ABSTRACT

Despite the diffusion of the paradigm of central bank independence, there is still meaningful variation in the operating missions of central banks both across countries and over time. Through a detailed qualitative case study, this article develops the concept of the operating mission of the central bank and applies it to the case of the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) to provide a more complete understanding of mission shift. Our findings demonstrate the critical role of policy agency, as the central bank governors moulded the operating mission of the central bank, even in the face of dominant international norms.

I. Introduction

The emergence of central bank independence (CBI) as an international norm in the latter half of the twentieth century portrays an image of autonomous, technocratic central bankers who are guided by clear rules on how to achieve price stability. However, the emphasis on CBI as an international norm, or a case of policy diffusion (Bernhard Citation1998; Epstein Citation2008; Thomassen Citation2017), in much of the related literature neglects the remaining diversity of independent central banks. Put simply, there is more than one way to be independent. Precisely the pressure to demonstrate independence (Johnson Citation2016; McNamara Citation2002) may distract from the real-existing variation in the strategic goals of central banks (CB) over time and across countries (Marcussen Citation2005).

This study aims to understand the dynamics of the shifting operating missions of the CB in post-regime change Hungary. We introduce the concept of operating mission as a counterpart to the formal mission of monetary authorities, set by the legislature. Although the international pressure to prioritise a “verifiable commitment to price stability” as the formal goal of these institutions has been pervasive (Gabor Citation2010, 43–49), we observe substantial variations in the emphasis on other goals and the understanding of the relationship of the CB with the global economy and international actors.

The notion of operating mission, our theoretical contribution, is a useful concept for understanding how the autonomy of central bankers (due to CBI), allows them to act as policy agents and leverage this power to achieve their policy goals even in the face of seemingly strict international norms and fixed domestic legal requirements. This finding relates to an early debate on CBI, where Milton Friedman expressed reservations about an independent monetary authority due to the excessive influence of the opinion of bankers (Schwartz Citation2009, 5). While it is debatable what constitutes “excessive influence”, we do agree with the general thesis that CBI does increase the potential impact of “the opinion of bankers” on monetary policy notwithstanding the statutes delineating the goal and instruments of independent central banks.

We explore the agency of central bankers through a case study of the Hungarian National Bank (Magyar Nemzeti Bank – MNB) in the post-regime change period (starting in 1991). Despite the stability of institutions and the formal mission, we observe meaningful shifts in the observed mission of the MNB (Sebők Citation2018).Footnote1 We conceptualise the operating mission as the de facto, rather than the de jure (or formal) goal structure of the CB. Beyond the primary formal goal of price stability, the operating mission may also cover optional strategic goals and the idiosyncratic selection of targets and instruments. Such a study of shifts in the operating mission enables a nuanced investigation of the complex interaction of international norms (such as inflation targeting), the institutional features of CBs, and the strategy and ideational background (Hall Citation1989) of policy agents, specifically central bankers.

Our empirical analysis suggests that international influences and partisan politics have limited explanatory power for shifting operating missions in Hungary. Mission alterations were mostly out of sync with international developments and the timing of changes does not correspond to electoral victories of right- or left-wing parties either. Therefore, our focus is on what changed within the CB, focusing on incoming governors. We argue that the ideational paradigm of the central banker fundamentally shapes the operating mission of the monetary authority. This demonstrates the independent power of domestic forces even in one of the most depoliticised (and therefore: policy-transfer prone) areas of policymaking. Furthermore, it clarifies a new potential causal mechanism regarding how partisan politics and individual characteristics of central bank governors may indirectly influence monetary policy decisions without abandoning the principle of CBI.

In what follows, we first present the theoretical framework and our conceptualisation of the CB operating mission, which provides the analytical framework for the analysis of the interviews. Then we outline the research design and our qualitative methodology. The subsequent section presents our analysis of the MNB’s operating mission from 1991 on. In the Discussion, we revisit the theoretical debates surrounding CB missions in light of the empirical analysis. The final section concludes by recapitulating our results and by exploring avenues for further research.

II. Theory

The concept of the operating mission of an independent central bank

Given the terminological novelty of the outcome of interest, the operating mission of CBs, we here provide a conceptualisation of this notion. The scope of the proposed conceptual framework is constrained to independent monetary authorities in the continental European context. Correspondingly, we exclude cases where CBI has been called into question, such as Japan (Dwyer Citation2012), and cases where the formal mission prioritises goals unrelated to price stability, such as in the United States where the Federal Reserve observes full employment as a formal goal.Footnote2 Furthermore, we focus on CBs in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), as these are in an asymmetrical relationship with the major “agenda-setting” CBs.

Within this scope, most of the existing literature focuses on the monetary policy goals or outputs of the institutional system of CBI (Fischer Citation1995; Maxfield Citation1998; Thomassen Citation2017). However, there is already a push to move beyond CBI per se, as there is significant dissimilarity between independent monetary authorities. Beyond research on the factors of CBI level (and the effects of institutional structures on secular parameters like monetary supply growth or unemployment (Bodea and Hicks Citation2015; Crowe and Meade Citation2008; Garriga Citation2016)) only a limited number of studies responded to this challenge by examining the varieties of monetary policy within independent CBs. For example, the diversity in approaches to CBI was already apparent when Fischer delineated two forms of CBI: goal independence and instrument independence (Fischer Citation1995, 5). The “conservative central banker” has both goal and instrument independence (Rogoff Citation1985).

Binder (Citation2020) analyses de facto independence by using a dataset on political pressure on central banks. She finds, based on third-party reporting (e.g. Economist Intelligence Unit), that in an average quarter in the 2010s, 6% of monetary authorities faced political pressure (mostly for easing monetary policy). Baerg, Gray, and Willisch (Citation2020, 17) define the policy autonomy of central banks as a composite of policy independence (the classic, “formal” CBI measure) and “limitations on lending”. While these approaches add new insights to the CBI literature when it comes to the actual room for manoeuvre of central banks vis-á-vis outside actors (as is the case with government lending with Baer et al.), they do not operationalise the myriad of ideational choices governors face within the domain of monetary policy and, therefore, the policy content of their strategies.

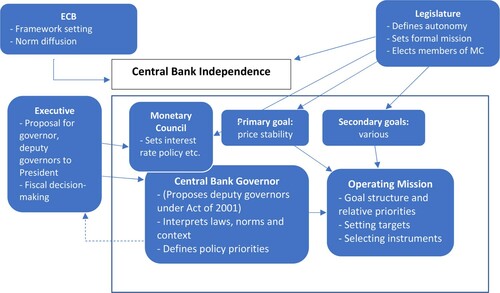

In light of this gap, we conceptualise the operating mission of a central bank as its de facto, rather than the de jure (or formal) goal structure, which is nevertheless based on a clear legal mandate (see ). The operating mission may both cover a set of legally binding (i.e. price stability) and optional strategic goals (e.g. implicit exchange rate targets, financial stability or real growth), provided they do not clash with the primary goals. It implies that there are alternative paths that preserve room for manoeuvre for central bankers while still fulfilling the formal institutional mission. Given that CBI was vital for gaining international legitimacy for central banking (McNamara Citation2002), there are strong incentives to maintain an independent CB as a formal institution and rather introduce variation into the mission and mechanisms applied by the CB governors.

displays the operating mission within the system of CBI. Tailored to the Hungarian context yet with broader applicability, the legislature defines CB autonomy and sets its formal mission of primary and secondary goals. Both CBI and goal setting are embedded in the ECB’s legal and normative confines. Together with the executive, it influences the Monetary Council through appointments. However, CBI “shields” the governor and his/her council from direct political interference, opening room for manoeuvre to interpret the legislative and (internationally) normative framework and choose among policy priorities in achieving “optimal” monetary policy as interpretatively understood.

Since 2001, the right of appointment of Council members are shared by the President and Parliament, with the first bearing responsibility for the Governor and his/her two Deputies and the latter for the remaining members. However, whereas previously the Governor in fact had the right to propose two deputies for appointment (and dismissal) to the President of the Republic, since 2013 the Prime Minister exercises this responsibility. Moreover, the total number of Council members has been extended from seven to nine, and the number of Deputies from two to a maximum three.

Despite the aforementioned international pressure to prioritise price stability as the formal goal of these institutions, we still observe substantial variations in the emphasis allocated to other goals. In the Hungarian case the legislative branch set price stability as the primary goal of monetary policy in the 2001/LVIII. Law on the MNB. This was later reinforced in the new MNB law of 2013 (2013/CXXXIX), however, new secondary goals were added due to the institutional rearrangement of financial supervision (now conducted within the MNB and not by a separate agency).

The central bank law also specifies the instruments of monetary policy. However, the CB maintains independence in how to combine these instruments in a timely manner, when to put an emphasis on one or the other. The same applies to finding a balance between secondary goals (see endnote 1) and setting intermediate-level monetary policy targets. Furthermore, the executive branch (Prime Minister) and the President of the Republic only directly affect monetary policy through the appointment of the members of the Monetary Council and the governor (while the coordination requirement between fiscal and monetary policy offers indirect tools as well).

In short, CBI does not imply either price stability as the primary goal or the adaptation of the inflation targeting regime (it is not even specified in the text of CB laws – see again where the inflation target is just one option within the policy toolbox). While these three concepts mostly arrived as a package in CEE throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the institutional framework of CBI (a requirement of the European System of Central Banks), the goal of price stability and the practice of inflation targeting are not inseparable. In fact, as we show, they were separated in the real-existing policymaking of MNB. Therefore, in what follows we move beyond the formal mission and make use of the newly defined concept of the operating mission.

The four types of operating missions in CEE

We account for variation in the operating mission of CBs in two key dimensions (for this we build on our earlier work: Sebők and Makszin (Citation2018)). The first one is economic ideology, which ranges from an orthodox understanding of CBs that exclusively focuses on price stability (i.e. German Bundesbank) to heterodox economic approaches that also consider other economic variables, such as nominal GDP targeting, financial stability, or exchange rate targets (Epstein and Yeldan Citation2009).

We define orthodox monetary policy – in the context of the period investigated – as strict adherence to price stability through the application of inflation targeting. Here we follow the definition by Adolph (Citation2013) of central bank conservativism: the more conservative a central banker is, the more likely he/she will value price stability above all other goals and the more restrictive attitude to CB agency they will take. We use this as a synonym of orthodoxy, and with – the below-mentioned qualifications – neoliberalism, which can be considered to be the post-1970s “common sense” in global finance and central banking (Ban Citation2016; Macartney Citation2010). This can be understood as an ideal type constructed in the image of post-war Bundesbank. It has remained a beacon of price stability even as some other trend-setting institutions (such as the FED or the ECB) deviated from its “norm”.

We label any deviation from this as heterodox. For the sake of parsimony, we apply the “catch all” label of heterodoxy to both policy philosophies which prioritise goals other than price stability and deliberately unconventional policies (which propose alternative instruments for achieving price stability other than inflation targeting).Footnote3 The orthodox approach reflects a CB that closely follows the “letter of the law”, which leaves little room for bureaucratic autonomy. A heterodox understanding openly recognises the authority of central bankers to adopt approaches in the “spirit of the law”, representing significantly greater flexibility (Mosley Citation2005).

One key point is that economic heterodoxy neither violates CBI, nor does it necessarily derail price stability as the primary goal of CBs (i.e. a heterodox central banker is not necessarily a “rogue” one). There is no true contradiction here: orthodoxy puts a self-enforced limitation on CBI as governors adhering to it deliberately tie their hands to the formal mission – but the absence of such limitations would still be perfectly in line with the general tenets of CBI. In short, CBI allows for central bankers to operate relatively freely despite the presence of the formal mission centred on price stability.Footnote4

Besides the well-established concepts of conservatism and orthodoxy we also employ a second ideational dimension to analyse operating missions. This captures the outlook of the CB, varying from closely conforming to international norms on monetary policy and emphasising international co-operation to an emphasis on the uniqueness of national CBs and its monetary strategies. The internationalist category on this dimension relates to the understanding of a country’s monetary authority as a unit in a network of bureaucratic institutions with similar goals and likeminded leaders.Footnote5 The nationalist outlook rather emphasises the embeddedness of the CB into the country-specific context, which includes economic conditions and government goals provided they do not conflict with price stability. The intersection of these two dimensions generates four ideal types of CB operating missions, as displayed in (we explicate these categories in more detail in the empirical section).

Table 1. Varieties of central bank operating missions.

The impact of banker’s paradigms on operational missions

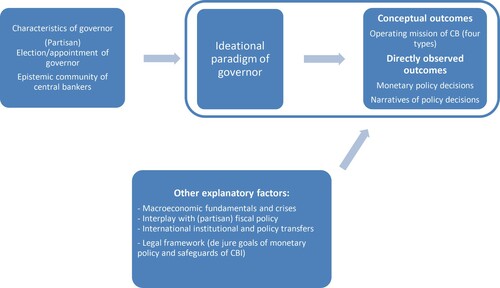

In this article, we demonstrate that within the scope of our case study, the operating mission of the CB – besides other factors () – systematically reflects the ideational paradigm of the central banker. Adding the operating mission as a previously missing concept clarifies a potential causal mechanism linking certain characteristics of the central banks and partisan politics to monetary policy decisions. While all central bankers considered in this study accept the CBI framework, we claim that the ideational paradigm of the central banker shapes how they translate the formal mission into an operating mission.

The ideational paradigm of the governor is a result of a complex interaction of factors, including life experiences and background, engagement in international networks, and the appointment process. Some understandings of CBI frame the central banker as an apolitical technocrat (see above on the conservative central banker and also Berger and Woitek (Citation2005); Rogoff (Citation1985)). A different line of research detects the influence of the educational or occupational background of the central banker on policy outcomes (Adolph Citation2013; Göhlmann and Vaubel Citation2007), as well as engagement in different international networks, as epistemic communities (Checkel Citation2005; Johnson Citation2016; Thomassen Citation2017).

We can also understand central bankers as public intellectuals who are embedded in ideational networks. Furthermore, the election or appointment process may also influence the ideational paradigm. CBI can also imply stronger incentives for patronage appointees of party politicians, as the exclusive partisan opportunity to shape independent agencies (Ennser-Jedenastik Citation2016). The ideational paradigm of the central banker therefore may vary according to party appointment, but the empirical findings from this article suggest a more nuanced variation in ideational paradigms that does not conform to simple partisan explanations.

While the causal explanations for the ideational paradigm are complex, we focus on the mechanism that links the governor’s ideational paradigm and the operating mission of the CB, as shown in . The establishment of this mechanism demonstrates that central bankers are agents of change who reform the CB’s mission as they “creatively exploit the polyvalence of ideas and the institutional tensions that these ideas create in pursuit of complex and multiple goals” (Jabko Citation2006, 40). Similarly, Ban (Citation2016:, 19) demonstrated the role of the domestic political elite in translating neoliberalism, which – rather than a single paradigm – is a “battle of ideas”. Rather than claiming that alternative factors and mechanisms do not matter, the evidence for the effect of ideational paradigms on operating missions demonstrates that central bankers have considerable room for manoeuvre when deciding on the goals of the central bank, even within constrained legal frameworks and other factors influencing monetary policy.

While formal rules remain largely stable over time, a change in leadership at a CB may bring about a new interpretation of the institution’s goals. So, in order to highlight the importance of the governor’s paradigm on the operating mission of the CB under his/her direction, we have to show how the governor’s ideas translate into observable action.

The conceptual notions (ideational paradigm; operating mission) are analytically separate, yet in reality they constitute two sides of the same coin: the views of the governor and strategic action derived from these views. Therefore, our aim in this qualitative study is to tease out this intertwined nature of policy paradigms and operating missions. If the proposed causal logic holds in light of our empirical analysis, it adds governor’s policy agency to the checklist of factors to reckon with in understanding monetary policy outcomes.

These factors will change from period-to-period as is the case of external constraints, such as IMF conditionality. We note that, especially for the 1990s, it is well-established in the international political economy literature that the strings attached to loan agreements by the IMF posed a distinct limitation on monetary policy. However, this did not prevent Surányi, the governor most relevant from this perspective, to take part in the preparation of a heterodox stabilisation package (“Bokros-csomag”) and otherwise adapt the operating mission in creative ways. In the post-financial crisis period the role of the IMF waned as the Orbán government repaid the IMF loans and increased its policy autonomy. Capital markets also posed constraints on policy-making, especially in periods of high inflation/interest rates and/or increasing external sovereign debt as a share of GDP.

III. Data and methods

The research question of this study concerns the factors influencing the type of the operating mission of the MNB in post-regime change Hungary. We argue that (1) there was a substantial variation in the operating mission of MNB over the years which had major consequences for monetary policy implementation and that (2) this variation was driven by the ideational dispositions of governors who displayed significant autonomy in formulating the operating mission under their leadership.

Our research design is focused on unearthing information that clarifies the mechanism through which the agency of CB leadership impacts monetary policy outcomes under the condition of CBI. This mechanism highlights the bureaucratic autonomy of governors in shaping the operating missions. Therefore, the variable to be explained concerns the type of operating mission adopted in the period of different CB governors. In some cases, they applied the “letter of the law” and adhered to prevailing international norms. In some cases, they did the opposite. This means, that there is significant variation in our outcome of interest which is worth explaining. Our detailed empirical data represents a unique opportunity to explore the connection between ideational paradigms and operating missions. While elements of the preferred operating mission, consisting of public policies and publicly held policy narratives, by any given central banker are inherently intertwined with the ideational paradigms that the governor adheres to, our data enables in-depth analysis of the connection between these two, which provides greater causal clarity than in previous studies.

The Hungarian case is a particularly appropriate context for this analysis. Foremost, the extensive external pressure for CBI and sound monetary policy wielded by EU accession (until 2004) and IMF conditionality (at later stages) makes it a least-likely case for the influence of domestic agency. Moreover, the high polarisation between political parties and public intellectuals in Hungary provides sufficient variation in partisan approaches and ideational paradigms of central bankers to test the nature of the influence of domestic factors. The availability of genuinely alternative approaches to macroeconomic policy provides the needed variation on our input variable, the ideational framework of the central banker.

An in-depth analysis of the Hungarian case relying on interviews with each MNB governor since 1991 (and vice governors from one period) enables us to investigate the first-hand accounts of the shifting mission of the Hungarian CB in the context of its historical trajectory. Specifically, we study the role of an often-neglected variable, the self-proclaimed mission of governors, and how these missions shift over time. We used semi-structured elite interviews in an attempt to disclose the motives that CB governors themselves deem important.

In a unique undertaking in studies of Hungarian central banking, our interviewees were György Surányi (governor 1990–1991 and 1995–2001), Péter Ákos Bod (governor 1991–1994), Zsigmond Járai (governor 2001–2007), Ferenc Karvalits (vice-governor 2007–2013), Júlia Király (vice-governor: 2007–2013) and György Matolcsy (governor: 2013–present). We refer to them collectively as “governors”. provides a summary of the leadership periods and background information on the governors in each period. It also includes the annual averages of the CBI score (see endnotes) and the exchange rate regime present during the respective governing terms.

Table 2. Summary of governors’ periods of the Hungarian National Bank since 1990.

The CBI score (Garriga Citation2016) is an index composed of weighted averages of several extant indices of de jure CBI scores, and ranges from 0 (least independence) to 1 (most independence).Footnote6 The most notable changes in Hungary’s scores occurred in 1991 and 2001, when successive Acts on the MNB consolidated, primarily, autonomous decision-making. In comparative terms, the 2001 Act brought Hungary close to the Bundesbank’s comparatively high score, which in 1998 increased from 0.69488–0.85650. Ainsley (Citation2017) reports that Hungary’s level of CBI falls within 1 standard deviation of the mean for the entire sample of 71 countries and this finding is unaffected by the appointment of Matolcsy in 2013 at the height of “illiberal” economic policy.

Our core methodology was qualitative content analysis (Schreier Citation2012), which allowed us to analyse how central bankers framed the mission of the bank in interviews. These interviews also provided insights into how central bankers evaluated critical issues during the tenure of their peers. We coded each central banker’s portrayal of the operating mission of the monetary authority according to the dimensions proposed in the previous section: along an international vs. national outlook and the adherence to an orthodox vs. heterodox economic ideology. This allowed us to identify the predominant framing of the CB’s operating mission in each interview. We also retained representative quotations in order to offer a more nuanced analysis of the respective ideational paradigms.

IV. Empirics

The Bod period (1991–1994)

In the early years of Hungary’s independent CB, the monetary authority engaged in activities beyond price stability. During transition this was likely a result of underdeveloped economic institutions and the CB’s attempt to fill the void of other roles. We detect an operating mission that is heterodox and adapted to specific needs of Hungary’s economy at the time, in particular supporting the development of a retail banking system. In this section, we provide evidence that this operating mission was not perfectly in line with the ideational position of the CB governor, Péter Ákos Bod.

The independent CB in Hungary was created with the first Central Bank Law in late 1991. Nevertheless, the substantive-operating mission of these years was a far cry from the narrowed down concept described in most CBI research concerning Western Europe. Bod was the governor from 1991 to his arranged, pre-term exit in 1994. He claimed that “in the early nineties, the MNB was involved in many more activities” vis-á-vis more developed monetary authorities.

According to the governor, this was not a choice: “We were forced to take care of many more tasks due to market or government failures.” This plethora of activities amounted to a “functionally overburdened” CB, according to Bod. This was not due to some gubernatorial strategy: “no banking supervision agency, no state treasury, no capital market institutions existed at that time.” Government bonds were actually issued by the MNB in lieu of a functional government agency. Similarly, giro activities were handled by the MNB. Bod recalls, that – despite the fact that IMF conditionality back in the 1980s called for the establishment of a two-tier banking system – retail banks were very much dependent on 6-month credit lines by the MNB due to their massive share of non-performing loans.

These undertakings were implemented not because of, but in opposition to the mission that had been envisaged for the newly independent CB. According to Bod, the intention was to create a “Bundesbank, only on a smaller scale”. The writers of the 1991 law (which did not include Bod, a minister for industry and commerce at the time) took the Bundesbank gesetz as a starting point. Potential ministers from the right-wing MDF party were even brought to Germany by the CDU before the 1990 election so that they could familiarise themselves with German-style macroeconomic governance.

In light of this pre-history, it should not come as a surprise that the new central bank law (adopted in December 1991) paved the way for a more restrictive formal mission than the actual operating mission in the first half of the decade. Having said that, even the formal mission cast a wider net than what would become the inflation targeting mainstream by the early 2000s. The brief exposition of the goals of MNB in the new law stipulated that external and internal threats to price stability should be weighted equally by decision-makers. Here, “external price stability” was understood as a reference to the exchange rate (then pegged in an adjustable manner to a basket of major currencies) and external balances.

In retrospect, Bod reflects on this dual goal by stating that “it turned out, it was too much”. But the understanding in central banking circles was that “internal” price stability should be given priority. As for the political mandate for monetary policy, according to Bod “there was none”. The operating ideology of Prime Minister Antall was of the old school conservative liberal mould: “He did not instruct me to do this or that – he just nominated me to do the job”. These quotations demonstrate a high potential influence of the CB governor to opt for prioritising internal or external price stability.

Many subfields of monetary policy underwent a gradual change: “We knew the central bank had to withdraw from financing retail banks eventually, and there was a rule in place that our involvement could not surpass that of 1.5 per cent of GDP”. But emergency loans were very much on offer as “no capital markets existed, no regime of bank resolution existed” and this is why the IMF gave a pass to Hungarian decision-makers. This is evidence of adjusting the goals of the CB to the national context as opposed to strict policy transfer.

The same held for CB ownership in domestic banks and the local branches of international conglomerates. In fact, “it was the leaders of international bank holdings who asked us to take a small stake in their banks” as they considered this an insurance policy in a developing market. Nevertheless, these stakes were sold on a pre-defined schedule that also accounted for market prices in timing the offerings. In this respect, according to Bod, the 1991–1994 period was the initial phase of a consensus that lasted until Matolcsy: “No one wanted to act like retail bankers.” Given the multidimensional transition taking place in Hungary, it is not surprising that the MNB adopted a more heterodox operating mission, despite a CB governor that supported a mainstream understanding of the role of CBs. The operating mission of the Bod period can, therefore, be classified as modernisation by virtue of structural features rather than the agency or ideational background of the governor.

The 2nd Surányi period (1995–2001)

In 1995, the Hungarian economy was in a dire situation with massive inflation, deteriorating currency value and looming state bankruptcy. It was in this context that the left-liberal Horn government adopted a stabilisation package, known as the Bokros package, named after its Minister of Finance, Lajos Bokros. MNB governor György Surányi was appointed by the Horn government and was also co-designer of this stabilisation package. Surányi’s perspective on central banking goals merges heterodox views with a clear awareness that much of the reality faced by central bankers is set from the international world. He thus fits the modernisation category presented earlier.

A key pillar of Surányi’s monetary policy approach was exchange rate targeting rather than inflation targeting. Following a fairly narrow band, monetary operations were directed at maintaining the stability and balanced the value of the Hungarian forint. This would serve, in Surányi’s view, the stability needed for (foreign) finance and the promotion of exports while limiting but not too heavily affecting the purchasing power for commodity imports. His decision to focus on exchange rate targeting supports the point, also apparent in the Bod interview, that the legal framework left open the choice to prioritise internal or external price stability, though they were formally supposed to have equal priority.

Another element in Surányi’s heterodox view is that he emphasises the importance of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy. For Surányi, “the central bank does have an obligation to coordinate with the other main type of economic policy: fiscal policy.” Without coordination monetary policy may lead to unintended consequences, possibly even effects contrary to those intended. From this point of view, Surányi was critical of the Matolcsy governorship because according to him there actually was little coordination. He argued: “This is very odd in Matolcsy's case because they come from the same government, but there is an unprecedented lack of communication between monetary and fiscal policies”.

From this perspective on the CB’s operating mission, Surányi was equally critical of both of his successors in the period of 2001–2013. He stated that: “In my view, there is a continuity over these 12 years in that – in a one-sided, doctrinaire fashion – they pursued the sacred inflation target, for better or worse.” He clearly distinguishes his approach to central banking from those of the governors that came after him.

As I see it, in the world and especially in Hungary, independence has been taken completely to the extreme. To such an extent that even in principle experts cannot state their opinion on monetary policy because they already consider that to be questioning the institution. It’s absurd.

Surányi had a clear view of how Hungarian monetary policy reacts to international effects. Regarding price stability, Surányi took a clear internationalist view by arguing that “we don’t need to worry about inflation because it is given, set from the outside”. This further clarifies his focus on external price stability, as exchange rate policy was a more feasible way to manage inflation, based on the assumption that international factors primarily drive inflation. Surányi referenced specific actors at the IMF who supported the more heterodox approach and told him so clearly. This further justifies classifying Surányi’s operating mission in the modernisation category.

The Járai period (2001–2007)

Zsigmond Járai, appointed by a right-wing government, presented a more restricted view of the MNB’s role. While being similarly internationalist as most Hungarian governors, Járai indicated a principled preference for the CB not to be concerned with fiscal policy developments, let alone to attempt to influence economic outcomes other than price stability. He also quite explicitly identified alternative operating missions supported by different CB governors. The operating mission of the MNB under his leadership clearly fit into our neoliberal category, which is highly consistent with Járai’s ideational approach evidenced by our interview with him.

His orthodox-internationalist perspective surfaced most clearly when Járai made a distinction between the views of his predecessor and those of himself:

There are two central bank schools in Hungary. One is Surányi's, which I think is wrong, and is based mostly on American practice […], a rather socialist economic philosophy that the central bank must influence the economy. On the other hand, [we have] those who [are related to] the European Central Bank system. [Those who believe] that the central bank must be independent. [For] monetary policy to pay attention to everything else, [that] comes next.

Nevertheless, despite his essentially orthodox views on independence and price stability, Járai proves less dogmatic than it might seem. In hindsight, most governors agreed the financial crisis reset the stage in terms of the primacy of disinflation. Similarly, Járai took a pragmatic approach indicating that CBs do need to adapt to shifting environments. He stated:

I am in favour of the [policy switch under Matolcsy]. I did not agree when [the previous leadership] did not change pace. If the world changes, monetary policy has to follow suit. […] From 2008, there was no inflationary threat […], deflation was the real challenge.

in my opinion the proper philosophy of central banking is that the central bank has its tasks, goals and it has to carry them out […] In my view, these [additional activities of the MNB after 2013] are not compatible with [the mission of the central bank].

The Simor period (2007–2013)

Our interviews from the Simor period were with Ferenc Karvalits and Júlia Király – they were appointed as members of the MNB board under a left-liberal government. They clearly fit into the neoliberal category, as they emphasised an orthodox and internationalist view of the CB’s operating mission.

Karvalits echoed Járai’s view of a more limited operating mission for the MNB and claimed that: “There are core activities, and the board has autonomy with respect to these core activities. It must not deal with other activities.” The discretion of the central banker is assumed to be low, as demonstrated by the statement: “The mission is established through law. The majority of the parliament, if they would like, can alter it”. Regarding the internationalist dimension, Karvalits spoke of central banks in general, often using plural, rather than referring to the MNB specifically. This implies a framing that assumes more universal laws of central banking, similar to Járai, rather than referencing national exceptionalism, as Matolcsy does.

In conformity with this restricted view, Karvalits reflects on Bod’s tenure as consistent with the MNB’s intended role. With regards to this period of stabilisation, which was direly needed in the early transition period, Karvalits commented that

a very important aspect was that there were no major institutional changes in Bod's time. He was quite aware of the need to focus the CB’s role on monetary policy. In the meantime, this deregulation and the shift towards [currency] convertibility devalued the [central bank’s] role as foreign exchange authority.

Based on our interviews (and interest rate voting data), there was some dissent in the leadership structure as to how closely the MNB should adhere to the tenets of inflation targeting with governor Simor and vice-governor Király considered to be a little more hawkish than our other interviewee from the period. According to Karvalits, who was in charge of the monetary policy area at MNB: “During the first year in office, with the team I inherited, I was on the same track” (referring to mainstream inflation targeting). “And then we had to learn our lesson” (the crisis).

After that, in my view, along with my staff, we were running a more nuanced policy regime. Central banks added to their previous, very much inflation targeting focused approach the priority of macro-financial stability, as something that they had to pay attention to (…). It has become a common knowledge in central bank circles – it was not a coincidence that for many central banks the mandate scope increased: with macrostability, sometimes with supervision. This was in contrast to the pre-crisis period when supervision was taken away from central banks.

Several other potential operating mission elements were more strictly off the table in this period. Programmes funding growth are fiscal in nature according to Karvalits and, therefore, CBs have no stakes in it. From the perspective of economics, this is due to the nature of the underlying factors of insufficient lending. Bank taxes are creating an unfavourable environment for lending, which cannot be countervailed by reduced interest rate loans offered by the CB. According to the former vice-governor the same applies to major educational initiatives or corporate social responsibility activities (see next section). From Karvalits’s perspective, the financial crisis clearly provided an impetus for greater bank supervision, but not a broadly heterodox approach to the CB operating mission. Therefore, a time period that could have represented a critical juncture for the MNB was not one, in large part due to the ideational commitments of the leadership to an orthodox and internationalist understanding of the CB.

The Matolcsy period (2013–2017)

In 2013, the right-wing supermajority Fidesz government appointed Matolcsy, then Minister of National Economy, as MNB governor. In conformity with the government’s interventionist and self-declared “unorthodox” economic policies – varyingly conceptualised as, for instance, financial nationalism (Johnson and Barnes Citation2015) or authoritarian capitalism (Scheiring Citation2020) – Matolcsy redesigned the operating mission of the MNB. In this sense, Matolcsy’s approach mirrored the international move towards unconventional policy innovations such as quantitative easing (QE) programmes. At the same time, however, Matolcsy’s heterodoxy was deeply embedded in a nationalist understanding related to the ongoing transformation of Hungary’s financial sector and economy more broadly.

Drawing himself this parallel between his two governing positions and defending the Hungarian bond purchasing programme in reference to the American Fed’s QE, Matolcsy indicated that

when the fiscal and economic policies I followed were said to be unorthodox in Hungary, they were mentioned in a derogatory manner. In fact, any reference to unorthodox [policies] in the central bank world was a laudatory praise, [indeed] meaning […] a radical turn.

We brought all this with us [from the Ministry of National Economy]. This was the character of the new monetary policy […] you have to be in harmony with the new developments of global central banking. Well, we were in possession of this character when we came here. We found allies, experts and 70–80% of our programme was ready.

One of the interventions extending the role of the MNB is the nationalisation of Hungarian retail bank MKB (the fifth largest in 2014), previously owned by the German BayernLB. This nationalisation should be perceived in light of the government’s repeatedly stated objective to reduce the foreign ownership of Hungary’s banking sector to below fifty percent. Matolcsy justified this unconventional action stating:

The government asked us to take part in [this project]. The MNB has three mandates: price stability, financial stability and supporting the economic policy of the government. [Therefore], we had a duty to take part [in rescuing MKB]. But of course, we performed this duty because the resolution of MKB […] was a targeted monetary policy instrument […] The importance of [nationalising and re-privatizing] MKB does not measure up to that of Funding for Growth, but it is a symbolic issue, nevertheless. It shows the radical turn in monetary policy and financial supervision.Footnote7

V. Discussion

Our findings point to the critical role of agency, as the ideational paradigms of the independent governors moulded the resulting CB mission. Needless to say, along with many factors established in the literature, changing conditions in the political economy do shape central bankers’ perspectives. Yet the ideational perspectives of a succession of CB governors display a fairly wide variety of views even in our simple, two-dimensional framework of economic paradigm and international outlook. These ideational factors should not be discounted when discussing monetary policymaking even in a region on the semi-periphery of global finance such as CEE.

These findings matter because differences in the operating mission followed in each period were translated to strongly diverse policies. Unlike Adolph’s assumption that central bankers have an “illusion of consensus” (Adolph Citation2013, 20), the interviews with Hungarian National Bankers reveal a keen awareness of the alternative missions of the CB and the deviation between central bankers in adherence to a mission. We neither detect reservations about acknowledging these alternatives, nor affiliating their own tenure with a specific approach. revisits the operating mission types formulated above and positions the governor periods according to these mission types.

Table 3. Varieties of central bank operating missions with MNB examples.

Our interviews highlighted the essentially outward looking nature of Hungarian central banking. Most governors positively referenced the Bundesbank and ECB, sometimes going as far as declaring that the aim with creating the independent MNB was to establish a “mini-Bundesbank” (Bod). Nevertheless, the realities of the economic transition (Bod) and the idiosyncratic thinking of the governor (Surányi) allowed for significant deviation from the emerging norm of price stability and inflation targeting.

By the 2000s Hungarian central bankers held a closer line with the now solidified mainstream neoliberalism (Járai, Simor), even if the crisis made some corrections necessary (Karvalits). The emergence of a new, heterodox mainstream as reflected in policies of QE and negative real interest rates in advanced economies by the late 2000s, paved the way for more out-of-the-box thinking on the semi-periphery as well. Matolcsy applied these new tenets with a decidedly nationalist flavour which highlighted the importance of (at least temporary) national ownership of big retail banks and major lending programmes.

Our empirical analysis reveals the self-perception of central bankers as public intellectuals with significant room to manoeuvre. This joins with other literature that detects a significant role for intellectuals, such as in shaping the EMU (Dyson and Maes Citation2017). While the influence of the neoliberal paradigm has been explored extensively, we emphasise the importance of alternative paradigms. In fact, we may even detect a Polányian countermovement within the circle of public intellectuals whereby the dominance of the neoliberal economic paradigm in the mid-1990s generated a reactive alternative paradigm in Hungary that was particularly viable in the wake of the global financial crisis (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2019; Polanyi Citation1944). For example, from 2010, Hungary embarked on a nationalist trajectory to both increase fiscal autonomy and foster domestic banking ownership with interventionist policies such as a direct banking levy on the assets of large, that is mainly, foreign banks. The MNB supported this backlash against foreign finance, a key feature of the previously dominant neoliberal model.

Our findings confirm that “agents transform institutions and policies from the inside out” (Adolph Citation2013, 9). However, Adolph focuses on the careers of central bankers as a proxy for their conservatism in a quantitative analysis of a large number of central bankers. While career may be an effective proxy, we understand the core determinant for shifting CB missions to be the ideational paradigm to which the central banker subscribes, which in the Hungarian case at least tends to be more stable than career profile.

Finally, our study indirectly showed the limitations of some alternative explanations of changing operating missions, such the party politics thesis which focuses on appointments as the means of keeping central banks in check. While one might make the claim the financial nationalism of the Matolcsy era was all due to Orbán, it is important to note that the Prime Minister is a law school graduate who seldom intervenes directly in matters of economic policy. Ever since the mid-1990s he relied on two trusted advisors, Mihály Varga and György Matolcsy, whom he always kept close even as he nominated technocrats (such as Zsigmond Járai) to top positions. As a representative of Orbán’s government, Varga often clashed with governor Matolcsy on their assessment of the outlook for Hungarian growth or the valuation of the Hungarian forint. At the yearly meeting of Hungarian economists he warned of an end to the “golden age” of the growth period of the late 2010s to which Matolcsy reacted swiftly: “isn’t over, it’s just beginning … and will last for decades”. Similar controversial points between Orbán's government included the exchange rate and even innovation and education policy.

It was also Matolcsy, not Orbán or Varga who manufactured the partial occupation of MNB before Simor’s term expired. Matolcsy’s fingerprints are all over the policy minutiae of financial nationalism in Hungary (Sebők and Simons Citation2021) and in the mission creep of the MNB under his institutional entrepreneurship (Sebők Citation2018). While appointment is a crucial tool of governments for controlling monetary policy, the appointees can use CBI to shape and implement their own strategy.

Matolcsy’s idiosyncratic operating mission is all the more interesting as in Hungary the Bundesbank served as the prototype for Bod during the transition period – even as circumstances did not allow for a single-minded pursuit of price stability with, for instance, no sovereign bond market to speak of. Yet the Járai and Simor periods showed all the elements associated with an operating mission that strictly focused on CBI (here: no coordination with fiscal policy), price stability and inflation targeting (this interpretation is corroborated by Figure 5 in Ainsley (Citation2017)’s work). The explanation of how Surányi’s and Matolcsy’s period deviated from this “norm” within the framework of CBI is one of the main contributions of this study.

VI. Conclusion

In this article we developed a conceptual framework for the operating mission of an independent CB and traced changes in the operating mission of the MNB over its recent 27-year history. Our aim was to investigate the influences that drive mission shift. By relying on unique interview data with representatives of each MNB leadership since the establishment of the independent monetary authority we created a valuable platform for studying the interaction of international norms and policy transfers, domestic politics and economic ideology.

We set out to explain the significant variations in CB policy emphases against a relatively stable intellectual environment shaped by CBI, the goal of price stability and the inflation targeting regime (from 2001). What we found is that our conceptual innovation of the operating mission is capable of accommodating the great diversity in CB policy decisions in post-regime change Hungary vis-á-vis what one would expect based on a seemingly stable formal mission anchored in price stability. Our findings point to the critical role of policy agency, even as the diffusion of the paradigm of CBI and that of inflation targeting led to increasingly harmonised formal missions. Interview evidence shows that the individual approaches of particular governors moulded the resulting operating mission of the CB. This suggests significant room for manoeuvre even in the face of dominant international norms.

With various paradigm shifts noticed, the most significant occurred once Matolcsy became governor in 2013. His appointment translated into an operating mission which was most overtly nationalistic and also the most unabashed experimentation with heterodox policies, thus deviating most substantially from the orthodox operating mission than during any of the previous leaderships. Fidesz’s ascendency to power and the economic crisis conditioned this deviation, yet Matolcsy’s re-interpretation of rules and decision-making autonomy effectuated the financial nationalist turn in MNB policies.

This case also offers one of the clearest indications of the substantial role of governors in shaping monetary policy. For a full account of the monetary policy developments of newly democratised Central-Eastern European countries, this element is just as important as international influences and partisan politics. We presented notable similarities where one would not expect much (such as between the right-wing appointee Járai and the left-wing appointee Simor). The study also shows how this “consensus” of the 2000s was supplanted by the financial nationalism of Matolcsy. We presented how Surányi argued that monetary and fiscal policy should be coordinated while Járai and Simor said it would not (and they did not, in fact, compromise on this).

Considering international politics, it was notable that Simor-led Monetary Council and the one led by Matolcsy reached very different conclusions as to what the CB is about and what it should be doing in near-identical post-crisis environments (both in terms of international/EU law and macroeconomics conditions hallmarked by low interest rates). As we noted above, Matolcsy also regularly clashed with Orbán's finance minister, Mihály Varga or made controversial statements related to the policies of the cabinet.

Future work could apply a comparative framework to studying CB missions. Here, our expectation is that the operating missions of CBs in Europe are indeed not entirely independent from each other. For the CEE region in particular, policy transfer related to CB operating missions could well be present considering the broader “learning effects” the Hungarian case posed to countries like Poland.

Further, the presence of banking nationalism in many Western European countries may very well stimulate the rise of financial nationalism in other countries. For example, despite the maintenance of banking nationalism there, internationalisation of central banking emerged in the case of the ECB through acceptance of German exceptionalism. These processes may take place in parallel to the domestic application of banking nationalism. Exploring these interdependencies portends to be a fruitful line of research to apply our framework in a comparative perspective.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sándor Kozák and Bálint Pataki for their research assistance and are grateful for helpful comments and suggestions from participants in the EPSA and CES panels, as well as from anonymous reviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Miklós Sebők

Miklós Sebők is a Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Institute for Political Science at the Centre for Social Sciences, Budapest, Hungary.

Recent publications:

2020: The Multiclass Classification of Newspaper Articles with Machine Learning: The Hybrid Binary Snowball Approach. (co-author Zoltán Kacsuk). Political Analysis. 2020. (First view)

2020: From State Capture to ‘Pariah’ Status? The Preference Attainment of the Hungarian Banking Association (2006-2014). (co-author Sándor Kozák) Business and Politics. 2020 (First view)

2019: Electoral Reforms, Entry Barriers and the Structure of Political Markets: A Comparative Analysis. (co-authors: Attila Horváth, Ágnes M. Balázs. European Journal of Political Research, 58:(2) pp. 741-768. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12309

2018: Punctuated Equilibrium In Democracy and Autocracy: An Analysis of Hungarian Budgeting Between 1868 and 2013. (co-author: Tamás Berki) European Political Science Review, 10:(4) pp. 589-611. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000115

2018: Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Mission Creep of the National Bank of Hungary. In: Caner Bakir, Darryl S L Jarvis (eds.) Institutional Entrepreneurship and Policy Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 243-278. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70350-3_10

Kristin Makszin

Kristin Makszin is an Assistant Professor of Political Economy at Leiden University, The Netherlands.

Recent publications:

Barta Zs. & Makszin K.M. (2020), The politics of creditworthiness: political and policy commentary in sovereign credit rating reports, Journal of Public Policy .

Schneider C.Q. & Makszin K.M. (2014), Forms of welfare capitalism and education-based participatory inequality, Socio-Economic Review 12(2): 437-462.

Jasper Simons

Jasper Paul Simons is a doctoral researcher at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy.

Notes

1 The goal of monetary policy according to the MNB Act of 2001 was “to achieve and maintain price stability. (2) Without prejudice to its primary objective, the MNB shall support the economic policy of the Government, using the monetary policy instruments at its disposal.” The legal mandate of the MNB as formulated in the MNB Act of 2013 states: “The primary objective of the MNB shall be to achieve and maintain price stability. Without prejudice to its primary objective, the MNB shall support the maintenance of the stability of the financial intermediary system, the enhancement of its resilience, its sustainable contribution to economic growth; furthermore, the MNB shall support the economic policy of the government using the instruments at its disposal.” These additional elements of the goal structure vis-á-vis the Act of 2001 had originally been specified as “basic tasks” or as support mechanisms for the erstwhile Hungarian Financial Supervisory Authority (the portfolio of which was subsumed into MNB in 2013).

2 According to the Federal Reserve (FED) Act the FED conducts monetary policy “so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”. https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section2a.htm

3 Such as full employment, output stabilisation (instead of price stabilisation), public and/or private debt reduction with instruments such as monetary financing (e.g. helicopter money) or foreign capital reserve outflow limitation by installing capital controls.

4 Also, the variation in ideological views may be scalar, rather than categorical, from highly orthodox views to more pragmatist ones. However, these types of refinements may only be necessary for a larger-N study.

5 It is important to note that this framework only applies to the period of the CBI-inflation targeting consensus. For instance, in the 1930s the international consensus was arguably pointing towards protectionism rather than towards international integration and the free flow of capital.

6 We composed annual averages of Garriga’s (Citation2016) CBI weighted index (lvaw_garriga). All information available at: https://sites.google.com/site/carogarriga/cbi-data-1 but for the precise composition of the weighted index see: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6aTJWE_InwvRWVkYnBJX2drNGM/view

7 The Funding for Growth programme was another unconventional measure to increase credit for small and medium-sized enterprises by highly favourable regulated borrowing conditions.

8 Based on Zoican (Citation2009).

9 Including 2001, the year of the adoption of a new MNB Law.

10 Since András Simor was not available, we interviewed two of his vice-governors.

11 Latest data available is for 2012.

12 In practice the MNB followed the euro as a reference currency, despite its formal free float regime, see https://www.mnb.hu/en/monetary-policy/monetary-policy-framework/exchange-rate-regime

References

- Adolph, C. 2013. Bankers, Bureaucrats, and Central Bank Politics: The Myth of Neutrality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ainsley, C. 2017. “The Politics of Central Bank Appointments.” The Journal of Politics 79 (4): 1205–1219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/693097.

- Baerg, N., J. Gray, and J. Willisch. 2020. “Opportunistic, not Optimal Delegation: The Political Origins of Central Bank Independence.” Comparative Political Studies.

- Ban, C. 2016. Ruling Ideas: How Global Neoliberalism Goes Local. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berger, H., and U. Woitek. 2005. “Does Conservatism Matter? A Time-Series Approach to Central Bank Behaviour.” The Economic Journal 115 (505): 745–766.

- Bernhard, W. 1998. “A Political Explanation of Variations in Central Bank Independence.” American Political Science Review 92 (2): 311–327.

- Binder, C. 2020. “De Facto and de Jure Central Bank Independence.” In Populism, Economic Policies and Central Banking, edited by E. Gnan, and D. Masciandaro, Vol. 2020/1, 129–136. Vienna: SUERF.

- Bodea, C., and R. Hicks. 2015. “Price Stability and Central Bank Independence: Discipline, Credibility, and Democratic Institutions.” International Organization 69 (1): 35–61.

- Bohle, D., and B. Greskovits. 2019. “Polanyian Perspectives on Capitalisms After Socialism.” In Capitalism in Transformation: Movements and Countermovements in the 21st Century, edited by R. Atzmüller, B. Aulenbacher, U. Brand, F. Décieux, K. Fischer, and B. Sauer, 92–104. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Checkel, J. T. 2005. “International Institutions and Socialization in Europe: Introduction and Framework.” International Organization 59 (4): 801–826.

- Crowe, C., and E. E. Meade. 2008. “Central Bank Independence and Transparency: Evolution and Effectiveness.” European Journal of Political Economy 24 (4): 763–777.

- Dwyer, J. H. 2012. “Explaining the Politicization of Monetary Policy in Japan.” Social Science Japan Journal 15 (2): 179–200.

- Dyson, K., and I. Maes. 2017. Architects of the Euro: Intellectuals in the Making of European Monetary Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L. 2016. “The Politicization of Regulatory Agencies: Between Partisan Influence and Formal Independence.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26 (3): 507–518.

- Epstein, G. A., and E. Yeldan. 2009. Beyond Inflation Targeting: Assessing the Impacts and Policy Alternatives. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Epstein, R. A. 2008. In Pursuit of Liberalism: International Institutions in Postcommunist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

- Fischer, S. 1995. “Central-bank Independence Revisited.” The American Economic Review 85 (2): 201–206.

- Gabor, D. 2010. Central Banking and Financialization: A Romanian Account of How Eastern Europe Became Subprime. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garriga, A. C. 2016. “Central Bank Independence in the World: A New Data Set.” International Interactions 42 (5): 849–868.

- Göhlmann, S., and R. Vaubel. 2007. “The Educational and Occupational Background of Central Bankers and its Effect on Inflation: An Empirical Analysis.” European Economic Review 51 (4): 925–941.

- Hall, P. A. 1989. The Political Power of Economic Ideas: Keynesianism Across Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jabko, N. 2006. Playing the Market: A Political Strategy for Uniting Europe, 1985–2005. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Johnson, J. 2016. Priests of Prosperity: How Central Bankers Transformed the Postcommunist World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Johnson, J., and A. Barnes. 2015. “Financial Nationalism and its International Enablers: The Hungarian Experience.” Review of International Political Economy 22 (3): 535–569.

- Macartney, H. 2010. Variegated Neoliberalism: EU Varieties of Capitalism and International Political Economy. London: Routledge.

- Marcussen, M. 2005. “Central Banks on the Move.” Journal of European Public Policy 12 (5): 903–923.

- Maxfield, S. 1998. Gatekeepers of Growth: The International Political Economy of Central Banking in Developing Countries. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- McNamara, K. 2002. “Rational Fictions: Central Bank Independence and the Social Logic of Delegation.” West European Politics 25 (1): 47–76.

- Mosley, L. 2005. “Globalisation and the State: Still Room to Move?” New Political Economy 10 (3): 355–362.

- Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation.(1957). Estados Unidos de América, Beacon Paperback Edition.

- Rogoff, K. 1985. “The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 100 (4): 1169–1189.

- Scheiring, G. 2020. The Retreat of Liberal Democracy: Authoritarian Capitalism and the Accumulative State in Hungary. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Los Angeles: SAGE publications.

- Schwartz, A. J. 2009. 1 Boundaries Between the Fed and the Treasury.

- Sebők, M. 2018. “Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Mission Creep of the National Bank of Hungary.” In Institutional Entrepreneurship and Policy Change: Theoretical and Empirical Explorations, edited by C. Bakir, and D. Jarvis 243–278. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sebők, M., and K. Makszin. 2018. “Views from the Top: Transition and the Changing Mission of the Hungarian Central Bank.” Paper presented at the Council for European Studies, Columbia University.

- Sebők, M., and J. Simons. 2021. How Orbán Won? Neoliberal Disenchantment and the Grand Strategy of Financial Nationalism to Reconstruct Capitalism and Regain Autonomy. under review.

- Thomassen, E. 2017. “Translating Central Bank Independence Into Norwegian: Central Bankers and the Diffusion of Central Bank Independence to Norway in the 1990s.” Review of International Political Economy 24 (5): 839–858.

- Zoican, M. A. 2009. The Quest for Monetary Integration–the Hungarian Experience.