ABSTRACT

This article argues that interpreting Russia's conservatism exclusively as a top-down phenomenon has obscured the possibility that there might exist a grassroots conservatism founded on very different bases than the state narrative, and which predates the state's embrace of conservatism. It thus takes a fine-grained view of Russians' conservative values by looking at (1) the existence since the 1990s of a situational conservatism that preceded the state's “conservative turn”; (2) the fact that conservative attitudes are shared by almost all post-socialist countries; (3) the rise of moral conservatism and its limits; (4) attitudes toward the Church, which encapsulate the gap between discourse and practice; and (5) the polarisation of Russian society into conservative and non-conservative constituencies.

The literature on values and ideologies in Russia has largely been shaped by discussions about the nature of the political system and the conceptual framework of hybrid regimes. The notions of authoritarianism or autocratization have served as the main conceptual background for discussing Russia’s so-called conservative turn around 2012. This conservative turn has indeed generated an increase in repressive measures against civil society (the foreign agent law, the Dima Yakovlev law denying U.S. citizens the right to adopt Russian children, the anti-“gay propaganda” law, the anti-blasphemy law, etc.) (Wilkinson Citation2014), measures that have increased in 2021 as the regime grows increasingly worried about the loyalty of some parts of the population. While scholars disagree on whether this “conservative turn” has genuine ideological content (e.g. Robinson Citation2019) or is merely an empty shell used by the regime to secure its legitimacy (e.g. Pomerantsev Citation2014), very few studies have looked at society’s reception of state-produced conservative discourses and at its own production of values.

Ignoring the demand side of conservatism limits our ability to capture how the social contract has been negotiated in Russia. The regime’s cultural hegemony is not a unidirectional, top-down process that shapes a passive, receptive public opinion “brainwashed” by media “propaganda.” On the contrary, we know that the regime has been spending an impressive amount of money on in-depth studies of public opinion, to the point that Russia has been described as a “rating-ocracy” (Shmevel Citation2007) in which regime politics sometimes hews to public opinion and enshrines status quo attitudes rather than shaping them.

And indeed, as we learn from the Foucauldian notion of governmentality, the governed internalise power relations and gain their own agency therein (Foucault Citation1997). The field of communication studies has developed the notion of cocreational mechanisms to capture the permanent tension and adjustment inherent in mediated power relations (Botan Citation2018). In criticising the notion of cultural hegemony, Herzfeld (Citation1987) insists that the elite and ordinary people have shared values. More recently, von Haldenwang (Citation2017) has conceptualised a dual process of legitimation: popular legitimation of government performance (the “demand cycle”) and legitimacy claims made by rulers (the “supply cycle”) need to meet at some point. Power, then, is the constant renegotiation of demand and supply cycles; and yet, as von Haldenwang explains, empirical research to date “has largely ignored the demand cycle” (Citation2017, 269).

The lack of studies of the demand side has limited our ability to interpret Russia’s conservatism as a bottom-up as well as a top-down phenomenon, obscuring the possibility that there might exist a grassroots conservatism founded on very different bases than the state narrative, with different nuances, and which perhaps predates the state’s embrace of conservatism. Only Russian-language scholarship has begun to explore this issue, using a range of sociological surveys to capture what conservatism may mean at the societal level (Byzov Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2019, and a summary in English 2018; Magun and Rudnev Citation2010 and Citation2012; Shcherbak and Ukhvatova Citation2018).

Here, I turn the focus to citizens’ agency, looking at conservatism not as an ideology displayed by the Kremlin but as attitudes and practices observable at the societal level. I avoid linking conservatism to political features such as patriotism and loyalty to the regime, which have already been well studied (Hale Citation2018; Goode Citation2016, Citation2021). Instead, I focus on moral conservatism – that is, a commitment to values presented as traditional in their view of the moral order, from family structures and sexuality (abortion and heterosexuality, but also the rejection of medically assisted procreation) to religion (namely, adhering to the majority religion historically associated with the country).

I do not include the notion of nation, as in Russia the experience of being a multiethnic nation has modified the way in which the search for ethnic homogeneity is discussed. However, I add to family structures, sexuality, and religion the notion of punitiveness. Although this topic has thus far been absent from studies of Russia’s conservatism, the literature on the relationship between conservative views and punitiveness has been well developed for the case of the United States (see, for instance, Silver and Silver Citation2017), where research has shown that the increased punitiveness of public opinion since the 1950s has influenced the rise of mass incarceration (Enns Citation2014). Like the US, the Soviet Union had a high incarceration rate, with about 10% of the Soviet population passing through the zona (the Russian term used to describe the carceral system as a whole) in one way or another. Even if Russia is now acting to reduce its prison population – which has shrunk from over one million in 2000 to 523,000 in 2020, according to the World Prison Brief (Citation2020) – a culture of punishment still exists and should be part of our discussion of conservative values.

To disentangle the relationship between top-down and bottom-up conservatism, I take a fine-grained view of Russians’ conservative values, looking at (1) the existence since the 1990s of a reactive conservatism that preceded the state’s “conservative turn”; (2) the fact that conservative attitudes are shared by almost all post-socialist countries, confirming that they are a structural feature not entirely dependent on elite production; (3) the rise of moral conservatism and its limits; (4) attitudes toward the Church, which encapsulate the gap between discourse and practice; and (5) the polarisation of Russian society into conservative and non-conservative constituencies.

In the process, I deploy various surveys conducted in Russia over the years. These come primarily from the Levada Center, as well as, to a lesser extent, from VTsIOM, FOM, and international surveys such as the European Values Survey and Pew Research Center studies. The Levada Center regularly asks values-related questions in its omnibus, which is administered to a representative sample of about 1600 respondents. I also add the LegitRuss survey, administered by VTsIOM to 1500-person nationally representative sample in April-May 2021 as part of a Research Council of Norway-funded project on values-based legitimation in Russia. Footnote1

A reactive conservatism

Whereas other ideologies have more fixed doctrinal content, conservatism is a situational ideology that defines itself mostly in opposition to what is seen as progressive in specific cultural contexts and at specific times: it defends established institutions and value sets against those who wish to modify them too radically or rapidly (Huntington Citation1957). Conservatism has thus evolved over time with the meaning of “progress,” taking on multiple faces and directions depending on the context in which it develops (Fawcett Citation2020).

Yet despite this flexibility, conservatism still has an identifiable philosophical core: it believes that humanity shares ontological features that cannot easily be challenged or denied by individual will, and that identity (national, sexual, and gender) is not purely a social construct that can be changed if an individual feels dissatisfied with it. It therefore believes in some forms of customs, traditions, and hierarchical order and maintains a pessimistic view of human nature. Beyond that, it evolves dramatically depending on the context: conservatism in the US, for instance, has historically favoured free markets and condemned state interference, whereas Russian conservatism supports state intervention into the economy.

Central to our analysis is this duality of conservatism as both an unreflective reaction against changes and a reflective doctrine about human ontology. The first conservatism expresses a reaction against the radical and rapid transformations that Russia experienced in the 1990s and that structurally altered society: it has been a call for slowing down the pace of evolution to allow for adaptation. This conservatism reflected, above all, Russians’ disillusionment with the market economy: in the 1990s, three-quarters of respondents felt that the market economy had increased the disparity between the rich and the poor, while two-thirds viewed it as having complicated their daily lives rather than improving them (Fedorov, Baskakova, and Zhirikova Citation2017).

This reactive conservatism reflected a desire for stability and normalisation, not necessarily a rejection of the changes themselves. The VTsIOM Center, then led by Yuri Levada, and later the Levada Center captured this need for predictability and stability. Over three decades, the share of respondents who did not feel confident about the future (50%–60%) always exceeded the share of those who did (40%–45%), with the exception of a short period between 2010 and 2012 and in the first months of 2014 (Levada Center Citation2008, Citation2015a).

As shows, Russians’ main feelings have been evolving in waves, with a peak in optimism in the late 2000s-early 2010s, a decrease in the years following the 2014 war with Ukraine, and then a progressive improvement (the data presented here stopped before the COVID-19 pandemic). In 2018, people were more tired and indifferent than in 2014 and had more fear and despair, but they also had more hope, more trust in tomorrow, and a greater sense of responsibility for what is happening in the country. That being said, almost all the 2018 numbers are more pessimistic or negative than during the “happy years” of the late 2000s.

Table 1. Levada Center – Russians’ main feelings, 2003–2018. Answer to the question “Which feelings appear and reinforce among people around you these last years?” (multiple answers possible).

Politically, these conservative attitudes largely translated in the 1990s into voting for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (24 million votes in the presidential elections of 1996, or 32% of the total; 15 and 16 million votes in the 1995 and 1995 legislative elections, or 22% and 24%, respectively) and Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democratic Party of the Russian Federation (12 million votes in the 1993 legislative elections, or 23% of the total) (Colton Citation1996; Hough, Davidheiser, and Lehmann Citation1996). Both parties advanced a sophisticated ideology that went beyond situational conservatism, but their electoral support was mostly expressing a popular reaction to changes. Soon after the arrival in power of Vladimir Putin, Byzov (original text 2002, English translation 2018, 41) observed what he called a “neoconservative wave,” predicting a future “‘conservative revolution’ with the creation of traditionally Russian dominant ideas.” And, indeed, the presidential party United Russia gradually captured this conservative vote, turning it into one of the cornerstones of Putin’s popularity and the party’s electoral support in the “deep” country. The regime has also contributed to reinforcing the vision of the late Soviet Union as a golden age of stability, a myth built against the backdrop of the turbulent 1990s, now erected as the main counter-example for the country (Malinova Citation2021).

Russians’ reactive or situational conservatism has been well captured by the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map,Footnote2 which identifies two main value axes: survival versus self-expression and traditional versus secular/rational values. On this dual scale, which measured these values from 1981 to 2015 (and began measuring the post-Soviet space in 1991), Russians were historically high on survival and secularity/rationality. Although they have gradually moved toward both more self-expression and more traditional values, they have remained in the survival and secular/rational quadrant.

Using the third wave of the European Values Survey from 2006 to 2007, Magun and Rudnev (Citation2012) confirm that Russians have a high rate of “conservation,” defined as security, conformity, and tradition (the contrary notions being independence, stimulation, and hedonism). Of the 20 countries selected by the authors, Russians exhibit the highest level of “security” values, find themselves in the middle on “conformity” and “tradition,” and rank particularly low on “risk and novelty.” However, in terms of “openness to change” versus “conservation,” Russia is basically the same as many other Western and Central Europe countries. The only value on which it clearly stands out is preference for “self-enhancement” (power, wealth, achievement) over “self-transcendence” (universalism and benevolence), probably a product of what had then been two – and is now three – decades of liberal reforms that had shrunk the welfare state and eroded horizontal ties.

These two datasets have confirmed the presence of a situational conservatism – a spontaneous and unreflective reaction of conservation and survival in a time of rapid changes.

Conservative attitudes as a post-socialist feature

This reactive conservatism is by no means specific to Russia. Indeed, it appears to be common to all post-socialist countries. It largely shapes the persistent divide between Western Europe and Central and Eastern Europe (with Greece falling into the latter category). A Citation2018 Pew Research Center survey of 34 European and Eurasian countries confirms that Russians’ views are in no way specific, suggesting that they are not the result of recent laws and discourses promoting “traditional values,” but rather are inscribed into the larger societal context of post-socialist societies. Within the Central-Eastern European bloc, Russia is rarely the most conservative: it is almost always surpassed by Greece, Armenia, and Georgia and regularly by many Balkan countries, as well as by Poland on some issues.

On the importance of religion (Evans and Baronavski Citation2018), Russia is quite equally divided: 57% consider it somewhat important, while 40% do not (far more than in the Caucasus, the Balkans, or Poland); 50% favour the separation of church and state, while 42% believe that the government should support religious practice. While the gap between believers and practicing adherents is high across Europe, it is particularly visible in Russia. The number of practicing adherents remains among the lowest in the Central-Eastern European region: 15% say religion is important in their lives, 17% that they go to church regularly, and that they pray every day. Russia ranks only 20th in terms of religious devotion over 34 countries surveyed.

On the importance of ancestry and sharing national identity, Russia again finds itself somewhere in the middle for the region, with 73% considering this important – less than in many Central European and Balkan countries. But Russia falls into the lower half on abortion: 56% are opposed and 36% systematically in favour. Russia reaches the highest levels in Europe only on one issue, same-sex marriage, which garners 90% opposition, a figure surpassed only by Georgia and Armenia.

The Pew comparative survey reveals several points of note. First, the phenomena of “conservatism” and “traditional values” are shared by the whole post-socialist space, including countries with pro-Western liberal governments like the Baltic states, Georgia, and Slovenia, which implies that state policies are not the main driver of this value set. Second, hardline moral conservatives are to be found mainly in small countries marked by a patriarchal and more culturally homogenous culture, such as Armenia, Georgia, and Greece, as well as Poland, where Catholicism is particularly influential. Compared to that group, Russia remains quite liberal, with the notable exception of homophobia; it has been shaped by its progressive Soviet past on issues such as abortion, divorce, and women’s rights, as well as by its multinationality and multiconfessionality.

The rise of moral conservatism and its limits

A second set of data specifically devoted to Russia gives us some insights into the second type of conservatism: the belief in certain ontological features that, applied to morality, prompt criticism of individual emancipation from traditional norms. I focus here on issues related to the definition of family/gender/sexuality and religion, as well as, briefly, to punitiveness.

Over time, Russians have, for instance, become less tolerant of abortion (see ). Yet this rise is not among those pushing for a full ban but among those who want it to be authorised only in some circumstances (medical and socioeconomic). These respondents would also like to see an increase in education about abortion rather than the criminalisation thereof (Levada Center Citation2015b). Conducted in 2021, the LegitRuss survey found almost equal support for and against abortion (respectively 46% and 47%), showing a quite polarised society on that issue.

Table 2. Levada Center – Views on abortion, 1998–2015.

The same trend is visible on the issue of divorce, with a slow rise in the proportion of respondents condemning divorce. ().

Table 3. Levada Center – “Do you agree or disagree that if a couple cannot solve its family issues, divorce is the best solution?” 2002–2018.

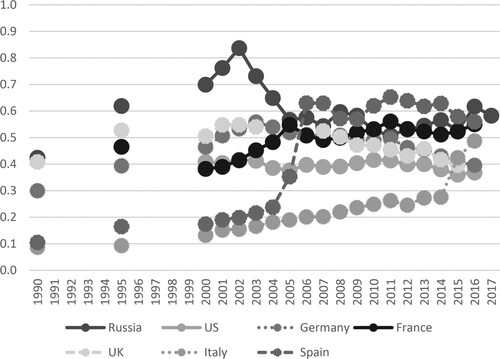

Yet on both these issues, the gap between attitudes and behaviours is important. Although conservatism may prevail discursively, actual behaviour tends to be far more liberal, especially when it comes to practices inherited from the Soviet era. For instance, even though an increasing number of Russians describe divorce as reprehensible in public opinion polls, it remains fairly common: Russia’s ratio of marriages to divorces is in line with the European average (see ). Vladimir Putin even divorced his spouse while in office, a risk no American president would take. Moreover, people across the country largely accept common-law relationships and single motherhood (Levada Citation2018a).

Figure 1. Russia’s “normalisation”: Marriage-to-divorce ratio, 1990–2017. Source: World Values Survey.

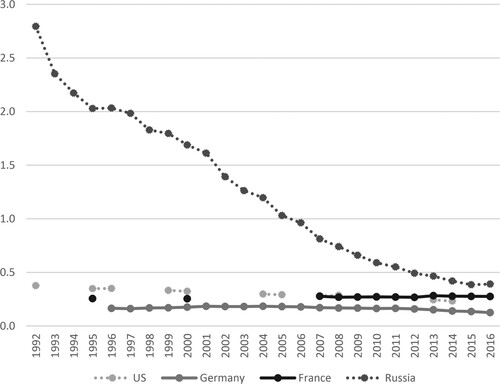

On abortion (see ), there has been a marked change in practice: in the past thirty years, the number of abortions has dropped fivefold (Kochergina Citation2018). The rise in the number of those calling for abortion to be restricted to specific circumstances likely reflects condemnation of Soviet practice, when a woman would have several abortions in her lifetime due to a lack of contraception. Russia’s current abortion legislation is more restrictive than its Soviet counterpart, but the restrictions are still in line with those of many progressive European countries.

Figure 2. Russia’s “normalisation”: Abortions-to-births ratio, 1992–2016. Source: World Values Survey.

One could, then, hypothesise that the rising trend in conservative attitudes has some of its roots in the desire to normalise family structures that were highly destabilised by the last decade of the Soviet Union and the 1990s and should therefore be interpreted as part of a normalisation process. The rise of “healthy way of life” narratives and practices, especially in relation to sobriety, confirms this trend.

Data collected by the LegitRuss survey in the spring of 2021 offer another overview of moral issues (see ). These results do not paint a picture of a particularly conservative society: two-thirds favour equality of women and men in the job market (but only half support gender equality in politics), childcare duties are seen almost unanimously as shared by parents, sex before marriage is accepted by a little more than half of the population, and the ideal family size is between 2 and 3 children. Conservative values appear especially in relation to sexuality, with a huge majority in favour of a heterosexual family.

Table 4. Russians’ view on several societal and moral issues.

Another feature that confirms the idea of a normalisation process is the relationship to punitiveness. Russian public opinion has been showing a consistent decline in support for the death penalty, even if it is still supported by about one third of the population. But the number of those supporting for outright abolition or current policy of commuting death sentences to life imprisonment has increased (see ). Yet we are still missing in-depth studies that would find a correlation between conservative beliefs and punitiveness.

Table 5. Levada Center – Which of the following statements on the death penalty do you agree with?

The only topic on which Russia appears unambiguously conservative is homosexuality. For a long time, Russia was only moderately conservative in terms of public attitudes toward homosexuality: in 2005, 51% of its population agreed fully or partly with the idea that homosexuals had the same rights as other citizens (see ). Between the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1993 and the first so-called anti-“homosexual propaganda” law in 2013, Russia passed no specific legislation either against homosexuals nor protecting them from discrimination. Homosexuality was considered a private matter: it was not forbidden, but such individuals were asked to remain invisible, with very few activists fighting for recognition (Kondakov Citation2014; Soboleva and Bakhmetjev Citation2015; Stella Citation2007; O’Dwyer Citation2013).

Table 6. Levada Center – “Do you agree or disagree with the statement that gays and lesbians should have the same rights as other citizens?” 2005–2019.

Since the deterioration of relations with the West in 2011–2014, homophobia has been weaponized by the Russian state as a tool in the competition with the West, encapsulated by the sloganeering of gayropa (Riabova and Riabov Citation2019; Riabov and Riabova Citation2014; Tyushka Citation2021). The internal debate on homosexuality has also been “coloured” ideologically by the context of Russians’ demographic decline (Kofman Citation2020), especially high male mortality, which Putin has been presenting as a danger to Russia’s survival since 2000.

The peak of homophobic attitudes was reached in 2013, parallel with state-backed narratives, to the point that one could state that this is the most successful case of state influence over public values. Yet two caveats must be noted. The first is that homophobia may express different things in the popular vernacular than at the level of state rhetoric. Jeremy Morris and Masha Garibyan (Citation2021) have shown, for instance, that homophobia relates more to citizens’ relationship to cynical elites and nostalgia for Soviet cultural homogeneity than to an existential Russia-West binary. Ukhova (Citation2018) has interpreted homophobia as an expression of social distress on the part of the lower and middle classes and a way of coming to terms with economic inequalities without using the language of class.

Second, it seems that popular homophobia is on the decline. In 2019, Levada registered the highest level of support for LGBT+ rights in the last 14 years, with 47% of respondents agreeing with the statement that “Gays and lesbians should enjoy the same rights as other citizens” compared to 43% who disagreed (Levada Center Citation2019a). Homophobia thus appears to be a highly ideological focal point of tensions around Russia’s own representation as a European nation and its ideological competition with the West, which explains its salience in state-backed conservatism.

The gap between discourse and practice

Not only can the rise in moral conservatism be interpreted as a call for stability in the transformation of moral values, but Russian society’s conservative stance is limited by a large gap between discourses and practices. This discrepancy is particularly visible in its relationship to the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). The Church has experienced an impressive rehabilitation as an institution representing national traditions and supporting (the majority of) state visions for the country (Papkova Citation2011). Yet public opinion remains hesitant toward it. Surveys show quite a large discrepancy in results depending on how questions are asked (whether questions about beliefs and/or practices are asked explicitly or not) and in which context (which questions precede them).

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the number of people who consider themselves Orthodox Christians has certainly grown. Between 1991 and 2020, the proportion of those believing in God increased by 2.5 times, from 14% to 35%; the share of atheists decreased from 18% to 9%; and the number of those not knowing, or believing intermittently, or believing in a higher force but not in God, remained more or less stable (Levada Center Citation2020a). The proportion of Russian citizens declaring themselves to be Orthodox (an ambiguous formulation that does not imply belief in God or practice) has stabilised around 65%, making it lower than the share of people identifying as ethnic Russians (77%), as some belong to another confession or do not feel attached to any faith, but higher than the share of those who believe in God, with the implication that a lot of Orthodox are non-believers. Indeed, Levada (Citation2013) calculated that about 30% of those who identify as Orthodox do not believe in the existence of God.

The LegitRuss survey found even lower results: only 55% of respondents said they belonged to a religion, of whom 81% identified Orthodoxy as their religion, meaning only 40.5% of respondents identified as Orthodox believers. This number is quite low compared to what is usually advanced, yet it seems to correspond to the results of the Sreda (Citation2012) survey on religious affiliation of Russians. Religious practice remains even more minimal, at numbers close to the most secular countries in Europe. Church attendance is very low, estimated at between 2% and 6% depending on how the question is framed (Mel’nikov Citation2019). Even if Russians became more traditionalist in the 2010s, their degree of religiosity did not evolve (see Shcherbak in this issue). This confirms that Russia shares with Europe the trend of “Identitarian Christianism” (Brubaker Citation2017), referring to Christian roots as part of national culture and identity to oppose Islam, migrants, or, in the Russian case, the supposedly decadent West, but without any religious practice.

The ROC has secured the respect of a large part of the population. More than 92% of the public has a positive attitude toward it, a figure that includes members of ethnic minorities belonging to other faiths (LegitRuss Citation2021). A slight majority of Russians support the idea of protecting the Church from symbolic degradation and consider that insulting religious values is inappropriate. According to a 2013 FOM survey conducted at the time of the Duma discussions on a law against blasphemy in the wake of the Pussy Riot affair (Borenstein Citation2020), 55% of respondents supported imposing fines for offending religious feeling (FOM Citation2013) while only 8% were opposed. Interestingly, people with higher education and residents of big cities (Moscow excluded) tended to be more defensive of the law; young people (18–24 years old) and Muscovites exhibited a less supportive stance.

The Church’s attempts to encroach on secular institutions, meanwhile, have been received much less warmly. Even symbolically, religion falls very low on Russians’ ranking of national identity and causes for pride: It went from a maximum of 15% in 2015 to 8% in 2020, at ranking number 11 out of 14 causes of pride, far below “our past and history” (55%) and “our land” (39%), “our nature” (34%). Even among practicing believers, it reached only 19% (Levada Center Citation2020c). In terms of trustworthiness, it is ranked fourth behind the army, the president, and the security services, at a relatively low 40% (Levada Citation2021). And more than two-thirds of Russian citizens rejected the idea that religion should influence state decisions (Levada Citation2020a).

The introduction of school classes on Basics of Orthodox Culture as part of the portfolio of options offered to parents for their children under the broad umbrella of “Fundamentals of Religious Cultures and Secular Ethics” did not live up to the Church’s expectations either. Slightly over one-third of Russian families (37%) selected the class – essentially a religious subject – for their children in 2017, while 42% opted for secular ethics and 17% for world religious cultures (Iakimova, Citation2020). The LegitRuss (Citation2021) survey confirms that the population is quite divided as to whether it should be mandatory to learn about the Basics of Orthodox Culture at school: 51% are opposed and 46% in favour. Asked whether “Parents should have the right to determine what their own children learn in school,” meanwhile, 63% responded in the affirmative and just 34% in the negative.

The growing visibility of the Church on Russia’s urban and rural landscape has also given rise to tenacious resistance in some cases, especially in cities, while the Patriarchate’s efforts to regain religious properties seized by the Bolsheviks have generated tensions. For instance, the ROC’s claim that St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg should be transformed from a museum of religion into an active church has sparked controversy, with more than 200,000 city residents signing a petition against the move and several thousand demonstrating against it (Weir Citation2017). In early 2019, after a long standoff, it was announced that St. Isaac’s would not be returned to the ROC but would remain a museum (Karpenko Citation2019).

While the population accepts the idea that churches located in historical buildings should offer religious services, the prospect of their legal property being returned to the Patriarchate in the name of historical justice raises concerns: it is seen as a property grab that ignores the public interest. The construction of new churches in public spaces, such as parks, has sparked similar concerns, leading to protests. These protests have been especially enduring in the cases of Torfyanka park in Moscow (Activatica Citation2017), where some protesters have been beaten by an Orthodox militia, the Sorok Sorokov (Radio Svoboda Citation2016a, Citation2016b), and Malinovka park in St. Petersburg (Galkina Citation2017).

The Church has failed even more dramatically to emerge as a moral authority whose opinions matter. Its intrusion into private and public affairs – including its attempts to get abortion banned or censor improper art or pop culture – is disapproved of by a sizable proportion of public opinion. Almost 60% of Russians believe that abortion is a personal decision, not one in which outside actors should be involved (Kochergina Citation2018). All these data are in line with Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud’s conclusion that Russian public opinion does not support “the Church’s ambition to serve as a moral beacon” (Kolstø and Blakkisrud Citation2021).

Russia as plurality: conservative and non-conservative constituencies

Beyond the discrepancy between discourses and practices, Russian society remains quite fragmented in terms of its values (Morozov Citation2017). In this issue, Shcherbak shows that support for conservative values is not consistent but affected by foreign policy trends: it rose in 2014 due to the “rally-round-the-flag” effect produced by the annexation of Crimea but has been on the decline since 2016. Here, I am interested not in variations over time but in demographic variations – between regions, between generations, or related to the vivid urban-rural dichotomy. These paint a fairly contrasting picture of Russia’s diversity.

Magun and Rudnev (Citation2010, 38) find, for instance, that Russian public opinion is divided into two main clusters: those who hold a median position on the “openness” and “conservation” value axis, who comprise almost half of the population, and those who are extremely high on the value of “conservation,” who constitute about one-third of the population. (The remaining small clusters have “openness” as their dominant value.) Demographic, socioeconomic, and regional variations help to advance our understanding of the distinctive ways that bottom-up conservatism influences Russian politics by identifying those groups that are producers/recipients of conservative frames and those that display reluctance toward – and potentially resistance to – them.

Socioeconomic variation

Byzov (Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018, Citation2019) was the first to try to locate Russia’s conservative constituencies. He categorised them into three main groups: the so-called traditionalist periphery, which includes ethnic republics and rural areas; “semi-marginalised urban populations” from small, industrial, and depressed towns who are unable to survive under the conditions of a market economy without state support; and a segment of the middle class that is calling for social and political stability.

Byzov’s categorisation has been indirectly confirmed by other works. In his first category (that overlaps with regional variations), Russia’s Muslim regionsFootnote3 not only display higher political loyalty to the regime but appear more “traditional” in terms of moral values than regions dominated by ethnic Russians. Traditionalism seems more characteristic of the North Caucasus than of the Volga-Ural region, for instance (Gerber Citation2017). Yet we lack in-depth statistical data to move us beyond anecdotal evidence, as surveys are often conducted with just 1500–2000 respondents, not enough to be able to capture the specificities, such as there are, of Muslim Russians.

We do know that belief in the existence of God is higher among Muslims than among Orthodox (Levada Center Citation2020a). A 3000-respondent survey carried out in 2016 by a group of scholars from RANKhiGS and the Gaydar Institute for Economic Politics in Dagestan further offers us rare insights – even if not representative ones – into the moral values of the Dagestani population. It shows that youth is largely more religious in its practice than older generations. Among the most salient differences from the majority of Russians, one may notice a strong gendered division of labour (only 7% of men with small children agree to let their wives work, even if the children are supervised by their grandparents during this time) and a higher level of homophobia (at 94% opposition) (Starodubrovskaia, Lazarev, and Varshaver Citation2016). The LegitRuss (Citation2021) survey, meanwhile, confirms that people from the North Caucasus are the strongest supporters of heterosexual marriage.

The second category is confirmed by the broader literature on the rise of populist or illiberal movements in Europe and the US, which identify disenfranchised blue-collar groups facing economic insecurity and loss of social status as the core group supporting some forms of populist conservatism (Morgan and Lee Citation2018; Gusterson Citation2017, for the Russian case, see Morris Citation2016). The LegitRuss (Citation2021) survey corroborates this, finding that unemployed and poor people (defined as those able to cover just the essentials) are more likely to agree that the Basics of Orthodoxy should be taught in schools and that a marriage should be heterosexual.

The third group – “bourgeois conservatism” – may be more specific to Russia, where the urban middle classes tend to depend on the state for their jobs. In the 2000s, the scientific cities (naukogrady) were a stronghold of the Communist Party (Cherniakhovskii Citation2007), one of the first to articulate a traditional value agenda (March Citation2002). Based on data from protests in the early 2010s, Rosenfeld (Citation2020) has demonstrated that state-sector professionals are less likely to join protests in support of democratisation and more supportive of state narratives such as patriotism and great power – an indirect confirmation of Byzov’s third category.

Intergenerational variation

Another gap exists between generations. Born into an individualistic and less oppressive culture, younger cohorts are more inclined to accept individual differences and more tolerant of individuals’ sexual orientations than older generations (Levada Centre Citation2017). Moreover, while the entire population has been affected by a rise in official anti-Americanism since the 2014 Ukraine crisis, the young remain largely more positive about the US (and the West more broadly) than older generations: in 2018, 60% of those aged 18–24 had a positive view of the US, compared to an average of 33% for the whole country (Lipman and Volkov Citation2019).

The 2018 Levada survey on nostalgia, meanwhile, shows that Russian youth are the least nostalgic of all age cohorts (Levada Center Citation2018b). This does not mean they are not part of the broader atmosphere of wide support for Vladimir Putin, but his approval is not the same everywhere: urban students are more opposition-minded than older generations or rural youth, more favourable toward liberal parties such as Yabloko, and more positive toward Alexey Navalny. Youth is also more critical of Soviet practices of upbringing: young people oppose patriotic education at school twice as much as the average person (48% and 24%, respectively), while older people are the most supportive (81%, for an average of 69% support) (FOM Citation2020).

The LegitRuss (Citation2021) survey confirmed this trend, finding that young people (defined as those under 34) are more likely to agree that people can have sex before marriage, more tolerant toward homosexuality, and less likely to agree that the Basics of Orthodox Culture should be taught in schools. The same generational divide is visible in relation to the death penalty: the youngest cohort (18–24) is more favourable toward its abolition, while older generations (55+) are more supportive of restoring the death penalty as it existed in the 1990s (Levada Center Citation2019b). Young people also have more faith in the court system: 49% of those up to 29 trust the courts “a great deal” or “quite a lot,” compared to 40% of those between 30 and 49 (World Values Survey 2017–2020).

Regional variation

Last but not least, polarisation is visible at the regional level (I exclude here ethnic republics, which were partly discussed as part of the first type of variation). Differences in reception of the “traditional values” agenda are particularly noticeable between large urban centres and more provincial Russia. It remains difficult to judge whether regional status (as a republic, oblast, or krai) matters per se, as it seems that population density and socioeconomic development are the main variables.

In several surveys on different morality-related questions conducted by the Levada Center between 2015 and 2018, there is a striking gap between Moscow and big cities, on the one hand, and small towns and villages, on the other. In Moscow, almost half of the population accepts homosexuality, whereas this figure hovers around 20% in small cities and villages. Reversely, in relation to migrants, Moscow and big cities display higher rates of xenophobia than the rest of the country. Small towns and villages consider that living as a couple is better than being single, that couples with children should marry, and that Ukraine’s autocephaly is a matter of concern, while support for these positions is lower in Moscow and other large cities.Footnote4

The LegitRuss survey, too, reveals some interesting regional variations on key moral issues, as it covers both capital cities, Moscow and St. Petersburg; two Russian regions, Arkhangelsk and Ryazan; and an ethnic republic, Bashkortostan. As we can see from , Moscow and to a lesser extent St. Petersburg appear systematically more liberal than the three regions (except on the legitimacy of “beating children,” which more Muscovites seem to support). Differences are particularly visible on the issues of sex before marriage, abortion, and divorce, where Ryazan and Bashkortostan score low, as well as on the role of the Russian Orthodox Church in politics and education, toward which Moscow and Petersburg residents are particularly reluctant.

Table 7. LegitRuss regional variations on key moral issues. Answers yes/no.

Conclusion

What stands out from this analysis are both the ambivalences of conservatism in Russia and its multiple differentiations. These invite us to engage in a much more cautious and nuanced portrayal of Russia as a supposedly conservative society.

Differentiation first appeared between the reactive, unreflective conservatism of a large part of the society and constructed, state-backed conservatism. Russian society’s situational conservatism of the 1990s predated state conservatism but was largely devoid of moral content, especially with regard to family issues, as Russian society has largely been atomised and privacy questions are left to each household. This reactive conservatism was based on the broad but imprecise feeling of an “ideological vacuum” created not so much by the loss of the communist doctrine, which was largely discredited, but by the collapse of the Soviet moral order and the quest for stability after the difficult decade of the 1990s.

This nostalgia for some forms of moral order translated later into massive support for patriotic and paramilitary training for youth. As early as 2003, a Levada Center poll found that 83% of respondents were in favour of introducing a basic military training course to schools. In 2004, 62% supported the idea of reviving the Soviet practice of patriotic military education, compared to just 22% who disapproved (Vovk Citation2004). More recently, in 2016, another Levada Center poll found that 89% of respondents supported some form of “patriotic education” in schools; 78% backed the revival of the Soviet-era Basic Military Preparation programme (Levada Citation2016).

Nostalgia for the Soviet moral order can also explain popular support for a state ideology. To the 2021 LegitRuss survey question “Do you believe that Russia needs a state ideology,” a massive 78% replied in the affirmative and only 14% in the negative (LegitRuss Citation2021) – a number that confirms that for many Russians, today’s Russia has not been able to build a new societal order, translated into the language of a “state ideology.” Vernacular conservatism is thus not a pure reflection of state messaging but a response to post-Soviet social changes and increasing variation in standards of living. Russia has a Gini index of 37.5, putting it halfway between the US and the European average. While the state speaks the language of moral values, one can supposes society tends to view these values through the prism of social justice.

Conservative stances are also contextually built in a mirror game with the West, which is identified as too liberal. Specifically, the fear – cultivated by Russian media and especially talk shows promoting what Vera Tolz and Yuri Teper (Citation2018) have called agitainment – of the import to Russia of the U.S. culture wars has contributed to the consolidation of conservative narratives, which are presented as part of Russia’s “cultural code.”

This selective affinity between a bottom-up reactive conservatism and a top-down moral conservatism has afforded Putin himself and the regime more globally long-term support for two decades (Greene and Robertson Citation2019); however, it has severe limitations. Russian society has become progressively more conservative on relatively few topics: chiefly homosexuality, and to a lesser degree abortion and divorce. As for religion, the “Orthodoxization” of society appears to be part of the trend toward Identitarian Christianism visible all over Europe. Orthodoxy is referred to as a cultural identity without entailing any religious practice per se. Religiosity does not impact individual moral choices and a large majority of Russians live their lives far away from the Church’s principles. Moreover, the caveats to these conservative features are numerous: homophobia seems to have reached its peak and is now declining, while the vision of the family order appears to reflect mainly a “normalisation” of abortion and divorce practices that put Russia close to many European countries. With the exception of homophobia, Russian society does not appear strictly conservative compared, for instance, with the U.S. society or with many Central European countries.

As political and social rights have shrunk in Russia, adherence to norms, values, and cultural practices has become the “glue” that holds citizens together and preserves the social contract with the state. As a time when Russian society remains very diverse in terms of ways of life and cultural consumption, conservatism allows for the discursive sharing of common values. However, reactionary groups have emerged that tend to challenge the equilibrium the regime has tried to keep in its promotion of conservative values, while the rising discourses about foreign agents subverting Russian “cultural codes” have shaken the longtime strategy of not enforcing conservative conformity.

If a discursive moral conservatism may remain a long-term element of the citizenry in Russia, it will probably come to be challenged in terms of practices, as society is increasingly polarised between conservative strongholds and growing liberal or at least liberalising social groups, especially among the younger generations. This polarisation may undercut moral conservatism’s status as a “glue” that permits consensus among citizens and acceptance of the political order. Moreover, the rise in power of ultraconservative or reactionary groups – in particular around the Church, which is trying to position itself as a moral leader – is creating a certain backlash even among elites, showing the limits of the state-sponsored “conservative turn.”

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlene Laruelle

Marlene Laruelle, Ph.D., is Director and Research Professor at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. Dr. Laruelle is also Director of the Illiberalism Studies Program and a Co-Director of PONARS (Program on New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia). She has recently published Memory Politics and the Russian Civil War. Reds versus Whites (Bloomsbury, with Margarita Karnysheva) and Is Russia Fascist? Unraveling Propaganda East and West (Cornell University Press).

Notes

1 I am grateful to Katharina Bluhm, Pál Kølstø, and Olga Malinova for their comments on the draft version of this article. Some excerpts of this article have been published as part of the conference paper “30 Years After 1991: Is It A ‘New’ Russia?” at the U.S.-Russia Relations: Competition, Deterrence, and Diplomacy, Aspen Institute Congressional Program 22–24 October 2021, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

2 For the most recent version of the Inglehart-Welzel Cultural Map, see http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp?CMSID=Findings.

3 We define Russia’s Muslim regions as those whose main historical religion and cultural framework has been Muslim, but many of their residents are in fact only nominally Muslims and may not be practicing.

4 I thank Denis Volkov for giving access to this data in the framework of an ongoing research project with Maria Lipman.

References

- Activatica. 2017. “Moskvichi okhranyayut park ‘Torfyanka’ ot vyrubki pod khram RPTS” [Muscovites Protect ‘Torfyanka’ Park from Being Cut Down for the ROC Church]. Activatica. July 7. http://activatica.org/problems/view/id/387/title/moskvichi-vzyali-pod-ohranu-park-torfyanka-kotoryy-pytaetsya-zastroit-rpc.

- Borenstein, Eliot. 2020. Pussy Riot: Speaking Punk to Power. London: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing.

- Botan, Carl H. 2018. Strategic Communication Theory and Practice: The Cocreational Model. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Brubaker, Roger. 2017. “Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, no. 8: 1191–1226.

- Byzov, L. G. 2014. “Novoe konservativnoe bol’shinstvo kak sotsial’no-poiliticheskii fenomen” [The New Conservative Majority as a Social and Political Phenomenon]. Mir Rossii, Sotsiologiia. Etnologiia 23 (4): 6–34.

- Byzov, L. G. 2015. “Konservativnyi trend v sovremennoi rossiiskom obshchestve—istoki, soderzhanie i perspektivy” [The Conservative Trend in Modern Russian Society—Origins, Content and Prospects]. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’ 4: 26–40.

- Byzov, L. G. 2016. “Tsennostnaia transformatsiia rossiiskogo obshchestva na fone sotsial’no-politicheskogo krizisa i postkrymskogo sindroma” [Value Transformation of Russian Society against the Background of the Social-Political Crisis and Post-Crimean Syndrome]. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost’ 6: 5–20.

- Byzov, Leontiy Georgievich. 2018. “Conservative Trends in Contemporary Russian Society.” Russian Social Science Review 59 (1): 39–58.

- Byzov, L. G. 2019. “Tsennostnaia evolutsiia ‘putinskogo konsensusa’ v pervyi god poslednego prezidentskogo sroka” [The Value Evolution of the ‘Putin Consensus’ in the First Year of the Last Presidential Term]. Obshchestvennyie nauki i sovremennost’ 4: 42–56.

- Cherniakhovskii, Sergei. 2007. “KPRF: na grani delegitimatsii” [Communist Party of the Russian Federation: On the Verge of Delegitimization]. APN, December 14. https://www.apn.ru/publications/article18702.htm.

- Colton, Timothy J. 1996. “From the Parliamentary to the Presidential Election: Russians Get Real About Politics.” Demokratizatsiya 4 (3): 371–379.

- Enns, Peter K. 2014. “The Public’s Increasing Punitiveness and Its Influence on Mass Incarceration in the United States.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 857–872.

- Evans, Jonathan, and Chris Baronavski. 2018. “How Do European Countries Differ in Religious Commitment? Use Our Interactive Map to Find Out.” Pew Research Center, December 5. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/05/how-do-european-countries-differ-in-religious-commitment/?fbclid=IwAR1unFUq69fgEQgNa31jBKcj8sP4JVIMx6RUPTcUHfBPY43TghwnCBne744.

- Fawcett, Edmund. 2020. Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fedorov, Valerii, Iuliia Baskakova, and Anna Zhirikova. 2017. “Rossiia udivliiaet: piat’ epoch v rossiskom obshchestvennom menenii (1987-2017)” [Russia Surprises: Five Eras in Russian Public Opinion (1987-2017)]. VTsIOM, March 6. https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/rossiya-udivlyaet-pyat-epokh-v-rossijskom-obshhestvennom-mnenii-1987-2017.

- FOM. 2013. “Otnosheniye k zakonoproyektu o chuvstvakh veruyushchikh.” January 22. https://fom.ru/Bezopasnost-i-pravo/10782.

- FOM. 2020. “Nuzhno-li patrioticheskoe vospitanie?” Fond obshchestvennogo mneniia, July 20, https://fom.ru/TSennosti/14411.

- Foucault, Michel. 1997. Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 1954–1984, Vol. 1. New York: New Press.

- Galkina, Yulya. 2017. “Antropolog Zhanna Kormina – o tom, zachem RPTS novye i starye khramy” [Anthropologist Zhanna Kormina on Why the ROC Needs New and Old Churches]. The Village. January 30. https://www.the-village.ru/people/whats-new/255979-orthodoxy.

- Gerber, Theodore. 2017. “Political and Social Attitudes of Russia’s Muslims: Caliphate, Kadyrovism, or Kasha?” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, April 5. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/political-and-social-attitudes-of-russia-s-muslims-caliphate-kadyrovism-or-kasha/.

- Goode, J. Paul. 2016. “Love for the Motherland (or Why Cheese Is More Patriotic Than Crimea).” Russian Politics 1 (4): 418–449. doi:10.1163/2451-8921-00104005.

- Goode, J. Paul. 2021. “Becoming Banal: Incentivizing and Monopolizing the Nation in Post-Soviet Russia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (4): 679–697. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1749687.

- Greene, Samuel A., and Graeme B. Robertson. 2019. Putin v. the People. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Gusterson, Hugh. 2017. “From Brexit to Trump: Anthropology and the Rise of Nationalist Populism.” American Ethnologist 44 (2): 209–214.

- Hale, Henry E. 2018. “How Crimea Pays: Media, Rallying ‘Round the Flag, and Authoritarian Support.” Comparative Politics 50 (3): 369–391.

- Herzfeld, Michael. 1987. Anthropology through the Looking-Glass: Critical Ethnography in the Margins of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hough, Jerry F., Evelyn Davidheiser, and Susan Goodrich Lehmann. 1996. The 1996 Russian Presidential Election. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Huntington, Samuel. 1957. “Conservatism as an Ideology.” American Political Science Review 51: 454–473.

- Iakimova, Olga. 2020. “A Decade of Religious Education in Russian Schools: Adrift between Plans and Experiences.” PONARS Policy Memo 676. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Pepm676_Iakimova_Nov2020.pdf.

- Karpenko, Mariya. 2019. “Isaakii po-prezhnemu ostaetsya muzeem” [St. Isaac’s Remains a Museum]. Kommersant. January 10. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3850656.

- Kochergina, Ekaterina. 2018. “Predstavleniya o gendernykh rolyakh I gendernom ravnopravii v Rossii. Analiz dannykh massovykh oprosov za 30 let” [Perceptions of Gender Roles and Gender Equality in Russia. Analysis of data from mass surveys over 30 years]. Vestnik obschestvennogo mneniya Dannye. Analiz. Diskussii 3-4 (127).

- Kofman, Michael. 2020. “Russian Demographics and Power: Does the Kremlin Have a Long Game?” War on the Rocks (blog), February 4. https://warontherocks.com/2020/02/russian-demographics-and-power-does-the-kremlin-have-a-long-game/.

- Kolstø, Pál, and Helke Blakkisrud. 2021. “Not So Traditional After All? The Russian Orthodox Church’s Failure as a ‘Moral Norm Entrepreneur’.” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo no. 710, October 2021. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/not-so-traditional-after-all-the-russian-orthodox-churchs-failure-as-a-moral-norm-entrepreneur/.

- Kondakov, Alexander. 2014. “The Silenced Citizens of Russia: Exclusion of Non-Heterosexual Subjects from Rights-Based Citizenship.” Social & Legal Studies 23 (2): 151–174.

- LegitRuss. 2021. “Values-based legitimation in authoritarian states: top-down versus bottom-up strategies, the case of Russia”. Research project funded by the Council of Norway, Project number 300997.

- Levada Center. 2008. “A.A. Golov: Uverennost’ v zavtrashem dne do i posle vyborov” [A.A. Golov: Confidence in the Future Before and After the Elections]. April 6. https://www.levada.ru/2008/04/06/a-a-golov-uverennost-v-zavtrashnem-dne-do-i-posle-vyborov/.

- Levada Center. 2013. “Rossiiane o Pussy Riots i tserkvi”. May 20, https://www.levada.ru/2013/05/20/rossiyane-o-pussy-riot-i-tserkvi/

- Levada Center. 2015a. Obshchestvennoe mnenie—2014. Moscow: Levada Center. http://web.archive.org/web/20150824073010/http://www.levada.ru/sites/default/files/om14.pdf.

- Levada Center. 2015b. “Pravo na abort” [The Law on Abortion]. July 2. https://www.levada.ru/2015/07/02/pravo-na-abort/.

- Levada Center. 2016. “78 percent rossiian khotiat vernut’ uroki NVP” [78 Percent of Russians want the return of Basic Military Training], September 1. Levada Center, 1 September, https://www.levada.ru/2016/09/01/78-rossiyan-hotyat-vernut-uroki-nvp/.

- Levada Center. 2017. “Religioznost’” [Religiosity]. July 18. https://www.levada.ru/2017/07/18/religioznost/.

- Levada Center. 2018a. “Brachnye normy” [Marriage Norms]. December 18. https://www.levada.ru/2018/12/18/brachnye-normy/.

- Levada Center. 2018b. “Nostal’giya po SSSR.” [Nostalgia for the USSR]. December 19. https://www.levada.ru/2018/12/19/nostalgiya-po-sssr-2/?fromtg=1.

- Levada Center. 2018c. “Chustva okruzhaiushchikh” [Feelings of Those around]. November 19. https://www.levada.ru/2018/11/19/chuvstva-okruzhayushhih/.

- Levada Center. 2019a. “Otnoshenie k lgbt-liudiam” [Attitudes toward LGBT People]. https://www.levada.ru/2019/05/23/otnoshenie-k-lgbt-lyudyam/.

- Levada Center. 2019b. “Smertnaia kazn’” [The Death Penalty]. November 7. https://www.levada.ru/2019/11/07/smertnaya-kazn-2/.

- Levada Center. 2020a. “Velikii post i religioznost’” [Lent and Religiosity]. March 3. https://www.levada.ru/2020/03/03/velikij-post-i-religioznost/.

- Levada Center. 2020c. “Gordost’ i identichnost’” [Pride and Identity]. October 19. https://www.levada.ru/2020/10/19/gordost-i-identichnost/.

- Levada Center. 2021. “Doverie obschestvennym institutam” [Trust in Public Institutions]. Levada Center, October 6. https://www.levada.ru/2021/10/06/doverie-obshhestvennym-institutam/.

- Lipman, Maria, and Denis Volkov. 2019. “Russian Youth: How Are They Different from Other Russians?” PONARS Eurasia Point & Counterpoint. January 18. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/russian-youth-how-are-they-different-from-other-russians/.

- Magun, Vladimir, and Maksim Rudnev. 2010. “The Life Values of the Russian Population: Similarities and Differences in Comparison with Other European Countries.” Russian Social Science Review 51 (6): 19–73.

- Magun, Vladimir, and Maksim Rudnev. 2012. “Basic Values of Russians and Other Europeans: (According to the Materials of Surveys in 2008).” Problems of Economic Transition 54 (10): 31–64.

- Malinova, Olga. 2021. “Framing the Collective Memory of the 1990s as a Legitimation Tool for Putin’s Regime.” Problems of Post-Communism 68 (5): 429–441.

- March, Luke. 2002. The Communist Party in Post-Soviet Russia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Mel’nikov, Andrey. 2019. “Russkaya identichnost' ne nuzhdayetsya v vere.” Nezavisimaya gazeta, January 21. http://www.ng.ru/kartblansh/2019-01-21/3_7487_kart.html?fbclid=IwAR1jZr-Z1HNkZSNsyuz-SnStyKisitg1oc-AdViDrLAV1Q2F5eI3rFnElyc.

- Morgan, Stephen L., and Jiwon Lee. 2018. “Trump Voters and the White Working Class.” Sociological Science 5: 234–245.

- Morozov, V. 2017. “Mif o reaktsionnosti rossiiskogo massovogo soznaniia i problema intellektual’nogo liderstva” [The Myth of the Reactionary Nature of Russian Mass Consciousness and the Problem of Intellectual Leadership]. PONARS Eurasia. New Approaches to Research and Security in Eurasia, April 28. Quoted in Jordan Gans-Morse. 2017. “Demand for Law and the Security of Property Rights: The Case of Post-Soviet Russia [NEW BOOK / ARTICLE].” April 26. https://www.ponarseurasia.org/demand-for-law-and-the-security-of-property-rights-the-case-of-post-soviet-russia-new-book-article/.

- Morris, Jeremy. 2016. Everyday Post-Socialism: Working-Class Communities in the Russian Margins. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morris, Jeremy, and Masha Garibyan. 2021. “Russian Cultural Conservatism Critiqued: Translating the Tropes of ‘Gayropa’ and ‘Juvenile Justice’ in Everyday Life.” Europe-Asia Studies, forthcoming.

- O’Dwyer, Connor. 2013. “Gay Rights and Political Homophobia in Postcommunist Europe: Is There and EU Effect?” In Global Homophobia: States, Movements, and the Politics of Oppression, edited by Meredith L. Weiss, and Michael J. Bosia, 103–126. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Papkova, Irina. 2011. The Orthodox Church and Russian Politics. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Press.

- Pew Research Center. 2018. “Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues.” October 29. https://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/.

- Pomerantsev, Peter. 2014. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Riabov, Oleg, and Tatiana Riabova. 2014. “The Decline of Gayropa? How Russia Intends to Save the World.” Eurozine, February 5.

- Riabova, Tatiana, and Oleg Riabov. 2019. “The ‘Rape of Europe’: 2016 New Year's Eve Sexual Assaults in Cologne in Hegemonic Discourse of Russian Media.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 52 (2): 145–154.

- Robinson, Paul. 2019. Russian Conservatism. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Rosenfeld, Bryn. 2020. The Autocratic Middle Class: How State Dependency Reduces the Demand for Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Shcherbak, Andrei and Maria Ukhvatova. 2018. “Ot 'krasnogo poiasa'-k 'bibleiskomu': istoricheskie predposylki sdvigov v politicheskoi geografii Rossii” [From 'Red Belt' to 'Bible Belt: The Historical Background of Shifts in the Political Geography of Russia]. Obshchestvennye nauki i sovremennost' 6: 98–113.

- Shmevel, Aleksandr. 2007. “Perspektivy avtoritarizma v Rossii.” Otechestvennye zapiski 6: 41–61.

- Silver, J. R., and E. Silver. 2017. “Why Are Conservatives More Punitive Than Liberals? A Moral Foundations Approach.” Law and Human Behavior 41 (3): 258–272. doi:10.1037/lhb0000232.

- Soboleva, Irina V., and Yaroslav A. Bakhmetjev. 2015. “Political Awareness and Self-Blame in the Explanatory Narratives of LGBT People Amid the Anti-LGBT Campaign in Russia.” Sexuality & Culture 19 (2): 275–296. http://sreda.org/arena?mapcode=code13113.

- Sreda. 2012. “Atlas religii i natsional'nostei Rossii,” http://sreda.org/arena?mapcode=code13113

- Starodubrovskaia, I., E. Lazarev, and E. Varshaver. 2016. “Tsennosti dagestanskikh musul’man: chto pokazal opros” [Values of Dagestani Muslims: What the Survey Showed]. Kavkazkii Uzel. https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/itogi_oprosa_naselenia_Dagestana/.

- Stella, Francesca. 2007. “The Right to Be Different? Sexual Citizenship and Its Politics in Post-Soviet Russia.” In Gender, Equality and Difference During and After State Socialism, edited by Matthew K. Ray, 146–166. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Svoboda. 2016a. “Zashchitnikov ‘Torfiianki’ obviniaiut v oskorblenii chuvstv veruiushchikh” [“Torfiianka” defenders accused of insulting the feelings of believers], Radio Svoboda, November 14. https://www.svoboda.org/a/28114550.html.

- Svoboda. 2016b. “V parke ‘Torfiianka’ v Moskve osvistali pravoslavnykh aktivistov” [Orthodox activists baptized in ‘Torfiianka’ park in Moscow], Radio Svoboda, February 13, https://www.svoboda.org/a/27550383.html.

- Tolz, Vera, and Yuri Teper. 2018. “Broadcasting Agitainment: A New Media Strategy of Putin’s Third Presidency.” Post-Soviet Affairs 34 (4): 213–227.

- Tyushka, Andriy. 2021. “Weaponizing Narrative: Russia Contesting Europe’s Liberal Identity, Power and Hegemony.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies, forthcoming.

- Ukhova, Daria. 2018. “‘Traditional Values’ for the 99 Percent? The New Gender Ideology in Russia.” LSE Blog, January 15.

- von Haldenwang, Christian. 2017. “The Relevance of Legitimation—A New Framework for Analysis.” Contemporary Politics 23 (3): 269–286.

- Vovk, E. A. 2004. “Patrioticheskoe vospitanie: slovom ili delom?” [Patriotic Education: Words or Acts?]. Fond obshchestvennogo mneniia, February 5.

- Weir, Fred. 2017. “Museum or Church? St. Isaac's Becomes Bone of Contention in Russia.” Christian Science Monitor, February 23. https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2017/0223/Museum-or-church-St.-Isaac-s-becomes-bone-of-contention-in-Russia.

- Wilkinson, Cai. 2014. “Putting ‘Traditional Values’ into Practice: The Rise and Contestation of Anti-Homopropaganda Laws in Russia.” Journal of Human Rights 13 (3): 363–379.

- World Prison Brief. 2020. “Russia.” https://www.prisonstudies.org/.