ABSTRACT

In China the idea of common prosperity dates back to 1953. After 1979 China chose to let some people and places get rich first to accelerate economic development, with Deng Xiaoping arguing that public property could prevent social polarization. The result was extraordinary sustained economic growth but at the expense of large increases in urban-rural, regional and social inequalities in income and wealth themselves associated with the growth of private capital. In 1999 China started to address urban-rural and regional disparities in the name of common prosperity, while under the leadership of Xi Jinping the emphasis on common prosperity has increased markedly alongside domestic goals relating to innovation, improved governance and ecological and spiritual civilization. Starting in 2020, this course has seen strong government action against the disorderly expansion of private capital, monopolies, speculation and the costs of privately provided education, housing and potentially health, as well as the establishment of a demonstration zone in Zhejiang province to explore ways to address uneven development and reshape the primary, secondary and tertiary distributions of income.

1. The Meaning of Common Prosperity

On August 17, 2021, in a meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, Chinese President Xi Jinping called on China to promote common prosperity (material, ecological and cultural) in a context of high quality development. In circumstances in which indigenous innovation is desired, a new industrial revolution is on the horizon and ecological civilization construction is designed to address environmental challenges, high quality development of the productive forces remains and will remain of vital importance, enabling China to advance from an upper middle to a high-income country. However, the combination of high quality development with a quest for common prosperity and the increasingly frequent use of this term in defining China’s development direction are particularly significant and increasingly seen as mapping a new phase (a new era) in China’s path to socialism.

The phrase “common prosperity” first appeared in an article in the People’s Daily on September 25, 1953. On December 12, 1953, it appeared in the headline of a People’s Daily article entitled “The Path of Socialism is the Path to Common Prosperity.” Advanced as a step on the path to rural mutual aid, cooperatives and collectivization, collective prosperity was associated with the holding of resources in common. Just four days later the Communist Party of China (CPC) released its “Resolution on the Development of Agricultural Production Cooperatives.” Drafted under the chairmanship of Mao Zedong, it invoked “common prosperity” as a goal of China’s socialist construction (Cao Citation2021; Ge Citation2021).

In the late 1970s, the term was often used by Deng Xiaoping to characterize socialism (Deng [Citation1979] Citation2014, Citation1999). Again in the 1980s it was frequently used in his insistence that common prosperity (entailing the avoidance of polarization) and the predominance of public ownership are fundamental socialist principles.

At the end of the 1970s, however, an earlier association between common prosperity and egalitarianism was rejected. On April 15, 1979, the People’s Daily carried an article entitled “A Few Getting Rich First and Common Prosperity.” Increasingly, it was argued that to speed up the development of the productive forces, achieve the four modernizations and accelerate the arrival of common prosperity, some people and some places should be allowed to get rich first, with others getting rich later. Deng Xiaoping’s words repeated on a number of occasions are particularly important:

In short, predominance of public ownership and common prosperity are the two fundamental socialist principles that we must adhere to. The aim of socialism is to make all our people prosperous, not to create polarization. If our policies led to polarization, it would mean that we had failed; if a new bourgeoisie emerged, it would mean that we had strayed from the right path. In encouraging some regions to become prosperous first, we intend that they should inspire others to follow their example and that all of them should help economically backward regions to develop. The same holds good for some individuals. (Deng [Citation1985] Citation2014b)

In the capitalist mode of production, the means of production and exchange are privately owned. In societies in which the capitalist mode of production predominates, private ownership derives from multiple (often corrupt) processes of primitive accumulation or accumulation by dispossession, and in a context of competitive accumulation of capital is associated with a concentration and centralization of assets and wealth in the hands of a small share of the population. This concentration of property in the hands of a class of private owners is the root cause of the gap between the rich and the poor. Although these mechanisms can lead in the direction of the establishment of monopolies, the concentration and centralization of capital derive from market competition. Market competition gives rise to unending turbulence, and companies that act as monopolies or oligopolies at one stage in time can lose positions of dominance at another. Measures preventing and addressing the emergence of monopoly power do help. However, anti-monopoly measures do not prevent the polarization of wealth and income (in the sense of a large and widening gap between rich and poor), as the accumulation of money capital in competitive conditions (especially where returns to scale are increasing) is self-reinforcing.

Capital-centered societies have created considerable material wealth, and the material living standards of working people have increased significantly, especially in the post-war golden age when the incomes of low-income groups grew faster than those of high income groups (Piketty Citation2014). This outcome was however a result of an economic and political compromise, deriving from the struggles of working class people and their social movements and political parties at home, and the challenge of communism. In that era, trades union wage bargaining saw real wages increase steadily with productivity growth, while welfare states/social security co-existed with the capitalist mode of production (combined in many cases with significant state capital and Keynesian macro management). Welfare funded principally out or taxation paid by the wage earning classes provided citizens with significant minimum rights and life guarantees (Dunford Citation1990). This era was however exceptional, and since the 1970s the competitive accumulation of private capital along with governments that principally serve capitalist interests are the main reasons for the polarization of income and wealth and the expanded reproduction of income and wealth gaps in capitalist countries. As wealth and income accumulate at one end of the spectrum, non-owners, comprising the great majority of the population, are denied similar rights due to extreme self-reinforcing disparities in the ownership of private assets.

After the 1970s, Western capitalist societies moved in the direction of marketization, privatization and internationalization, and also in the direction of financialisation. Alongside the profits of capitalist enterprises, the owners of marketised land, natural resources and natural monopolies acquire economic rents. These rents are associated with monopoly positions, scarcity and differential advantages that cause the market values of the goods and services involving their use (land uses) to exceed their prices of production. In capitalist economies rents accrue to real estate capital and are also financialised: assets are pledged as collateral for financial sector loans, owners incur debts, and revenues on rent yielding assets are transformed into compound interest payments. Credit drives asset price inflation, while debtors unable to repay are expropriated, leading to a greater concentration of wealth in the hands of the financial sector. A relative increase in rentier and financial incomes and asset values diverts income away from real production and consumption, while in the absence of effective regulation capital market liberalization permits capital flight, tax evasion and money laundering. In financialised economies, debt grows faster than the real production of goods and services, and financial and real estate interests seek leverage over money, credit creation and quantitative easing. In these conditions inequality increased dramatically.

The aim of socialism is people-centered rather than capital-centered development. The principal goal is to orient economic and social activities towards the production of goods and services that are socially useful, increase social well-being and enable all human beings to realize their potential and live happy and fulfilling lives (common prosperity). Although the material conditions for common prosperity (which itself involves an evolving and not a fixed standard) include development of the productive forces (although not the one-sided pursuit of GDP growth), the avoidance of polarization requires the development and improvement of socialist public ownership which also contributes to the development of the productive forces and national strength. Deng Xiaoping made this clear on repeated occasions. “As long as public ownership occupies the main position in our economy, polarization can be avoided,” he said (Deng [Citation1985] Citation2014a, 149). In the public-owned socialist economy in the primitive stage of socialism, distribution should also depend on labor contributions, itself a way of avoiding social polarization. Contributions, however, vary. As a result, incomes will vary but the differences should not be large. At the same time, public ownership limits the possibilities of securing very high incomes as a result of private ownership of means of production and the exploitation of labor by capital (Wei Citation2021)Footnote1 as well as the commercial exploitation of real estate and financial assets.

The implication is that the eventual liberation of the working classes, realization of the realm of freedom and comprehensive human developmentFootnote2 require the replacement of private by collective ownership of economic assets and shared rights to and enjoyment of the fruits of their use in a communist society. The path to communism, however, involves a series of steps. These steps include a socialist stage (of to each according to his/her contribution) itself evolving from primitive to successively higher levels.

At present common prosperity is not equality. Not only are people’s living needs differentiated, requiring multi-channel supply systems. At the socialist stage (even after the elimination of private ownership of the means of production and exchange), the development of the productive forces remains limited. In the case of China, it needs to advance socialist modernization, upgrade, innovate and escape the model of the recent past in which it imported high-end intermediate and capital goods and exported low end assembled products. In this situation, investment in skills and in indigenous science, technology and innovation is essential and will be associated with a distribution of rewards according to the quantity and quality of labor contributions. At present differences that are justified are moreover widely accepted. Differences that are not are widely condemned. Differences need not be large. In this new stage, however, the view that one “should give priority to efficiency with due consideration to fairness” (Jiang Citation2002)Footnote3 is decisively giving way to a concept of shared development in which what is produced contributes to material, ecological and cultural needs, excessive primary income and wealth gaps are closed, distribution is reasonable,Footnote4 and the quality of lives of all improves, building on China’s success in eliminating extreme poverty.

The realization of common prosperity echoes the construction of a community of shared future for mankind (Xi Citation2017). The establishment of an international division of labor has created a world in which developed countries with their relatively advanced industrial and military technologies and their financial power extract value from developing countries, reproducing a global divide between the rich and the poor. Common prosperity as a national ambition has a counterpart in a global demand for shared development and common prosperity.

2. China’s Path

The identification of a new path of common prosperity is a new step in the evolution of the People’s Republic of China. In 1949, China was a very poor country. In the next 30 years, its economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% per year. China remained a low income country, but according to The World Bank (Citation1981, 101), the 1979 life expectancy of 64 was higher than the average of 51 for low income countries and 61 for middle-income countries, adult literacy stood at 66% compared with 39% in low income countries and 72% in middle income ones, while net primary school enrollment (93%) was just short of that for industrialized countries (94%). China’s population had nearly doubled. In the words of a glowing 1983 report of The World Bank (Citation1983, 11), “China’s most remarkable achievement during the past three decades” was to have made “low-income groups far better off in terms of basic needs than their counterparts in most other poor countries” due to priorities attached to food, education and health. The authors of the report concluded that with the right policies, China’s “immense wealth of human talent, effort and discipline” would enable it “within a generation or so, to achieve a tremendous increase in the living standards of its people” (The World Bank Citation1983, 29).

In the early 1970s, after the visit of US President Richard Nixon to China, a US embargo ended and China started to acquire Western technologies. In 1979, it embarked on reform and opening-up, leading to historically unprecedented economic growth. As industrialization, urbanization and informatization advanced, the Chinese economy grew on average at 9.3% per year. By 2020 China was an upper middle income country with an average Gross National Income (GNI) per head of US$ 10,610. At present it is expected to join the ranks of the high-income economies during the country’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) period.

China’s extraordinary growth transformed it into the second largest economy in the world, the world’s largest exporter, the second largest exporter of capital, the holder of huge foreign currency reserves (US$ 3.20 trillion in January 2021, down from a peak of 3.8 trillion in 2014), the owner of a currency that is increasingly used to settle international payments, the owner of a vast, increasingly affluent and highly coveted domestic market (Dunford Citation2017) where permanent urban residents account for 60% of the population, a country with (as a result of painful reforms) a powerful core set of state and collectively owned enterprises and a country that has led recent world economic growth.

As a result of the prioritization of GDP, growth occurred, however, at the cost of serious environmental damage, growing inequalities in income and wealth, growing rural-urban and regional disparities and a rapid increase in mass incidents. Mass incidents increased from 8,700 in 1994 accelerating after 1997 to reach 32,607 in 1999, 74,000 in 2004 and 87,000 in 2005 according to official Public Security Bureau figures (Wei et al. Citation2014, 716; Ministry of Public Security General Office Research Citation2019, 6–7). According to the Annual Report on China’s Rule of Law published by the Institute of Law of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), in the new millennium the number of large mass incidents involving 100 or more people increased exponentially from 2000 to 2012 but then fell sharply in 2013 (quoted in Yang, Zhang, and Liu Citation2020, 681). These incidents were often associated with petitions to central government relating to employment, land acquisition, demolitions, pollution and official conduct.

As already mentioned, after the restoration of national sovereignty and the establishment of a basic industrial system and minimum life guarantees, overall priority was given from 1979 to the development of the productive forces allowing some people and places to get rich first. This phase lasted until 1999. In 1998, the Third Plenary Session of the 15th Central Committee of the CPC (CCCPC) addressed the question of agriculture and the three rural problems of agriculture, farmers and the countryside. This discussion opened the way to a succession of reforms for common prosperity in rural areas to grant farmers secure rights to contracted land and use rights transfer, to improve infrastructure and public services, to establish a new socialist countryside by 2010, and from 2003 to introduce a New Rural Co-operative Medical System and minimum life guarantees.Footnote5

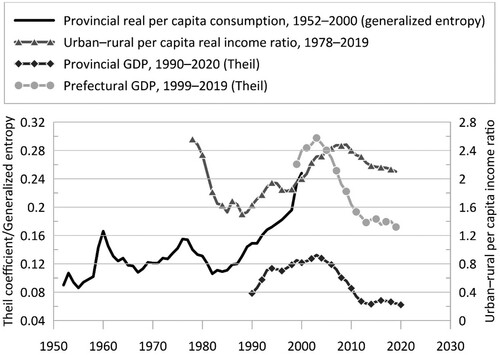

In 1999, China’s western development was set in motion. The aims were to expand domestic demand and drive economic growth in the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis and to contribute to “common prosperity.”Footnote6 These measures were followed by measures to support Northeast and Central China. In 2000 to 2007, central government financial transfers reaching nearly 1.5 trillion yuan and national debt, budgetary and departmental construction funds in excess of 730 billion yuan were allocated to the West.Footnote7 In subsequent years regional gaps (with the exception of Northeast China) started to close (see ).

Figure 1. Provincial, prefectural and rural-urban inequalities (1952–2020). Sources: Elaborated from national and provincial statistical yearbooks.Footnote27

In 2013–2015, China’s new leadership adopted a new eight-year targeted poverty alleviation campaign to identify poverty households and lift them out of poverty (Dunford, Gao, and Li Citation2020). This campaign enabled the CPC to meet its first centenary target of ending extreme poverty by 2020. In the 5th Plenary of the 18th CCCPC in 2015, a strong emphasis was placed on shared development and common prosperity.Footnote8 At the opening of the 19th National Congress of the CPC, President Xi Jinping announced that the principal contradiction was no longer “the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people versus backward social production” identified in 1981 but “the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life.” And in January 2021, at a seminar for provincial and ministerial level officials on the guiding principles of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th CCCPC, Xi Jinping said:

At the Fifth Plenary Session, I underscored five characteristics in particular. China’s modernization must cover a massive population, lead to common prosperity, deliver both material and cultural-ethical progress, promote harmony between humanity and nature, and proceed along a path of peaceful development.

Realizing common prosperity is more than an economic goal. It is a major political issue that bears on our Party's governance foundation. We cannot allow the gap between the rich and the poor to continue growing—for the poor to keep getting poorer while the rich continue growing richer. We cannot permit the wealth gap to become an unbridgeable gulf. Of course, common prosperity should be realized in a gradual way that gives full consideration to what is necessary and what is possible and adheres to the laws governing social and economic development. At the same time, however, we cannot afford to just sit around and wait. We must be proactive about narrowing the gaps between regions, between urban and rural areas, and between rich and poor people. We should promote all-around social progress and well-rounded personal development, and advocate social fairness and justice, so that our people enjoy the fruits of development in a fairer way. (Xi Citation2021)

3. The Growth in Inequalities

In 2019, China’s GNI per capita (Atlas method) reached US$ 10,390, making it an upper middle-income country. In Japan and the US, it reached US$ 41,580 and US$ 65,910, respectively.Footnote9 China’s growth was fast, but growth rates and starting points varied, generating excessive disparities in wealth and income. These disparities increased from the start of reform and opening-up in 1979 (or the mid-1980s in the case of rural-urban disparities) until well into the new millennium.

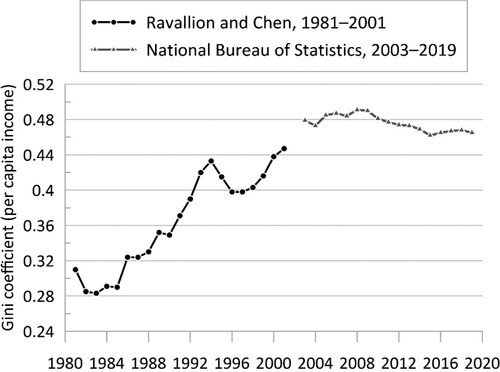

Inter-provincial and rural-urban inequalities declined in the early 1980s, but subsequently increased, especially from the early 1990s until the Western financial crisis when they started to decline (), although they remained high. At present, China’s middle-income groups account for about 30% of the total population. The proportion of low-income groups is still large. In May 2020, Premier Li Keqiang announced that 600 million people were making less than 1,000 yuan per month (US$ 153), although the country’s average annual disposable income per capita stood at 30,000 yuan. The income Gini coefficient increased from under 0.3 in the early 1980s to 0.49 in 2008 after which it declined slowly (Ravallion and Chen Citation2004; Sicular et al. Citation2020, 18). In 2019, it stood at 0.465 (). World Bank estimates are lower, with an estimate of 0.385 in 2016 (0.462 according to the National Bureau of StatisticsFootnote10) compared with 0.414 in the United States (US) in 2018 and 0.329 in Japan in 2013. In the case of wealth, China’s Gini coefficient increased very strongly from 0.450 in 1995 to 0.720 in 2013 (according to the China Family Panel Studies at the Peking UniversityFootnote11). In 2020, it stood at 0.704 compared with 0.850 in the US and 0.644 in Japan (Credit Suisse Citation2021; see also Ge Citation2021), while recent evidence points to a large increase in wealth inequality since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although almost all real incomes have increased overall since 1979 (but not in all sub-periods), common prosperity seems far off and presents an arduous and complicated task that will be promoted in a gradual and progressive manner.

Figure 2. China’s income inequality (1981–2019). Sources: China Statistical Yearbooks Database (1981–2021);Footnote28 Ravallion and Chen (Citation2004, 46).

The rich are predominantly private entrepreneurs whose wealth derives from privatization and the development of private industry, property development and finance. The rest are mainly superstars in the realm of media and entertainment. Generally speaking, the richer they are, the more likely they are to make money.

As already mentioned, the incomes of low income groups have increased overall and the size of low-income groups has declined. The income and wealth gaps between low income groups and the rich are however very large and have increased. These gaps are therefore relative. But relative differences matter a great deal for several reasons. On the one hand, an increase in real wages as a result of an increase in the stock of society’s wealth may involve a relative decline in wages as a share of society’s total wealth. On the other, as Marx pointed out in Wage Labour and Capital:

A noticeable increase in wages presupposes a rapid growth of productive capital. The rapid growth of productive capital brings about an equally rapid growth of wealth, luxury, social wants, social enjoyments. Thus, although the enjoyments of the worker have risen, the social satisfaction that they give has fallen in comparison with the increased enjoyments of the capitalist, which are inaccessible to the worker, in comparison with the state of development of society in general. Our desires and pleasures spring from society; we measure them, therefore, by society and not by the objects which serve for their satisfaction. Because they are of a social nature, they are of a relative nature. (Marx [Citation1847] Citation1975, 33)

In the immediately preceding paragraph, Marx had provided an illustration which anticipates and encapsulates the notion of common prosperity:

A house may be large or small; as long as the surrounding houses are equally small it satisfies all social demands for a dwelling. But let a palace arise beside the little house, and it shrinks from a little house to a hut. The little house shows now that its owner has only very slight or no demands to make; and however high it may shoot up in the course of civilization, if the neighbouring palace grows to an equal or even greater extent, the occupant of the relatively small house will feel more and more uncomfortable, dissatisfied and cramped within its four walls. (Marx [Citation1847] Citation1975, 33)

To address this issue and move in the direction of common prosperity, China plans to make major efforts to increase the share of household income in total national income, increase the share of the compensation of labor in the primary distribution of income, increase the income of low income groups, expand the share of middle income earners, and address excessively high incomes, reversing the excessive widening of income and wealth gaps as quickly as possible. More attention will also be paid to secondary and tertiary redistribution and decommodification with measures relating to taxation, health insurance, social security, affordable housing, Hukou (household registration) reform, poverty alleviation, rural vitalization and charity. Other measures will address the structure of the economy dealing with monopolies and externalities, orienting investment towards real productive sectors, expanding consumer demand and improving people’s livelihoods.

4. Causes and Measures

Addressing the wealth and income gaps and promoting common prosperity involves identifying causes and reforms that deal effectively with these causes. As already explained, the main driver of polarization is the development of the private sector where substantial private wealth accumulates at one pole and many workers are subject to insecure employment and wages and inadequate public service access at the other. In the private sector, wages and social protection are usually far lower than in the state and collective sector: in 2015, the average wage was 65% higher in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) than in private enterprises. In the private sector the average wage was one-third less than the average disposable income of an employee in an urban household (Qi and Kotz Citation2020, 10).

The distribution and ownership of material and financial conditions of production and exchange (mode of production) is the main determinant of the primary distribution of income. To argue that the initial distribution should reflect efficiency and not equity and that subsequent redistribution should address equity separates production from distribution and sanctions large inequalities as inequalities are fundamentally determined by an unequal, unfair and inequitable distribution of assets. As a result, addressing the ownership of assets and limiting the marketization of assets are vital. The significance of this issue was highlighted by an estimate mentioned in 2020 by a deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission when he announced at a State Council press conference that China’s state assets accumulated, as a result of massive infrastructure investment, stood at 1,300 trillion yuan.Footnote12

In this respect, an important suggestion was recently made by Enfu Cheng (Citation2021), namely, China should conduct experiments with the implementation of a national dividend for every citizen deriving from the surplus operating income earned on state-owned assets. Macao has already conducted an operation of this kind paying a “red envelope” of 9,000 yuan to each permanent resident and 5,400 to non-permanent residents in 2014, having started to make such payments in 2008.Footnote13 A dividend would provide a new income stream that reflects the ownership of collective and state assets by all of the population and is subject to the same market attributes and governance rules as other economic subjects.

Alongside ownership relations, corruption, monopolies, superstar phenomena and markets have been identified as causes of inequality. These factors are not, however, the root cause of social polarization. In the case of celebrity phenomena, incomes are excessive, but these incomes are not a cause of the existence of large numbers of low income people.

In the case of corruption, President Xi Jinping has launched a major anti-corruption campaign. In 2018, the government organized a three-year campaign to “combat organized crime and root out local Mafia.” The aim was to address rent-seeking relationships between government and business, and it resulted in the eradication of 3,644 organizations and disrupted interest consolidation mechanisms. Addressing the corruption of government officials plays a vital role in establishing public trust in government. Although some people did secretly enrich themselves, corruption is not the root cause of wealth and income divides: it does not adequately explain the wealth of the rich, nor does it explain the large size and limited wealth of low income groups (Wei Citation2021).

Official corruption did play an indirect role: in some cases, officials and managers acted corruptly in enabling economic initiatives and permitted the misappropriation of state assets through, for example, questionable management buyouts and restructuring of state-owned and collective enterprises. These privatizations made some people very rich almost overnight and saw many workers laid off (Wei Citation2021). In each year from 1982 until 1992, state assets worth 50 billion yuan were transferred to the private sector. In the 1990s, this figure stood at 500 billion yuan. According to a 2007 survey, at least one-third of the private capital stock of 7 trillion yuan was transferred from the state and collective sector (Wei Citation2021) with significant layoffs and changes in employment conditions for their workers. These layoffs contributed directly to the existence of large numbers of people in low income groups. At the end of the 1990s and in the new millennium, opposition to privatization intensified. As a result, from 2004 management buyouts of large SOEs came to an end, with much stricter rules applied to acquisitions of smaller SOEs. In 2005, a draft property law was deferred for revision (Blanchette Citation2019, chapter 2).

In social terms, these reforms were extremely painful. As already mentioned, they led to the layoff and reduced social protection of millions of workers. The outcome was, however, the establishment of a smaller but highly competitive set of collective and state-owned enterprises that in 2020 accounted for more than one-third of capital investment (not far short of the private sector). Indeed, since 2003, China’s central SOEs have experienced a significant rise and expansion under the leadership of the State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), and in the context of employing market competition as an instrument of a developmental state strategy (Chen Citation2017).

The existence of monopolies can also affect the distribution of income. Monopolies are, however, not the root cause of income and wealth gaps. In 2012, 90% of state and collective enterprises were in competitive sectors. In the case of natural monopolies, SOEs pay high taxes and use profits to fund investment. In each case, the main shareholders are public. In the private sector, the quest for increased private wealth has led to the appearance of a series of problems of which some involve monopolistic practices, but it is ownership rather than monopoly market positions that explains increasing inequality.

In 2012, one of China’s leading neoliberal economists, Weiying Zhang, claimed that in the new millennium, market-oriented reform had been reversed on the grounds that “the state-owned sector advances but the private sector retreats” (see Xiang Citation2020). In the following year, the World Bank and the Development Research Centre of the State Council published a report calling for a set of neoliberal economic reforms: redefinition of the role of government, a restructuring of state enterprises and banks, development of the private sector and reforms of land, labor and financial markets.

In 2012, however, in dealing with the need for structural economic reform, the 18th CPC National Congress called for consolidating and developing the public sector of the economy.Footnote14 Although the state sector has contracted in the reform era, China still has a large SOE sector and has ruled out further privatization. In addition, it has a state-owned banking system, and the public ownership of land is written into the Constitution (although land is leased and subsequent increases in value are not captured by the state, but by private actors). In 2017, China had more than 150,000 SOEs (Lin et al. Citation2020). In 2015, SOEs accounted for 30.9% of tax income. In the industrial sector, SOEs accounted for 38.8% of revenue (Qi and Kotz Citation2020, 1). In the last few years, SOEs and collective enterprises accounted for more than 35% of aggregate fixed asset investment, with the private sector accounting for a similar share. SOEs occupy commanding heights of the economy, create economy-wide externalities, invest in essential capital intensive industries, adopt a high road approach to employment, absorb labor to maintain social stability, undertake countercyclical investments and serve to limit foreign control. At the same time, their existence limits the accumulation of private assets and provides opportunities to reduce social polarization and contribute to common prosperity.

5. Common Prosperity in the New Era

On August 29, 2021, Guangman Li’s Ice Point Commentary entitled “Everyone Can Feel a Critical Change is Taking Place” was republished across Chinese state-owned media outlets. In it he declared,

The capital market will no longer become a paradise for capitalists to get rich overnight. … The cultural market will no longer be a paradise for sissy (effeminate) stars, and news and public opinion will no longer be in a position worshiping Western culture.Footnote15

In the last few years, the Chinese government has pursued the common prosperity agenda with a series of striking reforms. These reforms amount to a major crackdown on tech, platform economy and other monopolies (online food delivery, car and truck hailing, and recruitment), on real estate (red lines controlling debt and associated risks)Footnote16 and financial capital (shadow banking), on owners seeking to get rich by going public on foreign stock markets and on wealthy elites.Footnote17 Housing and education were other targets with the latter said to have been “hijacked” by capital. As a result of liberalization, private initiatives and serious regulatory deficiencies or oversights, the costs of housing, education and health have exploded, creating three mountains whose rising costs and declining affordability crowd out other household expenditures and limit the domestic side of dual circulation. A consequence of the large increase in the cost of living is an increase also in the cost of raising children which acts as a serious disincentive to couples giving birth to the three children the government hopes to see them raise. Measures were directed at property development and management, at private finance and speculation, not only to reduce costs but also to reduce the risks of real estate and financial market crises. Other measures placed limits on increases in market rents and steps may be taken to deal with unoccupied housing. In May 2021, the Chinese Internet finance, banking and payment clearance associations banned the use of crypto currencies (not the official digital yuan), about which it has been concerned since 2013. In June 2021, it finally shuttered crypto-mining operations that were present in energy-rich provinces. In addition, some state-linked or very large corporations are allowed to teeter towards default.

In December 2020, at the Central Economic Work Conference, Xi Jinping tasked government agencies with curbing the “disorderly expansion of capital,” along with other important economic tasks including strengthening technological innovation, increasing domestic demand and moving in the direction of carbon neutrality and ecological civilization. In his words, “lucid waters and lush mountains are as precious as mountains of silver and gold.”Footnote18

To “prevent the disorderly expansion of capital,” China started to address the power of tech companies with a storm of regulation. This regulation was clearly already in preparation when in October 2020, Alibaba Group Holding founder Jack Ma criticized the Chinese government for excessive regulation and condemned the capital requirements imposed on financial institutions. Ma’s Ant Group initial public offering (IPO) on the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock markets was halted by the government authorities. As part of the Alibaba multinational e-commerce Group, Ant Group uses mobile Internet, big data and cloud computing to discover and provide highly leveraged micro financial services at high interest rates to vulnerable people, creating a growing mountain of debt. Alibaba Group accounted for less than 2% of the funds Ant Group lends. All in all Alibaba poses risks that are too large (Tsui, He, and Yan Citation2021). Alibaba, Tencent Holdings and Baidu have all been fined for anti-competitive practices (exclusivity arrangements, for example). New draft rules for overseeing Big Tech have been published, including regulations concerning antitrust and personal data protection (Personal Information Protection Law) and national data security (Data Security Law). New video gaming rules that limit playing time for people under 18 years of age to just three hours per week will adversely affect the video games sector. These measures are a repudiation of the imported individualistic cultural values and addictions of Western society and are designed to encourage science, technology, innovation and education, win the next technological race and alter the profile of the economy in favor of strategically important and socially useful industries. In the specific case of these industries, measures are designed to address the threat their dominance poses to competition, privacy and, through their Fintech empires, financial stability. These measures also deal with their non-compliance with regulation. For example, companies did not report acquisitions, while the use of variable interest equity (VIE) that allowed largely unsupervised overseas initial public offerings (IPOs) was questioned. VIE is a structure in which Chinese companies raise massive amounts of capital through offshore share issues which involve the sale of a majority of shares (in shell companies registered in tax havens) yet maintain a controlling interest. These companies can then invest in China, circumventing restrictions on the entry of foreign capital.Footnote19

On June 30, DiDi Global, a Chinese ride-hailing company, raised $4.4 billion on its debut on the New York Stock Exchange. On July 2, 2021, it was accused by the Cyberspace Administration of China of illegally collecting users’ personal data and not adequately ensuring data security. Its app was removed from phones in the mainland of China, and it will incur a large fine. In less than one month, it lost about $29 billion in market value. In principle because of its VIE structure, DiDi, which is incorporated in the Cayman Islands, did not need Chinese government approval to list in New York. However, the cyber security administration was concerned about the sensitivity of its data and suggested Didi postpone the floatation. DiDi ignored the warning.

On July 24, 2021, the General Office of the CCCPC and the General Office of the State Council jointly released the “Guidelines for Further Easing the Burden of Excessive Homework and Off-campus Tutoring for Students at the Stage of Compulsory Education,” subsequently called the dual alleviation policy. The guidelines included some thirty measures to stop after school, weekend, national holiday and school vacation courses that were expected to earn private companies US$ 183 billion per year by 2023. After declaring that education had been highjacked by capital, it decided to stop licensing new tutorial centers and course providers for elementary and high school students, while existing ones will face stricter reviews and be regulated as not-for-profit entities whose programs must be approved by the government. No foreign capital can invest in them (as had happened as a result of the speculative capitalization of Chinese education companies on the US stock market via VIE arrangements). These reforms follow a new education law that limits private sector involvement in core education and disallows the use of foreign education materials.Footnote20

These measures will reduce the enormous pressures on young people in a highly competitive education system oriented towards performance in the gaokao (college entrance examinations) which drive entry into China’s top universities and powerfully shape career prospects. The aims are to improve the school-life balance for children and their families, level a playing field on which the children of low-income and rural households were seriously disadvantaged, reduce financial pressures on parents faced with exorbitant fees for private lessons (US$ 60–220 per hour in Beijing) which absorb a very large share of their incomes and restrict “encroachment” on public education including the poaching of teachers as part-time private sector tutors. The new measures will put an end to the extraordinary profitability of a $180 billion industry and decimated stock values. When the news of the measures leaked out, shares in New Oriental Education & Technology Group Inc. plunged by a record 47% in Hong Kong, while those of Koolearn Technology Holding Ltd. tumbled 33% and those of China Maple Leaf Educational Systems Ltd. by 10%. These losses spilled into other technology, healthcare and property sectors where regulation was expected to tighten. All in all these events erased $769 billion in value from US-listed Chinese stocks in just five months.Footnote21

In September the government published a set of regulations on the implementation of a law on the promotion of private education.Footnote22 The aim was to reign in private education that had expanded rapidly from 2003 and prevent the use of public resources by private entrepreneurs to benefit well-off groups, while strengthening China’s public education system and ensuring that education serves China’s ideals of equity and the common good.

On July 26, China’s State Administration for Market Regulation announced that food delivery firms will be required to guarantee the couriers their platforms employ a minimum income that is in excess of the minimum salary, relax delivery deadlines, strengthen traffic safety education and ensure that couriers join social insurance programs. After this announcement, the shares in Meituan, a food delivery giant, declined by 26%. China’s market regulator subsequently levied a 3.44 billion yuan ($533 million) fine on Meituan for anti-competitive practices (3% of the company’s domestic sales for 2020 compared with a ceiling of 10% under China’s Anti-Monopoly Law). Meituan was also required to return 1.29 billion yuan of merchant deposits obtained as part of exclusivity agreements considered unlawful.

At the end of August 2021, China’s Supreme People’s Court and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security issued a lengthy condemnation of “996,” the practice of working from 9 in the morning until 9 in the evening six days per week (described in 2019 as a “huge blessing” by Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma). This practice is said to be common among the country’s technology companies, startups and other private businesses. The document stated that “adhering to the national working hour system is the legal obligation of employers.” In January 2021, e-commerce giant, Pinduoduo, was accused of over-working its employees after two died unexpectedly.

In its report on China’s financial stability, the People’s Bank of China stated that it had comprehensively cleaned up the financial order as well as dealing with a number of other issues including high risk institutions, the risks of shadow banking, credit risks and the need for a system to prevent and manage risks and curb an excessive macro leverage ratio (People’s Bank of China Citation2021, 20–26). The China Securities Regulatory Commission’s Chief Executive Officer, Huiman Yi, recently announced resolute action to make private equity funds return to “the fundamental direction of private equity positioning, and support entrepreneurial innovation and strictly regulate the operation of all links in the entire chain of equity investment management.”Footnote23

In July and August 2021, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development pledged to stabilize property prices, and started to cap housing rents in cities, saying that they should not rise by more than 5% per year. In 2017 at the 19th Party Congress, Xi Jinping announced that “houses are for living in and not for speculation.” In subsequent years, steps have been taken to control house prices and increase government-subsidized rental housing. Other measures may address the existence of non-occupied homes. Credit availability along with a limited supply of new residential land has kept up the price of urban land. The initial sale of leases is a major source of local government revenue, but subsequent increases in land values are not captured, while low-cost construction land is provided to companies to drive local economic development. The government has also required local authorities to scrutinize closely all the activities of developers from the arrangement of finance to the transfer of ownership titles.

In early September 2021, the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) issued a document calling for strengthening of the management of cultural and entertainment programs and personnel, and giving specific guidance on what the entertainment industry can and cannot do. This step followed a series of celebrity tax and other scandals and the removal of TV shows and programs featuring celebrities caught up in them.Footnote24

Centred on continuing steady increases in income and high quality development, common prosperity aims to increase the size of middle income groups, raise the earnings of low income groups and reduce excessive incomes in a three-stage income distribution and tax system. The first stage involves an increase in primary incomes. The goals included an increase in the wage share (seen as the main component of income), increased property income (equity transfer and dividends) from rural homesteads, contracted land, rural assets and collective land used for construction, enriched capital market income, an improved environment for urban self-employed whose incomes are predominantly low and whose work situation is unstable, and employee stock ownership.

The second is the tax and social security system. New taxes will be imposed on property, inheritance and capital gains and on high-income groups. Excessive incomes will be reduced, illicit incomes prohibited and monopoly rents reduced. The capping of SOE executives’ salaries will be refined. As for social security, the aim is equitable access to improved public services (with significant increases in the quantity, quality and accessibility of public provision of elderly care, health, pre-school and school education), making use of information technologies. Universal social protection (while dependent on high employment rates) will narrow gaps in the primary distribution and share the fruits of growth, while a decline in savings rates will increase expenditure, reinforcing domestic circulation.

The third is an improvement of mechanisms and preferential policies that will encourage high-income groups and enterprises to give back some of what they have gained from society in the shape of voluntary gifts and charitable donations. Government documents have referred to tertiary distribution since at least the 1990s, but the importance attached to it has increased, with an emphasis on government-recognized charity, social assistance organizations and government projects (to help elderly, lonely, sick, disabled and poverty-afflicted people), as has the attention paid to it.Footnote25

6. Conclusions

China’s development path is evolving. In a country accounting for nearly one-fifth of the world’s population, the aim of the CPC and the Chinese government is to promote common prosperity, while making progress in material terms (indigenous innovation, industrial upgrading, and dual circulation articulating an expanding domestic market with international markets for exports and imports), and also in cultural, ethical and spiritual terms. At the same time, they aim to promote harmony between humanity and nature (ecological civilization).

Strikingly Western economic experts have claimed that China’s decision to crack down on finance, property and private tech is, in growth terms, suicidal. A system involving market-driven state and collective ownership, planning and investment with a wide range of co-existing enterprise types is considered incapable of performing as well as one centered on profit-driven private capital and free markets for resources and assets of all kinds. If one simply compares the past and current growth records of China (with China growing at some 6% per year and the US and EU at less than 1% recently, with little prospect of reaching much more than 2% for a sustained period of time as well as the dubiousness of the measured contributions of real estate and finance to G7 growth), this claim is quite astonishing.Footnote26 Almost certainly it reflects the mistaken view that China’s growth was driven by its private sector and the extraordinary view that unregulated tech, finance and property sectors make major contributions to human prosperity. In China as in the G7 private sector, profitability has declined, explaining in part why speculation and unproductive investment increased. The growth of labor productivity and investment in the real economy, innovation, new infrastructure and socially useful public services are what China’s economy can deliver, whereas G7 economies as currently constituted cannot (Dunford Citation2021).

The socialist public-owned economy with the state-owned economy as its core is the necessary institutional arrangement. The socialist public-owned economy is not only the necessary condition and foundation to eliminate polarization and realize common prosperity, but also the institutional guarantee of rapid development of the productive forces as China’s investment share testifies; in Western countries, investment has stagnated due to a decline in private profitability. In order to realize fairness and justice and common prosperity, China will adhere to and improve its economic system which is led by a state-owned economy that exists alongside a variety of other types of property, including foreign and private capital and widespread, strongly encouraged and very important innovative micro entrepreneurship. In a situation in which disorderly capital accumulation, monopolies and speculation will be brought under control, the rich will be able to remain rich, but the poor will not continue to be poor.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Bing Qi for providing some of the Chinese language material. He also wishes to thank the editors of the journal for their helpful advice and Zixu Liu for his very careful editing of the manuscript. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Dunford

Michael Dunford is Emeritus Professor at the School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, Visiting Professor at the Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Managing Editor of Area Development and Policy. He graduated with BS in Geography and MS in Quantitative Economics from the University of Bristol. His interests are in global development (at multiple geographical scales and with special reference to Europe and the western world, China and Eurasia and the wider world system) drawing on materialist conceptions of history and geography and on theories of uneven and combined development, regulation and geopolitical economy.

Notes

1 In some cases, it is claimed that China is an example of state capitalism. Without entering this controversy, it is important to note as Lenin emphasized that state capitalism under capitalism and socialism differ and that the former is a “step towards socialism” (Lenin [Citation1921] Citation1983), while Mao (and indeed Stalin) spoke of a need to “develop socialist commodity production and commodity exchange.” The implication is that commodity production under socialism and capitalism differ. Some of the words of Mao are particularly significant. In 1975, he said: “At the moment, our country employs a commodity system, and the wage system is unequal as well, what with the eight-grade wage system, etc. Such things can only be restricted under the dictatorship of the proletariat” (Mao, cited in Coderre Citation2019, 34). In this light one should understand the Deng era “Constitution of 1982” and its adherence to four cardinal principles, namely, adherence to socialist road, to the people’s democratic dictatorship, to the leadership by the Communist Party of China and to Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong thought.

2 Marx and Engels ([Citation1845] Citation1968) pointed out,

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

3 Jiang (Citation2002) said,

We should give priority to efficiency with due consideration to fairness, earnestly implementing the distribution policy while advocating the spirit of devotion and guarding against an excessive disparity in income while opposing equalitarianism. In primary distribution, we should pay more attention to efficiency, bringing the market forces into play and encouraging part of the people to become rich first through honest labor and lawful operations. In redistribution, we should pay more attention to fairness and strengthen the function of the government in regulating income distribution to narrow the gap if it is too wide. We should standardize the order of income distribution, properly regulate the excessively high income of some monopoly industries and outlaw illegal gains. Bearing in mind the objective of common prosperity, we should try to raise the proportion of the middle-income group and increase the income of the low-income group.

4 In official documents reference is made to “the income distribution system with distribution according to labor as the main body and multiple coexisting distribution modes, focusing on protecting labor income and perfecting the mechanism of factor participation in distribution” (in Chinese; see http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-06/10/content_5616833.htm). Alongside wages, the rents, interest, profits and capital gains of landowners/possessors, capital owners and owners of financial wealth co-exist.

5 See the Database of CPC National Congresses (in Chinese). http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64162/64168/64568/65402/4429278.html.

6 See “CPC Central Committee’s Work Meeting in 1999” (in Chinese). http://www.gov.cn/test/2008-12/05/content_1168875.htm.

7 See “1999: The Great Western Development” (in Chinese). http://www.prcfe.com/web/meyw/2009-10/12/content_564747.htm.

8 See “The Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee Convened in Beijing” (in Chinese). http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/1030/c64094-27756155.html.

9 See the World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GNP.MKTP.PP.CD&country=.

10 Data available at: http://tongji.oversea.cnki.net/oversea/engnavi/navidefault.aspx.

11 This data comes from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) of the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University in 2021, which is funded by Peking University and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and maintained by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm?CSRFT=XMK9-S7AK-ZNYV-4YIF-5YSC-W1U0-MPJ8-RJDG.

12 See “China’s Total Assets Exceed 1300 Trillion Yuan” (in Chinese).” https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1667568756159490784&wfr=spider&for=pc.

13 See “Macao Reissued a Red Packet for All People: 9,000 Yuan for Residents and 5,400 Yuan for Non-permanent Residents” (in Chinese). https://news.qq.com/a/20140523/018162.htm?tu_biz=v1_region.

14 In the “Report to the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China,” Hu Jintao stated,

The underlying issue we face in economic structural reform is how to strike a balance between the role of the government and that of the market, and we should follow more closely the rules of the market and better play the role of the government. We should unwaveringly consolidate and develop the public sector of the economy; allow public ownership to take diverse forms; deepen reform of state-owned enterprises; improve the mechanisms for managing all types of state assets; and invest more of state capital in major industries and key fields that comprise the lifeline of the economy and are vital to national security. We should thus steadily enhance the vitality of the state-owned sector of the economy and its capacity to leverage and influence the economy. (see http://language.chinadaily.com.cn/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-10/16/content_32684880_5.htm)

16 A pilot affecting twelve large property developers subjects their debt to three red lines: a liability-to-presale-asset ratio of no more than 70%; a net debt-to-equity ratio of under 100%; and cash holdings at least equal to short-term debt.

17 These measures came on top of a significant tightening and centralization of control over outward foreign direct investment in late 2016 and 2017 to stem capital outflows and the rapid depletion of China’s foreign currency reserves (Wang and Gao Citation2019).

18 See Xinhua Net, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-08/16/c_139294561.htm.

19 In sectors where China restricts or prohibits foreign participation, Chinese companies set up shell companies in a tax haven such as the Cayman Islands with a similar name. The original company sets up agreements that give the shell company a claim on the profits and control over the assets of the original company. The shell company then registers on the New York Stock Exchange and sells shares to investors under the name of the Chinese company. Although these shares do not entail any company ownership claims, the Chinese company can raise international capital, and international investors secure a share of the Chinese company’s profits. The Chinese government would prefer that capital is raised on domestic capital markets where it can also ensure that it goes to industries it wants to see develop and avoids areas it deems a threat to the common good.

20 See “More Regulatory Clarity after China Bans For-Profit Tutoring in Core Education.” https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-bans-for-profit-tutoring-in-core-education-releases-guidelines-online-businesses/.

21 See “Wipeout: China Stocks in US Suffer Biggest 2-Day Loss since 2008.” Al Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/7/26/wipeout-china-stocks-in-us-suffer-biggest-2-day-loss-since-2008.

22 See “Regulations for the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of Private Education” (State Council Decree No. 741). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-05/14/content_5606463.htm.

24 See “China Orders Showbiz to Ban Unpatriotic and Unethical Stars.” Nikkei Asia, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Caixin/China-orders-showbiz-to-ban-unpatriotic-and-unethical-stars.

25 In August 2021, tech giant Tencent Holdings donated US$7.7 billion towards “common prosperity” to support low-income groups, rural revitalization, healthcare and education after having in April 2021 committed US$7.7 billion towards “sustainable innovations for social value.” Nasdaq-listed e-commerce website Pinduoduo announced that it would donate its second-quarter profit and all future earnings until the sum reached 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) for China’s agricultural development.

26 In G7 countries, the rate of growth of productivity in real sectors has almost progressively declined. In liberal market economics, it is argued that capital is allocated efficiently to activities according to the marginal efficiency of capital (Keynes) or marginal productivity (neoclassics). Yet the marginal efficiency of capital in which capitalists are interested has declined, and with it the rates of real productivity growth and investment also declined (see also Wei Citation2021).

27 For national statistical yearbooks, see http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/Statisticaldata/AnnualData/. National data are also available at https://data.stats.gov.cn/english/. For provincial statistical yearbooks, see http://tongji.oversea.cnki.net/oversea/engnavi/navidefault.aspx http://tongji.oversea.cnki.net/oversea/engnavi/navidefault.aspx.

28 The China Statistical Yearbooks Database is available at: http://tongji.oversea.cnki.net/oversea/engnavi/navidefault.aspx.

References

- Blanchette, J. 2019. China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cao, Y. 2021. “New Ideas Enrich and Expand the Marxist Theory of Common Prosperity.” [In Chinese.] Governance, no. 30: 3–7.

- Chen, Z. 2017. “Governing through the Market: SASAC and the Resurgence of Central State-Owned Enterprises in China.” PhD diss., University of Birmingham. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/8381/3/Chen_Zhiting18PhD.pdf.

- Cheng, E. 2020. “Market’s Decisive Role and the Role of the Government.” In Delving into the Issues of the Chinese Economy and the World by Marxist Economists, edited by E. Cheng, 103–120. Istanbul: Canut International Publishers.

- Cheng, E. 2021. “Cheng Enfu Discusses Common Prosperity: Implement a National Dividend, Raise Personal Tax Thresholds.” [In Chinese.] Accessed September 7. https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1710209745426043060&wfr=spider&for=pc.

- Coderre, L. 2019. “A Necessary Evil: Conceptualizing the Socialist Commodity under Mao.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 61 (1): 23–49.

- Credit Suisse. 2021. “Global Wealth Report 2021.” https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/global-wealth-report.html.

- Deng, X. (1979) 2014. “We Can Develop a Market Economy under Socialism.” In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. II, 169–173. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

- Deng, X. (1985) 2014a. “There Is No Fundamental Contradiction between Socialism and a Market Economy.” In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. III, 100–102. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

- Deng, X. (1985) 2014b. “Unity Dpends on Ideals and Discipline.” In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. III, 78–79. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

- Deng, X. 1999. Research on the Theory of Common Prosperity. [In Chinese.]. Beijing: China Federation of Industry and Commerce Press.

- Dunford, M. 1990. “Theories of Regulation.” Environment and Planning D: Society & Space 8 (3): 297–321.

- Dunford, M. 2017. “The Rise of China and Its Implications for Economics and Other Developing Countries: The Significance of the Chinese Social Model.” Area Development and Policy 2 (2): 124–129.

- Dunford, M. 2021. “Global Reset: The Role of Investment, Profitability and Imperial Dynamics as Drivers of the Rise and Relative Decline of the United States, 1929–2019.” World Review of Political Economy 12 (1): 50–85.

- Dunford, M., B. Gao, and W. Li. 2020. “Who, Where and Why? Characterizing China’s Rural Population and Residual Rural Poverty.” Area Development and Policy 5 (1): 89–118.

- Ge, D. 2021. “Theoretical Implications and Empirical Indices of Common Prosperity in the New Era.” [In Chinese.] Governance, no. 30: 8–11.

- Jiang, Z. 2002. “Build a Well-Off Society in an All-Round Way and Create a New Situation in Building Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: Report at the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.” Accessed August 24, 2021. http://en.people.cn/200211/18/eng20021118_106984.shtml.

- Lenin, V. I. (1921) 1983. On State Capitalism during the Transition to Socialism. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Lin, K., X. Lu, J. Zhang, and Y. Zheng. 2020. “State-Owned Enterprises in China: A Review of 40 Years of Research and Practice.” China Journal of Accounting Research 13 (1): 31–55.

- Marx, K. (1847) 1975. Wage Labour and Capital. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Marx, K., and F. Engels. (1845) 1968. The German Ideology. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Ministry of Public Security General Office Research Department. 2019. “Comprehensive Research Report on China’s Current Issue of Mass Incidents Caused by Conflicts among the People.” Chinese Law and Government 51 (1): 6–27.

- People’s Bank of China. 2021. China Financial Stability Report 2020. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688235/3688414/3710021/3982927/4154143/index.html.

- Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated by A. Goldhammer. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Qi, H., and D. M. Kotz. 2020. “The Impact of State-Owned Enterprises on China’s Economic Growth.” Review of Radical Political Economics 52 (1): 96–114.

- Ravallion, M., and S. Chen. 2004. “China’s (Uneven) Progress against Poverty.” World Bank policy research working paper, no. 3408, World Bank, Washington DC. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/14241/WPS3408.pdf;sequence=1.

- Sicular, T., S. Li, X. Yue, and H. Sato, eds. 2020. Changing Trends in China's Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The World Bank. 1981. World Development Report, 1981. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The World Bank. 1983. The Economy, Statistical System, and Basic Data. Vol. 1 of China: Socialist Economic Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Acessed August 24, 2021. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/192611468769173749/pdf/multi-page.pdf.

- Tsui, S., Z. He, and X. Yan. 2021. “Legacies of Definancialization and Defending Real Economy in China.” Monthly Review 73 (3). Accessed July 7, 2021. https://monthlyreview.org/2021/07/01/legacies-of-definancialization-and-defending-real-economy-in-china/.

- Wang, B., and K. Gao. 2019. “Forty Years Development of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Retrospect and the Challenges Ahead.” China and World Economy 27 (3): 1–24.

- Wei, X. 2021. “Adhering to and Improving the Basic System Based on or Dominated by Public Ownership to Achieve Common Prosperity.” [In Chinese.] Accessed August 24, 2021. http://www.szhgh.com/Article/news/comments/2021-08-24/277297.html.

- Wei, J., L. Zhou, Y. Wei, and D. Zhao. 2014. “Collective Behavior in Mass Incidents: A Study of Contemporary China.” Journal of Contemporary China 23 (88): 715–735.

- Xi, J. 2017. “Work Together to Build a Community of Shared Future for Mankind: Keynote Speech Delivered at the United Nations Office, Geneva.” http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-01/19/c_135994707.htm.

- Xi, J. 2021. “Understanding the New Development Stage, Applying the New Development Philosophy, and Creating a New Development Dynamic.” Accessed July 22, 2021. https://www.en84.com/11770.html.

- Xiang, Q. 2020. “Debate on the Two Views in the Economic Field Continues.” In Delving into the Issues of the Chinese Economy and the World by Marxist Economists, edited by E. Cheng, 129–144. Istanbul: Canut International Publishers.

- Yang, J., C. Zhang, and K. Liu. 2020. “Income Inequality and Civil Disorder: Evidence from China.” Journal of Contemporary China 29 (125): 680–697.