ABSTRACT

This article uses data from the 2015 Polish parliamentary election to test the relationship between political knowledge, socio-economic status and populist attitudes. Recent scholarship has challenged the idea that populism is an unsophisticated form of politics that appeals primarily to the ill-informed and those of low social status. We find that while lower levels of political knowledge are associated with higher levels of populism, it is nevertheless ‘informed populists' who are more likely to vote for populist parties, while ‘uninformed populists' are more likely to abstain. These findings challenge the stereotype of populism as ‘politics for stupid people'.

Introduction

While we now know much about who votes for populists, we know less about why they do it. Do populist attitudes play a distinct role in explaining the voting behaviour of those who vote for populist parties, or can voting for populists be explained best by the same theories of vote choice that account for the voting behaviour of the electorates of “mainstream” parties? (Mudde Citation2010, 1181) There are many routes into this question. This article explores one: the link between political knowledge and populism.

The motivation for addressing this question arises from the “folk wisdom” that there is something inherently anti-intellectual about populism, a sentiment captured in the recurrent assertion that populism is “the political science of providing simple answers to complex questions” (Drehle Citation2019). This approach to understanding populism regards it as rooted in a common-sense authenticity that is naturally antithetical to ideas, arguments and institutional behaviours that are overburdened with complexity and uncertainty. To complicate the issue is to attempt to obfuscate it, while to speak plainly is a hallmark of the trustworthy politician. Instead of the dry, colourless and rational discourse of “high-cultural” mainstream politicians, populists express their appeal in a “low-cultural” discourse which is coarse, impolite and direct (Ostiguy Citation2017, 78).

Most articulations of this understanding of populism focus on the supply side: on rabble-rousing politicians offering simple solutions to complex problems; on unscrupulous ideological entrepreneurs taking advantage of the low political sophistication and bounded rationality of the average voter; on parties which consciously set themselves against the intellectual pretensions of the establishment. The corollary is usually left unstated: to support populists is to embrace crude and unsophisticated ideas and to eschew the moral and practical complexity of “serious” politics. In its bluntest and most derogatory expression: if politics is showbusiness for ugly people, populism is politics for stupid people.

Yet is the stereotype of the “uninformed populist” justified? What is the relationship between populism, political knowledge and voting behaviour? Using the case of the Polish election in 2015, in which the main line of competition ran between populist and non-populist parties, this article aims to answer these questions. The stereotype of the “uninformed populist” connotes a voter who combines populist attitudes with low political knowledge and primarily does so from a position of low socio-economic status reflective of the aforementioned “low-cultural” discourse. To this, we counterpose an alternative: the “informed populist”. The political preferences of the informed populist are correlated with populist attitudes, but also with higher levels of political knowledge, which in turn are associated with a socio-economic status typical of the “sophisticated voters” that populists supposedly fail to attract.

Our research design and data do not enable us to make causal statements about the relationships between populism, political knowledge and voting behaviour. However, the probabilistic associations we uncover will help to confirm, refute or at least problematise a persistent stereotype about populist voting in ways which are tractable for further comparative analysis and causal investigation.

Unsophisticated or unsatisfied? Conceptualising the relationship between populism and political knowledge

Against concepts of populism that envisage it as a performative mode of political conduct, the concept we employ in this article conceives of populism as a manner of thinking. In Mudde’s (Citation2004, 543) oft-cited definition, populism is an ideology which “considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and … argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people”. Yet populism, as a “thin-centred” ideology, “lacks the capacity to put forward a wide-ranging and coherent programme for the solution to crucial political questions” (Stanley Citation2008, 95). It explains the world of the political as simple in its essence: politics is reducible to an asymmetrical clash of power between a popular collectivity whose thwarted interests are legitimate, and a caste of elites whose realised interests are illegitimate.

In contrast to approaches that define populism as a supply-side political strategy or style, the ideational approach allows us to examine the demand for populism among mass publics, in the form of latent sets of values and attitudes that correspond with, and are activated by, the populist appeals of ideological entrepreneurs. There is a substantial body of literature on the supply-side of populism that tells us a great deal about the nature of populist political parties, political leaders, electoral programmes, campaign messages, political narratives and discourses, and much work has been done analysing the sociodemographic characteristics and ideological orientations of these parties’ electorates. Yet the demand-side literature concerning specifically populist voters is at an earlier stage of development. Over the last few years, several studies have used dedicated measures to operationalise populist attitudes directly, rather than through unsatisfactory proxies, and to explore the correlation of these attitudes with other values and their impact on voting behaviour (Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Citation2014; Andreadis et al. Citation2019; Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2016; Stanley Citation2008, Citation2018; Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel Citation2018). There is also a burgeoning literature that uses experimental methods to explore the impact of parties’ populist appeals on the electorate (Bos, van der Brug, and de Vreese Citation2013; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese Citation2016). Yet many areas remain under-explored. The relationship between political knowledge and populism is one of them.

The uninformed populist

The stereotype of the uninformed populist assumed that political knowledge is an important factor in the relationship between populist attitudes and vote choice. Intuitively, the notion of the supporters of populist parties as political unsophisticates is compelling, as it appears to proceed from the very nature of populism itself. If populists offer unrealistic solutions to social problems and make proposals which are naïve and ingenuous, this is not just a product of dishonesty or laziness but a reflection of populism's uncomplicated ontological, normative and moral claims. The stereotype of the uninformed populist flows from populism's ideologically “thin” character: unsophisticated narratives and discourses are the logical corollary of an ideology that fails to offer intellectually consistent and practical responses to the myriad problems of contemporary society (Stanley Citation2008). If populism is simple, then populists and their supporters must also be characterised by simplicity.

This is a claim which seems plausible when one considers the numerous cases of populists – Silvio Berlusconi, Hugo Chavez, Andrzej Lepper, Pauline Hanson, Jean-Marie Le Pen – who have consciously adopted a transgressive, demotic style and railed against the obfuscatory complexity of the establishment. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that the very language of populist politicians reflects the simplicity of the populist worldview. In a study that covers Austrian and German parties in the period 1945–2013, Bischof and Senniger (Citation2018, 483) find that parties which employ populist rhetoric tend to have a lower degree of linguistic complexity in their manifestos. This finding is echoed in recent studies of President Donald Trump's rhetoric (Kayam Citation2018; Oliver and Rahn Citation2016).

The stereotype of the uninformed populist posits a receptive consumer of populist messages, and one whose receptivity is conditioned by the same kind of simplicity in which the message is couched. The assumption behind this stereotype is that people vote for populist parties because they articulate straightforward, undemanding and potent narratives that establish an intelligibly structured political universe. Previous research points to a correlation between political knowledge and pro-democratic attitudes grounded in an aversion to complexity. In their study of the “authoritarian personality”, Adorno et al. (Citation1950, 658–659) argued that “ignorance with respect to the complexities of contemporary society makes for a state of general uncertainty and anxiety, which is the ideal breeding ground for the modern type of reactionary mass movement”. A more recent study bears out the association of economic vulnerability with “declinist” feelings of alienation from contemporary society and its path of evolution, with these sentiments finding their most apt political expression in populism (Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2016, 15).

The associations between populism and a lack of political sophistication have formed the basis of one theoretical strand in the literature. Pierre Ostiguy (Citation2017, 78–80) argues that populism is a politics of the “low”, in which “coarse, uninhibited, culturally popular” forms of cultural expression contrast with the “well-behaved, stiff, polished” manners of the non-populists. These idioms are common both to the political entrepreneur, who appeals to populist voters in a manner consistent with their socio-cultural location, and to the voters themselves, for whom voting for populists is an act of identitarian expressiveness.

If adherence to the ideas behind populism is an expression of an unsophisticated political worldview, people with low levels of political knowledge – and the low socio-economic status associated with it – are more likely to espouse populist attitudes. Furthermore, if populist parties stoke fear and anger about the complexity of modern political life among those who are most vulnerable to its effects and simultaneously least well equipped to counter populist narratives, then uninformed populist voters should be these parties’ most promising electoral targets.

The informed populist

While the stereotype of the uninformed populist resonates with some theories and findings from the existing literature, rising levels of electoral support for populist parties in recent years throw this stereotype into question, given long-established findings about lower rates of electoral participation among people with low levels of education (Gallego Citation2015, 40). While there are many reasons for the upturn in populist fortunes, some of which concern supply-side and contextual factors rather than demand-side ones, it is hard in the face of recent developments to sustain the argument that support for populists is limited by lower rates of participation among the politically unsophisticated.

If differing rates of electoral participation place a ceiling on support for populist parties among the politically unsophisticated, and yet populists nevertheless continue to gain support, this raises two possibilities. One is that populists have become more successful in articulating appeals that mobilise hitherto inactive sections of the electorate. However, this supply-side argument is challenged on the demand side by the persistence of a secular trend of declining participation in elections across contemporary democracies (Coppedge et al. Citation2020). Instead, it seems more plausible that populists have been increasingly successful in capturing voters who are politically active but disenchanted with existing parties.

We therefore suggest an “informed populist” counterhypothesis to the “uninformed populist” stereotype, according to which populist attitudes can be both reflective of and supportive of a politically sophisticated critical approach to contemporary political realities. This hypothesis builds on the observation that populist attitudes constitute a “latent demand” which “must be activated by an appropriate context” (Hawkins and Kaltwasser Citation2019, 7). If previous iterations of populism were more crudely articulated at the supply side and appealed to those with a relatively unsophisticated understanding of politics, perhaps the increased electoral effectiveness of populist appeals reflects the greater sophistication with which they are articulated and the activation of latent populist attitudes among a broader and more politically knowledgeable stratum of the electorate.

This hypothesis finds some support in the literature on “dissatisfied democrats” (Klingemann Citation2014) and “critical citizens” (Dalton Citation2004; Norris Citation1999). This literature, which originates in Easton's (Citation1965, Citation1975) work on the distinction between principled support for democracy and dissatisfaction at its performance, posits the existence of a cohort of voters “who adhere strongly to democratic values but who find the existing structures of representative government … to be wanting” (Norris Citation1999, 3). The concept of the dissatisfied democrat implies the existence of politically active, motivated and knowledgeable citizens who are alienated not from democracy itself, but from mainstream political parties and the present political elite. Such citizens may be attracted to populists both for their anti-establishment rhetoric and for their intention to restore the “redemptive” face of democracy (Canovan Citation1999, 10); the original promise of the primacy of popular sovereignty over administrative government.

Recent insights from an emerging literature on “post-truth politics” and “fake news” reinforce the idea of a more nuanced relationship between knowledge and populism. Ylä-Anttila’s (Citation2018) analysis of the role of the “countermedia” in mobilising support for Finnish radical-right populist parties brings into question the dominant image of populism as an anti-intellectual rhetorical endeavour which focuses on simplistic, “common-sense” and folkish reasoning. Against this, he suggests that “counterknowledge, allegedly supported by alternative inquiry, is another salient strategy of questioning mainstream policies in a populist style” (Ylä-Anttila Citation2018, 2). A recent comparative study of the lexical complexity of populists’ rhetoric finds that there is no consistent correlation between populist messages and the linguistic register in which they are expressed. McDonnell and Ondelli (Citation2020) observe that while Donald Trump and Matteo Salvini generally use simpler language than their non-populist competitors, Marine Le Pen and Nigel Farage are actually less likely than non-populists to use simple language.

On the basis of these insights, we posit that informed populists combine high levels of political knowledge – and the high socio-economic status with which it is related – with populist attitudes, and that in concert these characteristics are predictive of voting for populist parties. It should be stressed that the informed populist hypothesis does not necessarily imply that the uninformed populist hypothesis is incorrect. The two may coincide at the same time within the same political system as discrete responses to more and less sophisticated forms of populist mobilisation. Rather, the notion of informed populism suggests that the link between populism, political knowledge, social status and voting behaviour is more complex than prevalent stereotypes suggest.

Hypotheses

The first set of hypotheses explore the relationships between our three main variables of interest. They are couched in terms of the uninformed populist thesis, but the results are also relevant to evaluating the credibility of the alternative informed populist proposition.

Political knowledge is negatively correlated with populist attitudes (H1).

Those who have low socio-economic status (SES) are more likely than those with high SES to hold populist attitudes (H2).

The coincidence of low SES and low political knowledge predicts higher levels of populist attitudes, while the coincidence of high SES and high political knowledge predicts lower levels of populist attitudes (H3).

The second set of hypotheses pertain to voting behaviour. Both uninformed and informed populism imply a particular configuration of relationships between political knowledge, SES, populism and voting behaviour. Yet if neither the uninformed nor informed populist hypotheses are borne out by our analysis, this may be explained by higher rates of abstention among those who are politically alienated, of low social status, and who lack the political interest that often goes together with political knowledge.

High levels of populism, low SES and low levels of political knowledge predict support for populist parties, and this relationship is strengthened by the interaction of these factors (H4).

High levels of populism, high SES and high levels of political knowledge predict support for populist parties, and this relationship is strengthened by the interaction of these factors (H5).

Low levels of political knowledge, low SES and high levels of populism predict non-voting, and this relationship is strengthened by the interaction of these factors (H6).

The 2015 Polish parliamentary election as a test case

If there is a relationship between populism and political knowledge which bears out one or the other of the theses put forward, or both, then we should expect to find evidence across a wide variety of cases. However, in the absence of cross-national data that would allow us to test these propositions comparatively, a single case can help confirm, disconfirm and refine the proposed theoretical claims for further concept development and comparative application.

The 2015 Polish parliamentary elections provide a credible test of these propositions. According to Stanley (Citation2018, 7) the distinction between populism and non-populism was central to political competition in these elections, a judgement amply reinforced by Poland's subsequent turn towards illiberalism and monism (Markowski Citation2018; Pech and Scheppele Citation2017; Sadurski Citation2019). In times of “ordinary politics”, populist ideas may not be consequential enough to exert an effect other than at the periphery of the political system. However, Poles were, and remain, divided not so much over policy options as over the very rules of the game (Bill and Stanley Citation2020). The prevailing political cleavage is defined not by the thick-ideological alternatives of policy platforms but by the thin-ideological distinction between a politics of liberal-democratic pluralism and one of populist monism. This makes Poland a good test case for exploring the posited relationships between populism and political knowledge: if these relationships are not evident in a context where populism is central to the choice set, then it is reasonable to doubt that they will hold in cases where populism is irrelevant at the supply side.

Populism has been an important feature of Polish party politics since 2001, when the party system shifted from a “post-communist divide” between former communist regime elites and Solidarity dissidents (Grabowska Citation2004) to a “transition divide” between parties that supported the liberal-democratic settlement that had emerged after 1989 and parties that contested the norms and institutions of that system and questioned the legitimacy of the elites that had founded those institutions.

This divide found initial expression during the truncated 2005–2007 parliamentary term in a short-lived but consequential “populist coalition” led by the conservative and nativist Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) party, with the agrarian populist Self-Defence (Samoobrona Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, SRP) and the radical right-wing populist League of Polish Families (Liga Polskich Rodzin, LPR) as minor partners. During the eight-year term of the subsequent coalition formed by the centrist Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO) and the agrarian Polish Peasant Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, PSL), the main line of competition in Polish politics definitively realigned. With PO the cautious and consensus-oriented defenders of the status quo, PiS embraced their former coalition partners’ role as the force of disputatious revolutionism. The flourishing of conspiracy theory rhetoric following the 2010 Smoleńsk air disaster, in which co-founder of PiS President Lech Kaczyński was killed, helped to radicalise PiS's diagnoses of the pathological incapacity of the Polish state.

By the time of the 2015 parliamentary election, populism had become central to Polish politics. PiS's political appeal linked arguments about the inauthenticity and illegitimacy of Polish elites to a set of cultural attitudes embracing traditionalism, nativism, and a scepticism towards supranational integration, allied with a market-sceptic and interventionist set of positions on economic policy. In this, they were joined by a new force, the Kukiz Movement (Kukiz’15, K’15), whose professed ideological amorphousness belied a clear attachment to the nationalist right, and which concentrated above all on a populist attack on established parties, PiS included, which it portrayed as a cartel remote from the needs of ordinary Poles.

As the most enduring representative of the transition elite, and as a formation that pursued as an ideal a depoliticised and consensualist politics of administration (the “warm water in the tap” approach, as it was dubbed), PO's liberal centrism stood in opposition to the populist radicalism of its opponents. In this it was joined by the liberal Modern Party (Nowoczesna,.N), another new party which was critical of PO's cautious governing style but remained committed to liberal-democratic institutions and norms.

At the demand side, there is evidence that populism played an important role in shaping choices at this election in ways consistent with the supply-side divide. Stanley (Citation2018, 24) finds that populist attitudes worked in tandem with cultural attitudes to structure voters’ sentiments toward parties on both sides of this divide, with low levels of populism and cultural liberalism predicting more positive sentiments toward PO and N, and high levels of populism and low levels of cultural liberalism predicting more positive sentiments toward PiS and K’15. Furthermore, populist attitudes raised the probability of voting for PiS, and lowered the probability of voting for PO.

These findings are important to the current article in two senses. First, they show that populist attitudes have a meaningful impact on vote choice in Poland. Secondly, they tell us something potentially important about the relationship of populist attitudes and our other key variables. If the initial populist breakthrough in 2001 was the preserve of two parties, SO and LPR, which appealed primarily to those of low social status – the “transition losers’ of so-called “Poland B” – PiS's victory in 2015 drew on a much broader cross-section of society. As Szczerbiak (Citation2016, 414) observes, in 2015 PiS “won the largest share of the vote in virtually every demographic group, including those that had previously been Civic Platform bastions of support”. If populist attitudes were widespread and politically efficacious at the 2015 election, the broadening of PiS support to the high SES constituencies previously dominated by PO suggests a shift towards informed populism.

Data and methods

To answer our research questions, we use data from the 2015 Polish National Election Study (Centre for the Study of Democracy Citation2015). The PNES, which has been conducted at every election since 1997, is the foremost Polish post-election survey and adheres to international standards for the collection of comparative data. The 2015 edition of the PNES was based on a nationally representative sample of 1733 adult citizens.

Operational definitions

The three key variables in this analysis are political knowledge, populism, and PES. Political knowledge is operationalised as a latent variable, using thirteen questions tapping different aspects of awareness about political institutions, issue ownership, and prior political actions (see for details of question wording and answers). While these variables do not cover each of the domains of politically useful knowledge as comprehensively as we would like, they cover issues of political community, procedural issues, rules and institutions related to the functioning of the state, the prior performance and actions of political parties, and parties’ stances on key policies relevant to the 2015 election.

Table 1. Political knowledge questions.

Each of these questions was recoded into a three-category nominal variable according to whether the respondent gave the correct answer, the wrong answer, or – whether through indecision or unwillingness – did not give an answer. This recoding was motivated by the nature of the data: in several cases, only a small proportion of respondents gave incorrect answers, but many respondents did not know or refused to answer.

We then fitted a nominal response IRT model to the 13 questions (Raykov and Marcoulides Citation2018, 189–198). This technique evaluates the relationship between the probability of a particular response to a question and an underlying latent construct, in this case political knowledge. After estimating this model, we predicted the value of the political knowledge trait for each respondent and rescaled the resulting variable to a 0–1 range to aid interpretation in subsequent analyses. The resulting variable is normally distributed, with a mean of 0.55.

For our measure of populism, we replicated Stanley’s (Citation2018) seven-item scale variable taken from the PNES dataset, again standardised to a 0–1 range. The question wordings and descriptive statistics can be found in . Polychoric factor analysis of these variables shows that they form a single factor accounting for 36 percent of the variance, with an ordinal alpha of 0.79 (following the procedure described in Gadermann, Guhn, and Zumbo (Citation2012)). The resulting variable is negatively skewed, with a mean of 0.63.

Table 2. Populism questions.

The socio-economic status variable was generated using three variables from the PNES dataset which measure distinct aspects of socio-economic status: level of education (recoded into four categories: “Basic or none”; “Basic vocational”; “Secondary”; and “Higher”); household income (recoded into quintiles); and occupational status (recoded into four categories: “Blue collar or clerical”; “Socio-cultural professionals”; “Managers and professionals”; and “Outside the labour market”. Since the education and occupational status variables are nominal, a latent class analysis was performed using the R package “depmixS4′ (Visser and Speenbrink Citation2010). This identified three classes corresponding to “low”, “medium” and “high” levels of SES, and calculated the probability that respondents would belong to each of these classes. Respondents were then assigned to the category of low SES, medium SES or high SES depending on their optimal state: that is, the class they are most likely to belong to given their probability of belonging to each of the three (Rabiner Citation1990, 263–264).

The vote choice variable recodes a variable on individual party choice into a five-category variable that distinguishes various party types. The category of “right” is populated by those voting for PiS, Kukiz’15 or the minor party KORWiN, and consists of the parties on the “populist” side of Poland's ideological divide. The category of “liberal” contains those who voted for PO or N. The category “left” contains those who voted for the centre-left electoral coalition United Left (Zjednoczona Lewica, ZL) or the new left Together (Razem). The category “other” denotes those who voted for PSL. The category “Did not vote” is self-explanatory.

There are a number of variables included to control for factors known to be predictive of vote choice. These are gender, age, size of region in which respondent lives, party identification and left-right self-identification.

Methods of analysis

Our analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we address the three hypotheses which concern the stereotype of the uninformed populist and the implied counterhypotheses about informed populists (H1-H3). In this case, the dependent variable is our measure of populism, which we regress on political knowledge, SES and the control variables. The first model contains the political knowledge and SES variables. The second model adds an interaction of these two variables. The third model then includes control variables. This enables us to evaluate the extent to which political knowledge predicts populist attitudes both in general and when stratified by socio-economic status.

In the second step, we address our hypotheses about vote choice (H4-H6), using a multinomial regression model to regress our vote choice variable on populist attitudes, political knowledge and SES, again including control variables. The first model contains only controls. In the second model, we introduce our populism and political knowledge variables; in the third model, SES; in the fourth model, an interaction of populism and political knowledge, and in the fifth model a three-way interaction of populism, political knowledge and SES. This analysis allows us to evaluate the extent to which our three key variables of populism, political knowledge and SES are associated with voting for populist parties both independently and in tandem.

All models were estimated in R (R. Core Team Citation2020) using Bayesian regression with weakly informative normal (0,1) priors on all independent variables to stabilise estimates and exclude unreasonable parameter values. The brms package was used for this analysis (Bürkner Citation2017) An analysis of missing data revealed that only 56.2% of cases (975 respondents) gave a response to all questions, so analysis was conducted on 10 multiply-imputed datasets using the mice package (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Citation2011). Posterior predictive checks indicated that the models were well fitted to the data. Following analysis, quantities of interest were estimated using the tidybayes package (Kay Citation2020).

Analysis

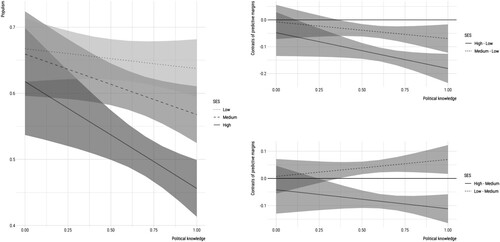

The results of the first analysis, in which populism is the dependent variable, are presented in . Model 1 includes the two key variables of interest, political knowledge and SES, and explains around 13% of variance. Adding an interaction of these two variables does not appreciably increase the amount of variance explained. In Model 3, which includes control variables, variance explained rises slightly to just under 17%.

Table 3. Regression of populism on political knowledge and socio-economic status.

confirms that there is a negative relationship between levels of populism and political knowledge, and also that this relationship is conditioned by socio-economic status. Among those with low SES, political knowledge has only a moderately negative relationship with populism, with the level of populism decreasing from 0.67 among those with low levels of political knowledge to 0.64 among those with high levels of political knowledge. Where those with medium SES are concerned, there is a more substantial decrease, from 0.66–0.57. Among those with high SES, the level of populism is lower to begin with, and declines sharply from 0.62 among those with low levels of political knowledge to 0.46 among those with high levels of political knowledge.

The role of SES in mediating the relationship between populism and political knowledge is also evident from the contrasts of predictive margins plotted on the right-hand side of . The slope for medium levels of SES is significantly different from the slope for low levels of SES where political knowledge is approximately 0.35 or higher, while the slope for high levels of SES is significantly different from the slope for low levels of SES at values of 0.12 or higher. Furthermore, the slope for high levels of SES is significantly different from the slope for medium levels of SES where political knowledge is around 0.30 or higher.

The results of the second analysis, in which vote choice is the dependent variable, are presented in , which shows the table of coefficients from the full multinomial regression model. For reasons of space and relevance, only the full model – including all controls as well as substantive variables – is tabulated. Since the coefficients derived from multinomial logistic regression models relate to a base category (in this case, those who voted for liberal parties), it is necessary to plot specific quantities of interest to understand the relationships between key variables, as the significance of tabulated coefficients (or their absence) does not always indicate that an independent variable is insignificant with respect to a particular value of the dependent variable. This is particularly important when examining interactions, which may not always be statistically significant across the entire range of the variables in question.

Table 4. Regression of vote choice on populism, political knowledge and socio-economic status.

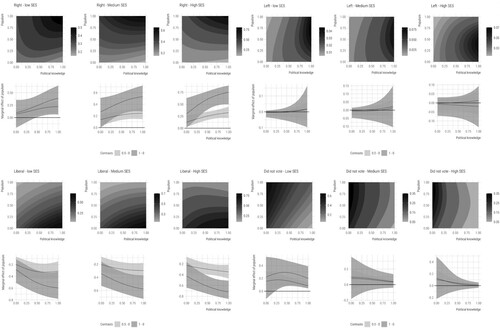

The three-way interaction of political knowledge, populism and SES and the relationship of these variables with vote choice can most easily be visualised via the contour plots in . These plots use shaded areas to represent the probability of making a specific vote choice at given levels of populism and political knowledge. If these two variables do not have an interacting effect on vote choice, the contours of this plot consist of straight lines. However, while contour plots provide a clear picture of the interaction, they do not show whether it is statistically significant. Below each contour plot in is a plot of the marginal effect of populism on vote choice across all levels of political knowledge for a given level of SES, with the lowest level of populism as the baseline for comparison, and the points of comparison a medium level of populism (0.5) and a high level of populism (1). Where the marginal effect of populism is statistically distinguishable from zero, we can conclude that there is a significant difference.

Figure 2. Interactive effects of populism, political knowledge and socio-economic status on vote choice

To begin with right-wing parties, the contour plots suggest that there is an interactive effect of populism and political knowledge in each case. The contours darken toward the top right of the plot, indicating that respondents with high levels of populism and political knowledge are more likely to vote for parties of the right than those with high populism but low political knowledge, those with low populism but high political knowledge, or those with low levels of both. The contrast plots suggest that this effect is more pronounced as levels of SES increase. Among those with low SES, the interactive impact of populism and political knowledge becomes statistically significant where levels of political knowledge are 0.50 or greater. Among those with medium or high SES, the interaction is significant across all values of political knowledge. For example, a high SES voter with low levels of political knowledge and a high level of populism has approximately a 0.26 greater probability of voting for a party of the right than a voter with low political knowledge and a low level of populism. A high SES voter with a high level of populism and a high level of political knowledge has a 0.75 greater probability of voting for a party of the right than someone with high SES and high political knowledge but a low level of populism. In summary, higher populist attitudes and higher levels of political knowledge increase the probability of voting for right-wing parties, particularly among those with high SES.

This finding contrasts sharply with the case of liberal parties. Here, the contour plots darken toward the bottom right of the plot, indicating that the probability of voting for liberal parties increases as political knowledge increases, but that this relationship is mediated by the level of populism. At all levels of SES, a voter with low populism and high political knowledge has around a 0.70 probability of voting for liberal parties. As the contrast plots show, the negative relationship between populism and voting for liberal parties is strengthened as political knowledge increases. In the case of a voter with low levels of political knowledge, having a high level of populism decreases the probability of voting for a liberal party by around 0.30–0.40 compared with a voter who has a low level of populism, depending on the level of SES. However, among those with a high level of political knowledge, being strongly populist has a much greater effect: among those with low and medium SES the probability of voting for liberal parties decreases by 0.60, and in the case of those with high SES it decreases by over 0.70.

On the other hand, voting for parties of the left is not strongly affected by populism, although political knowledge remains a relevant predictor. As the contour plots show, the probability of voting for a party of the left increases as political knowledge increases. However, the contrast plots show that increasing the level of populism makes no statistically significant difference to the probability of voting for a party of the left, regardless of a voter's level of political knowledge.

Where non-voting is concerned, we also see that the impact of political knowledge is largely unmediated by populism. The lower a respondent's level of political knowledge, the more likely they are not to have voted. Among those with medium or high SES, increasing the level of populism makes no statistically significant difference to the probability of electoral abstention, regardless of the level of political knowledge. Among those with low SES, medium and high levels of populism increase the probability of abstaining relative to low levels of populism. The effect of populism declines slightly as levels of political knowledge increase, but this is only a moderate change.

Discussion

The findings of our analyses do not refute the stereotype of the uninformed populist, but show that the relationship between populism, political knowledge and social status is more complex than this stereotype suggests. In the Polish case, there is clear evidence that parties of the right have been able to mobilise voters with populist attitudes regardless of their level of political knowledge, and that much of their support is drawn from politically well informed and socio-economically secure members of society who hold populist views.

At first glance, this outcome seems counterintuitive when we consider the findings from the first analysis, which looks at the relationships between populism, political knowledge and socio-economic status. These, if anything, would seem to support the stereotype of populism as an ideology that appeals to those who are less politically sophisticated. We find that political knowledge is negatively correlated with populist attitudes (H1), and that those who have low SES are more likely than those who have high SES to have populist attitudes (H2). We do not find that the coincidence of low SES and low political knowledge predicts higher levels of populist attitudes; those with medium SES are just as likely as those with low SES to have high levels of populism if they have low levels of political knowledge. Nevertheless, we do find support for the hypothesis that the coincidence of high SES and high political knowledge predicts lower levels of populist attitudes than among those with low or medium SES (H3).

However, when we look at how this confluence of attitudes and attributes translates into voting behaviour, a different picture emerges. On the one hand, those with populist attitudes are more likely to have lower levels of political knowledge and be lower on the social ladder than those with anti-populist attitudes. Yet there is also a significant electoral cohort of informed populists with higher levels of political knowledge and the higher socio-economic status often associated with it.

As the second analysis shows, parties of the populist right mobilise informed populists to a greater extent than they do their uninformed counterparts. Contrary to H4, we do not find that high levels of populism, low SES and low levels of political knowledge predict support for populists and that this relationship is strengthened by the interaction of these factors (H4). Instead, we find, in line with H5, that high levels of populism combine with high SES and high levels of political knowledge to predict support for these parties. Finally, there is limited evidence that the combination of low political knowledge, low SES and high populism predicts non-voting (H6). While those with low levels of political knowledge are less likely to vote than those with higher levels of political knowledge, and those with low SES are less likely to vote than those with high SES, populism does not interact with these variables in the predicted fashion. If the uninformed are more likely to abstain than their informed counterparts, their populist views have little bearing on this decision.

Conclusions

This article has found significant support for the counterhypothesis of the informed populist. On the one hand, the significant negative association between levels of political knowledge and levels of populism, and the low socio-economic status with which low levels of knowledge are associated, is also associated with high levels of populism. This fits the cliche of the uninformed inhabitant of provincial Poland who, if he votes at all, votes for populists.

However, while the expected relationship between populism and political knowledge holds among the electorate as a whole, it does not drive voting behaviour in terms of choices between parties. While the uninformed and those lower on the social ladder may vote for populists, they are more likely not to vote at all, and populism plays no significant part in determining this. Instead, we find a clear divide between a set of parties on the right which attract the support of those who are politically informed and populist in their attitudes, and a set of liberal parties which attract the support of those who are politically informed and anti-populist in their views. This divide is particularly pronounced among those of high socio-economic status, and such citizens are more likely to vote anyway.

It is possible that the particular circumstances of the 2015 parliamentary election in Poland, in which a populist party made significant incursions on the electoral stronghold of a non-populist party, gives a clearer picture of the mobilisation of informed populists than might otherwise be the case, and that the phenomenon of uninformed populist voting is more commonly borne out in practice. However, irrespective of which of these outcomes is the more common, these two claims should in any case not be seen as mutually exclusive. Rather, our results are in line with literature which holds that populism is a normal feature of contemporary democratic politics, rather than a pathological outburst of irrational and volatile masses (Mudde Citation2010). Both the uninformed and the informed may end up supporting populists; the key is to understand how they are mobilised to do so. Future comparative research can build on the insights of this case study to establish whether, and to what extent, the relationships identified in this article hold more widely, and with what consequences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ben Stanley

Ben Stanley is Associate Professor at the Centre for the Study of Democracy, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw.

Mikołaj Cześnik

Mikołaj Cześnik is Associate Professor and Director of the Institute of Social Sciences, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw.

References

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and R. Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality.The Authoritarian Personality. Oxford, England: Harpers.

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove. 2014. “How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (9): 1324–1353.

- Andreadis, Ioannis, Kirk A. Hawkins, Ivan Llamazares, and Matthew M. Singer. 2019. “Conditional Populist Voting in Chile, Greece, Spain, and Bolivia.” In The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis, edited by Kirk A. Hawkins, Ryan E. Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, 238–278. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bill, Stanley, and Ben Stanley. 2020. “Whose Poland is it to be? PiS and the Struggle Between Monism and Pluralism.” East European Politics 36 (3): 1–17.

- Bischof, Daniel, and Roman Senninger. 2018. “Simple Politics for the People? Complexity in Campaign Messages and Political Knowledge.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 473–495.

- Bos, Linda, Wouter van der Brug, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2013. “An Experimental Test of the Impact of Style and Rhetoric on the Perception of Right-Wing Populist and Mainstream Party Leaders.” Acta Politica 48 (2): 192–208.

- Buuren, Stef van, and Karin Groothuis-Oudshoorn. 2011. “mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R.” Journal of Statistical Software 45 (3): 1–67.

- Bürkner, Paul-Christian. 2017. “brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan.” Journal of Statistical Software 80 (1): 1–28.

- Canovan, Margaret. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47 (1): 2–16.

- Centre for the Study of Democracy. 2015. “Polish National Election Study (PGSW) 2015.” Unpublished dataset.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. 2020. “V-Dem Country-Year Dataset v10.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. doi:https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Core Team, R. 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Dalton, Russell J. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: the Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Drehle, David Von. 2019. “Opinion Populists are popular because they give easy answers to problems that don’t have them.” Washington Post, 2019/10/12, 2019. Accessed 2020/09/10/07:12:25. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/populists-are-popular-because-they-give-easy-answers-to-problems-that-dont-have-them/2019/10/11/73dac4c8-ec47-11e9-85c0-85a098e47b37_story.html.

- Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley.

- Easton, David. 1975. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457.

- Elchardus, Mark, and Bram Spruyt. 2016. “Populism, Persistent Republicanism and Declinism: An Empirical Analysis of Populism as a Thin Ideology.” Government and Opposition 51 (1): 111–133.

- Gadermann, Anne M., Martin Guhn, and Bruno D. Zumbo. 2012. “Estimating Ordinal Reliability for Likert-Type and Ordinal Item Response Data: A Conceptual, Empirical, and Practical Guide.” Practical Assessment, Research Evaluation 17 (3): 1–13.

- Gallego, Aina. 2015. Unequal Political Participation Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grabowska, Mirosława. 2004. Podział Postkomunistyczny: Społeczne Podstawy Polityki w Polsce po 1989 Roku. Warszawa: Scholar.

- Hameleers, Michael, Linda Bos, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2016. ““They Did It”: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication.” Communication Research 44 (6): 870–900.

- Hawkins, Kirk, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2019. “Introduction: the Ideational Approach.” In The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis, edited by Kirk Hawkins, Ryan E. Carlin, Levente Littvay, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, 1–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kay, Matthew. 2020. tidybayes: Tidy Data and Geoms for Bayesian Models.

- Kayam, Orly. 2018. “The Readability and Simplicity of Donald Trump’s Language.” Political Studies Review 16 (1): 73–88.

- Klingemann, Hans-Dieter. 2014. “Dissatisfied Democrats: Democratic Maturation in Old and New Democracies.” In The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens, edited by Russell J. Dalton, and Christian Welzel, 116–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Markowski, Radoslaw. 2018. “Creating Authoritarian Clientelism: Poland After 2015.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 11: 111–132.

- McDonnell, Duncan, and Stefano Ondelli. 2020. “The Language of Right-Wing Populist Leaders: Not So Simple.” Perspectives on Politics.

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563.

- Mudde, Cas. 2010. “The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy.” West European Politics 33 (6): 1167–1186.

- Norris, Pippa. 1999. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. edited by Pippa Norris: Oxford University Press.

- Oliver, J. Eric, and Wendy M. Rahn. 2016. “Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 Election.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667 (1): 189–206.

- Ostiguy, Pierre. 2017. “Populism: A Socio-Cultural Approach.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, 73–97. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pech, Laurent, and Kim Lane Scheppele. 2017. “Illiberalism Within: Rule of Law Backsliding in the EU.” Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 19: 3–47.

- Rabiner, Lawrence R. 1990. “A Tutorial on Hidden Markov Models and Selected Applications in Speech Recognition.” In Readings in Speech Recognition, edited by Alex Waibel, and Kai-Fu Lee, 267–296. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Raykov, Tenko, and George Marcoulides. 2018. A Course in Item Response Theory Modeling with Stata. College Station: Stata Press.

- Sadurski, Wojciech. 2019. Poland‘s Constitutional Breakdown. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stanley, Ben. 2008. “The Thin Ideology of Populism.” Journal of Political Ideologies 13 (1): 95–110.

- Stanley, Ben. 2018. “A New Populist Divide? Correspondences of Supply and Demand in the 2015 Polish Parliamentary Elections.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (1): 17–43.

- Szczerbiak, Aleks. 2016. “An Anti-Establishment Backlash That Shook up the Party System? The October 2015 Polish Parliamentary Election.” European Politics and Society 18 (4): 404–427.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn Van Kessel. 2018. “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (1): 68–92.

- Visser, Ingmar, and Maarten Speenbrink. 2010. “depmixS4: An R Package for Hidden Markov Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 36 (7): 1–21.

- Ylä-Anttila, Tuukka. 2018. “Populist Knowledge: ‘Post-Truth’ Repertoires of Contesting Epistemic Authorities.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 5 (4): 356–388.