ABSTRACT

Prime Ministers (PMs) in Central and Eastern Europe have been relatively weak, although substantial variation in the survival both within and across countries exists. In Bulgaria, Boyko Borissov came to power in 2009 in most unfavourable situation: leader of a new party, he faced minority situation in parliament and had to cope with an ideologically heterogeneous coalition. Still, Borissov has become the longest serving PM in the country. This article examines the cabinet governance of Borissov I, II and III explores the PM's relationship with other parties inside and outside parliament as well as the mechanisms of cabinet management.

Introduction

That Prime Ministers (PMs) in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) have been relatively weak has emerged as a norm in the literature (Baylis Citation2007). Short tenure durations, unstable relations with the parliaments and tense balance of power with the heads of state are among the typical characteristics of PMs in the post-communist context. Their survival in chief executive office has generally been under the averages of their West European counterparts (Mueller-Rommel Citation2005). However, there is also substantial variation in prime-ministerial duration in CEE “both within and across individual countries” (Grotz and Weber Citation2017, 231). A plethora of “contextual, individual and institutional” factors might impact the longevity of the PMs, just as anywhere else in the world (Strangio et al. Citation2013, 5), such as their individual leadership potential, the nature of their relationship with the parliamentary parties and the political ambitions of the head of state. Further, if PMs are propelled into power by new parties, their tenure in office might become even more fraught with insecurity and uncertainty as new parties in government are particularly prone to lose votes, undergo ideological and leadership challenges, and identity change (Deschouwer Citation2008, 5).

In Bulgaria, Boyko Borissov accessed the PM office after his party, GERB, won the 2009 parliamentary elections as a newcomer to the national political scene. In the meantime, he has become the longest serving PM in the country having had three separate post-electoral cabinets. In many ways, he has succeeded to do so against all odds. In his first term, Borissov became PM as chairman of a new party built for the most part around his personality. His first two cabinets were minority governments that were reliant on the support of ideologically divergent parliamentary parties. Still, during both periods Borissov has managed to call the shots of all his political games and return as the winner time after time, including a third term that started in 2017 and is still ongoing. Footnote1 As a result, in the course of ten years he built a massive party machine that has come to dominate the Bulgarian political system, where electoral volatility is quite high and party discipline a rare phenomenon.

This political context makes Borissov’s survival in PM office an even more interesting case. Our article will use insights from the literature on new parties in government, executive power in post-communist Europe as well as the literature on prime-ministerial survival and coalition theory to examine Borissov I (2009–2013), Borissov II (2014–2016), and the early years of Borissov III (2017–2019). Using secondary sources, we will demonstrate how Borissov succeeded to maintain the chief executive office by looking at two main dimensions: his relationship with other parties inside and outside the parliament as well as the mechanisms of cabinet management.Footnote2

Challenges of PM survival in the CEE context

There are several theoretical considerations regarding the ability of PM Borissov, as chair of a new party in a post-communist context, to maintain a stable position vis-à-vis the parliamentary setting and other institutions in the political system.

PMs accessing the chief executive office from within new parties experience specific challenges presented by the newness of the party they represent. Parties that enter the electoral process for the first time can be either genuinely new or splinters from existing ones. Of particular relevance are the genuinely new parties (GNPs) defined as “parties that are not successors to any previous parliamentary parties, have a novel name and structure, and do not have any important figures from past democratic politics among their major members” (Sikk Citation2005, 399). Such GNPs are inexperienced in dealing with internal developments such as leadership changes, ideological fluidity, and organisational problems (Deschouwer Citation2008, 2). All these dimensions make them face, if they come into power, specific challenges of governing.

PMs who come from such parties share these challenges. GNPs embarking on a governing tenure tend to experience challenges to their leadership, identity, and vote base (Deschouwer Citation2008, 4). Most fundamentally, when gaining enough parliamentary seats to be in cabinet, they come to replace their vote-seeking ambitions with office-seeking ones (Buelens and Hino Citation2008, 157–175). Such a change impacts and challenges the party in all its functions. A GNP participating in government needs to fill political offices – and faces particular challenges in doing this.

To begin with, it needs to find enough suitable and reliable appointees to support it in various offices of the state. GNPs might experience difficulties in recruiting such people in large enough numbers. In addition, the distribution of offices might lead to elite conflicts, further destabilising the party (Deschouwer Citation2008, 4–5; Bolleyer Citation2008, 32–33). Further, in transitioning from the parliamentary opposition or from an extra-parliamentary protest position to a governing party, the GNP undergoes significant identity change. It will need to compromise to maintain its position – whether governing alone or in coalition – and this will certainly lead to vote loss particularly as incumbency begins to weigh in (Bolleyer Citation2008, 30–31).

In addition, the survival of PMs as “primus inter pares” reflects the ability of the cabinet as such to remain in office. Consequently, cabinet duration is affected by various conditions (Müller, Bergman, and Ilonszki Citation2019). Structural attributes of the cabinet itself such as its majority status or the ideologically compatibility of coalition partners can prolong its life while the opposite will shorten its tenure (Müller, Bergman, and Ilonszki Citation2019, 17–18). Institutional conditions will further constrain the chances of a cabinet to remain in power: the presence of investiture vote might lengthen it, while strong and unified opposition might shorten it (Laver and Schofield Citation1990, 147–158). Last, critical events, such as death of a leader, war involvement, and economic crises but also civil protests and natural disasters, can be the “force” that brings party governments down (Browne, Frendreis, and Gleiber Citation1984, 179).

The ability of PMs in CEE to survive in office is also impacted by the specific realities of the post-communist context. As Blondel and Müller-Rommel (Citation2001, 10–12) and Grotz and Weber (Citation2012) have argued, both external tensions – such as institutional demarcation between government and opposition – and internal tensions – such as the politicisation of the bureaucracy and the heritage of the communist patronage system – create a particularly challenging situation. Unpredictability, inefficiently and increased dependence on the dynamics of the (unstable) party system have characterised post-communist governments (Grotz and Weber Citation2012; Blondel and Müller-Rommel Citation2001, 13). In such less predictable environment (Baylis Citation2007), the specific features of the PM and their relationships with the other parties, and institutional set-up come to play an extremely important role for the longevity of the PM (Grotz and Kukec in this issue). Support by their own party is fundamental to PMs in post-electoral situations, while the presence of a strong president is often detrimental to the ability of PM’s to remain in power long.

In addition to these structural features that are likely to impact the longevity of a PM, there are also several individual factors that, research has shown, make for more or less durable political leaders (Dowding Citation2013). Literature on the leadership capital index, for example, distinguishes between political capital and leadership capital and argue that this is the latter, composed of individual skills, relations and reputation that provides a useful analytical tool to study political leadership comparatively (Bennister et al. Citation2015, 434). This index they come up to measure leadership capital has been used to assess the strength of numerous executive leaders and explain certain patterns of executive durability (such as Helms Citation2016 on German chancellors and Burrett Citation2016 on Japanese PMs). For the present purposes, we focus on the more structural determinants of the durability of prime ministers, while arguably some of the discussion also touched upon the personal style of PM Borissov and the interplay of these individual and structural characteristics.Footnote3 Abilit

Theoretically, a PM coming to power for the first time, from within a new party, with a minority cabinet, within a somewhat under-institutionalised party system and a fluid institutional setting, would be faced with a tough job to maintain her cabinet and herself in power. Such situations, we argue, are likely to put an even greater burden on these men and women because of the unpredictability and instability of political behaviour within post-communist political systems. PMs within such situations are likely to keep shorter reigns on their cabinets, and remain, even more than in ordinary situations, the focal points for dealing with the challenges of governing such as appointing people to public office, maintaining the links to their vote base and securing internal party stability.

Within the context of these expected challenges, Boyko Borissov was unlikely to succeed in maintaining cabinet stability and surviving in power. Leader of a GNP, heading a minority cabinet and faced with heterogeneous opposition and unpredictable party support in parliament (Grotz and Weber Citation2016, 452), he should have had a short tenure in chief executive office and disappeared into political irrelevance, just as his political mentor Saxecoburggotski did. Borissov was the first PM since Dimitrov in 1991 to be faced with a minority situation in parliament. His second cabinet was even a more interesting case as it was composed of a four-party coalition that still fell short of having a majority status. Minority government entails continuous bargaining and leads to potentially lack of commitment and motivation to negotiate alternative coalitions and might lead to shorter PM durations (Somer-Topcu and Williams Citation2008, 317). Further, Borissov was also faced with quite ideologically diverse supporting parties, and tough situations in parliament.

In that respect, his ability to return ever more powerful to the position of the PM in 2014 and 2017 made him an unexpected game-changer in Bulgarian politics. If we use office duration as indication of political success, Borissov is clearly the most successful Bulgarian PM. As illustrates the average prime-ministerial duration in post-communist Bulgaria is 942 days.Footnote4 In this context, Borissov has enjoyed more than 3,043 days (as of December 31, 2019) as leader of three separate cabinets. More importantly, however, he is the only PM in the country to come back twice after his initial tenure.

Table 1. Prime ministers and party governments in Bulgaria (1991–2019).

The rest of this article, will analyse the behaviour of PM Borissov across his first two cabinet tenures (2009–2013 and 2014–2017) and the initial two years of his third one (2017–2019) to explore the mechanisms and strategies he used to cope with the challenges posed to him in chief executive office. We will do so along two dimensions identified as key challenges to PMs from new parties: the ability to staff governmental position with personnel, and to maintain support for their cabinets in parliament.

Borissov in the context of Bulgarian politics

The assessment of Boyko Borissov’s survival as PM and the impact of his prime-ministerial tenures on Bulgarian politics requires some discussion of the context within which he emerged.

The first decade of Bulgaria’s post-1989 democratic development was dominated by the successor party of the communist regime – the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) – and the main opposition party – the Union of Democratic Forces (SDS). As illustrates, the cabinets of this decade were, with one exception, composed by either of these parties and their chairmen served as PMs. In 2001, this pattern of bipolar alternation was shattered when Simeon Saxecoburggotski, the last reigning tsar (king) of Bulgaria,Footnote5 returned to politics as party leader and head of a coalition cabinet between 2001 and 2005 (Karasimeonov Citation2010). As democratically appointed PM, however, he governed in what has been characterised as a Messiah role, promising to “save” the people from the oligarchy and from the eleven-year “bipolarity”.Footnote6

Saxecoburggotski established a party, which was, as its name suggests, built around his own personality. National Movement Simeon the Second (NDSV) proclaimed a platform focused on economic and financial issues, while its leader repeatedly advocated the abandonment of partisanship and unification around “historical ideas and values” (Harper Citation2003, 336). When Saxecoburggotski assumed the post of PM, he was faced with a complete lack of organisational structures and party machine on which to draw people to his cabinet. This was clearly evident in his choice of high-level officials, in which he relied more on personal connections and friends than on party mechanisms.

One of these personnel decisions became crucial for the political development of Bulgaria. PM Saxecoburggotski appointed a somewhat unknown man, Boyko Borissov, as a Chief Secretary of the Ministry of Interior, opening up an ever growing career path for him. What brought him a massive support later was quite the opposite of the incumbent PM: his macho looks and fitting manner of talking. Borissov’s eclectic image mixed several roles: firefighter, academic and personal bodyguard of the ex-communist leader Todor Zhivkov. Similarly to Saxecoburggotski, Borissov was perceived as a tough on crime savior, bringing order in the overly distorted political and social situation in the country. In 2005, as the NDSV fortunes were declining, he ran for mayor of Sofia and won the election as an independent, but with the support of NDSV. By August 2009, in his first month as PM, Borissov had a 60% approval rating, arguably the highest value for a PM in that period (Mediapool Citation2011).

Borissov I: a new party within a minority cabinet

How did PM Borissov deal with the challenges presented by GERB being new to the national political arena? To begin with, he pre-empted some of the typical challenges by quickly building an extensive and strong party organisation and allowing it to gain political experience by running in the European elections before joining the national political arena. Citizens for a European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) had been founded in December 2006 and built, very similarly to NDSV, around the personality of Borissov, then mayor of Sofia. GERB declared itself to be a center-right party presenting a “new rightist treaty” to the Bulgarian people based on three fundamental values: “economic freedom,” “competition in an environment of clear responsibilities and rules,” and “minimum state participation” (GERB Citation2008). In addition, the treaty advocated a strong role for the EU in guiding Bulgaria’s development, and called for transparency and accountability in managing the EU funds in the country. The party quickly joined the political competition – it participated in the European elections in May 2007 and came out as the plurality winner and similarly competed and won in a lot of the local elections in October 2007. Hence, by 2009 parliamentary elections, GERB was ready to compete in the national elections. National candidate lists were composed of people with experience in local politics and the party built an extensive party organisation, which at that moment already boasted 22,000 members (Kostadinova Citation2017). In contrast, NDSV had about 19,000 at the very peak of its government in 2003 (Spirova Citation2007, 128). While these developments did not pre-empt the party from experiencing the challenges of GNPs in governing entirely, it certainly alleviated some of them.

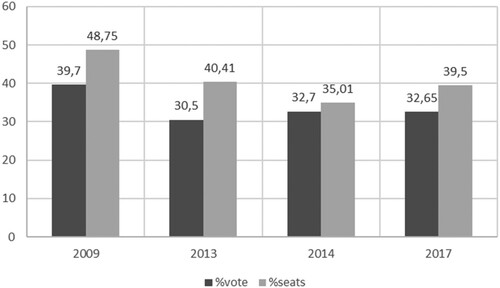

As newcomer to the national legislative arena, GERB clearly won the 2009 elections with 38.9% of the vote and 48.7% of the seats, barely failing to get a parliament majority (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2010).Footnote7 Negotiations for the future cabinet started prior to the elections, but took a different turn after them. GERB and the Blue Coalition (SK), an alliance of several center-right parties, successors of SDS that had governed the country during 1997–2001 (Kostov cabinet in ), were natural allies as partners in the European Peoples’ Party. The two entered into negotiations before the elections, expecting a strong performance by GERB, and for a couple of weeks, it seemed like a center-right coalition would come into government. However, once it became clear that GERB was the winner of the election, it decided against a coalition government. Instead, the party formed a single-party minority cabinet, asking three other parties that were on the right side of the spectrum – the Blue Coalition, the Law, Order and Justice (RZS) and Ataka – to sign an agreement promising their parliamentary support. GERB thus hoped to assume sole responsibility for a successful government policy, enjoying a comfortable majority in parliament at the same time (as the center-right parties controlled more than two thirds of the seats). While GERB offered the written agreement to the three parties, only Ataka signed it, leaving the cabinet in an official minority situation, as its actual parliamentary support continued to be mostly ad hoc.

For his cabinet, Borissov recruited mostly experts most of whom had not run for deputies in the 2009 elections and had little political experience at national level (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2010). This matched the promise made by GERB in the electoral campaign to break with the patronage practices of the previous governments. The number of deputy prime ministers was decreased, the controversial ministries of state administration and of emergency situations were disbanded, and various cuts in the size of the administration promised. During the second half of 2009, partly as result of this “cleaner politics” approach, the government enjoyed an increasing popularity among the Bulgarians.

Personnel policy

The troubles, however, started quickly. Between 2009 and 2012, the cabinet underwent numerous personnel changes, reflecting the difficulties faced by any new party entering national government but also the somewhat arbitrary personnel policy of Borissov. The first year in power was probably the most turbulent: during 2010, five ministers were dismissed because of public scandals, poor performance in Brussels, international embarrassment, conflict of interests, allegations of questionable economic links, inability to handle professional tasks and openly radical nationalistic statements (for details see Kolarova and Spirova Citation2011).

These cabinet reshuffles reflected the inability of the Borissov I cabinet to formulate efficient policy in various sectors. This was somewhat explained by the existing constrains of the poor economic situation of the country, a fiscal policy of austerity, and the international pressure coming from the EU. Choosing people whom he trusted personally rather than people with political and social connections led to a general discomfort with some of his ministerial appointments. This trend continued in the next years, although none of the personnel changes were as scandalous as the ones carried out in 2010. Ministers resigned for personal reasons, some to take on other political careers. Replacements came from the career paths within the ministries and some reflected the attempt of Borissov to look into the younger and more professional circles for ministerial appointments in high-risk policy areas. A case of point is the 38-year Diana Kovacheva, then director of Transparency International-Bulgarian Chapter who was made Minister of the Judiciary in 2011, then a key area of reform and a major issue in the EU regular monitoring reports (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2012).

In 2012, possibly in anticipation of the end of tenure, but also as a consequence of the continuous institutionalisation of his party, Borissov’s personnel policy changed. As the party now had a six year history of elite recruitment, it had available cadres to take over the vacated cabinet positions. Party activists with limited professional and management expertise came to replace the experts with mostly corporate or professional background. The new appointees in 2012 were remarkably young for their important portfolios, but came from the active core of GERB. Their appointment was enthusiastically supported by the parliamentary group, but not by the professional circles in their respective policy areas, causing some public outcries against Borissov’s choices in parliament and in the media.

Parliamentary support

In parliament, Borissov’s cabinet faced weak opposition. The center-right parties – Blue Coalition (SK) and Order, Law and Justice (RZS) –, although not having signed the agreement to support the cabinet, provided the political backing needed for the PM and clearly distinguished themselves from the BSP and the party of the Turkish minority, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), seen as the “partners in crime” at the time for having been part of the three-party coalition between 2005 and 2009.Footnote8 A vote of no-confidence against the Borissov government was initiated by BSP and DPS on 1 October 2010, but failed as it was not supported by the rest of the opposition. In addition, the parliamentary group of GERB, although inexperienced, remained remarkably stable: unlike the ones of RZS and Ataka, which both disbanded by 2011, the GERB parliamentary group did not lose a single member. This is often attributed to the hierarchical structure instituted by Borissov within GERB and his strong leadership (Todorov Citation2016).

In early 2011, Borissov demonstrated his political acumen by using a seldom utilised institutional tool: a vote of confidence in the overall policy of his cabinet. With half of the opposition parties loyal to his minority cabinet, the vote passed with a comfortable margin – 141 out of the 240 MPs, with only the BSP and DPS voting against. This vote aimed to prevent the escalation of a political scandal caused by leaked wiretapped conversations between the PM and Vanyo Tanov, the National Customs Agency Director. Anticipating a vote of no-confidence that could be more problematic to manage, Borissov referred to a provision in the Rules of Organisation and Procedure of the 41st National Assembly (Art. 98) stipulating that no-confidence votes should not be initiated six months after a successful confidence vote and called the confidence vote.

The Constitutional Court declared this stipulation unconstitutional following the referral of the center-left opposition. Two more votes of no-confidence were initiated by the BSP and the DPS shortly after this decision. While both failed, in a momentous step, some of the center-right deputies from the disbanded RZS and ATAKA groups joined the center-left to show their growing dissatisfaction with PM Borissov and his cabinet, which continued into early 2013. Despite numerous policy-related challenges to the cabinet, the parliamentary opposition continued to be unable to benefit from the situation and the minority government remained in power. While Borissov’s public support was declining, there was no alternative emerging in the fragmented and still publicly discredited opposition, particularly as the MPs from the smaller parties saw no chance of being re-elected. Early elections thus seemingly remained unlikely.

The surprise resignation

While in early 2013 the GERB minority government had a comfortable “working majority” of its 117 MPs and 12 independent MPs who explicitly committed themselves to support the cabinet bills, Borissov unexpectedly resigned. Major social protests had erupted against the government, first in Sofia and then in other big cities. Motivated by the high energy costs during the winter months, the protests broadened to also include environmental and anti-monopolism issues, and widened in scale and demands to call for the resignation of the finance minister and a major cabinet reshuffle. After small scale clashes with the police ensued with a few wounded protesters, PM Borissov submitted, quite unexpectedly, the resignation of the government on 20 February 2013. Most observers agree that Borissov shrewdly decided to distance himself from the executive. Following constitutional provisions, a different, caretaker, cabinet is appointed in Bulgaria and the parliament disbanded if early elections are called at any moment. The President thus disbanded parliament and appointed a non-partisan cabinet headed by Marin Raykov. Borissov thus let the caretaker PM lead the country into early elections in March 2013, instead of waiting out until the regularly scheduled ones three month later (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2015). At that point Borissov had almost finished his mandate: the resignation came when already 87% of his constitutional mandate were passed (see for comparative indicators). As parliament had not requested his resignation, the image of him calling the shots was maintained. As a result, at the early elections in March 2013, GERB maintained its plurality position in electoral competition. Still, GERB’s loss of about 20 deputies and the presence of only four parties in parliament allowed the second-placed BSP to form a center-left coalition. A period of political instability followed, ending with another call for early elections in 2014 (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2015; Spirova and Sharenkova-Toshkova Citation2019).

Borissov II: battling ideological heterogeneity

Only 18 months after the February 2013 protests that led to his withdrawal from power, Borissov re-emerged from the 2014 election as the leader of the country’s most popular party again, and this time without any alternatives for taking over the PM position. However, there was a total of eight parties and electoral alliances gaining seats in parliament and executive coalition negotiations did not promise to be easy. After a prolonged process, GERB formed a coalition with the Reformers’ Block (RB), an alliance of several parties, and asked for the parliamentary support of two smaller parties: the Alternative for the Revival of Bulgaria (ABV), formed in the early 2014 as a splinter from the BSP around Bulgaria’s former president Parvanov, and the Patriotic Front (PF), an alliance of two nationalist parties.

This coalition controlled 45% of the seats in parliament, but had the promised support of another 30 deputies, a total of about 57% of the seats. Borissov’s second cabinet took office on 7 November, promising in its program a “stable parliamentary majority and a pro-European reformist government for the stable development of Bulgaria” (Ministerski savet Citation2014). Only GERB and RB formally signed the coalition agreement; ABV agreed to support the government in exchange for one ministerial portfolio for ABV, but was not formally part of the coalition agreement, and PF exchanged its support for policy concessions, including the consideration of proposals to end broadcast news in Turkish on Bulgarian National TV. The coalition was hailed as the cabinet of a “reformers’ majority,” but was so diverse that maintaining it required strong political will and acumen. While GERB was not a new party any more, it was still faced with some of the challenges that characterised Borissov’s first cabinet.

Personnel policy and parliamentary support

Early personnel changes in Borissov’s second cabinet reflected the style of his first one: the PM took decisions based on his personal approval or disapproval of developments in the ministries and agencies. However, while Borissov could control his own party and its elite, the instability of his coalition partners became evident as policy disagreements and conflicts emerged. In fact, cabinet reshuffles and intra-coalitional dynamics became intimately intertwined.

One case of ministerial replacement is indicative of the challenges the heterogeneous coalition was posing for the PM. In May 2015, Minister of the Judiciary Hristo Ivanov (RB) sought to increase the independence of the judiciary and limit its politicisation. This necessitated constitutional changes and a bill to that effect was introduced in the National Assembly. While publicly hailed as the first real attempt to reform the judiciary sector by professional organisations and civil society groups, the bill proved very difficult politically. In the parliamentary vote in early December, the two-thirds majority required for constitutional amendments failed to materialise, thus de facto refusing to support the minister on that key issue, leading to his resignation. Clearly an indication of growing intra-coalitional problems, PM Borissov took the opportunity created by the inability of the junior coalition partner to nominate a replacement from the ranks of GERB. The parliamentary vote for the new cabinet minister indicated both further intra-coalition trouble as half of the RB deputies votes against the GERB candidate Bachvarova, but also a diversification of the support for the cabinet, as the oppositional Bulgarian Democratic Centre (BDC) backed the new appointment. The choice of a GERB candidate was thus a clear warning signal to the governing partners and the opposition that dynamics within the coalition were changing, and Borissov used the vote as an opportunity to clarify his friends and foes within the parliamentary arena. The move demonstrated the maneuvering necessary to maintain a heterogeneous coalition in an even more heterogeneous parliament.

These tensions only increased over the course of 2016, when further personnel changes in the cabinet indicated problems within the Reformists Bloc. In March, Democrats for Strong Bulgaria (DSB), a constituent party of RB openly joined the opposition. In May, in anticipation of the presidential elections scheduled for November, the left-wing coalition partner ABV left the government, and its minister Ivaylo Kalfin (Minister of Labour and Social Policy) resigned and was replaced by the independent Zornitsa Russinova. This was seen as the first definite sign that the coalition formula of the cabinet needed to change. In fact, it led to renegotiations to incorporate cabinet ministers from the Patriotic Front, which until then had not been part of the cabinet. Cabinet reshuffling was planned for after the presidential elections, and political observers expected that the share of RB ministerial portfolios would be decreased to reflect RB’s decreasing support for the cabinet in parliamentary votes and its anticipated poor performance at the presidential elections.

The unnecessary resignation

At that moment, Borissov seemed to have decided to capitalise on the growing problems within and among his partners. The popularity of his cabinet and himself was declining substantially as the year went on (Alpha Research Citation2016), with the intra-coalition tensions and scandals seen as the major reason for this development. As the presidential elections approached, he made a clear public commitment to step down as PM if the GERB presidential candidate failed to win. The landslide victory of the candidate backed by the Socialists in the second round of the presidential race indicated that a considerable proportion of government supporters voted for the opposition candidate. True to his promise, Borissov resigned on 14 November. This step was not necessary in political terms, as the cabinet relied on the support of more than 140 MPs (with 121 needed for a majority). Over the course of the year, parliamentary life had reflected the gradual change in the coalition format, but a vote of no-confidence would not have received the necessary support. Parliamentary party groups remained fairly stable with the exception of DPS, which lost quite a few members due to internal conflicts. With a visible stronger link between the two nationalistic parties – Patriotic Front and ATAKA, with the latter moving from a radical opposition to a support party –, the situation in parliament could have allowed Borissov to remain in power. But he clearly had other plans. In fact, as it transpired in the weeks after, when the other parliamentary factions were trying to form a new cabinet, Borissov was determined to push for early elections. With GERB refusing to participate in the cabinet talks, the newly elected president Radev dissolved parliament and called early elections.

Borissov III: two years of a streamlined coalition

It did not surprise many observers that the elections of 25 March 2017 saw GERB emerging as the dominant party for the fourth time in a row since 2009. As illustrates the party managed to increase its seat share and re-assume a much more central role in the coalition government that did not have a minority status any more.

With GERB being clearly the strongest party in parliament, Borissov was set to remain PM. With the nationalist United Patriots (UP) as coalition partner, Borissov announced the agreement on the government program on 13 April 2017 and was voted into office on 4 May 2017 by parliament.

This cabinet was a less diverse and more right-of-center version of Borissov II, as two of the more mainstream, but also ideologically heterogeneous partners – Reformist Block (RB) and Alternative for Bulgarian Revival (ABV) – had gone. Although the new cabinet posed less challenges in terms of ideological cohesiveness, the problems of allying with the nationalist UP were demonstrated immediately. By then, of course, GERB was no longer a new party and a lot of its original challenges had transformed to reflect intra-coalition dynamics rather problems of fledgling executive party.

Personnel policy

The personnel policy of Borissov III indicated this shift. Only days after his appointment, the Deputy Minister of Regional Development and Public Works, Pavel Tenev (UP), resigned after a scandal broke out because an old photograph appeared in Internet of him giving a Hitler salute to wax figures of Nazi officers in a museum in Paris. Similarly, the appointment of UP co-chairman and Deputy Prime Minister Valeri Simeonov to head Bulgaria’s National Council on Co-operation on Ethnic and Integration Issues prompted protests among NGOs. Allegations of corrupt deals brought the Minister of Health down in early October, when Borissov replaced him with another GERB nominee. Further personnel changes followed in 2018, and reflected both response to policy problems and intra-coalitional conflicts.

In September 2018, a tragic bus accident on the Sofia-Svoge road led to the resignation of three cabinet members: the Minister of Interior, the Minister of Regional Development and Public Works and the Minister of Transport, Information Technology and Communications. Their resignation occurred within a week of the accident, for which poor road reconstruction and inefficient control and maintenance appeared to be to blame. As all three ministers were from the GERB quota, the party suffered a serious blow in terms of public criticism (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2019). In November, two scandals triggered further resignations. First, in early November, accusations of exchanging Bulgarian passports for bribes led to a wave of dismissals in the Agency for Bulgarians Abroad, including its chairman Petar Haralampiev, a UP representative. Although not a minister, the dismissal of Haralampiev and his indictment for taking bribes challenged the position of the junior coalition partner. Later that month, another resignation followed. Valeri Simeonov, deputy PM responsible for economic and demographic policy, resigned after 26 days of public protests demanding his dismissal. These protests were triggered by Simeonov’s inappropriate and offensive comments concerning the parents of disabled children who had been acting, for more than 240 days, as a pressure group in demand of additional social services and financing for their children (Kolarova and Spirova Citation2019). Borissov’s grip on power was thus somewhat challenged as both ministers from the coalition partner, but also some personally chosen by him began to attract public outcry.

Parliamentary support

Despite these scandals and public allegations of misconduct, Borissov and his third cabinet survived three parliamentary votes of no confidence. In addition to maintaining the integrity of his own parliamentary group, Borissov also preserved the firm backing of his coalition partners. All three non-confidence votes were introduced by the Socialists and supported by the DPS, but none managed to attract enough deputies from the governing majority or its tacit supporter Volya.Footnote9 Indeed, the voting patterns in all three no-confidence motions, as well as the general voting pattern in the National Assembly, point to the new supporting party role played by Volya. This leads to a widened parliamentary support for the cabinet, despite the active opposition by BSP and DPS.

Conclusion

As of the end of 2019, PM Borissov had by far outdone the Bulgarian PMs before him to survive in chief executive office. None of his counterparts since 1990 has managed to return to the PM position and most lost major political influence even within their own parties. Even Borissov’s political “father” Simeon Saxecoburggotski was much less successful. His popularity deteriorated dramatically during just one prime-ministerial tenure, his party remained in power but sentenced itself to political suicide by joining the triple coalition of 2005 and by 2009, and finally disappeared from any meaningful position in Bulgarian politics while Saxecoburggotski returned to his royal position as political observer.

What can explain Borissov’s extraordinary longevity in chief executive office in the Bulgarian context? What does the experiences of Borissov I, II and III suggest in terms of the theoretical considerations about PMs from a genuinely new party and faced with a minority situation in cabinet and unstable political allies suggested in the beginning of this article? In many ways, the longevity of Borissov contradicts the theoretical expectations which suggest a short, unstable tenure in office.

First of all, to pre-empt some of the challenges facing new parties in government, Borissov moved fast to build GERB as a viable political entity. Political activity started at the local level, and GERB invested quickly into setting up a strong organisational network and a pool of local political elites. This helped in a significant way with the recruitment of cadres for the executive and securing support from the party on the ground for the newly minted PM and his minority cabinet during 2009–2013. This suggests that the newness of parties as hindrance to PM durability needs to be seen in context, as sometimes developments on sub-national level might be concealed by the newness at the national political scene while at the same time they might prove crucial for the ability of the party (and its PM) to govern.

In a similar vein, to resolve the problem of not having enough reliable party representatives to staff the executive, Borissov built a loyal personal following. Unlike Saxecoburggotski, he intertwined it within the organisational structure of the party he chaired. As a result, he was able to maintain a strong supply of GERB appointees in various levels of the state administration, including local government. This tendency, naturally, created problems among the public and his political partners. Personnel decisions within the executive made with such considerations in mind, often, especially during his first cabinet, left aside concerns with professionalism and expertise. This trend was both a blessing and a curse for Borissov’s ability to remain in the driver’s seat of Bulgarian politics. Accusations of lack of concern with the opinion of the partners were expressed publicly in the media by coalition co-chair Simeonov in 2017, causing further tremors in the political alliance. This suggests a tradeoff between a leader individual ability to build a following and their party ability to maintain stable support by its partners. In turn, this points to the need to consider individual and structural determinants of PM power in an interactive manner, offering further empirical evidence to approaches such as Strangio et al. (Citation2013) in understanding and explaining executive power.

A third feature that has contributed to Borissov’s almost permanent place in politics seems to be an uncanny ability to bluff his way into a more powerful position by using the existing institutional possibilities. In both 2013 and 2016, he resigned when he did not have to, making these decisions an issue of personal honour. As a result, he was able, in one case, to distance himself and his party from the incumbency and not experience all negative associated with it, and in the second case, managed to shake off inconvenient coalition partners and return to power in a much more trimmed down and homogenous cabinet. These decisions were not without political risk, but in situations where alternatives were almost non-existent, his decisions seemed to have brought only benefits to him and GERB. By distancing himself from the incumbency in both cases, he managed to capitalise on the traditional support of his party. It also demonstrated a somewhat pragmatic approach to politics – Borissov and GERB have forged coalitions with center-left and center-right parties that would allow him to remain in the chief executive office.

These decisions helped Borissov pre-empt another challenge that new parties face in government – that of their identity changing from a challenger to a member of the establishment. Going beyond the particular case, this again demonstrates that there are institutional opportunities that can be used by new parties to bypass their obvious shortcomings and capitalise on their images as challengers, even when in government. To take this further, this can lead to an alternative theoretical proposition: the newness of the party brings with itself an energising political momentum that allows such parties to distance themselves from incumbency with greater success than established parties.

Despite his ups and down, Borissov remained the most popular politician in the country with approval ratings have remained stable at about 33% through the ups and down of his political decade (Alpha Research Citation2019). His experience shows that the challenges facing new parties in government and their leaders as PMs can be partially countered by targeted personnel policy and smart choice of allies in coalition negotiations. While history is still to show how Borissov will exit the political arena and whether he will not be outmaneuvered by his competitors, his political figure will certainly leave a mark on Bulgarian politics and coalition governance. Further research into the interplay of personalities and party governments in the CEE region is clearly needed to understand why some PMs from new parties make it and others do not, even when faced by similar institutional contexts. Such insights will certainly contribute to the more general understanding of PM survival and the study of coalition politics more generally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Spirova

Maria Spirova is an associate professor of Comparative Politics and International Relations at the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University. She works in the area of comparative politics with a regional focus on Eastern Europe and her research interests include political parties, party patronage and corruption and the democratic representation of ethnic minorities.

Radostina Sharenkova-Toshkova

Radostina Sharenkova-Toshkova is a historian and ethnographer who works on cultural heritage and memory institutions, cultural policy making and shaping of history narratives in post-colonial and post-totalitarian situations. She teaches Politics of Memory at the Institute of Political Science, Leiden University.

Notes

1 This article does not assess or explain the success of PM Borissov in terms of the policy impact or the general development of the country under his cabinets, but only his ability to remain in power and return to power from 2009 until 2019.

2 Parts of the data and discussion used here have been published in Kolarova and Spirova Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012, Citation2017 and Citation2019 and Spirova Citation2015.

3 In fact, the index itself combines both some of the explanatory variables (relations within the party, leadership position) and the dependent variable (time in office) of this study. While we do not use the index, we use the equivalents of some of its components (Bennister et al. Citation2015, 424) to explore the relationship among them.

4 Because of the more complicated constitutional mandate, the cabinets of the Grant National Assembly (1990-1991) are excluded from the analysis.

5 His supporters as well as his self-presentation still refers to him as His Majesty Simeon II, but for the rest, he remains Simeon Saxecoburggotski, Bulgarian citizen and political leader. Simeon II never abdicated from the throne which he was forced to leave as a six-year-old child and then reside in Spain in exile until 2001 (Kalinova and Baeva Citation2010).

6 On 6 April 2001, two and a half months before the regularly scheduled elections, Simeon Saxecoburggotski delivered a notorious speech in Sofia in which he made big promises, the boldest of which was to change Bulgaria in 800 days (Simeon II Citation2001).

7 The Bulgarians Socialist Party (BSP), the second largest in parliament, had 16.7% of the seats.

8 The 2005–2009 coalition of BSP, DPS and NDSV had been a coalition of mutual accommodation that guaranteed the distribution of benefits to all members, a practice strongly disliked by the public.

9 Volya, a small party that joined the National Assembly in 2017, is insofar similar to GERB as it is built around the personality of its leader, the businessman Veselin Mareshki (Spirova 2018, 39).

References

- Alpha Research. 2019. Оценка за дейността на министър председателя. [Assessment of the work of the PM], https://alpharesearch.bg/monitoring/26/.

- Alpha Research. Оценка за дейността на правителството [Assessment of the work of the cabinet], http://alpharesearch.bg/bg/socialni_izsledvania/political_and_economic_monitoring/pravitelstvo.html.

- Baylis, T. A. 2007. “Embattled Executives: Prime Ministerial Weakness in East Central Europe.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 40 (1): 81–106.

- Bennister, M., P. ‘t Hart, and B. Worthy. 2015. “Assessing the Authority of Political Office-Holders: The Leadership Capital Index.” West European Politics 38 (3): 417–440.

- Blondel, J., and F. Müller-Rommel, eds. 2001. Cabinets in Eastern Europe. London: Palgrave.

- Bolleyer, N. 2008. “The Organizational Costs of Public Office.” In New Parties in Government. In Power for the First Time, edited by K. Deschouwer, 17–44. London: Routledge.

- Browne, E. C., J. P. Frendreis, and D. W. Gleiber. 1984. “An ‘Events’ Approach to the Problem of Cabinet Stability.” Comparative Political Studies 17 (2): 167–197.

- Buelens, J., and A. Hino. 2008. “The Electoral Fate of New Parties in Government.” In New Parties in Government. In Power for the First Time, edited by K. Deschouwer, 177–194. London: Routledge.

- Burrett, T. 2016. “Explaining Japan’s Revolving Door Premiership: Applying the Leadership Capital Index.” Politics and Governance 4 (2): 36–53. doi:10.17645/pag.v4i2.575.

- Deschouwer, Kris. 2008. New Parties in Government. In Power for the First Time. London: Routledge.

- Dowding, K. 2013. “Prime-Ministerial Power Institutional and Personal Factors.” In Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart, and James Walter, 57–78. Oxford. Scholarship Online: May 2013, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199666423.003.0001

- GERB. 2008. The New Rightist Treaty for Bulgaria. Available at: http://gerb-bg.com/Gerb_Program_final_eng.doc Last accessed on April 15, 2008.

- Grotz, F., and T. Weber. 2012. “Party Systems and Government Stability in Central and Eastern Europe.” World Politics 64 (4): 699–740.

- Grotz, F., and T. Weber. 2016. “New Parties, Information Uncertainty, and Government Formation: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe.” European Political Science Review 8 (3): 449–472.

- Grotz, F., and T. Weber. 2017. “Prime Ministerial Tenure in Central and Eastern Europe: The Role of Party Leadership and Cabinet Experience.” In Parties, Governments and Elites: The Comparative Study of Democracy, edited by P. Harfst, I. Kubbe, and T. Poguntke, 229–248. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Harper, M. A. G. 2003. “The 2001 Parliamentary and Presidential Elections in Bulgaria.” Electoral Studies 22 (2): 325–395.

- Helms, L. 2016. “The Politics of Leadership Capital in Compound Democracies: Inferences from the German Case.” European Political Science Review 8 (2): 285–310. doi:10.1017/S1755773915000016.

- Kalinova, E., and I. Baeva. 2010. Bulgarian Transitions 1939-2005. Sofia: Paradigma.

- Karasimeonov, G. 2010. The Party System in Bulgaria. Sofia: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2010. “Bulgaria 2009.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 49 (7-8): 909–918.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2011. “Bulgaria 2010.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 50 (7-8): 49–56.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2012. “Bulgaria 2012.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 51 (1): 922–927.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2015. “Bulgaria 2013.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 53 (1): 45–56.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2017. “Bulgaria 2016.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 56 (1): 36–43.

- Kolarova, R., and M. Spirova. 2019. “Bulgaria: Political Developments and Data in 2018.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 58 (1): 37–42.

- Kostadinova, T., et al. 2017. “Bulgaria: Organizational Structure and Trends in Bulgarian Party Politics.” In Organizational Structures of Political Parties in Central and Eastern European Countries, edited by K. Sobolewska-Myślik, 85–108. Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press.

- Laver, M., and N. Schofield. 1990. Multiparty Government: The Politics of Coalition in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mediapool. 2011. https://www.mediapool.bg/mbmd-s-nai-dobar-rezultat-e-kabinetat-na-kostov-s-nai-visoko-doverie-e-premierat-borisov-news187631.html.

- Ministerski savet. 2014. Programna deklaracija. Available at: http://www.government.bg/cgi-bin/e-cms/vis/vis.pl?s=001&p=0211&n=122&g, last accessed 15 February 2015.

- Mueller-Rommel, F. 2005. Types of Cabinet Durability in Central Eastern Europe. UC Irvine: Center for the Study of Democracy. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8cv4134w.

- Müller, W. C., T. Bergman, and G. Ilonszki. 2019. “Extending the Coalition Life-Cycle Approach to Central Eastern Europe – An Introduction.” In Coalition Governance in Central Eastern Europe, edited by T. Bergman, G. Ilonszki, and W. C. Müller, 1–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sikk, A. 2005. “How Unstable? Volatility and the Genuinely New Parties in Eastern Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 44 (3): 391–412.

- Simeon, I. I. 2001. “Обръщение към нацията.” Mediapool.bg, April 1. https://www.mediapool.bg/obrashtenie-kam-naroda-na-simeon-sakskoburggotski-6-april-2001-news15818.html.

- Somer-Topcu, Z., and L. K. Williams. 2008. “Survival of the Fittest? Cabinet Duration in Postcommunist Europe.” Comparative Politics 40 (3): 313–329.

- Spirova, M. 2007. Political Parties in Post-Communist Systems: Formation, Persistence, and Change. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spirova, M. 2015. “Bulgaria.” European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 54 (1): 44–53.

- Spirova, M., and R. Sharenkova-Toshkova. 2019. “Bulgaria Since 1989.” In Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989, edited by S. P. Ramet, and C. M. Hassenstab, 449–476. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strangio, P., P. ‘t Hart, and J. Walter. 2013. “Prime Ministers and the Performance of Public Leadership.” In Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart, and James Walter, 1–31. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2013, DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199666423.003.0001

- Todorov, A. 2016. Политическата хегемония на ГЕРБ [The political hegemony of GERB] http://eprints.nbu.bg/3430/1/%D0%9F%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B0%20%D1%85%D0%B5%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%8F%20%D0%BD%D0%B0%20%D0%93%D0%95%D0%A0%D0%91.pdf.