Abstract

This article analyses the LiveJournal blog of the well-known Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny during the period from 2006 to 2012. The blog is analysed through the prism of nationalism and identity construction. The analysis shows that Navalny advocates a “normal” nationalism, which he contrasts with abnormal, radical, and marginal nationalism. He underlines the importance of national rebirth and constructs Russian national identity in connection to a history of victory and greatness. The national identity that Navalny constructs is ethnically Russian. Other ethnic groups, Chechens in particular, are constructed as “Others” who belong outside the boundaries of the Russian imagined community.

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed the dual tendencies of growing nationalism and dwindling religious tolerance in many European countries, including Russia. Some see these tendencies as an outcome of globalisation processes, fuelled by the effects of the ongoing financial crisis – but the Russian case is slightly different. Russia has always been a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state. However, almost 20 years of conflict and anti-terror campaigns in the North Caucasus have resulted in deep divisions in Russia along ethnic and religious lines. There is clear evidence of growing hostility among ethnic groups in Russia – the October 2013 riots in Biryulyovo, Moscow are a vivid example. The focus on the rights of ethnic Russians in the debates about Crimea during winter and spring 2014 underlines the importance of ethnic identity in Russian political rhetoric. In this context, it is vital to analyse the boundaries constructed between ethnic groups as well as the “Othering” discourse articulated by leaders in today's Russia. The main objective of this article is to provide an outline of this type of social construction inductively, through the prism of Alexei Navalny's blog.Footnote1

The focus here is on how Navalny uses his blog to construct nationalism as a normal phenomenon and how he discursively connects “normal nationalism” to certain “in” and “out” groups in today's Russia. In doing this, he identifies which groups are placed within the Russian “imagined community” and which are positioned as “the Other” [see Neumann (Citation1999) for a broad discussion of this term], building on and contributing to the construction of Russian national and ethnic identity. Thus, this article examines nationalism as a discourse that is constitutive of individuals' identities. Depending on the source of this articulation, the “in” and “out” groups constructed through such discourse may contribute to patterns in concrete policy-making. The articulation of nationalistic discourse by an ambitious figure in the Russian political field is by no means unique. As noted by Laruelle, nationalist issues under the label of “patriotism” are central components of Russian political language; in fact, “no public figure ( … ) is able to acquire political legitimacy without justifying his or her policy in terms of nation's supreme interest” (Citation2009a, 1). This is also the discursive field where Navalny has been actively positioning himself. Furthermore, the LiveJournal blog can also serve as a valuable tool for accessing the discourses that were formulated by this young Moscow lawyer before he became the well-known political figure he is today.

Alexei Navalny is arguably the most influential opposition figure in Russia today. Time Magazine named him one of the world's 100 most influential people in 2012 (Kasparov Citation2012). His participation in the Moscow mayoral elections in September 2013 further boosted his popularity and his image as a rising star in Russian politics, and as the very symbol of the changing political environment (see e.g. Orttung Citation2013; Waller Citation2013 on Navalny and the elections). Navalny is an active user of various social networks such as LiveJournal, Twitter, Facebook, and VKontakte; his messages are read by millions of people every day. Furthermore, he has been actively involved in the shaping of the national idea in Russia; in 2011, he was a member of the organisation committee of Russian MarchFootnote2 and also took part in the rally “Stop feeding the Caucasus”.Footnote3

Many have speculated about Navalny's political position, his beliefs, and the role he will play in the future of Russian democracy. Critics have branded him a nationalist, and warned against his anti-immigrant attitudes. Is he a true nationalist – or is his flirtation with nationalism purely a matter of political calculation? (Popescu Citation2012, 51). In a recent article, Laruelle (Citation2014) analyses Navalny's successes and failures in reconciling “nationalism” with “liberalism”, and finds that, even with no clearly formulated ideology, he nonetheless enjoys political success.

The political success of Navalny is the reason why the ideas disseminated on his blog merit thorough examination and should be recognised as interesting in their own right. Laruelle (Citation2014, 12) also points out the popularity Navalny enjoys as indicative of “the xenophobic mood of the new middle classes”. Thus, the present article can be indicative of the discourses that shape this xenophobic mood and also point the reader towards the arguments that contribute to Navalny's popular appeal. It is a unique exploratory in-depth study of the writings of a political figure in whom many are interested, but whose nationalist discourse is less widely understood.

My theoretical point of departure here is Benedict Anderson's concept of “imagined communities”, whereby a nation can be seen as an imagined community, with the individual's national identity being based on his or her positioning within this community: “( … ) imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives an image of their communion” (1991, 6). In this article, the concept of imagined communities is combined with Fredrik Barth's ideas about the social boundaries that define ethnic groups (Barth Citation1969). Sometimes such boundaries are congruent with national borders – other times they are not. I use “imagined community” exclusively with reference to ethnic and national identities. Because this article focuses on the construction of such identities, it belongs within the post-structural theoretical framework of social constructionism which sees our perceptions of the world we live in as socially constructed and formed by history and the discourses dominant in various historical periods (Burr Citation2003). With that in mind, I analyse the imagined communities constructed by Navalny and how he positions himself in relation to a nationalistic discourse through a prism of language and discourse.

Others have pointed out that Navalny articulates a nationalistic discourse, but neither the extent of such discourse on his blog nor the content of this discourse has been thoroughly explored. If Navalny is indeed a nationalist, what then is his nationalistic message? Politicians attempt to unite “the people” through specific ideas about the nation and national identity – What kind of national identity is constructed by Navalny? This article analyses: the extent of nationalistic discourse on Navalny's blog (2006–2012); the content of this discourse; and the Russian identity and the subject position of “the Other” articulated through this discourse. This analysis will address four main research questions:

To what extent has Alexei Navalny used his blog on LiveJournal to articulate ideas of nationalism?

While the first question focuses on the prevalence of the discourse, the three remaining questions focus on its content:

What is nationalism, according to Navalny – how does he construct “nationalism”?

A construction of nationalism of any kind includes certain ideas about “us” and “them”. Thus it is reasonable to ask two further questions:

How does Navalny articulate the Russian identity (within the context of nationalistic discourse)?

How does Navalny construct the images of “Others” positioned outside the boundaries of the Russian imagined community?

I begin by establishing the frame for the analysis, starting with a brief review of the literature of about nationalism in general and Russian nationalism in particular. In order to give an account of the theoretical framework which shapes the analysis in this article, the social constructionist ideas about language, discourse and construction of identity through articulation of subject positions are then explained. The final factor to be accounted for in setting the context for this study is the recent development of the political use of the Internet in Russia.

The second part of the article focuses on the analysis of empirical data gathered from Navalny's blog. This will show how Navalny constructs nationalism as “normal”, in opposition to forms of “abnormal nationalism”, and positions “Russians” as victorious and a great people. In addition, the two main subject positions of “the Other” are clear in Navalny's blog posts: a person from the North Caucasus, most often Chechen; and a migrant from the Near Abroad, most often from Azerbaijan or Tajikistan. The usage is not unique to Navalny: according to, for example, Verkhovsky (Citation2009), these groups of “Others” feature commonly in Russian discourse that expresses xenophobia aimed at migrants.

Nationalisms

Some scholars emphasise the distinction between two types of nationalism – “politically oriented nationalism” and “culturally oriented nationalism” (Kohn Citation1944; Jaskułowski Citation2010) or civic and ethnic nationalism (e.g. Greenfeld Citation1992). Others have criticised this distinction as being reductionist and as having led many scholars to characterise entire nations as being civic or ethnic – with the former being predominantly Western and latter Eastern (Jaskułowski Citation2010; Shulman Citation2002). In fact, it is difficult to characterise the nationalism that exists in Russia today as either civic or ethnic. The picture is complex, with both types of nationalism present in Russian discourse and in identity construction. There are two words in the Russian language that are used with reference to ethnic or ethnocultural (Laruelle Citation2014, 5) identity (russkiy) and civic identity (rossiyskiy), respectively. This is, among other things, a result of two distinct historical processes in Russia – the building of a civic nation until 1917 and the construction of an ethnic nation in Soviet times, based on real and imagined ethnic differences (Volkogonova and Tamorenko Citation2001, 155).

Studies of Russian nationalism have traditionally distinguished between ethno-nationalism and Eurasianism, the latter including those who are nostalgic for the greatness of imperial or Soviet past (Laruelle Citation2014, 2). However, according to Verkhovsky (Citation2009), the old dichotomy of ethnic versus imperial nationalism is gradually falling into disuse; the nationalism currently dominant in Russia is almost exclusively ethnic. Even in statist discourse, ethno-nationalist traits are combined with imperialist designs (Laruelle Citation2009b, 43). The analysis in this article will show that Navalny's nationalism is also predominately ethnic.

In the context of Russian politics, nationalism is a “flexible ideological instrument that can be used with almost any political toolkit” (Laruelle Citation2014, 18). In terms of discourse theory, “nationalism” can be seen as a “nodal point”, a core point that several discourses have been struggling to define in various ways (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001). The ambiguity of “nationalism” may be made more evident by identifying some of the prisms through which this phenomenon has been studied in the Russian context.Footnote4

Some scholars have studied Russian nationalism as it relates to patriotism (Blum Citation2006; Sperling Citation2009). Patriotism is linked to the idea of “the Great Russian people” which, according to Vujacic (Citation2007), originated in the Stalin era and is part of the Soviet legacy. Russian–Soviet nationalism developed around the idea of a people who were victorious against fascism during the Second World War (Laruelle Citation2009b, 36); ensuing regimes have continued to link patriotism with the defeat of the Nazis by the Soviet Union. Since the turn of the millennium, it has been the stated ambition of the regime to foster patriotism in Russian youth, through the Programme for Patriotic Education (Sperling Citation2009) – a programme dedicated to fostering such key values as national identity, social order, state strength and the symbolic role of the military in all these (Blum Citation2006). “As such patriotism is understood as an integral part of the emergence of a cohesive and self-confident Russia, capable of asserting itself as a great power on the world stage” (Blum Citation2006, 2).

Other studies have viewed nationalism in relation to fascism (Umland Citation2009) and right-wing politics (Nozhenko Citation2013). There are many fascistic groups and other right-wing groups in Russia today, particularly evident at Russian March and other events organised by the Movement Against Illegal Immigration (DPNI). According to Umland (Citation2009) and Laruelle (Citation2009b), usage of the term “fascism” in Russian discourse has suffered from “hyperinflation” and has been applied to denote “German Nazism”. This attempt to define nationalism in terms of fascism or Nazism stands in direct opposition to the type of patriotic nationalism that emphasises the Soviet struggle against the Nazis in the Second World War.

Another approach to studying nationalism in the Russian context is by exploring its linkages with xenophobia (Herrera and Butkovich Kraus Citation2013) – or “migrant-phobia” (migrantofobia) (Verkhovsky Citation2009). According to Verkhovsky (Citation2009), the migrant-phobic discourse enjoys widespread support throughout Russian society. He cites the DPNI as an example of how quickly popularity can be gained by using the “fight against migrants” and “illegal migrants” (Verkhovsky Citation2009).

The analysis in this article shows how Navalny combines many of the elements discussed above when he articulates a nationalistic discourse in his blog. He constructs nationalism as a combination of patriotism, ethno-nationalism, migrant-phobia, and anti-fascistic discourse. The elements featuring in his discourse are not new: they represent a re-articulation of already prevalent discursive constructions and combination of these under the label of normal nationalism.

Words are important

The main assumption of the underlying theory perspective employed in this article is that words are important. That is, words do have a central role in the construction of our everyday realities, and they may serve as a dividing or a unifying force for a nation and its people. The article draws on discourse analysis, which can be seen as both a theoretical approach and a methodology (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). A “discourse” is a system for conveying expressions and practices that are reality-constitutive and that exhibit a certain degree of regularity (Neumann Citation2001, 17). A discourse is the premise for the creation of meaning in any historical, social, or political context.

Discourse analysis is an important part of political analysis – discourse simultaneously legitimises and reflects specific political practices and political views. It delineates what is “say-able” in particular contexts. The kind of nationality discourse study undertaken here can shed light on the connection between power and knowledge in the Foucauldian sense, as there is a relationship between individual knowledge which produces new concepts and the way in which new phenomena suddenly arise (Foucault Citation2000). Knowledge of various phenomena contributes to their construction; it is disseminated through discourse, manifesting itself as a discursive form of power. Thus, in this article, I see the national question in Russia as being shaped by the discourses that address it.

Discourses offer subject positions in which the individual is positioned (Davies and Harré Citation2007; Foucault Citation2008). An individual's identity is shaped by the subject positions in which he or she is positioned in various discourses – this could be Russian, Soviet, or Chechen, but also sister, teacher, feminist … “Nationalism” becomes a discourse and “nationalist” is a subject position.

The field of action for the people occupying various subject positions is shaped by the discourses through which these positions are articulated. Mapping the subject positions available in Russia's nationality discourse today can thus provide important insights on the opportunities for different groups and on the Russian imagined community as a whole – as well as showing how Russian national identity is shaped in relation to “Others”. Our identities are constitutive and relational; they depend on our ability to see the world through distinctions between “us” and “them”. “We” are the group that we feel we belong to; and “they” are the group we neither can access nor have any wish to belong to (Bauman and May Citation2001). “They” are the “Others”.

Words themselves are important – but so are the ways in which words are disseminated. Discourse is spread and social phenomena are constructed through processes of communication. Anderson (Citation1991, 46) links the development of print media to the formation of “nation” and national community, arguing that the convergence of capitalism, print technology, and language has created the possibility of the modern nation as a new form of imagined community. Globalisation processes like migration and the development of the Internet have expanded the borders of such imagined communities. National languages are no longer contained within national borders, and individuals use the Internet to connect with their communities around the globe. New social boundaries are developed, cutting across and within actual geographical borders. Specifically, this article focuses on how such boundaries are constructed through Russian Internet (RuNet).

The use of social networks, such as blogs, has become extremely popular among RuNet users. As of 18 September 2013, there were more than 90 million blogs on RuNet. On the other hand, according to the Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communication (Citation2010), only 10% of all blogs are updated at least once a month and can be considered “active”. LiveJournal.com has both the most active bloggers and the highest number of active blogs on RuNet (Toepfl Citation2012). The Internet has become a popular medium for political activity, and various political actors are very active online – mostly through blogs on LiveJournal, but also other social networks such as Twitter and Facebook (see Oates Citation2012; Renz and Sullivan Citation2013; Schmidt Citation2012; Toepfl Citation2012; Yagodin Citation2012).

As Bode and Makarychev (Citation2013, 61) point out, the “power of the new social networking lies in their ‘direct manifestation of social activism’ and in opening up new social spaces ‘to facilitate spontaneous utterances and participation’”. In recent years, the watchdog function of the RuNet has also been strong (Alexanyan et al. Citation2012). Opposition figures like Alexei Navalny and others have used their social network accounts to expose corruption and other abuses of power by state officials.Footnote5 Additionally, the Internet has proved an important tool for organising and coordinating political protests and other actions in Russia since the December 2011 parliamentary elections (Moen-Larsen Citation2014). Gel'man (Citation2013, 7) also stresses the importance of the Internet as a means of politicisation and involvement of previously uninterested voters in pre-election campaigning: for example, in connection with the 2011 Duma elections, the opposition used video clips, music, and poetry to ridicule United Russia and the regime, and reach potential new voters.

Alexei Navalny has subtitled his LiveJournal blog “The final battle between good and neutrality”. That is a call for action. The battle underway in Russia today is not one between good and evil, but one between good and neutrality. Being neutral cannot, in his view, lead to the necessary changes in Russian society nor bring about the democratic shift that he advocates. Obviously, Navalny uses the blog to mobilise readers to take part in elections, demonstrations, and protests. However, in addition to mobilising social movements, exposing corruption, and conducting election campaigns, his blog outlines the boundaries between “Russian” and “the Other”, thereby constructing an imagined community of “us” and Russian identity. My analysis explores how the discourse of nationalism is part of this identity construction; the remainder of the article focuses on the empirical material found on Alexei Navalny's blog.

This research builds on empirical data from Navalny's blog between the years 2006 and 2012. All blog entries in that period were read and manually sorted, in total 2875 entries of varying length and content. All titles for blog posts, the date, and the URL were saved in separate documents – one document per year – to facilitate re-accessing and re-reading of relevant blog posts. During the process of reading these texts, the blog posts deemed part of a “nationalistic” discourse were coded and saved in a separate file. The selection of relevant blog posts depended on both the actual texts and the researcher's underlying values and perspectives – making the research necessarily a co-production between the researcher and the person researched (Burr Citation2003, 152). This researcher's ideas about nationalistic discourse influence the selection of blog posts for analysis; however, I have applied a broad concept of nation and nationalism, in order to include as much variation as possible.

The criterion used for determining the entries relevant for further analysis was that the entry explicitly mentioned one or several of the following topics: nationalism; Russianness; the people (narod); any ethnic group; any geographical continent or country; any republic in the Russian Federation; or the issue of migration. These categories were chosen because the differing ways in which they are articulated can reveal the boundaries that are being constructed between ethnic groups. The terms Navalny uses to describe different groups, whether positive or negative, serve to position them in relation to his imagined Russian community. When a certain discourse recurs in several blog posts in different years, this indicates continuity in the construction of such ethnic boundaries, as well as showing Navalny's ideas and beliefs in relation to the issue at hand.

The final battle between good and neutrality

This article focuses on mapping the discourse on which Navalny draws – not on uncovering any underlying truths about his personal life. This is important for at least two reasons. First, it can tell us something about his identity as nationalist, a Russian, and politician, as well as indicating the direction his politics could take, should he gain political power. Second, Navalny's blog has many readers who might support his ideas and construct their own identities in similar ways. In an interview with Lenta.ru on 4 November 2011, to which Navalny links in his blog, he claims that people can change, and that their opinions also change. “Different people at different times in their lives say foolish things. I am among those who have said foolish things” (4 November 2011).Footnote6 Indeed, people may sometimes say and do things they regret at a later stage in life, but words, once uttered, serve to feed particular discourses that shape the actions of individuals. It is therefore important to study the words that have been uttered, whether or not the person who said them may have changed his mind since then.

My first research question was: To what extent has Alexei Navalny used his blog on LiveJournal to articulate ideas of nationalism? This can best be answered through careful examination of the blog itself. Navalny's LiveJournal account, navalny.livejournal.com, was created on 19 April 2006. In September 2013, it was rated as most visited by other users, and the most influential and most active on LiveJournal.Footnote7 It has more than 3000 journal entries and has received over two million comments from other LiveJournal users.

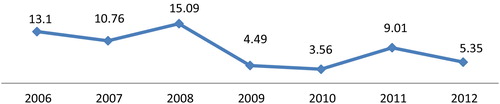

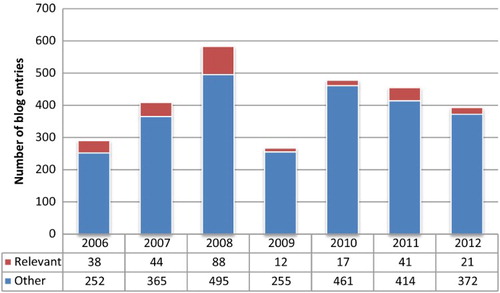

In order to pin down Navalny's ideas about nationalism, and constructions of Russianness, 2875 of his blog entries were sorted using the criteria mentioned above. The end result of the selection process showed that 261 – or 9% – of the total can be seen as part of a larger nationalistic discourse, and as parts of Navalny's construction of imagined communities in present-day Russia. Some posts on the blog are not written by Navalny himself, but are re-posted texts from other sources. However, they are messages that Navalny has wanted his readers to see and are thus as important as are statements he has written himself, so they have been included in the sample. The spread of nationalistic discourse in the period 2006–2012 is shown in percentages () and total numbers ().

shows the percentage of nationalism-related blog entries for every year in the timeframe of the analysis, and shows the total number of blog entries that are part of and not part of Navalny's nationalistic discourse and construction of Russianness. While such discourse is continuously present in the blog throughout the period analysed, the share of nationalism-related blog entries has not exceeded 15.1% in any year. Thus, nationalism is only one of many discourses articulated. Blog entries cover a broad range of topics, public and private: corruption, government, politics, elections, public gatherings, Moscow, Navalny's wife and children, family vacations, music videos on YouTube, Navalny's thoughts on New Year's Eve fireworks, etc.

In addition, and show that the percentage of nationalism-related entries was at its highest in the first three years of the blog, and then declined. Both the actual number (88) and percentage (15) of nationalism-related statements peak in 2008, which can be connected to the five-day war between Georgia and Russia. In the final four years of the period analysed, there is a slight increase in total number (41) and percentage (9) in 2011, which was the year Navalny was on the organising committee of Russian March and participated in the rally “Stop feeding the Caucasus”.

The first research question in this article was raised because of speculations as to the extent of Navalny's nationalism and its implications for future Russian politics. A preliminary answer to this question must be that Navalny has not been using his blog to construct national identity or to disseminate nationalist discourse in any significant extent, although such discourse does appear in the blog. Because the main focus of this study is on nationalistic discourse, the analysis in the following sections deals only with the 261 blog entries that are part of this discourse.

Normal nationalism

I feel tremendous satisfaction in once again seeing that the fight against fascism and nationality-related provocations is carried out by normal Russian nationalists, among whom I account myself. (4 July 2007)

An account of the discourse of Russian nationalism presupposes a discussion of Russianness. Nationalism implies specific ideas about the type of imagined community Russia should be and certain notions about subject positions to be filled by its members. This section takes up the second and third research questions: What is nationalism, according to Navalny – how does he construct “nationalism”? How does Navalny articulate Russian identity (within the context of nationalistic discourse)? Several blog posts draw explicitly on the discourse of Russian nationalism. In the 261 posts analysed for this study, the word “nationalism” is mentioned 38 times; other related words are “nationalist” (48), “nationalistic” (25), “national” (93), “nationality” (11), and “nation” (14).Footnote8 The word-count tells us something about repetition of a particular discourse, which is particularly important when the groups of “Others” are addressed. However, my main analytical focus is on what is being said and not how often it is said.

In the above quote, Navalny positions himself as what he calls a “normal Russian nationalist”. Here we should note that identities are not necessarily static, and one may position oneself differently in different contexts and periods. For instance, even though Navalny explicitly positions himself as nationalist in 2006, in a 2012 blog post he refuses to be labelled at all. Nevertheless, the normalisation of nationalism is continually in evidence in the blog. Meaning is relational: we interpret signs through their difference from other signs (Saussure Citation2006). When something is described as “normal”, that is always in opposition to something that is abnormal. Indeed, throughout his blog Navalny constructs nationalism in opposition to other, “marginal” (his words) ideologies such as extremist nationalism, fascism, and Nazism, which he connects to violence, xenophobia, and pogroms. The blog shows an attempt to construct nationalism as something ordinary, in contrast to these. Further, nationalism is articulated as an expression of love of one's country, rather than hatred towards other nations.

At some point – it is difficult to say when – everyone suddenly decided that the idea of national rebirth of Russians is absolutely equivalent to the idea of Russian national superiority over others. (3 November 2006)

Navalny envisions nationalism as an idea of “rebirth of the Russian people”. In the same blog post, he links this idea of rebirth to the collapse of the Soviet Union (“collapse of an empire”) which has led to millions of “fellow citizens” ending up in a demeaning position outside of Russia. The Russian people are perhaps not superior to other people, but they should not be degraded either. In this way, Navalny imagines the Russian nation as a nation geographically divided but ethnically connected, united by the sense of pride and self-worth. He goes on to say that pseudo-democrats call this an “excessive” love of the country. “To love one's people, one's nation is somehow ugly, suspicious, politically incorrect, and smells slightly like a pogrom” (3 November 2006). In order to negate this “we”, Navalny and his readers (“normal” Russians) must actively position themselves as part of a normal nationalistic movement.

Ultra-radicals have become the leading faces and the driving forces of the national movement in Russia. For some reason we have accepted this. While we are trying to resist this people, we are fighting with the national movement itself, with the idea of the rebirth of the hundred and twenty million people. It is needless to say that this fight will not succeed. What can we do? For me this question is clear. We have to take away the right to proclamation of national ideas from the fascists. We have to deny them their leadership positions in the Russian movement. (3 November 2006)

The blog includes several instances of explicit articulation of national ideas and normalisation of them. Three concrete examples of such normalisation attempts are: the creation of the NAROD movement, the use of the slogan “Glory to Russia”, and Russian March.

In June 2007, Navalny co-established a Russian nationalist coalition named the National Russian Liberation Movement (NAROD) – the acronym NAROD is also the Russian word for “people”. In an interview with New Times, also posted on his blog, Navalny explains that the reasoning behind the creation of the movement was to kick-start the national-democratic discourse (25 April 2011). After the creation of NAROD, Navalny was excluded from the Russian Democratic Party Yabloko “( … ) for causing political damage to the party, in particular, for nationalistic activities”.Footnote9 However, he never expresses regret about participating in the coalition. In one blog-entry he posted the coalition's manifesto in which the Russian imagined community is constructed as “victorious people” and “a great nation”:

Our history proves that the Russian people are capable of mobilising and resisting internal and external treats. The awakening of national consciousness has always been a response to the attempt to enslave our country, to deprive us of our freedom, independence, territory, and to alienate us. A consciousness of the victorious people – able to cope with any disaster and external enemy, to unite and respond to any challenge – has taken root in the minds of our people during a thousand years history. But every generation has to reaffirm the title of “a great people” with their work and achievements. (NAROD manifesto, 25 June 2007)

According to this manifesto, Russia is facing a national catastrophe, because its population is rapidly deteriorating and dying. A radical change of elites is needed: indeed, that would be the most important task of NAROD, the first national-democratic movement in the modern history of Russia. The main values of the movement are national rebirth, freedom, and justice. The movement formulates the main tasks of the Russian state as halting the degradation of Russian civilisation and creating the conditions for the preservation and development of the Russian people, their culture, language, and historical territory. The manifesto also mentions xenophobia and violence against “foreigners” as forces gnawing away at the state and creating a negative image of the nationalists.

The Russian identity is constructed as a “great people”, able to cope with any disaster. Nationalism, it is claimed, can give Russians the self-esteem they have merited through their historical achievements. However, the word “great” also implies a comparison, that one is better than others. Contrary to his claim above, Navalny is in fact imagining Russia as a superior nation. This imagined community of great people is not seen in terms of fear of outsiders. Navalny's nationalism focuses explicitly on the cohesion of the Russian community– not the exclusion of others. His blog shows attempts to confirm the greatness of the Russian people through the slogan “Glory to Russia” (Slava Rossii):

Yesterday, at the democratic rally, I concluded my speech with the slogan “Glory to Russia”. The participants were quite approving, despite dire predictions from a couple of pathetic liberals, who were sure that this would result in a scandal and I would be booed off the stage. (13 June 2006)

For Navalny, “Glory to Russia” is a nationalistic slogan equated with love, pride, and patriotism. He criticises the liberals who compare this slogan to the Nazi salute “Sieg Heil”. In the first two years of his blog, Navalny used the slogan “Glory to Russia” 14 times. In so doing, he took part in the discursive struggle over meaning, seeking to give it a positive and patriotic content while distancing it from Nazism with all such connotations. At the same time, the slogan was used as a criticism of liberals and human rights advocates who, in Navalny's view, were filling the slogan with such negative meaning.

This attempt to normalise “Glory to Russia” appears to have failed. The last time it was used by Navalny himself on his blog was in December 2007, when he posted a speech he held in relation to his exclusion from the Yabloko Party. In March 2011, “Glory to Russia” appeared on the blog one final time in a reposted poem by Vsevolod Emelin, where it was called a “forbidden slogan”. This implies that the struggle over meaning of “Glory to Russia” is still relevant, but that Navalny has now toned down his involvement in this struggle. The use of the slogan also illustrates how Navalny seems to draw a sharp division between Russian nationalism and liberalism. This is particularly interesting in the light of Laruelle's (Citation2014) study of Navalny's attempt to combine these issues; it supports the point where she suggests that Navalny has no clearly formulated ideology and notes that he sometimes articulates conflicting ideas in different contexts.

The final example of normalisation of nationalism on Navalny's blog is related to his interpretation of Russian March. This march is an event organised and conducted in various cities by a range of nationalistic groups, including extremists (Nozhenko Citation2013). According to the event's website: “Brothers and sisters, we are the origin of everything in this country. We will be its end. If there will be no Russians – there will be no Russia” (accessed on 24 September 2013). The Russian March demonstration can be seen as a praxis that confirms the community among Russians. At the same time, however, it constructs boundaries between Russians and non-Russians, and has often been associated with violence against minorities in the country. According to Nozhenko (Citation2013), the demonstration has been used by extremist nationalist groups in order to gain public visibility. Likewise, Zuev (Citation2013) writes that it has developed from protest ritual to an important event organised by the Russian ultra-nationalist movement. As a result of this association with ultra-nationalists, Russian March is often seen as a demonstration of extremists. That is a discourse Alexei Navalny has attempted to oppose in his blog:

“Russian March” for normal people, for whom the realisation that they are Russian, and the pride in that does in principle have no connection and cannot be linked to the desire to insult and humiliate other people. And I will personally do everything possible so that that kind of “Russian March” will take place next year. (3 November 2006)

As noted above, Alexei Navalny took part in the organising committee of Russian March in 2011. In that year, official slogans of the event included: For a free Russian Russia! For rights and freedoms of Russian people! For Russian state! For Russian government! Stop killing Russians! Stop robbing Russia! The future belongs to us! For fair and free elections! (DPNI website, 9 October 2013). Before and after participating in the organising committee, Navalny has actively used his blog to encourage readers to take part in the demonstration. “Russian March” is mentioned 55 times in the blog. As with the slogan “Glory to Russia”, Navalny wishes to construct the March as a normal demonstration, not an extremist one. For Navalny, being a “normal nationalist” and participating in Russian March is a way of showing “concern with real political agenda”, formulated as real problems that people care about. This was also the reasoning behind the NAROD movement:

Do we have problems with illegal migration? Yes we do: Russia is the second country in the world in terms of the number of illegal migrants. Do we have problems with ethnic violence? Yes. The problem with the Caucasus, the problem of Russians who fled from the Caucasus, Caucasian politics – these are real problems that irritate a lot of people, I would say 85% of our population. ( … ) We need to discuss these issues openly and offer solutions, and not push them into some marginal corner. ( … ) This is why I went to and will continue to go to “Russian March”. ( … ) The Nazis are an absolute minority there, but they are the aggressive ones, the photographers love them, and for those reasons they are the most visible ones. Because respectable politicians are unwilling to discuss real problems, they let aggressive marginalities be leading faces of the nationalist movement. However, the overwhelming majority in this environment are completely all right and normal, they are the people from the next office. (25 April 2011, link to an interview with Navalny in the journal New Times)

Thus, Russian March is constructed as an arena where normal nationalists can discuss real challenges such as illegal migrations and problems in the Caucasus. These challenges are also main features in the “Othering” discourse that will be discussed below. The meaning of the demonstration is constructed by its participants. These participants include Nazis and extremists, as well as normal nationalists – and, according to Navalny, the latter are the majority. The subject position of a nationalist is articulated as normal, all right, and employed (“people from the next office”), in contrast to the Nazi, who is aggressive and marginal as well as highly visible. It is the visibility of these marginal representatives of the nationalistic movement that gives the whole movement its negative connotations. However, Navalny maintains, Russian March is a demonstration where normal nationalists discuss the real political agenda.

Navalny constructs nationalism as “normal”, in opposition to “abnormal” nationalism. Normal nationalism represents an idea of national rebirth of Russia, glory and victory, and pride and love for one's country. The Russian identity is constructed as an identity of victorious and a great people. The subject positions available to Russians within the discourse of normal nationalism emphasise this greatness. Furthermore, the Russian identity articulated by Navalny is an ethnic identity, illustrated through the focus on the split between ethnic Russians as a result of the fall of the Soviet Union. This Russian imagined community is united through memories of its glorious past but geographically divided by the fall of the USSR. Furthermore, Russian nationalism should not be associated with hate and xenophobia – “normal nationalists” are not violent fascists, Nazis, or extremists. Thus, the subject position of a nationalist is constructed as a normal individual. This leaves the position potentially open for any reader of the blog: any reader who sees himself as normal can position himself as nationalist. Interestingly, an implicit premise of being “normal” also involves worrying about illegal immigration and the troubles in the Caucasus.

Normal nationalism as constructed by Navalny has similarities with the patriotic discourse briefly described above; these similarities are further emphasised by his attempt to distance his nationalism and nationalists from Nazism and Nazis. However, Navalny's nationalism also includes other elements that are not part of a patriotic discourse and that focus on out-groups rather than in-groups. While claiming that his discourse does not support xenophobia, and that it exclusively concerns the Russian nation and its people, Navalny articulates “migrant-phobic” discourse popular in Russia. This discourse positions some of the citizens of Russia outside Russian imagined community, along with actual foreigners.

The “Others”

Reading Alexei Navalny's blog reveals many groups of people he dislikes, criticises, and often ridicules. There are many types of “Others” that are constitutive for Navalny's identity: they serve as opposites of the type of person he wishes to position himself as being. Among those whom Navalny does not like are liberals, anti-fascists – but also fascists, neo-Nazis, Nazis, Muslims, Islamists, Wahhabis, terrorists, football hooligans, corrupt elites, criminals, illegal migrants, guest workers, and their employers. These are Navalny's “Others”, even though some of them are envisioned as ethnically Russian and therefore positioned as members of the Russian imagined community, whereas others are seen as strangers or outsiders to this community. In his classic article, Georg Simmel (Citation1950, 402) defined a stranger as a “potential wanderer”, someone whose position in the group is determined “( … ) by the fact that he has not belonged to it from the beginning ( … )”. Strangers are people who are somehow seen as out of place, because they might look or act differently from the majority. In the present article, “strangers” are the people occupying the subject positions of “Others” outside the imagined community. By being non-Russian (in the ethnic sense), these “Others” constitute the discourse of Russianness. In the following, I focus on such “strangers” – the groups of “Others” positioned outside the Russian imagined community as constructed on Navalny's blog, and on the subject positions available to them – thereby addressing the final research question of this article.

As noted, Navalny constructs “normal nationalists” as people concerned with illegal immigration and the problems of the Caucasus. On his blog, “illegal immigration” is linked with “violations of the rights of workers”, “Moscow”, “drug trafficking”, “human trafficking”, “crime”, “ethnic violence”, and “ghettoisation”. “Ethnic violence” and “crime” also feature in connection with “the problems of the Caucasus”, in addition to “corruption”, “Ramzan Kadyrov”, and “violation of the rights of Russians in the Caucasus”. The discourses about illegal migration on one side and the Caucasus on the other involve many subject positions that are open for potential “Others”: the position of “illegal migrant” is open for all nationalities and ethnic groups not residing in Russia, while a position of a person “from the Caucasus” is potentially open to members of all ethnic groups residing in both the North and the South Caucasus. In his blog, Navalny links the discourse of illegal migration to particular ethnic groups from Central Asia and the South Caucasus – “strangers” from the Near Abroad, while the problems of the Caucasus are linked to specific ethnic groups from the North Caucasus –“strangers” from within the Russian Federation.

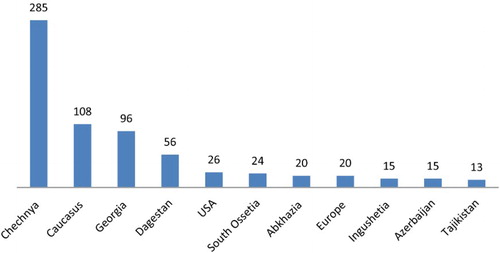

A word-count of geographic areas, nationalities, and ethnicities reveals the national and ethnic constructions that feature the most on Alexei Navalny's blog (see ).

The non-Russian ethnic groups (or nationalities) most frequently mentioned on Navalny's blog are either internal to Russia or from the Near Abroad, except for Europe and the USA.Footnote10 Europe is most frequently mentioned in relation to nationalism in Europe, or when Russia is constructed as a European country – which shows that although Russia might serve as Europe's constitutive other (Neumann Citation1998), Navalny does not construct Europe as Russia's “Other”. The USA is mentioned as part of the discourse about Russia's war with Georgia, as are Georgia, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia. In addition, the USA features in the discourse about war on global Islamisation, ethnic conflicts in the USA, President Obama as an African-American, etc. On the whole, the USA is not articulated in ways constitutive of Russianness and is therefore not used by Navalny to mark the borders of the Russian imagined community, whereas Europe is seen as the larger geographic context of this imagined community. Unsurprisingly, neither Europe nor the USA appears as part of the discourses about illegal immigration to Russia or the problems of the North Caucasus. However, the USA is mentioned as struggling with its own illegal migration, when Navalny claims that “[t]here is a specific agenda that worries people. This agenda is the large number of illegal migrants. It is a fact that Russia is second after USA based on this indicator” (4 November 2011, link to an interview with Navalny on lenta.ru).

The term “illegal migration” appears 12 times on the blog, while the words “migrant” and “migration” occur 73 times. Navalny does not distinguish clearly between illegal migration and migration in general: they are seen as the same phenomenon. As noted above, the fight against migrants (and “illegal migrants” in particular) has been used for popular appeal in Russian political field.

A vast majority in all segments of society believe that “migrants” – rather than “migration” – are the problem ( … ) As a result, migrant-phobia ( … ) enjoys widespread support throughout Russian society, including among bureaucrats, the law enforcement authorities, and in the mass media. (Verkhovsky Citation2009, 95)

This is the discourse Navalny draws on in articulating the subject position of “the migrant”. For him, illegal migrants and legal migrants are equally “foreign”, and they are all positioned as “strangers”. The two countries most frequently connected to immigration on the blog were both elements in the former Soviet Union – Azerbaijan and Tajikistan – and the subject position of the migrant is most often articulated as Tajik or Azeri.

Insolent Azerbaijani crooks, thieves and bandits who for some unknown reason have dragged themselves to Krasnoyarsk, where they are shooting at each other, stealing and robbing, disturbing the peace for normal citizens. Hope they go back home to Azerbaijan as soon as possible. (27 April 2009)

This quote shows how the subject position of the Azeri is articulated in relation to crime and public disorder. The blog also connects the Azeri with rape, as well as sports and public fights. In contrast to the Azeri, who is accorded at least some agency and control, the picture of the Tajik presents a victim of the circumstance, the guest worker who in the end has no choice but to commit crimes:

I am by no means a socialist, as some people claim in the comments [to my blog posts], nevertheless I insist on that it is absolutely not possible that hundreds of thousands of people are being taken to my country, who will not have any social guarantees. And it is not because I feel bad for the Tajiks, but because, when he [the Tajik] is thrown on the street without pay, he will rob my wife in order to buy a ticket home. (13 March 2008)

The Tajik is a migrant and also a guest worker, which connects him to the discourse of human trafficking and violation of workers' rights. This discourse also constructs other enemies – human traffickers and Russian “slave owners”:

Here, my friends are occupiers and enemies. ( … ) The Tajik is not the occupier. The Tajik is not guilty in anything. In Dushanbe he was recruited by the human trafficker Zafar, and in Moscow he was bought by the slave owner Temnikov. This is why the Tajik needs to be paid and deported. (11 March 2008)

Some far-right groups have employed the discourse about capitalists who find cheap labour abroad, resulting in lower wages and rising unemployment among Russians. These groups realise that people of other nationalities are not the real enemy (Wogner Citation2012, 274). The same discourse is reproduced by Navalny when he claims the Tajik bares no blame in the “occupation” of Russia. By contrast, the Russian “slave owner” should stay in Russia and be punished, because he belongs to the Russian imagined community. The quotes above say that both the Tajik and the Azeri – as strangers and migrants – should go back to the countries where they belong.

The discourse of “illegal immigration” is one of two main “Othering” themes in Navalny's national identity construction. It is the second discourse, “the problems of the Caucasus”, that is repeated more frequently. And the “stranger” most recurrent in the blog is Chechen (see ).

It might not come as a surprise that Chechnya represents Navalny's main “Other”, given the recent Russian history of the two Chechen Wars (see e.g. Cherkasov and Grushkin Citation2005; Dunlop Citation1998; Evangelista Citation2002; Gammer Citation2006). Other studies have noted how the Chechen symbolises idea of the enemy and the terrorist to many Russians (Russell Citation2005; Wilhelmsen Citation2014). Furthermore, Verkhovsky connects Russian “migrant-phobia” with the Chechen wars and the Islamophobia caused by terrorist attacks: “There are virtually no other issues that can compete effectively with ethno-religious xenophobia for public attention” (Citation2009, 98).

My findings show that this discourse is still relevant and is being reproduced by Navalny on his blog. In the blog, the subject position of Chechen is articulated as male, Muslim, murderer, terrorist, and criminal. The discourses which include a Chechen subject position concern issues such as the Chechen war, corruption, ethnic feuds, and Islamic terrorism. Navalny quotes an interview in Kommersant-vlast where terrorism is referred to as a lifestyle for Chechens – and therefore worse than Russian terrorism, which can be seen as episodic and more spontaneous (26 April 2006). Although the Chechen is envisioned as the terrorist, Navalny also notes the existence of a liberal discourse about the relationship between Russians and Chechens in which the Chechen is positioned as a victim. “You cannot touch Chechens. It is the axiom of our liberal policy: Russians are bad, Chechens are good. And there is nothing to be done. It's like spitting into the wind” (9 January 2008). Navalny contests this discourse by positioning the Russian as the victim, by repeatedly pointing out that Russians were forced out of Grozny in 1990, and he writes about “ethnic cleansing of Russians in Caucasus” (27 September 2007). The positioning of the Chechen as villain versus victim further illustrates how Navalny articulates the nationalist and liberal discourses as opposed to each other.

Navalny constructs the Chechen as different from the Russian in many ways. The Chechen is traditional and pre-modern; moreover, he does not abide by Russian laws, but by the laws of the mountains. Thus, the Chechen is envisioned as the ultimate stranger, and the question of whether Chechnya should be part of Russian Federation is raised. Considerable funding from the Russian state budget has been going to that republic, and criticisms of this public spending have produced the discourse “Stop feeding the Caucasus”. Although [North] Caucasus is the second most-mentioned area in the blog, it is mentioned three times less than Chechnya – which makes clear the leading position of the Chechen as “the Other” on Navalny's blog. Chechnya is of course part of the Caucasus, and is often implied when the area is mentioned: “Stop feeding the Caucasus” also connotes “Stop feeding Chechnya”. On the other hand, many other ethnic groups live in the North Caucasus, and the discourses about that particular area shape the perceptions about these groups. Navalny's use of “North Caucasus” to label the whole area and the people living there erases internal differences, making people from the North Caucasus seem like one coherent group – and all of them strangers. shows that Navalny also mentions two other republics in the North Caucasus, Ingushetia, and Dagestan. The remaining republics remain implicit, but perceptions of them are coloured by the overall discourse of the problems of the Caucasus.

Everything that is happening in Chechnya, Ingushetia, in the North Caucasus in general and what people from this region are doing in Moscow makes us again think about the question: Do we want to, and are we able to live together with these people in one state, in one city, in one society? ( … ) Blood feud as a phenomenon gets a certain romantic aura [in Russian mass media]. ( … ) For me blood feud is a phenomenon of the same order as sex with sheep. It is as romantic. It is also an ancient custom. And it should be respected to the same extent. ( … ) If this is my country, I do not want it to have regions where blood feuds are common and socially accepted phenomena. ( … ) Where are the notorious elders, whose opinions are supposedly heeded in the Caucasus? Are they really able to influence anything? Let them influence. Or are they, as I assume, just senile grandfathers, who like to dance in a circle and wave with wooden sticks. ( … )? We cannot coexist normally with people who declare that they want to live like animals. (26 September 2008)

This quote shows how the North Caucasus and the people living there are constructed as foreign to Russia. The blood feud is presented as a traditional practice which is common in the North Caucasus and has now been transferred to Moscow. By taking part in blood feuds, the people of the North Caucasus are positioned as animals – the ultimate “Others”. Interestingly, although Ingushetia and Chechnya are mentioned explicitly, the quote constructs the whole of the North Caucasus as a pre-modern society that practises ancient tabooed traditions. These are traditions that do not belong in Russia: ergo, the whole area does not belong in Russia. In addition, the quote deprives the councils of elders in the Caucasus of their legitimacy by representing them as senile grandfathers, which is another way of constructing the area as pre-modern and thus incompatible with the rest of Russia. By constructing the entire North Caucasus as pre-modern, Navalny constructs Russia as “modern” and Russian identity as “civilised”.

This analysis of Navalny's blog on LiveJournal reveals two main images of “the Other”: a person from the North Caucasus, most often Chechen; and a migrant from the Near Abroad, most often from Azerbaijan or Tajikistan. What unites these images is that their otherness is constructed in connection to Islam, which the blog sees as a foreign influence in Moscow, somewhat backward and linked to terrorism. Their otherness is also expressed as their inability to obey Russian laws, and by their discriminating against Russians, whether by violating the rights of Russians in their countries and republics or by attacking Russians elsewhere in Russia. Navalny's blog offers many other examples to show why these strangers do not belong in Russia. Often the main distinction between the groups of “Others” – the fact that people from the North Caucasus hold Russian citizenship and illegal migrants do not – is erased, and both groups are presented as equally foreign. In this way, the “migrant-phobic” discourse positions people with Russian citizenship and a long history with Russia outside the Russian imagined community. The conclusion seems to be that these strangers should either assimilate or leave. “Sensible immigration policy is a state priority. Those who come to our house and are not willing to respect our laws and traditions should be evicted” (NAROD manifesto, 25 June 2007).

Conclusions

Alexei Navalny's discourse is important in its own right because it has an appeal in Russian society, to opposition groups in particular. The fact that access to his LiveJournal blog was blocked by RuNet service providers in March 2014 (“Access Blocked to Major Opposition Sites”, Citation2014) indicates that the regime sees his influence as threatening. It is therefore important to investigate the content of Navalny's discourse both because it indicative of the mood of his followers and because it may have implications for the direction Russian politics will take, should he come to power. This article has analysed Navalny's discourse on his LiveJournal blog through a focus on nationalism, the Russian imagined community, and groups of “Others” who belong outside this community.

In analysing Navalny's nationalism, Laruelle (Citation2014) finds that Navalny reproduces many of clichés already used in the public space, rather than developing new ideas to recast the Russian nationalist debates. Navalny participates in the Kremlin-backed consensus on the problems created by migrants from North Caucasus and Central Asia (Laruelle Citation2014, 5). The findings in this article support Laruelle's argument, while contributing with a deeper focus on the content of the discourse on Navalny's blog as well as on the extent of the discourse's presence in the blog.

Although nationalistic discourse features in only 9% of all blog entries, it has been present throughout the whole period analysed (2006–2012) and was thus part of Navalny's discourse long before he became a popular political figure. Navalny constructs proper nationalism as something normal and ordinary, in opposition to abnormal, radical, and marginal nationalism. His discourse seeks to “reclaim” nationalism from the “extremists”. Furthermore, discourse analysis shows that Navalny draws on elements of “patriotic discourse” which he recasts as “normal nationalism”, and that he combines this discourse with an ethnic focus and “migrant-phobic” elements. On the one hand, the Russian imagined community is seen as a community of people united by a glorious past and the Second World War victory over the Nazis; on the other hand, this imagined community consists of people who share a common ethnicity and culture. The Russian identity that Navalny constructs on his blog is not multi-ethnic, but bounded – russkiy, not rossiyskiy. Other ethnic groups, Chechens in particular, are constructed as strangers who belong outside these boundaries. Navalny's normal nationalism is predominantly ethnic, not civic.

It is hardly surprising to find that Navalny has been articulating a discourse already present in Russian political field, because discourses do not exist in a cultural and historical vacuum: they travel among societies, groups, and individuals. Discourse analysis is an important part of political analysis because discourse legitimises and reflects specific political practices and political views. One specific policy implication of the discourse found on Navalny's blog, should he come to power, would probably be stricter visa regulations for people from former Soviet republics in the South Caucasus and in Central Asia. This would of course be a challenge within the Eurasian Economic Union that Russia has been attempting to build. Other implications might be stricter policies in the North Caucasus, but here Navalny offers no clear ideas on how to overcome the cultural barrier, which he presents as being incompatible with Russian culture and traditions.

Although some Russian politicians have emphasised the boundaries between “Russians” and “Others” as the ones that are present in Navalny's blog, Vladimir Putin (Citation2013) himself has stressed the importance of constructing a common Russian identity on the basis of multiculturalism and multi-ethnicity. However, the Kremlin's recent focus on ethnic Russians in the discourse about Crimea and Ukraine indicates a change in Russian discourse and politics that gives priority to ethnicity rather than citizenship. Further development of this discourse is important because it may have unforeseen consequences for Russian society, with multiple ethnic groups residing in Russia being alienated in a process where protection of ethnic Russians becomes a state priority.

Alexei Navalny's discourse is part of a larger political discursive context. Nationalistic discourse evolves between the Kremlin, opposition groups, and the population in general. It is important for scholars to trace the development of this discourse – especially in the light of recent events in Ukraine – because how Russian politicians talk about Russia and Russianness is indicative of the shape of Russia's future domestic and foreign policies.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful for valuable comments by Sean Roberts.

Funding

This article is a product of the NUPI research project, “Modernizing the Russian North: Politics and Practice”, funded by the Research Council of Norway.

Notes on contributor

Natalia Moen-Larsen (M.A. University of Oslo, Sociology) is a Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Her areas of research interest include social media and governance in Russia, opposition politics and nationalism, migration and multicultural identities. She is co-editor of the Scandinavian language journal Nordisk Østforum and currently working on a project facilitating contact and dialogue amongst students and scholars from North Caucasus and from Moscow.

Notes

1. This article uses the common anglicised version “Alexei Navalny”, and not “Aleksei Navalnyi”.

2. Russian March is an annual nationalist demonstration held on People's Unity Day, 4 November, since 2005. Official website: http://rmarsh.info/. The expression “people's unity” can be interpreted as something open and inclusive, but the March is often associated with violence against non-Russians. Navalny's participation in the March is further discussed in the analysis part in this article.

3. “Stop feeding the Caucasus” was a rally criticising budget politics in the North Caucasus, held on 22 October 2011. The title of the rally has become a famous slogan, criticised by Vladimir Putin in his article “Russia: The Nationalist Question” (Citation2012).

4. The examples given here are by no means exhaustive, but space constraints prevent a broader discussion of the many ways of studying nationalism. The examples have been selected as being particularly relevant to the analysis in this article.

5. See, for example, rospil.info, a website created for monitoring state spending. Here individuals can upload information about questionable purchases carried out by state and government officials. In response to rospil.info, the government created its own website where registered users can discuss all government purchases: http://zakupki.gov.ru.

6. All quotes from the blog are given with date; and all empirical material is available in Russian at navalny.livejournal.com. Translations from Russian are by the author.

7. All figures were checked on 11 September 2013, only five days after the Moscow mayoral election, where Navalny came in second. It seems highly probable that his recent political activity influenced the popularity and the ratings of his blog.

8. The word-count covers only texts posted on the blog, not articles on nationalism where links are given. If such links were included, the count would be much higher.

9. For this quote and more information on Navalny's participation in the Yabloko Party, see http://lenta.ru/lib/14159595/#93, accessed on 19 September 2013.

10. The word-count includes geographical areas, capital cities and ethnic groups. For example, Chechnya (285) means the number of times “Chechnya”, “Chechen” and/or “Grozny” were mentioned in the blog.

References

- “Access Blocked to Major Opposition Sites and Navalny's Blog.” 2014. Moscow Times, March 14. Accessed April 10, 2014. http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/access-blocked-to-major-opposition-sites-and-navalnys-blog/496148.html

- Alexanyan, Karina, Vladimir Barash, Bruce Etling, Robert Faris, Urs Gasser, John Kelly, John G. Palfrey Jr., and Hal Roberts. 2012. “Exploring Russian Cyberspace: Digitally-Mediated Collective Action and the Networked Public Space.” Berkman Center Research Publication 2012–2. Accessed October 10, 2013. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2014998&http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/publications/2012/exploring_russian_cyberspace

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

- Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Bauman, Zygmunt, and Tim May. 2001. Thinking Sociologically. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Blum, Douglas W. 2006. Official Patriotism in Russia: Its Essence and Implications. PONARS Policy Memo No. 420. Accessed April 10, 2014. https://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/pm_0420.pdf

- Bode, Nicole, and Andrey Makarychev. 2013. “The New Social Media in Russia: Political Blogging by the Government and the Opposition.” Problems of Post-Communism 60 (2): 53–62. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600205

- Burr, Vivien. 2003. Social Constructionism. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Cherkasov, Alexander, and Dmitry Grushkin. 2005. “The Chechen Wars and the Struggle for Human Rights.” In Chechnya: From Past to Future, edited by Richard Sakwa, 131–157. London: Anthem Press.

- Davies, Bronwyn, and Rom Harré. 2007. “Positioning: The Discursive Production of Selves.” In Discourse Theory and Practice: A Reader, edited by Margaret Wetherell, Stephanie Taylor, and Simon J. Yates, 261–271. London: Sage.

- Dunlop, John B. 1998. Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Evangelista, Matthew. 2002. The Chechen Wars: Will Russia Go the Way of the Soviet Union? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communication. 2010. “Internet v Rossii: Sostoyanie, Tendencii i Perspektivi Razvitiya.” Accessed October 10, 2013. http://www.fapmc.ru/magnoliaPublic/dms-static/7180131a-52db-4002-9408-e2403280a861.pdf

- Foucault, Michel. 2000. “The Subject and Power.” In Power. Vol. 3 of Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984, edited by James D. Faubion, 326–348. New York: The New Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 2008. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Gammer, Moshe. 2006. The Lone Wolf and the Bear: Three Centuries of Chechen Defiance of Russian Rule. London: Hurst.

- Gel'man, Vladimir. 2013. “Cracks in the Wall: Challenges to Electoral Authoritarianism in Russia.” Problems of Post-Communism 60 (2): 3–10. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216600201

- Greenfeld, Liah. 1992. Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Herrera, Yoshiko, and Nicole M. Butkovich Kraus. 2013. “National Identity and Xenophobia in Russia: Opportunities for Regional Analysis.” In Russia's Regions and Comparative Subnational Politics, edited by William M. Reisinger, 102–119. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jaskułowski, Krzysztof. 2010. “Western (Civic) Versus Eastern (Ethnic) Nationalism: The Origins and Critique of the Dichotomy.” Polish Sociological Review 3 (171): 289–303.

- Jørgensen, Marianne, and Louise Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage.

- Kasparov, Garry. 2012. “Alexei Navalny: Watchdog.” Time 100, April 18. Accessed October 10, 2013. http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2111975_2111976_2112167,00.html

- Kohn, Hans. 1944. The Idea of Nationalism. A Study in Its Origins and Background. New York: Macmillan.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2001. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. 2nd ed. London: Verso.

- Laruelle, Marlène. 2009a. “Introduction.” In Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia, edited by Marlène Laruelle, 1–10. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Laruelle, Marlène. 2009b. “Rethinking Russian Nationalism: Historical Continuity, Political Diversity, and Doctrinal Fragmentation.” In Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia, edited by Marlène Laruelle, 13–48. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Laruelle, Marlène. 2014. “Alexei Navalny and Challenges in Reconciling ‘Nationalism’ and ‘Liberalism’.” Post-Soviet Affairs 1–22. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2013.872453

- Moen-Larsen, Natalia. 2014. “‘Dear Mr President’. The Blogosphere as Arena for Communication Between People and Power.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 47: 27–37. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2014.01.007

- Neumann, Iver B. 1998. “Russia as Europe's Other.” Journal of Area Studies 6 (12): 26–73. doi:10.1080/02613539808455822

- Neumann, Iver B. 1999. Uses of the Other: ‘The East’ in European Identity Formation. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Neumann, Iver B. 2001. Mening, materialitet, makt: en innføring i diskursanalyse. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Nozhenko, Maria. 2013. Right-Wing Nationalism in Russia: A By-product of Electoral Competition or a Political Agenda for the Future? FIIA Briefing Paper 135. Accessed October 9, 2013. http://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/353/#.UlV6z396J6M

- Oates, Sarah. 2012. “Political Challengers or Political Outcasts?: Comparing Online Communication for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and the British Liberal Democrats.” Europe-Asia Studies 64 (8): 1460–1485. doi:10.1080/09668136.2012.712277

- Orttung, Robert W. 2013. “Navalny's Campaign to Be Moscow Mayor.” Russian Analytical Digest (136). Accessed October 10, 2013. http://www.css.ethz.ch/publications/pdfs/RAD-136.pdf

- Popescu, Nicu. 2012. “The Strange Alliance of Democrats and Nationalists.” Journal of Democracy 23 (3): 46–54. doi:10.1353/jod.2012.0046

- Putin, Vladimir. 2012. “Russia: The Nationalist Question.” Nezavisimaia Gazeta, January 23. Accessed September 23, 2013. www.ng.ru/politics/2012-01-23/1_national.html

- Putin, Vladimir. 2013. “Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club.” Kremlin.ru, September 19. Accessed October 16, 2013. http://eng.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6007

- Renz, Bettina, and Jonathan Sullivan. 2013. “Making a Connection in the Provinces? Russia's Tweeting Governors.” East European Politics 29 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1080/21599165.2013.779258

- Russell, John. 2005. “Terrorists, Bandits, Spooks and Thieves: Russian Demonisation of the Chechens Prior to and Since 9/11.” Third World Quarterly 26 (1): 101–116. doi:10.1080/0143659042000322937

- Saussure, Ferdinand de. 2006. Writings in General Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, Henke. 2012. “The Triple P of RuNet Politics: Protest, Political Technology, Public Sphere.” Euxeinos 4: 5–25. Accessed October 9, 2012. http://www.gce.unisg.ch/~/media/Internet/Content/Dateien/InstituteUndCenters/GCE/Euxeinos%20Folder/Euxeinos%204_2012%20update.ashx?fl=de

- Shulman, Stephen. 2002. “Challenging the Civic/Ethnic and West/East Dichotomies in the Study of Nationalism.” Comparative Political Studies 35 (5): 554–585. doi:10.1177/0010414002035005003

- Simmel, Georg. 1950. “The Stranger.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, translated and edited by Kurt H. Wolff, 402–440. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Sperling, Valerie. 2009. “Making the Public Patriotic: Militarism and Anti-militarism in Russia.” In Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia, edited by Marlène Laruelle, 218–271. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Toepfl, Florian. 2012. “Blogging for the Sake of the President: The Online Diaries of Russian Governors.” Europe-Asia Studies 64 (8): 1435–1459. doi:10.1080/09668136.2012.712261

- Umland, Andreas. 2009. “Concepts of Fascism in Contemporary Russia and the West.” In Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia, edited by Marlène Laruelle, 75–86. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Verkhovsky, Alexander. 2009. “Future Prospects of Contemporary Russian Nationalism.” In Russian Nationalism and the National Reassertion of Russia, edited by Marlène Laruelle, 89–103. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Volkogonova, O. D., and I. V. Tamorenko. 2001. “Etnicheskaya identifikatsiya russkikh ili iskushenie natsionalizmom.” Mir Rossii 10 (2): 149–165.

- Vujacic, Veljko. 2007. “Stalinism and Russian Nationalism: A Reconceptualization.” Post-Soviet Affairs 23 (2): 156–183. doi:10.2747/1060-586X.23.2.156

- Waller, Julian G. 2013. “Re-setting the Game: The Logic and Practice of Official Support for Alexei Navalny's Mayoral Run.” Russian Analytical Digest (136). Accessed October 10, 2013. http://www.css.ethz.ch/publications/pdfs/RAD-136.pdf

- Wilhelmsen, Julie. 2014. “How War Becomes Acceptable: Russian Rephrasing of Chechnya.” PhD diss., Department of Political Science, University of Oslo.

- Wogner, Peter. 2012. “A Mad Crowd: Skinhead Youth and the Rise of Nationalism in Post-Communist Russia.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 45: 269–278. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2012.07.015

- Yagodin, Dmitry. 2012. “Blog Medvedev: Aiming for Public Consent.” Europe-Asia Studies 64 (8): 1415–1434. doi:10.1080/09668136.2012.712269

- Zuev, Denis. 2013. “The Russian March: Investigating the Symbolic Dimension of Political Performance in Modern Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (1): 102–126. doi:10.1080/09668136.2012.738800