ABSTRACT

As the number of European countries that recognise same-sex unions increases, so does the number of countries that resists this institution. This trend runs counter to the conventional wisdom, which links anti-LGBTI policies to domestic demands and developments. Instead, this paper argues that political homophobia needs to be situated within an international context. Using the Slovak case as a plausibility probe, the article shows that the bans on same-sex marriage were adopted as a precautionary measure: worried by the growing support for LGBTI rights elsewhere in Europe, conservative lawmakers feared that their traditional family values would come under threat.

In 2014, the Slovak parliament made it constitutionally impossible for homosexual couples to tie the knot. Lawmakers in Bratislava thereby bucked an apparent trend of growing legal recognition of same-sex unions, at least in advanced democracies (Kollman Citation2007).

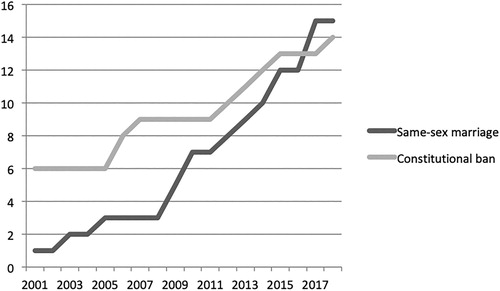

Yet, as and display, convergence around same-sex unions coincides with divergence. The number of constitutional bans on same-sex marriage is rising alongside the number of countries that have granted same-sex couples the right to marry.Footnote1 Six European states already had such a ban in place before the Netherlands first introduced same-sex marriage in 2001. Eight others have since defined marriage as a union between a man and a woman in their constitution. Romania almost became the latest country to jump onto the traditionalist bandwagon in October 2018, but low turnout prevented a referendum on the constitutional definition of the family from taking effect. Evidently, greater support for the legal recognition of same-sex relationships in some European countries concurs with increasing political resistance elsewhere on the continent.

Figure 1. Number of European countries that recognise and constitutionally ban same-sex marriage (2001–2018).

Table 1. European countries that recognise and constitutionally ban same-sex marriage.

What explains these constitutional protections of the traditional understanding of marriage? The dominant theoretical accounts would expect such moves in the realm of morality policy – or conflicts over first principles (Engeli, Green-Pedersen, and Larsen Citation2012) – to be a response to internal demands and developments. Morality policy may reflect the wishes of the public (Haider-Markel and Kaufman Citation2006; Hildebrandt, Trüdinger, and Jäckle Citation2017), of religious actors that enjoy privileged access to the corridors of power (Grzymała-Busse Citation2015; Schmitt, Euchner, and Preidel Citation2013), or of powerful advocacy coalitions. Constitutional bans could also signify a backlash to gains made by LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) advocates in other areas, especially following court rulings (Klarman Citation2013) and the increased visibility of the LGBTI movement (Fetner Citation2008; Guasti and Bastikova Citation2019; Stone Citation2012). Internal considerations, in short, informed the decision to outlaw same-sex marriages.

However, as the next section shows, the factors most prevalent in the extant literature cannot explain the timing of the constitutional revisions that have taken place in recent years: the public is generally becoming more supportive of same-sex unions; religious actors and conservative advocacy coalitions did not see their influence grow markedly over time; the few victories achieved by sexual minorities played, at best, a marginal role in debates on the definition of marriage; and the LGBTI movements remained too weak, and too disconnected from the political arena, to inspire counter-mobilization.

Counter to the dominant focus on domestic factors, I argue that the protective measures should be situated within their international context. The proposals to revise the constitution were motivated by outside developments. Recognising the wave of same-sex unions that was washing over Europe, and fearing the increased meddling of supranational organisations in matters of morality, conservative lawmakers responded by sheltering the traditional family from foreign influence. This argument builds on recent work by scholars of social movements, which describes the clampdown on LGBTI rights as the accomplishment of an “anticipatory countermovement” (Dorf and Tarrow Citation2014; Weiss Citation2013) and a “politics of pre-emption” (Currier and Cruz Citation2017). It also ties in with scholarship on the transnational dimension of anti-gender initiatives (e.g. Anić Citation2015; Corredor Citation2019; Kuhar and Paternotte Citation2017). Transnational activism can inspire or sustain domestic lawmakers’ calls for policy change. American organisations of the Christian Right, for instance, assisted in the campaign for the Romanian referendum on marriage (Ciobanu Citation2017). Slovakia’s Christian Democratic Movement is also firmly embedded within the transnational network of moral traditionalism (e.g. In ‘t Veld Citation2019). Similarly, “pro-family” transnational groups and lawmakers alike have taken aim at the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence for its description of gender as a socially constructed phenomenon (Roggeband and Krizsán Citation2018). Expecting the pressure on their countries to recognise same-sex unions to soon mount, political representatives in several European states took precautionary measures. An increase in constitutional bans on same-sex marriage was the result.

The Slovak case serves as a plausibility probe. I show that the constitutional change there originated with conservative politicians within the Christian Democratic Movement. They framed this measure as a precaution meant to protect the Slovak nation against imminent pressure from abroad, in particular from the European Union (EU). While they finally succeeded in revising the constitution in 2014, the lawmakers’ defensive campaign lasted over a decade and even predated Slovakia’s EU membership.

The article proceeds as follows. The first section outlines the literature’s leading explanations of anti-LGBTI policies, the common shortcoming of which, as the subsequent section shows, is their inward focus. I then present the argument that constitutional bans on same-sex marriage are the work of an internationally oriented, anticipatory countermovement. After a brief methodological discussion, I analyse the Slovak case. The conclusion summarises the argument and its relevance for other cases.

Explaining resistance to LGBTI rights: domestic demands and developments

The study of LGBTI rights has blossomed in recent years. Much of this nascent scholarship is interested in explaining the new rights that sexual minorities have won across the globe (Ayoub Citation2016) and the growing public acceptance of erstwhile sexual deviants (Adamczyk Citation2017). Comparatively little attention has been paid to the adoption of policies that, instead of protecting sexual minorities, target them.

Nevertheless, some scholars have begun to study the political elite’s resistance to gay rights (Bosia and Weiss Citation2013; Guasti and Bastikova Citation2019; Holzhacker Citation2013). In order to explain this “state-sponsored” or political homophobia, especially in the American context, scholars pointed to two sets of domestic factors: a country’s innate demand for anti-gay politics and critical developments that provoked a backlash.

The first category treats morality policy as a function of domestic demand. The influence of public opinion “is thought to be especially strong on morality policy” (Norrander and Wilcox Citation1999, 708). Societal values, in this story, can put a country “at risk” of targeting sexual minorities. If lawmakers listen to the public, then homophobic laws should be most expected in countries that strongly disapprove of homosexuality. Indeed, American states’ decisions to ban same-sex marriage “align well with mass opinion” (Lewis and Oh Citation2008, 51). Hildebrandt, Trüdinger, and Jäckle (Citation2017) demonstrate the effect of public opinion on LGBTI-related policies in the European context.

The adoption of anti-LGBTI policies can also be connected to more concrete petitioners. Religious actors are a prominent example. Grzymała-Busse (Citation2015, 8) finds that “the most influential churches do not rely on pressure at the ballot box or on partisan coalitions”, but instead on direct institutional access. Such access, in turn, is a function of a church’s moral authority, or identification of that church with the national interest. For example, whether family law discriminates against women appears to be related to the institutionalisation of religious authority (Htun and Weldon Citation2015). Scholars have documented religious involvement with LGBTI-related in places as far apart as Iran (Korycki and Nasirzadeh Citation2013), Romania (Turcescu and Stan Citation2005) and Zambia (Van Klinken Citation2013). It is conceivable that national churches drove the demand for constitutional bans on same-sex marriage.

Relatedly, scholars of morality policy have emphasised the role of religiously oriented political parties. Engeli, Green-Pedersen, and Larsen (Citation2012) discern two distinct realms of conflict definition: the “religious” and the “secular world”. The religious world is characterised by a split between confessional and secular parties. The latter are said to have an incentive to call attention to morality issues, because this forces Christian-Democratic parties to “reaffirm a set of potentially divisive Christian moral values” (Engeli, Green-Pedersen, and Larsen Citation2012, 15). In secularising times, such reaffirmations undercut the Christian Democrats’ catch-all appeal. Euchner (Citation2019) shows how secular parties, as part of the opposition, politicise morality issues in order to drive a wedge between coalition governments that include a confessional party. There are no parties in the secular world. Parties consequently lack “a strong interest in politicizing morality issues” (Engeli, Green-Pedersen, and Larsen Citation2012, 16). Such issues are instead discussed on a non-partisan basis. Because this literature’s objective is to explain the “road to permissiveness” (Knill et al. Citation2015), it is unclear how its theoretical logic would apply to decisions to regulate morality issues more strictly within the “religious world”.Footnote2 One possibility is that secular parties’ proposals to liberalise moral regulation backfire by forcing Christian-Democratic parties to own up to their religious values. The argument could then be linked to the backlash thesis discussed below.

The constitutional revisions may also reflect the demands from conservative civil-society actors. In the United States, the Religious Right began to use ballot measures to restrict the rights of LGBTI people in the 1970s (Stone Citation2012). State-level family policy councils have also actively pursued same-sex marriage bans (Soule Citation2004). Traditionalist groups have increasingly launched “anti-gender campaigns” in Europe (Kuhar and Paternotte Citation2017). Some campaigns are homegrown; in other cases, foreign actors cultivated a domestic demand to protect traditional family values. American evangelicals, for example, fanned the flames of homophobia in Uganda, culminating in that country’s adoption of the Anti-Homosexuality Act (Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Citation2017). This explanation would trace the constitutional bans back to the influence that “pro-family” or anti-LGBTI interest groups or social movements wield over policymakers.

Whereas the previous factors concentrate on the agents of change, a second type of explanation is more concerned with the timing of such change. It expects restrictions of human rights in one area to come on the heels of advancements in another area.

Arguably the clearest expression of this argument, Michael Klarman’s “backlash thesis” notes that progressive court rulings on same-sex unions in the US provoked retaliatory actions from policymakers and voters. Many legislators who had voted for such unions lost their bids for re-election, while the number of states with constitutional bans on same-sex marriage spiked. Moreover, as the continual non-adoption of the Employment Nondiscrimination Act illustrates, “gay marriage litigation may have delayed realization of other items on the gay rights agenda” (Klarman Citation2013, 213). Legislative victories thus proved pyrrhic.

Furthermore, the successes of lesbian and gay activists sparked the emergence of a strong opposing movement intent on shoring up the traditional family (Fetner Citation2008). This resulted, inter alia, in a series of ballot measures that set the clock back on LGBTI rights (Stone Citation2012). From this perspective of movement-countermovement dynamics, liberalisation created a demand for conservative counteractions (Meyer and Staggenborg Citation1996; Stone Citation2016). Guasti and Bustikova (Citation2019), in a recent study, demonstrated this ‘reactive logic of backlash against accommodation’ in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

This countermovement need not have emerged in response to LGBTI people’s actual policy gains. It may also arise in response to growing demands for sexual minority rights. The countermovement may attempt to nip a worrying trend in the bud. The constitution is an especially lucrative site for enshrining a ban on same-sex marriage because, unlike civil or family codes, it can often only be amended with the support of a supermajority and after multiple readings. Because it is so hard to overturn, a constitutional ban could frustrate the ever-louder calls for more rights.

All aforementioned explanations have observable implications. If constitutional bans reflect public opinion, then their adoption should follow a societal surge in homophobia. If lawmakers instead heeded the concerns of religious or civil-society actors, then we should be able to find evidence of a concerted campaign for constitutional change. Finally, if this change constitutes a countermeasure, there should be proof of one of two things: either conservative actors experienced policy setbacks related to marriage and the family or, alternatively, LGBTI rights activists and their political allies are clearly articulating a demand for same-sex unions. Is the empirical evidence consistent with these implications?

Assessing the evidence: the insufficiency of an inward perspective

The short answer is an unequivocal no. The preliminary evidence suggests that there was no sudden domestic demand for such moral protectionism in the European countries that have constitutionally prohibited same-sex marriage. Nor can the bans be explained away as a backlash to internal developments. The explanation has to be found elsewhere.

The analysis in this section is, for reasons of feasibility, limited to the subset of eight countries that adopted a constitutional ban in 2006 or after. It draws on three main sources: cross-national surveys, news articles, and the secondary literature on LGBTI rights. These sources do not provide conclusive evidence against the conventional view that policymakers adopt anti-gay initiatives in response to domestic demands and developments; such a conclusion would require in-depth case studies of the kind provided, for Slovakia, in section five. Nevertheless, the preliminary findings are suggestive of the importance of other factors.

First, public opinion has become more supportive of homosexuality and same-sex marriage over time. This attitudinal trend runs counter to the belief that constitutional bans are adopted in response to societal demand.

The data are, admittedly, spotty. Many surveys have only recently begun to cover post-communist countries, making comparisons across countries and over time difficult. Multiple data points are unavailable for most countries. Furthermore, surveys seldom directly address same-sex marriage.

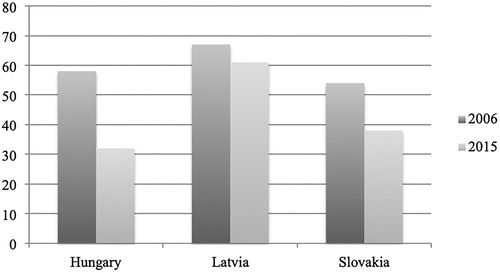

Nevertheless, the available data suggest greater tolerance toward sexual diversity. Eurobarometer data allow us to compare the positions of three EU member states, which introduced bans on same-sex unions after their accession to the Union, at two points in time. suggests that gay marriage, while still controversial, is becoming more accepted over time (European Commission Citation2006, Citation2015). The European Values Study (Citation2011), which uses respondents’ willingness to have homosexual neighbours as a more general measure of societal homophobia, confirms the growing tolerance of these three societies over time. Only Croatian respondents became slightly less tolerant over time. Finally, as an indication that traditional views on marriage are also on the wane in Armenia and Georgia, time-series data from Caucasus Barometer show a consistent decline in the percentage of respondents who believe that a divorce can never be justified (Caucasus Research Resource Centers Citation2017). These data, crude as they are, caution against connecting the bans on same-sex marriage to public opinion.

Figure 2. Percentage of respondents who “totally disagree” that homosexual marriages should be allowed throughout Europe.

Second, the influence of religious institutions on morality policy should be questioned. To begin with, while religious leaders such as Georgia’s Patriarch Ilia II and Latvia’s Archbishop Stankevičs have long denounced same-sex unions (Andersen Citation2014; Tsertsvadze Citation2016), the constitutional bans did not follow a noticeable shift in the political access of church actors. Religion became a more significant political factor immediately after most post-communist countries declared their independence, but developments since are better characterised by gradual changes – be it secularisation or religious revival (Northmore-Ball and Evans Citation2016) – than by abrupt shocks to the system. Some churches, like the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church, have a special status. They also enjoy a range of privileges (Fox Citation2008, 158). In Latvia, representatives of the major religions are part of an official advisory body of the government, the Ecclesiastical Council (Stan and Turcescu Citation2011, 93). However, since these privileges are mostly stable over time, they cannot account for the specific timing of anti-gay policies.

Even where clerics have a long-standing record of resisting same-sex unions, there is scant evidence of a public drive for constitutional change. In fact, on some occasions where churches did openly demand anti-gay measures, political leaders disregarded these calls. The Georgian Orthodox Church campaigned in vain against the inclusion of the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in the anti-discrimination law that was adopted in 2014 (Civil.Ge Citation2016). The Serbian Orthodox Church ultimately also failed to excise sexual orientation from anti-discrimination legislation (Jovanović Citation2013). There are evident limits to the influence that church actors wield over public policy.

Instead of publicly pushing for anti-gay policies, religious actors may exert their influence through political parties. Christian-Democratic parties should be particularly likely allies. Aside from the general observation that “the creation of a confessional party […] does not necessarily increase church influence” (Kalyvas Citation1998, 300), however, there is not a strong relationship between a government’s party composition and the decision to prohibit same-sex unions. When Croatia, Georgia, Montenegro and Slovakia banned same-sex marriage, social-democratic parties were in power. Religious parties may still be important, as the Slovak case will clearly demonstrate, but they are neither a necessary nor a sufficient factor for the adoption of constitutional bans.

Even in the remaining cases it is not clear that the bans can be attributed to religious actors’ close ties with political parties. In Hungary, the Catholic Church did not direct Viktor Orbán’s rebranding of Fidesz “as a nationalist, morally conservative, and religious party” (Müller Citation2011, 11). If anything, Orbán instigated the return of churches and religion to public life. He declared: “we must rediscover the nineteenth-century ideology that, beyond the separation of church and state, did not pursue a separation of religion and politics” (Orbán Citation2007, 109).

The Latvian case is especially interesting. Latvia’s First Party, nicknamed the “priests’ party” because it counts various ministers of different branches of Christianity within its ranks (Pabriks and Štokenberga Citation2006, 66), was instrumental in revising the constitution in 2006. The party even occupied the Ministry for Children and Families within the Kalvītis cabinet. This would seem to confirm the churches’ influence. But Latvia’s First Party already held such an influential position under the Repše cabinet, which took office in 2002. If the party was indeed a vehicle for religious influence, why did it take four years for this influence to materialise? To explain this, the case needs to be situated within its international context.

Third, socially conservative elements within civil society do not appear to have actively pushed to constitutionally protect the traditional family. To be sure, demands for LGBTI equality have elicited strong reactions. In Georgia, the “Family Purity Day” has been organised as a counter-event to the International Day against Homophobia since 2014. A similar “March for Life” has taken place in Slovakia. Pride marches have attracted the ire of traditionalist groups across the post-communist region. However, demonstrations against LGBTI rights seldom produced fully-formed policy proposals. The only exception is Croatia, where the citizen’s initiative “In the Name of the Family” organised a referendum that banned same-sex marriage (Petričušić, Čehulić, and Čepo Citation2017). In the other cases, the constitutional bans cannot be traced back as easily to grassroots activism.

Finally, the argument that the constitutional prohibitions are a response to internal events has only limited value. The backlash thesis potentially sheds light on two of the cases, which both make registered partnerships available for same-sex couples. In Hungary, the centre-right government of Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People’s Party revised the constitution after the previous Gyurcsány government – an alliance of social democrats and liberals – had introduced registered partnerships. The Croatian referendum, in turn, was a direct response to a proposal of the centre-left Milanović government for a Life Partnership Act. This law was ultimately only adopted after the restriction on marriage had come into being.

Yet, the backlash argument does not apply to any of the other countries, where same-sex couples enjoyed neither parental nor partnership rights. At the time of constitutional change, moreover, policymakers had not even given the provision of such rights serious thought. Discussions on this topic arose only after the traditionalist definition of marriage had been secured. Three years after Montenegro revised its constitution, the Ministry of Human and Minority Rights announced that it would “consider the possibility of regulating the legal and social status of same-sex couples” (BBC Monitoring Europe Citation2010). The situation in Serbia is similar (Balkan Insight Citation2013). It was not until 2015, nine years after the constitutional ban, that the Latvian parliament first discussed in earnest (gender-neutral) registered partnerships. The Armenian Ministry of Justice only recently announced that it would recognise same-sex marriages performed abroad. In Georgia, the ombudsman called for registered partnerships in response to the constitutional ban (OC Media Citation2018). In these cases, the constitutional bans were not driven by a backlash to the expanding rights of LGBTI nationals; they rather sparked political debate about improving the legal status of same-sex relationships.

The point continues to hold when moral protectionism is understood not as a backlash to concrete policy proposals, but instead to the increasingly louder demand for same-sex unions. To begin with, the general diagnosis that post-communist countries are characterised by a weak civil society applies all the more to activism for sexual minority rights (Howard Citation2005). Ayoub (Citation2016) shows that the embeddedness of LGBTI organisations in transnational networks stimulates the adoption of pro-LGBTI policies. ILGA-Europe’s number of member organisations from the countries that banned same-sex marriage, however, is well below average.Footnote3 More importantly, many of these organisations were either non-existent or still in their infancy when the constitutional bans were passed. The latter group lacked both material resources and political access; few parties were willing to incorporate the emergent movement’s demands into their agenda. There was simply not a strong pro-LGBTI movement for conservative lawmakers to respond to. On the contrary, repression in parts of post-communist Europe gave rise to “a trajectory of increasingly organised and influential activism” (O’Dwyer Citation2018, 3).

Furthermore, this anaemic movement did not actively demand partnership rights. It had more basic priorities: securing protection from discrimination, combating hate crime and hate speech, and overcoming social exclusion. Same-sex unions were a luxury that few activists could envision. Some even worried that raising the issue would be counterproductive. For example, when the Constitutional Court in Georgia scrutinised a complaint that the civil code’s definition of marriage was unconstitutional, “LGBT rights groups immediately distanced themselves from this lawsuit” (Civil.Ge Citation2016). Only after the constitutional bans did the call for same-sex unions grow louder.

It makes intuitive sense to attribute the constitutional bans on same-sex marriage to domestic demands and developments. Upon closer scrutiny, however, this internal perspective only captures part of the story. For a more complete picture, it is necessary to bring in the international dimension of anti-gay politics. As Heichel, Knill, and Schmitt (Citation2013, 329) observe, “the influence of international or transnational mechanisms on domestic morality policies has barely been systematically analysed so far”. The next section presents the theoretical claim that lawmakers’ fight to defend the traditional notion of marriage should indeed be seen as a type of backlash, but a precautionary one that responds to alarming developments abroad.

The anticipatory politics of banning same-sex marriage

Decisions regarding the rights of sexual minorities are not made in isolation. The prospect of joining the Council of Europe and, especially, the EU motivated the decriminalisation of homosexuality and the adoption of anti-discrimination provisions in various Central and Eastern European states. Transnational activists play an important role in this process (Ayoub Citation2016). Any explanation of the diffusion of LGBTI rights must thus take international factors into consideration.

That rights restrictions are also shaped by the international context is, however, a more recent realisation. Studies of sexual minority rights often use theories of international norms as their conceptual scaffolding, but these theories have been criticised for their “liberal bias” or preoccupation with “benign” norms (Bloomfield Citation2016, 313). Scholars are only just beginning to grapple with the fact that actors may also contest and reject liberal norms. In the international arena, such resistance may take the form of promoting rival norms (Symons and Altman Citation2015). Domestically, the resistance is preventative: lawmakers undertake steps to avoid unwanted norms from taking root in their societies.

These domestic measures are variously referred to as an “anticipatory countermovement” (Weiss Citation2013), the “politics of pre-emption” (Currier and Cruz Citation2017), and as “norm immunization” (Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Citation2017). Notwithstanding subtle differences between these accounts, they evince the same three-step logic: (1) identifying a threat to sacred values, (2) locating its origins abroad, and (3) making pre-emptive moves against this foreign threat. Together, these steps result in an anticipatory brand of politics.

Threat identification is the first step. Actors predict that a nation’s core values will come under increasing pressure and may ultimately be replaced by unwanted, morally questionable alternatives. The “process of threat construction” is central (Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Citation2017, 200). Liberian anti-gay activists believed that the spectre of homosexuality imperilled the country’s “fragile peace and national security” (Currier and Cruz Citation2017, 2). Advocates for LGBTI rights are not yet an impressive force in domestic politics, but will be in the near future. The nation is confronting a “teleologically unavoidable” threat (Weiss Citation2013, 149).

Threat attribution follows the identification of a threat. Specifically, actors trace the menace back to international sources. It may come, as was the case in Uganda, from transnational advocates of LGBTI rights (Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Citation2017). It may also emanate from the efforts of international organisations. Alternatively, the source may remain nameless; the sovereignty of a “virtuous” homeland is then claimed to be under siege by the general forces of foreign depravity (Currier and Cruz Citation2017; Weiss Citation2013). The threat is, in any case, not indigenous.

In the final stage, which I label threat resolution, actors seek to pre-empt the foreign threat. Legal barriers may be erected so as to “immunize” a country against “transnational contagion”, for example by curtailing the freedom of expression or association (Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi Citation2017, 208). Singaporean conservatives staged a hostile takeover of a feminist organisation (Weiss Citation2013, 151). In Liberia, conservative activists launched a public-education strategy with the objective of rendering the local population less susceptible to “the perils of homosexuality and LGBT activism” (Currier and Cruz Citation2017, 13). These initiatives all intended to stymie the import of immorality before local actors had even articulated a significant demand for sexual minority rights.

Given the limited explanatory power of domestic factors, I argue that the constitutional bans on same-sex marriage likely resulted from “anticipatory homophobia” (Weiss Citation2013, 151). Lawmakers were concerned that the wave of same-sex unions that was washing over the neighbourhood would soon engulf their country as well. Although there was no immediate demand for such unions, their country would not remain immune to the international trend of redefining marriage. The objective was to prevent this trend from gaining a foothold domestically. Constitutional change became the precautionary solution of choice.

The observable implications of this argument correspond to the three aforementioned steps. In presenting their proposal for a constitutional ban, and in defending their support for this proposal, lawmakers will: (1) articulate a threat of same-sex unions, (2) connect this threat to foreign actors, and (3) argue that the appropriate response consists of amending the constitution, even though the civil or family code already does not provide any legal recognition for same-sex relationships and may even explicitly prohibit such recognition. The need to nip international forces in the bud should, moreover, be the primary argument for constitutional change. The anticipatory argument will be falsified if lawmakers do not construct a foreign threat to moral sovereignty, but instead predominantly legitimise their positions with reference to domestic factors, such as societal attitudes, religious doctrine and the views of conservative civil-society groups.

I use the Slovak case to demonstrate the plausibility of the argument. The next section briefly discusses the case selection and methodology.

Methods

The Slovak example serves as a plausibility probe. This type of case study holds the middle between generating and empirically assessing theoretical arguments (Levy Citation2008). If the theoretical argument withstands scrutiny in the Slovak case, it can be expected to apply more generally. The next step in the research agenda would then be to carry out a more detailed analysis of other constitutional bans, and of negative cases.

Members of the Slovak parliament, the National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná Rada, NRSR), agreed to constitutionally prohibit same-sex marriage in March 2014. This case is a “typical case”, in the sense that existing theories, which emphasise the causal relevance of domestic factors, would seem to explain it well (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008, 299). Surveys reveal the population’s continued religious attachment and disapproval of homosexuality. 76% of Slovaks self-identify as having a religious affiliation (Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic Citation2015, 96). In 2015, only 24% of the population agreed that same-sex marriages should be allowed throughout Europe, which was a modest increase of five percentage points compared to 2006 (European Commission Citation2006, Citation2015). Public opinion thus seemed to favour a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage.

Moreover, the Catholic Church has held a powerful position in post-independence Slovakia. Critics even complained that it acted as a de facto “national church” (Stan and Turcescu Citation2011, 157). The church has “assiduously sought to protect and increase its influence in society with policies touching education, abortion, and registered partnerships” (Reban Citation2014, 59). The country’s first major demonstration for traditional family values – the so-called March for Life – was held in the streets of Košice in 2013, upon the initiative of the Bishops’ Conference of Slovakia. The number of conservative civil-society groups has also mushroomed in recent years. As one indication, almost one hundred organisations pledged their support for Bratislava’s March for Life in 2015. The Alliance for Family even initiated a referendum on traditional family values in February 2015. The constitutional ban could plausibly be attributed to these actors.

The backlash thesis also holds some promise. Ganymedes, the country’s first gay and lesbian organisation, was founded in 1990. Ten years later, several smaller organisations began to work together under the umbrella of the Initiative Otherness (Daučíková, Bútorová, and Wallace-Lorencová Citation2003, 750). A first proposal on same-sex unions – the Life Partnership Statute (2000) – was initially greeted with silence; a year later, however, a cross-partisan group of eight Members of Parliament (MPs) submitted one of the post-communist world’s earliest proposals to equate the legal “status of same-sex partnership [sic] and heterosexual matrimony in all aspects, with the exception of child adoption” (Wallace-Lorencová Citation2003, 107). This bill was defeated resoundingly. Nevertheless, there was a gay rights movement, with an apparent agenda to transform family values, which traditionalist actors could agitate against.

Yet, the empirical evidence shows that the decision to ban same-sex marriages was driven primarily by external considerations. The supposed typicality of the Slovak case thus serves to underscore that “the causal mechanisms are different than those that had been previously stipulated” (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008, 299), while simultaneously illustrating the plausibility of the theoretical argument concerning the anticipatory logic behind the constitutional prohibitions.

Methodologically, the case study relies on a triangulation of official documents and news articles related to same-sex unions between the first proposal for a Life Partnership Statute (2001) and the constitutional revision (2014). The analysis enquires into lawmakers’ discursive constructions of same-sex unions as a foreign threat and, concomitantly, their presentation of a constitutional ban as the appropriate pre-emptive response. I rely primarily on the draft bills, the explanatory protocols and the transcripts of parliamentary debates.Footnote4 I collected English-language news articles from three main sources: the BBC’s Monitoring Europe service, the Slovak Spectator, and The Daily. The analysis is further informed by 27 semi-structured interviews that I conducted with policy elites in Bratislava in January-February 2017.Footnote5

These sources show that lawmakers did not change the constitution in response to identifiable demands from the public or traditionalist interest groups. Nor did they seek to counterbalance the domestic expansion of LGBTI rights. Instead, the ban was the fulfilment of a longstanding wish of conservative lawmakers to protect the Slovak nation from the licentiousness that threatened to follow from EU membership. The measure, in other words, constituted a backlash to international developments.

A shelter from the liberal storm: Slovak conservatives’ constitutional crusade against same-sex marriage

In June 2014, same-sex couples’ hopes of tying the knot in Slovakia were dashed. Lawmakers agreed upon a heteronormative redefinition of Article 41 of the constitution: “marriage is a unique union between a man and a woman” (Slovak Republic Citation2014). This amendment did not come about suddenly. It marked the endpoint of a hard-fought campaign by Christian-Democratic politicians to shelter the traditional family from the liberal storm that was blowing over the European continent.

This campaign not only predated Slovakia’s EU membership in 2004, but also was a direct response to European integration. The path toward the constitutional revision was long: over a period of twelve years, the Christian Democrats initiated a declaration of national sovereignty in cultural and ethical affairs; enshrined a heterosexual definition of marriage into the country’s family code; and, on two occasions, failed to amend the constitution. They were only victorious upon their third attempt to prohibit same-sex marriages. The message of conservative lawmakers was consistent throughout this campaign: the country needed to take preventive measures against the increasing international pressure to grant legal recognition to gay couples.

The Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) identified the threat of same-sex marriage ahead of EU accession. It drafted a statement that would allow Slovakia to enjoy the benefits of European integration, while avoiding its moral costs. This Declaration on the Cultural and Ethical Sovereignty of Member and Candidate States of the European Union was meant to ensure that the institution of marriage, among other contentious issues, remained within the “exclusive competence” of candidate and member states (NRSR Citation2002).Footnote6

This initiative was motivated by the challenge that a “non-traditional” view mounted to “the traditional view of the family” across the continent. The KDH observed a worrying tendency to treat “homosexual behaviour as equivalent to heterosexual behaviour” and, consequently, to demand “new human rights” (NRSR Citation2002). This demand had already compelled various countries to legalise registered partnerships.

Importantly, international organisations had become a new and prominent battleground for defining human rights. The KDH feared that the anti-discrimination article of the EU’s Treaty of Amsterdam, which covered sexual orientation, would function as a “springboard” for LGBTI activism, potentially spilling over into family law (NRSR Citation2002). The party accordingly dragged its feet when it came to the transposition of EU anti-discrimination legislation. Ján Čarnogurský, the Minister of Justice, attributed his party’s obstructionism to the belief that “same-sex marriages degrade the family” (Schulze Citation2008, 107). Marriage fell outside the scope of EU law, but the KDH feared competence creep. They pointed to “the growing influence of the European Parliament”, which clung to a “non-traditional cultural-ethical point of view” (NRSR Citation2002). Warning of the pressure awaiting Slovakia, the KDH noted that the EU had tried to badger Poland into supporting the Union’s position on sexual and reproductive health and rights at the five-year review of the United Nations’ Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. There was thus a real fear that the EU would impose morally unacceptable policies, including same-sex unions, upon Slovakia.

This perceived threat persisted even after the declaration on sovereignty was adopted. The Christian Democrats believed that additional buffers were needed. The first step was to revise the Family Act. At the behest of the KDH, a junior coalition party within the centre-right cabinet of Mikuláš Dzurinda, the government redrafted this law so that Article 1 defined marriage in exclusively heterosexual terms and clarified that its purpose consisted of founding a family and raising children (NRSR Citation2004b). The intention was to prevent the “pervasive relativism and experimentation” regarding questions of “the role of marriage and the natural family” from affecting Slovakia (NRSR Citation2004a). Daniel Lipšic, the Christian-Democratic Minister of Justice, spearheaded this legislative change.Footnote7

However, the new code did not provide enough reassurance to the KDH. There was a lingering worry that European institutions would use anti-discrimination reasoning to impose same-sex unions. A sturdier buffer was needed: the traditionalist definition of marriage should not only be anchored in the family code, but in the constitution as well. Conservative lawmakers submitted three draft laws to this end: in 2006, 2009, and 2014.Footnote8 They succeeded on their third try, when the governing party – the Social Democrats of Prime Minister Robert Fico – sensed an opportunity for a trade-off. The Smer party agreed to the constitutional ban on same-sex marriage in exchange for the KDH’s willingness to endorse controversial reforms of the judiciary.

The conservatives’ argumentation was consistent across all three proposals: same-sex unions put traditional family values at risk; the danger came from progressive actors at the European level; and the danger could be averted by enshrining a heteronormative understanding of marriage into the Slovak Constitution. I discuss these three steps in turn.

Threat identification

To begin with, the status of the traditional family, founded upon a heterosexual marriage, was in jeopardy. This social institution found itself in the crosshairs of “totalitarian ideologies” characterised by excessive devotion to materialism and individualism. “The most serious threat” was “the push to change the definition of marriage as a union between men and women” (NRSR Citation2006, Citation2009b). The KDH believed it imperative to respond to the “more and more frequent relativism” in matters of marriage and the family (NRSR Citation2014a).

When defending their initiatives, conservative deputies consistently warned that the time-honoured “Judeo-Christian notion of marriage” was under attack “across Europe and North America”. Revolutionaries were using “salami tactics” to dismantle the traditional family (NRSR Citation2009a). In the words of Rudolf Bauer, a representative of the Conservative Democrats of Slovakia (KDS), a short-lived grouping that broke away from the KDH in 2008,Footnote9 “today’s world is facing not only an economic crisis, but also a crisis of morality […] characterised by the breakdown of family values” (NRSR Citation2009a). The traditional family, the cornerstone of the Slovak nation, was in peril.

This breakdown posed a real danger to the future of Slovakia and human civilisation more generally. As Peter Muránsky argued, “every civilization that turned its back on its own values has ceased to exist […] Those that embraced the so-called ‘culture of death’ have perished” (NRSR Citation2014c). Same-sex unions would usher in a demographic winter: they would devalue the institution of marriage and, consequently, lead to a drop in the number of traditional marriages and families. It was clear, as Martin Fronc summarised it, that “the human race would have died out” if it had placed homosexual and heterosexual partnerships on an equal footing a long time ago (NRSR Citation2014c).

Threat attribution

Second, the KDH believed the roots of the ideological pressure to be “above all international” (NRSR Citation2006). It especially saw the European institutions as sites of immorality. Christian Democrats cited a plethora of attempts to undermine the traditional family: a Dutch proposal within the Council of Ministers for the mutual recognition of registered partnerships, which would have resulted in the “federalization of family law” if Slovakia had not put its foot down (NRSR Citation2006); the European Parliament’s frequent questioning of “the value of marriage and family” (NRSR Citation2006); and the European Convention on the Adoption of Children, a document of the Council of Europe that was mistakenly claimed to grant adoption rights to homosexual couples (NRSR Citation2009b). The Lisbon Treaty would only increase the threat level because it gave legal force to the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. Progressive actors could then arm themselves with “another legal argument in favour of the redefinition of marriage” by combining the Charter’s provisions on non-discrimination and the right to marry (NRSR Citation2009b). The root of the problem thus unequivocally lay abroad.Footnote10

The threat attribution within the National Council looked the same. The Lisbon Treaty was a “nightmare” for František Mikloško (KDS), because it would allow European courts to overrule the Slovak family code:

Our laws state that a family and marriage is made up of a man and a woman. But once an individual […] turns to the court in Strasbourg or Luxembourg and says that Slovak law suppresses his rights, so that he cannot create a [legal] partnership with a person of the same sex, then the court in Strasbourg or Luxembourg will side with him and will abolish the provisions of our law. That’s how it will be!

The Lisbon Treaty thus “fundamentally changes the political and social character of the Slovak Republic” (NRSR Citation2009a). Five years later, after the treaty had gone into effect, Mikloško remained concerned: “Everyone feels that the family is in crisis, that the institution of marriage is in crisis, that Europe is subjecting these institutions to a powerful attack” (NRSR Citation2014c). One of his peers, Vladimír Palko, similarly pointed to the threat that came from Brussels and Strasbourg:

A month ago, the European Parliament adopted a resolution. In this resolution, it calls on all Member States of the European Union to recognise registered partnerships or marriages of same-sex couples. Ladies and gentlemen, what will our answer be? Will we stick our heads in the sand? Will we keep silent? (NRSR Citation2014c)

Other countries served as a portent of the bleak future that awaited Slovakia if lawmakers refused to act. Attacks on religious freedom were “already in full swing” in, for example, the United Kingdom and Spain (NRSR Citation2009a). The total number of marriages had, across the EU, fallen “by about 750,000 since 1980”. In Europe, the number of unborn children was estimated at thirty million since 1999 (NRSR Citation2014c). The traditional family in Slovakia could soon befall a similar fate.

What is more, the conservatives accused other Slovak parties of aiding and abetting the international enemy. The voting behaviour of the “Socialists and Liberals” in the European Parliament helped “to put pressure on the Slovak Republic to recognise and accept registered partnerships and same-sex marriage” (NRSR Citation2009a). Importantly, however, these parties did not ardently promote same-sex unions. They instead behaved like characters in “Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel [sic] Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”: claiming to protect Slovakia’s “cultural traditions” at home, while facilitating their demise abroad (NRSR Citation2009a). The conservatives’ political opponents were not the instigators of LGBTI liberation, but the accomplices of international actors. The real threat came from the latter category of actors.

Threat resolution

Finally, prudent foresight called for constitutional change. The lawbooks in many socially conservative countries, including Slovakia, actually played into the European liberals’ hands. The KDH claimed that the “threat to marriage is facilitated by the fact that the constitutions of several states lack a special protection of marriage compared to other types of cohabitation”. The heterosexual definition of marriage had “traditionally been so obvious” that it did not require constitutional specification (NRSR Citation2006). Foreign developments had changed the situation. If lawmakers did not want their country to be vulnerable to the forced import of non-traditional values, they should take the precautionary step of constitutionally prohibiting same-sex unions.

Furthermore, both the present and future governments of Slovakia, in exercising “their competencies related to membership of international organizations, especially of the EU”, would have to respect the constitutional definition of marriage (NRSR Citation2006). The idea was thus that, should the Union acquire a say over family law, Slovak leaders would be constitutionally compelled to reject partnership rights for same-sex couples. In short, the legal change warded off the existential threat that European-style liberalism posed to the traditional family.

Parliamentary representatives underlined this problem-oriented rationale in their speeches. The intention was not to discriminate against sexual minorities but to secure the future of the Slovak nation. “Strengthening marriage”, according to Rudolf Bauer, was a “prerequisite for strengthening the family and gradually reversing unfavourable demographic trends” (NRSR Citation2009a). Furthermore, the ban would hold the European institutions at bay. Slovakia would be forced to suffer “the political consequences of the Treaty of Lisbon”, according to Mikloško, “unless we agree to this constitutional ban” (NRSR Citation2009a). The following contribution by Pavol Zajac summarises the KDH’s thinking:

There needs to be a certain barrier, protecting the future against irresponsible politicians who, as in other Western European countries, will try to come up with proposals, first on registered partnerships […], then marriage for homosexual couples, followed by adoption for these homosexual, married couples, and then euthanasia. (NRSR Citation2014b)

The ban on same-sex marriage would provide protection from the liberal tide that was washing over the continent. This was, according to Ján Hudacký, “the only way to save both Slovakia and Europe” (NRSR Citation2014b).

Together, the three steps – threat identification, attribution and resolution – make clear that the KDH’s crusade was not a purely domestic affair; it can only be explained if the international dimension of political homophobia is taken into consideration. It was, as one deputy aptly put it, a “defensive reaction” to certain “tendencies” that could be observed elsewhere in Europe (NRSR Citation2014b).

Conclusion

In 2014, the leader of the KDH, Ján Figeľ, presented the third and final proposal for a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage to his parliamentary colleagues. He remarked that, a decade before, Slovak politicians were confronted with a pressing issue on which a “significant degree of consensus” existed within society: deciding whether or not to join a “Common Europe”. The situation looked similar ten years later, except now the issue was “the status of marriage and the family” (NRSR Citation2014c).

These words would appear to support the argument that the constitutional ban was due to domestic factors: the constitution was updated in order to reflect the fact that most Slovaks subscribed to a traditional understanding of marriage. Conservative lawmakers, in fact, often referred to public opinion in their speeches. This account, however, struggles to explain the precise timing of the proposed constitutional revisions. Public opinion was furthermore becoming gradually more tolerant. Other theoretical arguments, which explain the anti-gay proposals as a backlash to internal developments or which emphasise the successful campaign efforts of religious institutions and civil-society groups, are not supported by the official record either. A comprehensive understanding of the constitutional change requires more attention to be paid to the international dimension of anti-gay politics.

Indeed, what is remarkable about Figeľ’s words is less his emphasis on societal consensus, but the connection he draws between same-sex unions and the EU. A complete account of the constitutional ban in Slovakia rests, as I have shown, on this connection. Conservative politicians identified same-sex unions as a foreign threat to traditional family values. The conservatives advocated for a “politics of pre-emption” (Currier and Cruz Citation2017): while there was no immediate domestic cause for concern, worrying developments abroad called for anticipatory action in the form of a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage.

The main theoretical implication is that scholars of morality politics should bring the international dimension into their analysis. Domestic factors were central to the Slovak ban. After all, it came about following a persistent campaign by a domestic party. The conservatives, moreover, would almost certainly not have pursued this campaign if it had contradicted public opinion or church doctrine. However, these factors – the presence of a religious party, conservative public opinion and support from religious actors – should be supplemented with a focus on international developments. Only then can the adoption of constitutional bans be fully understood.

Future research could extend the argument in several ways. First, it could assess whether important international considerations influenced the bans on same-sex marriage elsewhere as well. Preliminary evidence suggests that they did. In Georgia, constitutional change came shortly before the adoption of an anti-discrimination law, which, in preparation for an association agreement with the EU, banned discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The ban on same-sex marriage was meant to alleviate the fear that closer ties with the EU were “synonymous with gay marriage” (Lomsadze Citation2014). Latvia’s First Party believed that “altering the constitution was necessary to protect the institution of marriage from EU anti-discrimination legislation” (Eglitis Citation2005). The argument also applies to failed cases. Ahead of the Romanian referendum in October 2018, the leader of the Social Democrats declared: “many fear that what has happened in other countries, such as legalizing marriage between a man and an animal, could happen here” (Ilie Citation2018). A more systematic study is needed to definitively show that these countries’ attempts to ban same-sex marriage were indeed motivated by ill-boding trends in the region.

Second, scholars could examine the scope of the argument. I have focused on constitutional bans that were adopted after 2001, when the Netherlands became the first country to legalise same-sex marriage. It is in this period that calls for pre-empting foreign pressure are most probable. Yet, six countries in Central and Eastern Europe already had constitutional bans in place before 2001. Were international considerations absent in these cases? Or were these bans adopted in response to the Danish decision to recognise registered partnerships in 1989, which put supporters of the traditional family on the defensive across the continent? If the latter holds true, my argument’s temporal scope should be broadened.

Third, the argument should also apply to other expressions of political homophobia, such as the adoption of an anti-gay propaganda law in Lithuania or the anti-gay resistance to a law on gender equality in Armenia. The latter, as one sociologist noted, represented a clear “backlash against Europe” (Grigoryan Citation2013). Furthermore, the anticipatory logic may be observed in other battles of the so-called “culture wars” between progressive and traditionalist voices, including sexual and reproductive health and rights. These battles are not exclusively fought at the domestic level; conservative actors may also try to act pre-emptively within international organisations (Stoeckl and Medvedeva Citation2018). Scholars should thus take care to situate their analyses of LGBTI rights within the proper context. More often than not, this context will have a prominent international dimension to it.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments, I thank Peter Katzenstein, Matthew Evangelista, Alexander Kuo, Mona Krewel and the reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributor

Martijn Mos is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University. His work has appeared in JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, the Journal of Contemporary European Research and the European Journal of Politics and Gender.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Azerbaijan, Italy and Romania have non-constitutional, statutory bans.

2 Adam, Knill, and Budde (Citation2019) in fact argue that Christian Democrats “are very reluctant to adopt restrictive morality policy reforms”.

3 Author’s calculations (28 November 2018).

4 These sources are publicly accessible at the Digital Parliamentary Library of the Czech and Slovak Parliaments.

5 A list of interviewees is available from the author.

6 All translations are the author’s.

7 The primary objective of the legislative change was to clarify parental responsibilities. The heteronormative redefinition of marriage was snuck into the proposal.

8 In 2012, the libertarian Freedom on Solidarity (SaS) submitted a proposal for registered partnerships. Because it was resoundingly rejected, I do not consider it further here. Neither this law nor the ascendancy of the libertarian party caused a backlash against LGBTI rights; the Christian Democrats’ efforts to constitutionally prohibit same-sex marriage predated the founding of Freedom and Solidarity in 2009.

9 The KDS submitted the 2009 proposal, but was backed by the KDH.

10 The constitutional solution was not homegrown either. Conservative MPs cited several examples to illustrate that “the constitutional protection of marriage is widespread”, and that the number of countries that have taken such protective steps was increasing (NRSR Citation2006, Citation2009b).

Bibliography

- Adam, C., C. Knill, and E. T. Budde. 2019. “How Morality Politics Determine Morality Policy Outputs – Partisan Effects on Morality Policy Change.” Journal of European Public Policy, Online first.

- Adamczyk, A. 2017. Cross-national Public Opinion About Homosexuality: Examining Attitudes Across the Globe. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Andersen, K. 2014, October 10. Latvian Archbishop: ‘Homosexual Relationships are Destroying our Human Identity.’ LifeSiteNews. Retrieved from https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/latvian-archbishop-homosexual-relationships-are-destroying-our-human-identi.

- Anić, J. R. 2015. “Gender, Gender ‘Ideology’ and Cultural War: Local Consequences of a Global Idea – Croatian Example.” Feminist Theology 24 (1): 7–22.

- Ayoub, P. M. 2016. When States Come Out: Europe’s Sexual Minorities and the Politics of Visibility. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Balkan Insight. 2013, May 29. Serbia Mulls Offering Rights to Gay Couples. Retrieved from http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/serbia-to-regulate-status-of-same-sex-partners.

- BBC Monitoring Europe. 2010, December 21. Montenegrin Government Willing to Consider Same Sex Marriages.

- Bloomfield, A. 2016. “Norm Antipreneurs and Theorising Resistance to Normative Change.” Review of International Studies 42: 310–333.

- Bosia, M. J., and M. L. Weiss. 2013. “Political Homophobia in Comparative Perspective.” In Global Homophobia, edited by M. L. Weiss, and M. J. Bosia, 1–29. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Caucasus Research Resource Centers. 2017. Caucasus Barometer Time-Series Dataset. Retrieved from http://www.caucasusbarometer.org/.

- Ciobanu, C. 2017. “Romania 'Turns Illiberal' with Moves against Gay Marriage.” Politico, June 10. https://www.politico.eu/article/romania-gay-marriage-turns-illiberal-with-moves-against/.

- Civil.Ge. 2016, March 8. GD Refloats Proposal on Setting Constitutional Bar to Same-Sex Marriage. Retrieved from https://civil.ge/archives/125345.

- Corredor, E. S. 2019. “Unpacking “Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’s Antigender Countermovement.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44 (3): 613–638.

- Currier, A., and J. M. Cruz. 2017. “The Politics of pre-Emption: Mobilisation Against LGBT Rights in Liberia.” Social Movement Studies 19 (1): 82–96.

- Daučíková, A., Z. Bútorová, and V. Wallace-Lorencová. 2003. “The Status of Sexual Minorities.” In Slovakia 2002: A Global Report on the State of Society, edited by G. Mesežnikov, M. Kollár, and T. Nicholson, 743–756. Bratislava: IVO: Institute for Public Affairs.

- Dorf, M. C., and S. Tarrow. 2014. “Strange Bedfellows: How an Anticipatory Countermovement Brought Same-Sex Marriage Into the Public Arena.” Law & Social Inquiry 39 (2): 449–473.

- Eglitis, A. 2005, December 21. MPs Ban Same-Sex Marriages. Baltic Times. Retrieved from http://m.baltictimes.com/article/jcms/id/113751/.

- Engeli, I., C. Green-Pedersen, and L. T. Larsen. 2012. “Introduction.” In Morality Politics in Western Europe: Parties, Agendas and Policy Choices, edited by I. Engeli, C. Green-Pedersen, and L. T. Larsen, 1–4. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Euchner, E.-M. 2019. Morality Politics in a Secular Age: Strategic Parties and Divided Governments in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- European Commission. 2006. Eurobarometer 66: First Results. Eurobarometer 66: Brussels, December.

- European Commission. 2015. Discrimination in the EU in 2015. Special Eurobarometer 437: Brussels, October.

- European Values Study. (2011). “European Values Study 2008 Integrated Dataset.” GESIS Data Archive.

- Fetner, T. 2008. How the Religious Right Shaped Lesbian and Gay Activism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Fox, J. 2008. A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grigoryan, M. 2013, October 11. Armenia: Fight against Gender-Equality Morphs into Fight Against EU. Eurasianet. Retrieved from https://eurasianet.org/armenia-fight-against-gender-equality-morphs-into-fight-against-eu.

- Grzymała-Busse, A. M. 2015. Nations Under God: How Churches use Moral Authority to Influence Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Guasti, P., and L. Bustikova. 2019. “In Europe's Closet: The Rights of Sexual Minorities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” East European Politics. doi:10.1080/21599165.2019.1705282.

- Haider-Markel, D. P., and M. S. Kaufman. 2006. “Public Opinion and Policy Making in the Culture Wars: Is There a Connection Between Opinion and State Policy on Gay and Lesbian Issues?” In Public Opinion in State Politics, edited by J. E. Cohen, 163–182. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Heichel, S., C. Knill, and S. Schmitt. 2013. “Public Policy Meets Morality: Conceptual and Theoretical Challenges in the Analysis of Morality Policy Change.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (3): 318–334.

- Hildebrandt, A., E.-M. Trüdinger, and S. Jäckle. 2017. “Sooner or Later: The Influence of Public Opinion and Religiosity on the Enactment of Laws Recognizing Same-sex Unions.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (8): 1191–1210.

- Holzhacker, R. 2013. “State-Sponsored Homophobia and the Denial of the Right of Assembly in Central and Eastern Europe: The “Boomerang” and the “Ricochet” Between European Organizations and Civil Society to Uphold Human Rights.” Law & Policy 35 (1–2): 1–28.

- Howard, M. M. 2005. The Weakness of Civil Society in Post-Communist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Htun, M., and S. L. Weldon. 2015. “Religious Power, the State, Women’s Rights, and Family Law.” Politics & Gender 11 (03): 451–477.

- Ilie, L. 2018, October 6. Romanians Vote on Constitutional Ban on Same Sex Marriage. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-romania-referendum/romanians-vote-on-constitutional-ban-on-same-sex-marriage-idUSKCN1MG002.

- In ‘t Veld, S. 2019, May 3. Follow-up Letter to Jan Fígel on the Press Conference with Anti-choice Organisations. Retrieved from https://www.sophieintveld.eu/follow-up-letter-to-jan-f%C3%ADgel-on-the-press-conference-with-anti-choice-organisations/.

- Jovanović, M. 2013. “Silence or Condemnation: The Orthodox Church on Homosexuality in Serbia.” Družboslovne Razprave 29 (73): 79–95.

- Kalyvas, S. N. 1998. “From Pulpit to Party: Party Formation and the Christian Democratic Phenomenon.” Comparative Politics 30 (3): 293.

- Klarman, M. J. 2013. From the Closet to the Altar: Courts, Backlash, and the Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Knill, C., C. Adam, and S. Hurka, eds. 2015. On the Road to Permissiveness? Change and Convergence of Moral Regulation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kollman, K. 2007. “Same-Sex Unions: The Globalization of an Idea.” International Studies Quarterly 51: 329–357.

- Korycki, K., and A. Nasirzadeh. 2013. “Homophobia as a Tool of Statecraft: Iran and Its Queers.” In Global Homophobia, edited by M. L. Weiss, and M. J. Bosia, 174–195. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Kuhar, R., and D. Paternotte, eds. 2017. Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing Against Equality. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Levy, J. S. 2008. “Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (1): 1–18.

- Lewis, G. B., and S. S. Oh. 2008. “Public Opinion and State Action on Same-Sex Marriage.” State and Local Government Review 40 (1): 42–53.

- Lomsadze, G. 2014, April 2. Georgia to Consider a Ban on Same-Sex Marriage. Eurasianet. Retrieved from https://eurasianet.org/georgia-to-consider-a-ban-on-same-sex-marriage.

- Meyer, D. S., and S. Staggenborg. 1996. “Movements, Countermovements, and the Structure of Political Opportunity.” American Journal of Sociology 101 (6): 1628–1660.

- Müller, J.-W. 2011. “The Hungarian Tragedy.” Dissent 58 (2): 5–10.

- Norrander, B., and C. Wilcox. 1999. “Public Opinion and Policymaking in the States: The Case of Post-Roe Abortion Policy.” Policy Studies Journal 27 (4): 707–722.

- Northmore-Ball, K., and G. Evans. 2016. “Secularization Versus Religious Revival in Eastern Europe: Church Institutional Resilience, State Repression and Divergent Paths.” Social Science Research 57: 31–48.

- NRSR. 2002. Deklarácia Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky o zvrchovanosti členských štátov Európskej únie a štátov kandidujúcich na členstvo v Európskej únii v kultúrno-etických otázkach [Declaration of the National Council of the Slovak Republic on the Sovereignty of the Member States of the European Union and of the States Applying for Membership of the European Union in Cultural and Ethical Issues]. No. 1853: Bratislava, January 30.

- NRSR. 2004a. Transcript of parliamentary session (9 December).

- NRSR. 2004b. Vládny návrh zákona o rodine a o zmene a doplnení niektorých zákonov [Government Bill on the Family Code and on the Amendment of Certain Laws]. 838: Bratislava, August 20.

- NRSR. 2006. Návrh skupiny poslancov Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky na vydanie ústavného zákona o ochrane manželstva [Proposal of a Group of Deputies of the National Council of the Slovak Republic for a Constitutional Act on the Protection of Marriage]. No. 1530: Bratislava, February 24.

- NRSR. 2009a. Transcript of parliamentary session (18 February).

- NRSR. 2009b. Návrh skupiny poslancov Národnej rady Slovenskej republiky na vydanie ústavného zákona o ochrane manželstva [Proposal of a Group of Deputies of the National Council of the Slovak Republic for a Constitutional Act on the Protection of Marriage]. No. 913: Bratislava, January 15.

- NRSR. 2014a. Predkladacia správa [Draft Report]. No. 891: Bratislava, February 24.

- NRSR. 2014b. Transcript of parliamentary session (21 March).

- NRSR. 2014c. Transcript of parliamentary session (20 March).

- Nuñez-Mietz, F. G., and L. García Iommi. 2017. “Can Transnational Norm Advocacy Undermine Internalization? Explaining Immunization Against LGBT Rights in Uganda.” International Studies Quarterly 61 (1): 196–209.

- OC Media. 2018, April 6. Public Defender Urges Georgia to Adopt Civil Partnerships for Queer Couples. Retrieved from http://oc-media.org/public-defender-urges-georgia-to-adopt-civil-partnerships-for-queer-couples/.

- O’Dwyer, C. 2018. Coming Out of Communism: The Emergence of LGBT Activism in Eastern Europe. New York: New York University Press.

- Orbán, V. 2007. “The Role and Consequences of Religion in Former Communist Countries.” European View 6 (1): 103–109.

- Pabriks, A., and A. Štokenberga. 2006. “Political Parties and the Party System in Latvia.” In Post-communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems, edited by S. Jungerstam-Mulders, 51–68. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Petričušić, A., M. Čehulić, and D. Čepo. 2017. “Gaining Political Power by Utilizing Opportunity Structures: An Analysis of the Conservative Religious-Political Movement in Croatia.” Croatian Political Science Review 54 (4): 61–84.

- Reban, M. 2014. “The Catholic Church in the Post-1989 Czech Republic and Slovakia.” In Religion and Politics in Post-Socialist Central and Southeastern Europe: Challenges Since 1989, edited by S. P. Ramet, 53–85. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roggeband, C., and A. Krizsán. 2018. “Reversing Gender Policy Progress: Patterns of Backsliding in Central and Eastern European New Democracies.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 1 (3): 367–385.

- Schmitt, S., E.-M. Euchner, and C. Preidel. 2013. “Regulating Prostitution and Same-sex Marriage in Italy and Spain: The Interplay of Political and Societal Veto Players in Two Catholic Societies.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (3): 425–441.

- Schulze, M. 2008. “Slovakia.” In Compliance in the Enlarged European Union: Living Rights or Dead Letters?, edited by G. Falkner, O. Treib, and E. Holzleithner, 93–123. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Seawright, J., and J. Gerring. 2008. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 294–308.

- Slovak Republic. 2014. Constitution of the Slovak Republic. Retrieved from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Slovakia_2014.pdf?lang=en.

- Soule, S. A. 2004. “Going to the Chapel? Same-Sex Marriage Bans in the United States, 1973–2000.” Social Problems 51 (4): 453–477.

- Stan, L., and L. Turcescu. 2011. Church, State, and Democracy in Expanding Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 2015. The 2011 Population and Housing Census: Facts about Changes in the Life of the Slovak Population. No. 900-0101/2015: Bratislava, December.

- Stoeckl, K., and K. Medvedeva. 2018. “Double Bind at the UN: Western Actors, Russia, and the Traditionalist Agenda.” Global Constitutionalism 7 (3): 383–421.

- Stone, A. L. 2012. Gay Rights at the Ballot Box. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Stone, A. L. 2016. “The Impact of Anti-Gay Politics on the LGBTQ Movement: The Impact of Anti-Gay Politics on the LGBTQ Movement.” Sociology Compass 10 (6): 459–467.

- Symons, J., and D. Altman. 2015. “International Norm Polarization: Sexuality as a Subject of Human Rights Protection.” International Theory 7 (01): 61–95.

- Tsertsvadze, C. 2016, March 29. Patriarch Ilia II: “I said what I had to. And if I had been silent, it would have been shocking”. Orthodox Christianity. Retrieved from http://orthochristian.com/92061.html.

- Turcescu, L., and L. Stan. 2005. “Religion, Politics and Sexuality in Romania.” Europe-Asia Studies 57 (2): 291–310.

- Van Klinken, A. 2013. “Gay Rights, the Devil and the end Times: Public Religion and the Enchantment of the Homosexuality Debate in Zambia.” Religion 43 (4): 519–540.

- Wallace-Lorencová, V. 2003. “Queering Civil Society in Postsocialist Slovakia.” Anthropology of East Europe Review 21 (2): 103–110.

- Weiss, M. L. 2013. “Prejudice Before Pride: Rise of an Anticipatory Countermovement.” In Global Homophobia, edited by M. L. Weiss, and M. J. Bosia, 149–173. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.