ABSTRACT

We take the demand-side perspective of Sputnik V, trying to answer why facing vaccine scarcity, some countries opt for Sputnik V, and others do not. To show how the pandemic tests the institutional safeguards and soft guardrails of liberal democracy, we compiled a unique dataset and combined statistical analysis and case studies. While our quantitative analysis shows that the illiberalism of the party in power is the main explanatory factor in the import of Sputnik V, our qualitative case studies illustrate under what conditions institutional guardrails withstand the pressure of populist and illiberal leaders.

Introduction

The COVID19 pandemic put additional pressure on governments and democracy. Governments were faced with health and economic crises of unprecedented proportions. Simultaneously, the pandemic tested the institutional safeguards and soft guardrails of liberal democracy (cf. Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2020).Footnote1 The extent to which democratic governments will adhere to the safeguards and guardrails in a crisis or instrumentalize the pandemic domestically or internationally remains open. Domestically, leaders like Viktor Orban of Hungary instrumentalized the pandemic to consolidate power, further undermining political and civil liberties, as well as the rule of law.Footnote2 Internationally, leaders like Vladimir Putin seized the moment to strengthen the global reach of their country. With vaccine scarcity and vaccine nationalism of major developed countries, a vacuum emerged in the first half of 2020 in which Russia (China and India) could use vaccines as soft power tools.

Given the absence of approval by the EU drug regulatory body, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the many questions surrounding Sputnik V (inconsistencies in production, limited transparency, and scientific evidence of efficacy) (Logunov et al. Citation2021). The purchase of Sputnik V is a temporary suspension of existing safeguards and guardrails. This can take different forms – arbitrarily changing institutional safeguards such as legally defined vaccine approval procedures or suspending soft guardrails – for example, blindsiding coalition partners in an attempt to score political points or fabricating statements never uttered. The leaders of Serbia and Hungary employed the earlier to import Sputnik V. The leaders of Slovakia and Hungary used the latter – instrumentalizing the import of Sputnik V against the opposition.

In this way, the purchase of Sputnik V tests the safeguards and guardrails of liberal democracy. When safeguards and guardrails function, co-equal branches of power, administration, and the rule of law, the opposition and media can contain illiberal populists trying to undermine them (cf. Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018; Weyland Citation2020; Pirro and Stanley Citation2021). In most countries, safeguards and guardrails withstood the pressure from political elites during the pandemic. Even if populists in Austria, Italy, Germany, and the Czech Republic called for importing Sputnik V, they did not succeed because those defending adherence to the existing institutional rules and democratic norms prevailed.

Eight countries – Serbia, Hungary, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Montenegro, Slovakia, North Macedonia, San Marino and Turkey imported Sputnik V. Six of these countriesFootnote3 share an important trait – their democracy has been eroding recently, and they are governed by illiberals and populists (cf. Guasti and Buštíková Citation2022). In the absence of EMA approval, in order to import Sputnik V, existing rules had to be changed or broken. In these six countries, safeguards and guardrails did not hold.

Slovak PM Igor Matovič is an example of breaking soft guardrails. Matovič took a political gamble on Sputnik V – to boost his declining popularity, Matovič imported Sputnik V behind the back of his coalition partners. Consequently, the public and political pressure forced Matovič to resign. The calculus of increasing popularity by importing Sputnik V backfired. Czech PM Andrej Babiš was open to taking the same gamble. Alas, in his case, the safeguards and guardrails resisted the pressure he exercised long enough for the context and calculus to change. The two examples show how populist and illiberal leaders around the world test safeguards and guardrails during a pandemic. Focusing on the purchase of Sputnik V in Europe allows us to understand better when and under what conditions the safeguard and guardrails of liberal democracy hold and when they fail.

This paper focuses on the political side of Sputnik V and takes the demand side perspective (for another perspective, see Naczyk and Ban Citation2022). The question this paper aims to answer is, why some countries facing the same (or similar) vaccine scarcity – especially EU countries that are part of the EU vaccine strategyFootnote4 and regulatory framework – opt for Sputnik V, and others do not. To answer this question, we combine literature on varieties of (structural and elite) linkages and democratic erosion during a pandemic.

The literature on structural linkages provides a possible explanation – authoritarian linkage based on ties between similar regime types and geopolitical and economic interests. According to the regime proximity model, less democratic regimes with geopolitical and economic ties to Russia should have imported Sputnik V (a similar argument could be used for China and its vaccine). Some did, but not all. Alternatively, the literature on elite linkages offers a more comprehensive explanation of linkage as a strategic action by political elites. Many leaders called for importing Sputnik V, but not all acted on their rhetoric. Those out of power, like Marine Le Pen of France, did not influence the import of Sputnik V. Others like Matteo Salvini of Italy, Sebastian Kurz of Austria, or Andrej Babis of the Czech Republic had the power but were held back from importing Sputnik V by institutional safeguards and soft guardrails (cf. Anghel and Jones Citation2022).

From the literature on democratic erosion, we derive a demand-side explanation. Countries where the pandemic is severe and countries with illiberal leaders will be prone to import Sputnik V due to their leaders’ fear of losing popular support. However, not all countries facing severe pandemic (e.g. Spain, Portugal) and with populist leaders in power (e.g. Italy, Czech Republic) imported Sputnik V. Hence, the line between populist and illiberal leaders in the pandemic ought to be drawn – while populists test the guardrails and safeguards, but do not prevail, illiberal leaders override institutional guardrails, democratic safeguards or both to import Sputnik V.

In order to answer the question of why some countries in Europe import Sputnik V and others do not, we compiled a unique dataset and combined statistical analysis and case studies to show how the pandemic tests safeguard and guardrails of liberal democracy. While our quantitative analysis shows that the illiberalism of the party in power is the main explanatory factor in the import of Sputnik V, our qualitative case studies illustrate under what conditions safeguards and guardrails hold withstanding the pressure by populist and illiberal leaders.

The article is structured as follows. First, we briefly outline the supply side of vaccine politics. Second, we combine the literature on democratic erosion during the pandemic with the literature on linkages to establish a theoretical framework for the demand side of vaccine politics. Third, we briefly outline our data, case selection, and method of operationalisation. Fourth, we present our findings – quantitative results of our logistic regression and qualitative analysis based on four shorter case studies focused on three countries that purchased Sputnik V and one that did not. Finally, in the conclusions, we summarise our findings and original contribution and outline future avenues for research on vaccine diplomacy and pandemic illiberalism.

The supply side of vaccine politics

In August 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccine was granted regulatory approval – Sputnik V.Footnote5 The Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) was tasked with managing the vaccine export.Footnote6 The first countries to register Sputnik V were Serbia, Belarus, and Argentina (all between December 21 and 30, 2020). Hungary utilised the regulatory approval by Serbia as justification for its approval, becoming the first EU country to approve Sputnik V in January 2021. In breach of EU rules requiring the approval of the European Medicine Agency (EMA), Hungary set an important precedent.

Subsequently, an increasing number of EU leaders aiming to offer their population a way out of the pandemic and to decrease the strain on the public health system and the economy were considering emergency approval of Sputnik V. Populist leaders such as Mateo Salvini (Italy), Marine Le Pen (France), Andrej Babiš (the Czech Republic), were pushing their domestic regulators to approve Sputnik V, before EMA.Footnote7

By April 2021, as the production of EMA-approved vaccines increased, the push to approve Sputnik V in Europe reduced significantly. The EU was able to secure 1.8 billion additional doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, the production issues were resolved, and mass vaccination was underway (by May 15, 2021, 35.5% of the EU population received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, by July 23, 2020, 67.5%).Footnote8

Public opinion in the EU continued to be divided on Sputnik V. The demise of the Slovak PM Igor Matovič indicated to other leaders the costs of circumventing safeguards and guardrails to take a chance on Sputnik V without EMA regulatory approval. For many non-EU countries, Sputnik V remained among the few available options (alongside Indian and Chinese vaccines). By April 2021, 64 countries worldwide had approved Sputnik V, yet the questions about its safety and efficacy remain.Footnote9

State of the art

Pandemic illiberalism

We use the term illiberalism to denote a set of principles opposed to (political) liberalism and its core values – respect for pluralism (including political opposition), minority rights, ideological heterogeneity, and rejection of political violence (cf. for a conceptual examination of the term Laruelle Citation2022; cf. Lührmann and Rooney Citation2020). We use the term populism to denote both an ideology and a political strategy. Populism, as an anti-establishment ideology, promises redemption and articulates neglected grievances using the language of the people (Canovan Citation1999). The articulation occurs by identifying an antagonistic relationship with elites and offering hope (Spruyt et al. Citation2016, 336). While populism and illiberalism can be combined, they do not necessarily come hand in hand (Laruelle Citation2022; Weyland Citation2020).

The pandemic represented a major challenge for contemporary democracies worldwide (Afsahi et al. Citation2020). It tested the institutional safeguards on a domestic, regional and global level (Levine Citation2020; Owen Citation2020; Prainsack Citation2020). COVID19 emergency politics had a corrosive effect on weakening institutional safeguards – democratic institutions (Rapeli and Saikkonen Citation2020). In many countries, the pandemic “layered upon” existing challenges: growing frustration with democratic politics (Gaskell and Stoker Citation2020), rising populism and illiberalism (Lührmann and Rooney Citation2020), and exacerbated existing inequalities (Honig Citation2020; King et al. Citation2020; Nolan Citation2021) and prevented resolution of democratic crisis (Weiffen Citation2020).

The pandemic strengthened the executive branch and experts, while national parliaments were mostly marginalised (Merkel Citation2020) and civil society undermined, bypassed, or suppressed (Levine Citation2020). Attempts at executive aggrandisement were omnipresent – in established democracies, in democracies in various stages of consolidation, and in hybrid and competitive authoritarian regimes (Guasti and Buštíková Citation2022; Weiffen Citation2020). Democratic backsliding occurred worldwide (PanDem Citation2021), particularly across Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia (NIT Citation2021).

In Central and Eastern Europe, increasingly illiberal populist leaders like Viktor Orban instrumentalized emergency to suspend core civil rights and liberties and increase executive aggrandisement (Guasti Citation2020a; NIT Citation2021). Expertise was often used as a shield against accountability (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). Epidemiologists and public health officials gained a significant degree of trust yet remained largely politically unaccountable for their advice (cf. Hartikainen Citation2021). Leaders could dismiss experts to avoid political consequences. Institutional safeguards – especially the rule of law and the checks by co-equal branches of power – parliamentary and judicial oversight were critically important in preventing democratic erosion (Guasti Citation2020b). Soft guardrails, especially the principle of forbearance – deliberate act of self-restraint and underutilisation of power by those elected to office (Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018), were similarly essential, especially as the states of emergency significantly enlarged the scope of this power.

Illiberal leaders proceeded to dismantle safeguards and often displayed disregard for soft guardrails. While populism itself is not illiberal, in power, it often manifests illiberal tendencies – it weakens checks and balances, undermines accountability, facilitates centralisation of power, and transforms opposition into the enemy of the people (Ruth-Lovell et al., Citation2019).

In CEE, liberal democracy declined significantly (NIT Citation2021). Hungary moved ever closer to a dictatorship (cf. Bruszt Citation2020), and Poland undermined the rule of law and media freedom (NIT Citation2021). A combination of institutional safeguards and soft guardrails is necessary to prevent democratic erosion (cf. Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018). In CEE, only in a few countries do the institutional safeguards and soft guardrails of liberal democracy prove resilient.

Pandemics test every government but present an additional challenge to populist leaders who have pledged to reinstall the people at the centre of democracy (Kaltwasser Citation2014) and whose anti-establishment message focuses on the incompetence of their established opponents (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). Populists in power during a pandemic face an ultimate test – to function in a real crisis rather than in a crisis they manufactured. In a pandemic, with power comes responsibility – finding solutions becomes essential to maintaining support and targeted social policies have only limited power to deflect from the omnipresent threat of the pandemic (cf. Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020; Hartikainen Citation2021).

In the first half of 2020, after an initial “rally around the flag” during the first wave of the pandemic, the pressure on governments to lift strict mitigation measures increased. (Populist) leaders who succumbed to their instinct to follow the people’s will and put responsiveness over responsibility ended up with a significantly worsened pandemic situation (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). The only rational and safe way out of frequent lockdowns and states of emergency was vaccination. Nevertheless, vaccine scarcity prevailed until late spring 2021 in the EU and was largely unavailable for the countries in the Global South or on the European periphery.

In this situation, governments faced a choice: to order Sputnik V without EMA regulatory approval – thus bypassing existing regulatory frameworks – or to wait for approval by a major regulatory body such as EMA while hospitals were filling up, people were dying, and the economy was declining (Simons et al. Citation2022). In this context, Sputnik V offered a possible path, breaking of the rules by importing Sputnik V.

Autocratic linkages in the era of global pandemic

The already mentioned consequences of the pandemic must be understood in the context of the transformation of global politics over the last decades. In the first decade after the Cold War, actors who sought to develop and promote democracy in the world dominated global politics (Levitsky and Way Citation2010). However, during the second decade of this century, the influence of authoritarian powers began to grow again (Hyde Citation2020).

The extant literature explains the change in global politics by combining two factors. First, the declining influence of the West, as many Western democracies began to prioritise more pragmatic geopolitical interests instead of promoting democracy (Brownlee Citation2012) or were unable to prevent the collapse of democracy in countries such as Hungary and Nicaragua (Levitsky and Way Citation2020; Bílek Citation2021). Second, authoritarian powers learned and adapted (Tansey Citation2016). As a result, autocracies learned to cooperate more effectively at the economic, repressive, and political levels, thus undermining democratisation efforts worldwide (Yakouchyk Citation2019).

The contemporary forms of authoritarian cooperation are often subtler and more sophisticated compared to the past. For example, unlike their historical counterparts, contemporary authoritarians do not simply provide weapons or soldiers but rather are experts in electoral manipulation (Tansey Citation2016) or share insights about undermining opposition and civil society legislatively (Bader Citation2014; Gilbert and Mohseni Citation2018). Moreover, unlike in the past, the main motivation is not ideology but pragmatic politics rooted in economic and geopolitical interests – present-day Russia is strategic in forming ties to other countries without ideology (Brownlee Citation2017; Yakouchyk Citation2019).

The authoritarian foreign policy aims to prevent the collapse of existing authoritarianism (Whitehead Citation2014) and deepen its influence in regimes at the crossroads between democracy and authoritarianism. Achieving the collapse of a stable democracy through authoritarian linkage is very difficult, and the influence of authoritarian powers is relatively limited in this regard (Brownlee Citation2017). Contemporary Russia is trying to limit the West’s influence and strengthen its linkages (Yakouchyk Citation2019). Sputnik V can play a role in this effort, especially under vaccine scarcity.

One of the main reasons it is difficult for authoritarian regimes to assert their influence in stable democracies is that they need elite allies. While factors such as history, geographic proximity, or common trade ties influence the likelihood of strong linkages between two countries, these factors are often given and change little over time. However, elite linkages between countries are much more dynamic, and actors play a key role in shaping them. Tolstrup (Citation2014) identifies the three most important types of such actors: ruling political elites, the opposition and non-governmental sector, and economic elites. The ruling elites are the most important, but the latter two categories cannot be underestimated either, as they can speak to the shape of foreign policy linkages (cf. Mazepus et al. Citation2021).

Political calculus of illiberal elites

Why do some countries import Sputnik V without international regulatory approval (EMA) and others do not? Our explanation is rooted in the literature on elite-driven linkages between countries (Tolstrup Citation2014) and democratic erosion (Bermeo Citation2016; Weyland Citation2020). We propose illiberal political elites as the explanation for the purchase of Sputnik V. Sputnik V is facing issues – questions about stage two and stage three trials, efficacy, and a lack of documentation. As a result of the lack of regulatory approval by EMA, the chances for regulatory approval by domestic bodies in EU countries are (at best) limited. However, regulatory bodies in the countries that purchased Sputnik V have offered emergency approvals. We propose that this is not the result of scientific soundness but rather of the vulnerability of these regulatory bodies to the political pressure from illiberal leaders, who do not respect institutional safeguards and soft guardrails (Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018).

Today’s illiberal political elites came to power through competitive elections (Bermeo Citation2016), often winning over the electorate with populist rhetoric and hard-to-fulfil political promises (Mudde Citation2016). Their rule has often led to democratic backsliding (Cassani and Tomini Citation2019). Moreover, these leaders instrumentalized the pandemic for executive aggrandisement by undermining horizontal and diagonal accountability (Guasti and Buštíková Citation2022). While the safeguards and guardrails can contain populists, illiberal political elites do not respect the institutions and rules of democratic governance, and their relations with other liberal democracies tend to be strained.

Furthermore, in 2021 the vaccine nationalism of major powers has shown the limits of the linkage between democratic countries. Vaccine scarcity creates pressure on all leaders. Vaccine scarcity and pressure to maintain popular support have pushed populist political elites to risk more than their democratic counterparts. Populists and especially illiberal elites put a premium on preventing political defeat and departure from power, as the re-establishment of the rule of law could result in the criminalisation of the corruption and clientelism that accompanies their rule (cf. Magyar Citation2016).

In early 2021, with vaccines largely unavailable from the West, the populist and illiberal ruling elites have multiple incentives to take a chance on the Sputnik V vaccine: increased independence from the EU and maintaining domestic support. Finally, the factor of time and overall geopolitical context ought to be considered. The window for Russian Sputnik V diplomacy in Europe was relatively brief – based on the scarcity of Western vaccines. When given a choice, people in countries where Sputnik V is available prefer Western vaccines.Footnote10 Vaccine scarcity has been reduced, domestic vaccination levels increased, and Western countries and COVAX have made Western vaccines available to low and mid-level developing countries. Vaccine availability changes the calculus of illiberal elites and their opponents and weakens the attractiveness of the illiberal linkage to Russia. The illiberal ruling elites can be thwarted or significantly disrupted in their efforts to purchase Sputnik V by autonomous state institutions, a media critical of the government, or strong opposition.

H1: The higher the degree of illiberalism of the senior party in government, the higher the likelihood of a country’s import of Sputnik V.

Data, methods, operationalisation

Our study explains why some European countries imported the Sputnik V vaccine, and others did not. First, a logistic regression model is employed to test the effect of illiberalism on purchasing the Sputnik V vaccine on a dataset that included 41 European countries.Footnote11 Second, we used four shorter qualitative studies to elaborate our argument further – focusing on the actions of illiberal and populist leaders during a pandemic.

We select four cases to highlight the relationship between illiberalism and the purchase of Sputnik. First, we focus on Serbia, a non-EU country navigating vaccine scarcity by leveraging linkages to the West and the East (i.e. EU, Russia, and China, respectively). Second, we look at Hungary, an EU member state with a different calculus to importing the Russian vaccine. Third, we look at Slovakia, where the purchase of Sputnik V resulted in a political crisis. Fourth, we look at the Czech Republic, a country that considered but did not purchase Sputnik V – because institutional safeguards and soft guardrails constrained powerful illiberal actors. While these cases do not cover all countries, they cover sufficient variation across the 41 cases analyzed in our quantitative analysis.

Our dependent variable is dichotomous and indicates whether or not the country under analysis imported Sputnik V. We have collected data from the official website of Sputnik V and counterchecked it in the media.

The main explanatory variable in our study is the level of illiberalism of ruling political elites. We created this variable by first identifying senior parties in government using the Who Governs Europe dataset; second, using the V-DEM V-Party Dataset 2020 illiberalism index, we assigned the illiberalism index value for a given party (cf. Lührmann and Rooney Citation2020). The index combines four variables political opponents, political pluralism, minority rights, and the rejection of violence. The underlining rationale is the lack of commitment to democratic norms by a given party.Footnote12

We also provide alternative operationalisation of the main explanatory variable using the V-DEM Party Dataset 2021 variable political pluralism. This variable captures the interplay between institutional safeguards and soft guardrails as it tests the commitment of party leaders to democratic principles, including free and fair election, freedom of speech, media, assembly and association (Lindberg et al. Citation2022, 27). We assign the value from most recent elections prior to the pandemic to the senior party in government holding the office of the Prime Minister (parliamentary systems) or President (presidential systems).

Other contextual factors could influence the purchase of the Sputnik V vaccine. To address this, we include three control variables.Footnote13 The first one is the case fatality rate. The second one is the export level to Russia. The case fatality rate was expected to positively affect SPUTNIK V purchase because it increases pressure on leaders to solve vaccine scarcity. In addition, export to Russia was used as a pre-existing structural form of linkage, decreasing the resistance to soft Russian diplomacy. Finally, we also include the EU membership status. We expect this variable to negatively affect the Sputnik V import because the EU member states have better access to other vaccines. The summary statistics for all variables used in the analysis are presented in Appendix A.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis

The results of the analysis are exhibited in the . Six different models were created. First, we present a model for our argument and the three models for the three control variables, which we introduced in section 2.2. of the text. We also include the null model without any independent variables and one model with all independent variables.

Table 1. Logistic regression, odds ratio.

Our second model shows that a high case fatality rate did not increase the probability of the Sputnik V purchase. The possible explanation is that the case fatality rate is just an abstract and distant number for many people. What matters more for them is a personal perception of risk and experience with the current pandemic – namely, the extent to which the pandemic adversely affected the health and possibly life of those close to them (cf. Devine et al. Citation2021 for the review of the role(s) of trust in a pandemic). Thus, the expected pressure on the political leaders could be smaller than we expected.

The third model shows that exporting to Russia is not a sufficient explanation for purchasing the Sputnik V vaccine. The effect of international ties with Russia is small and statistically insignificant. The data clearly shows that most recipients of the Sputnik V vaccine have a surprisingly low trade exchange with Russia.Footnote14 Furthermore, the biggest exporters to Russia like Georgia, Ukraine and Lithuania, did not purchase the Sputnik V vaccine. It is also important to note that all three biggest exporters to Russia are neighbouring countries with shared history, political and economic ties, and a sizable ethnic Russian minority. Thus, here more complicated ties can interplay and undermine the role of export to Russia alone.

The fourth model indicates that the EU membership status decreases the country’s probability of purchasing the Sputnik V vaccine. For example, EU membership decreases the probability that a given country purchased the Sputnik V vaccine by about 55%. However, as we know, two EU countries of the 27 did purchase Sputnik V – Hungary and Slovakia. Hence EU membership alone – which here stands for the access to Western vaccines purchased in coordination, does not ensure compliance with EMA rules.

The last two models – model five and model six – confirm our theoretical expectations. The level of illiberalism of the main party in government has a positive and statistically significant relationship with the purchase of Sputnik V.Footnote15 Both models show that countries with governments controlled by illiberal parties were six times more likely to purchase Sputnik V than governments without a main illiberal party in government. Moreover, our results show that illiberalism overperforms case fatality rate and EU membership status regarding the effect size and statistical significance. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayes information criterion (BIC) scores show that the illiberalism model outperforms all the other models, confirming expectations about our theoretical argument. The presented hypothesis is, therefore, supported.

In order to test the extent to which our findings were affected by the operationalisation of some variables, we also built several models with alternative operationalizations of our explanatory variable and structural linkage(s). The results are exhibited in . In addition, we created four additional alternative models.

Table 2. Logistic regression, odds ratio.

The first two models use alternative operationalisation of our explanatory variable as anti-pluralism. Models one and two show that our explanation work and significantly increase the probability that a given country purchased the Sputnik V vaccine. The probability is smaller than our main analysis but still quite big and statistically significant.

Next, we tried to explore if the key is not structural linkage to Russia but the structural linkage to Hungary.Footnote16 For this reason, we included exports to Hungary instead of to Russia in the alternative models three and four. The third model shows that the countries with a high export level to Hungary were 2,3 more likely to purchase the Sputnik V vaccine than countries without strong economic ties to Hungary. The final alternative model (model four) indicates that this effect holds even in the full model, including all variables.

However, a few additional facts ought to be mentioned. First, this model shows that economic ties to Hungary could be a possible explanation, but even in this situation illiberalism of the main government party preserves its explanatory power. Second, the data about export to Hungary clearly show that these ties exist mainly between Hungary and countries with significant historical ties and the presence of Hungarian ethnic minorities on their territory. Thus, these ties are historical rather than a product of possible authoritarian linkage between the current Hungarian government and its counterparts from countries such as Slovakia and Romania (for details, see Appendix B, an overview of exports to Russia, China and Hungary). Compared to Russia and China, contemporary Hungary does not primarily form its structural authoritarian linkages – operationalised here as economic linkage in line with the literature (cf. Brownlee Citation2017) – via trade due to its size. Instead, its ties are based on ideological proximity with the main party in the government with fellow “illiberals”.

Case studies

We supplement our quantitative analysis with four case studies to illustrate how the pandemic tests the institutional safeguards and soft guardrails of liberal democracy. In the case studies we focus on the ways in which safeguards and guardrails are tested and the conditions under which they are (un)able to contain the illiberal leaders.

Serbia

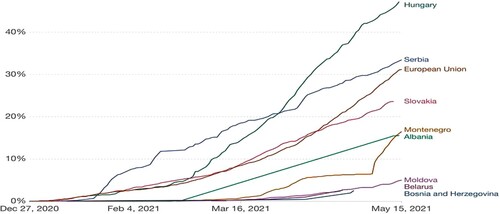

Serbia, led by President Aleksandar Vucic, pursued a diverse vaccine portfolio for its seven million citizens, including Pfizer BioNTech (US), AstraZeneca (UK), Sinopharm (China), Sputnik V (Russia), and signing up for the COVAX scheme (WHO). This reflects Serbian foreign policy, which has been balancing linkages to the West and the East.Footnote17 An illustration of this careful balancing is the vaccination of Serbian leaders – in December 2020, Prime Minister Ana Brnabic was one of the first to get the Pfizer BioNTech vaccineFootnote18, while President Aleksandar Vucic was vaccinated in April 2021 with Sinopharm.Footnote19 The Serbian vaccine acquisition strategy aligns with its foreign policy priorities (cf. Subotić Citation2016; Dimitrijević Citation2017). Overall the largest proportion of deployed vaccines in Serbia as of May 2021 were SinopharmFootnote20, followed by Pfizer, Sputnik V, and AstraZeneca ().Footnote21

Figure 1. Share of population with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine (in %).

Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data.

Serbia is a defective democracy experiencing increasingly sharper democratic backsliding (BTI Citation2020) over the last decade and during the pandemic (PanDEM Citation2021). Serbian politics is highly personalised, and the President, whose powers are formally limited, exercises significant control over the legislative process resulting in a de facto presidential system (FH Citation2021, C1).

During the pandemic, the President’s dominance of the executive and legislative branches undermined horizontal accountability mechanisms and fuelled executive aggrandisement. In June 2020, Serbia held parliamentary elections, which increased the SPP majority, partially due to a boycott by significant parts of the opposition (and thus low turnout) and partially due to unbalanced coverage favourable to the President, who campaigned heavily throughout the pandemic.

For Vucic pandemic was an opportunity to score political points in the elections, and the pro-government media portrayed Vucic as the “saviour of the nation” – by personally procuring medical equipment and vaccines. In his addresses, the President informed citizens about the number of respirators he secured. He also promised to secure equipment on the black market by forming black funds, stating, “And who’s going to stop me from doing so!” (Vasovic Citation2020). Furthermore, President Vucic declared that neither institutional safeguards nor soft guardrails would limit his endeavours.

Under these conditions, securing regulatory approval for Russian vaccines was not an issue. Importing non-EMA-approved vaccines was as much an attempt to score political points as a response to public pressure for opening and to prevent the health care system from overflowing if cases rise again (Vasovic Citation2020). In his attack on political opponents, the President insinuated that they have “robbed the country” and should “repent by donating large donations” (Vasovic Citation2020). Without significant veto players, taking a chance on Sputnik V (and Sinopharm) carried little political risk and high electoral benefits – the support for President Vucic and his party skyrocketed – in March 2020, President’s support increased from 44% to 61%, according to IPSOS. His party won 63.02% of the vote in the June 2020 elections, winning a majority of 188 seats in 250 seat parliament by adding 59 new seats.

Hungary

Unlike Serbia, Hungary is an EU member-state, thus under EMA regulatory authority for vaccine approval and part of the EU vaccine acquisition scheme. Still, faced with a rising case fatality rate, delayed vaccine delivery from the EU, and an underfunded health care system Viktor Orban used the regulatory approval by Serbian authorities to justify the approval of both Sputnik V and Sinopharm vaccines. On January 21, 2021, the Hungarian drug regulator – the National Institute of Pharmacy and Nutrition – used granted temporary six-month authorisation for Sputnik V and AstraZeneca vaccines in a fast-tracked procedure based on documentation provided by the vaccine producersFootnote22,.Footnote23 Unlike EMA authorisation, where liability remains with the manufacturer, the Hungarian emergency authorisation shifts the liability to the Hungarian government.Footnote24

Like Serbia, Hungarian foreign policy has long countered increasingly strained relationships with the EU with closer ties to Russia and China. The strained relationships to the West was reflected in Hungarian vaccine import. As of May 2021, Hungary imported 1.8 million doses of Sputnik V and 2.1 million doses of Sinopharm – in addition to 2.9 million doses of Pfizer BionNTech, 432.000 doses of Moderna, and 1.1 million doses of AstraZeneca. Hungary has administered 80.8% of vaccines delivered.Footnote25 As of May 12, 2021, 45.8% of Hungarians had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.Footnote26,Footnote27

Like Serbia, Hungarian democracy had declined since 2010 when Viktor Orban returned to power (BTI Citation2020; NIT Citation2021). The pandemic accelerated the democratic decay (Guasti and Buštíková Citation2022; cf. PanDem Citation2021). While Viktor Orban’s power is consolidated, the Hungarian health care system and social safety net have been in a freefall since the Great Recession (Bohle and Greskovits Citation2019; BTI Citation2020). The struggling economy and the election looming in 2022 significantly increased pressure to increase the vaccination rate. However, the unwillingness to expand the safety net and the inability to find short-term fixes for the health care system left -taking a chance on Russian and Chinese vaccines to secure re-election in 2022.

Viktor Orban instrumentalized importing Sputnik V (and Chinese vaccines) against the opposition – painting the opposition criticism of the government campaign for Russian and Chinese vaccines that questioned Western vaccines as a “death campaign against Covid-19 vaccines”. Within a real and urgent crisis, Orban fabricated the “death campaign” to undermine the opposition by blaming it for high Covid19 death. The “death campaign” also served to shield Orban’s government from criticism, given the state of the Hungarian health care system and safety net. In importing and handling the Russian (and Chinese) vaccine, Orban broke institutional safeguards – EU regulation and soft guardrails – using libel, fabricating campaigns against political opponents, and attacking non-pro-government media.

In April 2022 parliamentary elections, Orban’s Fidesz secured victory with 52.25% of the vote, 135 seats, adding two seats compared to previous elections. Unlike the Serbian parliamentary elections that took place close to the import of Sputnik V, the Hungarian parliamentary elections took place significantly later. Therefore, it is more difficult to draw a direct link between the management of the pandemic and electoral outcomes. However, like in the case of Serbia, the import of the Sputnik V is linked with breaking institutional safeguards and soft guardrails to maintain power.

Slovakia

The pandemic’s beginning caught Slovakia in a difficult situation, as a new coalition government took office in March 2020. Four parties formed the new government, and most of their members, including Prime Minister Igor Matovič, had no previous experience holding executive office. Therefore, the initial steps in managing the pandemic were performed by the outgoing PM Peter Pellegrini government (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020).

Slovakia managed the first wave of the pandemic beyond expectations. Early restrictions resulted in the lowest number of deaths from COVID19 in Europe during the first wave (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). However, during the second wave, the situation deteriorated significantly, and the long-term underfunding of the healthcare system came to the fore under the pressure of increased severe COVID19 cases. As a consequence, PM Matovič started to make various policy U-turns.Footnote28 and the popularity of the government and especially of the PM sharply declined.Footnote29 To win back support, PM Matovič decided to import the Sputnik V vaccine without the government’s approval at the end of February 2021. In his own words: “I thought people would be thankful for my bringing Sputnik to Slovakia. Instead, we got a political crisis, and I became an enemy of the people.”Footnote30

On March 1, PM Matovič welcomed the first 200,000 doses of Sputnik V personally at the airport in Kosice.Footnote31 Since Slovak democracy is in better shape than Serbian and Hungarian democracy Matovič was opposed by most of his coalition partners, Slovak media, and some state institutions. The most important of these was the Slovak Institute for Drug Control (SÚKL), which refused to grant emergency permission to use Sputnik V. Upon testing Sputnik V, SUKL announced it had found foreign cells in the vaccine and refused to approve Sputnik V’s useFootnote32,.Footnote33

After being initially blindsided by the PM, the institutional safeguards and soft guardrails attempted to contain the PM, who refused to reverse course despite the pushback from part of the Slovak government, the public, the media, and the Institute for Drug Control. Instead, in consultation with Viktor Orban, an “independent” test of the delivered vaccine dose in a Hungarian laboratory was conducted. The Hungarian laboratory granted emergency approval, and the political crisis in Slovakia deepened. The coalition partners threatened to leave the government if Matovič remained PM. The successive struggle resulted in a compromise – Igor Matovič remained in government, assuming the role of Minister of Finance, and retained influence in the government by installing a loyal member of his party as a new Prime Minister, Eduard HegerFootnote34 and the vaccination with Sputnik V commenced in July 2021.Footnote35

The Matovič and Orbán axis that allowed the import and emergency approval of Sputnik V is a further example of the cooperation of illiberal actors discussed in the theoretical section. Unlike Viktor Orbán’s, Igor Matovič’s political calculus about his coalition partners and Slovak citizens was wrong. A political crisis ensued, not only because Igor Matovič imported Sputnik V, but because he broke both institutional safeguards and soft guardrails – side-lining SÚKL and going behind the backs of his coalition partners. The Slovak case illustrates that institutional safeguards and soft guardrails struggle to counter the cross-border cooperation of illiberal elites.

Czech republic

Like Serbia, Hungary, and Slovakia, the Czech Republic was governed by populists during the pandemic and struggled significantly with a high case fatality rate (CFR) in the second and third pandemic waves. However, unlike Serbia, Hungary, and Slovakia, the Czech Republic did not import Sputnik V – because institutional safeguards and soft guardrails contained PM Babiš.

From the onset, the Sputnik V purchase polarised Czech politics: proponents – the Communist Party (key for maintaining the PM Babiš minority government) and the pro-Russian President Zeman, pushed heavily for Sputnik V (Havlik and Kluknavska Citation2022).Footnote36 The opposition was strongly in favour of adherence to the EMA rules. The populist PM Andrej Babiš publicly raised the idea of importing Sputnik V on multiple occasions. Moreover, in February 2021 he travelled to Budapest to meet Viktor Orban to “discuss the Russian vaccine. Hungary is a pioneer in this”.Footnote37

Behind the scenes, PM Babiš pushed both the Minister of Health (Jan Blatný) and the head of the regulatory body to grant emergency approval to Sputnik V before EMA approval as Minister Blatný remained “unwilling” to provide emergency authorisation of Sputnik V, prior to EMA authorisation. This cost Jan Blatný his job, as the President demanded that the PM replaces Blatný with a more “cooperative candidate”. Babiš complied, replacing Blatný with Petr Ahrenberg. However, the context and PM’s calculus had changed by this time.

Three factors changed Babiš’s calculation. First, the EU increased deliveries of Western vaccines.Footnote38 second Babiš had seen the price Igor Matovič paid for importing Sputnik V behind the back of his coalition partners, and third, the PM was facing increased scrutiny by the opposition and the press following up interview by ex-Minister Blatný regarding the pressure Blatný faced in office. Simultaneously, the PM was under pressure by the press due to failed attempt to overhaul EU vaccine distribution (together with Austria and Slovenia), which resulted in the loss of 70.000 Western vaccines for the Czech Republic.

With the PM no longer open to importing Sputnik V, President Zeman convinced the Minister of Interior Jan Hamáček (Social Democrat) that importing Sputnik V would make Hamáček a hero and improve the bleak electoral chances of Social Democrats in the October 2021 general elections. PM Babiš opposed the effort, but Hamáček, with the help of Slovak allies, organised a trip to Moscow. However, the planned trip did not occur after the Czech media published an explosive report about the involvement of GRU agents in the 2014 explosion of an ammunition depot that killed two Czech citizens.

The dynamics around Sputnik V in the Czech Republic illustrate the pressure of the pandemic on populist leaders facing electoral contests and the importance of both institutional safeguards and soft guardrails. For more than five months, the head of the regulatory agency and Minister of Health Jan Blatný were unwilling to bend to the political pressure by the PM and the President. The time was essential, as the calculus of the PM changed as the situation evolved. Unwilling to override the veto players publicly and risk the Slovak-style political crisis, PM Babiš considered the risks of importing Sputnik V too high.

Conclusions

Vaccine scarcity combined with public opinion drove demand for Sputnik V., but the rationale behind the import of Sputnik V across Europe varied. EU member states could rely on the EU common vaccine acquisition mechanism, albeit with significant delays during the first parts of 2021. EU member states are also subject to additional EU regulation – EMA approval in case of vaccines.Footnote39 Non-EU countries were left to wait for limited COVEX vaccines, donations by richer countries, or purchase vaccines available on the global market. However, with Western vaccines largely unavailable for delivery in 2021 in sufficient volume and a raging pandemic profoundly affecting the lives and economy of these countries, the public pressure to look for non-Western alternatives was significant.Footnote40

Vaccine scarcity and public pressure, combined with (proclaimed) availability of Sputnik V, were important pull factors. At the same time, regulatory bodies and frameworks acted as veto points in the Sputnik V purchase and deployment. Western countries, which considered the purchase of Sputnik V, premised the purchase and deployment on regulatory approval by EMA or its domestic counterparts. Moreover, Russian cooperation with the regulatory bodies was minimal.Footnote41 With regulatory structures in place and unwilling to bend to political will, institutional safeguards and soft guardrails in Western democracies prevented the purchase and deployment of Sputnik V. The non-EU countries in the Western Balkans, mostly low and middle-income, have weaker institutional safeguards and soft guardrails, health care systems, and social safety nets (Bieber et al. Citation2020; Schiffbauer Citation2020; Bohle et al. Citation2021; Popic and Moise Citation2021) and their leaders opted for Sputnik V. – As Serbian PM Ana Brnabic stated, “Regulations in the EU are very strict. In pandemic times, we need to be more flexible.”Footnote42

Hungarian and Slovak illiberal leaders agreed with the Serbian PM, overriding their regulatory frameworks. For populist and illiberal leaders, staking political future on vaccination and swift re-opening is a savvy political strategy.Footnote43 The weakness of institutional safeguards and soft guardrails – regulatory frameworks and lack of opposition made it easier for political leaders to cut corners to import Sputnik V. However, in the end, Serbian and Hungarian leaders successfully instrumentalized criticism of the Russian and Chinese vaccines by the opposition in political campaigns. This strategy contributed to securing their electoral victories.

The pandemic significantly enhances the power of personalist populist leaders. In the context of vaccine scarcity, vaccine production shortages, and distribution delays, securing any vaccine enables these leaders to establish “heroic leadership,” gaining mass support (Weyland Citation2020, 402). Nevertheless, overriding institutional safeguards only succeed and result in democratic erosion if the efforts remain uncontested. The case of Slovakia and the Czech Republic show that institutional safeguards and soft guardrails together can constrain increasing illiberalism and prevent democratic erosion.

In order to understand democratic backsliding, we need to analyze not only the cases when populist leaders succeed (Serbia and Hungary) but also the cases when they fail (the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, albeit ex-post). Focusing on the role of institutional safeguards, soft guardrails, and changes in context provides a more nuanced understanding of democratic erosion and democratic resilience during a great crisis.

The illiberalism of the party in power is the key explanatory factor for the import of Sputnik V. The contribution of this paper is twofold; we show the limits of the explanatory power of structural linkages and populism. While many populist leaders in countries with energy and trade ties to Russia were attracted to importing vaccines from Russia, most were reeled in by institutional guardrails. Thus, populism and structural linkages to Russia cannot explain why some countries purchase Sputnik V and others do not. The key explanatory factors are first, the illiberalism of the party in power – the willingness to override the institutional guardrails and its elite ties to Russia. Second, the ability of the leaders of Hungary and Serbia to override guardrails and safeguards hints at the extent to which guardrails and safeguards eroded in these countries – prior and during the pandemic (cf. Guasti and Buštíková Citation2022).

In the future, we ought to broaden the scope of the research outside Europe to include other vaccine providers (Russia, China, and India) and their competition beyond Europe – especially in low – and middle-income countries that lack production capacity (Latin America, Africa, many Asian countries).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Institutional safeguards of liberal democracy include a balance of power (horizontal accountability), diagonal accountability and the rule of law. Soft guardrails include democratic and constitutional norms. Both institutional safeguards and soft guardrails are necessary for liberal democracy to work. Moreover, when institutional safeguards and soft guardrails work, they can limit the erosion of liberal democracy (cf. Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018; Weyland Citation2020).

3 Data are unavailable for San Marino and Montenegro.

5 The vaccine was developed by the Gameleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology. It combined two adenoviruses using similar technology to that of the AstraZeneca vaccine. Source: https://sputnikvaccine.com/about-vaccine/ For accounts disputing important aspects of the Sputnik V efficacy and criticizing lack of transparency, see https://cattiviscienziati.com/2021/02/09/more-concerns-on-the-sputnik-vaccine/ https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31960-7/fulltext.

6 “From Russia With Love”: The Kremlin’s COVID-19 Charm Offensive’: https://www.ponarseurasia.org/from-russia-with-love-the-kremlins-covid-19-charm-offensive/.

8 https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html By May 8, 2021, Hungary received 1.8 million doses of Sputnik V and deployed 1.424 million doses; Slovakia received 200.000 doses but has not deployed any.

11 The subject of our analysis is the individual European countries. Our original intention was to analyze all European countries that are not fully authoritarian. However, the number of cases had to be limited because some European countries (such as San Marino) do not have available data. Thus, 41 or 39 countries enter the analysis in some models.

12 The variable considers only the level of illiberalism of the senior party in government (i.e. the party which controls the prime minister post). Of course, illiberal tendencies occur in other governing coalition parties, but the senior party’s position is decisive.

13 In our preliminary analysis, we have also tested additional variables in line with our theoretical model. For the party in government, we have used the new populism measure by V-DEM for the senior party in power. We have also used the V-DEM liberal democracy index. As controls, we tried to use Russia’s gas imports, EU membership, EU candidate status, ENP status, total GDP expenditure on health, GINI and confirmed cases per million. Unfortunately, none of these variables yielded any significant findings.

14 See appendix B for a detailed overview of export to Russia, China and Hungary.

15 At the request of the editors and reviewer, we also tested our argument in the case of vaccines from China. The results are in Appendix C. In this case, the effect of EU membership is slightly higher and the effect of illiberalism slightly lower, but still clearly in line with our main analysis. Our explanation thus has demonstrable explanatory potential beyond Sputnik V.

16 We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for this idea.

17 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/19/coronavirus-vaccine-diplomacy-west-falling-behind-russia-china-race-influence https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/how-aleksandar-vucic-stole-the-vaccine-diplomacy-show/ (last visited 18.8.2022).

18 There was a mutual agreement between Brnabic and Vucic on the matter. https://www.euronews.com/2021/04/06/serbian-president-aleksandar-vucic-gets-chinese-made-covid-19-jab.

20 Overall 2.5 million doses, with an order for additional 2 million doses confirmed in April 2021. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/china-to-send-more-covid-19-vaccine-doses-to-serbia/2157428.

22 https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-issues-6-month-authorization-for-russias-sputnik-vaccine/.

23 https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/hungarian-drug-regulator-approves-sputnik-v-vaccine-website-2021-01-20/ https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20210212-hungary-to-start-covid-19-vaccinations-with-russia-s-sputnik-v-bypassing-eu-regulator.

25 Data as of May 13, 2021, https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#distribution-tab.

26 Hungary was significantly above the EU average (as of July 23, 2021, 63.8% of Hungarians had been fully vaccinated, 10% points above the EU average) https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

27 Of the 2 million doses received by July 2021, 1.812 million doses of Sputnik V are reported as deployed, compared to 4.5 million of the 6.9 million delivered doses of Bio/N/Tech, and 2 million of the 5.2 million delivered doses of the Chinese vaccine Beijing CNBG https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#distribution-tab.

28 A typical example of a policy U-turn is the two large-scale covid testing events in Slovakia in November 2020 and January 2021. Slovakia was the first (and to our knowledge, still the only) country to take such a step. Instead of the expected breakthrough in fighting the pandemic and rallying the Slovak public, the nationwide testing failed, deepening the animosity between individual members of the government and increasing public frustration https://www.irozhlas.cz/komentare/komentar-slovensko-koronavirus-testovani-covid-19-plosne-testovani_2101240629_vtk.

35 The demand for Sputnik V was meager. As of July 2021, 10,500 Slovak citizens had received the Sputnik V vaccine, and a further 8,000 were expected to receive their second dose. After a diplomatic exchange, Russia bought back 160,000 of the vaccines for the purchase price to prevent their expiration. https://echo24.cz/a/SS4WP/na-slovensku-se-zacne-ockovat-sputnikem-v.

36 President Miloš Zeman, whose constitutional role is largely ceremonial but whose informal influence is significant, has been pushing for Sputnik V (and Chinese vaccines) acquisition since fall 2020. Both directly, exercising pressure on the PM and the Social Democrats (the junior partner in the government) and indirectly, via close ties with the Communist party (essential in keeping the minority government in power). President Zeman’s pressure intensified during the vaccine delivery shortages in February and March 2021. As a result, President Zeman wrote a letter to Russian President Vladimir Putin requesting the commencement of the vaccine acquisition process.

37 https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/babis-leti-za-orbanem-ma-zajem-o-sputnik-40350028 (last visited 18.8.2022).

38 As of May 13, 2021, 32.9% of Czech citizens had received at least one dose of the COVID19 vaccine. In total, almost 4 million Czechs have been vaccinated with Pfizer BioNTech (3.2 million), AstraZeneca (541.000), Moderna (471.000), and Janssen (26.000). Moreover, while Czech democracy slightly declined in the past several years, it remained mostly resilient during the pandemic (PanDem Citation2021).

40 In December 2020 EU adopted a 70 million EUR assistance package for the Balkans, including delivery of 651.000 doses of Pfizer BioNTech vaccines thru August 2021. Combined, EU and COVAX will provide 1 million doses in the first half of 2020 to the Balkans, whose population is approximately 18 million. https://www.rferl.org/a/eu-formally-delivers-covid-19-vaccines-to-balkans/31237793.html.

41 Rolling review of Sputnik V by EMA commenced in March 2021, but the documentation submitted is incomplete and slowing down the process https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-starts-rolling-review-sputnik-v-covid-19-vaccine.

43 For example, the Serbian economy was expected to expand by 5% and its GDP to grow by 6.5% in 2021. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/serbian-president-pursues-eu-membership-better-us-ties-and-a-bigger-role-in-the-balkans/.

References

- Afsahi, A., E. Beausoleil, R. Dean, S. A. Ercan, and J. P. Gagnon. 2020. “Democracy in a Global Emergency.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): v–xix.

- Anghel, V., and E. Jones. 2022. Riders on the Storm: The Politics of Disruption in Italy and Romania During the Pandemic. This special issue.

- Bader, M. 2014. “Democracy Promotion and Authoritarian Diffusion: The Foreign Origins of Post-Soviet Election Laws.” Europe-Asia Studies 66 (8): 1350–1370.

- Bermeo, N. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19.

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index. 2020. Transformation Atlas. https://www.bti-project.org/en/atlas.html.

- Bieber, F., et al. 2020. “The Western Balkans in Times of the Global Pandemic.” Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group 1–37.

- Bílek, J. 2021. “Linkage to the West and Electoral Manipulation.” Political Studies Review 19 (2): 262–273.

- Bohle, D., and B. Greskovits. 2019. “Politicising Embedded Neoliberalism: Continuity and Change in Hungary’s Development Model.” West European Politics 42 (5): 1069–1093.

- Bohle, D., G. Medve-Balint, V. Scepanovic, and A. Toplisek. 2021. Varieties of Authoritarian Capitalisms? The Covid-19 Response of Eastern Europe’s Right-Wing Nationalists. This special issue.

- Brownlee, J. 2012. Democracy Prevention: The Politics of the U.S.-Egyptian Alliance. Cambridge University Press.

- Brownlee, J. 2017. “The Limited Reach of Authoritarian Powers.” Democratization 24 (7): 1326–1344.

- Bruszt, L. 2020. “Viktor Orban: Hungary’s Desease Dictator.” Reporting Democracy – BalkanInsight.com.

- Buštíková, L., and P. Baboš. 2020. “Best in Covid: Populists in the Time of Pandemic.” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 496–508.

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47 (1): 2–16.

- Cassani, A., and L. Tomini. 2019. “Post-Cold War Autocratization: Trends and Patterns of Regime Change Opposite to Democratization.” Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 49 (2): 121–138.

- Devine, D., J. Gaskell, W. Jennings, and G. Stoker. 2021. “Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature.” Political Studies Review 19 (2): 274–285.

- Dimitrijević, D. 2017. “Chinese Investments in Serbia—a Joint Pledge for the Future of the new Silk Road.” TalTech Journal of European Studies 7 (1): 64–83.

- Freedom House. 2021. Freedom in the World. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege.

- Gaskell, J., and G. Stoker. 2020. “Centralized or Decentralized.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 33–40.

- Gilbert, L., and P. Mohseni. 2018. “Disabling Dissent: The Colour Revolutions, Autocratic Linkages, and Civil Society Regulations in Hybrid Regimes.” Contemporary Politics 24 (4): 454–480.

- Guasti, P. 2020a. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Central and Eastern Europe.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 47–60.

- Guasti, P. 2020b. “Populism in Power and Democracy: Democratic Decay and Resilience in the Czech Republic (2013–2020).” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 473–484.

- Guasti, P., and L. Buštíková. 2022. “A Marriage of Convenience: Responsive Populists and Responsible Experts.” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 468–472.

- Hartikainen, I. 2021. “Authentic Expertise: Andrej Babiš and the Technocratic Populist Performance During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Frontiers in Political Science 3: 734093. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.734093.

- Havlik, V., and A. Kluknavska. 2022. “The Populist Vs Anti-Populist Divide in the Time of Pandemic: The 2021 Czech National Election and its Consequences for European Politics*.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 1–12. doi:10.1111/jcms.13413.

- Honig, B. 2020. “American Quarantine.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 143–151.

- Hyde, S. D. 2020. “Democracy’s Backsliding in the International Environment.” Science 369 (6508): 1192–1196.

- Kaltwasser, C. R. 2014. “The Responses of Populism to Dahl’s Democratic Dilemmas.” Political Studies 62 (3): 470–487.

- King, T., B. Hewitt, B. Crammond, G. Sutherland, H. Maheen, and A. Kavanagh. 2020. “Reordering Gender Systems: Can COVID-19 Lead to Improved Gender Equality and Health?” The Lancet 396 (10244): 80–81.

- Laruelle, M. 2022. “Illiberalism: A Conceptual Introduction.” East European Politics 38 (2): 303–327.

- Levine, P. 2020. “Theorizing Democracy in a Pandemic.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 134–142.

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. 2020. “The New Competitive Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy 31 (1): 51–65.

- Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. 2018. How Democracies Die. Broadway Books.

- Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. 2020. “The Crisis of American Democracy.” American Educator 44 (3): 6.

- Lindberg, S. I., et al. 2022. Codebook Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V–Party) V2. Varieties of Democracy (V–Dem) Project. doi:10.23696/vpartydsv2

- Logunov, D. Y., I. V. Dolzhikova, D. V. Shcheblyakov, A. I. Tukhvatulin, O. V. Zubkova, A. S. Dzharullaeva, and Gam-COVID-Vac Vaccine Trial Group. 2021. “Safety and Efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 Vector-Based Heterologous Prime-Boost COVID-19 Vaccine: An Interim Analysis of a Randomised Controlled Phase 3 Trial in Russia.” The Lancet 397 (10275): 671–681.

- Lührmann, A., and B. Rooney. 2020. “Autocratization by Decree: States of Emergency and Democratic Decline.” V-Dem Working Paper, 85.

- Magyar, B. 2016. Post-communist Mafia State. Central European University Press.

- Mazepus, H., A. Dimitrova, M. Frear, T. Chulitskaya, O. Keudel, N. Onopriychuk, and N. Rabava. 2021. “Civil Society and External Actors: How Linkages with the EU and Russia Interact with Socio-Political Orders in Belarus and Ukraine.” East European Politics 37 (1): 43–64.

- Merkel, W. 2020. “Who Governs in Deep Crises?” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 1–11.

- Mudde, C. 2016. On Extremism and Democracy in Europe. Routledge.

- Naczyk, M., and C. Ban. 2022. The Sputnik V Moment: Biotech, Biowarfare and COVID-19 Vaccine Development in Russia and in Former Soviet Satellite States, this issue.

- Nations in Transit. 2021. The Antidemocratic Turn. https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2021/antidemocratic-turn.

- Nolan, R. 2021. “‘We are all in This Together!’ Covid-19 and the lie of Solidarity.” Irish Journal of Sociology 29 (1): 102–106.

- Owen, D. 2020. “Open Borders and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 152–159.

- PanDem. 2021. Pandemic Backsliding – Democracy during Covid19. https://www.v-dem.net/shiny/PanDem/.

- Pirro, A. L., and B. Stanley. 2021. “Forging, Bending, and Breaking: Enacting the “Illiberal Playbook” in Hungary and Poland.” Perspectives on Politics 1–16.

- Popic, T., and A. D. Moise. 2021. Government Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Eastern and Western Europe: The Role of Political, Economic and Healthcare Factors. This special issue.

- Prainsack, B. 2020. “Solidarity in Times of Pandemics.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 124–133.

- Rapeli, L., and I. Saikkonen. 2020. “How Will the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Democracy?” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 25–32.

- Ruth-Lovell, S. P., Lührmann, A., and Grahn, S. 2019. Democracy and populism: Testing a contentious relationship. V-Dem Working Paper, 91.

- Schiffbauer, M. T., and World Bank. 2020. Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, No. 17. Spring 2020: The Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19.

- Simons, J., A. Toplisek, E. Eihmanis, and N. Oellerich. 2022. Stumbling Toward Social and Industrial Upgrading? The Political Foundations of the COVID-19 Responses in East Central Europe, this special issue.

- Spruyt, B., Keppens, G., and Van Droogenbroeck, F. 2016. Who supports populism and what attracts people to it?. Political Research Quarterly 69 (2): 335–346.

- Subotić, J. 2016. “Narrative, Ontological Security, and Foreign Policy Change.” Foreign Policy Analysis 12 (4): 610–627.

- Tansey, O. 2016. The International Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tolstrup, J. 2014. “Gatekeepers and Linkages.” Journal of Democracy 25 (4): 126–138.

- Vasovic, M. Serbia's President Turned the Pandemic Into a Tacky Campaign. Balkan Insights, May 7, 2020. https://balkaninsight.com/2020/05/07/serbias-president-turned-the-pandemic-into-a-tacky-campaign/

- Weiffen, B. 2020. “Latin America and COVID-19.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 61–68.

- Weyland, K. 2020. “Populism’s Threat to Democracy: Comparative Lessons for the United States.” Perspectives on Politics 18 (2): 389–406.

- Whitehead, L. 2014. “Anti-democracy Promotion: Four Strategies in Search of a Framework.” Taiwan Journal of Democracy 10 (2): 1–24.

- Yakouchyk, K. 2019. “Beyond Autocracy Promotion: A Review.” Political Studies Review 17 (2): 147–160.

Appendixes

Appendix A. Descriptive statistics

Appendix B. Export to Russia, China and Hungary (in %)

Appendix C. Statistical test of our argument for China’s vaccine

The basic design of this analysis is the same as in our main analysis. The dependent variable in this analysis is the import of vaccines, which can include purchase as well as receiving vaccines as donations (e.g. both Serbia and Turkey donated vaccines to lower-income countries, such as Albania).Footnote44

Logistic Regression, Odds Ratio