is Too Far? Understanding Identity and Overconformity in Collegiate Wrestlers.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10 (1): 92–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1372798.

- Collard, S. S., and C. Marlow. 2016. ““It’s Such a Vicious cycle”: Narrative Accounts of the Sportsperson with Epilepsy.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 24:56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.01.007.

- Cooper, H. B., and T. K. Ewing. 2020. “The Role of Sport (And Sporting Stories) in a family’s Navigation of Identity and Meaning.” Sport, Education and Society 25 (4): 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1596892.

- Cowan, D., and I. M. Taylor. 2016. “‘I’m Proud of What I Achieved; I’m Also Ashamed of What I done’: A Soccer coach’s Tale of Sport, Status, and Criminal Behaviour.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 8 (5): 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1206608.

- Crossen, W., N. Wadsworth, N. J. Ronkainen, D. Haslett, and D. Tod. 2023. “Identity in Elite Level Disability Sport: A Systematic Review and Meta-Study of Qualitative Research.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology: 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2214993.

- Darpatova-Hruzewicz, D. 2022. “Reflexive Confessions of a Female Sport Psychologist: From REBT to Existential Counselling with a Transnational Footballer.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (2): 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1885481.

- Day, M. C., J. Hine, R. Wadey, and F. Cavallerio. 2023. “A Letter to My Younger Self: Using a Novel Written Data Collection Method to Understand the Experiences of Athletes in Chronic Pain.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 15 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2127860.

- Demetriou, A., A. Jago, P. R. Gill, C. Mesagno, and L. Ali. 2020. “Forced Retirement Transition: A Narrative Case Study of an Elite Australian Rules Football Player.” International Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 18 (3): 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1519839.

- Denison, J. 2016. “Social Theory and Narrative Research: A Point of View.” Sport, Education & Society 21 (1): 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1076385.

- Douglas, K., and D. Carless. 2006. “Performance, Discovery, and Relational Narratives Among Women Professional Tournament Golfers.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 15 (2): 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.15.2.14.

- Douglas, K., and D. Carless. 2009. “Abandoning the Performance Narrative: Two Women’s Stories of Transition from Professional Sport.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 21 (2): 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200902795109.

- Eke, A., M. Adam, K. Kowalski, and L. Ferguson. 2020. “Narratives of Adolescent Women Athletes’ Body Self-Compassion, Performance and Emotional Well-Being.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (2): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628805.

- Ekengren, J., N. B. Stambulova, U. Johnson, I.-M. Carlsson, and T. V. Ryba. 2019. “Composite Vignettes of Swedish Male and Female Professional Handball players’ Career Paths.” In Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media: Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1599201.

- Ely, G., and N. J. Ronkainen. 2021. ““It’s Not Just About Football All the Time either”: Transnational Athletes’ Stories About the Choice to Migrate.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19 (1): 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1637364.

- Erickson, K., S. H. Backhouse, and D. Carless. 2017. ““I don’t Know if I Would Report them”: Student-athletes’ Thoughts, Feelings and Anticipated Behaviours on Blowing the Whistle on Doping in Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 30:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.01.005.

- Evans, A. B., S. Andreassen, and A. W. Virklund. 2020. ““Together, We Can Do it all!”: Narratives of Masculinity, Sport and Exercise Amongst Physically Wounded Danish Veterans.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (5): 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1672774.

- Everard, C., R. Wadey, and K. Howells. 2021. “Storying Sports Injury Experiences of Elite Track Athletes: A Narrative Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 56:102007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102007.

- Franck, A., and N. Stambulova. 2018a. “Individual Pathways Through the Junior-To-Senior Transition: Narratives of Two Swedish Team Sport Athletes.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 32 (2): 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1525625.

- Franck, A., and N. Stambulova. 2018b. “The Junior to Senior Transition: A Narrative Analysis of the Pathways of Two Swedish Athletes.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1479979.

- Frank, A. 2007. “Five Dramas of Illness.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 50 (3): 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2007.0027.

- Frank, A. W. 1995. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

- Frank, A. W. 2010. Letting Stories Breathe. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

- Frank, A. W. 2013. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Gergen, K. J., and M. M. Gergen. 1986. “Narrative Form and the Construction of Psychological Science.” In Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct, edited by T. R. Sarbin, 22–44. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Graham, L. C., and A. D. Blackett. 2022. “‘Coach, or Female Coach? And Does it matter?’: An Autoethnography of Playing the Gendered Game Over a Twenty-Year Elite Swim Coaching Career.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (5): 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1969998.

- Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Griffin, M., and C. Phoenix. 2015. “Becoming a Runner: Big, Middle and Small Stories of Physical Activity Participation in Later Life.” Sport, Education and Society 21 (1): 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1066770.

- Holstein, J. F., and J. A. Gubrium. 2012. “Introduction.” In Varieties of Narrative Analysis, edited by J. F. Holstein and J. A. Gubrium, 1–11. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Howells, K., and D. Fletcher. 2015. “Sink or Swim: Adversity- and Growth-Related Experiences in Olympic Swimming Champions.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 16:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.004.

- Hudson, J., M. C. Day, and E. J. Oliver. 2015. “A ‘New life’ Story or ‘Delaying the inevitable’? Exploring Older people’s Narratives During Exercise Uptake.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 16:112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.09.004.

- Jewett, R., G. Kerr, and K. Tamminen. 2019. “University Sport Retirement and Athlete Mental Health: A Narrative Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (3): 416–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1506497.

- John, J. M., and A. Thiel. 2022. “All Roads Lead to Rome? Talent Narratives of Elite Athletes, Musicians, and Mathematicians.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (7): 1174–1195. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2074078.

- Kaushik, N., V. Allan, A. E. Latimer-Cheung, J. Koch, and S. N. Sweet. 2023. “Exploring the Leisure Time Physical Activity (LTPA) Experiences of Women with a Physical Disability in India.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 15 (5): 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2023.2185280.

- Keaton, A. C. I. 2022. “A Critical Discourse Analysis of Racial Narratives from White Athletes Attending a Historically Black College/University.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (6): 969–986. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1944901.

- Labov, W., and J. Waletzky. 1967. “Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience.” In J. Helm (Ed.), Essays on The verbal and Visual arts: Proceedings Ofthe 1966 AnnualSpring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society edited by H. J, 12–44. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Leledaki, A. 2014. “Body-Selves and Health-Related Narratives in Modern Yoga and Meditation Methods.” Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise 6 (2): 278–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.712994.

- Lieblich, A., R. Tuval-Mashiach, and T. Zilber. 1998. Narrative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lowry, A., R. C. Townsend, K. Petrie, and L. Johnston. 2022. “‘Cripping’ Care in Disability Sport: An Autoethnographic Study of a Highly Impaired High-Performance Athlete.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (6): 956–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2037695.

- McGannon, K. R., S. Graper, and J. McMahon. 2022. “Skating Through Pregnancy and Motherhood: A Narrative Analysis of Digital Stories of Elite Figure Skating Expectant Mothers.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 59:102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102126.

- McGannon, K. R., M. L’Estrange, and J. McMahon. 2020. “The Role of Ultrarunning in Drug and Alcohol Addiction Recovery: An Autobiographic Study of Athlete Journeys.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 46:46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101585.

- McGannon, K. R., and J. McMahon. 2019. “Understanding Female Athlete Disordered Eating and Recovery Through Narrative Turning Points in Autobiographies.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 40:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.003.

- McGannon, K. R., and J. McMahon. 2022. “Stories from Mother Runners: A Case Study and Narrative Analysis of Facilitators for Competitive Running.” Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology 6 (1): 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2022-0011.

- McGannon, K. R., L. Pomerleau-Fontaine, and J. McMahon. 2020. “Extreme Sport, Identity, and Well-Being: A Case Study and Narrative Approach to Elite Skyrunning.” Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology 4 (S1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssep.2019-0031.

- McGannon, K. R., and B. Smith. 2015. “Centralizing Culture in Cultural Sport Psychology: The Potential of Narrative Inquiry and Discursive Psychology.” Psychology of Sport & Exercise 17:79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.010.

- McGannon, K. R., T. G. Staden, and J. McMahon. 2022. “From Superhero to Human: A Narrative Analysis of Digital News Stories of Retirement from the NFL Due to Injury.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 34 (5): 938–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2021.1987351.

- McGannon, K. R., E. Tatarnic, and J. McMahon. 2019. “The Long and Winding Road: An Autobiographic Study of an Elite Athlete Mother’s Journey to Winning Gold.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 31 (4): 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1512535.

- McLeod, J. 1997. Narrative and Psychotherapy. London, U.K: Sage.

- McMahon, J., and D. Penney. 2013. “(Self-) Surveillance and (Self-) Regulation: Living by Fat Numbers within and Beyond a Sporting Culture.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 5 (2): 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2012.712998.

- Middleton, T. R. F., R. J. Schinke, O. P. Oghene, K. R. McGannon, B. Petersen, and S. Kao. 2020. “Navigating Times of Harmony and Discord: The Ever-Changing Role Played by the Families of Elite Immigrant Athletes During Their Acculturation.” Sport, Exercise, & Performance Psychology 9 (1): 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000171.

- Monforte, J., and B. Smith. 2023. “Narrative Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, edited by H. Cooper, 109–130. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Owton, H., and A. C. Sparkes. 2017. “Sexual Abuse and the Grooming Process in Sport: Learning from Bella’s Story.” Sport, Education and Society 22 (6): 732–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1063484.

- Papathomas, A. 2016. “Narrative Inquiry: From Cardinal to Marginal … and Back?” In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, edited by B. Smith and A. Sparkes, 37–48. London, U.K: Routledge.

- Papathomas, A., and D. Lavallee. 2014. “Self-Starvation and the Performance Narrative in Competitive Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15 (6): 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.014.

- Partington, E., S. Partington, L. Fishwick, and L. Allin. 2005. “Mid-Life Nuances and Negotiations: Narrative Maps and the Social Construction of Mid-Life in Sport and Physical Activity.” Sport, Education and Society 10 (1): 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/135733205200098820.

- Partington, S., J. Smith, F. Longstaff, and E. Partington. 2024. “Narratives of Adventure, Intimacy, Conformity, and Rejection: Narrative Inquiry as a Methodological Approach to Understanding How Women Student Athletes ‘Do’ Sport-Related Drinking.” Sport, Education and Society 29 (1): 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2105315.

- Perrier, M. J., B. Smith, and A. E. Latimer-Cheung. 2013. “Narrative Environments and the Capacity of Disability Narratives to Motivate Leisure-Time Physical Activity Among Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury.” Disability and Rehabilitation 35 (24): 2089–2096. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.821179.

- Phoenix, C., and N. Orr. 2017. “Analysing Exceptions within Qualitative Data: Promoting Analytical Diversity to Advance Knowledge of Ageing and Physical Activity.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 9 (3): 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1282539.

- Phoenix, C., and A. C. Sparkes. 2007. “Sporting Bodies, Ageing, Narrative Mapping and Young Team Athletes: An Analysis of Possible Selves.” Sport, Education and Society 12 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320601081468.

- Phoenix, C., and A. C. Sparkes. 2009. “Being Fred: Big Stories, Small Stories and the Accomplishment of a Positive Ageing Identity.” Qualitative Research 9 (2): 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794108099322.

- Prato, L., M. Torregrosa, Y. Ramis, S. Alcaraz, and B. Smith. 2021. “Assembling the Sense of Home in Emigrant Elite Athletes: Cultural Transitions, Narrative and Materiality.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 55:55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101959.

- Quarmby, T., R. Sandford, O. Hooper, and R. Duncombe. 2021. “Narratives and Marginalised Voices: Storying the Sport and Physical Activity Experiences of Care-Experienced Young People.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (3): 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1725099.

- Ramos, A., J. Svensson, and N. Stambulova. in press. “Navigating the Unknown: A Narrative Exploration of Career Pathways in Esports.” Scandinavian Journal Sport and Exercise Psychology.

- Richardson, E. V., E. A. Barstow, and R. W. Motl. 2019. “A Narrative Exploration of the Evolving Perception of Exercise Among People with Multiple Sclerosis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (1): 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1509369.

- Rogers, M., and P. Werthner. 2023. “Gathering Narratives: Athletes’ Experiences Preparing for the Tokyo Summer Olympic Games During a Global Pandemic.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 35 (2): 330–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2022.2032477.

- Ronkainen, N. J., and T. V. Ryba. 2020. “Developing Narrative Identities in Youth Pre-Elite Sport: Bridging the Present and the Future.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 12 (4): 548–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1642238.

- Ronkainen, N. J., T. V. Ryba, and A. Khomutova. 2019. ““If My Family Is Okay, I’m okay:” Exploring Relational Processes of Cultural Transition.” International Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 17 (5): 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1390485.

- Ronkainen, N. J., I. Watkins, and T. V. Ryba. 2016. “What Can Gender Tell Us About the Pre-Retirement Experiences of Elite Distance Runners in Finland?: A Thematic Narrative Analysis.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 22:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.003.

- Ryba, T. V., N. J. Ronkainen, K. Douglas, and K. Aunola. 2021. “Implications of the Identity Position for Dual Career Construction: Gendering the Pathways to (Dis)continuation.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 53:53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101844.

- Ryba, T. V., N. Stambulova, H. Selänne, K. Aunola, and J. E. Nurmi. 2017. ““Sport Has Always Been First for me” but “All My Free Time Is Spent Doing homework”: Dual Career Styles in Late Adolescence.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 33:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.011.

- Schinke, R. J., A. T. Blodgett, K. R. McGannon, Y. Ge, O. Oghene, and M. Seanor. 2017a. “Adjusting to the Receiving Country Outside the Sport Environment: A Composite Vignette of Canadian Immigrant Amateur Elite Athlete Acculturation.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 29 (3): 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2016.1243593.

- Schinke, R. J., A. T. Blodgett, K. R. McGannon, Y. Ge, O. Oghene, and M. Seanor. 2017b. “A Composite Vignette on Striving to Become “Someone” in My New Sport System: The Critical Acculturation of Immigrant Athletes.” The Sport Psychologist 30 (4): 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2015-0126.

- Sille, R. A., N. J. Ronkainen, and D. A. Tod. 2020. “Experiences Leading Elite Motorcycle Road Racers to Participate at the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT): An Existential Perspective.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13 (3): 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1618387.

- Smith, B. 2010. “Narrative Inquiry: Ongoing Conversations and Questions for Sport and Exercise Psychology Research.” International Review of Sport & Exercise Psychology 3 (1): 87–107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17509840903390937.

- Smith, B. 2016. “Narrative Analysis in Sport and Exercise: How Can it Be Done?” In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, edited by B. Smith and A. C. Sparkes, 260–273. London, U.K: Routledge.

- Smith, B., A. Bundon, and M. Best. 2016. “Disability Sport and Activist Identities: A Qualitative Study of Narratives of Activism Among Elite Athletes with Impair- Ment.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 26:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.07.003.

- Smith, B., and A. Sparkes. 2009a. “Narrative Analysis and Sport and Exercise Psychology: Understanding Lives in Diverse Ways.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10 (2): 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.07.012.

- Smith, B., and A. Sparkes. 2009b. “Narrative Inquiry in Sport and Exercise Psychology: What Can it Mean, and Why Might We Do It?” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.01.004.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2002. “Men, Sport, Spinal Cord Injury and the Construction of Coherence: Narrative Practice in Action.” Qualitative Research 2 (2): 143–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410200200202.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2004. “Men, Sport, and Spinal Cord Injury: An Analysis of Metaphors and Narrative Types.” Disability & Society 19 (6): 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000252533.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2005. “Men, Sport, Spinal Cord Injury, and Narratives of Hope.” Social Science & Medicine 61 (5): 1095–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.011.

- Smith, B., and A. C. Sparkes. 2011. “Exploring Multiple Responses to a Chaos Narrative.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 15 (1): 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459309360782.

- Smith, M., and C. Arthur. 2022. “Understanding Coach-Athlete Conflict: An Ethnodrama to Illustrate Conflict in Elite Sport.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 14 (3): 474–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1946130.