ABSTRACT

The military conflict between Russia and Ukraine that is also a conflict between Russia and the United States and its NATO allies is fundamentally a result of two interconnected factors. The first is the threat to the security of Russia posed by the enlargement of NATO in violation of commitments made at the time of the reunification of Germany and of the principle of indivisible security. The second is deeply rooted internal divisions in Ukraine that were exacerbated by ethnic nationalism and the imposition of divisive national identity that led to demands for a degree of regional autonomy and a civil war that successive governments and external parties did not or did not want to resolve. In these years Ukraine served as an instrument in a US strategy to weaken a strategic rival, prevent Eurasian integration and preserve the unipolar order that had emerged with the collapse of the Soviet Union. On present trends the losers will be Ukraine as it existed until February 2022, Europe and Germany although, depending on the outcome, it may also accelerate the transition to a new multipolar world order.

Let him who wishes weep bitter tears because history moves ahead so perplexingly: two steps forward, one step back. But tears are of no avail. It is necessary according to Spinoza’s advice, not to laugh, not to weep, but to understand. (Trotsky Citation1937)

治国常富,而乱国常贫。是以善为国者,必先富民,然后治之。[zhì guó cháng fù, ér luàn guó cháng pín. shìyǐ shàn wèi guó zhě, bì xiān fùmín, ránhòu zhì zhī—Governance always makes a country rich, chaos often makes a country poor. Meaning whoever governs a country must first enrich the people]. (管仲[Guǎn Zhòng] 645 BC).

Introduction

At the root of the 2022 crisis in Ukraine are two major factors. The first is the eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), although it was accompanied by expansion of the spheres of influence of the European Union (EU), Western-dominated multilateral institutions (International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and Western funded civil society organizations that all sought to integrate Ukraine into a Western orbit. In the case of NATO, eastward expansion was envisaged at least as early as 1993 and started in 1999 effectively extending US control over Europe. The April 2008 Bucharest Summit announcement of potential Ukrainian and Georgian membership, implying increased NATO control over the Black Sea and more neighbours of the Russian Federation (RF), and the post-2014 integration of Ukraine into NATO command structures (Mearsheimer Citation2022) were critical steps. As for the EU, it has since the 1990s played an important role in the expansion of Western interests in a new “Drang nach Osten.”

The second is the ethnic, linguistic, religious, cultural, economic, political and regional differences in Ukraine, of which some had developed over centuries in which different parts of Ukraine were parts of different countries, the rise of ethnic nationalism and the path to civil war that nearly erupted in 2004 and did erupt in 2014 (Mettan Citation2017; Sakwa Citation2015; Cohen Citation2019; Drweski Citation2022b). In the years since 2014, societal divisions were intensified by two factors. The first was eight years of near-continuous and repeated attacks on the civilian population of two Donbass Republics. The second was the refusal of Ukrainian governments and Western powers to implement the Minsk Agreements which called for negotiations between Kyiv and representatives of the two Republics with a view to granting them a degree of autonomy within a unified Ukrainian state. Indeed in June 2022 former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said that the Minsk Agreements “meant nothing” and were signed solely to gain time to “restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces” (Russia Today Citation2022).

This side of the problem is related to the fact that the country that emerged in 1991 was a state, yet it was not a single people or a united nation (Cohen Citation2019). Ukraine had scarcely ever existed as single nation. Once it did, ethnic nationalism drove the definition and imposition of a divisive national identity and economic relationships. This identity reinforced divisions between communities that differed in multiple ways including in relation to the outcome of the Second World War, while all attempts to overcome in a peaceful way these divisions and guarantee “respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion” (United Nations Citation1945, 3; Citation1970, 124) were impeded.

The aim of this article is to document these two aspects of the conflict. The conflict is, however, more than one confined to the territory of Ukraine. Instead, it amounts to a proxy war between the United States (US) and its allies and Russia. This proxy war is designed to weaken and divide it, replace its government, consolidate US leadership over its European allies and reverse and impede the economic integration of Germany with Russia and the rest of Eurasia, as a prelude to a conflict with China (Drweski Citation2022a). At stake is US unipolar planetary leadership (Cheng and Lu Citation2021) and the maintenance of a US rules based economic, political, military and cultural order. Russia, China and other rising powers such as Iran are considered strategic rivals that threaten US “influence, interests, power and values”Footnote1 and, in their advocacy of a multipolar world, US unipolar leadership (Dunford Citation2021b; Dunford and Qi Citation2020).

In challenging Russia, the US aims to advance its principles and values, enhance its power and privileges and continue extracting wealth and income from throughout the globe (via ownership and control of value chains, distribution, intellectual property, international finance, rules of trade and investment and the economic policies of other countries) so as to ensure its relative affluence, while dividing and weakening its rivals.

From a Succession of Borderlands to a Soviet Republic and Ethnic Nationalism in a Multi-ethnic Independent Country

The first problem derives from the way Ukraine emerged from the break-up of the multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-cultural and multi-religious Soviet Union, and the processes of economic, political and cultural disintegration that accelerated once the leaders of three (Russia, Belarus and Ukraine) of the fifteen Soviet Republics signed the Belovezh Accords in a forest park near Minsk on December 8, 1991, withdrawing from the 1922 Union Treaty and establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Overall, 25 million Russians were left outside Russia. In the case of Ukraine not only were there close economic, political and cultural relationships but also millions of family ties and Ukrainian-Russian households with relatives living on opposite sides of what became a national border. Of 48.1 million people in Ukraine in 1989, 37.5 million (72.7%) were Ukrainians; 8.3 million concentrated in the eastern and southern regions were Russians (22.1%). In 2001 the share of ethnic Russians was lower (17.3%). Russian was, however, the native language for 29.6% (Sakwa Citation2015, table 1).

These shares permit the identification of three broad groups occupying different parts of Ukraine and three broad identities (although within them there are economic and political differences): Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians mainly in the west and centre who consider Russia an enemy and support ethnic concepts of Ukrainian identity; Russian-speaking Ukrainians mainly in central and south eastern areas; and ethnic Russians mainly in Slobozhanshchyna, Donbass and Novorossiya.Footnote2 The last two groups fought on the side of the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany and originally supported a multiconfessional, multi-ethnic, and multi-cultural state. Alongside these three broad groups are Belarussians, Moldavians, Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Romanians, Poles, Jews and many others.

In terms of religion the west was Uniate (Greek Byzantine Catholics whose Orthodox church derives from the fifteenth century union of the Greek and Roman Catholic churches under the Pope in Rome) (9.5% of the national total in 2019 but 35.8% in the west) and Roman Catholic (1.6%), while the centre and the east were Russian Orthodox under the Patriarch of Moscow (64.9% nationally but 46.6% in the west) (Religious Information Service of Ukraine Citation2019). In 2018 (although there were other post-independence nationalist initiatives) a relatively small part of the latter created a Ukrainian Orthodox Church under the Patriarch of Constantinople. A large Jewish population was decimated in the Second World War.Footnote3

In 1991 Soviet President Gorbachev told US President Bush

that Ukraine in its current borders would be an unstable construct if it broke away [as] it had come into existence only because local Bolsheviks [did not have a majority in the Rada (council)]. … They had “added Kharkov and Donbass,” and Khrushchev later “passed the Crimea from Russia to the Ukraine as a fraternal gesture” (National Security Archive Citation1991; see also Sarotte Citation2021, 127).

Until the break-up of the Soviet Union, a Ukrainian state had almost never existed: two rival states existed briefly in 1917–1918 and another in 1941. Instead, Ukraine comprised a series of border zones and a number of peoples whose near and distant ancestors had lived in a succession of different and often warring countries. The territories of contemporary Ukraine, Belarus and western Russia do have a shared heritage in a medieval political federation of Slav, Scandinavian Varangian, Turkic and other tribes (Subtelny Citation2009), called from 862 the Novgorodian, and from 882, after the seizure of Smolensk, Liubech and Kiev, the Kievan Rus (882–1242).

Over the centuries, however, contemporary Ukraine was successively divided. Between 1219 and 1242 the Tatar or Mongolian invaders conquered the Rus (in 1240 Kiev was almost destroyed by the grandson of Genghis Khan, Batu Kahn), incorporating its eastern part into the vast Mongol Empire. From 1385 much of western Ukraine and of the Kievan Rus came under the feudal Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1385–1795), situated between Latin civilization, Orthodox (Muscovy) civilization and the Muslim Ottoman Empire (Snyder Citation2003, 105–119).

In this era the Rada of the Cossack army in Ukraine chose to submit (in the 1654 Pereyaslav Treaty) as an autonomous duchy under Russian rule, precipitating a war between Poland and Russia. This war ended with the 1667 Truce of Andrusovo, the 1686 Treaty of Perpetual Peace and the division of Ukraine between these two countries (see and ).

Figure 1. Treaty of Perpetual Peace, 1686.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44247299 and https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8d/Polish-Russian_peace_treaty_1686.JPG.

Figure 2. Ukraine through the ages.

Note: Soviet era oblast borders are not always exactly the same as those of former historical regions of Ukraine, especially in the lower Dnieper area.

The Commonwealth disappeared as a result of the Three Partitions of Poland (1772–1795) engineered by Austria (the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867), Prussia and Russia. Contemporary Ukraine was divided between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire. Specifically, in 1764 the last Ukrainian Hetman or commander-in-chief was officially deposed by Catherine the Great, and much of Ukraine became a province of the Russian Empire. In 1768 to 1774 a series of battles saw Catherine and the Russian Empire acquire Crimea and other Ottoman territories north of the Black Sea and as far west as the River Dnieper, leading to the establishment of Novorossiya (see and the associated timeline which outlines the evolution of the different parts of contemporary Ukraine from the first proclamation of a Ukrainian national state in 1917 until 2014).

In 1917, in the final stages of the First World War, the Bolshevik revolution ushered in a civil war lasting from 1918 to 1922 (Carr [Citation1952] Citation1985). In March 1917, in Kiev, a handful of Ukrainian nationalists proclaimed the creation of the Central Rada and eventually a Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), first as an autonomous part of the Russian Republic, and then in 1918 as an independent country. This act was solemnified in a treaty concluded at Brest-Litovsk on February 9–10, 1918 by representatives of the UNR and the Central Powers (Imperial Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire). A German aim was to use self-determination to explode the Russian Empire and establish German hegemony in Central Europe (just as Poland had earlier exploited it for Polish national purposes). As for the UNR and its nationalist supporters, they drew amongst other arguments on the claims of a small number of petty bourgeois intellectuals in mid-nineteenth century Austro-Hungarian Galicia and legacies (shared with Russia and Belarus) with the Cossack Hetmanate and Kievan Rus, laying claim to all the territories of the southeast and south of contemporary Ukraine and parts of southwest Russia (Khotyn Citation2017).

At the end of 1917 the Bolsheviks proclaimed their own Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets (UNRS) in Kharkov. In the same city in early 1918 the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Republic (DKR) was proclaimed. A short-term war between the “bourgeois” UNR and the “proletarian” UNRS ended in early 1918 with the establishment of Soviet power in Kiev. But a German and Austrian invasion and the subsequent signing in March of the second Treaty of Brest-Litovsk saw the Central Rada return to Kiev and assume short-term control. Very quickly what Germany considered an insufficiency of Ukrainian grain deliveries led to a German coup d’état that ousted the Ukrainian Rada and installed a so-called Hetmanate under the Tsarist cavalry officer, Pyotr Skoropadskyi (Tooze Citation2022). The nationalists established a government in exile in Austro-Hungarian Galicia under Symon Petliura with a view to establishing a racially homogeneous Ukrainian state. At that stage two divergent orientations co-existed: a quest in western Ukraine for alliance with the West (at that time Germany and Poland); and another for a federation with Russia.

In 1919 the Ukrainian SSR was established. From Galicia the UNR concluded a treaty of alliance with Poland, supporting Poland in the Russo-Polish War of 1919–1920. By March 1921 the contested claims of Poland, anti-Bolshevik White Russians, Ukrainian nationalists and the Bolsheviks were settled with the Treaty of Riga that established Soviet control over most of Ukraine, with western Ukraine divided between Poland (Galicia and western Volhynia), Czechoslovakia and Romania (until Hungarian control was established over Transcarpathia from 1938). In 1922 much of Malorossiya and Novorossiya were assigned by the Bolshevik leadership to the Ukrainian SSR.

In coming to power the Bolsheviks gave considerable weight to struggles for national independence (but see Smith [Citation1999] who showed that the political positions over the national question of Lenin, Stalin [and the anti-revisionist Rosa Luxemburg] differed and changed frequently and radically). In Ukraine, at the end of 1918 and start of 1919, they created a separate Soviet entity to attempt to satisfy Ukrainian national aspirations and sought to remove all barriers in the way of the free development of Ukrainian language and culture, limit collectivization and grain requisition, and urge the distribution of old estates to the peasants, as, outside the eastern territories conveyed to Ukraine, a strong and deeply rooted national peasant tradition principally directed against landowners and usurers characterized the great majority of the population.

In these circumstances the Ukrainian language was introduced into schools, a knowledge of local history and culture was fostered, and indigenous people were trained for positions of responsibility. As Carr pointed out:

In 1918 … the tide of nationalism was in full flood. … Unqualified recognition of the right of succession not only enabled the Soviet regime—as nothing else could have done—to ride the torrent of a disruptive nationalism, but raised its prestige high above that of the “white” generals who, bred in the pan-Russian tradition of the Tsars, refused any concession to the subject nationalities; in the borderlands where other than Russian, or other than Great Russian, elements predominated, and where the decisive campaigns of the civil war were fought, this factor told heavily in favour of the Soviet cause. (Carr [Citation1952] Citation1985, 257)

The eastern areas differed. In 1913 the Donbass was producing 87% of the coal, 74% of the pig iron and 63% of the entire steel output of the Russian Empire (Pollard Citation1981, 241). It remained the largest producer of coal in the Soviet Union until the 1960s. Added to metals and coal were aviation and rocketry, petrochemicals and power generation (including four nuclear power plants) as well as important defence industries, which continued to play a major role in Ukraine’s economic output, employment, and exports especially until the onset in 2014 of armed conflict in the eastern provinces (oblasts) of Donetsk and Luhansk.

In 1929 in Vienna exiled right-wing émigrés from Polish-controlled Galicia established an authoritarian right-wing Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) (initially embodying the integral nationalism of Dmytro Dontsov and splitting in 1940 into the OUN-M led by Andriy Melnyk, and OUN-B headed by Stefan Bandera) (Snyder Citation2003, 164).

In Soviet Ukraine, civil war, collectivization and subsequently in 1932–1933 famine, requisition quotas were sources of rural hostility that nationalists exploited to reproduce nationalist sentiment especially with the Holodomor myth. Ukrainian nationalists argue that the Holodomor or famine of 1932–1933 was deliberately induced by the Soviet state to murder Ukrainians. The famine was, however, a part of a broader Soviet famine in 1931–1934 (in Ukraine until 1934 there were famines nearly every ten years) and was due not just to difficulties associated with (re)collectivization but also to Western economic sanctions and trade boycotts designed to weaken and sabotage the Soviet economy and environmentally-generated small harvests. In any case western Ukraine itself was not a part of the Soviet Union until 1939 (Tauger Citation2001; Anton Citation2020).

In 1939 the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact (Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) saw the incorporation of formerly Polish western Volhynia and most of Galicia into the Ukrainian SSR, while ethnically mixed Polish-Ukrainian western borderlands were included in the German administrative region of Poland. In June 1940 the Soviet Union annexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina from Romania. These gains were, however, wiped out in the wake of Nazi Germany’s June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union.

Many western Ukrainians welcomed the Germans as liberators, while the head of the OUN-B, Yaroslav Stetsko, made the second declaration (after two rival attempts in 1917) of an independent Ukrainian state, allying it with Nazi Germany. Although the idea of an independent state met with strong German resistance, OUN-M and OUN-B members collaborated with the Germans (with significant overlap in membership with the SS Galician Division) and played active roles in the extermination of Poles, Jews, communists and non-ethnic Ukrainians (Breitman et al. Citation2011; Breitman and Goda Citation2005).

Once the Second World War ended in 1945, the Ukrainian SSR’s western border was re-established to include most of the territory the Soviet Union acquired following the destruction of Poland in 1939, although a small strip of land east of the Dniester River (Transnistria) established as a Moldavian Autonomous SSR under the Ukrainian SSR in 1924 was added to the new Moldavian SSR (Magocsi Citation2018, 137–139).

What resulted was a Ukrainian SSR in which different nationalities co-existed. These groups differed radically in their cultural, linguistic and spiritual identities, historical memories and assessments of the Great Patriotic War and the Soviet experience. In the context of the centrally-controlled multi-ethnic Soviet state, these differences remained beneath the surface. However, they were exploited in and after the Cold War.

At the end of the war many Ukrainian nationalist émigrés were re-settled in North America and Europe, with Canada serving as a prime destination (Rudling Citation2022). Civil and paramilitary organizations were established passing Russophobic nationalist sentiment from one generation to the next and supporting actively indigenous nationalists. In 1944 the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR) was established, along with the affiliated Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) headed by OUN-B leader Mykola Lebed, while in 1949 its overseas members established a Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council ZP/UHVR. The UPA continued anti-Soviet paramilitary operations with the assistance of CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) funding and equipment until 1956. A CIA Project codenamed AERODYNAMIC spanned four decades, working with nationalists in Ukraine and North American and European émigrés and their descendants to “exploit nationalist cultural and political dissident tendencies in Ukraine” and “the minority nationality question in the Soviet Union” (Breitman and Goda Citation2005, 249–255; Breitman et al. Citation2011, 86–91; CIA Citation1953).

Then in 1989 political reform in the Soviet Union saw the establishment of the bourgeois nationalist People’s Movement of Ukraine for Perestroika (NRU) that demanded independence, maximum disengagement from the USSR, exit from the rouble zone, the use of the Ukrainian language as the sole state language (that in 2014 contributed to the eruption of a civil war) and their own army.

In 1991 the Soviet Union was disbanded (although in March 1991 over 70% of Ukrainians had voted to preserve it) and a divorce process was set in motion dividing two economically, politically, culturally and militarily interdependent Russian and Ukrainian SSRs that accounted for 58.7% and 15.2%, respectively, of the GDP of the USSR.

With the establishment of Ukraine as an independent country, a series of new right-wing nationalist groups centred predominantly in the west of the country were established, drawing on the earlier nationalist heritage. In the next thirty years cleavages and struggles unfolded over the orientation of Ukraine towards the west or east between groups who differed in language and religion and whose ancestors stood on different sides in the Great Patriotic War that saw the defeat of Nazi Germany and in which 26 million Russians died, including 18 million civilians, and 70,000 villages and 1,710 cities were devastated.

In the case of Crimea, in January 1991 a referendum supported by 93.6% of population called for autonomous republic status in the Union of States of the Soviet Union. On February 12, 1991 the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea (ASSR Crimea), abolished in 1945, was re-established by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR as an independent entity under Moscow. In 1992 the Crimean parliament approved a constitution which declared that Crimea was an independent state linked to but not part of Ukraine. Ukraine, however, sought to impose a status as the sole autonomous republic in the new Ukrainian state. The development of the autonomous republic saw sustained conflict with the government in Kyiv as the latter sought to treat Crimea the same as any other region (Reinert Citation2022). In 1994 a referendum called for extended autonomy and the 1992 independence constitution. On March 17, 1995, Ukraine forcibly abolished the Crimean Constitution, sent its special forces to overthrow Yuri Mechkov, President of Crimea, and annexed the Republic of Crimea, as demonstrations called for the attachment of Crimea to Russia. In October 1995 the Crimean Parliament formulated a new constitution re-establishing the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Baud Citation2022a).

Other matters had to be settled. In 1994 the trilateral Budapest Memorandum provided assurances of Ukrainian “security, independence and territorial integrity” in exchange for surrender of Soviet nuclear weapons on Ukrainian territory. In 1997 the Soviet fleet was divided, and Sevastopol was leased to the Russian Black Sea Fleet, and a Treaty of Friendship between Ukraine and Russia included the principle of the inviolability of borders and a guarantee of “the protection of the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious originality of the national minorities on their territory” (Baud Citation2022a). Ukraine’s violation of this guarantee in 2014 was an important driver of the current conflict, as perhaps was a 2022 Ukrainian threat to deploy nuclear weapons.

NATO Expansion and Eastern Enlargement

The second side of the problem was that the EU in close conjunction and eventually in complete alignment with US-led NATO expanded eastwards. In the case of NATO expansion occurred in defiance of verbal and written commitments made to Gorbachev that NATO itself would not “move an inch” eastward from its existing configuration (to borrow Baker’s words, which were echoed in security assurances from “Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Gates, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Hurd, Major, and Woerner”) (National Security Archive Citation2017; Sarotte Citation2021, Citation2014).

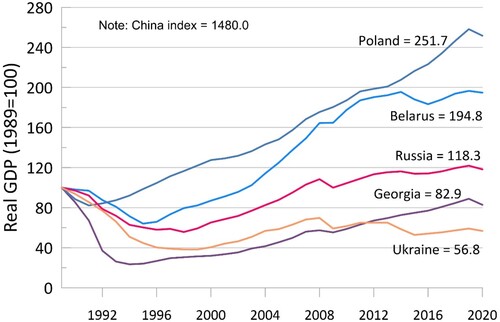

In the 1990s a US “crusade to transform post-Soviet Russia … contributed … to economic ruin” (see ), while the “real US policy was … a relentless, winner-take-all exploitation of Russia’s post-1991 weakness” (Cohen [Citation2009] Citation2011, chapter 7). Eastern expansion of NATO was contemplated with the arrival in power of the Clinton administration from 1993 and was announced in 1996, serving subsequently as a part of a strategy of surrounding and containing Russia, especially once it was clear that it was re-emerging from its subordination to the West at the end of the 1990s, and despite Russia’s repeated overtures to the West for equal co-operative relationships.

Figure 5. GDP evolutions in selected former Soviet republics and Poland, 1989–2020.

Source: The Conference Board (Citation2022).

In 1997 in The New York Times, George Kennan, who drafted the original “Long Telegram,” described the expansion of NATO as “a fateful error” (Kennan Citation1997), while in February 2008, around the time of the announcement of the expansion of NATO to include Ukraine, the then Ambassador to Moscow, George Burns, wrote a cable entitled “Nyet Means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines,” stating that this issue “could potentially split the country in two, leading to violence or even, some claim, civil war, which would force Russia to decide whether to intervene” (Burns Citation2008). In 2022 after the start of the Russian Special Military OperationFootnote4 and commenting on it, realist international relations scholar, John Mearsheimer, explained: “My argument is that the West, especially the United States, is principally responsible for this disaster. But no American policymaker is going to acknowledge that line of argument. So they will say that the Russians are responsible” (cited in Chotiner Citation2022).

In 1991 the Cold War came to an end with a negotiated settlement between Moscow on one side and the NATO powers on the other. In 1997, however, Brzezinski (Citation1997, 24, 14) argued that “without Ukraine Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire” and that incorporating Ukraine into Washington’s sphere of influence would deliver a major blow to Russia and help make the US “the key arbiter of Eurasian power relations.”

In 1992 the US Wolfowitz doctrine declared that

our first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union. This is a dominant consideration underlying the new regional defence strategy and requires that we endeavour to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power. (Wolfowitz 1992,Footnote5 quoted in Tyler Citation1992a, Citation1992b)

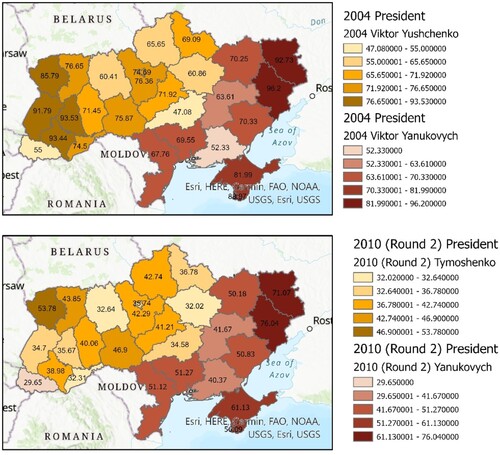

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED), USAID, the Open Society Foundation and federal government agencies spent billions of dollars training journalists, lawyers, judges, and trade unionists and promoting Western-oriented civil society groups. In 2004 a Western-backed colour revolution overturned an election initially won by Viktor Yanukovych (see which reveals the extent of the east-west electoral divide). A former central banker Viktor Yushchenko came to power with Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, adopted a Western-oriented neo-liberal agenda and IMF-style reforms supported by oligarchs, liberals and far right movements, and reiterated earlier calls in the 1990s for Ukraine to join NATO.

Figure 3. Ukrainian 2004 and 2010 presidential elections.

Notes: The figures refer to the share of votes for the candidate receiving the largest share in each area. The reddish tones refer to places where Yanukovych came first.

Source: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). www.osce.org/odhir.

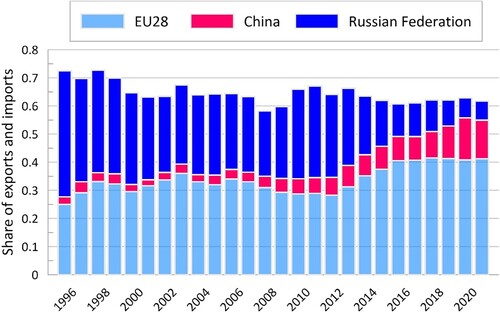

Within two years the parties associated with the Orange Revolution were swept from parliamentary power, though regained influence after the 2007 parliamentary election. In 2010 in the next presidential election Yanukovych won (see ). In that campaign Yanukovych opposed NATO membership and advocated non-alignment. In power the Yanukovych government engaged in dialogues with the EU over an Association Agreement and a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), and with Russia on whose cheap energy Ukraine’s energy-intensive industries depended and with which significant trade relationships remained (see ). Although it was clear that an EU-Ukraine deal would split the country, a trilateral EU-Ukraine-Russia deal was unacceptable to the EU (Diesen Citation2021).

Figure 8. Ukraine’s trade with the EU28, Russia and China, 1996–2021.

Note: This data excludes Crimea and the two People’s Republics from 2014.

Sources: Elaborated from Ukrainian regional GDP, 2003–2019 and from State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Citation2022. http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/.

As early as the 1990s Ukraine had sought closer EU integration and IMF assistance, but the latter wanted faster reforms, while keeping Ukraine apart from Russia. EU involvement increased after the Orange Revolution and the adoption in 2009 of the Eastern Partnerships, just one year after NATO had agreed to extend Membership Action Plans (MAPs) to Georgia and Ukraine, paving the way to NATO membership. In November 2013 the Ukrainian government prepared to sign the Association Agreement and the DCFTA with the EU, a step which Russia opposed as it precluded Ukraine from joining the Customs Union with Kazakstan and Belarus established in 2009 (to which Armenia was added). At the last moment Yanukovych refused to sign the EU agreements, much to the anger of the EU itself, indicating that integration and reform were not its sole objectives (Charap and Colton Citation2017, 121).

In Ukraine industrial production and economic relations with CIS countries had declined, and the government was concerned about the harsh conditions attached to an IMF loan presented in November 2013. These terms included large budget cuts and a 40% increase in gas bills. In the case of the EU Yanukovych wanted measures that would compensate Ukraine for economic adjustment costs. These costs would derive in the case of Russia from the imposition of trade barriers and in the case of the EU from inclusion in a free trade area with economically more advanced countries (possibly including the US with whom an EU trade agreement was under discussion), payment of world market energy prices and adherence to EU competition and standards policies. When the EU refused to meet these terms, Ukraine turned back to Russia. Russia had offered Ukraine a loan it needed ($15 billion) plus gas concessions, although Russia wanted Ukraine to side-line oligarch-controlled financial networks.Footnote6

At that point an enraged US and EU helped drive the Maidan colour revolution, in which initially peaceful pro-European demonstrations descended into violence, as snipers appeared, shooting police and demonstrators. This “false flag operation was rationally planned and carried out with a goal of the overthrow of the government and seizure of power” (Katchanovski Citation2015). The massacre of almost 50 demonstrators galvanized the anti-Yanukovych movement. The EU sought to broker a coalition government. At that point a US sponsored coup d’état occurred. Government buildings were occupied, and the US (Victoria Nuland and Geoffrey Pyatt on behalf of the Obama regime) which has spent $5 billion on political interference in Ukraine selected a new government that was itself supported by right-wing armed militias.Footnote7

A “government of victors” immediately (February 23, 2014) abolished the special status of the Russian language (the Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law of 2012) with the result that Russian was subsequently eradicated from the spheres of education, official documents, radio and television and non-electronic mass media as well as areas of economic life. Other measures directed against the Russian community included the four 2015 decommunization laws which made illegal not only widely held views in parts of eastern and southeastern Ukraine but also non-recognition of the legitimacy of Ukraine nationalists’ struggle for independence (which included involvement of the UPA in the Volyn massacre of 1943). Another was the already mentioned creation in 2018 of new Orthodox Church of Ukraine severing the connection with the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2021 a draft law on Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine did not recognize Russians, nor did it recognize Belarusians, Moldovans and Poles whose ancestors had long lived on the territory of contemporary Ukraine.

The Maidan revolution and the coup d’état saw naked anti-Russian sentiment set off a violent process of disintegration of the Ukrainian state. Nationalists threatened to expel ethnic Russians from Crimea, and sent armed groups to storm the Supreme Soviet of Crimea. Crimea voted to secede and join the RF in a referendum in which 95.5% chose to join Russia with a turnout of 83%. Western powers claimed that the referendum was illegal under the Ukrainian Constitution and international law, yet counter-arguments included clear evidence of a violation of “self-determination” and the “rights of the people” of Ukraine, as well as the precedents of a quite different stance when Western powers helped drive the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice ruled that, according to the UN Charter, the administration of a territory that secedes from a state need not request permission from the central authorities (Putin Citation2022), and of the establishment of Ukraine itself as a nation in 1991.

As a result of the secession of Crimea, the Ukraine government constructed a dam in the Kherson oblast to block 85% of Crimea’s water supply, destroying the harvest in 2014: as mentioned water supply considerations probably played a role in its assignment in 1954 to the Ukrainian SSR. In Odesa, Dnepropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Lugansk and Donetsk fierce repression against Russian speakers at the start of February 2014 (including a pogrom that saw the death of at least 42 people most of whom were burned alive by neo-NazisFootnote8 in Odesa on May 2, 2014 and that the responsible Ukrainian tribunal has failed to investigate seriously) led to a militarization of the conflict. In April 2014, the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics (DPR and LNR) were declared in the rebel-controlled parts of the two oblasts. At the time of the 2001 Census nearly 75% and 69%, respectively, of their populations reported that their mother tongue was Russian, although strong economic relationships with Russia were also important considerations.

After the defeat of the Ukrainian army in its first attempt (especially significant was the Battle of Ilovaisk) to recover the territories in the east, the Minsk I Agreement was signed on September 5 and 19, 2014. The new Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko then launched a massive “anti-terrorist” military operation to recover the Donbass and reunite Ukraine, but poorly advised by NATO officers the Ukrainians suffered a crushing defeat at Debaltseve, forcing the Ukrainian government on February 12, 2015 to sign the Minsk II Agreement.

These agreements endorsed by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in resolution 2202 of 2015 provided for the negotiation of a special status for the Donetsk and Lugansk oblasts in eastern Ukraine: language, the right to have local police, and special economic relations with adjacent Russian regions. The West, however, led by the French sought to replace the Minsk Agreements with the “Normandy format,” which involved the Russian and Ukrainian governments. For eight years no progress was made. And in June 2022 former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said that the Minsk Agreements “meant nothing” and were signed solely to gain time to “restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces” (Russia Today Citation2022).

In 2015 the Ukrainian army was in a deplorable state (Baud Citation2022b). The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence asked for NATO assistance to make its armed forces more “attractive.”Footnote9 But as it would take time, in order to move quickly and compensate for a lack of soldiers, the Ukrainian government drew on paramilitary militias connected with right-wing movements established at the time of Ukrainian independence and the coup d’état. These groups included the Azov Battalion, the Aidar Battalion, the Right Sector, the C-14 “youth” organization of the fascist Svoboda party as well as a dozen other such organizations and foreign mercenaries. With post-2014 protection from the government and judiciary, Azov and similar groups infiltrated not just the Ukrainian regular military but also the National Guard, the police and the internal secret security organization (SBU). In 2020, they constituted about 40% of Ukrainian forces and numbered about 102,000 men, according to Reuters (Baud Citation2022b). They were armed, financed and trained by the US, Great Britain, Canada and France to NATO standards and to ensure inter-operability and de facto integration with NATO (communication, data-processing, satellite and other reconnaissance systems and precision armament).

For eight years the governments and presidents of Ukraine (almost certainly with the connivance of the US) refused to fulfil the Minsk Agreements, notwithstanding their endorsement by the UNSC. The Normandy Four also failed to ensure that the Minsk obligations were met (Baud Citation2022c, section 5.7). All the while the parts of the two self-proclaimed republics (occupying 38% of the Donbass) held by the rebels were shelled. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), overall 14,200-14,400 lives were lost (3,404 civilians), and 37-39,000 were injured (7-9,000 civilians) (2021, 13). After nearly eight years of civil war, 2.5 million people, including residents of conflict-affected oblasts and internally displaced persons (IDPs), were in need of assistance (OHCHR Citation2022, 5).

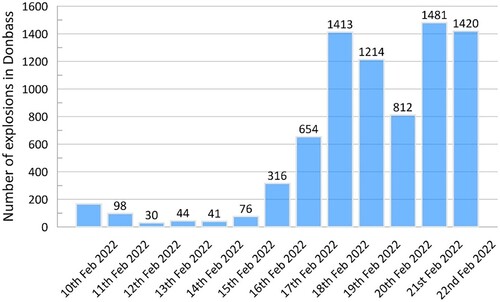

In February 2022 after a sharp increase in shelling of the two republics (), with a NATO-trained armed force of some 120,000 (of a military with some 400,000 members and some 300,000 reserves subsequently mobilized) dug in over eight years along the 457 kilometre line of contact with the two republics, and in anticipation of a planned attempt by Ukraine to retake them by force, Russia chose to recognize the two oblasts as independent countries, signed a mutual assistance treaty and, in response to a request for military assistance, launched a Special Military Operation (SMO) (deploying some 120,000 troops alongside around 35,000 DNR and LNR fighters). Russia argued mainly that the SMO was in accordance with Chapter VII Article 51 of the UN Charter in the exercise of the right of self-defence and assistance in the case of an attack (in this case on the Donbass).Footnote10

Figure 4. Number of explosions in Donbass, February 2022.

Source: OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine (SMM) Daily Reports, www.osce.org. For 12th and 13th and 19th and 20th two-day figure partitioned approximately in the light of the number of ceasefire violations.

Economic Dimensions: Transitions to Capitalism and Multi-vector Politics

In 1989–1991 the former socialist countries were divided into a much larger number of independent countries and embarked on political and economic transitions to multi-party representative politics and capitalism. In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the former Soviet Union, Western-driven neo-liberal economic reforms involved a three-pronged strategy of economic stabilization, implying cuts in subsidies and state expenditure, economic liberalization, entailing a removal of controls on prices and opening up to foreign goods and investment, and privatization of state-owned assets. In Ukraine as in Russia enterprises were privatized into the hands of a small number of powerful politically connected oligarchs.

In Russia in the new millennium the Kremlin power of many Yeltsin-era oligarchs was eroded, and the authority of the state vis-à-vis them increased.Footnote11 In Ukraine by contrast enterprises owned by oligarchs with considerable economic and political power increased in number and influence not only in the 1990s but also in the new millennium. In 2006–2015 politically connected private enterprises accounted for 20% of turnover (The World Bank Group and the UK Good Governance Fund Citation2018, 4). In 2015 State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) still accounted for some 20% of GDP (Pop, Martinez Licetti, Gramegna Mesa, and Dauda 2019, 15).

In each case immense privatizations of state assets served as powerful barriers to economic and political modernization, with income and wealth from vital assets transferred offshore to tax havens and Western countries instead of serving domestic economic transformation.Footnote12 At the 2019 Russia-Africa forum in Sochi, Glazyev (Citation2019) suggested that since 1991 the adoption of IMF measures had resulted in withdrawals of capital worth some $1 trillion from Russia and another $1 trillion from 14 other post-Soviet countries.

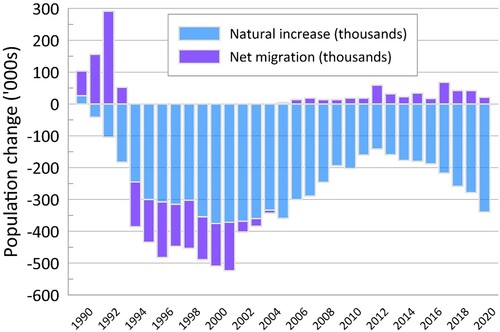

In Ukraine as in Russia and other former socialist countries the economic (see ) and demographic (see ) consequences of transition to capitalist market economies and Western representative multi-party politics were catastrophic: a collapse in output; inflation that devalued the savings of large sections of the population; a dramatic drop in real wages (63% in 1990–1993 in Ukraine [Yurchenko Citation2018, 66], driving more than 32% of the population under the poverty line [Dunford Citation2005, 169]); and a dramatic decline in population. A sharp transitional recession saw real GDP fall to 39.8% of 1989 in Ukraine, rising only to 63.9% in 2019 (61.2% in 2020).Footnote13 In Russia it declined to 56.0% in 1998, and then increased to 122.6% in 2019. In Ukraine the population fell from 51.8 million in 1990 to 44.1 million in 2019, largely because of an excess of deaths over births although net emigration to Europe and Russia also played important roles (see ). In the 1990s Russia’s population declined by 6.7 million, but was offset by some 4 million Russians that moved from former Soviet Republics to the RF.

Figure 6. Population change in Ukraine, 1990–2020.

Source: Elaborated from State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Citation2022. http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/.

This economic catastrophe was due not just to the transition path but also to the disintegration of the Soviet Union: the significant scientific, technological and industrial capabilities of Ukrainian economy were not self-sufficient, but part of an interdependent system which was largely liquidated with the end of the Soviet Union. This loss of synergies was, however, not inevitable. Instead it was also a consequence of policy choices especially after 2014 in Ukraine.

After independence, the Ukrainian economy continued to use the capacities left from the former Soviet Union with relatively little maintenance, investment or modernization: as already mentioned, the oligarchs and their overseas collaborators shifted much of their wealth to tax havens and Western countries. Ukraine is, however, rich in natural resources, especially in mineral deposits. These resources include the world’s largest reserves of commercial-grade iron ore (30 billion tonnes of ore, or around one-fifth of the global total), the second largest natural gas reserves in Europe which remain largely untapped (the Yuzivska gas field discovered in 2010 has US$67 trillion worth of natural gas that can be fracked) and flat terrain with high quality chernozem soils that make Ukraine the world’s fifth-largest exporter of wheat and the world’s largest exporter of seed oils like sunflower and rapeseed. Coal mining, chemicals, mechanical products (aircraft, turbines, locomotives and tractors) and shipbuilding are important industries, as is the manufacture of Soviet military equipment where Ukraine was a central provider. In the 1990s, on the advice of US controlled multilateral institutions, the Ukraine government sold off huge tracts of valuable agricultural land to foreign and domestic investors, delivering massive financial returns. In 2001 a moratorium was imposed on further privatization and most sales, though not on leases (on the early years of transition see Csaki and Lerman Citation1997).Footnote14

In 2000–2008 an economic recovery started. This recovery was centred on its inherited metallurgical (Ukraine by 2007 was world’s fourth steel exporter with steel accounting for 40% of exports), engineering and chemical industries. These industries relied on an abundance of cheap local coal, cheap electricity and subsidized Russian oil and gas (discounted by 35–40%). In 2000–2008 demand soared from emerging economies, and a world commodity boom increased the prices of Ukrainian exports (metals, iron ore, and fertilizers): oil prices quadrupled; iron ore prices more than quintupled; and steel prices tripled (The World Bank Citation2022; Shatokha Citation2014, 1–3).

In 2009, however, Ukrainian GDP slumped by 15% and export volumes by 22% (State Statistics Service of Ukraine Citation2022) due to a decline in world demand in the aftermath of the Western financial crisis, a decline in commodity prices and natural gas disagreements that saw the two post 2004 colour revolution governments of Timoshenko erase implicit Russian energy subsidies. A short rebound in 2010–2011 then gave way to structural stagnation amidst slower global growth and curtailed domestic and foreign investment (State Statistics Service of Ukraine Citation2022; The World Bank Citation2022).

The dissolution of the Soviet Union saw Ukrainian oil import prices reach world market levels in 1993, but gas import prices remained below European levels and were largely offset by gas transit fees. In 2004–2005, Russia was providing approximately a quarter of the natural gas consumed in the EU, and 80% of these exports were via pipelines that crossed Ukraine, generating large transit fees for Ukraine. After the 2004 Orange Revolution that brought nationalists to power, however, Ukraine accumulated large unpaid debts, and Naftogaz diverted gas intended for Europe from the transit system. In March 2005 new problems arose. A serious dispute emerged between the Western-oriented government and Russia over the price of natural gas supplied and the cost of transit. On January 1, 2006, Russia cut off all gas supplies passing through Ukraine for three days. A subsequent dispute over Ukrainian gas debts led to a reduction in gas supplies (Pirani et al. Citation2020). By 2011 concessional gas prices had been largely phased out.

Transit revenues were also affected, as in the new millennium Russia established alternative routes to Europe including the Yamal-Europe pipeline across Belarus and Poland to Germany, Blue Stream to Turkey, South Stream to southeast Europe and Turkey and Nord Stream 1 and 2 (as yet unused and sabotaged in September 2022) to Germany. These pipelines offered the possibility of reducing transit through Ukraine (reducing Ukraine’s current gas transit revenues from $2.5 billion to $1.2 billion annually) and indeed potentially to phase it out altogether. This step and the completion and use of Nord Stream 2 were strongly opposed by Ukraine and the US.

The gas issue was closely connected with the question of Western versus Eastern political and economic orientation of Ukraine. The aim of the Western powers was to bring Ukraine into the Western orbit at the expense of its relationships with Russia. In the case of Russia, a Russian Greater Europe project also existed, dating back to the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, Gorbachev’s vision of a Common European Home and Yeltsin era reforms. The latter, however, simply generated a very asymmetrical partnership.

Once Putin came to power, it was quickly clear that the EU and NATO had no interest in accommodating a revitalized Russia which had identified energy resources as strategic national assets, renationalized energy industries, and declared an end to unilateral concessions. The West conversely

did not have the incentives to accommodate Russia in a European geoeconomic region as it would upset the internal balance of power and undermine the US-centric international system. Instead, Russia’s resurgence only incentivized expansion of the EU and NATO toward Russian borders in terms of membership and partnerships to further skew the asymmetrical dependence relations. (Diesen Citation2021, 23)

From the 1990s the main Western-controlled multilateral institutions, the EU and NATO incentivized former socialist countries to choose the West by decoupling economically, politically and culturally from Russia. Amongst other things a succession of IMF Stand-by agreements shaped Ukraine’s path. The first dated from 2004 but was subsequently put on hold. Next came $16.4 billion for two years in 2008, put on hold one year later, US$15.4 billion for twenty-nine months in 2010, a subsequently suspended $17.01 billion for two years in 2014, a $17.5 billion four-year extended fund facility in 2015 after the Maidan coup d’état (ahead of which Russia had offered a $15 billion loan), US$3.9 billion in 2018 for eighteen months and $5 billion in 2020 for eighteen months. All these IMF agreements involved conditionalities concerning for example energy sector reform and increased energy costs, public expenditure cuts, privatization of SOEs and in conjunction with the World Bank the sale of the 40% of Ukraine’s valuable agricultural land that remained in state-ownership, offering a potential windfall for domestic and international private investors. IMF rules made, however, loans to Ukraine questionable. First, Ukraine lacked the capacity to repay. Second, Ukraine had repudiated debt to an official creditor. Third, in 2014 until today a civil war had led to the destruction of export capacity. In addition, it was questionable whether Ukraine could meet the conditionalities designed to orient it towards the West.

In the case of the EU, reorientation was implemented through the already mentioned Eastern Partnership, Association Agreements and DCFTA and the activities from 2011 of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum. These steps precluded closer integration into Eurasian projects, and required alignment of Ukrainian defence and security policies with the EU (including the Common Security and Defence Policy or CSDP). The choice of an EU path pitted Western oriented neo-liberals and others who imagined that it afforded a rapid path to Western living standards as well as Russophobic ethnic nationalists concentrated in the western part of the country against groups oriented towards Russia in the south and east. As already mentioned, this conflict had erupted in 2004. The outcome was the arrival of the government under which the gas dispute arose. In 2013–2014 the conflict erupted again. On this occasion it was triggered by the refusal of Yanukovych, the President elected in 2010, to sign the EU Association Agreement.

Yanukovych’s decision was driven by an assessment of the relative costs of Western versus Eastern integration. The Russians had offered Ukraine a $15 billion loan, a discount on gas prices, and membership of the Customs Union of Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus.Footnote15 On the EU side it was made clear that Ukraine had to satisfy IMF loan conditionalities. The Association Agreement itself required Ukraine to adopt the entire body of EU law as it relates to the economy and aimed to make Ukraine a part of the European Economic Area and Single Market with its rules, norms and standards. If this agreement were accepted and Ukraine-Russia trade relations remained the same, EU goods could enter Russia without hindrance, as Ukraine and Russia had a free trade agreement. As it could not accept an outcome of this kind, where it had played no part in the negotiations, Russia said that, if Ukraine signed the agreement, it would terminate its free trade arrangement with Ukraine (Russian Insider Citation2015).

It was evident to the Yanukovych government that this reorientation would have adverse consequences for some of the main industries of Ukraine. These industries were located mainly in Donetsk, Lugansk, Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk, Zhaporizyha and Nikolayev oblasts in the east of the country which manufactured iron, steel, machinery (aircraft, vessels, nuclear reactors and boilers, railway equipment, tramway rolling stock) and inorganic chemicals and involved the export of manufactures rather than of natural resources and grain.

In the event the government was replaced and the EU Association Agreement was signed. Once oriented to EU markets, resource exports assumed increased importance. Ukraine for example exported sawn timber. In 2015, however, Ukraine imposed a (inadequately enforced) moratorium. This measure made economic and environmental sense: any country should conserve forest resources and, where it exploits them, develop processing industries rather than export natural resources. The EU responded by threatening to withhold a third tranche of financial assistance. As a former head of the Ukraine government Sergey Arbuzov indicated, the challenge in 2014 was whether Ukraine was made into a “hostage to the exclusive interests of European industrial, financial and economic circles” exporting raw materials, while confronting obstacles in sectors where it can compete in European markets (RIA Novosti [РИА Новости] Citation2021).

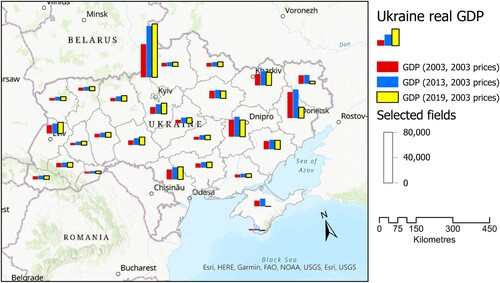

Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the EU Agreement in the first half of 2014 precipitated the Maidan and the coup d’état, Crimean secession and the civil war. The subsequent economic reorientation away from Russia and the CIS to the EU (see which indicates a substantial decline in the share of exports to Russia and an increase in the EU share as well as that of China) was accompanied by losses particularly in relation to energy-intensive iron, steel, and machinery exports rendered uncompetitive. Traditionally Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts were the export powerhouses of Ukraine, accounting for 35% of the country’s export earnings and a net trade surplus. In 2004, Donetsk Oblast generated more than 13% of Ukraine’s GDP, and Luhansk Oblast another 4.3%. By 2013, however, their shares had fallen to 10.8% and 3.6%, respectively. From 2014 the civil war was an important contributory factor: economic displacement, destruction and disorganization had serious negative economic consequences for the Donbass, though in 2014–2017 Crimean real GDP grew at 6.2% per year (3.0% in 2003–2013) compared with 2.4% in the RF ( and RFFSGS Citation2022).

Figure 7. Ukrainian regional GDP, 2003–2019.

Notes: Data for Donetsk and Lugansk exclude the DPR and LNR. Estimates were derived from real GDP indices and 2003 real GDP in Ukrainian Kryvnia UAH).

Source: Elaborated from State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Citation2022. http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/.

Security Dimensions: Eastern Expansion of NATO

As already mentioned, Western economic orientation was accompanied by the eastward expansion of NATO (with membership increasing from 13 to 29 counties). In the case of Ukraine expansion also involved rejection of military cooperation with Russia. In 1993 the Clinton regime simply set aside any commitments to Russia, and proceeded with NATO expansion as a way of projecting US power up to its borders, notwithstanding George Kennan’s statement that it would end in a geopolitical catastrophe.

In 1999 NATO expansion beyond the boundaries that prevailed at the time of the 1997 Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation (NATO–Russia Founding Act) started. The first step was the accession of the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland in 1999. In the same year NATO started its illegal war against Yugoslavia, contributing to the dismemberment of a multi-ethnic state. In 2001 it deployed in Afghanistan, and in 2011 it intervened in Libya, making it progressively clearer that NATO was also transforming itself into an offensively oriented military alliance.Footnote16 Further expansions occurred in 2004, 2009, 2017 and 2020.

As Cohen pointed out:

Moscow’s protests and counter-steps were indignantly denounced by American officials and commentators as “Russia’s determination to re-establish a sphere of influence in neighboring countries that were once a part of the Soviet Union.” Labelling this a “19th-century agenda,” they insisted, “We do not recognize … any sphere of influence.” … But what was NATO’s eastward movement other than a vast expansion of America’s sphere of influence—military, political, and economic—into what had previously been Russia’s? (Cohen [Citation2009] 2011, epilogue).

In 2002 the US announced its withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Agreement and started negotiations with some East European countries to deploy anti-ballistic missiles designed to thwart retaliation and give the US a first strike capability. In 2009 it allowed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) to expire. In 2019 it withdrew from Mid-Range Nuclear Forces Agreement. In 2020 it withdrew from the Open Skies Agreement and the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

In 2007 at the G20 summit Vladimir Putin indicated that NATO had stepped beyond what was acceptable. His statement was met with considerable NATO and Western countries’ anger, as these countries considered that NATO expansion was a matter for them to decide. In his speech Putin (Citation2007) declared:

I think it is obvious that NATO expansion does not have any relation with the modernization of the alliance itself, or with ensuring security in Europe. On the contrary, it represents a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust. And we have the right to ask: against whom is this expansion intended? And what happened to the assurance our Western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact? Where are those declarations today? No one remembers them. But I will allow myself to remind the audience what was said by NATO General Secretary Mr Manfred Wörner in 1990: “The fact that we are not ready to place a NATO army outside of German territory gives the Soviet Union a firm security guarantee.” Where are these guarantees?

From 2007 onwards, NATO’s expansion became an increasingly contentious matter. Despite a clear awareness of the fact that its presence on Russia’s borders was increasingly seen as an existential threat to Russia, much as Soviet missiles in Cuba and US missiles in Turkey were seen as existential threats to the US and USSR in 1962 that themselves took the world to the verge of nuclear war, in just the following year (2008) NATO announced a decision implying the future absorption of Georgia and Ukraine.

In late 2021 after it had gained a certain edge with the development of new hypersonic missiles and state-of-the-art weapons (Martyanov Citation2018, Citation2019), notwithstanding its much smaller military expenditure and international presence,Footnote17 Russia demanded “new” security guarantees, pointing to the violation of the principle of indivisible security enshrined in important documents (signed by the US) such as the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, the 1990 Charter of Paris for a New Europe, the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation in 1997, and in important OSCE Treaties, including the Istanbul 1999 Charter for European Security and the 2010 Astana Declaration. The 1994 Code of Conduct on Politico-Military Aspects of Security also clearly says that states will choose security arrangements including membership in alliances “bearing in mind the legitimate security concerns of other States” (OSCE Citation1994, 2).

The construction of the OSCE Security Treaties was in some ways similar to the UN Charter, since the aim was to prevent unilateral action by any nation or group of nations that impinges on the security of another nation (great power). Essentially the OSCE Treaties provide for one nation’s power of veto over another nation’s choice, as no nation can ensure its security at the cost of that of another nation.

On December 17, 2021 the Russian Foreign Ministry published Russia’s drafts of two proposed new security guarantee agreements that it had sent to the US. Moscow expected Washington and NATO to (negotiate and) sign these agreements. These guarantees were required to address three fundamental concerns, namely, “preventing NATO’s expansion, non-deployment of strike weapons systems near Russian borders and returning the military infrastructure of NATO in Europe to the positions existing in 1997 when the Russia-NATO Founding Act was signed” (TASS Citation2022b). On January 26 the US and NATO replied. The NATO response to Russian demands for security guarantees stated: “NATO is a defensive alliance and poses no threat to Russia. We have always striven for peace, stability, and security in the Euro-Atlantic area, and a Europe whole, free and at peace” (Lieven Citation2022).

Each of these three statements is questionable: one can argue that NATO is an offensive alliance, does pose a threat to Russia and conducted an illegal war against Yugoslavia. More significantly, after delivery of the US response, US Secretary of State Blinken (Citation2022) said: “First of all, there is no change. There will be no change.” Instead, the US sought to draw out the discussion of Russian demands by agreeing to discuss minor issues. All these issues were ones originally proposed by Russia but that the US would not originally discuss. Most importantly, the responses ignored Russia’s three fundamental concerns. At the same time the US referred to the right of states to choose freely ways to ensure their security. As Russia insisted, however, this principle is only one part of the notion of the indivisibility of security, as the principle also precludes strengthening the security of one state at the expense of that of others (TASS Citation2022b).

In relation to the principle of indivisible security, on February 2, Russia then published a request sent at the end of January to all OSCE nations asking for

a clear answer to the question how our partners understand their obligation not to strengthen their own security at the expense of the security of other States on the basis of the commitment to the principle of indivisible security. How specifically does your government intend to fulfil this obligation in practical terms in the current circumstances? If you renege on this obligation, we ask you to clearly state that. (Lavrov Citation2022).

As for Ukraine, apart from the non-implementation of the Minsk Agreements, in March 2021 President Volodymyr Zelensky signed Decree 117/2021 approving the “strategy of disoccupation and reintegration of the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the Sevastopol City”Footnote18 with the aim of restoring Kiev’s control over Crimea. In February 2022 at the Munich Security Conference he announced that Ukraine may withdraw from the 1994 Budapest Memorandum and retains the ability to make and deliver nuclear weapons.Footnote19 Over the course of eight years Ukraine had established a deeply echeloned and well-fortified system of concrete structures and a large military presence along the Ukrainian side of the line of contact with the DPR and LPR. In this context, Russia was also concerned about arms supplies to Ukraine, the dispatch of Western advisers and instructors (including the training of Ukraine’s two fascist battalions), and the cessation of NATO countries’ joint exercises with the Ukrainian armed forces.

In mid-February after a major build-up on the borders of the two republics that had sought autonomy there was a large increase in ceasefire violations (see ) that could be construed as the start of a Ukrainian offensive. On February 22, Western countries imposed sanctions on Russia. On February 24, 2022 the first of the “military-technical measures” was put into effect when a Russian SMO started with the destruction of Ukrainian military infrastructure and the despatch of maybe 120,000 Russian troops to support the Donbass forces.

Immediate Consequences

In anticipation, the Collective West–implemented sanctions that it had prepared well in advance and that indicated its confidence in economic escalation dominance. The seizure of Russian foreign exchange reserves ($300 billion), cutting Russian banks off the SWIFT interbank settlement system and the imposition of severe sanctions were expected to collapse the Russian economy and possibly deliver regime change. The US Treasury sought to prevent Russian payments to American bondholders to force debt default, and all in all by early October eight rounds of sanctions had been agreed.

The effects on Russia of Western sanctions along with subsequent symmetrical and asymmetrical Russian actions designed to adapt and disrupt economies and entities that targeted it were, however, much smaller than anticipated, while those on the Collective West were far more serious than expected (Ding Citation2022). Although the US has gained, as a result of an increase in US dollar exchange rates, an increase in energy sales to Europe and increased sales of military equipment, it will suffer as a result of a longer-term decline in confidence in the dollar and as a result of increases in the costs and reductions in the availability of energy, food and resources whose importance for survival is far greater than intangible services in which the US and Western countries specialize (Dunford, Liu, and Pompeani Citation2022). More generally a new division of the world and decreased Western political leverage, unsustainable debt, runaway inflation, declining competitiveness, energy crises in Europe and a compression of US resources that reduces its willingness to share them with its allies confront much of the Collective West with an economic calamity.

The seizure of Russia’s foreign reserves raised serious concerns about the safety of US dollar holdings for foreigners, which will encourage the use of currencies other than the dollar and the development of new international monetary and payment settlement systems pegged to baskets of national currencies and commodities, leading potentially to a serious erosion of US dollar hegemony (Glazyev Citation2022), especially if alternative sources of credit and development finance enable stressed countries to escape the trap of unrepayable dollar debt. At the same time Russia may seize Western assets in Russia (estimated at $500 billion in 2020) and cease to respect Western patent and intellectual property rights (Escobar Citation2022).

The sanctions and the conflict led rapidly to serious disruption of energy, raw material and food chains and created risks of inflation, stock market crises and recession. In the case of gas, Russia demanded payment in roubles. Given that Russia accounted for 40% of EU gas consumption (37% in 2019 and 32% in 2021 to the EU and UK) and Germany pays just $280/1000 cu metres for the Russian gasFootnote20 needed to sustain its industrial competitiveness, most EU countries opened accounts with Gazprombank which is exempt from international sanctions, effectively paying Russia in its own currency. To reduce its dependence on Russian fuel the EU imposed an embargo on coal supplies. In the case of Russian oil (more than 25% of imported crude oil in the EUFootnote21) the EU has so far failed to agree on a gradual abandonment of imports due to the serious consequences for some countries (especially Hungary) while a planned price cap may prove counter-productive, especially in conjunction with OPEC + production limits.

A desperate attempt in Europe to replace Russia as a supplier of energy and prevent an energy crisis in the winter months has achieved little success, while the possibility of a settlement with Russia or avoiding routes across Poland and Ukraine was reduced by the September 2022 environmentally-destructive sabotage of Baltic Sea gas pipelines.Footnote22 As the US had long demanded, the EU switched to more expensive US liquefied natural gas (LNG) potentially removing the US-EU trade deficit of just over $100 billion in 2021, and addressing the growing problem of US debt ($31.2 trillion at the end of October 2022, according to the US Department of the Treasury and Bureau of the Fiscal ServiceFootnote23). However, many energy-intensive industries closed or reduced the scale of activity due to supply chain disruptions, increased energy costs and reduced availability.

Russia does not just supply oil and gas. With Ukraine it accounts for some 24% of global wheat exports (the US and Canada account for another 23%) and large shares of corn, barley and sunflower products, generating strong increases in world prices and serious shortages. Russia accounts for large shares of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, potash, and urea manufacture, and it provides critical raw materials such as nickel, palladium, titanium, enriched uranium and tungsten required for electrical, automotive, aerospace, defence and semiconductor industries. Neon gas sent from Russia to Mariupol and Odesa (70% of global production) is used in the inscription of microcircuits on silicon plates.

The conflict and the division between Russia and Germany also disrupts (as the US intended) a Eurasian “Grossraum” linking manufacturing in China with a German bloc (including Austria, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands to the west and south and the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland and Slovenia to the east potentially extending into Ukraine) where Russia was a vital energy supplier and logistics connector (Halevi Citation2022). The greatest damage is to the competitiveness and sustainability of Germany’s industrial economy and the Euro zone that depends on its surpluses as it will sacrifice market share to China and India. Increased energy costs and susceptibility to a recession saw non-dollar exchange rates decline, and the costs of dollar debt increase. These outcomes are a consequence of several factors: the German commitment to energy transition, the importance of the financial and media sectors, the relationships of German industries with the US and US markets, an Atlanticist German choice to support NATO expansion under US leadership, German support for the Orange Revolution in 2004 and Maidan in 2014, and renewed rivalry for influence in CEE, with Germany seeking an expanded, militarized EU under German leadership and majority (rather than unanimous) decision-making in the European Council. After the Western cohesion of the first few weeks internal divisions surfaced, and, as Europe did not adopt a principled independent stance, it is for the moment no longer a significant independent political actor.

In order to lock Russia into a protracted and costly conflict, the Collective West provided Ukraine with significant military and financial assistance and deployed NATO intelligence, satellite, communications and other systems to support it. In early May 2022 US President Biden signed the 2022 Ukraine Democracy Defence Lend-Lease Act permitting the US to lend or lease defence equipment to Ukraine for two fiscal years. Towards the end of May 2022 the US approved $40 billion for Ukraine. Of this sum $9.05 billion was for replenishment of US weapon stocks and another $1.2 billion for US defence activities, along with $3.9 billion for US and European command operations in support of Ukraine (intelligence, mission and other types of active military support indicating clearly the active role of NATO in this conflict). For Ukraine the US committed $6 billion for weapons and training and $8.8 billion in economic assistance (44.8% of the total). Also included was $4.4 billion to help address global food security, and $0.9 billion for refugee support, as well as money to fund a variety of other activities including relocation of the US embassy in Ukraine and a programme to seize Russian assets (One Hundred Seventeenth Congress of the United States Citation2022). At the end of September 2022 the US Senate approved another $12 billion in new economic and military aid for Ukraine taking the total for 2022 to $65 billion (Camdessus Citation2022). By late May 2022 the EU had allocated a total €2 billion under the European Peace Facility to recompense EU member states for supplies of military equipment and €2.6 billion in other assistance (European Commission Citation2022), repudiating its claims that its mission was peaceful (Bilquin Citation2022). Other countries providing military and other support included the United Kingdom, Poland, Germany, France, Canada and Italy.

Alongside the economic and military measures, a massive information war and media control measures were launched along with an astonishing series of actions to cancel Russian people and Russian culture. Attempts were made to condemn and isolate Russia. In a United Nations Assembly vote, 143 nations “condemned the invasion” but the 93 countries that supported a decision to expel Russia from its Human Rights Council were fewer in number than the countries that voted against, abstained or did not take part. The discovery of information about US biological research in Ukraine damaged its international reputation.

Most strikingly, sanctions were confined to Collective West, Japan, South Korea and Singapore (countries representing less than one-fifth of the world’s population), marking a division of the world between the former colonial and imperial powers and the parts of the world that were colonized or dominated by the Collective West in the last 500 years. The West was more unified than ever as a result of the complete subordination of the EU to NATO and through it to the US (Streeck Citation2022), yet increasingly isolated. Moreover, this division of the world was quite different from that between what the US calls “democracies” and “autocracies.”

At the centre of this conflict is a desperate attempt by the US to preserve the US-led liberal international order (The White House Citation2017) and its ability to set preferably on a planetary scale “the rules and the norms and the institutions through which countries relate to one another … in a way that advances our own interests and values” (Blinken Citation2020): a global US guided constitution of capital that guarantees private property rights, economic liberty and capitalist competition and predation is out of the reach of sovereign states (Slobodian Citation2018) and inhibits the development in emerging powers of core intellectual property and competitive strategic industries (see Cheng and Lu Citation2021). In the political sphere the US advocates representative multi-party political systems open to external interference and colour revolution insofar as they do not accede to US rules and interests.

In this struggle the US has lost ground, having failed to rebuild its infrastructure and industries (Dunford Citation2021b), endured societal divisions, endlessly created liquidity via “uncontrolled emission and accumulation of unsecured debt” to address successive crises (Putin Citation2022), and continued to over-exploit the planet’s limited resources, while asset seizures and sanctions are eroding the role of the dollar, accelerating the “constructive destruction” of the old global order. On the other side, increased instability, strategic military alliances and encirclement and containment of rivals create markets for its military industrial complex (just as peace would undermine them) and disruption of Russian energy supplies expands US energy markets.

At the end of 2021 as its relations with a steadily encroaching US and NATO continued to deteriorate, Russia allowed the confrontation to intensify. Russian and US power resources had moved in opposite directions, and Russia thought it could achieve its aims of defending the two People’s Republics, demilitarizing and denazifying Ukraine and eventually establishing new European security arrangements. As the initial opportunity of a negotiated settlement evaporated, Russia established facts on the ground that have led so far to referenda in which overwhelming majorities in large turnoutsFootnote24 in four oblasts voted to join the RF, opening a new phase in the conflict and securing a Crimean land bridge with road and rail connections (Zaporizhia oblast) and control over Crimea’s water sources (Kherson).

As a result of its counteractions including strong monetary measures adopted by Russia’s central bank, a short initial fall in the exchange rate was turned into a very strong increase against Western currencies. In the first four months of 2022 Russia ran its highest trade surplus since 1994, at $96 billion. The estimated surplus in January to October 2022 stood at $215.4 billion, compared with $92 billion in the previous year. Moscow has accumulated huge foreign exchange reserves of $630 billion.Footnote25 It is a net creditor on the international market and a rapid rise in oil and gas prices guaranteed significant tax revenues.