ABSTRACT

This study examines democracy promotion efforts that target young people in post-Soviet countries. Specifically we assess the effectiveness of a civic education programme in Poland in improving attitudes toward democracy and self-perceptions of political efficacy. The analysis of quasi-experimental data reveals that young citizens from post-Soviet states (Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine) were more likely to show greater support of democratic institutions, hold democratic attitudes, and perceive themselves as having political efficacy. However, we interpret the results with caution as changes in the attitudes were not substantial. This may be attributed to the fact that democracy education programmes attract already politically and socially active young people.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, political scientists and political economists have produced an extensive empirical literature that examines the efficacy of democracy promotion efforts across the world. Many of these studies explore how foreign assistance shapes domestic political institutions (Licht Citation2010; Bermeo Citation2011; Scott and Steele Citation2011; Dietrich and Wright Citation2015; Ariotti, Dietrich, and Wright Citation2021). However, less attention has been devoted to studying how external assistance promotes the development of civil society (Pospieszna Citation2019). This article studies a particular type of civil society assistance: programmes that promotes civic engagement of young people in post-Soviet countries.

Over the past decade, civic engagement programmes have become a standard category of civil society assistance, especially in post-Soviet states. Since 2004, Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, like Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, have invested in actively promoting democracy in post-Soviet States through their development cooperation programmes (Petrova Citation2014; Pospieszna Citation2014). And although, over time, CEE governments have themselves adopted anti-democratic tendencies (Guasti and Bustikova Citation2020; Ekiert, Kubik, and Vachudova Citation2007; Foa and Mounk Citation2016; Kotwas and Kubik Citation2019; Magyar and Madlovics Citation2020), non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from these same countries have continued to support democratic development (Petrova and Pospieszna Citation2021). For example, despite increasingly unfavourable conditions, several Polish NGOs continue to run civic education programmes directed toward young people in other post-communist countries.

Typically, civic education programmes complement existing domestic civic education programmes in schools, in which scholars of civic education are keen to point out often fall short of equipping young people with the means to become active in civic or political life (Solhaug Citation2013; Torney-Purta et al. Citation2001). Scholars that have studied civic education programmes that supplement domestic curriculums have found that civic education can (1) reduce support for political violence, (2) promote voter engagement, and (3) foster the flow of political information through the creation of opinion leaders. For example, Finkel, Horowitz, and Rojo-Mendoza (Citation2012) showed that exposure to a national civic education programme implemented in Kenya resulted in “inoculation effects” against political violence. Compared to non-participants, people affected by violence who participated in a national civic education programme were less likely to express negative attitudes about the political system and less likely to support ethnic violence in reprisal of the violence that they had experienced themselves. Other scholars have found that civic education may also be correlated with positive changes in voter turnout behaviour (Arriola et al. Citation2017; Finkel Citation2014; Mvukiyehe and Samii Citation2017). By promoting access to political knowledge, civic education increases the likelihood that voters participate in the democratic process. Participants are also more likely, all else equal, to become opinion leaders who disperse their civics training within their social networks (Finkel and Smith Citation2011).

Despite these documented beneficial effects of civic education programmes, there is still a lack of systematic knowledge about the impact of non-classroom civic education programmes on views about democracy. Using original data collected from an NGO-implemented extracurricular civic education programme conducted in Poland from 2014 to 2018, our research contributes to the understanding of how programme participants’ democratic attitudes are affected by their participation. The programme targeted youth from four post-Soviet countries, including Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine, and brought them to Poland for exchange visits with the intent to transfer knowledge on subjects linked to democratic values and civic engagement.

The data provide new evidence that civic education programmes may be an effective way to begin shifting perceptions concerning democracy among young citizens in post-Soviet countries. Using a panel evaluation of quasi-experimental data gathered from surveys of programme participants, we find that after participation in the programme, participants were more likely to believe democracy is made up of an important set of civic norms and institutions, hold positive attitudes toward democracy as a form of government, and perceive themselves as having political efficacy, relative to their initial beliefs and attitudes. This evidence provides preliminary validation for youth democracy promotion programmes, suggesting that they may indeed be a productive use of donor countries resources in the effort to make the world safe for democracy. However, an optimistic reading of the results should be tempered with caution. Although participation in a civic education programme was associated with more pro-democratic attitudes and efficacy beliefs, given the nature and duration of the civic education programme, these changes are not as substantial as one might expect. We argue this is because such programmes attract already politically and socially active young people. In other words, this form of civic education programme strengthens the democratic beliefs and attitudes of young people who are already equipped for civic and political life, and in many cases favourably predisposed toward democracy. The results also illustrate the challenges with evaluating democracy promotion programmes, given the difficult ethical and practical circumstances under which programmes must take place.

This article proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the literature on democracy promotion, civic education, and youth in the post-Soviet countries. The third section presents youth assistance efforts in the post-Soviet region and discusses a typology of programmes. We report the results regarding the impact of programme participation of the civic education programme that we evaluate based on participant survey respondents. In discussing the results, we also highlight usefulness and limitations of implementing an experimental approach in conjunction with the goals of NGOs helping to conduct the data collection. Finally, the article concludes with a summary of findings and implications for scholars as well as democracy-promoting NGOs, policymakers, or governments.

Democracy assistance, civic education and post-Soviet youth

To date, the literature on democracy promotion in post-Soviet states has largely focused on assistance coming from the EU or other traditional donor democracies of Western Europe or North America (Pishchikova Citation2010; Sundstrom Citation2006; Freyburg et al. Citation2009; Schimmelfennig and Scholtz Citation2008). However, beginning in the 2000s, young democracies of the CEE region have significantly increased democracy promotion efforts in post-Soviet states. This increase has been particularly pronounced since the Colour Revolutions – the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine – and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan (Berti, Mikulova, and Popescu Citation2015; Horký-Hlucháň and Lightfoot Citation2013; Petrova Citation2014; Pospieszna Citation2014; Szent-Iványi Citation2014; Szent-Iványi and Végh Citation2018; Tolstrup Citation2014).

Aside from the democracy aid from CEE governments, NGOs of the CEE region have also ramped up their efforts to disseminate democratic norms and values in neighbouring post-Soviet states in the context of cross-border projects (Pospieszna Citation2019; Petrova and Pospieszna Citation2021). These NGOs generally operate under the belief that broader societal changes require bottom-up pressure, and that they can catalyse this change by promoting understanding of and positive attitudes toward democracy, and by helping to build advocacy skills among citizens in non-democratic countries.Footnote1 Direct youth assistance through civic education programmes focuses on stimulating latent desires for a free and open society specifically among young people, increasing the quality of their competencies through developing awareness, and empowering them to participate in public life, either through enacting direct programmes or by sponsoring civil society youth groups (Bush Citation2015, 237).

In the civic education literature, “civic education”Footnote2 is education that intends to teach citizens basic values, knowledge, and skills for being an active and engaged citizen (Finkel Citation2002; Torney-Purta et al. Citation2001; UNESCO Citation2014). Scholars agree that civic education at school may be insufficient or ineffective, especially in non-democratic countries where the meaning of the concepts of citizenship and participation may differ dramatically between what is taught in domestic school curricula and what is commonly held to be the case in democratic societies. According to studies conducted by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievements (IEA) programme and the OECD programme PISA (the Programme for International Student Assessment), even within democratic societies, civic education may have weaknesses. For example, civic education in schools may focus too much on institutional formalities and procedures rather than enabling young people to see how they can apply conceptual material and engage with the democratic process more directly (Banks et al. Citation2004; Himmelmann Citation2013; Solhaug Citation2013; Schulz et al. Citation2008; Osler Citation2012; Torney-Purta et al. Citation2001).

By contrast, extracurricular learning opportunities for young people, such as dedicated training programmes or activities in the community, assume an important role in civic education (Terriquez Citation2015; Wong, Lau, and Lee Citation2012). Indeed, by targeting and promoting democratic values and norms through special civic education programmes, NGOs and the donors they represent hope to sow the seeds of democracy among young citizens. Democracy is undergirded by important normative and psychological factors, including the support of democratic institutions and norms, rejection of authoritarian practices and perceptions of political efficacy and a desire to participate (Dalton Citation2011, Citation2014; Norris Citation2002). Positive views of democracy as ideal and a continuous evaluation of it are crucial for the survival of democracy (Ferrin and Kriesi Citation2016). Although in parts of the world, democracy may seem to be in retreat at present, it is important to keep it ascendant in people’s values and aspirations (Diamond Citation2017). As such, the goal of many programmes is to instil democratic values and promoting positive views of democracy in the hopes of indirectly igniting subsequent political and civic engagement among young beneficiaries in target countries (Finkel Citation2002; Finkel and Smith Citation2011; Pospieszna and Galus Citation2020). However, there is scant evidence regarding the impact of programmes on changing beliefs and attitudes regarding democracy and participation (Green and Kohl Citation2007; Manning and Edwards Citation2014), especially in the post-Soviet countries.

In a post-Soviet context, however, scholars have found that democratic values exhibit little robustness. Scholarship has argued that democratic failure throughout many post-Soviet countries is, in part, explained by popular dissatisfaction with the outcomes of liberalisation policies, which have directly discredited democracy and thus negatively affected citizens’ interest in political life (Carnaghan Citation2007). Others claim that post-Soviet countries are “different” in terms of the values and norms to which they adhere (Korosteleva Citation2012), resulting from a political culture of subjugation propagated in the Soviet era created where citizens scored low on political efficacy and were rewarded for being loyal to the government.

Yet, even if it is the case that the culture in post-Soviet countries is different, there is reason to be optimistic about the development of a new political generation and their ability to bring about democratic change. Today, young people are not as socialised “into the political culture of the Soviet era.” They may still learn about socialist values through textbooks, movies, and stories told to them by family members, but the cultural pressures of socialisation into socialism are much weaker in comparison to prior generations (Krawatzek Citation2017; Diuk Citation2012). Donors and civil society actors see promise in this successor generation, targeting them for civic education programmes. Subjects of training include the protection of important civil rights, such as freedom of speech and association, an active and independent media, and a view of civil society that is engaged, diverse, and vibrant, among other elements. Such programmes often outside their own countries and in democracies where they can see and experience democracy first-hand.

After young people complete a civic education programme, the expectation is that they will become more positive about the democratic process. We would also expect civic engagement programmes to lead participants to re-examine authoritarian values that are still part of life in their home country, including, for example, the importance of loyalty to their government and political elites. This yields the following testable hypotheses:

H1: Youth participants in civic education programmes should express greater satisfaction with democracy as a system after their participation.

H2: Youth participants in civic education programmes should express greater support for key elements of democratic society after their participation.

H3: Youth participants in civic education programmes should express less support for authoritarian values after their participation.

Finally, while providing new information and new experience is a clear goal of civic education programmes, their ultimate intent is to empower participants to return to their home countries and to become involved in political action to promote democratisation processes there. Alongside perceptions of democracy, political efficacy is one of the most important underlying beliefs motivating people to participate. Political efficacy refers to the ability of citizens to influence political affairs, and to translate their values and preferences into policy. The greater sense of efficacy one has, the higher degree of participation in both electoral and non-electoral politics (Vráblíková Citation2017).

In post-Soviet countries, democratisation failures have been attributed to the lack of participation in non-electoral activities (i.e. unconventional forms of participation such as protest) that could have a constraining impact on elites (Dalton Citation2014). However, scholars studying youth participation in post-Soviet countries find that the young people have been a crucial part of the social changes that have already taken place in EECs between the end of the Soviet era and today (Krawatzek Citation2017; Schwartz and Winkel Citation2016). For example, they have played an important role in mobilising support for democratic revolutions in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine, as well as during Euromaidan and the 2001 and 2020 presidential elections in Belarus (Kuzio Citation2006; Nikolayenko Citation2007; Wilson Citation2006). Diuk (Citation2012) shows that beyond their involvement in regime-change, post-Soviet youth have shown increasing interest in involving themselves in politics and the governing of their countries.

Although Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia now have pluralistic civil societies that are more pro-democratic and pro-European than, for example, Russia (Henry Citation2006), clientelist networks remain entrenched, corruption remains widespread, and civil society is not strong enough to help offset it. When political efficacy is low, young people feel inadequate, irrelevant, and powerless in influencing political outcomes in their countries. Involvement in civic education programmes may promote political efficacy and encourage young people to broaden and strengthen their civic engagement in post-Soviet countries, for example by helping participants to see what is possible and has already been achieved outside their home borders. Further, it may provide the tools need for social organising, and help participants to create a network of like-minded peers with whom they can share their ideas, experiences, and challenges.

H4: Youth participants in civic education programmes should express a greater sense of political efficacy after their participation.

In sum, civic education experiences that take place outside-of-country can lead participants to change their attitudes on democracy, their own political system, and civic engagement. However, we should also keep in mind that pro-social and out-going young people might be more likely to participate in such programmes and engage in civic or political activities (Armingeon Citation2007; Van Der Meer and Van Ingen Citation2009).

Research design

Overview of existing youth programmes in four CEE countries

Before selecting a programme, we collected data on youth programmes in post-Soviet countries implemented by the NGOs from four CEE countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) that have been involved in democracy promotion efforts at home and abroad.Footnote3 We identified 305 youth programmes implemented during the period 2000–2017, which targeted young people directly or indirectly through: youth-led organisations; other NGOs and grassroots organisations; school heads and other educators (e.g. academics); teachers and lecturers; older members of the local community (e.g. parents); or political actors – for example – representatives of local authorities or ministries. The programmes were undertaken either through activities organised in the target countries or through activities abroad such as summer schools, internships, scholarships, exchange programmes, and study missions where participants left their home country.

What sort of democratic values do these NGOs’ youth programmes aim to convey? In Table A1 in the Appendix, we offer a typology of programmes. Overall, an examination of these programmes suggest that NGOs interested in democratisation typically focused on the inputs of citizens into the political system and on improving the quality of democracy or the democratisation process through citizens’ participation. Through these programmes, NGOs aimed to demonstrate that the liberal and constitutional components of the democratic order provide a necessary framework for associational life, which is at the core of civil society. The effective citizen is therefore an active citizen. It appears that one keyway through which NGOs tried to foment participation was to inform people about democracy and the values upon which democracy rests. They also sought to help build peoples’ sense of efficacy for making changes in their communities, local region, and even at the national level.

Among the programmes, civic education programmes were the most common (40% of all youth assistance programmes). Of civic education programmes, Polish NGO implemented the majority (55%), followed by Czech (35%), Slovak NGOs (10%).Footnote4 Civic education took the form of either activities organised in the target countries that support schools – by providing didactic materials, teachers training, organising workshops – or through activities such as summer schools, internships, scholarships, exchange programmes, and study missions’ programmes that are designed to also enhance participation through mechanism of knowledge.

For the purpose of our study, we selected a civic education programme called “Study Tours to Poland for Students”, funded by the Polish-American Freedom Foundation and implemented by a network of ten Polish NGOs.Footnote5 We chose this particular programme because, at the time, it was recurring on an annual basis and it included a substantial amount of programme participants, training around 200 students each year from Eastern Europe. Since 2004, the programme has trained young people, aged 18–21, from Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine. The data on programme participants was collected between 2014 and 2018. The programme’s main goals, outlined in its mission statement, include (1) supporting the development of civil society in Eastern European countries; (2) promoting democratic values and support of democratic changes in the region, through the belief that broader societal changes are bottom-up; and (3) promoting knowledge about Poland’s own transition to democracy and joining of the EU.

Regarding programme content, the programme provided information in the form of lectures about democracy as a political system and its fundamental values. It also provided a safe forum where students could speak freely about their own democratising or authoritarian systems, where they were able to develop and discuss their own opinions about democracy and express them. For many students, this was a first opportunity to learn and speak about these issues. Further, the programme aimed to deliver skills by teaching young people on how to become more active citizens in their respective countries and how to take civic responsibility for local society and the state. Importantly, the programme also exposed participants to the Polish experience with democracy, including developments of the economy, the media landscape, local self-government, public administration, civil society as well as the integration of Poland into the EU. The Polish case was presented both in terms of the successes it achieved during the period of political transformation as well as the challenges that it continues to face. Students were, thus, exposed to a measured picture of Poland’s experience with democracy that they could reflect upon and compare to developments in their home countries. At the end of their visit, participants were expected to understand the functioning of democracy as a political system and to be able to identify and take advantage of opportunities for civic engagement and participation in their home countries.

Experiment, observational study and survey

The initial empirical strategy for testing the effect of the programme on participant beliefs and attitudes relied on causal evidence from an experimental design where some applications were randomly selected for programme participation while others were rejected. This would allow us to make strong claims about causality (Morton and Williams Citation2006), as random assignment to treatment enables researchers to eliminate extraneous factors that can obscure or confound treatment effects (Duflo, Glennerster, and Kremer Citation2007; Hyde Citation2015). Yet, despite the clear advantages of an experimental empirical strategy, we encountered a number of obstacles that ultimately forced us to treat and analyse our data as observational. We hope that by discussing these difficulties here future researchers can benefit from lessons learned and beware of potential pitfalls that can lead to threats to causal inference in the study of democracy promotion.

In the first instance, the donor and the partner NGOs did not agree to full randomisation, where all programme participants would be randomly chosen from a pool of applicants. Instead, we agreed to employ a partial randomisation, also known as a lottery around the cut-off (Glennerster and Takavarasha Citation2013).Footnote6 To get accepted for the programme, participants were evaluated on three criteria, (1) school performance (including grades and other school activities); (2) participation (in youth, civic and other organisations), and (3) essay responses to questions from the organisers. As a result, the access to the programme relied on a student’s qualifications and ranking on the applicant list and would have resulted in treatment assignment being conflated with the strength of an application had we used the full sample.

By itself, a randomisation around a cut-off is workable if designed correctly. The design creates several “segments” representing the way by which people are allocated to treatment, with some being accepted or rejected unconditionally based on certain specified criteria (e.g. academic performance) and others – usually falling in an intermediate range – being accepted or rejected as the result of randomised allocation to treatment. Researchers can still compare treatment effects within the randomised segments, though the effective sample size is significantly smaller than the full roster of programme participants, as some have been accepted through non-random processes, for example by being accepted by virtue of being above a certain score on a rubric created by the organisation conducting the experiment. In our case, based on the NGO’s evaluation of programme applicants, we divided applicants into three groups: (1) those who were rated very highly and would be accepted into the programme unconditionally; (2) those who were rated very poorly and would be rejected unconditionally because they did not fulfil the minimum criteria; and (3) those who fell in between who would have a random chance of being accepted into the programme. Participants included youth from Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, and Russia over a four-year period. The programme took place twice a year, with an average of 100 (sd. = 10) participants per programme session, to make up a total sample of N = 848. The lottery around the cut-off was conducted separately for each nationality because the ranking list of students was prepared for each nationality.Footnote7 Ultimately, access to the programme relied on a student’s qualifications, but our intent was to compare those who were randomly accepted or rejected and leave out those who were accepted or rejected unconditionally, at least from the experimental analyses. While this compromise with the NGO reduced the potential sample size dramatically, it would have left us with the ability to identify the causal effects of the programme.

However, we faced a second serious obstacle in the form of incomplete data. More precisely, the data collection process resulted in data that were censored based on whether an applicant was accepted to the programme or not. Surveys containing our dependent variables of interest were collected at three time points: (1) during the application process; (2) immediately before programme participation; and (3) immediately following participation, but before participants returned to their home countries.Footnote8 The survey measures employed in the evaluation were grounded directly in the goals of the programme and were reflected in the content of the training offered to participants. The survey included questions (which we will discuss in greater detail in the next section) that capture changes in (1) beliefs regarding what democracy is; (2) support for democracy as a form of government; (3) authoritarian values; and (4) beliefs regarding political efficacy.Footnote9 Nevertheless, all surveys were optional and the NGOs’ controlled access to personal data, which prevented us from collecting additional information. This led to significant missing data from programme participants. Most importantly, the NGO did not survey rejected applicants – either those rejected outright or as the result of randomisation. Nor did the NGO collect surveys at the time of application in the first waves of the programme at all. In other words, these challenges together caused data to be missing, most importantly from the control group, which is effectively non-existent after the first wave, and then only in some instances of the programme.Footnote10

These problems left our design without an effective control group. And because the standards of good causal inference could not be sufficiently satisfied in several ways, we thus restrict ourselves to treating the data presented here as observational. In the following analyses, we compare survey responses from programme participants immediately before their participation with those immediately following the conclusion of the programme, roughly two weeks later. While it is not possible to disentangle the effect of the simple passage of time, we feel that such a narrow window still leaves the results illustrative at the very least.

Survey measures

The aim of the programme was to provide a foundational education in democracy and the survey was set up to evaluate how successful this was, in terms of affecting participants’ evaluations of democracy, beliefs about what it entails, authoritarian values, and feelings of efficacy. Participants’ attitudes towards democracy, or whether on balance they felt democracy is a good form of government, were collected as seven statements to which participants were asked to agree or disagree, such as “democracy leads to the well-being of citizens”, which were scaled together to form a unidimensional scale (α = 0.79).Footnote11 Beliefs about democracyFootnote12 and what makes it work, including the presence or absence of key democratic institutions, were similarly assessed with 25 Likert items that participants were asked to rate from “not important” to “very important”, which were scaled together to form a unidimensional scale (α = 0.95). The full list included essential aspects of democracy: free and fair elections, the rule of law, civil rights and various freedoms, and social justice. Third, participants’ inclination toward authoritarian values was measured by two items, such as “the key to a good life is discipline and obedience” and were scaled together to form a unidimensional with a pairwise correlation (r = 0.398). Finally, efficacy was measured with three agree–disagree Likert items, such as “most politicians, regardless of what they say, care only about their career”, which were scaled together to form a unidimensional scale (α = 0.53). All items for all measures were re-coded in the same direction, using median replacement for those who answered do not know/refused (missing values otherwise stayed missing), and the final scale was rescaled to 0–1 for ease of interpretability.

Empirical results

Given the limitations of the data, we examined the effect of programme participation by comparing participant survey responses immediately prior to the start of the programme with those gathered immediately after its completion. In the interest of robustness, we report the results of several different significance tests of these differences: (1) t-tests, as the standard way of testing difference of means; (2) the non-parametric sign test, an alternative to the t-test that can be used for test–retest data that effectively examines whether or not a significant number of people display greater or lesser values post-test compared to pre-test; (3) OLS regression clustered by participant; and (4) clustered OLS regression with interactions to investigate whether the treatment effects vary by either country or programme wave.

Does programme participation matter?

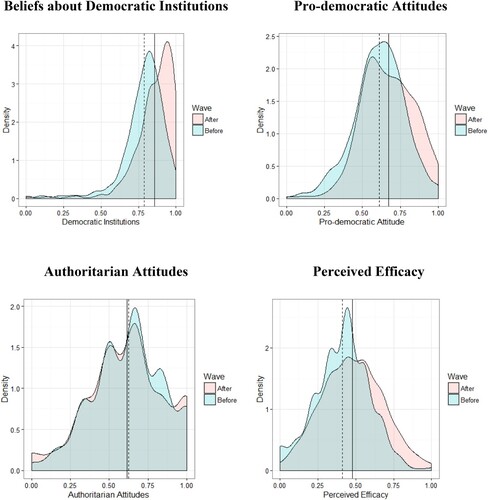

Hypothesis testing with both t-tests and non-parametric sign tests supports the results displayed in . Despite already displaying very positive attitudes prior to the programme, programme participation was associated with more positive beliefs about democracy (t = 9.150, p < 0.001), increases in pro-democratic attitudes (t = 7.032, p < 0.001), and feelings of efficacy (t = 7.285, p < 0.001). However, the programme did not impact authoritarian attitudes (t = −0.348, p = 0.728). Non-parametric sign tests affirm the same levels of significance.

How much does programme participation improve attitudes towards democracy and efficacy?

displays distribution plots for pre- vs. post-comparisons for dependent measures of interest and shows that the changes are indeed very slight, as might be expected given the admission strategy of favouring more talented, engaged applicants. Beliefs about and satisfaction with democracy were both already high before participants came to Poland. However, the programme did seem to have a discernible impact. As the regression models in Tables A2–A4 in the Appendix demonstrate, there is a 7% increase in support for democratic institutions and a 6% increase in overall evaluations of democracy following the programme. Feelings of efficacy were also nearly 7% higher following programme completion. Surprisingly, despite these pro-democratic adjustments, the programme had no detectable impact on participants authoritarian values. In fact, the mean response was a 0.6 on a 0–1 scale.

Prior to their participation, student participants perceived democratic systems favourably, believing that democracy was better than other forms of government and that it is desirable in all countries of the world regardless of political tradition and culture. And yet despite being pre-treated – or more accurately despite selection of participants already high on the dependent measures – participation in the programme seems to have strengthened beliefs regarding democracy. In other words, although young people from all four post-communist countries may have a good understanding of democracy and supported it before their participation, their participation in the programme nonetheless was associated on average with a further increase in their understanding of and support for democracy and beliefs about their ability to affect political change.

Discussion

Can civic education programmes help shape the views of democracy of young people from non-democratic countries? In an evaluation of participant survey data from one such programme, we found that following participation, programme participants were more supportive of both key democratic institutions and democracy overall. Further, they also displayed greater feelings of efficacy, suggesting that they may have been more prepared to return and work for democracy in their home countries. While some might note that these effects are substantively small, especially for such a strong treatment, it is important to consider them in light of the programme participants themselves, who were at its start already quite supportive of democracy, especially for coming from non-democratic countries. Given this, the fact that the programme had any impact is the more remarkable.

The results leave questions unanswered regarding the depth and durability of these changes. For one, participation in the programme did not seem to have any meaningful impact on participants underlying authoritarian values, which remained unchanged following completion of the programme. Additionally, it is unclear to what degree programme participants may also have been responding in a way that they believed might be expected by the programme organisers (i.e. demand effects) or their peers in the programme (i.e. social desirability pressures), especially as the final survey took place prior to their departure from Poland.

There was also no scope in this project to clearly examine what might make a youth civic engagement programme particularly effective. Aside from the difficulty here in fully accounting for the effect of the simple passage of time, other factors aside from the programme itself that took place concurrently may be responsible for changes in participants’ attitudes. One example might be socialisation: people recruited to such programmes are given an opportunity for socialisation, which may strengthen their attitudes and opinions. Or perhaps simple enjoyment of the experience, which might give participants a rosier outlook on life overall. We recognise here that a civic engagement programme is a complex treatment that is difficult to decompose far enough to clearly identify what drives change in participant beliefs and attitudes. Indeed, as Moehler (Citation2010) pointed out, the complexity of democracy promotion programmes makes evaluations in general difficult. Such programmes tend to combine many different activities targeted at beneficiaries, which are difficult to capture in surveys of programme participants. Nonetheless, what ultimately matters – and what the NGOs running these programmes place the greatest importance on – is that these programmes seem to positively impact their participants.

Beyond the scope of the programme, we would ideally explore the impact of programme “participants’ return” to their home countries, potentially looking at local indicators: increased numbers of young people registered to vote, increased number that actually voted, and increased numbers of young people joining youth clubs or organisations, etc. as compared to the pre-evaluation period. However, doing so would be several degrees more complex than what has been done in the present study, which already encountered notable problems in merging the goals of academic research with the agendas of NGOs. Further, trying to follow programme participants after the programme ends also carries with it serious ethical concerns, involving interacting with participants in ways that could put them in danger in their home countries. More general questions of what impact programmes can have are not so straightforward, be they in regard to the participatory levels of societies as whole, or whether citizen-focused democracy assistance is effective in enabling citizens to organise under non-democratic regimes to facilitate liberalisation and democratisation.

Taking into account the above, one might be tempted to say that young people in non-democratic countries might not need civic education programmes because they already seem to be well-educated, supportive of democracy, and feel politically efficacious. Thus, we might be optimistic about young people’s participation in the post-Soviet countries without any additional intervention. However, it would be ill-advised to dismiss the role of youth programmes and it is necessary to consider other possible explanations. There is no easy way to generate politically engaged youth, and it will likely remain difficult to determine the democracy promotion programme’s contribution; however, our study has demonstrated that the civic education programmes can create a space, a platform for civic skills and mindedness development.

Conclusion

Participation lies at the heart of democracy, and it requires citizens to feel sufficiently empowered to act. Sustained engagement of citizens is at least in part the result of beliefs and perceptions regarding their role as citizens and their attitudes toward democracy. This article has demonstrated the efforts of NGOs from CEE countries to support young people via various programmes in the post-Soviet countries. A typology and description of programmes showed that NGOs interested in democracy promotion have clear and prevalent goals to activate and teach liberal-democratic values in young citizens in non-democratic countries. The research into more than 300 programmes directed toward young people in post-Soviet countries shows that democracy and active citizenship have been taught to young people with the support of NGOs from CEE countries by means of many different initiatives, ranging from teaching how to create an organisation or youth-led media, to educate them about democracy, or to help them acquire certain soft skills such as strengthening public-opinion skills or how to debate. The content used in youth programmes across the post-Soviet region is remarkably comparable and shows that NGOs from CEE countries aim to share their approach toward democracy and the role of citizens in society. It implies that NGOs can serve as conduits for democratic norms, which is especially important given the current pollical climate where some young democracies in the region (Poland and Hungary) are experiencing democratic crises.

Given this recent erosion and backsliding in CEE countries, liberal democracy in these countries is under threat, and several recent events associated with growing destabilisation in these countries undermines activities intended to promote democracy, which can be treated with suspicion. Nevertheless, if liberal democracy were to wane in Poland, for example, it could still credibly be believed that liberal democracy as a model would continue to be promoted both domestically and abroad by NGOs. Many of the representatives of organisations started investing in democratisation processes in the neighbourhood in the 1990s, when civil society in CEE countries was still struggling with challenges related to political and economic transitions. Therefore, the new conditions they are facing today do not prevent them from supporting democracy elsewhere, as an example of the programme under study shows. It is also an example of bypass assistance, which adds to knowledge of how donors can shape (political) development in recipient countries (Dietrich Citation2013, Citation2021; Dietrich and Wright Citation2015).

The results from our evaluation the impact of one of the long-term civic education programmes directed at young people from post-Soviet countries, suggest that such approaches may indeed be fruitful. Matching closely the content of the survey with the desired outcome of the programme we were able to find that training experiences led to some changes among young participants in line with the democratic values and practices conveyed in the programme.

Speaking of fruitfulness, we also place great hopes on future research, which can improve upon the present work in several key ways. First, we hope that future work will improve upon the present work and succeed where we have not in providing true causal evaluations of civic education programmes. In planning partnerships with NGOs, it is important to recognise that NGOs may be under pressures to manage donors’ expectations – and impassive to the concerns about causal inference of academics –which could result in a selection of the “best and brightest” for programme participation. Beyond a successful randomisation – even if around the cut-off – good causal inference of programme outcomes hinges on the ability to survey (with good coverage) not only those who participate, but also those who do not. Additionally, with regards to participant selection, we also must wonder whether the kind of participant we observed in our study are in fact the ones who might benefit the most. As we have shown, there is evidence that selected programme participants are already very capable and favourable to democracy prior to even beginning the programme, which we suspect has led the impact of the programme to appear to be relatively muted. While fortunately even very capable programme participants seem to benefit, in may be the case that other “less prepared” participants might benefit to an even greater degree.

Second, while “participants’ feelings” about democracy and their own capacity to shape public life have been shown to be of great importance for fomenting engagement, ideally future studies would also attempt to capture more concrete outcomes. For example, asking participants about their implementation intentions – what will they do with their newfound knowledge once they return home? Moreover, as difficult as it may be, future studies measuring the impact of youth programmes should try to connect better how changes in self-reported perceptions and opinions of young participants in civic education programmes indeed translate into activism, including by connecting micro-level and macro-level approaches more effectively. Even if youth programmes can affect the political activism of their participants, the impact those programmes can have on the participatory levels of societies as a whole is not so straightforward. Nevertheless, although it is exciting to find out whether former participants voted, participated in a debate or protest, or became more interested in politics, there is still the problem of attribution as it is uncertain to what extent that increased participation was due to the democracy promotion efforts if not other factors. Undoubtedly, there is no easy way to evaluate the democracy promotion programmes directed toward young people. However, there is something that can be learned from this study: programmes directed at youth from post-Soviet countries by organisations from neighbouring countries do attempt to generate politically engaged youth by creating a space and a platform for civic skills and mindedness development, which otherwise would not be possible in their own countries.

Acknowledgements

The earlier versions of the article was presented at the workshop entitled “Experiments in Foreign Aid Research Workshop”, The University of California, Washington Centre, Washington, USA, and at the conference on “Youth Mobilisation and Political Change Participation, Values, and Policies Between East and West” organised by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) in Berlin, Germany. The authors would like to thank all for the comments received during the writing process of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paulina Pospieszna

Paulina Pospieszna is an Associate Professor of political science at the Adam Mickiewicz University of Poznan, Poland. She received her Ph.D. (2010) in Political Science from the University of Alabama and worked as a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Konstanz and the University of Mannheim, Germany. Her main research interest: democracy promotion, democratisation, aid and sanctions as foreign policy tools. Recently, she has published a book Democracy Assistance Bypassing Governments in Recipient Countries Supporting the “Next Generation”, Routledge.

Patrick Lown

Patrick Lown is a Research Fellow in the Department of Government at the University of Essex in England. He received his PhD in 2015 from Stony Brook University. His primary research interests include the public opinion of inequality and social welfare and the expression of empathy broadly in politics. His work has been published in scholarly journals including the American Journal of Political Science, Political Psychology, and the British Journal of Political Science.

Simone Dietrich

Simone Dietrich is Associate Professor in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Geneva, Switzerland. She is the author of States, Markets, and Foreign Aid published by Cambridge University Press in 2021. Her articles have appeared in leading political science and international relations journals including, among others, the Journal of Politics, International Organization, International Studies Quarterly, and World Development. Her research explores how donor governments make decisions about foreign aid, how aid promotes development and democratic change in recipient countries, and how international organizations shape the creation and development of international development practices.

Notes

1 Democracy promotion programmes led by NGOs tend to support existing pro-democracy groups within non-democratic countries (e.g. NGOs and other civil society actors), but also to focus directly on the role of youth participation. This is especially the case if cooperation with independent organizations is difficult or impossible because of restrictions placed on them by the government of their country, such as in Belarus (Carothers and Brechenmacher Citation2014; Dupuy, Ron, and Prakash Citation2016; Gershman and Allen Citation2006).

2 Other terms are also used such as education for “democratic citizenship”, “civic education programmes”, or “education for active participation” activities.

3 The selection of NGOs from four CEE countries that promote youth assistance in Post-Soviet countries was made in three steps. First, we selected NGO associations in four CEE countries affiliated with the EU's umbrella organization of national associations engaged in developmental and humanitarian aid including democracy assistance, CONCORD, which is the European confederation of relief and development NGOs. The following associations in Central and Eastern European countries are members of this confederation: FoRS (the Czech Forum for Development Cooperation), the Hungarian Association of NGOs for Development and Humanitarian Aid (HAND), the Platforma MVRO in Slovakia, the Grupa Zagranica in Poland. Then, we selected NGOs from the CEE countries that are active in the field of youth assistance in Post-Soviet countries, including Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine. Finally, the selection of organizations was supplemented by internet searches and recommendations from fieldwork in these countries. In order to create a database of all youth programmes from the selected organizations, we used website materials, programme descriptions, reports and other information obtained from organizations and donors.

4 We did not find any such programmes implemented by Hungarian NGOs.

5 The main coordinators have been two organizations: The Leaders for Change and the Borussia Foundation, which are responsible for the substantive and organizational side of the programme. Employees of both organizations form the “STP Team” consisting of people with experience in the implementation of Eastern programmes, knowledge about the specificity of the region and contacts in the countries from which beneficiaries of the programme come from (Russia, Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine).

6 We divided applicants into three groups: those who will be accepted into the programme for certain (i.e. without randomization), those who will reject from the programme for certain because do not fulfil the criteria and those who will have a random chance of being accepted into the programme. As the result, the access to the programme still relied on a student's qualifications, because the group people fell into depended upon the scores and place on the ranking list. The lottery around the cutoff was conducted separately for each nationality because the ranking list of students was prepared for each nationality and was based on the evaluation in three categories.

7 As an example, the allocation for Ukrainian young people applying to the programme. Since the goal was to invite 100 young people from four countries, and usually the greatest number of applicants are Ukrainians, the organization chose to accept 59 young people from Ukraine. All those with a place on the ranking list between 1 and 35 were accepted outright and those with place 86 on the raking list and below were rejected. The access to the programme was randomized for students on ranking list 36–85. However, those on the ranking list between 36 and 60 have a 60% probability of being accepted to the programme because they had greater qualifications while those with a place between 61 and 85 have 40% chance of getting into the programme and they were randomly selected.

8 While this was not ideal because of concerns regarding both possible experimenter demand effects as well as being able to assess the durability of the treatment effects, it was necessary in order to collect the post-treatment data while ensuring participants’ safety and relative candour. Participants may not have been able to answer the same way upon returning to their own countries, for fear of reprisal.

9 Inspiration for the formulation of questions came from established and long-running surveys such as the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and World Values Survey as well as work by Ferrin and Kriesi (Citation2016), Dalton (Citation2014), and Vráblíková (Citation2017). The full list of survey items may be found in the Appendix.

10 In general, there were around 500 candidates applying in each wave of the programme, which give us around 2000 candidates in four waves of the programme Spring 2015–Fall 2016. Unfortunately, since the survey was not obligatory, only around 700 baseline survey was filled out, which gives 30% survey response rate. There were around 440 participants out of 2000 candidates selected to the programme the survey response rate was also 30% thus we have around 140 baseline surveys. Additionally, we were granted General Data Protection Regulation approval, so NGOs did not allow us to have access to data which would also help us better identify the participants in the control group.

11 Question wording for this all-other items are available in the Appendix.

12 We consider these to be beliefs as opposed to political knowledge because while some questions have clearer answers than others, i.e., some elements participants were asked about are more essential to democracy, even among scholars the hallmarks of democracy are contested and to some degree contested.

References

- Ariotti, M., S. Dietrich, and J. Wright. 2021. “Foreign Aid and Judicial Autonomy.” Review of International Organizations. doi: 10.1007/s11558-021-09439-9.

- Armingeon, K. 2007. “Political Participation and Associational Involvement.” In Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, edited by J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, and A. Westholm, 358–384. London: Routledge.

- Arriola, L., A. Matanock, M. Travaglianti, and J. Davis. 2017. “Civic Education in Violent Elections: Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire’s 2015 Election.” https://cega.berkeley.edu/resource/civic-education-in-violent-elections-evidence-from-cote-divoires-2015-election/.

- Banks, J. A., Cherry A. Mcgee Banks, Carlos E. Cortés, Carole L. Hahn, Merry M. Merryfield, Kogila A. Moodley, Stephen Murphy-Shigematsu, Audrey Osler, Caryn Park, and Walter C. Parker. 2004. Democracy and Diversity: Principles and Concepts for Educating Citizens in a Global Age. Seattle: Center for Multicultural Education, University of Washington.

- Bermeo, S. B. 2011. “Foreign Aid and Regime Change: A Role for Donor Intent.” World Development 39 (11): 2021–2031.

- Berti, B., K. Mikulova, and N. Popescu. 2015. Democratization in EU Foreign Policy. New Member States as Drivers of Democracy Promotion. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bush, S. 2015. The Taming of Democracy Assistance: Why Democracy Promotion Does Not Confront Dictators. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carnaghan, E. 2007. Out of Order: Russian Political Values in an Imperfect World. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Carothers, T., and S. Brechenmacher. 2014. Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Dalton, R. 2011. Engaging Youth in Politics: Debating Democracy’s Future. New York: IDEBATE Press.

- Dalton, R. 2014. Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

- Diamond, L. 2017. “Reviving the Global Democratic Momentum.” In Does Democracy Matter? The United States and Global Democracy Support, edited by A. Basora, A. Marczyk, and M. Otarashvili, 119–134. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dietrich, S. 2013. “Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocation.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (4): 698–712.

- Dietrich, S., and J. Wright. 2015. “Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Changes in Africa.” The Journal of Politics 77 (1): 216–234.

- Dietrich, S. 2021. States, Markets, and Foreign Aid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Diuk, N. 2012. The Next Generation in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan Youth, Politics, Identity, and Change. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Duflo, E., R. Glennerster, and M. Kremer. 2007. “Using Randomization in Development Economics: A Toolkit.” In Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 4, edited by T. Schults and J. Strauss, 3895–3962. North Holland: Elsevier Science.

- Dupuy, K., J. Ron, and A. Prakash. 2016. “Hands Off My Regime! Governments’ Restrictions on Foreign Aid to Non-Governmental Organizations in Poor and Middle-Income Countries.” World Development 84: 299–311.

- Ekiert, G., J. Kubik, and M. A. Vachudova. 2007. “Democracy in the Post-Communist World: An Unending Quest?” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 21 (1): 7–30.

- Ferrin, M., and H. Kriesi. 2016. How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Finkel, S. E. 2002. “Civic Education and the Mobilization of Political Participation in Developing Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 64 (4): 994–1020.

- Finkel, S. E. 2014. “The Impact of Adult Civic Education Programmes in Developing Democracies.” Public Administration and Development 34: 169–181.

- Finkel, S. E., and A. E. Smith. 2011. “Civic Education, Political Discussion and the Social Transmission of Democratic Knowledge and Values in a New Democracy: Kenya 2002.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (2): 417–435.

- Finkel, S. E., J. Horowitz, and R. T. Rojo-Mendoza. 2012. “Civic Education and Democratic Backsliding in the Wake of Kenya’s Post-2007 Election Violence.” The Journal of Politics 74 (01): 52–65.

- Foa, Roberto Stefan, and Yascha Mounk. 2016. “The Democratic Disconnect.” Journal of Democracy 27 (3): 5–17.

- Freyburg, T., S. Lavenex, F. Schimmelfennig, T. Skripka, and A. Wetzel. 2009. “EU Promotion of Democratic Governance in the Neighbourhood.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (6): 916–934.

- Gershman, C., and M. Allen. 2006. “The Assault on Democracy Assistance.” Journal of Democracy 17 (2): 36–51.

- Glennerster, R., and K. Takavarasha. 2013. Running Randomized Evaluations: A Practical Guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Green, A. T., and R. D. Kohl. 2007. “Challenges of Evaluating Democracy Assistance: Perspectives from the Donor Side.” Democratization 14 (1): 151–165.

- Guasti, Petra, and Lenka Bustikova. 2020. “In Europe’s Closet: The Rights of Sexual Minorities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” East European Politics 36 (2): 226–246.

- Henry, L. A. 2006. “Shaping Social Activism in Post-Soviet Russia: Leadership, Organizational Diversity, and Innovation.” Post-Soviet Affairs 22 (2): 99–124.

- Himmelmann, Gerhard. 2013. “Competences for Teaching, Learning and Living Democratic Citizenship.” In Civic Education and Competences for Engaging Citizens in Democracies, edited by Murray Print and Dirk Lange, 3–7. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Horký-Hlucháň, O., and S. Lightfoot. 2013. Development Policies of Central and Eastern European States from Aid Recipients to Aid Donors. London: Routledge.

- Hyde, S. D. 2015. “Experiments in International Relations: Lab, Survey, and Field.” Annual Review of Political Science 18: 403–424.

- Korosteleva, E. 2012. “Questioning Democracy Promotion: Belarus’ Response to the ‘Colour Revolutions’.” Democratization 19 (1): 37–59.

- Kotwas, M., and J. Kubik. 2019. “Symbolic Thickening of Public Culture and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism in Poland.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 33 (2): 435–471.

- Krawatzek, F. 2017. “Political Mobilisation and Discourse Networks: A New Youth and the Breakdown of the Soviet Union.” Europe-Asia Studies 69 (10): 1626–1661.

- Kuzio, T. 2006. “Civil Society, Youth and Societal Mobilization in Democratic Revolutions.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 39: 365–386.

- Licht, A. A. 2010. “Coming Into Money: The Impact of Foreign Aid on Leader Survival.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54: 58–87.

- Magyar, Bálint, and Bálint Madlovics. 2020. The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes: A Conceptual Framework. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Manning, N., and K. Edwards. 2014. “Does Civic Education for Young People Increase Political Participation? A Systematic Review.” Educational Review 66 (1): 22–45.

- Moehler, D. C. 2010. “Democracy, Governance, and Randomized Development Assistance.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 628: 30–46.

- Morton, R., and K. Williams. 2006. “Experimentation in Political Science.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by J. Box-Steffensmeier, D. Collier, and H. Brady, 339–358. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mvukiyehe, E., and C. Samii. 2017. “Promoting Democracy in Fragile States: Field Experimental Evidence from Liberia.” World Development 95: 254–267.

- Nikolayenko, O. 2007. “The Revolt of the Post-Soviet Generation: Youth Movements in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine.” Comparative Politics 39 (2): 169–188.

- Norris, P. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Osler, Audrey. 2012. “Citizenship Education in Europe.” In Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education, edited by J. A. Banks, Vol. 1, 375–378. London: Sage.

- Petrova, T. 2014. From Solidarity to Geopolitics: Support for Democracy among Postcommunist States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Petrova, T., and P. Pospieszna. 2021. “Democracy Promotion in Times of Autocratization. The Case of Poland, 1989–2019.” Post-Soviet Affairs. doi: 10.1080/1060586X.2021.1975443.

- Pishchikova, K. 2010. Promoting Democracy in Postcommunist Ukraine: The Contradictory Outcomes of US Aid to Women’s NGOs. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Pospieszna, P. 2014. Democracy Assistance from the Third Wave: Polish Engagement in Belarus and Ukraine. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Pospieszna, P. 2019. Democracy Assistance Bypassing Governments in Recipient Countries Supporting the “Next Generation.” Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pospieszna, P., and A. Galus. 2020. “Promoting Active Youth: Evidence from Polish NGO's Civic Education Program in Eastern Europe.” Journal of International Relations & Development 23: 210–236.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and H. Scholtz. 2008. “EU Democracy Promotion in the European Neighbourhood: Political Conditionality, Economic Development and Transnational Exchange.” European Union Politics 9 (2): 187–215.

- Schulz, Wolfram, Julian Fraillon, John Ainley, Bruno Losito, and David Kerr. 2008. International Civic and Citizenship Education Study. Assessment Framework. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

- Schwartz, M., and H. Winkel. 2016. Eastern European Youth Cultures in a Global Context. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Scott, J. M., and C. A. Steele. 2011. “Sponsoring Democracy: The United States and Democracy Aid to the Developing World, 1988—2001.” International Studies Quarterly 55 (1): 47–69.

- Solhaug, T. 2013. “Trends and Dilemmas in Citizenship Education.” Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education 1: 180–200.

- Sundstrom, L. 2006. Funding Civil Society: Foreign Assistance and NGO Development in Russia. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Szent-Iványi, B. 2014. “The EU's Support for Democratic Governance in the Eastern Neighbourhood: The Role of Transition Experience from the New Member States.” Europe-Asia Studies 66 (7): 1102–1121.

- Szent-Iványi, Balázs, and Z. Végh. 2018. “Is Transition Experience Enough? The Donor-Side Effectiveness of Czech and Polish Democracy Aid to Georgia.” Democratization 25 (4): 614–632.

- Terriquez, V. 2015. “Training Young Activists Grassroots Organizing and Youths’ Civic and Political Trajectories.” Sociological Perspectives 58 (2): 223–242.

- Tolstrup, J. 2014. “External Influence and Democratization: Gatekeepers and Linkages.” Journal of Democracy 25 (4): 126–138.

- Torney-Purta, J., R. Lehman, H. Oswald, and W. Schultz. 2001. Citizenship and Education in Twenty-Eight Countries: Civic Knowledge and Engagement at Age Fourteen. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. http://www.iea.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Electronic_versions/CIVED_Phase2_Age_Fourteen.pdf (8 October, 2021).

- (UNESCO) United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2014. Global Citizenship Education, Preparing Learners for the Challenges of the 21st Century: available at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002277/227729E.pdf.

- Van Der Meer, TWG, and E. J. Van Ingen. 2009. “Schools of Democracy? Disentangling the Relationship Between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 48: 281–308.

- Vráblíková, K. 2017. What Kind of Democracy? Participation, Inclusiveness and Contestation. New York: Routledge.

- Wilson, A. 2006. “Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, NGOs and the Role of the West.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 19 (1): 21–32.

- Wong, M. C. S., T. C. M. Lau, and A. Lee. 2012. “The Impact of Leadership Program on Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy in School: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” PLoS One 7 (12): e52023.

Appendix

Table A1. Types of youth projects in post-Soviet countries.

Results of the Survey of Young Participants from Post-Soviet Countries in Civic Education Programme run by Polish NGOs 2014–2018.

Table A2. OLS regression estimates for programme effects.

Table A3. OLS regression estimates for programme effects by programme wave.

Table A4. OLS regression estimates for programme effects by country wave.

Survey Content of Civic Education Programme Measuring Perceptions of Young People from the Post-Soviet Countries

Country:

Belarus

Moldova

Russia

Ukraine

Beliefs about Democratic Institutions [Very important to not important; 4pts]:

dem_int01: Free and fair elections

dem_int02: Elections give people the opportunity to punish bad government by removal from power

dem_int03: The limited number of terms can serve a person on a high state position

dem_int04: The ability to choose between parties representing different political options

dem_int05: Independence of media from government

dem_int06: Media pluralism

dem_int07: The delegation by the state broadest possible responsibilities to the local government

dem_int08: The delegation by the state widest possible competence of the social organizations/ NGOs

dem_int09: Consultation with the public of important state decisions

dem_int10: Protection of property rights by the State

dem_int11: Freedom of running business free from State interference

dem_int12: Protection of workers' rights

dem_int13: Ensuring by the state equal access to education

dem_int14: State funding for health care, science, culture

dem_int15: The state ensuring fair living conditions for the poorest

dem_int16: An active state policy in the fight against social inequalities

dem_int17: Protection of minority rights by the State

dem_int18: The freedom to choose the residence in the country or abroad

dem_int19: Equality of all citizens before the law

dem_int20: Freedom of expression and the right to organize

dem_int21: Little state intervention in the lives of citizens

dem_int22: The independence of social organizations/ NGOs from the state

dem_int23: The supremacy of citizen's rights over the interests of the state

dem_int24: Independence of the judiciary

dem_int25: Separation of judiciary, executive and legislative branches

Support for democracy [Fully Agree – Fully Disagree; 4pt]:

dem_att01: Democracy has an advantage over all other forms of governments

dem_att02: Democracy leads to the well-being of citizens

dem_att03: Democracy has a positive impact on the economic development of the state

dem_att04: The development of democracy is desirable in all countries of the world, regardless of their political tradition and culture

dem_att05: Democracy is a good regime for my country

dem_att06: Sometimes non-democratic government can be preferable to a democratic one

dem_att07: Governments based on strong leadership are better than democratic ones

Attitudes toward the EU [Fully Agree – Fully Disagree; 4pt]:

EU_att01: EU membership brings more benefits than costs

EU_att02: My country should join the European Union

EU_att03: I consider myself as European, I think I belong to the culture and history of Europe

EU_att04: With the accession the countries lose their national identity

EU_att05: Membership in the EU has a positive impact on the economic development of the state

EU_att06: the European Union is an instrument of domination of strong over weak countries

EU_att07: Membership in the EU builds and strengthens ties between residents of the member states

EU_att08: EU gives residents of the community states opportunities for professional development, education, etc.

Obedience to authority:

auth01: Obedience and respect for authority are the most important values that should be transferred to the children

auth02: You should always show respect to those who exercise authority

Efficacy:

efficacy01: People like me do not have any influence on what the government is doing and politicians

efficacy02: Most politicians, regardless of what they say, care only about their career

efficacy03: Key political decisions are taken in secret situations

Preference for tradition:

tradition: My country should not emulate the standards of the West, but rely primarily on its own traditions and experiences

Preference forstrong leaders:

strength01: In brief, people are divided into weak and strong

strength02: A strong leader can do more for the country than the law, discussions, consultations

Preference for religion:

relig01: Values based on religion should constitute the moral basis in my own country

Meritocracy:

merit: People who have achieved nothing in life, do not have enough will