Abstract

Recent years have seen a considerable increase in the scope and magnitude of party regulations. Despite the increased propensity of the modern democratic states to intervene in the activities, organisation and behaviour of parties, the phenomenon of party regulation has received relatively little systematic and comparative scholarly attention. In order to fill part of the existing gap in the literature, we concentrate on the regulation of political parties in the post-communist democracies of East-Central and Southeast Europe. Our focus is on the formal rules as stipulated in Party Laws, finance laws and national constitutions, while we explore their impact on the party organisations and party systems.

Introduction

Political parties in modern democracies are increasingly managed by the state through public law and the constitution.Footnote1 Recent years have seen a considerable increase in the scope and magnitude of regulations that are specifically targeted at political parties. As a consequence, their external behaviour and activities as well as their internal organisational structures have become increasingly defined, prescribed or even proscribed by the laws of the state. Indeed, as Katz (Citation2002, 90) has argued, political parties have become “legitimate objects of state regulation to a degree far exceeding what would normally be acceptable for private associations in a liberal society”.

Despite the increased propensity of the modern democratic states to intervene in the activities, organisation and behaviour of parties, the phenomenon of party regulation has hitherto received relatively little systematic and comparative scholarly attention, from political scientists or constitutional lawyers (for notable exceptions, see Janda Citation2005; Müller and Sieberer Citation2006; Karvonen Citation2007). It has only been in recent years that the empirical and normative dimensions of party regulation state to intervene in party politics are beginning to be systematically charted (e.g. van Biezen Citation2008, Citation2012; van Biezen and Borz Citation2012; van Biezen and Molenaar Citation2012; Casal Bértoa and Spirova Citation2013; van Biezen and ten Napel, Citationforthcoming; Casal Bértoa, Piccio, and Rashkova Citationforthcoming). More generally, however, as Avnon (Citation1995) observed nearly two decades ago, the subject of Party Law remains a relatively neglected aspect of research on political parties, with discussions limited to passing references and lacking a comparative dimension.

This lack of scholarly attention is regrettable, because in a broad sense, party regulation establishes the parameters for the functioning of political parties and thus contributes to the creation of the institutional context within which political parties operate. In addition, party regulation constitutes an important dimension of the party–state linkage (van Biezen and Kopecký Citation2007). The nature and intensity of the regulatory framework can thus also shed light on the strength and type of relationship between political parties and the state (cf. Katz and Mair Citation1995). In order to fill part of the existing gap in the literature, in this special issue we concentrate on the regulation of political parties in the post-communist democracies of East-Central and Southeast Europe, and on Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Romania, in particular. In analysing the various dimensions of party regulation, we build on the main premises derived from the neo-institutionalist literature in political science, which is concerned with the ways in which the (formal and informal) rules and procedures may influence, constrain or determine the behaviour of political actors (cf. March and Olson Citation1984; Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Our focus is on the formal rules as stipulated in Party Laws, finance laws and national constitutions, while we explore their impact on the party organisations and party systems. In general, the main finding of the special issue is that party regulation has had an uneven impact on party (system) development in post-communist Europe, at least as concerns the shaping of the outcomes.

The constitutional recognition of political parties

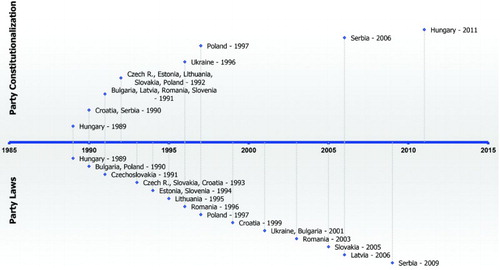

The recognition of political parties in Eastern European Constitutions began, as given in , in 1989 when the Hungarian Országgyűlés (National Assembly) heavily amended the 1949 Communist Constitution. Other post-communist democracies would soon follow suit in what has been considered to be the “fourth wave of party constitutionalization” (van Biezen Citation2012, 197).Footnote2 This wave, which clearly corresponds to Huntington's “third wave” of democratisation, followed from the (re-)introduction of democracy (in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Romania), often combined with the establishment of newly independent nation-states (the Baltic states, former Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia) (van Biezen Citation2012, 198; van Biezen and Borz Citation2012, 329–330).

Figure 1. Chronology of party regulation in post-communist Europe.

For many of the newly established East European democracies, the German Basic Law served as a model constitution. As a consequence, in most post-communist countries political parties are constitutionally codified as institutions which play an essential role in the democratic system by contributing to the formation, definition, development and/or expression of the popular will. The only exception in this regard is Slovakia, where, as in the post-war Italian constitution, parties are addressed in terms of the right of citizens to establish such organisations.Footnote3 Post-communist democracies share a number of resemblances with one another, as well as other European democracies, with respect to the constitutionalisation of political parties. Similar to the Supreme Norms in the post-authoritarian countries of Southern Europe (van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014), for example, most post-communist constitutions associate political parties with essential democratic values and principles, such as political participation, pluralism, competition and popular sovereignty. Of the countries in this special issue, Slovakia constitutes the only exception.Footnote4 Moreover, as we will see in more detail below, most post-communist constitutions also tend to constrain the programmatic identity as well as the behaviour of the parties, by introducing a prohibition of programmes and behaviour that conflict with the fundamental principles of democracy. The authority to monitor the parties' compliance with the democratic rules of the game usually lies with the (Constitutional) courts (van Biezen Citation2012, 203, 206). Another commonality between nearly all post-communist constitutions (except the Czech Republic) is that they aim to regulate not only the external activities of the parties but also their internal organisational structures. In particular by establishing membership incompatibilities with certain public offices, the new post-communist democracies have made a clear attempt to distance themselves from their totalitarian past by creating formal boundaries between political parties and the institutions of the state. The Slovakian Constitution in fact explicitly requires as much, with article 29.4 stipulating that “political parties and political movements … shall be separate from the State” (van Biezen Citation2012, 204).

One first aspect in which post-communist constitutions differ is in the degree of stability of their regulatory framework. In one group of countries, including Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia, the constitutional provisions concerning political parties have remained unaltered since the moment of their promulgation, more than 20 years ago. In a second cluster, those countries, after having initially heavily amended their Communist Constitutions (i.e. Poland, Serbia and Hungary), adopted an entirely new constitution in 1997, 2006 and 2011, respectively. In yet another group, the Supreme Norms involving political parties have been amended at least once. (i.e. Latvia in 1998, Croatia in 2000 and 2001, Slovakia in 2001, Romania in 2003 and Ukraine in 2004).

presents an overview of the scope and intensity of party regulation in post-communist Eastern Europe, with the top half of the table showing the results of a content analysis of national constitutions, and the bottom half the analysis of Party Laws. The analytical framework we employ here is based on that developed by van Biezen and Borz (Citation2012), which distinguishes between various domains and categories of party regulation. From it can be concluded that there is considerable variation in terms of the scope of party constitutionalisation among the countries in this special issue. The range of constitutional regulation is lowest in the Latvian Constitution, which contains provisions in only 1 area out of a possible total of 12, namely, one referring to the rights and freedoms of political parties. The Slovenian and Slovak Constitutions follow suit with two and three areas, respectively: including in both cases those pertaining to the extra-parliamentary organisation of political parties as well as the judicial oversight of party behaviour. The Croatian Constitution, on the other hand, contains the most comprehensive set of regulatory provisions on political parties in the post-communist region, encompassing nine areas of regulation; in addition to the rights and freedoms of parties, their extra-parliamentary organisations and external judicial oversight, the Croatian Constitution associates political parties with key democratic values, prescribes their activity and identity such that they are commensurate with the democratic constitutional order and contains references to political parties in their government and parliamentary capacity. In terms of the scope of party constitutionalisation, Croatia is closely followed by Romania and Ukraine, with eight areas of regulation each. The rest of post-communist constitutions are positioned somewhere in the middle, with a range of seven (Bulgaria, Poland and Serbia) and five (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary and Lithuania) areas of constitutional party regulation.

Table 1. Magnitude of party regulation (Constitutions and Party Laws) in post-communist Europe.

The constitutional rules do not cover all areas in all countries, nor are they regulated with the same intensity. The magnitude of regulation can be gauged from the raw counts and percentages in . In the Constitution of the Czech Republic, the importance of political parties is acknowledged in various domains, each of which is dealt with one single provision. This is in contrast to the Slovak case, for example, which dedicates more attention to extra-parliamentary parties than to the broader question of parties' rights and freedoms or their judicial oversight. Although the range and magnitude of party regulation may in principle vary independently, in practice we find that they are highly correlated. The Croatian and Romanian Constitutions, for example, stand out not only for the extensiveness but also for the range with which parties are regulated (van Biezen and Borz Citation2012, 336–337).

In addition, we can observe an interesting degree of variation between the Eastern European countries with regard to the nature of party constitutionalisation. In Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary, Estonia and Poland, party constitutionalisation predominantly concentrates on the extra-parliamentary party organisation, with one-third to half of all relevant constitutional provisions related to it. This category is also important in Ukraine, Lithuania and Bulgaria, but to a much lesser degree, while it does not appear in the Latvian and Czech Constitutions. The predominant category of constitutionalisation in Romania and Serbia concentrates on party activity and behaviour. The parliamentary party receives relatively little attention, and that only in Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania and Ukraine. Poland, Serbia and Ukraine stand out for being the only countries to regulate political parties in their electoral capacity. Croatia is the only country in the region to constitutionally regulate political parties in the governmental arena. With the only exceptions of Bulgaria, Estonia and Slovenia, a clear identification of political parties with the democratic freedoms of association, assembly and speech can be found in most post-communist democracies. This is a clear legacy of their non-democratic past (van Biezen Citation2012, 201). Judicial oversight constitutes another popular category in post-communist Europe as only four constitutions (i.e. Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine) do not contain any provisions in this area. The Baltic states, Slovakia and Slovenia are the only countries where political parties are not constitutionally associated with democratic principles. The latter two countries, as well as Hungary, Latvia and Serbia, also refuse to regulate the identity and programme of parties. Finally, none of the post-communist constitutions pays any attention to the financial aspect of parties. This is generally in line with the established liberal democracies in Western Europe, with the exception of some Southern European democracies (i.e. Greece, Portugal and Malta) (van Biezen and Borz Citation2012, 337–338; van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014).

While the constitutionalisation of political parties per se has received scarce attention in the academic literature, there has been some scholarly interest in the legal basis of party dissolution. Although the number of works on Eastern Europe is relatively limited, case studies and comparative analyses by legal scholars (e.g. Brunner Citation2000; Sajó Citation2004; Uitz Citation2009) and political scientist (e.g. Bourne Citation2012a, Citation2012b) alike have explored the historical, political and legal parameters of the judicial proscription of party activity, including party bans and dissolution, or the disqualification to participate in electoral contests. Indeed, as also becomes clear from the articles included in this special issue, as well as from the analysis of Party Laws and Constitutions, most East European democracies can be considered to follow the German model of “militant democracy”. Originally coined by Loewenstein (Citation1937), the notion of militant democracy (Streitbare Demokratie in the original) refers to “a form of constitutional democracy authorized to protect civil and political freedom by pre-emptively restricting the exercise of such freedoms” (Macklem Citation2006).Footnote5 Of the countries in this special issue, the Romanian, Polish and Slovak Constitutions establish a general form of judicial control over both party ideologies and activities. The Bulgarian Constitution explicitly prohibits “ethnic, racial and religious” parties, while the Polish Constitution explicitly bans “Nazism, Fascism and Communism” (Casal Bértoa and Walecki Citation2014). In Hungary and the Czech Republic, where both neo-fascist (e.g. MIÉP, Jobbik, RMS) and communist (e.g. Munkáspárt, KSČM) parties have operated in the country almost continuously since the early 1990s, only party activities, but not ideologies, are subject to judicial control. A number of countries have tried to prohibit anti-democratic parties in practice. In 2010, for example, the Czech Supreme Court decided to dissolve the extreme-right Workers' Party after a row of violent attacks on minorities in the country (Bourne Citation2012b) but the party simply responded by changing its name to Workers' Party of Social Justice (DSSS) and kept its programme more or less intact.Footnote6 In Slovakia the Slovak Community-National Party (SP-NS) was dissolved in 2006, despite the constitutionalisation of norms about parties per se, on the grounds that part of its programme was in contradiction with the constitutional principle of non-discrimination against (national) minorities (Casal Bértoa, Deegan-Krause, and Učen, Citation2014). The United Macedonian Organization Ilinden-Pirin (OMO) was banned five years earlier by the Bulgarian Constitutional Court due to its “separatist” nature, although this decision was later overturned by the European Court of Human Rights (van Biezen and Molenaar Citation2012).Footnote7 Earlier in their democratic transitions (1991), both the Latvian and Lithuanian Communist Parties were dissolved “on the grounds that their activities aimed at the violent transformation or overthrow of the existing constitutional order” (Bourne Citation2012a, 1072). Indeed, in a comprehensive content analysis of the patterns of party constitutionalisation in post-war Europe, van Biezen and Borz (Citation2012, 340) conclude that East European democracies are slightly more inclined to emphasise the parties' democratic freedoms of assembly, association and speech while at the same time establishing clear boundaries beyond which the activities of parties cannot be tolerated. As a consequence, according to their threefold classification, the model of party constitutionalisation in Eastern Europe can best be described as “defending democracy”, which rests on a conception of democracy in which parties are endowed with democratic rights and freedoms, but in which party activity and/or identity is at the same time constrained and monitored in order to protect the democratic regime from threats against its core values and principles (van Biezen and Borz Citation2012, 348). Such countries typically curtail the conduct of extremist, insurrectionary, separatist and otherwise “anti-democratic” parties. On this view, the state emerges as the guardian of democracy, with corresponding prerogatives to intrude upon the parties' associational freedoms and their behavioural autonomy (van Biezen Citation2012, 208). This model of democracy tends to predominate in democratic states which are either newly established or re-established after a period of non-democratic rule. As a consequence, and in contrast to a larger degree of variation that can be observed in Southern Europe (van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014), the post-communist region is relatively homogenous in embracing this form of militant democracy.

The development of party legislation

Apart from constitutions, political parties are often regulated in so-called Party Laws, a special piece of legislation specifically targeted at political parties. By Party Laws we understand those laws which are specifically concerned with the regulation of political parties as organisations. Laws that are mainly concerned with particular aspects or activities of political parties, such as elections or finances (electoral laws and party finance laws), are, therefore, excluded from our definition (see van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014).

In contrast to what can be observed in other European regions (e.g. Southern and Northern Europe), in Eastern Europe the regulation of political parties in a specific piece of legislation has been the norm. Hungary was the first post-communist country to do so, but most of the other Eastern European countries soon followed suit: Bulgaria and Poland in 1991, Czechoslovakia in 1991,Footnote8 Croatia in 1993, Estonia and Slovenia in 1994, Lithuania in 1995 and Romania in 1996.Footnote9 The only exceptions to this general rule of regulating political parties immediately after transition have been Ukraine, Latvia and Serbia. In these three countries, a proper Party Law was not passed until after the beginning of the new century (i.e. 2001, 2006 and 2009, respectively).

Modelled on their German counterpart, most post-communist Party Laws regulate both the organisation and the funding of political parties into one single document (Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Serbia and RomaniaFootnote10 constitute the only exceptions) (Casal Bértoa, Piccio, and Rashkova, Citationforthcoming). However, while the Czech, Hungarian, Slovenian and Baltic Party Laws have remained in place with minor modifications, all other post-communist European democracies decided to pass entirely new pieces of legislation with the consolidation of the democratic process around the turn of the century.

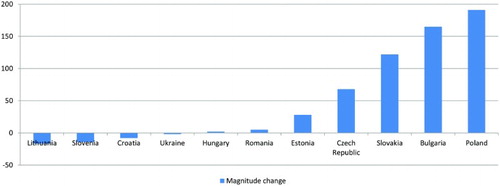

As shown in , the result has been a general increase in the amount of party regulation in most cases, particularly in the East-Central and South-eastern European democracies included in this special issue. This is mainly due to the fact that, while the first Party Laws focused primarily on the necessity to regulate the multiple political forces which started to proliferate at the time of the democratic transitions, the newer Party Laws mainly concentrated on the consolidation of the existing party systems, the strengthening internal party democracy and the transparency of party finances. In this context, it is not surprising that the two most regulated categories are external (mainly judicial) control and the extra-parliamentary party (),Footnote11 closely followed by party (mainly public) finance, but only in those countries without a specific law on party finance.Footnote12 All in all, and with the only exception of Ukraine, it is just to those three categories that all post-communist Party Laws devote roughly 80% of their dispositions. Other issues like participation in elections, parliamentary/governmental activity or media access are left to other (more specific) sets of regulations.

Figure 2. Magnitude change in post-communist Europe (first vs. last – 2011 – regulation).

In this context, Casal Bértoa, Piccio, and Rashkova (Citationforthcoming) have found a substantial degree of convergence between both Western and Eastern European Party Laws, although they differ significantly in both in terms of range and magnitude. In post-communist Party Laws, the range of regulation is considerably higher, encompassing also categories that are either absent or only minimally regulated in their Western European counterparts. This is the case for the parliamentary party (Latvia) or the governmental party (Estonia and Romania), which scarcely receive attention in West European Party Laws. The same is true for the electoral party (Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Romania and Slovenia) or media access (Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine). Moreover, Western and Eastern European Party Laws differ in terms of the magnitude of party regulation, as the post-communist democracies tend to regulate more with considerably more intensity, especially in relation to the party in government, external oversight and secondary legislation.

This is not to say that political parties in post-communist Europe are regulated alike. Indeed, and as we can conclude from the contributions to this special issue, countries differ, for example, in terms of the rules pertaining to the creation, organisation and dissolution of political parties. While most Party Laws oblige parties to have a certain degree of popular support – in the form of a minimum number of signatures and/or members – to be registered, some are considerably more demanding than others. Thus, the minimum number of members ranges from 10 in Hungary, to 200 in Latvia, to 1000 in Poland and the Czech Republic, to 10,000 in Slovakia and to a high of 25,000 in Romania. In Bulgaria, parties are required not only to have at least 2500 members but also to present the signatures of a distinct group of 500 party “founders”. Where changes over time are made, they unequivocally point towards more stringent conditions, even when corrected for possible increases in the voting population. Examples include Bulgaria (from only 50 signatures in 1990 to a combined total of 3050 signatures and party members in 2009), Lithuania (from 400 members in 1990 to 1000 in 2004) and, most significantly, Romania (from 10,000 party members in 1996 to 25,000 in 2003). On top of that, the Romanian law requires party membership to be geographically distributed, while Slovak parties have to pay a moderate registration fee (500,000 SKK). Most post-communist countries have delegated the prerogative to monitor the process of party registration to the judicial authorities; only in the Czech Republic and Slovakia does this prerogative lie with a governmental organ (i.e. Ministry of Interior).

In terms of the impact of party regulation on the parties and party systems, existing scholarship has tended to focus on the question whether restrictive registration requirements (e.g. monetary deposits and/or a minimum number of signatures/members) deters the creation and emergence of new parties. The findings in this context have been mixed. Thus, Tavits (Citation2006, 109) finds that pecuniary registration deposits in Eastern Europe “significantly discourage the emergence of new parties and help to keep existing party systems stable”, while the requirement of a minimum number of signatures for the official registration of a political parties has had the opposite effect (Citation2006, 110–111; see also Tavits Citation2007). More recently, assessing the overall impact of party regulation on the deterrence of new parties, van Biezen and Rashkova (Citation2012, 18) have found that “as regulation increases in range and magnitude, it indeed acts to prevent new parties from successfully crossing the threshold of parliamentary representation”.Footnote13 Higher regulatory thresholds thus appear to make it more difficult for new parties to emerge and consequently have the potential to limit democratic pluralism, an objective that is sometimes actively pursued by the legislator, in particular in systems with relatively high degrees of political fragmentation.

A second aspect in which post-communist Party Laws differ is the intensity with which they interfere in the internal life of party organisations. Indeed, there is considerable variation in terms of the relative emphasis the Party Law places on the internal party organisation. At the same time, however, there is an unequivocal trend towards more regulation, both over time and across countries (van Biezen and Piccio Citation2013). Thus, while the Slovak law leaves the regulation of internal structures and processes entirely at the parties' own discretion, to be dealt with by the party statutes, Bulgarian and Romanian Party Laws exhibit a greater tendency to intervene in the prescription of the internal party organisation, requiring, for example, party congresses to meet periodically. The same can be said of Hungary where, according to Act IV of the 1959 Civil Code, associations (i.e. parties) are not only required to have their own administrative organ and (directly or indirectly elected) self-governing body, but also to convene their highest organ at least once a year. Poland and the Czech Republic are to be found somewhere in the middle: while the Polish Party Law only requires party structures to be democratically elected, Czech parties are also asked to provide for a jurisdictional body where partisan conflicts can be internally resolved. In addition, the Romanian Party Law mandates that congress delegates are elected “by secret vote” (art. 14.1) and introduces requirements for the party organisational structure, such as that internal differences are solved by an “arbitration board” (art. 15.1). Simultaneous membership in multiple parties is legally prohibited in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Romania, although in reality such prohibition is a common practice in all post-communist countries. Romania is furthermore exceptional in that it demands full disclosure of the number of party members, at least “during each pre-electoral year” (art. 27). In Hungary, art. 61 of the Civil Code (previously art. 3 of the 1989 Law on the Right of Association) simply requires associations (i.e. parties) to have a registered membership.

We furthermore observe variation in the extent to which the law requires party organisations to be internally democratic. Only the Party Laws of Poland and the Czech Republic establish such a formal requirement, making internal party democracy a legal precondition for the foundation and operation of political parties. In the Czech Republic, for example, “political parties and movements having no democratic statutes or no democratically elected bodies” may not be established and operate (art. 4.b). With regard to other dimensions of internal party democracy, such as the involvement of party members in the selection of candidates and party leaders, in policy formation or internal decision-making procedures, post-communist Party Laws generally stipulate that specific rules for the implementation of these principles need to be elaborated in the internal party statutes. The legislators thus appear to have considered the principles of internal democracy important enough to demand that they require attention in the party statutes, while at the same time refraining from the legal prescription of specific directives and thus shying away from infringing upon the parties' autonomy and freedom of association of the parties (for a more detailed overview, see van Biezen and Piccio Citation2013).

As in other Western European democracies, Party Laws in post-communist countries also establish that party membership is incompatible with holding certain public offices such as the judiciary, the police or the army from thus further elaborating a principle which in many cases is also constitutionally enshrined. In what can be seen a clear legacy of the communist period, most Eastern European Party Laws furthermore explicitly preserve the separation between political parties and both workplaces (with the only exception of Slovakia, since 2005)Footnote14 and the state. HungaryFootnote15 and Poland constitute the only exceptions in this last respect. A substantial number of countries furthermore explicitly forbid the establishment of religious (Bulgaria) and/or regional parties (Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic and Slovakia until 2005).

Finally, all post-communist Party Laws allow for the dissolution of parties that violate the constitution and/or the law. In Hungary, the most liberal country in this respect, this is the only reason by which parties can be judicially dissolved. In other countries, additional grounds for the judicial dissolution of parties include endangering the morality and/or public order (Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia until 2005); proclaiming fascism and/or an ethnicity/religious principle (Bulgaria until 2001); threatening the rights/freedoms of citizens (Czech Republic), threatening national sovereignty/unity (Romania) or both (Bulgaria and Slovakia, respectively, until 2001 and 2005); organising (para-)military units or activities (Czech Republic, Romania as well as in the first Bulgarian, Polish and Slovak Party Laws); not having democratic statutes or structures (Czech Republic and Slovakia until 2005) and pursuing extra-statutory/programmatic objectives (Romania). Following recent legal reforms, Eastern European parties in some countries can be also judicially terminated in case they fail to meet the deadlines for presenting their financial reports (Poland since 1997, the Czech Republic since 2004 and Bulgaria since 2009) or if they have not convened a meeting of the party's “supreme organ” (party congress) in at least five years (Romania, and Bulgaria since 2009). In a number of countries, moreover, parties need to meet certain requirements for electoral participation. Failure to participate in two consecutive elections constitutes grounds for dissolution in Hungary and Romania, while in Bulgaria (since 2001) parties are at risk of dissolution if they fail to present themselves at elections for a period of more than five years. Romania (since 2003) is exceptional in tying the parties' electoral fortunes to their continued existence: parties who have not obtained 50,000 votes in at least two consecutive elections may be dissolved. The power to dissolve political parties and, consequently, their elimination from the official register, is generally assigned to the judicial authorities. More specifically, this competence may be assigned to an ordinary court (Hungary), the Supreme Court (the Czech and Slovak Republics, Bulgaria until 2001), the Constitutional Court (Poland until 1997), or to both the ordinary and the Constitutional Courts (Romania, Bulgaria since 2001 and Poland since 1997).

Public funding and finance regulation

The funding of political parties undoubtedly constitutes the one of the most examined area of party regulation, also in post-communist Europe. The importance of public funding in particular has received considerable attention since the cartel party thesis was first advanced by Katz and Mair (Citation1995), primarily because the increasing dependence of parties on state subventions was given such “a pre-eminent position as the key indicator of cartelization” (Katz and Mair Citation2009, 754). The introduction of state subventions inevitably demanded a more codified system of party registration and control, as a result of which regulatory frameworks for party finance were introduced, or substantially extended, in the wake of the introduction of public funding

In the post-communist context, scholarly work in this area can be considered to be two-fold. On the one hand, there are those who examine the effects of party finance regulations on the organisational development of political parties, with a special focus on party internal structures and party membership. Whiteley (Citation2011), for example, has argued that the amount of party regulation has acted as a deterrent for the partisan engagement of society, contributing to a decrease in party affiliation everywhere, including Eastern Europe. With regard to the parties' organisational structures, scholars generally agree that while Eastern European parties cannot be considered to be fully “cartelised”, as they tend to be characterised by low levels of professionalisation and the dominance of the central office, their organisations unquestionably share some of its core features (Lewis Citation2000; van Biezen Citation2003; Szczerbiak Citation2003). These include

limited opportunities of party members to influence intra-party life, financial dependence of parties on state subsidies,Footnote16 [ … ] low levels of party affiliation, weak and non-existent links between parties and interest organizations. (Jungerstam-Mulders Citation2006, 244)

On the other hand, and more prominently, scholars have examined the impact of party finance, and especially direct state aid, on party system development and stabilisation. The results in this field have been contradictory, to say the least. Thus, according to some, the introduction of public subsidies has managed to considerably decrease both electoral volatility (Birnir Citation2005) and fragmentation (Booth and Robbins Citation2010),Footnote17 increasing the institutionalisation of the party system as a whole (Casal Bértoa Citation2011). In line with such arguments are other findings that a restrictive regime of public funding, with high eligibility or payout thresholds for state subsidies, serves to maintain the status quo ante, by deterring the formation of the new political forces (Birnir Citation2005; Spirova Citation2007) as well as increasing the costs of survival (Casal Bértoa and Spirova Citation2013). In contrast, other studies have found no clear relationship between finance regulation and party systemic development (Scarrow Citation2006; Tavits Citation2006; Grzymała-Busse Citation2007; Roper and Ikstens Citation2008; van Biezen and Rashkova Citation2012). Let us therefore first explore the nature of party finance regulation in post-communist Europe, and the extent to which it differs from other European regions.

As in Western Europe, where the funding of political parties with state subsidies is a near-universal practice (Scarrow Citation2006; van Biezen and Kopecký Citation2014), the public funding of parties also constitutes the norm in Eastern Europe.Footnote18 This is not to say that post-communist parties were guaranteed access to state aid at the same time or to the same degree. In fact, and as detailed elsewhere (Casal Bértoa and Spirova Citation2013, 9–11), while the Czech Republic, Hungary, Serbia and Slovakia introduced public funding immediately after their transition to democracy (see also van Biezen Citation2003), other countries continued to restrict the funding of political parties to the private sphere (e.g. donations and membership fees) until a later stage. State funding for the ordinary activity of parties was introduced in Croatia and Poland in 1993, in Estonia and Slovenia in 1994, in Romania in 1996, in Lithuania in 1999, in Bulgaria in 2001 and not until 2010 in Latvia. Moreover, post-communist party funding regimes also diverge in the extent to which they let parties have a share of the public pie. Croatia and Serbia, for example, maintain a rather restrictive system of public funding, limiting eligibility for state subsidies only to parties with parliamentary representation. The same was true for Poland, Estonia and Slovenia until 1997, 2000 and 2004, respectively. Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, on the other hand, have adopted a more permissive regime guaranteeing public subsidies also to some extra-parliamentary parties. State funding in Romania is allocated to all political forces with at least 4% of the votes, while in the Slovak and Czech Republics the payout threshold currently stands at 3% and 1.5%, respectively. The most liberal funding system can be found in Hungary, where all parties obtaining at least 1% of the votes are entitled to an allocation from the state budget (Casal Bértoa and Spirova Citation2013). A similar regime can be currently found in Bulgaria, Estonia and Slovenia. While the payout threshold in Hungary and Slovakia has remained essentially unaltered for more than 20 years, the Czech Republic modified it twice: once in 1994, when it was increased from 2% to 3%, and again in 2002 when, following a resolution of the Constitutional Court, the threshold was lowered to 1.5%. Poland lowered its payout threshold from 5% to 3% in 1997. Romania changed its party funding regulation in the opposite direction in 2003 when, among other important changes, the minimum threshold guaranteeing public subsidies to extra-parliamentary parties was raised from 2% to 4% (Casal Bértoa and Spirova Citation2013).

The widespread availability of state support in post-communist Europe has contributed to a financial dependence on the state that is generally quite staggering, with estimates for share of public subsidies to the total party income for the post-communist democracies varying from 60% to 85% (see van Biezen and Kopecký Citation2014). The general predominance of the state in party finance has also led scholars to point to the connection between parties' relatively easy access to public resources and “both high levels of state management of parties and high levels of rent-seeking” (van Biezen and Kopecký Citation2007, 251). In this context, scholars have repeatedly found that, although important improvements to the rules have been made since the early 1990s (Smilov and Toplak Citation2007, 30), the regulation of party finance has not been able to diminish the increasing levels of both party patronage and/or corruption in the region (Roper Citation2002; Smilov and Toplak Citation2007; Kopecký Citation2008; Casal Bértoa et al. Citation2014).

Contrary to most of Western European democracies where, in general, specific Party Finance Laws constitute the norm (Piccio Citation2012; van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014), post-communist countries have tended to regulate party finance in their respective Party Laws. In fact, out of the countries included in this special issue, Romania constitutes the only exception, in that it has both a Party Law and Party Finance Law. Although, it is also important to note here, it did not pass a specific law on party finance until 2003,Footnote19 with a new law adopted in 2006 (Gherghina, Chiru, and Casal Bértoa Citation2011).

summarises the key components of the regulatory frameworks for party financing in the post-communist countries included in this special issue. East-Central and South-eastern European democracies clearly differ not only in the range of parties having access to state aid – although none of them currently limits public subsidies only to parties represented in parliament – but also in the type of direct subsidies to which they are entitled. In this context, it is important to note that Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland also recognised the right of parties to get reimbursed for their “electoral expenses”, although in Poland this is restricted only to parties with parliamentary representation, while Hungary and the Czech Republic also extend this right to extra-parliamentary parties. In terms of indirect public funding, and following the example of their West European counterparts, most Eastern European legislations provide parties with free media access as well as exemption from some or all taxes, with the exception of the Czech Republic and Bulgaria (since 2001). In turn, expenditure limits are in place in Hungary, Bulgaria (since 2001), Poland (since 1997) and Romania (since 2003), but not in the former Czechoslovak Republics.

Post-communist democracies differ also in the extent to which they restrict private funding, scrutinise party financial activities and sanction illegal funding. Thus, while all the democracies studied here ban foreign donations as well as those made by public or semi-public companies,Footnote20 some countries (Romania and Poland) do allow anonymous donations. In these two countries (from 1996 and 1997, respectively) as well as in Bulgaria since 2001, important restrictions apply for the total amounts individuals may yearly donate to a party. Donations from private companies are strictly forbidden in Bulgaria, Poland (since 2001) and Slovakia (since 2005), but allowed in the others.

In terms of the transparency of the financial activities of political parties, all post-communist regulations establish the obligation to submit annual financial reports. While in Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic such an obligation was already in the original pieces of legislation, in Bulgaria, Poland and Romania it was only introduced with the approval of the major legislative reforms that occurred later.

In terms of various ways in which the financial activities of political parties are controlled and supervised, most post-communist countries provide for one type or other of administrative control: the State Audit Office in Hungary, the National Electoral Commission in Poland, the Ministry of Finance in Slovakia, the Court of Accounts and the Permanent Electoral Authority in Romania, with the latter added as a monitoring body in 2008 (GRECO Citation2010, 17–18). Only in the Czech Republic does such financial control have mainly a parliamentary character, in that a committee of the Chamber of Deputies (so-called Supervisory Committee) checks on an annual basis whether parties’ financial reports have been submitted in a complete manner.Footnote21 Both the type and intensity of financial control has changed over the years: from none to administrative oversight in Poland and Romania, or to both internal (i.e. by partisan-nominated independent financial auditor) and administrative in Bulgaria, and from exclusively parliamentary to a mixed form of parliamentary and administrative monitoring in Slovakia.Footnote22

Finally, party funding regulations have established different sanction regimes. In Bulgaria, Hungary and the Czech Republic, pecuniary fines in cases of illegal party funding have existed since the very early stages of party finance regulation. The rest of the countries in the region introduced such monetary sanctions at a later stage: Poland in 1997, Romania in 2003 and Slovakia in 2005. Out of these three countries only Poland (since 2001) and Romania (since 2006) allow also for criminal sanctions, such as the imprisonment of those who violate the law. In both Hungary and the Czech Republic such a possibility was already contemplated in their corresponding Criminal Laws.

In this special issue

As follows from the above, post-communist countries have regulated political parties to a different extent () and in different ways ( and ). As a result, the impact of party regulation on party politics is likely to vary among countries. Using original quantitative and qualitative data, this special issue constitutes an attempt to systematically cast theoretical and empirical light on the manner in which the constitutional and legal regulation of party organisations and finances have had an impact (or not) on the consolidation of party politics in the Eastern European region since 1989. In this context, it clearly complements a previous study on the relationship between party regulation and party system development in Southern Europe (van Biezen and Casal Bértoa Citation2014).

Table 2. Party Laws (first and current) in post-communist Europe: key components.

Table 3. Party funding regulations (first and current) in post-communist Europe: key components.

All articles included in this special issue start with a chronological examination of the specific rules and regulations governing political parties, followed by an in-depth diachronic analysis of the effects of such legislation on certain aspects related to party and/or party system development. Thus, Rashkova and Spirova explore the consequences of a rather generous party funding regime in combination with relatively restrictive requirements for electoral participation on the fate of Bulgarian political forces in general, and small parties in particular. Distinguishing two different regulatory periods (before and after 2001), their article uncovers the tension between the costs (i.e. deposit fees and signatures) and benefits (i.e. public subsidies) of electoral participation. Their main conclusion is that, while the former have tended to discourage the formation of new political parties, the latter has guaranteed the stability of those political forces that have managed to obtain at a minimal degree of popular support even (i.e. 1% of the vote).

For Poland, Casal Bértoa and Walecki arrive at a similar conclusion in relation to the importance of guaranteeing state financial support to extra-parliamentary parties. According to them, public money has been the main reason behind the survival of historical parties like the Freedom Union (currently known as the Democratic Party) and the Labour Union. In contrast to Rashkova and Spirova's findings for Bulgaria, Casal Bértoa and Walecki do not find convincing evidence for a relationship between the number of signatures required for party registration and party formation. On the other hand, while Polish parties and voters’ preferences have continuously changed independently of the party funding regime, the growing financial dependence of parties on the state has produced an increasing “cartelisation” (mainly in terms of centralisation and professionalisation) of the country's political organisations.

The analysis of the Slovakian case by Casal Bértoa et al. suggests that a clear distinction needs to be made between the impact of party regulation on the party system, on the one hand, and the party organisations, on the other. In relation to the systemic level, the overall impact of Slovakia's regulatory regime seems to be negligible. Regarding the individual parties, however, the authors point to a clear effect of public subsidies on party survival, especially for those parties above the payout threshold. However, and contrary to what can be observed for the Polish case, state aid in Slovakia has not functioned as a mechanism for rescuing extra-parliamentary parties from obliteration. In terms of party funding, their contribution also points to the limits of regulation by making a distinction between the concrete content of the law and how it is actually applied in everyday politics. The tension between legal texts and their practical implementation is also emphasised in the contributions by Haughton, on the Czech Republic, and Popescu and Soare, on Romania.

These latter two articles also coincide on the pernicious effects party regulation may have. Focusing on the role of money in Czech politics, Haughton arrives at the conclusion that while “permissive” in principle, party regulation in general, and party funding in particular, has had an “ultimately restrictive” impact on the evolution of the country's party system since 1991, contributing to its initial “cartelisation”, a condition which proved to be long-lasting but fragile, eventually producing public discontent that helped dislodge the major parties from their dominant position. In this context, Haughton also places attention to the role played by the Constitutional Court in curtailing some of the legal reforms (e.g. electoral system and payout threshold) proposed to protect the parties in the “cartel” (mainly Občanská demokratická strana (Civic Democratic Party) and Česká strana sociálně demokratická (Czech Social Democratic Party)).

In their article on the impact of party regulation on the development of Romanian politics since the overthrow of Ceausescu in 1989, Popescu and Soare point to three main effects: party system concentration, electoral volatility reduction and cabinet stability. In addition, they raise the question about the goals of legislative engineering and design in the field of party regulation and try to answer to the question whether party system institutionalisation constitutes a legitimate goal for parties regulating themselves. Their answer for the Romanian case, which might also be relevant for the other new democracies, is that party regulation has generally left the parties and political elites satisfied but has produced the opposite effect among the voters, producing widespread public discontent, even as it limits the ability of that discontent to find political outlets in new parties.

Ilonszki and Várnagy, in their contribution on Hungary, take a slightly different approach and, adopting an integrated perspective, treat party regulation both as a dependent and independent variable. More so than the other contributions in this special issue, which deal with the motivations underlying the legal recognition and regulation of political parties in a more implicit manner, Ilonszki and Várnagy mainly focus on the consensual determinants of non-legislative reform and examine how the Hungarian legislature has reacted most recently to the rising levels of ideological polarisation in the country. Their main conclusion is that the “winner-takes-all” character of the current party regulation is essentially the consequence of the failure of the previous regulation to produce the expected (i.e. consensual-cum-stabilisation) effects.

In sum, by dealing with the most important legal texts, including but not limited to Constitutions, Party Laws and Party Funding Laws, and key aspects of party legislation, encompassing the creation and dissolution of parties, their internal organisation and financial activities, this special issue aims not only to shed light on the different regulatory frameworks but also on the possible consequences of party regulation in Eastern Europe. All in all, the analysis of the six post-communist cases under study seems to be the following: the regulation of political parties in the region has produced very mixed, sometimes even contradictory, effects. Thus, while in some cases it seems to have contributed to “collusion” of the main parties at the systemic level (e.g. Romania and, to a lesser extent, the Czech Republic), in others such “cartelisation” effects have taken place only at the level of party organisations (e.g. Poland). Still in others the impact of party regulation seems to have been either limited (e.g. Slovakia) or virtually inexistent (e.g. Hungary). This variation is observed in the region despite clear commonalities in the way political parties have been regulated, namely: a “militant” model of democracy; increasingly restrictive registration requirements (with the exception of Hungary); moderate intervention in parties' internal matters (with the exception of Romania); strong state subsidisation; and a weak system of financial controls and sanctions.

Funding

Financial support from the European Research Council (ERC_Stg07_205660) is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes on contributors

Fernando Casal Bértoa is a Nottingham Research Fellow at the School of Politics and International Relations. He is also co-director of the Centre for Comparative and Political Research (http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/ccpr/index.aspx) at the University of Nottingham. His work has been published in Party Politics, Government and Opposition, International Political Science Review, South European Society and Politics, and East European Politics.

Ingrid van Biezen is Professor in Comparative Politics at Leiden University. She is a co-editor of Acta Politica, a former co-editor of the European Journal of Political Research (EJPR) Political Data Yearbook and the author of Political Parties in New Democracies (Palgrave 2003). She has published extensively on comparative party politics, political finance and democratic theory in, among other journals, the British Journal of Political Science, the European Journal of Political Research, Party Politics, Perspectives on Politics, and West European Politics.

Notes

1. This special issue forms part of a larger research project on the legal regulation of political parties in post-war European democracies. For more details about the project, see www.partylaw.leidenuniv.nl.

2. In 1992, Poland adopted a provisional and so-called small constitution, which repealed part of the Communist Constitution of 1952. The adoption of a new constitution, approved by national referendum, did not occur until 1997 (van Biezen Citation2012, 197; Casal Bértoa and Walecki Citation2014).

3. According to art. 29.2 of the 1992 Slovak Constitution, “citizens have the right to establish political parties and political movements and to associate in them”.

4. Other exceptions are the three Baltic states and Slovenia.

5. For a more elaborated definition of the concept and its possible variants, see Thiel (Citation2009) and Bourne (Citation2012b).

7. Although party leader (Stojko Stojkov) subsequently made a new attempt to register his party, this was unsuccessful as registration was denied by Sofia's City Court on the grounds that the constituent meeting had not achieved the required quorum.

8. After the so-called Velvet Revolution, this law (424/1991) was subsequently adopted by the two newly independent states without any major modifications (see Haughton Citation2014 and Casal Bértoa, Deegan-Krause, and Učen, Citation2014).

9. Trying to establish the legal foundation for the newly founded pluralistic regime, the five-article long Decree-Law 8/1989 contained dispositions on the registration and functioning not only of political parties but also on public organisations more generally (see Popescu and Soare Citation2014). The same is true for Czechoslovakia's one and a half page-long 15/1990 “law on political parties” (see Casal Bértoa, Deegan-Krause, and Učen, Citation2014).

10. Following the more general post-communist pattern, the first Romanian Party Law also included party funding dispositions.

11. Differently to what it has been said regarding party constitutionalisation, Party Law provisions related to media use by political parties are grouped in the media access category.

12. Ukraine, where direct public funding is not available to political parties, constitutes the only exception.

13. For a different conclusion, see Bischoff (Citation2006), who finds that registration requirements do not have any significant effect on the number of new parties.

14. Although the 1993 Slovak Constitution continues to require the separation between political parties and the state.

15. In Hungary, member of the state administration can be party members, although they cannot be elected to party positions (art. 85 of the new 2011 Law on the Right of Association, Non-profit Status, and the Operation and Funding of Civil Society Organizations).

16. With the notable exception of both communist parties and their successors (Walecki Citation2001, 414).

17. These authors also found that restrictions of private funding also discourage fragmentation, provided that public subsidies are not made available (Citation2010, 644).

18. Malta and Switzerland are the only West European countries where public funding to national parties has not been introduced. In the same vein, public subsidies are not available to parties in Ukraine (Piccio Citation2012).

19. Until that year, and as it is the case of its Eastern European counterparts, party finance regulation was mostly contained in the 1996 Party Law.

20. While Poland forbade public donations only in 1997, Slovakia did not ban donations made by foreigners until 2005.

21. Such “external” control is complemented “internally” with the opinion of an auditor appointed by the parties themselves.

22. It is important to note here, though, that both the Czech and Bulgarian (since 2001) Party Laws oblige parties to pursue an “internal” auditing of their finances.

References

- Avnon, D. 1995. “Parties Laws in Democratic Systems of Government.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 1 (2): 283–300. doi: 10.1080/13572339508420429

- van Biezen, I. 2003. Political Parties in New Democracies: Party Organization in Southern and East-Central Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- van Biezen, I. 2008. “State Intervention in Party Politics: The Public Funding and Regulation of Political Parties.” European Review 16 (3): 337–353.

- van Biezen, I. 2012. “Constitutionalizing Party Democracy: The Constitutive Codification of Political Parties in Post-war Europe.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (1): 187–212. doi: 10.1017/S0007123411000263

- van Biezen, I., and G. Borz. 2012. “Models of Party Democracy: Patterns of Party Regulation in Post-War European Constitutions.” European Political Science Review 4 (3): 327–359. doi: 10.1017/S1755773911000294

- van Biezen, I., and F. Casal Bértoa. 2014. “Party Regulation in Post-authoritarian Contexts: Southern Europe in Comparative Perspective.” South European Society and Politics 19 (1): 71–87. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2014.888275

- van Biezen, I., and P. Kopecký. 2007. “The State and the Parties. Public Funding, Public Regulation and Rent-Seeking in Contemporary Democracies.” Party Politics 13 (2): 235–254. doi: 10.1177/1354068807073875

- van Biezen, I., and P. Kopecký. 2014. “The Cartel Party and the State: Party-State Linkages in European Democracies.” Party Politics 20 (2): 170–182. doi: 10.1177/1354068813519961

- van Biezen, I., and F. Molenaar. 2012. “The Europeanization of Party Politics? Competing Regulatory Paradigms at the Supranational Level.” West European Politics 35 (3): 632–656. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.665744

- van Biezen, I., and H. M. ten Napel, eds. Forthcoming. Regulating Political Parties: European Democracies in Comparative Perspective. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- van Biezen, I., and D. R. Piccio. 2013. “Shaping Intra-party Democracy: On the Legal Regulation of Internal Party Organizations.” In The Challenges of Intra-party Democracy, edited by William Cross and Richard S. Katz, 27–48. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- van Biezen, I., and E. R. Rashkova. 2012. “Deterring New Party Entry? The Impact of State Regulation on the Permeability of Party Systems.” Party Politics. http://ppq.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/09/23/1354068812458616.abstract

- Birnir, J. K. 2005. “Public Venture Capital and Party Institutionalization.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (8): 915–938. doi: 10.1177/0010414005275429

- Bischoff, C. S. 2006. “Political Competition and Contestability: A Study of Barriers to Entry in 21 Democracies.” PhD diss., European University Institute, Florence.

- Booth, E., and J. Robbins. 2010. “Assessing the Impact of Campaign Finance on Party System Institutionalization.” Party Politics 16 (5): 629–650. doi: 10.1177/1354068809342994

- Bourne, A. 2012a. “Democratization and the Illegalization of Political Parties in Europe.” Democratization 19 (6): 1065–1085. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.626118

- Bourne, A. 2012b. “The Proscription of Parties and the Problem with ‘Militant Democracy’.” The Journal of Comparative Law 7 (1): 196–213.

- Brunner, Georg. 2000. “The Treatment of Anti-constitutional Parties in Eastern Europe.” In Human Rights in Russia and Eastern Europe, edited by Ferdinand Feldbrugge and William B. Simons, 15–34. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer International Law.

- Casal Bértoa, F. 2011. It's Mostly about Money! Party System Institutionalization and Its Sources: Reducing Causal Complexity in Post-communist Europe. The Legal Regulation of Political Parties Working Paper Series (n. 15). http://www.partylaw.leidenuniv.nl/uploads/wp1511.pdf

- Casal Bértoa, F., K. Deegan-Krause, and P. Učen. 2014. “The Limits of Regulation: Party Law and Finance in Slovakia (1990–2012).” East European Politics 30 (3).

- Casal Bértoa, F., F. Molenaar, D. R. Piccio, and E. R. Rashkova. 2014. “The World Upside Down: De-legitimising Political Finance Regulation.” International Political Science Review 35 (3): 355–376.

- Casal Bértoa, F., D. R. Piccio, and E. R. Rashkova. Forthcoming. “Party Laws in Comparative Perspective: Evidence and Implications.” In Regulating Political Parties: European Democracies in Comparative Perspective, edited by I. van Biezen and H. M. ten Napel. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Casal Bértoa, F., and M. Spirova. 2013. Get a Subsidy or Perish! Public Funding and Party Survival in Eastern Europe. The Legal Regulation of Political Parties Working Paper Series (n. 29). http://www.partylaw.leidenuniv.nl/uploads/wp2913.pdf

- Casal Bértoa, F., and M. Walecki. 2014. “Regulating Polish Politics: ‘Cartel’ Parties in a Non-Collusive Party System.” East European Politics 30 (3).

- Gherghina, S., M. Chiru, and F. Casal Bértoa. 2011. “Resursele statului s’i bani de buzunar: Finant’area partidelor politice românes’ti în perioada postcomunistă.” In Voturi s’i politici: dinamica partidelor românes’ti în ultimele două decenii, edited by Sergiu Gherghina, 235–256. Iasi: Editura Institutul European.

- GRECO. 2010. Third Evaluation Round. Evaluation Report on Romania on Transparency of Party Funding (Theme II). Strasbourg, November 29–December 3. http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/monitoring/greco/evaluations/round3/GrecoEval3(2010)1_Romania_Two_EN.pdf

- Grzymała-Busse, A. 2007. Rebuilding Leviathan: Party Competition and State Exploitation in Post-communist Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, P. A., and R. C. R. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Haughton, T. 2014. “When Permissiveness Constrains: Money, Regulation and the Development of Party Politics in the Czech Republic (1989–2012).” East European Politics 30 (3): 372–388.

- Janda, K. 2005. Adopting Party Law. Working Paper Series on Political Parties and Democracy in Theoretical and Practical Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs.

- Jungerstam-Mulders, S. ed. 2006. Post-Communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Karvonen, L. 2007. “Legislation on Political Parties: A Global Comparison.” Party Politics 13 (4): 437–455. doi: 10.1177/1354068807077955

- Katz, R. S. 2002. “The Internal Life of Parties.” In Political Challenges in the New Europe: Political and Analytical Challenges, edited by Kurt Richard Luther and Ferdinand Müller-Rommel, 87–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Katz, R. S., and P. Mair. 1995. “Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: the Emergence of the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 1 (1): 5–28. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001001

- Katz, R. S., and P. Mair. 2009. “The Cartel Party Thesis: A Restatement.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (4): 753–766. doi: 10.1017/S1537592709991782

- Kopecký, P., ed. 2008. Political Parties and the State in Post-communist Europe. London: Routledge.

- Lewis, P. G. 2000. Political Parties in Post-communist Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Loewenstein, K. 1937. “Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights I.” The American Political Science Review 31 (3): 417–432. doi: 10.2307/1948164

- Macklem, P. 2006. “Militant Democracy, Legal Pluralism, and the Paradox of Self-determination.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 4 (3): 488–516. doi: 10.1093/icon/mol017

- March, J. G., and J. P. Olson. 1984. “The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life.” American Political Science Review 78 (3): 734–749. doi: 10.2307/1961840

- Müller, W. C., and U. Sieberer. 2006. “Party Law.” In Handbook of Party Politics, edited by Richard S. Katz and William Crotty, 435–445. London: Sage.

- Piccio, D. 2012. Party Regulation in Europe: Country Reports. Working Paper Series on the Legal Regulation of Political Parties (no. 18). http://www.partylaw.leidenuniv.nl/uploads/wp1812a.pdf

- Popescu, M., and S. Soare. 2014. “Engineering Party Competition in a New Democracy: Post-communist Party Regulation in Romania.” East European Politics 30 (3): 389–411.

- Roper, S. D. 2002. “The Influence of Romanian Campaign Finance Laws on Party System Development and Corruption.” Party Politics 8 (2): 175–192. doi: 10.1177/1354068802008002002

- Roper, S. D., and J. Ikstens, eds. 2008. Public Finance and Post-communist Party Development. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Sajó, A. 2004. “Militant Democracy and Transition Towards Democracy.” In Militant Democracy, edited by András Sajó, 209–230. Utrecht: Eleven International Publishing.

- Scarrow, S. 2006. “Party Subsidies and the Freezing of Party Competition: Do Cartel Mechanisms Work?” West European Politics 29 (4): 619–639. doi: 10.1080/01402380600842148

- Smilov, D., and J. Toplak, eds. 2007. Political Finance and Corruption in Eastern Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Spirova, M. 2007. Political Parties in Post-communist Societies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Szczerbiak, A. 2003. “Cartelization in Post-communist Politics: State Party Funding in Post 1989 Poland.” In Pan-European Perspectives on Party Politics, edited by Paul Lewis and Paul Webb, 127–150. Leiden: Brill.

- Tavits, M. 2006. “Party System Change: Testing a Model of New Party Entry.” Party Politics 12 (1): 99–119. doi: 10.1177/1354068806059346

- Tavits, M. 2007. “Party Systems in the Making: the Emergence and Success of New Parties in New Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 113–133.

- Thiel, M., ed. 2009. The “Militant Democracy” Principle in Modern Democracies. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Uitz, R. 2009. “Hungary.” In The ‘Militant Democracy’ Principle in Modern Democracies, edited by Markus Thiel, 147–182. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Walecki, M. 2001. “Political Finance in Central Eastern Europe.” In Foundations for Democracy. Approaches to Comparative Political Finance, edited by Karl-Heinz Nassmacher, 393–414. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag.

- Whiteley, P. 2011. “Is the Party Over? The Decline of Party Activism and Membership across the Democratic World.” Party Politics 17 (1): 21–44. doi: 10.1177/1354068810365505